Introduction

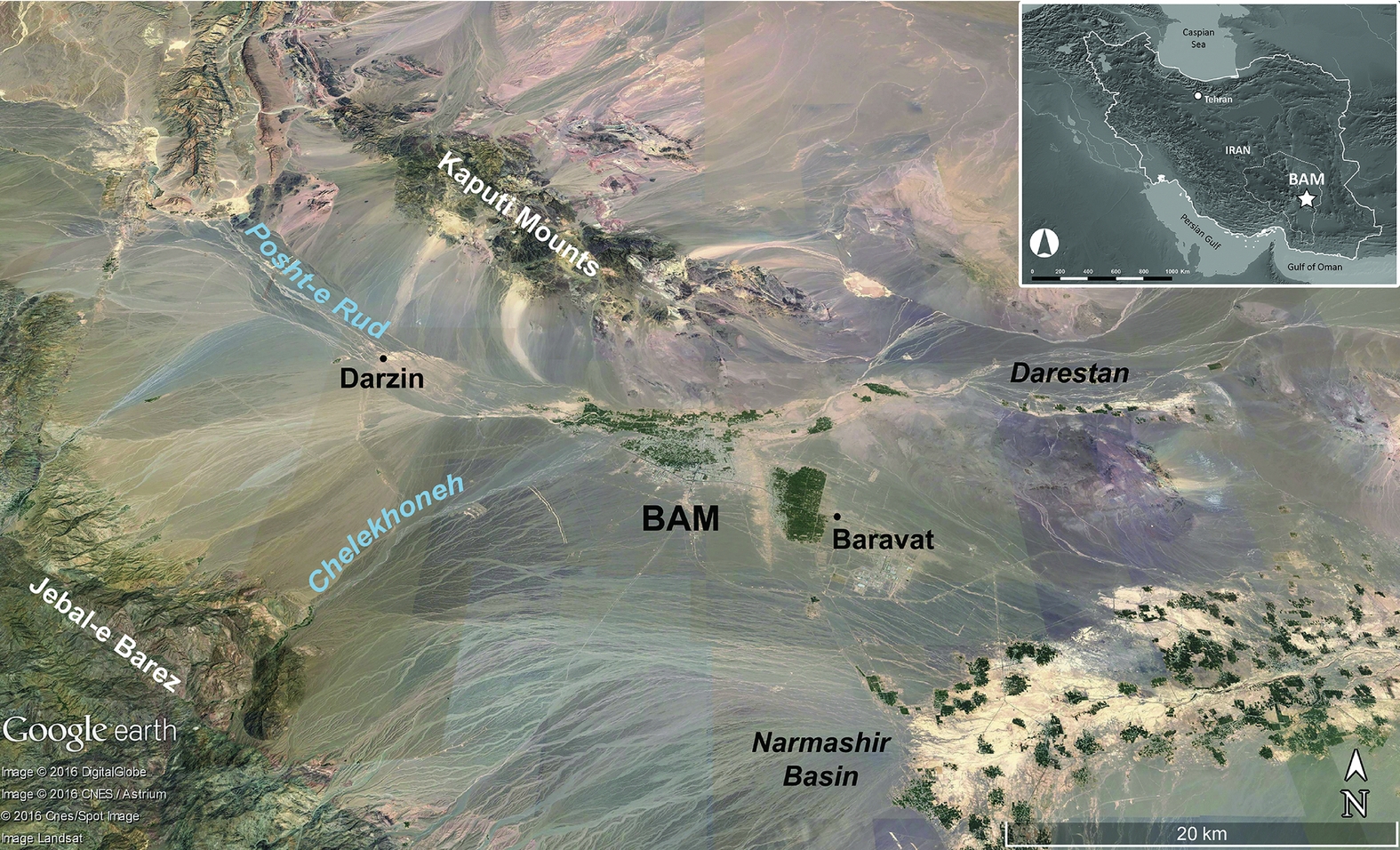

The Bam Archaeological Mission (BAM) in the Bam-Narmashir region, in the south-western margin of the Lut Desert (Kerman, Iran), began in 2016 (Figure 1). The BAM's main objective is to investigate the ancient settlement in this area—its evolution, cultural links and relationship to environmental changes. Beyond the Bam region, this research aims to contribute to the study of ancient south-eastern Iran, and, more broadly, to the understanding of the dispersal and interaction of people, cultures and technologies across Middle- and South Asia during pre- and proto-history. The creation of BAM was prompted by the discovery of proto-historical sites after the infamous 2003 earthquake: Chalcolithic sites in Bam's western periphery and Neolithic–Chalcolithic sites east of Bam in Darestan, including the Neolithic site of Tell-e Atashi (Adle Reference Adle, Honari, Salamat, Salih, Sutton and Taniguchi2006; Garazhian Reference Garazhian2009; Soleimani et al. Reference Soleimani, Shafiee, Eskandari and Salehi2016). In its first field season (2016), the BAM surveyed the region. In 2017, the mission opened test trenches at Tell-e Atashi.

Figure 1. Satellite image of the Bam-Narmashir region showing the location of Bam city and the 2016 survey area between Darzin and Darestan (© Google Earth).

First field season

In 2016, the BAM surveyed along the area's main west–east river system for about 60km between Darzin and Darestan (Figure 1). This recorded over 200 archaeological sites with Palaeolithic to Islamic remains, including many Neolithic and Late Chalcolithic sites. Six sites yielded Middle Palaeolithic lithics. We recorded more than 80 Neolithic sites, including approximately 35 aceramic sites. The Neolithic pottery is a plain, vegetal-tempered ware, comparable to other Iranian Neolithic plain vessels, such as at Tepe Yahya, approximately 170km to the south-west (Beale & Lamberg-Karlovsky Reference Beale and Lamberg-Karlovsky1986). Around 10 Early Chalcolithic sites (mid to late fifth to early fourth millennia BC) were also discovered, their typical surface material comprising fine, painted ceramics named Black-on-buff ware and Black-on-red ware. These particular ceramics are also reported in both Kerman and Seistan-and-Balochistan Provinces, including from Tal-i Iblis (periods I–II), Shahdad, Tepe Yahya (period V) and the Bampur Valley (Caldwell Reference Caldwell1967; Beale & Lamberg-Karlovsky Reference Beale and Lamberg-Karlovsky1986; see also Mutin et al. Reference Mutin, Moradi, Sarhaddi-Dadian, Fazeli Nashli and Soltani2017).

The Bam region is then marked by an increase in local occupation, represented by approximately 70 Late Chalcolithic sites dating to the rest of the fourth millennium BC. Their surface material includes a painted ceramic named Aliabad ware, which is reported from additional sites in south-eastern Iran, including Tal-i Iblis (period IV), and south-western Pakistan (Caldwell Reference Caldwell1967; see also Mutin et al. Reference Mutin, Moradi, Sarhaddi-Dadian, Fazeli Nashli and Soltani2017). The Aliabad settlements in Bam include sites with ceramic kilns and misfired fragments. The Bronze Age, then, saw a sharp decrease in occupation, characterised by sparse third-millennium BC material; Bronze Age Bam so far lacks the typical, fine mineral-tempered, painted ceramics and chlorite objects, as well as the high site density and large settlements that characterise the Halil Rud Valley (approximately 90km to the south-west) during this period (Madjidzadeh & Pittman Reference Madjidzadeh and Pittman2008). Finally, we observed few sites with Iron Age/early historical materials, although sites with ceramics relating to the Iron Age through to the Parthian period (c. first millennium BC to 224 AD) are present south of Bam city (Adle Reference Adle, Honari, Salamat, Salih, Sutton and Taniguchi2006: 45–46; Figure 1: west of Baravat).

Second field season

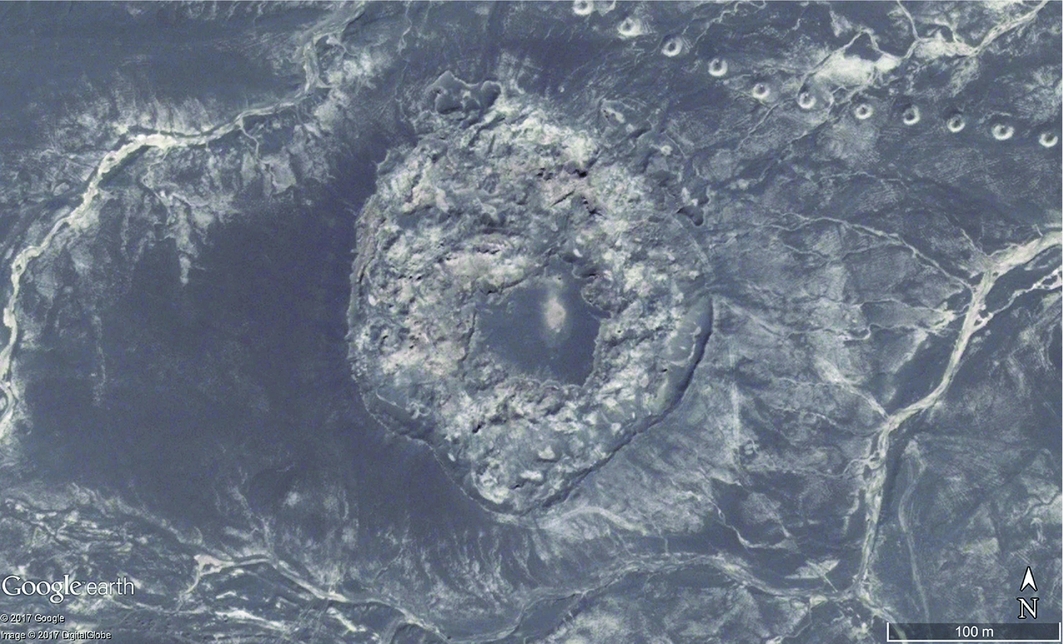

In 2017, we resumed excavation at Tell-e Atashi. The mounded part of this site covers approximately 3.6ha and is the largest Neolithic site recorded in the Bam region (Figure 2). A trench opened in 2008 revealed levels with square mud-brick structures radiocarbon dated to between the late sixth and mid fifth millennia BC, with associated lithics and small finds, but no ceramics (Garazhian Reference Garazhian2009). This information, combined with the critical location of Tell-e Atashi between the Fertile Crescent and South Asia, prompted us to resume fieldwork at this site. Fieldwork at Tell-e Atashi has great potential for both improving our understanding of the southern Iranian Neolithic and providing new research data and models for the development of farming across Iran and South Asia.

Figure 2. Satellite image of Tell-e Atashi (© Google Earth).

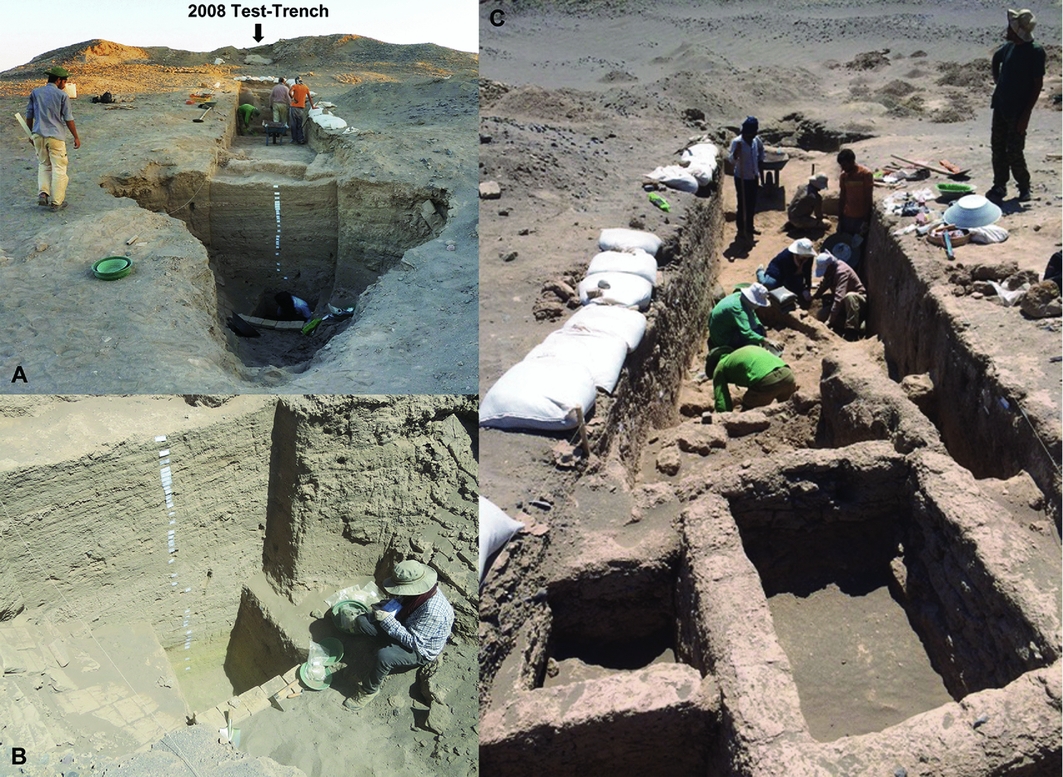

Our goals for 2017 were to gather further information on the stratigraphy, chronology and spatial organisation of this site, before planning more extensive future excavations. We opened a new trench—which aligned with the 2008 test trench (Figure 3)—as well as seven additional test trenches in other areas of the site. In the first trench, we exposed the earliest archaeological deposits and sterile soil almost nine metres below ground surface at the top of the site (Figure 3A & B). In the upper part of this trench (close to the surface), we discovered mud-brick structures similar to those excavated in 2008 (Figure 3C).

Figure 3. Tell-e Atashi trench: A) view from the south with the 2008 test trench in the background; B) view of the deep sounding in the southern part of the trench; C) view from the north of the trench and the mud-brick structures close to the surface in the foreground (© BAM).

Approximately 75m farther north, we excavated a well-preserved mud-brick building (Figure 4), in which a child burial was placed after the area was abandoned (Figure 5). The material culture at Tell-e Atashi comprises lithics, stone vessels, beads and perforated discs, as well as clay balls, cones and figurines (Figure 6). Some of these objects, as with the mud-bricks used for construction, have parallels at Tepe Yahya. In contrast to Tell-e Atashi, however, Tepe Yahya yielded ceramics from its earliest Neolithic levels (Beale & Lamberg-Karlovsky Reference Beale and Lamberg-Karlovsky1986).

Figure 4. Tell-e Atashi, mud-brick building in test trench 6 (© BAM, 3D model created by O. Nasrabadi).

Figure 5. Tell-e Atashi, child burial in test trench 6 (© BAM).

Figure 6. Tell-e Atashi, selection of clay objects: balls (upper row), cones (middle row) and figurines (lower row) (© BAM).

Acknowledgements

The BAM is a cooperative project between the Iranian Center for Archaeological Research, the Iran Research Institute for Cultural Heritage and Tourism, the French National Center for Scientific Research (CNRS-UMR 7041, Archéologies et Sciences de l'Antiquité, Archéologie de l'Asie centrale) and the French Ministry for Europe and Foreign Affairs. The authors also appreciate the support provided by the Kerman Province Cultural Heritage Tourism and Handicrafts Organization and the Arg-e Bam Research Foundation.