We live in societies that may be politically democratic but are socially fascist, which is more than ever the ideal regime for global neoliberalism. But this duality creates instability. Will the future be more democratic or, to the contrary, will fascism move from a social to a political regime? It will depend on us. Each generation fights with the weapons it has.Footnote 1

Democracies are dying democratically.Footnote 2

Introduction

Democracy is generally understood and discussed as operating within a state and applying to those people within the procedural grasp and coercive power of the state.Footnote 3 From this view, the democratic determinants are who gets heard both formally (i.e. through votes, representative government, and legal and civic administration) and informally (i.e. media voices and spaces, economic participation and class, and education privileges).Footnote 4 How might we conceive of democracy within nonstate societies such as historic Indigenous societies? How would it operate and what would its determinants be?

Within what has been described as the deepest crisis of liberal democracy since the 1930s, I want to take up and explore some of the current challenges to democratic governance from an Indigenous perspective and from within a historic nonstate political ordering of Indigenous societies. How is the global democratic crisis being experienced in Indigenous communities, and how might Indigenous insights and responses, so sorely needed, invigorate larger conversations about liberal democracy? One of my aims here is to examine several worries that I have about what appears to be a general lack of critical analysis and inattention to serious questions concerning Indigenous democracies, governance, and citizenship.

One of my worries is the deficit approach being applied to Indigenous peoples and societies. The assumption driving this impoverished approach is that Indigenous societies were never democratic and, further, that historically and to the present day, Indigenous societies violate human rightsFootnote 5 through the operations of their political ordering, economies, and legal orders and law. These so-called deficits provide the justification for further impositions of state democratic constructs which create more hammers to force the reshaping of Indigenous democracies and citizenries into acceptable colonial forms. The process and effect of this deficit approach creates what de Sousa Santos has called abyssal thinking, wherein one imaginary operates to exhaust all other possibilities, thereby rendering those other possibilities invisible.Footnote 6

My other related worry is created by the persistent idealization and romanticization of Indigenous practices based on the assumption that there is no need to be critical of either historic or present-day Indigenous politics, law, and economies. In their efforts to be supportive of Indigenous peoples, some Indigenous and non-Indigenous academics take the position that they cannot acknowledge or discuss Indigenous sexism, internal oppressive power dynamics, or other political dysfunctions lest they further undermine Indigenous peoples and perpetuate colonial oppression. The reality is that today there are some Indigenous communities that are dangerous for women and girls because they are absolutely shameless in their sexism,Footnote 7 and there are extensive local conflicts within and between communities.Footnote 8 When historic problems are denied in Indigenous societies, and when present-day problems are blamed entirely on colonialism, the consequence is the erasure of historic Indigenous intellectual resources, resiliencies, and processes that might be drawn upon today.

I have three overarching objectives in this chapter. First, I want to demonstrate how current negotiations between GitxsanFootnote 9 communities and the Canadian (i.e. federal and provincial) governments are a form of abyssal thinking, and as such operate to further undermine Gitxsan democracy and governance. To support this argument, I draw on the work of Boaventura de Sousa Santos and his analysis regarding modern western thinking in the global struggle for social justice.Footnote 10 While I am focusing on the Gitxsan to avoid pan-Indigeniety and to allow a deeper analysis, this discussion may be extrapolated more broadly to apply to other Indigenous peoples.

Second, I want to examine one exemplar of Indigenous democracy: that of the historic and present-day Gitxsan society from northwest British Columbia. My basic contention is that, while not perfect, historic Gitxsan democracy is an example of intense democracy, a far more politically inclusive form of governance than the current model of what is perhaps the worst form of representative democracy imposed through colonization with the federal Indian Act.Footnote 11

Finally, I want to apply Kirsten Rundle’s articulation of Lon Fuller’s legalities and relationships to Gitxsan governance in order to expand and develop other ways of thinking about and restating law and governances in Gitxsan society and, by extrapolation, in other Indigenous societies.Footnote 12 My intention here is to create another method, and an accompanying grammar, with which to analyze contemporary forms of Indigenous governance and some of the arising issues.

Canadian Abyssal Thinking

Modern Western thinking is abyssal thinking. It consists of a system of visible and invisible distinction, the invisible ones being the foundation of the visible ones. The invisible distinctions are established through radical lines that divide social reality into two realms, the realm of “this side of the line” and the realm of the “other side of the line”. The division is such that “the other side of the line” vanishes …

What fundamentally characterizes abyssal thinking is thus the impossibility of the co-presence of the two sides of the line. To the extent that it prevails, this side of the line only prevails by exhausting the field of relevant reality. Beyond it, there is only nonexistence, invisibility, non-dialectical absence.Footnote 13

In 2019, a northern Gitxsan group invited me to attend one of their negotiating meetings with federal and provincial negotiators.Footnote 14 Rather than taking the usual course of litigating for a declaration of Aboriginal title from a Canadian court, these Gitxsan were instead negotiating for a declaration of their Aboriginal title over their historical lands with the provincial and federal governments.Footnote 15 My role was to describe Gitxsan law and political ordering, how it worked, and how it constituted a valid form of democracy. Within this conceptualization of democracy, specifically Gitxsan democracy, “Citizenship is not a status given by the institutions of the modern constitutional state and international law, but negotiated practices in which one becomes a citizen through participation.”Footnote 16

This Gitxsan group was comprised of representatives from their own historic political and legal system rather than the band council as set up under the Indian Act.Footnote 17 Hence, these Gitxsan people were the chiefs, wing chiefs, and members of the historic Gitxsan matrilineal kinship groups, the huwilp,Footnote 18 commonly known in English as the House.Footnote 19 I will expand further on Gitxsan political and legal ordering, and its operation in what follows.

The problem was that the federal and provincial negotiators were having great difficulty seeing and comprehending Gitxsan democracy as legitimate political and legal forms of ordering. Instead, the federal and provincial negotiators expressed concern about what they perceived as the lack or deficit of Gitxsan democracy because Gitxsan people did not hold elections to vote for their House chiefs or wing chiefs – past or present. What they failed to see was a society that Richard Overstall describes as being formed by threads of kinship and threads of contract which “weave a complex legal and social fabric.”Footnote 20 Gitxsan law and political ordering constitute and are constituted by these threads, the warp and woof, the fundamental structure of Gitxsan society. Ralph Waldo Emerson has aptly and beautifully commented that the “Old and new make the warp and woof of every moment. There is no thread that is not a twist of these two strands.”Footnote 21

According to the federal and provincial negotiators, this absence of elections and voting in Gitxsan society violated the democratic rights of Canadian citizens under the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms,Footnote 22 specifically the following:

3. Every citizen of Canada has the right to vote in an election of members of the House of Commons or of a legislative assembly and to be qualified for membership therein.

4. (1) No House of Commons and no legislative assembly shall continue for longer than five years from the date fixed for the return of the writs at a general election of its members.

The imperative of the federal and provincial negotiators was simple: Gitxsan people are Canadian citizens so there must be Gitxsan elections so they can vote for their chiefs and wing chiefs in the future. A failure to provide such elections for Gitxsan people would violate their democratic rights as per the Charter of Rights and Freedoms. The experience of the Gitxsan in these frustrating negotiations brings to mind the inspiring work of James Tully:

At the end of the day, therefore, what keeps the imperial network going and the structural relationships of domination in their background place, is nothing more (or less) than the activities of powerfully situated actors to resist, contain, roll-back and circumscribe the uncontainable democratizing negotiations and confrontations of civic citizens in a multiplicity of local nodes.Footnote 23

The federal and provincial negotiators also expressed concern about the Gitxsan discriminating against each other and against non-Gitxsan if they did not explicitly recognize and incorporate other rights and freedoms as set out in the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. Additionally, the federal and provincial negotiators expressed their discomfort about potential Gitxsan violations of human rights as per federal and provincial legislation, though they provided no examples except the lack of elections.

From what mindset was the federal and provincial operating? How might they understand the logics of their role and position as they met with Gitxsan? Lawyer and legal historian Richard Overstall offers this insight:

One of the invisibilities for the federal negotiators is how their adherence to representative democracy is moulded and blinded by path dependence. This concept argues that present options for political, economic and technological acts are constrained by prior decisions and history. … For representative democracy, as performed in post-colonial Canada, it may be useful to see how its predecessor English institutions came in to being. … The representative democracy path thus retain its origins of supreme executive and legislative power backed by a compliant bureaucracy and a monopoly of legitimate violence, albeit with the possibility every four years or so of a popular vote between two or three very similar groups of executives and legislators.Footnote 24

These 2019 negotiations were yet another effort on the part of the Gitxsan to address the continual “path dependant”Footnote 25 demands of the state. Over the years, when descriptions and explanations of their legal and political ordering fell on deaf ears, this Gitxsan group pragmatically created new structures and instruments intended to somehow meld the Gitxsan matrilineal kinship system with representative Canadian democracy and governance structures. These pragmatic responses have meant that the Gitxsan, and other Indigenous peoples, have their own historic legal and political institutions as well as contemporary legal and political institutions. Despite contradictions between the past and present institutions, both historic and contemporary law and political authorities continue to operate through them. This is a situation that generates ongoing problems and internal conflicts, with the basic result of undermining and delegitimizing Gitxsan governance and law.Footnote 26

So, how might de Sousa Santos’ abyssal thinking be helpfully applied to the Gitxsan? Boaventura de Sousa Santos is writing about the Western tension between social regulation and social emancipation, and the visible foundation beneath metropolitan societies and the invisible foundation beneath colonial territories. Again, according to de Sousa Santos, the “intensely visible distinctions structuring social reality on this side of the line are grounded in the invisibility of the distinction between this side of the line and the other side.”Footnote 27 What is visible to the federal and provincial negotiators is the Canadian state complete with its own forms of political, legal, and economic institutions – and all that created these legitimacies and institutions – histories, power, and corresponding narratives. The colonial ideology of this imaginary “exhausts” anything beyond itself because its very definition is a denial of other legitimacies.

In turn, what remains invisible to the federal and provincial negotiators are the Gitxsan political, legal, and economic institutions – and all that created these legitimacies and institutions – histories, power, and corresponding narratives. Through their interactions with the Gitxsan, the federal and provincial negotiators maintain and uphold their visible universe while denying and erasing that which comprises Gitxsan society, past and present, unless it is recognizable and cognizant to state forms. In effect, the federal and provincial negotiators are “policing the boundaries of relevant knowledge,” thereby wasting the “immense wealth of cognitive experiences” of the Gitxsan.Footnote 28 This colonial policing is strengthened by the abyssal incommensurability strategy, wherein that which is beyond the Canadian state is simply characterized as incommensurable, as well as deficient and inferior.Footnote 29

Boaventura de Sousa Santos argues that the “first condition for post-abyssal thinking is radical co-presence. Radical co-presence means that the practices and agents on both sides of the line are contemporary in equal terms.”Footnote 30 Creating this condition for the Gitxsan means comprehensively restating and articulating their own society – complete with institutions, law, economies, polities, histories, knowledges, and meaning-holding/creating narratives. Radical copresence means that the federal and provincial representatives expand their abilities to imagine, see, and appreciate other expressions of law, political participation, and inclusion. This simple solution means first understanding one’s own limitations and then deliberately developing a shared standard for evidence because, as political philosopher Michael Blake writes, “When there is no shared standard for evidence, then people who disagree with us are not really making claims about a shared world of evidence. They are doing something else entirely; they are declaring their political allegiance or moral worldview [in the absence of shared evidence].”Footnote 31

Arguably, abyssal thinking has become a part of neocolonialism, as is evidenced by the public claims that the “government is failing to defend the democratic rights of First Nations communities to resist their hereditary leaders.”Footnote 32 Abuses of power and corruption, along with the promise and failure of law, are the stuff of world history and are also recorded in Indigenous oral histories. These are reasonable collective struggles for Indigenous peoples but are only manageable when their legal orders are intact, complete with accountability, political inclusion, fairness, and legitimate processes. However, what unfortunately happens is that the media, the state, and others opportunistically pick up on Indigenous conflicts only to reduce them to their simplest parts, and, further, polarize these into, for example, hereditary leadership versus elected band councils.

These kinds of political dichotomies are a failure of basic civility where collective and legitimate processes of reason are not applied because Indigenous legal orders have been undermined.Footnote 33 For change to occur and for radical copresence to be possible, the Gitxsan requires global cognitive justice, enabled by no less than a new kind of post-abyssal thinking.Footnote 34

Gitxsan Democracy

How are Gitxsan democracy and law invisible to Canada according to de Sousa Santos’ abyssal thinking paradigm? In the next section, I explore one historic narrative to begin making visible Gitxsan resources for thinking about citizenship and democracy as the first step to radical copresence.Footnote 35 What is important to this narrative exploration is that citizenship and intense democracy are evident and operating within two nonstate societies: the Gitxsan and the Nisga’a.Footnote 36 This narrative was told by John Brown (Kwiyaihl) from the Gitxsan village of Kispiox and recorded by early anthropologist Marius Barbeau in 1920.Footnote 37 Oral histories are one form of the intellectual property owned by the Gitxsan and are further explained later in the chapter. While reading the narrative, keep in mind that access and the extensive trade system were essential to both the Nisga’a and Gitxsan economies.

A Peace Ceremony Between the Nisga’a and the Kisgegas

The people from the Nisga’a Nass Valley and the people from Gitxsan village of Kisgegas had made friends. This peace agreement was broken when Meluleq, the [Frog]Footnote 38 chief of Kisgegas killed Tsastawrawn, a Nisga’a. Wiraix [Wolf], also from Kisgegas, murdered another Nisga’a named Guxmawen. In retaliation, a Nisga’a murdered Kwisema. For a long time, the Kisgegas did not go to the Nass Valley.

The Nisga’a sent word to the Kisgegas that they wanted to make friends and [they proposed a Gawaganii (Gitxsan term), or Peace Ceremony].Footnote 39 When they arrived, there was a large party of them. The Kisgegas gathered together to meet them. They had invited people from [the Gitxsan villages of] Kispiox and Gitanmaax. The Nisga’a feast party camped just above Kisgegas village.

Meluleq was ready for the ceremonies, and he stripped himself naked to meet his guests. Wiraix did the same. Tsenshoot followed their example, as well as Guxmawen.Footnote 40 All this for meeting one another. The flies were very bad at that time of the year, but they did not [show that they minded] them. They did not even brush them away, although they could hardly endure them.

One of the Nisga’a said, “This is the last day for your village!”

Wiraix answered, “You have entered the Wolves’ mouths. You won’t be alive tomorrow.”

Tsenshoot spoke to Meluleq, “You won’t see the sun tomorrow. This is the last time you will look at the sun!”

Meluleq answered, “The crows and the animals will eat your flesh. You make me angry now!”

The Kisgegas gathered and built a barricade with big trees in front of their village and they built another barricade in front of the Nisga’a [camp]. They put the barricade across to show that the Nisga’a were not to pass beyond it. If one of the Nisga’a went beyond this barricade, those on the opposite side would kill him. The same with the Kisgegas: if they went beyond their barricade, they would be destroyed. Then the Kisgegas went back to their houses, and the Nisga’a went back to their camp.

The Gitxsan fired off blank cartridges, only powder, without bullets in their guns. The Nisga’a did likewise.

Then the Kisgegas sang songs, and they sang a peace song. The Nisga’a also sang peace songs. The Kisgegas blew white swan-down on the heads of the Nisga’a, and, in turn, the Nisga’a did the same to them. They composed a song about the peace, the words of which were that they were making peace. This was a peace performance.

In the evening, the invited Nisga’a guests arrived at the village and the Kisgegas allowed them to come forward. The Nisga’a gathered on one side of the village. Two people were delegated for the peace performance. Guxmawen did not come in person but he sent his daughter on his behalf; she stood in his stead. The other was Tsemshoot, also Nisga’a.

All the Kisgegas came out of their houses. No one had dangerous weapons, only sticks and their hands. The Nisga’a hit some Kisgegas, and the Kisgegas hit the Nisga’a with their hands and with the sticks. Both Tsemshoot and Guxmawen’s daughter had sticks and they kept waving these around until they were both captured. The Kisgegas captors covered Tsemshoot and Guxmawen’s daughter with a caribou hides and took them prisoner. Then the mock fighting stopped.

They all sang the song that they had composed during the night about making peace, with the words about how they were to make peace. Then everyone entered the houses. Tsemshoot was taken to Meluleq’s house and there were two men to guard him. While Tsemshoot stood, they placed caribou skins all along the house for him to walk on until he got to the back of the house. A very big caribou skin was spread out and they on this they piled many pillows for Tsemshoot to sit on. It was a great seat for him. They piled trade blankets to about four feet high. When he wanted water, the guards brought it to him.

They did the same for Guxmawen’s daughter, and she was seated at the back of Wiraix’s house. Two men of noble birth stood on each side of her to guard and watch her. The whole village gave a grand feast. The Kisgegas gave many furs to all the Nisga’a: beaver, marten, caribou, and fisher pelts. The Nisga’a went back to their camp with a bundle of various skins given them by different Kisgegas.

In the morning, the Nisga’a gave their dance. Those performing in the Peace Ceremony were not given food. That was the rule. Nobody in the song or dance was allowed to eat for one day. After they fasted for one day, the very best food was prepared and passed around. The bodyguards of Tsenshoot and Guxmanwen’s daughter had also fasted, so they were led to the food too, and they ate to their satisfaction.

The dance lasted for four days in one of the largest houses in the village. Then four men led the prisoners to that house. They were seated at the back of that house for the last big dance. The Nisga’a sat on one side, and the Gisgegas on the other. The Nisga’a danced until midday, and they picked out four of the best men and placed them on seats of honor.

Meluleq took a white tail feather of an eagle and dipped it in blood so that one half turned red. He gave this feather to Tsenshoot, placing it in his hand.

Waraix did the same with Guxmawen’s daughter. They got the very best white handkerchief from the white man’s store and wrapped her hand in it, and on her head, he planted two swan’s feathers that he got from the Nass.

The villagers got ready before the Nisga’a could leave them. They gave the Nisga’a a farewell dance, dancing behind them until they were out of sight. The Nisga’a also danced as they were on their way homewards. They sang a song in the Sekani language, advising them that they would enjoy peace with them forever. The Kisgegas gave the Nisga’a a song, and the Nisga’a gave the Kisgegas another song.

Then they went back with them to the Nass. Tsenshoot took one of the swan’s feathers and returned it to Meluleq before returning to his own people. This was a sign of deep friendship that was interpreted with the words “I have given you peace and friendship for years to come.” Guxmawen’s daughter said the same words to Wiraix. The Peace Ceremony was over.

Analysis

As we turn to the analysis of the above narrative, John Borrows provides an important reminder to not idealize Indigenous peoples.

We need such laws not only because we are good people with life-affirming values and behaviours. We also require these laws because we are “messed up”. Indigenous law must be practiced in the real world with all its complexity. … Law does not just flow from what is beautiful in Anishinaabe or Canadian life. Law also springs from conflict. It emerges from our responses to real-life needs, which are often rooted in violence, abuse, exploitation, dishonesty, political corruption, and other self-serving and destructive behaviours.Footnote 41

The Peace Ceremony is a complicated oral history and it would be easy to get lost in its detail and in our own responses to difference – those aspects that are beyond our own terms of reference and experience. Given this, it is important to be specific about the question one is asking of the narratives, stories, or oral histories.Footnote 42 To center this analysis on questions of governance and to inform my discussion of Gitxsan democracy, the question I am asking of this narrative is: How should one respond to a violent rupture of a long-term political relationship with a neighboring people? And since this analysis is about nonstate democracy, the “who” and “why” of responding to this rupture of arrangement between neighboring peoples are significant.

There are a number of basic elements that are relevant to the question I am asking of the narrative, and I have highlighted these here for ease of reference.

The Gitxsan and the Nisga’a are neighboring peoples, their lands are adjacent. The two peoples had “made friends,” suggesting they had not always enjoyed peace, but their relationship was peaceful at the onset of the narrative.

This peaceful relationship was disrupted by three murders: (1) Gitxsan Meluleq killed Nisga’a Tsastawrawn, (2) Gitxsan Wiraix killed Nisga’a Guxmawen, and (3) A Nisga’a (unnamed) killed Gitxsan Kwisema.

Consequently, the Gitxsan did not travel to the Nass Valley for a long time.

The Nisga’a requested a return to peace, and they initiated a peace.

The Nisga’a traveled to Kisgegas, and they made a camp just above Kisgegas village.

The Kisgegas invited other Gitxsan from the villages of Gitanmaax and Kispiox.

Meluleq and Wiraix prepared by stripping themselves naked to meet their Nisga’a guests. In turn, Nisga’a Tsenshoot and Guxmawen also stripped in order to meet with the Gitxsan. Without clothing, everyone suffered terribly because of the bad blackfly season, and they “did not show that they minded.”

Both Nisga’a and Gitxsan traded insults, the Gitxsan built two barricades, and both sides fired blanks at the other.

Both sides sang peace songs, and they blew white swan feathers on each other. A new peace song was composed.

Two Nisga’a were delegated for the Peace Ceremony: one was Guxmawen’s daughter and the other Tsemshoot.

The Gitxsan and the Nisga’a armed themselves with sticks, and then they hit each other using only their hands and the sticks. Guxmawen’s daughter and Tsemshoot also had sticks which they waved around until they were ‘captured’.

Guxmawen’s daughter and Tsemshoot were separately taken to different longhouses, they were covered in caribou hides, and more caribou hides were placed on the earth for them to walk on to the back of the longhouse. Additional trade blankets were piled high, many pillows were placed for them to sit on, and guards of noble birth watched them and tended to their needs.

Kisgegas gave a big feast and different Kisgegas gave many furs of all kinds to the Nisga’a. Those who were part of the Peace Ceremony fasted.

The next morning, the Nisga’a performed their dance, then those who had fasted were fed.

The dance lasted four days, then the ‘prisoners’ were brought to the longhouse for the last dance.

The Kisgegas were seated on one side, the Nisga’a on the other. Four ‘best’ Nisga’a were placed in the seats of honor.

Meluleq took a white tail feather, dipped it in blood so that half of the feather was red. He gave this feather to Tsemshoot. Waraix did the same with Guxmawen’s daughter.

Waraix also wrapped Guxmawen’s daughter’s hand in a white man’s handkerchief, and then he placed two white swan feathers in her hair (the feathers were from the Nass).

The Kisgegas gave the Nisga’a a farewell dance, and they danced behind the Nisga’a as they left for the Nass Valley. The Nisga’a also danced on their way home.

The Kisgegas gave the Nisga’a a song, and the Nisga’a gave the Kisgegas a song.

Tsenshoot gave Meluleq one of the swan feathers back, and pledged peace and friendship for years to come. Guxmawen’s daughter did the same with Wiraix.

This is a rich and perhaps deceptively simple narrative. For this analysis, there are two main legal responses to the question I have posed to this narrative: (1) the Nisga’a decided to restore peace by initiating a Peace Ceremony, and (2) the Gitxsan accepted the invitation to restore peace and to host the Peace Ceremony .

For the most part, the reasoning for these two legal responses is implicit rather than explicit. What is at the heart of this narrative is that the relationship between the Nisga’a and Gitxsan was important and had previously been restored and maintained, and this was the continuing primary response. The valuable gifting of a name, songs, and dances are all very precious as well as structural for each people’s governing institutions. These gifts also comprise part of the intellectual property for both peoples, and their inclusion for the Peace Ceremony indicates the paramountcy of peace between the two peoples. The relationship between the Gitxsan and Nisga’a enabled trade, territorial access, and travel, all of which were managed through carefully arranged marriages and lineages. Restoring relationships usually requires accepting responsibility for harms and compensation. The Gitxsan acknowledged their responsibility for the events leading to the Peace Ceremony and they paid compensation in the form of the furs and feasting. The Nisga’a accepted their responsibility for reacting to violence with violence by initiating the Peace Ceremony and by gifting the Gitxsan with a name and a song.

However, there is so much more going on in this rich narrative that provides important insights into how people were managing themselves and the conflict. As the first step, both the Nisga’a and the Gitxsan accepted responsibility for the conflict and for its resolve – individually and collectively. Secondly, key individuals from both parties made themselves completely vulnerable (naked) and transparent (no weapons) to the other. Third, both sides exercised exquisite physical, emotional, and mental discipline in the mock battle of fake bullets, sticks, and hands. All the parties would have been extraordinarily careful to not accidentally injure one another in their physical demonstration of war and their implicit acknowledgment of its ultimate possibility.

Fourth, the songs, names, and dances are all legal expressions and ongoing performative requirements for the public feast (the main legal, economic, and political institution for both the Gitxsan and Nisga’a), and continue to be performed by Tsenshoot, Guxmawen, Meluleq, and Wiraix, and others to this day. In this way, for both the Nisga’a and Gitxsan, the Peace Ceremony continues to be inscribed with legal and political meaning, becoming part of an ongoing public memory and part of the precedent record from which to draw from for solving future conflicts.

Finally, both the Gitxsan and Nisga’a had to have had the political and legal authority to act on behalf of their respective Houses to have initiated this major inter-societal event and for it to be recorded in the oral histories and for it to shape the ongoing relationship between the peoples. The songs, dances, and names form the architecture (i.e. the warp and woof) of Gitxsan decentralized governance, and they also hold articulations of law. What is invisible in the narrative, and in the enactment of the respective political and legal authorities, are the discussions, disagreements, and consent that would have taken place prior to the Peace Ceremony. Many, many people, all legal agents to the fullest extent themselves, were necessary to make the Peace Ceremony possible: preparing enormous quantities of food (i.e. gathering, hunting, fishing, etc.), hunting and preparing the hides and furs, enacting the mock battle, creating and performing the songs and dances, and formal witnessing of the entire process for future recall.

The Peace Ceremony narrative stands for many things, including the human potential for violence, and the continuing need for individual and collective agency in rebuilding, maintaining, and protecting relationships between peoples. There are also some elements that raise questions that can generate more discussion and learning. For instance, why did the Nisga’a sing a Sekani song? Likely it would have been a gift from the Sekani, and the narrative captures this detail to emphasize the importance of relationships with other neighboring peoples. Another question is about Guxmawen traveling to Kisgegas, but not participating in the Peace Ceremony. Instead, his daughterFootnote 43 participated in the Peace Ceremony on his behalf, and likely this would have been related to a saving-of-face requirement for Guxmawen. The richness is that these and other questions can be explored in future conversations in a way that ensures that law is part of people’s everyday lives – in a way that generates questions rather than focuses on answers.

Gitxsan Relationships

[This is] a starting point for a new kind of inquiry into the relational dimensions of contemporary conditions of the rule of law. Three key ideas from Fuller’s jurisprudence are reflected … The first is the centrality of relationships. The second is the significance of the form of a relevant legal modality to the shape and fate of those relationships. The third is the possibility that certain legal forms will, for relational reasons, be unsuited to the contexts within which they might come to operate.Footnote 44

With this brief introduction to Gitxsan society, I want to bring the relationships that create Gitxsan society into focus. To begin, the Gitxsan are a nonstate, decentralized society wherein political and legal authorities are distributed and acted on horizontally between matrilineal kinship groups of extended families – the House – within which there are reciprocal legal obligations.Footnote 45 This is an exogamous system, so each person’s father’s House is a part of a different clan with separate responsibilities to each Gitxsan citizen. The Gitxsan legal, political, and economic orders operate through these dense networks of kinship ties. Each individual Gitxsan person is a legal agent within her or his House. Beyond the House, which is relationally autonomous,Footnote 46 it is the House that is the collective legal agent in all external interactions with other Houses and with the larger networks of clans and inter-societal alliances.

House chief ‘names’ are part of the House’s governing structure and intellectual property, and are the form through which House territories and other property are held in trust. The authority of a House chief depends on the fulfillment of the House’s legal and political obligations through the entire system. Without centralized and hierarchical bureaucracies, Gitxsan society is maintained by a series of stabilizing tensions created by an absolute requirement to cooperate and a deep corresponding ethic of competition and autonomy – from the individual to the larger kinship levels. For example, the authority and ability of the House chief to fulfill her or his larger legal obligations depends on the willing economic contributions and labor of each member. However, since a person’s House membership operates as a placeholder rather than locking people in, members can choose to align themselves elsewhere in the system, thereby causing a significant economic loss to the House chief and the House.Footnote 47

Liability in this system is collective. For example, a person is responsible to their House for their actions, but it is the House that is liable for that individual’s actions in the larger network. Furthermore, injuries caused by individuals are also collective, so if someone is injured, the entire House is considered injured and there is consequent collective liability and compensation. Admittedly, this is a gross simplification of a complex society, but it nonetheless contains the essence of how the kinship network operates throughout Gitxsan society. It is this complex of legal, economic, and political ordering that is the basis of Gitxsan citizenship and democracy – mutually constituting and fluid with Gitxsan citizens – as individual and collective agents, accountable to and responsible for the maintenance of the larger whole.

To return to Rundle’s relationship theory, she argues that relationships and their demands were necessary to and constituted Lon Fuller’s legalities, and, further, that a society’s institutional forms have carriage for those relationships because they hold the “responsibilities and opportunities for the authority of law itself.”Footnote 48 According to Rundle, Fuller’s jurisprudence applies to all governing relationships, not just to a state’s legislative function. This insight frees Rundle’s analysis from being state-centric and releases its potential application to nonstate societies such as the Gitxsan.

Rundle’s theory advocates the centrality of relationships to a society’s legal order and its constituting legalities.Footnote 49 Gitxsan society is entirely constructed of individual and collective relationships, kinship networks through which Gitxsan law and governance operate and are collaboratively managed. Each individual legal agent has responsibilities to their kinship network, and they have the ability to exercise choice and accountability in how they align themselves and contribute to the collective.Footnote 50 This kind of relational accountability, operating at individual and collective levels, constitutes a form of intense democracy, or what Christine Keating calls “fullest democracy.”Footnote 51

The second theme of Rundle’s relationship theory concerns the “significance of the form of a relevant legal modality to the shape and fate of those relationships.”Footnote 52 The paramount political and legal unit within Gitxsan society is the House, which is organized matrilinealy, and, at least historically, the size of the House allowed for face-to-face interaction of all House members within each House.Footnote 53 These kinship relations are crosscutting, extending beyond the matrilineal families, clans, and villages, and also connecting to other peoples such as the Nisga’a, Haida, Tsimshian, Wet’suwet’en, and beyond. In this way, they are the relational filament weaving the largest political collectivity – that of the society – but are also building important political, legal, and economic connections to other peoples. Gitxsan democracy, then, captures Gitxsan people within its nonstate procedural grasp and collective coercive power, as demonstrated by the Peace Ceremony.Footnote 54

Finally, Rundle’s theory includes the possibility that certain legal forms will, for relational reasons, be unsuited to the contexts within which they might come to operate.Footnote 55 As mentioned earlier, colonialism in Canada included the Indian Act, which set out the imposed structure and procedures for electing small, representative administrative entities. This colonial process included dividing larger societies of Indigenous peoples into small groups that were geographically pinned on reserves as per the Indian Act and the Constitution Act, 1867.Footnote 56 The consequence of imposing this particular form of representative democracy has been devastating to Gitxsan ordering, where former historic political and legal accountability crossed village boundaries and extended over the entirety of Gitxsan lands. In short, the larger legal order has been fractured into six small reserves, and has undermined the historic political and legal institutions of Gitxsan society. This is the very embodiment of de Sousa Santos’ assertion that “Democracies are dying democratically,”Footnote 57 but in this case, it is the attempted murder of intense Gitxsan democracy ‘democratically’ via colonial legislation and by agreement. Nonetheless, the Gitxsan are still the Gitxsan, but now are struggling with conflicts arising from the imposed governing structures and diminishment of the Gitxsan legal order.Footnote 58

Conclusion

When Cree legal scholar Darcy Lindberg analogized the universe to law, he wrote that one must learn to see all the stars in the universe because all the stars matter.Footnote 59 These other legal orders, institutions, and law are rendered invisible by the Canadian state’s grid of intelligibility. Given this, the project of creating radical copresence means adding to the national legal imagination and expanding the Canadian grid of intelligibility. This work, for Indigenous peoples, including the Gitxsan, means substantively and procedurally articulating Gitxsan law and legal institutions to support the practice of Gitxsan law. All the attendant questions have to be worked out while doing the research and in the actual practice of Gitxsan law.

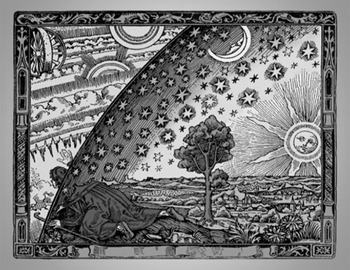

The image in Figure 11.1 captures Lindberg’s analogy and it illustrates the wonder of first seeing those formerly invisible stars.Footnote 60 This powerful image also embodies de Sousa Santos’ abyssal thinking, wherein the visible is made visible by lifting the curtain of abyssal limitations, and, in doing so, that beyond the curtain can become copresent.

Figure 11.1 Cover of L’atmosphère: Météorologie populaire

The challenge for the Gitxsan and other Indigenous peoples is to rebuild their legal orders by the hard work of critically and collaboratively rearticulating and restating their historic legal resources. This approach will enable Gitxsan peoples to restore the best practices of their former intense democracies, complete with inclusive and active citizenship, for today’s political and legal negotiations, and self-determination and governance demands.

In taking on the work of rebuilding and restating Indigenous law, we should not “overlook the concrete possibilities available for creative and effective negotiations and confrontations of civicisation and de-imperialism,”Footnote 61 or that “Another world is actual” not just possible: “Despite the devastating trends, another world of legal, political, ecological, and even economic diversity has survived and continues to be the loci of civic activities for millions of people.”Footnote 62