The persistent vulnerability of major financial institutions to rogue trading is clear from the repeated episodes of this form of fraud, particularly since the globalization of the 1990s. This article examines a scandal from 1974, when Lloyds Bank suffered the largest loss to date of any British bank by a single speculator. It shows how the cozy relationship between bankers and their regulators that had developed behind capital controls and uncompetitive markets was challenged by the collapse of the pegged exchange-rate system, acceleration of international financial innovation, inflation, and a heady atmosphere of internationalization. Increased competition prompted aggressive expansion into new markets by managers inexperienced in assessing both market and operational risk and thus vulnerable to a mismatch between the norms of banking in Switzerland and those in the City of London.

By rogue trading we mean a particular type of operational failure that arises when a trader hides large losses from managers by illegally evading disclosure regulations. Several special characteristics distinguish rogue trading from other forms of fraud where the initial intention is to steal from the company or its customers.Footnote 1 First, it is revealed only when the losses reach a point where they can no longer be concealed, so it is difficult to gauge how prevalent this behavior is. Secondly, the motivation is not always primarily personal financial gain, but rather the protection of reputation, which raises issues about the norms of financial markets.

Rogue traders have been variously depicted as charismatic heroes, aberrations in an otherwise well-functioning market, and the products of systemic biases that promote or condone their actions.Footnote 2 The legal and economic literature focuses on internal supervisory and compliance mechanisms, while social or psychosocial perspectives focus on personal incentives for individual staff to achieve high profits. Given the probability of “successful” rogues creating profits by taking risks, incentives such as bonuses may encourage norms where some transgression of rules is acceptable. As Mark Wexler notes, “There has not been a case where a trader has been labelled a rogue when making money for the firm.”Footnote 3 Rogue trading can therefore be portrayed as an operational risk arising from a rational response to incentives in banks and financial firms that encourage employees to engage in bounded risky behavior to maximize profits.

Most financial institutions have clear rules to monitor traders, but the costs of completely preventing low-frequency but high-cost losses generated by a single individual may be greater than the extra profits gained through “lucky” trading facilitated by norms that encourage risky behavior.Footnote 4 Firms may also seek to keep such episodes secret to avoid fines or loss of reputation; an industry that relies on trust may have an incentive to restrict transparency. The responsibility for illegal behavior, when exposed, is shared among the bank as a legal entity, the board of directors as a collective group, line managers, and the individual trader. How this responsibility is distributed has particular importance for the subsequent development of governance structures and moral hazard. We will see that in the Lloyds case, the board of directors accepted no responsibility—and indeed were rewarded.

Beyond economic motives, there are psychological and biological models of risky trading. John Coates and Joe Herbert note the effects of adrenaline and hormonal changes that affect behavior in highly pressured work environments, particularly among young men.Footnote 5 These psychological and gender factors are evident even in the early days of liberalized markets. In September 1974, when the Lloyds scandal was revealed, the Sunday Times profiled Midland Bank's trading room as a place where foreign exchange was “a youngish man's game” and traders “talk of the camaraderie of the business, of the satisfaction of belonging to a select fraternity,” capturing large salaries compared to other departments, but also prone to corruption.Footnote 6 Behavioral economics demonstrates how postponing the acceptance of losses can lead traders to escalating behavior through serial decision-making, which can push them to break the rules.Footnote 7 Also, perception bias in managers may lead them to overlook reality if they have a strong incentive to believe the “myth” presented by the trader. As an operational risk, rogue trading is commonly blamed on inadequate supervision and compliance that allows the “rogue” to break the rules, but the case in Lugano Switzerland in 1974 also demonstrates the importance of the market environment for excessive risk-taking. Thus, operational risk is closely linked to market risk.

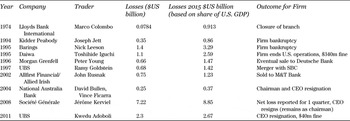

For reference, Table 1 shows some major rogue trading episodes, their value, and their outcomes. In the 1990s most firms were bankrupted or merged and in the 2000s senior executives were dismissed in recognition of their ultimate responsibility for compliance failures. The Lloyds Bank losses in 1974 were at the lower end of comparable rogue trading scandals, and senior executives were not affected.

Table 1 Major Foreign Exchange and Bond-Trading Fraud Episodes

Sources: Amy Poster and Elizabeth Southworth, “Lessons Not Learned: The Role of Operational Risk in Rogue Trading,” Risk Professional, June 2012, 21–26; Samuel H. Williamson, “Seven Ways to Compute the Relative Value of a U.S. Dollar Amount, 1774 to Present,” Measuring Worth, accessed 10 Mar. 2017, https:// www.measuringworth.com/.

Anatomy of the Fraud

Lloyds Bank had a strong national and international reputation in 1974, with a total balance sheet of £4.6 billion. It was the smallest of the four major clearing banks in London—about two-thirds the size of Barclays, half that of Midland, and one-third that of NatWest.Footnote 8 Founded in 1765, Lloyds Bank acquired its first international office, in Paris, in 1911 and grew quickly in the twentieth century through acquisitions. In 1971 the bank's international operations were consolidated by merging two subsidiaries (Bank of London and South America (BOLSA) and Lloyds Bank Europe) to form what later became known as Lloyds Bank International (LBI) in 1974. In 1969, Lloyds Bank commissioned William Clarke, a financial journalist, to review its international position. Clarke advised the board that their bank was on the brink of being left behind in the new global financial environment: “Lloyds Bank Europe [LBE] has perhaps one year, or at most two years, in which to carve out a substantial, profitable place in international banking for itself.”Footnote 9 He urged the bank to think less like a traditional clearing bank and to engage more in wholesale, commercial, and foreign-exchange trading, pointing to the success of the bank's new Zurich branch in increasing and diversifying the international banking services it offered.Footnote 10 Clarke's vision included appointing local managers “who have had intensive experience in the new kind of international finance: foreign exchange, Euro-currency business, new Euro-bond issues, advice to companies and on mergers. . . . They must be able to build up a foreign exchange and interest arbitrage operation ‘out of nothing’ and make it profitable . . . and altogether go out actively to get business, rather than wait for it to come.”Footnote 11 E. S. Tibbetts, general manager of LBE, agreed with the general thrust of the report, particularly the need to recruit more staff and improve training, noting that “original thought is at present confined very largely to London and Zurich.”Footnote 12

Three Swiss branches of LBE (Zurich, Geneva, and Lugano) were overseen locally by the Geneva branch. The Lugano office, opened on May 19, 1970, remained small, with 16 employees, compared with 230 in Geneva and 100 in Zurich. Located twenty miles from the Italian border, the branch was meant to provide services mainly for Italian “refugee” funds and to form a vanguard “should we eventually decide to commence a banking operation within Italy.”Footnote 13 High taxes and political instability made deposits and investment advice across the border attractive to high-value customers in Milan, and the branch initially attracted funds successfully and generated fee-based income through advisory and management services to personal customers. But the basis of the branch's activities would soon be transformed by the collapse of the Bretton Woods system in 1971–1973.

In August 1971, U.S. President Richard Nixon suspended the convertibility of the dollar to gold and challenged Japan and West Germany to revalue their currencies against the dollar in order to take pressure off the U.S. balance of payments; otherwise, the United States would retreat behind protective tariffs. Following a few months of hasty negotiations, a new framework of pegged exchange rates was established at the end of the year, but this solution proved only temporary. In June 1972, sterling abandoned the pegged exchange-rate system, and most other currencies had floated free from their U.S. dollar pegs by March 1973, leading to a much more risky environment for foreign-exchange trading. Suddenly, profits could be earned through exchange trading on the bank's own books as well as on behalf of customers—but at the same time, the market risks of this trading increased sharply.

This new environment for international finance posed particular challenges when the old guard from the 1930s was retiring and banks employed a generation of foreign-exchange traders with no experience of floating rates. George Bolton, a Bank of England manager and chairman of BOLSA, was a key expert in foreign-exchange markets from the last era of floating rates, in the 1930s, and he was on the management board of LBI.Footnote 14 But he turned seventy in October 1970, the usual retirement age under LBI's company rules. Bolton was reelected to the LBI board, but he was not on the chairman's committee that reviewed foreign-exchange operations reports.

At about 5:00 p.m. on August 6, 1974, Robert Gras, chief foreign-exchange manager at LBI in London, received a phone call from a friend at the Paris office of Crédit Lyonnais warning him that the LBI's Lugano branch had accumulated large amounts of outstanding foreign-exchange operations with various branches of Crédit Lyonnais. This had come to the caller's attention because of an unusual simultaneous collection of paperwork from these branches after a period of staff strikes.Footnote 15 Kurt Senft, general manager of the Swiss offices, went to Lugano the next day to investigate; on August 8 he was joined by three LBI staff from London head office, including Gras and Erich Whittle, head of LBI's European offices. When questioned, the dealer, Marc Colombo—a Swiss national who, at twenty-eight, was the same age as Nick Leeson of Barings and two years younger than Jérôme Kerviel at Société Générale—reported losses of about 100 million Swiss francs (SF). This initial estimate turned out to be only 45 percent of the eventual total loss, SF 222.3 million, an amount that was larger than the capital of the three Swiss branches altogether. Whittle and Gras took Colombo and Egidio Mombelli (the branch manager) back to London on the weekend of August 10 and 11 to determine the extent of the losses and the amount of outstanding forward contracts. On Monday, August 12, the Bank of England and then the Swiss National Bank and the Swiss Federal Banking Commission were alerted to losses worth about £33 million.Footnote 16

Colombo had joined LBI in March 1973, to start foreign-exchange trading along with two junior clerks, just as the Bretton Woods pegged exchange-rate regime collapsed. He had experience at Hill Samuel and Co. in London as junior dealer and had spent eighteen months as “second foreign exchange man” at Worms Bank in Geneva.Footnote 17 In December 1973, the LBI head office set a maximum open overnight position of SF 5 million for the Lugano office, but Colombo ignored the limit because “members of the management, at high managerial level, . . . cannot possibly understand fully how things take place and, consequently, they do not realize the meaning of the limitations imposed upon our activities” as “foreign exchange men.”Footnote 18 He found the limit “too small viz a viz [sic] the actual work carried out by us as foreign exchange men.” Some arrogance is displayed here alongside pride in the title of “foreign exchange man”; Colombo claimed that he had remained at the bank to try to recover his losses “because—as is in fact typical among our particular category of foreign exchange men—professional pride had been hurt.”Footnote 19 His operations included spot transactions as well as definite term operations (called “outrights”), forward contracts of up to six months, and swaps with other banks. When he ran into difficulties covering his losses, he hid copies of the forward exchange contracts in a box rather than passing them through the branch accounts and made false entries to the accounts sent by the branch to head office. The branch manager countersigned vouchers and reports without checking them.Footnote 20

Colombo's first large transaction was in the summer of 1973: a spot purchase of US$34 million against Swiss francs for resale in a forward swap for settlement in twelve months. He then covered this with a reverse transaction, selling the $34 million to purchase it back on a swap basis each month. Colombo planned to generate a net profit based on the spread between the twelve-month and one-month swap rates, and for a time he reported a profit of SF 170,000 per month (SF 170,000 per month notional loss on the twelve-month swap and SF 340,000 profit on the monthly deal). But in November 1973 the dollar depreciated, leading to losses on both sides of the operation totaling SF 320,000 per month. Colombo, now believing the dollar to be overvalued, sold the $34 million spot with the intention to repurchase it at a lower rate in a month's time and thus make good his earlier losses. But in January 1974 the dollar appreciated sharply, and he quickly repurchased the $34 million at a rate of SF 3.28 to the dollar, having sold in November at SF 3.14 to the dollar, leading to losses of SF 7 million. Although he anticipated being dismissed from the bank if this loss was discovered, Colombo was confident he would be able to secure a position with another bank as a dynamic trader. He hid the losses because of damage to his pride, not for job security. After a week he was convinced that the dollar would continue to appreciate, so he recklessly bought $50 million against Swiss francs and $50 million against deutsche marks at a term due in March/April 1974. However, having again guessed wrong on the dollar exchange rate, Colombo's trades led to accumulated losses of SF 50 million. In his own words, “At this stage it was no longer a question of pride but simply a question of finding myself bound by facts,” but he still did not alert his employers. He claimed that he was aware of cases in Lloyds branches in Rio de Janeiro and Madrid where losses of SF 20 million had been discovered and, as a result, the dealers were “completely excluded from the profession,” prompting the Brazilian dealer to commit suicide. Colombo later testified that the threat to his career, even if he were not prosecuted, meant that “I considered myself as being bound as a result of what had happened and I could not see any other way out but to remain at my own post and endeavour to recover the loss by means of subsequent operations.” As losses escalated, so too did the risks, and he ended up with an open position for $550 million, having started with a purchase of $34 million less than a year earlier. Rather forlornly, he said that “having started on this path, I was unable to change course.”Footnote 21

In his testimony to the Lugano magistrate, Colombo described six methods he had used to “camouflage” the losses and the exchange positions.Footnote 22 When asked if he knew of other banks that did these kinds of transactions, he remarked that “it is clear that I lack the genius to have been the inventor of such refined methods of camouflage all on my own.”Footnote 23 From March 1974 he had recorded outright purchases of foreign currency as outstanding swaps, thereby avoiding or delaying reports of losses in the daily accounts: “This we call ‘keeping a slip in the drawer,’” he testified.Footnote 24 He clearly felt part of a community of foreign-exchange men who acted according to norms they had set themselves.

Colombo's transactions were spread across a wide range of international banks in Switzerland, London, Luxembourg, Frankfurt, and Cologne, although most were with Swiss banks. Table 2 shows outstanding forward contracts against deutsche marks and Swiss francs as of August 12, 1974. The total was almost $560 million, 60 percent of which was against deutsche marks, dating from October 10, 1973. Over time, the pace of Colombo's trading increased and the terms shortened; by February 1974 he had begun six-month deals, setting up twenty-seven operations in April 1974 with settlement dates in October and peaking at forty-five three-month trades during July, all of which were due to mature in October.Footnote 25 This was taking place exactly at the time of increasing volatility in the dollar exchange rate.

Table 2 Summary of Outstanding Forward Contracts at August 12, 1974 (millions)

Source: William Taggert (interim general manager of LBI for Switzerland), testimony before public Prosecutor for the Jurisdication of Sottocenerina, 9 Sept. 1974, 7004, LGA. There was an additional contract sale of US$1.28 million against FF 6.1458 at a rate of 4.80375 with Credit Industriel et Commercial, London.

Notes: DM = deutsche marks; FF = French francs; SF = Swiss francs; USD = U.S. dollars.

There is little evidence that Colombo benefited financially from the rogue trading itself. Mombelli, the branch manager, noted that Colombo was not eligible for performance bonuses, nor was he competing for status with other traders.Footnote 26 He was offered and accepted a personal refund of 20 percent of the commission fee paid by LBI to FINEX S.A. of Zurich, amounting to SF 30,000, but he had confessed and signed it over to LBI while he was in London being questioned.Footnote 27 At the time, Colombo's salary was SF 4,500 per month, so this sum was more than six months’ salary. The kickback was not an integral part of covering his losses, although it does show his propensity to break rules.Footnote 28 He argued that this kickback had taken no funds away from the bank, since LBI would have had to pay the full commission even if Colombo did not accept the money.

In the end, the episode was an embarrassment rather than a financial disaster. The trading losses were about the equivalent of £33.5 million, or two-thirds of LBI's authorized capital, but the Lloyds Group had assets of over £500 million and pretax profits of £77 million in the first half of 1974, so the losses were easily recovered.Footnote 29 Moreover, the actual losses were mitigated by insurance and tax provisions. LBI had a banker's blanket policy that insured against criminal acts by employees, covering the group for up to £6 million for “each and every loss.” They had thus priced the operational risk rather too modestly. Since there was a danger that Colombo and Mombelli might be acquitted or that LBI might be deemed to have contributed to the loss through its own negligence, the board quickly accepted £5 million offered by the insurance company. Additionally, LBI could claim U.K. tax relief (at 52 percent) against £23 million of the total gross loss of £33.5 million.Footnote 30 The board also increased LBI's authorized capital from £50 million to £75 million immediately.Footnote 31

Although neither financially ruinous nor systemically contagious, the case was widely covered in the business press, including lurid details of Colombo's villa and sneering accounts of the supervisory shambles in the Lugano office. All of this reflected badly on the governance provided by London head office and the local Geneva office.

Checks and Balances

During 1972, LBI's head office in London compiled a rule book for use by all branches overseas. This resource, which covered the full range of operating procedures, was to replace the previous BOLSA and LBE rule books and was sent to the Swiss branches in January 1973, before Colombo arrived at Lugano. Mombelli claimed that because there was virtually no foreign-exchange trading at his branch at the time, he “didn't bother to read that section about the dealer” and so did not realize there was supposed to be a daily dealer's book recording all transactions.Footnote 32 The gap between the LBI rule book and compliance was at the heart of the supervisory failure; perversely, in this case the complex rules-based system reduced the likelihood of effective compliance and enforcement.

Head office delegated operational responsibility for supervision of Swiss branches to the Geneva office, where Senft was the general manager. Colombo was trained for two weeks at the Geneva branch when he joined the bank in 1973. Senft inspected the Lugano branch in March of that year, when Colombo began his employment, but not subsequently.Footnote 33 Geneva received monthly and quarterly reports from all Swiss branches and used these to compile its reports for the Swiss National Bank. LBI head office also sent staff out periodically for spot inspections that included the foreign-exchange operations, but they neglected the Lugano branch in March 1973 because trading there was minimal. This proved an important oversight that may have given Colombo greater confidence in his ability to conceal losses until they could be reversed. In September 1974 (a month after the Colombo case broke) a case of “mismanagement and irregularities” in the investment portfolio operations at the Zurich branch was uncovered, and a portfolio manager at Zurich resigned, so Senft's supervisory myopia extended beyond Lugano to Zurich.Footnote 34 The Geneva office came in for considerable criticism from London for not ensuring that the LBI rules were followed at Lugano, but clearly head office had also failed to perceive a problem.

Within the Lugano branch, the manager was responsible for supervising the full range of activity: initialing each trading slip, checking the accounts daily, initialing all incoming letters of confirmation from correspondent banks, and signing off on the monthly accounts sent to the Geneva office. The costs, in terms of time and training, of making this procedure effective turned out to be excessive, and Mombelli admitted that he had initialed trading slips and accounts without checking that they were valid.Footnote 35 He claimed to “well remember having sent to Colombo at least three memorandums, possibly four, with which I ordered him to reduce the extent of his operations,” but still, discovering the losses was “like lightning in a clear blue sky.”Footnote 36 Partly, this surprise arose because Mombelli had not instructed Colombo to keep a dealer's book to be checked at the end of each day, as was the practice in Zurich and Geneva. Exchange inspections by LBI head office were carried out at these larger branches in March 1973, but not at Lugano “because it was supposed to be dealing in a very small way,” according to Francis Paveley of LBI London, who wrote the report for the Swiss Federal Banking Commission.Footnote 37 In fact, Lugano was trading at a much larger scale than either Zurich or Geneva. Mombelli lacked the competency to understand the transactions he was approving, and he relied heavily on Colombo's expertise in the complexities of foreign-exchange trading. Mombelli was clearly a key source of prudential failure, but his errors should have been caught at the Geneva office through their direct inspection and enforcement of the rule book. Mombelli later claimed that he had no personal experience with foreign-exchange dealing and was not familiar with the Hilfsbucher (“Book of Rules”) sent by head office, which he had not had time to read carefully. Nor had he taken time to read other instructions from head office.Footnote 38 Moreover, although Mombelli had signed off on falsified transactions, he testified, “I presume that one does not expect any Bank Manager to check each and every document which is put before him for initialling. It is instead usual for the Manager to carry out the so-called ‘Stichproben’ (random inspections).”Footnote 39 Given that the branch comprised only sixteen staff, Mombelli's claims of pressures on his time appeared exaggerated to LBI staff in London. Paveley, of head office, testified that “in a branch of that size, the manager could have known exactly what was happening. . . . Possibly M. did not grasp the significance of the amounts involved, but he thought that they were doing big business, making a lot of money[,] and was speaking of taking another floor in the building.”Footnote 40 Clearly, the combination of time pressures and a lack of expertise had led Mombelli to trust Colombo excessively in the summer of 1974. His failure to query the incoming letters of confirmation from correspondent banks that described very large transactions subsequently prompted changes to the internal controls within LBI.

Colombo (in his own defense) also blamed Mombelli: “I have been a bank exchange dealer for 5 years and have never had so little supervision by a management. I might rather say that at Lloyds Lugano there existed no supervision. In fact, had Monsieur Mombelli done his work, which consisted in the supervision of his staff, he would have realised the real position of his Branch.”Footnote 41 While public testimony might be self-serving, the evidence clearly shows the slippage between London and Switzerland and the failure of internal systems within Switzerland to enforce the rules set centrally. It is clear that LBI London considered Mombelli complicit, either deliberately—by ignoring or by tolerating Colombo's behavior in the expectation that it would generate branch profits and an expansion of his branch—or implicitly, by not educating himself in the complexities of the deals undertaken by his staff. But the issues of compliance extended well beyond any individual failings by Mombelli.

The bank's internal analysis of the scandal was critical of the quality of personnel as well as the operational weaknesses in supervision and accountability at LBI's Swiss branches. Importantly, it became clear that Colombo was not a unique rogue. The bank's chief inspector reported that Swiss visa restrictions made it difficult to find enough qualified staff, so that LBI was required “to fill a substantial proportion of executive vacancies simply by hiring people off the street” rather than promoting trusted, long-serving staff “whose honesty is virtually beyond question.”Footnote 42 He also emphasized how the norms of Swiss banking conflicted with a culture of adherence to formal rules:

The business of our Swiss Branches involving as it does, tax avoidance by customers domiciled abroad, implies numbered accounts, “keep mail” facilities, agreement not to communicate in writing with customers and a tendency to rely on customers’ verbal instructions by telephone. This type of secret, undercover, business clearly leaves wide loopholes for the dishonest executive to manipulate customers’ funds for his own benefit.Footnote 43

The report recommended that “a proper system of reporting to London must be set up—lack of this was a substantial contributory cause of the Lugano affair.” The chief inspector discounted the obstacle of Swiss banking secrecy, noting that so long as the information was not used “for control purposes” (i.e., by British regulatory authorities), the information could cross borders. With regard to banking norms, the report described complicated evasion practices whereby

a substantial proportion of the business of Swiss Branches is routed to Panamanian subsidiaries thus by-passing Swiss lending ceilings and avoiding Swiss profits tax. The subsidiaries are Panamanian in name only and all work relating to them is effected in our own Branches in Switzerland by our own bank staff. Millions of dollars in profits are involved—were we to be required by the Swiss authorities to cover back profits tax stretching over a number of years (and there is no question that, under Swiss law, we are liable) it is not at all clear that we could now offset against UK taxes. Of course for a small Swiss bank, operating through a Panamanian “suitcase” company might be rather clever always provided one does not get caught. For the Branch of a large international bank to involve itself in this kind of thing makes no sense at all—the loans concerned could equally well be carried on the books of London or on those of one of the many other vehicles available to us outside Switzerland.Footnote 44

Indeed, the Swiss banking environment was prone to scandal. In March 1977 an internal investigation revealed that staff at Credit Suisse's Chiasso office (also near the Italian border) had illegally transferred capital from Italy on behalf of customers to evade taxes, using a holding company in Liechtenstein, Texon Finanzanstalt, run from within the Chiasso branch. Credit Suisse had to bear financial losses of SF 2 billion ($830 million).Footnote 45 The subsequent trial concluded that this illegal activity had been concealed from head office for sixteen years. The Chiasso scandal prompted the Swiss Bankers Association to adopt a code of conduct on acceptance of suspicious funds and challenged the formal Swiss secrecy laws for banking.

The internal inspection concluded that LBI's Geneva branch was the most robust, although there were still difficulties there. The March 1973 inspection report was highly critical, particularly of the department heads and their acceptance of responsibility. In the November 1974 inspection, it was noted that “it is pleasing to report that good progress in the right direction is being made” although more training was required because “it is not enough to provide them with excerpts of the Book and expect them to ‘get on’ with it. The Rules have to be discussed and the underlying reasons explained where necessary.”Footnote 46 Compliance was clearly at the root of the problems at LBI. The penalties for not following the rules were not clear, and widespread evasion even at senior level confirmed that local norms overrode the rule book.

The chief inspector recommended that “one must bear in mind . . . the emphasis which—following on the merger—was put on profits at any prices, presumably as a result of the McKinsey inspired ideas which were then current. A substantial expansion in business—particularly in exchange dealing for the Bank's own account—was undertaken at Swiss Branches without any proper strengthening of the administrative framework.”Footnote 47 The Lugano fraud was not an accident, but a result of the rush to expand the bank's operations in the face of opportunity and competition, and a failure of human resource management in a labor market with a shortage of qualified staff.

The evidence from legal testimony and from the bank's internal investigation portrays a catalog of errors and mismanagement at each level of the bank, from Colombo to the London head office. The legal testimony is at times contradictory, taking into account the many interviews of the main protagonists, and contains clearly self-interested efforts to shift blame to other parties. The archival evidence reveals the range of errors and mistakes as well as the attitudes of the individuals concerned. After embarking on a rapid expansion at the start of the 1970s, the London board was complacent about the degree of compliance with their rules and norms among newly recruited overseas staff at a physical and psychic distance from London, where they operated in a very different and often secretive banking environment.

Internal Response

Mombelli was sentenced in October 1975 to six months for “disloyal administration” and Colombo to eighteen months for the same charge plus “falsification of documents,” although both prison sentences were suspended. Outside court, Colombo reportedly stated, “I hope to find another job in the same field—this trial was good publicity,” although there is no trace of his subsequent career.Footnote 48 The Lugano submanager was given six months’ notice to resign. Senft, the Geneva chief manager, resigned at the end of October (but was paid for the next three months). The manager and the legal adviser at Zurich followed suit in January 1975. After a subsequent inspection of all Swiss branches, more staff in Zurich were “found unsuitable,” including an investment portfolio manager and two foreign-exchange dealers.Footnote 49 The portfolio manager and the junior exchange dealer were allowed to resign but the senior exchange dealer, “who was fairly well known in banking circles in Switzerland,” was dismissed without compensation on October 18 since his was “a more serious case.”Footnote 50 The portfolio manager was responsible for losses of about SF 4 million, compared with Colombo's SF 222 million. As the penalty for being caught breaking the rules, some Swiss staff lost their jobs, but perhaps not their reputations.

At head office, by contrast, no heads rolled. The board of LBI was formally told at its regular meeting on August 28, 1974, that total losses were expected to be £33 million and that the Lloyds Bank board had agreed to underwrite the losses, with the approval of the Bank of England.Footnote 51 At the same meeting, new branches in Cairo and Guatemala were approved, so the episode did not affect the expansion of LBI's activities into physically and culturally distant markets. At a meeting of the vice chairman's committee there was a fuller discussion; the committee concluded, rather mildly, that because “many managers had little knowledge of the mechanics of exchange operations, a memorandum should be given to every branch manager with an exchange department setting out the points they should have in mind in controlling these operations.”Footnote 52

At the time of the LBI scandal, the structure of Lloyds Bank Group was under review, and the outcome is surprising. After the full acquisition of the share capital of LBI and Lloyds Bank California, it was agreed in September 1974—while the scandal was under investigation—to transfer all international activities (other than Grindleys and Lloyds Bank's own overseas department) to the responsibility of the LBI board. This decision ignored the recent lapse of oversight that had embroiled the bank in a costly and embarrassing scandal. Despite the events of August, LBI took over control and utilization of resources and supervision of subsidiary banks, including credit risks and exposure.Footnote 53 LBI would also direct the group's public relations, “recruitment, training and career development of personnel at home and overseas” and approve expansion into new territories. K. R. M. Carlisle tendered his resignation “consequent upon these arrangements,” and Lord Lloyd (chairman of the National Bank of New Zealand) and Stafford R. Grady (chairman of Lloyds Bank California) joined the LBI board. There was apparently no responsibility cast upon board members for the lapse in governance and, indeed, the board's powers in the group were considerably enhanced. This outcome contrasts with several cases, shown in Table 1, in which senior executives at head office resigned.

In December 1974 the Lloyds Group Committee met for the first time and investigated LBI's lending and trading practices. They “noted that LBI's present procedure did not provide for limiting the overall maximum commitment of any one customer or group of customers; individual executive directors had unlimited lending powers; and facilities were not reported to the Board.”Footnote 54 On currency dealing, the committee “noted the change in the pattern of dealing following the switch to floating exchange rates and acknowledged the consequent additional risk and volatile nature of the markets.” LBI itself undertook a study to reduce the number of dealing centers and consider overall policy in this area “with particular reference to methods of operation and control.” So the foreign-exchange operations of the LBI were not formally censured, despite the most costly lapse in governance in the bank's history. Nevertheless, new measures were taken to tighten up procedures.

In November 1975, the chief executive officer of LBI wrote to all general managers, chief managers, and senior managers, noting that “what happened in Lugano was not the first time that an executive of confidence has been able to feed vouchers and returns into the branch system with apparently the second signatory believing that his initial or signature was a mere formality carrying no responsibility. And, unfortunately, another case has occurred since the Lugano investigation.”Footnote 55 The problem was particularly acute when, “the human situation which arises in our smaller branches where executives work closely together day in and day out. I am also most concerned to keep a happy spirit of cooperation amongst executives throughout the Bank. Nevertheless, each executive has a loyalty which goes beyond that of his local senior and no executive should give his written assent to anything which either he does not understand or knows to be irregular.” The letter was not sent directly to foreign branch managers, to whom it was mainly aimed, but was sent to the functional officers in the London head office. In the meantime, more formal structural changes were made.

Partly in response to the Bank of England's request that U.K. banks reflect on the governance of foreign-exchange trading, LBI's operations were tightened in February 1975 into a more centralized hierarchy. Ultimate control was vested in the director of the Exchange and Money Market Division (EMMD), who had the authority to instruct any executive in any branch worldwide.Footnote 56 New York and London offices were appointed time zone branches, with overall jurisdiction for the Americas and Europe, respectively, and reporting to the EMMD. In an important new check, “correspondent banks will, in due course, be requested to send copies of branches’ nostro accounts to Exchange and Money Market Division, Head Office, London.” New York would forward copies of overseas branches’ nostro accounts to London every month, and daily movements in these accounts would be monitored by “all Chief Managers and Branch Managers.”Footnote 57 The confirmation letters from correspondent banks were meant to act as a further external check on the operations of individual dealers in case they managed to hide their trades from the daily accounts. In the Lugano case, the confirmation letters had arrived on the branch manager's desk and he had merely initialed them without further enquiry, despite the huge amounts they were reporting.

The Lugano branch never recovered from the debacle of 1974. After accumulating operating profits totaling SF 1.2 million for the two years ending in September 1973, the branch moved into sustained losses.Footnote 58 The exchange loss in 1974 was followed by operating losses in the following two years totaling SF 1.1 million. Customer deposits fell by 45 percent the year after the scandal and never recovered. In August 1976 the LBI board noted that “Lugano no longer offers attractions as a domestic banking centre and it is unlikely that our branch there will ever be profitable.”Footnote 59 The Swiss National Bank, when approached for its views on LBI closing the branch, “indicated that it would not object.”Footnote 60 In April 1977 the board decided to close the Lugano branch because its core cross-border business with Italy had dried up, due to tighter legislative controls in Italy from 1976, and because “local financial scandals additionally have lowered the image of Lugano as a financial centre.” Moreover, Lloyds refused “to participate in the illicit transfer of funds from Italy, a practice which many of our competitors undertake.”Footnote 61 Thus ended LBI's rather inglorious adventure in Lugano.

While the scandal had important implications for LBI, these tended to be transitory rather than transformative. In contrast, the impact on British supervisory procedures was out of proportion to the size and systemic effect of the scandal in the U.K. banking system. The rogue trading episode exposed stark differences in attitude to the regulation and supervision of international banking between the Bank of England and the Treasury and prompted more fundamental changes at both a national and international level.

External Response

The deputy governor of the Bank of England, Jasper Hollom, was initially advised by the Lloyds London office that substantial losses had been identified at the Lugano branch, over the weekend of August 10–11, 1974. Douglas Wass, permanent secretary to the Treasury, was informed the following Monday.Footnote 62 At first, Hollom and LBI officers believed that the losses “might be hushed up.” The Treasury secretary Douglas Wass disagreed, but disclosure was delayed and journalists were kept at bay after appeals from the Swiss National Bank for continued secrecy while they completed their own investigation.Footnote 63 The Treasury was very frustrated by the Bank of England's complacent attitude. Hollom casually remarked that there was probably no way to have caught a rogue dealer's speculation in time, although he admitted that the branch manager might bear some responsibility. His initial reaction was that there was no cause to change any policies or practices. Financial secretary Derek Mitchell, in contrast, argued that “no organization with any pretentions to efficiency could accept a situation in which a loss of this magnitude was possible. Lloyds would have to do something if only to arrange that in future dealers worked in pairs.”Footnote 64 Mitchell concluded that “we can have no confidence that this matter will be handled effectively by Lloyds but I hesitate to suggest that we should involve ourselves more directly lest any of the mud that may fly around sticks in the wrong place.” For the financial secretary, avoiding any semblance of responsibility prevailed over forcing Lloyds to take quick action.

Others were more forthright about the potential reputational risk if it was discovered that the Bank or the Treasury had colluded with Lloyds in withholding important market information. On August 29 (two weeks after the Bank of England was made aware of the losses) the Chancellor of the Exchequer asked the Bank of England to approach Lloyds again to urge public disclosure.Footnote 65 Lloyds claimed that the Swiss authorities wanted to wait until they were assured that all losses had been identified, and Lloyds hoped to delay an announcement until its normal third-quarter report in October—if it had not already been leaked to the press.Footnote 66 In fact, the Swiss press threatened to publish the story and so the losses (and the fact that they had already been recovered) were announced on September 2, 1974, almost a month after the fraud had been discovered.

At the Bank of England, the Lugano debacle initiated a debate over how to deal with overseas branches of U.K. banks. John L. Sangster noted that “prima facie the losses sustained by the LBI branch in Lugano suggest that we first turn to the foreign exchange area and impose some sort of reporting and possibly limits akin to those that we impose on banks in the UK.”Footnote 67 But he pointed out that controls on foreign exchange dealing were not prudential—rather, they were designed to protect the foreign-exchange reserves from interest arbitrage or long positions—so they were only monitored against sterling (not other currencies). The limits were thus a tool of exchange control related to the balance of payments, not a means of monitoring risky behavior by individual institutions. The Bank of England set formal daily limits and could make spot checks at any time, but reports of overall positions were usually examined weekly with more detailed reports only monthly. The basic limits were £50,000 combined spot and forward open positions, and a further £100,000 in spot foreign assets could be held against forward sales of foreign currency, although some banks were given larger limits (mainly multinationals and clearers). The Bank of England reported that “we very rarely find that a bank has a position exceeding £10 million in any one currency, and make enquiries when this occurs.”Footnote 68 By way of comparison, the small LBI office in Lugano had accumulated an open position of $560 million by August 1974.

Sangster wondered, “Do we then just shrug our shoulders at the losses incurred by LBI Lugano? There is sometimes a management advantage in not overloading administrative procedures by over-reacting to a single instance of loss. But there is a problem in the LBI Lugano area which we have to probe, perhaps to satisfy our own misgivings and certainly to satisfy the paternalistic instincts of HMT.”Footnote 69 The problem was whether the geographic and cultural distance from normal U.K. practice “mean that foreign branches have much more autonomy and scope for error and adventure” and whether they are therefore adequately supervised by their parent home office. This observation shows tacit acceptance that the Bank's prudential supervision of banks in London was based largely on local culture, moral suasion, and peer pressure that might not be effective in other banking centers.Footnote 70

Pressure from the Treasury, and a reluctant recognition that there may arise a gap in supervision, eventually prompted the Bank of England to draft a letter warning banks to exercise effective control over their branches both within and outside the United Kingdom, particularly since the foreign-exchange positions of branches and subsidiaries overseas were not included in the regular returns made to the Bank.Footnote 71 Even this step was controversial, with some in the Bank finding it “otiose and naive” and feeling “that its only justification would be the cosmetic effect of suggesting to Whitehall that we were not letting Lugano pass into oblivion without taking action.”Footnote 72 Roy Fenton (senior official at the Bank of England) argued that “this is an area in which we have a responsibility,” particularly if the banks were likely to call on the reserves “to rectify misjudgements or misdemeanours.”Footnote 73 Richard Hallett (senior official at the Bank of England) advocated a “low key” and “more chatty form” to be sent to general managers from George Blunden (head of supervision at the Bank of England) or the chief cashier rather than from the governor, but he also wanted some side mention of the “need to watch the relationship of young dealers with brokers . . . and the danger inherent in board policies which have in recent years . . . laid down profit targets or created profit expectations for the dealing operations of their banks.”Footnote 74 After nearly a month, it was finally agreed that formal advice would not merely be “cosmetic” and that the Bank should monitor the dealing limits given to branches and subsidiaries to “ensure that senior management of banks keep such authorities under strict review” as well as allowing the Bank to identify where “unduly lax” practices were being applied.Footnote 75 The letter was sent not only to all authorized banks registered in the United Kingdom (113), but also to authorized branches of foreign banks in London (141). The Chancellor of the Exchequer was shown the letter in advance as evidence that the Bank of England was taking some action in response to Lugano, and thus it served the “cosmetic” purpose.

Conclusion

Rogue trading, a rare but persistent operational risk in financial trading, has been studied surprisingly little in a historical context. Instead, the literature has relied on public sources such as newspapers, court cases, and autobiography. Examining the archival record reveals not only how banks and regulators sought initially to cover up the Lloyds's losses in 1974, but also a surprising lack of remedial action even when an internal inspection revealed wider compliance issues in Swiss branches. In contrast to more recent examples, the most senior executives took no responsibility, nor were they viewed as responsible. The LBI scandal also shows that there are limits to the mitigation that can be achieved by elaborate rules and cross-checking if those rules are not supported by the institution's norms or by the specific norms of the trading room. Colombo's ego as a “foreign exchange man” and the importance he placed on his individual reputation drew him to trade beyond fixed limits, hide losses, and escalate risk. In the end, an external whistle-blower alerted his head office and this third-party check was later institutionalized by Lloyds Bank. These features are very similar to those of rogue-trading scandals forty years later.

But unlike participants in recent cases, Colombo was not competing with other traders in his firm, had no bonus system built around his performance, and faced relatively low expectations from his managers. Nor was he an established “superstar” as a result of previous successes built on risky behavior. These are clearly not necessary elements for rogue trading. Instead, the combination of overconfidence and inadequate supervision at a time of enhanced market risk was at the root of the initial losses. Subsequently, pride and then job security motivated Colombo to engage in an unsuccessful cover-up. His sequential decision-making led to increasingly reckless bets on the dollar exchange rate until he felt pressure to engage in a fraudulent loan to cover his tracks. There is no evidence that LBI's head office encouraged risky behavior in foreign-exchange dealing, but its rules, devised in an era of low risk in exchange markets, did not fit with the norms of Swiss banking (including secrecy, informality, and a lack of paper records) or with the new market risks posed by flexible exchange rates.

The Bank of England was blind to risks in foreign-exchange dealing in overseas branches despite the vulnerability of the domestic banking system to losses that could accumulate very quickly in volatile markets. It relied instead on the internal procedures of major London banks that had longstanding relationships with the Bank of England. This attitude was in line with the informal regulatory framework that had developed in the city of London when there was a cozy cartel among the main commercial banks operating behind exchange controls.Footnote 76 The Bank of England's official response was to formalize principles of good practice in a letter, although without including enforcement mechanisms. However, these best practices had already been part of the rule book at Lloyds; the problem was a failure of compliance.

Since 1974 there have been several initiatives to enhance prudential supervision of international banking, both by disseminating best practices through the Basel Committee for Banking Supervision and by devising elaborate rules for compliance within banks themselves. These measures have not prevented repeated rogue-trading scandals that have arisen mainly in complex trading markets and often (but not always) in overseas offices of large financial institutions. The operational risks posed by young traders who escalate losses in an effort to protect their reputations were clearly evident forty years ago in the very early stages of foreign-exchange trading. This evidence suggests that institutions should focus more on norms than on rules to reduce these risks.