Informed Consent, in Part a Problem of Knowledge Translation

In order to fully participate in informed consent, patients must understand what it is that they are agreeing, or not agreeing, to. In most cases, patients look to their clinicians to help develop the appropriate understanding required to give informed consent. This provision of information by clinicians is challenged on 2 fronts. First, many clinicians are not in possession of the relevant evidence on which a decision rests and consequently present harms and benefits in general terms, for example, “beneficial” and “unlikely.” Second, patients commonly do not understand medical evidence when it is shared. These challenges are exacerbated in the Emergency Department, where time and emotional pressures operate.

In 2013, we identified an instance in which lack of patient and clinician understanding was resulting in less than informed consent. Frequently in emergency care, we need to provide optimal procedural sedation and analgesia (PSA) to allow for life-saving painful procedures. We found that the benefits of PSA were apparent to patients, caregivers, and clinicians, while the magnitude of the risks associated to PSA were unclear to all parties.

We had identified a translational gap between the best evidence available and proper informed decisions in the Emergency Department. Namely, with respect to the 5-step framework of the Research to Practice Continuum (Fig. 1), we discovered that in practice, we were not been able to overcome step 4—the bringing of evidence to the clinical encounter where it can contribute to informed, and shared, decisions.

Fig. 1 5-step framework of the Research to Practice Continuum.

In this article, we describe the development of a visual aid to communicate the risks associated with PSA performed in Emergency Department pediatric and adult patients.

Finding the Evidence Is Not Enough

In order to respond to the translational gap, we used knowledge synthesis research strategies to make the vast amount of data available comprehensible for clinicians and by extension their patients. We published 2 systematic reviews and meta-analyses evaluating the risks of performing PSA in the Emergency Department for both the pediatric [Reference Bellolio1] and adult [Reference Bellolio2] populations. We found that serious adverse events are exceedingly rare, regardless of the different medications used for sedation.

As a product of our synthesis work, we created a pocket card to help clinicians cite consistent risk information regarding PSA to patients. Healthcare professionals received this bedside tool enthusiastically. However, the informal feedback we received from patients and caregivers showed that the pocket card was suboptimal. Patients recognized that their clinicians were sharing risk information with them but did not understand the information, or were not able to make use of this information in decision making.

In response to these findings, we examined strategies from shared decision making (SDM), a related process to informed consent, as a potential way of making the synthesized data accessible and useful for patients. In so doing, we considered that informed consent goes beyond acquiring patient treatment permission, it represents an active decision that patients are making with their clinicians. To engage patients in healthcare decisions, the evidence about risks of a particular treatment must be clear for both providers and patients.

SDM in healthcare is a collaborative process that allows patients and health professionals to consider the best evidence available, along with patients’ values and preferences, to make healthcare decisions [Reference Zipkin3]. SDM includes the clear communication of the benefits and harms of interventions to patients [Reference Zipkin3] making it a potential means for translating knowledge into a useful and useable resource in clinical care.

Evidence-Based Medicine and Knowledge Translation

Evidence-based medicine, when first described by Gordon Guyatt and his colleagues in the early 1990s, was proposed to be the intersection of clinical expertise, patient values, and the best evidence available [Reference Guyatt4, Reference Sackett5]. Significant criticism throughout the years argued that it has focused too much on the data itself and it turned out to tie the hands of clinicians and patients of their choices in deciding optimal care [Reference Haynes, Devereaux and Guyatt6]. However, constant efforts have been made to align the evidence-based medicine core concepts with the translation of evidence into practice, especially regarding patient-centered perspectives [Reference Lang7]. The need for more knowledge translation as part of evidence-based medicine has emerged primarily from a gap between what is known from high-quality evidence and what is consistently done in clinical practice [Reference Lang, Wyer and Eskin8].

Translating research into practice is a complex process that involves creating or finding the evidence, its appraisal, dissemination, and awareness by clinicians, and adoption and implementation into a specific environment [Reference Diner9]. Communication of risks before informed consent acquisition requires more than knowing the best evidence available. It requires delivering and using this information in a meaningful and understandable way to improve the ability for patients to make an informed consent decisions.

Translating the Evidence into Practice

In 2015, 225 children and 278 adults underwent procedural sedation at our Emergency Department. Clinicians treating these patients were provided with a pocket card summarizing the harms and benefits of PSA to prepare them for informed consent discussions. The communication of the need and benefits of PSA was more straightforward for clinicians exposed to the card, but the communication of risks to patients remained challenging. The presentation of risks of PSA to patients in verbal form still led to significant differences among providers.

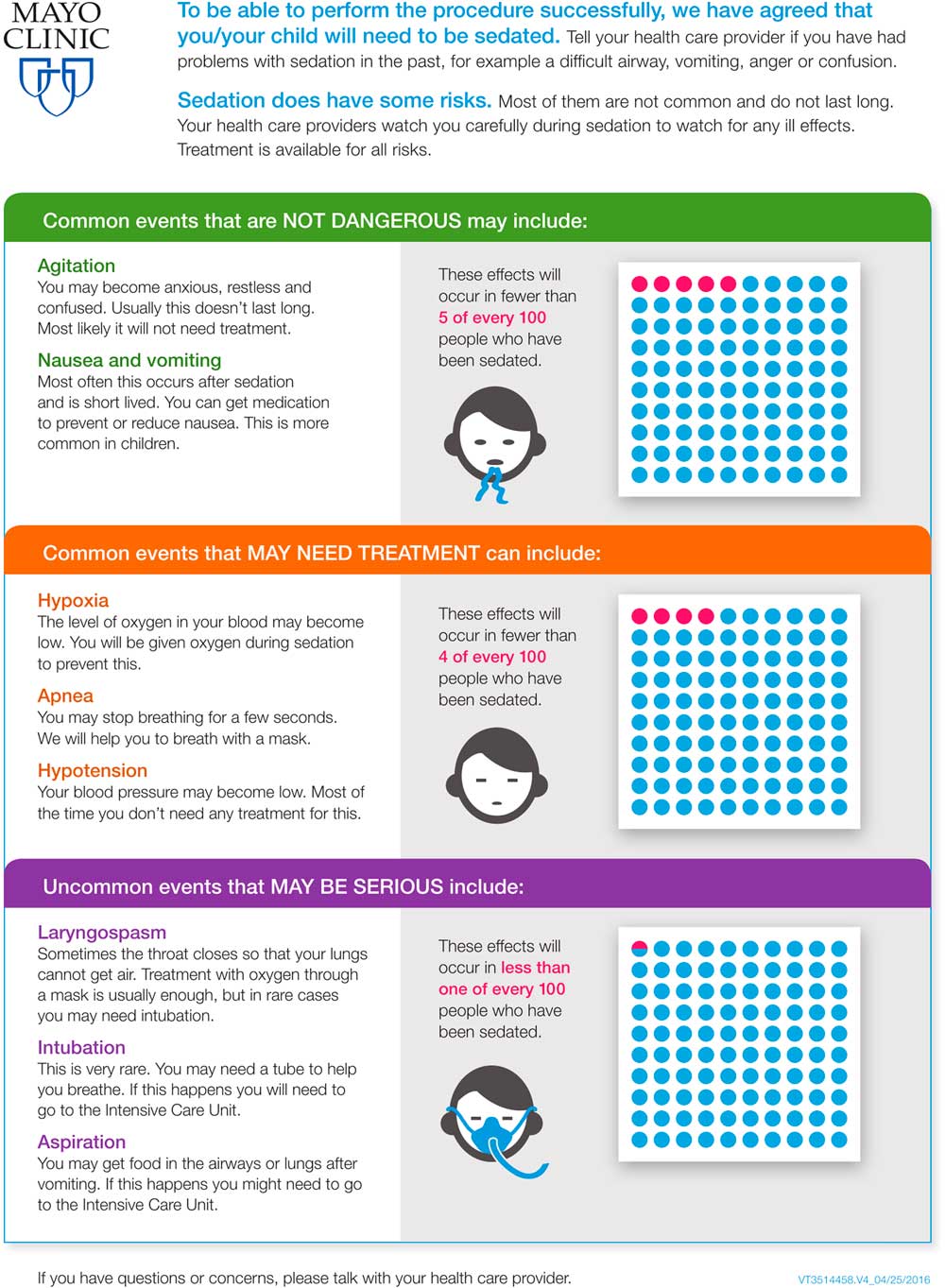

To support more accurate and consistent presentation of risk, we formed a team with implementation scientists, patient education specialists, nurses, physicians, and professional designers to transform the pocket card into a 6th grade reading level visual aid tool. Starting with the visual aid’s first version, we applied a DMAIC (Define, Measure, Analyze, Improve and Control) process [10] to design the tool. We measured and analyze its effectiveness through Delphi-type feedback from providers, patients, and caregivers. This cycle happened 3 times until we reached the final version of the visual aid (Supplementary Figs. S1 and S2, and Fig. 2).

Fig. 2 Final version of the visual aid tool for informed consent before procedural sedation in the emergency department (usable for both pediatric and adults).

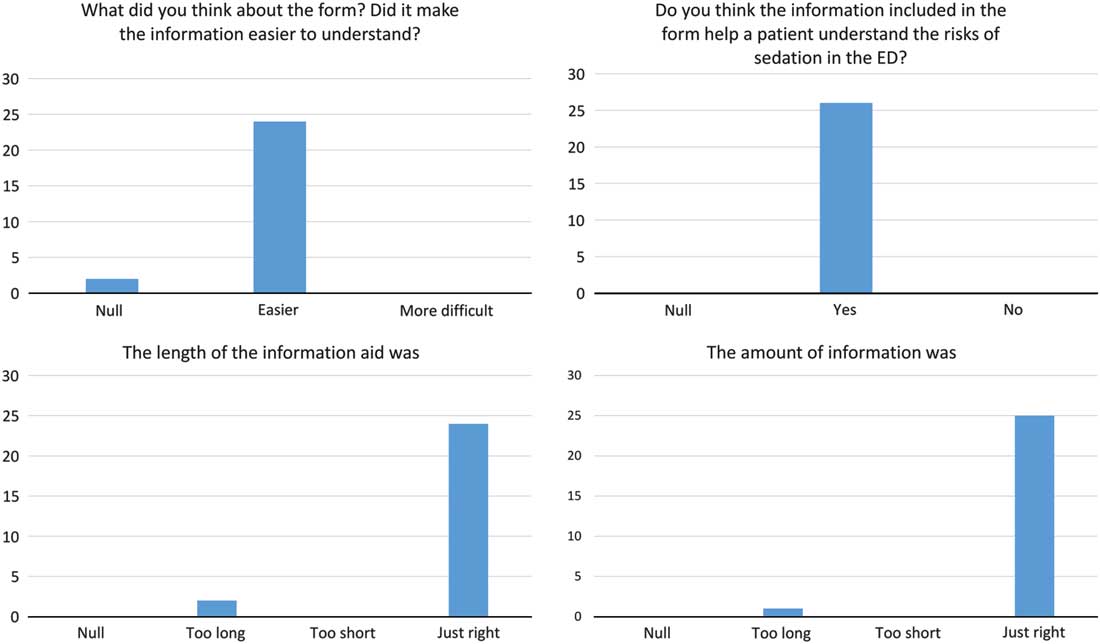

After arriving at the final version of the tool, we surveyed 26 physicians in our Emergency Department. We measured the difficulty to understand the information, whether doctors think the visual aid will help patients to understand the data, and the appropriateness of the tool’s length and the amount of information in it. The results were positive and are shown in Fig. 3. Our next steps include to obtain provider feedback on the frequency of visual aid utilization and the efficacy in relaying information, and to explore the consequences of using the tool, such as delays in care and refusal to perform the procedure.

Fig. 3 Results of the survey with Emergency Department (ED) Physicians.

Conclusion

Using a visual aid as an adjunct to risk communication in a stressful setting as the Emergency Department has a clear potential in facilitating the communication process. Contemporary evidence shows that the addition of visual displays of data to numerical formats increases accuracy and comprehension. In particular, icon arrays showed improved accuracy and understanding and were seen as more helpful, effective, trustworthy, scientific, and useful when compared with natural frequencies. Despite our visual aid being consistent with current recommendations on risk communication, a post-implementation evaluation of our visual aid is still needed.

An effort should be made to fully translate research findings until the end of the Research to Practice Continuum. In order to better translate knowledge into a useful and useable form for informed consent decisions in busy clinical practice, we created a visual aid to facilitate risk communication for Procedural Sedation and Analgesia in the Emergency Department. We believe that our experience can be replicated by other researchers and clinicians in the endeavor of translating the evidence into clinical practice.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Ms. Alyssa Frank for her design of the 5-step framework figure.

Authors’ Contribution

MFB and DC conceived and designed the study. MFB and LOJS drafted the manuscript and all authors contributed substantially to its revision with critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content.

Financial Support

The authors received funding through the Small Grant Program of Mayo Clinic Foundation for medical education and research (Award number SGP#91579004) and Mayo Clinic CTSA through grant number UL1 TR000135 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

Disclosures

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Supplementary Materials

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/cts.2017.303