Introduction

How do entrepreneurs use framing to secure support and legitimacy from stakeholders or audiences? While prior research on entrepreneurial framing (Snihur, Thomas, Garud, & Phillips, Reference Snihur, Thomas, Garud and Phillips2022) has focused on the challenge of appealing to a particular audience (e.g., investors, incumbents, or complementors) in the early stage of industry formation, such challenges remain in the later stages, when even more support from different audiences or stakeholders is needed (Chapple, Pollock, & D'Adderio, Reference Chapple, Pollock and D'Adderio2022; Deephouse, Bundy, Tost, & Suchman, Reference Deephouse, Bundy, Tost and Suchman2017; Lounsbury & Glynn, Reference Lounsbury and Glynn2019). A change in sources of audience that confers legitimacy involves not just iterative revisions of framing, namely, reframing (Kim, Reference Kim2021; Tracey, Phillips, & Jarvis, Reference Tracey, Phillips and Jarvis2011), but also changes in entrepreneurial identity (Gioia, Patvardhan, Hamilton, & Corley, Reference Gioia, Patvardhan, Hamilton and Corley2013; Navis & Glynn, Reference Navis and Glynn2011) which legitimates new appeals. The question of how entrepreneurial framing evolves while having to appeal to different audiences over time has been relatively unexplored, leaving largely black-boxed social or cultural dynamics (Lounsbury & Glynn, Reference Lounsbury and Glynn2001, Reference Lounsbury and Glynn2019) that justifies continual reframing, generates identity change, and enables legitimacy acquisition. This gap motivates our study, which aims to explore: How do nascent entrepreneurs draw on cultural resources to reframe their businesses to claim new identities and gain legitimacy over time?

We draw on the literature on entrepreneurial framing and identity change to formulate our theoretical arguments. Accounts of entrepreneurial framing vary widely, and in this article centered on cross-level and framing dynamics, we focus on reframing, which is characterized by a ‘frame deployment process’ in which frames or framings underlie different aspects of a venture to overcome resistance and mobilize resources (Tracey et al., Reference Tracey, Phillips and Jarvis2011). While framing involves the purposive use of language to provide an interpretive frame of reference for a change or venture, reframing refers to a dynamic process where a frame is restated or revised to appeal to different, new venture audiences. Reframing can be periodic as entrepreneurs respond to emergent contingencies and changing concerns. The stronger the change in market dynamics is, the greater the probability of entrepreneurial engagement with reframing or changes in framing content. Reframing is crucial in responses by entrepreneurs who are interested in aligning with various value orientations and appealing to different audiences to acquire resources and increase legitimacy. Time-shifting and audience-varying effects invariably involve the coherence, consistency, and alignment that characterize the strategic nature of reframing (Fisher, Kuratko, Bloodgood, & Hornsby, Reference Fisher, Kuratko, Bloodgood and Hornsby2017) – hence, a concern with how cultural context justifies framing in related spaces or times. As Snihur et al. (Reference Snihur, Thomas, Garud and Phillips2022) indicate, ‘As part of their framing efforts, entrepreneurs leverage cultural resources to make “the unfamiliar familiar by framing the new venture in terms that are understandable and legitimate”’ (Lounsbury & Glynn, Reference Lounsbury and Glynn2001: 549). To be successful, then, entrepreneurial framing must become a form of ‘cultural reframing’ (Hedberg & Lounsbury, Reference Hedberg and Lounsbury2021: 444) that requires entrepreneurs to use cultural resources to ‘continually make and remake stories to maintain their identity and status’ (Lounsbury & Glynn, Reference Lounsbury and Glynn2001: 560) and manage legitimacy judgments over time-shifting and audience-varying processes (Fisher et al., Reference Fisher, Kuratko, Bloodgood and Hornsby2017).

As cultural reframing works, entrepreneurial identity changes. An identity that defines ‘who we are’ and ‘what we do’ is not a categorical essence or substance but a strategic performance; it is legitimately achieved through a process of structuring or becoming where ‘both the narrator and the audience are involved in formulating, editing, applauding, and refusing various elements of the ever-produced narrative’ (Czarniawska, Reference Czarniawska1997: 49). Identity is not static but dynamic, as entrepreneurs or organizations continually adapt to environmental changes – a characteristic Gioia, Schultz, and Corley (Reference Gioia, Schultz and Corley2000: 64) term ‘adaptive instability’ and Radu-Lefebvre, Lefebvre, Crosina, and Hytti (Reference Radu-Lefebvre, Lefebvre, Crosina and Hytti2021: 1574) describe as ‘ongoing accomplishment’. The dynamic aspect of reframing resonates with the temporal aspect of identity. Research on reframing thus also prompts a search for the identity change necessary for entrepreneurs to meet new audience expectations over time (Mathias & Williams, Reference Mathias and Williams2018).

The empirical case on which we base this article is a qualitative study of a specific group of ‘informal entrepreneurs’ (Salvi, Belz, & Bacq, Reference Salvi, Belz and Bacq2023), China's shan-zhai phones. Culturally rooted in the Chinese context (Tse, Ma, & Huang, Reference Tse, Ma and Huang2009), the term ‘shan-zhai’ can also mean ‘creative imitation’ (Wang, Wu, Pechmann, & Wang, Reference Wang, Wu, Pechmann and Wang2019), which has attracted attention in emerging economies. The Chinese shan-zhai, a process described by the Wall Street Journal as ‘the sincerest form of rebellion in China’ (Canaves & Ye, Reference Canaves and Ye2009, January 22), has grown out of the informal economy but has come to challenge the national champions defended by the state. After years of suppression, competition, and negotiation, some actors have become legitimate enough not only to have their products accepted in their society but also worldwide. Chinese shan-zhai phones have a rich history of rhetoric, innovation, and change (Lee & Hung, Reference Lee and Hung2014) in which nascent entrepreneurs have used their socio-cultural resources to reframe their ventures and gain legitimacy amid continual growth.

Examining entrepreneurial framing and identity change through informal or problematic industries, such as Chinese shan-zhai phones, offers a promising route for capturing the richness of the cultural dynamics contextualizing entrepreneurship. Framing through discourse or narrative is relevant for informal entrepreneurs seeking to use symbolic or cultural resources to compensate for their lack of material resources and low status (Abid, Bothello, Ul-Haq, & Ahmadsimab, Reference Abid, Bothello, Ul-Haq and Ahmadsimab2023). Extending such framing to new audiences is very demanding for informal entrepreneurs, who often confront resistance from multiple sources and need to go through very lengthy processes to become established (Webb, Bruton, Tihanyi, & Ireland, Reference Webb, Bruton, Tihanyi and Ireland2013; Webb, Khoury, & Hitt, Reference Webb, Khoury and Hitt2020). For informal entrepreneurship, the point is not to develop a process of ‘identity affirmation’ (Zuzul & Tripsas, Reference Zuzul and Tripsas2020) but to engage in ‘the institutional work of reframing informality’ (Salvi et al., Reference Salvi, Belz and Bacq2023: 280) that, in the aggregate, forges a ‘coherent collective identity’ (Patvardhan, Gioia, & Hamilton, Reference Patvardhan, Gioia and Hamilton2015) for achieving legitimacy and gaining momentum. The distinctiveness of examining the relationship between framing and identity across informal settings is thus twofold. It makes more use of symbolic or cultural resources that contextualize the processes of entrepreneurial framing and identity change (Lounsbury & Glynn, Reference Lounsbury and Glynn2019). In addition, it provides insights into the dynamics of framing that involves multiple audiences over time (Deephouse et al., Reference Deephouse, Bundy, Tost and Suchman2017).

Overall, this article makes three contributions. First, we enrich the literature on entrepreneurial framing (Snihur et al., Reference Snihur, Thomas, Garud and Phillips2022) by providing a fine-grained conceptual analysis of the dynamic interactions between framing content and processes. Our analysis of the shan-zhai case shows how entrepreneurial framing, in the form of pragmatic, nationalistic, and comprehensive reframing, occurs through cultural processes and repeated frame revisions. Second, we extend identity research by investigating the complexity of cross-level identity dynamics affected by cultural forces (Ashforth, Rogers, & Corley, Reference Ashforth, Rogers and Corley2011; Gioia, Patvardhan, et al., Reference Gioia, Patvardhan, Hamilton and Corley2013). We also show how a change in identity claims is conducive to an industry's transition through contingent resonance with key audiences who offer legitimacy to problematic goods, services, or early-stage ventures. Third, we enhance our understanding of formalizing an informal industry (Salvi et al., Reference Salvi, Belz and Bacq2023), constructed through various levels or sources of legitimacy. The informal industry or economy is illegal, but legitimate among some social groups (Webb, Tihanyi, Ireland, & Sirmon, Reference Webb, Tihanyi, Ireland and Sirmon2009) who, as important resource providers, are likely to change over time. Our case study of Chinese shan-zhai illustrates how an informal industry is formalized or legitimated through continual reframing and the accompanying identity change processes that occur in and throughout the cultural context.

Theoretical Background

Entrepreneurial Framing and Cultural Reframing

The topic of entrepreneurial framing has been central in a growing body of research on strategy and organization (Snihur et al., Reference Snihur, Thomas, Garud and Phillips2022). Underlying this literature is the quest to understand how nascent entrepreneurs mobilize metaphors, analogies, genres, stories, narratives, symbols, or other framing devices to construct a new identity and gain legitimacy for growth and wealth creation (Cornelissen & Werner, Reference Cornelissen and Werner2014; Vaara, Sonenshein, & Boje, Reference Vaara, Sonenshein and Boje2016). Snow and Benford (Reference Snow, Benford, Morris and Mueller1992: 136) define ‘framing’ as ‘an active, process-derived phenomenon that implies agency and contention at the level of reality construction’. Consistent with the linguistic turn, framing is not only a cognitive mechanism for change (Ansari, Wijen, & Gray, Reference Ansari, Wijen and Gray2013; Hiatt & Carlos, Reference Hiatt and Carlos2018; Werner & Cornelissen, Reference Werner and Cornelissen2014) and a cultural resource for influencing others (Alvesson, Reference Alvesson1993; Suddaby & Greenwood, Reference Suddaby and Greenwood2005) but also a strategic process that mobilizes support and updates or renews identity claims to gain legitimacy and other market resources (Snihur, Thomas, & Burgelman, Reference Snihur, Thomas and Burgelman2018; Zhao, Ishihara, & Lounsbury, Reference Zhao, Ishihara and Lounsbury2013).

Framing is a useful lens through which to study the legitimation process by which a new and unfamiliar venture or innovation evolves into an institutional structure, ‘constructed primarily through the production of texts, rather than directly through actions’ (Phillips, Lawrence, & Hardy, Reference Phillips, Lawrence and Hardy2004: 638). For example, in their study on the institutionalization of electric lighting, Hargadon and Douglas (Reference Hargadon and Douglas2001) showed how Thomas Edison framed novel lighting systems as identical to traditional gas lights to secure support and legitimacy from stakeholders. Munir and Phillips (Reference Munir and Phillips2005) noted that the widespread adoption of the roll-film camera was not primarily due to a radically innovative technology that disrupted photography but the outcome of a meaning-making or framing process. Gurses and Ozcan (Reference Gurses and Ozcan2015) found that framing pay-TV in terms of public interest enabled entrepreneurs to win regulators' support when introducing pay-TV to the US television industry. To engage in framing is, indeed, to engage in entrepreneurship that is tied to the ‘discovery, evaluation, and exploitation of opportunities’ (Shane & Venkataraman, Reference Shane and Venkataraman2000: 218). Framing is not simply a self-interested or voluntaristic behavior by agents but is channeled through opportunities that whether political and cultural (Benford & Snow, Reference Benford and Snow2000) or educational and economic (Kinder & Sanders, Reference Kinder and Sanders1996) are derived from a ‘discursive opportunity structure’ (Fiss & Hirsch, Reference Fiss and Hirsch2005; Kellogg, Reference Kellogg2011; McCammon, Muse, Newman, & Terrell, Reference McCammon, Muse, Newman and Terrell2007) that is socially significant at a particular point in time.

Increasing yet diversified accounts have explored how entrepreneurs use framing to exploit opportunity, construct meaning, and build legitimacy around their ventures. In their comprehensive review of the literature, Snihur et al. (Reference Snihur, Thomas, Garud and Phillips2022) have identified a classification of framing content, processes, and outcomes that collectively characterize the dynamics of entrepreneurial framing. On the one hand, ‘framing content’ refers to framing mode, framing language, and framing emphasis, while ‘framing processes’ concern the frame deployment, framing contests, and complementary actions that add to framing efforts. On the other hand, the outcomes of framing are related to the legitimation of either a venture or the field in which entrepreneurial actions take place. In this article, we follow this review to define the scope of our study. We focus on reframing as a distinctive aspect of the framing or frame deployment process where entrepreneurs restate frames to emphasize different aspects of their venture to acquire resources and mobilize support over time (Kim, Reference Kim2021; Tracey et al., Reference Tracey, Phillips and Jarvis2011). Reframing involves making changes to entrepreneurial frames, similar to the ‘strategic reorientation’ (McDonald & Gao, Reference McDonald and Gao2019), ‘redefinition’ of a venture (Gioia, Thomas, Clark, & Chittipeddi, Reference Gioia, Thomas, Clark and Chittipeddi1994; Giorgi, Bartunek, & King, Reference Giorgi, Bartunek and King2017; Martin, Reference Martin2016; York, Hargrave, & Pacheco, Reference York, Hargrave and Pacheco2016), or ‘frame shifting’ (Coulson, Reference Coulson2001; Werner & Cornelissen, Reference Werner and Cornelissen2014), all of which lead to ‘a new construal of a well-understood phenomenon’ (Coulson, Reference Coulson2001: 201). Our concern with this outcome is centered on the construction of a new ‘collective identity’ (Patvardhan et al., Reference Patvardhan, Gioia and Hamilton2015; Polletta & Jasper, Reference Polletta and Jasper2001; Webb et al., Reference Webb, Tihanyi, Ireland and Sirmon2009), which, over time, has legitimated the Chinese shan-zhai cellular phone industry in a way that facilitates the scaling of new ventures and positive audience evaluations.

Reframing, as a process of frame deployment, shifting, or reorientation, is interactive and sequential. Framing processes interact dynamically with changes in framing content. Wry, Lounsbury, and Glynn (Reference Wry, Lounsbury and Glynn2011) have highlighted the dynamics of entrepreneurial framing via storytelling. At times, entrepreneurs may coordinate field-level ‘growth stories’ to project market expansion that benefits them all; at other times, they tell firm-level stories of competition and distinctiveness. Kim (Reference Kim2021) has examined how in a crisis, actors draw on repeated reframing to simultaneously destroy and construct frames. Since reframing often undermines existing frame content, the ways in which words are consistently interpreted, logically restated, or reinforced to support or dismantle a standpoint pose an enduring challenge to framing agents (Snihur et al., Reference Snihur, Thomas and Burgelman2018). Frame sequencing – the mobilization of framing strategies over time – occurs when frames are continually subject to revision; ventures evolve and require different audience-frame fits, and new elements become available and are used in a framing bricolage informed by the changing position of the framing agent (Kim, Reference Kim2021; Lempiälä, Apajalahti, Haukkala, & Lovio, Reference Lempiälä, Apajalahti, Haukkala and Lovio2019). Navis and Glynn's (Reference Navis and Glynn2010) analysis of satellite radio notes this contingent nature of ventures' claims, indicating that these entrepreneurial firms shifted their framings from emphasizing a collective identity to stressing a distinctive organizational identity once their new market category had achieved legitimacy. In their study of the Italian manufacturer Alessi, Dalpiaz, and Di Stefano (Reference Dalpiaz and Di Stefano2018) have noted the importance of sequence in language, portraying framing change – for example, from a single framing strategy to the simultaneous mobilization of several framing strategies, including memorializing, revisioning, and sacralizing – as a transformative endeavor. McDonald and Gao (Reference McDonald and Gao2019) have shown how new ventures are constantly reoriented to anticipate, justify, and stage changes in regard to various audiences.

The dynamic and sequential nature of the reframing process leads to the emphasis on coherence and resonance across the meanings of one frame to another, which is associated with a new and evolving venture (Cornelissen, Holt, & Zundel, Reference Cornelissen, Holt and Zundel2011). What is coherent and what resonates clearly depend on the cultural context or process that shapes audiences' understanding, elicits favorable interpretations of framing change, and provides resources for framing dynamics (Cornelissen, Durand, Fiss, Lammers, & Vaara, Reference Cornelissen, Durand, Fiss, Lammers and Vaara2015; Swidler, Reference Swidler1986). The ways in which culture or context matter are, indeed, inherent in the socially constructed nature of entrepreneurial framing, which concerns diverse interests across multiple new venture audiences. To be successful, then, reframing invariably involves the skilled use and manipulation of cultural resources, which enable new identity claims and the acquisition of legitimacy and other resources (Lounsbury, Gehman, & Ann Glynn, Reference Lounsbury, Gehman and Ann Glynn2019; Lounsbury & Glynn, Reference Lounsbury and Glynn2001, Reference Lounsbury and Glynn2019).

Considering reframing a cultural process adds to the research on entrepreneurial framing or reframing in two ways. Framing is rooted in a culture that is a source of both resource acquisition and external validation. A culture can be seen as a rich pool of resources, a flexible ‘toolkit’ (Swidler, Reference Swidler1986) that contains the logics, vocabularies, names, beliefs, skills, and habits that entrepreneurs can draw from when conducting their framing activity in response to challenges (Cornelissen et al., Reference Cornelissen, Durand, Fiss, Lammers and Vaara2015). A culture can also be seen as a cultural repertoire of frames (Williams, Reference Williams, Snow, Soule and Kriesi2004: 106), ‘the stock of commonly invoked frames’ (Entman, Reference Entman1993: 53), a larger ‘cultural theme’ (Gamson & Modigliani, Reference Gamson and Modigliani1989), or a ‘master frame’ (Gray, Purdy, & Ansari, Reference Gray, Purdy and Ansari2015) that serves as a core resource for the development of more targeted strategic frames. In addition, for framing to be coherent and to resonate, the emphasis needs to align with the focal audience's beliefs, values, aspirations, or ideas (Falchetti, Cattani, & Ferriani, Reference Falchetti, Cattani and Ferriani2022), which are defined and shaped by their socio-cultural systems. Culture defines the success of reframing. The greater a frame's resonance with the cultural system, the greater the probability that the framing endeavor will be successful (Giorgi, Reference Giorgi2017; Jancenelle, Javalgi, & Cavusgil, Reference Jancenelle, Javalgi and Cavusgil2019). This is particularly important for acts of reframing, whose effectiveness is achieved through ‘deploying culture’ (Gehman & Soublière, Reference Gehman and Soublière2017) to exploit volatile discursive opportunities arising from exogenous accidents such as political changes, ethnic revolutions, or technological innovations. Cultural coherence is also critical in reframing. Especially when ventures evolve over time, frame continuity, including both amplification and extension (Snow, Rochford Jr, Worden, & Benford, Reference Snow, Rochford, Worden and Benford1986), allows entrepreneurs to create coherence across venture lifecycles that extant audiences find consistent and new audiences find favorable (Fisher, Kotha, & Lahiri, Reference Fisher, Kotha and Lahiri2016).

Identity Change Through Reframing

Linguistic framing leads to change and innovation only when it enables the individual or collective to develop a new identity that is viewed as meaningful and legitimate by audiences who hold the ‘identity codes’ (Hannan, Pólos, & Carroll, Reference Hannan, Pólos and Carroll2007). Framing can thus also be understood as a discursive form of ‘identity work’ that involves ‘the mutually constitutive processes by which people strive to shape relatively coherent and distinctive notions of their selves’ (Brown & Toyoki, Reference Brown and Toyoki2013). Identity, sometimes referred to as ‘code', ‘category', or ‘image', is defined by three properties: centrality, enduringness, and distinctiveness (Whetten, Reference Whetten2006). Here, what is central and distinctive lies in the embodiment of a set of core features capable of creating optimal returns. Enduringness, according to Gioia, Patvardhan, et al., is best understood as ‘having continuity over time rather than … “enduring”’ (Reference Gioia, Patvardhan, Hamilton and Corley2013: 126). Exploring how identity endures, as a defined proposition, is not to deny the dynamic nature thereof but to underline its temporal aspects as identity unfolds. Identity ‘labels’ are stable, but the ‘meanings’ associated with those labels are malleable (Gioia et al., Reference Gioia, Schultz and Corley2000). In a similar vein, Cloutier and Ravasi (Reference Cloutier and Ravasi2020) found that identity claims are characterized by the internal structure of organizational means and ends, with the latter being more prone to change over time.

Similar to entrepreneurial framing, identity formation and change are shaped by social or cultural processes. Lok (Reference Lok2010) emphasized that any new identity is constructed through the reproduction and translation of new institutional logics. Vergne and Wry (Reference Vergne and Wry2014: 63) stated that categorical identities ‘shape actions by conveying cultural norms and expectations’. Glynn and Watkiss (Reference Glynn, Watkiss, Schultz, Maguire, Langley and Tsoukas2012) identified six cultural mechanisms that can make identity claims more familiar and appealing: framing, repertoires, narrating, symbolization and symbolic boundaries, capital and status, and institutional templates. Sugiyama, Ladge, and Bilimoria (Reference Sugiyama, Ladge and Bilimoria2023) discussed how cultural and demographic differences enable managers to construct distinctive ‘brokering identities’ that are useful in diversity training. Lounsbury and Glynn (Reference Lounsbury and Glynn2019: 60) considered entrepreneurial identity formation a cultural process that ‘aims to configure and reconfigure [the] bundles of meanings and practices that situate identity positions in and across institutional fields’. Identity change is thus processual, context-dependent, and socially sensitive to cultural legacy.

Often, identity change occurs because of the need to passively assuage the ‘identity threats’ caused by external, negative perceptions of an identity (Elsbach & Kramer, Reference Elsbach and Kramer1996; Ravasi & Schultz, Reference Ravasi and Schultz2006) or to actively address legitimacy imperatives or challenges, which encourage new organizations to acquire and mobilize resources from different audiences (Deephouse & Suchman, Reference Deephouse, Suchman, Greenwood, Oliver, Suddaby and Sahlin-Andersson2008; Mathias & Williams, Reference Mathias and Williams2018). Identity and legitimacy can be considered two sides of the same coin. A firm or a collective is legitimate to the extent that its identity, or its claims to identity, enables positive audience evaluation, thereby acquiring legitimacy and other resources (Clegg, Rhodes, & Kornberger, Reference Clegg, Rhodes and Kornberger2007; Fisher et al., Reference Fisher, Kotha and Lahiri2016; Jensen, Reference Jensen2010; Martens, Jennings, & Jennings, Reference Martens, Jennings and Jennings2007). A change in identity brings about a new ‘threshold’ of legitimation that marks a critical milestone in a venture's chances of survival and sustenance (Navis & Glynn, Reference Navis and Glynn2011; Zimmerman & Zeitz, Reference Zimmerman and Zeitz2002). Identity change can thus be seen as the performance of reframing, employed by entrepreneurs in response to opposition, threats, or emerging demands.

This emphasis on a ‘teleological’ view of change (Van de Ven & Poole, Reference Van de Ven and Poole1995), or ‘proactive process’ viewpoint (Radu-Lefebvre et al., Reference Radu-Lefebvre, Lefebvre, Crosina and Hytti2021), implies that identity change can be purposive and adaptive (Gioia et al., Reference Gioia, Schultz and Corley2000; Radu-Lefebvre et al., Reference Radu-Lefebvre, Lefebvre, Crosina and Hytti2021). Gioia and Thomas (Reference Gioia and Thomas1996), for example, examined deliberate identity change through proactive strategic change in US higher education systems. When there is a gap between a current and ideal (or desired) identity (Reger, Gustafson, Demarie, & Mullane, Reference Reger, Gustafson, Demarie and Mullane1994) or a disparity between a current (favorable) identity and a current (unfavorable) image (Dutton & Dukerich, Reference Dutton and Dukerich1991), this comprises a motive for people to enter a narrative episode or discursive struggle to influence or change identity. Abid et al.'s (Reference Abid, Bothello, Ul-Haq and Ahmadsimab2022) study of Pakistani counterfeit bazaars, for example, shows that market actors engage in reframing to develop a new moral identity for evaluating, justifying, and legitimating the consumption of counterfeit products. Identity change through reframing is possible, as identity is derived from repeated interactions with others and is collectively negotiated and shared through processes of sensemaking. Seidl (Reference Seidl2000) called this a ‘reflective identity’, since the interpretation of the meanings associated with the focal identity potentially changes over time following provisionally negotiated orders or shared understandings. Similarly, Marlow and McAdam (Reference Marlow and McAdam2015) referred to this temporal process as ‘reflective accommodation’, which is fluid and emergent. While reframing is a dynamic process, identity is, in parallel, open to the frequent revision and redefinition that enable the acquisition of new legitimacy resources (Golden-Biddle & Rao, Reference Golden-Biddle and Rao1997; Phillips & Kim, Reference Phillips and Kim2009). In contexts characterized by enduring demands for innovation and change, conscious efforts, through reframing, therefore constantly develop and update a legitimate sense of organizational identity that enables the scaling of new ventures.

Despite their potential to complement each other, the literature on identity change has developed distinctively from that on entrepreneurial framing/reframing. Observing identity change through reframing processes adds value to the literature in at least two ways. Identity change provides a triangulated view for examining the function and effectiveness of reframing as a cultural process that contextualizes entrepreneurship and innovation (Abid et al., Reference Abid, Bothello, Ul-Haq and Ahmadsimab2022; Durand & Khaire, Reference Durand and Khaire2017). This provision is feasible because reframing enables a change in identity, which is consequential for legitimacy (Brown & Toyoki, Reference Brown and Toyoki2013; Clegg et al., Reference Clegg, Rhodes and Kornberger2007; Phillips, Tracey, & Karra, Reference Phillips, Tracey and Karra2013). In addition, linking reframing processes with identity dynamics enables us to see not only how identity claims evolve over time but also, in the views of their audiences – shaped by various cultural values, why and how they evolve (Lounsbury et al., Reference Lounsbury, Gehman and Ann Glynn2019; Lounsbury & Glynn, Reference Lounsbury and Glynn2019). When entrepreneurs use linguistic frames to gain legitimacy among different audiences, they signal intentions to change their identity, which evolve to align with these audiences' expectations and beliefs. As entrepreneurial framing develops into reframing dynamics or continual frame shifting, the cultural frames or resources that entrepreneurs use to enable their actions are likely to create an ‘identity trajectory’ (Cloutier & Ravasi, Reference Cloutier and Ravasi2020), whether through refinement or substitution, which adapts to environmental contingencies.

Methods

Setting and Approach

Our empirical setting consists of the Chinese shan-zhai cellular phone entrepreneurs, whose dramatic rise and development from 1998 to 2011 were both economically significant and linguistically dynamic (Dong & Flowers, Reference Dong and Flowers2016; Lee & Hung, Reference Lee and Hung2014). China's cellular phone industry was born in Guangdong province in 1987. Motorola, Nokia, and Ericsson dominated the market until the late 1990s, with a combined market share of approximately 83% (Yuan, Reference Yuan2001, April 28). Domestic companies such as Eastcom, Kejian, Soutec, TCL, Chinabird, Panda, and Amoi then entered the market with the support of the government's license control. However, these companies foundered and were quickly replaced by illegal or informal players, known as shan-zhai. In 2007, the Chinese government changed its regulations to accommodate these shan-zhai players, which, although not blessed by the state, continued to scale and, by 2011, had a market share of more than 50% in China. Shan-zhai actors created market environments that appeared to recognize them. Our objective was to examine how Chinese entrepreneurs drew on various cultural resources to reframe their illegal activities, cultivate distinctive identities, and gain sufficient legitimacy to be accepted as serious global players.

The basic methodology in this study is the ‘naturalistic mode of inquiry’, a qualitative method in which insights are generated through grounded assessments, inductive procedures, and interpretive means (Lincoln & Guba, Reference Lincoln and Guba1985). This choice of design or approach was appropriate for four reasons. First, the informal nature of the shan-zhai sector implies a lack of reliable quantitative data – hence our reliance on fragmentary information and interview data to identify and triangulate our findings. Second, the processes and ways in which shan-zhai entrepreneurs have drawn on cultural resources constituted a complex social setting in which the causal dynamics and relationship between culture and innovation, agents, and audiences were not immediately apparent. Third, a primary motivation for this study was theory elaboration, a process in which one contrasts preexisting understandings with observed events to extend existing theory. Our analysis is thus instrumental, extending identity change through a cultural reframing perspective for a more contextualized explanation. Fourth, the study involves cultures, languages, and norms, leading to the significance of first-hand and contextually situated knowledge in this analysis. The aim is not only to capitalize on the Mandarin-speaking backgrounds of the two authors but also to provide a socially and culturally sensitive account of shan-zhai entrepreneurs (Plakoyiannaki, Wei, & Prashantham, Reference Plakoyiannaki, Wei and Prashantham2019).

Data Source and Analysis

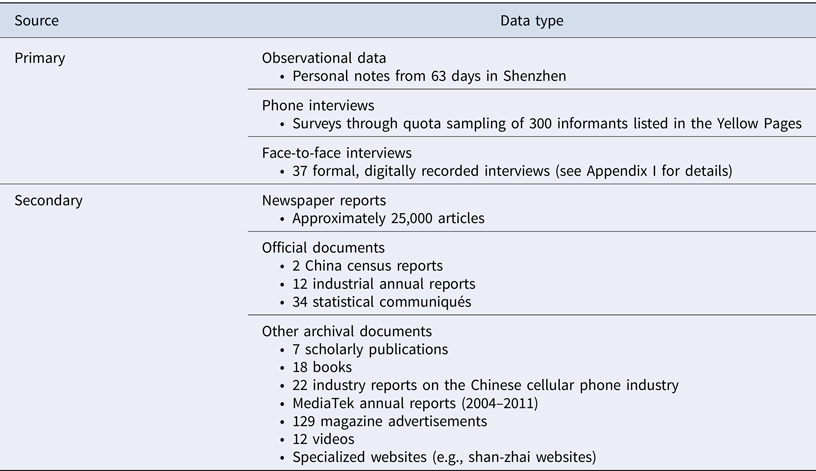

Table 1 presents the details of our primary and secondary data sources. First, we used ‘bricolage’ (Baker & Nelson, Reference Baker and Nelson2005) to mitigate the difficulty in accessing the field site, and collecting data through personal interviews. We collected approximately 6,000 phone numbers related to the cellular phone industry. Using criteria such as geography, business category, and advertisement size, we randomly chose 300 names from this list to cold call using SkypeOut. Approximately one-third of these calls were not answered or the numbers were invalid; another third resulted in an immediate hang-up. Of the remaining one-third, half were directed to company switchboards or reception desks, while the other half involved standard telephone interviews, ultimately leading to the identification of 11 prospective informants, who agreed to on-site, face-to-face interviews. We used our Taiwanese identities and our affiliation with a respected university in Greater China to reassure any respondents who were concerned about the sensitivity of this research project and to obtain access to the relevant field site.

Table 1. Data sources

As these interviews were completed, a snowball technique soon followed. We thus eventually conducted 37 face-to-face interviews (see Appendix I for details). Each interview, lasting 30–150 min, was digitally recorded and then transcribed to produce approximately 580,000 Chinese words in notes. We also conducted field observations and informal conversations, mostly with informal suppliers or dealers, to obtain more ‘situated’ details on shan-zhai activities. This led us to generate an additional 16,000 Chinese words in field notes.

In addition to these primary sources, we collected a variety of secondary sources, such as newspapers, statistical reports, scholarly papers, books, and industry analysis reports. This range of sources was important, as reports on the shan-zhai industry were often dissembling or deliberately misleading. For newspapers, we searched for the phrase ‘cellular phone’ to collect reports published from 1998 to 2011 from a Taiwanese database (the Udndata) and two Chinese databases (the China Sina and the CNKI).Footnote 1 This led to approximately 25,000 articles.Footnote 2 We did not consider querying the well-known term ‘shan-zhai cellular phone’ because its first appearance was not until 2007 – almost a decade after the industry began to take shape. A generic term such as ‘cellular phone’ thus enabled us to maximize our data sources and assess our results; this is a common challenge faced by researchers when examining informal or illegal activities. Taken together, these secondary sources coupled with the personal interviews enriched our contextual understanding and generated new questions for subsequent interviews and conversations with informants.

As we collected data, we inductively analyzed them following established techniques for naturalistic inquiry (Lincoln & Guba, Reference Lincoln and Guba1985) and grounded theory (Strauss & Corbin, Reference Strauss and Corbin1990). Despite the emerging, iterative, and cumulative nature of these qualitative processes, our data analysis consisted of four main steps.

We began by reading all the secondary sources and arranging the data chronologically to construct a database in Evernote, a note-taking software program. We created a tentative case archive and a chronological description of the industry's history. Through this analysis, we established a timeline of frame changes in the industry and the social and cultural contexts within which those changes took place. The interview transcriptions were then entered and coded iteratively in NVivo 10 software, which facilitates searching, inducting, and theorizing nonnumerical data. This round of open coding analysis generated more than 170 categories across the data, upon which we based the terminology of the informants to create in vivo codes. In the third step, we performed additional rounds of open coding and comparison by returning to our data to look for similarities and differences and reorganizing them into higher classifications. This round of coding generated more than 150 provisional categories.

Finally, we iteratively identified the relationships between and among these categories, which were mapped against the database we established in step 1. This triangulation of interview and archival sources enhanced confirmability and collapsed the provisional categories into a smaller number of ‘first-order codes’, which were then abstracted to a higher level, namely, ‘the second-order themes’. Using an iterative process, once again moving between theory and data, we refined, summated, and linked our second-order themes to identify the ‘aggregate theoretical dimensions’ that correspond to the reframing process for identity change (Gioia, Corley, & Hamilton, Reference Gioia, Corley and Hamilton2013). Appendix II presents the coding structure. Furthermore, we drew on the emerging patterns of linguistic framing (first-order codes) to find descriptive evidence that could quantitatively document change trends in reframing processes and underscore the validity of our findings. Next, we drew on the first-order codes, second-order themes, and aggregate theoretical dimensions, supplemented by the descriptive statistics, to develop Table 2 and Figure 1 and provide a ‘thick description’ (Geertz, Reference Geertz1973) – to structure our narrative and explain how entrepreneurial framing and identity have evolved in a culturally or socially constructed world.

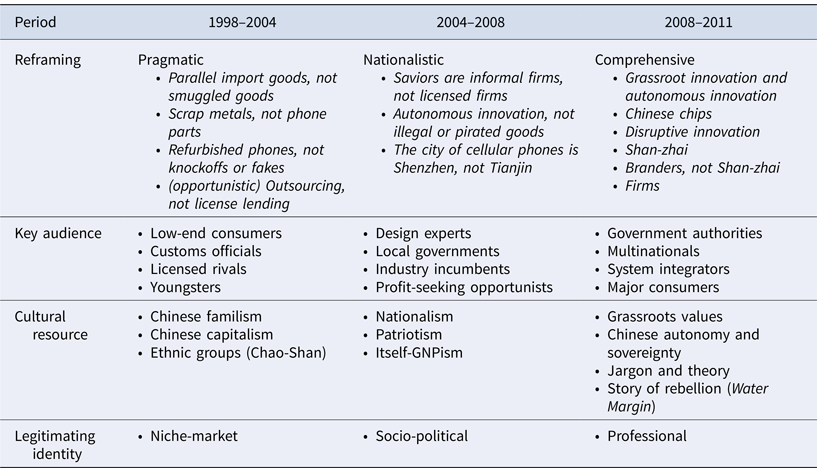

Table 2. Reframing Chinese Shan-zhai phones for identity change

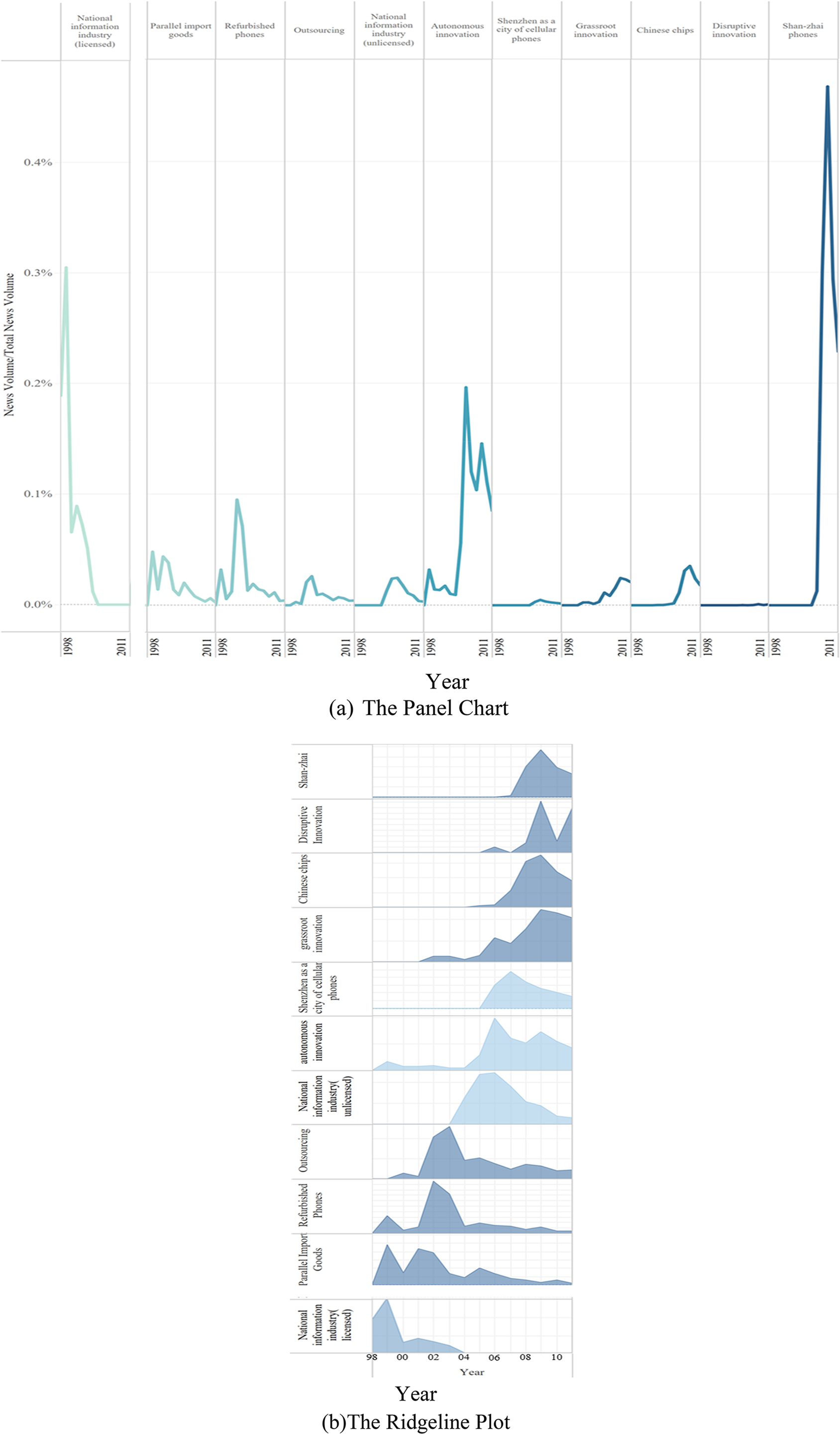

Figure 1. Frame dynamics. (a) The panel chart. (b) The ridgeline plot

Table 2 compares three phases of this reframing with regard to the notions of key audience, cultural resource, and legitimating identity, as these are central in building a contextualized explanation of how the Chinese shan-zhai entrepreneurs established substantive businesses. Figure 1 shows a dynamic process of framing in which terms are deliberately chosen to map our inductive process and case narratives and thereby create ‘visual graphical representations’ (Langley, Reference Langley1999: 700) that identify the patterns of frame sequences and compare phases. We used Tableau Software to create Figure 1 by counting the yearly number of news reports in the China Sina database. We manually examined the abstracts of these counted news items to remove any articles with obviously irrelevant material. For instance, we removed some shan-zhai articles that discuss mountain fastness in western China. To better explain our findings, we split Figure 1 into Figure 1(a) and Figure 1(b) – both plotted by taking the news volume in the category divided by the total number of news stories. Figure 1(a) refers to the panel chart that displays all the actual values for comparison; Figure 1(b) refers to the ridgeline plot that emphasizes the patterns of change in distribution over time.

Chinese Entrepreneurs' Identity Change Through Reframing

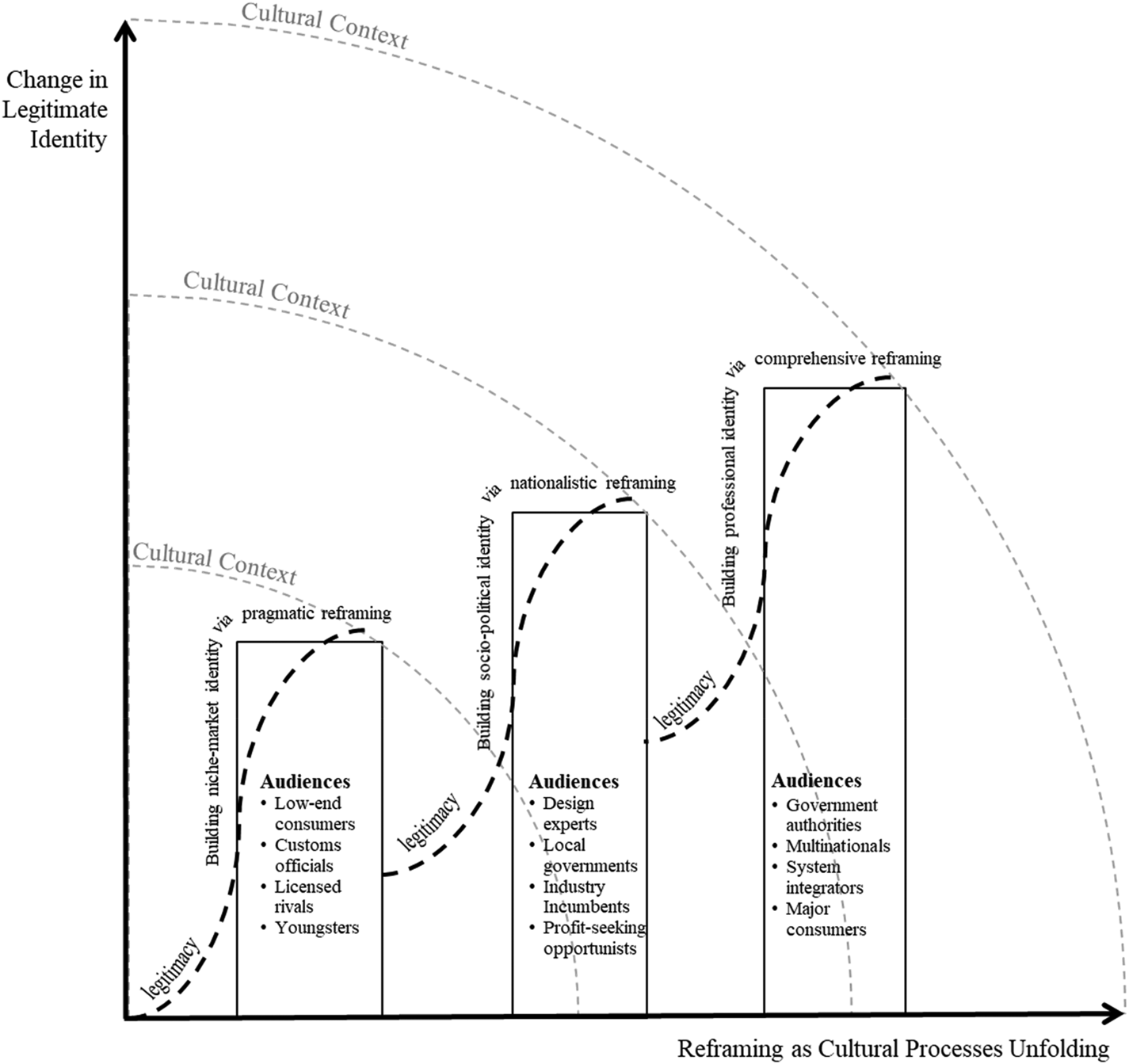

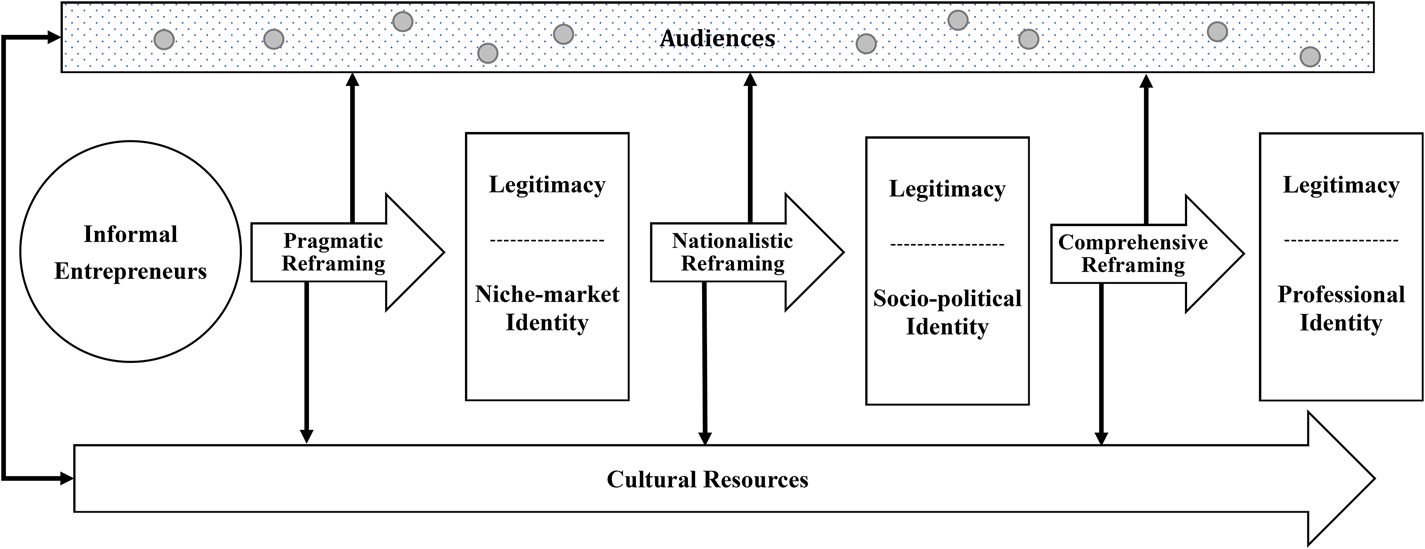

Based on Table 2 and Figure 1, we drew Figure 2 to shed light on how the Chinese shan-zhai entrepreneurs drew on cultural resources to reframe and grow their unblessed or illicit businesses. Our discussion covers three periods: (1) building niche-market identity via pragmatic reframing (1998–2004); (2) building socio-political identity via nationalistic reframing (2004–2008); and (3) building professional identity via comprehensive reframing (2008–2011).

Figure 2. Change in Shan-zhai identity and audience

We have thus identified three distinctive types of reframing: pragmatic, nationalistic, and comprehensive. ‘Pragmatic reframing’ involves thinking about a problematic or negative business in a more pragmatic or beneficial way. ‘Nationalistic reframing’ involves redefining the image of a new venture as a movement serving the best interests of its country of origin. ‘Comprehensive reframing’ involves a change in emphasis, from the socio-political aspects of a new venture with nationwide coverage to the plausible or scholarly aspects thereof with a universal or global orientation.

Moreover, we have identified three broad types of entrepreneurial identity – niche-market identity, socio-political identity, and professional identity – which are legitimately built through the above three reframing strategies (pragmatic, nationalistic, and comprehensive). By ‘market identity’, we mean a coherent market category, capable of legitimating business exchange relationships across particular industry sectors or market niches. ‘Socio-political identity’ is a general categorical position, capable of gaining socio-political legitimacy among nationwide public audiences. ‘Professional identity’ refers to a set of claims to a cosmopolitan culture or category associated with the enactment of a professional role, as viewed by multinationals and professional bodies.

Building Niche-Market Identity via Pragmatic Reframing, 1998–2004

During the beginning of the focal industry, its Chinese entrepreneurs were small-scale, resource-poor businesses that had just changed from being DVD, MP3, or pager manufacturers to cellular phone manufacturers. They could operate only as part of this less-developed or black market because of telecom licensing requirements. Most of them profited from simple, low-cost cellular phone assembly by using smuggled parts or avoiding taxes. These entrepreneurs, working on the fringes or outside of the law, availed themselves of cultural resources to reframe their illegal businesses in response to their audiences' interests to mobilize support and build new identities.

Two audience sources were particularly important – customs officials and niche consumers. To survive in the black market, these Chinese entrepreneurs needed to use inexpensive parts to produce inexpensive and competitively priced cellular phones. On the one hand, they needed to address customs questions, as most of these low-cost parts were smuggled from Hong Kong. On the other hand, they needed to persuade customers of the quality and value of their products to earn their trust.

The Chinese entrepreneurs developed the frames of ‘scrap metal, not cellular phone parts’ and ‘parallel import goods, not smuggled goods’ to affect custom evaluations or judgments. Although we are not able to show evidence for the significance of the term ‘scrap metal’ in Figure 1 due to the immaturity of the industry and scant public attention and documentation, this term is grounded in our fieldwork, with some framing agents proudly proclaiming this rhetoric. In addition, a national newspaper once reported how ‘Guangzhou Customs seized a trade mis-invoicing that covered up scrap metal smuggling (copper and aluminum). The total metal weight was 18,855 tons and the value was estimated at RMB915.4 million, which evaded RMB8.2 million in taxes’ (Yang, Reference Yang2003, December 17).

By this time, China had become an international scrap-recycling center. Every day, container ships carrying Western-generated e-waste arrived in Hong Kong's Victoria Harbor. From there, it was transported to Chao-Shan (part of the Southern China Coast Megalopolis) for extraction and reuse. Some of the scrap dealers bribed customs officials and entered the cellular phone industry by importing expensive cellular phone parts as scrap metal to Shenzhen. Framing these phone parts as scrap metal was a legitimate way for these informal businesses to facilitate bribery while keeping a low profile.

Under international pressure, the government occasionally intensified its anti-smuggling efforts and published ‘Chinese Customs’ to publicize its success.Footnote 3 Accordingly, informal companies insisted that their products were not contraband but parallel import goods, i.e., they were products that fell into the gray zone between legal and illegal. The neutral term, ‘parallel import goods’, connotes a high price-performance ratio. An estimated 40% of customers in 2000 were willing to buy parallel-import cellular phones despite knowing that they were unauthorized products (Zhu, Reference Zhu2000, August 28). As reported in newspapers, ‘There is no firm that does not use parallel import or smuggled goods’ (Hu, Reference Hu1999); ‘Parallel import goods are almost the same as authorized goods. The only difference is parallel ones are cheaper’ (Yang, Reference Yang2002, January 15).

The discourse of scrap metal and parallel imports was persuasive and legally sound because if this fraud had been exposed, customs could have avoided default by claiming that these imports had been illegal actions by the scrap dealers. In addition, tariffs and import fees for cellular phone parts are calculated by the piece, while scrap metal is calculated by the ton. The value of all scrap metal was also stated without any evidence supplied by the scrap dealers as to its true worth. Therefore, in competition with their branded and licensed rivals, scrap dealers could create competitive rents from their discourse on scrap metal. Compared to scrap metals, parallel imports delivered a more justifiable or coherent sense of market category, thereby reducing institutional pressures.

The rationale for reframing illegal products in other legal categories, such as scrap metals and parallel imports, may seem absurd or dishonest, but these frames were arguably made possible and constituted by China's cultural processes and meanings. Most of the smugglers or bribers defended their behavior. According to one business, ‘It is true that every industry is illegal to some extent and has some method of avoiding paying taxes’ (Interview, GM, WizTech, July 2011). The particular culture of Chinese family business values opportunistic and speculative growth and personal connections and tolerates bribery and other corrupt behaviors, especially through personal networks. Reframing the illegal as legal was culturally justified and empowered, as Chinese capitalism encouraged customs officials to look the other way when minor crimes were being committed. Appeasement was acceptable in contests over economic interests. In China, where relationships (guanxi) prevail, customs officials can easily tap into their local society's informal networks, which shape their actions. One of our interviewees indicated the following: ‘The Hong Kong Chao-Shan people is the largest and most influential group … . It's possible that even some customs officials are from Chao-Shan’ (Interview, Founder, Shenzhen Huatuo Technology, July 2011).

Concerns with economic activity also matter. After the 2008 Beijing Olympics, China's path to capitalism accelerated, generating even more economic benefits and market growth. Nevertheless, as Estrin and Prevezer (Reference Estrin and Prevezer2011: 49–50) indicated, ‘ … property rights in China were not formally recognized until 2004 and [the] legal independence of the judiciary has been poor … . There is a lack of legal infrastructure, shaky intellectual property rights, and weak contract enforcement’. Given this background, illegality may have become both subjective standard and linguistic issue – hence the considerable space for Chinese entrepreneurs to act as skilled strategic framers.

With the increased popularity of cellular phones, some entrepreneurs began to offer competitively priced products to overlooked or niche consumers, mostly young people in rural areas, who tend to emulate urban consumption patterns despite lacking the money to do so. The market was unstable, and customers complained about the inferior quality of these illegal, smuggled phones and the lack of after-sales service. Worse, the TV news coverage of these illegal cellular phones was often unflattering. In response, some informal players moved to present their products as ‘refurbished phones, not knockoffs or fakes’. This kind of product reframing not only disguised the negative and illegal image of their smuggled or counterfeit products but also legally presented their inferior products as an extension of a niche-market category. Refurbished phones, as secondhand goods (usually with a 14-day warranty), ‘were considered low quality but affordable’ (Xinhuanet, 2001, June 4), and, indeed, valuable, by low-end niche consumers.

In addition to customs officials and niche consumers, licensed firms were a critical source for audiences that enabled the construction of a legitimating identity. China's cellular phone industry was highly regulated at first, with the government using license control to protect and cultivate national players. However, the requirements to be granted a license were ambiguous. According to one statement, ‘the authority should strictly control licenses according to policies for telecom industry development and market demand’Footnote 4. This ambiguity left the authority sufficient space to protect its own interests. In addition, most companies authorized to produce cellular phones lacked the requisite capabilities. Nearly all of them simply imported completely knocked down (CKD) or semiknocked down (SKD) units from overseas, pasted on their own labels, and then sold them on the market. Although these government-supported and branded cellular phones were priced 20% lower than foreign cellular phones, their inferior quality quickly offset any price advantages (A-Gan, 2010: 156). Since the margins were poor and the costs (e.g., fees and bribery) of applying for a license were high, some licensed firms struggled to find alternative profitable business models.

As one of China's 49 licensed firms, Eastcom took a creative initiative, lending its license to a nonlicensed firm, Hua-Pu-Tao, to increase profit. Hua-Pu-Tao then used Eastcom's license to launch a Xiu-Te-Er cellular phone (Lu & Gao, Reference Lu and Gao2002, December 29). Other companies soon followed, leading to an increase in the number of purchasable licenses. Nevertheless, most licensed companies despised Eastcom's behavior. To lobby more licensed companies to lend their licenses, some informal firms adopted the language of ‘outsourcing, not license lending’ to justify exchange relationships and acquire resources.

This reframing strategy had two focal points. First, the unlicensed companies framed outsourcing as a legal activity found in every industry. Second, the unlicensed companies emphasized that their relationship with licensed companies was no different from any collaboration among foreign-branded cellular phone companies, such as Nokia, Motorola, or NEC (licensed companies), and their original equipment manufacturers (unlicensed companies) in producing cellular phones. Notably, the entrepreneurs' use of outsourcing as a frame of reference was insistent on opportunism on an ad hoc basis; there was a sense of legal ambiguity without formal approval by the state. Nevertheless, outsourcing cognitively helped legalize the illegal. As one business manager noted, ‘Big companies with licenses should share their licenses straightforwardly, right? … Actually, [this action] also reflected [that] there was a vital need in the market’ (Interview, Founder, Shenzhen Huatuo Technology, July 2011). Outsourcing was not just morally accepted but economically necessary. Sometimes, unlicensed companies were even framed as ‘high-quality manufacturers … .[who had entered] a strategic partnership’ (Qiu, Reference Qiu2006, August 1).

Thus, as evidenced by the increased number of market entries, licensed companies were glad to uphold the collaborations framed by the unlicensed companies. In another sense, license lending was a fully legal activity with immediate, pragmatic benefits. The licensed companies often charged 40–50 RMB (approximately US $4.3–6.00) per phone to use their licenses, increasing their earnings by 1.5–3 million RMB (approximately US$ 0.18–0.36 million) per year (Xing, Reference Xing2005, March 22). Interestingly, this development led to the irregular practice of two companies' names (that of the company lending the license and that of the company borrowing the license) appearing simultaneously on a single phone (Qiu, Reference Qiu2005, July 28).

With this access to license borrowing, many informal entrepreneurs gained a foothold in the quickly growing cellular phone market. Entrepreneurial framing evolved and was reconstructed with the launch, success, and prevalence of indigenous ventures clustered in Shenzhen. As a popular saying went, ‘a person with blue blood goes to Beijing, a person with a good resume goes to Shanghai, and a person with nothing goes to Shenzhen’. Success stories were aggregated into a storytelling episode that praised the shan-zhai business, attracting ambitious young people or entrepreneurs eager to ‘[raise] money from friends or relatives for a bet’ (Interview, Senior Manager, Foxconn, March 2012). The stories that empowered the ventures were enacted as much by industry fads and fashions as by Chinese history and culture, advocating audacious experimentation. In addition, the illegal nature of the industry implied that these entrepreneurs needed to operate through informal relationships, which, in China, are derived mainly from ethnic ties and hometowns (notably, Chao-Shan). In other words, such stories and narratives were translated into a framing strategy of utilizing informal and personal connections to form a collective endeavor and identity and fuel a shan-zhai industry. As one of our interviewees noted, ‘There are many legends in this industry. A cook or a barber could become a billionaire overnight … a real estate broker thinks he is smarter than a cook or a barber, so he thinks he should join the cellular phone industry’ (Interview, Founder, Shanghai Simcom, March 2012).

In conclusion, Chinese entrepreneurs used the terms ‘parallel import goods’, ‘scrap metal’, ‘refurbished phones’, and ‘outsourcing’ to reframe their businesses – from a problem of illegality to a solution and economic necessity. These terms all point to some degree of invariance in the merits or appeals of pragmatic preferences or benefits, namely, ‘pragmatic reframing’. Legitimacy came not only from the endorsement of customs officials and rural customers but also from the validation of licensed rivals and younger generations. We call this cultural process of meaning construction and resource acquisition ‘building niche-market identity’, as the Chinese's adoption of pragmatic reframing was oriented to the cultivation of a new distinctive identity capable of signaling a coherent niche-market category and building legitimate market exchange relationships with licensed giants.

Building Socio-Political Identity via Nationalistic Reframing, 2004–2008

This period witnessed the expansion of several unlicensed companies, such as Aux Telecom, Gionee, Coolpad, and K-Touch, which started moving from niche markets to compete directly with established national firms. These entrepreneurial ventures may have possessed a distinct niche-market identity, but they were built upon the image of counterfeit or, at best, ‘low-quality creative imitations’ (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Wu, Pechmann and Wang2019). They needed to improve and upgrade their technologies, moving from relying on simple assembly and external design to creating software solutions and sophisticated systems. This task of upgrading and creating was not easy; intellectual capital and technical knowledge were held by licensed companies, and the patents were owned by foreign companies.Footnote 5 Furthermore, as the unlicensed companies attracted attention, their legitimacy challenges became much broader, and society called into question their illegality, which aroused moral concerns and harmed economic health. To offer high-quality, economically beneficial products and construct new identities that appealed to wider social norms, the unlicensed companies needed to secure more resources among various audiences to overcome their liability of informality and create an exclusive image of innovation.

Four types of audiences were important resource providers: design experts, local authorities, industry incumbents, and business opportunists (e.g., real estate developers and provincial wholesalers). Design experts could help informal firms design and develop more sophisticated phones, thereby broadening their customer base. Firms also needed to consider the interests of their local authority, whose evaluation of new ventures or innovations was the path to win social and public recognition. The final audience consisted of industry incumbents or other business opportunists, whose regional aggregations created agglomeration economies and externality effects.

To attain support from these audiences, the Chinese entrepreneurs hailed them as ‘the saviors of the national information industry’. As shown in Figure 1 [the leftmost panel chart of Figure 1(a) and bottom ridgeline plot of Figure 1(b)], the national information industry, as a framing device, was advocated predominantly by the state-chosen, licensed firms in the early days of Chinese telecommunications. Reframing informal firms as industry saviors posed a challenge to this policy agenda. Since the 1990s, the Chinese government had chosen information technology as a strategic industry, with the objective of developing the country's technology and standards, including those for cellular phones. This industrial policy, reinforced through license control in telecommunications, drew waves of Chinese engineers, designers, and experts to work for domestic cellular phone companies. However, many companies that received government support went bankrupt only a few years later. The informal or black-market phone companies seized this opportunity, reframing their businesses as developed to echo the policy agenda and rescue the Chinese information industry. As one exemplar stated, ‘Vcall used to be an unlicensed company; now, it undoubtedly hopes to become a characteristic, soulful, national cellular phone brand’ (Zhao, Reference Zhao2008, September 9). Imbued with this sense of patriotic duty, the discourse of industry savior had an intrinsic appeal for government officials, who conferred political legitimacy and created the impression of public support. This support attracted the attention of design experts or design-house firms, who became more willing to join this bottom-up movement.

With the availability of design expertise, the Chinese ventures ceased to be low-quality imitators. Their confidence increased, and they began to cater to different market segments. This change in market appeal was less in terms of competitive and product strategy and more in accordance with a symbol of patriotism, which compensated the resource-disadvantaged shan-zhai entrepreneurs, enabling them to aggregate new resources and develop new products or services. The term ‘patriot’ even became a brand, as noted by public media: ‘Patriot is a cellular phone brand owned by [unlicensed] Beijing Huaqi Technology Company. The name, Patriot, reflects Huaqi's attempts to revive the national information industry and build Patriot as a global brand’ (Wang, Reference Wang2006). This growing impact led the Chinese entrepreneurs to reframe their industry – from selling illegal or pirated goods to a collective endeavor characterized by autonomous innovation. ‘Autonomous innovation’ – a term long used to explain China's national system of innovation – was a metaphor for defending and justifying shan-zhai's informal activities, including unlicensed operation, cloning, and piracy. Aiming to cultivate its own technology, the Chinese government described autonomous innovation as one of China's most important values and policy priorities. In line with government policy, the shan-zhai firms attempted to cast their technologies as autonomous innovations with the potential to transform China's cellular phone industry. To grow shan-zhai, then, was to pursue autonomous innovation, an endeavor economically and politically justified.

The other linguistic frame that articulated a new collective identity for shan-zhai businesses was the image of Shenzhen as the city of cellular phones, an appeal cultivated by the local authority that targeted a wide range of audiences, from industry incumbents to business opportunists (e.g., real estate developers and provincial wholesalers), all eager to profit from the booming shan-zhai industry. Although Shenzhen had been a fast-growing cluster, it was Tianjin that in the first years of the 2000s was formally recognized as the city of the cellular phone. This recognition was regionally intuitive and politically rationalized. Tianjin had become a significant cellular phone manufacturing base in which Motorola and Samsung had been centralized. In addition, Tianjin was near Beijing, where major cellular phone companies, such as Nokia, Pu Tien, and Datang, were headquartered.

State approval enhanced Tianjin's recognizable identity. Following the Special Topic Forum of the International Mobile Industry Exhibition (May 18-20, 2006) held in Tianjin, the conference report stated that ‘one in every four cellular phones sold in China and one in every ten cellular phones sold in the world was made in Tianjin; Tianjin is the city of cellular phones’ (Jin, Reference Jin2006). In August 2006, the Shenzhen Radio Association responded: ‘We can say one in every three cellular phones sold in China and one in every eight cellular phones sold worldwide were manufactured in Shenzhen; Shenzhen is the city of cellular phones, and not just in name only’ (Li & Lu, Reference Li and Lu2006, August 7). One month later, the association issued a visionary report, ‘An Overview on Developing Shenzhen as the City of Cellular Phones’, which arguably ‘gained support among the State Council, the standing committee of Shenzhen, the deputy mayor of Shenzhen, and other industry members’ (Lan & Wu, Reference Lan and Wu2007, January 24).

Following this report, the Shenzhen government, while joining local manufacturers, appealed to the National People's Congress to designate Shenzhen as the city of cellular phones. Meetings held by the central government confirmed that Shenzhen could compete with Tianjin. The rationale that underpinned the Shenzhen government's appeal to the central government was shaped by ‘itself-GNPism’, a characteristic of China's ‘fragmented authoritarianism’ model (Mertha, Reference Mertha2009), granting strong authority to local governments (Liu, Tsui-Auch, Yang, Wang, Chen, & Wang, Reference Liu, Tsui-Auch, Yang, Wang, Chen and Wang2019) and encouraging competition among local officials by virtue of economic growth across cities. To promote Shenzhen's competition with Tianjin was to validate this power structure, perpetuate longstanding cultural processes, and constitute entrepreneurial ventures as public‒private partnerships rooted in socialist regimes. With the status of their home cluster elevated and formalized, the social evaluation of the shan-zhai businesses was reinforced and enhanced.

In summary, Chinese entrepreneurs used the frames of ‘industry saviors’, ‘autonomous innovation’, and ‘Shenzhen as the city of cellular phones’ to reframe, justify and empower their businesses. Despite differing in language, all these frames share in common their emphasis on national interest and socio-political approval; thus, we call this process nationalistic reframing. Among the audiences that conferred legitimacy and other resources were design experts, local governments, industry incumbents, and profit-seeking opportunists. This change movement can be understood as the construction of a socio-political identity, as the acts of strategic framing, nationalistic reframing in particular, were oriented toward drawing on such cultural resources as nationalism, patriotism, and itself-GNPism to cultivate a new identity that appealed to a wider audience and was capable of gaining political support and recognition.

Building Professional Identity via Comprehensive Reframing, 2008–2011

This period was characterized by a much more extensive use of linguistic frames in legitimating and empowering the industry. As shown in Figure 1(b), the discourses of ‘shan-zhai phone’ and ‘autonomous innovation’ prevailed and dominated the scene. In terms of the absolute values shown in Figure 1(a), these two linguistic frames show two significant spikes across the period under examination. The peak in 2009–2011 was likely to have arisen from the ‘reinforcing loops’ (Weber, Heinze, & DeSoucey, Reference Weber, Heinze and DeSoucey2008) that occurred through the dynamic interaction of framing content and framing process to generate linguistic and industry momentum.

In October 2007, the Chinese government relinquished its license control over cellular phones, and most informal firms had been formally registered. By 2010, shan-zhai cellular phones held an estimated 40% market share in China (Jian, Reference Jian2009). International expansion soon followed. Despite their increased visibility and formalization, shan-zhai products were still associated with inferior quality, imitation, counterfeit, and, above all, intellectual property violation. Foreign-branded companies had been pressuring the Chinese government to crack down on shan-zhai phones, while mass or major customers remained dubious of their quality.

To promote their activities, entrepreneurs with humble and illegal origins had used the languages of grassroots innovation and autonomous innovation to reframe and enhance the value of their products. Their objective was to exclude the pirated technologies associated with shan-zhai cellular phones and advance their economic and social benefits for potential stakeholder groups, such as national governments, multinationals, system integrators, and major consumers.

The term ‘grassroots innovation’ was grounded in Chinese cultural life and in the Communist Party, which takes grassroots people across all social and economic classes seriously and advocates revolution from below. As a business owner noted, ‘If my design is for Nokia, I am the star. If my design is for shan-zhai, I am just the grassroots … Only a glimmer of light separates the star from the grassroots’ (Interview, Founder, Shenzhen Huatuo Technology, July 2011). With this cultural understanding, entrepreneurs claimed their products were neither imitators nor pirated goods but grassroots innovations that contributed to social justice and the alleviation of poverty. This reframing justified their humble origins and illegal past. For example, the commissioner of the Beijing Department of Cultural Affairs noted how the informal ventures had ‘reflected popular demand, and deserve[d] support’ (Xia, Reference Xia2010, February 1). These framing effects were more than national in scope. The discourse of grassroots innovation shared much of the scholarly notion or jargon of base-of-pyramid (BOP) businesses or markets (Prahalad, Reference Prahalad2005), which have been recognized in Western literature since 2000. This conceptual similarity created a cultural resonance that made the term ‘grassroots innovation’ appealing to foreign-branded firms and major consumers.

Similarly, the linguistic frame, autonomous innovation, also justified the shan-zhai phones but targeted a wider base. This frame peaked in popularity during the second period and diffused steadily across the third. The absolute value of the term ‘autonomous innovation’ is significantly higher than that of ‘grassroots innovation’. While the latter term may sound protective and defensive, autonomous innovation, as a framing device, provided a greater sense of confidence that effectively resonated with China's intention to build a self-reinforced telecommunication industry decoupled from Western technology. Such a policy agenda deliberately echoed national interests in telecommunications and was characterized by the network economy and increasing returns to scale. As a newspaper reported, ‘shan-zhai goods, somehow, are embryos … If the government could lead shen-zhai electronic products in the right direction and help illegal shan-zhai manufacturers become legal, autonomous [and] innovative ones, shan-zhai troops could help Shenzhen establish a global electronic and information industry base’ (Xia, Reference Xia2010, February 1).

The linguistic term ‘Chinese chips’ added to this emphasis on autonomous innovation, strengthening the ventures' affiliation with national autonomy. The framing agent was MediaTek, a Taiwan-based chip designer, which enabled the shan-zhai firms to break through R&D bottlenecks and achieve autonomous product innovations. For Chinese entrepreneurs, there was an enduring problem: developing an easy-to-use design platform that integrated functions and software. In the late 1990s, the solutions for hardware–software integration were controlled by multinational firms such as Texas Instruments, Qualcomm, Nokia, Motorola, and Philips, which charged exorbitant fees (including patent royalties and software royalties) that most unlicensed companies could not afford. Worse, these multinationals selected their certified partners, which, predictably, excluded the informal firms.

MediaTek provided an alternative solution. In the early 2000s, the dramatic rise of Chinese cellular phones, coupled with growing media coverage, drove MediaTek (then a DVD chipset maker) to enter the Chinese market. However, most licensed companies refused to use MediaTek's chips due to its lack of a track record. MediaTek then turned to the shan-zhai phone manufacturers, whose acceptance of its innovative chips was based not only on technological merit but also on cultural resonance and emotional appeal. In terms of technology, the MediaTek chip integrated the most critical parts of cellular phone design, chip design, software design, and hardware design into a turnkey solution. In a cultural sense, MediaTek framed its products as Chinese chips to win support among system integrators in the industry. As Mingto Yu, a spokesperson for MediaTek, indicated, ‘We, MediaTek, are a Chinese company, and must substantially support the cellular phone standards developed by the Chinese’ (Wang, Reference Wang2007). Senior vice president of MediaTek, Ji-Chang Hsu, added that ‘MediaTek is devoted to helping domestic cellular phone companies improve their ability to become world class and further dominate global market share’ (Pan, Reference Pan2006, December 21). By casting China as a great and home nation to obtain moral approval, MediaTek attended to the cultural frames or elements being reproduced. MediaTek's framing of Chinese chips was consistent with the relevant linguistic process, in which meaning construction was defined and enabled by China's autonomy and sovereignty and the historical values of ‘the spirit of brotherhood’ (Interview, Founder, Moko365, June 2011). As a newspaper reported, ‘The Chinese cellular phone brands also used MediaTek chips to fight against large foreign cellular phones … . and safeguard national honor as well’ (Cao, Reference Cao2008, August 15).

MediaTek's other notable linguistic practice was to use the theory of disruptive innovation (Christensen, Reference Christensen1997) to frame shan-zhai products. At a Merrill Lynch forum on March 17, 2009, Ming-Kai Tsai, MediaTek's chairman, declared ‘shan-zhai today, mainstream tomorrow’. With a master's degree in electrical engineering from a university in the United States and years of experience in semiconductors, Tsai was in a better position than his Chinese partners to imagine Western notions in terms of framing. While hosting Clayton Christensen on a visit to Taiwan, he emphasized that shan-zhai was, indeed, a disruptive innovation that had produced a ‘good-enough’ new market that would displace all high-end products: ‘I [Ming-Kai Tsai] think there is a language problem about shan-zhai, which gives you a negative image. However, the spirit behind it is disruptive innovation’ (Cao, Reference Cao2009, March 10). Early on, MediaTek had framed its products as Chinese chips and then moved to frame the industry as a disruptive innovation. There was a clear sense of evolving and expanding emphases within MediaTek itself to reach the broad field in which the company operated – from China, as home, to a global industry and innovation community that encompassed all the Chinese players.

Nevertheless, the prevailing frame of the Chinese ventures was shan-zhai, one of the most popular terms in China in 2008 (Li, Reference Li2009, January 16). This term was drawn from Water Margin (Shui-hu), a classic Chinese novel that describes how 108 outlaws gathered at Liang-Shan-Bo (Mount Liang), a literal shan-zhai, to rebel against a corrupt government. This had novel popularized the term ‘shan-zhai’ (Tse et al., Reference Tse, Ma and Huang2009). The novel also inspired the 2007 film The Warlords. In 2008, a university professor published a widely read book review about Shui-hu (Wang, Reference Wang2008). A Chinese television series with the same name debuted in 2009.

Chinese entrepreneurs drew on this cultural symbol to reframe their business as shan-zhai and align with the 108 bandits, albeit now fighting against the state's chosen winners and foreign monopolies. Gradually yet substantially, due to cultural embeddedness, the term diffused from the cellular phone industry to others (e.g., ‘shan-zhai netbooks’) as well as social spheres (e.g., ‘the shan-zhai alliance’). As a result, whenever resource-limited manufacturers started a business and moved into counterfeiting while entering a viable niche (disruptive), resorted to illegal means to do so (grassroots), or relied on their own strength (autonomous) while manufacturing inferior goods, all were eventually called ‘shan-zhai’.

As the public discussion shifted from shan-zhai phones to ‘shanzhailization’ and from substantial to abstract, shan-zhai cellular firms became part of a social and cultural phenomenon that was rarely challenged. In December 2008, China Network Television (CNTV) broadcast a special report on shanzhailization, claiming that ‘agriculture should follow the example of Da-zhaiFootnote 6 and that industry should follow the model of shan-zhai’. With this massive media attention, shan-zhai firms were able to particularize their claim that ‘shan-zhai leads innovation … not copycats or grassroots innovation’ (Interview, Founder, Shenzhen Huatuo Technology, July 2011).

Despite such redefinition and reinterpretation, shan-zhai may have remained a symbol of followership and opportunism, not modernity and cosmopolitanism. To compete with multinationals such as Nokia and Sony/Ericsson, some major shan-zhai firms repositioned or reframed themselves as ‘brand companies, not shan-zhai companies’ – a frame enthusiastically driven by the Chinese intention to pursue autonomy and cognitively embedded in the wider belief system of the global industry. An aggressive advertising campaign followed.Footnote 7

Some leading manufacturers established professional associations to enhance their political influence and reputation. One of the most important of these associations was the Shenzhen Mobile Communications Association (SMCA)Footnote 8, which provided the shan-zhai industry with business information and operational support and promoted narratives or discourses on formalization and standardization activities. In 2011, the association invited Milton Kotler, president of the Kotler Marketing Group, to ‘teach their shan-zhai members … [how to practically] build a brand’ (Interview, Deputy Secretary-General, SMCA, July 2011). The professionalization of the shan-zhai business was framed in positive terms, which contributed to the construction of comprehensive and generalized explanations for shan-zhai activities.

In conclusion, this period involved the use of terms such as ‘grassroots innovation’, ‘autonomous innovation’, ‘Chinese chips’, ‘disruptive innovation’, ‘shan-zhai’, and ‘branders’ in reframing these Chinese ventures to strengthen their resonance with the Chinese innovation system and global industry and thereby increase the likelihood of their diffusion. Although not contributing to the creation of a coherent story, these terms all point to some degree of invariance in the merits of comprehensibility, inevitability, or universalism. We thus refer to this act of strategic framing as comprehensive reframing. Here, legitimacy came from not only the support of the Chinese government and state-controlled media but also the recognition of multinationals, system integrators, and major final consumers. The emphasis on change or innovation was placed on the building of professional identity, as these collective linguistic endeavors (comprehensive reframing) were oriented to a wider audience or scope – ranging from the state or nation to the global community – and to achieving plausible explanations for the shan-zhai businesses that were neither strictly tied to cellular phones nor defined strictly in the Chinese context.

Discussion

Toward a Processual Model of Identity Change Through Reframing

We have examined how Chinese entrepreneurs drew on cultural resources to reframe their black-market origins as phone businesses into something that resonated with the value orientations of their audiences, leading to the cultivation of new identities and greater legitimacy for growth and wealth creation. Repeated reframing, through questions about ‘who we are’ and ‘what we do’ (Navis & Glynn, Reference Navis and Glynn2011) or constructing the ‘social categories that specify what to expect of products and organizations’ (Jensen, Reference Jensen2010: 39), generates linguistic dynamics that enable entrepreneurs to respond to the contingencies, uncertainties, and ambiguities inherent to new venture creation. Our case study has shown that a three-stage process underpins continuous reframing, identity claim, and legitimacy attainment with regard to the scaling or justification of an informal or problematic industry. This has led us to develop a generic, processual model of informal entrepreneur identity change through reframing, which consists of three sequential thematic phases and a set of general themes that contextualize these phases (Figure 3), as discussed below.

Figure 3. The process model of change in entrepreneurial identity through reframing across informal settings