1 Introduction

1.1 General Introduction

In this Element, we introduce lexical multidimensional analysis (LMDA), an extension of the multidimensional (MD) analysis framework developed by Biber in the 1980s (“multi-feature multidimensional analysis”) to study register variation. Through the identification of (lexical) dimensions or sets of correlated lexical features, LMDA enables the analysis of lexical patterning from a multidimensional perspective. These lexical dimensions represent a variety of latent, macro-level discursive constructs. Although LMDA can be utilized for a range of lexis-based analyses, in this Element the focus is on its application to discourse analysis for the exploration of discourses and ideologies.

The authors have independently developed LMDA since the 2010s, initially through Fitzsimmons-Doolan’s analysis of language ideologies in a body of educational policy texts (Fitzsimmons-Doolan, Reference Fitzsimmons-Doolan2014, Reference Fitzsimmons-Doolan2019) and Berber Sardinha’s analysis of representations of American and Brazilian cultures on Google Books (Berber Sardinha, Reference Berber Sardinha2014, Reference Berber Sardinha, Berber Sardinha and Veirano Pinto2019, Reference Berber Sardinha2020). Since then, the approach has been extended to the analysis of other topics and domains, including US migrant education (Fitzsimmons-Doolan, Reference Fitzsimmons-Doolan2023), the historical development of applied linguistics (Berber Sardinha, Reference Berber Sardinha, Friginal and Hardy2021, Reference Berber Sardinha2022a), popular music (Delfino et al., Reference Delfino, Berber Sardinha and Collentine2023), the infodemic (Berber Sardinha et al., Reference Berber Sardinha, Romeiro, Marcondes, Silva, Gerciano, Kauffmann, Pinto, Dutra, Delfino, Bocorny and Sarmento2023), and literary style (Kauffmann & Berber Sardinha, Reference Kauffmann, Berber Sardinha, Friginal and Hardy2021), among other domains.

In this Element, we introduce readers to LMDA by focusing on theoretical and operational issues inherent in this approach. On a theoretical level, we explore the relationship of lexis to discourse and ideologies by discussing how lexis serves as markers of discourse formations and ideological alignment. On an operational level, we provide initial guidance on technical issues, from handling frequency counts to the utilization of statistical procedures. Since LMDA includes qualitative analysis of texts, we offer insights into interpreting sets of correlated lexical features from a discourse analytical standpoint.

Two case studies are included to demonstrate the practical application of LMDA in analyzing discourses in different contexts. The first case study illustrates how LMDA can reveal the discourses surrounding climate change on the conservative GETTR social media platform, providing insights into how these discourses manifest in a contested space. And the second case study examines migrant education ideological discourses, focusing on their distribution over time and by register.

1.2 LMDA’s Foundation in Traditional Multidimensional Analysis

Procedurally and theoretically, LMDA is grounded in traditional MD analysis (TMDA). Douglas Biber developed MD analysis in the mid 1980s (Biber, Reference Biber1988) for the functional description of variation across multiple registers, which, according to Biber and Conrad (Reference Biber, Conrad, Coffin, Hewings and O’Halloran2004, p. 42), are “different varieties of language that are associated with different situations and purposes.” Since then, MD analysis has evolved to address single-register analysis, including examining variation by authors, social groups, or time periods. As such, the primary goal of TMDA is twofold: first, to identify the intrinsic linguistic parameters, or dimensions, that underlie variation (e.g., by register or style); and second, to delineate the linguistic similarities and differences among texts in relation to these dimensions along a continuous space of variation.

Typically, the basis for the interpretation of linguistic co-occurrence in TMDA is functional. According to Biber (Reference Biber1995, p. 30), “linguistic features co-occur in texts because they reflect shared functions.” As a consequence, the dimensions resulting from the co-occurrence of the linguistic features will reflect the communicative functions performed by the texts in particular situational contexts.

Linguistic co-occurrence is captured statistically in TMDA through the computation of correlation coefficients for each pair of linguistic features across the texts in the corpus. Because each observation unit is an individual text, the correlation quantifies how pairs of linguistic features co-occur (positive correlation) or are mutually exclusive (negative correlation) across different texts. However, since in TMDA the association between linguistic co-occurrence and functional realization is predicated on groups of features performing communicative functions, rather than individual pairs of features, it is necessary to rely on multivariate statistical procedures to detect such patterns of association.

Factor analysis leads to the identification of the dimensions, which are the underlying parameters of variation across the texts. The factors are interpreted based on the communicative functions of the co-occurring features and given an interpretive label to capture their essence. Once interpreted communicatively, the factors are considered dimensions.

Since the dimensions represent a continuum of variation, registers can be systematically compared along the dimensions. The similarity between registers is determined by how similarly they use the features that co-occur within these dimensions. Since no single dimension can fully capture the range of similarities and differences among registers, a multidimensional conceptualization of register variation is needed.

The multidimensional nature of the approach is premised on the assumption that multiple parameters of variation act simultaneously on the texts, shaping them to perform a particular job in a particular communicative situation. This means that each single text reflects each dimension to a particular degree, and that no text is free from the incidence of any dimension. The extent to which a text is shaped by the incidence of a dimension is referred to as the extent of its markedness on a dimension. Consequently, different texts will be marked by different dimensions at varying degrees, resulting in a distinctive multidimensional profile of each text. Because functional variation among texts is largely predicted by register (Biber, Reference Biber2012), texts from the same register will tend to have similar multidimensional profiles in TMDA.

The linguistic features used in TMDA are lexico-grammatical, predominantly comprising structural elements such as tense, aspect, subordination, phrasal structures, modalization, and coordination. Additionally, lexical features are categorized into grammatical classes (such as downtoners, hedges, amplifiers) or semantic categories that differentiate within word classes, including nouns (e.g., abstract, animate, technical), adjectives (e.g., color, evaluative, time), and verbs (e.g., communication, mental, existence). This feature set is selected for its ability to describe the underlying communicative parameters of language from a functional perspective. Though the procedures and underlying assumptions about variation are shared with TMDA, LMDA uses only lexical features and, thus, the resulting dimensions are theorized as macro-level discursive constructs such as discourses, ideologies, or themes.

1.3 Discourses and Ideologies

In contrast to TMDA which identifies functional variation in corpora, LMDA is a method for identifying a different type of variation in a corpus – namely that of latent, macro-level discursive structures. Among such structures, this Element focuses on discourses and ideologies, which we elaborate on in this subsection. We use ideological discourses as an umbrella term which includes a variety of constructs that exist in the “socio cognitive” space bounded by and between ideologies and “text or talk” (van Dijk, Reference van Dijk, Zapata-Barrero and Yalaz2018, p. 242). Discourses (Baker, Reference Baker2010), language ideologies (Kroskrity, Reference Kroskrity and Duranti2004; Schieffelin et al., Reference Schieffelin, Woolard and Kroskrity1998), ideological discourses (Fitzsimmons-Doolan, Reference Fitzsimmons-Doolan2023), and representations (Berber Sardinha, Reference Berber Sardinha, Berber Sardinha and Veirano Pinto2019, Reference Berber Sardinha2020) have all been identified in this space. Examples of entities identified under the umbrella of ideological discourses include assumed ideological positions such as immigrants are threats, a people group shares a common language (e.g., Germans speak German), and growth is always desirable. Other entities are less transparently ideological, such as the discourse of educational practice. When we use the term ideological discourses in this Element, we are referring to a range of macro-level discursive constructs that share many common features but can be distinguished on some parameters.

Ideological discourses can be expressed about a range of topics and, though usually highly recognizable as concepts in their explicit form, are rarely expressed explicitly. For our purposes, by ideological discourses, we mean socially shared, socially situated representations of real-world phenomena conveyed implicitly through language use. Because they are shared, ideological discourses also constrain or limit how real-world phenomena are represented. By socially situated, we mean that ideological discourses are developed through social practice and social experience. Because they represent real-world phenomena, ideological discourses make meaning.

Ideological discourses allocate social power (Kroskrity, Reference Kroskrity and Duranti2004). They may also be thought of in terms of dominance. That is, when actions consistent with an ideological discourse are taken, some individuals benefit while others do not (or lose) in terms of resource allocation. Dominant discourses are widely accepted and naturalized (Kroskrity, Reference Kroskrity and Duranti2004). They tend to be expressed and perceived as “facts.” Nondominant discourses can be referred to as resistant or alternative.

As mentioned earlier, the entities of ideological discourses tend not to be expressed explicitly, but are identified with repeated patterns of wording (Stubbs, Reference Stubbs1996, p. 158, Reference Stubbs2001) or evaluative stances (Hunston, Reference Hunston2011). However, register differences also mean that these entities may be expressed differently in different texts (Berber Sardinha, Reference Berber Sardinha, Friginal and Hardy2021). Corpus linguistics studies are typically used to identify these patterns through measures of relative frequency, repetition, and association.

1.4 Corpus Linguistics Approaches to Ideological Discourses

In this subsection, we focus on two influential approaches to discourse analysis that have been integrated with corpus tools and methods to study ideological discourses: critical discourse analysis (CDA) and corpus-assisted discourse studies (CADS).

In the 1990s, CDA emerged as a distinct academic field, marking a development in the study of language and society. It is inherently interdisciplinary, drawing on a diverse array of disciplines including pragmatics, sociolinguistics, philosophy, social psychology, and theoretical linguistics. One of the primary objectives of CDA is to facilitate an intersectional dialog among these disciplines.

As a politically committed field (Caldas-Coulthard & Coulthard, Reference Caldas-Coulthard, Coulthard, Caldas-Coulthard and Coulthard1996, p. xi), CDA assumes a proactive role in seeking social justice, aligning its analytical focus with the pursuit of equitable societal structures. As Forchtner (Reference Forchtner and Chapelle2013, p. 1439) puts it, CDA does not regard “discourse [as] merely talk,” but rather as a constitutive phenomenon that “actually structures conduct” (Webster, Reference Webster2003, p. 89). Across approaches, CDA scholars are committed to “de-mystifying ideologies and power through the systematic and retroductable investigation of semiotic data” (Wodak & Meyer, Reference Wodak and Meyer2009, p. 3).

Although CDA is not a corpus-based approach, researchers have experimented with corpus methods, partly in response to methodological criticism concerning rigor and objectivity. A notable critique comes from Widdowson (Reference Widdowson1995), who contends that CDA analysts often conduct analyses with the primary aim of confirming their pre-existing hypotheses (e.g.,by cherry-picking examples) rather than seeking to gather comprehensive evidence that could potentially contest their views. Similarly, Fowler (Reference Fowler, Caldas-Coulthard and Coulthard1996, p. 8) raises concerns about the scope of CDA, specifically its tendency to engage with a limited range of texts, resulting in evidence that is “fragmentary and exemplificatory.” These criticisms stem from the qualitative nature of CDA, which demands deep and interpretative engagement with data, often at the expense of a broader sample size. Addressing the issue of limited text samples, Stubbs (Reference Stubbs, Ryan and Wray1997) suggests incorporating large text samples into CDA, which can be achieved through various approaches, one of which is to utilize existing precompiled corpora as sources for extracting a more narrowly focused collection of texts that are relevant to the research objectives.

In applying corpus linguistics to CDA, researchers typically utilize tools like concordances, word frequency lists, and keywords. An example is Orpin (Reference Orpin2005), who employed concordancing and word frequency counts in the analysis of the semantic domain of corruption. The study analyzed the frequencies of collocates of these words, using a corpus of 800 texts, sourced from four newspapers within the Bank of English.

Beyond frequency-based analysis for CDA studies using corpus linguistics, Stubbs (Reference Stubbs, Ryan and Wray1997) proposes the adoption of methodological principles advocated by MD analysis. First, this would involve the recognition that “registers are very rarely defined by individual features, but consist of clusters of associated features which have a greater than chance tendency to co-occur” (Stubbs, Reference Stubbs, Ryan and Wray1997, p. 5). Second, this integration would involve adopting analyses “of co-occurring linguistic features” (Stubbs, Reference Stubbs, Ryan and Wray1997, p. 9), a key principle of MD analysis, rather than focusing solely on individual features. Although these suggestions may not have been embraced in the practice of CDA, they highlight the potential for applying MD principles to identify and critique ideological discourses from a corpus linguistic perspective. Essentially, these points lead to a multi-way characterization of texts and registers, away from binary distinctions. We argue that both suggestions can be incorporated in corpus-based analyses of discourse through LMDA, as we demonstrate in this Element.

In turn, CADS represents a development within corpus linguistics that integrates corpus-based methods and discourse analysis. Unlike CDA, where the integration of corpus methods was a subsequent development, CADS has incorporated corpus linguistics techniques as a fundamental part of its approach from its inception in the late 1990s and early 2000s. It emerged primarily in the UK and Italy through the pioneering work of researchers such as Paul Baker, Michael Stubbs, Tony McEnery, and Alan Partington. This development was facilitated by the increasing availability of both large corpora and personal corpus analysis software, such as WordSmith Tools (Scott, 1996).

As in corpus-assisted CDA, CADS researchers also rely on mainstream corpus tools such as concordances, keywords, and collocate and word lists, which enable them to both mine the corpus for the most salient linguistic features associated with a discursive issue and identify the patterns surrounding these linguistic features. As Gillings et al. (Reference Gillings, Mautner and Baker2023) put it, “corpus assistance helps us to link large-scale social phenomena with linguistic choices at the micro level.” Analysts in CADS concentrate on uncovering recurrent patterns within the corpus, which is in line with the key concept of discursive repetition, “the idea that an attitude or ideology can be transmitted over a long period of time through people’s repeated encounters with words or phrases, eventually resulting in a discourse being uncritically perceived as natural or normal” (Baker, Reference Baker and Chapellein press).

Keyword analysis (Scott, 1996), which identifies words that are used statistically more frequently in one corpus compared to another, is a widely used method in CADS due to its utility in helping researchers sample a subset of words from the entire corpus that merit further investigation. Baker (Reference Baker2014) employed keyword analysis to investigate the gender differences hypothesis in language use, concluding that this hypothesis, as it pertains to lexical choice, was not substantiated by the data. Depending on how a keyword study is designed, the approach can be used to identify discourses or ideologies. For example, Baker and McEnery (Reference Baker, McEnery, Baker and McEnery2015) identified discourses about government benefits in a corpus of tweets by finding and grouping keywords.

In CADS, as in most keyword studies, the detection of keywords typically relies on frequency counts taken across the entire corpus rather than on a text-by-text basis (but see Egbert and Biber [Reference Egbert and Biber2019] for a version of keyword analysis that uses text-based counts). This methodological choice can lead to skewed distributions of keyword usage. Such a skew arises because the corpus-wide counts may be influenced by the overuse of certain words by individual speakers or texts, rather than reflecting marked choices across the texts.

Collocational networks are an innovation aimed at flagging groups of collocations through visual displays that represent the connections among different individual collocations in a corpus. Tools like GraphColl, which is part of the LancsBox suite, provide capabilities for constructing collocation networks (i.e., associational relationships among a node’s first and additional order collocates). A network is composed of different individual graphs, which can take various forms, including linear graphs, triangles, and quadrilaterals. As Baker (Reference Baker2016) shows, these different graphs can indicate specific linguistic patterns among the words, such as grammatical class membership, lexical bundles, or frames.

Each of these corpus linguistics approaches to discourse and ideologies is based on a theoretical relationship between lexical variables and ideological discursive constructs. The next subsection explores such theories.

1.5 Theories of Lexis

Though Stubbs (Reference Stubbs and Groom2015) indicates that there is no unified theory of lexis, most theoretical models that give prominence to lexis are rooted in collocation. These include theories of semantic prosody and semantic preference – and all variations in nomenclature referring to these ideas, extended lexical units (Stubbs, Reference Stubbs2009), lexical priming (Hoey, Reference Hoey2005), and knowledge-free associative patterning (Phillips, Reference Phillips1985). A collocation is a node word and a word that repeatedly and meaningfully co-occurs with that node within a given local span in a text or a corpus. The local span is often four words to the left and four words to the right of the node. “Repeatedly” and “meaningfully” can be operationalized in a variety of ways by the analyst in terms of frequency and association (Brezina et al., Reference Brezina, McEnery and Wattam2015). Firth established the theoretical groundwork for collocation and famously claimed that we “shall know a word by the company it keeps” (1957/1968, p. 11). It has been well established that collocations can reveal socially loaded perspectives (Baker, Reference Baker2010, Reference Baker2016; Stubbs, Reference Stubbs1996), and Baker (Reference Baker2016) shows how analysis of collocational networks can reveal information which may have “ideological significance” (p. 148).

Semantic preference and semantic prosody are two of the primary mechanisms through which collocation creates meaning. Semantic preference is also called semantic association (Hoey, Reference Hoey2005) and generally refers to the lexical set (i.e., thematic set) to which collocates of a node belong (e.g., the domain of medicine or the absence/change of state; Partington, Reference Partington2004). Semantic prosody has two meanings (Hunston, Reference Hunston2007). The more common meaning is the evaluative (positive or negative) association a node and its collocates convey. Semantic prosody in this sense is also called discourse prosody (Stubbs, Reference Stubbs2001) and evaluative prosody (Partington et al., Reference Partington, Duguid and Taylor2013). Hunston (Reference Hunston2007) concludes that meaning derived from semantic preference and semantic prosody can often (but not always) be carried across texts by individual words. Finally, both semantic prosodies and semantic preferences are thought to often demonstrate register association (Partington, Reference Partington2004).

Hoey’s (Reference Hoey2005) theory of lexical priming attempts to account for collocation observed in corpora through a psychological process of priming which is also sensitive to register. In this theory, at the local level, based on an individual’s language experience, individual words are primed for collocation, semantic association (semantic preference), colligation, and pragmatic functions. Through a nesting operation, multi-word units are created with their own primes. At the level of text, words/multi-word units are primed to co-occur with other words/multi-word units in a text (textual collocation), in particular discourse functions (textual semantic association) and in particular sections of a text (textual colligation). In sum, the theory of lexical priming suggests that a large part of an individual’s language can be accounted for through bottom-up processes driven by associational patterns in the lexical system with the text as an important unit of analysis.

Finally, Phillips (Reference Phillips1985) hypothesizes that “a distributional analysis of linguistic substance; invoking no knowledge of the semantic content, the syntactic organization, or the lexical meaning of the text; would reveal global patternings in the lexis of the text” (p. 11) that he calls macrostructures. He goes on to test this hypothesis in a textbook, identifying the “aboutness” of chapters and the text as a whole based on frequency and associational measures of collocations, resulting in multiple groups of words he calls “lexical sets.” While the macrostructure in question in this study is aboutness, ideological discourses can be similarly categorized as macrostructures (Ellis, Reference Ellis2019).

These theories indicate quite a bit about identifying ideological discourses from lexis. First, examining lexis through corpora reveals socially shared primings, collocations, semantic prosodies, and semantic preferences. As repositories of socially shared language, corpora reveal shared lexical primings, which in turn add to the priming data for authentic users of the language captured in a corpus. Hoey (Reference Hoey2005) notes that “priming leads to a speaker unintentionally reproducing some aspect of language, and that aspect, thereby reproduced, in turn primes the hearer” (p. 9). As mentioned earlier, according to Hoey (Reference Hoey2005), priming can explain collocation and Partington (Reference Partington2004) describes how socially shared primes account for socially shared semantic preferences and semantic prosodies, which are part of the communicative competence of individual speakers. He also presents a model in which collocations, semantic preferences, and semantic prosodies are all derived from text and each other in increasing levels of abstraction (with semantic prosodies being the most abstract). That is, a collocation is identified in a text, a semantic preference is identified from a set of collocations, and a semantic prosody is identified from a set of semantic preferences.

Second, these theories suggest that information about many linguistic levels seems to be accessible from associations among lexical items when text is the unit of analysis. Hoey (Reference Hoey2005) shows how it is possible that the lexical system encodes the grammatical system, concluding that “what we think of as grammar is the product of the accumulation of all of the lexical primings in an individual’s lifetime” (p. 159). Phillips (Reference Phillips1985) is able to identify textual macrostructures from such associations. The underlying associative structure and successful performance of contemporary large language models (e.g., ChatGPT) also empirically validate this claim. Finally, the fact that collocations, semantic preferences, and semantic prosodies are all sensitive to register means that contextual/situational/social information must also be encoded in lexical distribution.

Therefore, taken together, theories of discourse and ideology and lexis, as well as corpus linguistics approaches to ideological discourses discussed in the previous subsection, suggest that examining associational, co-occurrence patterns of lexis through corpora using text as the unit of analysis can reveal ideological discourses. As repositories of socially shared language, depending on the alignment between the design of a specific corpus and the discourses being identified, corpora are ideal data sources. Lexis seems to be the appropriate linguistic level for identifying macrostructures such as ideological discourses conveyed through evaluative language. Partington’s (Reference Partington2004) model sets up discourses as being an additional level of abstraction beyond semantic prosodies which can thus be derived from lexical co-occurrence. There is an indication that co-occurring sets of lexical items within and across texts carry ideological information. Finally, register seems to be an important delimiter in terms of both lexical association patterns and ideological expression, or, as Silverstein (Reference Silverstein, Schieffelin, Woolard and Kroskrity1998, p. 126) puts it, “if all cultural and linguistic phenomena are essentially event linked, even where they appear to be manifestations of people’s ‘intuitions,’ they are, as it were, ideological ‘all the way down.’”

1.6 Similarities and Differences between Traditional and Lexical MDA

As LMDA is an extension of TMDA and both approaches have roots in the Flagstaff School of Corpus Linguistics (cf. Cortes & Csomay, Reference Cortes, Csomay, Cortes and Csomay2015), their procedures are roughly the same and they share foundational assumptions. That is, as with conducting a TMDA, to conduct an LMDA, a researcher (1) constructs a corpus, (2) identifies variables for analysis, (3) counts occurrences of the variables per text, (4) subjects the counts to a multidimensional analysis to identify underlying constructs, and (5) for each dimension in the result, engages in qualitative analysis of texts with high values to interpret the underlying construct based on how the variables are deployed. However, distinct characteristics emerge as each approach is tailored to specific research goals. These differences and similarities will now be outlined, beginning with the common traits.

Variation: Both TMDA and LMDA are founded on the principle that language use inherently varies depending on the context. This means that language cannot be treated as a homogeneous entity; rather, its usage is shaped by the specific historical and contextual factors in which it occurs. Consequently, linguistic descriptions within these frameworks must account for systematic variation in language use.

Comprehensiveness: Both TMDA and LMDA assume a comprehensive approach to linguistic description, as opposed to a reductionist one. This means that their descriptions are based on a varied set of linguistic features, rather than starting off with just a few elements. This comprehensive approach allows for a more detailed and inclusive analysis of language use.

Co-occurrence: The need for a large and varied pool of linguistic features arises from the need to model linguistic co-occurrence; in turn, the relevance of co-occurrence arises from the fact that it reflects shared function (a communicative function for TMDA and a discursive function for LMDA). Since linguistic co-occurrence plays such a central role in MD analysis, it has achieved “formal status in the Multi-Dimensional approach to register variation” (Biber, Reference Biber1995, p. 30).

Dimensionality: Both TMDA and LMDA share the hypothesis that latent constructs underlie language usage, shaped by the conditions in which language is used in natural settings. This hypothesis posits that these underlying constructs manifest as “dimensions” – sets of co-occurring linguistic features across texts.

Multidimensionality: Given that language variation is patterned by dimensions, and that multiple dimensions are needed to account for variation, both approaches are inherently multidimensional. This means they presuppose the simultaneous action of various dimensions on texts, shaping them to perform specific communicative functions in TMDA or to convey particular discourses or ideological formations in LMDA.

Parsimony: While both TMDA and LMDA utilize a large and varied set of linguistic features, their objective is to identify the smallest number of dimensions that account for language variation. This approach reduces the extensive initial set of individual characteristics into a few cohesive groups of variables, collectively explaining the variation observed across texts.

Comparative stance: Both TMDA and LMDA foster comparisons, as they highlight similarities and differences between various language varieties (TMDA) or social contexts (LMDA). By comparing different categories along the dimensions in extended study design, these categories can be more sharply portrayed.

Statistical foundation: Since a reliance on statistical methods is a defining trait of the Flagstaff School of Corpus Linguistics, both types of MD analysis depend on statistical analysis. These methods are essential for detecting latent phenomena, that is, constructs that while predicted are not directly observable. The primary statistical procedure in MD analysis is correlation, which is used to measure the systematic co-variation of variables. Given the comprehensive approach to the array of linguistic features and the goal of identifying dimensions of variation, MD analysis employs multivariate statistical techniques, including dimensionality reduction methods like factor analysis. The factors identified in such analyses represent sets of correlated variables, corresponding to patterns of cross-text variation.

Qualitative interpretation: Despite their strong quantitative foundation, both approaches necessitate qualitative interpretation of texts to assist in unveiling the underlying communicative functions (TMDA) or discourses (LMDA). Without careful interpretation, based on the consultation of numerous text samples, dimensions cannot emerge from factors.

Despite their similarities, TMDA and LMDA can be distinguished based on differing research goals, feature sets, and interpretive foci.

Research goals: TMDA is particularly relevant for research goals that focus on the functional aspects of language. This approach is grounded in the idea that shared linguistic features indicate a shared function. It is typically employed to describe register variation along functional lines, essentially detailing the differences and similarities across various registers in a language or domain. If a researcher’s objective involves analyzing texts from a functional perspective through structural, syntactic, or morphological classes, then TMDA is the appropriate method.

In contrast, as presented in this Element, LMDA is designed to cater for the identification of latent, macro-level constructs encoded in discourse. The range of research goals that can be addressed with a focus on discourse is vast, covering such aspects as ideologies, representations, identities, themes, motifs, schemas, and many other conceptual systems. Thus, if the research goal includes describing the lexical materialization of such discourse-based constructs, then LMDA is the necessary method over TMDA.

Linguistic features: The features typically used in a TMDA are lexico-grammatical, comprising structural, syntactic, and morphological classes. The exact features to be used in a TMDA project depends on previous consideration of the features of relevance for the specific research goals. On the other hand, LMDA utilizes the actual words in the texts as its primary units of analysis, contrasting with the broader lexico-grammatical classes employed in TMDA. Thus, in an LMDA, the features used are entirely lexical, including the actual words, their base forms (lemmas), semantic categories, collocations, or n-grams.

Interpretive focus: TMDA primarily focuses on identifying functional parameters of variation in language. By “function,” we refer to the communicative roles that linguistic features play, enabling users to perform specific tasks with language. As Biber and Conrad (Reference Biber and Conrad2019, p. 2) state:

The underlying assumption of the register perspective is that core linguistic features (e.g., pronouns and verbs) serve communicative functions. As a result, some linguistic features are common in a register because they are functionally adapted to the communicative purposes and situational context of texts from that register.

The dimensions in TMDA, which are correlated sets of linguistic features, correspond to the underlying macro communicative function of the texts. Researchers determine these underlying macro functions through factor interpretation, linking the linguistic patterns to the situational characteristics of the registers. Consequently, a functional interpretation of the patterns within these dimensions is essentially “an account of why these patterns exist” (Biber & Conrad, Reference Biber and Conrad2019, p. 69; emphasis in the original text).

Conversely, in LMDA, the interpretive focus is on unearthing the latent discourse constructs materialized in the texts. The interpretation taps into the potential of lexical features as signposts or entry points to the analysis of discourse, as acknowledged in corpus-assisted approaches to discourse analysis. For instance, according to Stubbs, lexical keywords are “nodes around which ideological battles are fought” (Stubbs, Reference Stubbs2001, p. 188). Similarly, Mautner describes a word such as entrepreneurship as a “carrier of key values” (Mautner, Reference Mautner2005, p. 96), providing “focal points around which current discourses … crystallize” (Mautner, Reference Mautner2005, p. 111), in the context of educational entrepreneurialism. In turn, Krieg-Planque (Reference Krieg-Planque2010, p. 9) considers that particular lexical expressions, which she refers to as “formulas,” have a dual role of both constructing and crystallizing political and social issues. Meanwhile, TMDA offers limited entry points to the discursive layers of language because of its goal of describing variation at the functional level of language use.

1.7 Overview of Element

This section has presented the foundation of LMDA for identification of ideological discourses, demonstrating that the approach is grounded in (1) procedures of TMDA and CADS and (2) theories of lexis and discourse studies. Following this introduction, in Section 2, the major studies to date using LMDA will be synthesized. The synthesis will address variation in design and constructs identified, as well as lessons learned both in terms of methodology and theoretical advances. This section will explicitly and robustly attend to the range of meaning systems encoded in lexis that are identifiable by application of LMDA.

In Section 3, step-by-step guidance on how to perform an LMDA will be provided. The major methodological steps will be presented and illustrated, including corpus design, part-of-speech tagging and lemmatization, feature selection and counting, statistical analysis, and the interpretation of the results from both a qualitative and a quantitative perspective.

In Section 4, Case Study 1 will demonstrate how LMDA can be used to detect discourses in social media, more specifically on the conservative platform GETTR. The analysis focuses on the discourses around climate change underlying thousands of messages challenging environmental activism.

In Section 5, Case Study 2 will showcase how this approach allows researchers to explore the distribution of the constructs identified in LMDA over time or over other variables using inferential statistics. This case study uses four ideological discourses about twenty-first-century migrant education in the US.

Finally, Section 6 will briefly summarize the major points presented, consider the potential of the approach, and explore some of its possible future developments.

2 Synthesizing Existing LMDA Scholarship

2.1 Introduction

This section will focus on the LMDA studies conducted thus far. First, early LMDA studies directly grown out of TMDA will be presented, followed by more recent LMDA studies which have identified latent discursive constructs, explored the distribution of such constructs, derived additional measures from the latent discursive construct data, or some combination of these outcomes (Table 1). Next, cross-cutting patterns across this body of studies will be discussed, including variation in design and constructs identified, as well as lessons learned both in terms of methodology and theoretical advances. Though the identification of ideological discourses through LMDA are the focus of this Element, this synthesis will attend to the range of meaning systems encoded in lexis that have been identified through the application of LMDA.

Table 1 Existing LMDA studies and research questions addressed.

| LMDA Study Outcome | Authors | Year | Research Questions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Establish foundation | Biber | (Reference Biber1993a) | Which clusters of collocations reflect similar underlying word senses? (p. 532) |

| Establish foundation | Crossley and Lowerse | (Reference Crossley and Louwerse2007) | Can categorizations be obtained using a simple n-gram algorithm? (p. 457) |

| Identify latent discursive constructs | Fitzsimmons-Doolan | (Reference Fitzsimmons-Doolan2014) | What is the language ideology profile expressed in Arizona Department of Education (ADE) language policy texts? (p. 62) |

| Explore distribution of latent discursive constructs | Fitzsimmons-Doolan | (Reference Fitzsimmons-Doolan2019) | Is there variation in the language ideologies expressed in a corpus of institutional language policy texts attributable to language policy register? |

| Identify latent discursive constructs; explore distribution of latent discursive constructs | Berber Sardinha | (Reference Berber Sardinha, Berber Sardinha and Veirano Pinto2019) | What are the linguistic forms of representation connected to nationalities that have circulated in discourse over time? (p. 232) |

| Derive additional measures from latent discursive construct data | Berber Sardinha | (Reference Berber Sardinha2020) | What is the historical distribution of representations of the United States and Brazil formed around the use of the nationality adjectives American and Brazilian? (p. 183) |

| Identify latent discursive constructs; explore distribution of latent discursive constructs; derive additional measures from latent discursive construct data | Berber Sardinha | (Reference Berber Sardinha, Friginal and Hardy2021) | (1) What are the major discourses of applied linguistics? (2) How do these discourses shift over time? (3) What historical periods can be discerned based on these discourse shifts? (p. 302) |

| Identify latent discursive constructs; derive additional measures from latent discursive construct data | Kauffman and Berber Sardinha | (Reference Kauffmann, Berber Sardinha, Friginal and Hardy2021) | 1. What are the functional and lexical dimensions of variation in Machado’s major works? 2. What relationships can we find between the lexical and functional dimensions of variation through a canonical correlation analysis? (p. 358) |

| Identify latent discursive constructs | Clarke, McEnery, and Brookes | (Reference Clarke, McEnery and Brookes2021) | Can keywords be grouped into dimensions which may, where relevant, aid analysts in discovering groups of texts which represent discourses that are linked to specific subregisters? (p. 146) |

| Derive additional measures from latent discursive construct data | Berber Sardinha | (Reference Berber Sardinha2022a) | What discourses are present in an academic journal over a given time period? What are the major historical eras of that journal based on co-existing discourses? |

| Explore distribution of latent discursive constructs | Clarke, Brookes, and McEnery | (Reference Clarke, Brookes and McEnery2022) | What is the potential for keyword co-occurrence to identify changing discourses over time? |

| Identify latent discursive constructs | Fitzsimmons-Doolan | (Reference Fitzsimmons-Doolan2023) | Which ideological discourses about im/migration are present in a multi-register corpus of 21st century texts about US migrant education? |

| Identify latent discursive constructs | Clarke | (Reference Clarke, Maci, Demata, McGlashan and Seargeant2024) | How are climate change and global warming represented in pseudoscience webtexts? |

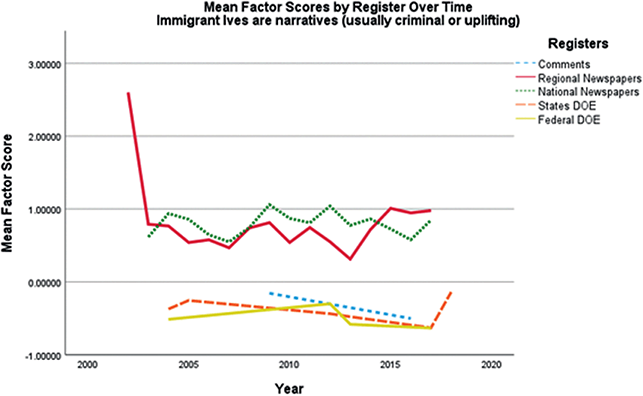

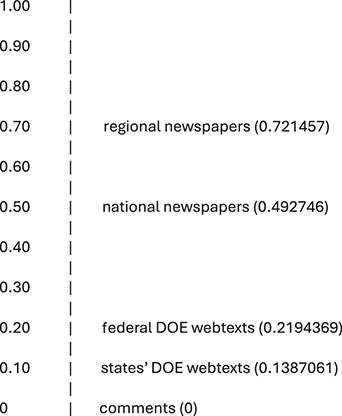

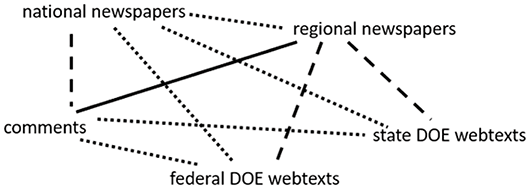

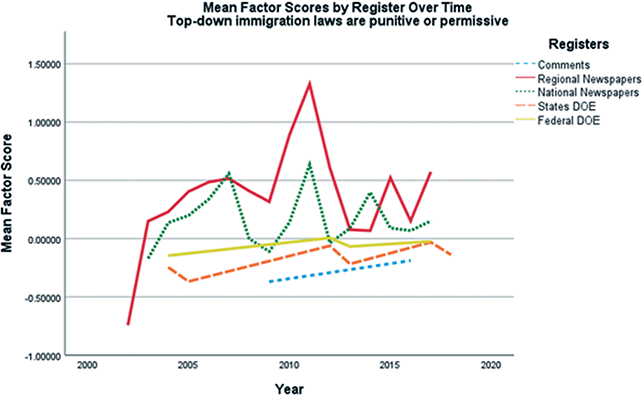

| Explore distribution of latent discursive constructs | Fitzsimmons-Doolan | This volume | What patterns related to register and time are apparent in the distribution of four ideological discourses about migrant education? |

2.2 Establishing a Foundation

As noted in Section 1, LMDA is an outgrowth of the methodological approach of TMDA, pioneered by Biber (Biber, 1988; Berber Sardinha & Veirano Pinto, Reference Berber Sardinha and Veirano Pinto2019). Prior to the recent body of LMDA scholarship, two early studies, firmly grounded in the lexico-grammatical multidimensional analysis tradition, experimented with lexical variables. In a 1993 case study, Biber asked “which clusters of collocations reflect similar underlying senses” (Biber, Reference Biber1993a, p. 532) in order to address gaps in lexicography methods at the time. Two nodes were used in the case study: certain and right. From a subsample of the Longman/Lancaster corpus, collocates occurring with each node more than thirty times were identified and the frequency counts of each collocation per text were computed and used in a factor analysis. The resulting factors were interpreted as word senses. For example, for the node, right, Factor 1 was directional (e.g., right hemisphere, right side) and Factor 2 conveyed immediacy (e.g., right there, right now). Later, addressing gaps from computational linguistics, Crossley and Louwerse (Reference Crossley and Louwerse2007) used frequency counts of bigrams across multiple spoken and written corpora representing different registers in a factor analysis. The factors were interpreted as register dimensions (i.e., scripted vs. unscripted, spatial vs. nonspatial) and mean factor scores for each register were plotted to show how the registers differed for each factor/dimension of register variation. Both studies were interpreted as successful in addressing the subfield gaps they set out to address and laid the groundwork for future LMDA studies.

2.3 Identifying Latent Discursive Constructs

The primary outcome of an LMDA is the identification of a latent macrostructure encoded in lexis that conveys meaning. Such constructs include language ideologies, representations, discourses (both thematic and ideological), and thematic dimensions of literary style. Studies with this outcome are presented in the text that follows.

Fitzsimmons-Doolan (Reference Fitzsimmons-Doolan2014) used LMDA to identify and describe language ideologies. Modifier collocates (e.g., academic language, adolescent literacy, ordinary English) of node words representing language constructs (i.e., academic language, adolescent literacy, ordinary English) were identified. A factor analysis was conducted using normed counts of occurrences of the collocates per text. The corpus under investigation contained language policy texts from the Arizona Department of Education (DOE) website. The resulting five factors indicated by co-occurring collocates were interpreted as language ideologies. For example, after investigating how they were deployed in texts, the co-occurring collocates on Factor 2 (i.e., discrete, controversial, English, classroom, structured) were interpreted as indexing the language ideology, language acquisition is systematically metalinguistic and monolingual.

Berber Sardinha and his associates have engaged in many LMDA studies to identify a variety of discourse constructs. Berber Sardinha (Reference Berber Sardinha, Berber Sardinha and Veirano Pinto2019) applied LMDA to identify national representations. For two separate analyses, frequency counts per year of the bigrams american + noun and brazilian + noun in the Google bigram database derived from Google Books from 1800–2008 were subjected to a factor analysis. The resulting five factors for each nationality were interpreted as national representations. For example, superpower vs. local status was identified as an American representation and raw materials and the landscape was identified as a Brazilian representation. Berber Sardinha (Reference Berber Sardinha, Friginal and Hardy2021) reports multiple LMDA analyses concerned with identifying discourses in the discipline of applied linguistics over time. In the first analysis, normed counts of the most frequent noun, verb, and adjective lemmas per text in five applied linguistics journals over time were subjected to a factor analysis. This resulted in six discourses of applied linguistics (e.g., applied linguistics as an empirical/physical/natural science, speech as interaction vs. speech as pronunciation). A second LMDA in Berber Sardinha (Reference Berber Sardinha, Friginal and Hardy2021) used the same variables/measures as the first analysis from research articles in TESOL Quarterly only and found five discourses (e.g., linguistic theory vs. education). In Kauffmann and Berber Sardinha (Reference Berber Sardinha, Friginal and Hardy2021), an LMDA of a corpus of the works of Brazilian author, Machado de Assis, was conducted. Normed counts of 346 lemmas that met dispersion and frequency criteria were included in a factor analysis which resulted in nine factors interpreted as stylistic dimensions. These dimensions identified major themes in the author’s work (e.g., romance, love, and passion).

Developing the approach of selecting lexical variables in relation to a node word, Fitzsimmons-Doolan (Reference Fitzsimmons-Doolan2023) applied LMDA to identify ideological discourses about migrant education. Using a multi-register corpus of twenty-first-century texts on the topic of migrant education developed for the study, 114 collocates (e.g., services, reform, data, and law) of the node *migr* that occurred in evaluating or modifying grammatical roles were identified as variables for the LMDA. Normed counts of the variables per text were used in a factor analysis and, after qualitative analysis focusing on the texts with the highest factor scores for each ideological discourse, the factors of co-occurring collocates were interpreted as ideological discourses (e.g., US immigration policies are problematic, but there is no consensus for solutions).

Finally, Clarke and her associates have recently engaged in a series of studies using multiple correspondence analysis (MCA) that identify patterns of variation in the co-occurrence of lexical variables. This approach, which the authors call keyword co-occurrence, first identifies keywords in a corpus of interest and then applies MCA to identify dimensions that are interpreted as representational discourses (Clarke, Reference Clarke, Maci, Demata, McGlashan and Seargeant2024; Clarke et al., Reference Clarke, McEnery and Brookes2021; Clarke et al., Reference Clarke, Brookes and McEnery2022).

2.4 Exploring Distribution of Latent Discursive Constructs

Once the latent discursive constructs have been identified, their distribution in the corpus according to another variable can be described. The most common variables by which the distribution has been studied are time and register. In a follow-up study to Fitzsimmons-Doolan (Reference Fitzsimmons-Doolan2014), Fitzsimmons-Doolan (Reference Fitzsimmons-Doolan2019) explored the distribution of the 2014 language ideologies across the corpus of policy webtexts by language policy register. After coding each text in the corpus by language policy register (see Lo Bianco, Reference Lo Bianco2008) (i.e., language policy documents, discourse about language policy, institutional models of language policy, and lists), mean factor scores per register were used in analyses of variance for each language ideology. The analysis found that for four out of five language ideologies there were significant differences among language policy registers and that institutional models of language policy did “the ideological heavy lifting.” Similarly, in Berber Sardinha (Reference Berber Sardinha, Berber Sardinha and Veirano Pinto2019), which identified national representations in the Google Books corpus, for each representation, ANOVAs revealed significant and large differences in the distribution of the national representations between decades. In a follow-up study of their MCA of keywords from UK news texts about Islam, Clarke et al. (Reference Clarke, Brookes and McEnery2022) plotted coordinates (measures of strength of discourse representation) for each article for each discourse to track representation of the discourse in the corpus over time.

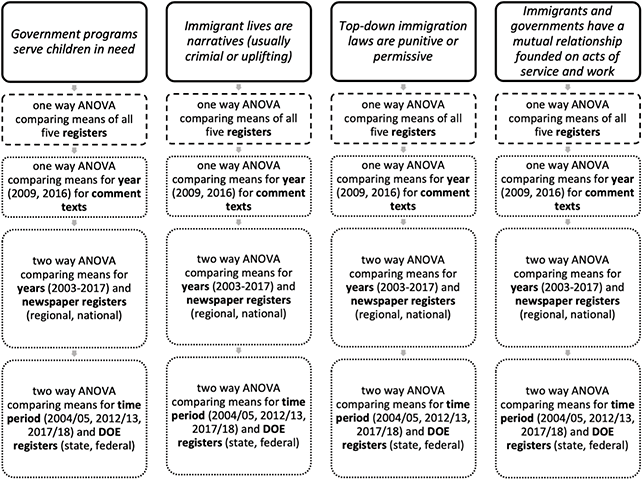

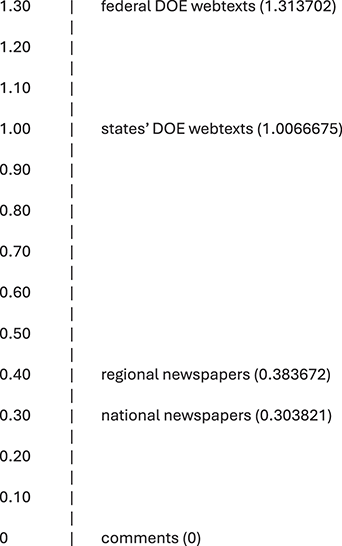

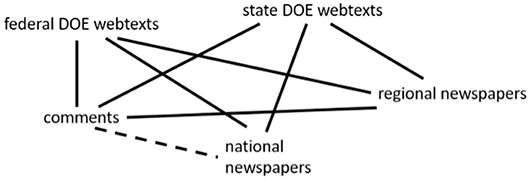

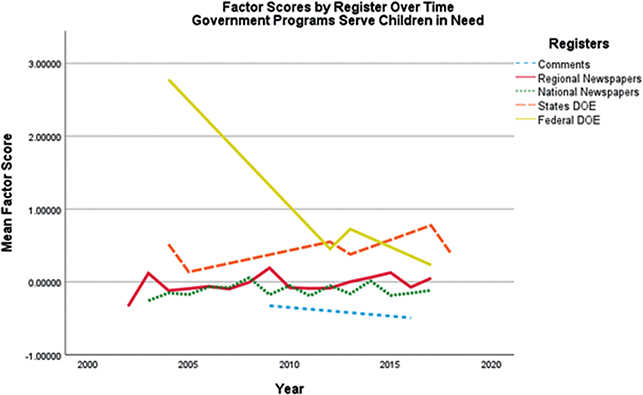

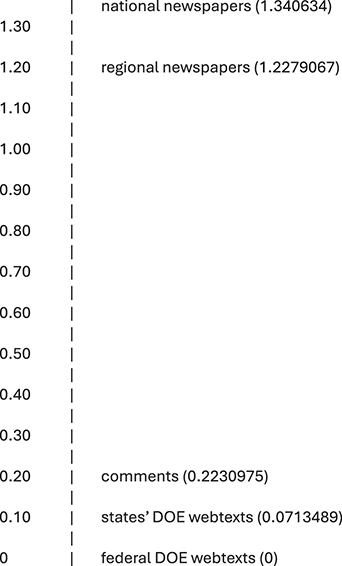

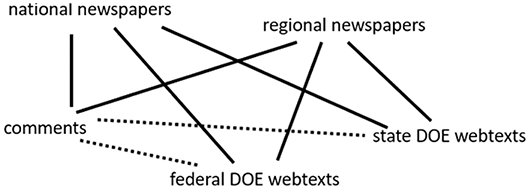

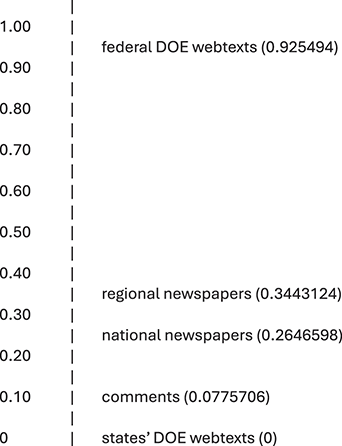

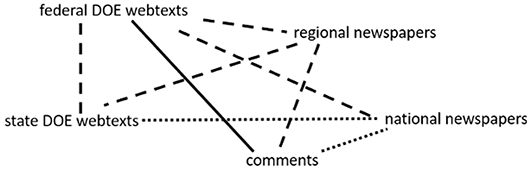

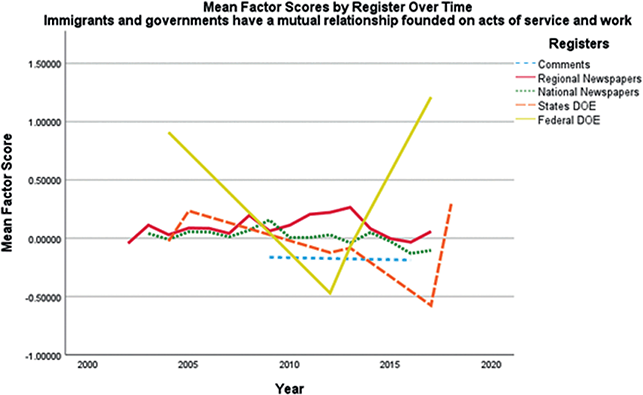

Two studies have examined the distribution of discourses across multiple variables. In Berber Sardinha’s (Reference Berber Sardinha, Friginal and Hardy2021) study of discourses in applied linguistics journals, for each discourse, ANOVAs and coefficients of determination revealed significant effects for decade and journal as well as interaction effects. Finally, Section 5 in this Element presents a follow-up study in which a series of analyses of variance revealed how and to what degree four of the eleven ideological discourses identified in Fitzsimmons-Doolan (Reference Fitzsimmons-Doolan2023) varied over time (2003–17) and register (i.e., regional newspapers, national newspapers, newspaper comments, state DOE webtexts, federal DOE webtexts).

2.5 Deriving Additional Measures from the Latent Discursive Construct Data

Another outcome of LMDAs is the generation of information about additional variables using the latent discursive construct data as a source. For example, Berber Sardinha (Reference Berber Sardinha2020) used factor scores for each year from the 2019 study of national representations in a cluster analysis to reveal historical periods for each nationality based on bigram co-occurrence patterns across dimensions. The analysis found eight historical clusters in the brazilian data ranging from Cluster 1 – The 19th century: natural features and aspects of life to Cluster 8 – The late 20th and early 21st centuries: the economy, politics, arts, sciences, the people, religion and the environment. Similarly, in Berber Sardinha’s (Reference Berber Sardinha, Friginal and Hardy2021) study of discourses in applied linguistic journals, a cluster analysis of factor scores revealed two historical eras across discourses: 1946–late 1980s and from the late 1980s to 2015. Berber Sardinha (Reference Berber Sardinha2022a) extended the analysis of the LMDA of the TQ articles presented in the 2021 study by conducting a cluster analysis to identify major eras in the publication history of TQ based on the discursive variables. The cluster analysis identified two major eras: 1967–92 and 1993–2016.

Finally, Kauffmann and Berber Sardinha’s (Reference Berber Sardinha, Friginal and Hardy2021) study of Machado’s literary texts helped make clear the wide range of research questions LMDA can be used to address. In addition to the LMDA reported earlier, a TMDA as well as canonical correlation analysis were applied to the corpus. The goal was to present an MDA-informed analysis of Machado’s literary style. The TMDA used twenty-nine linguistic features related to style and identified five factors interpreted as functional and aesthetic dimensions of style (e.g., narrative discourse). A canonical correlation analysis merged the two MDAs and found four correlations (e.g., introspective, formal romantic discourse).

2.6 Looking Forward

Three additional unpublished studies across different domains demonstrate additional possibilities for LMDA outcomes. In Berber Sardinha (Reference Berber Sardinha2023), the discourses surrounding the COVID-19 pandemic were analyzed using a 825-million-word sample from the Coronavirus corpus (Davies, Reference Davies2021). In this study, four lexical dimensions were identified, each corresponding to a significant representation of the pandemic from its onset in 2020 up to March 2021. The study demonstrated the scalability of LMDA for larger corpora. In Berber Sardinha (Reference Berber Sardinha and Crosthwaite2024), a curated corpus of messages and images posted on Twitter by climate action supporters and deniers of human-led climate change was employed to detect the major discourses shaping the online debate on this issue. A key methodological innovation was the application of LMDA to detect visual dimensions based on the automatic annotation of social media images using computer vision technology. Finally, Berber Sardinha et al. (Reference Berber Sardinha, Delfino and Collentine2022) used a similar design to Kauffmann and Berber Sardinha (Reference Kauffmann, Berber Sardinha, Friginal and Hardy2021) and merged semantic dimensions from an LMDA of song lyrics and acoustic dimensions from a second MDA of Spotify acoustic tags on the same songs in a canonical correlation analysis.

Taken together, among these seventeen studies using LMDA techniques, a number of cross-cutting patterns emerge. These are addressed in the next subsections.

2.7 Inputs Change the Outputs

While the basic technique in LMDA remains constant, there are several deliberate design permutations across the fifteen published LMDA studies that change the analysis results. That is, all LMDA studies use measures of lexical variables across a corpus of texts in a multidimensional (usually factor) analysis to identify co-occurrence patterns among the variables. However, when different lexical variables are used or a different unit of measure is used, different constructs are identified through the factor analysis. Table 2 presents the fifteen published LMDA studies grouped into sets by similar designs, as well as the lexical variable, variable measure, and the construct operationalized from the resulting factors for each study.

Table 2 Published LMDA studies grouped by similar design characteristics.

| Design Set | Study | Lexical Variable | Measure | Construct Identified |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Biber (Reference Biber1993a) | Collocation | Frequency/text | Word senses |

| Crossley and Louwerse (Reference Crossley and Louwerse2007) | Bigrams | Frequency/text | Dimensions of register variation | |

| 2 | Berber Sardinha (Reference Berber Sardinha, Berber Sardinha and Veirano Pinto2019, Reference Berber Sardinha2020) | National adj + noun bigrams | Normed frequency/year | National representations |

| 3 | Fitzsimmons-Doolan (Reference Fitzsimmons-Doolan2014, Reference Fitzsimmons-Doolan2019) | Modifier collocates | Normed frequency/text | Language ideologies |

| Fitzsimmons-Doolan (Reference Fitzsimmons-Doolan2023, this volume) | Modifier collocates (extended set) | Normed frequency/text | Ideological discourses | |

| 4 | Berber Sardinha (Reference Berber Sardinha, Friginal and Hardy2021) | Noun, adj, verb lemmas | Normed frequency/year | Discourses |

| Berber Sardinha (Reference Berber Sardinha2022a) | Noun, adj, verb lemmas | Normed frequency/year | Discourses | |

| Kauffmann and Berber Sardinha (Reference Kauffmann, Berber Sardinha, Friginal and Hardy2021) | Lemmas | Normed frequency/text | Thematic dimensions of literary style | |

| 5 | Berber Sardinha (this volume) | Lemmas | Presence or absence/text | Discourses |

| 6 | Clarke, McEnery, and Brookes (Reference Clarke, McEnery and Brookes2021); Clarke, Brookes, and McEnery (Reference Clarke, Brookes and McEnery2022); and Clarke (Reference Clarke, Maci, Demata, McGlashan and Seargeant2024) | Keywords | Presence or absence of keyword/text | Discourses |

Design Sets 1–2 used associated word pairs (e.g., collocates, bigrams) as the lexical variable. Both Biber (Reference Biber1993a) and Crossley and Louwerse (Reference Crossley and Louwerse2007) counted associated word pairs per text, but because Biber’s collocations all had the same node, while Crossley and Louwerse’s bigrams had no shared lexical item, the constructs identified were unrelated (words senses [semantic] vs. dimensions of register variation [functional]). Berber Sardinha (Reference Berber Sardinha, Berber Sardinha and Veirano Pinto2019, Reference Berber Sardinha2020) used bigrams as the lexical variable, but each bigram had the same node (i.e., american or brazilian) and the location (R1) and word class (noun) of the associated lexical item was specified. Therefore, the identified construct was national representation.

The remaining studies (Design Sets 3–6) used single lexical units as the variables. The Fitzsimmons-Doolan studies all used counts/text of collocates of a node. The collocates were specified by a modifying or evaluative grammatical function, which supported the identification of ideological constructs (i.e., language ideologies, ideological discourses). The next set of studies use lemmas identified by frequency and dispersion criteria. Berber Sardinha (Reference Berber Sardinha, Friginal and Hardy2021) and (Reference Berber Sardinha2022a) included only lemmas tagged as nouns, adjectives, or verbs. These resulted in the identification of discourses that were thematic in nature. Kauffmann and Berber Sardinha (Reference Berber Sardinha, Friginal and Hardy2021) also used lemmas as the lexical variable, but because of the design of the corpus (all texts were written by the same author), the analysis resulted in the identification of dimensions of style specific to that author. In the case study presented in this Element, Berber Sardinha took into account the occurrence or nonoccurrence of content word lemmas to identify discourses in social media posts. Finally, the studies by Clarke used counts of the presence or absence of keywords per text which resulted in dimensions interpreted as discourses. Thus, LMDA offers a framework for identifying latent constructs conveyed through lexis. However, the LMDA framework has several points of design flexibility (i.e, variable selection, measure selection, and corpus design) that allow for nuance in the construct identified.

2.8 Broad Topical Application and Extension

In addition to the variety of lexically driven constructs that can be studied using the approach, this review of LMDA studies reveals a broad range of academic fields informed by these analyses. These include computational linguistics, discourse studies, historiography, language policy, lexicography, literary stylistics, music psychology, public health, public science, and register studies. This breadth suggests that as the approach becomes more developed and specified, interdisciplinary collaboration between corpus linguists and scholars from a host of academic fields should be productive.

Furthermore, across the current batch of LMDA studies, there is a clear pattern of analytical extension. That is, each of the more recent LMDA studies involves additional statistical analysis beyond the initial factor analysis. Four analysis types have been used for this extension. Once the LMDA has identified the latent lexically driven constructs, analyses of variance (e.g., ANOVAs) can be run to determine whether independent variables such as time, register, or source have a significant effect on the identified constructs (Berber Sardinha, Reference Berber Sardinha, Berber Sardinha and Veirano Pinto2019, Reference Berber Sardinha2020, Reference Berber Sardinha, Friginal and Hardy2021; Fitzsimmons-Doolan, Reference Fitzsimmons-Doolan2019, this volume). Provided the factor analysis has identified interdependent factors, cluster analysis can also be used with an independent variable (e.g., year) to identify aggregated units of that variable (e.g., historical era) informed by correlations among the factors/constructs with respect to the independent variable (Berber Sardinha, Reference Berber Sardinha2020, Reference Berber Sardinha, Friginal and Hardy2021, Reference Berber Sardinha2022a). If an LMDA has been conducted in addition to another MDA (e.g., TMDA or another LMDA), a canonical correlation analysis can merge the two MDAs to identify composite constructs (Berber Sardinha et al., Reference Berber Sardinha, Delfino and Collentine2022; Kauffmann & Berber Sardinha, Reference Kauffmann, Berber Sardinha, Friginal and Hardy2021). This extension can be used to conduct multimodal analysis (e.g., Berber Sardinha, Reference Berber Sardinha and Crosthwaite2024). These extension analyses are possible because LMDA assigns quantitative values to both the variables/construct and the observations (i.e., texts/construct). These values can then be input into the extension analyses. These analytical extensions represent an important contribution of LMDA as an approach to the study of constructs like discourse and ideology, which are usually identified through qualitative analysis that doesn’t provide a standardized result output that can be carried over into subsequent analyses.

2.9 Methodological Considerations

At least two important methodological considerations become clear in the survey of existing LMDA studies. The first is how to address zero counts in the data. The frequency of occurrence of many lexical items in language is less than that of grammatical items due to the Zipfian distribution of lexis (Biber et al., Reference Biber, Conrad and Reppen1998; Crossley et al., Reference Crossley, Varner, McNamara, Sardinha and Pinto2014). Therefore, unless adjustments are made, when lexical variables are used, especially in shorter texts, it is likely that the analyst will have an abundance of zero counts. Excessive zeros in datasets for factor analysis can be problematic (Keller et al., Reference Keller, Gray, Smith and Cotos2022; Xu et al., Reference Xu, Demmer and Li2020). The preceding studies have addressed this issue in several ways. For example, Fitzsimmons-Doolan (Reference Fitzsimmons-Doolan2014) applied a log transformation (log10 Xi + 1) to the normed counts of the data which reduced the number of zero counts and improved factorability. Crossley and Louwerse (Reference Crossley and Louwerse2007) used dispersion criteria. That is, only bigrams that were present in each observed text were included in the analysis, which eliminated zero counts. Frequency was another approach which addressed this issue. Berber Sardinha (Reference Berber Sardinha2022a) identified the most frequent lemmas in the data, which indirectly reduced the number of zero values. In fact, many of the studies applied some combination of the these approaches to handling the absence of lexical variables in observations (i.e., true zeros). Finally, Clarke et al. (Reference Clarke, McEnery and Brookes2021) used multiple correspondence analysis (MCA) instead of a factor analysis in their keyword co-occurrence studies. In MCA, the presence or absence of a variable/observation is used as a measure rather than variable count/observation and it is thus not hamstrung by zero counts.

As in LMDA, in NLP the problem of zero-inflated datasets is a common issue. To avoid this sparsity problem, NLP researchers use word vectors or embeddings. Word vectorization is the process of converting text data to numerical vectors, projecting words to a low-dimensional space and positioning related words close together while keeping unrelated words far apart. Generally, word embeddings comprise between 200 and 300 dimensions, resulting in each word being represented by a sequence of 200 or 300 numbers, rather than by the counts of those words in the actual texts.

Another methodological consideration evident across the studies is how to interpret poles when the lexical LMDA results in dimensions with highly loading positive and negative lexical variables. For each dimension in a factor analysis or MCA result, each variable in the analysis is given a factor loading. To interpret the factors as constructs (e.g., discourses), the variables with positive loadings above an a priori cutoff threshold (e.g., 0.3) are investigated qualitatively in the corpus. In the LMDA analyses conducted thus far, the factors often only have variables with positive loadings. However, on occasion, the factors have variables with negative factor loadings that exceed the cutoff threshold and the meaning of these poles of the factor must be interpreted as well. In traditional MDA, poles are understood as complementary of one another (Biber et al., Reference Biber, Conrad and Reppen1998). As Friginal and Hardy (Reference Friginal, Hardy, Berber Sardinha and Veirano Pinto2019) explain, “this distribution shows the relationship between two different groups of elements of the same kind, where one element is found in one set of environments and the other element is found in a nonintersecting (i.e., complementary) set of environments” (p. 147). In the LMDA studies, there is not consistency in how the negative poles are interpreted relative to the positive poles. Across the LMDA studies conducted thus far, approaches to interpreting factors with poles include labels that describe:

(1) opposites of a type (e.g., scripted vs. unscripted discourse; Crossley & Louwerse, Reference Crossley and Louwerse2007);

(2) differences of a type (e.g., speech as interaction vs. speech as pronunciation; Berber Sardinha, Reference Berber Sardinha2022a);

(3) different entities with no unifying connection (e.g., literate expression vs. revolution and the new nation; Berber Sardinha, Reference Berber Sardinha, Berber Sardinha and Veirano Pinto2019);

(4) one entity that accounts for complementary distribution (e.g., nativeness of skills mark group variation; Fitzsimmons-Doolan, Reference Fitzsimmons-Doolan2014).

Future specification of LMDA, then, might endeavor to provide guidance for interpreting results when two poles are identified.

2.10 Patterns in Lexis Reveal Latent Systems of Meaning

Taken together, the LMDA studies affirm that a number of distinct latent meaning systems are created through repetition and co-occurrence of lexical items and point to important moderating variables. These meaning systems range from word senses (Biber, Reference Biber1993a) to ideological discourses (Fitzsimmons-Doolan, Reference Fitzsimmons-Doolan2023) to national representations (Berber Sardinha, Reference Berber Sardinha, Berber Sardinha and Veirano Pinto2019), and are identifiable through linguistic analysis as demonstrated through these studies. Furthermore, these latent meaning systems have social validity, as established by the interpretability of the factors. Many of the research questions addressed by these LMDA studies – especially those that pertain to ideological discourses – are usually explored using techniques outside of corpus linguistics (CL). Thus, the application of LMDA affords the benefits of CL analysis (large datasets, inductive analysis, analysis of full texts) to be applied to these domains of inquiry. Though CL techniques such as collocation and keyness analysis can be used in the study of discourses (e.g., Gabrielatos & Baker, Reference Gabrielatos and Baker2008), LMDA extends the CL analysis farther into the process by grouping variables for interpretation, reducing (but not eliminating) subjectivity and increasing replicability. Moreover, a number of the LMDA studies addressed the issue of lexical distribution and register as a moderating variable either by testing related hypotheses (e.g., Crossley & Louwerse, Reference Crossley and Louwerse2007) or exploring the distribution of latent meaning systems by (Fitzsimmons-Doolan, Reference Fitzsimmons-Doolan2019) or across register (Fitzsimmons-Doolan, Reference Fitzsimmons-Doolan2023). This is perhaps not surprising given the focus on register in TMDA.

In addition, the LMDA approach, with its reliance on human interpretation of the texts where the statistical patterns are present, can yield insights that computational approaches with limited or no human interpretative engagement cannot. Computational approaches such as topic modeling, while proficient in processing large datasets and identifying statistical patterns, encounter significant limitations when tasked with revealing discourses because such approaches that rely on limited human text interpretation are restricted to surface-level patterns, whereas a focus on discourses requires consideration of historical, social, and political contexts, which are not immediately noticeable at the surface. For instance, the factor pattern for Dimension 2 from the first case study presented in this Element includes such lemmas as temperature, earth, scientist, warm, weather, warming, dioxide, atmosphere, decade, hot, ice, and age, which at the surface could be interpreted as indexing “global warming” discourse; however, by interpreting the actual texts where these items occur, it is possible to discern a more specific discourse that frames global warming as a form of alarmism promoted by climate activists. The positive pole of the dimension was therefore labeled as “activism alarmism” to reflect this underlying discourse.

2.11 Conclusion

In sum, the current body of scholarship using LMDA demonstrates that LMDA offers a versatile and broadly insightful method for analyzing large bodies of linguistic data to identify covert discursive and ideological meaning systems. In addition to modifications in corpus design, the lexical variables and their measures can be manipulated to identify a range of latent constructs. Moreover, LMDA can be applied to address research questions across a variety of academic fields of inquiry. Finally, in an age where the rate and scope of linguistic communication is unprecedented, LMDA can both identify and provide critical behavioral information about meaning systems harbored in language which are serving as catalysts for rapid social change.

3 How to Conduct a Lexical Multidimensional Analysis

In this section, we offer practical assistance with the technical aspects of LMDA, primarily focusing on conducting LMDA within a programming interface paired with statistical software. However, it is also possible to conduct the analysis using corpus software such as WordSmith (Scott, Reference Scott2016) and statistical software. Notes on the latter approach are provided throughout as well.

3.1 A Note on Corpus Design

Corpus design plays a crucial role in MDA, serving as the foundation for meaningful results. Due to space constraints in this Element, a comprehensive overview of corpus design is not possible here. Detailed discussions on this topic, including the critical aspect of corpus representativeness, can be found elsewhere (Biber, Reference Biber1993b; Egbert, Reference Egbert, Berber Sardinha and Veirano Pinto2019; Egbert et al., Reference Egbert, Biber and Gray2022; Berber Sardinha (to appear)).

This brief overview will only highlight the importance of text centrality in the construction of corpora for LMDA studies, where the emphasis is on treating each text as an individual observation unit. Essentially, MDA is a text analytical approach, centering on the analysis of text collections; as such, the text is the unit of observation. This is in contrast with other corpus linguistic approaches where the corpus itself is the unit of observation. In MD studies, statistics are conducted based on the count of texts where the variables occur, rather than the count of the variables across the whole corpus (Gray, Reference Gray2013).

In a corpus tailored for MDA, where texts are treated as the observation unit, each file should comprise a single full text. Metadata are often added to the corpus, containing information about each text detailing the context (e.g., register, source, date, etc.). In corpora not designed around individual texts as observation units, files might contain several texts or only text fragments, and metadata for each text may not be provided.

Because of the central role played by texts in an MD corpus, researchers must take into consideration how many texts will be collected and how they will be distributed across the corpus categories (registers, domains, time periods, publishers, social media platforms or users, etc.). The general goal is to collect representative samples for the different corpus categories (Biber, Reference Biber1993b; Egbert, Reference Egbert, Berber Sardinha and Veirano Pinto2019; Egbert et al., Reference Egbert, Biber and Gray2022; Berber Sardinha (to appear)). According to Egbert et al. (Reference Egbert, Biber and Gray2022), corpus representativeness can be understood as the extent to which a corpus enables researchers to make generalizations about the typical quantitative linguistic patterns found in a particular language or domain. As achieving representativeness is a complex undertaking, a thorough discussion is not within the scope of this Element; readers are encouraged to refer to Egbert, Biber, and Gray (Reference Egbert, Biber and Gray2022), Biber (Reference Biber1993b), and Berber Sardinha (Reference Berber Sardinha, Reppen, Goulart and Biberto appear) for a fuller treatment.

Considerations of corpus size form an integral part of the design criteria, which should be guided by the goal of ensuring representativeness. Typically, MD corpora are not designed to meet a particular word count total because, as mentioned, the unit of observation in MD corpus design is not the word, but the text. When determining the number of texts to include in a corpus, the guiding principle should be representativeness rather than an arbitrary figure. However, the requirements of statistical procedures such as factor analysis regarding dataset size must be taken into account. Factor analysis requires that the number of observations (texts) surpasses the number of variables (linguistic features) involved. Typically, it is advisable to have a ratio of at least five observations for every variable in factor analysis (Gorsuch, Reference Gorsuch2015). Based on this guideline, an LMDA study involving 500 lexical variables should aim for a minimum corpus size of 2,500 texts.

3.2 Corpus Processing

The following steps outline the procedures for corpus processing, essential for conducting an LMDA. Detailed descriptions of these steps and additional guidelines, together with computer code, are provided in the online appendix, available for further reference.

1. Lemmatization and part-of-speech tagging: If the lexical variable in the study is a lemma, all words within the corpus undergo lemmatization and are tagged for their part of speech. This step standardizes the text and facilitates subsequent analysis.

2. Frequency, keyness, and dispersion: The next step involves calculating the frequency, keyness, or dispersion of the lexical variables (or “features,” in MDA terminology).

3. Selection of features of interest: After the features have been quantified, specific words or sets of words are selected based on their relevance to the research objectives. For instance, one might focus on all nouns, words modifying particular nouns, or words that meet specific thresholds of frequency, keyness, and dispersion.

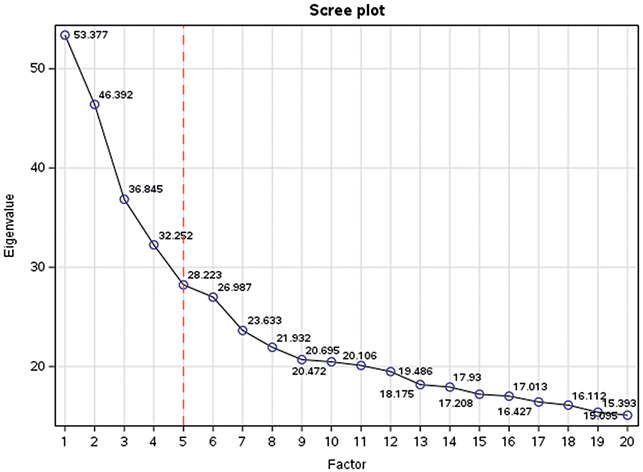

4. Factor analysis for identifying co-occurrence patterns: The selected features are then subjected to factor analysis, a statistical method used to identify sets of correlated words. Each factor is characterized by its loadings, which indicate the extent of co-occurrence among the words within the factor. The resulting factors are akin to those found in TMDA but consist of sets of words rather than grammatical features.

3.3 Factor Interpretation

Factor – or dimension – interpretation is an iterative and cyclical approach, where interpretive labels are proposed and refined to encapsulate the essence of the resulting factors. Interpretation begins by examining the lexical units that are highly loading on each factor to formulate initial hypotheses about the underlying discourses or ideologies. Analysts can initially draft temporary dimension labels based on the factor pattern, using the table listing the words loading on each factor. The next step involves consulting the texts themselves to test and refine these initial hypotheses. It is common for the analyst’s initial impressions about the labels to evolve significantly as they progress through the interpretive process.

A critical part of factor interpretation includes considering the scores of the texts and, if applicable, how these scores are distributed among different corpus categories such as time period, register, or author. Analysts must interpret a large and varied selection of corpus texts to accurately discern the underlying discourses or ideologies. There is no fixed number of texts that must be consulted; the guiding principle is to review as many texts as necessary, particularly those with marked scores on a given pole, to solidify the descriptive labels. When the analyst considers that the descriptive labels are stable when confronted with more texts, then this usually means that the interpretation can be concluded.