Diet and nutrition in early childhood has been associated with the risk of chronic disease later in life(1). Therefore, it is important that healthy dietary behaviours are established in young children as these are likely to track through adolescence into adulthood(Reference Kelder, Klepp and Lytle2). In the past decade, primary school-aged children have been identified as having poor quality diets which are typically high in fat and sugar, whilst being inadequate in wholegrains, fruit and vegetables (FV)(Reference Florence, Asbridge and Veugelers3). Poor quality diets can be attributed to many factors including lack of access to healthy options, individual taste preferences and lack of food literacy by both parents and children(Reference Evans, Cleghorn and Greenwood4). This emphasises a need for programmes to target these modifiable factors.

The Ottawa Charter recommends that in order to be successful, health promotion interventions require supportive environments. This socioecological approach to improving health-related behaviours highlights the inter-relatedness of people, health and the communities in which they live(5). Settings-based approaches that focus on creating supportive environments have been shown to be effective in influencing health-related behaviour change. Schools provide a logical setting in which to promote healthy eating behaviours as they have been shown to be particularly influential on children’s eating patterns(6–8). A recent review of twenty-seven school-based interventions reported moderate, but significant, effects on fruit intake; however, there is less evidence for beneficial effects on increasing vegetable intake(Reference Evans, Cleghorn and Greenwood4). It has been identified that most health behaviours and eating habits are established before the age of 15 years(Reference Dinubile9); therefore, it is important that public health interventions target children in their earlier years to maximise their chances of developing lifelong positive health outcomes.

Experiential learning is defined as ‘learning from life experience’, rather than using didactic or theoretically based teaching methods that assess outcomes based on cognitive skills and academic knowledge(Reference Kolb10). A systematic literature review was conducted to investigate the evidence to date on experiential nutrition interventions aimed at primary school-aged children and to identify the key characteristics of successful programmes that influenced nutrition-related cognitive and behavioural outcomes (nutrition-related knowledge, preferences and attitudes; self-efficacy; and dietary intake) in this age group.

Methods

The study protocol was registered with PROSPERO (CRD42017072822)(11), and the findings were reported according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta Analyses guidelines(Reference Moher, Liberati and Tetzlaff12).

Search strategy

The bibliographic databases that were searched included CINAHL, Scopus, Web of Science, Medline and Academic Search. The search was performed up to 30 June 2020. Search terms included: ‘Food insecurity’ OR ‘Food security’ OR ‘Health knowledge’ OR ‘Health literacy’ OR ‘Health education’ OR ‘Health attitudes’ OR ‘Health behavio#r’ OR ‘Health practices’ OR ‘Food knowledge’ OR Attitudes OR practices OR knowledge AND School* AND Nutrition* OR Food OR Healthy eating AND Program OR Project OR initiative. Search terms were adapted according to individual database requirements. In addition, citations and reference list searches were also conducted. An example of the search strategy is shown in Supplementary Table 1. Although food security was listed in the original PROSPERO protocol registration, lack of quantifiable and comparable measures of food security meant that this outcome was not included in the final review.

Eligibility criteria

Citations were collated into EndNote version X9(Reference Thomson13), and duplicates removed. Abstracts were reviewed by researchers (T.C. and N.D.) against inclusion criteria to determine eligibility of studies. The full-text articles of all potentially relevant citations were accessed and reviewed. Discrepancies were resolved by consensus or adjudication by other members of the research team (K.C. and K.W.). Criteria for inclusion were experiential-based nutrition interventions conducted in primary school settings, including children aged 5–12 years, and reporting in English language.

Studies were excluded if: (1) the programme intervention was paired with a physical activity component (only outcomes related to nutrition interventions were targeted); (2) not predominantly experiential in nature, meaning that effects may have been attributable to other non-experiential aspects of the intervention; (3) outcomes reported not relevant to the research question; (4) did not report baseline and post-intervention measures; (5) theoretical/educational nutrition intervention (except in the case of being accompanied and supported by an experiential component); (6) not, at least partially, conducted in the grounds of a primary school setting and (7) intervention was designed for medical conditions, such as diabetes or obesity. Eligible study designs included randomised controlled trials (RCT), cluster RCT, quasi-experimental design and cohort studies.

Intervention types

Interventions were limited to experiential programmes in primary school settings that targeted beneficial changes in nutrition knowledge, preferences, attitudes, self-efficacy and dietary intake. Interventions included: School gardens; food provision; taste testing; cooking lessons; multi-component or other, relevant and interventions.

Outcomes

Health-related outcomes targeted in this review included dietary intake, nutrition-related knowledge, preferences or attitudes and self-efficacy. Measures for dietary intake were those reported in grams or servings per day from self or parental reports obtained through dietary recall, food diaries and/or FFQ. Measures of knowledge included response-scale questionnaires, tests on food-related knowledge or recognition of healthy food items. Measures for attitudes, preferences and self-efficacy were response scale questionnaires.

Interventions were deemed to be successful if they reported significant changes in one or more of the outcomes of interest and demonstrated reach (sample size of at least 100 and some degree of generalisability). Studies that were classified as being successful were scrutinised for key characteristics of the intervention that contributed to their success, and this information is presented in order to inform recommendations for future programmes. This data extraction was performed independently by two researchers (T.C. and K.C.) who then reached consensus.

Data extraction

Data collection methods followed the Cochrane review methodology(Reference Noyes, Booth and Hannes14). Data were tabulated in a summary of findings (Table 1), according to the type of experiential activity.

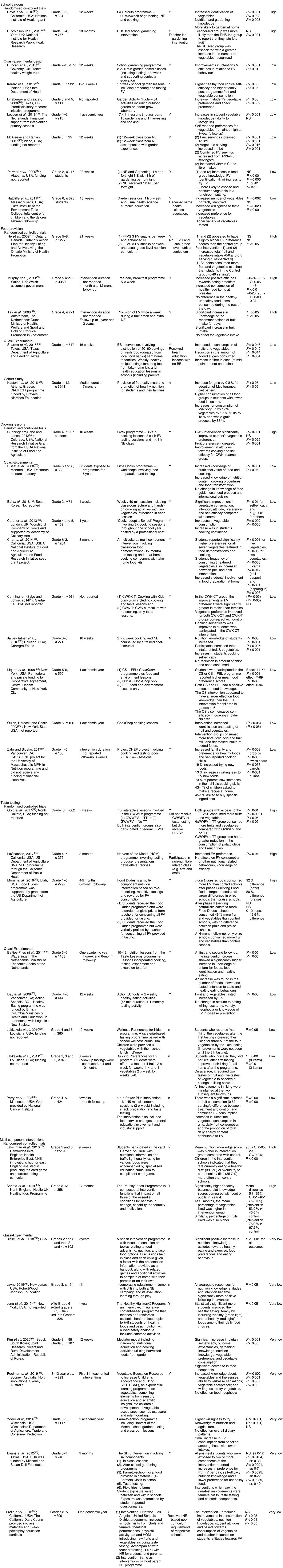

Table 1. Summary of findings: studies on experiential nutrition interventions in primary schools

RHS, Royal Horticulture Society; FV, fruit and vegetable; NE, nutrition education; FFVS, FV snack programme; BB, Brighter Bites; CWK, Cooking with Kids; GWWFV, Go Wild with Fruits and Vegetables; TT, taste testing; FFVSP, Fresh Fruit and Vegetable Snack Program; SHK, Sprouting Healthy Kids; LA, Los Angeles.

Assessment of methodological quality

The GRADE criteria were used to assess quality of evidence(Reference Hill15). Only RCT and cluster-RCT study designs could be assigned a high-quality rating, while quasi-experimental and cohort studies were assigned a low or very low rating. Discrepancies in quality allocation were resolved by consensus between members of the research team (T.C., K.C. and K.W.). The strength of evidence of studies was evaluated using the National Health and Medical Research Council’s Levels of Evidence Manual.

Results

Study selection

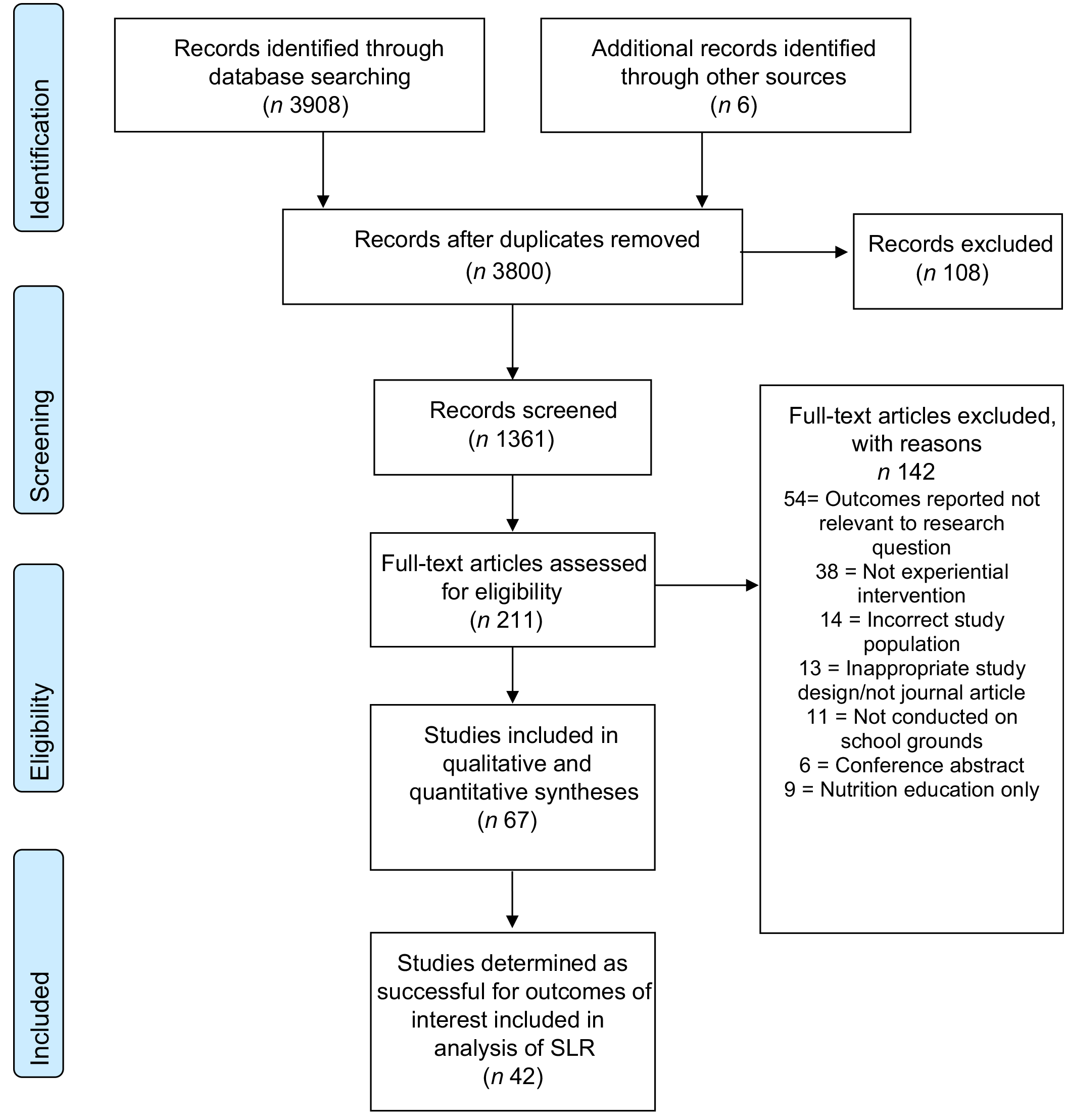

The database search identified 3908 articles, with an additional six studies being included through manual searching of citations and grey literature. After refinement by title, 1361 articles were further investigated by reviewing their abstracts, thereafter, leaving 211 relevant articles for which full texts were extracted. Sixty-seven articles were identified to be relevant regarding experiential nutrition interventions and reported on the outcomes of interest. Of those, forty-two were determined as being successful and were reviewed in-depth (Fig. 1). Of the successful interventions, eleven were cluster-randomised trials (National Health and Medical Research Council’s level II), thirty quasi-experimental design trials, including pre-post studies (level III-2) and one cohort study (level III-2), as shown in Table 1. Twenty-five studies that were considered to be unsuccessful, with reasons for this classification, are summarised in Supplementary Table 2 (Reference Macnab, Stewart and Gagnon16–Reference Gatto, Ventura and Cook40).

Fig. 1 Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta Analyses flow diagram for systematic literature reviews

Experiential interventions and characteristics

Studies were dated from 1998 to 2020 and were conducted in Australia, UK, USA, Netherlands, Canada, South Korea and Greece. Study populations varied from 77 to 2519. Successful interventions included school gardens (n 9)(Reference Davis, Martinez and Spruijt-Metz41–Reference Hutchinson, Christian and Evans49), food provision (n 5)(Reference Sharma, Markham and Chow50–Reference Kastorini, Lykou and Yannakoulia54), taste testing (n 8)(Reference Battjes-Fries, Haveman-Nies and Renes55–Reference Perry, Bishop and Taylor62), cooking lessons (n 10)(Reference Bisset, Daniel and Paquette63–Reference Bai, Kim and Han72) and other multiple component interventions which included additional activities (n 10)(Reference Evans, Rutledge and Medina73–Reference Sahota, Christian and Day82) such as farmer visits, Harvest of the Month Program or a nutrition education card game. Cognitive-based outcomes included food and nutrition-related knowledge, preferences, attitudes and self-efficacy. Behavioural outcomes included student or parent-reported dietary intakes of FV, wholegrains, dairy products, total fibre, added sugars, total fat and vitamin C. Of the school gardening programmes, nine of twenty identified studies were determined as successful, with the interventions typically lasting for 10–15 weeks(Reference Davis, Martinez and Spruijt-Metz41–Reference Ratcliffe, Rogers and Goldberg48). Gardening interventions were the most intensive in relation to time and experiences, provided that they were often accompanied with harvesting, cooking and tasting of the produce grown(Reference Davis, Martinez and Spruijt-Metz41,Reference Duncan, Eyre and Bryant42,Reference Leuven, Annerie and Leuven45–Reference Ratcliffe, Rogers and Goldberg48) , in addition to tailored classroom nutrition education. The two highest quality studies (RCT) for which the evidence was strongest were a 12-week Little Sprouts programme (n 304)(Reference Davis, Martinez and Spruijt-Metz41) and an 18-month Royal Horticulture Society-led programme (n 777)(Reference Duncan, Eyre and Bryant42). LA Sprouts is a 12-week gardening, nutrition and cooking intervention comprising 90 min/week that improved knowledge of nutrition and likelihood to garden at home, while the UK Royal Horticulture Society-led programme was successful at increasing knowledge of vegetables in the groups randomised to receive instruction from external professionals rather than those led by teachers. The remaining seven studies were of low quality and mostly demonstrated improvements in preferences for FV and willingness to try new ones, with only three studies measuring actual consumption of these foods(Reference Kararo, Kathryn and Neil43,Reference McAleese and Rankin46,Reference Parmer, Shannon and Struempler47) .

All eleven of the gardening studies that were deemed as being unsuccessful, because of not achieving significant changes in the outcomes of interest (n 8) or having small sample sizes or lacking generalisability (n 3), were quasi-experimental and rated as either low (n 4) or very low (n 7) quality (see online supplementary material, Supplemental Table 2). Characteristics of these studies are informative and presented briefly here. A pilot project(Reference Macnab, Stewart and Gagnon16) implemented in an inner city neighbourhood of Johannesburg, South Africa that is home to a large community of migrants did not improve students’ dietary diversity or nutritional status over a 1-year period, as high year-round yield of produce was not attained. Two key learnings from the project were: (1) a need to change school culture by incorporating the garden as a catalyst for whole of school development; a fundamental concept of the WHO health promoting school model that has shown to be modestly successful(Reference Langford, Bonell and Jones83); and (2) long-term engagement with the garden to ensure sustainability, with a recommended minimum of 3 years in order to impart skills, mentor across multiple growing seasons and have time to adequately integrate a garden into the culture of the school.

The Australian Stephanie Alexander Kitchen Garden Program consists of a minimum of a 45-min garden class and a 1·5-h kitchen class every week as an ongoing part of the school curriculum. Garden and kitchen classes are supervised by specialist staff with prior qualifications and experience in horticulture and hospitality, respectively, who are assisted by the classroom teacher. Surprisingly, in a non-randomised comparison of six schools receiving the programme and six control schools, neither child well-being (assessed through self-reported, health-related quality-of-life questionnaires) nor school performance differed between intervention and control schools. However, recruitment bias was evident in that five of the six control schools that agreed to participate had started their own edible gardens by commencement of the study. Thus, many of the children in the control schools also participated in gardening (and some cooking) activities, although for substantially fewer hours and in a less structured way than in the intervention schools.

A pilot of the LA Sprouts programme examined its influence on dietary intake, obesity risk and nutrition-related behavioral and psychosocial parameters in predominately Latino elementary students in Los Angeles(Reference Gatto, Ventura and Cook40). A weekly 45-min interactive gardening lesson was taught by a bilingual Latina-certified master gardener. The exploratory nature of the non-randomised controlled intervention was limited by the small number of participants, mostly of Latino origin, and low generalisability of the study findings. Significant results were found only for subgroups, not all participants. Despite efforts to emphasise a parental component, classes offered to parents of LA Sprouts participants were poorly attended. A later suitably powered, larger RCT study did report the programme to be effective(Reference Davis, Martinez and Spruijt-Metz41).

Two studies, both from Canada, investigated the effectiveness of introducing the EarthBox® water efficient, container gardening system into primary schools(Reference Hanbazaza, Triador and Ball18,Reference Triador, Farmer and Maximova20) in combination with a vegetable and fruit snack programme. These container gardens can be used to grow vegetables, herbs and berries in the classroom setting. An 18-month study conducted in a rural First Nations elementary school found that although preference scores for vegetables improved 7 months following inception of the intervention, these had decreased to near baseline levels by 18 months(Reference Triador, Farmer and Maximova20). Children did not increase their home consumption of any produce they were exposed to at school, but instead the results indicated that foods most liked and disliked by children were also those most often and least often consumed by children at home, respectively. Similarly, there was a decline in vegetable preference in another 2-year programme(Reference Hanbazaza, Triador and Ball18).

A lack of an intervention effect on vegetable preference or consumption patterns identified in many of the unsuccessful studies raises a question regarding the necessary dose of a school intervention, and the type of school intervention required to yield enduring change. These studies suggest that school interventions to improve children’s diet quality through gardening also need to focus on influencing the home and community food environments, and increasing vegetable preferences more than fruit preferences as the latter is more difficult to shift in young children.

Of the thirteen studies investigating food provision programmes, defined as food or meals provided to children on school grounds for consumption either at school or at home, five were deemed successful (three high quality and two low quality). These were interventions that included a 16-week take-home food distribution co-op(Reference Sharma, Markham and Chow50), a 21-week free FV snack programme(Reference He, Sangster Bouck and St Onge51), a 12-month school breakfast programme(Reference Murphy, Tapper and Lynch53), a 12-month free meal provision during the school day(Reference Kastorini, Lykou and Yannakoulia54) and a 2-year free provision of fruit or ready-to-eat vegetables (cherry tomatoes and baby carrots) twice a week during a classroom fruit break(Reference Tak, te Velde and Brug52). Food provision interventions were also frequently paired with relevant and comprehensive classroom nutrition education(Reference Sharma, Markham and Chow50–Reference Tak, te Velde and Brug52,Reference Kastorini, Lykou and Yannakoulia54) . The Brighter Bites programme was particularly successful in achieving increased intakes of FV consumption by sending home fresh food to families(Reference Sharma, Markham and Chow50), along with recipes, and involvement of parents in health education sessions. Programmes that provided snacks or meals on school grounds influenced change in dietary behaviours whilst at school(Reference He, Sangster Bouck and St Onge51–Reference Kastorini, Lykou and Yannakoulia54), but their effect on overall diet quality is unknown. Of the three unsuccessful studies of food provision, a high-quality RCT from New Zealand found that after providing free fruit daily for one term, fruit intakes fell below baseline levels at 6 weeks of follow-up(Reference Ashfield-Watt, Stewart and Scheffer29), indicating lack of sustained changes in dietary behaviours over time. In another RCT of moderate quality conducted in New Zealand, a free daily school breakfast programme decreased short-term hunger but did not impact on children’s overall school performance or attendance.(Reference Mhurchu, Gorton and Turley28)

Of eleven studies reporting on taste testing interventions, eight were found to be successful (three high and five low quality), with frequency varying between weekly(Reference Battjes-Fries, Haveman-Nies and Renes55,Reference Lakkakula, Wong and Zanovec57–Reference Morrill, Madden and Wengreen60,Reference Perry, Bishop and Taylor62) and monthly(Reference Day, Strange and McKay56,Reference Lachausse61) . Five of these interventions also included a classroom nutrition education component(Reference Battjes-Fries, Haveman-Nies and Renes55,Reference Day, Strange and McKay56,Reference Gold, Larson and Tucker59,Reference Lachausse61,Reference Perry, Bishop and Taylor62) . Of the studies that measured food consumption as an outcome,(Reference Gold, Larson and Tucker59–Reference Perry, Bishop and Taylor62) three reported significant improvements associated with exposure to foods through tasting. The Food Dudes programme(Reference Morrill, Madden and Wengreen60) provided prizes as incentives and incorporated targeted foods in the school cafeteria which improved student food choices. Studies found that repeated tastings were required to impact on liking for foods, especially for vegetables. A large study from the Netherlands (n 877) that included five tasting sessions failed to change willingness to taste unfamiliar vegetables and consumption of target foods(Reference Battjes-Fries, Haveman-Nies and Zeinstra31).

Ten(Reference Bisset, Daniel and Paquette63–Reference Bai, Kim and Han72) of the eleven studies on cooking lesson interventions resulted in successful outcomes for self-efficacy and confidence in cooking skills. Cooking programme duration varied between three lessons(Reference Caraher, Wu and Lloyd68), four lessons(Reference Chen, Goto and Wolff65,Reference Bai, Kim and Han72) , five lessons(Reference Liquori, Contento and Castle67,Reference Quinn and Castle70) , eight lessons(Reference Bisset, Daniel and Paquette63) and ten lessons(Reference Zahr and Sibeko64,Reference Jarpe-Ratner, Folkens and Sharma66,Reference Cunningham-Sabo and Lohse69,Reference Cunningham-Sabo and Lohse71) , with three also including classroom nutrition education(Reference Liquori, Contento and Castle67,Reference Cunningham-Sabo and Lohse69–Reference Bai, Kim and Han72) . Notably, the four studies that measured food consumption(Reference Chen, Goto and Wolff65,Reference Jarpe-Ratner, Folkens and Sharma66,Reference Caraher, Wu and Lloyd68,Reference Quinn and Castle70) reported improvements in dietary intake following participation in cooking classes. A single study deemed not to be successful was very low quality, conducted in only twenty-three students and provided only post-test data(Reference Brill and Shaykis37).

Ten(Reference Evans, Rutledge and Medina73–Reference Sahota, Christian and Day82) of the eleven multicomponent activities were successful. The Australian Vegetable Education Resource to Increase Children’s Acceptance and Liking (VERTICAL) programme combined elements such as exposure to vegetables as well as role modelling. In only five 1-h sessions, children’s willingness to try new vegetables significantly increased(Reference Poelman, Cochet-Broch and Cox81). Specialised education curricula designed to be accompanied with fun activities such as the ‘Top Grub’, card game(Reference Lakshman, Stephen and Forouhi75). Over 9 weeks, children from intervention schools in this RCT had higher mean nutrition knowledge scores and were more likely to be currently eating a healthy diet compared with those children in control schools. The edutainment factor was also shown to be effective in a single 1-h programme (Jump with Jill programme) that incorporated an active, participatory game, which applied learning through play approach. Themed or novelty approaches have been found to be effective in primary schoolchildren. The Healthy Highway© Program is an interactive, imaginative, content-based programme that teaches and reinforces essential health-related topics to K-5 students on healthy foods and basic nutrition with a road safety analogue. In a study that exended this theme to the school cafeteria, and coded food choices as ‘healthy (green light) or unhealthy (red light)’, healthy choices improved(Reference Jung, Huang and Eagan79). The UK PhunkyFoods Programme allowed schools to choose which elements of the programme they wanted to deliver as part of the school curriculum, and this flexibility was perceived by teachers to be a strong programme attribute(Reference Sahota, Christian and Day82). Activities could be offered within the classroom or as a club, e.g. breakfast, after-school or lunch club, and resources included a wide selection of online, interactive cross-curricular healthy eating lesson plans and a resource box comprising food models, food mats, food cards, DVD and books to facilitate teaching staff in programme delivery.

In summary, key components of experiential strategies that are useful to increase children’s vegetable and fruit intake, as well as help children to develop healthy eating habits include: improving the availability of FV at school, at home, and in the community; repeated taste testing opportunities for children; family involvement in activities that promote healthy eating at home; explaining to parents the importance of role modelling good nutrition and engaging children in hands-on activities with their peers such as growing and harvesting vegetables and fruit, and cooking.

Discussion

This systematic literature review qualitatively investigated the effects of experiential nutrition programmes on primary school-aged children in relation to cognitive and behavioural outcomes. It further identified key characteristics of successful programmes that achieved significant changes in the outcomes of interest and also provided a robust evaluation thereof. Such information is useful to guide future public health interventions in this setting. Characteristics of successful experiential nutrition interventions included: (1) frequent exposure that include multiple experiences, accompanied by relevant and comprehensive classroom nutrition education; (2) incorporation of parental involvement and take-home activities; (3) presentation in a context that was relevant and appropriate; (4) multicomponent interventions that are conducted on school grounds and (3) involvement of external personnel, such as expert educators, teacher training and volunteers. Involvement of food service providers to increase exposure, availability and accessibility of healthy food options was also beneficial, whilst adequate provision of funding and resources for implementation of the programmes is paramount. Successful interventions guided by a behavioural change theory tended to be the most impactful in terms of creating changes in both the school environment and children’s behaviours.

It has been established that experiential learning accompanied with cross-curricula interventions is most beneficial and effective at producing knowledge and behaviour change in young children(Reference Dudley, Cotton and Peralta84). In relation to the behavioural changes investigated in this review, garden-based learning strategies appeared to be the most influential strategies that related to dietary outcomes, particularly increased vegetable consumption(Reference Duncan, Eyre and Bryant42–Reference Ratcliffe, Rogers and Goldberg48), which has proven difficult to achieve with other interventions(Reference Evans, Cleghorn and Greenwood4,Reference Tak, te Velde and Brug52) . Gardening, unlike other experiential nutrition learning styles, has been intensively investigated in recent years(Reference Schneider, Pharr and Bungum85). Food gardens have gained recognition as not only do they teach children about growing their own foods, but evidence also suggests that when children are involved in the process of growing fruits and vegetables, they are more likely to taste and consume them(Reference Carlsson, Williams and Hayes-Conroy39,Reference Langellotto86) . Potential reasons for the success of the garden-based programmes may include: (1) increased accessibility to healthful foods; (2) increased exposure of children to the practice of growing foods, as these interventions are typically more time intense than others and (3) the broad range of experiences offered including planting, gardening and harvesting through to cooking and tasting opportunities. Garden-based interventions have also been shown to increase children’s willingness to try new foods and their ability to cook and prepare foods(Reference Block, Staiger and Gold87). The studies also significantly improved the ability of children to identify different FV, as well as other nutritional-related knowledge(Reference Davis, Martinez and Spruijt-Metz41–Reference Hutchinson, Christian and Evans49). Our findings are supportive of the recommendations of the Community Preventive Services Task Force, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention(Reference Savoie-Roskos, Wengreen and Durward88), that indicate that food garden interventions, in combination with nutrition education, are effective in increasing vegetable intake in youth.

Interestingly, of the cognitive-based outcomes investigated in this review, cooking-based activities tended to have the most significant changes on student self-efficacy through food preparation skills(Reference Zahr and Sibeko64,Reference Jarpe-Ratner, Folkens and Sharma66,Reference Caraher, Wu and Lloyd68,Reference Cunningham-Sabo and Lohse69) as well as improvements in their food knowledge and preferences(Reference Bisset, Daniel and Paquette63,Reference Chen, Goto and Wolff65–Reference Liquori, Contento and Castle67,Reference Cunningham-Sabo and Lohse69–Reference Cunningham-Sabo and Lohse71) . Cooking programmes offer children a unique hands-on experience that can provide lifelong skills(Reference Fordyce-Voorham89). These benefits are coherent with similar research on culinary interventions in other settings(Reference Hasan, Thompson and Almasri90,Reference Prescott, Lohse and Mitchell91) .

Food provision programmes have been associated with increasing the consumption of healthy foods and generating positive attitudes towards eating breakfast(Reference Bartfeld92). The studies included in this review found significant improvements in dietary intakes of healthy foods(Reference Murphy, Tapper and Lynch53) including FV(Reference Sharma, Markham and Chow50,Reference He, Sangster Bouck and St Onge51,Reference Kastorini, Lykou and Yannakoulia54) , wholegrains(Reference Sharma, Markham and Chow50,Reference Kastorini, Lykou and Yannakoulia54) , fibre(Reference Sharma, Markham and Chow50) and dairy foods(Reference Kastorini, Lykou and Yannakoulia54). All nutrition interventions that included tasting of FV increased overall short-term FV intakes, in addition to food knowledge and preferences. However, as with food provision interventions, results were difficult to demonstrate over the longer term because most studies did not include follow-up post-intervention. Studies which incorporated tasting activities impacted food knowledge through increasing students’ ability to correctly identify certain FV. Interestingly, successful studies identified that increased exposure may lead to more significant results, as reported by one study where it took eight to ten encounters before scholars reported that they ‘liked’ the particular food item(Reference Lakkakula, Zanovec and Pierce58). Food-related attitudes, choice and intake in children are largely driven by taste preferences. A review by Barends et al. (Reference Barends, Weenen and Warren93) reported that repeated exposure to vegetables in the first 3 years of life increased acceptance of the target vegetable, whereas exposure to variety was found to be particularly effective in increasing acceptance of a new vegetable. Studies included in the current review support this strategy in older children attending primary school.

Nutrition interventions aimed at improving healthy behaviours need to focus on changing the environment and societal norms(Reference Dobbs, Sawers and Thompson94). When developing nutrition programmes within primary school settings, interventions need to target the multiple facets of the environment. This requires consideration in providing as many experiences as possible in relation to skills development of growing, cooking and tasting foods. Through increasing exposure and accessibility to healthy foods, the more likely it will be to meaningfully impact health knowledge and behaviour. Some successful interventions, particularly food provision and tasting programmes, achieved this through incorporating a cafeteria component and involved food service providers(Reference Sharma, Markham and Chow50,Reference Morrill, Madden and Wengreen60–Reference Perry, Bishop and Taylor62,Reference Liquori, Contento and Castle67,Reference Evans, Rutledge and Medina73,Reference Prelip, Thai and Erausquin74) which assisted in increasing the exposure, availability and accessibility of healthier options.

Another frequently employed strategy used within experiential interventions was the inclusion of parental involvement and education. Parental involvement in school-based programmes can strengthen the home food environment and reiterate the healthy eating messages and habits being demonstrated at school. Involvement of parents, carers and family members has been identified as an important strategy in changing food-related behaviours in primary school-aged children(Reference Nixon, Moore and Douthwaite95), but there is limited information on how best to engage parents(Reference Hingle, O’Connor and Dave96). Studies in the current review which incorporated parental involvement included activities such as take-home produce and recipes to cook and share(Reference Duncan, Eyre and Bryant42,Reference Kararo, Kathryn and Neil43,Reference Leuven, Annerie and Leuven45,Reference Sharma, Markham and Chow50,Reference Lachausse61,Reference Perry, Bishop and Taylor62,Reference Zahr and Sibeko64–Reference Jarpe-Ratner, Folkens and Sharma66) , additional homework activities or challenges(Reference Gold, Larson and Tucker59), parent education sessions(Reference Sharma, Markham and Chow50,Reference Perry, Bishop and Taylor62,Reference Liquori, Contento and Castle67,Reference Quinn and Castle70,Reference Prelip, Thai and Erausquin74) or parental volunteering in programme supervision(Reference Murphy, Tapper and Lynch53,Reference Bisset, Daniel and Paquette63,Reference Liquori, Contento and Castle67) .

A common implementation strategy used by many of the studies included in this review was the use of external educators(Reference Davis, Martinez and Spruijt-Metz41,Reference Hutchinson, Christian and Evans49,Reference Murphy, Tapper and Lynch53,Reference Kastorini, Lykou and Yannakoulia54,Reference Gold, Larson and Tucker59,Reference Lachausse61,Reference Bisset, Daniel and Paquette63–Reference Chen, Goto and Wolff65,Reference Liquori, Contento and Castle67–Reference Cunningham-Sabo and Lohse71,Reference Evans, Rutledge and Medina73) (including nutritionists/dietitians, chefs, horticulturalists and university researchers/students) or in-depth teacher training(Reference Kararo, Kathryn and Neil43,Reference Lineberger and Zajicek44,Reference Ratcliffe, Rogers and Goldberg48,Reference Battjes-Fries, Haveman-Nies and Renes55,Reference Day, Strange and McKay56,Reference Liquori, Contento and Castle67,Reference Quinn and Castle70,Reference Prelip, Thai and Erausquin74) to assist in the effective delivery of the programmes. It has previously been demonstrated that intervention success is dependent upon a number of factors, with high levels of teacher self-efficacy and prior knowledge related to the intervention being among the most important(Reference Kien, Grillich and Nussbaumer-Streit97). While the use of external educators and experts is important for ensuring information accuracy and student engagement, this may not be feasible due to funding requirements. Similarly, longer-term interventions with a high degree of implementation are more effective at achieving knowledge and behaviour change of schoolchildren, but upscaling of programmes may not be practical(Reference Lehto, Määttä and Lehto98).

This review did not include programmes that were totally conducted off school grounds, such as farm visits(Reference Moss, Smith and Null99,Reference Bevan, Vitale and Wengreen100) because it was the aim of the review to identify successful programmes that could be run by all primary schools, regardless of proximity to food production sites, or urban/rural location. In the USA, farm visits are a primary mode of experiential school-based nutrition learning provided through the federally funded USDA Farm to School grant programme(101). There is high uptake of this programme(102), with participation rates of 42 % in some school districts and extensive evaluation thereof(Reference Yoder, Liebhart and McCarty76,Reference Joshi, Azuma and Feenstra103–Reference Kropp, Abarca-Orozco and Israel107) . The definition of USDA Farm to School programmes includes garden education, local procurement for school foods and experiential learning activities in agriculture, food, health or nutrition. Our search criteria did identify some programmes that included Harvest of the Month activities and farm visits, but only if they were included as a component of a larger programme, some of which was held on school grounds(Reference Hyland, Stacy and Adamson108–Reference Smith and Kalina114). Likewise, the review did not include programmes conducted out of school hours, many of which have been evaluated as being effective for behaviour change(Reference Cradock, Barrett and Giles115,Reference Annesi, Smith and Walsh116) .

The US nationwide Coordinated Approach to Child Health (CATCH) programme(117), first developed in the late 1980s and funded by the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute, was not included in the current review because it is paired with a physical activity component, and thus did not meet the eligibility criteria. CATCH has been proven to prevent childhood obesity and is supported by 25 years of operation, with 120 academic papers indicating as much as 11 % decrease in overweight and obesity(Reference Luepker, Perry and McKinlay118–Reference Hoelscher, Springer and Ranjit122). CATCH creates behaviour change by enabling children to identify healthy foods and by increasing the amount of moderate to vigorous physical activity children engage in each day. Today, CATCH serves children in 10 000 schools and communities across the USA, from pre-K to Grade 8, as well as in after-school settings.

The main limitation that needs to be considered in the interpretation of the findings of this review is the generally low quality of the cited studies. The studies varied extensively in quality; with only eleven of the forty-two cited studies analysed in the review receiving a high-quality GRADE rating, all of which were RCT. School-based programmes are often very challenging to randomise, and it is often not ethically appropriate to do so(Reference Eccles, Grimshaw and Campbell123).

The short study duration of many included programmes is an additional limitation. Battjes-Fries(Reference Battjes-Fries, Haveman-Nies and van Dongen124) suggests that interventions should last at least 1 year in order to result in meaningful behaviour change. The food provision programmes and food tasting studies all had large sample sizes; however, most of the gardening and cooking studies had smaller sample sizes due to the intensive nature of the interventions. The interventions also lacked continued follow-up to evaluate longer-term results.

Another limitation is the variety of different instruments used to measure outcomes, making comparison between the cited studies difficult. Food provision intervention groups were commonly measured using the validated eighteen-item food security scale(Reference Gulliford, Nunes and Rocke125), while dietary behaviour change was generally assessed using 24-h-recalls or FFQ. Food tasting programmes largely used non-validated research instruments, which were most often designed by those running the intervention, possibly resulting in misclassification or other biases. A lack of studies from low- and middle-income countries limits generalisability to these settings. Lastly, identification of key characterstics of the interventions deemed to be successful was subjective in nature; therefore, observer bias cannot be ruled out.

Despite these limitations, this review highlights the benefits of experiential interventions and provides direction for future programmes. Vegetable intake was found to be the most difficult of dietary behaviours to change but, collectively, the cited articles suggested that experiential hands-on activities such as gardening, cooking sessions and nutrition education combined with increased exposure to tasting vegetables were the most effective strategies.

A number of key recommendations have resulted from the findings of this review:

-

Use behavioural change theory to guide interventions, as these are most impactful in terms of creating changes in both the environment and children’s behaviours;

-

Link experiential learning opportunities to specific curriculum topics and integrate with classroom-based learning, rather being provided in isolation;

-

Include a focus on influencing the home and community food environment as well as providing exposure to experiential learning opportunities during school hours;

-

Incorporate family involvement and take-home activities to encourage healthy eating at home and provide role modelling of good nutrition practices;

-

Involve food service providers at schools to increase exposure, availability and accessibility of healthy food options;

-

When developing a school garden programme, ensure long-term commitment of at least 3 years, to allow sufficient time to impart skills, mentor across multiple growing seasons and to adequately integrate the garden into the culture of the school;

-

Ensure adequate resources are available for maintenance of food gardens, including weeding, watering and harvesting, particularly during school holidays;

-

Provide repeated opportunities to taste foods to encourage acceptability by children, especially for vegetables;

-

Where possible, include cooking-based activities as these are the most effective interventions that impact student self-efficacy, as well as improve their food knowledge and preferences;

-

Engage specialist staff, trained in horticulture and cooking to deliver interventions rather than expect classroom teachers to add gardening or food preparation to their skillset.

Conclusion

This systematic literature review has identified that experiential nutrition programmes are able to improve primary schoolchildren’s nutrition knowledge, attitudes, self-efficacy and dietary behaviours. Experiential interventions which included multiple experiences and exposures were able to show increases in children’s willingness to taste unfamiliar foods, their cooking and food preparation skills, as well as increased preference, knowledge and consumption of healthier foods. Vegetable intake appeared to be the most difficult behaviour to change but was most successfully addressed with food gardening approaches. Key characteristics of successful interventions were identified as parental involvement and take-home activities, sessions taught by external experts, as well as incorporation of food service providers to increase exposure, availability and accessibility of healthy foods within the school environment. Longer-term interventions are required to investigate sustainable behaviour change in improving dietary intakes in primary schoolchildren. Feasibility of larger scale programme dissemination and teacher training is also a worthwhile investigation for future research.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: Ezinne Igwe is thanked for her editorial assistance. Financial support: No funding was obtained for this work. Conflict of interest: There are no conflicts of interest. Authorship: K.C. and K.W. conceptualised the research proposal. N.D. conducted the preliminary search and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. T.C. repeated and updated the search, conducted quality rating and contributed to drafting of the final manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. Ethics of human subject participation: This study was a review of published studies and therefore did not require approval by an ethics committee.

Supplementary material

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980020004024