Introduction

The 1992 Convention on Biological DiversityFootnote 1 (CBD) was a breakthrough in global policy making. It combined a concern for the environment with a commitment to resolving longstanding human injustices regarding access to and use of biological resources.Footnote 2 With the exception of the United States, all countries on earth have ratified the CBD, which aims to conserve biodiversity, achieve its sustainable use, and reward its custodians with fair and equitable benefit sharing.2

The CBD was agreed more than a quarter-century ago. The 2010 Nagoya Protocol,Footnote 3 which supplements the CBD with specific legally-binding obligations on benefit sharing from the use of genetic resources and associated traditional knowledge (TK), celebrates its 10th birthday in 2020. The 2004 South African National Environmental Management Biodiversity ActFootnote 4 is 15 years old. All of the above require that benefits from the use of biological resources are shared with the holders of TK, in particular indigenous communities.Footnote 5

Yet, if one searches academic databases, the grey literature, and global search engines for successful access and benefit sharing (ABS) agreements with indigenous communities, one finds almost nothing. Most information gives advice on how to negotiate a successful ABS agreement,Footnote 6 or delivers sample contracts without substantial examples.Footnote 7 One could almost say that the world is still waiting for the first big, successful, monetized ABS agreement associated with TK.

Initially, hopes were high that the San community of Southern Africa was going to be the first indigenous group to be rewarded with a regular income stream for guarding TK. The San are said to be the oldest genetic ancestors of modern humans.Footnote 8 They hold knowledge on a wide range of indigenous southern African plants.Footnote 9 Known for their distinctive click languages, San numbers have now dwindled to approximately 111,000 people living primarily in Botswana, Namibia and South Africa, with small remnant populations in Angola, Zimbabwe, Zambia and Mozambique.

The first benefit sharing agreement negotiated by the South African San related to the appetite- and thirst-suppressant properties of the hoodia succulent. Signed by San representatives and a South African research institute (Council for Scientific and Industrial Research, CSIR) in 2003, the agreement allowed the CSIR to profit legally and ethically from an earlier patent on Hoodia properties by licensing their patent,Footnote 10 first to Pfizer then to Unilever (Wynberg, Schroeder, Chennells 2009). Whilst milestone payments were made into the San Hoodia Trust, no commercial product was ever developed, and both Pfizer and Unilever returned their licenses to the CSIR. For a second San benefit sharing agreement in 2008, which has received little international attention despite having a successful product associated with it, see Box 1.Footnote 11

Box 1. The Zembrin® Benefit Sharing Agreement

In 2008, the South African San Council signed its second benefit sharing agreement, covering traditional knowledge of the sceletium plant. Standardized botanical extracts of the plant are now used in a product called Zembrin® to counter anxiety, stress, and depression. The patent-protected active components of the plant are currently marketed by HG&H Pharmaceuticals in South Africa, the USA, Canada, Brazil, Malaysia, and Japan. 5 percent of all sales of the extract are paid into a trust fund for the San peoples, with a further 1 percent paid for the use of a San logo on the product. The proceeds are shared equally with two communities in Namaqualand, who provided a major lead to the commercial developer.

The third major San and Khoi benefit sharing agreement is likely to be a big occasion. On 25 March 2019, the San, the KhoiFootnote 12 and the South African rooibos industry signed the Rooibos Benefit Sharing Agreement (RBSA), which is the first comprehensive, industry-wide benefit sharing agreement and globally without parallel. It is exceptional as it not only spans an entire industry, but also because the product is already on the market. Hence, there is no translation gap.Footnote 13

This article analyzes the following aspects of the Rooibos agreement:

-

• Why traditional knowledge about the rooibos plant is subject to a benefit sharing agreement.

-

• The process followed from claiming that benefit sharing was due, through to signing an agreement.

-

• The details of the Rooibos Agreement.

-

• The main challenges: Why did the process take nine years?

-

• How the agreement was influenced by the 2017 San Code of Research EthicsFootnote 14 and in particular, the values of respect, honesty, fairness, and care.

-

• The policy implications of the Rooibos Agreement, and its potential to influence benefit sharing agreements involving indigenous communities in other regions of the world.

Rooibos

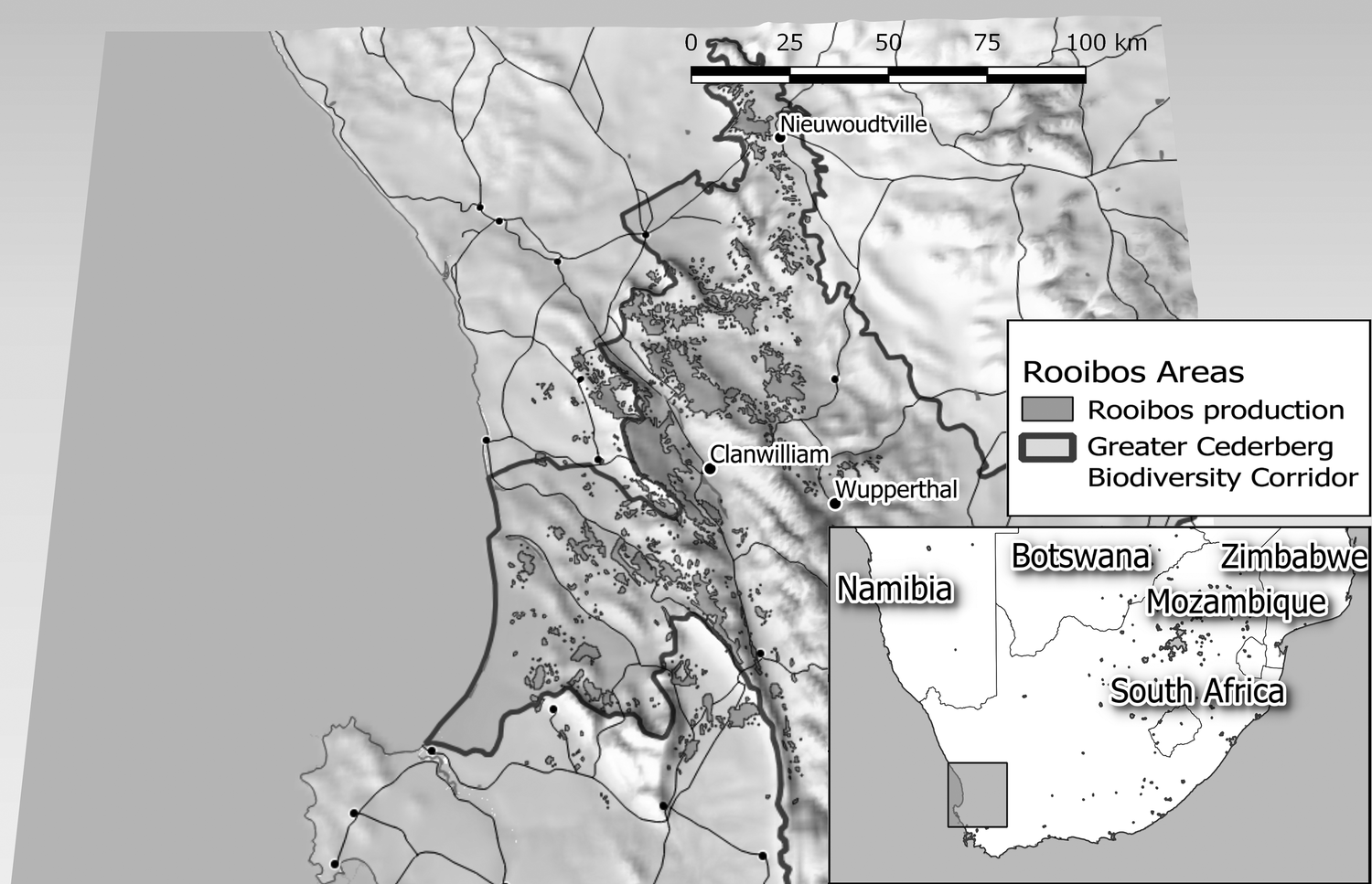

Rooibos or Aspalanthus Linearis is a plant primarily known around the world as a tea.Footnote 15 Its history of commercialization dates back at least 150 years.Footnote 16 Today, the rooibos tea industry employs 5,000 people in South Africa, produces around 15,000 tons of processed leaves per year, of which half are exported, and generates an income of approximately 500 million Rand per year (29 million Euros).Footnote 17 In 2014, rooibos received geographical indication status, the first nonalcoholic South African product to be so designated.Footnote 18 As a result, only rooibos tea from the indicated area (the Cederberg mountains of South Africa, see Figure 1) can legitimately be called rooibos.

Figure 1. Production areas of rooibos in the Cederberg Mountains (figure based on three earlier diagrams). Footnote 19

Given that rooibos is known primarily as a tea, one might ask why it should even be considered for benefit sharing under the CBD. Is benefit sharing not restricted to research and patent-related developments, as in the hoodia case?

This was the question raised by representatives of the rooibos industry in response to the TK holder request to enter benefit sharing negotiations under NEMBA, the South African Biodiversity Act. The industry’s question had two main aspects:

-

1. Why should there be a legal basis for restitution claims for traditional knowledge that was given by Khoi and San ancestors to European settlers in the 18th century? The CBD was only agreed in 1992 (and is not considered retroactively binding on Parties to the Convention), and rooibos tea, like coffee and tobacco, had been in the public domain for around 150 years by then.

-

2. Given that the rooibos industry is no longer involved in bioprospecting Footnote 20, an activity captured under the CBD, but only in biotrade Footnote 21—which is not explicitly part of the CBD and the Nagoya Protocol—why wouId benefit sharing be due?

The following answers were eventually accepted by representatives from the rooibos industry:

First, the commercialization of rooibos was based on the originally shared TK, a scenario already envisioned by the CBD and NEMBA, therefore there was no time limit on the issue of restitution.

Second, NEMBA, the South African Biodiversity Act, is broader than the CBD and the Nagoya Protocol, incorporating in its remit unchanged indigenous biological resources such as tea, as long as their use is based on indigenous TK, and as long as there is commercial exploitation. NEMBA defines bioprospecting as:

any research on, or development or application of, indigenous biological resources for commercial or industrial exploitation”… “including the utilisation … of any information regarding any traditional uses of indigenous biological resources by indigenous communities.Footnote 22

Hence, any indigenous biological resource, changed or unchanged, that is used commercially and based on TK is subject to benefit sharing. Given that the RBSA was signed under the auspices of the South African Department of Environmental Affairs, rooibos as an unchanged tea as well as an ingredient for health and cosmetic products was covered by the biodiversity legislation.

Third, “countless rooibos advertisements … exploit the image of San and Khoi and their traditional links to rooibos… [Hence,] clearly, there is a case to be made for benefit sharing linked to traditional knowledge.”Footnote 23

Fourth, there is a strong link between bioprospecting as defined in the CBD and rooibos, even though this was not the focus of the benefit sharing agreement under discussion here. Rooibos-related products are available in cosmetics, novel foods, slimming products, extracts, and flavorants.Footnote 24 Whilst rooibos is mostly known as a tea, it currently has in excess of 140 patents pending for its biochemical and health properties. Hence, with benefit sharing payments being levied at the processing level (see below), rooibos resources for uses other than tea are also de facto covered by the agreement. Additional protection is derived from rooibos’ geographical indication, which means it has to be grown in the Cederberg area.

The next section outlines the complex and lengthy process from the initial claim by the San that benefit sharing was due through to the RBSA.

The Process

Through the CBD, “indigenous peoples’ and local communities’ rights to … control over their own TK are receiving greater recognition than at any time in recent history.”Footnote 25 The RBSA is an example of indigenous peoples taking such control over their TK.

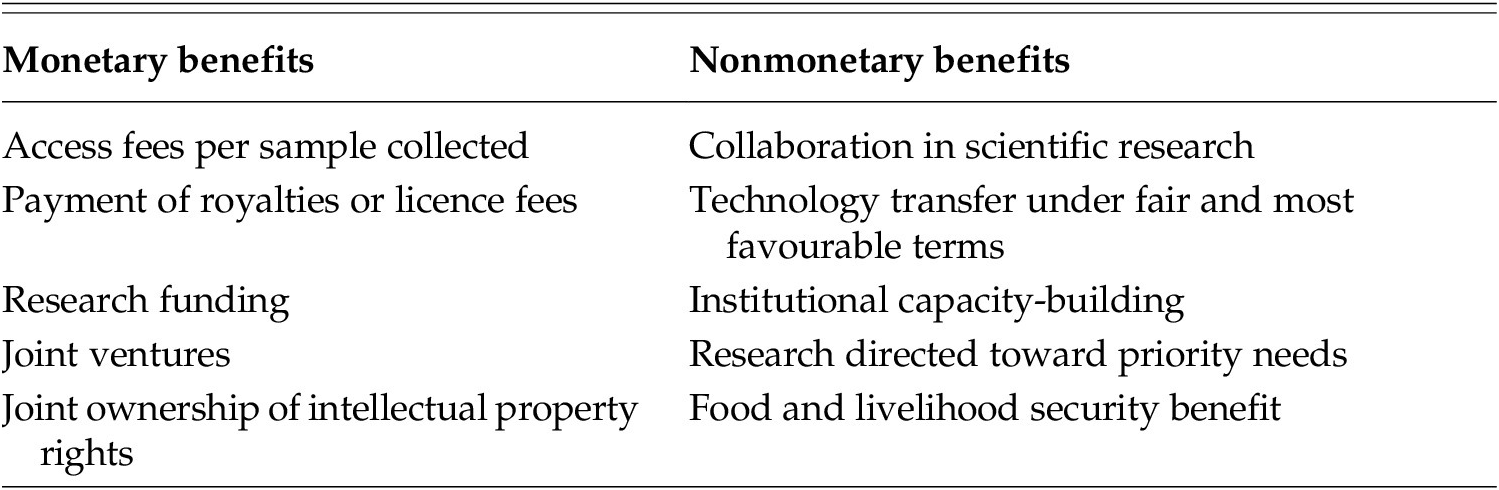

In 2010, the South African San Council initiated steps to challenge the South African rooibos industry over their use of traditional knowledge in relation to rooibos. The process is summarized in Table 1.Footnote 26

Table 1. Rooibos Benefit Sharing Agreement—the Process

It was accepted that due to the ground-breaking nature of the agreement, it would need to be fully reviewed in a year. It was also agreed that the launch would need to take into account the international relevance of the first comprehensive industry-wide benefit sharing agreement to be formed in accordance with the CBD and Nagoya Protocol.

The Rooibos Benefit Sharing Agreement

Benefit sharing agreements in South Africa are governed by contract law, and thus parties can agree terms of their own choosing, guided by and within the framework set by NEMBA. The process of negotiating benefit sharing agreements under NEMBA is required to be supervised by the relevant ministry, the South African Department of Environmental Affairs, and finally approved by the Minister.

The full title of the RBSAFootnote 30 is:

BENEFIT SHARING AGREEMENT In accordance with the National Environmental Management: Biodiversity Act 10 of 2004, based upon the principles contained in the 2010 Nagoya Protocol on Access to Genetic Resources and the Fair and Equitable Sharing of Benefits Arising from their Utilisation on Biological Diversity adopted in the International Convention on Biological Diversity (1992).

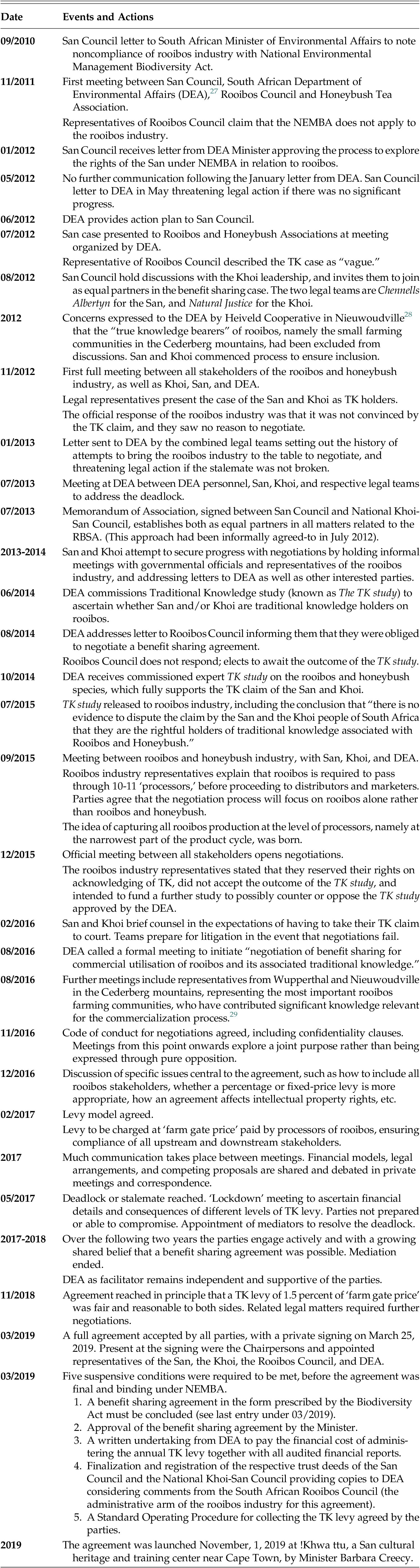

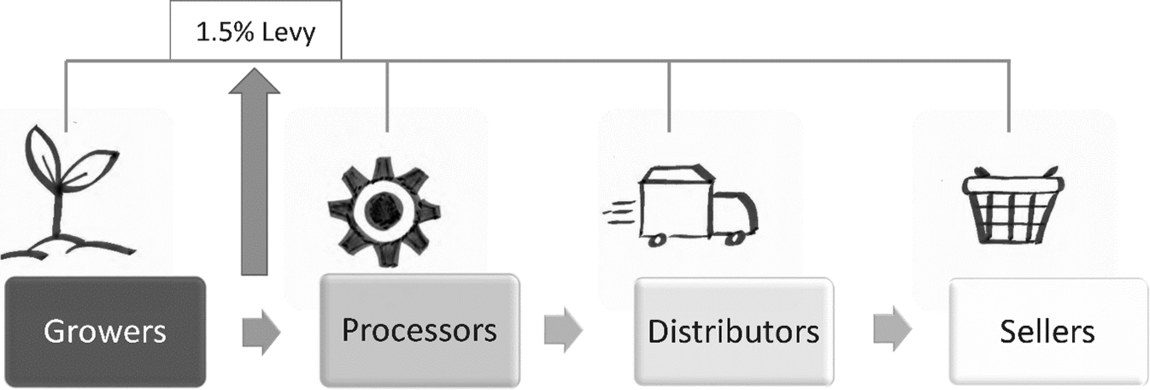

The partners to the agreement are illustrated in Figure 2. The San and Khoi people are recognized in the agreement as the traditional knowledge holders, who are represented by their two Councils. The rooibos industry value chain has four main groups, and in the RBSA, they are represented by one of those groups (the processors) and an administrative council. DEA facilitated and oversaw the benefit sharing negotiations.

Figure 2. Partners to the Rooibos Benefit Sharing Agreement.

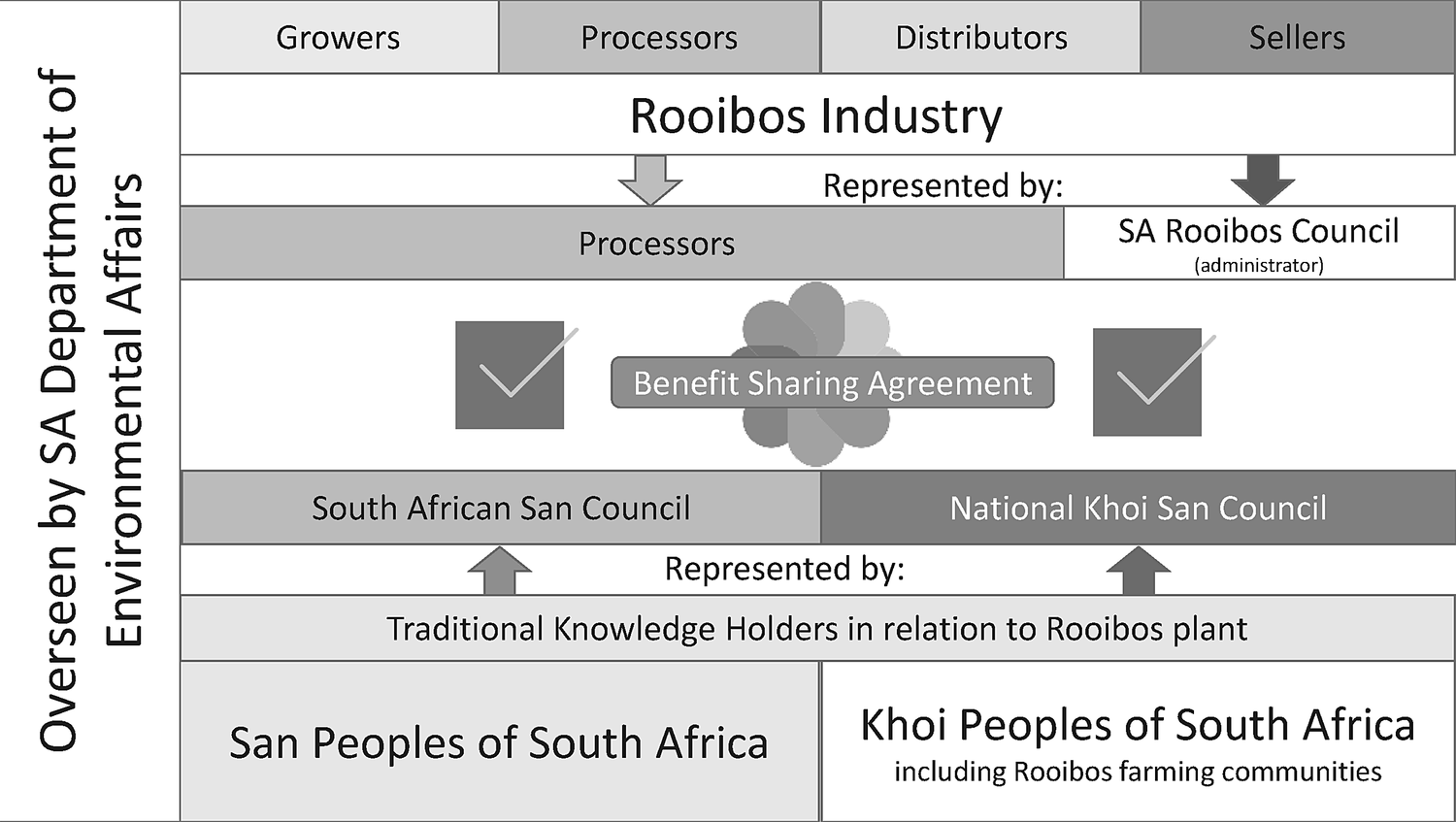

Whilst the Nagoya ProtocolFootnote 31 provides sample benefits (see Table 2), other benefits can be agreed.

Table 2. Overview of Benefit Sharing Examples from Nagoya Protocol

The RBSA includes both monetary benefits and the potential future specification of nonmonetary benefits.

The monetary benefit of the RBSA is an annual levy of 1.5 percent on the ‘farm gate price.’ The farm gate price is what processors (those who clean, dry, ferment, pasteurize, extract, etc.) pay for unprocessed rooibos. Figure 3 summarizes the rooibos value chain and shows at which point in the chain the levy is placed.

Figure 3. Point in the Value Chain for Levy.

The levy is paid by rooibos processors at the end of each financial year to DEA and then paid by DEA into two trust accounts, one created for the San, one created for the Khoi. By signing the RBSA, the rooibos industry also committed to exploring nonmonetary benefits for the TK holders. Whilst these have not yet been detailed, the RBSA suggests some examples, namely: “the creation of employment opportunities, bursaries, development schemes, mentoring and facilitation of livelihood creation, and other ways of delivering alternative forms of benefits to the two traditional knowledge holding communities.” Each community receives 50 percent of the total payment.

The levy which goes to the Khoi people is to be shared equitably with indigenous farming communities in the Cederberg mountains (see ‘Challenges’ section for the reasons why this was agreed).

The RBSA is anticipated as a “long-term partnership… based upon utmost good faith, where each Party strives for and contributes towards the success and good fortune of the other.”Footnote 32 The good faith element includes:

-

• confidence expressed in the RBSA that the TK holders “warrant and undertake that they represent and incorporate all groups and communities currently known to them… which may … hold TK [traditional knowledge] in respect of Rooibos.”

-

• recognition that the “economic viability of the Processers” is important and needs to be taken into account in any potential review of the levy.

-

• the commitment by the TK holders to “generally support… marketing and publicity efforts aimed at increasing the success of Rooibos products worldwide.”Footnote 33

Thus, the aim of the RBSA is to achieve optimal fairness between partners and:

to provide the maximum possible sharing of Rooibos benefits as required by the Biodiversity Act, whilst ensuring that the Annual Levy is sustainable and not damaging to the Rooibos industry, yet represent fair and equitable sharing of benefits as outlined in Nagoya Protocol.Footnote 34

The challenges

Arriving at a complex industry-wide benefit sharing agreement was a highly challenging task, as the nine year timeline above indicates. Each of the main challenges below needed to be resolved before the negotiations could continue.

Representation

One prominent reason why benefit sharing negotiations can fail is the criticism that local communities are not fairly represented amongst negotiators. In this regard, the most famous case to date is the Maya ICBG (International Co-operative Biodiversity Groups) Project in Chiapas, Mexico.Footnote 35 “The failure of the Maya ICBG was due largely to the lack …. of adequate representation.”Footnote 36

Having successfully negotiated the Hoodia benefit sharing agreement,Footnote 37 and the Sceletium benefit sharing agreement (see Box 1), the representative structures of the San community had already been tested and used successfully.Footnote 38 , Footnote 39 Particular challenges that were overcome for the earlier benefit sharing agreements were, in the Hoodia case, the transnational nature of San residence in Southern Africa, and, in the Sceletium case, the involvement of non-San informants regarding the medicinal use of plants. Yet, the rooibos case was even more complex, because:

-

• an entirely separate indigenous group, the Khoi, also held traditional knowledge of rooibos,

-

• significant progress to enable commercialization of rooibos was made by another group, namely, small-scale farmers in the Cederberg mountains, and

-

• there was no precedent worldwide for a comprehensive, industry-wide benefit sharing agreement.

With the addition of a serious lack of resources, these challenges are discussed below.

San and Khoi alliance.

The San and the Khoi peoples of South Africa are both regarded as indigenous communities in Southern Africa.Footnote 40 Whilst anthropologists and archaeologists present a range of different theories, the ancient rock art of Southern Africa is attributed to the San, who are predominantly of hunter gatherer origin, whilst the Khoi pastoralists entered South Africa later.Footnote 41 The TK study commissioned by DEA (see timeline) confirmed that both groups held traditional knowledge in relation to rooibos.

Whilst the San Council started the benefit sharing process, it was clear to the San leadership that the Khoi held a similar claim and that both groups needed to be included in any benefit sharing negotiations. The San leadership was also aware of the Chiapas (Maya ICBG) case, where benefit sharing negotiations had collapsed because agreement amongst several groups could not be achieved. Hence, being conscious of the high value of unity, in August 2012 the San Council invited the Khoi leadership to discuss a possible joint approach in relation to rooibos. A memorandum of understandingFootnote 42 (MOU) between the two indigenous groups was concluded, committing them to form a joint negotiating body in all matters relating to the rooibos, honeybush, buchu, and hoodia plant species.Footnote 43 It further stated that “any benefits received will be divided equally between them.” This MOU ensured that the two important issues of representation and division of benefits were dealt with early on, and that the parties could henceforth concentrate on negotiating the best possible outcome as equal partners.

Considering the above, the RBSA can therefore be regarded as a success story for Article 11 of the Nagoya Protocol, which states that:

Where the same traditional knowledge associated with genetic resources is shared by one or more indigenous and local communities in several Parties, those Parties shall endeavour to cooperate, as appropriate, with the involvement of the indigenous and local communities concerned, with a view to implementing the objective of this Protocol.Footnote 44

Rooibos farming communities.

Rooibos is farmed only in the Cederberg mountains north-east of Cape Town (see Figure 1), where many descendants of early Khoi live as small-scale farmers and farm workers. The Cederberg mountains are also the region for which a geographical indication on rooibos was obtained in 2014.

In and around the Cederberg towns of Wupperthal in the south, and Nieuwoudville in the north, rooibos is regarded as a way of life.Footnote 45 In these locations, an estimated 75 percent of local income is derived from rooibos tea,Footnote 46 whilst up to 90 percent of the local population (small-scale farmers and workers) were discriminated against during apartheid. Hence, “the geographical and political backdrop to the rooibos industry is one of dispossession and adversity.”Footnote 47

A central tension [in any rooibos benefit sharing] is the balance between achieving historical and restorative justice for the San and Khoi and recognizing the many others who have provided knowledge towards the success of the rooibos industry.Footnote 48

That rooibos is sold successfully all over the world as a tea is also, Wynberg argues, reliant upon contributions from inhabitants of the Cederberg mountains.

Such contributions … [include] momentous discoveries of individuals such as Tryntjie Swarts, who located the “golden nests” of rooibos seed in the 1920s and thus facilitated the industry's expansion; [and] Annekie Theron, who accidentally discovered in 1968 that rooibos had a soothing effect on her hyper-allergic baby, leading to a dramatic increase in demand for rooibos.Footnote 49

Against this backdrop, the National Khoi Council began consultations in the Cederberg Mountains and by 2013 elected representation of the Cederberg farming communities had been secured as part of the Khoi delegation of the benefit sharing negotiations.

As a result of the presence of the farming communities in the Khoi negotiation team, the RBSA includes a clause that the benefits from the agreement which are to go to the Khoi Trust, will be shared with the small-scale farming communities in the Cederberg Mountains.

Lack of resources

A common theme raised by indigenous organizations advocating for the various rights created in both international and domestic legislation is the massive and inherent power differential between them and their more established negotiating opponents.Footnote 50

In this case, the rooibos industry is commercially successful, with modern means of communication and the capacity to rely upon legal advice from professional accountants, as well as a leading international commercial law firm. The indigenous peoples by contrast relied on voluntary organizations representing the poorest of South African communities, with no immediate funding for legal representation and a lack of access to modern means of communication.

Whilst DEA has fulfilled its facilitative role in funding travel and logistics for the plenary meetings since 2012, both the San and Khoi were challenged by their lack of funding and capacity. The South African San Council had been functioning on a skeleton budget since 2001 that enabled them to employ only one or, at the most, two staff supporting a volunteer council. They had no additional funds to pay for community meetings, travel, or legal support. The lawyer representing the San interests did most of the work on the case pro bono. The National Khoi-San Council, despite having been formed by the government in 1999, had never been allocated funding, and it relied solely upon funds raised by its legal representatives, the environmental rights NGO Natural Justice. Legal and intellectual property advice for the TK holders was therefore reliant upon charity, as well as various international supporters of indigenous rights.

Complex, industry-wide Benefit Sharing Agreement

To date, no other comprehensive, industry-wide benefit sharing agreement has been concluded under the CBD and the Nagoya Protocol. Hence, there was no precedent from which the parties to the RBSA could learn.

Throughout the negotiations, the central question remained the issue of what constitutes a fair levy, i.e., both what the industry could afford, and what represents fair restitution for the holders of TK.

Numerous proposals were made as to how the large and complex rooibos industry could be covered by a single agreement with one point of collection for monetary benefits. Several financial models, legal arrangements and competing proposals were shared in private meetings and correspondence.

A mediation process was required to assist progress toward the final agreement that a 1.5 percent levy would be collected by processors of rooibos and shared with the TK holders (see Figure 3). As all rooibos is processed before it is either exported or converted into tea and other products, this model enables the cost of the levy to be spread and shared both ‘upstream’ to the growers, as well as ‘downstream’ to the distributors and sellers.

The groups involved in the RBSA overcame significant obstacles which had led to the collapse of similar benefit sharing agreements in other geographic regions. Of particular importance was the aforementioned unity amongst the San and Khoi as TK holders, the recognition of the contributions of small-scale farmers, and the willingness of the rooibos industry to cover all rooibos production and sale with one benefit sharing agreement.

The relationship with the San Code of Research Ethics

Indigenous peoples are frequently considered to epitomize vulnerable populations in need of protection from exploitationFootnote 51 , Footnote 52 , Footnote 53 , Footnote 54 whereby being ‘vulnerable’ can be defined as:

[facing] a significant probability of incurring an identifiable harm while substantially lacking ability and/or means to protect oneself.Footnote 55

Being exploited in research, or biotrade and bioprospecting, is a serious, identifiable harm. Taking the San community as an example,Footnote 56 deeply respected San community leaders have repeatedly expressed their concerns about such exploitation and have:

In recent years …, with increasing confidence, arrived at the conclusion that most … research on their communities was neither requested, nor useful, nor protected in any meaningful way. In many cases dissatisfaction if not actual harm was the result.Footnote 57

The effects of collective trauma (e.g., past genocide), loss of traditional lands, extreme poverty, lack of access to education, as well as lack of funds to employ outsiders, all meant “that the protection of … [San] traditional knowledge was precarious.”Footnote 58

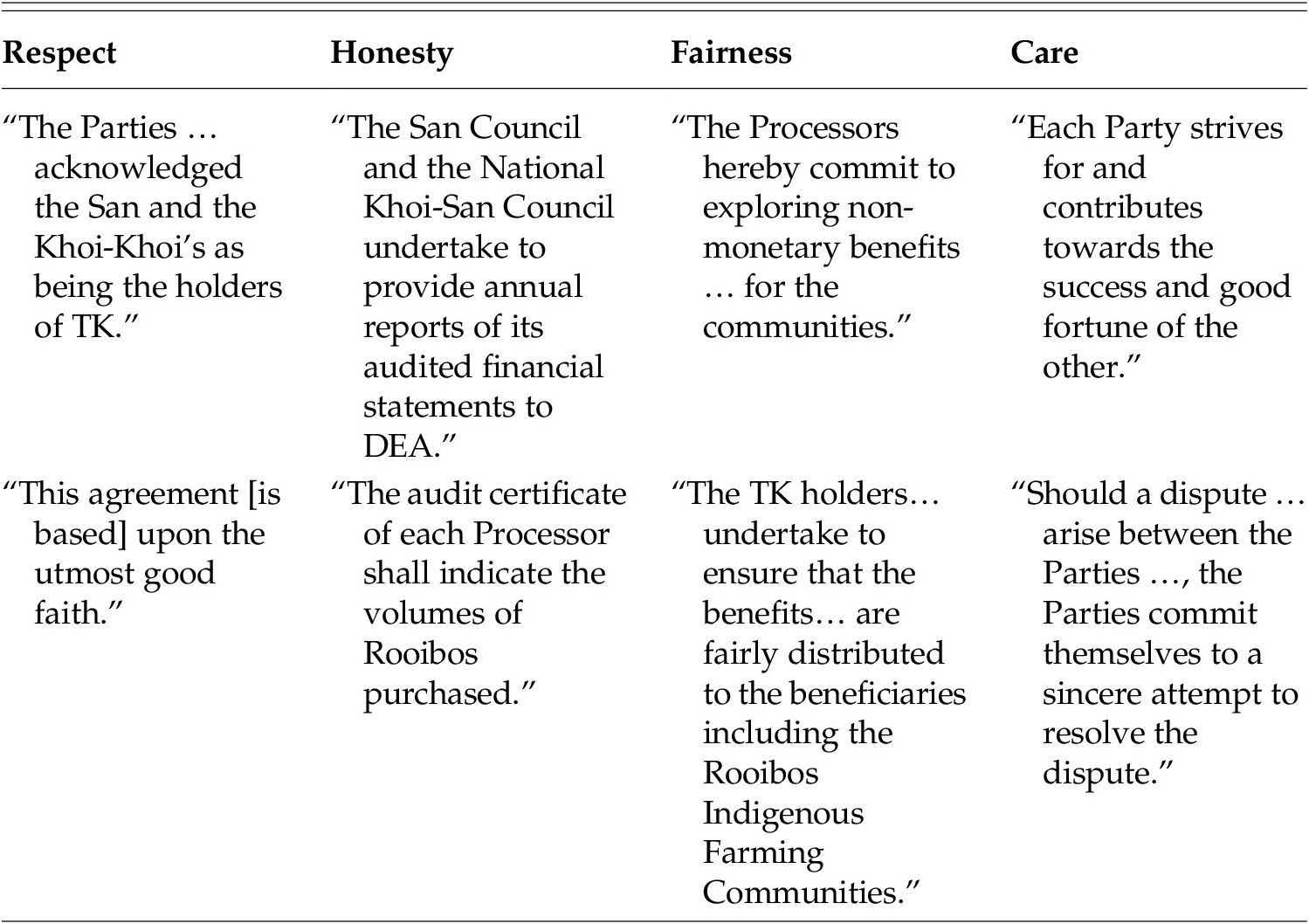

Yet, the San community have managed what no other indigenous community has done in Africa before, i.e., they were the first indigenous community on the continent to issue their own code of research ethics.Footnote 59 The San Code of Research Ethics (2017) is built around four substantial moral values, and also requires due process. After a range of consultations, the authors of the San Code were clear that they wanted respect, honesty, fairness, and careFootnote 60 from researchers and those using their TK. Unusually, and very effectively, the authors decided to add exploitation examples within the ethics code. For instance, under fairness, they wrote:

We have encountered lack of justice and fairness in many instances in the past. These include theft of San traditional knowledge by researchers. At the same time, many companies in South Africa and globally are benefitting from our traditional knowledge in sales of indigenous plant varieties without benefit sharing agreements, proving the need for further compliance measures to ensure fairness.Footnote 61

For rooibos, the RBSA ensures that the sales of indigenous plants based on TK no longer occurs without benefit sharing, thereby satisfying the moral value of fairness. Table 3 shows how respect, honesty, fairness, and care are prominently worked into the RBSA, which was informed in the crucial last years of negotiations by the San Code of Research Ethics. The examples given are not exhaustive.

Table 3. Respect, honesty, fairness, and care in the Rooibos Benefit Sharing Agreement (RBSA 2019)

One could argue that the main test for respect, honesty, fairness, and care is still to come, namely in the distribution of funding to local communities. Again, taking the San community as an example, the Andries SteenkampFootnote 62 Benefit Sharing Trust, which will be responsible for distributing funding to the San community, is clearly linked to the values of the San Code of Research Ethics. Its main principle is as follows:

The basis of all operations, functions and administration of this Trust will strictly be to assist San communities in their endeavours to protect their traditional knowledge and related biodiversity, to protect their cultural heritage, to advance their education and development and to improve their livelihoods; and doing so with respect, honesty, fairness and care.Footnote 63

In addition, the value of honesty is particularly strong in the provision that “the Trust and subsidiaries must be audited … on an annual basis,” whilst the values of care and fairness are particularly clear in the provision that “the Board of Trustees will not be paid any form of remuneration … as this Trust is run to the benefit of communities.”

Policy implications and outlook

The RBSA, based on respect, honesty, fairness, and care, is a major achievement.

-

• Financially, it is the biggest benefit sharing agreement between industry and TK holders since the adoption of the CBD more than a quarter of a century ago.

-

• It is the first comprehensive, industry-wide agreement to be formed in accordance with biodiversity legislation, which implements the CBD and Nagoya Protocol.

-

• The benefit sharing agreement is based on a well-established product, not a patent. Hence, on this occasion, it is already clear that a significant funding stream will become available to TK holders.

The government ministry DEA played an active facilitating role in encouraging the parties to reach a settlement, without losing objectivity or the trust of the parties. This active government support played a significant role in enabling resolution and signing of the RBSA.

With no precedent in the benefit sharing world, the RBSA stands as a concrete example of the ‘art of the possible.’ It serves to confirm that such agreements can be concluded in support of indigenous communities, industry, and governments implementing the CBD and Nagoya Protocol. It offers lessons and inspiration to indigenous communities, governments, and industry sectors both within Africa and other regions around the world. The mere fact that it has been successfully concluded should serve as confirmation that benefit sharing agreements of such scale and complexity are possible.

Global, regional and national policy makers would do well to pay heed to the RBSA. While the rooibos case is unique in a number of aspects, the experience offers several transferable insights regarding elements of success, including: patience; incrementalism; honesty, trust; genuine dialogue; strong legal support; a shared recognition that a fair, win-win deal is possible; government facilitation and leadership; and unity amongst indigenous peoples. Such ingredients of success can, of course, apply well beyond southern Africa.

Nevertheless, one could argue that the main challenges for the RBSA partners are still to come, as they implement the agreement to benefit the guardians of TK with respect, honesty, fairness, and care.