In this article, I trace the patterns of sugar product consumption in seventeenth-century New England, from port to countryside, and I explore the way in which economic exchange between New England and Barbados lay at the core of the development of both regions. My research deepens our understanding of the rise of slavery-based tropical commodity production and consumption in the Atlantic world; I examine the ways in which the emergence of both capitalism and global imperialism in the early modern world were connected to the primacy of sugar as one of the most widely distributed early modern commodities. How did sugar products move differently through societies than did the durable goods that have received greater scholarly attention? How might a reconceptualization of colonial sugar, molasses, and rum consumption inform interpretations of the intertwined rise of capitalism and slavery? And how can expanded research into the history of the Atlantic sugar trade enrich our knowledge of New England’s economy and material culture?

My research also contributes to the scholarly conversation about the nature of early modern capitalism. Historians have focused heavily on the significance of the development of a profit-oriented culture in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries; I argue that the emergence of capitalism during this period should also be understood as an expression of preexisting consumer behaviors unleashed with torrential force with the vanquishing of environmental and other structural limitations on production. Further, the explosion of demand was not simply an accommodation to a changing socioeconomic system but also a driver of it. The premodern demand of English people for sugar must be considered as a factor in efforts to secure and develop the English colonies and Atlantic markets. The English migrants who settled Massachusetts Bay and Barbados in the first half of the seventeenth century—many of them families with kin in both colonies—brought with them a habituation to sugar, a powerful predilection that was particularly striking within the context of their explicit rejection of early modern consumer culture. This demand had long been pushing up against structural supply constraints, as imperial rivalries inhibited the flow of sugar imports into England. English imperialism, in which New England played a key part, resulted in the greater ease of movement of commodities (as well as people) and, above all, sugar products. Demand was not simply satisfied by these developments; rather, it played a causal role.

This article examines the role of mass consumption in fostering the intertwined growth of markets, slavery, and capitalism. Historians have long recognized the importance of sugar as a vehicle of capital accumulation, of its production zones as markets for British industrial goods, and of sugar plantations themselves as early models of industrial organization. Yet sugar’s influence as a consumer good that spurred growth and permanently altered structures and behavior has not been as well explored.Footnote 1 Instead, the scholarship that does attend to the relationship between consumption and the early growth of merchant capitalism focuses mostly on the European fascination with other rare and exotic goods, particularly spices.Footnote 2 I argue that sugar was no less a singular and potent force in the history of capitalism.

In this way, I endeavor to connect scholarship on the “sugar revolution” of the West Indies, which traces the rise of sugar monoculture and slave labor, with our understanding that the “consumer revolution,” the change in the way people perceived and pursued material goods, was as important as the expansion of production in laying the groundwork for the industrial revolution. Scholars of the early modern world have emphasized the significance of the spread of durable goods, the reorganization of work, and the technological changes that marked the first stages of the Industrial Revolution. Yet sugar, molasses, and rum were so valuable, and consumers’ appetites for them so voracious, that it is difficult to overstate the historical importance of their trade and consumption. Economic historian David Eltis notes that in the seventeenth century, Barbados alone “was probably exporting more [by value], proportionate to its size and population, than any other colony or state of its time or, indeed, in the history of the world up to that point.”Footnote 3 This shift, to a world economy based on colonial production of tropical goods to meet a seemingly insatiable consumer demand, was as integral to the emergence of industrial capitalism as the agricultural, technological, and organizational changes that have received so much attention.

Consumer historians Carole Shammas and Anne McCants have argued that the explosion of demand for tropical groceries (of which sugar was the most prominent) after 1600 was far more central to the economic development of Britain and Europe than most historians have acknowledged. In 1559, these groceries were less than 9 percent of imports by value into England and Wales; in 1772, they were almost 36 percent. McCants’s work on early modern Amsterdam finds near universal coffee and sugar consumption across all classes, even the poorest, by 1750. Aside from generating massive profits for producers, shippers, and retailers, use of these “luxury” tropical commodities transformed populations into globally linked consumers who shifted their economic calculations to gain access to these goods. Though far from a sufficient condition for the spread of capitalism, this reorientation toward consumption was a necessary one. And tropical groceries possessed unique characteristics that quickly overwhelmed traditional constraints on consumer behavior, forging a new economic system.Footnote 4

Sugar was also one of the few colonial crops that was utterly dependent on the coercive nature of slave labor to synchronize production levels with demand. So dominant was the sugar industry in the slave trade, and so prominently does the commodity figure in the history of empire, that documenting and analyzing sugar consumption is essential to understanding the trajectory of the early modern political economy. As Barbara Solow asserts, “The demand for slaves is in part derived from the demand for particular commodities, and shifts in world demand for them and the elasticity of that demand will be an explanatory factor for the adoption of slavery. …It is not possible to say what the history of modern slavery would have been without sugar, but it is perfectly possible to wonder.”Footnote 5

Yet the sixteenth-century and seventeenth-century Atlantic sugar market remains poorly understood, as do many aspects of early modern eating habits.Footnote 6 Economists and historians have not fully explored the nature of demand for food, assuming it was a static commodity whose demand elasticity could be explained mostly by changes in prices.Footnote 7 But for most commodities, including foods and especially sugar, the nature of demand is much more complex, requiring a synthesis of quantitative study and cultural analysis.

New England and the Atlantic Sugar Market

The Massachusetts Bay colony (1628) and the colony of Barbados (1627) were established within a year of each other. New England served as an anchor for the development of Barbados during the pivotal period of 1630-1660; Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and Connecticut supplied much of the food, timber, and other basic needs of the island, and great numbers of people as well as goods flowed back and forth between New England and the Caribbean.Footnote 8 By 1688, about two-thirds of export commodities leaving Boston went to the West Indies. New England’s natural resources, principally timber products and fish, and agricultural products such as salt beef and pork, dairy, and live animals, found by far their biggest market in the sugar islands, which, by outsourcing these agricultural products, were able to build an industrial economy based on slavery and sugar. As Barbados planters explained to Parliament in 1673, “[T]hey could not maintain their buildings, nor send home their sugars, nor make above half that quantity with out a supply of those things from New England.”Footnote 9 Equally important was New England’s dominance of the island’s export trade, shipping the island’s sugar products to England or reexporting them up and down the North American coast.Footnote 10 Much of the sugar, molasses, and rum that New England merchants brought back from their West Indies voyages were consumed throughout the New England countryside, becoming integrated into daily life in a way that further tied the two regions culturally and economically. The dynamic New England economy, which emerged out of the colonial period to lead the new nation into an era of extraordinary growth, can be attributed in part to this relationship with sugar products. Though the other global tropical groceries—tea, coffee, and chocolate—did not make widespread inroads into New England households until the eighteenth century, New Englanders’ daily dependence on sugar products developed long before the “consumer revolution” of conventional historiography.Footnote 11

The few scholarly treatments of the early New England diet do not consider the role of tropical commodities and characterize seventeenth-century foodways as monotonous, self-sufficient, and aimed at basic subsistence.Footnote 12 Nor does the rich literature on the cultural and material history of the early settlers and native peoples give sugar products appropriate attention.Footnote 13 My research, in contrast, shows that the mass consumption of sugar products on the part of seventeenth-century New Englanders impacted the trajectory of the New England and Atlantic economies.

Toward a Better Understanding of Early Modern Consumerism

Though the turn to capitalism required the emergence of a profit-seeking mentality on the part of producers, investors, shippers, and retailers, such efforts would have been futile without a robust and reliable consumer base. Any explanation of the emergence of capitalism must not only consider the scale and scope of demand but also must investigate both the nature of such demand and its potency to effect change. Such analysis has not always been present even in consumer histories, especially in the first wave of such scholarship.Footnote 14 Even while positing that an increase in demand preceded technological change and industrialization, economic historians often engage in circular reasoning, making the assumption that changes in production inevitably resulted in higher demand simply because of lower costs and wider accessibility.

Indeed, explaining changes in consumption patterns is a challenging endeavor, involving elements of both economic and cultural history informed by theories of human psychology. The relationship between capitalism and demand is complex; it is easy to forget that consumption does not intrinsically have anything to do with capitalism. Though capitalist economies, especially industrial ones, facilitate a vast increase in the number of goods in circulation, their structures cannot explain why people want things. In fact, if anything, the act of consuming stands in tension with profit-seeking, in that it immediately decreases the consumer’s wealth and thus ability to invest, as almost everything disappears or depreciates with use.Footnote 15 Yet, at the same time, one of the primary motivations for private investment is to increase one’s purchasing power. Shedding light on the nature of demand can help to untangle this web of economic behaviors.

Why did sugar, followed by other tropical groceries, calicoes, and ceramics, come to enjoy an unprecedented popularity at the beginning of the seventeenth century?Footnote 16 My study of consumer history engages with and builds on that of Jan De Vries, who formulated the influential concept of an early modern European “industrious revolution,” suggesting that, beginning in the seventeenth century, families increasingly preferred to buy commodities on the market rather than rely solely on household production, and that they altered their ratio of labor to leisure to do so. Significantly, he found that this demand for market commodities increased independent of, and often preceding, production innovations or changes in prices. And De Vries recognized that even when shifts in production did lead to price declines, these advances were not a sufficient explanation for increasing demand. Regarding tropical commodities in particular, he observed: “[B]y itself, the cost-reducing impact of commodities made possible by large-scale plantation production hardly seems sufficient to explain the European economy’s absorption of [tobacco, sugar, coffee, cocoa, and tea] in volumes that altered the daily life of broad strata of the population.”Footnote 17

De Vries offers two theoretical frameworks for understanding consumption patterns (though he does not apply these frameworks to particular commodities). First, De Vries posits a division between innate, individually referenced desires and those wants that are socially derived and reinforced. Second, he categorizes both of the above categories of consumption as either aimed at securing comfort (the reduction of physical or socioemotional “pain or discomfort”) and/or pursuing pleasure (the experience of physical sensuality or psychological novelty).Footnote 18

Consumer historians have tended to favor explanations based on socially driven aspects of comfort- or pleasure-seeking.Footnote 19 But not all commodities lend themselves easily to such interpretation. Historians of sugar consumption often vacillate between acknowledging sugar’s unique effects on human physiology and interpreting demand for it as a mostly social or cultural phenomenon. Usually this type of argument relies on a mis-periodization of sugar consumption as a trend that postdated the emergence of capitalism, so that the desire for sugar is explained solely as a cultural response to the new social mores of capitalist culture. It is this interpretation of English sugar consumption that Sidney Mintz and Woodruff D. Smith, among others, have popularized in different forms. Both Mintz and Smith, though they emphasize the agency of different groups, see sugar consumption as the result of the social and economic transitions to capitalism.Footnote 20

Such frameworks serve as a compelling revision of the notion that sugar consumption is simply a function of price; however, these arguments are themselves vulnerable to critique, grounded as they are in the assumption that all consumption consists of a form of status-seeking. The result is consumer history marred by speculation, the mistaken application of a previously developed theory of consumption to a certain behavior, and an unquestioning acceptance of the proclamations of contemporary commentators from the historical period in question.Footnote 21

Further, an overemphasis on the social meanings attached to objects and experiences can obscure the ways in which humans respond physically to the material world across cultures. Variations in culture, in material circumstances, and in personality, for example, affect how and to what extent people prioritize sugar consumption. But it is important to recognize that the culturally dependent aspects of sugar consumption are not wholly explicative in themselves, and can result in distortions in the history of English sugar consumption, derived in part from misconceptions of how people interact with sugar as a commodity.Footnote 22

My research indicates that factors such as lower prices, greater availability, or social change do little to explain sugar’s popularity in England before the development of the English sugar colonies, when prices remained high (though not prohibitively so) and work rhythms traditional. When Barbadian planters turned to sugar in the 1640s, with extraordinary success, English work patterns and social mores were not undergoing any radical transformation. This is not to say that lower prices and increased supply did not increase consumption of sugar—they did—but they did not comprise the basis for that consumption. While the sugar–slave complex did buttress the rise of capitalism—in particular, sugar’s narrow cultivation zone and its capital-intensive processing characteristics encouraged trade and market production of all kinds of surplus commodities, and the wealth it generated fostered capital accumulation and expanded the slave trade—people did not become habituated to sugar because of the cultural and economic changes brought by capitalism. I argue that the sequence was quite the reverse: it was sugar dependency that fostered capitalistic behaviors. In his analysis of consumer theory, De Vries concludes that the desire for physical comforts and pleasures can be satiated, while the yearning for social comforts and socioemotional pleasures (often cast as the relief of modern boredom) has no limit.Footnote 23 In the case of chemical substances that exert physiological effects, however, the distinction may not be as significant, at least for the early modern world.Footnote 24 Historians usually assume some degree of innate “liking” of sugar, which would predispose people to react positively to sugar but only to consume it if market forces were favorable. In fact, it is likely that the biochemical craving for sugar is powerful enough to induce a society to build an empire in order to obtain a supply.Footnote 25

The overcharacterization of sugar consumption as a cultural phenomenon has led to the following mis-periodization. A typical food history introduces sugar into Europe through “spectacular banquets organized by and for the upper classes” of the Renaissance, then takes a quick leap of two hundred years to late seventeenth-century English and French Caribbean sugar plantations whose product is alleged to explain the eighteenth-century culture of tea and dessert courses. Finally, the standard narrative reveals the extensive influence of Mintz’s work, concluding, for instance, that “starting in the nineteenth century, sugar became available to the masses, assuming for example a fundamental role in the nutritional patterns of British industrial workers.”Footnote 26 Such a summary overlooks the impact of the sizable sixteenth-century and early seventeenth-century Mediterranean sugar industry, misrepresents the extent to which sugar was woven into English foodways by 1600, and is misleading in its portrayal of cause and effect. Indeed, though historians situate the Barbadian “sugar revolution” in the seventeenth century, one could argue that the revolution began for the English as soon as they encountered the commodity some six hundred years earlier through incursions into the Middle East.Footnote 27

Significantly for the course of European imperialism, structural obstacles constrained this late medieval “sugar revolution,” preventing sugar production and consumption from passing certain levels in Europe and its periphery, despite strong demand. These obstacles included the semi-tropical Mediterranean climate, which was not reliably warm enough to ensure a good crop; deforestation and decreased soil fertility, which reduced the amount of fuel, water, and land available for production; and disruptions in the labor supply, as plagues and migrations made plantations overdependent on the local slave market.

The cap on production, and therefore consumption, was broken with the colonization of the Americas in the sixteenth century. Beginning in the Spanish Caribbean, and then much more extensively in Portuguese Brazil, sugar production exploded as the constraints of climate, land, and labor were erased. On Hispaniola and other Spanish Caribbean islands, a mix of free and slave labor increasingly gave way to African slavery over the course of the sixteenth century as the native population diminished. Sixteenth-century sugar production in the Caribbean was marked by sophisticated technology (including animal- and water-powered roller mills); large plantations worked by hundreds of slaves; and vertical integration incorporating the processing of sugarcane into sugar, molasses, and rum into the work of the plantation. Brazilians also made important technological improvements in the extraction process that significantly increased production. Sugar refineries emerged in urban areas in Europe, as fuel for processing was scarce in sugar-producing areas. Cities in Italy and the Netherlands were important refining centers as well as sources of capital and trade.

English sugar consumers were highly dependent on these Brazilian plantations, as they had been on those of the Mediterranean and Atlantic islands. Imperial rivalries, however, prevented a truly open market for sugar; imperial politics and war presented the second early modern constraint on English sugar consumption through the mid-seventeenth century, until England developed its own sugar plantations in the Caribbean. Portuguese and Dutch Brazil did export significant amounts of sugar to Europe during this period, and sugar consumption continued to grow. But the Portuguese and the Dutch vied for control over the sugar trade between Brazil and Europe in the early seventeenth century, and most Brazilian sugar continued to be funneled through Portugal. As hostilities turned to war in the 1620s, the sugar trade was severely affected. It was not until the mid-1630s that the Dutch established control over part of Brazil’s sugar region, and with it the sugar trade; but the subsequent expulsion of the Dutch from Brazil in 1646 pushed up sugar prices through the 1650s.

Twin Colonies and the North American Sugar–Slave Complex

In the sixteenth century, the plantations of the Americas built on and expanded the English market for sugar, but could not satiate it. Production increased enough so that sugar became a well-known and sought after commodity by a large segment of the English population, yet demand continued to outstrip supply. This dynamic helps explain the course of English imperialism. Beginning in the 1640s in Barbados, a tidal wave of sugar production swept through the new English (and French) Caribbean colonies, aided by the Dutch fleeing Brazil and bringing with them slaves, agricultural expertise, plantation management techniques, and perhaps capital. English Barbados, Jamaica, Nevis, Montserrat, and Antigua, along with French Martinique and Guadeloupe, all became immensely successful sugar producers in the seventeenth century. These sugar regions were the greatest supporters of the slave trade to the New World, both because of the dominance of sugar as a colonial commodity and because the brutal nature of the sugar industry required a continual influx of slaves. This forced “migration” of enslaved labor is commonly understood to be “inextricably linked” to “consumer tastes” for sugar, among other commodities.Footnote 28 The incredible, seemingly bottomless demand for sugar made it the primary engine of the English shipping industry and English colonial growth in the seventeenth century, igniting the English and Atlantic economies.Footnote 29 By 1701, sugar made up an impressive 57 percent of the value of colonial products imported into England.Footnote 30

Barbados remained the primary producer of sugar in the Caribbean during this early period; because of geographic and political obstacles, sugar did not become a major crop on other islands in the region until the 1670s. Before the emergence of Barbados as a center of sugar production, the Portuguese had produced most of the Western world’s sugar on the northeast coast of Brazil.Footnote 31 Barbados, joined in the last quarter of the century by Jamaica and the other English islands, overtook Brazil by 1700, and by this year almost half of the sugar consumed in Western Europe came from the English Caribbean.Footnote 32 Spanish and Portuguese possessions in the New World did produce considerable amounts of sugar in some areas, but England, New England, and the rest of the North American colonies traded very little with these Iberian colonies, owing to English mercantilism and Spanish hostility.Footnote 33

Slavery had existed on Barbados from the first days of settlement—among the first English group to land on Barbados were thirty-two Indians from Surinam and ten Africans, all of whom were enslaved. It was not until sugar cultivation began in the early 1640s, however, that Barbadian planters invested heavily in slaves.Footnote 34 In 1636, the Barbadian government confirmed that slavery was a lifetime condition. English indentured servants flocked to Barbados through the 1640s and 1650s (though a small number were kidnapped there, or “barbadosed”), where they worked in the fields and the mills alongside slaves. But servants often rebelled and were usually unwilling to labor for others past their term of indenture, and they were increasingly reluctant to commit to indenture at all in an industry with harsh working conditions and few prospects for ownership for those with little capital. The considerable cost savings of using slaves to avoid the high wages that otherwise would have been necessary to attract laborers to such punishing work, combined with the historical precedent of using slaves in sugar production, resulted in a rapid transition to slavery on Barbados once sugar had taken hold. Slavery allowed for significantly higher levels of sugar production, consumption, and wealth than would otherwise have been possible.Footnote 35 By the 1660s, most of Barbados’s labor force was probably enslaved. There were six thousand African slaves on Barbados in 1643, and they were, in the words of one visitor, “the life of this place”; by 1650 there were thirteen thousand, and by 1660 they constituted a majority of the population.Footnote 36

In the early 1640s, with England embroiled in civil war, New Englanders began to establish independent trade networks throughout the Atlantic world. New England’s shipping and finance industries would grow dramatically over the next few decades.Footnote 37 Massachusetts lawmakers tempered their suspicion of “shopkeeping” with legislation that secured access to “such forraine comodities as wee stand in need of.” This they mainly did by promoting and protecting potential domestic export industries, such as wheat in 1641 and pipe staves in 1646, and by investing heavily in trade themselves.Footnote 38 The Navigation Act of 1651, which forbade Barbadians to trade with their longstanding merchant partners, the Dutch, left planters casting about for investors to buy their sugar and sell them supplies. New Englanders moved quickly into this vacuum. By 1660, to the growing alarm of English officials, New England was “the Key of the Indies, without which Jamaica, Barbados, & the Carybee Islands are not able to subsist.”Footnote 39 By the 1670s, New England ships accounted for almost half of the trade with the West Indies, with the majority of New England ships originating in Boston. Between 1678 and 1684, more ships (for which there are records) arrived in Nevis, St. Christopher, and Montserrat from Boston (seventy-seven ships) than from London (sixty-four ships).

By the 1680s, over half of ships entering and leaving Boston were engaged in trade with the West Indies.Footnote 40 In 1676, English customs official Edward Randolph was forced to report that “Boston may be esteemed the mart town of the West-Indies,” providing the islands with essential supplies to feed the industrial sugar economy.Footnote 41 Another observer similarly termed Barbados a “mart,” noting that as New England was to the North American colonies, “Barbados is the Crown and Front of all the Caribbee Islands … [t]he greatest mart of trade … of any island in the West Indies.”Footnote 42 Indeed, Boston and Barbados functioned as sister communities, both serving as the economic heart of a large English territory and becoming increasingly interconnected in numerous ways.

In 1667, an imperial report noted New England’s “great trade to Barbadoes with fish and other provisions,” and a common observation of visitors to the West Indies was that “at Barbadoes they buy much Beef and Meal, and Pease, and Fish from New England.” New England was the greatest supplier of corn and meat, the sole supplier of fish and wood products, and an important supplier of horses for the mills of the island.Footnote 43 The Barbadian climate and sugar monoculture limited food production; planters depended on New England’s salt beef and pork, and their slaves survived on New England’s refuse fish.Footnote 44 As a visitor to Barbados noted in 1654, “there is no nation which feeds its slaves as badly as the English.”Footnote 45 In 1648, merchant John Pease’s shipload of over a thousand pounds of fish sailed from Boston, but “[w]hen this fish came to Barbados it proved wast by the sea wett in the voyage,” with four hundred pounds of it compromised.Footnote 46 No doubt this spoiled fish ended up as slave rations.

Beginning in the 1640s, wood from New England’s vast forests allowed Barbadian planters to build homes and production facilities, fuel the boiling houses, and package their sugar into barrels. Large commercial farms in New England, particularly in the Connecticut River Valley and in Rhode Island, produced horses and cattle for export to the islands to power the mills and work the fields. Many small family farms, too, invested in a few extra animals a year to sell for export to the West Indies.Footnote 47 If nearby New England had not worked so assiduously to gather, cultivate, and export these production inputs, Barbados’s sugar production levels would have almost certainly been lower. Planters would have been forced to devote some resources to local food production and to pay more for a less reliable supply of power and materials.

Sugar Products in the Early New England Economy

It was not only New England supplies but also New England demand that nurtured the nascent sugar industry in the West Indies.Footnote 48 Few historians have examined New England’s importance as a consumer base for sugar products during this formative period. The lack of surviving records from the years before 1688 makes it impossible to quantify the importance of the North American market for sugar products during the first few decades of English West Indies sugar production, but data from the end of the seventeenth century suggests that New England was a key partner for Barbadian sugar planters, both as consumers and as shippers of the island’s produce to the rest of the North American colonies. David Eltis has compiled the most extensive statistics on Barbados’s exports. He finds that between 1699 and 1701, 9 percent of Barbados’s exports by value went to New England. During the tumultuous decade of the Nine Years’ War, beginning in 1688, with Atlantic trade networks disrupted, New Englanders bought more than a fifth of Barbados exports by value.Footnote 49

These numbers seem modest, but their limit to the years after 1688, presentation in value instead of volume, and the lack of differentiation between types of sugar products obscure the fact that New England was an important market for molasses and rum in the first decades of sugar production, when planters were figuring out how to make their operations profitable. In fact, New Englanders, in combination with other North American colonists, were likely buying the majority of Barbados’s exports by volume, in lower value molasses and rum. The proportion of Barbados’s sugar exports to the island’s rum and molasses exports changed radically between 1660 and 1700, with these sugar by-products increasing significantly in economic importance over the second half of the seventeenth century. Eltis asserts: “After the 1660s, rum and molasses emerged as leading products in Barbados; exports of rum rose five times and of molasses ten times during the years to 1700, compared to only a one-fifth increase in muscovado exports.”Footnote 50

In the seventeenth century, there was a “distinct lack of any market” for molasses in England; John McCusker finds that the English of the mother country consumed at least twenty-five times more sugar than molasses in 1697. As for rum, in 1697 England imported a grand total of 38 gallons of it from Barbados.Footnote 51 It is challenging to find a “typical” year from the late seventeenth century, given the near constant disruption of trade by warfare; but, in 1688, the first year for which Eltis has statistics, it is startling to realize that North America took in close to half (43 percent) of Barbadian sugar products to England’s 57 percent (by value). New Englanders alone took 21 percent, and are likely responsible for shipping most of the rest up and down the North American seaboard. And considering that almost all of the island’s molasses and rum probably went to North America during this period, the majority of barrels leaving Barbados’s ports were headed for fellow English colonies rather than for England. New Englanders were likely by far the most enthusiastic Atlantic consumers of molasses and rum, and finding a market for these new consumer goods was an important support for sugar planters. This demand, combined with the region’s role as a supplier of production inputs and raw materials, establishes New England as an essential contributor to Barbados’s sugar economy. In this way, sugar products were at the forefront of New England’s “industrious revolution,” such consumers fostered slave societies in the seventeenth century by furnishing the market for sugar plantations’ products.

“To Procure Our Necessaries”

Arriving in Barbados in 1645, George Downing wrote to his cousin John Winthrop Jr. that sugar planters had “bought this yeare no lesse than a thousand Negroes; and the more they buie, the better they are able to buye, for in a yeare and halfe they will earne (with gods blessing) as much as they cost.”Footnote 52 Why were Barbadian slaves able to “earne” so much for their masters and for all those connected to the Atlantic market; that is, almost everyone, so quickly?

As outlined above, it was the long-awakened desire for sugar, among other tropical commodities, that lay at the core of the slave system. Our growing understanding, as one historian puts it, that “enslavement occurred at the hands of multiple actors,” has focused mainly on New England suppliers of investment, shipping, and raw materials to the West Indies.Footnote 53 I now turn to exploring why and how almost all New Englanders allocated their resources to ensure they could afford a store of sugar in their larders, as well as enthusiastically accepting the commodity as currency in the complex system of credit that was the foundation of the Massachusetts Bay economy.

The merchant families of Barbados and New England, recognizing the vital role that New England could play in supplying sugar plantations with food, wood products, animals, and other inputs, took advantage of the allure of sugar consumption to draw New Englanders into commercial engagement with the Atlantic economy. As the seventeenth century wore on, more and more ships ventured from New England ports laden with raw materials, often returning to Salem and Boston with holds full of sugar products in a variety of stages of processing, to be distributed not only in urban areas but also throughout the countryside. Sugar, molasses, and rum were considered essential consumer goods in all New England households, and thus took on the role of dependable forms of currency and credit. The hundreds and thousands of pounds of sugar that the richest merchants maintained in their portside warehouses and sold on the international market were only one part of the story of the sugar trade. For all citizens of Massachusetts Bay, merchants, small shopkeepers, artisans, and farmers, sugar consumption played a part in their economic decision making, and all of these actors contributed to the sugar economy.

It is a commonplace among historians that seventeenth-century New Englanders enjoyed enviable good health. A consistently plentiful and nutritious diet, along with the prioritization of such beneficial social mores as self-control and cooperation over the pursuit of individual gain, led to impressive longevity in the region, even though New Englanders had limited access to the latest technologies, medicines, and consumer goods of England and Europe. But were these self-proclaimed communitarians as immune to the attraction of consumer goods, and the markets that such goods created, as their rhetoric suggests? From his observations of New Englanders in the 1660s, traveler John Josselyn noted: “Men and Women keep their complexions, but lose their Teeth; the Women are pittifully Tooth-shaken; whether through the coldness of the climate, or by sweet-meats of which they have store.”Footnote 54 The weather was an unlikely culprit for dental maladies, tending rather to preserve New Englanders from disease; but the “store” of sugary foods that they came to depend on had far-reaching implications not only for their health but also for their culture and economy.

That sugar products were flowing into New England markets from the beginning of English sugar production in the Caribbean, and the significance of that fact for understanding colonial economic behavior and power structures, is not something that historians have fully considered for this time period. In 1650, the Massachusetts General Court wrote to England, “Wee formerly have procured Clothing and other necessaries for our families by means of some Traffique in bothe Barbadoes and some other places,” emphasizing the colony’s dependence on the Atlantic market.Footnote 55 These “necessaries” that motivated commercial production are universally assumed by historians to be English manufactures, even though during this period the word was most often used to mean the imported salt, sugar, and spices considered essential for a decent quality of life, as Sarah McMahon notes in her examination of widows’ allowances in the Massachusetts probate record.Footnote 56 This assumption that European products were the only significant consumer goods imported into New England underlies the tidy description usually offered of how the merchants of Massachusetts Bay prospered: by selling raw materials native to New England in Barbados and then taking the money, credit, or sugar products to England or English creditors to obtain English manufactures to in turn sell to the producers of New England. The reality was messier. Sugar product consumption in New England, along with the direct involvement of New Englanders in sugar production on Barbados, was an integral component of the convoluted system of trade in the seventeenth-century Atlantic world.

Supply-Side Explanations for Sugar Consumption

When John Josselyn wrote his account of his voyages to New England in 1674, he included a long list of supplies for the “intending planter” setting out for Massachusetts Bay, who would be expected to bring enough “victuals” to last his family through the voyage and the first year of settlement. He recommended that the dietary staples of grains, legumes, and oil be “carried out of England,” despite the expense of shipping them. But, as for “your Sugar,” he advised, “your best way is to buy your Sugar there, for it is cheapest.”Footnote 57 This observation underscores the high traffic in sugar between New England and the West Indies, and the competitive advantage of New England’s investors and sea captains in being a nearby provider of desperately needed raw materials to the islands.

However, it would be a mistake to assume that the popularity of sugar products in New England was a mere outgrowth of its “cheapness” relative to its cost in Europe. One reason it is important to recognize the role of New Englanders in colonizing Barbados, and in creating a market for the island’s sugar products across New England and the Atlantic world, is that historians have almost universally attributed the growth of the sugar industry and consumer market in the seventeenth century to a straightforward fall in cost. This supposition is to some extent accurate. Indeed, a contemporaneous commentator noted that “what extraordinary advantages accrue to the Inhabitants of that Island [Barbados] by means of this sweet and precious Commodity, and what satisfaction it brings to their Correspondents in other parts of the world, who have it at so easie rates.”Footnote 58 From 1650 to 1700, retail sugar prices in London fell 50 percent. The introduction of slave labor, improvements in shipping, lower interest rates for capital purchases and improvements, vertical integration, and small energy and technology innovations all increased efficiency. Added to this productivity was the enumeration of sugar in the Navigation Acts of 1660 and 1663, which rendered Europe off-limits to English sugar planters and thus flooded the English Atlantic market with English West Indian sugar. The resulting dip in sugar prices pushed planters to increase production even more and made sugar ever cheaper and more available to English and colonial consumers, who eagerly took advantage of this shift.Footnote 59

Yet the high elasticity of the demand for sugar—the market’s responsiveness to price decreases—was but one aspect of the commodity’s enormous growth. It does not in itself explain the rise of the seventeenth-century sugar industry and the trade networks and settlement patterns that supported it. English demand for sugar long predated high production and low prices. Barbadians themselves were importing sugar before its settlers learned how to grow it. When Barbadian settler Thomas Verney wrote to his parents in 1639 asking them to send him essential supplies, he included a request for “tenn pound of suger,” a commodity to which he and his fellow planters were already habituated.Footnote 60 And at least before 1655, the English demand for sugar, both in the mother country and its colonies, was in no way the result of falling prices. English colonists, including New Englanders, launched the sugar industry on Barbados as world sugar prices were about to rise, and built it up with prices remaining high—sugar prices rose between 1646 and 1654 because of the enormous disruption in Brazilian sugar production caused by the Dutch invasion of the region.Footnote 61 Nor were high prices in themselves what motivated English settlers to shift to planting sugar in Barbados 1640 and 1643, when the switch to sugar occurred, sugar prices actually fell by a third.Footnote 62

In short, despite short-term variability, sugar prices in England and the American colonies did not change dramatically before 1660. Before the rise of the English sugar industry on Barbados, sugar cost about 1s. 2d. a pound in England and the North American colonies; after the sugar plantations were well established, by the end of the 1640s, prices fell to about 8d. a pound. My analysis of colonial account books indicates that prices fluctuated along this 6d. gap throughout the 1650s, even while demand remained strong—and growing—for sugar, and increasingly for molasses and rum.

Thus, attributing demand simply to such structural factors as price or the availability of labor obscures the underlying reason for the success of the sugar–slave complex: the interest of a network of English colonists in securing a source of sugar products. This interest was so deeply embedded in the colonists’ foodways that it altered the trajectory of the Atlantic economy. Of course, it is impossible to untangle the taste for sugar from the drive for power. Since the English desire for sugar was so strong, whoever had a hand in controlling the production and distribution of the commodity would have global influence. This fact was hardly lost on all colonial actors, from the imperial government to the New England puritan elite to the tens of thousands of settlers that ate, bought, sold, traded, and processed West Indies sugar.

Assessing Sugar Product Consumption in Early New England

By 1650, the three thousand settler families of Massachusetts Bay—about fifteen thousand people—had begun to produce foodstuffs and other raw materials for export.Footnote 63 The need to afford imports, necessitating the production of market commodities for export, drew individuals, families, towns, and the entire region into a commercial economy. Thus arose a multifaceted economic system, directed at assembling commodities from across the countryside for export and distributing imported goods to the colonists now able to purchase them with their labor, skilled craft production, or surplus agricultural products. The economy of Massachusetts Bay was arguably the most complex of all the northern Atlantic English colonies in the seventeenth century. Capital accumulation, labor organization, financial services, shipping industries, and reliable distribution networks were all phenomena that emerged as a result of the consumer interests of English settlers.Footnote 64

Historians have exclusively focused on English manufactures as the central component of this consumer economy. But sugar products were also significant. A close examination of merchants’ account books and other sources reveal that the majority of consumers consistently purchased sugar in modest amounts in the 1650s; then, between 1657 and 1663, sugar, molasses, and rum rapidly became items of mass consumption for a large sector of the population. A key expansion in Massachusetts sugar, molasses, and rum consumption took place between 1650 and 1670, as merchants and retailers, driven by the popularity of sugar among English settlers, and working in concert with relatives and friends developing sugar plantations on Barbados, supplied local markets with the island’s sugar. Sugar consumption was one of the few puritan material indulgences. Rather than condemned as a crippling dependency or worldly luxury, sugar was recognized as a “necessary.”

Until now, no historian has attempted an estimate of sugar product consumption in New England in the seventeenth century. Carole Shammas, the foremost historian of early English and American consumption, attests that “the year by year trend in the consumption of sugar products by Americans is not known.”Footnote 65 Similarly, historians have paid little attention to the details of seventeenth-century rum consumption. Scholars of the eighteenth century have found New Englanders’ molasses and rum consumption simply astounding, a social phenomenon as well as an important economic “vent” for by-products of island sugar production. I locate the beginnings of this market in the dealings of seventeenth-century merchants, retailers, and customers, tracing a change in economic engagement away from localism and toward interaction with and dependence on the Caribbean.Footnote 66

My research shows that historians’ typical portrayal of New England’s material culture as austere and production-oriented, resting on the assumption that participation in Atlantic markets was purely a reaction to a need for currency and credit to buy English “necessaries” such as nails and textiles, overlooks the relationship between New England consumers and West Indies commodities. Seventeenth-century economic records are scattered and incomplete but highly informative when brought together. I use several detailed account books, along with court and probate records, government documents, and narrative sources, to evaluate the extent of sugar product consumption in Massachusetts Bay from the mid-seventeenth century onward. Tracking this consumption allows us to better understand New Englanders’ economic choices and their enthusiastic engagement with the development of Barbados as well as the rise of the incredibly profitable and politically significant rum and molasses trades by the dawn of the eighteenth century.

Probate Record Evidence

Those with enough resources to invest in trading ventures, or to do business with those investors, were the first on the New England side of the commodity chain to control the sugar supply. These were not only the leading merchant families of Massachusetts Bay; often they were people with minimal assets and only a few dealings in imports. Average families not uncommonly took possession of barrels of sugar at a time, and it was from these barrels that sugar flowed into the households of Massachusetts Bay in the 1640s and 1650s. Massachusetts Bay’s major counties—Essex, Middlesex, and Suffolk—were largely rural, but each was anchored by one bustling port (Salem, Charlestown, and Boston, respectively). Those men dealing directly with Atlantic trade tended to be concentrated in these towns, but each had connections to middlemen and farm families in the smaller villages spread over the countryside.

Robert Long of Charlestown was among the first to take a risk on the earliest sugar crops of Barbados. He died in Barbados in 1648, probably on a trading venture, leaving three butts of sugar valued at £60 (as well as an equal amount of sugar still in Barbados, and about three hundred pounds of sugar in his storeroom).Footnote 67 Such large holdings of sugar were a common investment in mid-seventeenth-century Massachusetts, not only for merchants whose primary vocation was shipping and trade but also for anyone with enough resources. Those who were able to access the new areas of production in Barbados, or who knew someone who could, seized on a commodity that they knew would find a ready market all across Massachusetts Bay, from wealthy households in the port towns to modest farm families in the hinterlands.

Cambridge resident William Wilcox, for example, was trading with Barbados in the early 1650s; he had dealings with several planters on the island, and in 1653 owned four hogsheads of sugar valued at £40.Footnote 68 William Clarke was a Salem innkeeper, kept an ordinary in the village in the 1640s, and probably sold sugar in some form at his establishment. He died in 1647, leaving parts of three hogsheads of sugar worth £26.Footnote 69 Nicolas Guy, a Watertown carpenter plying his trade in the 1640s, was not a particularly wealthy man, running a modest farm and shop assessed at £112. Guy put his additional capital into sugar intended for local sale: £50 worth of sugar of varying quality: one barrel of white sugar, one barrel of “Muskevadoes,” and three hogsheads of muscovado sugar of another grade. Edward Goffe, of Cambridge, in contrast, was prosperous, with land holdings worth in excess of £600, and had small dealings in imports. He held a considerable amount of sugar at his death: 300 pounds, likely muscovado, as its value indicates that its wholesale worth may have been as low as 4 to 5 d. per pound. In 1650, Edward Mellows, of Charlestown, “adventured with Mr. Foster; Mr. Marifeld; Thomas Croe, Mr. Parris, Jno. Founell,” and had in storage ten pounds of sugar among other spices.Footnote 70 Ralph Mousall was a prominent resident of Charlestown, but his primary work was as a carpenter, not a merchant. In 1657 he owned a hogshead (about 300 pounds) of sugar worth £10. The wholesale supply of sugar in Massachusetts Bay included such varied investments in sugar, from a small investor’s share of a few pounds out of a larger shipment, to a carpenter’s purchase of a barrel of fine white sugar, to a merchant’s hogsheads of cheaper muscovado. All these stores were probably intended for “resale” in small amounts, mainly in the form of barter and satisfaction of creditors.Footnote 71

This sugar trickled through the economy, ending up on the tables of villagers who could not afford to invest in large quantities of sugar directly. The wealthy tended to stock larger amounts of sugar in their storerooms, but even subsistence farmers allocated resources to incorporating sugar into their diet, and estate appraisers did sometimes note these small amounts. Sugar probably moved often in small amounts between households; unwilling to do without it, families went into debt to each other to secure it as a “necessary.” Most of these exchanges went unrecorded in the system of local credit, but some were noted in the legal record. When Joanna Cummings of Salem made her will in 1644, for example, she carefully listed her debts, including one to a Mrs. Goose for a pound of sugar.Footnote 72

Sugar’s status as a restorative health food made it particularly common in the diet of the ill, and as such sometimes appeared as a final expense in probate records. This pattern emerges more often for the very poor than for anyone else (revealing the depth of sugar consumption across income) because single male boarders nursed by caretakers rather than family were billed for their board after their deaths. Edward Candall, of Salem, died in 1646 with an estate of only £2 11s., but his appraisers noted that he had owed 2s. 4d. to local merchant Mr. Price for sugar.Footnote 73 Gunsmith William Plasse had to his name only a featherbed, two pillows, a Bible, a book of psalms, an old chest, his tools, and five pounds owed to him in wages from Salem town when he died in 1646 at the home of Thomas Wickes in Salem, where he had been boarding. A poor man, though perhaps valued for his skills, Plasse nonetheless was nourished with sugar during his final illness. His caretaker drew up a bill for costs incurred “in his sickness,” which in addition to meat and bread included 4s. 9d. on sugar (almost as much as the caretaker, Wickes, spent on meat, and far more than on bread, eggs, or any other item).Footnote 74

Well-off families, unsurprisingly, also left evidence of sugar consumption. Their larger stores of sugar may have been intended for barter with neighbors as well as personal use, but much of it was likely consumed by the family. George Williams, a prosperous cooper of Salem, died in 1654 with, among his considerable possessions “14 li. of white suger, 14 s,” likely standard fare for his busy household of seven children.Footnote 75 Francis Parrot, a farmer and town clerk of rural Rowley, died in 1655 leaving a hogshead of sugar “of uncertain value.”Footnote 76 Rear-Admiral Thomas Graves, who was instrumental in organizing shiploads of migrants to the new colony, died a wealthy man with many luxury goods, including 24 sugar loaves worth £8 8s., presumably for personal use given his lavish lifestyle.Footnote 77 Sugar consumption was well enough established in Massachusetts to support a market for sugar paraphernalia, such as the “suger box of tin” that Samuel Andrews, of Charlestown, possessed in 1659, and the “sugar dish” owned by Thomas Shepard, the wealthy pastor of the Cambridge church.Footnote 78

Sugar appears just as frequently in inventories of humble estates, in varying, and sometimes surprisingly large, amounts. Modest widow Alice Ward, of Ipswich, had assets of only £37 in 1654, but that included £4 3s. in sugar, an impressive hoard of about 125 pounds.Footnote 79 Farmer Hugh Laskin left a “pott” containing about 280 pounds of sugar, valued at £9 6s., when he died in 1659, though his total estate, assessed at £58, included only basic clothing and furnishings, and his stored provisions mainly consisted of “9 pecks of Wheat eaten with Weevells” and “3 Bushells of Indian Corne eaten with Weevells.”Footnote 80

Some of these substantial stockpiles of sugar, perhaps obtained through contacts with merchants and intended for resale, probably found their way to friends and neighbors who bought only what they needed for family consumption. One of these was John Perkins Jr., of Ipswich, a small farmer with a wife, “one young child, new born,” and £73 to his name, who had in his larder “3 poringers and 6 pound of suger, 8 s. 6 d.” in 1659.Footnote 81 When John Bibbell died in Malden in 1653, he left behind a decently provisioned home, if only with tools and the most basic of furnishings. But he did have about 16 pounds of “suger in petter mud’s hands” promised to him and valued at 11 shillings.Footnote 82 William Bucke, of Cambridge, was a poor man; when he died in 1658, his estate was worth only £26, and he was £5 in debt. His only possessions were the most basic of tools, a bed, one set of clothes, and two pairs of shoes. Yet he chose to spend his limited resources on sugar; his stored foodstuffs consisted of “sugar and bacon Cheese and butter porke,” worth all together 10 shillings.Footnote 83

Account Book Evidence

Probate records alone offer only compelling hints that sugar was an integral component of the culture and economy of mid-seventeenth-century Massachusetts Bay. The small amounts of sugar that sometimes appear in the estates of modest farmers and artisans are the exception rather than the rule. Indeed, a cursory examination of the probate record might leave the historian with the impression that sugar was a rare indulgence among the people of Massachusetts Bay. This was not because sugar was uncommon but rather because assessors only very irregularly recorded small amounts of foodstuffs intended for the family’s personal use.Footnote 84 Abraham Warren, for example, did not leave any record of sugar consumption in his probate. He died very poor in 1689 and would not have appeared to be a likely purchaser of tropical imports except, because of the survival of a Massachusetts Bay shopkeeper’s account book from the 1650s, we can establish that he did buy sugar as early as 1653.Footnote 85

Such account books serve as snapshots of the commodities moving through the colony’s economy in its earliest years. My analysis of hundreds of purchases recorded in several shopkeepers’ account books from the period, primarily those of George Corwin, of Salem; John Pynchon, of Springfield; and Robert Gibbs, of Boston, exposes patterns of sugar, molasses, and rum distribution and consumption in the Massachusetts Bay colony between 1650 and 1670, just as settlers in Barbados were successfully establishing large-scale sugar production.

Even before Barbadian sugar products reached the Atlantic market, sugar was probably a stock item the in the rudimentary shops of Massachusetts Bay. Joseph Weld, for example, had 40 pounds of sugar in his Roxbury shop as early as 1647, which he was selling for 10 shillings a pound.Footnote 86 The merchants of mid-seventeenth-century Massachusetts Bay were often small shopkeepers as well as international investors. It was common for men of some resources to organize and invest in fishing and trading ventures to Barbados and other Atlantic destinations but to expend most of their economic energy bartering with local families, largely collecting local products in exchange for the imports to which they had more access than most settlers.Footnote 87

One of these entrepreneurs was landed gentleman and puritan sympathizer George Corwin, who sailed to Massachusetts with his wife, Elizabeth, in 1638. He became a successful shipbuilder, merchant, and shopkeeper in Salem, financing and operating trading ventures to England, Europe, and the Caribbean as well as rendering foreign commodities accessible to residents of the rural inland region of Essex County through his general store. His son, Jonathan Corwin, born in 1640, continued to build the mercantile business. In 1675, Jonathan married Elizabeth Sheafe Gibbs, widow of Robert Gibbs. This marriage united two mercantile families with roots both in Massachusetts and Barbados. Robert Gibbs, who had emigrated to Boston about 1658, was a Boston merchant who, like Corwin, operated a general store, catering to rural as well as urban customers. Like so many other New England families, Gibbs had relatives in Barbados, and he worked closely with these connections to develop the economies of the two colonies.Footnote 88

Seventeenth-century account books used single-entry accounting, organizing accounts by person rather than by credits and debits, and tracing the balance of credit and debt in single or double columns within each person’s entry.Footnote 89 To complicate matters, third parties were often drawn into an exchange if they had a commodity that would facilitate the exchange, or if they paid off their debt to one person by settling that person’s debt to a third, or both. Because of the scarcity of English money in seventeenth-century New England, people were rarely able to pay for goods at the time of purchase, whether retailers buying from wholesalers or consumers buying from retailers. Prices and payments were calculated in pounds, shillings, and pence, but these units of currency were largely imaginary and used to compare debts rather than reflecting actual coins in circulation.

Though buyers could pay more readily in commodities, and often ended up doing so, they frequently did not have on hand the particular goods that the seller wanted. As a result, credit was the basis of the colonial economy, and the fact that even small farmers and shopkeepers who dealt almost exclusively with friends and neighbors in their communities kept detailed records should not be surprising. Account books were not used to calculate profit or strategize but rather to track indebtedness in an elaborate network of credit. It was the only way people could hope to participate in markets at all. This system of “bookkeeping barter” has left us a few surviving account books from even the earliest days of the Massachusetts Bay colony, and the books’ use of commodities rather than currency to make payments allows historians a comprehensive analysis of production and consumption within the colony.Footnote 90

George Corwin’s earliest record book, beginning in 1651, is a series of small accounts with well over a hundred people, who mostly paid him in “country pay.” The accounts extend over long periods of time, an average of a year and a half. Overall, 42 percent of people paid Corwin in meat or livestock, 47 percent in grain, 28 percent in dairy, and 19 percent in raw products for beer-making or finished beer.Footnote 91 The commodities that colonists most frequently sought at Corwin’s store were tobacco, textiles, nails, soap, and brandy. In the early to mid-1650s, most people infrequently but consistently bought sugar (molasses and rum appear to have been as yet unavailable). Corwin’s customers tended to make a series of small sugar purchases over the course of a year, typically one to five pounds at a time.

It is not surprising that scholars have not recognized the significance of these sugar sales, because they were not as common as those of some other imports and they often consisted of only small amounts. Further obscuring the extent of the market for sugar in the colony is the illegibility of a large percentage of account book entries, which problematizes the study of any commodity other than the few most popular; also, of course, the dearth of surviving account books makes comprehensive studies impossible. When one of Corwin’s customers makes only one or two sugar purchases in a year, it is difficult to know if those purchases represent all of the sugar his family consumed, or if other sugar consumption lies hidden in the illegible sections of the account books, or if the customer was also buying sugar from other shopkeepers whose records have not survived. It is reasonable to assume that the sixty-one people whose accounts are legible enough to reveal that they bought sugar from Corwin 107 times over a four-year period from 1651 to 1655 represent only a tiny fraction both of the Bay colony’s sugar consumption over that period and of the commercial production put in place to enable that consumption.Footnote 92

As indicated by the probate record, some of Corwin’s customers bought large amounts of sugar at a time with the intention of reselling it to the broader community, either in the same form or processed in some way. The village tavern was one such distribution point. Though the puritan leadership disapproved of excessive drinking, taverns served as community centers where neighbors and strangers encountered each other, took in the news from near and far, and processed that information together. Relatively large buildings that could accommodate and nourish travelers in every season at all times of day and night, taverns naturally served as official meeting places for the Boston courts and the town circuit courts; it was too expensive and inconvenient to maintain courts at the meetinghouses. Officials in Boston and other towns also used taverns for official government functions on a regular basis. In addition, taverns were a place where “popular” or “traditional” English culture, which embraced “immediate gratification,” thrived and challenged puritan idealism.Footnote 93

When innkeepers served sugary drinks or offered pieces of sugar for a penny, it was to the entire spectrum of Massachusetts Bay society. “In Boston,” noted John Josselyn in 1671, “I have had an Ale-quart spic’d and sweetned with Sugar for a groat,” a practice that put sweetness within the daily reach of consumers.Footnote 94 One of George Corwin’s earliest and most frequent customers was John Gedney, a selectman and leader in the community, who had been an innkeeper in Salem since 1639, and who owned the reputable Ship Tavern in the 1650s. Between 1651 and 1653, Gedney bought large amounts of sugar from Corwin on five separate occasions, once about 30 pounds, once about 60 pounds, and once half a hogshead.Footnote 95 William Clarke, the Salem innkeeper who passed away in 1647 with a stock of 700 pounds of sugar, died before the start of Corwin’s surviving account book from the 1650s, but his probate record is also evidence of sugar distribution through ordinaries, inns, and taverns as early as the 1640s; very likely he had purchased sugar from Corwin as well. His sugar stockpile reflects the continuation of the longstanding English custom of consuming sugar mixed with alcohol.

Throughout the Bay colony, both townspeople and rural villagers sought out sugar products by frequenting the port town shops owned by prosperous shopkeeper-merchants with Atlantic connections and the extensive network of small taverns. At the same time that George Corwin was distributing sugar in Salem and surrounding settlements, at the other end of colony, in remote western Springfield on the Connecticut River, the accounts of merchant John Pynchon reveal remarkably similar patterns of demand and supply.

William Pynchon, John’s father, had come from a comfortable gentry family in Essex. He was a devout puritan who shared the spiritual intensity of many of the early settlers, and there was a close relationship between his family and that of the Reverend John White. Pynchon was one of the early organizers and leaders of the Massachusetts Bay Company in England and assisted in governing the colony after he arrived in 1630, settling initially in Roxbury. He soon became involved in the Indian fur trade, and in 1636, unhappy with land policies in Roxbury and seeking better access to that trade, he founded a settlement on the Connecticut River (first called Agawam, then Springfield), one of several English settlements that were established in the region around that time. The Massachusetts General Court gave him considerable political authority, and he quickly came to control the fur trade and the general economy over an extensive area in the western part of the colony. Traders dealing with Indians had to be licensed, which Pynchon was, and he was probably the only trader in certain areas north of Springfield. For a brief period at mid-century, fur exports to England and Europe proved lucrative, making the Pynchon fortune.Footnote 96

Through the wealth brought by this trade, Pynchon was able to buy manufactured goods from England, as well as tropical commodities, for sale to the people of western Massachusetts. Pynchon’s general store was the center of economic exchange in Springfield, as Pynchon served as a creditor, landlord, or employer to much of the town. Around 1651, the business passed to John Pynchon, who would continue to control the flow of commodities in and out of the Springfield area. Farmers and artisans traded farm products and labor for purchases from Pynchon’s warehouse.Footnote 97 After the mid-1650s, as local furs became scarce and competition from Dutch traders increased, Pynchon found a new type of export and a new destination: agricultural commodities and the West Indies. Because of Pynchon’s political and economic power over local farmers and tradespeople, historians have assumed that the general population was forced into commercial farming in order to pay rents to him and to buy the English manufactures necessary for survival on the frontier.Footnote 98 The pattern of sugar purchases, however, indicates that farmers may have been making more complex decisions about their consumption. These settlers may have, in some measure, labored freely in order to experience the sensory pleasures of sugar.

One early example of the power of sugar consumption to shape behavior on the frontier does not directly involve the Pynchon family. In 1650, western settler Nathaniel Browne had run up such an outstanding bill for imported foodstuffs, including raisins, thirty pounds of sugar, vinegar, wine, and cakes, that his creditor, Walter Fyler, took him to court. This unusual persecution, in a time when debts typically were allowed to extend for years without incurring legal action, leaves us with evidence in the court record of consumption patterns that probably characterized other households as well. Nathaniel had come from a gentry background in England and was likely habituated to a diet sweetened with sugar. As we have seen, sugar consumption was the norm among the middle class in early seventeenth-century England, and the settlers of Massachusetts Bay brought that habit with them. When Nathaniel found himself on the New England frontier with limited resources, he was not able to reconcile his cravings with his new economic reality, and he sacrificed financial stability to indulge his appetite.Footnote 99

John Pynchon’s accounts and personal papers show that sugar flowed up and down the Connecticut River in the mid-seventeenth century. His records of sugar distribution reveal that, in the early 1650s, he likely was still struggling to secure a consistent supply of the commodity, as he worked to support the nascent sugar industry in Barbados by setting up a reliable trade with the island. The desirability of sugar and its relative scarcity meant it was often exchanged between family members and friends as a way of cementing social bonds. Satisfying another’s craving for sugar, and in turn having one’s cravings satisfied, admitted a vulnerability that brought allies and loved ones closer together. Stopping in Hartford, Connecticut, in 1654, Pynchon sent John Winthrop Jr., then living in the coastal town of Pequot, a firkin (about fifty pounds) of sugar and some red rose conserves.Footnote 100 Gifts of sugar tended to flow in both directions, depending on who had a surplus; in 1656, it was Pynchon who was the recipient of a present of sugar from the Winthrops.Footnote 101

Pynchon’s accounts with residents of the greater Springfield area have many commonalities with those of George Corwin. As in Essex County, people on the frontier bought affordable amounts of sugar multiple times over the course of a year. Sugar seems to have been even more sought after in the Springfield area than in the hinterlands of Salem, as each customer of Pynchon’s averaged more sugar purchases than did Corwin’s, though this may in part reflect the greater market share of Pynchon’s frontier establishment. Though customers sometimes also bought vinegar, salt, spices, tobacco, and brandy, sugar was by far the most sought-after food. Approximately fifty people bought sugar from Pynchon over a two-year period, from 1653 to 1655, as recorded in the legible sections of his account book, at a price ranging between 8d. and 1s. 2d. a pound.

Legibility is an even greater problem with Pynchon’s account book than it is for Corwin’s, as the former tended to cross out closed accounts, and sections of many accounts are unreadable (Figure 1). Thus we can assume that there were more sugar consumers and more purchases per consumer than can be recovered from the legible section of the account book. Though data limitations preclude a comprehensive analysis of sugar consumption in the region, a minimum level of consumption can be established.Footnote 102 Sugar purchases also tended to cluster strikingly within each person’s account, indicating that sugar may have been only sporadically available as Pynchon’s shiploads of goods made it up the river to Springfield. Settlers Thomas Stebbins, Thomas Miller, and Henry Burt, among many others, bought sugar in clusters once or twice a year during the 1650s, with each cluster making up three to six purchases of two to six pounds each. It seems that when a shipment of sugar did arrive, consumers moved quickly to buy it before supplies ran out, but that they preferred to buy it in several smaller amounts rather than in one large purchase, perhaps because their resources were limited.Footnote 103

Figure 1. Page from John Pynchon’s Account Book, 1666, account with William Branch. (Source: John Pynchon, Account Books and Other Records, 1651–1697, microfilm.)

Doubtless other men with shipping connections also served as distributors of tropical commodities in isolated areas where shopkeepers were scarce. In 1649, John Winthrop Jr., who was establishing the frontier settlement of Pequot in Connecticut at the time, received a barrel of sugar from his brother Adam in Boston. This shipment was not a gift but rather a request that John serve as retailer, for Adam asked that John weigh it and pay him 10d. a pound “or else lett the market sett the prise.” Adam’s reference to the market makes it clear that John would distribute the sugar in the new settlement rather than keep it for personal consumption. John seems to have had multiple sources of sugar to supply his new settlement; that same summer he bought twenty-two pounds of sugar from John Clark in Saybrook, for £1 9s. 4d.Footnote 104 In addition, because of the strength of the local market for sugar, Massachusetts Bay residents also frequently used it as currency. In 1655 John Trumbull bought much of the estate of the deceased Captain Augustine Walker for “seventy pounds in shugers att fifty shill. the hundred.”Footnote 105 Similarly, Thomas Macy paid a debt in 1653 with one hogshead of sugar and four cows.Footnote 106

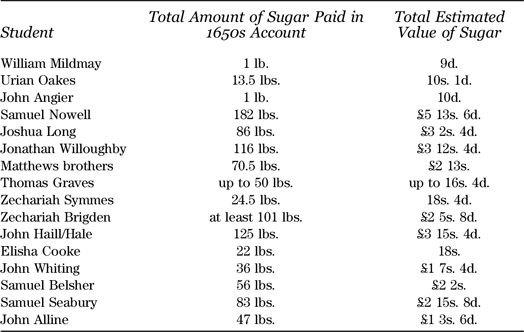

This type of transaction was common, but one of the most striking examples of sugar’s importance as currency in this early period of the Bay colony’s economy are the well-preserved records of the Harvard College steward, who was responsible for collecting tuition and room and board payments from Harvard students four times a year, settling the accounts, and managing the finances of the College’s kitchen. Sugar played an impressive role both as a currency - the college accepted it as payment, knowing that settlers’ unwavering demand for sugar meant that it could easily be used in turn to cover the college’s debts - and as a stock item in the kitchen, distributed back to the students in the form of meals.

The students of Harvard College in the 1650s were disproportionately from gentry families, particularly families of ministers. However, college fees were low and within many farm families’ means; a bushel and a half of wheat, for example, was enough to pay for a quarter’s tuition. The General Court ensured that some scholarships were given as well, and students came from a variety of backgrounds.Footnote 107 Regardless of their financial position, families of Harvard students rarely could pay their fees entirely or even mostly in money, and in recognition of this the college asked for payment in “Wheat or Malt, or in such provision as shall satisfy the Steward for the time being, & Supply the necessityes of the Colledge.”Footnote 108 The steward indeed used much of the food sent in payment to “Supply the necessityes” of the students’ diet, thus limiting the amount of provisions he needed to buy on the market. Beer, beef, mutton, or pork; bread, pottage, or porridge made from the malt; and the wheat, rye, oats, and corn of “country pay” made up the core of breakfast, dinner, and supper. The kitchen must have served some vegetables, though student contributions were largely limited to apples and “pease.” Though simple, dishes were not bland, as the steward regularly obtained salt, pepper, and herbs.Footnote 109

But this limited diet was made greatly more stimulating by sugar, clearly deemed a “necessitye” if one considers the college’s acceptance of it as currency; it was one of the top six commodities that students used as payment in the 1650s, along with wheat, rye, corn, beef, and pork.Footnote 110 Between 1650 and 1656, sixteen students paid their tuition or room and board in sugar, many of them multiple times. Sugar averaged about 9d. a pound in 1650s Massachusetts Bay, and a year of Harvard’s tuition cost thirty-five to forty-three pounds of sugar.Footnote 111

The sheer volume of sugar flowing into the steward’s storerooms indicates that Harvard students enjoyed sweet foods as part of their regular diet. As Samuel Morison, noted historian of the college, notes, “in some manner the Steward must have used up the considerable quantity of sugar paid in by students.Footnote 112 Some entries clearly indicate that the steward intended the sugar for consumption at the college, as with the payment he accepted from William Mildmay in 1650 in the form of “suger for the ketchen.”Footnote 113 Though college rules forbade immoderation in clothing, mandating a “modest and sober habit” and forbidding “all lavish Dresse, or excesse of Apparell,” as well as all tobacco and “inebriating Drinke,” indulgence in sweets was another matter.Footnote 114 A separate account records the steward’s further purchases of sugar when his supplies were exhausted. Between 1656 and 1659, he bought sugar fourteen times, presumably when the sugar paid by students had run out.Footnote 115 The steward’s records, offering a unique glimpse of early colonial eating habits, show that sugar was not considered an “indulgence” at all. As future political leaders, students would prioritize maintaining the colony’s sugar supply based on their personal habituation to the commodity as part of their accustomed diet.