Introduction

Policy-driven change is always challenging with no guarantee that the chosen policy solutions will be communicated well or understood, implemented as envisaged, or provide the intended outcomes. According to Hudson et al. (Reference Hudson, Hunter and Peckham2019, p1)

factors that shape and influence implementation are seen to be complex, multifaceted and multileveled with public policies invariably resembling ‘wicked problems’ (Rittel and Webber, Reference Rittel and Webber1973) that are resistant to change, have multiple possible causes, and with potential solutions that vary in place and time according to local context.

One tension in enacting policy-driven change is how new ways of working can achieve a balance between bottom-up development of local, context-specific approaches, and top-down, centrally determined policy solutions. This is particularly so for the implementation of new models of care and service integration. Here, there can be a multitude of variations and interpretations on how broad policy initiatives can be operationalised in practice, often underpinned by existing relationships and structural arrangements that are not straightforward to replicate or spread (Powell Davies et al., Reference Powell Davies, Williams, Larsen, Perkins, Roland and Harris2008).

One example is the New Care Model (NCM) Vanguard programme in England which emanated from the ‘The Five Year Forward View’ (FYFV, NHS England (NHSE), 2014a). This set out recommendations for the health service in England to create a more sustainable and integrated health and social care system by 2020-21, encouraging local areas to adopt new models of care through investment in new ways of working, technologies and workforce, as well as breaking down historical boundaries between primary, secondary and social care (Checkland et al., Reference Checkland, Coleman, Billings, Macinnes, Mikelyte, Laverty and Allen2019). Various strategies for implementing integration have previously been proposed which reflect the complexity and variety of institutional settings and objectives (Humphries, Reference Humphries2015). Overall however, while previous evaluations of integrated care have highlighted beneficial processes that need to be in place for optimal joint working (Glasby, Reference Glasby2017), in general they have not demonstrated the anticipated outcomes, particularly on reducing hospital use or cost (Sempé et al., Reference Sempé, Billings and Lloyd-Sherlock2019). The Vanguard programme explicitly set out to use locally defined and funded pilots to develop and trial approaches based on best practice and co-production, designed from the outset for national spread (NHSE, 2015a, p4). It was envisaged that these pilots would lead to a clear definition of new models and how they would operate, with associated frameworks and guidance being developed.

We use Matland’s (Reference Matland1995) ambiguity-conflict model to explore the aims and expectations of the Vanguard programme, and consider the relationship between top-down and bottom-up approaches to policy development in the context of integrated care. In this paper we use this term to indicate integration between different health sectors and between health and social care. We highlight that whilst ‘bottom-up’ development approaches have advantages, they may not support the development of ‘simple standard approaches and products’ (NHSE, 2015a, p4) aspired to by national policy makers, nor do they necessarily result in well-defined frameworks for others to follow. We draw also attention to the pressures coming from what was initially perceived as a permissive policy approach, encouraging bottom-up development, whilst at the same time requiring rapid scale and spread. We question the appropriateness of trying to develop standard products and frameworks under such conditions.

Our aim for this paper is therefore, through Matland’s (Reference Matland1995) model, to shed light on how future programmes for large-scale policy implementation initiatives could be crafted to take account of the environment of implementation and render ambitions more realistic. To achieve this, the paper draws from ongoing research into the Vanguard programme (2017-2021: Policy Research Programme funding) and its associated support programme. We first briefly describe the policy making process, introduce and justify the use of Matland’s model, and describe our methods. We then set out the nature and goals of the Vanguard programme, followed by an examination of these goals to explore goal ambiguity and conflict. Evidence from our research participants is used to provide insight into how the goals played out during initial implementation and help us to examine the extent to which the programme, as established, embodied these. We conclude with some lessons for large scale policy initiatives.

Policy making and its implementation

Ideal type models of the policy-making process envisage a rational ordered approach, in which the identification of a problem is followed by an analysis of the potential alternative solutions; evaluation of the pros and cons of these; and implementation of the chosen policy option followed by an evaluation of the outcomes of that policy (Parsons, Reference Parsons1995, p77). However, the reality is far more complex. Previous research has explored a wide range of factors which influence the policy process, including: policy transfer between contexts (Evans and Davies, Reference Evans and Davies1999); the existence of policy ‘sub-systems’, where interest coalitions, ideas and policy actors interact (Sabatier and Wible, Reference Sabatier and Wible2014); media and other influences on defining the problem (Downs, Reference Downs1972); the role of think tanks in understanding problems and suggesting solutions (Stone, Reference Stone2013); and the role and influence of epistemic communities of experts (Haas, Reference Haas2009).

Alongside these contextual factors, the policy literature explores ‘top-down’ and ‘bottom-up’ approaches to implementation, highlighting differences between those promoting a locally driven approach within a specific context (Parsons, Reference Parsons1995, p468) and those advocating central control (Parsons, Reference Parsons1995, p465; Hogwood and Gunn, Reference Hogwood and Gunn1984). Barrett and Fudge (Reference Barrett and Fudge1981) argue that implementation is best understood as a policy-action continuum, along which an interactive and negotiative process occurs over time between those seeking to put a policy into effect, including those in control of ideas and resources, and those upon whom action depends.

The focus of our research is the implementation of the Vanguard programme. Matland’s (Reference Matland1995) ambiguity-conflict model has been widely used to analyse policy implementation, focussing on describing and analysing the relationships between policy and practice, implementation success or failure, and has generated valuable lessons relevant to policy implementation (Paudel, Reference Paudel2009). We therefore explored Matland’s theory as an appropriate lens through which to view what was happening in our study. Matland (Reference Matland1995) summarises top-down and bottom-up models of policy implementation, and argues that ‘top-downers’ have a strong desire to present prescriptive advice, while ‘bottom-uppers’ place more emphasis on describing what factors have caused difficulty in reaching stated goals. He reflects on what ‘implementation success’ means, suggesting a number of possible definitions:

….agencies comply with the directives of the statutes; agencies are held accountable for reaching specific indicators of success; goals of the statute are achieved; local goals are achieved; or there is an improvement in the political climate around the program. (ibid p154)

Matland (Reference Matland1995) proposes that to assess policy success it is necessary to understand the goals of those developing a specific policy, and the extent to which those goals are based upon explicit expressions of values. He suggests that approaches to implementation should be different, dependant on the nature of the goals of the specific policy. Matland’s model classifies policies along two axes: conflict and ambiguity. Here, conflict refers both to potential conflict between goals, and conflict in how the goals are met. As most policy programmes have multiple associated goals, this element refers to how far either the stated goals are incompatible with each another – i.e. if one goal is achieved another becomes impossible – or how far the means of achieving those goals are incompatible. Conflict in Matland’s model does not necessarily mean conflict in its everyday sense of overt opposition or political disputes. Therefore a policy might have broad political support, but still be high in conflict because the goals as set out are incompatible with one other. For example, Hordern (Reference Hordern2015, p3) suggests ‘where different parties need to work together and do not see mutual benefit, or agree on a vision, then conflict may arise’.

The second axis, ambiguity, refers to how far the goals of a policy are clear. As with conflict, Matland (Reference Matland1995) suggests that ambiguity should not necessarily be seen as a flaw. He suggests that ambiguity can be useful, enabling agreement both at the legitimation and the formulation stages. Two types of ambiguity are suggested: ambiguity of goals (what is being aimed at) and ambiguity of means (different ways of achieving the goals).

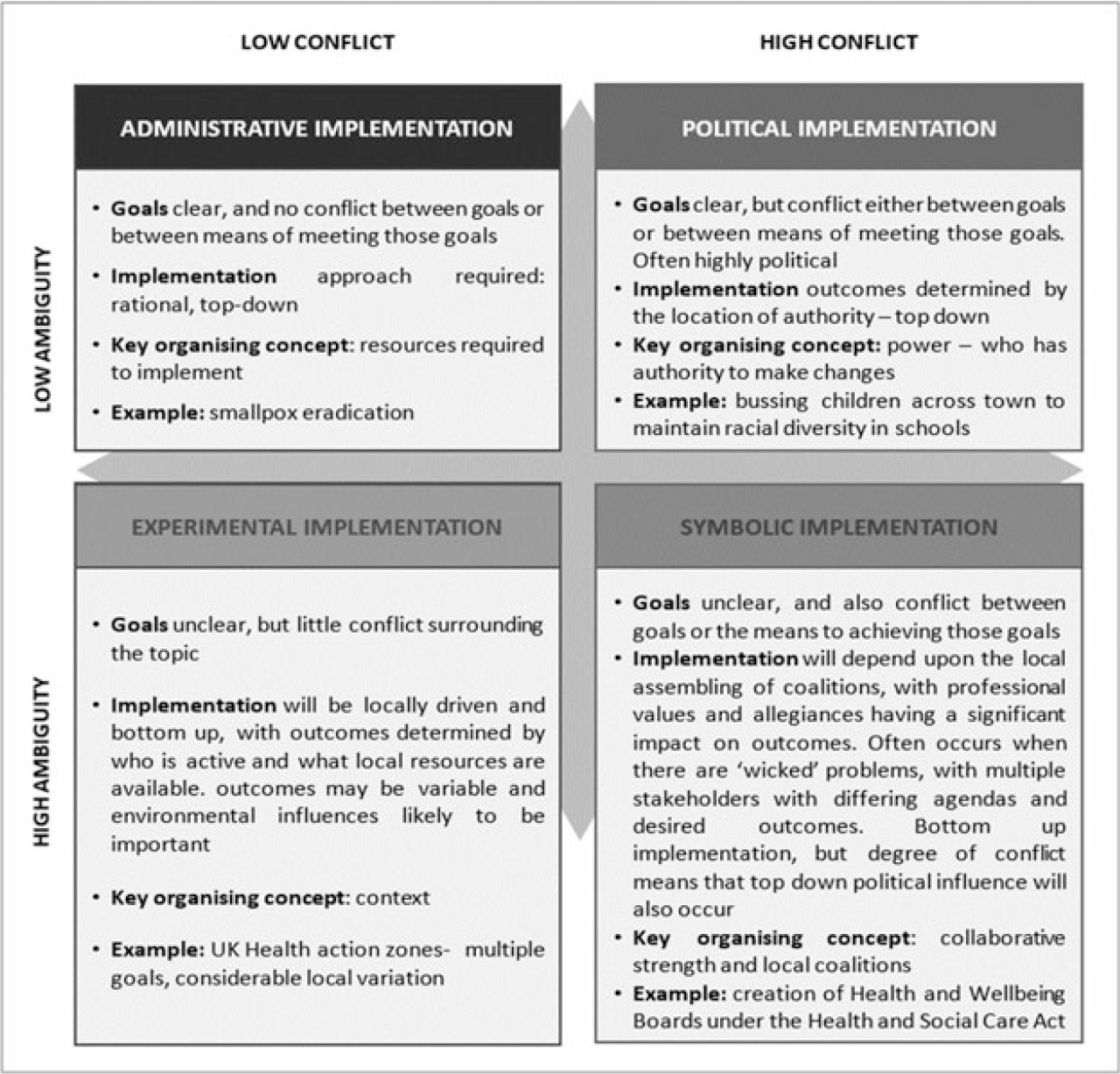

Matland proposes a classification of policy programmes according to goal ambiguity and conflict, suggesting that approaches to implementation should vary along these axes. Figure 1 illustrates Matland’s ‘ideal types’ of policy and associated implementation approaches.

Figure 1. Elaboration of Matland’s model of conflict, ambiguity and implementation (adapted from Matland in Checkland et al., Reference Checkland, Coleman, Billings, Macinnes, Mikelyte, Laverty and Allen2019)

For our policy example, this framework usefully distinguishes between lack of policy clarity, which is often used as an excuse or explanation for policy failure (e.g. Ward and Parr, Reference Ward and Parr2011) and lack of coherence in policy intentions. Thus, in understanding this significant and expensive policy initiative, it is important that distinction is made between issues arising out of the latitude allowed to implementers, and those arising out of any incompatibilities between differing policy goals. As a complex policy, this latter area is particularly important to explore.

Matland’s work however, is not exempt from criticism, largely stemming from a perceived lack of common understanding of what is meant by ‘implementation’ in this context. For example, it is often used to characterise the implementation process, the output from a given programme and the outcome of the implementation process (Winter, Reference Winter, Peter and Pierre2003). Paudel (Reference Paudel2009) also notes that the framework is restrictive in that it does not explain why implementation occurs, nor does it predict how implementers are likely to behave in the future. Top-down and bottom-up perspectives such as Matland’s raise debate on the purpose of implementation analyses: are they prescriptive, descriptive or normative? (Barrett, Reference Barrett2004). Saetren (Reference Sætren2005) argues that the top-down perspective could be regarded as prescriptive – what ought to happen – whereas the bottom-up focuses on description of the implementation process. Therefore, both perspectives could be seen as confusing in how normative, methodological and theoretical aspects are seamlessly and indistinguishably intertwined (Paudel, Reference Paudel2009).

Despite these criticisms, Matland’s (Reference Matland1995) ambiguity-conflict model has been useful in enhancing understanding of the policy implementation processes and outcomes across a wide range of public policy fields including disability policy (Cohen et al., Reference Cohen, Timmons and Fesko2005), social and welfare policy (Hudson, Reference Hudson2006) and public education policy (Hordern, Reference Hordern2015). We use it here, as the two axes of conflict and ambiguity are particularly salient in this case; and our analysis allows us to draw more general conclusions about the implementation of complex policy programmes.

Design and Methods

Our focus is on the first stages of our research programme (Checkland et al., Reference Checkland, Coleman, Billings, Macinnes, Mikelyte, Laverty and Allen2019), which explored ways in which the NCM Vanguard programme was conceived, introduced and operated, and enabled by the associated support programme. There were two parts to the research reported here. First, we carried out an analysis of publically available documents in order to understand the goals of the Vanguard programme. These included the FYFV (NHSE 2014a), its associated planning guidance (NHSE, 2014b), and several documents published during 2015 by NHSE, including further planning guidance and support programme documentation (NHSE, 2015a, 2015b). During 2016 documents were released on emerging frameworks for three of the suggested new models of care (NHSE, 2016a, 2016b, 2016c) alongside documentation describing the evaluation strategy (NHSE, 2016d). We have also taken into account other sources of evolving evidence (e.g. National Audit Office (NAO), 2018; Improvement Analytics Unit (IAU) reports) over the same timeframe. Identified documents were closely read by the research team and the central messages extracted and agreed. This analysis focused upon statements within the documents which set out what the Vanguard programme would or could achieve. Attention was paid to both outcome and process goals, and these were discussed by the team.

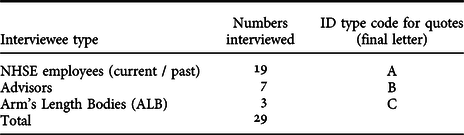

This informed the questions asked of 29 national level interviewees, exploring perceptions of the programme aims and goals in more depth. We used standard interview scripts for each interviewee type to ensure consistency and coverage. See Table 1 below for details of interviewees with coding details for quotations.

Table 1. Interviewees

Table 1. Interviewees

Interviewees helped us understand the aims and goals of the programme and test out our initial understanding from the documents. They provided descriptive accounts, along with their assessment of the value of each element of the programme and its support and any changes made during the programme’s lifetime. With the National Vanguard support team (including programme leads, support stream leads, advisors and those providing support to the programme), we sought to elicit narratives helping us to understand the development and subsequent operation of the programme and its associated support. With Arms Length Bodies (ALBs) we discussed their overall approach with Vanguards. We also explored national perspectives on how learning from the programme was communicated and used with all respondents.

All interviews were transcribed verbatim, and analysed using NVivo qualitative analysis software 11. A priori codes were developed from our initial areas of interest, including: programme goals; elements of the support programme; the Vanguard selection process; the logic modelling process; the different Vanguard models; the wider context, including regulation and relationships between providers; approaches to evaluation; and intended and claimed beneficial outcomes. In addition, new themes identified in the data were discussed and agreed amongst the team. Direct quotations illustrate points being made and allocating each an ID code (see Table 1) preserves anonymity of the interviewees. The project gained ethical approval via Manchester University (Ref 2017-2113-3253).

Findings

This section explores two main aspects of our data analysis using Matland’s (Reference Matland1995) framework; firstly the NCM Vanguard Programme and its support mechanisms; and secondly, the goals of the programme which revealed different aspects of implementation and support.

The NCM Vanguard programme and approach to implementation

The Vanguard programme is an example of a policy programme designed to use and emphasise bottom-up development processes, facilitated by an extensive and costly national support programme, as described by this interviewee:

It was a bottom-up rather than a top-down thing, so the idea was to get the Vanguards to say what it was that they were doing, and then support them in doing what they’re doing and trying to break the barriers down that were stopping them from doing what they wanted to do. Almost trusting them that they knew what the ideas were, and it wasn’t that they needed telling from above (ID006A).

At the outset it was argued that ‘one size will not fit all’ across the different model types (NHSE, 2014a, p9), and that diversity in developing local solutions would be necessary and encouraged. Apart from agreement that there should be a focus on integration, empowerment of patients and community engagement, there were no clear definitions provided at the outset of what the elements of each model should be. Therefore, whilst the FYFV (NHSE, 2014a) set out a clear direction of travel in terms of greater integration between all forms of healthcare and the provision of more care out of hospital, there was substantial flexibility – ambiguity – in terms of what care might look like or be delivered in the future.

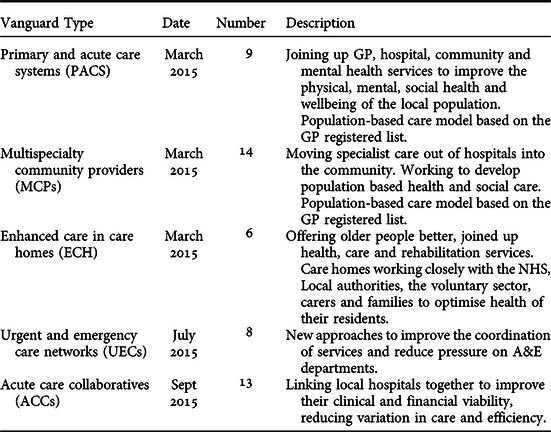

Among the 50 Vanguards that were funded, there was variation along a continuum from those already making good progress with service transformation, to those just beginning the process. Five model types were developed (described in Table 2): Primary and Acute Care Systems (PACS); Multispecialty Community Providers (MCPs); Enhanced Care Homes (ECHs); Urgent and Emergency Care (UECs); and Acute Care Collaborations (ACCs) (NHSE, 2015b). Our research focused largely on PACS, MCPs and ECHs, as these three types of NCM Vanguard were established to address broadly similar issues, in particular extending care outside hospitals. UECs and ACCs had a specific focus on emergency and acute care (NHSE, 2015b p6).

Table 2. Types of Vanguard

The Vanguard policy encouraged greater integration between different parts of the health system and with social care and the voluntary sector. As the programme was driven from NHSE, our data naturally has a focus on health, but we provide insights about the wider health and care economy where available.

Table 2. Types of Vanguard

Despite occurring at a time of austerity affecting public services in the UK, an NAO (2018) report estimated the additional funding provided to the Vanguards to be approximately £329m in direct investment between 2015 and 2018. It was intended that the associated well-funded support programme (approx. £60 million) would increase the chances of the policy being implemented successfully and enable the development of products and frameworks to support spread and scale of the new models of care. The support programme aimed to combine technical expertise with learning from peers (NHSE, 2014b, NHSE, 2016d). Extra funding and support was seen as a major motivating factor for applications to the programme, as at this time very little discretionary funding was available in the NHS.

A variety of networking events and opportunities were organised using multiple mechanisms to support knowledge exchange and the sharing of learning from bottom-up ‘testing out’ of approaches, with the intention of encouraging the development of common, scalable approaches. This happened at the geographical level (within the three defined regions, often facilitated by account managers, employed by NHSE), within groups implementing the same model types (MCP, PACS, ECHs), and at nationally supported events, webinars and online.

Our analysis of the relevant policy documents demonstrated that the NCM Vanguard programme, as with other complex policy programmes, contained a number of different goals (Checkland et al., Reference Checkland, Coleman, Billings, Macinnes, Mikelyte, Laverty and Allen2019). These included:

-

testing out approaches to integrating care across organisational boundaries;

-

testing approaches to implementing these new ways of working, including overcoming relevant barriers and exploring ways of supporting innovative activity;

-

using learning to develop replicable care design frameworks and ‘standard approaches and products’ which could then be adopted by other areas;

-

using learning from the ‘models’ to develop common approaches to implementation that could themselves be spread.

It was intended that the 50 Vanguards would drive the process, helping facilitate the national (co)production of products and frameworks which could then be scaled up and rolled out at pace across England to meet the challenges set out in the FYFV (NHSE, 2014a, NHSE, 2015a, p4):

‘Over the next year we will co-design a programme of support with a small number of selected areas and organisations that have already made good progress and which are on the cusp of being able to introduce the new care models set out in the Forward View. Our goal is to make rapid progress in developing new models of promoting health and wellbeing and providing care that can then be replicated much more easily in future years. Achieving this goal involves structured partnership rather than a top-down, compliance-based approach’ ( NHSE, 2014b , p4).

To help understand impact, local evaluations were carried out as part of the NCM Vanguard programme (NHSE, 2016d), to establish if the developing models and different ways of working were making a difference to outcomes. Various external analyses were also undertaken outside the programme (e.g. NAO, IAU).

The Vanguard programme can be interpreted, in Matland’s (Reference Matland1995) terms, as high in ambiguity, with the goal of what the new models of care would look like left deliberately vague, at least at the outset, and an explicit argument made that ‘bottom-up’ design would best allow the development of appropriate local solutions, focused around integration and more effective and efficient service use (NHSE, 2014a). At the same time policy and guidance documents clearly set out the ambition that, via a strong support programme, local implementation experiences would be drawn together to solve problems and design definitive ‘care models’ to be easily replicated and spread. These two sets of goals attracted little opposition and were promoted as self-evidently compatible (i.e. low conflict) with each other (NHSE, 2014a), with the support, evaluation and feedback loops built into the programme intended to enable the rapid refinement of a set of defined care models, via ‘standard approaches and products’ (NHSE, 2015a, p4). However, the path from local innovation to standard models proved to be neither clear nor free from conflict.

Goals of the programme and national support

In this section, we unpack the goals (set out above) of the NCM Vanguard programme, using Matland’s (Reference Matland1995) framework to highlight helpful aspects of its implementation and support described by interviewees, as well as some clear contradictions and tensions within the policy. First, we look at the goal of testing approaches to integrating care across organisational boundaries. Generally, interviewees considered the programme in positive terms and as being genuinely ‘bottom-up’ and facilitative, allowing the trialling of new ways of working in local contexts. This resulted in significant local engagement and enthusiasm:

… externally I think it has done a combination of disrupting the system by creating something different and thinking different, so outside when I talk to people, they’re very excited about New Care Models, they’re very excited about the changes, and they say, well, we’re doing this and this, we’re doing that, and they’re taking on elements of what we’ve described here. The other half to that is I think not only is it disruptive, but it’s actually given realistic hope to people. So one of the things I would reflect on is how grim it is, and people tell me about how hard their jobs are and how grim it is, and how little fun they have at work, and then what I then hear when people talk about this is they’re alive, they’re excited, they’re reconnecting with why they came to work in the morning [ID007A].

The built in ambiguity and bottom-up nature of the programme was felt to be both appropriate and refreshing, and created early enthusiasm:

There was an attempt to do something differently compared with previous transformation programmes and there’s a lot that seems promising in the approach that was taken [ID 030B].

…generating a bit more energy and enthusiasm than we normally manage to do for any of our centrally driven Initiatives [ID027B].

This initially supported an approach which appeared low in conflict, despite the high levels of ambiguity, with respect to the programme goals. In Matland’s (Reference Matland1995) model this is defined as ‘experimental implementation’ (see Figure 1), where piloting new ways of working within a specific local context is encouraged. However, a high proportion of the Vanguards were funded in respect of developments that were not new, with 16 of 23 respondents to the National Audit Office survey reporting that their Vanguard included existing as well as new initiatives; and 6 of these 16 sites had been part of an earlier initiative, the Integration Care Pioneer programme (National Audit Office, 2018). This suggested less innovation, but instead the opportunity to gain funding and support to accelerate existing programmes of work.

Second, we consider the additional, unambiguous goal of testing and refining approaches to implementing the new ways of working, including overcoming relevant barriers, exploring ways of supporting innovative activity and distilling and defining a definitive ‘model of care’ in each category. In the early stages of the programme, respondents told us that there was an explicit focus upon allowing local areas to develop as they saw fit, with the support programme intended to respond to local needs and produce relevant support and guidance in response to local experiences and developing needs. This is in keeping with Matland’s ‘experimental approach’ to implementation.

[… ]it was, you know, trying to empower the local leaders and the clinical leaders, and nationally sort of being subservient slightly to the local leaders in terms of them telling us what support they wanted and, you know, us saying at a national level, we are here to do the things that only need doing once and to escalate your national issues, but we’re not actually here to tell you what to do [ID008A].

However, this wide ranging and permissive start to the programme changed over time, with attempts made at national level to decrease policy ambiguity. Whilst initially Vanguards were encouraged to develop and judge progress against a set of locally appropriate outcome measures, over time they were made subject to a progressively narrower set of indicators of success. These focused upon measures of system activity such as emergency admissions, Emergency Department waiting times and hospital bed days. Ongoing funding after the first two years of the programme was made contingent upon improvement in these measures, even though they were not initially stated goals for the programme. By spring 2017, NHSE made claims as to the success of the programme using this small number of metrics (emergency admission growth, in particular). This was a source of frustration to those working locally in the Vanguard sites, as these nationally set targets were not always the primary local goal of the changes being implemented. Moreover, reducing hospital activity is a lengthy complex process, and local Vanguards felt that they were not a fair measure of short term progress. This established a conflict between perceived suitable measures of success at the national and local level and the speed at which local sites were expected to demonstrate beneficial change.

By year three they’re being asked for hard outcomes which, some of them haven’t even set up some of the programmes by which they’re going to produce the outcomes that we want, and that was the biggest tension [ID025B].

The pressure to quickly show positive results to secure ongoing funding also led Vanguards to feel that they needed to develop and showcase ‘good news stories’ and prove positive change over very short time periods of time. This created a tension between showing good progress within the programme and the need to gain an accurate understanding of whether and how particular changes to services and ways of working were beneficial and sustainable. While evaluation was built into the programme, timescales for implementation, change and evaluation operated very differently and it was often difficult to detect change over these time frames. Accounts that emphasised long term meaningful, sustainable ‘bottom-up’ change could therefore be in direct conflict to those which required the demonstration of quick results to satisfy the political needs associated with the programme.

Indeed, whilst the goals of the programme, as set out, and the experience of Vanguard sites in the early stages of the programme both implied a longer term, developmental and iterative programme – ‘experimental’, in Matland’s terms – in practice, the programme was very quickly declared a success:

Everything has happened unbelievably quickly. Commitments [were] made to roll-out work … within about three, six months of my arrival. Before there was, really, a shred of evidence that this new way of…I mean this is before we even knew what a…if an MCP was an actual thing. Were the Vanguards doing something that was unique and different, or just a collection of things that sounded good to do, because of that sort of logic model thing? So, that commitment was made, just unbelievably early, but by quite senior people… I would argue, far too quickly… [ID004A].

Thus, in 2016, it was announced that, despite no defined models of care having been developed, the programme would be extended across the country via the development of ‘Sustainability and Transformation Partnerships’ (STPs) (NHSE, 2015c). Each area of the country was required to produce an ongoing plan which, amongst other things, set out how the Vanguard NCMs would be spread locally (NHSE, 2015c p16). In the last year of the programme, focus was already seen to be moving away from the Vanguards towards the development of Integrated Care Systems (ICSs), building upon plans of STPs. The National Programme Director left towards the beginning of the third year of the programme, and those involved with supporting the programme nationally started to look for new roles, as one interviewee stated:

By year 3, attention had moved onto the next shiny thing… [ID013A].

Rapid roll out of pilot programmes is not new, and Ettelt et al. (Reference Ettelt, Mays and Allen2014) suggest that many previous healthcare policies have been introduced quickly and rolled out before evidence of efficacy was available. In this case the rapid commitment to wider roll out was potentially at odds with the stated goal of using the bottom-up implementation process, alongside a strong support programme dedicated to capturing and distilling relevant learning, to develop replicable care design frameworks and ‘standard approaches and products’ which could easily be adopted elsewhere. Developing ‘simple products and frameworks’ (NHSE, 2015a, p4) proved challenging, not least because of the complexity of trying to classify the diverse work being undertaken in the Vanguards. In 2016 the published ‘frameworks’ for MCPs, PACS and ECHs (NHSE, 2016 a-c) remained non-specific and process-dominated.

Thus, as shown above, the Vanguard programme was originally presented as high in ambiguity – with an explicit intention to allow bottom-up development of new approaches to care – and low in conflict, with guidance and policy documents depicting a straight forward trajectory towards the definition of blueprints which other areas could follow. This was associated with what was initially an experimental implementation process, as Matland would advise. However, our interviewees told us that the goal of allowing bottom-up development of local approaches, whilst helpful in generating local enthusiasm and engagement, was potentially incompatible with the goal of distilling out standard approaches and models:

So there’s an element of how do you construct some prototyping and to what extent you get the design principles versus more detailed operational blue printing as you start to think about wider spread of change. A personal reflection of mine is that I think on balance in this really tricky challenge of how do you unlock clinical engagement and energy versus generate reproducible models? I think we probably veered too much towards […] the local tailoring and insufficiently tightly towards the construction of more standardised methods that multiple sites then were trying to trial [ID012A].

This suggests that the Vanguard programme was, in Matland’s terms, a high ambiguity high conflict programme, with one set of goals – of a bottom-up, developmental learning programme – incompatible with the goal to develop clear models of care which could be spread. Matland (Reference Matland1995) suggests that such a programme requires an implementation approach which foregrounds local coalitions and alliances, rather than an experimental approach which might emphasise evaluation and objective assessment of programme success. This interpretation is perhaps reinforced by the fact that, whilst a strong evaluation programme was established for the Vanguard programme (NHSE, 2016d), at the time of writing, more than a year after the formal end of the programme, the findings of the internal evaluation programme had not been published.

It is also interesting that our interviewees cited the speed of the programme, and the need to move onto ‘the next shiny thing’, as issues affecting their ability to develop more worked out approaches which could have been standardised and spread. This highlights the potential importance of temporality in policy implementation which is not something explicitly addressed by Matland. Our study suggests that, in the programme as implemented, there was a fundamental conflict between the design of a ‘bottom-up’ programme and the intention to develop standard models and approaches. It is possible that a slower and more considered approach might have lessened this conflict. Unfortunately the fast pace of policy in the contemporary NHS (Uohy, Reference Uohy2018) means that time is rarely available for considered and critical approaches to policy development and implementation.

Discussion

Using Matland’s (Reference Matland1995) conflict and ambiguity framework we have been able to examine the stated goals of the former NCM Vanguard programme, from both documentation and national level interviews, and shown that under this programme the goal of locally specified bottom-up development was incompatible with the goal of developing frameworks and/or products which could be easily transferred elsewhere. At the outset, ‘bottom-up’ development was successful in generating enthusiasm for change at the local level. This was important in supporting the development of local solutions for the complex task of providing suitable and sustainable care across sector and organisational boundaries, building up relationships and trust between organisations who may not have historically worked well together and fostering enthusiasm for change. However, during its three year timeframe (2015/16 to 2017/18) the Vanguard programme was unable to successfully collate the lessons from these (50) different local approaches to generate replicable solutions that could be implemented and spread elsewhere. It is possible that a slower paced and more critically evaluated programme (as suggested by Matland’s ‘experimental’ approach) might have mitigated these issues; however, there were other political pressures at work requiring rapid demonstration of progress (Checkland et al., Reference Checkland, Coleman, Billings, Macinnes, Mikelyte, Laverty and Allen2019), which rendered such a reflexive programme unfeasible.

Exploring the NCM Vanguard programme through the lens of Matland’s (Reference Matland1995) conflict and ambiguity model raises questions as to whether the failure to generate generalisable solutions represents a failure of programme design, which could have been remedied by changes to the support programme, or whether this was an impossible task, given what we know about the need for bottom-up approaches to support context-sensitive, cross-organisational working (Checkland et al., Reference Checkland, Coleman, Billings, Macinnes, Mikelyte, Laverty and Allen2019). One of the key tensions described by our interviewees was between the need to demonstrate early ‘success’ in order to generate local enthusiasm and further change, whilst gaining national approval to secure ongoing (annual) funding, conflicting with the aim of creating a solid evidence base to show if developments could or should be rolled out more widely. This implies that speed of implementation is important for more than just meeting national policy imperatives; speed also brings with it local momentum, which may be important in overcoming resistance to change.

Our interviewees also suggested that the high profile nature of the programme could limit opportunities for careful context-specific assessment and cross-context comparisons, as highlighting initiatives that failed is potentially problematic in a high profile programme. Moreover, this need for visible success and the increasing requirement to demonstrate this according to narrowly defined metrics may have discouraged initiatives that would take time to demonstrate effectiveness; for example, those focusing on prevention.

The NCM Vanguard programme was presented at the outset as having low conflict and high ambiguity in Matland’s (Reference Matland1995) terms. However, Matland’s model is dynamic, not static, so it does not necessarily engage with the temporality of policy programmes. Indeed, it is possible that policies might shift between quadrants, with implications for implementation approaches during different phases of a policy (Hudson, Reference Hudson2006). This is part of the negotiation process on what Barrett and Fudge (Reference Barrett and Fudge1981) usefully identified as the policy-action continuum. This conceptualisation identifies policy as a multi-dimensional, multi-organisational field of interaction, with negotiation (and potential disagreement) between those in control of ideas and resources (in this case, NHSE policy makers, NCM leads, programme support leads) and those upon whom action depends (i.e. local commissioners and providers). It is possible to envisage a new care model pilot programme which moved along the continuum from experimental local pilots to more central control once feasible and effective ‘models’ had been identified, supported by negotiation and engagement between local and national actors. However, in practice, there were a number of contextual conditions which prevented this from occurring, including political pressures, the need for a high profile and expensive programme to be seen to be successful and, more locally, the need for visible success to sustain enthusiasm and overcome resistance. Such conditions seem likely to occur with most large scale change programmes, meaning that the goal of supporting and managing local, contextually sensitive ‘bottom-up’ approaches will always be incompatible with the stated goal of generating ‘standard products and frameworks’ for rollout elsewhere.

Other research supports this interpretation. Kuipers et al. (Reference Kuipers, Higgs, Kickert, Tummers, Grandia and Van der Voet2013) highlight the value of bottom-up approaches to change, whilst adding the caveat that the outcomes – and outputs – arising from such change programmes will be unpredictable and can rarely be specified in advance. Horton et al. (Reference Horton, Illingworth and Warburton2018) explored change in complex systems, highlighting the difficulties associated with ‘codifying’ innovations and the role of local adaptation. It would thus seem that the ambition that a broad range of diverse and locally specific projects would result in codified frameworks was always unlikely to be achieved. We also identified inherent contradictions in the programme between the underlying assumption that the new care models would be beneficial (evidenced by the requirement for STPs / ICSs to demonstrate that that were going to roll out MCPs, PACS and ECHs) and the commitment to robust evaluation designed to explore in depth whether or not new care models delivered better outcomes. This contradiction was enhanced by the narrowing of national focus on outcomes down to a small number of measures of hospital use, as it is possible that Vanguards may have been delivering service improvements not captured by these metrics (Checkland et al., Reference Checkland, Coleman, Billings, Macinnes, Mikelyte, Laverty and Allen2019, p6-7).

Our research suggests that rather than trying to develop a set of templates of how to do things, it may be that a set of principles for design is a better option to enable spread of ideas from such policy programmes. It also suggests that policy makers should consider from the outset what and how lessons will be learned. This came at a later stage in the process for the NCM Vanguard programme and put additional demands on sites (especially those perceived to be doing well) to engage with others, to share best practice, at a time when their focus needed to be on mainstreaming what had worked locally, as the support programme came to an end (early 2018). According to Bailey et al. (Reference Bailey, Checkland, Hodgson, McBride, Elvey, Parkin, Rothwell and Pierides2017, p210) “[l]ocal pilot schemes bring policy makers and evaluators into close contact, surfacing tensions between the different and sometimes competing need for knowledge versus the need for evidence”. Had the goal/intended outcome been to gain rich knowledge on what not to do and or how to generate fairly rapid change from bottom-up – instead of looking to scale and spread replicable models and frameworks – the method of achieving this could have been a much better fit. Jensen et al. (Reference Jensen, Johansson and Lofstrom2018) also point to the challenge of ‘fickle and fleeting alliances’ (p12) between local actors in supporting the implementation of policy programmes. For such complex changes to be developed and supported, strong trusted relationships need to be fostered, which takes time. This requires a different way of thinking as, under such programmes, individual organisations involved may see themselves as either winners or losers but the change may work effectively at the system level – across, for example, an ICS – and be better for recipients of the policy change.

Matland (Reference Matland1995, p168) describes high conflict, high ambiguity programmes as representing ‘symbolic implementation’ (see Figure 1) in which ‘local level coalition strength determines the outcome’. This suggests that areas where there was already a history of effective joint working (with a level of established trust, previous integrated pilots etc.) across organisations and sector boundaries would potentially be more successful in changing ways of working under this programme. Moreover, high ambiguity high conflict programmes may, according to Jensen et al.’s synthesis (Reference Jensen, Johansson and Lofstrom2018, p448), be useful in ‘showcasing innovative action’ and ‘inspiring change in other organisations’, both of which were stated goals of the Vanguard programme. Our follow-up research is exploring in more depth how Vanguard initiatives were initiated and sustained locally, and will also explore how far Vanguards acted to showcase and inspire innovation elsewhere. Matland’s model may prove helpful in gaining a more nuanced understanding of the local level experiences related to the three distinct vanguard types (MCP, PACS and ECH) on which we will focus.

Conclusion

Matland’s (Reference Matland1995) framework has provided a valuable lens through which to consider the ‘successes’ of a high profile policy programme in England. In particular it has served to highlight the inherent tensions between bottom-up fostering of enthusiasm and engagement within change programmes, and the need for coherent learning at national level to support wider roll out and spread of successful initiatives. This is important, as policy implementation in England and elsewhere increasingly relies upon local pilots and subsequent roll out as a means of enabling implementation (Ettelt et al., Reference Ettelt, Mays and Allen2014; Checkland et al., Reference Checkland, Coleman, Billings, Macinnes, Mikelyte, Laverty and Allen2019). Our study suggests the need for policy makers to explicitly consider what might be required for wider spread of initiatives from the outset, and to guard against the propensity to broadcast ‘good news’ quickly to the detriment of realistic assessment of impact. In relation to policy implementation design, where desired outcomes are unclear, a more restrained approach – with an initial assessment of relevant evidence relating to proposed interventions and subsequent careful assessment of how far particular service interventions could be beneficial and more likely to yield products – could support wider roll out as outputs. However, this would not be compatible with the desire to rapidly demonstrate progress (Checkland et al., Reference Checkland, Coleman, Billings, Macinnes, Mikelyte, Laverty and Allen2019, p92). It also suggests that for a high ambiguity high conflict programme to achieve positive outcomes an extensive programme of support should be included, or aims and goals may never be realised. Setting unrealistic or incompatible goals for a programme is unhelpful and potentially damaging to outcomes overall. Matland’s framework could provide a useful tool for those responsible for policy implementation in seeking to optimise their approach. Notwithstanding criticisms of the model, its use has allowed us to surface issues surrounding the temporality of policy programmes, even though this is not an explicit focus of Matland’s work.

Finally, we have highlighted the lack of clarity over how products and models from the NCM Vanguard programme were intended to be disseminated and spread, including where future funding would come from. In particular, we have shown a tension between approaches to ‘scaling up’ and ‘spreading out’, with limited guidance over how Vanguards – local initiatives, covering a limited population – might relate to the changes anticipated under STP / ICS models covering broader geographical populations (Checkland et al., Reference Checkland, Coleman, Billings, Macinnes, Mikelyte, Laverty and Allen2019, p92). While Matland’s model cannot predict future behaviour (Paudel, Reference Paudel2009), it points to the need for policy makers to make sure goals within any given policy programme are compatible, or at the very least that potential conflicts are surfaced and considered.

Disclaimer

This report is based on independent research commissioned and funded by the NIHR Policy Research Programme ‘National evaluation of the Vanguard New Care Models Programme’, PR-R16-0516-22001. The views expressed in the publication are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR, the Department of Health and Social Care, arm’s length bodies or other government departments.