Incumbent leaders often gain support when their country faces a major national security threat. Political scientists have labeled this a “rally ‘round the flag” effect (Mueller Reference Mueller1970). Highly visible terrorist attacks typically produce rally effects, as exemplified by US President George W. Bush’s approval ratings shifting from near 50% to over 80% after the devastating September 11 attacks.Footnote 1 Incumbent administrations can benefit even when terrorist attacks do not take place on their own soil: UK Prime Minister Tony Blair experienced a 10-percentage-point increase in approval following September 11. And, simply raising the specter of terrorism via government warnings on threat levels often generates rally effects (Willer Reference Willer2004).

Of course, terrorist events can yield heterogeneous rally dynamics. For example, public opinion moves more in favor of incumbents and right-leaning politicians and parties (Berrebi and Klor Reference Berrebi and Klor2008; Chowanietz Reference Chowanietz2011; Getmansky and Zeitzoff Reference Getmansky and Zeitzoff2014; Merolla and Zechmeister Reference Merolla and Zechmeister2013). That tendency, though, is not universal. At first glance, the deadly bombing at the Manchester Arena in the UK in 2017 appears to be an exception. Soon after this major terrorist event, the right-leaning incumbent party lost seats in parliamentary elections. A distinguishing characteristic of this case is the gender of the incumbent executive, Prime Minister Theresa May. Did public support for the executive slump not bump following the Manchester Bombing and, if so, could gender be the culprit?

The conventional rally ‘round the flag framework is silent on the relevance of the executive’s gender. This deficit in attention makes sense, given that few women have served as heads of government, particularly during a national security crisis (Jalalzai Reference Jalalzai2016). Those canvassing the state of the field have found that “few scholars examine how terrorism affects women leaders,” creating a “paucity of research” that examines leader gender, public opinion, and terrorism (Ortbals and Poloni-Staudinger Reference Ortbals and Poloni-Staudinger2018a, 209, 267). Yet times are changing, and so must the rally ‘round the flag framework. If the terrorist-induced rally round the flag dynamic extends to any executive, then all heads of government—regardless of their gender—should benefit. And to the degree that ideology matters, a right-leaning chief executive should particularly benefit from a rally following a major terrorist attack. In this way, the evaluation of an incumbent woman from a right-leaning party creates a “most-likely” case because “on all dimensions except the dimension of theoretical interest, [it] is predicted to achieve a certain outcome” (Gerring Reference Gerring2007, 232).

Our contention, however, is that terrorist attacks will not necessarily produce a bump in opinion for women executives and may even lead to a slump in support. We develop a gender-revised framework by bringing conventional rally ‘round the flag theory into dialogue with scholarship on women in politics. This research highlights several relevant factors. In general, voters associate leadership with masculinity (e.g., Carpinella et al. Reference Carpinella, Hehman, Freeman and Johnson2015; Little et al. Reference Little, Burriss, Jones and Robert2007; Poloni-Staudinger and Ortbals Reference Poloni-Staudinger and Ortbals2014), and men with the trait of strong leadership (Bauer Reference Bauer2017; Reference Bauer2020b). Individuals threatened by terrorism further privilege masculine traits, which places women leaders at a disadvantage in those contexts (e.g., Holman, Merolla, and Zechmeister Reference Holman, Merolla and Zechmeister2011; Reference Holman, Merolla and Zechmeister2016). As voters do not see women as inherently strong leaders, especially in national security crises, they may hold women to a higher standard (Bauer Reference Bauer2020a) following a major terrorist attack and a rally may fail to materialize.

We identify the May 22, 2017 Manchester Bombing as an unexpected event to test the implications of the gender-revised framework for potential rally events. We use data from the British Election Study (BES), which fielded a wave of their survey during the 2017 election (May 5–June 7), sampling respondents on a rolling basis prior to and following the Manchester Bombing. Participant selection either prior to or after these events was as-if random, meeting the requirements of a natural experiment (Dunning Reference Dunning2008; Müller and Kneafsey Reference Müller and KneafseyForthcoming; Muñoz, Falcó-Gimeno, and Hernández Reference Muñoz, Falcó-Gimeno and Hernández2020). The data allow a causal test of the relationship between the Manchester Bombing and evaluations of May. This is important because the loss of seats experienced by her party in the 2017 election could have been driven by other factors that mask a conventional public opinion rally.

In fact, the evidence shows that May does not benefit from a rally ‘round the flag in the aftermath of the terrorist attack. Rather, we show her support declines after the Manchester event. Our gender-revised rally thesis holds that such a decline will be most pronounced among those who hold negative views of women. Analyses of the data support this theorized mechanism. Furthermore, we show that the negative outcome also transfers to her party: the Conservative Party lost votes at the constituency level by distance to Manchester. Altogether, the case comports with the theory that gendered evaluations of political leaders place women executives—and their parties—at a disadvantage when terrorists strike.

Is this conclusion robust to analyses that extend beyond this one case? Our argument is that, on average, women executives are less likely to receive a rally following a major terrorist attack. To evaluate the strength of our thesis, we assess the relationship between large terrorist attacks and executive approval using a global analysis of 66 countries. We find results consistent with our gender-revised argument: for men as leaders, the mean tendency is for opinion to increase following major international terrorist attacks. For women leaders, the model predicts a slump, as approval of women executives declines after similar attacks. Taken together, the multifaceted assessment of data on Theresa May’s approval, the aggregate constituency results, and this global analysis provide robust evidence for the gender-revised rally ‘round the flag framework.

Rallies, Terrorism, and Women Political Leaders

Understanding factors that shape executive approval matters because public opinion on job performance increases the capacity of executives to advance their agenda and win votes (e.g., Canes-Wrone and De Marchi Reference Canes-Wrone and De Marchi2002; Donovan et al. Reference Donovan, Kellstedt, Key and Lebo2020). Executive approval rises and falls in response to many factors, including the onset of major events. While some events reduce approval, others shift approval upward, generating a rally behind the incumbent administration (Newman and Forcehimes Reference Newman and Forcehimes2010). Rally dynamics are most common in the wake of events that are intense, highly visible, relevant to the executive office, and have an international component (Mueller Reference Mueller1970), such as major terrorist attacks by foreign-affiliated groups, which tend to produce strong rally effects (Chowanietz Reference Chowanietz2011). But do women executives stand to benefit equally from rallies following such terrorist attacks? Given the limited number of women who have served as elected heads of government, the rally literature has almost universally considered dynamics related to men as leaders. That rallies are reflexive bursts of patriotism suggests women would benefit. However, research on gender and leadership leads us to theorize that rallies will be comparatively muted or entirely absent when women are in the executive office. That is, the public can fail to rally, or rally to a comparatively lesser degree, around a woman executive even in the most likely of cases.

The Traditional Rally ‘round the Flag Framework

The notion of a rally ‘round the flag is grounded in work by Mueller (Reference Mueller1970), who argued that certain types of crises result in upticks in presidential approval. The types of incidents most likely to fuel such outcomes are those that are international, involve the executive, and are “specific, dramatic, and sharply focused” (Mueller Reference Mueller1970, 21). An international dimension increases the likelihood of a rally because it is more likely to provoke a unified response across party lines. Further, crises with an international link generate rally effects if they involve the executive office because absent that connection they may be ignored or considered irrelevant by the public. And, finally, sudden and intense events promote upticks in public support for the executive. One way to gauge this latter criterion is to require that the incident appears on the front page of major newspapers (Newman and Forcehimes Reference Newman and Forcehimes2010; Oneal and Bryan Reference Oneal and Bryan1995).Footnote 2

Major, lethal terrorist attacks on domestic soil and in which the perpetrators claim a foreign allegiance are among the events that are most likely to generate a rally effect. These events cast a foreign enemy against which the country can close ranks. They affect national security and thus are relevant to the executive office. They appear without warning, requiring an immediate response. And they burst into the headlines of major papers. Chowanietz (Reference Chowanietz2011, 673) examines the US, UK, France, Germany, and Spain and finds that “rallies around the flag are the rule,” especially in the post-September 11 era, when the attacks were reported on in the media, and when they generated several or more fatalities. In short, the empirical evidence strongly affirms that highly visible and intense terrorist attacks evoke rally dynamics, particularly when they include an international element.

Although any major terrorist attack carries the potential to provoke a rally effect, public reactions may vary depending on the ideology of the leader’s party. In the US, terror threats lead the public to evaluate right-leaning (Republican) incumbents more favorably than left-leaning (Democratic) incumbents (Merolla and Zechmeister Reference Merolla and Zechmeister2013; see also Willer Reference Willer2004). In Israel, the threat of terrorism and terrorist attacks increases votes for right-leaning politicians (Berrebi and Klor Reference Berrebi and Klor2008; Getmansky and Zeitzoff Reference Getmansky and Zeitzoff2014). Two nonrival mechanisms help explain this bias toward right-wing actors. First, public opinion shifts in more authoritarian, conservative, and right-leaning directions in contexts of terrorist threat (Bonanno and Jost Reference Bonanno and Jost2006; Finseraas and Listhaug Reference Finseraas and Listhaug2013; Merolla and Zechmeister Reference Merolla and Zechmeister2009). Second, individuals threatened by terrorism are more inclined to throw their support behind parties deemed to have a strong reputation on national security issues, and this is often the case for right-leaning parties (Merolla and Zechmeister Reference Merolla and Zechmeister2013). For example, in the UK, the Conservative party “enjoys a positive image with regard to … defense issues” (Bélanger and Meguid Reference Bélanger and Meguid2008, 478; see also Budge and Farlie Reference Budge and Farlie1983).Footnote 3 Thus, in some countries (including the US, Israel, France, and the UK), right-wing parties benefit more from rally effects (see prior citations and also Chowanietz Reference Chowanietz2011).

An urge to engage in defense of the nation drives rally effects. This inclination to circle the wagons is often accompanied by an increase in support not only for the executive but also for the country (patriotism), the national government, and its core institutions (e.g., Dinesen and Jæger Reference Dinesen and Jæger2013; Li and Brewer Reference Li and Brewer2004; Skitka Reference Skitka2005). As Kam and Ramos (Reference Kam and Ramos2008) explain, external threats to the country trigger a tendency toward in-group consolidation around the nation and its symbols and core offices, including the executive (see also Parker Reference Parker1995). To the extent that the rally ‘round the flag effect is simply a reflexive reaction toward allegiance to the nation and its core institutions, then theoretically it ought to extend to any executive regardless of their gender. However, should we anticipate that a robust rally is the norm for women executives in the wake of a major international terrorist attack?

A Gender-Revised Rally Framework

Theory from several lines of scholarship suggests an answer: No, the public may resist rallying around modern women heads of government. In fact, a Gender-Revised Rally Framework suggests that women executives might not only fail to receive a boost in approval following a major terrorist incident but could experience a decline in support. This expectation is based on several factors, including a public preference for men’s political leadership in general and in times of security threat or active military action in particular (Barnes and O’Brien Reference Barnes and O’Brien2018; Holman, Merolla, and Zechmeister Reference Holman, Merolla and Zechmeister2011; Reference Holman, Merolla and Zechmeister2016; Kim and Kang Reference Kim and Kang2021; Ortbals and Poloni-Staudinger Reference Ortbals and Poloni-Staudinger2018b). Such inclinations lead the public to hold women leaders to higher standards (Bauer Reference Bauer2017; Reference Bauer2020b), as they do not fit the executive leader prototype.

Generally speaking, political leadership is associated with men and masculinity (Bauer Reference Bauer2020b; Mo Reference Mo2014; Oliver and Conroy Reference Oliver and Conroy2020; Schneider and Bos Reference Schneider and Bos2019). According to social role theory, these deeply engrained associations emerge from women and men historically performing separate social roles in society (Eagly and Karau Reference Eagly and Karau2002), with men fulfilling public leadership roles. The public has a baseline preference for agentic qualities, stereotypically associated with men, in political leaders (Schneider and Bos Reference Schneider and Bos2019), and voters are less inclined to think that women leaders hold these particular qualities (Bauer Reference Bauer2017; Ortbals and Poloni-Staudinger Reference Ortbals and Poloni-Staudinger2016). As Bauer (Reference Bauer2020b, 4) puts it, during elections, “Masculine role-typicality standards create a high qualification bar for female candidates because such standards evoke a masculine standard of comparison, and there is a high level of incongruence between being female and being a leader.”

Terrorist attacks, as critical threats to national security, may exacerbate these tendencies and be particularly damaging to sitting women political leaders. The voting public prefers strong, resolute leadership in the face of national security threats (Gadarian Reference Gadarian2010; Merolla and Zechmeister Reference Merolla and Zechmeister2009)—that is, the types of traits (e.g., driven, aggressive) that the public associates with men and men who are politicians (Bauer Reference Bauer2020b; Biernat and Kobrynowicz Reference Biernat and Kobrynowicz1997; Boussalis et al. Reference Boussalis, Coan, Holman and Müller2021; Eagly and Karau Reference Eagly and Karau2002). As Ortbals and Poloni-Staudinger (Reference Ortbals and Poloni-Staudinger2018b, 9) note, “[f]eminine traits associated with women are found to be undesirable” in leadership roles associated with war, violence, and terrorism. Instead, the public looks for masculine traits. For example, the US public sees men as better able to deal with terrorist attacks; that attitude translates into greater support for men as executives (Lawless Reference Lawless2004). Further, concern about national security issues in the US correlates with a higher likelihood of seeing presidents who are men (versus women) as more capable of handling those issues (Falk and Kenski Reference Falk and Kenski2006). In the context of a terrorist attack, then, individuals may assume that men are natural leaders in these situations and give them credit for handling the situation well, leading to increased evaluations of their performance.

Finally, as some of this work already suggests, women may also be particularly disadvantaged in public opinion when they sit as heads of government (versus holding other offices). The greater mismatch between women and the typical executive (Fox and Oxley Reference Fox and Oxley2003) means that some women who attain this role succeed by projecting masculine qualities (Bauer Reference Bauer2020b; Koch and Fulton Reference Koch and Fulton2011; Oliver and Conroy Reference Oliver and Conroy2020). For example, Margaret Thatcher’s nickname of the ‘Iron Lady’ emerged “because she showed aggressiveness and strength while serving as Prime Minister” (Bauer Reference Bauer2020b, 66). Yet, even if women attain executive office by projecting masculine qualities, they cannot hide their gender. In turn, their gender reminds voters of the lack of congruence with a typical leader and may lead the public to hold women to a higher standard (Bauer Reference Bauer2020a). Due to the strong preference for men’s leadership for highly masculine offices, like those of a head of government (Conroy Reference Conroy2015; Reference Conroy2018; Fox and Oxley Reference Fox and Oxley2003; Jalalzai Reference Jalalzai2016), and for offices that handle foreign policy (Barnes and O’Brien Reference Barnes and O’Brien2018; Krook and O’Brien Reference Krook and O’Brien2012), even when women try to counter gender stereotypes by acting assertively and aggressively in response to national security threats, it can provoke backlash (Falk and Kenski Reference Falk and Kenski2006; Ortbals and Poloni-Staudinger Reference Ortbals and Poloni-Staudinger2018b). These tendencies suggest that, to the extent that postterrorist attack dynamics result in a backlash against women political leaders, we should be most likely to uncover this outcome when examining judgments of women serving in executive positions.

A broad body of scholarship provides evidence that women leaders are comparatively disadvantaged in times of national security crisis. At the same time, women leaders can sometimes overcome the dynamics that weave masculine traits, security crises, and public opinion together. For example, some argue that the public in these contexts cares about compassion, and women may be able to leverage an edge on this trait (Hansen and Otero Reference Hansen and Otero2007) or by applying other frames to their advantage (Ortbals and Poloni-Staudinger Reference Ortbals and Poloni-Staudinger2016). Further, women may be able to build a portfolio of national security experience and/or take more hawkish stances to try to mitigate against these tendencies (Albertson and Gadarian Reference Albertson and Gadarian2016; Holman, Merolla, and Zechmeister Reference Holman, Merolla and Zechmeister2011; Reference Holman, Merolla and Zechmeister2017; Koch and Fulton Reference Koch and Fulton2011; but see Holman et al. Reference Holman, Merolla, Zechmeister and Wang2019). Importantly, despite the richness of scholarship on public opinion, security threats, and women leadership, the question of how incumbent women executives fare in the face of security challenges remains understudied.

Assessing the rally thesis requires a focus on incumbent executives. Comparatively little research has considered incumbent gender, security crises, and executive approval. One exception is Carlin, Carreras, and Love (Reference Carlin, Carreras and Love2020), who study approval dynamics in 20 presidential systems and find that women executives’ aggregate job approval ratings decrease as the number of terrorist incidents increases. This is informative, but their work focuses largely on domestic terrorist attacks and does not distinguish attacks by their severity; thus, it does not test the conventional rally thesis. Likewise, prior research on rallies has not tested the micrologic detailed above, which is that slumps not bumps are driven by gender bias. To put the gender-revised rally framework to a stringent test, we need microlevel data from a most likely case: a major terrorist attack with an international component, occurring when a right-leaning woman executive is at the helm.

If a tendency to hold women executives to higher standards is based on a mismatch between perceptions of a typical leader and a woman in that role, then a key mechanism underlying this effect should be observable at the individual level. Variation exists in the extent to which individuals think women should hold traditional roles in society and support women in political office (Eagly and Karau Reference Eagly and Karau2002; Kim and Kang Reference Kim and Kang2021). These attitudes shape support for women’s candidacies (Cassese and Barnes Reference Cassese and Barnes2018; Cassese and Holman Reference Cassese and Holman2019; Holman, Merolla, and Zechmeister Reference Holman, Merolla and Zechmeister2016). While the degree to which these views might counteract a rally dynamic has not been tested, previous work has found that gender stereotypes about political leaders can be activated by such an event (Holman, Merolla, and Zechmeister Reference Holman, Merolla and Zechmeister2016). If attitudes about gender drive this tendency to hold women executives to a higher standard, then those with more traditional or sexist gender attitudes should be less inclined to rally behind a sitting woman executive following a terrorist attack.

A Natural Experiment: Methods and Data

To test our expectations regarding rally dynamics around women in executive leadership positions, we turn to a major terrorist attack that occurred in Britain in 2017. On May 22, 2017, a suicide bomber carried out an attack at an Ariana Grande concert at the Manchester Arena, killing 23 persons (himself included) and injuring hundreds.Footnote 4 The attack occurred during a national election that began on April 18, 2017, and ended with a vote on June 8, 2017. The election was called by Theresa May, UK prime minister and leader of the Conservative Party. She did so in the midst of favorable ratings, presumably to shore up support for Brexit negotiations (BBC News 2017). The fact that the attack occurred during data collection for the British Election Study (BES) created a natural experiment, in which the treatment (a major terrorist attack) occurred “as if” random with respect to the timing of individuals’ survey responses (Muñoz, Falcó-Gimeno, and Hernández Reference Muñoz, Falcó-Gimeno and Hernández2020).

The terrorist attack fits the criteria established by scholars for rally ‘round the flag phenomena. First, it had an international component: the attacker was a radicalized Islamic extremist linked to international terrorist groups. Second, the attack was relevant to the executive office: its scope vaulted it into the domain of national politics. Third, the attack was sudden, intense, and lethal. The arena attack killed 23 people and wounded at least another 250 (Abbit Reference Abbit2017), making it the deadliest terrorist event on UK soil since the 2005 bombings in the London Tube. Fourth, the event was covered extensively in the media, on the front page of every newspaper in the United Kingdom, including on the front page of The Guardian and The Sun for more than a week. All political leaders in the election paused their campaigns. As a result, the attack drew public attention and focus.Footnote 5

Furthermore, Theresa May’s profile, save gender, fits with what past research has found makes a rally more likely. Theresa May’s party is the right-leaning Conservative Party. The party has had a comparatively favorable image on defense issues (Budge and Farlie Reference Budge and Farlie1983; BES 2019). Past scholarship predicts that a terror-threatened public will be more inclined to turn toward a party that “owns” such issues (Merolla and Zechmeister Reference Merolla and Zechmeister2013). Further, May had acquired experience in issues related to security during her tenure as Home Secretary, 2010–2016, and as the incumbent Prime Minister, which could counteract tendencies to devalue particular women leaders in times of terrorist threat (Holman, Merolla, and Zechmeister Reference Holman, Merolla and Zechmeister2011; Reference Holman, Merolla and Zechmeister2017).

Methods and Data: To examine the effect of the terrorist attack on evaluations of Prime Minister May, we apply Unexpected Event during Survey and Interrupted Time-Series Difference-in-Difference Designs. All data and replication files for analyses in this article are available at Holman, Merolla, and Zechmeister Reference Holman, Merolla and Zechmeister2021.

Unexpected Event during Survey Design: The unanticipated nature of the terrorist attacks and the presence of the British Election Study allow a causal test of the events. The survey and the attack meet the criteria for an Unexpected Event during Survey Design (UESD) (Muñoz, Falcó-Gimeno, and Hernández Reference Muñoz, Falcó-Gimeno and Hernández2020): the event was unanticipated by all except the attacker and their confidants and there is an exogenous assignment of the treatment and control groups from random survey rollout. We can thus compare responses of individuals in the control group (i.e., those who took the survey before the Manchester Bombing) and the treatment group (i.e., those who took that same survey after the Manchester Bombing). The UESD design provides external validity “beyond what controlled experiments can offer” while also limiting the influence of other macrolevel cofounding variables (Muñoz, Falcó-Gimeno, and Hernández Reference Muñoz, Falcó-Gimeno and Hernández2020, 188).

Interrupted Time-Series Design: The British Election Study (BES) uses an extended panel design, which provides an opportunity to examine how evaluations of May change over the course of several survey waves. We examine evaluations of May and selection of May as the best prime minister across the panel waves using a difference-in-difference design with fixed effects for time.

We combine the benefits of the UESD design with an interrupted time-series design, presenting a quasi-experimental design with pretests and posttests. The combination of the unexpected event analysis and an interrupted time-series design provides an exceptionally strong research design that allows us to engage in causal tests of the effect of a terrorist attack on evaluations of political leaders. It also allows us to bypass some concerns associated with posttreatment biases (Ares and Hernández Reference Ares and Hernández2017). We supplement this design with a variety of additional tests (which we elaborate on below) to further probe the causal link between the Manchester Bombing and evaluations of May.

Data: The data come from Wave 12, which was in the field from May 5–June 7, 2017, with a near-equal share of these respondents taking the survey before (n = 16,377) and after the Manchester Bombing (n = 16,972). The BES is the longest running social science survey in the UK, with 16 internet panel waves at the time of this research. We use the online panel, which was conducted by YouGov, which draws national samples from their panel and compensates participants via a token system for their participation.Footnote 6

We focus on two sets of questions as outcome measures. We make use of a module that asked: How much do you like or dislike the following party leaders? Available responses were an 11-point scale from zero, “strongly dislike,” to 10, “strongly like.” We focus on evaluations of Theresa May (Like May) as well as evaluations of other leaders later in the manuscript. We also examine responses to the question “Who would make the best prime minister?” where the response options are Jeremy Corbyn (value of zero) or Theresa May (value of 1) (May best PM).

Balance Checks and Random Assignment: In order to proceed with treating the unexpected event as a quasi-experimental treatment, we need to establish whether the control group (those who took the survey before the Manchester Bombing) and treatment group (those who took the survey after the Manchester Bombing) differ in some fundamental way that might violate our assumptions. We test for the random nature of the attacks by estimating whether any demographic variables significantly predict whether someone was “assigned” to the control and treatment groups. We find that Labour Party membership is associated with assignment to the Manchester Bombing group, but there are no other demographic differences and other randomization checks indicate that the Manchester Bombing was applied as-if random to the survey respondents (see Appendix B, Table B1).Footnote 7

In our individual-level models, we always control for Labour party membership, given the uneven distribution of supporters across the control and treatment groups. In extensions to this model, we control for a variety of factors that might influence the relationship between the terrorist attack and the outcome variables: British ethnicity, gender, ideology, income, and party membership (Oskooii Reference Oskooii2020).Footnote 8 Following best practice guidelines (Muñoz, Falcó-Gimeno, and Hernández Reference Muñoz, Falcó-Gimeno and Hernández2020), the controls are the same measures that are used in our balance checks. Finally, we cluster the errors at the day level in our analyses that only use wave 12 of the survey.Footnote 9

Effects of Manchester Bombing on Views of PM May

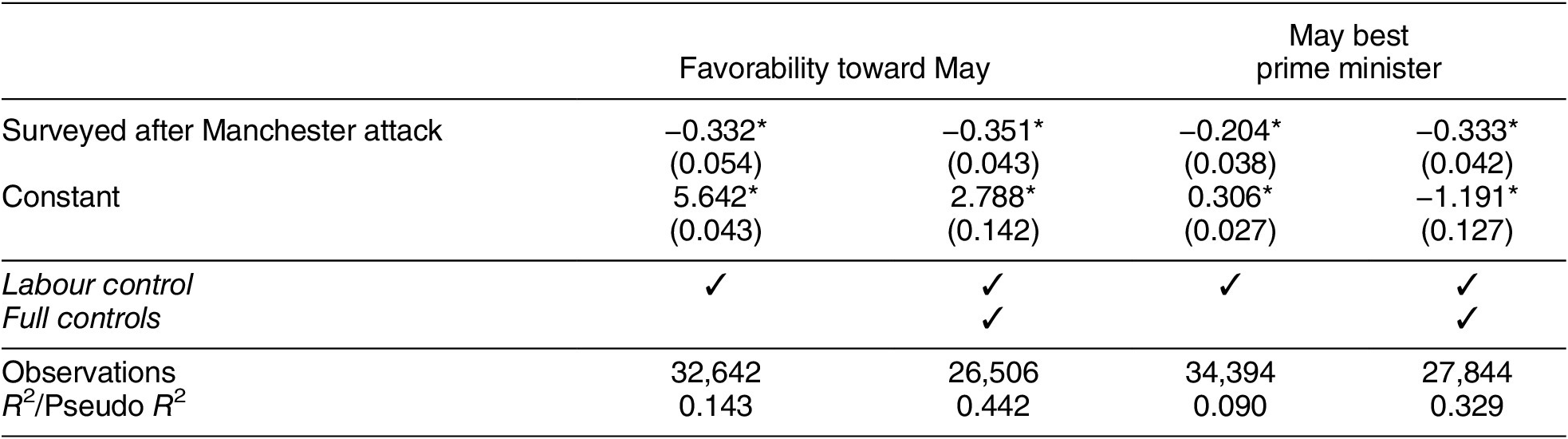

We start with a basic analysis of favorability toward May and support for May as Prime Minister among those who took the survey before and after the Manchester Bombing. Table 1 presents these results, providing models with a control just for membership in the Labour party and then with a full set of controls. Taking the survey after the Manchester attack reduces favorability toward May and the belief that she would be the best prime minister. Estimating predicted values from the second (logistic) model in the table, we find that the attack reduced the likelihood of support for May as prime minister by 5 percentage points.Footnote 10 This illustrates a slump, rather than a rally, and is a departure from conventional expectations, given her party, incumbency, experience, and the characteristics of the attack.

Table 1. Manchester Attack and Evaluations of May

Note: Clustered errors on day of survey in parentheses; ordinary least squares regression used to estimate favorability toward May (11-point scale, positive values indicate more favorability); logistic regression used to estimate preference for her (value of 1) over Corbyn (value of zero) as prime minister. Full controls include whether someone identifies as ethnically British, gender, Labour party membership, other party membership, income, and ideology. See Appendix A (Table A1) for full models; *p < 0.05.

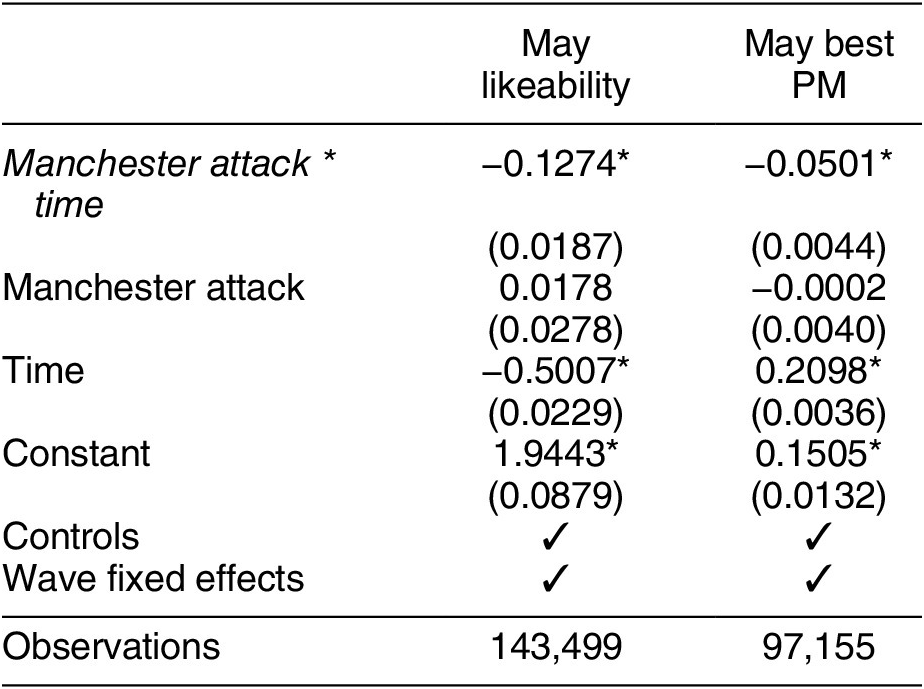

We next estimate the effect of the Manchester Bombing on views of leaders using the panel dataset and a difference-in-difference approach that includes the treatment, which represents whether an individual was surveyed before (0) or after (1) the Manchester attack; a time variable, which represents the periods of treatment, with 0 for waves prior to the attack and 1 for waves starting with 12; the attack wave; and an interaction of the treatment and time variable, with wave fixed effects.

The interaction of the attack and the time measure (our key variable of interest) decreases evaluations of May’s likeability and evaluations of her as the best Prime Minister (see Table 2). We also estimate the difference-in-difference model using an average-treatment-effect model, which yields the same results (see Appendix A, Table A5). In short, analyzing the data in multiple ways leads to a consistent finding: May experiences a slump rather than a rally from the Manchester attack.

Table 2. Difference-in-Difference, with Fixed Effects

Note: Dependent variables are 11-point favorability scale (OLS regression) and perceptions of May as the best PM (Logistic regression). Standard errors in parentheses. Full controls include whether someone identifies as ethnically British, gender, Labour party membership, other party membership, income, and ideology. See Appendix A (Table A5) for full models. *p < 0.05.

The Role of Gendered Attitudes: Testing the Mechanism

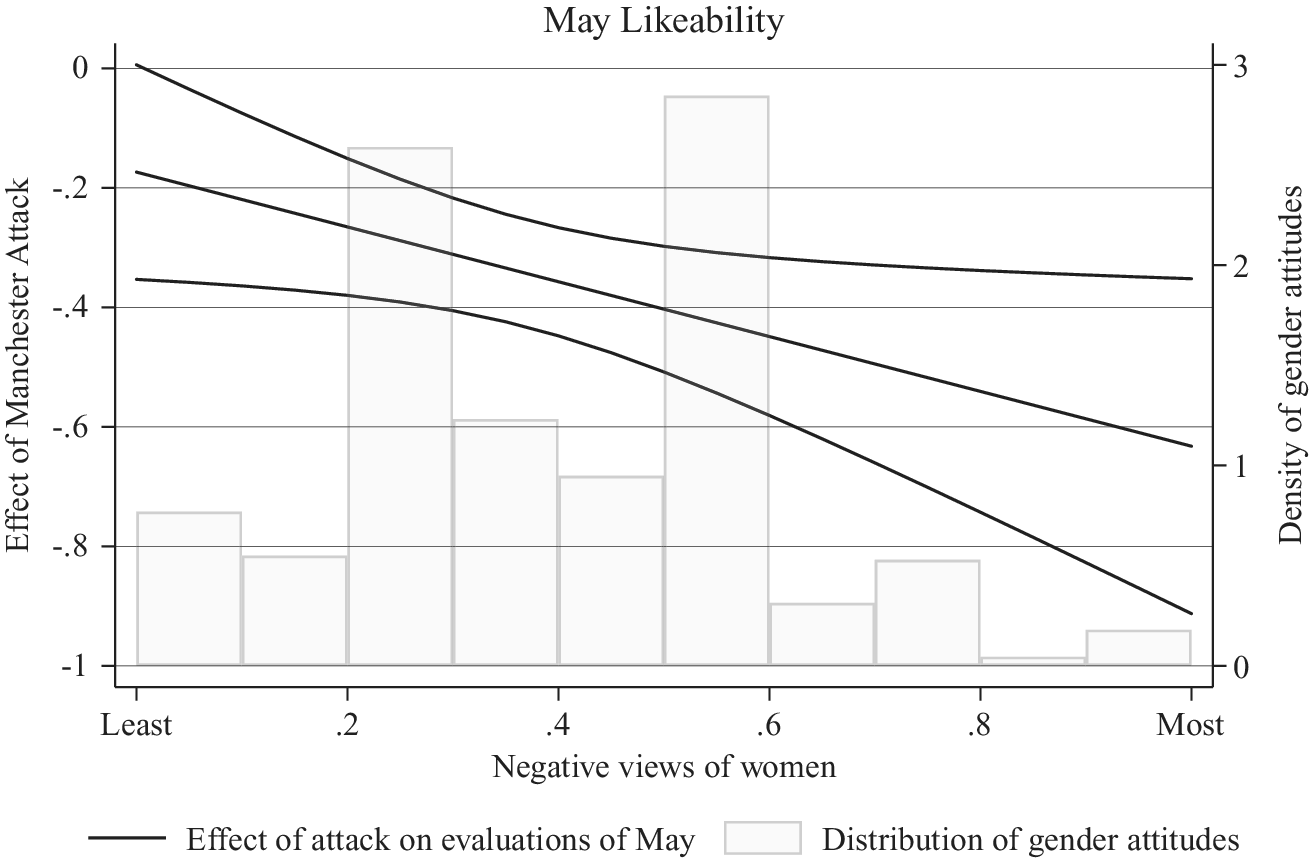

The gender-revised rally framework holds that gender bias mutes or undermines public opinion surges for women executives in the wake of a major terrorist attack. We assess the role of this mechanism by examining the degree to which the opinion dynamic around May is the product of those with negative views about women. We use five questions about people’s gendered attitudes. All were asked in waves prior to the wave in which the terrorist attack occurred and, therefore, are exogenous to the attack. Specifically, we measure negative views toward women through questions that ask about the endorsement of traditional gender roles, opposition to women’s equality or more women in office, whether women have an unfair advantage in the workplace, and belief in discrimination in favor of women (see Appendix C for full set of questions and responses). We scaled all responses to a 0–1 scale, coded all the questions in the same direction (with more negative views as higher values), and combined the five items into a single measure of negative views toward women.Footnote 11 The mean on the 0–1 measure is 0.39 (SD = 0.2), with bimodal peaks at 0.25 and 0.5, indicating that the sample has moderately pro-woman beliefs. We then interact this Gender Attitudes variable with the Manchester Attack. Figure 1 presents the predicted difference in pre- versus posttreatment evaluation of May’s likeability, conditional on gender attitudes (see Appendix C, Table C1). While this approach does not let us assess the effect of these gender attitudes causally on support for May, that these questions were asked in waves in the past means that we are confident that these attitudes are not being directly affected by the terrorist attack.

Figure 1. Negative Gender Attitudes and Support for May after the Manchester Attack

As expected, those with more negative views toward women are the most likely to decrease their views of May following the attack. Among those on the left-hand side of the x-axis, or who have the lowest levels of negative views toward women, the Manchester attack leads to a significant but substantively small decline in evaluations. Moving right along the x-axis, those who have the most negative views toward women are substantively most affected by the attack, decreasing their evaluations at more than three times the rate of those with positive views toward women. At the modal value on the Gender Attitudes measure, near the middle of the scale, May experiences at 0.4-point decrease in evaluations. As we show in Appendix Figure C1, the pattern of a substantively larger reaction among those with negative views toward women holds across all five questions.

A skeptical reader may be concerned that factors other than gender attitudes are driving the moderating effects. Two usual suspects are party and ideology. In addition to work cited earlier on tendencies for terrorism to benefit right-leaning and conservative parties, scholars have shown that individual ideological and partisan identities can condition terrorism’s effect (e.g., Albertson and Gadarian Reference Albertson and Gadarian2015; Peffley, Hutchison, and Shamir Reference Peffley, Hutchison and Shamir2015). Our findings are robust to models that include additional interactions between party and ideology and the Manchester attack and the triple interaction between each and gender attitudes (Appendix Figure C2). The results show strong support for the hypothesized mechanism, that postattack reactions against May were driven to a large degree by those with negative gender attitudes.

Alternative Explanations: Putting Rival Hypotheses to the Test

What other suspects are afoot in this case? In this section we consider the possibility that rival dynamics, and not May’s gender, explain the lack of a rally following the Manchester attack.

The Dog that Didn’t Bark: No Rallies in the UK Context

One possibility is that rally effects generally do not occur in the United Kingdom. There is reason to consider this alternative: research on the UK’s involvement in international conflicts in the post-World War II era through April 2001 found that very few events have produced opinion rallies (Lai and Reiter Reference Lai and Reiter2005). In terms of international conflicts during that pre-2001 period, while none produced a slump, the only cases that resulted in more satisfaction with the prime minister are the Falklands War and the Gulf War.

Yet, when we zero in on major terrorist attacks, the rally tendency is more robust and evidence shows voters in the United Kingdom take foreign affairs into account in political evaluations. In research focused on terrorist attacks, Chowanietz (Reference Chowanietz2011) finds consistent evidence of rally dynamics among opposition politicians in the UK, with major, lethal terrorist attacks producing rallies. As noted in the introduction, Tony Blair even experienced a 10-percentage-point increase in approval after the US September 11 terrorist attacks. Blair further received an increase in satisfaction ratings following the international terrorist attacks that took place on the Underground and a bus in London, which killed 52 people (BBC News 2007). And, Reifler, Scotto, and Clarke (Reference Reifler, Scotto and Clarke2011) note the importance of foreign policy attitudes in the UK for shaping views of the government more generally. In short, past major terrorist attacks led to rally dynamics that favored the sitting UK prime minister, whereas this is not the case for May.

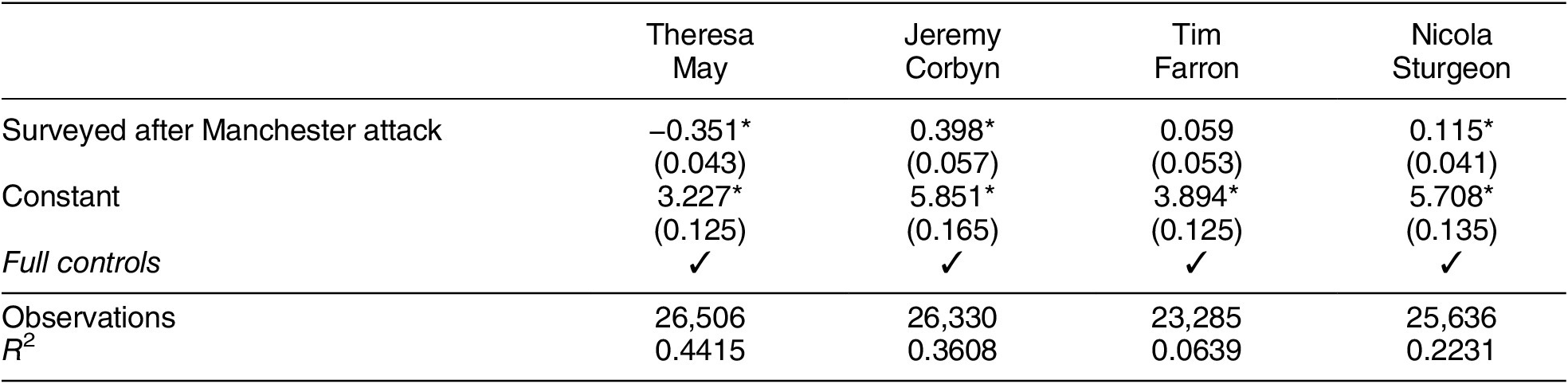

Everyone’s A Suspect: Maybe Opinion Fell across the Board after the Bombing

Perhaps dynamics around May are not unique to her as an individual, but instead the Manchester Bombing decreased favorability toward all leaders. We would then expect to see declines in evaluations of not just May’s favorability but also the favorability of others, such as Corbyn (representing Labour) or Farron (the most liberal of the candidates). And, if the politician’s party drives results, we would see leaders of the more leftwing parties lose favorability after the attack. To test this, we examine support for May’s primary Labour opponent, Jeremy Corbyn (Like Corbyn), as well as evaluations of Nicola Sturgeon (Like Sturgeon) from the Scottish National Party and Tim Farron (Like Farron) from the Liberal Democrats. Table 3 presents these results.

Table 3. Manchester Attack and View of Leaders

Note: OLS with survey weights. Clustered errors at the day of survey in parentheses. Full controls include whether someone identifies as ethnically British, gender, Labour party membership, other party membership, income, and ideology. Full results in Appendix D (Table D3). *p < 0.05.

The slump in approval is distinctly centered around May. While May’s evaluations declined, Corbyn’s evaluations increase, as do Sturgeon’s (albeit by a far smaller substantive amount). Farron’s evaluations are unaffected by the attack. The results are consistent if we include the evaluation of each leader from the previous wave as a control (see Appendix D, Table D5). A difference-in-difference approach (see Appendix D, Table D4) also reveals a negative effect for May and a positive effect for Corbyn, with null effects for Farron and Sturgeon. These results show that evaluations of May are uniquely affected by the terrorist attack, with a slump instead of a rally.

There’s Something about May?

But what if it is May herself and not her gender and position driving these effects? On face value, this seems unlikely because May represents the Conservative Party, which voters and experts see as more competent at dealing with national security (Budge and Farlie Reference Budge and Farlie1983) and as engaging in more aggressive support for the military and law and order (see Appendix D, Table D1 and Figure D1). May also had experience dealing with security issues in her time as Home Secretary, although the position focuses on domestic (versus international) issues.

One way to assess whether there is something unique about May that leads to a decline in evaluations in the face of a terrorist threat is to examine whether public opinion toward her shifted in response to national security threats prior to her ascension to the PM office. We do this with experimental data collected online in summer of 2012 with 992 UK residents selected to approximate the national adult population (see Appendix F for details of the survey).Footnote 12 The study exposed individuals to a mock news article about the threat of terrorism, or not (for our control condition).Footnote 13 Posttreatment, participants rated men and women leaders from different parties on a feeling thermometer, which ranged from 0 to 100, with higher values indicating warmer feelings. Theresa May served as Home Secretary when we fielded the survey. We find that respondents evaluate May seven points more favorably in the terror threat condition compared with the control group, and this difference is statistically significant (p = 0.003). Furthermore, the boost given to May is comparable to the boost given to all other leaders in the terror threat condition (see Appendix F, Table F3). This pattern of findings suggests that there is not something unique to May driving the findings from the Manchester attacks. Instead, what shifted was her ascension to the chief executive office. Our framework holds that this matters: women heads of government are held to higher standards, muting or reversing rally dynamics that favor their counterparts who are men.

The Scene of the Slump: Does the Electoral Context Matter?

Some might conjecture that rallies are likely with high profile terrorist attacks, but not during elections. The contentious nature of electoral campaigns could mean that the public will be less inclined to rally around the incumbent leader, especially among people who belong to other political parties. Existing research suggests otherwise (e.g., Getmansky and Zeitzoff Reference Getmansky and Zeitzoff2014), but we nonetheless consider the question as it applies to this case. Voters in the UK have structured foreign policy decisions that relate to party identification (Reifler, Scotto, and Clarke Reference Reifler, Scotto and Clarke2011), which suggests that responses to the attack might vary by which party an individual supports. If electoral dynamics are at play, we might expect the decline in May’s evaluations to be more pronounced among members of the opposite party. And if negative partisanship drove these responses (Ridge Reference Ridge2020), we would expect more pronounced effects among Labour party members.

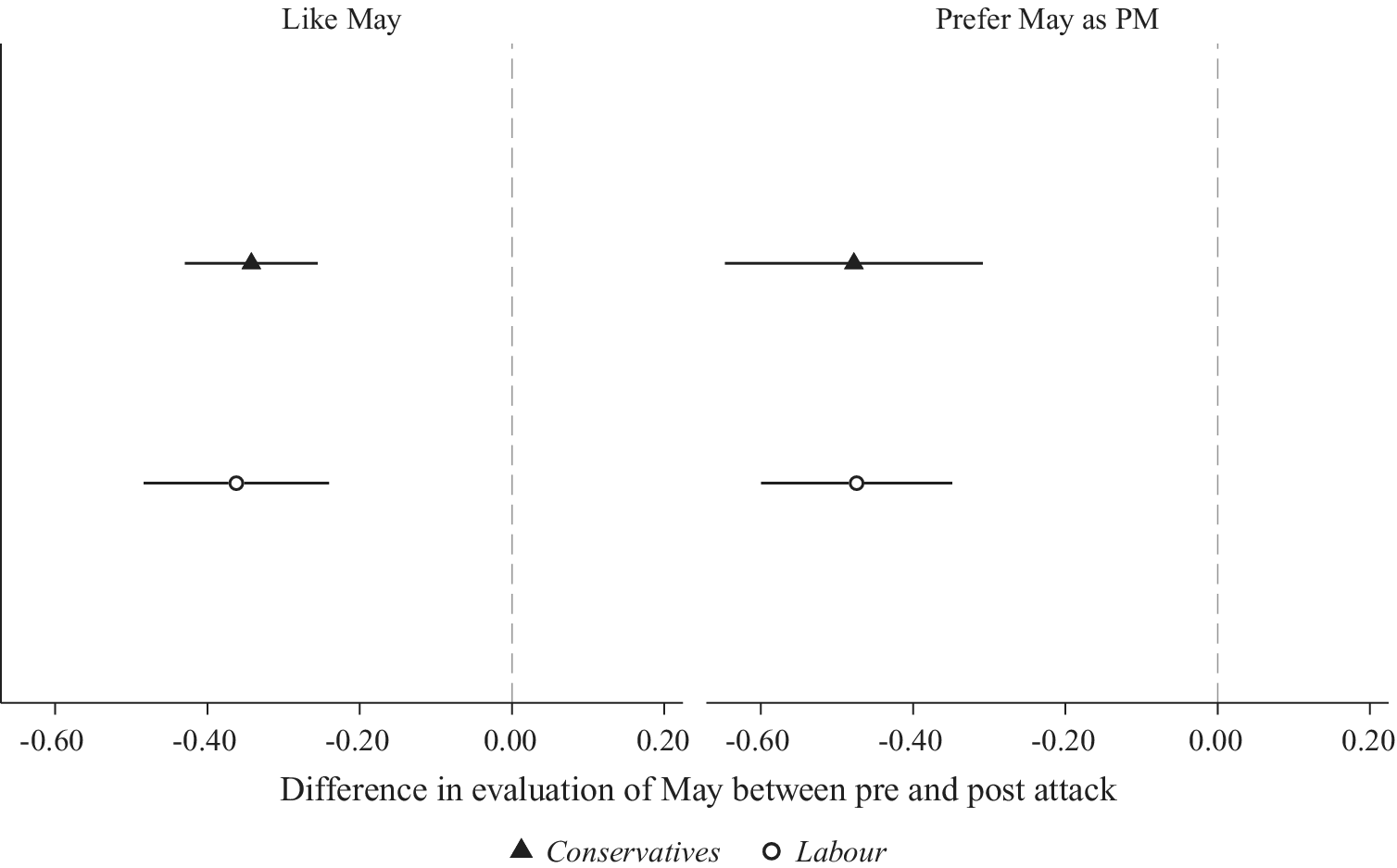

To test the role of partisanship, we estimate the effect of the Manchester attack separately for supporters of the Conservative and Labour parties. As Figure 2 shows, members of both parties reacted similarly to the attacks. In sum, it does not appear that partisan dynamics during elections are driving the drop in May’s evaluations. We also test differences by gender (finding no differences between men and women) and ideology (where both liberal and conservative voters shift their preferences, with substantively larger shifts among conservative voters); see Appendix C, Tables C3 and C4.

Figure 2. Effect of Attack on Evaluations by Party

Note: Results are post hoc predicted effects of the attack with separate models (full controls, see Appendix C, Table C2) for Conservatives and Labour.

Alternative Suspects in the Lineup

Another possibility is that alternative events occurred across the course of the election that counteracted rally effects. Perhaps May would have received a boost if not for the economy or Brexit getting in the way or perhaps we are simply capturing a downward trend in evaluations of May and the Conservative Party over the course of the election. To account for whether an economic decline is the cause of the drop in May’s evaluation in our treatment group, we include a daily control of the value of the British pound sterling in comparison to the euro (see Appendix E, Figure E1 for a visual presentation of this trend). Brexit was a central concern in the election, so a shift in attitudes about the UK’s withdrawal from the European Union could account for the drop in support for May, rather than the terrorist incident. To account for a possible effect of Brexit, we include a control for whether someone would vote “Leave” if the Brexit vote was held again, measured at the time of the survey.

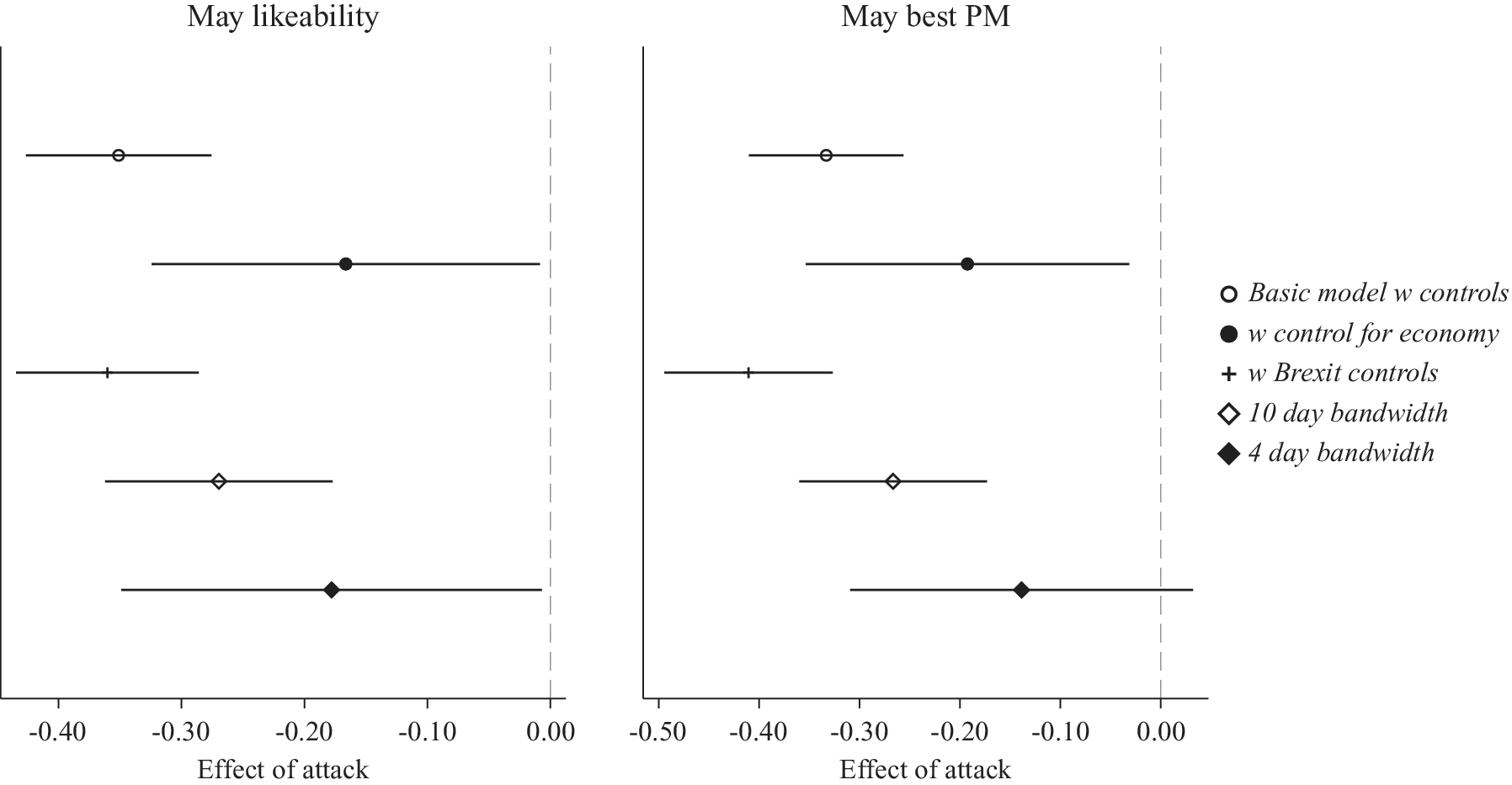

Another suspect could be a general downward trend in evaluations of May over time or some other postattack event.Footnote 14 To account for this possibility, we decrease the bandwidth around the survey, testing whether there continue to be statistically significant results if we just look at those who took the survey in the 10 days prior to and 10 days after the Manchester Attack. We then narrow the bandwidth again, to four days because the campaigns were paused for four days after the Manchester Bombing, and elites from the opposition were not actively criticizing the PM in this window, as is typical with prior attacks in the UK (Chowanietz Reference Chowanietz2011).

Figure 3 presents the effect of the attack on evaluations of May with analyses that account for the economy, Brexit, and reduced bandwidths, with our base models with controls from Table 1 for comparison purposes (hollow circle). The Manchester Bombing produces a slump instead of a rally even when controlling for a daily accounting of the economy (solid circle), Brexit attitudes (plus sign), and when shrinking the bandwidth to 10 (hollow diamond) or 4 (solid diamond) days for both evaluations of May’s likeability (left pane) and preference for her as prime minister (right pane).

Figure 3. Effect of the Attack on Evaluations of May with Alternative Tests

Note: Figure presents post hoc predicted effects from OLS (right pane) and logit (left pane) models with full controls (see Appendix E, Table E2).

Guilty by Association: Downstream Consequences for the Party

Approval ratings matter because they help politicians move their agendas forward, and they translate into votes not only for the specific leader but also for that leader’s party (e.g., Canes-Wrone and de Marchi Reference Canes-Wrone and De Marchi2002; Donovan et al. Reference Donovan, Kellstedt, Key and Lebo2020). If terrorist attacks result in a backlash against a woman executive, we could expect to see not only decreased evaluations of that leader but also negative vote outcomes for her party.

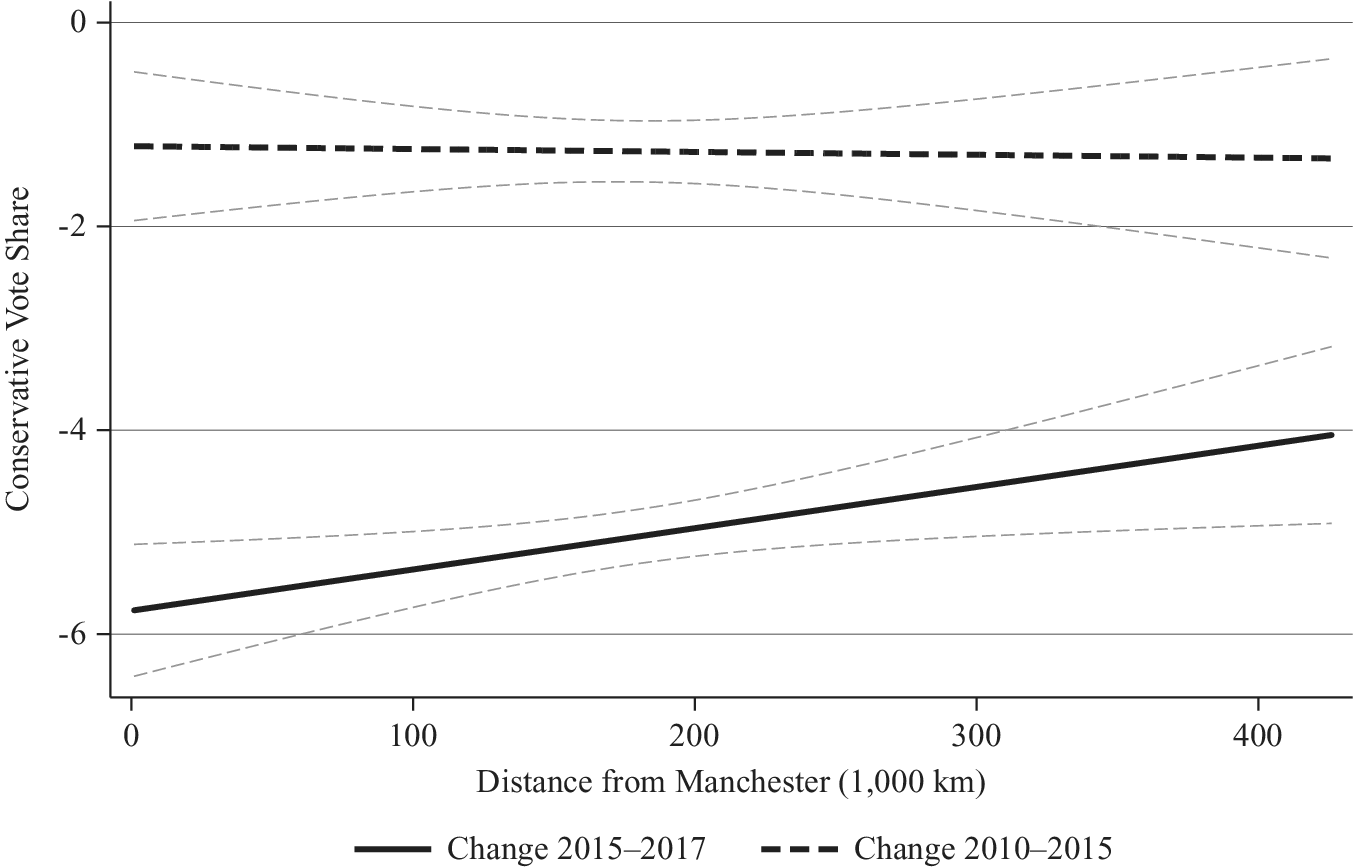

To test the consequences of the Manchester Arena attack for May’s Conservative Party, we use constituency-level election returns (Kollman et al. Reference Kollman, Hicken, Caramani, Backer, Lublin, Selway and Vasselai2019). Because the election itself is one point in time, we follow other research that evaluates the effect of terrorism by distance to the attack (Hersh Reference Hersh2013). To do so, we leverage variation in geography and assess whether distance from the Manchester Bombing shapes outcomes.

Our dependent variable is the share of the vote received in a constituency by the Conservative Party in 2017 minus the share of the vote received in the 2015 election (Change 2015–17). As a placebo test, we also examine the change in the vote received by the Conservative Party from the 2010 to 2015 election (Change 2010–15). Both dependent variables are coded so that positive values mean that the Conservatives gained in that constituency compared with the previous election. Our key independent variable is the standardized distance from Manchester to the middle point of each constituency.

As Figure 4 shows, we find a significant and positive relationship in the change from 2015 to 2017 and distance to Manchester (one-tailed test, p = 0.079), a result that is consistent with voters punishing May’s party because of the attack, as communities closer to Manchester were less likely to support the Conservative Party. In contrast, there is no significant effect for the placebo test: the effect of distance to Manchester has no significant relationship with the 2010–2015 Conservative vote share change. These results demonstrate the reach of the slump-not-bump dynamic: not only do lower evaluations disadvantage May following the Manchester Bombing, but her party suffers as well.

Figure 4. Vote Change for the Conservative Party by Distance to Manchester

Note: Post hoc predicted values from OLS models of constituency-level change in votes for the Conservative Party (in England only) with controls for constituency population, Brexit vote share, along with share of the population that is ethnically British, over the age of 65, born in the UK, Christian, and unemployed. Full results available in Appendix G, table G1.

Moving the Investigation Abroad

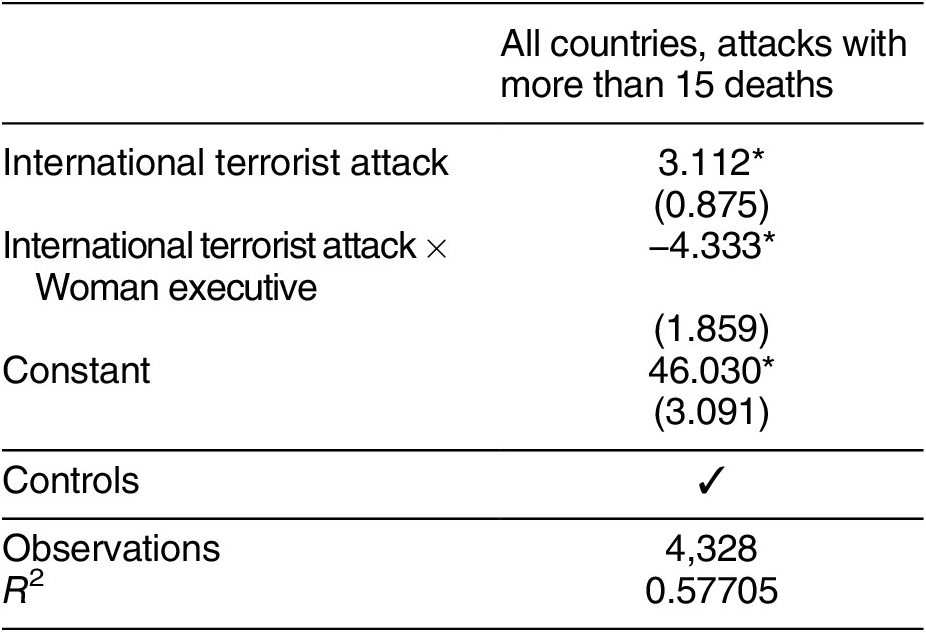

The Manchester Bombing is a critical case, and the BES data permit us to assess our framework with a large-N dataset, subnational analyses, and a variety of alternative tests. Yet, an obvious question is the following: does the gender-revised rally theory hold for a broader dataset that includes variation in the gender of executives confronting major international terrorist attacks? To engage in a broader analysis, we turn to quarterly data on executive approval (Carlin, Carreras, and Love Reference Carlin, Carreras and Love2020), international terrorist attacks (GTD 2019), and a measure of whether a woman or a man is lead executive. The pooled dataset with these measures includes 66 countries and spans from 1975 to 2017 (4,359 country-quarters); 20 countries had a woman leading the country during this period.

To assess whether women benefit from rally effects, we first needed to identify major international terrorist attacks that should produce a rally effect in executive approval. We define this as any attack that involved an international component (using the definition from the Global Terrorism Database) and had more than 15 deaths.Footnote 15 The dataset contains 60 country-quarters with such an attack. As expected, there are a relatively low number of women national executives: of these quarters, only nine are under women leaders (Cory Aquino, Theresa May, and Margaret Thatcher).Footnote 16 We then use a time-series cross-sectional approach to examine the percentage of the public that approves of the executive in the quarterFootnote 17 following an attack and we interact the attack dummy with the presence of a woman executive. We include country fixed effects so that we are estimating the change in approval from quarter to quarter. We examine executive approval in the quarter following the attack because we cannot be sure when approval data is collected within any given quarter. Following the executive approval scholarship (e.g., Carlin, Carreras, and Love Reference Carlin, Carreras and Love2020), we control for country GDP growth, a logged measure of inflation, the left-right ideological placement of the executive,Footnote 18 and whether an election occurred in that year.

We find evidence in support of the gender-revised rally theory: Table 4 shows that while large-casualty international terrorist attacks are associated with an increase in approval ratings for men as leaders, this is not true for women leaders. Instead, we see a significant decrease in women’s approval ratings after a terrorist attack. The effects on men’s increased approval (3.1 points) and women’s decreased approval (4.3 points) are substantively meaningful. To be sure, there is heterogeneity across cases as other factors contribute to public opinion dynamics following terrorist attacks, yet the analyses affirm that the mean tendency is for the public to rally when the executive is a man and the converse when the executive is a woman.Footnote 19

Table 4. Effect of Terrorist Attacks on Executive Approval Ratings

Note: Linear regression using time-series cross-sectional data of country-quarters. Controls for the presence of a woman executive, GDP, inflation (logged), the left-center-right placement of the leader, and election in that year, with country fixed effects. Panel-corrected standard errors in parentheses. Dataset includes all countries in the executive approval database that also appear in the Global Terrorism Database (N countries = 66). Full results in Appendix H, Table H1. *p < 0.05.

Conclusion

The conventional rally ‘round the flag theory was developed through an informed inductive process, in which a set of trends consistent with ideas in prior scholarship emerged as “one stares at Presidential popularity trend lines long enough” (Mueller Reference Mueller1970, 19). The notion that public opinion rallies in favor of executives facing “specific, dramatic, and sharply focused” events with an international component makes theoretical sense: these events jar public opinion toward in-group consolidation around the highest office in the nation (e.g., Kam and Ramos Reference Kam and Ramos2008). We do not contest the notion that this inclination exists, yet we argue that the theory was developed without consideration of the ways in which such an inclination may be comparatively lower or entirely undermined by gender bias. The trend lines that Mueller examined were for men in political office, and subsequent scholarship on rallies has largely ignored the possibility of gender dynamics. The classic rally ‘round the flag theory needs to be revised in light of scholarship on women in politics. As part of that effort, we home in on one type of event theorized to produce a strong rally: a major, lethal terrorist attack on home soil by perpetrators with an international allegiance. Using research from gender and politics as our foundation, our gender-revised framework asserts that women executives are at a disadvantage in such cases as bias enters to mute, stymie, or reverse the theorized rally.

We assess the thesis with survey data collected in the UK, before and after a horrific attack at the Manchester Arena in 2017 by an Islamist extremist attacker allegiant to international terrorist groups. The scarcity of cases of women executive leaders facing such incidents is a challenge for theory testing, yet this case’s features make it ideal. First, the executive—Theresa May—led a right-leaning party and had experience in security, both factors that contribute to this being a “most likely” case for a rally event. Second, the large sample of high quality data gathered through the British Election Study’s rolling panel design permits multiple ways to assess the contention that PM May would be at a public opinion disadvantage. Third, the data permit tests of gender bias as the theorized mechanism and rival explanations.

In analyses of the BES data, we find that May’s popularity declined following the attack, and we show that this decline was concentrated among those with negative views of women. Using additional tests, we can dismiss a variety of plausible rival explanations. We further show that the slump affected May’s Conservative Party in elections following the attack, with the party securing comparatively fewer votes in locations more proximate to the attack. Finally, we put our core hypothesis to a global test and find, again, support for the gender-revised rally framework.

We note the argument is probabilistic, as many factors other than gender shape how the public responds to terrorism and understandings of masculinity and femininity vary across cultures and time (Ortbals and Poloni-Staudinger Reference Ortbals and Poloni-Staudinger2018a). In other words, that women executives may experience slumps-not-bumps when facing major national security crises does not mean that they will always fail to receive a rally. Rather, what it means is that, on average, women executives will be less likely to experience a robust rally effect compared with their counterparts who are men. Understanding these dynamics matters because executive approval matters: it provides the political currency that leaders need to achieve their goals in office (e.g., Canes-Wrone and De Marchi Reference Canes-Wrone and De Marchi2002; Donovan et al. Reference Donovan, Kellstedt, Key and Lebo2020) and can have downstream consequences for the leader’s party (Lebo and Norpoth Reference Lebo and Norpoth2013).

But, if rally dynamics are heterogeneous across leaders and contexts, why focus in on executive gender and gender attitudes? Reactions to terrorism-related rally events can vary by other factors. One of these is political actors’ ideology, with right-leaning candidates and parties more likely to receive a rally (Berrebi and Klor Reference Berrebi and Klor2008; Chowanietz Reference Chowanietz2011; Getmansky and Zeitzoff Reference Getmansky and Zeitzoff2014). Divisive foreign policy stances can also alter rally dynamics. Following the March 11, 2004, bombings in Spain that killed nearly 200 persons, the incumbent party was defeated at the polls three days later. Scholarship on this case points to the relevance of the incumbent party’s hotly contested foreign policy position, which was seen as provoking the attack (Bali Reference Bali2007; Montalvo Reference Montalvo2011).Footnote 20 Other scholarship considers heterogeneity within the public, such as by partisanship and education (Baum Reference Baum2002). Our research connects to this broader body of research on heterogeneity by putting a spotlight on gender. We do so to address an asymmetry: a rich body of work theorizes and demonstrates the ways in which gendered evaluations intersect with political evaluations, including in contexts of threat and violence, yet considerations of gender have been effectively absent from scholarship on rally ‘round the flag dynamics.

Our focus has been on one particular type of event that has been theorized and shown to robustly predict public opinion rallies. Future research ought to consider the extent to which gender bias counters the potential for, or the size of, rallies in other cases (e.g., international conflicts) and also whether there are situations in which women executives are able to hold gender bias at bay, and how so. The degree to which the public holds women to different standards in an economic or public health crisis (such as the COVID-19 pandemic, for example) is worthy of additional study. It may be, in fact, that women executives are more prone to receive rallies under certain national crises. An additional topic worthy of more consideration is whether the type of victim matters, in general and with respect to how that interacts with the gender of the executive. For example, that young, predominately white, women made up many of the victims in the Manchester Bombing might have influenced public sentiment about the attack. In conclusion, to the extent that gender continues to shape the public’s evaluations of politicians, it is important to revise our theories about when and how publics rally—or not—around incumbent leaders facing critical moments.

Supplementary Materials

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055421000861.

Data Availability Statement

Research documentation and data that support the findings of this study are openly available at the American Political Science Review Dataverse: doi.org/10.7910/DVN/VHNPUO.

Acknowledgments

Paper previously presented at the Vanderbilt Faculty Workshop. Thanks to the participants of that workshop, as well as to Caitlin Andrews-Lee, Christina Xydias, Bethany Albertson, Kirsten Rodine Hardy, and Amanda Kass for their feedback on the paper.

Funding Statement

This research was funded in part by the National Science Foundation research awards SES-0851136 and SES-0850824.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no ethical issues or conflicts of interest in this research.

Ethical Standards

The authors affirm that this article adheres to the APSA’s Principles and Guidance on Human Subject Research. The 2012 experimental study received Human Subjects Approval from the Institutional Review Boards at Claremont Graduate University and Vanderbilt University.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.