There is a need to improve current clinical approaches to faith in mental healthcare, in particular the role of faith in the choice of psychological treatment provision (therapy). The risks and problems of including faith in therapy have been extensively debated, and currently the position is unresolved, with the possibility of professional censure if the wrong balance is struck. Faith is a personal, emotionally charged issue. Conventional atheistic arguments that it is necessarily unhelpful to promote biased and possibly false ideas in a therapeutic intervention do not address faith's utility or salience. In this narrative review, we counter these arguments and give recommendations on implementing faith-informed therapies in clinical practice.

Philosophical aspects of faith and therapy

The Oxford English Dictionary defines faith as confidence, reliance or trust in another person or thing. Faith is also belief derived from testimony or authority, rather than empirical evidence, and this includes believing in religious tenets as truths. Originally, use of the word was exclusively religious, and that origin still colours its meaning. In the research literature, ‘faith’ is conflated with ‘spirituality’ or ‘religiosity’, particularly when discussing its behavioural correlates. So, while it relates to the dimension whose poles are credulity and scepticism, it also suggests a degree of awareness of something numinous, or possibly sacred, which both colours and justifies beliefs held through it. Despite its origins, faith is not now synonymous with religion, especially organised religions, which combine faith with many types of reasoning, including empirical scientific reasoning if the topic is deemed appropriate. Although many, if not all, societies have a deep-seated belief that correct faith can promote healing, the justification of therapies by referring to faith's foundations of belief, spiritual acceptance and authority are fundamentally opposed to empirical scientific method as conventionally understood. Faith-based therapies therefore require a philosophical justification applicable to both faith and science, if they are to be employed within modern medicine: three such justifications are possible.

The first, that faith-informed therapies are justified by their demonstrated efficacy, is discussed in detail below. However, this can only be a contingent justification for their inclusion, and it reduces faith to a therapeutic characteristic, which does not capture its nature.

The second, that we should be guided by patient preference, including faith preference, is currently the most generally accepted justification for them. However, we shall see that this is not necessarily easy to implement for all faith-related ideas and beliefs, and it also redefines faith in an inimical fashion, this time as merely something to satisfy patients’ wishes, albeit there are separate ethical arguments for routine inclusion of such qualities to encompass patient diversity.

A better alternative to these is the doctrine of double effect, that a single intervention may have two (or more) consequences of varying desirability. This is most commonly discussed in relation to end-of-life decisions. It is relevant here because a faith-informed approach might improve the quality of treatment of the patient, but also either modify their faith, or require the practitioner to adopt faith-informed values that are not shared, while non-therapeutic aspects of faith might provide sufficient alternative benefit to compensate for a therapeutically suboptimal treatment. The doctrine of double effect presumes that the intervention being considered is beneficial in some way: it thus attaches an empirical qualifier to faith when included in a treatment, rather than redefining the concept of faith away.

The psychology of faith

Since the late 19th century, the ‘lexical hypothesis’ has suggested that humanity's most important individual differences might be encoded as single words, and analysis of such descriptive words has enabled the construction of reliable and valid dimensions to account for individual differences and underpin their variable expression: traits. Psychoanalysts have long considered faith to be a trait. As a trait, it follows that its intensity in individuals is amenable to study by questionnaire, and several well-validated questionnaires exist, although they largely address faith from a Christian standpoint. Consistent with this interpretation, faith has both genetic and environmental associations which predict its expression in individuals, although methodological problems make its precise function and significance hard to determine. I intend to rely on Hood's proposal that faith, as a trait, has value because it introduces cognitive biases that contribute to social cohesion (Reference HoodHood 2009). While some of this is a trivial implication of aspects of the definition, such as reliance on authority, Hood has adduced psychological evidence to extend this idea to our experience of the numinous and sacred aspects of faith. This proposal subsumes the other major empirically based alternatives, threat avoidance (Reference Miller and StarkMiller 2002) and power relationships (Reference Collett and LizardoCollett 2009), as both theories presume that faith leads to a more cohesive society, more tightly focused on achieving the intended goal. Psychological theories which focus on the existential value of faith, rather than its social value, such as terror management theory (Reference Vail, Rothschild and WeiseVail 2010), also explicitly include socially cohesive psychological processes such as attachment. Convergent validation for this view has been provided by social and ethological research (Reference Sosis and AlcortaSosis 2003), and a ‘sense of connectedness’ is central to spiritual experience (Reference de Jager Meezenbroek, Garssen and van den Bergde Jager Meezenbroek 2012). As a trait which fosters social cohesion, faith also requires a cultural context for proper expression, and is not captured by personality traits alone. It seems likely that good social cohesion significantly improves the quality of our lives, thus reinforcing and maintaining the faith we share with those around us.

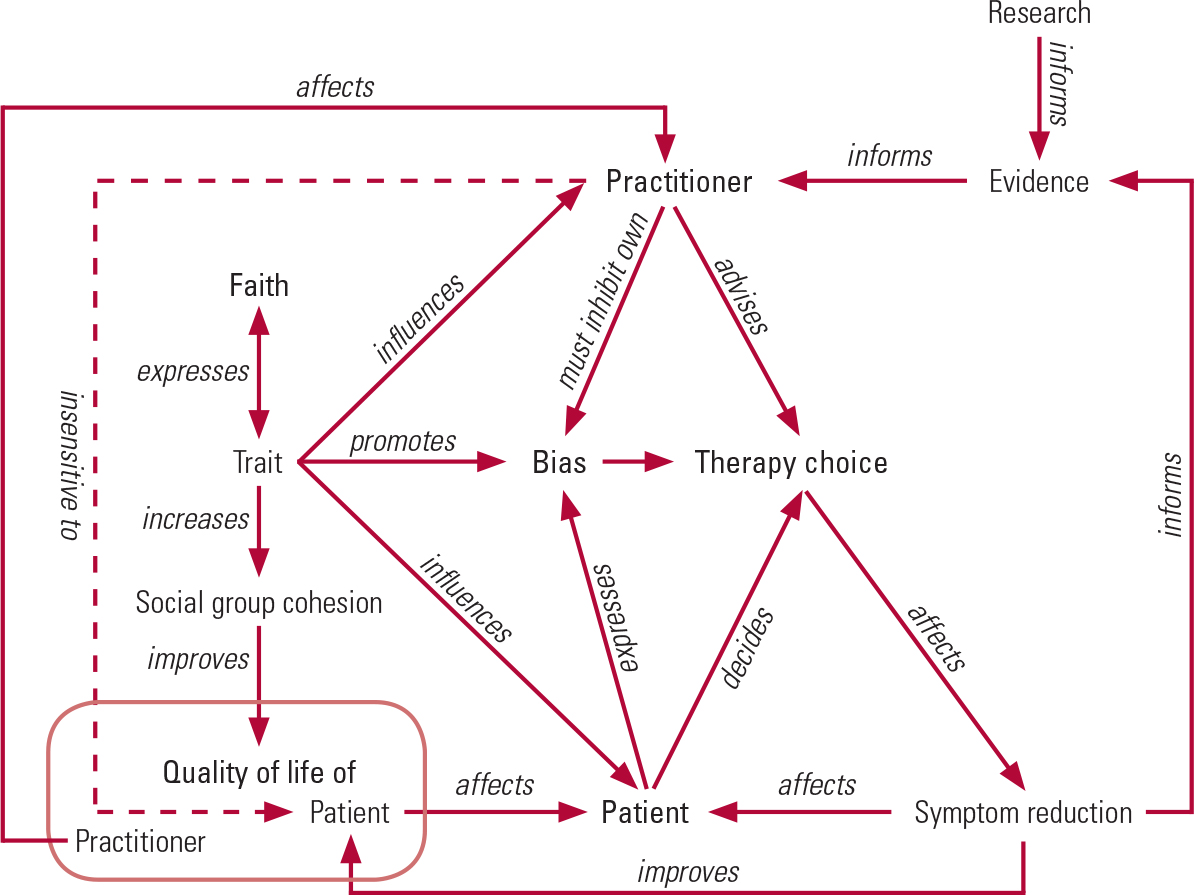

From this approach to the components of faith and its consequences one can infer how the resulting bias influences both practitioners’ and patients’ preferences for therapy, and might compete with empirically based judgements. This is set out graphically in Fig. 1, which also adumbrates how some pathways to bias might be modified.

FIG 1 The expression and moderation of faith-based bias affecting practitioner judgement and practice.

Figure 1 assumes that the explicit goal of the practitioner is to improve the patient's quality of life but, as the arrows show, the practitioner will also be interested in the quality of their own life: not a bad thing here, as a patient improving will provide professional satisfaction. The practitioner should advise a therapy based on evidence (shown on the right of Fig. 1) but, like the patient, the practitioner will have a trait for faith, which will bias the practitioner towards making recommendations congruent with their own beliefs and their social network (shown inside and to the left of Fig. 1). This bias would need to be inhibited in the practitioner (though not normally in the patient), but practitioners are much less sensitive to their patients’ quality of life (shown by the dashed arrow) than they are to symptom reduction.

The expression and moderation of faith-based bias affecting practitioner judgement and practice

If the function of faith as a trait is to introduce biases that support social cohesion within our culture, then fulfilling practitioners’ duty to respect their patients’ faith is not simple, or easy to achieve. For example, inappropriate teleological reasoning (reasoning from assumed intentionality: a key part of faith) may be readily induced even in those trained to avoid it (Reference Kelemen, Rottman and SestonKelemen 2013). The ability to mentalise, a key skill for practitioners, makes such biases more likely (Reference Banerjee and BloomBanerjee 2014). The underlying risk may relate to individual differences in inhibitory capacity (Reference Lindeman, Svedholm and RiekkiLindeman 2013), although this is moderated by cultural context as well as theistic belief. It is therefore unsurprising that practitioners’ use of faith-informed interventions is congruent with their beliefs, which also affect their theoretical orientation (Reference Walker, Gorsuch and TanWalker 2004; Reference PotvinPotvin 2012). Practitioners’ religious beliefs are stronger than those of their teachers in relation to their personal and professional lives (Reference Carlson, McGeorge and AndersonCarlson 2011). Practitioners’ religious beliefs promote engagement with those of their patients, particularly if congruent with their own (Reference Cummings, Ivan and CarsonCummings 2014), while training and experience within the context of a religious tradition increases the likelihood of choosing interventions related to that context (Reference Walker, Gorsuch and TanWalker 2008). Practitioners with strong faith-informed beliefs of any denomination are therefore at risk of encouraging change in faith among patients to more closely confirm to their own, even if formal conversion to the practitioner's faith does not occur: instead, the therapy acts as a ‘gateway’ for the patient to acquire a new set of values congruent with those of the practitioner. Consistent with this, patients practising mindfulness (in this context, a faith-informed therapy, as discussed below) report increases in spirituality mediated by their practice (Reference Labelle, Lawlor-Savage and CampbellLabelle 2015). Overall, however, practitioners tend to be strongly secular in their beliefs, compared with those they serve and, from the definition of faith this article prefers, secularism may behave as another variety of faith. There is evidence for a propensity among more secular practitioners to avoid or ignore religious issues in practice, despite advice and evidence that these may provide a resource for at least some patients (Reference Cummings, Ivan and CarsonCummings 2014), so committed secularists are as vulnerable to faith-informed biases as believers, although in the direction of ignoring appropriate faith-informed practice instead.

Faith, social cohesion and quality of life

Health-related quality of life (HRQoL) is a term used to capture the overall (non-financial) value of the impact of health changes on quality of life. It therefore includes faith-related issues among other components that may not be culturally congruent between patients and practitioners. This captures potential conflict between practitioners’ desire for social cohesion within their professional groups and congruence of values with their patients. Consistent with the accounts of practitioner faith discussed above, practitioners generally find it hard to respond to patients’ self-assessments of their HRQoL, irrespective of discipline or training, or to explore their patients’ spirituality even when professionally mandated to do so, especially if less religious themselves (Reference GreenhalghGreenhalgh 2009; Reference Frazier and HansenFrazier 2009). This suggests that practitioners’ attachments to their own social groups’ beliefs about such issues can withstand professionally mandated requirements to do otherwise, unless specifically addressed. An approach to overcoming this is described later in this article, in the section ‘Delivering faith-informed therapies’. It is also consistent with other research on more general outcome feedback, showing that practitioners’ attachments to their own evaluations (in this model, a form of faith) moderated their responsiveness (Reference de Jager Meezenbroek, Garssen and van den Bergde Jong 2012).

Moderating faith-based bias

Current systems of decision-making that integrate evidence and values stress the primacy of patients’ values and recommend rationalist, secular reasoning strategies to optimise value choice. Values-based practice (VBP) extends such ratiocination by emphasising the acquisition of skills that enable practitioners to negotiate assessment and treatments with their patients that include the latter's values and beliefs, as well as scientific evidence (Reference FulfordFulford 2011). The workbook developed for VBP recommends several behavioural strategies whose benefit is consistent with the research just reviewed. Cultivating awareness of all values relevant to a clinical decision, and refraining from individual selection of the ‘best’ value set from the therapist's perspective, counters the drive towards social cohesion underpinning the imperative salience of faith-informed judgements. Taking time in careful reflection reduces the risk of teleological error (e.g. that it is appropriate to offer mindfulness because it reduces suffering), and formulating decisions as part of a sufficiently diverse group protects against perceptual bias, as does reliance on external guidelines. The ability to measure faith in patients, and its association with their well-being, as part of routine outcome measurement, might help therapists to avoid unhelpful bias in faith-related decisions. Despite the general insensitivity to HRQoL measures discussed above, there have been promising results for oncology, where spiritual well-being scales have assisted in clarification of different dimensions of faith and their association with more general well-being and quality of life, including psychological well-being, and have generalised well across different faith groups (Reference Bai and LazenbyBai 2015). However, this methodology is still in development for mental healthcare.

Faith-informed therapies in practice

There are currently three main routes by which faith-informed approaches are entering mental healthcare.

As described in the literature, mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT) is an entirely secular technique, closely allied to cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT), with an empirical evidence base. No secret is made of the fact that it has been derived from Buddhist practice, although other religions (most obviously Hinduism, though Judaism, Islam and Christianity all have strong contemplative traditions) also practice mindfulness as part of their devotions. Many influential therapeutic practitioners of mindfulness are Buddhist, and consider it to be congruent with general healthcare ethics, rather than detachable from Buddhist practice. Courses involving mindfulness-based therapeutic techniques are taught in Buddhist centres, and university courses of mindfulness-based therapy include teaching Buddhism: both settings are seen as providing appropriate training. Some have extended the use of mindfulness to the inclusion of Buddhist psychology, and there is a plethora of books by mindfulness-oriented psychotherapists recommending a rapprochement with Buddhism.

Mindfulness has been taught without Buddhist background in effective psychotherapies targeted at borderline personality disorder, in particular dialectical behaviour therapy (DBT) (Reference LinehanLinehan 2014) and mentalisation-based treatment (MBT) (Reference Bateman, Bales and HutsebautBateman 2014). However, even here it has been theorised that the observed benefits result from a spiritual dimension that mindfulness has introduced (Reference Bennett, Shepherd and JancaBennett 2013).

Therapeutic prayer, mostly promoted by Christian and Moslem practitioners, has relied on a three-step religious engagement with patients. The first step is to assert that private prayer by the practitioner for the welfare of their patients is unexceptionable and an appropriate expression of compassion. The second is to argue that shared faith between practitioner and patient may be a help, rather than a hindrance, and may even be sought by patients, particularly from a religious minority. The third is an extension of the second, that joint prayer between practitioner and patient, or religious observance, may be an appropriate part of care (Reference KoenigKoenig 2008).

When faith-informed therapies are developed, a common approach is to construct therapies that combine religious and therapeutic elements within their delivery. Frequently, the therapeutic component is of known efficacy, and a secular version may be tested against a faith-informed version as part of the therapy's evaluation. Such approaches inform much of the research on the specific contribution that faith makes to therapeutic efficacy, which is discussed next.

Evidence for therapeutic efficacy of faith-informed therapies

Proponents of faith-informed therapies need to claim that there is evidence for the benefits of faith on sustaining mental health and well-being, both generally and in adversity. Although it has been claimed that the empirical case for the benefits of faith-based therapy is made, this is far from clear. Religious patients report adverse experiences associated with some faith-congruent spiritual interventions, especially joint praying (Reference Martinez, Smith and BarlowMartinez 2007). There is evidence for the apparent benefit being at least partly due to selection bias and, if not, being restricted to specific groups (Reference Balbuena, Baetz and BowenBalbuena 2014). Non-specific spirituality, such as that encouraged by mindfulness practices, has been associated with worse mental health and increased undesirable behaviour (Reference King, Marston and McManusKing 2013). Measurement of spirituality has conflated the concept with more general ideas of well-being, thus introducing a positive bias into much empirical assessment (Reference ChildsChilds 2014). A similarly circular bias is introduced when risky behaviours that are condemned by religions, but may not in themselves be harmful (e.g. having a number of sexual partners), are used as outcome variables. Healing touch (‘laying on of hands’) is a useful paradigm here, being a faith-informed therapy that requires no contaminating therapeutic effort from the patient. In a systematic review (Reference Anderson and TaylorAnderson 2011), the only adequately masked study found, in the absence of a nonintervention group, a difference favouring ‘mock’, rather than ‘genuine’, healing touch.

Another useful approach, mentioned above, is the direct comparison of ‘faith-informed’ and ‘secular’ versions of the same therapy. No difference has been found (Reference Worthington, Hook and DavisWorthington 2011), suggesting that any ‘added value’ for faith does not come from efficacy. A more recent contrary claim was based on an unplanned secondary analysis of a randomised controlled trial examining optimism (Reference Koenig, Pearce and NelsonKoenig 2015a), which was not supported by an earlier publication from the same study that focused on depression (Reference Koenig, Pearce and NelsonKoenig 2015b). Likewise, although empirical benefits of mindfulness for mental health have been established for depression, and especially depressive relapse, its effect is adjuvant to CBT when the two are combined (as in MBT): studies have found it inferior to other forms of CBT for some depressive subtypes or sleep disorder, and ineffective for, at least, social anxiety (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence 2014). Social constructs such as salutogenesis may be more important than spiritual ones in understanding its impact (Reference WijesingheWijesinghe 2013). Should a practitioner offer a faith-informed therapy other than mindfulness, the evidence for equivalent effectiveness is likely to be of lower quality than that supporting the secular comparison (Reference Paukert, Phillips and CullyPaukert 2011), which, under the doctrine of double effect, must be balanced against any spiritual benefit experienced by patients (Reference Worthington, Hook and DavisWorthington 2011).

None of the above caveats contradicts the finding that patients do report a separate, spiritual benefit from faith-informed therapies (Reference Worthington, Hook and DavisWorthington 2011) or that therapist-initiated, faith-informed values such as compassion, blame and moral responsibility may be essential for effective treatment in at least some cases (Reference PickardPickard 2011; Reference Braehler, Gumley and HarperBraehler 2013). Also, studies on religious coping have demonstrated that the effect of patients’ religious engagement on psychopathology may be positive or negative (Reference Pirutinsky, Rosmarin and PargamentPirutinsky 2011), suggesting that this is an important target for both assessment and intervention.

Delivering faith-informed therapies

Consideration of the empirical evidence just reviewed in the light of the doctrine of double effect suggests that simply avoiding faith-related values in therapy (as adopted by the majority of practitioners) is not sufficient. Similarly, basing a choice on no more than congruence with patients’ beliefs and preferences may not be in their therapeutic interest.

If changing spiritual belief is seen as a risk, then there is insufficient evidence to suggest that faith-informed therapies, other than mindfulness for depression, provide sufficient additional benefit to justify such a risk being taken. However, if such change is not a concern, then the doctrine of double effect suggests that faith-informed therapies of equivalent effectiveness become an option for discussion with patients, and could be potentially valuable for those patients whose religious engagement exacerbates or mitigates their psychopathology.

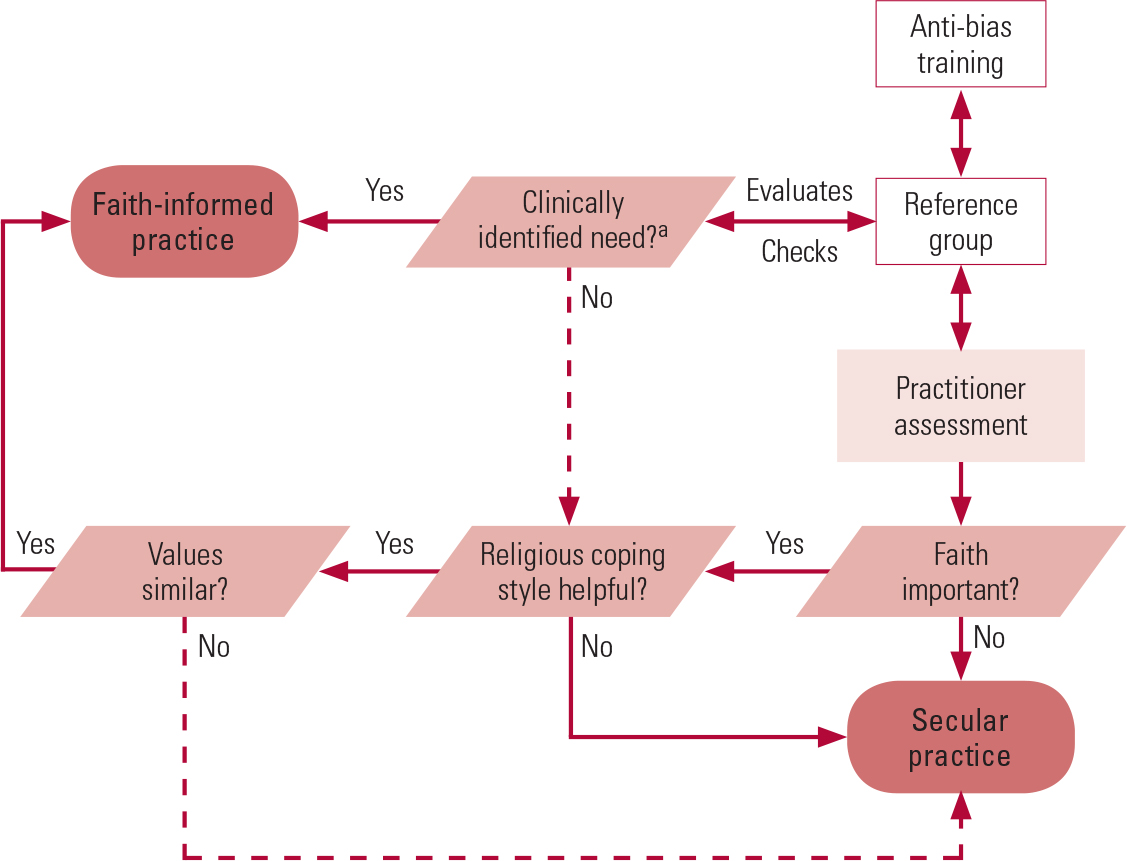

Figure 2 shows as a flowchart a faith-sensitive decision-making process for therapy choice and monitoring derived from the research just discussed. The flowchart begins with the practitioner asking himself or herself a very simple assessment question: is faith important for this patient? Reference CookCook (2015) gives a range of approaches to assess this. Given the evidence discussed above, the practitioner should also assess whether the patient's faith and coping style is a support or a risk to recovery, by deciding, for example, whether faith informs anxious or depressive ruminations. As Fig. 2 shows, faith-informed therapy is non-controversially indicated when faith is important to the patient, the patient's faith-related coping style is helpful, and the faith-related beliefs and values of therapist and patient are shared. If a patient's faith-related coping style is unhelpful, then the choice lies between a secular alternative, or – rarely – a faith-informed therapy designed to maximise alternative benefit and challenge the unhelpful coping style while minimising risk.

FIG 2 Decision-making process for faith-informed therapy.

a. Such as a seriously harmful coping style or quality-of-life problem.

There could also be occasions when a faith-informed therapy is indicated, but made difficult through an irreconcilable difference between the patient's and the therapist's values. To manage these potential risks, Fig. 2 suggests that practitioners should, from the outset, have access to a reference group of mental healthcare professionals who have received anti-bias training. The classic ‘Delphi’ system remains the gold standard for such groups: a detailed discussion is beyond the scope of this article, but its key components are aggregated, anonymised responses and the opportunity for multiple iterations. Although anonymity would be hard to achieve, both of the other criteria have been greatly facilitated by electronic communication, which also avoids the need for the group to schedule meetings. The use of a reference group, and HRQoL as well as symptom-based routine outcome measures, extends the application of ‘spiritually conscious care’ (Reference Saunders, Miller and BrightSaunders 2010) and descriptions of expected competencies (Reference CookCook 2015) by deploying techniques and strategies that specifically address practitioner bias relating to their patients’ faith, once it is elicited. Although the process appears complex and potentially resource-intensive, in practice most cases will not require detailed group discussion, though the individual practitioner will need appropriate training in the faith-informed therapy chosen.

Conclusions

We have seen above that a secular and empirical training will make it easy for mental health professionals to underestimate the importance of faith-informed values in the lives of patients, and they cannot presume to approach these issues without being affected by biases of their own. There is currently an unhelpful gap in the research: while it is possible to identify groups of patients whose faith interacts with their psychopathology, such patients have not been selected for trials of faith-informed therapy. Therefore, practitioners will need to have recourse to their own clinical judgement about the utility of faith-informed therapy to these patients when applying the flowchart in Fig. 2, and the failure to demonstrate additional clinical efficacy for faith-informed therapies may be unduly conservative.

Practitioners seeking training in faith-informed therapies face a dilemma. The research suggests that there is a role for these therapies, improving the quality of life of patients and meeting patient concerns that might otherwise not be addressed. However, much training in faith-informed therapies is provided within the relevant faith tradition, which has been shown to lead to biased decision-making. For such therapists, recommendations such as those in the learning objectives at the beginning of this article may prove useful in minimising the unavoidable influence of their training. Mindfulness is different, as it may be presented either as a faith-informed or a completely secular therapy. At present, much mindfulness-based therapy combines a secular presentation with a training heavily influenced by religious (Buddhist) philosophy. The potential for conversion or rejection for faith reasons is, prima facie, clear and unhelpful. A better separation between mindfulness training and Buddhism seems desirable: DBT and MBT show that this can be done with no loss of efficacy.

MCQs

Select the single best option for each question stem

-

1 The most important reason to assess faith in patients is:

-

a unresolved guidance about faith in therapy

-

b avoidance of secular bias

-

c salience for patients

-

d maintenance of social cohesion

-

e acceptability of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy.

-

-

2 The biggest risk to patients in using faith-informed therapies arises from:

-

a lack of efficacy

-

b a negative religious coping style

-

c conflict between therapist and patient

-

d changing the patient's faith

-

e impact on quality of life.

-

-

3 The best reason for using faith-informed therapies is:

-

a reliable evidence of efficacy

-

b patient acceptability

-

c positive change in symptomatology

-

d improvements in health-related quality of life (HRQoL)

-

e demonstration of therapist empathy.

-

-

4 The doctrine of double effect is most helpful in making decisions about faith in therapy because:

-

a it can be used in end-of-life care

-

b it is inherently free from bias

-

c it minimises risk to the patient

-

d it recognises patient preferences

-

e it explicitly values both faith and symptomatology separately.

-

-

5 Therapists can improve their practice when encountering faith by:

-

a making use of a skilled reference group in difficult circumstances

-

b taking time over faith-related decisions

-

c avoiding early compromise in situations where values seem to clash

-

d explicitly considering both quality of life and symptom change as separable treatment goals

-

e all of the above.

-

| 1 | c | 2 | b | 3 | d | 4 | e | 5 | e |

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.