Introduction

In the course of a study by scanning electron microscopy with energy-dispersive spectrometry (SEM-EDS), ore microscopy and single-crystal X-ray diffraction (SCXRD) of a heavy concentrate obtained from ore samples collected at the Konder alkaline-ultrabasic massif, Khabarovsk Krai, Far East, Russia (57° 35’ 12’’ N, 134° 39’ 9’’ E), the senior author of the present paper encountered an array of rare PGE-bearing minerals. Amongst them one unknown phase gave essential Pd, Bi, Te, minor Ag, As, Sb and Pb using SEM-EDS and unit-cell parameters similar to the mineral mertieite-II, ideally Pd8Sb2.5As0.5 (Karimova et al., Reference Karimova, Zolotarev, Evstigneeva and Johanson2018), later renamed to mertieite by the Commission on New Minerals, Nomenclature and Classification (CNMNC) of the International Mineralogical Association (IMA) (Miyawaki et al., Reference Miyawaki, Hatert, Pasero and Mills2022). Further investigations showed this phase to be a new mineral isotypic to mertieite. It was named vadlazarenkovite in the honour of Professor Vadim Grigorievich Lazarenkov (Вадим Григорьевич Лазаренков) (1933–2014), Soviet and Russian scientist who worked at the Saint-Petersburg Mining University, for his outstanding contributions to the geology and petrology of ultrabasic and basic rocks, including those from the Konder deposit, as well as to the geochemistry and mineralogy of PGE (see Lazarenkov and Malich, Reference Lazarenkov and Malich1992; Lazarenkov et al., Reference Lazarenkov, Malich and Sakhyanov1992; Lazarenkov and Talovina, Reference Lazarenkov and Talovina2001; Lazarenkov et al., Reference Lazarenkov, Petrov and Talovina2002 etc.). The name ‘vadlazarenkovite’ was preferred to ‘lazarenkovite’ to avoid confusion with the existing mineral lazarenkoite, CaFe3+As3+3O7·3H2O (Yakhontova and Plusnina, Reference Yakhontova and Plusnina1981). The new mineral, its name and symbol (Vlz) have been approved by the CNMNC of the IMA (IMA2023–040, Kasatkin et al., Reference Kasatkin, Biagioni, Nestola, Agakhanov, Stepanov, Petrov and Pilugin2023). The holotype specimen is deposited in the systematic collection of the Fersman Mineralogical Museum of the Russian Academy of Sciences, Moscow, with the catalogue number 98319.

To date, the Konder massif is the type locality of four mineral species – konderite (Rudashevskiy et al., Reference Rudashevskiy, Mochalov, Trubkin, Gorshkov, Men’shikov and Shumskaya1984), cuproiridsite (Rudashevskiy et al., Reference Rudashevskiy, Men’shikov, Mochalov, Trubkin, Shumskaya and Zhdanov1985), bortnikovite (Mochalov et al., Reference Mochalov, Tolkachev, Polekhovskiy and Goryacheva2007) and ferhodsite (Begizov and Zavyalov, Reference Begizov and Zavyalov2016). All of them contain PGE as species-defining components. Thus, vadlazarenkovite is the fifth new mineral discovered there.

Occurrence and general appearance

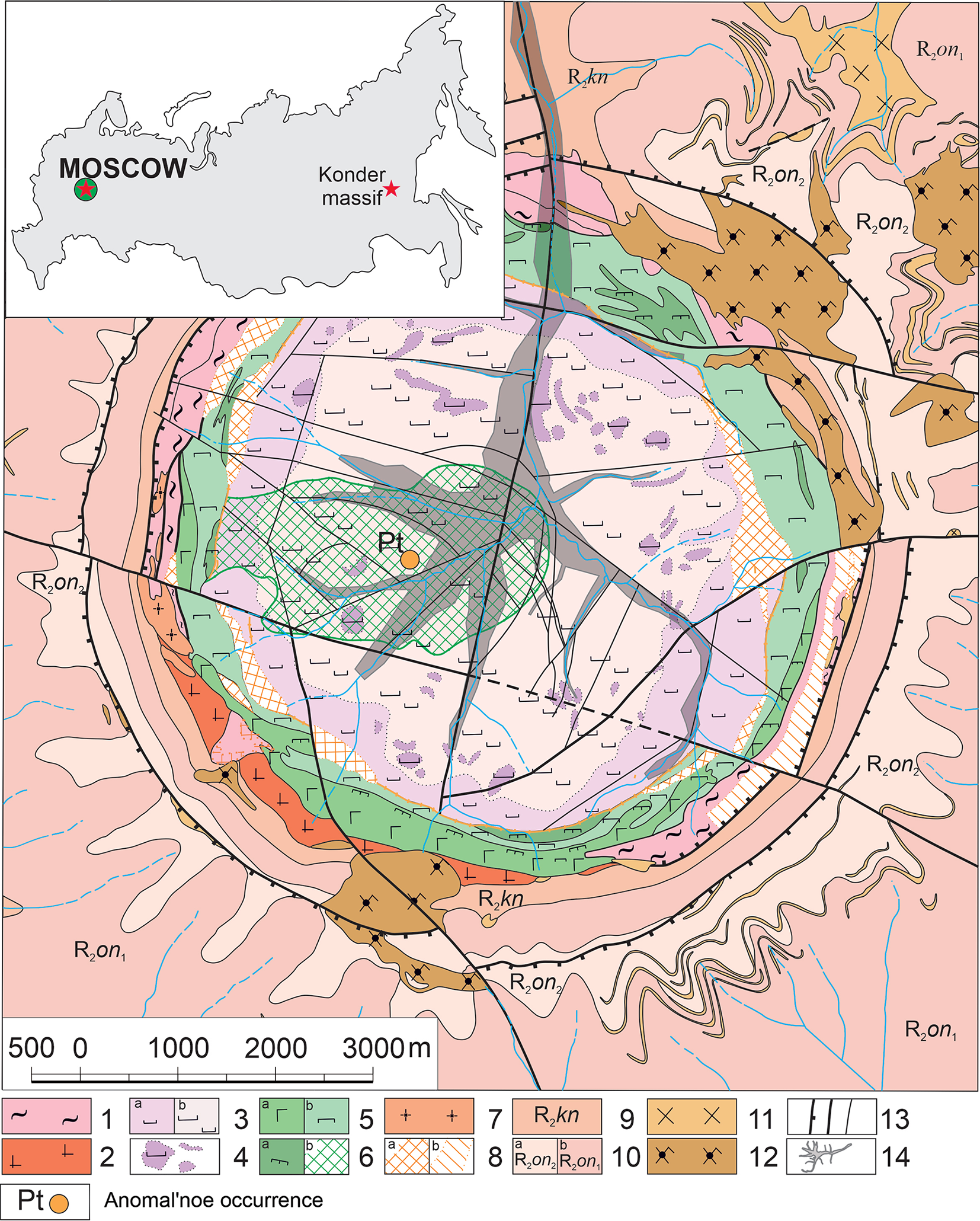

The Konder (alternative spelling – Kondyor) massif is located at the Eastern margin of the Aldan shield within a sub-latitudinal zone of a Proterozoic continental rift. This zone crosses the Batomga ledge of the crystalline basement at its intersection with the Konder-Netsky sublongitudinal fault (Gurovich et al., Reference Gurovich, Emelyanenko, Zemlyanukhin, Karetnikov, Kvasov, Lazarenkov, Malich, Mochalov, Prikhod’ko and Stepashko1994). The massif is composed of Early Proterozoic rocks of the Konder dunite–clinopyroxenite–gabbro complex and Early Cretaceous rocks of the Ketkap monzodiorite plutonic complex (Dymovich et al., Reference Dymovich, Vas’kin, Opalikhina, Kislyakov, Atrachenko, Romanov, Zelepugin, Charov and Leontieva2012) and represents a subvertical diapir (or stock) with almost perfectly circular projection, which is bounded by circular faults (Fig. 1). The Konder massif has a concentrically-zoned structural pattern and is composed of a dunite core (diameter 5.1–6 km, area 24.7 km2) and a relatively thin (up to 850 m in thickness) rim of clinopyroxenites, ore clinopyroxenites (kosvites) and gabbros. The dunite body is also zoned, and its zonation is manifested in a transition of fine-grained to medium- and coarse-grained varieties through porphyric ones. The Konder massif is a source of one of the world’s largest placer deposits of platinum (Lazarenkov et al., Reference Lazarenkov, Petrov and Talovina2002). Since its exploration began in 1984, more than 106 tons of platinum have been recovered from the related placers (Pilyugin and Bugaev, Reference Pilyugin and Bugaev2016). This deposit is also renowned for discoveries of many large platinum nuggets (Mochalov, Reference Mochalov2019).

Figure 1. Geographical position (inset) and geological map of the Konder massif. 1 – crystalline schists, marbles, quartzites and gneisses of the Utukachan Formation (Ar1ut); 2 – gneiss-like plagiogranites of the Hoyundin Formation (pγAR1h); 3 – dunites: (a) fine-grained and (b) porphyric; 4 – dunite pegmatites; 5 – mafic rocks: (a) gabbro, (b) clinopyroxenites; 6 – (a) apatite-magnetite ore clinopyroxenites (kosvites) and (b) a stockwork of Ti-magnetite phlogopite clinopyroxenites with zeolites and copper sulfide mineralization; 7 – medium-alkaline pegmatoidal granites; 8 – metasomatites: (a) diopside-monticellite-garnet and diopside-forsterite metasomatites and (b) feldspar-clinopyroxene; 9 – siltstones, sandstones and gravelites of the Konder Formation; 10 – terrigenous sedimentary rocks of the Omnin Formation of the lower (a) and upper (b) subformations; 11 – monzodiorites and monzonites of the Ketkap complex; 12 – quartz monzonites of the Ketkap complex; 13 – faults; and 14 – industrial debris of the Konder Pt placer deposit.

Lately, presumably economic PGE concentrations have been documented in veins of zeolite- and amphibole-bearing phlogopite clinopyroxenites, which host fine-grained copper sulfide mineralisation. Drilling prospection of a complex Cu–Pt–Pd geochemical and magnetic geophysical anomaly in 2013–2014 revealed a Cu–Pt–Pd ore occurrence named Anomal’noe (Gurevich and Polonyankin, Reference Gurevich and Polonyankin2016; Pilyugin and Bugaev, Reference Pilyugin and Bugaev2016). The geological structure of this mineralised area is characterised by the broad presence of Ti-magnetite clinopyroxenites with related metasomatic rocks (Fig. 2), which always cross-cut dunites and form a stockwork in western and central parts of the dunite core. The largest bodies of Ti-magnetite clinopyroxenites have a subhorizontal or slightly dipping strike. These clinopyroxenites are rich in phlogopite (possibly late-stage) and have coarse-grained sideronitic and, occasionally, breccia-like textures. Cu–Pt–Pd mineralisation is localised exclusively within veins, composed by phlogopite, clinopyroxene and zeolites. These veins are steeply dipping, have relatively small lengths (up to 100–200 m) and thicknesses (1–4 m on average). Copper sulfides mainly include fine-grained segregations of bornite, chalcopyrite and chalcocite. PGE-bearing minerals coexist with copper sulfides and form isolated inclusions of small size (0.12 mm on average). The latter usually represent complex intergrowths of different PGE-bearing minerals: intermetallic compounds, sulfides, arsenides and tellurides. According to our data (unpublished), palladium concentration in the veins is up to 63.7 g/t, platinum – up to 33.7 g/t, gold – 1.3 g/t and silver – more than 100 g/t.

Figure 2. Cross-section of the central part of the Anomal’noe ore occurrence: 1 – porphyric dunites, 2 – Ti-magnetite clinopyroxenites equally-grained and porphyric, and their phlogopite and apatite varieties; 3 – vein of clinopyroxene–phlogopite, phlogopite, phlogopite–clinopyroxene and zeolite–clinopyroxene–phlogopite rocks; 4 – weathering crust after the bedrocks, 5 – faults, 6 – boreholes.

A more detailed description of the Konder massif, its geology and mineralogy can be found elsewhere (Gurovich et al., Reference Gurovich, Emelyanenko, Zemlyanukhin, Karetnikov, Kvasov, Lazarenkov, Malich, Mochalov, Prikhod’ko and Stepashko1994; Cabri and Laflamme, Reference Cabri and Laflamme1997; Malich, Reference Malich1999; Shcheka et al., Reference Shcheka, Lehmann, Gierth, Gömann and Wallianos2004; Simonov et al., Reference Simonov, Kovyazin and V.S2011; Tolstykh, Reference Tolstykh2018; Mochalov, Reference Mochalov2019 etc.).

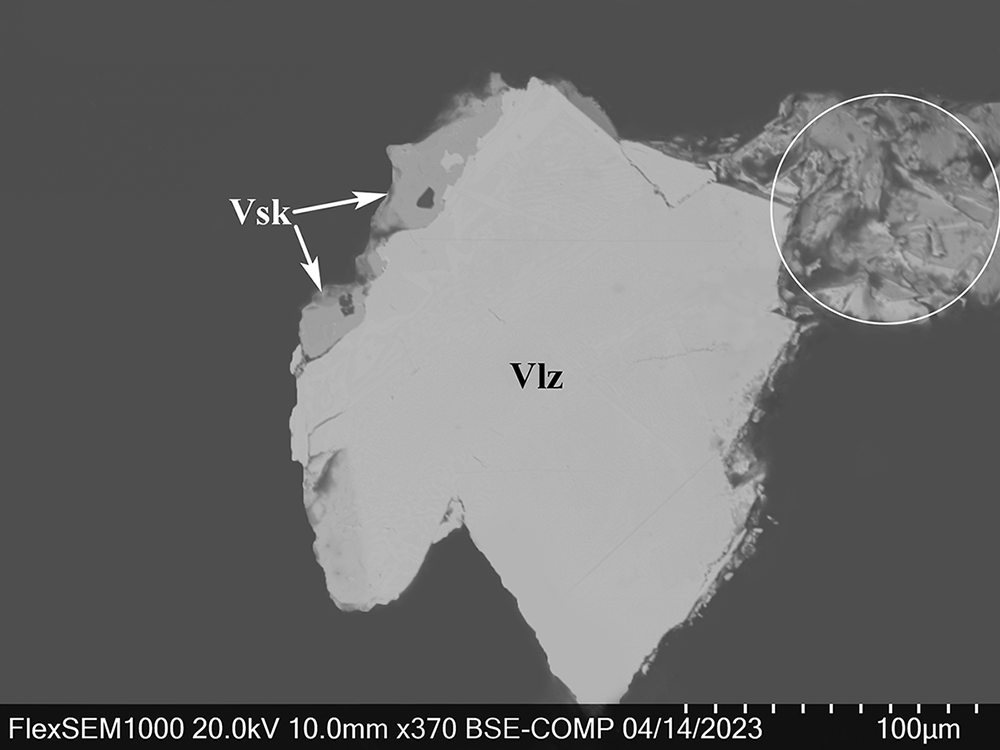

Vadlazarenkovite was found in a heavy concentrate obtained from ore samples collected at the Anomal’noe ore occurrence during field works at the deposit in 2014–2018. The new mineral occurs as anhedral grains up to 0.15 × 0.15 mm intergrown with vysotskite, ideally PdS (Fig. 3). Associated PGE-bearing minerals include arsenopalladinite, cooperite, ezochiite, hollingworthite, isomertieite, kotulskite, laurite, malanite, norilskite, polarite, Zn-bearing skaergaardite, sobolevskite, sperrylite, stillwaterite, törnroosite, tulameenite, vysotskite and zvyagintsevite. Several PGE-bearing phases in the same association are unknown and are currently under investigation. Other associated minerals include anilite, bornite, chalcocite, chalcopyrite, chromite, cubanite, digenite, galena, Cr-bearing magnetite, silver, stromeyerite and phlogopite.

Figure 3. Vadlazarenkovite (Vlz) intergrown with vysotskite (Vsk). Part of this grain (in white circle) was extracted for structural studies. Polished section. SEM (BSE) image, holotype catalogue number 98319.

Vadlazarenkovite is extremely rare: only two grains of the mineral have been found so far, 0.15 × 0.15 mm and 0.05 × 0.01 mm.

Physical properties and optical data

Vadlazarenkovite is grey, opaque with metallic lustre, brittle tenacity and uneven fracture. It does not fluoresce under ultraviolet light. No cleavage and parting are observed. The Vickers’ micro-indentation hardness (VHN, 50 g load) is 424 kg/mm2 (range 406–443, n = 4), corresponding to a Mohs’ hardness of 4.5–5. Density could not be measured due to the very small amount of available material and absence of necessary heavy liquids. A density value calculated using the empirical formula and the unit-cell parameters from SCXRD data is 11.947 g cm–3.

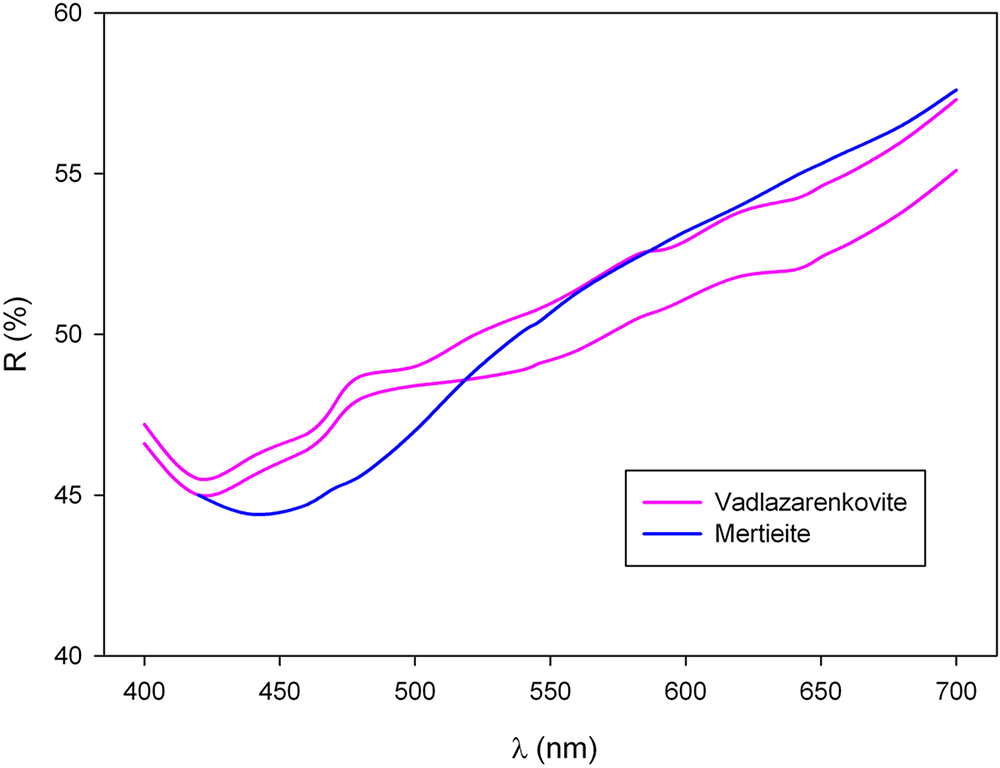

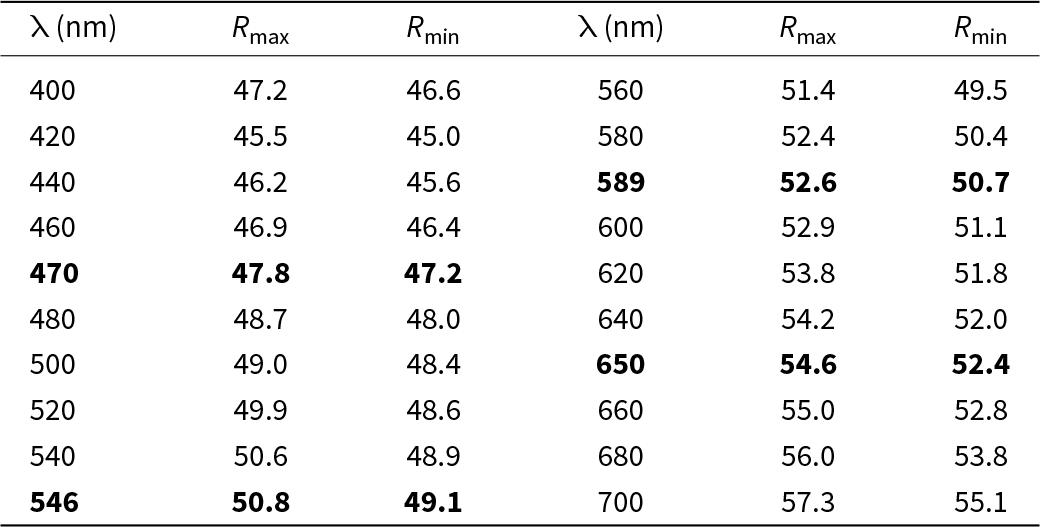

In reflected light, vadlazarenkovite is white with a pale creamy hue. The bireflectance is weak in air and noticeable in oil immersion. No pleochroism or internal reflections were observed. In crossed polars the new mineral exhibits distinct anisotropy in grey tones. Reflectance values have been measured in air using an MSF-R (LOMO, Saint-Petersburg, Russia) microspectrophotometer. Silicon was used as a standard. The reflectance values (R max/R min) are given in Table 1 and plotted in Fig. 4 in comparison with the published data for mertieite (Cabri, Reference Cabri1981). Note that reflectance curves of both minerals have close resemblance with a clearly defined dispersion of anomalous type, however, for vadlazarenkovite the minimum is in the violet part of the spectrum (420 nm), while for mertieite it is shifted to the right, into the blue region (450 nm).

Figure 4. Reflectance curves of vadlazarenkovite (holotype sample) in comparison with mertieite (Cabri, Reference Cabri1981).

Table 1. Reflectance values for vadlazarenkovite (COM standard wavelengths are given in bold).

Composition

Chemical data (six spot analyses) were collected with a Tescan Solari FEG-SEM equipped with WDS Wave 700 Oxford Instruments (25 kV, 10 nA and 2 μm beam size). Contents of other elements with atomic numbers > 4 are below detection limits. Matrix correction using the PAP algorithm (Pouchou and Pichoir, Reference Pouchou, Pichoir and Armstrong1985) was applied to the data. Analytical data and a list of standards are given in Table 2.

Table 2. Chemical data (in wt.%) and atoms per formula unit (apfu) for vadlazarenkovite.

The empirical formula calculated on the basis of 11 atoms per formula unit is (Pd7.87Ag0.27)Σ8.14(Bi1.26Te1.16As0.22Pb0.16Sb0.06)Σ2.86. The ideal formula of vadlazarenkovite, considering the results of the crystal structure analysis (see below), is Pd8Bi1.5Te1.25As0.25, which requires (in wt.%) Pd 63.39, Bi 23.34, Te 11.88, As 1.39, total 100.

X-ray crystallography and crystal structure

Powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD) data were collected using a Rigaku R-AXIS Rapid II single-crystal diffractometer equipped with a cylindrical image plate detector (radius 127.4 mm) using Debye-Scherrer geometry, CoKα radiation (rotating anode with VariMAX microfocus optics), 40 kV and 15 mA. Angular resolution of the detector is 0.045°2θ (pixel size 0.1 mm). The data were integrated using the software package Osc2Tab (Britvin et al., Reference Britvin, Dolivo-Dobrovolsky and Krzhizhanovskaya2017). PXRD data of vadlazarenkovite are given in Table 3 in comparison to that calculated from SCXRD data using the PowderCell2.3 software (Kraus and Nolze, Reference Kraus and Nolze1996). Parameters of trigonal unit cell were calculated from the observed d spacing data using UnitCell software (Holland and Redfern, Reference Holland and Redfern1997) and are as follows: a = 7.722(4), c = 43.11(4) Å, and V = 2226(2) Å3. It should be noted that due to the lack of material, PXRD data were collected from the same grain which was used for SCXRD studies (see below). This issue with the preferential orientation of the single crystal during PXRD data collection also introduces a difference in the intensity of the peaks in the observed and calculated powder diffraction patterns while maintaining their angular positions (Table 3).

Table 3. Powder X-ray diffraction data (d in Å) of vadlazarenkovite.

* I calc, d calc were calculated using the PowderCell2.3 software (Kraus and Nolze, Reference Kraus and Nolze1996) on the basis of the structural model given in Table 5. Only reflections with I calc > 5 are listed.

The strongest reflections are given in boldtype.

For the SCXRD study, a grain of vadlazarenkovite, 0.024 × 0.020 × 0.016 mm in size, extracted from the polished section used for electron microprobe analyses (Fig. 3), was mounted on a glass fibre and examined through a Supernova Rigaku-Oxford Diffraction diffractometer equipped with a micro-source MoKα radiation (λ = 0.71073 Å; 50 kV and 0.8 mA) and a Pilatus 200K Dectris detector. The data were processed by CrysAlisPro 1.171.41.123a software (Rigaku Oxford Diffraction) and are as follows: vadlazarenkovite is trigonal, space group R ![]() $\bar 3$c, a = 7.7198(2), c = 43.1237(11) Å, V = 2225.66(13) Å3 and Z = 12. Intensity data were collected using φ scan modes, in 1° slices, the sample-to-detector distance was set to 69 mm, with an exposure time of 25 s per frame. A total of 1689 frames over 30 runs were collected for a total time of about 12 hours. Data were corrected for Lorentz-polarisation, absorption, and background. Unit-cell parameters were refined on the basis of the XYZ centroids of 5028 reflections with 3 < θ < 31.7°.

$\bar 3$c, a = 7.7198(2), c = 43.1237(11) Å, V = 2225.66(13) Å3 and Z = 12. Intensity data were collected using φ scan modes, in 1° slices, the sample-to-detector distance was set to 69 mm, with an exposure time of 25 s per frame. A total of 1689 frames over 30 runs were collected for a total time of about 12 hours. Data were corrected for Lorentz-polarisation, absorption, and background. Unit-cell parameters were refined on the basis of the XYZ centroids of 5028 reflections with 3 < θ < 31.7°.

The crystal structure of vadlazarenkovite was refined using Shelxl-2018 (Sheldrick, Reference Sheldrick2015) starting from the atomic coordinates of mertieite (Karimova et al., Reference Karimova, Zolotarev, Evstigneeva and Johanson2018). The following neutral scattering curves, taken from the International Tables for Crystallography (Wilson, Reference Wilson1992), were used: Pd at Pd1–Pd4 sites, Bi at Bi1 (Sb1 in Karimova et al., Reference Karimova, Zolotarev, Evstigneeva and Johanson2018), Te at M1 and M2 (M1 and As1 in Karimova et al., Reference Karimova, Zolotarev, Evstigneeva and Johanson2018). Several cycles of isotropic refinement converged to R 1 = 0.1016, thus confirming the correctness of the structural model. At this stage of the refinement, the U iso value at the M1 site was too low, suggesting the occurrence of heavier atoms. Consequently, the site occupancy at this position was refined using the scattering curves of Bi vs. Te. The refinement improved to R 1 = 0.0815. After several cycles of anisotropic refinement, the R 1 factor converged to 0.0416. At this stage, the site occupancies at Bi1 and M2 were refined, using the scattering curves of Bi vs. □ and Te vs. □, respectively (□ = vacancy). The Bi1 and M2 sites were found to be occupied by lighter atoms, and in the final stage of the refinement, their site occupancies were refined using the scattering curves of Bi vs. Te and Te vs. As, respectively. Owing to the similar scattering factors of Bi (Z = 83) and Pb (Z = 82), and of Te (Z = 52), Sb (Z = 51) and Ag (Z = 47), the actual distribution of Pb, Sb and Ag in the crystal structure of vadlazarenkovite was only hypothesised and these elements were not included in the refinement. The final anisotropic structural model converged to R 1 = 0.0267 for 761 reflections with F o > 4σ(F o) and 39 refined parameters. Details of data collection and refinement are given in Table 4. Fractional atom coordinates and equivalent isotropic displacement parameters are reported in Table 5. Table 6 reports selected interatomic distances. The crystallographic information file has been deposited with the Principal Editor of Mineralogical Magazine and is available as Supplementary material (see below).

Table 4. Crystal and experimental data for vadlazarenkovite.

Table 5. Site, site occupancy (s.o.), fractional atom coordinates, equivalent isotropic displacement parameters (Å2) for vadlazarenkovite.

Table 6. Selected interatomic distances (in Å) for vadlazarenkovite.

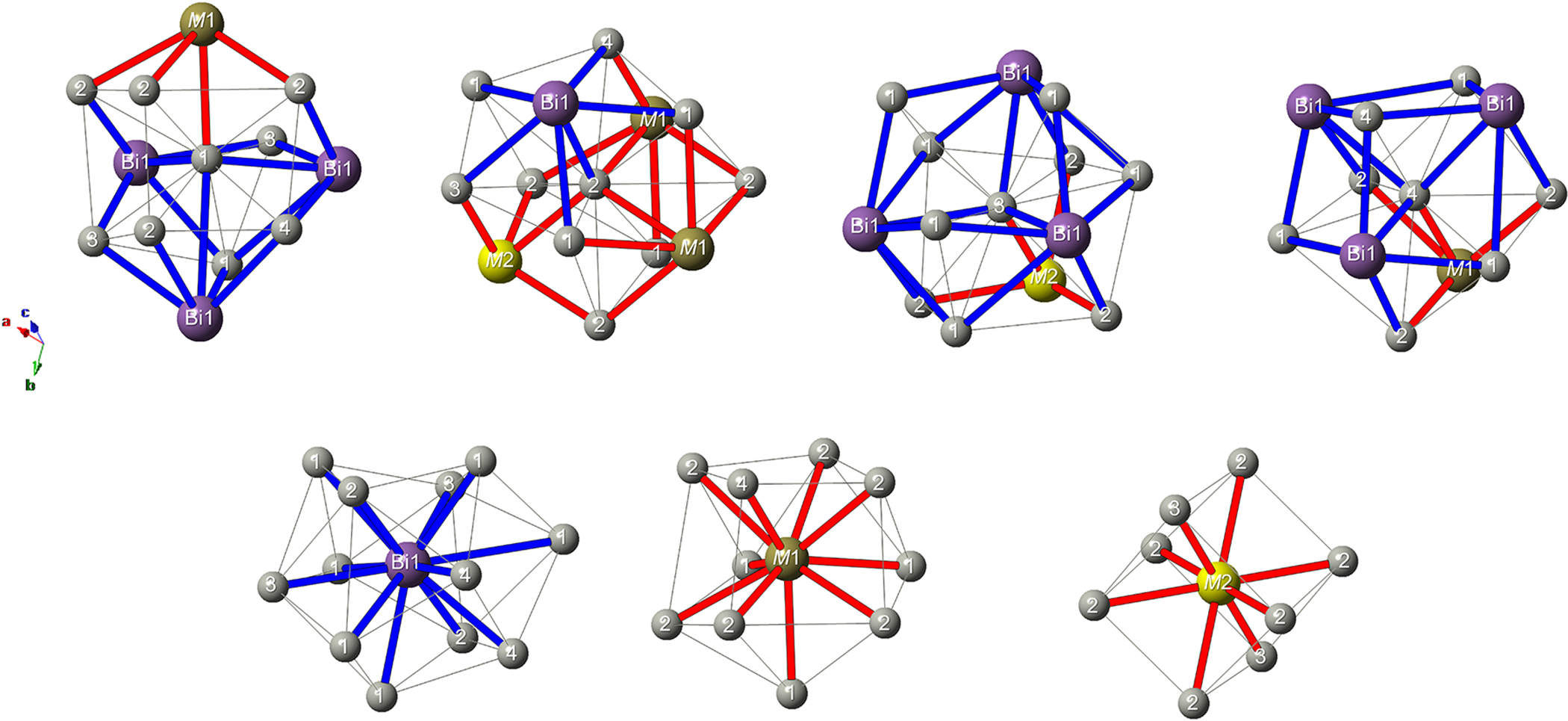

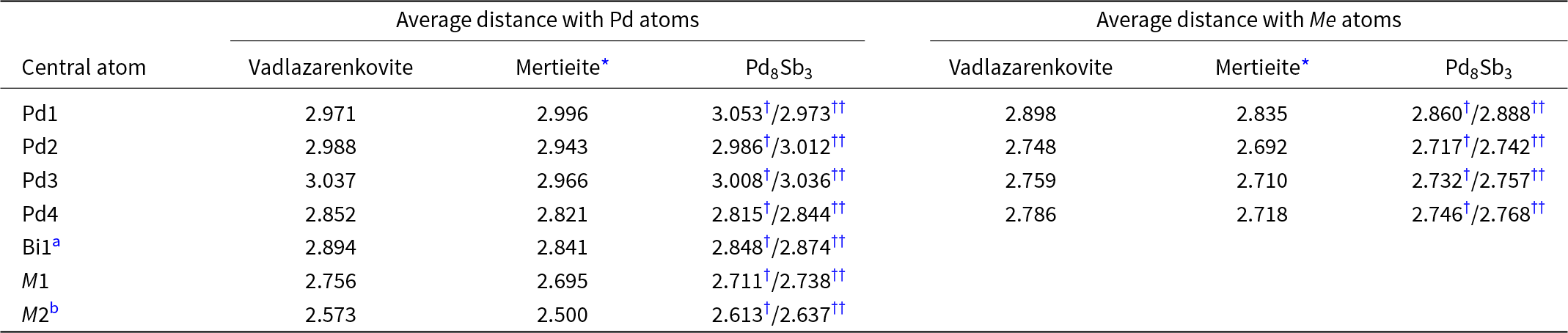

The crystal structure of vadlazarenkovite (Fig. 5) has four symmetry-independent Pd sites at 36f (Pd1 and Pd2) and 12c (Pd3 and Pd4) positions. Atom coordinations are shown in Fig. 6. Palladium atoms at Pd1 are coordinated to 8 Pd atoms, with distances ranging between 2.85 and 3.18 Å, and to four (Bi/Te)-bearing sites. At the Pd2 site, Pd atoms are coordinated by nine Pd atoms (in the interatomic distance range of 2.87–3.21 Å) and four (Bi/Te/As)-hosting sites. Pd3 and Pd4 have 13 and 11 neighbours, respectively. The former is characterised by nine Pd–Pd contacts shorter than 3.20 Å and four Pd–(Bi/Te/As) distances, whereas the latter displays seven Pd–Pd interatomic distances shorter than 3 Å and four (Bi/Te) contacts. Table 7 reports a comparison between coordination numbers and average values of Pd–Pd and Pd–Me (Me = As, Bi, Sb and Te) distances in vadlazarenkovite, mertieite (Karimova et al., Reference Karimova, Zolotarev, Evstigneeva and Johanson2018) and synthetic Pd8Sb3 (Wopersnow and Schubert, Reference Wopersnow and Schubert1976; Marsh, Reference Marsh1994). It is worth noting that Pd–Me distances are larger than those observed in mertieite; this is in keeping with the replacement of Sb and As by larger Bi atoms. At the four Pd sites, no evidence for the occurrence of other elements other than Pd was observed during the crystal structure refinement. However, the possible occurrence of minor Ag cannot be discarded.

Figure 5. Unit-cell content of vadlazarenkovite as seen down b. Symbols: Pd sites are shown as grey circles, the Bi1 site is represented by violet circles, and M1 and M2 sites are light brown and yellow circles, respectively. Pd–Bi and Pd–Te are shown as thick blue and red lines, respectively, whereas Pd–Pd contacts are shown as thin black/grey lines. Drawn using CrystalMaker® software.

Figure 6. Coordination environments of atom sites in vadlazarenkovite. Same symbols as in Figure 5.

Table 7. Comparison between average values of Pd–Pd and Pd–Me interatomic distances (in Å) in vadlazarenkovite, mertieite, and synthetic Pd8Sb3.

* Data after crystal I of Karimova et al. (Reference Karimova, Zolotarev, Evstigneeva and Johanson2018);

† Data after Wopersnow and Schubert (Reference Wopersnow and Schubert1976);

†† Data after Marsh (Reference Marsh1994).

a Sb1 in the crystal structure of mertieite (Karimova et al., Reference Karimova, Zolotarev, Evstigneeva and Johanson2018);

b As1 in the crystal structure of mertieite (Karimova et al., Reference Karimova, Zolotarev, Evstigneeva and Johanson2018).

The Bi1 site (Wyckoff position 18e) has coordination number 12; the mean atomic number (m.a.n.) at this position is 74.66 electrons, indicating the partial replacement of Bi by lighter atoms (probably Te and minor Sb). In mertieite, this site was fully occupied by Sb (Karimova et al., Reference Karimova, Zolotarev, Evstigneeva and Johanson2018). The M1 site (at the 12c position) is ten-fold coordinated by Pd atoms, and its refined m.a.n. is 66.38 electrons, thus indicating the possible mixed Bi/Te occupancy of this site. In mertieite, this 12c position was occupied by Sb, with minor As (Sb0.94As0.06 in crystal I and Sb0.88As0.12 in crystal II). Finally, the M2 site, at the position 6b, is eight-fold coordinated by Pd atoms and its refined mean atomic number (m.a.n. = 43.20 electrons) agrees with a mixed Te/As site. Taking into account the site multiplicity, the refined site scattering at the Bi1, M1 and M2 sites is 199.97 electrons per formula unit (Z = 12). This value has to be compared with the results of electron microprobe analysis, i.e., Pd7.87(5)Ag0.27(1)Bi1.26(20)Te1.16(18)As0.22(3)Pb0.16(2)Sb0.06(1). Assuming that minor Ag replaces Pd at the Pd sites, the site population at the Bi1+M1+M2 sites would be Bi1.26Te1.16As0.22Pb0.16Ag0.14Sb0.06, corresponding to 194.92 electrons.

A difficult task is represented by the actual description of the element partitioning among the Me-bearing sites. The largest Me atoms (i.e., Ag and Pb) could be attributed to the Bi1 site, along with Sb (in agreement with what’s observed in mertieite, where Sb is preferentially partitioned there with respect to M1 and As1 – Karimova et al., Reference Karimova, Zolotarev, Evstigneeva and Johanson2018). Consequently, Bi1 could have an idealised site population (considering the site multiplicity and the refined m.a.n.) close to Bi0.90Te0.25Pb0.15Ag0.15Sb0.05.

The M1 site could be considered as a mixed Bi/Te site. The refined m.a.n. agrees with Te0.55Bi0.45. However, also considering the chemical data, a Te/Bi atomic ratio close to 1.5 seems to be reasonable, i.e., Te0.60Bi0.40.

Finally, the M2 site is a mixed Te/As site. Refined m.a.n. and electron microprobe data allow us to suggest the population Te0.25As0.25.

The proposed structural formula of vadlazarenkovite is Pd1–Pd4Pd8Bi1Bi1.5M 1Te1.00M 2(Te0.25As0.25), i.e., Pd8Bi1.5Te1.25As0.25 (Z = 12).

Discussion

Crystal chemical features

Vadlazarenkovite, Pd8Bi1.5Te1.25As0.25, is isotypic with mertieite, Pd8Sb2.5As0.5 (Karimova et al., Reference Karimova, Zolotarev, Evstigneeva and Johanson2018; Miyawaki et al., Reference Miyawaki, Hatert, Pasero and Mills2022). For a comparison of the two species see Table 8. Synthetic Pd8Bi3 was reported by Sarah and Schubert (Reference Sarah and Schubert1979), with unit-cell parameters a = 7.81 and c = 42.60 Å and space group R3.

Table 8. Comparative data for vadlazarenkovite and mertieite.

† R max/R min for vadlazarenkovite, Rʹ for mertieite

As shown in Table 2, vadlazarenkovite has a relatively large range of Te and Bi contents. In agreement with the result of crystal structure analysis we assumed the following substitutions:

(1) Pd is replaced by minor Ag at Pd1–Pd4 sites;

(2) Bi is replaced by minor Pb, Ag, Sb, and possibly Te at the Bi1 site;

(3) Te is replaced by Bi at the M1 site;

(4) Te and As occur at the M2 site.

Following these substitution rules, the following chemical formulae for the six spot analyses can be written as:

(1) (Pd7.83Ag0.17)(Bi1.12Pb0.14Ag0.10Sb0.07Te0.06)(Te1.00)(Te0.27As0.23);

(2) (Pd7.88Ag0.12)(Bi1.11Pb0.17Ag0.16Sb0.06)(Te0.74Bi0.26)(Te0.26As0.24);

(3) (Pd7.91Ag0.09)(Bi1.10Pb0.16Ag0.17Sb0.06)(Te0.93Bi0.07)(Te0.27As0.23);

(4) (Pd7.91Ag0.09)(Bi1.11Pb0.17Ag0.15Sb0.06)(Te0.86Bi0.14)(Te0.28As0.22);

(5) (Pd7.78Ag0.22)(Bi1.17Pb0.19Ag0.07Sb0.07)(Te0.59Bi0.41)(Te0.34As0.16);

(6) (Pd7.87Ag0.13)(Bi1.05Pb0.14Ag0.15Sb0.06Te0.10)Te1.00(Te0.26As0.24).

In all cases, Bi is dominant at Bi1 and Te at M1, whereas the M2 site population is close to Te0.25As0.25. This latter mixed (Te/As) occupancy, with a Te/As atomic ratio close to one, may be due to geochemical constraints or may indicate a possible role of the (Te0.5As0.5) double-site occupancy in the stabilisation of vadlazarenkovite.

Geochemical features

The platinum-group mineral assemblage found at the Anomal’noe occurrence is characteristic of copper sulfide (chalcopyrite, chalcopyrite–bornite and bornite) ores, hosted by gabbroic rocks of the Ural-Alaskan type, which are found both in fold belts and cratons. The first include gabbro massifs of the Northern Urals (Stepanov et al., Reference Stepanov, Palamarchuk, Antonov, Kozlov, Varlamov, Khanin and Zolotarev2020; Mikhailov et al., Reference Mikhailov, Stepanov, Kozlov, Petrov, Palamarchuk, Shilovskikh and Abramova2021), Koryak Highlands (Kutyrev et al., Reference Kutyrev, Sidorov, Kamenetsky, Chubarov, Chayka and Abersteiner2021; Palyanova et al., Reference Palyanova, Kutyrev, Beliaeva, Shilovskikh, Zhegunov, Zhitova and Seryotkin2023) and Alaska (Milidragovic et al., Reference Milidragovic, Nixon, Scoates, Nott and Spence2021). The second are represented by Inagli and Gulinskiy massifs (Sazonov et al., Reference Sazonov, Romanovsky, Gertner, Zvyagina, Krasnova, Grinev and Kolmakov2021; Chayka et al., Reference Chayka, Kamenetsky, Malitch, Vasil’ev, Zelenski, Abersteiner and Kuzmin2023) and Konder described in this paper.

An important feature of the copper-PGE mineralisation at Anomal’noe is the wide occurrence of PGE-bearing minerals containing Bi, Te and Pb. One of these is vadlazarenkovite that contains Bi and Te as species-defining elements and Pb as a minor constituent. The absence of Bi, Te and Pb in PGE-bearing minerals or their extreme rarity in rocks and ores of the zoned complexes of the fold belts can be explained by the fact that the latter were formed from magmas of the young ensimatic arc settings (Cai et al., Reference Cai, Sun, Yuan, Zhao, Xiao and Long2012; Habtoor et al., Reference Habtoor, Ahmed and Harbi2016), where the content of Bi, Te and Pb in the geochemical systems is at a very low level. By contrast, formation of the Ural–Alaskan type complexes in cratons was probably accompanied by crustal assimilation that contributes typical crust-derived elements to the magmas. Although the contamination and, hence, enrichment of the magmas by these elements might be minor, it could be still enough to form such a unique PGE-bearing minerals assemblage.

Furthermore, for the case of the Anomal’noe occurrence, the role of the alkali-rich late magmatic fluids, which emerged from the later stage Ketkap alkaline complex should be significant. Enriched with phosphorus and fluorine, these fluids could re-deposit and concentrate ore metals (Gurevich, Reference Gurevich, Gurevich and A.A2023) and produce the mineralisation studied. Therefore, we suggest that the unique mineral assemblage investigated here, including vadlazarenkovite, was a result of the following superimposed factors: (1) contamination of mantle-derived rocks by crustal components; and (2) several stages of concentration of the metals with the aid of alkaline fluids derived from the subsequent magmatic pulse.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1180/mgm.2024.52.

Acknowledgements

We thank Associate Editor Owen Missen, František Laufek and two anonymous Reviewers for constructive comments that improved the manuscript. Ivan F. Chayka is acknowledged for the discussion on geological features and Maria D. Milshina – for the help with the figures. The PXRD studies were performed at the Research Centre for X-ray Diffraction Studies of St. Petersburg State University within the framework of project AAAA-A19-119091190094-6.

Competing interests

The authors declare none.