Introduction

The role of tax in society is complex. As the Mirrlees Review (IFS, 2011: 2) noted, reiterating an observation made by Schumpeter over a hundred years ago (Reference Schumpeter and SwedbergSchumpeter, 1991 [1918]), tax systems have to suit the societies that create them. Nevertheless, the Mirrlees Review viewed tax policy choices largely through a utilitarian revenue-raising lens. It presented taxes and government spending as separate issues, rather than as a single system for government intervention in an economy (Kay, Reference Kay1986). Drawing on insights from Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) we outline a spend-tax cycle that reverses the relationship commonly assumed to exist in a tax-spend cycle, and explore the implications of this reversal for using tax as an instrument of social policy. This alternative framing has considerable appeal for understanding and designing taxes from a social policy perspective.

Awareness of tax and tax expenditures as social instruments in their own right does have some history (Surrey, Reference Surrey1974) but this is not how tax is commonly perceived. Tax as social policy is often ‘hidden’ to disassociate it from welfare hand-outs (Howard, Reference Howard1997) or to conceal how it favours high-income groups. The distributional effects of tax policy choices and instruments have certainly been investigated by social policy scholars (Sinfield, Reference Sinfield2000; Ferrarini and Nelson, Reference Ferrarini and Nelson2003; Avram, Reference Avram2018). Efforts to understand the social and political processes present in taxation and their social and political consequence have also been undertaken under the umbrella of the ‘new fiscal sociology’ (Barker, Reference Barker1992; Martin et al., Reference Martin, Mehrotra and Prasad2009; Reference Schumpeter and SwedbergSchumpeter, 1991 [1918]: 101). Other research has explored the strategies through which actors on the left and the right seek to build social movements to change taxation policy (Martin, Reference Martin2015; Seabrooke and Wigan, Reference Seabrooke and Wigan2015). Nevertheless, efforts to conceptualise the role and function of tax in society, including the possibilities arising from this by drawing on macroeconomic rationales and framings remain rare. The normative choices, agency and possibilities involved in the setting of tax policies have consequently often been obscured and received too little attention (O’Neill and Orr, Reference O’Neill and Orr2018). We place consideration of the role of tax in a macroeconomic context, so as to renew debates about tax as a potential instrument of social policy, while challenging social policy academics to consider what implications a spend-tax cycle has for how they conceive of and research the role and contribution of tax in society.

Tax is a component part of a country’s broader macroeconomic policy mix and does, therefore, have a macroeconomic function. A first step in developing an alternative conception of the functions and roles of tax within this context requires a sense of why tax as process involves more than simple utilitarian calculations about how to most effectively raise revenue to fund government expenditure. An exploration of the claims of MMT provides the macroeconomic foundations for such an alternative framing (Wray, Reference Wray2012; Murphy, Reference Murphy2015b). The first section of this article explores the potential roles and functions of taxation within the framework of MMT. Second, some opposing views are discussed. A third section considers the interaction between tax and ‘tax spends’ within the UK, applying an MMT lens. Finally, the tax reform possibilities that arise from this alternative understanding are presented in a concluding section.

Overall, our novel and original contribution is a counter-intuitive claim that the most important practical contribution of MMT lies in its potential to reframe how tax is thought about with implications for how tax systems can and should be designed. This emerges through MMT’s account of the process of money creation, the spend-tax cycle that results and the ‘cancellation’ function performed by tax. Cancellation refers to the fact that just as bank loan repayment cancels the money created by commercial bank lending, so too does tax payment cancel the money created by both government spending and private credit creation. The full implications of this for how tax should be conceived of in academic work and talked about in public debate as an instrument of social policy have not as yet been fully articulated. We move beyond the existing MMT literature, where both advocates and critics focus on money creation, government debt and inflation, with relatively little effort being made by either side to elaborate MMTs claims on tax or to establish their practical policy implications. For tax to play its cancellation role adequately, MMT scholars will need to theoretically elaborate a form of Modern Tax Theory (MTT) showing more fully how this function works, while developing policy tools and frameworks that can assess both the macroeconomic impact of tax policies and their social policy value, in terms consistent with MMT priorities (Murphy, Reference Murphy2019). We begin that process here with specific reference to social policy and encourage other scholars to further develop and apply these insights in future research.

We also go beyond existing social policy literature, which has identified that social tax expenditures (STEs), or tax spends (Kay, Reference Kay1986), represent foregone revenue through reliefs and credits as a new form of fiscal welfare to recipients (Howard, Reference Howard1997; Hacker, Reference Hacker2002; Morel et al., Reference Morel, Touzet and Zemmour2018). These STEs often favour higher income groups by incentivising savings, private health care, and private education, constituting subtle, yet significant transformations in welfare states and social citizenship, in a new mode of governing social policy through fiscal welfare incentives (Morel et al., Reference Morel, Touzet and Zemmour2018: 550). Monitoring the costs of STEs is limited and incomplete (Sinfield, Reference Sinfield and Greve2012) making them more politically acceptable than direct expenditures (Morel et al., Reference Morel, Touzet and Zemmour2018: 557). Under an MMT framing, conducting more systematic evaluations of STEs becomes imperative. MMT brings into relief that the problem with some STEs goes beyond mere lost revenue, to illuminate how they can interfere with macroeconomic integrity and stability more generally, by undermining tax’s cancellation function. By highlighting the limited macroeconomic rationale for such policies, the MMT framing also reveals starkly that the primary impact of using STEs to prioritise savings and unearned investment income, are their regressive social effects. We advocate harnessing MMT insights with new tools for assessing tax policies and administrative practices, including their potential system undermining consequences, such as our recent tax spillover framework (Baker and Murphy, Reference Baker and Murphy2019a), to evaluate the combined macroeconomic and social implications of STEs on a more systematic basis. Social policy research needs to be central to such efforts. We provide the first account of what MMT insights mean for a thoroughgoing tax policy agenda, including how this can inform the evaluation of STEs. At the same time, we illuminate how systematic evaluations of STEs are necessary, if MMT is to translate its macroeconomic insights into a meaningful practical tax policy agenda.

Tax and Modern Monetary Theory (MMT)

In the United States, MMT has recently risen to prominence because of its role in shaping proposals for a Green New Deal resulting in a series of high-profile media exchanges between Stephanie Kelton (Kelton, Reference Kelton2019) and Paul Krugman (Krugman, Reference Krugman2019), as well as Simon Wren-Lewis (Wren-Lewis, Reference Wren-Lewis2019) and Bill Mitchell (Mitchell, Reference Mitchell2019). Amidst these often-heated exchanges, MMT’s potential to broaden understandings and reframe public debate on the role of tax, especially in an era when experimentation with forms of quantitative easing has been widespread, has been lost. Scepticism about MMT has been commonplace, even among heterodox economists (Epstein, Reference Epstein2019). Unsurprisingly, as a result the implications of MMT’s macroeconomic understandings for tax have received little attention outside the inner MMT sanctum. We show that one of the most practically useful implications of the increasing prominence of MMT insights in public economic debate is that it provides a macroeconomic rationale and framing, which can help to renovate the social policy role of tax.

Expert tax activists have identified six possible roles tax can perform within an economy (Cobham, Reference Cobham2005; Murphy, Reference Murphy2015a). These are:

1) Reclaiming the money that the government has spent in the economy with the aim of controlling inflation;

2) Ratifying the value of money by creating demand for currency, through a requirement that tax is settled using the local currency of a country;

3) Redistributing income and wealth;

4) Repricing market failure, mainly to control externalities through Pigouvian taxes;

5) Reorganising the economy, through the fiscal policy mix;

6) Reinforcing democracy, by creating a public desire to influence how income tax is raised and spent, encouraging and motivating people to vote.

These roles are not without a theoretical foundation, or justification. In what follows we elaborate more thoroughly what those theoretical foundations and justifications are.

MMT is an approach that has challenged conventional macroeconomic understandings of the relationship between tax and government spending. Using national income accounting (Godley, Reference Godley1996) orthodox macroeconomic thinking assumes that government spending (characterised as G) is funded by tax revenue raised (T), with any deficit or shortfall being funded by borrowing (B). In this formulation it is frequently suggested that G should equal T, with political opprobrium reserved for excess borrowing (HM Treasury, 2017b: 4). These are powerful basic beliefs that have contributed to constrained social spending throughout Europe in an age of austerity after the financial crisis with deleterious social consequences (Taylor-Gooby, Reference Taylor-Gooby2012; Blyth, Reference Blyth2013; Matsaganis and Leventi, Reference Matsaganis and Leventi2014; Dowler and Lambie-Mumford, Reference Dowler and Lambie-Mumford2015; Edmiston, Reference Edmiston2014). Concerns over reduced tax revenues have fed into reduced GDP spending on health and social security in the UK for example (IFS, 2019: 5).

MMT challenges the propositions behind this logic and crucially reverses the sequencing underpinning it (Wray, Reference Wray2012). In the classic MMT formulation, a government with its own currency and central bank spends before it taxes, bringing the money through which taxes are paid into existence (Mitchell et al., Reference Mitchell, Wray and Watts2019: 124). Government spending on the basis of available central bank credit, is, as with all money creation, a process that does not require the existence of prior deposits in a bank (McLeay et al., Reference McLeay, Radia and Thomas2014) or, in the case of a government, revenue raised in advance by taxation. If a government insists on taxes being paid in sovereign currency, that currency must, in the MMT view, first be created to enable those taxes to be paid (Wray, Reference Wray2012: 47Footnote 1).

In the MMT understanding, this ‘spend and tax cycle,’ as opposed to a ‘tax and spend cycle’ has three primary implications. First, tax gives a currency its value (Mitchell et al., Reference Mitchell, Wray and Watts2019: 137). A government accepting its own currency in the settlement of tax creates demand for the currency it issues and gives meaning to the promise to pay printed on bank notes as the foundation of modern money. Second, the requirement that tax be paid using this currency usually requires that the currency in question be used as a medium for exchange within the economy (Murphy, Reference Murphy2015a: 64Footnote 2). Third, the raw mechanics of government spending when a national sovereign currency and national central bank exist, involves crediting the accounts of actors in receipt of that government spending. Tax revenue is consequently not prior, but subsequent to spending.

The account presented in the sequence above is a central tenet of MMT. It is underpinned by a reality in which all money, excluding notes and coins, is created by bank lending, as has been acknowledged by the Bank of England (McLeay et al., Reference McLeay, Radia and Thomas2014). MMT applies this understanding to the distinct relationship between a government and its central bank. It argues first that a government, unlike a household (or a commercial bank) creates the currency being used in a jurisdiction, and declares it sovereign. Second, whereas households and banks are constrained by their income and the funds required for solvency, governments can through their central banks issue currency and create money. Third, according to MMT therefore, G need not equal T, because money can be created at will to settle government debt by the government issuing instruction to the central bank to make settlementFootnote 3.

The formulation below can be seen as an interpretation of orthodox economics which posits that the basic national income functions relating to tax are as follows:

$${\rm{G = T + \Delta B}}$$

$${\rm{G = T + \Delta B}}$$where ΔB is the change in government borrowing in a year.

MMT expresses this function as (Mitchell et al., Reference Mitchell, Wray and Watts2019):

$${\rm{G = T + \Delta B + \Delta M}}$$

$${\rm{G = T + \Delta B + \Delta M}}$$where ΔM is the change in the quantity of government money created in a period.

Government created money (M) can in this context simply refer to an overdraft it runs at its central bank. However, given that these are generally illegal (Jácome et al., Reference Jácome, Matamoros-Indorf, Sharma and Townsend2012) in the contemporary era such practices have taken the form of quantitative easing, where the government instructs the central bank to purchase assets including government debt. In the UK this has led to the government effectively owning (via the Bank of England) £435 billion of its own debt, which withdraws it from effective circulation as a result and cancels all interest costs upon it. The Bank of England describes this as ‘new money’ (Bank of England, 2019), confirming it is ‘M’.

Just as in the current Bank of England explanation of money creation where loan repayment withdraws money from circulation and effectively cancels it (McLeay et al., Reference McLeay, Radia and Thomas2014), so too does the payment of tax contribute to the cancellation of the debt that a government creates in the system when it spends in the MMT explanation of the government revenue cycle. This cancellation process means that tax acts to reduce spending capacity in an economy (money withdrawal), simultaneously restraining demand (Fullwiler et al., Reference Fullwiler, Grey and Tankus2019) and contributing to price stability (Mitchell et al., Reference Mitchell, Wray and Watts2019: 323). Freed from a fixation with the revenue raising efficiency of individual tax measures, the MMT position casts tax in a more overt and active countercyclical macroeconomic stabilisation role. As we will show through consideration of the UK case, this also potentially allows this cancellation role to be combined with the use of tax to promote social policy objectives considered desirable by society and policy makers alike.

In the existing MMT literature, however, accounts of the potential social policy role of tax remain thin, focusing almost entirely on the so-called ‘jobs guarantee,’ with full employment the primary MMT policy objective (Wray et al., Reference Wray, Dantas, Fullwiler, Tcherneva and Kelton2018). MMT effectively contains more far reaching intellectual justification for evaluating so called STEs, but developing a form of MMT derived modern tax theory (MTT), would assist in this endeavour (Murphy, Reference Murphy2019).

Critics have argued that MMT overestimates the tax rates that the public are willing to tolerate (Palley, Reference Palley2015). U.S. Conservative Bruce Bartlett (Bartlett, Reference Bartlett2019) suggests that MMT is a kind of Laffer Curve for the Left, permitting spurious magical thinking to justify increased public spending without considering inflationary consequences. MMT economists use the logic of sectoral accounting balances to assert the non-inflationary nature of their case, but their relative lack of engagement with inflation as an expectations driven social phenomenon, rather than as a mathematical proposition, is a potential Achilles’ heel. Nevertheless, the implications of MMT insights on the sequences of the spend-tax cycle, where tax is not confined to revenue-raising and tax revenue is not prior to government spending, are worthy of further exploration.

Our focus here is on the sequential insight that governments do not first need access to tax revenues to spend. This enables tax policies to be more fully viewed and understood in terms of a broader range of macroeconomic and societal functions. The implication of such an observation is as much political and discursive, in terms of widening public debates, political narratives and shifting mind-sets, as it is economic and technical. It also has potential consequences for the research agendas of social scientists focused on tax. Tax policy decisions become less about their utilitarian revenue raising merits and more about their wider macroeconomic effects – as well as the extent to which they enable governments and societies to realise objectives and priorities that the democratic process and societal deliberation deem important – or their social purpose and the kind of economic system and social settlement to which they contribute (Baker, Reference Baker2018).

One example, of the kind of mind-set shift these MMT derived observations facilitate is provided by corporation tax. In the UK, public debate focuses on the appropriate level of corporation tax to most efficiently raise revenue (IFS, 2017; Jackson and Houlder, Reference Jackson and Houlder2017). But this is a limited way of assessing the merits of particular policies. While corporation tax can be an important revenue raising device, especially in developing countries, the reasons for its original introduction go far beyond revenue raising capacity. Corporation and capital gains taxes have a long-standing defensive rationale. That is they reinforce and buttress other direct taxes such as income tax, or social security, maintaining the integrity and functioning of tax systems as integrated entities. Without these taxes, it becomes easier for individuals to present income as a capital gains, or to transfer it to a company structure, leaving it untaxed.

Such rationales were cited in the legislative debates surrounding the introduction of corporation tax bills in both the United Kingdom and the United States (Bank, Reference Bank2001; Baker and Murphy, Reference Baker and Murphy2019a: 182). Once we begin to think in terms of a buttressing function for corporate taxes limiting potential leakages in tax systems and holding them together as entire entities, evaluations of corporate taxation can shift from a focus on revenue raising efficiency, to assessments of whether they fulfil their original intended purpose of reinforcing a tax system as a whole (Baker and Murphy, Reference Baker and Murphy2019a). Likewise, the ‘regulatory rationale’ for corporate tax proposed by legal scholars sees corporation tax as a mechanism for increasing the accountability and regulating the activities of corporate managers (Avi-Yonah, Reference Avi-Yonah2004). Tax in this interpretation is about shaping economic activity and social relations. It fulfils a social purpose distinct from revenue raising. It also means a range of tax practices, policies and reliefs need to be evaluated to assess whether corporate taxes fulfil this function (Baker and Murphy, Reference Baker and Murphy2019a).

In public debate and to a lesser degree scholarship, these questions of designing and assessing taxes to fulfil a broader social purpose, remain marginalised and obscured by the fixation on tax as a revenue raising device. MMT provides intellectual foundations to help overcome that fixation.

Criticism of the MMT approach

Some criticisms of MMT positions have already been noted. Among the most relevant is that using taxes for macroeconomic stabilisation purposes is difficult in practice: taxes are hard to change at short notice (Krugman, Reference Krugman2019). Likewise, it has been suggested governments are reluctant to increase taxes due to electoral pressures (Epstein, Reference Epstein2019). In this reading MMT may underestimate the political economy constraints on using tax for macroeconomic stabilisation. However, a sustained period in which interest rates have been at, or close to the zero lower bound also increases pressures for tax to play such a role. Nor do these objections detract from the fact that some STEs can have destabilising macroeconomic effects.

In the UK, the work of Jonathan Portes (Portes, Reference Portes2019) and Simon Wren-Lewis (Wren-Lewis, Reference Wren-Lewis2018) has shaped the Labour Party’s Fiscal Credibility Rule (Labour Party, 2017). This is intended to provide reassurance to voters that day-to-day spending will be balanced and borrowing will only be used to fund investment (Ahmed, Reference Ahmed2016). In essence, the assumption that tax is needed to fund government spending (T=G) is respected, with some allowances for minimal levels of government debt. Both authors have defended their positions and rejected MMT criticisms of their approach, by citing the need for independent authorities and rules that tie a government’s hands, as a means of providing reassurance to voters that government debt will not be excessive. This reflects the most prominent critique of MMT that it places too much faith in governments to exercise restraint (Epstein, Reference Epstein2019) and ignores ‘political economy difficulties’ where politicians are tempted to use monetary policy for electoral purposes (Palley, Reference Palley2015).

Such critiques have largely been aimed at questioning the political and policy realism of adopting MMT policy prescriptions, such as those proposed by American Congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (Ocasio-Cortez, Reference Ocasio-Cortez2019) in a US version of the Green New Deal based on green infrastructure quantitative easing (Murphy and Hines, Reference Murphy and Hines2010; Green New Deal Group, 2013; Murphy, Reference Murphy2015b). The stakes are certainly high in terms of the potential of MMT to achieve public policy objectives. But, given their focus, these critiques have largely overlooked the implications of the sequences of an MMT spend-tax cycle. In this sense, the reservations they raise should not preclude efforts to consider more thoroughly the implications of MMT insights for tax.

MMT, tax allowances and reliefs and the implications for UK tax policy

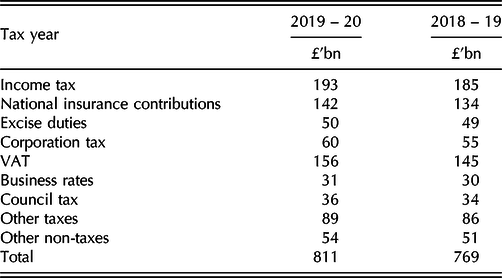

In this section we examine how an MMT perspective can help to illuminate distortions within the UK tax system and point a pathway to reform. The governance of the UK tax system and the debates around it, as we have seen, focus largely on revenue raising. Table 1 shows forecast revenues for the tax years 2018/19 and 2019/20.

Table 1 Official Published Public Sector receipts (net of reliefs)

What is not made clear in the official data, such as that in Table 1, is that the stated figures are net of tax reliefs and allowances. There are thought to be more than 1,000 of these allowances (National Audit Office, 2014), the cost of which are estimated to be at least £425bn in 2018/19 (HMRC, 2019a).

Allowances are given for a great variety of reasons (Hills, Reference Hills2015; Xu and Joyce, Reference Xu and Joyce2019). The individual personal allowance, which provides an annual tax free sum to all who have income subject to income tax is the most expensive allowance, costing £107bn. The zero rating of food for VAT purposes, which is intended to ensure all have access to food at a reasonable price, costs £18.6bn a year. Tax relief on the investment by business in assets, irrespective of their social value, costs almost as much, at £18.1bn, while tax reliefs for pensions cost at least £43.7bn pa, and another £10bn more when the tax exempt status of pension funds is taken into account. Other tax reliefs for savings, such as those on Individual Savings Accounts, cost £4.6bn in income tax foregone, and more when capital gains tax is allowed for. Not taxing capital gains on people’s homes costs £27.2bn a year. Inheritance tax exemptions cost over £22bn and the tax only collects £5.5bn as a result. In the circumstances the exemption of disability living allowance from tax at a cost of £1.1bn is almost insignificant, and is dwarfed by the cost of the VAT exemption of education at £4.1bn a year, most of the benefit of which goes to private schools.

The implication of these allowances is that the data in Table 1 is misstated. It could, when allowances and reliefs are provided for be stated as noted in Table 2.

Table 2 Tax revenues for 2018 – 19 tax year taking the cost of tax reliefs and allowances into account

The actual potential tax base created by UK tax law, based on this method of calculation, is almost £1.2trn per annum, or 56 per cent of GDP based on Office for Budget Responsibility data (Office for Budget Responsibility, 2019: 67). However, of this sum at least 35 per cent (and maybe more) is then forgone by government choice. This highlights the significance of tax spends (Kay, Reference Kay1986), or STEs, and also makes clear that the costs of redistributing income and wealth, repricing market failure and reorganising the economy (Murphy, Reference Murphy2015a) are already implicit within the tax system but are almost never identified as such because the data in Table 2 is never made available by the UK government as a basis for policy discussions (McDaniel and Surrey, Reference McDaniel and Surrey1985; Corlett, Reference Corlett2015).

From an MMT perspective this omission is problematic for two reasons. First, lack of coverage of these allowances and reliefs prevents a full and proper consideration of their social implications and their appropriateness. Such consideration would allow a greater degree of finesse in targeting potential tax revenues for distributional objectives that simple adjustment of rates alone cannot provide. Likewise, their effectiveness in performing the cancellation function of tax by reducing demand and sectoral inflationary pressures is similarly obscured by the minimal oversight of STEs (Sinfield, Reference Sinfield and Greve2012). Rather than ignoring political economy difficulties therefore, MMT usefully highlights biases in tax policy in terms of redistribution and inequality that simultaneously act to hamper the utility of tax policies’ cancellation function.

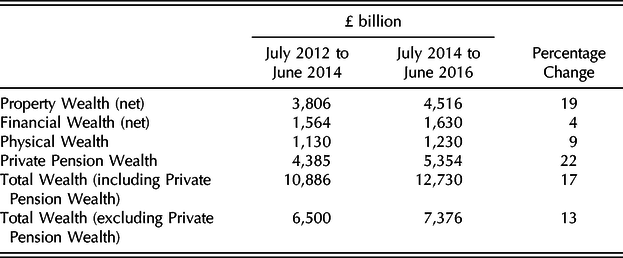

A second reason emerging from an MMT framing is that many of these allowances and reliefs exist to encourage savings. They can increase individual economic resilience to some extent, but as MMT shows, savings are not required to fund investment. Instead MMT argues that investment can always be, and usually is, funded by bank created credit. Yet the UK tax system is designed to incentivise savings with a consequent considerable increase in the value of those savings, as Table 3 shows: this savings wealth is very concentrated within society (see Figure 1).

Table 3 Breakdown of aggregate total wealth, by components Great Britain, July 2012 to June 2016

Source: ONS (2018).

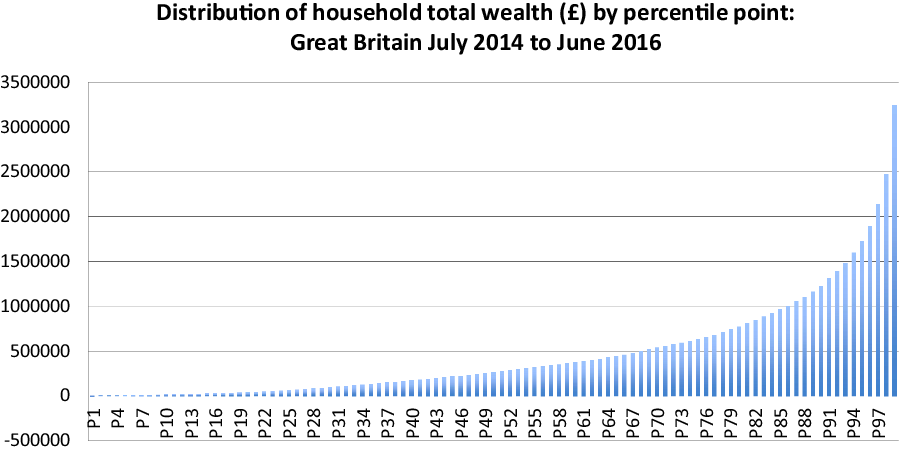

Figure 1. Distribution of household wealth by percentile points.

Source: ONS (2018).

This distribution means that the bottom 10 per cent of households have total wealth of £13,900 or less; median total household wealth is £262,400; the top 10 per cent of households have total wealth of at least £1,224,900 and the top 1 per cent of households have total wealth of £3,243,400 or more (ONS, 2018).

Tax heavily impacts on this distribution: as Table 3 shows in 2016, 35 per cent of all wealth was property, with much of that family homes exempted from a charge to capital gains tax, usually irrespective of size or value. A further 42 per cent is in pension funds, which enjoy expensive tax subsidies. The annual cost of pension subsidies in 2017/18 (the most recent available data) amounted to £54.7bn (HMRC, 2019c: 29). In addition, of the net financial wealth of £1.6 trillion, more than £500 billion was represented by ISA account balances (HMRC, 2019b: 13). In total, therefore, it is likely that 81 per cent of UK personal wealth is held in heavily tax incentivised assets. The tax system – which incentivises these assets at a cost of more than £86n a year – is not neutral in the process. This analysis suggests that about 20 per cent of tax reliefs might be used in ways that promote inequality in the UK, while serving little macroeconomic purpose from an MMT perspective. This alone cannot, however, explain the increase in savings noted in Table 3, which suggests that savings increased by more than £1.8trn in just two years, or by 17 per cent.

A full explanation of that requires acknowledgement that M can be created in the form of quantitative easing (QE). In the UK, QE has had as its goal an increase in the price of the remaining bonds in the market, which was necessary to keep interest rates on those bonds low (Bank of England, 2019). This process of deliberately inflating the value of government bonds inevitably increased the financial worth of those who owned them, effectively delivering very significant gains to a small group in society, made up of the already wealthyFootnote 4.

Four points arise from the preceding discussion. Firstly, existing tax reliefs have fuelled an increase in wealth inequality in the UK (Rowlingson and McKay, Reference Rowlingson and McKay2012; Bell and Corlett, Reference Bell and Corlett2019; Hebden et al., Reference Hebden, Palmer and Tyldesley2019). Secondly, MMT sees this as misguided because it is largely based on a premise that savings are required to fund investment. Thirdly, no other part of the tax system is currently compensating for the resulting inequalities that these subsidies create. Fourth, these reliefs also risk macroeconomic instability by stoking asset inflationary pressures in particular sectors. The MMT framing, when applied in this wayFootnote 5, does create a rationale for reform of the UK tax system in a fashion that places social policy considerations centre stage, but also strengthens the intellectual case for more systematic evaluations of STEs, using an MMT framing.

MMT’s insights on the spend-tax cycle and the resulting cancellation function, also effectively elevate social policy criteria as the basis for evaluating tax measures’ usefulness. In the UK, reforming pension tax reliefs that cost more than £50 billion a year and the potential removal of ISA tax reliefs are already the subject of debate (House of Commons, 2018). Other potential measures include ending inheritance reliefs for agricultural property, because they can inflate land values, while ensuring the continuity of land ownership by absentee landlords. As the data discussed earlier revealed, reliefs that treat investment, savings and inheritance income favourably in the UK have increased savings and accumulated assets, but have also exacerbated income and wealth inequality. From an MMT perspective, tax reliefs that encourage and preserve pools of capital in this way also potentially undermine the cancellation function of taxation, while risking asset inflation.

A forthcoming modified proposal from the UK Green New Deal Group suggests that ISA and pension reliefs, rather than being abolished altogether, could have attached to them a condition that funds saved through these mechanisms be invested in activity intended to tackle climate crisis. In this creative way, tax reliefs can be restructured and placed at the wider service of re-ordering the financial system towards mitigating climate change. In the United States, similar tax proposals have been developed under the Green New Deal proposals of Senator Bernie Sanders. They include increasing taxes on the fossil fuel industry to reduce production levels. Simultaneous investments in 20 million new jobs to help with infrastructure and energy transitions would in turn be partially cancelled by the fossil fuel industry tax and extra income tax generated by new jobs. A new proposed ‘work opportunity tax credit’ for employers who employ workers displaced by the energy transition would constitute a relief simultaneously encouraging employment and reduced fossil fuel use.

These examples illustrate how an MMT framing can inform the re-design of systems of tax reliefs on a more systematic basis so as to more effectively serve important social policy priorities. One tool that would support such a shift and provide social policy scholars with an additional source of data is tax spillover assessment (Baker and Murphy, Reference Baker and Murphy2019a). A tax spillover is the impact one aspect of tax policy has on the available tax base within the same state, or other states (IFS, 2011; Nanda and Parkes, Reference Nanda and Parkes2019). As well as discouraging states from pursuing policies that can be shown to harm the tax bases of other states, spillover assessments consider the relationships between different features of the same tax system and ask whether they reinforce or undermine those elements (domestic spillovers). In MMT terms, this enables a fuller picture to be drawn of whether particular policies within a tax system undermine the withdrawal function of the tax system in its entirety. At the same time, such assessments help to illuminate whether certain current tax practices have an implicit and often hidden social policy bias.

Applying a spillover assessment tool kit in a full UK assessment, revealed that both capital gains and corporation tax provisions encouraged the shifting of income out of the income tax base (Baker and Murphy, Reference Baker and Murphy2019b: 5). At the same time, a whole range of exemptions, allowances and reliefs were found to provide favour to income earned from wealth rather than from work, further incentivising the under reporting of income (Baker and Murphy, Reference Baker and Murphy2019b: 4). A recommendation emerging from that assessment was that all allowances and reliefs offered in the UK should be systematically evaluated to determine: their cost; their economic effectiveness; the benefits arising from continuing to offer them; and any impact of their withdrawal. The need for systematic evaluations of STEs has been identified by the social policy literature (Sinfield, Reference Sinfield and Greve2012; Morel et al., Reference Morel, Touzet and Zemmour2018), but locating such evaluations within an MMT framing would enable them to serve a dual macroeconomic and social policy function, leading to more accurate assessments of a tax regime’s capacity to fulfil its cancellation function.

Conclusions: tax reforms suggested by modern monetary theory and spillover analysis

In this article, we have sought to show that an MMT framing strengthens arguments for tax reform that would simultaneously be more effective in maintaining the non-inflationary macroeconomic integrity of the spend-tax cycle, while achieving social policy objectives of employment creation, encouraging a green energy transition, and reducing inequality. A crucial, but often neglected, question in designing the configuration of tax policies and practices is whether those practices reinforce, or undermine, parts of the same tax system, or administration (Baker and Murphy, Reference Baker and Murphy2019a). Using MMT insights on money creation and the resulting spend-investment/tax cycle, we have illustrated how certain tax reliefs incentivise savings. From a macroeconomic perspective, that is not only questionable but can also spill over to undermine other parts of the same tax system, while producing an expansion in wealth inequality. An MMT framing when harnessed with a direct application of spillover analysis to the UK demonstrates that this is a double ill from both a macroeconomic and social policy perspective (Baker and Murphy, Reference Baker and Murphy2019a, Reference Baker and Murphy2019b).

The analytical steps taken in this contribution point to a potential tax reform agenda, which would achieve useful macroeconomic and social policy objectives. The thumbnail sketch we have provided is intended to provoke others to further consider how tax reforms can serve a dual macroeconomic and social policy purpose. For example, taxing capital gains at the same rates as in the 1980s and similar moves to restore corporation tax to pre-2010 levels would discourage the diversion of income into company structures, which undermines both income tax, and potentially the cancellation or withdrawal function of the tax system as a whole. Generous capital gains tax allowances on buy-to-let properties, that potentially fuel asset inflation and reduce access to affordable homes, could be substantially reduced. The proceeds from reduced allowances could then be invested in social housing. The fact that national insurance charges in the UK apply only to income from work, but not investment income, also make it a potential target for reform based on the application of similar MMT logics. At present, those who work for a living pay considerably more tax on identical levels of income than those who receive income as a return on investments of a variety of forms. When the saving process is not required to drive investment, the socially regressive nature of such policies becomes much clearer.

Harnessing the insights of MMT to new governance tools, such as tax spillover assessments, can therefore help to show how tax can be used and designed to perform important creative social policy functions, and at the same time be made more effective in macroeconomic terms. The proposals we highlight here are a mere pointer, but they are indicative of the kind of tax reform agenda that the application of an MMT lens and its mind-set shift can generate. Re-engineering tax systems to serve social policy objectives in the light of these insights is an interdisciplinary undertaking. Social policy researchers can and should be at the forefront of informing such an undertaking, but they can be aided by an engagement with, and a fuller elaboration of, the MMT perspective on tax.

Acknowledgements

We offer our thanks to Professor Len Seabrooke of Copenhagen Business School and two anonymous reviewers for comments made on drafts of this article.