Introduction

This article explores the importance of a neglected, and ostensibly insignificant, site of world politics: The Gruffalo Footnote 1 – a spectacularly successful children’s picturebook with tens of millions of sales across dozens of languages. Taking up Kyle Grayson, Matt Davies, and Simon Philpott’s call to ‘view the signifying … practices of popular culture as “texts” that can be understood as political and as sites where politics takes place’,Footnote 2 we argue that The Gruffalo’s significance is in its vivid visual and narrative demonstration of the world’s susceptibility to plausible, yet seemingly incompatible, readings. Complicit in, and critical of, conventional understandings of the international, the book reproduces the world’s familiar storying as a site of insecurity and fearFootnote 3 while simultaneously interrogating that storying, its assumptions, and occlusions.Footnote 4 In so doing, it merits careful attention as a ‘theoretically informed diagnosis’Footnote 5 of the ontological and epistemological manoeuvres central to hegemonic understandings of world politics. Reflecting on this, moreover, highlights the capacity of childrens’ picturebooks to ‘reveal the approaches, interpretations and assumptions that underpin understandings of politics and what we believe to be political’,Footnote 6 while pulling attention to the contingent and unstable nature of world politics and popular culture.

To develop this claim, we proceed through an analysis of The Gruffalo as a polysemous text that may be read ‘in multiple different ways’.Footnote 7 Specifically, we show, first, that the book offers a persuasive theorisation of the characteristically realist state of nature as a pessimistic, anarchical world populated by self-interested, survival-seekers. Second, that it simultaneously disrupts this reading through creative engagement with the social production of threats. And third, that the parochial privileging of its protagonist’s journey through the wood within the text’s visual and narrative construction also offers occasion for a more fundamental, decolonial, counter-reading of global politics.Footnote 8 Our aim here is not to impose order on what we see as complex, partial, and contestable understandings of world politics. Rather, to acknowledge, as Christina Rowley and Jutta Weldes remind us: ‘that the world is messy and cannot easily or unproblematically be parsed for analysis – that we lose as much as, if not more than, we gain through employing rigid categorizations, abstractions and generalizations.’Footnote 9 The Gruffalo helps in this precisely because it ‘presents a compelling argument’Footnote 10 about the indeterminacy of world politics through exposing the limitations of materialist ontologies and their inevitabilities. And, because its organisation around the journey of one ‘aesthetic character’Footnote 11 – mouse – offers an elegant, yet sophisticated, illumination of the partiality of knowledge about global political life.Footnote 12

In making this argument, the article offers three contributions to knowledge. First, it extends contemporary research on popular culture and world politics through original engagement with a spectacularly successful, yet almost entirely neglected, artefact – The Gruffalo – and genre – the children’s picturebook. Despite the proliferation of compelling work on the importance of film, videogames, comics and the like, picturebooks aimed at young readers remain conspicuous by their absence in IR,Footnote 13 a corollary, in part, of a broader neglect of children within theorisations of global politics.Footnote 14 Taking picturebooks seriously, therefore, contributes to recent efforts to open IR to historically excluded texts, authors, and fields,Footnote 15 providing opportunity for new connection with disciplines such as children’s literature studies.Footnote 16

Second, our article offers the first effort to engage with picturebooks such as The Gruffalo as important examples of ‘vernacular theorisation’Footnote 17 that simultaneously and creatively (re)produce and (de)stabilise (knowledge of) global politics in undetermined ways.Footnote 18 Vernacular theorisation, here, is understood as the ‘ability to relate complex issues to the everyday, and to scrutinise and interrogate significant social processes in a critical fashion’,Footnote 19 opening up ‘new ways of seeing’ the world and its understanding.Footnote 20 Our claim is not, to be clear, that picturebooks serve as allegories or metaphors for world politics.Footnote 21 Nor is it that The Gruffalo, specifically, possesses or advances ‘a’ pre-existing theory of world politics. Rather, that theorising is something that takes place through The Gruffalo’s visual and linguistic content and form,Footnote 22 and its invocation and interrogation of seemingly axiomatic understandings of world politics.Footnote 23 This approach to theory – as an everyday practice rather than nounFootnote 24 – means we make no claim on the book’s reception or causal impact on readers, many of whom may lack explicit awareness of international relations/International Relations.Footnote 25

The article’s third contribution is to offer a composite methodological framework for future interrogation of the context, content, and framing of picturebooks such as The Gruffalo in order to facilitate subsequent work in this vein. This framework draws on a range of relevant scholarship within and beyond the pop culture and world politics literature to guide academic engagement with issues of authorship, reception, narrative, plot, visual illustration, and framing. Our claim to originality, here, therefore, is one of ‘conceptual combination’ that involves novel juxtaposition of methodological tools and insights from existing work on related, but distinct, sources of popular culture.Footnote 26

The article begins by situating our analysis within two growing literatures: on children and world politics, and on popular culture and world politics. The former, we argue, offers an important but neglected challenge to ontological, epistemological, and methodological orthodoxies within International Relations. The latter offers vital theoretical resources for exploring the value of children’s picturebooks as sources for exposing the foundations, assumptions, exclusions, and tensions of familiar renderings of world politics. Particularly useful here is Michael J. Shapiro’s notion of the ‘aesthetic subject’ with its emphasis on the actions of fictional characters as an inroad to theorising political realities and their structuration.Footnote 27 The article then develops our four-part methodological framework that involves: (1) situating texts in their historical and sociopolitical contexts;Footnote 28 (2) rich description of narrative construction and emplotment;Footnote 29 (3) visual analysis of a book’s graphic presentation;Footnote 30 and, (4) analysis of the vernacular theoretical work done by the text, which in this case involves reading the Gruffalo plurally as invocation and negotiation of the anarchy problematic that structures dominant constructions of the international, and as a provocation towards a more radical decolonial critique of the (re)production of global politics (knowledge). In the article’s conclusion, finally, we explore opportunities for further research on popular culture, world politics, and children’s fiction.

Children, culture, and world politics

We begin by situating our discussion in two recent and vibrant literatures: on children and IR, and on popular culture and world politics. This helps to locate the article’s contribution, and demonstrates the potential importance of relatively neglected texts such as The Gruffalo. The section begins by arguing that while much IR literature denies children meaningful agency in world politics, important recent work has begun to emerge on the capacity of children and their books to problematise and disturb common-sense understandings of the world.Footnote 31 A second section then migrates this claim to a wider literature on popular culture’s theoretical capacity to produce and rupture knowledge of the world through its question-raising sensibilities.

Children and IR

Despite their importance within global politics, children are still largely absent in the field of IR: Footnote 32 ‘It is as yet still rare to find them positioned in IR’s stories about itself and its subject matters as complex and consequential actors in and of the social worlds they occupy.’Footnote 33 Where children do appear, their roles are often limited to subjects lacking in agency such as child soldiers,Footnote 34 victims of humanitarian catastrophe,Footnote 35 or individuals vulnerable to violent media or military recruitment.Footnote 36 Recent work, however, has begun to challenge this neglect, from scholarship on the agency of children – for instance as witnesses of atrocities,Footnote 37 to reflection on the capacity of young people to revitalise political debate including via activism.Footnote 38 Although much remains to be done, such work highlights the importance of children’s actions and agency in global politics, demonstrating that young people have important capacity for storying, questioning, and critiquing the world, including via complex and critical readings of sociopolitical life. Crucially, this work suggests that young children (in particular) often embody curiosity through the asking of questions and telling of stories that may actively problematise taken-for-granted hierarchies and issues.Footnote 39

There is much that IR scholarship could learn here from the field of children’s literature studies, childhood studies, and the sociology of childhood. Hannah Field, for example, exploring Victorian picturebooks, compellingly demonstrates the agency of children (as conventional readers but also as playful disruptors who might chew or colour books) while considering the content of such books both representationally and in material form.Footnote 40 Our suggestion here – evidenced through our reading of The Gruffalo – is that children’s picturebooks contribute to this appetite for questioning and problematisation, such that these books can be approached methodologically as vernacular theorisations of world politics: as accessible yet sophisticated texts that unpack and disrupt existing frameworks of knowledge.Footnote 41 In this vein, Starnes uses fairy tales as both method and methodology to expose the taken-for-granted assumptions underpinning sixty IR textbooks.Footnote 42 Relatedly, J. Jack Halberstam, drawing on SpongeBob SquarePants, argues that children’s popular culture is especially susceptible to non-hegemonic or subversive readings, in part because children are less imprinted by socialised expectations and more likely to engage in fantasy and play.Footnote 43

As fields beyond IR demonstrate, in short, there is therefore real value to engaging with such texts, their contexts and potentialities, and thereby moving beyond ‘misguided and sentimental notion[s] of childhood innocence … or naive investment in the idea of truth issuing from the mouths of babes’.Footnote 44

Popular culture and world politics

A second crucial recent development in IR has been a growing acknowledgement that popular culture matters in myriad ways for world politics.Footnote 45 Weldes and Rowley identify five (non-exhaustive) relationships between the two phenomena: ‘state uses of popular culture’ (e.g., state generated propaganda such as pro-war posters and films); ‘the global political economy and/of popular culture’ (e.g., the circulation, distribution, licencing, and consumption of the Harry Potter franchise); ‘global flows are cultural and political’ (e.g., the way in which food morphs, flows, and is absorbed and/or rejected in different contexts); ‘representations, texts and intertexts’ (e.g., how different cultural and racial groups are represented in films and videogames), and ‘the politics of cultural consumption and cultural practices’ (e.g., how audiences understand meaning within popular culture).Footnote 46 As Weldes had earlier argued, it is unrealistic for a researcher to cover all of these themes – in part ‘for reasons of space’ – but also due to variation in research questions, methodological frameworks, and metatheoretical assumptions.Footnote 47

Perhaps the most pronounced thread within this literature is a pedagogical one centred on the value of popular culture for aiding understanding of emerging trends in world politics and theorisations thereof.Footnote 48 Marco Fey, Annika E. Poppe, and Carsten Rauch, for example, employ a detailed reading of Battlestar Galactica (2004–09) to demonstrate depictions of nuclear weapons within this long-running television series.Footnote 49 As they show, Battlestar Galactica’s portrayal of rational actors routinely employing nuclear weapons not only problematises the ‘nuclear taboo’. It also aids theoretical understanding by demonstrating evolving trends in ‘real’ world politics such as the taboo’s weakening through powerful states’ talk of ‘smart weapons’ and ‘collateral damage’.

Related work concentrates less on the pedagogical potential of such texts, and more on the importance of popular culture artefacts as provocations to theoretical insight, including through disturbance of established conceptual frameworks.Footnote 50 Cynthia Weber’s landmark textbook, for instance, reads a number of films to challenge assumptions (or ‘myths’) inherent to key IR texts.Footnote 51 Rowley and Weldes read Buffy the Vampire Slayer and Angel to problematise assumptions beneath the ‘myth of the evolution of (international) security studies’,Footnote 52 and Matt Davies reads the former series as offering ‘a particular and explicit argument about work, about the importance of the quality of work, and about the place work plays in the processes of human development and self-realization’.Footnote 53 This use of popular culture to draw attention to omissions and exclusions within IR theoryFootnote 54 is evident, too, in Davies and Amanda Chisholm’s exploration of Dollhouse’s interrogation of the sexual violence underpinning neoliberal subjectivity,Footnote 55 and in Julia Welland’s use of novels to track war’s joyful experiences.Footnote 56 Popular culture, in work such as this, brings into focus that which is obscuredFootnote 57 in dominant understandings, directing attention to hitherto neglected or occluded phenomena, practices, experiences, and the like.

This use of popular culture to rupture established ways of thinking connects to ‘the aesthetic turn’ in world politics with its emphasis on the inseparability of methods and knowledge.Footnote 58 Shapiro, for instance, draws extensively on popular culture to argue that ‘fictional characters’ within films and novels are as valuable for exploring the boundaries and contexts of world politics as the ‘real’ actors with whom IR researchers typically engage.Footnote 59 Drawing on Rancière, Shapiro introduces the notion of the ‘aesthetic subject’ to focus attention on how the permitted and proscribed movements within artistic genres,Footnote 60 can ‘disrupt the taken-for-granted, invisible, and common-sense premises that inscribe the boundaries around the assumed limits to perceptual or political possibilities’.Footnote 61 By centring how characters traverse a text’s narrative and visual arc,Footnote 62 engaging with the aesthetic subject means eschewing reflection on the internal desires and motivations of actors. As Shapiro argues, this is precisely because fictional characters’ ‘movements and dispositions are less significant in terms of what is revealed about their inner lives than what they tell us about the world to which they belong’,Footnote 63 not least where their ‘movements and actions (both purposive and non-purposive) map and often alter experiential, politically relevant terrains’.Footnote 64 By moving away from the ‘motivational forces of individuals’,Footnote 65 such readings help render visible power-relations and sociocultural dynamics inherent to everyday, and multiple, experiences of spaces of residence, labour, worship, transit, care, leisure, and beyond.Footnote 66 They do so, in part, by facilitating analysis of the rules that enable and constrain the actions of specific, but diverse, characters or subjects.

Work such as the above demonstrates the constitutive and critical importance of popular culture for international politics. Not only does it document the world-making potential of cultural genres and their capacity to (re)produce the world in specific ways. It also offers resources for engaging popular culture’s potential to expose, excavate, and problematise the foundations of established ways of seeing, feeling, and knowing global politics and its interfaces.Footnote 67 As this literature makes clear, there are real advantages to using popular culture to such ends. Films, videogames, or – in our case, picturebooks – can be arresting, can access hard to reach groups, and can provoke understanding and action through individual and collective experiences: cognitive and affective.Footnote 68 For readers already familiar with specific artefacts, popular culture can also be illustrative and informative.Footnote 69 At the same time, there are important caveats to guard against an uncritical dash to popular culture for theorising and critiquing world politics and knowledge thereof.

First, in using popular culture it is important to respect the long-standing contribution of PCWP scholars.Footnote 70 The very point of the above work is that popular culture merits serious scholarship, rather than relegation to the entertainingly illustrative.Footnote 71 Second, using popular culture to ‘simplify’ theory risks patronising readers as incapable of, or uninterested in, high-level understanding. Third, and relatedly, engaging with popular culture requires expertise and disciplinary training that researchers and readers may lack. Scholars of film, literature, videogames, and theatre, for instance, all engage with artefacts within ‘expert disciplines’, and proper reflection is needed on the methodological incorporation, adaptation, and innovation required for the treatment of such texts in IR.Footnote 72 Finally, working through popular culture is also time-consuming. While extracts are often used, commonly discussed artefacts – for instance, Star Trek and Game of Thrones – often run to hundreds of hours of material. Engagement therewith for the purposes of illustration or simplification may therefore be more laborious than reading original theoretical material!

In our analysis of children’s picturebooks as a site for theorising and problematising global politics, we guard against these concerns in several ways. First, we develop insight from established scholarship on diverse cultural genres to set out a new composite methodological framework for future readings of children’s picturebooks by IR researchers and students. Second, we situate our reading not as an adjunct or replacement for theory but precisely as an endeavour designed to locate and unsettle dominant understandings of global political dynamics by bringing forth frequently occluded assumptions.Footnote 73 Third, we embrace the complexity of picturebooks as a polysemous and unstable source of knowledge of world politics. Given the lack of prior engagement with such texts by IR scholars we hope here also to create openings for dialogue with adjacent fields which may be productive in future critical readings of other genres and artefacts.

The Gruffalo and world politics

In the remainder of the article, we now combine and build on insights from related scholarship to offer a new methodological framework for investigating picturebooks, using The Gruffalo as a worked example.Footnote 74 The framework is one, we hope, with utility for subsequent research on artefacts such as this, and proceeds via four steps, the relative importance of which will vary according to one's research question(s), text, and contexts. First, we situate The Gruffalo contextually, highlighting its prominence and reach as a vernacular theorisation of world politics. Through this, it is possible to reflect on the text’s social status,Footnote 75 to take note of its authority and importance, and to engage with statements of authorial intent. A second step provides a rich description of the text’s narrative, tracing the plot’s construction across five stages:Footnote 76 exposition, rising action, climax, falling action, dénouement. This leads to a visual discourse analysis of the book, pulling attention to issues including illustrative style, graphic presentation, framing, and placement. These two sections enable us – as Lene Hansen puts it – to consider how children’s picturebooks serve ‘as objects that speak about the world’.Footnote 77 The final – and most expansive – step then explores how The Gruffalo itself offers a multiple, and ultimately critical, theorisation of the international. Here, we demonstrate how the book confronts readers with the world’s susceptibility to radically different readings, through showing how it: (1) posits the international as an anarchical environment of security-seeking behaviour by unconstrained self-interested actors; (2) develops an argument about the contingent nature of global political outcomes by emphasising the constitutive and causal power of ideas; and, (3) serves as a provocation to a more fundamental, decolonial, critique of the politics of security (knowledge) through its narrative and visual structuring around the journey of one aesthetic character: mouse.

Situating The Gruffalo

First published in 1999 in the UK by Macmillan Children’s Books, The Gruffalo has been a phenomenal commercial and critical success. Winner of the prestigious Nestle Smarties Prize, a 2009 poll of BBC Radio 2 listeners identified the book as the best bedtime story for children.Footnote 78 Sales of The Gruffalo sediment its cultural importance, with 1.49 million copies of the original volume having been sold in the UK alone in the twenty years since publication.Footnote 79 The book’s global reach is indicated by its translation into over eighty languages;Footnote 80 its commercial success evident in the range of subsidiary merchandising from activity books to crockery and clothing.Footnote 81 The Gruffalo (and its popular sequel, The Gruffalo’s Child) has been adapted into animated films, while theatre productions, adventure walks, theme park rides, and concerts all contribute to the book’s public prominence in the UK and beyond.

Engagements such as these both point to and reproduce The Gruffalo’s importance as a contemporary cultural artefact. The book’s popularity is facilitated, in part, by its aesthetics as an illustrated novel offering a visual, simplified story of its world and its characters.Footnote 82 With the book’s intertextual origins commonly narrated through (unproblematised) reference to a ‘traditional Chinese tale’ featuring a young girl and a tiger,Footnote 83 Donaldson locates its success in the sublime: that stimulating, even exciting, sensation of terror experienced on encounter with the prospect of danger.Footnote 84 In her words: ‘All children like feeling scared and having that fear relieved. They feel empowered through that.’Footnote 85 This connects to her dissatisfaction with the moralism of much children’s literature,Footnote 86 describing the book, in one interview, as a product of wanting ‘to do something that was a bit more realistic about how life really is’.Footnote 87 Donaldson and the illustrator Axel Scheffler have a lengthy history of collaboration, and both enjoy significant public profiles with the former’s portrait hanging in London’s National Portrait Gallery. The pair have also engaged directly in ongoing political conversations, from Donaldson’s suggestion that the 2019 The Smeds and The Smoos could ‘very much be seen as a Remain book’,Footnote 88 to their collaboration on a series of cartoons explaining the COVID-19 crisis, including one of the Gruffalo and his child ‘stay[ing] in the Gruffalo cave’.Footnote 89

Although media such as picturebooks, graphic novels, and comics often suffer condescension,Footnote 90 we can already see The Gruffalo’s importance for the production, negotiation, and contestation of meaning about the world. On the one hand, the book’s continuing success demonstrates the ‘ongoing capital’ of children as consumers of popular culture,Footnote 91 and therefore their importance for the stories told of global politics. Moreover, in introducing its readers to new places, ideas, and dynamics, the book offers important insight into the construction and circulation of common sense, and the creation, perpetuation, and transformation of sociopolitical worlds.Footnote 92 As Peter Hunt argues, ‘most adults, and almost certainly the vast majority of those in positions of power and influence, read children’s books as children, and it is inconceivable that the ideologies permeating those books had no influence on their development.’Footnote 93 By communicating reality’s complexity in a simplified, yet focused, manner, The Gruffalo therefore has rich potential for spotlighting the assumptions and exclusions underpinning constructions of political reality,Footnote 94 and, in the process, for enabling a questioning of the world within and outwith its pages. To borrow from a recent article on Dr Seuss, The Gruffalo ‘provides a critical access point to the tremendous potential of literature to reveal significant commentary on our complex world’.Footnote 95 To demonstrate, the following sections now turn to the Gruffalo’s linguistic and visual storying of the world.

Storying The Gruffalo

An illustrated rhyming story of only seven hundred words,Footnote 96 The Gruffalo centres on a mouse’s journey – a ‘stroll’ – through a ‘deep dark wood’. Structurally,Footnote 97 the book begins with a two-part exposition: a two-page illustration of the ‘deep, dark wood’ in which the story is set, preceded by an invitation for readers to, ‘Walk further into the deep dark wood, and discover what happens when the quick-thinking mouse comes face to face with an owl, a snake, and a hungry Gruffalo …’. This dramatic opening efficiently introduces the book’s primary characters, their attributes, relations, and environment,Footnote 98 while establishing a mind/body dualism between its reasoning protagonist and the book’s more corporeal titular character.

The first half of the book provides the plot’s rising action in which the mouse sequentially encounters three of the wood’s carnivorous inhabitants: a fox, an owl, and a snake. Their intention to eat the protagonist is inferred from suggestions that mouse accompany them home for lunch, tea, and a feast, respectively. The mouse successfully rebuffs each invitation – evading the threat posed by the three creatures – by describing, or, rather, inventing, a prior commitment to dine with ‘a gruffalo’. Each predator’s ignorance of this seemingly fabricated creature is met with feigned surprise:

‘A gruffalo? What’s a gruffalo?’

‘A gruffalo! Why, didn’t you know?’

Answering their own question, mouse then describes three characteristics of a gruffalo to each interlocutor, gradually building – for readers – a composite picture of this creature. So, fox – and readers – are introduced to a gruffalo’s armoury – his tusks, claws, teeth, and jaws. Conversations with owl and snake are then dominated by the creature’s monstrosity, which includes knobbly knees, a poisonous wart, and purple prickles all over his back. Inset images graphically evidence this horror: his orange eyes are drawn menacingly narrowed; his black tongue dribbles revoltingly; his purple prickles are pointed; and his tusks and claws are both sizeable and sharp. Such depictions, accompanied by pointed references to a gruffalo’s ‘favourite foods’ of roasted fox, owl ice cream, and scrambled snake, are sufficient to deter mouse’s antagonists. And, as fox, owl, and snake flee, readers of the book share in mouse’s subterfuge as its protagonist gleefully monologues on their clever fabrication:

‘Silly old Fox! Doesn’t he know,

There’s no such thing as a gruffalo’

It is at the end of the third encounter (with snake) towards the book’s halfway point, that mouse finds their triumphalism interrupted: ‘There’s no such thing as a gruffal –’. Turning the page, readers encounter the book’s climax as mouse stumbles upon a creature matching the description of previous pages. As mouse revisits those characteristics – ‘But who is this creature with terrible claws, And terrible teeth …’ – it realises:

‘Oh help! Oh no!

It’s a gruffalo!’

The threat posed by this monstrous creature is swiftly confirmed as the Gruffalo – from here on a proper noun – corrects mouse’s earlier (fabricated) culinary claims:

‘My favourite food!’, the Gruffalo said.

‘You’ll taste good on a slice of bread!’

Mouse’s response to this threat, however, is swift and characterised by the self-composure of their earlier encounters. Feigning umbrage at the Gruffalo’s chosen predicate – ‘Good?’ said the mouse. ‘Don’t call me good!’ – mouse self-describes as ‘the scariest creature in this wood’, inviting the Gruffalo to witness this claim. A laughing Gruffalo agrees, following the mouse back down the woodland path.

The plot’s falling action then mirrors the opening pages as Gruffalo and mouse meet the three earlier inhabitants in reverse. Spotted by – and spotting – the Gruffalo, snake, owl, and fox quickly retreat from the monster of whom they were so recently ignorant. Readers of the book, of course, recognise it is fear of the Gruffalo that causes the predators to flee:

‘It’s Snake,’ said the mouse. ‘Why, Snake, hello’

Snake took one look at the Gruffalo.

‘Oh crumbs!’ he said, ‘Goodbye, little mouse,’

And off he slid to his logpile house.

The Gruffalo, though – stood behind mouse – interprets each retreat as confirmation of the latter’s earlier bold claim. Seeing the Gruffalo’s anxiety mounting with each encounter, mouse finally turns to the eponymous character, reversing the Gruffalo’s earlier threat:

‘Well, Gruffalo,’ said the mouse. ‘You see?

Everyone is afraid of me!

But now my tummy’s beginning to rumble.

My favourite food is – Gruffalo crumble!’

The threat is too much for the Gruffalo who turns and flees ‘quick as the wind’, leaving the mouse alone to enjoy a nut amidst the trees of the deep, dark wood in the plot’s dénouement.

Visualising The Gruffalo

As a children’s picturebook, The Gruffalo’s storying of the world takes place through visual presentation as much as narrative content, with Julia Donaldson’s written text interacting with Axel Scheffler’s illustrations. The ‘deep dark wood’ of the story’s setting is never explicitly situated, but the environment imagined by its UK-based creators would be a familiar one to readers there, populated by common native flora (white pine trees, birch trees, bullrushes) and fauna (kingfishers, damselflies, red squirrels, green woodpeckers). The naturalness of this bucolic backdrop of trees, grasses, flowers, and streams pictorially accentuates the Gruffalo’s monstrosity as a source of disruption to the wood’s orderliness. As, indeed, does the dramatic visualisation of mouse’s dislocatory experience on meeting the Gruffalo; the rodent’s smiling self-confidence replaced, temporarily, with a wide-mouthed shock that sees a literal sweeping of mouse off their feet.

The book’s illustrations are – to contemporary readers – unmistakably Scheffler’s:Footnote 99 its principal and supporting characters benefiting from characteristically anthropomorphic facial expressions conveying their shifting emotional states, so neatly encapsulated when the three initial predators transition from slyness through confusion to fear. A comicality helps soften the threat of mouse’s adversaries for young readers, too: from the wide-eyed simplicity of fox, owl, and snake, to the Gruffalo’s pear-shaped portliness, although early sketches included more fearsome renderings of this monster.Footnote 100 The book’s images are drawn from a third-person perspective offering distance to the reader, and the story is told in the past tense by an unnamed narrator through whom readers access the characters’ thoughts and (mis)understandings. The inter-character dialogue is politely formal, even quaint – ‘It’s frightfully nice of you, Owl’ – and stereotypically British with references to ‘tea’, ‘crumble’, and the mouse’s ‘tummy’.

The book’s overall presentation is relatively uncomplicated, employing a single font size and style augmented only by the italicised dialogue of speaking characters. The guttering between images is minimal, and no pictures speak independently of the written text beyond the opening double-page spread, which illustrates the wood as a still and unmanaged space marked by seemingly recent footprints. The book’s text and images are typically separated into demarcated spaces, although two key moments in the story see the written text placed atop a full double-page image. First, where mouse meets the Gruffalo at the book’s plot twist, and second, at the book’s conclusion in which mouse – having vanquished their enemies – enjoys a nut in newfound security. The book’s textual form is in rhyme, an unpopular mode with publishers at the time of publication.Footnote 101 And, as indicated above, the book progresses through a pattern of repeated phrasings including at the conclusion of each encounter: ‘A Gruffalo! Why, didn’t you know?’.

Taking the above sections together, we can see that the Gruffalo proceeds via a series of successive encounters between its protagonist – mouse – and a cast of other characters that take place against a familiar visual backdrop (at least to the point of the Gruffalo’s intrusion). In storying the world through extrapolation from a hypothetical state-of-nature the book makes use of a stylistic device instantly familiar to students and scholars of IR and (liberal) political theory. As indeed, does its structuring around a series of (visually arresting) dyadic encounters between two characters.Footnote 102 These interactions, importantly, are dictated by the mobility of the book’s primary character. It is mouse’s journey through the wood that organises the book’s narrative and visual construction, their presence on every page combining with the plot’s emphasis on their movement. Although we return to this centring below, it matters, because, as Grayson notes, ‘How aesthetic subjects navigate their fictional terrains and the forms of encounter they experience are an important source of geopolitical knowledge in their own right that need not be reduced to allegorical symmetries between real and imagined geopolitical worlds.’Footnote 103

Theorising (through) The Gruffalo

In this section we now develop our reading of The Gruffalo as a polysemous theorisation of global politics. We begin by showing the book’s storying of the international as a pessimistic, anarchical world populated by self-interested, survival-seekers. From here, we reflect on its destabilisation of this reading through depiction of the social production of threats, and thereby the ideational and relational nature of power. We finish by showing how the book also advances a more fundamental, decolonial, critique of the politics of security (knowledge) that problematises the epistemological and normative privileging of its protagonist’s movement and experiences. Taken together, these readings vividly illustrate that neither world politics nor popular culture are ‘static structural givens’:Footnote 104 the book reflects, pulls attention to, and critically interrogates, the ontological and epistemological confidence of dominant understandings of the international.Footnote 105 The text’s amenability to these hegemonic, negotiated, and oppositional readings,Footnote 106 is a product, we argue, of its narrative and visual construction explored above, and of the openness to curiosity and rupture characteristic of children’s literature discussed at the article’s outset.

The Gruffalo’s portrayal of mouse’s encounter with four predatory carnivores may be read, simply, as a readily identifiable allegory of a characteristically realist anarchical world in which life is nasty, brutish, and short. In place of an imaginary state of nature we have here a literal one: a ‘deep, dark wood’ populated by fallen trees and heterogeneous fauna. The only (implicit) evidence of human existence is a path running through the wood and a logpile inhabited by snake, and – as in the constructed states of nature of European political theorists and their IR interlocuters – the wood appears to lack any framework of law or government.Footnote 107

In such a straightforward allegorical reading of the book, we encounter a world in which the relations between social actors are unmediated by any genuine (political) authority. No character is obliged, in this story, to submit to the will of another: ‘None is entitled to command; none is required to obey.’Footnote 108 And, although non-compliance with the solicitations of materially powerful actors – such as when mouse rejects the dinner invitations of fox, owl, and snake – is not subsequently substantiated via coercive power, the threat thereof remains a possibility.Footnote 109 Indeed, as we have seen, the story’s emplotment through a series of simplified, dyadic encounters is illustrative of what Daniel Deudney identifies as the ‘overwhelming consensus’ of state-of-nature theorists, namely, ‘that anarchical situations combined with actors who are in a situation of intense violence interdependence are intrinsically perilous for security’.Footnote 110

Developing this first reading, the primary characters populating The Gruffalo’s pages also bear considerable resemblance to the anthropomorphised states of realist (and other ‘mainstream’) theorisations of global politics:Footnote 111 a series of pre-given, unitary actors whose interactions are surface-level rather than constitutive.Footnote 112 From the book’s opening pages, the attention of readers is concentrated, moreover, on the great powers of the ‘deep, dark wood’: fox, owl, snake, the Gruffalo, and (perhaps) mouse.Footnote 113 Although a supporting cast of actors is identifiable in Scheffler’s visualisation (insects, small mammals, amphibians), their presence troubles neither the attention of our primary characters nor the book’s written text. Those characters not negligible to the unfolding narrative,Footnote 114 though, possess autonomy and formal equality in the absence of an overarching hegemon.Footnote 115 They are characterised, too, as functionally equivalentFootnote 116 in the sense that their interests – if not their ability to satisfy those interests – are effectively identical: centred on survival through eating and avoiding being eaten.

This emphasis on survival-seeking, self-interested behaviour is, of course, fundamental to dominant understandings of global politics.Footnote 117 As Darel Paul (critically) argues: ‘Both neorealism and neoliberalism are grounded in the assumption that the core interest of all states is self-preservation, and it is this desire to survive which acts as the fundamental animating principle of the state.’Footnote 118 Although The Gruffalo comprises a cast of heterogeneous capabilities and appetites (juxtaposing the nut-eating mouse to their carnivorous others), those ‘greater or lesser capabilities’Footnote 119 are put only to the service of survival through successful predation or escape thereof. The Gruffalo’s state of nature, here, visually captures Thomas Hobbes’s state of scarcity, hunger and covetousness; its cast little more than ‘machines moved by the desire for self-preservation’,Footnote 120 and condemned to perpetual insecurity:

It is manifest that during the time that men live without a common power to keep them in awe, they are in that condition which is called war; and such a war as is of every man against every man.Footnote 121

As a realist reading of the book might anticipate, the pursuit – and satisfaction – of survival in our anarchical deep dark wood is achieved through individual capabilities. No recourse is made to the morality of predation, either by predator or prey: the book’s ‘dangerous ontology’Footnote 122 generates a world of self-help, indeed self-reliance.Footnote 123 Those capabilities are material – teeth, beaks, claws, jaws, and so forth – but also (as discussed further below) ideational, as with mouse’s inventive engagement with their would-be attackers.Footnote 124 Mouse's ability to triumph over those foes thus seems to confirm the classical realist assumption of approximate natural equality, even if the difference in faculties between the characters appears more pronounced than assumed in Hobbes’s hypothetical construct:

Nature hath made men so equal, in the faculties of the body, and mind; as that though there be found one man sometimes manifestly stronger in body, or of quicker mind than another; yet when all is reckoned together, the difference between man, and man, is not so considerable, as that one man can thereupon claim to himself any benefit, to which another may not pretend, as well as he.Footnote 125

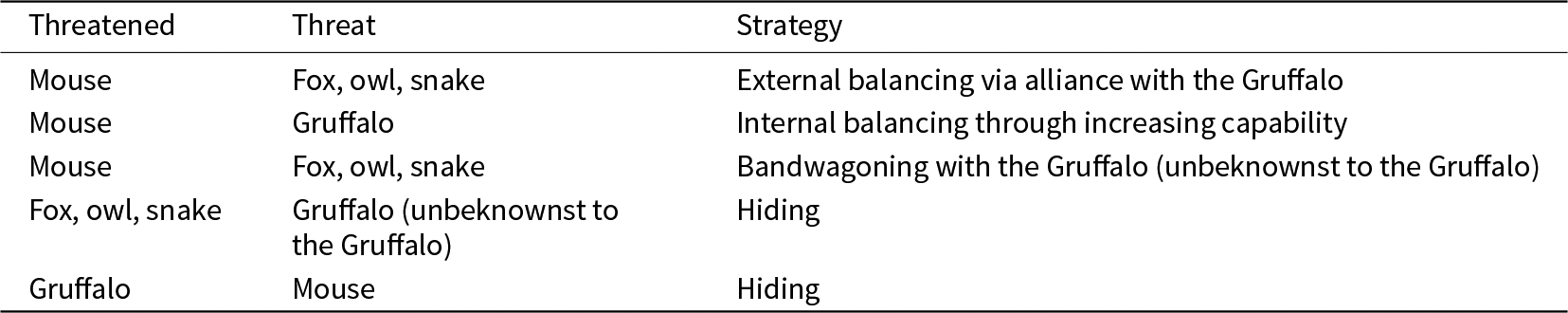

The Gruffalo’s susceptibility to a realist reading of International Relations, however, does not conclude with its portrayal of global politics’ setting and cast. Indeed, by looking at the resolution to its various dyadic encounters, the book also offers insight into potential strategies for escape from the security dilemma generated by its ontology (Table 1).

Table 1. Escaping the dark, dark wood’s security dilemma.

Two characteristics immediately emerge from these encounters. First, is the diversity of strategies available to survival-seekers. Second, is the successful avoidance of conflict that follows each. Indeed, contra the ‘eat or be eaten’ mantra of realisms’ offensive incarnations, the book’s characters typically act cautiously: eschewing risk of death through avoiding conflict with ostensibly superior foes.

In the opening three encounters, we see mouse externally balancing the threat posed by fox, owl and snake through allying with the (fabricated) Gruffalo. This new coalition with a materially powerful Gruffalo forces each provocateur into speedy retreat. Mouse’s encounter with the Gruffalo, in contrast, sees a successful attempt at internal balancing via the former’s demonstration of their (ostensibly superior) capabilities; capabilities seemingly subsequently evidenced on the shared return through the wood. This journey then witnesses mouse’s bandwagoning with the more powerful Gruffalo, unbeknownst to the latter. And, in the final encounters, we see the book’s four predators – fox, owl, snake, and the Gruffalo – hide from threat through retreat.Footnote 126

There are, of course, limitations to this reading of The Gruffalo as a tale of survival under anarchy. One might, for instance, argue that the relationship between the creatures is hierarchical: that the wood homes something of a food chain rather than a mosaic of roughly equal inhabitants. One might also suggest that predators and prey are not ‘functionally equivalent’, and the relationship between hunter and hunted is hardly a war of all against all.Footnote 127 And yet, the threats encountered by mouse are uniform in their immediate interests (consuming mouse), and the visual unfolding of the book around sequential encounters structurally confined to different pages – means its characters have no wider relationship – conflictual or cooperative; hierarchical or otherwise – to one another. Mouse, moreover, although less materially capable (all three foes explicitly reference mouse’s diminutive size), is as concerned with survival as their predators, and as reliant on their own capabilities. Hence, mouse’s employment of similar tactics such as deception in their efforts to deter those threats.Footnote 128 In this sense, our abstracting from every attribute of the characters except their capabilities is commensurate with realism’s theorisation of the international,Footnote 129 hence our first reading of this text as a recognisable account of survival-seeking behaviour in a self-help world.

Openings and alternatives

Mouse’s successful vanquishing of their foes, then, provides visual and narrative insight into the security dilemma and escape thereof under conditions of international anarchy. In so doing, the book theorises the insecurity – and possibility/absence of conflict – in global politics in a manner familiar to dominant readings thereof through a series of accessible and aesthetically engaging visual and narrative gestures. Taking inspiration from Grayson’s reading of A Bear Called Paddington,Footnote 130 and William Clapton and Laura J. Shepherd’s engagement with Game of Thrones,Footnote 131 we now argue that restricting our understanding of the Gruffalo to this first reading would miss its importance as a critical intervention that also negotiates and destabilises dominant understandings of global politics through engagement with their ontological and epistemological construction and exclusions. To do this, we now offer two alternative readings of The Gruffalo, drawing insight from alternative understandings of world politics, to demonstrate that the book’s significance is (also) in its sustained narrative and visual engagement with the constructed nature of danger, and with issues of positionality and power in the storying of the world.Footnote 132

Reading The Gruffalo as a theorisation of danger’s constructed nature pulls our attention to the processes through which threats are produced, rather than encountered, and to the book’s representation of ideational power. As we have seen, mouse’s ability to escape their opening encounters involves fabrication of a dangerous, threatening other: the Gruffalo. Drawing on Devetak’s reading of Vanita Seth,Footnote 133 mouse’s depiction of this creature – with its poisonous wart, terrible tusks and all – is fearsome because the constructed creature is characteristically monstrous: combining physiological confusion caused by intermingling human and animal body parts, moral ambiguity in its apparent disregard for ethical or social norms, and geographical displacement such that none of the wood’s inhabitants have ever encountered a Gruffalo. The Gruffalo’s monstrous otherness therefore signifies danger and depravity for the wood’s more familiar inhabitants with its appetite for scrambled snake, owl ice cream, roasted fox, and mouse-on-bread; its incremental unmasking through the narrative and inset illustrations adding to the anticipation of danger for readers.

The salacious detail with which its body parts are described and illustrated confirms the Gruffalo’s grotesque abnormality. Neither familiar nor unfamiliar,Footnote 134 the creature’s impossibilityFootnote 135 is radically disruptive for life in the wood. Most immediately, the Gruffalo’s spectre disturbs the physical security of the wood’s residents, forcing them into flight from this threat. Mouse’s invention of the ravening Gruffalo, moreover, also disturbs the ontological security of the wood’s inhabitants; rupturing their sense of the world – and their place therein – as a familiar, predictable, and stable environment.Footnote 136 The presence of the Gruffalo dramatically and fundamentally alters this sense of individual and social continuity, for fox, owl, and snake initially, but subsequently for mouse, too, following the monster’s materialisation. The foreboding or dreadFootnote 137 constructed by this imagined, then encountered, threat is evident from the creatures’ words, and through their illustrated expressions and behaviour, as anxious predators are sent scuttling away at the thought, then sight, of this hitherto-unimagined power.

Mouse’s construction of the Gruffalo, then, offers a succinct and insightful theorisation of the discursive production of security threats. First, the Gruffalo’s monstrosity confirms the exceptionality of insecurity: no ordinary problem is he for our wood’s inhabitants to resolve. Second, the ‘urgency of emergency’Footnote 138 his presence provokes is confirmed by mouse’s temporal and spatial positioning of the Gruffalo’s imminent appearance, ‘Here, by these rocks’, ‘Here, by this stream’, and ‘Here, by this lake’. And, third, as argued below, the imagination and encountering of the Gruffalo alike convinces the wood’s inhabitants that the danger he poses is indeed existential. If the successful securitisation of threats (monstrous or otherwise) requires audience acceptance,Footnote 139 there is little question of that having been secured, here, by mouse.

This theorisation of security as something that is produced, not given, also establishes a wider challenge to conventional understandings of life under conditions of anarchy by demonstrating the limits of materialist ontologies of global politics. The book does this, in the first instance, by illustrating the linguistic and visual production of danger. Not only is mouse able to balance against their initial foes by convincing fox, owl, and snake of their alliance with a greater power. Mouse is also later able to convince the Gruffalo of their own superiority, seeing the book’s titular superpower turn and flee, ‘as quick as the wind’. The outcome of these encounters, crucially, is neither pre-determined, nor materially given. In each instance, it is assumptions about the other’s interests and intentions that guide the characters’ decision-making.Footnote 140 Fox, owl, and snake choose to flee from mouse and again from an apparent Gruffalo/mouse alliance because they trust mouse’s dialogue as much as they distrust the Gruffalo’s intentions. Gruffalo, likewise, is sufficiently secure to journey with mouse through the wood until taking flight at the story’s conclusion. In each instance, then, it is the relational encounter, and the inferences made about the other’s reliability, capabilities, and intentions, that generates its outcome. As rendered most obvious in the mouse/Gruffalo interaction – but applicable to all seven meetings – ‘social threats are constructed, not natural’.Footnote 141

The constructed nature of threat is why revelation of the Gruffalo’s ‘real’ ontological existence has no additional bearing on the predators and their behaviour. The threat posed by the Gruffalo is as powerful whether imagined or manifest. In this sense, the book offers a wider critique of material superiority as the foundation for (state) power within global politics. Each dyadic encounter culminates, counter-intuitively, in success for the materially inferior participant, with mouse able to compel fox, owl, snake and, ultimately, the Gruffalo to their will. Mouse does so by shaping the interests of their foes in order to determine the latter’s behaviour, rather than coercing action through any preponderance of capabilities. Power in the deep, dark wood of The Gruffalo, as such, works not as a resource, but through relationships rooted in, and made fungible through, the ideational: through expectations, perceptions, emotions, and discourse.

The Gruffalo, then, both illustrates and negotiates a traditional understanding of world politics centred on escaping the security dilemma engendered by the anarchical environment of the deep dark wood. The book, put otherwise, is both complicit in, and critical of, conventional understandings of the international as a site of insecurity and fear.Footnote 142 In this final part of our discussion, however, we argue that it goes further still because it also contains a more radical, oppositional, reading that is critical of the broadly realist and constructivist interpretations considered above. This – decolonial – reading is one that deeply unsettles fundamental assumptions about the Gruffalo’s world and its inhabitants.Footnote 143 It does so by ‘unthinking’Footnote 144 or decentring mouse and their story as the book’s taken-for-granted perspective and agent,Footnote 145 and by paying attention to the side-lining of other characters and their experiences.Footnote 146

This third reading of the Gruffalo begins by recognising the book’s narrative and visual emplotment through the journey of one mobile character – one ‘aesthetic subject’Footnote 147 – mouse. Told in the third person throughout, it is mouse’s movement through the wood – and, therefore, through the habitats or homes of its various inhabitants – that sets in motion the encounters driving the narrative. Mouse’s proximity to the territorial residences of fox, owl, and snake is graphically illustrated through visualisation of the logpile house, treetop house, and underground house. In contrast to their antagonists, mouse is seemingly unbound to any fixed abode, licentiously and smilingly ‘strolling’ through the wood.Footnote 148 As noted above, as the only character present on each of the book’s pages, readers are effectively tethered to mouse: nothing happens in the story that does not concern, and is not put in motion by, mouse’s journey.

The different freedoms of movement afforded mouse and the wood’s ‘native’ inhabitants reproduces a long-standing anthropological binary in which ‘non-native observers are regarded as quintessentially mobile – movers, seers, knowers – [while] ‘natives’ are understood as immobile through their belonging to a place’.Footnote 149 In this sense, the book’s focus on mouse’s travels vividly demonstrates the situatedness of (security) knowledge highlighted, in particular, by postcolonial scholarship.Footnote 150 By centring this third reading upon mouse’s journey, we are confronted with the specificity of the book’s security dilemma which, far from universal, is, in fact, the dilemma of its principal subject: mouse. The threats that arise as the plot unfolds are threats (initially) to mouse. And the resolution of those threats is driven by the actions of mouse. Thus, although the book might be read as a conventional stylisation of the politics of security under anarchy (realist and/or constructivist), it may also be taken as a sustained argument about the parochial nature of such stylisations and their particularity to the experiences and actions of privileged characters. Following Tarak Barkawi and Mark Laffey,Footnote 151 the book’s rootedness in mouse’s journey through the wood therefore means it, ‘derives its core categories and assumptions … from [mouse’s] particular understanding’Footnote 152 of that journey. Despite the third person narration, it adopts a consciously taken-for-granted perspective in its analysis of key eventsFootnote 153 in which agency is rooted in the body of the story’s diminutive protagonist.

This narrative emphasis on mouse as the driver of events has twofold importance. First, it works through an empirical partiality such that the actions and interests of the wood’s other characters are revealed only through interaction with mouse.Footnote 154 The story of The Gruffalo is not told from the perspective of fox, owl, snake or, indeed, from that of the Gruffalo. Those characters and their experiences are made relevant only on encounter with mouse. The story of The Gruffalo is therefore a fundamentally provincial one that flattens the wood’s diverse histories, geographies, and relations into a singular story of insecurity even if their wording by an unnamed narrator gestures at impartiality.Footnote 155 Recognising this offers fertile ground for what Edward Said terms a ‘contrapuntal reading’ of the wood/international relations as state of nature focused on recuperating marginalised stories while exploring their intermeshing and theorising their production within this particular power-knowledge nexus.Footnote 156

This problematisation of the empirical partiality underpinning (knowledge of) world politics connects to a second – ethical – partiality,Footnote 157 whereby the book both encourages readers to identify with mouse and – in foregrounding the smugness of its protagonist – asks whether mouse is indeed the powerless creature suggested by the story. As we have seen, the book’s plot unfolds via mouse’s insouciant movement through the habitats of other residents, detailing their ability to render their counterparts insecure, including by wielding the threat of the Gruffalo to their own purposes. This emphasis on one subject’s movement through the woods, in other words, demonstrates how taken-for-granted narratives may generate taken-for-granted politics:Footnote 158 how readers might be encouraged to ‘root for’ specific characters and their particular, embodied, journeys such as in this illustrated, simplified, story.

Once mouse’s movements and metis Footnote 159 are centred thus, The Gruffalo’s value as a decolonial critique of security-seeking behaviour and narratives becomes clearer. Most obviously, the story both relies on and invites readers to question a series of familiar binaries demanding deconstruction.Footnote 160 Where mouse is mobile and agential; fox, owl, and snake are unmoving and responsive. Mouse is storied as individual and unique; their counterparts have no individual importance beyond an equivalence as threats to mouse. Mouse is sophisticated, intelligent, and resourceful; their others are unsophisticated, simple, and primitive. And, mouse, as we have seen, represents reason and cognition with their problem-solving abilities, deviousness, and inner monologue; the other creatures, in contrast, are animalistic, instinctive.

The Gruffalo, however, not only demonstrates the situatedness of (mouse’s) knowledge (of the wood) and of threats to their security. It also highlights how a privileged character is able to ‘world’ shared environmentsFootnote 161 through constituting their interlocutors’ understandings of danger, insecurity, and otherness. The point here is not, only, that the wood’s other characters might story the environment, its norms, and dilemmas differently. But, in addition, that their ability to story their own insecurities has already been shaped or constituted by their encounters with mouse and their constructions. The influence of mouse’s travels in shaping others’ understanding of the wood therefore provokes a reversing of the gaze to ask: how would The Gruffalo be storied from the perspective of snake, or owl, or fox, or the Gruffalo? What security politics would emerge with mouse portrayed as the threat, not the threatened? What unrepresented agency resides with the book’s other characters? And, fundamentally, under what conditions might similar value be attributed to the book’s non-murine lives?

Our focus, in this article, has been on theorising The Gruffalo as a plural and vernacular site of knowledge about (international) (in)security. Although the interpretation with which we began may appear commonsensical given the book’s framing and political realism’s continuing dominance as an interpretive frame,Footnote 162 The Gruffalo also, we argued, works through negotiated and oppositional readings of world politics to offer critical intervention into dominant narratives thereof and their meta-theoretical construction.Footnote 163 This polysemy, as we have seen, not only exposes the ‘messy’ and contested nature of world politics but is a direct product of the narrative and visual content and form of children’s picturebooks: a remarkably neglected site of knowledge within IR and beyond. Taking it seriously forces confrontation with the contestability of any reading of world politics, or indeed popular culture. As Clapton and Shepherd argue, ‘The representations of the international that popular culture provides can either challenge or support conventional understandings or interpretations. Often, many popular cultural texts do both.’Footnote 164

Conclusion

In his discussion of A Bear Called Paddington, Kyle Grayson argues that children’s literature is ‘important and political’ because of its: ‘potential to provide narrative foundations about who one is, and how the world operates’.Footnote 165 In this article we have pursued this insight by arguing that The Gruffalo – a spectacularly successful and much-loved example of the children’s picturebook genre – offers a complex and polysemous theorisation of international politics that: constitutes the international as a pessimistic, anarchical world populated by self-interested, survival-seekers; destabilises this construction through dramatisation of the securitisation of threats; and, enables confrontation with processes of epistemological and normative privileging in the world’s storying. In doing so, moreover, the book actively demonstrates the world’s ‘messiness’ and susceptibility to competing interpretations.Footnote 166

This analysis, we argued, offered empirical, theoretical, and methodological contributions to existing debate, by: (1) engaging with a neglected text and genre; (2) demonstrating the importance of such texts in (re)creating, negotiating, and (de)stabilising (knowledge of) global politics; and, (3) providing a framework for future scholarship via a novel methodological framework. Given the lack of existing literature on children’s picturebooks and IR, we finish by mapping a non-exhaustive list of future research agendas to build on the above.

First, and most obviously, our methodological framework could sustain readings of other children’s picturebooks and their construction of world politics. Such readings could offer comparative insight into portrayals of the international within these books and their subjects. They could explore intertextual links between such books and other texts, for instance in relation to national myths and lore, or political allegory. And, of course, issues of translation and context matter here too. Are picturebooks altered for perceived (in)compatibility with different cultural values? Do books fall in and out of favour as values change? Does the ‘success’ of a book in particular markets demonstrate linkage to specific values?

Second, children’s picturebooks are an important site in which global politics is made manifest intersubjectively through relations between readers and audiences in everyday spaces from bedrooms to libraries and classrooms. There are thus rich opportunities for audience research here, for instance to explore how adults make sense of such books in their reading, and around how or whether such books provoke political conversation. Affective questions will be particularly important, given the capacity of such texts and their encounters to provoke emotions such as pleasure and fear, to generate connections between readers and listeners, and to stimulate new ways of understanding or being in the world.Footnote 167 How, then, do picturebooks differ here from other artefacts or subcultures and their impacts on individuals, communities, and beyond.Footnote 168

Third, building on this, children’s picturebooks also offer potentially important insight into the politics of resistance and/or social values. Future research could look at picturebooks as a corpus of resistance practices and/or sites that affirm dominant narratives. Do picturebooks change their messages over time? How do they engage with issues such as racism? Environmental destruction? LGBTQIA+ rights? Relatedly, future research could actively reflect on the cultural authority of children’s authors to explore their status as ‘public intellectuals or expert voices’ in the public sphere able to comment through their work and beyond it.Footnote 169

Finally, there are rich possibilities for further decolonial work in this area. Among other things, this might include: critical reading of children’s picturebooks published in the Global South; analysis of picturebooks published in languages other than English; engagement with depictions of colonialism, imperialism, and eurocentrism in picturebooks; and, readings of children’s picturebooks through non-Western theories of politics and IR.Footnote 170

Overall, our article has actively set out to demonstrate that children’s picturebooks are far from trivial, disposable curios. They are important sites of world politics offering important insights into world politics. They help us to think more sharply about methods, offer a useful vehicle for theorising the international, and demonstrate an important locus of coalescence between world politics and the everyday. Children’s picturebooks are not ‘just for kids’, and there is rich potential for future research in this nascent field.

Acknowledgements

Our sincere thanks to the anonymous reviewers and editors for their challenging and constructive feedback on earlier drafts of this article.

Video abstract

Video Abstract: To view the online video abstract, please visit: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0260210523000098