Until recently, it has been doubted that personality plays an important role in understanding and predicting individuals’ political attitudes and behaviours. To students who examine social and political behaviour, it seemed to be very difficult to reliably measure and empirically detect any influence from personality. Even if personality appeared to matter, it was simply assumed to serve as a distant predictor, and therefore its impact was presumed to be eclipsed by more immediate demographic and psychological factors.

Studies on the relationship between personality and political behaviour have gained new attention, reflecting a resurgence of interest in and research into personality psychology. The newly generated personality measures are short — yet reliable — enough to be incorporated in large-scale surveys. They eventually lead to a growing number of studies that report a direct, significant effect of personality on political ideology (e.g., Carney, Jost, Gosling, & Potter, Reference Carney, Jost, Gosling and Potter2008; Gerber et al., Reference Gerber, Huber, Doherty, Dowling and Ha2010), party identification (e.g., Gerber, Huber, Doherty, & Dowling, Reference Gerber, Huber, Doherty and Dowling2012a; Vecchione et al., Reference Vecchione, Schoen, Castro, Cieciuch, Pavlopoulos and Caprara2011), political efficacy (e.g., Cooper, Golden, & Socha, Reference Cooper, Golden and Socha2013), political discussion (e.g., Gerber, Huber, Doherty, & Dowling, Reference Gerber, Huber, Doherty and Dowling2012b; Hibbing, Ritchie, & Anderson, Reference Hibbing, Ritchie and Anderson2011), vote choice (e.g., Barbaranelli, Caprara, Vecchione, & Fraley, Reference Barbaranelli, Caprara, Vecchione and Fraley2007; Schoen & Schumann, Reference Schoen and Schumann2007), voter turnout (e.g., Gerber et al., Reference Gerber, Huber, Doherty, Dowling, Raso and Ha2011; Mattila et al., Reference Mattila, Wass, Söderlund, Fredriksson, Fadjukoff and Kokko2011), and non-electoral political participation (e.g., Gallego & Obserski, Reference Gallego and Oberski2011; Mondak, Hibbing, Canache, Seligson, & Anderson, Reference Mondak, Hibbing, Canache, Seligson and Anderson2010). It is also known that personality traits exert a direct influence on citizens’ opinion on a specific political issue such as the usage of military force in foreign affairs (Schoen, Reference Schoen2007) and immigration (Vecchione, Caprara, Schoen, Castro, & Schwartz, Reference Vecchione, Caprara, Schoen, Castro and Schwartz2012).

This article expands on recent work on personality and political behaviour by examining the relationship between personality traits — measured by the Five-factor Model — and South Koreans’ attitudes toward North Korea. The data are based on face-to-face, nationally representative surveys using a multi-stage probability sampling, and include a brief measure of personality. Given that attitudes toward North Korea are arguably the most important determinant of ideological division between right-wing conservatism (i.e., anti-North Korea) and left-wing progressivism (i.e., pro-North Korea) in South Korea (Jang, Reference Jang2011), past research suggests that personality traits — particularly, Conscientiousness (characterised by rule-abiding attitudes and compliance to norms) and Openness (characterised by intellectual curiosity and open-mindedness) — are expected to directly affect South Koreans’ views on North Korea. This study offers a set of findings from a country where the role of personality in the political arena has rarely been explored (see Ha, Kim, & Jo, Reference Ha, Kim and Jo2013, for an exception). These findings confirm the well-reported relationship between Conscientiousness and conservatism and between Openness and progressivism.

Personality Traits and Political Ideology

Personality psychologists have made tireless efforts to develop taxonomies that classify individuals according to a small number of personality dimensions (Allport & Odbert, Reference Allport and Odbert1936; Cattell, Reference Cattell1943; Eysenck & Eysenck, Reference Eysenck and Eysenck1976; Costa & McCrae, Reference Costa and McCrae1992). Several constructs are now available, among which the Five-factor Model (i.e., the ‘Big Five’) has been widely accepted as a valid and reliable measure of personality (Gosling, Rentflow, & Swann, Reference Gosling, Rentfrow and Swann2003; John, Naumann, & Soto, Reference John, Naumann, Soto, John, Robins and Pervin2008).

The five dimensions of personality are Conscientiousness, Openness, Emotional Stability (also referred to by its reverse, Neuroticism), Agreeableness, and Extraversion: Conscientiousness involves the degree to which an individual is well-organised, scrupulous, and industrious; Openness refers to the degree to which an individual is open-minded, imaginative and original; Emotional Stability means the degree to which an individual is anxiety-free, is immune to stress, and is less prone to negative affect; Agreeableness refers to the degree to which an individual is soft-hearted, sympathetic, generous, and gets along well with others; and Extraversion involves the degree to which an individual is energetic, outgoing, and assertive (Funder & Fast, Reference Funder, Fast, Fiske, Gilbert and Lindsey2010). The Big Five is known to correspond to consistent attitudinal and behavioural patterns of individuals across various social contexts (Funder, Reference Funder, John, Robins and Pervin2008).

A significant amount of research has been conducted regarding the relationship between personality and political behaviour, among which the most robust finding is observed in the area of political ideology: Conscientiousness is more likely to be associated with conservative or right-wing ideology, while Openness is more likely to be linked with progressive or left-wing ideology (e.g., Carney et al., Reference Carney, Jost, Gosling and Potter2008; Gerber et al., Reference Gerber, Huber, Doherty, Dowling and Ha2010). Individuals high on Conscientiousness are expected to be attracted to social norms and traditions. Therefore, they are more likely to reject the challenges to social norms by defending the status quo. Conversely, Openness is expected to correspond to open-minded attitudes to novel stimuli. Thus, individuals high on this trait are more likely to be in favour of social changes, which usually require a willingness to accept unconventional behaviours.

Findings regarding the relationship between other three personality dimensions (i.e., Agreeableness, Emotional Stability, and Extraversion) and political ideology are not conclusive. Prior research has not typically found any statistically significant relationship between Agreeableness and political ideology (e.g., Gosling et al., Reference Gosling, Rentfrow and Swann2003), though a study based on a large convenient sample (Carney et al., Reference Carney, Jost, Gosling and Potter2008) reports a weak association with right-wing ideology. Such a relationship is observed presumably because a set of facets (i.e., subdimensions within a single personality trait) linked with Agreeableness such as conflict avoidance and compliance to community values make individuals reluctant to disturb pre-existing social relationships. However, if another aspect of this trait — for example, sympathy — is highlighted, it may also be reasonable to conceive that Agreeableness is rather linked with progressive ideology, as people high on this trait are likely to be supportive of disadvantaged groups. Emotional Stability is occasionally found to correlate with conservatism (Carney et al., Reference Carney, Jost, Gosling and Potter2008; Gosling et al., Reference Gosling, Rentfrow and Swann2003). This empirical finding notwithstanding, the likely relationship between Emotional Stability and political ideology is not intuitively clear. On one hand, individuals high on this trait may be progressive because they may not feel threatened by changes to status quo. On the other hand, those low on this trait may also be able to harbour left-wing orientations because the higher levels of grievances they might hold will ask for social changes. Finally, there seems no theoretical reason to believe that Extraversion is associated with political ideology, though its inclination toward conservatism has sporadically been reported (e.g., Carney et al., Reference Carney, Jost, Gosling and Potter2008).

South Koreans’ Attitudes Toward North Korea: Hypotheses

In order to predict the possible relationships between personality traits and opinions on a specific social or political issue, it is necessary to identify the dominant discourses regarding that issue. In terms of the relationship between two Koreas, the shared norms in South Korean politics have been characterised by (1) pro-US foreign policy, (2) non-recognition of North Korea as an independent nation-state, and (3) South Korea-led unilateral reunification. Ever since the division between North and South Koreas in 1948, South Koreans have been taught to hold anti-North Korea attitudes and, as a corollary, pro-American attitudes: North Korea is a hostile country that should eventually be absorbed by South Korea to be a single, independent nation-state, and the alliance with the United States needs to be fortified in order to achieve this goal. These ideas have never been challenged until the outburst of anti-American sentiments and mass protests against authoritarian rules in South Korea, which happened to overlap with the end of the Cold War in the late 1980s and early 1990s. Furthermore, a new approach to the relationship between two Koreas — labelled the ‘Sunshine Policy’, characterised by humanitarian aids and government-led cooperative business developments — during the period between 1997 and 2008 dramatically changed conventional views on North Korea, and caused a sharp ideological division in both elites and mass public, that is, anti-North Korea attitudes as conservatism versus sympathy toward North Korea as progressivism (Jang, Reference Jang2011).

Having said that, one can generate a set of hypotheses that examine the relationship between the personality traits and attitudes toward North Korea. First off, South Koreans who are conscientious — characterised by compliance to norms — are less likely to feel close to North Korea than any other neighbouring countries, to believe that North Korea is a hostile nation, and to be generally sceptical of the possibility of a gradual and peaceful reunification. By contrast, people high on Openness — characterised by open-mindedness to new ideas — are likely to feel closer to North Korea, to harbour relatively positive attitudes toward North Korea, and to be optimistic about the possibility of a peaceful reunification. Hypotheses that involve the other three personality dimensions are not clear in terms of their direction. As long as Agreeableness is characterised by compliance to community values, it is expected to correspond to conservative ideology, that is, negative attitudes toward North Korea and scepticism on peaceful reunification. But, sympathy or benevolence (another important facet of Agreeableness) toward North Koreans may lead people high on Agreeableness to support more lenient policies toward North Korea. Emotionally stable individuals are less likely to feel threatened by social changes and therefore they are more likely to embrace new approaches to North–South relations. But one cannot rule out the possibility that emotionally stable people are more likely to be conservative because they tend to have higher levels of life satisfaction (e.g., Steel, Schmidt, & Shultz, Reference Steel, Schmidt and Shultz2008). Due to lack of theoretical reason, a hypothesis regarding Extraversion is not offered.

Data and Measure

Data come from the 2009 and 2011 Korean General Social Survey (KGSS). The KGSS is a nationally representative, face-to-face interview survey, conducted every year since 2003.Footnote 1 The sampling procedure and interviewing methods are virtually identical to those of the General Social Survey (GSS) of the United States. The core questions are generally compatible with those of the GSS and the modules are shared with the International Social Survey Programme (ISSP) and the East Asian Social Survey (EASS). The surveys used in the present study took place during the summer of 2009 and 2011, an unusually conflictual period highlighted by the sinking of a South Korean Navy ship (allegedly by a North Korean torpedo) in April 2010 and the bombardment of a South Korean island by North Korean forces in November 2010. So, it is safe to assume that conservatives have gained more power in public discourses in 2011, and changes in political environment may influence survey responses in 2011. The surveys had a response rate of 63.4% (n = 1,602) in 2009 and 65.2% (n = 1,535) in 2011.

The survey includes a carefully translated, Korean version of the Ten Item Personality Inventory (TIPI). Originally developed by Gosling et al. (Reference Gosling, Rentfrow and Swann2003), the TIPI is ideal in a large-scale survey because it is relatively short. This battery asks respondents to report how well 10 pairs of traits (e.g., ‘Extraverted, enthusiastic’, ‘Anxious, easily upset’, ‘Conventional, uncreative’) describe themselves (see Appendix A for details). That said, the TIPI is composed of 20 adjectives (10 pairs) in total, and 2 pairs of adjectives are assigned to measure each of the five dimensions of personality traits. Each item contains a self-reported statement that reflects the Big Five personality’ dimensions and is rated on a 7-point scale. Responses are rescaled to range from 0 to 1. The bivariate correlations between the couple of items that form each of the Big Five are modest, ranging from .24 to .45. Though not ideal, inter-item correlations between the two items used to measure each trait may be less informative, because the TIPI originally intends to cover a variety of facets of each dimension of personality with two pairs of adjectives, without considering the possibility of maximising inter-item reliability (Gosling, Reference Gosling2009). In the 2009 KGSS, 1,596 respondents answered all the TIPI questions, and the equivalent number of respondents was 1,527 in the 2011 survey.

The correlations among the Big Five are listed in Table 1. The fact that the mean values of personality traits (see Table 2 for the summary statistics) and correlations among them are virtually identical across two surveys suggests that the measures are consistent over time, that is, not being malleable depending on the sudden changes in political climate. As the largest correlation is .29 (between Conscientiousness and Emotional Stability) in 2009 and .31 (between Extraversion and Openness) in 2011, the personality dimensions seem to be independent of each other. It is intriguing that some of the five personality dimensions are negatively correlated in the Korean TIPI, because they all tend to be positively correlated — perhaps due to social desirability — in the Western cultures. These negative correlations may be explained by cultural differences. A study reports that in the Confucian tradition, both Extraversion and Openness are likely to be viewed negatively, while Agreeableness and Emotional Stability tend to be viewed positively (Leung & Bozionelos, Reference Leung and Bozionelos2004). As a consequence, people are more likely to disapprove of those who are outgoing and embrace new, unconventional ideas, and therefore, such a prevalence of Confucian legacies reflects the tendency of prioritising community values over individual rights in East Asian cultures.

Table 1 Correlation Matrix of the Big Five Personality Dimensions

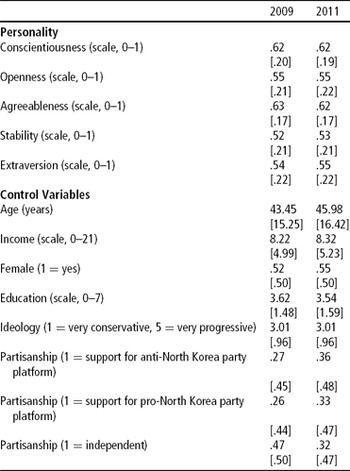

Table 2 Summary Statistics of the Variables Included in the Models

Note: Cell entries are mean values, with standard deviations in brackets.

Three questions serve as the dependent variables in statistical analysis. The first dependent variable is based on a question that intends to measure the degree of the respondents’ emotional attachment to neighbouring countries. This is a closed-ended question that includes five countries, — the United States, North Korea, Russia, Japan, and China — as answering options. A majority of the respondents (60.7%) report close emotional attachment to the United States, while 16.4% of them feel close to North Korea in 2009. In 2011, one can observe the same pattern, but more people (68.4%) report close emotional attachment to the United States, while fewer people (11.2%) feel close to North Korea. Such an attitudinal difference at the aggregate level seems to reflect above-mentioned changes in political climate between two survey years. The percentages of the respondents who feel attached to other three countries are relatively small: 1.3% for Russia, 9.9% for Japan, and 6.7% for China in 2009; and 1.1% for Russia, 8.7% for Japan, and 4.7% for China in 2011. As any significant differences are not expected regarding these three countries, a new category that merges all of them is created and is used in data analysis.

The second dependent variable is based on a question that intends to measure the respondents’ cognitive perceptions on the relationship between North and South Koreas. This is also a closed-ended question that includes four answering categories: (1) North Korea is in need of support from South Korea (chosen by 14.3% of the respondents in 2009 and 13.3% in 2011); (2) North Korea is a cooperative partner with South Korea (32.1% in 2009 and 20.7% in 2011); (3) North Korea is an untrustworthy country (35.4% in 2009 and 45.6% in 2011); and (4) North Korea is a hostile country (15.9% in 2009 and 18.4% in 2011). Here again, the big disparity in terms of the proportion of people who believe North Korea is a cooperative partner between two survey years indicates a dramatic shift of public mood toward conservative stances in 2011.

Finally, the third dependent variable is asking the respondents’ attitudes toward reunification between North and South Koreas. This variable is a 4-point scale, ordered variable, and its answering options range from reunification is not necessary at all to reunification is very necessary. A majority of South Koreans believe that reunification is either ‘very necessary’ (33.2% in 2009 and 32.3% in 2011) or ‘somewhat necessary’ (37.6% in 2009 and 36.0% in 2011). The percentages of the respondents who report ‘not necessary’ (22.4% in 2009 and 23.6% in 2011) or ‘not necessary at all’ (5.6% in 2009 and 6.9% in 2011) are relatively small.Footnote 2

Along with personality traits, various covariates are included in the models. The first set of covariates includes socio-demographic variables: age (measured in years), income (coded in 21 categories), gender (a dummy variable), and education (coded in 8 categories). The other set of variables is political ideology (a 5-point scale variable) and party identification. Party identification is a set of three dummy variables that reflect (1) people who support or are in favour of political parties (United Democratic Party, Creative Korea Party, and Democratic Labor Party in 2009 and Democratic Party, Creative Korea Party, Democratic Labor Party, and The Participation Party in 2011) of which official policy positions are more or less consistent with the ‘Sunshine Policy’; (2) those who support or are in favour of political parties (Liberal Forward Party, Grand National Party, New Progressive Party, and Pro-Park United in 2009 and Grand National Party, Liberal Forward Party, Future Hope Alliance, and New Progressive Party in 2011) of which official policy positions are relatively at odds with the ‘Sunshine Policy’; and (3) those who are purely Independent.Footnote 3

Including these covariates makes data analysis conservative, because studies have shown some covariates (e.g., income, education, political ideology, and party identification) are at least partially endogenous to personality (e.g., Carney et al., Reference Carney, Jost, Gosling and Potter2008; Gerber et al., Reference Gerber, Huber, Doherty, Dowling and Ha2010). As they would somewhat absorb the effects of personality traits, one could view any statistically significant, direct relationships between personality and attitudes toward North Korea in the analysis as substantial. But, it is not the main intention of this article to identify causal mechanisms that link personality traits with opinions on North Korea. The scope of the present study is strictly limited to detecting the ‘direct’ effect of personality on South Koreans’ attitudes toward North Korea, primarily because there is now convincing evidence that the conventional, regression-based mediation analysis tends to lead to biased results, particularly when relying on non-experimental data like surveys (e.g., Bullock, Green, & Ha, Reference Bullock, Green and Ha2010). The variables’ coding and the wording of their questions are available in Appendix A.

The results include cluster robust standard errors at the province level to allow for the interdependence of individuals in a given province. The province-level fixed effects are also considered to ensure that the results are not the products of some correlation between personality traits and other unobserved factors that might affect attitudes toward North Korea (e.g., province-level socio-cultural differences). Two of the dependent variables are measured in an unordered scale (i.e., emotional attachment to neighbouring countries and attitudes toward North Korea), and therefore multinomial logit is employed. For the dependent variable that measures people's attitudes toward reunification (in a 5-point, ordered scale), ordered logit is utilised.

Results

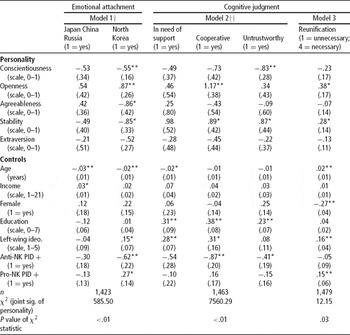

The results from statistical analysis of the 2009 survey are reported in Table 3. Model 1 estimates the effects of personality and other covariates on South Koreans’ feelings toward some neighbouring countries. These results reveal that personality traits are associated with South Koreans’ attitudes toward neighbouring countries: after controlling for other covariates, people high on Openness are likely to feel closer to North Korea than the United States (a reference category in the model), while those high on Conscientiousness, Agreeableness, and Emotional Stability are less like to feel close to North Korea than the United States. These findings are consistent with the proposed hypotheses: Conscientiousness characterised by norm compliance, Agreeableness characterised by conformity to community values, and Emotional Stability characterised by life satisfaction are all expected to be associated with conservative attitudes, while Openness characterised by curiosity and open-mindedness is supposed to relate to progressive ideas. Meanwhile, personality traits do not yield any statistically significant differences between attitudes toward the United States and those toward Japan/China/Russia. In this model, the Big Five traits are jointly significant (p value associated with Chi-square test of joint significance is smaller than .01), and it suggests that personality traits by themselves can serve as important predictors of South Koreans’ feelings toward North Korea.

Table 3 Personality Traits and South Koreans’ Attitudes Toward North Korea (The 2009 KGSS)

Note: Coefficients and robust standard errors in parentheses (clustered by province) come from multinomial logit (Model 1 and Model 2) and ordered logit (Model 3); fixed-effects at the level of province are considered, but not reported here.

**p < .01; *p < .05 (two-tailed)

† ‘The United States’ as a reference category

†† ‘Hostile’ as a reference category

+ ‘Independent’ as a reference category

Model 2 demonstrates the effects of personality and other factors on South Koreans’ views on North Korea. Consistent with the proposed hypothesis above, people who are conscientious are more likely to consider North Korea hostile (a reference category) than untrustworthy, while those high on Openness are more likely to believe that a cooperative relationship between South and North Koreas is possible. However, people who are emotionally stable are less likely to see North Korea as hostile; rather, they tend to consider her as a cooperative partner or simply an untrustworthy country. This finding is not necessarily consistent with that in Model 1, which suggests that Emotional Stability is positively associated with conservatism. So, no conclusive evidence exists regarding the association between Emotional Stability and political ideology.

The effects of personality traits tend to be held in the case of South Koreans’ attitudes toward reunification as well. Model 3 demonstrates that Openness and Emotional Stability are positively associated with support for reunification. Assuming that reunification means a peaceful reunification via a long-term cooperation between two Koreas, the finding regarding Openness makes sense as this trait is unequivocally associated with new ideas and progressivism. But, the finding regarding Emotional Stability, like that in Model 2, seems to be at odds with that in Model 1.

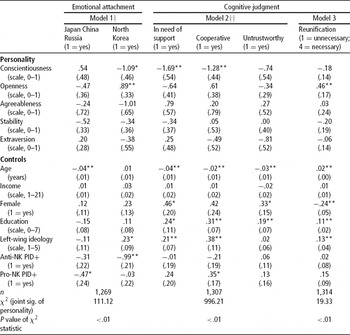

Table 4 lists a set of results from analysis of the 2011 survey dataset. The results are fairly similar to those in 2009. A few personality variables lose their statistical significance, but still keep the same directions as shown in Table 3. Since statistically significant findings are shown only in the case of Conscientiousness and Openness, they are much simpler and easier to interpret. According to Model 1, people high on Conscientiousness are less likely to feel close to North Korea than the United States (a reference category), whereas those high on Openness are more likely to feel close to North Korea than the United States. Model 2 reveals that conscientious people hold conservative stances regarding the relationship between two Koreas. They are less likely to see North Korea ‘in need of support’ or ‘cooperative’, rather being more likely to consider her ‘hostile’ (a reference category). In a similar vein, Model 3 presents that Openness is positively associated with support for reunification.

Table 4 Personality Traits and South Koreans’ Attitudes Toward North Korea (The 2011 KGSS)

Note: Coefficients and robust standard errors in parentheses (clustered by province) come from multinomial logit (Model 1 and Model 2) and ordered logit (Model 3); fixed-effects at the level of province are considered, but not reported here.

**p < .01; *p < .05 (two-tailed)

† ‘The United States’ as a reference category

†† ‘Hostile’ as a reference category

+ ‘Independent’ as a reference category

To demonstrate the relative importance of the associations between personality and attitudes toward North Korea, the effect sizes of some of the key independent variables are presented by calculating the min–max (‘full dose’) effects (Long & Freese, Reference Long and Freese2005). Figure 1 (the left column) shows that, with other variables fixed at their mean values, an increase in Conscientiousness, from its minimum to its maximum values, correlates with a 5.7%-point decrease in a respondent's likelihood of having positive feelings toward North Korea (95% CI: [−9.9, −1.4]), while an equivalent increase in Openness corresponds to a 9.4%-point increase in one's likelihood of having positive feelings toward North Korea (95% CI: [3.4, 15.4]) in 2009. It is noteworthy that the effect sizes of personality traits are quite comparable with that of political ideology (i.e., positive 8.2%-point). This means that, other things being equal, the differences in emotional attachment to North Korea between an individual with the lowest level of Openness and another individual with the highest level of Openness (i.e., 9.4%-point) are slightly greater than those between an individual who is very conservative and another individual who is very progressive (i.e., 8.2%-point).

Figure 1 Predicted probability of personality and political ideology on feelings toward other countries.

Note: The predicted probabilities — ‘min-max’ effects — are calculated following Long and Freese (Reference Long and Freese2005). Based on the results reported in Table 2 and Table 3 (Model 1), the predicted probabilities for all answering categories of the dependent variable are shown. The vertical lines indicate the mean values of personality traits and political ideology.

Similar results are found in 2011 (see the right column of Figure 1): an increase in Conscientiousness, from its minimum to its maximum values, correlates with a 11.7%-point decrease in the likelihood of having positive feelings toward North Korea (95% CI: [−21.8, −1.7]), whereas an equivalent increase in Openness corresponds to a 8.2%-point increase in one's likelihood of having positive feelings toward North Korea (95% CI: [3.7, 12.8]). These effect sizes are approximately on par with that of political ideology, which is 8.6%-point (95% CI: [1.8, 15.5]).

Comparisons of the effect sizes are also relevant regarding South Koreans’ attitudes toward North Korea (see Figure 2). In 2009, with other factors fixed at their mean values, an increase in Conscientiousness, from its minimum to its maximum, yields a 7.9%-point increase in the likelihood of a respondent thinking North Korea is a hostile country (95% CI: [1.8, 14.1]). A similar increase in Openness correlates with a 19.1%-point increase in the likelihood of a respondent thinking North Korea is a cooperative partner with South Korea (95% CI: [7.6, 30.5]). In 2011, the equivalent effect size of Conscientiousness is 13.4%-point (95% CI: [3.4, 23.3]), and that of Openness is 15.1%-point (95% CI: [7.4, 22.9]). According to Figure 2, these effect sizes are comparable with that of political ideology.

Figure 2 Predicted probability of personality and political ideology on attitudes toward North Korea.

Note: The predicted probabilities — ‘min-max’ effects — are calculated following Long and Freese (Reference Long and Freese2005). Based on the results reported in Table 2 and Table 3 (Model 2), the predicted probabilities for all answering categories of the dependent variable are shown. The vertical lines indicate the mean values of personality traits and political ideology.

Similar findings are observed in the case of South Koreans’ attitudes toward reunification (see Figure 3). In 2009, an increase in Openness, from its minimum to its maximum, yields a 13.6%-point increase in the likelihood of a respondent thinking reunification between North and South Koreas is ‘very necessary’ (95% CI: [1.8, 25.3]). In 2011, the min-max effect of Conscientiousness is negative 6.4%-point (95% CI: [−16.1, −3.2]). A similar increase in Openness correlates with a 16.2%-point increase in the likelihood of a respondent thinking reunification is very necessary (95% CI: [5.5, 27.0]). Figure 3 demonstrates a similar pattern observed in the case of political ideology.

Figure 3 Predicted probability of personality and political ideology on attitudes toward reunification.

Note: The predicted probabilities — ‘min–max’ effects — are calculated following Long and Freese (Reference Long and Freese2005). Based on the results reported in Table 2 and Table 3 (Model 3), the predicted probabilities for all answering categories of the dependent variable are shown. The vertical lines indicate the mean values of personality traits and political ideology.

Discussion

These results demonstrate that there are statistically significant and substantively important relationships between personality traits and key measures of South Koreans’ attitudes toward North Korea. The results showing personality traits directly affect opinions on North Korea, even after controlling for other potential determinants, suggests that personality traits can help to explain some of the attitudinal variations that researchers have usually consigned to the error term in standard public opinion models. The analyses indicate that Conscientiousness and Openness to Experience correlate with conservative (right-wing) and progressive (left-wing) positions, respectively, regarding emotional attachment to neighbouring countries, views on North Korea, and opinions on reunification. People who are conscientious are less likely to feel close to North Korea than any other neighbouring countries, and more likely to consider North Korea as a hostile nation. To the contrary, people high on Openness are more likely to feel close to North Korea, more likely to think that North Korea is a cooperative partner with South Korea, and more likely to believe that reunification between two Koreas are necessary. Here, the magnitudes of these associations are comparable to those of other predictors, such as political ideology. It is particularly noteworthy that the effects of personality on South Koreans’ attitudes toward North Korea are more or less similar across two survey years, given that public mood in South Korea might be completely different between 2009 and 2011. In this vein, the findings of the present study confirm that the direct effect of personality traits on political behaviour tend to be relatively stable, not easily being subject to changes in the environment.

The results in this article are consistent with many findings from previous studies on the relationship between personality and political ideology, and therefore, largely strengthen the external validity. However, certain differences should not be understated. It is particularly puzzling why the findings regarding Emotional Stability are mixed. Equally puzzling is why Agreeableness correlates negatively with left-wing orientations in South Korea, particularly in 2009. One could wonder whether this study's instruments had some problems in incorporating various facets (i.e., subdimensions) within a personality dimension or simply unintended errors in terms of translation, although the Big Five personality traits, when measured using longer instruments, are reported to be reliable across cultures (e.g., John et al., Reference John, Naumann, Soto, John, Robins and Pervin2008). As the TIPI is a very short battery, it is possible that its Korean version disproportionately draws from a few facets of certain personality traits at the expense of others. For example, Agreeableness turns out to correlate with conservatism in terms of attitudes toward North Korea, because the Korean TIPI overestimates one facet of Agreeableness — conformity to social norms — that makes South Koreans reluctant to accept new ideas regarding the North–South relations, while it underestimates some other facets, such as benevolence, altruism or sympathy, which may facilitate positive attitudes toward North Korea. This issue needs to be addressed by employing slightly longer batteries (e.g., the 44-item Big Five Inventory [BFI] or a 60-item version of the HEXACO-PI-R) that contain a variety of facets for each personality dimension.

Some weaknesses notwithstanding, the findings from the present study provide optimism regarding a new direction of political behaviour research, as they clearly suggest personality has significant direct effects not only on political ideology — an overarching set of political orientations — but also on public opinion on a specific issue in a non-Western context. The direct effect of personality on public opinion is large enough, even after controlling for some factors that are well known to be influenced by personality traits. It is particularly notable that the personality measures in the KGSS appear, on face value, to have little to do with politics. The fact that personality measures apparently unrelated to politics are significant predictors of public attitudes in the political arena suggests insights into how fundamental psychological differences across individuals shape political behaviour in general and public opinion on a specific political issue in particular.

Appendix A VARIABLE CODING AND QUESTION WORDING

Personality: TIPI (10 trait pairs)

Here are a number of personality traits that may or may not apply to you. Please write a number next to each statement to indicate the extent to which you agree or disagree with that statement. You should rate the extent to which the pair of traits applies to you, even if one characteristic applies more strongly than the other. I see myself as:

Extraversion: Extraverted, enthusiastic; Reserved, quiet (Reverse coded)

Agreeableness: Sympathetic, warm; Critical, quarrelsome (Reverse coded)

Conscientiousness: Dependable, self-disciplined; Disorganised, careless (Reverse coded)

Emotional Stability: Calm, emotionally stable; Anxious, easily upset (Reverse coded)

Openness: Open to new experiences, complex; Conventional, uncreative (Reverse coded)

(1 = Disagree strongly; 2 = Disagree moderately; 3 = Disagree a little; 4 = Neither agree nor disagree; 5 = Agree a little; 6 = Agree moderately; 7 = Agree strongly. Responses rescaled to range from 0 to 1.)

Dependent Variables

Emotional Attachment to Neighboring Countries: ‘Among the following countries, which country do you feel closest to?’ (1 = The United States; 2 = Japan; 3 = North Korea; 4 = China; 5 = Russia)

Attitudes toward North Korea: ‘What do you think North Korea is to us? Please choose one among the following.’ (1 = a country that is in need of our support; 2 = a cooperative partner; 3 = an untrustworthy country; 4 = a hostile country)

Attitudes toward Reunification: ‘To what extent do you think the reunification between South and North Koreas is necessary?’ (1 = very necessary; 4 = not necessary at all)

Other

Female: 0 = Male; 1 = Female

Age: Years

Education: 0 = No schooling; 1 = Elementary school; 2 = Middle school; 3 = High school; 4 = 2-year College; 5 = Bachelor's degree; 6 = Master's degree; 7 = Doctoral degree

Family income (Monthly): 0 = No Income; 1 = Less than 500K Won; 2 = 500K–990K; 3 = 1,000K–1,490K; 4 = 1,500K–1,990K; 5 = 2,000K–2,490K; 6 = 2,500K–2,990K; 7 = 3,000K–3,490K; 8 = 3,500K–3,990K; 9 = 4,000K–4,490K; 10 = 4,500K–4,990K; 11 = 5,000K–5,490K; 12 = 5,500K–5,990K; 13 = 6,000K–6,490K; 14 = 6,500K–6,990K; 15 = 7,000K–7,490K; 16 = 7,500K–7,990K; 17 = 8,000K–8,490K; 18 = 8,500K–8,900K; 19 = 9,000K–9,490K; 20 = 9,500K–9,990K; 21 = More than 10,000K (Approximately 1 USD = 1,200 Won)

Political ideology: 1 = Very Liberal; 2 = Somewhat Liberal; 3 = Moderate; 4 = Somewhat Conservative; 5 = Very Conservative

Partisanship (A set of dummies): Supporters of political parties with pro-North Korea (pro-’Sunshine policy’) orientations; Supporters of political parties with anti-North Korea (anti-’Sunshine policy’) orientations; Independents (reference category)

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea Grant funded by the Korean Government (NRF-2010-330-B00128).