1. INTRODUCTION

Polanyi (Reference Polanyi2001 [1944]) described the social history of the 19th and 20th centuries as the result of a double movement: an unprecedented growth of market mechanisms, in parallel to the development of «a network of measures and policies (…) designed to check the action of the market relative to labour, land, and money» (p. 79). This process, he added, «may happen in a great variety of ways, democratic and aristocratic, constitutionalist and authoritarian» (Reference Polanyi2001 [1944], p. 259). Even today, however, there is no consensus on the impact of the political regime on the development of social policy. Initially, one would expect the expansion of suffrage and the advancement of democracy to have a positive effect (Lindert Reference Lindert2004; Haggard and Kaufman Reference Haggard and Kaufman2008). However, there are also examples of social policy being developed under non-democratic governments, such as that of Bismarck’s Germany. Indeed, Mulligan et al. (Reference Mulligan, Gil and Sala-i-Martin2010) and Cutler and Johnson (Reference Cutler and Johnson2004) take the view that dictatorships also have incentives to increase social spending, whether for reasons of economic efficiency or to achieve political legitimacy. In Spain, the development of social policy took place in the midst of a tumultuous political history with alternating democratic and non-democratic periods. This has made Spain into an interesting case study. Certainly, Spain’s most important difference with respect to Western Europe emerged after World War II, when democracy became well established in most European countries, while, in Spain, Franco’s dictatorship lasted until 1976/1977. According to Tusell, «if there exists a crucial break in the Spanish history, it is the one that occurred [during the Francoist dictatorship] after the civil war» (Reference Tusell2005, p. 11). One must ask, therefore, how these specific historical characteristics affected the development of social policy, and what lessons can be drawn from the Spanish case about the relation between the political regime and social spending.

This study examines the relationship between the political regime and social spending in Spain between 1850 and 2000 by means of a time series analysis. A long-term analysis such as the one proposed here is interesting for several reasons. The development of social policy is, in fact, a long-term process. In the Spanish case, as in many European countries, the origins of social policy can be traced back to the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Moreover, this process typically had a cumulative effect. The legislative momentum of a period often carries over into subsequent periods. If the historical perspective is not taken into account, it is easy to give credit to the wrong regime. However, most quantitative studies focus on shorter (and more recent) time periods, using panel-data sets. The main counterfactual is, therefore, the (political) experience of other countries, but the logic of the theories on the impact of the political regime on social spending refers to evolutions within a single country. In this sense, it is also interesting to analyse the impact of regime type within the same country across time.

The Spanish case is also interesting because, as noted earlier, the country went through numerous political regime changes between 1850 and 2000, alternating democratic and non-democratic periods. However, even though the history of Spanish social policy has been analysed extensively, there are no long-run, econometric analyses of the determinants of social spending. This paper is, therefore, a good complement to the existing historical studies and the hypotheses raised by them. The results indicate that democracy had a positive effect on both the levels of social spending and its long-term growth trend. With the arrival of democracy in 1931, the transition began from a traditional regime (with low social spending) to a modern regime (with high social spending). Franco’s dictatorship, however, interrupted this process, retarding the positive growth in social spending. Additionally, the effect of left-wing parties was more significant in the 1930s (prior to the Keynesian consensus) and in the Bourbon Restoration (when low-income groups’ preferences were systematically ignored) than in today’s democracy. This paper, therefore, contributes to the literature on the relationship between the political regime and social spending, and the literature on the impact of partisanship on social spending.

2. DEMOCRACY, POLITICAL PARTIES AND THE WELFARE STATE

Early studies of the origins of the welfare state attributed its emergence and subsequent development to modern economic growth and industrialisation, which generated new social needs while the traditional social protection systems of rural societies eroded. In this context, it became necessary to find new solutions, involving rising levels of state interventionism (Kerr et al. Reference Kerr, Dunlop, Harbison and Myers1964; Pampel and Weiss Reference Pampel and Weis1983). Wilensky (Reference Wilensky1975), indeed, considers that economic growth and the ageing of the population (one of the principal by-products of economic growth) are the most important factors to account for the growth in social spending in advanced countries. Other studies, however, have accorded greater importance to the role of political factors. According to Lindert (Reference Lindert2004), for instance, the gradual expansion of voting rights had a positive effect on social spending in 1880-1930. Bringing low-income groups into the political process led to increased political support for redistribution. Similarly, Haggard and Kaufman (Reference Haggard and Kaufman2008) and Espuelas (Reference Espuelas2012) contend that democracy had a positive effect on social spending in Europe and several developing countries after World War II.

To the extent that the expansion of suffrage to all citizens shifted the median voter downward, these findings are consistent with Meltzer and Richard’s (Reference Meltzer and Richard1981) hypothesis. In democracy, one would also expect a convergence between political parties towards the preferences of the median voter (Downs Reference Downs1957). However, political parties do not always behave as the perfect agents of voters. They often have their own interests and preferences, and the ability to set the political agenda. When they choose which laws and proposals are debated and which are not, they can push the result (at least partially) away from the preferences of the median voter and closer to their own preferences (Krehbiel Reference Krehbiel2004). This means that political parties ideologically committed to the development of social policy can (potentially) influence the political agenda by prioritising social issues, and vice versa. Political parties opposed to social spending can influence in the opposite direction. The theories that have, doubtless, paid the most attention to the role of political parties in the development of social policy are the so-called power-resource theories.

According to these theories, democracy is positive for social policy, but it is seen as a necessary condition, not a sufficient one. For democracy to have a positive effect, the working class must take advantage of the opportunities afforded by democracy, organising trade unions and strong political parties (Korpi Reference Korpi1983). Hicks (Reference Hicks1999) contends that the mobilisation of the working class did, in fact, play a key role in the initial stages of social policy. By 1920, only those countries with a strong labour movement had introduced three of the four most important types of social insurance: workplace accident compensation, old-age pensions, health insurance and unemployment insurance. However, Hicks also notes that the role of social democracy became blurred after World War II, when the Keynesian consensus prevailed. Only in the 1970s and 1980s, when that consensus began to break apart, did social democracy again resume a prominent role in the defence of the welfare state in some countries. Wilensky (Reference Wilensky1981), however, maintains that Catholic parties were the greatest proponents of the development of social policy after World War II. Manow and Van Kersbergen (Reference Manow and Van Kersbergen2009), instead, point out that this was the case primarily when they had to compete electorally against social democratic parties.

Shifting the focus slightly, Bradley et al. (Reference Bradley, Huber, Moller, Nielsen and Stephens2003) contend that if, instead of analysing aggregate social spending levels, one examines the ability of social policy to reduce inequality (after taxes and transfers), then left-wing governments show a clearly positive effect. The reason is that in countries dominated by Christian-democrats, social benefits may be relatively generous, but social policy tends to reproduce market inequalities. By contrast, in countries with greater prevalence of left-wing governments, social policy is more redistributive. These results, in turn, are consistent with the three types of welfare regimes proposed by Esping-Andersen (Reference Esping-Andersen1990).

Apart from these debates over the ideology of the party in government, there is also no consensus on the role of democracy per se. Mulligan et al. (Reference Mulligan, Gil and Sala-i-Martin2010), for instance, find that democracies are not more active than dictatorships in promoting growth in social security spending. Indeed, they consider that political institutions are irrelevant in this sense. In line with Wilensky (Reference Wilensky1975), they claim that the really important variables are economic growth and the ageing of the population. Either of these variables would translate into growth in social security spending independently of the mechanisms of political participation. The authors do not explain in detail which alternative mechanisms are in operation in that case, but they mention the action of pressure groups and efficiency reasons. According to Sala-i-Martin (Reference Sala-i-Martin1996), for example, pensions improve the average stock of human capital in the economy, thereby generating positive externalities on economic growth and productivity. This would explain why both dictatorships and democracies have promoted their expansion. Cutler and Johnson (Reference Cutler and Johnson2004), for their part, do not deny the importance of political factors, but they also think that dictatorships can stimulate the development of social policy in order to achieve political legitimacy and hold onto power.

This same idea has been echoed by Acemoglu and Robinson (Reference Acemoglu and Robinson2005), who nonetheless pay more attention to the incentive problems behind it. In a dictatorship, all formal political power, or de jure power, is in the hands of the governing elite. Only if the citizens are able to solve their collective action problems and organise themselves successfully can they achieve some de facto power that might pose a real threat to the government. At that point, the government will have incentives to make social concessions and maintain itself in power. However, as all de jure power is in the hands of the government, it will have no reason to keep its social promises as soon as the opposition demobilises. If citizens know this, they will not trust government’s social promises and will refuse to demobilise (making social concessions useless for the elite). In other words, even if the government is (initially) interested in making social concessions, it needs to find a way to solve its commitment problems and make credible promises. Otherwise, political concessions will not be implemented. However, even if this is the case, redistribution in a dictatorship will be lower than in a democracy. The main reason is that citizens’ de facto power is temporary and, therefore, redistribution levels will only partially reflect the preferences of the majority of the populationFootnote 1 .

From a historical perspective, the package of measures approved by Bismarck in Germany would be a typical example of this sort of behaviour. Bismarck himself acknowledged in his address in the Reichstag in 1881 that the measures were partly a response to «the excesses of the socialists» (Rimlinger Reference Rimlinger1971, p.112). In the terms used by Acemoglu and Robinson, the de facto power of the German labour movement had succeeded in forcing social concessions from the government. Power-resource theories have focussed their attention primarily on the role of left-wing parties in democracy. However, following the logic of Acemoglu and Robinson (Reference Acemoglu and Robinson2005), the role of the labour movement (and generally of any other opposition movement) could be equally important in non-democratic contexts. This is actually what is suggested by a number of qualitative studies of the history of Spanish social policy.

3. SPANISH SOCIAL POLICY HISTORY

At the close of the 19th century, a portion of the Spanish political elite began to express support for the development of social policy. They thought that it could be an effective means to safeguard political stability amid the advance of the labour movement and industrialisation. The publication of the encyclical Rerum Novarum in 1891 (in which the Church acknowledged that private charity was not enough to solve social problems) plus the package of social measures applied by Bismarck in Germany served as models and inspiration. Also, the introduction of universal male suffrage in Spain in 1890 aroused fear in some political sectors. Cánovas del Castillo (who was prime minister several times between 1875 and 1897) was himself convinced that there could not be «universal suffrage without having a little sooner or a little later the practicing of state socialism» (1890, p.30). This is why he saw Bismarck’s social policy as «a farsighted conception of the political necessities created by the impotence of the old economic dogmas, combined with (…) the agitation of the proletariat and the existing political system [universal male suffrage] » (1890, p.38). In that context, the government decided to create the Commission of Social Reforms in 1883. Its most important work was the so-called «Spoken and Written Information (1889-1893) », a detailed study of the situation of the working class that compiled a great deal of information. However, the effort was not translated into any specific measures. In 1900, social protection still relied on private charity and the public system of poor-relief instituted with the Law of 1849.

The path towards social insurance was opened with the 1900 Law of Occupational Accidents. The impact of this measure, however, was very limited. Benefits and resources for prevention were very low, limiting social spending growth, and enterprises often failed to fulfil their commitments due to the lack of inspection (Silvestre and Pons Reference Silvestre and Pons2010). Shortly afterwards, in 1908, the government set up the National Institute of Social Insurance (INP in Spanish, for Instituto Nacional de Previsión). The INP was charged with managing the so-called Retiro Obrero, or «Worker’s Retirement», a state-subsidised, voluntary system for old-age pensions. This new programme, however, also grew very slowly. In 1918, the total number of insured persons stood at only 78,166, representing in the vicinity of 1 per cent of the labour force (Elu Reference Elu2006). After World War I, social legislation received a new impetus. From 1917, there was intense social unrest as a consequence of the economic imbalances caused by the war and the contagious effect of the Russian Revolution. The government tried to regain political stability through a policy of social concessions; in 1917 (in the so-called Conference of Social Insurance) it made a commitment to create a comprehensive social insurance system (which was supposed to cover occupational accidents, old-age, illness, maternity and unemployment). Between 1917 and 1923, a scheme for unemployment insurance and a scheme for health and maternity insurance were discussed in both the INP and the parliament. The socialist party (which in 1910 had won its first seat in parliament) demanded in its parliamentary speeches that the government honour its social promises. However, the only programme that came to fruition was the Retiro Obrero Obligatorio, or «Compulsory Worker’s Retirement», a compulsory old-age pension system created in 1919Footnote 2 (Elu Reference Elu2006; Pons and Vilar Reference Pons and Vilar2014).

Even though Cánovas del Castillo was convinced that universal suffrage would lead inevitably to socialism, Spanish social policy progressed very slowly during the Bourbon Restoration period (1874-1923). According to Guillén (Reference Guillén1990), corruption, electoral fraud and caciquismo (a system of patronage and dominance by local bosses that was particularly widespread in rural areas) enabled the political elite to ignore bottom-up demands, especially before World War I. From this perspective, the few social achievements that occurred before 1914 would primarily have been top-down initiatives coming from the political elite itself. Other authors, by contrast, take a more nuanced view and contend that this top-down shift in attitude cannot be explained without the «Disaster of ‘98» (the political crisis occurring after the independence of Cuba and the Philippines) and the gradual growth of the labour movement (Gabriel Reference Gabriel2004; Castillo and Montero Reference Castillo and Montero2008). However, even at times of social unrest (such as after World War I), the government was unable to keep its social promises.

In 1923, after the military coup and the installation of Primo de Rivera’s dictatorship (1923-1930), the momentum of the preceding years ground to a halt. The proposed schemes for unemployment and maternity insurance were abandoned. Pre-existing insurances, such as workplace accident insurance and old-age pensions, however, continued to operate; and subsidies for large families were created in 1927, a policy that was consistent with Catholic social morality and the influence acquired by the Church during the dictatorship (Velarde Reference Velarde1990). Indeed, the dictatorship strove for social pacification through a combination of repression and the establishment of corporatist formulas. The Confederación Nacional del Trabajo, which was the anarchist trade union and the largest at the time, was persecuted, but at the same time joint committees were created to try to regulate collective bargaining with the participation of the Unión General de Trabajadores, the socialist trade union (Pérez Ledesma Reference Pérez Ledesma1990). With the advent of the Second Republic (1931-1936), which is viewed by Linz et al. (Reference Linz, Montero and Ruiz2005) as the first truly democratic period in Spanish history, social legislation received a new impetus. Progress was particularly striking in the first 2-year period, when the socialist party was in government (Samaniego Reference Samaniego1988). The Constitution of 1931 recognised the right to social security. Between 1931 and 1932, maternity insurance (which delivered maternity-leave benefits and healthcare during childbirth for working women) came into effect; a voluntary, state-subsidised unemployment insurance scheme was set up; occupational accident insurance was made compulsory and coverage was extended to agricultureFootnote 3 . Also, a plan was devised to unify social insurances, with the aim of creating a single system of social security encompassing maternity and old-age insurances, which were already in existence, along with new insurances covering illness, disability, orphans and widows. Finally, the government put heavy investment into public works to combat unemployment, especially in rural areas, and strove to carry out an agrarian reform to reduce social unrest in the countryside and consolidate the democratisation process initiated in 1931. However, the outbreak of the civil war (1936-1939) thwarted these plans.

After the civil war, Franco’s dictatorship combatted social unrest through a combination of severe political repression and a precarious social safety net, which was fundamentally targeted at low- and medium-income industrial workers. Most of the social insurance schemes created before the civil war continued to operate, but the dictatorship abolished the existing unemployment insurance and shelved the Republican project of social insurance unification. New insurance programmes, however, were also created. In 1938, for example, before the end of the civil war, a family allowance called Subsidio Familiar was introduced. This offered bonus payments to all (male) wage-earners based on the number of children. This programme was largely the result of the anti-feminist and pro-population-growth ideology of the dictatorship (Espuelas Reference Espuelas2012). Retirement pensions were overhauled in 1939, introducing a pay-as-you-go system with flat-rate pensions. Rural workers were initially excluded, but were reincorporated in 1943. Disability and widows’ pensions, for their part, were introduced as a specific case of old-age pensions in 1947 and 1956, respectively (note, however, that these benefits had already been envisaged in the Republican project for social insurance unification in 1936).

A compulsory health insurance scheme (SOE in Spanish, for Seguro Obligatorio de Enfermedad), was set up in 1942, becoming a key piece in the dictatorship’s political propaganda (Pons and Vilar Reference Pons and Vilar2014). At first, coverage was limited to industrial workers. Permanent and casual agricultural workers were not incorporated into the SOE until 1953 and 1958, respectivelyFootnote 4 . Occupational health insurance, for its part, was not put into operation until 1947, even though the framework law had originally been approved in 1936, in the Second Republic. Rural and urban workers remained in separated schemes for occupational accidents until 1955 (Pons Reference Pons2011). However, the insurance that lagged most was unemployment insurance, which was not instituted until 1961 (Espuelas Reference Espuelas2013). In addition to this network of independent social insurance schemes, the dictatorship also created the so-called Labour Mutualism (or Mutualismo Laboral). Formally, it was a series of mutual associations financed and administered by employers and workers, grouped by economic sectors. In practice, however, Labour Mutualism was tightly regulated and overseen by the state (setting benefit levels, access conditions, the amount of employers’ and workers’ contributions, etc.). This turned it de facto into a parallel system to the official social insurance schemes (De la Calle Reference De la Calle1994).

This piecemeal approach started to be corrected in 1967, when the Social Security reform of 1963-1966 came into effect. Existing social programmes were brought together under a single, more streamlined social security system, and coverage was extended to all wage earners (instead of limiting it to low- and medium-income workers)Footnote 5 . However, Spanish social policy continued to marginalise the population without stable ties to the labour market and the funding of social security continued to rely on employers’ and workers’ compulsory contributions (with almost no public funding) throughout the dictatorship (Comín Reference Comín2010a). In spite of the limitations, social spending began to grow rapidly after 1967. This increase also coincided with a period of rapid economic growth. For Rodríguez Cabrero, the development of social policy in this period was «the necessary response to late Fordism (…) and to an urbanising society» (Reference Rodríguez Cabrero2004, p. 76). Since it was a necessary response, it follows that the dictatorship was not a significant obstacle to social policy. Guillén (Reference Guillén2000) goes slightly further and maintains that Francoist leaders promoted social insurance to improve the regime’s political image. In some cases, she argues, (such as that of health insurance), the dictatorship was even more effective than democracy when it came to ignoring pressure groups opposing compulsory insurance (such as employers, insurers and medical professionals).

Navarro (Reference Navarro2000), by contrast, contends that the political repression of Franco’s dictatorship was particularly severe on the labour movement and low-income groups, halting the development of social policy. Comín (Reference Comín2010b), indeed, considers that dictatorship and welfare state are incompatible concepts, as the development of the welfare state requires some kind of social pact. Social dialogue, indeed, played a crucial role in the transition to democracy. In 1977, the Moncloa Pacts were signed against a backdrop of acute economic crisis. Representatives of workers, employers and the main political parties agreed to implement policies of wage moderation, macroeconomic stabilisation and inflation control in return for greater social protection, progressive fiscal reform and the consolidation of political freedoms. These Pacts were crucial for the consolidation of democracy and economic stability. The introduction of income tax in 1977 broke one of the most important historical barriers to the development of Spanish social policyFootnote 6 . From then on, rising government subsidies were allocated to social security institutions (which had previously been funded almost exclusively through compulsory contributions from employers and workers). Access to healthcare was universalised in 1986. In 1982, welfare benefits for disabled persons improved dramatically and, in 1990, new non-contributory, old-age and disability benefits were introduced. Also in the 1990s, the governments of Spain’s autonomous communities gradually introduced minimum income programmes for low-income families.

All of this represented a gradual improvement in social provision and permitted coverage to be expanded to sectors without stable ties to the labour market (although non-contributory benefits lagged far behind contributory benefits). Despite the advancements, however, there were moments at which the development of social policy appeared to decelerate during democracy too. The belated modernisation of Spanish social policy took place in an adverse international context. The Keynesian consensus, built after World War II, was being challenged, especially after the electoral victories of Reagan and Thatcher. Even social democratic and labour parties in several European countries accepted the logic of marketisation and public spending control, leading to the so-called «third-way» (Wilson and Bloomfield Reference Wilson and Bloomfield2011; Offer and Söderberg Reference Offer and Söderberg2016). In Spain, Comín (Reference Comín2008) identifies a period of rapid expansion of social spending in 1977-1984. Then, from 1985 onwards, the Spanish government introduced a number of measures to limit social spending. This new tendency consolidated after the Maastricht Treaty of 1992-1993 (when economic policy became primarily targeted at controlling public deficit and inflation) and particularly after the Toledo Pact of 1995, which was aimed at ensuring the financial stability of the pension system. However, it would be precipitate to conclude that democracy did not have a positive impact on social policy. As Comín (Reference Comín2008) indicates, Spain (gradually) converged to the European levels after democratisation in 1977. The next section contributes to this debate by means of a time series analysis.

4. EMPIRICAL TEST

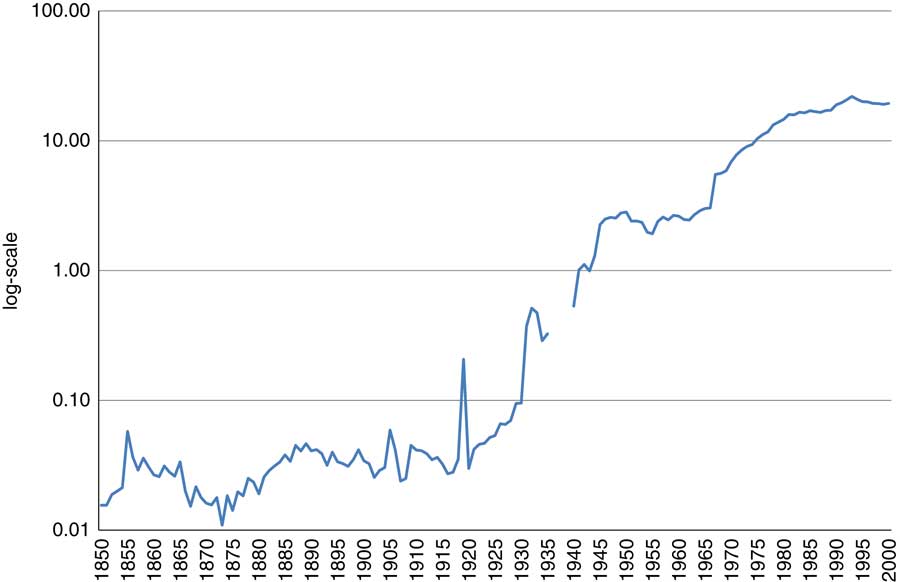

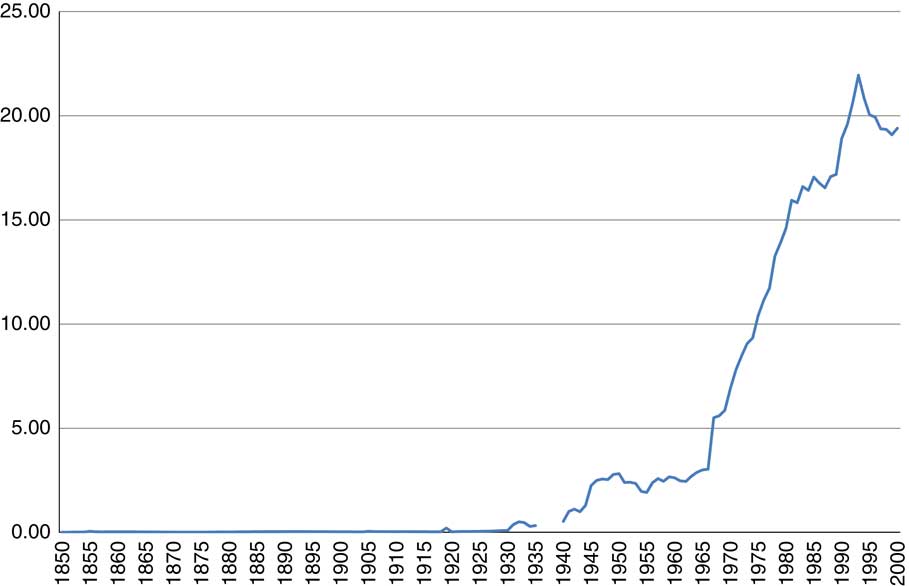

Figure 1 shows the evolution of Spanish public social spending in 1850-2000 as a percentage of GDP. The data come from Espuelas (Reference Espuelas2013), and fit the OECD’s definitions of public social spending. As can be seen, Spanish social spending remained practically stagnant with minor fluctuations until 1919. At that point, a period of growth began, including the years of Primo de Rivera’s dictatorship. In 1931, with the advent of the Second Republic, social spending growth accelerated, and kept growing in the years immediately after the civil war (probably because previous programmes were maintained and new ones, such as family allowance and sickness insurance, were introduced). Social spending then remained stagnant between 1945 and 1965, during Franco’s dictatorship. Subsequently, a new period of social spending growth began in 1966-1967, which continued during the transition to democracy, until it finally stabilised at relatively high levels from 1993 onwards.

FIGURE 1 SPANISH PUBLIC SOCIAL SPENDING (PER CENT OF GDP), 1850-2000 Source: Espuelas (Reference Espuelas2013). The Appendix reports the data without the log-scale. The series includes social spending by the Spanish central government, the autonomous communities, and the Social Security benefits. Municipal and provincial social spending has been excluded, because they have many gaps; fewer than 90 observations are available. Moreover, the series are not cointegrated when we use this smaller and discontinuous sample. Nonetheless, excluding local social spending should not mean a significant change, as Spanish social insurance development was the sole responsibility of the central government (and the autonomous communities after their creation). Following Lindert (Reference Lindert2004), civil servants’ pensions have also been excluded. Instead of reflecting a turning point in the state’s general social protection policies, these are rather the result of the particular employment relation between the state and its employees, so that the political economy behind them might be different. The main results hold when civil servants’ pensions are included (although some interesting patterns for the period before 1931 are hidden, see footnote 14). Results are available upon request.

At a glance, it is again hard to find a clear pattern between social spending growth and the political regime. For a more formal analysis of the role of the political regime, the following equation has been estimated:

where SS is Public Social Spending (as a per cent of GDP); PR the Political Regime in power at each moment; PM the Political Mobilisation; and Z stands for a set of control variables. The data on SS are the ones shown in Figure 1. As indicated before, the period 1850-2000 covers several regime changes; the year 2000 involves a reasonable time-span after the arrival of democracy in 1977, allowing us to test the impact of democracy as well as the impact of partisanship (as there were several centre-right and centre-left governments in this time period). To measure the impact of Political Regime, Spanish political history has been divided into several periods based on the definition of democracy provided by Boix et al. (Reference Boix, Miller and Rosato2012). According to these authors, a country is democratic if it meets a few minimum requirements. It is considered democratic, first, if it holds competitive elections (i.e. if the executive depends on the voters and if elections are free, without coercion by the executive or electoral fraud or corruption); and second, if at least 50 per cent of the male population can vote. From here, they have created a new database with a dichotomous indicator on the existence of democracy, which includes 219 countries in 1800-2007. According to their data, Spain has been democratic in 1931-1936 and from 1977 to the present. Even though the other periods were not democratic, neither were they homogeneous. Before World War I, for example, Spain had universal male suffrage (although caciquismo, fraud and electoral corruption prevent it being considered a democracy). Prior to 1890, there was census suffrage and after the Spanish civil war, the country was ruled by a military dictatorship.

For the purposes of this paper, it is interesting to examine whether each of these political regimes had a differentiated impact on social spending. Lindert (Reference Lindert2004), for instance, notes that democracy had a positive impact on social spending, but that the most negative effect was not the result of dictatorships but rather of elite democracies (with census suffrage). Accordingly, the years in which Spain was not democratic have been divided into three periods: the years of census suffrage (when only a small portion of the population was allowed to vote); the years of universal male suffrage (when most of the male population was allowed to vote, but, as previously noted, the elections were not competitive), and the years of dictatorship that followed the military coups of 1923 and 1936. In the econometric analysis, therefore, three dummy variables have been introduced, taking value one in the years of universal male suffrage (1868-1877; 1890-1922), democracy (1931-1936; 1977-2000) and dictatorship (1923-1930; 1939-1976), and value zero otherwiseFootnote 7 . The years of census suffrage or elite democracy have been used as a baselineFootnote 8 .

In addition to political regime, the analysis includes a variable called, for the sake of simplicity, Political Mobilisation. The reason for this is that several of the theories mentioned in section 2 hold that the political regime is conditioned by the political pressure that citizens or given organised groups are able to exert from below. In power-resource theories, for example, for a democracy to have a positive effect, the working class must take advantage of the opportunities afforded to them by democracy and vote for left-wing political parties. To control for this and correctly assess the political regime effect, I have included a dummy variable, taking value one in the (democratic) years where there were left-wing governments and zero otherwiseFootnote 9 . The data come from Linz et al. (Reference Linz, Montero and Ruiz2005) and the expected sign of this variable is positive. On the other hand, in the years of universal male suffrage, the political process was not fully democratic, but there was some pluralism and the socialist party was allowed to stand for election. The power-resource theories refer exclusively to democratic periods. However, as noted in section 2, it seems reasonable to assume that social democracy might also have had a positive effect on social spending even in not fully democratic times. For this reason, the regressions also include the interaction between the variable for universal male suffrage and the percentage of the socialist party’s seats in the Spanish parliament in that period. The expected sign of this variable is positive. Once again, the data come from Linz et al. (Reference Linz, Montero and Ruiz2005).

Lastly, following the model of Acemoglu and Robinson (Reference Acemoglu and Robinson2005), the political mobilisation of opposition groups under dictatorship might have some impact on social spending. In the final years of Franco’s dictatorship, opposition movements (among which the labour movement played a very significant role) took on growing importance (Tusell Reference Tusell2005). Because these movements were underground, however, there are no data to determine precisely the extent of political mobilisation, either in the labour movement or in the political opposition in generalFootnote 10 . To measure government’s response to bottom-up pressure, I use the number of government changes in the preceding 5 years as an indicator of political instability. The data come from Urquijo (Reference Urquijo2001). This variable, however, does not exclusively reflect the opposition’s ability to mobilise under dictatorship. It also reflects possible internal government crises (due to succession crises or to external shocks, such as an economic crisis). Nevertheless, these crises are windows of opportunity that increase the effective pressure that can be exerted by the opposition (Acemoglu and Robinson Reference Acemoglu and Robinson2005). As a result, they do not affect the core argument. What is relevant here is whether the government increases social spending when it is unstable and needs political legitimacy. The expected sign is positiveFootnote 11 .

The control variables include GDP per capita, the percentage of population over 65 years old, trade openness, inequality level and government’s fiscal capacity. GDP per capita figures come from Prados de la Escosura (Reference Prados de la Escosura2003). The data on the percentage of population over 65 years old come from Nicolau (Reference Nicolau2005). Trade openness is measured as the sum of imports plus exports divided by GDP. The figures come from Tena (Reference Tena2005). Inequality figures correspond to the Gini index prepared by Prados de la Escosura (Reference Prados de la Escosura2008), and the government’s fiscal capacity has been measured by the ratio between the central government’s tax revenues and the outstanding public debt (also of the central government). The larger this quotient is, the greater the state’s fiscal capacity is understood to be. The expected sign of this variable is, therefore, positive. The data come from Comín and Díaz (Reference Comín and Díaz2005). All the variables are in logarithms to derive elasticities.

5. RESULTS

Since the analysis involves time series, before moving on to the regression analysis, we first tested whether or not the series are stationary. The augmented Dickey-Fuller test and the Phillips-Perron test were applied to the series included in the model. The results indicate that all of them are integrated series of order one, I (1) (Table 1). We then tested whether the series are cointegrated. The Engle-Granger cointegration test was applied to the residuals of the ordinary least squares (OLS) estimation in Table 3. The results confirm that the series are cointegrated (see Table 2). When the series are cointegrated, the OLS estimator is consistent, but it presents problems of asymptotic bias and is not an efficient estimator. In order to give robustness to the analysis, in addition to the least squares estimation, I have also reported the results using dynamic least squares and fully modified least squares. Both of these methods can deal with possible problems deriving from the existence of a cointegration relation. The first method does so by including lags and leads of the stochastic regressors in differences, while the second uses a semi-parametric correction of the least squares estimator (Phillips and Hansen Reference Phillips and Hansen1990; Stock and Watson Reference Stock and Watson1993). Both estimators are equivalent and asymptotically efficient.

TABLE 1 UNIT ROOT TESTS

Note: Null hypothesis: the variable has a unit root.

***Rejection at 1%.

TABLE 2 ENGLE-GRANGER COINTEGRATION TEST

Notes: Test from the regressions in Table 3.

Null hypothesis: series are not cointegrated.

***Rejection at 1%.

Regression results appear in Table 3. The control variables are, in general, significant and have the expected sign. The ageing of the population, for example, shows a positive and statistically significant sign, in line with the studies by Lindert (Reference Lindert2004) and Mulligan et al. (Reference Mulligan, Gil and Sala-i-Martin2010). GDP per capita, in turn, presents a negative sign, suggesting that social spending was countercyclical (it should be kept in mind that variables are in logs, reflecting elasticities). In this respect, it seems that if there was any modernisation effect associated to social spending growth it has been captured in the regressions by the ageing of the population (which is, in part, a by-product of economic development)Footnote 12 . Inequality shows a negative coefficient too, confirming Lindert’s Robin Hood paradox and previous results by Espuelas (Reference Espuelas2015). Trade openness, meanwhile, shows a positive sign. Apparently, the demand effect proposed by Rodrik (Reference Rodrik1997) predominated over the race to the bottom effect, confirming the results by Sáenz et al. (Reference Sáenz, Sabaté and Gadea2013) for Spain in 1960-2000. Finally, fiscal capacity appears statistically non-significant. This does not mean, however, that high social spending can be maintained over time without increasing taxation at some point. This simply means that variations in social spending are not correlated to variations in fiscal capacity. In 1977, for example, when income tax was introduced (after the advent of democracy), social spending had been growing since around 1967. The 1977 tax reform made social spending growth sustainable over time. However, the increase in social spending and fiscal capacity creation did not occur at exactly the same moment.

TABLE 3 POLITICAL REGIME AND SOCIAL SPENDING (1850-2000)

Notes: All regressions include a time dummy for the post-Spanish-civil-war period. Espuelas (Reference Espuelas2013) warns that there is a jump in his social spending series in 1967 due to problems in the original sources. To control for it, I have included a time-dummy for the time period after that year. The main results remain when these time-dummies are removed, although the general fit of the regressions decreases.

OLS=ordinary least squares; DOLS=dynamic least squares; FMOLS=fully modified least squares.

Standard errors in brackets.

***P<0.01, **P<0.05, *P<0.1.

As for the political variables, the results show that the introduction of universal male suffrage in 1890 had a gross negative effect. However, the coefficient associated with the percentage of the socialist party’s seats has a positive sign, which is significant in all equations and greater than the negative coefficient of male suffrage. Taking into account that this variable is a percentage that ranges between 0 and 100, the size of the coefficient indicates that the negative effect of universal male suffrage would be offset by <1 per cent of the seats being occupied by social democrats. These results confirm that caciquismo, corruption and electoral fraud were successful in neutralising the potential positive effect of universal male suffrage; but, at the same time, suggest that even in a fraudulent system like that of the Bourbon Restoration, political leaders were not entirely immune to demands from below. The results, actually, indicate that the political elite became willing to make social concessions in the face of the electoral advance of social democracy (despite the fact that the latter never rose above a very low level of representation). This confirms the importance that qualitative studies have placed on the rise of the labour movement in the beginnings of Spanish social policy (Gabriel Reference Gabriel2004; Castillo and Montero Reference Castillo and Montero2008). Also, this concurs with the results of Curto-Grau et al. (Reference Curto-Grau, Herranz-Loncán and Solé-Ollé2012), which show that public investment in roads in 1880-1914 was partly motivated by the government’s pursuit of political stability. Indeed, the gradual (and small) increase in electoral representation of Spanish social democracy after 1910 coincided with a period of increased social unrest. In this sense, it is likely that the positive statistical effect of social democracy is, in fact, capturing the elite reaction to that increase in political instability (and not only the effect of the electoral growth of social democracy)Footnote 13 .

Democracy, for its part, has a clearly positive and statistically significant effect. The extension of voting rights to the whole population stimulates social spending growth. The size of the coefficient, moreover, is much greater than in the case of male suffrage and dictatorship. Instead, the coefficient associated with the variable dictatorship is not statistically significant, indicating that its impact on social policy was similar to that of the years of elite democracy (our baseline period). By contrast, the number of government changes under dictatorship does have a positive effect and is statistically significant. This suggests that dictatorships responded to political instability with social spending increases. However, the size of the coefficient is much smaller than that of the variable democracy, meaning that the positive effect of political instability (under dictatorship) falls far short of offsetting the negative effect that derives from the absence of democracy.

Lastly, the presence of left-wing parties in government during the years of democracy did not have any significant effect on social spending. This is partly explained by the arrival of democracy per se, which obliged all parties to take into account the preferences of all voters (including low-income voters). Also, the emergence of the Keynesian consensus in Europe after World War II further helped to blur the distinctions between left-wing and right-wing parties (Hicks Reference Hicks1999). In Spain, the (belated) equivalent of the Keynesian consensus came with the 1977 Moncloa Pacts, in which the main political parties agreed, as noted earlier, to implement a policy of wage moderation and inflation control in return for the introduction of income tax and social policy expansion. Thus, social spending began to grow rapidly from the outset of democracy, including the first centre-right governments of the UCD party (Union of the Democratic Centre) and later socialist governments (1982-1996). The rapid social spending growth of the early democratic years could also be interpreted as the result of the backwardness accumulated during Franco’s dictatorship. Huber et al. (Reference Huber, Mustillo and Stephens2008), indeed, also found (for Latin American countries) that partisanship had no effect on social spending after highly repressive, dictatorial periods. They argue that left-wing parties entered democratic periods as relatively weak actors. On the other hand, after 1985 and, especially, after the Maastricht Treaty of 1992-1993, both socialist and centre-right governments of the Partido Popular (1996-2000) have given greater priority to public deficit and inflation control than to social spending expansion.

In the Second Republic, however, the qualitative evidence suggests that the consensus in favour of social policy was smaller and that the socialist party (together with other left-wing parties) actually went to great lengths to put social issues at the centre of the political agenda (Samaniego Reference Samaniego1988). To test this possibility, the regressions in Table 3 have been repeated, but this time including a multiplicative variable for the years of the Second Republic. The results must be interpreted with caution because this period was very short and, therefore, there are few available observations. As shown in Table 4, left-wing governments during the Second Republic effectively had a positive impact on social spending. This seems to confirm Hicks’s (Reference Hicks1999) hypothesis that differences between left-wing and right-wing parties were more significant before the Keynesian consensus.

TABLE 4 LEFT-WING GOVERNMENTS’ IMPACT BEFORE 1936

Notes: Standard errors in brackets.

OLS=ordinary least squares; DOLS=dynamic least squares; FMOLS=fully modified least squares.

***P<0.01, **P<0.05, *P<0.1.

However, one potential concern when analysing the relation between the political regime and social spending arises with the possible issue of endogeneity. Since social spending contributes to political stability, it might influence the type of political regime. Also, if redistribution demands are high, high-income groups may prefer non-democratic regimes (Boix Reference Boix2003). Both cases would raise an issue of inverse causality. There might also be a problem of omitted variables affecting the coefficients of the variables of interestFootnote 14 . To make the analysis more robust, the estimations in Table 3 have been repeated, but this time using instrumental variables. The results appear in Table 5. As instruments for the political regime (which, in this case, are three variables: democracy, dictatorship and universal male suffrage), I have used the percentage of the working-age population that has completed secondary education and the type of political regime (democracy, dictatorship and universal male suffrage) in other southern European countries: Italy, Greece and PortugalFootnote 15 . In column 1, I have instrumented simultaneously for the three variables relating to political regime (democracy, dictatorship and universal male suffrage). In columns 2 through 4, I have instrumented for each of these variables individually (the instrument used for democracy has been democracy in southern Europe and the completion rate for secondary education; for dictatorship, dictatorship in southern Europe and the completion rate for secondary education; and for male suffrage, completion rate for secondary education and male suffrage in southern Europe). In all of the regressions (from columns 1 to 4), a redundancy test has been applied. The instruments that did not pass the test were eliminated from the regressions.

TABLE 5 IV REGRESSIONS

Notes: Standard errors in brackets.

DWH=Durbin-Wu-Hausman.

***P<0.01, **P<0.05, *P<0.1 .

The reason for using these instruments is that the political and institutional context of other southern European countries is likely to have conditioned the evolution of the political regime in Spain, for example, through an imitation effect or diplomatic pressures. However, there is no apparent reason to assume that Spanish social spending had any impact on the political regime existing in other countries. Similarly, it is possible that demands for democratisation increase when the education levels of the adult population are higher. However, current social spending cannot have a significant influence on the current stock of education, which depends on decisions taken many years earlier. Nor is there any theoretical reason to expect that the political regime of a neighbouring country or growth in the stock of human capital per se will cause a rise or fall in social spending. As Table 5 shows, the instruments are reasonably strong. The first-stage F-statistic is above 10 in all equations. In equations [1] and [3], where the number of instruments exceeds the number of regressors, the P-values from the Sargan test are clearly ˃0.1, indicating that there is no evidence that the instruments are correlated with the error term.

Regarding the results, the size and sign of the coefficients of the variables of interest are similar to those in Table 3. Democracy has a positive and highly significant effect on social spending; universal male suffrage (in a not fully democratic context) has an initially negative effect that becomes easily offset by the socialist party’s parliamentary seats, and dictatorship has no statistically significant effect. The IV results, therefore, confirm Table 3’s results. Indeed, according to the Durbin-Wu-Hausman endogeneity test, there is no evidence to reject the null hypothesis that the regressors are exogenous. This is not entirely surprising. As noted earlier, high and low social spending levels occurred both under democratic and non-democratic regimes.

Political Regime and Long-Term Trends

The analysis presented so far (based on dummy variables) captures the «average» impact of each political regime, once we control for a set control variables. However, when one looks at the long-run evolution of social spending, one does not see a steady trend with (more or less abrupt) step changes associated with changes in the political regime. Instead, in the Spanish case one can observe two clearly differentiated patterns or social spending regimes, along with a long transition process between them (Figure 1). The first regime, which could be called the traditional regime, is characterised by low social spending, and covers the period between 1850 and the 1930s. The second regime, or modern regime, extends from the 1970s to the present day and is characterised by high social spending. This long-term pattern is partly determined by the cumulative nature of social policy. In Spain, as in many European countries, the growth in social spending is explained by the gradual introduction of new social programmes, often in a piecemeal way. Also, in countries like Spain where the development of social policy was based on the creation of Bismarckian social insurance schemes, initial social programmes were often limited to certain segments of the population, typically low- and medium-income industrial workers. Therefore, the growth in social spending can also be explained by the gradual expansion of coverage to the entire population and by the improved generosity of social benefits.

In Spain, however, the transition process from the traditional to the modern social spending regime was not linear, but went through periods of stagnation and of rapid growth. It is interesting to ask what impact the political regime had on this transition process. In this context one would expect the impact (if any) of the political regime to consist primarily of changes in the long-run growth trend and not so much of changes in levels. To test this possibility, the regressions in Table 3 have been repeated with the inclusion of a dummy variable (taking value 1 for the post-1931 period and 0 for the preceding years), and also a time-trend for the post-1931 period (which takes value 1 in 1931, increases linearly in the subsequent years, and takes value 0 prior to 1931). It should be recalled that 1931 saw the proclamation of the Second Republic, Spain’s first democratic regime. Therefore, the aim is to capture with these variables the potential change in trend and levels associated with the arrival of democracy. Together with these variables, a time-trend for the post-1931 period, squared, was also included. The reason for this is that one would expect the rate of growth to moderate once high levels of social spending have been achieved (i.e. once the transition from the traditional regime to the modern regime of social spending is complete). Lastly, to capture the effect of Franco’s dictatorship, the regressions also include the interaction between the years of dictatorship and the post-1931 dummy variable as well as the interaction between the variable dictatorship and the post-1931 trend.

The results appear in Table 6. Both the post-1931 dummy variable and the post-1931 time-trend have a positive and statistically significant effect. As one would expect, the square of the post-1931 time-trend, for its part, shows a negative and statistically significant sign. This suggests that the arrival of democracy in Spain not only entailed an increase in the levels of social spending, but also caused a change in its long-run trend, accelerating the growth rate of social spending. Subsequently, once high levels of social spending had been reached, the growth rate again levelled out. Regarding the role of dictatorship, the interaction between the years of dictatorship and the post-1931 dummy variable is not statistically significant. However, the interaction between the dictatorship and the post-1931 time-trend has a negative sign and is statistically significant. Rather than an abrupt return to the pre-1931 levels, the negative effect of the dictatorship consisted of reversing the acceleration in social spending initiated in 1931. In other words, Franco’s dictatorship halted the modernisation process (the transition from the traditional regime to the modern regime of social spending) that began with the arrival of democracy in 1931.

TABLE 6 SOCIAL SPENDING LONG-TERM TRENDS (1850-2000)

Notes: Standard errors in brackets.

OLS=ordinary least squares; DOLS=dynamic least squares; FMOLS=fully modified least squares.

***P<0.01, **P<0.05, *P<0.1.

This, in turn, suggests that the best way to analyse the impact of the political regime does not always involve analysing the changes occurring in the years immediately before or after a regime change. As has been shown, the effect can be more gradual than an abrupt step change. Guillén (Reference Guillén1992), for instance, found that, although «these regime changes would lead one to expect radical discontinuities» (p. 119), «the most salient feature of social policy during the Spanish transition to democracy was its high degree of continuity» (p. 137). By taking a broader perspective, however, one can appreciate the effect of the political regime much better.

6. CONCLUSIONS

Although the role of political factors has sometimes been denied, this paper shows that democracy in Spain had a clearly positive effect on both the level of social spending and its long-term trend. The arrival of democracy in 1931 led to a modernisation process involving a shift from a traditional regime (of low social spending) to a modern regime (with high social spending). This process, however, was interrupted by Franco’s dictatorship, which reversed this change in trend, slowing the ultimate growth in social spending. Democratic and non-democratic regimes are not invariant across time. Democracy today is different from democracy in 1931 and Franco’s dictatorship in 1975 was different from what it had been in 1945. However, we can define some minimal aspects to consider a political regime as democratic or not over time. It makes sense to ask whether these minimal aspects are relevant for social spending or not; the results indicate that they are. Democracy can, indeed, explain a substantial variation in social spending (4.5 per cent to 6 per cent of GDP, depending on the regression we take as a reference). This does not mean, however, that the political regime impact is limited to social spending. It could also have an impact on other aspects of social policyFootnote 16 , but these are beyond the scope of this paper. Similarly, this does not mean that the political regime can explain the whole variation in social spending. There are many other factors in play. Here, I have controlled for some of them, but there may also be omitted variables. To deal with the potential issue of omitted variables an IV analysis has been undertaken (using secondary school completion and the political regime in southern Europe as instruments for the Spanish political regime). The IV results confirm democracy’s positive effect.

This paper also shows other interesting nuances about the role of political factors. Political instability during the years of dictatorship gave rise to modest increases in social spending, although they were entirely insufficient to offset the negative effect of dictatorships. Meanwhile, the introduction of universal male suffrage in the late 19th century (in a context of caciquismo and widespread electoral fraud) had no positive effect on social spending. What did have a positive effect, by contrast, was the weak electoral growth of social democracy (and more generally the growth of the labour movement and social unrest) in this same non-democratic context. The political elite of the Bourbon Restoration were, at least partly, reacting to demands from below, although social spending remained very low throughout the entire period. During the years of democracy, by contrast, left-wing governments had no significant effect on social spending (with the exception perhaps of the 1930s). This is explained partly by the effect of democracy per se (which obliged all parties to take into account the preferences of all citizens), but also by the emergence of the Keynesian consensus (whose Spanish equivalent were the 1977 Moncloa Pacts). Curiously, the role of left-wing parties was more visible in the 1930s (prior to the Keynesian consensus) and in the Bourbon Restoration (when the preferences of low-income groups were systematically ignored).

APPENDIX

FIGURE A1 SPANISH PUBLIC SOCIAL SPENDING (PER CENT OF GDP), 1850-2000 Source: see Figure 1.