Introduction

I grieve somewhat the loss of life as we previously knew it. When my friend's husband died I grieved not being able to practice the rituals that have always helped – being with my friend, attending the funeral in person, surrounding her with love and support by being with her. (Bernadette, 68 yearsFootnote 1)

There have been few times in the history of the United States of America (USA) where bereavement and grief have been present in so many people's lives simultaneously (Goveas and Shear, Reference Goveas and Shear2020: 1119). It is estimated that for every COVID-19 death, nine individuals will be left bereaved (Verdery, Reference Verdery, Smith-Greenaway, Margolis and Daw2020). At the time of writing, the USA has surpassed 770,000 deaths due to COVID-19 (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2021). As cumulative mortality continues to rise, we risk losing sight that each death is a unique individual and tragic loss for their families (Walsh, Reference Walsh2020).

The COVID-19 pandemic has dramatically and disproportionately affected older adults through their greater risk of severe illness and death, as well as social distancing measures that may exacerbate distress (Ishikawa, Reference Ishikawa2020), isolation and loneliness (Tyrrell and Williams, Reference Tyrrell and Williams2020). Even prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, older adults were at greater risk for loneliness given shrinking social networks, isolating living situations (e.g. living alone or in residential long-term care) and mobility limitations (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine, 2020). The loss of meaningful contact with friends and family is associated with declines in mental and physical health (Tyrrell and Williams, Reference Tyrrell and Williams2020). Older adults face additional challenges during the pandemic such as overtaxed health-care systems and widespread ageism that labels older adults as burdensome and disposable in the context of COVID-19 (Monahan et al., Reference Monahan, Macdonald, Lytle, Apriceno and Levy2020; Finlay et al., Reference Finlay, Kler, O'Shea, Eastman, Vinson and Kobayashi2021). With the economic recession, older adults may have lost jobs or been forced into earlier retirement (Monahan et al., Reference Monahan, Macdonald, Lytle, Apriceno and Levy2020). The savings they once had in retirement accounts might no longer be available to sustain their livelihoods (Morrow-Howell et al., Reference Morrow-Howell, Galucia and Swinford2020).

Older adults are grieving multifaceted and complex losses through their shattered assumptive worlds because of the COVID-19 pandemic (Richardson et al., Reference Richardson, Ratcliffe, Millar and Byrne2021). Individuals form personal lenses through which we see the world and others, how we expect the world to work and how we see ourselves (Harris, Reference Harris2020a). These elements make up our individual assumptive worlds and enable us to feel safe and view the world as consistent and predictable in the face of bereavement (Parkes, Reference Parkes1971, Reference Parkes1988). Janoff-Bulman (Reference Janoff-Bulman1989, Reference Janoff-Bulman1992) expanded on this concept to describe three assumptive worldviews that might be challenged through bereavement or other traumatic experiences. These include the benevolence of the world – the extent to which an individual sees the world as positive or negative; meaningfulness of the world – an individual's perceptions of good and bad outcomes related to controllability and fairness; and worthiness of self – self-perceptions of one's goodness and fortune. These schemas reflect what an individual assumes to be true about themselves and the world, and serve the individual to feel grounded, secure and safe (Harris, Reference Harris and Harris2020b). The multitude of losses due to the COVID-19 pandemic have assaulted our assumptive worlds and left many individuals feeling vulnerable and unsafe.

Given the complex nature of grief and widespread losses associated with the pandemic, it is paramount to better understand the specific types of losses that individuals and families are facing. Older adults may face unique experiences of grief due to the escalating numbers of deaths among their age cohort (Powell et al., Reference Powell, Bellin and Ehrlich2020), social isolation (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine, 2020), and very real ongoing losses due to age and decline (Ishikawa, Reference Ishikawa2020). It is vital that researchers consider the nature of all losses, not just those related to death and bereavement, as experiencing grief throughout the pandemic is both global and highly personal. Grief is conceptualised as the highly personalised, individual response to loss, perceived and defined by the individual, and not limited to bereavement (Harris, Reference Harris and Harris2020b). The tendency to view grief and loss only in terms of death limits understanding and support, ultimately disenfranchising losses, especially among older adults, where certain losses, especially non-death losses, are not acknowledged, seen as valued or supported (Doka, Reference Doka and Harris2020). Further, experiences of loss can be tangible (physically evident, readily apparent) such as the loss of a job or relationship; or intangible (invisible, not obvious) such as loss of a sense of control, or loss of faith or hope (Harris, Reference Harris and Harris2020d). Additionally, many of the losses experienced throughout the pandemic can be conceptualised as non-finite, where there is an ongoing, indefinite experience of the loss (Harris, Reference Harris and Harris2020c). This study aims to fill an evidence gap on the specific sources of sadness, grief and loss experienced by older adults during the pandemic. Over 2,000 US adults aged ⩾55 years shared personal narratives about grappling with grief and loss as part of the nationwide COVID-19 Coping Study in 2020. Our results demonstrate wide-ranging losses that extend beyond death and bereavement. Findings may inform family and community supports and services to address complex subjective experiences of loss among older adults since the onset of the pandemic.

Methods

COVID-19 Coping Study

The COVID-19 Coping Study is a longitudinal, mixed-methods study of adults aged ⩾55 residing in the USA (Kobayashi et al., Reference Kobayashi, O'Shea, Kler, Nishimura, Palavicino-Maggio, Eastman, Vinson and Finlay2021). It aims to investigate how social, behavioural and economic impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic affect the mental health and wellbeing of older adults. A total of 6,938 participants were recruited from 2 April to 31 May 2020 using a multi-frame online recruitment strategy. Participants completed a 20-minute online questionnaire at recruitment, followed by brief monthly follow-up questionnaires. Full details of the study design and methodology are available elsewhere (Kobayashi et al., Reference Kobayashi, O'Shea, Kler, Nishimura, Palavicino-Maggio, Eastman, Vinson and Finlay2021; Finlay et al., Reference Finlay, Meltzer, Cannon and Kobayashi2021). For the present study, we analysed participants’ open-ended responses in the one-month follow-up questionnaire, administered between 1 May and 5 July 2020. The University of Michigan Health Sciences and Behavioral Sciences Institutional Review Board approved the protocol, and all participants provided written informed consent.

Analysis

We analysed responses to the open-ended question:

• As the COVID-19 pandemic continues, is there anything that you are grieving, mourning the loss of, or sad about? This may be concrete things, such as losing a loved one, job, community/family role, or daily routine; or more ambiguous, such as losing a sense of control, stillness at home, or belief that we can protect our family members. Please describe below.

Most participants provided lengthy responses narrating their intimate perspectives and experiences. The data were rich and highly varying and enabled novel insights into the complex and often-interconnected losses and distresses amid the COVID-19 pandemic. All responses were organised in the software package NVivo (version 12).

We thematically analysed the data using Braun and Clarke's (Reference Braun and Clarke2006) six steps of thematic analysis: (a) familiarisation; (b) generation of initial codes; (c) search for themes; (d) review themes; (e) define and name themes; and (f) write up themes. All authors read the data to familiarise themselves and gain a sense of the whole. This process supported immersion in the data to enable new insights to emerge and to inductively develop categories without imposing preconceived categories (Elo and Kyngas, Reference Elo and Kyngas2008; Finlay et al., Reference Finlay, Meltzer, Cannon and Kobayashi2021). After generating initial codes, authors TLS and JMF compared interpretations and points of divergence to refine and clarify codes. We independently coded a sample of responses to check for consistency in the meaning and application of the codebook, and to illuminate any differing interpretations due to individual bias. After finalising the codebook, TLS and JMF each coded half the data. We reviewed each other's coding to ensure completeness and accuracy, and to add any additional coding. Peer debriefing, referential adequacy, negative case analysis, member checks and clear audit trails enhanced transparency and credibility (Marshall and Rossmann, Reference Marshall and Rossmann2016). Iterative analyses continually seeking interpretation, alternative understandings and linkages led to saturation, whereby the themes were well-described by and fitting with the data (Dey, Reference Dey1999).

Results

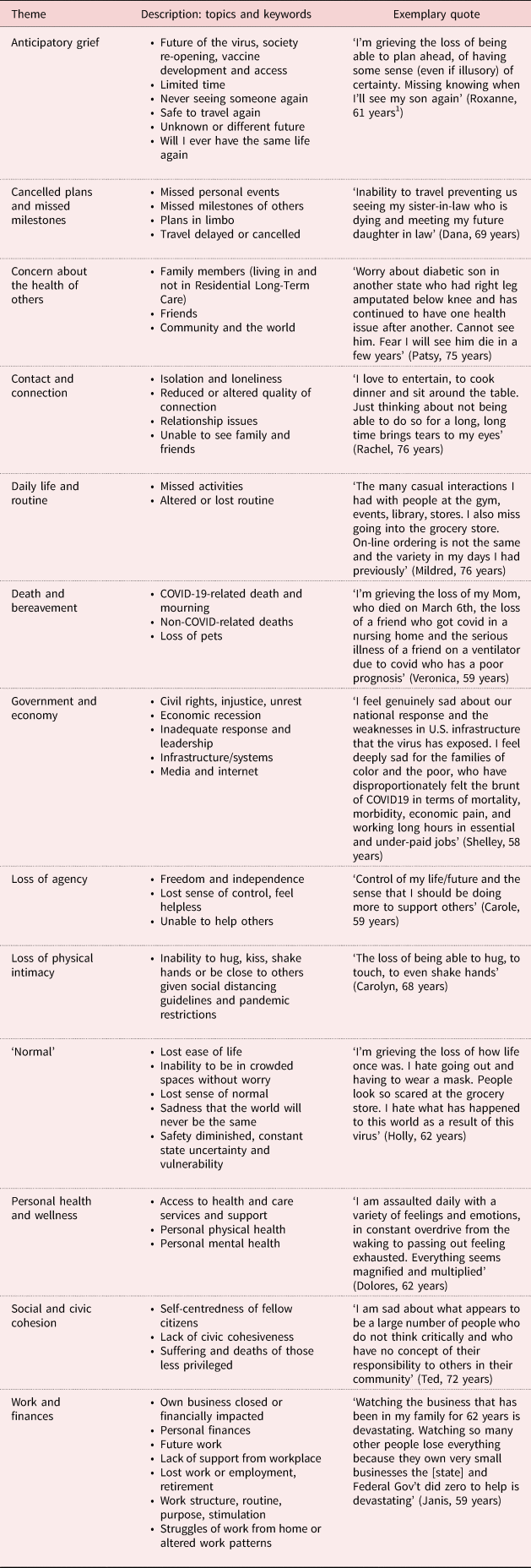

Of the 2,587 participants who completed the one-month follow-up questionnaire in the COVID-19 Coping Study, 2,201 (85.1%) wrote a response to the open-ended grief and loss question (Table 1). These respondents were over two-thirds female, on average 67 years old (standard deviation = 7.2), and largely white (94.4%). Over 80 per cent had at least some college education, two-thirds were married or in a relationship, over one-quarter lived alone and over half were retired (Table 1). The analysis generated 13 overarching themes that highlight the multifaceted and complex nature of grief and loss during early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic (Table 2). Below, we describe each theme in depth.

Table 1. Characteristics of the sample, COVID-19 Coping Study, May to July 2020

Notes: N = 2,201. SD: standard deviation.

Table 2. Qualitative thematic framework regarding sources of grief, sadness and loss, COVID-19 Coping Study, May to July 2020

Note: 1. Age reported at the time of data collection.

Anticipatory grief

Many participant responses were related to fear or dread of a possible future loss. Concerns included one's own mortality and limited time, future losses in one's community and the possibility that life will never be the same.

Participants indicated a sense of having limited time left, particularly those who were older. ‘I realize that as an older person (74) there are things I should not resume. I am aware that I don't have many years left, and this is robbing me of time’, shared Barbara. ‘At my age, valuable time is running out’, wrote Debra (76 years). Karen (88 years) grieved ‘missing out on what life I have left’. This led to an uncertainty about what to do at the present time, as Nancy (73 years) reflected: ‘Losing contact with family, not knowing how to live today, if I am going to die soon.’ For others, sadness was directed to older family members: ‘Squandering precious time with parents that are 87 and 94 years old that previously I would stop in to see every day’ (Donna, 66 years). Cynthia (55 years) articulated:

I'm afraid I will never see my parents again. [My parents] are in their 80s. We talk on the phone but it's not the same. I want to hug them. Like so many things, we don't know what we have until we don't.

Many participants commented on the uncertain future and long-term implications for future generations. Sherri (55 years) reflected feeling sad, given ‘the sometimes-overwhelming uncertainty about the future – how it will affect my job, how it will impact my community, how it will impact the economy’. Sandra (61 years) shared feeling ‘sad about the lasting changes in the world. Worried about the world for my children and changes in the opportunities they will have’. Participants indicated a sense of shattered dreams for their family's future dreams and plans.

There was also an indication of loss of one's way of life, shattered assumptions and non-finite losses that ‘life will never really be the same again’ (Pamela, 61 years). Sharon (79 years) articulated: ‘My grief, mainly, I think is for a lost way of life. I think I will never have the kind of life I had before this.’ A few participants, such as Thomas (77 years), expressed optimism about this altered future:

My wife passed 6 months ago and I still grieve for her somewhat. I moved to a different state to be closer to my daughter. And my life after C-19 [COVID-19] will never be the same, and I love that!

Cancelled plans and missed milestones

From routine events to celebrations, there was a strong theme of missed events and meaningful milestones. For some participants, the loss centred around the inability to celebrate personal milestones, such as birthdays, retirement or meeting a new grandchild for the first time. Pat (66 years) explained, ‘I just now retired from my job and am grieving the fact that I was not able to celebrate the end of my career in the way I had expected.’ Many participants expressed a lack of agency in being able to make plans and celebrate milestones with family and friends. The emotional impacts of this lost time and connection with family and friends were highly emphasised.

A parent commented on the experience for her high school senior: ‘My heart breaks for him and for me, as well as my 82-year-old mother who is missing these milestones too’ (Carol, 59 years). Many of the concerns about missed milestones of others were related to adult children's cancelled weddings, and the tenuous nature of when and how things might be celebrated in the future. Diane (64 years) explained feeling ‘sad for kids who are young adults planning for marriage and the future in what should be an exciting time’.

Participants expressed grief that the events they had been looking forward to were now in limbo, such as plans to move into a new home or to visit relatives. Many participants spoke of grief and concern about delaying or cancelling travel plans. Mark (66 years) was ‘saddened to cancel our trip of a lifetime to celebrate our 50th anniversary in Italy with our family together’. Brenda (67 years) was stuck:

I am 2000 miles from home and can't return there yet; I lost my mother earlier this year and wanted to go back to her home in New York City before it was sold but can't travel there; worried about friends and family in New York and there's nothing I can do for them if they get sick.

The cancellation or delay of travel related to a previous theme of having limited time left. Janet reflected on her situation: ‘[I] delayed travel for pleasure and seeing kids/grandkids. I'm 70 and don't feel I have that many more years to take road trips and travel to places on my bucket list.’ Elizabeth (69 years) explained, ‘It's depressing to finally be retired, have enough money to enjoy retirement, and not have the many things we do be available to do or wise to do.’

Concern about the health of others

Many participants articulated worries about the health of others in their lives, including ageing friends and family members. Ruth (67 years) was concerned about the outcome if her husband were infected: ‘I fear that my husband who has several health conditions will get Covid-19, he will not be able to fight it.’ Some mentioned having friends or family (e.g. mother, father, nephew) going through a COVID-19 infection. Maria (83 years) explained her situation with her husband living with dementia: ‘I am worried about my husband health. If he goes into hospital he cannot understand why I don't come to him. Thinking of this makes me cry.’ Many participants spoke of sadness given that family members were experiencing distress due to divorce, death and bereavement, layoffs, financial problems, mental health issues, worsening dementia, domestic violence, alcoholism and difficult decisions over reopening family businesses.

Participants mourned being unable to support family and friends, ranging from the inability to visit recovering family and friends, or managing hospice care virtually. Charlotte (72 years) wrote, ‘I am sad that I cannot visit my sister who lives about 6 hours away and is losing her battle against cancer.’ The inability to travel inhibited participants from supporting family through illness and death: ‘My brother-in-law in Canada is in hospice and not expected to make it this week … so I can't go there to help comfort my sister’ (Lois, 68 years). Eileen (70 years) explained:

My close friend of 50 years is hospitalized with Covid. It has been touch and go, with intubations, surgery, and [intensive care unit] stay of 34 days. I wish I could reach out to her, because she has been alone through all of this.

Family living in residential long-term care (RLTC) raised specific worries. Stephanie (68 years) had both parents living in RLTC at the time and was concerned: ‘My elderly parents cannot see each other and are locked down.’ Glenda (69 years) reflected, ‘I'm grieving the ambiguous loss of my husband whose dementia has worsened recently, and I'm very sad I can't visit him, like I used to daily, in the memory care facility where he lives.’ Yvonne (58 years) shared: ‘I also worry about a family member who lives in a nursing home that we are unable to advocate for.’ The impact on older adults, especially those living in RLTC, was of concern to Dianne (68 years). She explained her sadness over ‘the extreme isolation of people in senior living facilities; not allowed to visit family members; terrible death rates in senior living facilities; extremely poor handling of coronavirus outbreaks in facilities’.

Some individuals’ family members were able to receive health-care treatments but felt concerned about a higher risk of infection, as voiced by Rhonda (62 years):

My husband was diagnosed with a rare cancer on March 13. This has been a challenging time at any time but more so in a pandemic. We are now past surgery and recovery and have begun chemo treatments and while we feel safe going in and out of the hospital, we don't love that it is with extra risk of COVID-19 on an immune-compromised person.

Participants who were care-giving for ageing parents faced the inability to visit and their parent's declining physical or cognitive health. Roberta (65 years) reflected on her situation: ‘Worried about seeing my 91 old parents. I haven't seen them in 3 mo[nth]s. I worry that something will happen to them before I see them again.’ Helen (63 years) explained, ‘My father died after a long painful illness and I was a primary caretaker for over a year. Currently my mother is very ill and I am her only caretaker.’ Jeanne (58 years) wondered what the future of her care-giving and home situation might be:

Still struggling with being the caregiver for my 96-year-old father who we brought out of senior independent living to stay with us during the pandemic. It has been a lot at times and hard without the support of my other siblings. I worry that this will become a permanent situation due to the impact of the crisis on senior citizens and their risk of getting the virus.

Having friends or family working on the frontline was an area of concern. For Rita (60 years): ‘With two family members in the health care field, I am worried about them going to work every day and possibly being exposed to or getting COVID.’ For Kevin (73 years) this concern was tremendous, ‘[I have] 10 family members [who] are on the front line.’

Concerns about their responsibility for the health of others was highlighted, as Phyllis (78 years) questioned, ‘Am I doing enough to protect myself and others?’ There was concern about exposing others to the virus. Arnold (58 years) explained,

Lack of control – taking care of elderly parents when I can't get to them without risking being exposed. Watching my spouse fret over inability to get to her mom to help her through surgery, without a 14 day [quarantine] after travel.

For Grace (58 years), the message came from others, and they voiced frustration, ‘I've heard one too many times that I might be sick and not know it and kill my parents.’

Contact and connection

Many participants grieved the loss of contact with friends, family and even strangers. For Charles (67 years), ‘I always lead with a smile. It tends to make others smile back and, perhaps, feel a little happier. That doesn't happen when one is wearing a face mask.’ Similarly, Steven (75 years) explained missing ‘being in public places with other people, interacting or just people watching’.

Participants often indicated feeling isolated and lonely. Gary (64 years) shared, ‘I miss not seeing co-workers, I miss personal interaction. I miss not going into society.’ For Joseph (56 years), being apart from others meant vital support was missing: ‘My wife had a stroke in the past so limited support for her or me now.’ Kathy (72 years) explained: ‘I live alone. I am being careful, but it is hard to totally stay at home. I feel isolated.’ For Donald (66 years), this sense of isolation only grew given ‘loss of social life, I felt socially isolated before COVID-19 now I am even more isolated’. Several participants spoke of losing a spouse, some years earlier and some more recently, as cause of isolation. For Margaret (71 years):

I recently lost my husband and was just beginning to adapt to living alone and figuring out what I was going to do with the rest of my life. Now I feel totally alone, isolated from friends and not in a position to do anything to help anyone.

Some participants grieved a loss of community. Ronald (61 years) shared: ‘This is kind of trivial; but we just moved to an over 55 active adult community, and all of the activities we were looking forward to are stopped. This also limiting our ability to make new friends.’

Relationship issues due to increased time at home together, loss of relationships, and concerns about the quality and depth of relationships following the pandemic were voiced. For Joyce (62 years), the challenge was ‘trying to navigate marriage during COVID-19 [when we are] both home 24/7’. Paul (58 years) described a similar concern: ‘Strained family relations from too much together time.’ Teresa (61 years) articulated ‘I miss my time alone, my privacy. We are getting on each other's nerves.’ Though Doreen (70 years) had a partner at home with her, there was still a sense of isolation: ‘There are days when my husband is pretty grumpy and I feel more alone with my feelings.’

Some participants experienced a divorce immediately prior to or during the pandemic. Catherine (66 years) described: ‘My marriage and family broke up after I had the virus. I have been dealing with the post-Covid19 syndrome. My family has abandoned me. They were angry that I was so ill.’ For Larry (69 years): ‘I was divorced, which I did not wish for, two months before the pandemic broke.’

Decisions around safety and isolation were reported by participants to be challenging in their friendships. Shirley (76 years) explained: ‘Feel those in my friends group are withdrawing from friendship in their fear and isolation.’ In contrast, Judith (73 years) expressed: ‘A lot of family members and friends are saying that I am overreacting and I'm paranoid because I want to isolate. This causes a lot of anxiety and self-doubt.’ Similarly, Betty (67 years) described concern about how isolation might affect her friendships: ‘I remain sad and trepidatious about the potential long-term impact upon my relationships with friends who do not have the same standard of self-distancing that I do. I'm afraid to re-join them.’

The views and opinions of friends and family caused much stress for participants. Beverly (58 years) explained:

Discomfort with the extreme views of some (friends, family, acquaintances mixed) in their response to quarantine restrictions (refusal to comply, or comply but rail against the need at every chance; espousing extreme views without factual back up to their arguments).

Lisa (61 years) described a similar experience with family: ‘Sad about an aunt figure who is dying from COVID-19 and angry about an In-law who is sending (proven!) false information to justify her own noncompliance with social distancing.’

Daily life and routine

Participants lamented the loss of stimulating activities and social connection given the closure of sites for community, entertainment, leisure and retail. Laura (66 years) shared her sadness: ‘Because everything is closed, library, retail stores, community [recreation] center with pool, my outlets are gone. Nothing to do or enjoy outside of the home.’ Participants shared the ‘loss of things that make life’ (Daniel, 67), including frequenting arts and cultural sites (e.g. theatre, opera, gallery, museum, live music); cafes, restaurants and bars; gyms, swimming pools and professional sporting venues; sites to volunteer; stores (e.g. grocery, hardware); hairstylists and nail salons; and community events and gathering places such as senior centres or fairs. Some participants shared that they missed attending worship in-person, singing in the choir, volunteering, and socialising with friends and family in their faith communities. Many missed the camaraderie of daily activities (e.g. planned or spontaneous contact with others while exercising, shopping, eating) and sense of community. Some participants keenly felt the loss of support groups, such as for substance abuse and for cancer. Participants widely expressed frustration and sadness to be ‘trapped’ at home without a schedule or regular opportunities for physical, social and mental wellbeing. Theresa (72 years) noted: ‘the structure of my life is gone’, while Stephen (72 years) shared his grief over the ‘loss of community, routine that kept me connected’.

Death and bereavement

Participants reflected on friends, family and community members lost to COVID-19, ranging from spouses, parents and extended family members to strangers. Close losses made the pandemic more ‘real’ to many, as Connie (60 years) explained: ‘[My] elderly cousin died away from family in [a] long term care facility. Becomes very real when you know someone who died from it.’ Ann (63 years) shared, ‘My sister died in April from the virus. I hadn't seen her in years and didn't get a chance to see her before she died.’ Watching others in their cohort die from COVID-19 led some participants to feel distressed. Gloria (73 years) wrote, ‘[I] have a lot of “survivor guilt” in hearing of deaths in my age group or younger adults with families.’ Some participants expressed grief for the deaths of others they had never met. Julie (68 years) indicated, ‘[I am] grieving for all the needless death from COVID-19 and from racism’, and Gail (79 years) said ‘Memorial Day has reminded me of the many vets [veterans] who made it through horrible wars and are now dying of COVID-19, and that makes me sad.’

Death and bereavement experiences prior to COVID-19, such as losing a spouse in the months or years prior, was particularly hard to cope with during a lonely and solitary time. Timothy (84 years) reflected, ‘My dear wife (of 61 years) died 16 months ago, and I miss her greatly.’ Two widows shared their experiences of being alone during the pandemic: ‘I miss my husband who died at the end of 2018. It would be easier not to be all alone’ (Joan, 59); ‘I am a recent widow, living alone for the first time in a new place. I was a mess before the pandemic. Being alone is terrible, but being unable to touch anyone is literately testing my sanity’ (Paula, 60). Edward (81 years) explained his situation: ‘My wife died 8 months [ago], grieving and isolation at the same makes life difficult.’

Losses were complex and highly personal. Peggy (63 years) explained, ‘I am permanently sad due to the loss of my only child 8 years ago. That will never change; COVID-19 means nothing to me.’ Cindy (65 years) shared, ‘[I am] grieving the death of my daughter (my only child) and personality changes in my husband.’ Many participants spoke of losing longtime friends by a variety of causes including suicide and dementia: ‘Many of my friends have died this year … not from the virus. I am the last person alive in my family’ (Martha, 85). Grief could be amplified by the pandemic:

A very close friend died unexpectedly in January 2019. This pandemic has increased my sense of loss again as he was someone I talked to daily as my sounding board. I miss him terribly and this has contributed to my increased sadness. (Bonnie, 68 years)

Some participants tried to find solace as their deceased loved ones did not have to experience the pandemic. Jane (69 years) reflected: ‘Missing my parents, who are deceased, quite a bit although I am glad they are not having to go through this.’ Cathy (72 years) similarly shared:

My husband died 8 months ago. He would have been extremely high risk for this so I am glad he didn't have to die alone in a hospital from COVID-19. I have been actively working through the ‘grief journey’ as it is called. I miss him. We were married 53 years. So this pandemic doesn't scare me. I've already survived the worst event with his death.

A few participants were awaiting an impending death. Robin (59 years) said, ‘My boyfriend is dying, I will be homeless when that occurs.’ Debbie (71 years) explained, ‘My cousin in [Colorado] is in [a] nursing facility with dementia and dying alone.’ Dying during the pandemic, even from non-COVID-19 causes, was an added challenge. Diana (58 years) explained, ‘Father-in-law is dying on hospice – difficult to navigate in current situation.’

For others, deaths in recent years had accumulated. Jeffrey (61 years) reflected, ‘[I've] lost over 15 close friends and family members, no funeral or support for Their Families [sic].’ Marilyn (60 years) counted her recent losses: ‘Have lost my husband, 2 brothers, 2 nieces, a daughter in law and 3 longtime pets within the last 5 years.’ Multiple participants spoke of the loss of pets, particularly dogs. As Kathryn (57 years) explained, this experience of grief impacted their entire family, ‘I lost my dog which has caused the house serious grief.’ The protocols for the pandemic added challenges to the experience of pet loss during this time as well. Dorothy (58 years) shared her experience: ‘loss of pet, said goodbye outside clinic due to COVID.’

Government and economy

Participants grieved broader structural losses of the American political system, the economic recession, and socio-economic disparities and health inequities that the pandemic exposed and exacerbated. Dave (72 years) articulated, ‘I am sad and angry that the incompetency of the White House has caused our country to become weaker, sicker, and poorer.’ Participants expressed feeling upset after the killing of George Floyd, systemic racism, police brutality, rise of disinformation, and the loss of democracy and civil rights in the USA. Wanda (70 years) expressed ‘grieving the loss of our democracy and life as we have known it. Grieving the greed and avarice of the president and people in power with him.’ Participants voiced anger over the federal government's handling of the pandemic and immense sadness over the resulting loss of death. Participants grieved ‘the people who have died needlessly because of Trump and the [Republican Party]’ (Jean, 64). They felt that political partisanship and divisiveness was literally costing lives.

A minority of participants expressed divergent political views, grieving the loss of civil liberties given shutdowns they felt were unnecessary. George (78 years) felt ‘sad that “experts” have been allowed to hijack our responses to the Chinese virus; their view is much too narrow to permit them to call the shots for our entire society’. Gregory (59 years) expressed: ‘I am sad about society's overreaction to the pandemic and the harm this has done to our economy.’

Participants with wide-ranging political views uniformly expressed sadness and loss over the economy. Vicki (59 years) mourned ‘the permanent closing of long-time family-owned restaurants and shops in my town’. Participants expressed sadness for the closure of small businesses, loss of employment, and dim economic prospects for the USA and global economy. Sheila (64 years) expressed:

I have great fear for the future of our economy and the members of our community who face financial difficulties, now and into the future. I don't think things will ever go back to the way they were.

Participants mourned the loss of democracy and national pride. Virginia (79 years) wrote:

Very depressed about our broken country. I used to be proud of the USA in spite of some mistakes we have made. Now my grandchildren will have to live in this cruel chaos. I am sad for all of us.

For Sherry (60 years):

Grieving the loss of kindness and empathy in our country. Mourning the country embracing hatred and ignorance above compassion. My husband and I are seriously talking about moving out of this country when this is all over. I do not want to live in the country the US has become.

Katherine (69 years) shared feeling

very sad today because my beautiful country is on fire … Destroying our democracy is the most frightening thing I've had to live through. I am a child of the [19]60s, I have marched in many a protest, none like this … Today I am heartbroken.

Loss of agency

Participants indicated a lost sense of control and feelings of helplessness. For James (57 years), this loss was broad: ‘Losing the illusion of control and predictability of life.’ Mary (78 years) shared grieving her ‘impotence – not being in control of my life, activities, family’. Participants shared lost confidence in being able to ‘control the course of events’ (Michael, 66 years), and feeling ‘a sense of helplessness that you can become a virus victim without warning’ (Robert, 88 years). Others expressed sadness about being unable to assist their friends, family or community. John (77 years) shared ‘losing sense of being able to protect those around me’, while David (58 years) wrote: ‘I feel sad about not being able to protect my family.’ Linda (81 years) shared sadness ‘having given up my [Registered Nurse] license years ago, being unable to help’.

Participants spoke of grieving the loss of freedom of movement in their lives and used varying terms including ‘liberty’, ‘independence’ and ‘choice’. For a few participants, this loss was tied to state or local restrictions in place to address the pandemic. Patricia (64 years) stated: ‘I am grieving the loss of my liberty. I live in a State where its Governor makes pronouncements that he believes he can enforce. The Constitution provides my right and my freedom. I intend on taking it.’ Susan (63 years) expressed ‘feeling like our government is trying to rule my life’. For select individuals this loss of freedom was tied to the requirement to wear masks: ‘[my] husband is mourning loss of individual rights, having to wear face masks’ (Deborah, 69 years).

Loss of physical intimacy

For many participants, the unprecedented and unique loss of physical touch during the pandemic greatly impacted their overall sense of loss. Kenneth (58 years) shared: ‘Daughter recently miscarried and we are not able to care, comfort, [and] hug her.’ Loss of face-to-face contact was reported by many participants. Janice (63 years) reflected, ‘I miss having physical contact with other human beings. It's been many weeks since I touched another person – no hugs, not even a hand on a shoulder. Seeing my daughters on a screen is not the same.’ For Denise (70 years), this loss of physical touch was visceral: ‘I have twelve grandchildren, three of whom are quite young and who I miss terribly. My arms ache to hold them again, and that just isn't possible.’

Participants spoke of the limitations of interacting through online media. Judy (75 years) wrote: ‘Now I have reached a point of missing people grievously. 3D, not 2D.’ Rebecca (71 years) shared: ‘I miss my grandchildren so much. Even though we FaceTime, it's not the same as getting hugs and kisses.’

‘Normal’

The sense that normal life (i.e. routine, ease, security) was gone, possibly forever, was articulated throughout responses. Patty (66 years) explained, ‘Lack of spontaneity in life; can't just do things on a whim, have to put thought into it (and safety of self and others).’ Marcia (61 years) wrote, ‘Loss of control and opportunity to be “care free” in everyday life. Sad that things may not go back to “normal” and people will be less trusting of others and attitudes may divide us further.’

Participants grieved the loss of a ‘past way of life’ (Terry, 70 years) and daily routine. For Jennifer (56 years), the loss felt permanent: ‘Mourning the loss of what was normal everyday life and that it will never be like that again.’ The sense that this loss might go on for some time was articulated by Leslie (66 years): ‘I grieve the way we used to be. I don't like it when people say the new normal.’

There was a sense of sadness that the world would never be the same, and the implications of that reality for future generations. As Doris (59 years) reflected, ‘I fear that the world as I knew it is lost to us, that my children will have very different lives.’ As Bruce (57 years) reflected, his capacity to engage personally was waning given the loss of ‘Stability, a sense of security, a lack of permanence. The world is becoming a place I don't understand, and I'm finding it hard to muster the curiosity to understand it.’

Participants articulated a constant state of uncertainty, vulnerability and fear in daily life. Maureen (68 years) lamented: ‘The loss of casual interactions with others without fear.’ Wendy (68 years) similarly reflected, ‘Sad that even as things reopen, there is no longer a feeling of being safe and protected from potentially dangerous diseases.’ For Michele (62 years) there was a sense of hopelessness, ‘Mourning loss of security, sense that we are safe. That even when we follow the guidelines, limit out contact with others outside our home, and do everything right, we might still be infected with COVID-19.’

The extent to which others chose to follow precautionary guidelines impacted many participants’ senses of safety: ‘Loss of sense of safety among other people, given the number who seem eager to resume normal behaviors’, shared Randy (58 years). For some participants, this fear led to a change in behaviour: ‘I have become inordinately fearful of other people unknowingly spreading COVID-19 due to lax precautions on their part. I am extremely fearful of going to any public places due to this’ (Brian, 57 years). Frank (71 years) articulated, ‘There is NO protection for those following the guidelines, FROM those who will not follow the guidelines. Once you leave your home, one is vulnerable to non-compliant people and there are NO police, security people, etc. who will help.’

Some participants explained that their sense of fear might be permanent, even after a vaccine. Anna (70 years) explained, ‘I feel sad because life as I knew it will never be the same, and I won't feel comfort[able] out in public possibly even after a vaccine is developed.’ Similarly, Marsha (76 years) stated, ‘We know things will never be the same, but I miss the freedom to go about my days without worrying about whether I am exposing myself to a deadly virus.’

Personal health and wellness

Given the delay or cancellation of elective procedures, some participants grieved for their lack of access to the medical or dental care that they needed and felt uncertain about when procedures would be available in the future. Rose (68 years) explained:

I am furious for [the local health system] for cancelling all my health maintenance and surgery follow-ups, then advertising that we should not hesitate to seek care. I hate the feeling of ‘what's the point’ of trying to remain healthy if this is what life is going to be.

For Jo (66 years), not being able to receive care meant delaying a life-changing process: ‘The fact that much of my transitioning from male to female has been put on hold (ie electrolisis) [sic], transitioning in real life situation.’ For others, the concern of health-care access was related to the ability to have help come into their home, as Lynn (67 years) explained, ‘I am physically disabled and not able to do some things around the house. Due to the virus, I am not able to get help with these things and is a significant problem.’

Participants also shared concerns about their personal physical health related to past surgeries, ongoing chronic health issues and COVID-19 experiences. For Kimberly (60 years), the lack of group activities impacted her health: ‘Lack of the type of exercise I can do to keep my replaced knees in shape. Miss the type of Cardio I can do.’ Anita's (77 years) health limited her independence: ‘Not being able to do my own shopping. I finished cancer treatment just before the outbreak.’ Laurie (58 years) explained that given her ongoing health issues, she was, ‘grieving opening back up, I am enjoying everyone else living like I've been for the past 6 years’.

Several participants spoke of their experiences having COVID-19. For Carrie (69 years): ‘I am recovering from COVID-19 after 58 days and it's still difficult to breathe, but slowly getting better.’ Being sick with COVID-19 had large-scale implications for Josephine (66 years) as well: ‘I've had family problems since we all had the virus it created a lot of stress for me to be so ill. I moved in with a friend for the last month. My illness triggered my husband's anger issues.’ Other participants expressed health concerns related to COVID-19. Michelle (58 years) explained, ‘I am sick with a fever for 3 weeks. Once COVID-19 was ruled out, doctors lost interest in diagnosing me. I fear this could be a serious illness.’ Sally (60 years) explained, ‘I'm concerned that if I didn't have COVID-19 in March will I get it now. I'm concerned that the antibodies tests are wrong.’ Terri (70 years) was concerned about what it might be like to be infected: ‘I am terribly scared of having a stick test in my nose or throat for the virus and if I get it I am terrified completely frightened of having a ventilator.’ The possibility of becoming ill with the virus had Anthony (72 years) on edge: ‘I find it painful to view other people as viral vectors, a potential threat.’

Concerns were raised about one's own mental health ranging from chronic issues to more recent diagnoses, as well as general mental health implications due to the pandemic. Participants expressed feeling bored; overwhelmed; sad; hopeless; sorrow; terrified; malaise; lack of concentration, motivation, productivity or purpose; and not feeling like themselves. A few participants related their mental health to being retired. Vickie (64 years) explained, ‘I just retired and feel I have no purpose.’ Kim (72 years) shared: ‘The stillness at home says it all. I am retired and live alone and can't seem to get motivated.’

Some participants explained how the pandemic impacted their ongoing mental health concerns. Douglas (58 years) wrote about his experience, ‘playing HELL with my eating disorder … want to binge – can't, want to restrict – shouldn't.’ Lori (61 years) explained how her previous trauma has been affecting her lately: ‘I have [Complex Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder] and issues around abandonment. Isolation has been very hard for me to remind myself that my first impulse feelings are usually NOT correct.’

Some participants relayed their poor mental health more generally. As Ellen (65 years) reflected, ‘Is there anything I am NOT grieving or sad over?’ Elaine (72 years) shared: ‘I sometimes feel a sense of profound sadness, but unrelated to anything specific.’ Terry (81 years) had ‘Some degree of free-floating anxiety.’ Joanne (64 years) wrote: ‘I feel a vague sense of loss – but it has moved to a general state of numbness.’

Participants spoke of the experience of life being more taxing than usual. As Anne (65 years) wrote: ‘I regret my sloth, yet I'm very unmotivated to do anything useful.’ The theme of productivity resonated with Valerie (56 years) as well: ‘Feeling much less productive because all my additional time has not resulted in productivity.’ Alice (69 years) reflected:

I'm coping pretty well, but everything takes longer, with more effort, adding in mindfulness, esp[ecially] at work or essential errands; going on line for [unemployment insurance assistance]. By the end of the day I usually feel SATURATED or SPENT even though I don't feel like I've done as much as I hoped.

For some, the pandemic impacted their ability to seek mental health care. As Frances (62 years) explained, ‘Numbers continue to rise here and the situation is worse and I am afraid to call and make an appointment for depression.’ Suzanne (61 years) articulated, ‘My daily activity has definitely been impacted in a negative way, my anxiety level has become elevated, and I am now on medication.’

The lack of socialisation and connection posed mental health struggles. As Marie (56 years) explained, ‘The transition to socially isolating from friends feels permanent, [I] no longer desire to gather and socialize.’ For Victoria (62 years), the losses accumulated: ‘Loss of social contact, loss of feeling connected to co-workers, Loss of being able to shop, loss of my life – I feel I lost my spirit.’ Lillian (71 years) felt that the current situation held long-term implications: ‘Sad that my lonely life will never change … worried I will never be happy again.’

Social and civic cohesion

Participants expressed sadness, grief and mourning the breakdown of society and civic cohesiveness. Angela (65 years) shared: ‘Life most likely will never be the same. I anticipated the shut downs however did not comprehend the extent of the effects of shutting down a society and all those that need help.’ Participants expressed grief for the situations of those less fortunate, including the unemployed, homeless, impoverished, racial and ethnic minorities, people in extended care and nursing facilities, people in low-income countries, and those grieving the loss of loved ones to the virus. Sylvia (69 years) shared that ‘the suffering of so many people is heartbreaking’, particularly the disproportionate suffering and death in Black, Indigenous, and People Of Colour (BIPOC) communities.

Participants often discussed political events and social justice movements overlapping the COVID-19 pandemic, and their sadness resulting from widespread anger, divisiveness, civic unrest and stability. Scott (59 years) expressed that ‘our society in general is falling apart’. For Jill (84 years): ‘I've lost my belief in the basic goodness of the American people. I'm appalled by the selfishness and aggressive behavior of so many.’

Multiple participants expressed sadness at being pushed into extended isolation given the refusal of community members to wear a mask, and Dawn (63 years) shared ‘grieving what our society has come to when I am afraid of physical assault for wearing a mask’. Selfishness and self-centredness, lack of civic respect and care, cavalier attitudes, and refusing to be inconvenienced at the direct risk to vulnerable individuals were frequent topics of sadness and grief. ‘Sad/angry about the general ignorance and selfishness of much of the population regarding the seriousness of this pandemic, and their willingness to risk others for their own ends’, shared Sue (63 years).

The global impact of COVID-19 was of concern to many, as Constance (76 years) explained, ‘General grief at the horrible toll this is taking on everyone, can't get to next step in grieving cause it's the same everyday.’ Roger (73 years) explained his grief as being, ‘sad on a large scale, meaning for humanity around the world’. Sue (63 years) wondered how to move forward: ‘Uncertainty about how [we] have this be a moment that moves us toward a better world instead of a worse world.’ There was a sense among many participants’ responses that this could be a turning point for the USA as a country, and globally for humanity.

Work and finances

Participants expressed wide-ranging sources of grief and sadness related to their present and future financial security and employment. Some individuals had temporarily or permanently closed their own businesses. Many expressed sadness over loss of financial security and retirement savings. Joanne (74 years) shared:

I have financial security for the next month with unemployment and $600/week stimulus but am concerned that as all costs have increased my ability to at least stay even between income and basic expenses and have no reserve for emergencies (now have to have a tooth implant for $3000+). If, at age 74, I can continue my work, income will provide that but am not sure if [my] job will resume. My home is the place where the rest of my family live and I feel it is in jeopardy.

Participants such as Julia (65 years) shared: ‘Mourning the loss of my job. Becoming resigned to thinking I will never get called back.’

In addition to financial hardship, being furloughed or laid off caused sadness in the lack of routine, purpose and socialisation. Raymond (65 years) expressed: ‘I have (at least temporarily) lost two types of part-time employment. The money is not particularly [important] but I miss the variety, social connection and meaning they brought to my days.’ Participants missed their co-workers, students, customers and general day-to-day interactions in the workplace. Retiree Gwendolyn (78 years) shared: ‘I miss the camaraderie, companionship and feeling of accomplishment I normal[ly] get when I am able to do volunteer work.’ For those transitioning to online platforms and work-from-home, such as hospice volunteers and teachers, they felt less able to connect and fully support students, patients and families. They felt sad about the loss of connection.

Discussion

This nationwide study of over 2,000 US men and women aged ⩾55 in May to July 2020 indicated that grief experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic were diverse and highly personal, yet shared common themes. There was a sense of ongoing, pervasive loss across the study sample (Walsh, Reference Walsh2020). Given the individual nature of grief and bereavement, the long-term impacts of this experience may not be seen for some time (Goveas and Shear, Reference Goveas and Shear2020). For participants experiencing bereavement due to COVID-19 death, or deaths from other causes, the inability to visit their loved ones prior to death or to have meaningful rituals and collective mourning was especially distressing and led to additional heartache (Imber-Black, Reference Imber-Black2020). There is concern among grief experts that these experiences could lead to widespread prolonged grief disorder (PGD), as the circumstances of death and measures taken to address the pandemic (i.e. social distancing, no hospital visits) fit the risk factors for PGD (Goveas and Shear, Reference Goveas and Shear2020).

All of the themes identified in the study are connected through the lens of grief as an individual response to loss, which is not limited to bereavement (Harris, Reference Harris and Harris2020b). Many of the identified themes overlapped with each other as there was an overarching effect on one's wellbeing and way of life. We identified that feelings of loss during the pandemic extended beyond death, as individuals faced ongoing senses of tangible losses such as jobs, relationships and social networks, travel plans, and financial security; as well as intangible losses (Harris, Reference Harris and Harris2020d) of a sense of control, safety and normalcy. Primary losses such as employment can lead to secondary losses including independence and future stability (Zhai and Du, Reference Zhai and Du2020). Social distancing measures may lead to strains in relationships and loss of social connection altogether. For participants with grandchildren, there was a sense of loss of their future plans and goals (e.g. college, marriage, finances), and concerns about what the world might look like for them in the future. We identified a sense of vacillating between immediate here-and-now losses, and possible future losses, which is consistent with the literature (Walsh, Reference Walsh2020). Older participants often connected their grief experiences to having a sense of ‘limited time’ left, and an inability to accomplish their goals or dreams for this time of life, consistent with research on the experiences of individuals subjectively nearer to death (Kotter-Gruhn et al., Reference Kotter-Gruhn, Gruhn and Smith2010).

Many participants indicated an ongoing sense of loss of safety given the nature of the virus as being invisible and highly contagious. This experience of uncertainty and lack of control is consistent with the construct of a shattered assumptive world (Janoff-Bulman, Reference Janoff-Bulman1989, Reference Janoff-Bulman1992). From a young age, we form ideas and assumptions about the world around us, in terms of its predictability, safety, consistency, and our ability to enact control and influence over it (Harris, Reference Harris2020a). There were consistent concerns among participants about how to navigate the world during and after the pandemic (i.e. What does it mean to feel ‘safe’ again? Will we ever not feel vulnerable?). The loss of one's assumptive world is an experience of grief, as one's previously held beliefs, expectations and plans no longer exist in the way they once used to (Harris, Reference Harris2020a). As participants reflected on their day-to-day losses, there was a clear indication that they were currently living this loss of the world as they once knew it, in real time (Trzebiński et al., Reference Trzebiński, Cabański and Czarnecka2020).

Previous literature related to grief and bereavement from the COVID-19 pandemic has indicated concern for future outcomes for older adults (Armitage and Nellums, Reference Armitage and Nellums2020; Galea and Keyes, Reference Galea and Keyes2020; Miller, Reference Miller2020; Morrow-Howell et al., Reference Morrow-Howell, Galucia and Swinford2020), but, to the best of our knowledge, no qualitative research to-date has characterised the actual, tangible and intangible losses from COVID-19 through the lived experiences of older adults. The gap in relevant literature on the lived experiences of older adults in the pandemic could further disenfranchise the experiences of older adults and continue their isolation in society. The current study contributes to filling this gap by bringing to light lived experiences of grief and bereavement for older adults due to and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Results from this study bring attention to an often forgotten and dismissed age group, as well as to taboo topics such as death, grief and physical touch. These rich results can inform future interventions aimed at reconstructing the assumptive worlds of older adults as well as enhance our understanding of how grief manifests in older adults’ lives due to the COVID-19 pandemic and more broadly.

Strengths and limitations

The study has important limitations. We launched this study during the first upswing of the pandemic and did not capture people who may have been too sick to participate, such as those who were hospitalised with COVID-19 or other health conditions. Data collection early in the pandemic may not capture the full breadth and depth of grief experiences over time. Men, older adults from racial and ethnic minority groups, Spanish speakers, and those with high school education or less were underrepresented relative to the general population (Kobayashi et al., Reference Kobayashi, O'Shea, Kler, Nishimura, Palavicino-Maggio, Eastman, Vinson and Finlay2021). A strength is that our sample size was extremely large in comparison to traditional qualitative studies (Boddy, Reference Boddy2016), although our results derived from a single open-ended question. Hence, in-depth, case-oriented analysis was limited in the current study. Response richness was further limited by the survey format because we could not probe participants for further inquiry and follow-up (Finlay et al., Reference Finlay, Kler, O'Shea, Eastman, Vinson and Kobayashi2021, Reference Finlay, Meltzer, Cannon and Kobayashi2021). We did not distinguish grief experiences across socio-demographic and other characteristics. Further research should build upon this exploratory analysis to focus on variables associated with specific grief experiences (e.g. age, gender, race, ethnicity, income, marital status, geographic location) and health outcomes (e.g. anxiety, depression, self-rated health).

We endeavoured to group sub-themes and participant ideas commonly expressed together into overarching themes, but the boundaries imposed by the coding structure may artificially separate the interrelatedness of sources of grief and loss. A small number of participants responded that there was nothing they were grieving, mourning or sad about through generally brief responses such as ‘no’ or ‘not really’. Some stated that this was because life was unchanged, while others said that their worries were not significant enough to share.

Strengths of this study include its timeliness, since our data collection occurred early in the pandemic during a period of immense social, economic, political and public health upheaval. Our approach was responsive to sources of grief and loss that were uncommon prior to the pandemic onset, such as being unable to be physically present with an ill or dying loved one due to public health restrictions. The wide age range of participants accounts for a breadth of ageing experiences and perspectives, such as those who were working and retired, caring or being cared for, and those with high to limited mobility. The national coverage and large sample size of this study enhance the generalisability of our findings.

Conclusions

Results of this study may inform future research on the lived experiences of older adults during and following the COVID-19 pandemic. Research may focus on how to create a sense of safety and recovery, both individually and collectively, for older age groups. It is also important to address long-term implications of loss during this time, how older adults can safely move forward to inhabit public spaces, adjust to being in crowded areas without feeling anxious, and return to life knowing that life itself may never be the same (Monahan et al. Reference Monahan, Macdonald, Lytle, Apriceno and Levy2020).

This study also highlights the need to address grief and loss for all losses, not just those that are related to death. Many older adults are vulnerable and at-risk for grief and sadness due to myriad reasons, not all of which are obvious but might at times be hidden (e.g. quality of connection, yearning for physical touch). It is paramount for older adults to be able to express and heal their grief due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Mental health professionals will need to pay special attention to assess older adults appropriately to distinguish between depression and grief (Carr et al., Reference Carr, Boerner and Moorman2020; Goveas and Shear, Reference Goveas and Shear2020). A tool to do so is the recently created Pandemic Grief Scale (Lee et al., Reference Lee, Neimeyer and Breen2021; Lee and Neimeyer, Reference Lee and Neimeyer2020). Given the highly personal nature of grief and bereavement, supports and interventions to address the experiences of older adults during the COVID-19 pandemic will necessitate individualised approaches to bring healing and hope to vulnerable but resilient ageing populations.

Acknowledgements

We are thankful to the COVID-19 Coping Study participants, who took time out of their lives to share their experiences and perspectives with us.

Tamara L. Statz1, Lindsay C. Kobayashi2 and Jessica M. Finlay2,3*

Author contributions

LCK and JMF conceived of, designed and supervised the COVID-19 Coping Study. JMF and TLS conducted the analysis. JMF and TLS drafted the manuscript with input from LCK. All authors contributed to the interpretation of data, revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content, and read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Financial support

This work was supported by the Michigan Institute for Clinical & Health Research Postdoctoral Translational Scholar Program (JMF, UL1 TR002240-02); and the National Institute on Aging (JMF, Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award Individual Postdoctoral Fellowship, F32 AG064815-01). The financial sponsors played no role in the design, execution, analysis or interpretation of the data, or writing of the study.

Conflict of interest

The authors have no commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Ethical standards

The University of Michigan Health Sciences and Behavioral Sciences Institutional Review Board approved the study protocol (HUM00179632), and all participants provided written informed consent.