Introduction

The reform of the international financial and tax systems has been at the center of recent global debates. The United Nations Secretary General has proposed a stimulus to achieve the sustainable development goals (SDGs) and broader suggestions on international financial reforms (UN, 2023a, 2023b and 2024a). Many of these proposals were endorsed in the political declaration of the High-Level Political Forum on Sustainable Development held in September 2023 (UN, 2023c, paragraph 38). There have been additional contributions in 2024 from the United Nations (2024a), in particular the recommendations of the Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC) Forum on Financing for Development (UN, 2024b), as well as from the Bretton Woods Institutions and the Group of 20 (G20) and academic institutions.Footnote 1 The United Nations Pact for the Future also included an important set of “Actions” to both enhance financing for development and adopt the associated relevant reforms in global governance (UN, 2024d).Footnote 2 These issues have also been at the center of the agenda of the Financing for Development Conferences since Monterrey in 2002, in those of the G20 and the Bretton Woods Institutions, as well as in recurring debates, including on the equitable participation of developing countriesFootnote 3 in international economic decision-making.

The celebration of the eightieth anniversary of the Bretton Woods Institutions in 2024, the G20 meetings in Brazil in 2024 and South Africa in 2025, and the negotiations on international tax cooperation going on in the United Nations constitute opportunities to make additional contributions to this agenda. In turn, the fourth Conference on Financing for Development that will take place in Spain in 2025 represents a great opportunity to enhance global cooperation in this area. It should follow the Addis Ababa Action Agenda agreed in the third Conference that took place in 2015 (United Nations, 2015). In this Conference, the United Nations should serve as a forum for consensus building – no doubt its historical strength – but the agreed financing actions should be in the hands of the appropriate financial institutions and other international financial arrangements.

In this Element, I refer to six elements of the global financing for development agenda, which are dealt with in individual sections: the role and evolution of development financing, the international monetary system, sovereign debt restructuring, international tax cooperation, international trade, and critical institutional issues. Although focusing on the international agenda, many of these issues have domestic implications for developing countries. The analysis covers both the nature of cooperation and recommendations on how to improve it. The proposed reforms would help implement recent global agreements, particularly the Actions of the United Nations Pact for the Future.

This Element is a revised version of a report prepared for the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs as a background for the forthcoming Conference on Financing for Development. I make use of multiple contributions to these debates, including my own, in several cases in collaboration with other authors. I thank Mariangela Parra-Lancourt and Shari Spiegel for her backing to this project. Support from Karla Daniela González has been crucial for the whole Element; Sections 1 and 3 borrow from joint papers written with her. I also appreciate the support of Juan Sebastián Betancur, Tommaso Faccio, Carlos Felipe Jaramillo, and Natalia Quiñonez for different sections.

1 Multilateral Development Banks

The system of multilateral development banks (MDBs) has its origins in the creation of the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD) at the Bretton Woods Conference of 1944, which is today part of the World Bank Group (simply World Bank in the rest of the Element). In terms of development, financing was enriched in later years with the creation of the International Development Association (IDA), the International Finance Corporation (IFC), and the Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency (MIGA). The system was later supplemented with the launch of several regional and interregional banks. Among the regional ones, the first were the European Investment Bank (EIB) and the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB), created in 1958 and 1959, respectively, followed later by the African Development Bank (AfDB), the Asian Development Bank (ADB), the Development Bank of Latin America (CAF),Footnote 4 and the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD). The interregional institutions include the Islamic Development Bank (IsDB), to which two more institutions were added in the mid-2010s: the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) and the New Development Bank (NDB) – the latter of the BRICS countries, but now with a broadening membership.

The main purpose of these institutions was to provide development financing and, in some cases, support regional integration – the latter being a particularly important task assigned to the EIB when it was created. The need for public sector institutions was clearly in the origin of the earlier MDBs due to the negative effects that the Great Depression of the 1930s had had on international private financing, except for trade. Such private financing began to be rebuilt globally from the late 1950s and began to reach a group of developing countries in the late 1960s and early 1970s but remained limited or very costly for most of them. Access became broader after the 2007–9 North Atlantic financial crisis,Footnote 5 primarily encouraged by the very expansionary monetary policies that were put in place by major developed countries’ central banks, which led to additional financing for developing nations that already had access to private international markets, as well as access to new countries that came to be characterized as “frontier markets.”

In terms of support for developing countries, the MDBs were designed to finance basic public sector programs in countries with little access to private markets – virtually all of them until the 1960s, except for trade financing — and on more favorable conditions in terms of cost and maturities for those countries that do have access to the said markets. Funding was initially for projects but has subsequently extended to programs and broader budget support. Aside from the public sector, the MDBs also started to finance private investments, an activity that, in several cases, was assumed by financial corporations or similar entities that are part of the respective groups.

Several institutions have preferential lines for low-income countries, including through specialized entities, such as IDA in the World Bank. This task is complementary to other direct mechanisms of support to these countries through official development assistance, coordinated by the Development Assistance Committee of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), and more recently by bilateral financing from other official countries – particularly from China.

We should add these historical functions, the countercyclical role that the MDBs must play, which is essential due to the procyclical behavior of international private financing toward developing countries –in terms of both availability and costs. Through their technical and financial support mechanisms, these institutions can help soften or reduce the negative impact of financial or economic crises, such as those triggered by COVID-19 and the restrictive monetary policies adopted by central banks in response to the increase in the global inflation generated by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022.

Beyond these functions, the World Bank expanded its role to include technical assistance to individual countries and the analysis of the situation and appropriate policies for developing countries. This “knowledge bank” function, as it has sometimes been called, began with the creation of the Office of the Chief Economist in the 1970s. It has gradually been assumed by several other MDBs. The World Bank also began to perform functions associated with guaranteeing investments in developing countries through MIGA and providing for dispute resolutions between investors and sovereign states through the International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID). In terms of public sector objectives, in recent years the emphasis has been added on financing international public goods, both global and regional, particularly mitigation and adaptation to climate change, supporting biodiversity and combating pandemics.

There are two basic models of MDBs. The first follows the original design of the IBRD, according to which there is a difference between borrowing and nonborrowing members, which are broadly speaking developing and developed countries, respectively. Everyone contributes capital and, in a certain sense, the subscribed but unpaid capital of the developed ones operates as a kind of financial guarantee, which helps to strengthen the institution and, therefore, its investment grade. The other model is the cooperative one. In this case, all countries are potential borrowers and equally share the risks faced by the institution. This is the model of the EIB and CAF but also of the interregional banks. Regarding the first of these models, it is important to mention that there is a complex debate about the “graduation” of countries, especially in the case of the World Bank. According to this criterion, above a certain level of income the country becomes developed and cannot borrow from the institution, although it could continue using a menu of options, especially the bank’s advisory services.

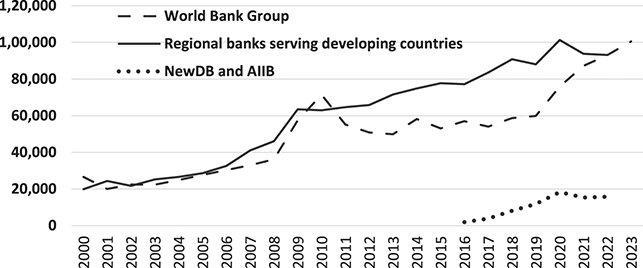

According to Figure 1, financing from the MDBs to developing countries has increased over the past two decades – as a proportion of world GDP, from 0.14 percent in 2000 to 0.20 percent in 2022. However, as pointed out below in this section, financing is considered limited relative to the resources that should help finance current global demands by developing countries. Traditional regional banks that offer financing to developing countries (i.e., excluding the EIBFootnote 6) have grown faster than the World Bank Group and surpass it in terms of loan commitments since the middle of the 2000s. Added to this is the growth of the two new banks, the AIIB and the NDB –particularly of the former – which was very rapid during the early years of its operation, in the second half of the 2010s.

Figure 1 Loan commitments by Multilateral Development Banks (million dollars).

Nonetheless, the World Bank continues to play the most important countercyclical role, as reflected in Figure 1 in the sharp increase in its financing during the North Atlantic and the COVID-19 crises, as well as the complex recent global economic conjuncture. The recent response was facilitated by the Bank’s capitalization in 2018. Furthermore, in recent years, this function was performed more strongly by the IDA than by the IBRD, thus benefiting in particular low-income countries, but also with a significant increase in financing to middle-income nations by the second of these institutions (Table 1). The only traditional regional banks that played a significant countercyclical role during the pandemic were the ADB and the EBRD, while the two Latin American and Caribbean banks were not very dynamic and the AfDB reduced its credit approvals. Among the interregional banks, the one that played a stronger countercyclical role was the AIIB.

Table 1 Loan commitments by Multilateral Development Banks (annual averages in million dollars)

| 2000−2004 | 2005−2009 | 2010−2014 | 2015−2019 | 2020−2022 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| World Bank – IBRD | 11,027 | 17,391 | 25,074 | 24,412 | 30,524 |

| World Bank – IDA | 8,896 | 11,060 | 16,822 | 20,118 | 34,707 |

| International Finance Corporation – IFC | 3,335 | 8,448 | 15,184 | 11,965 | 20,167 |

| Subtotal World Bank Group | 23,258 | 36,899 | 57,080 | 56,495 | 85,398 |

| Inter-American Development Bank (IADB) | 5,645 | 9,537 | 12,351 | 12,720 | 14,484 |

| Development Bank of Latin America (CAF) | 3,124 | 6,798 | 10,674 | 12,576 | 13,813 |

| African Development Bank (AfDB) | 2,190 | 3,916 | 4,702 | 7,029 | 4,944 |

| Asian Development Bank (AsDB) | 5,541 | 9,179 | 20,487 | 30,605 | 38,519 |

| Asian Infraestucture Development Bank (AIDB) | – | – | – | 2,037 | 10,444 |

| New Development Bank (NewDB) | – | – | – | 3,057 | 6,016 |

| European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) | 3,749 | 7,531 | 11,575 | 12,175 | 15,562 |

| Islamic Development Bank (IsDB) | 3,307 | 5,369 | 8,161 | 8,373 | 8,744 |

| Subtotal Regional Banks supporting developing countries | 23,555 | 42,331 | 67,949 | 88,573 | 1,12,525 |

| European Investment Bank (EIB) | 46,900 | 87,871 | 98,044 | 84,423 | 84,966 |

| TOTAL | 93,714 | 1,67,101 | 2,23,073 | 2,29,490 | 2,82,889 |

In terms of total financing, the World Bank has reached the size of the EIB, which was historically the largest development bank (see Table 1). Among the regional banks, the ADB is the largest, followed by the two Latin American and Caribbean banks (IDB and CAF), if we add the financing they provide. In the case of the interregional banks, the AIIB is now the largest.

In terms of relative support to different regions in relation to regional GDP, the World Bank provides the largest financing to Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia. This clearly reflects the priority of supporting the world’s poorest developing regions. Latin America and the Caribbean follow in relative importance. For its part, the support by regional banks is dominant in Europe, among other reasons due to importance of EIB, followed by Latin America and the Caribbean (Ocampo and Ortega, Reference Ocampo and Ortega2022).

From this analysis, the importance of continued dynamism of the MDB system emerges, for both long-term financing, now including the fight against climate change and protecting biodiversity, and supporting countries during economic crises. As we will see below in this section, their support to both mitigation and adaptation to climate change has been increasing, but it is still small in relation to financing needs, and very limited in the case of biodiversity activities. In relation to support during crises, it is essential that regional banks also play a countercyclical role, complementing that of the World Bank.

Aside from the UN documents mentioned in the Introduction to this Element, there are recent ambitious proposals on the MDBs coming from the G20 independent expert groups on capital requirements (G20, 2022 and 2023a) and on the agenda of this institution (G20, 2023b), as well as in the World Bank’s “Evolution Roadmap” (World Bank, 2022b, 2023b and 2024). The New Delhi G20 Summit also made ambitious proposals in this field (G20, 2023b, paragraphs 47 to 52).

There are three elements in common in these proposals. The first is that, apart from supporting the equitable and sustainable development of developing nations, MDBs must also finance the contribution of these countries to the provision of international public goods – both global and regional – notably the fight against climate change and the prevention of pandemics; the support of biodiversity is absent from these proposals but should certainly be added. The second is the need to have contingency clauses to face the vulnerability of countries associated with climatological and health phenomena and the effects of international crises. These clauses should allow debt service with these institutions to be suspended, and even partly or totally written off under critical conditions. The third is that there is a need to work more closely with the private sector, including to support its contribution to the provision of international public goods.

An essential theme of all these proposals is the need to have concessional credits or donations channeled through the MDBs. These benefits must also favor middle-income countries and create mechanisms that allow partial credit subsidies for the private sector to leverage their investments in the provision of international public goods. To make this possible, it is necessary to significantly increase official development assistance, since it is also essential to expand that received by low-income and vulnerable middle-income countries. Aside from concessional resources, MDB loans should be long term (thirty to fifty years), with more significant grace periods and lower interest rates. To manage the risks associated with exchange rate volatility, they should also lend more in the countries’ national currencies, based on the resources they raise with the placement of bonds in those currencies, which would also support the development of capital markets in developing countries.

To ensure concessional credits and donations achieve their full potential, we must consider the terms attached to loans and the policy conditions imposed on recipient countries. These conditions, which can address issues like climate change mitigation, biodiversity conservation, and pandemic preparedness, should be designed with a multi-pronged approach. A recent report by the Climate Policy Initiative advocates for a shift from project-by-project to program-based approaches by MDBs to drive systemic change (CPI, 2023).

The Paris Agreement of 2017 prompted most MDBs to adopt Paris-aligned practices. However, progress on Policy-based operations (PBOs) remains slow. PBOs offer financial support to developing countries in exchange for policy reforms. These reforms typically target areas like public finances, social programs, and key sectors like energy and agriculture. The goal is to strengthen recipient economies and maximize the effectiveness of development investments, ultimately reducing their reliance on aid. As highlighted by the World Resources Institute, MDBs can repurpose their PBO instruments to support climate-resilient development in countries facing debt burdens and climate threats (Neunuebel et al., Reference Neunuebel, Valerie and Hayden2023).

While short-term profit motives often drive private investors, their investments may not always align with long-term sustainability goals. MDBs can provide incentives and de-risk private investment through well-designed policy conditionalities through guarantees or insurance. This ensures that the resulting policies and investments contribute to the broader international public goods agenda. Discussions are ongoing regarding various financial management proposals to expand the relationship between MDB financing and their capital base.

In this regard, there are various financial management proposals to leverage the capital of these institutions and thus allow expanding the ratio between the financing they can provide and their capital base, maintaining in any case the standards that allow these institutions to continue having the best investment grade. In terms of expanding resources, the channeling of the special drawing rights (SDRs) issued by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) through the MDBs, which are already authorized to hold such assets, can contribute to increasing loans from these institutions. In any case, it is necessary to develop a specific instrument that preserves the role of SDRs as reserve assets, based on the experiences of IMF funds that already have such mechanisms (see Section 2).

To fulfill these functions, as well as the more traditional ones, the most important element is the capitalization of the MDBs in the necessary magnitudes. The capitalizations of the World Bank in 2018, as well as those of all institutions after the North Atlantic financial crisis, responded to this demand. However, a complex problem is the doubt about the commitments of major countries to capitalize these institutions today. In fact, in contrast to the North Atlantic financial crisis, where the G20 asked for the capitalization of all MDBs (G20, 2009), this has been limited in recent years.

The proposals differ significantly in terms of the magnitudes of the financing and capitalizations needed. An independent group of experts of the G20 proposed increasing the annual financing of these institutions to $500 billionFootnote 7 by 2030, a third of which would be in official assistance or concessional credits and the rest in nonconcessional credits (G20, 2023a). Given the amount of these institutions’ commitments in recent years (excluding the EIB), this means more than doubling the value of their loans. This would require capitalizations but could be supported by the implementation of the recommendations of a previous independent group of experts of the G20 that proposed a new capital adequacy framework for MDBs that would use new standards for risk tolerance, take into account their callable capital and preferred creditor status, and make a broader use of financial innovations that would allow them to share loan risks, among other instruments (G20, 2022).

The magnitude of additional financing proposed by the UN is more ambitious, as it considers the large requirements needed to achieve the SDGs. In fact, the Secretary General’s report on this issue highlighted the fact that the relationship between multilateral bank paid-in capital –and, thus, the financing they can provide – and the size of the world economy was significantly reduced in the 1960s and 1970s in the cases of the IBRD and the IDB, as well as other banks in later times (UN, 2023a, Figure 2). For this reason, the UN suggests returning to the 1960 levels, which would require increasing their loans by up to nearly $2 trillion, an amount closer to the financing gap for the SDGs (UN, 2023a, Table 2).

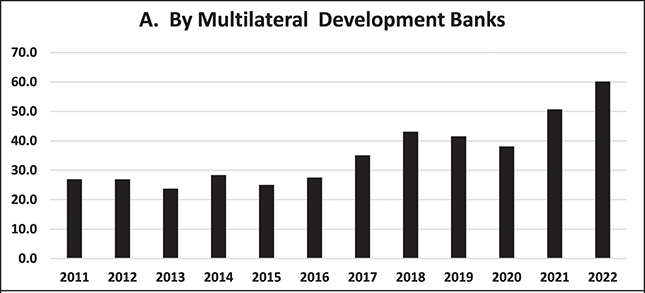

(A) By Multilateral Development Banks.

(B) From Official Development Assistance.

Figure 2 Climate financing (billion dollars).

Table 2 SDR allocations by level of development (in millions of SDRs)

| Allocations (in million SDRs) | Share in total allocations | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1970–72 | 1979–81 | 2009 | 2021 | 1970–72 | 1979–81 | 2009 | 2021 | |

| High income: OECD | 6,796 | 7,906 | 1,08,879 | 2,80,861 | 73.6% | 65.8% | 59.6% | 61.5% |

| United States | 2,294 | 2,606 | 30,416 | 79,546 | 24.8% | 21.7% | 16.6% | 17.4% |

| Japan | 377 | 514 | 11,393 | 29,540 | 4.1% | 4.3% | 6.2% | 6.5% |

| Others | 4,125 | 4,786 | 67,070 | 1,71,775 | 44.7% | 39.8% | 36.7% | 37.6% |

| High income: non-OECD | 17 | 127 | 3,588 | 34,958 | 0.2% | 1.1% | 2.0% | 7.7% |

| Gulf countries | 0 | 78 | 2,057 | 15,251 | 0.0% | 0.7% | 1.1% | 3.3% |

| Excluding Gulf countries | 17 | 49 | 1,531 | 19,707 | 0.2% | 0.4% | 0.8% | 4.3% |

| Middle income | 1,488 | 2,730 | 54,173 | 1,32,373 | 16.1% | 22.7% | 29.6% | 29.0% |

| China | 0 | 237 | 6,753 | 29,217 | 0.0% | 2.0% | 3.7% | 6.4% |

| Excluding China | 1,488 | 2,493 | 47,420 | 1,03,156 | 16.1% | 20.7% | 26.0% | 22.6% |

| Low income | 933 | 1,254 | 16,095 | 8,294 | 10.1% | 10.4% | 8.8% | 1.8% |

| Total allocations | 9,234 | 12,016 | 1,82,734 | 4,56,485 | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% |

A crucial issue is whether a significant increase in MDBs’ lending can be absorbed by developing countries, in particular by those with limited capacity to absorb new debt. This implies that the recapitalization of the banks would need to guarantee the funds for the concessional component of the contribution of these countries to the provision of international public goods, and include new instruments that facilitate private sector investments. They will also require the policies to manage overindebtedness, as discussed in Section 3.

Several of the proposals of the international institution are backed by academic and policy analysts. For example, Gallagher et al. (Reference Gallagher, Ram Bhandary, Ray and Ramos2023) argue that the main objective of the World Bank, other MDBs, and the IMF should be to guide worldwide capital flows toward growth paths in emerging markets and developing countries that are characterized by being socially inclusive, low carbon and climate resilient. This should be achieved in a way that also ensures fiscal and financial sustainability. On the other hand, Kharas and Battacharya (Reference Kharas and Battacharya2023) propose that the IBRD should triple its annual lending to around $100 billion per year with a total loan exposure of $1 trillion by 2030. This must be done, according to their proposals, by working closely with other stakeholders, including the private sector, and using hybrid capital and concessional financing to support both low- and middle-income countries.

It is also crucial that MDBs constitute a comprehensive service network. In the case of the World Bank, this includes its active participation in regional projects, in collaboration with relevant partners, ensuring a wide reach and effective implementation of development initiatives (World Bank, 2023b). Added to this is the need for all MDBs to work with the national development banks (NDBs) and other public institutions in developing countries (Griffith-Jones and Ocampo, Reference Griffith-Jones and Ocampo2018). This partnership is essential because public development banks finance between 10 percent and 12 percent of investment worldwide (UN, 2023a) – although there are significant differences in this regard among countries. Strengthening this collaboration would enable NDBs to become effective executors of multilateral programs, thereby enhancing their capacity to serve their local contexts. Furthermore, they could serve as vital channels of information for MDBs, providing insights into their countries’ specific financing needs, and ensuring that the support they provide is well aligned with the local priorities and conditions. By fostering such synergies, MDBs and NDBs can collectively drive sustainable development and economic growth in a more coordinated way, thus enhancing their impact.

In relation to climate financing,Footnote 8 commitments by MDBs have been growing since the mid-2010s, with a brief interruption in 2019–20 (Figure 2A). In 2022, they more than doubled the levels of financing they had provided in 2015 and have mobilized private finance concurrently. These efforts enabled them to achieve, with significant anticipation, the climate finance levels set for 2025 in the 2019 UN Climate Action Summit (MDBs, 2022). However, their capacity to crowd in private financing for climate change has been quite limited (IMF, 2022, Figure 2.6). Out of the total resources for climate financing, 63 percent was allocated for adaptation, in fact exceeding the 50 percent goal set for developing countries by UNFCCC (2022).

MDBs finance for biodiversity-related activities (both concessional and nonconcessional) has been increasing since the mid-2010s but is very limited: only $5.1 billion in 2021. In relative terms, it has represented 2.5 percent of their total financing, with only a few banks contributing significant amounts (OECD, 2023).

The amount of ODA provided for environmental protectionFootnote 9 has also increased since 2015 (Figure 2B). It has represented about one-fourth of support to African countries but a higher proportion in that is provided to other regions (OECD, 2024). However, in the specific context of climate, studies reveal that countries facing the highest climate vulnerability tend to receive a smaller proportion of climate-specific ODA in relation to their total ODA, with Latin America being a notable case (Development Initiatives, 2023).

In turn, the Green Climate Fund (GCF) operates as a financial mechanism under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). It became fully operational in 2015 with the aim of supporting developing countries in their efforts toward climate change adaptation and mitigation. The GCF has witnessed significant financial commitments, surpassing $12 billion, since its establishment and mobilized an additional $33 billion. This funding has been invested in climate projects, totaling over $40 billion, including cofinancing in more than 100 countries. As it embarks on its second replenishment, it has committed $12.7 billion in resources ($48.1 billion with cofinancing) for climate projects in developing countries.Footnote 10

The Global Environment Facility (GEF), established in 1991, also provides grants and concessional funds to developing countries for projects that address global environmental issues. Over the past three decades, it has provided more than $25 billion and mobilized $138 billion in cofinancing for more than 5,000 national and regional projects.Footnote 11 These projects span various critical areas, including biodiversity conservation, climate change mitigation and adaptation, land degradation, sustainable forest management, and the protection of international waters. The GEF’s support has been instrumental in driving environmental progress in developing countries, enabling them to implement innovative solutions and technologies that they might not have been able to afford otherwise. Furthermore, the GEF collaborates with a wide range of partners, including government agencies, civil society organizations, and the private sector, to ensure that the projects are comprehensive and sustainable. By working closely with these stakeholders, it helps to build local capacity and foster long-term environmental stewardship.

At the 2021 Climate COP26 in Glasgow, nations concurred that $100 billion per year for developing countries was necessary for a prolonged climate transition and to fulfill the global emissions target, explicitly including adaptation as a major issue for these countries. This goal replaced the climate finance commitment set in 2009 at the COP15 in Copenhagen, which aimed to mobilize the same amount for developing countries by 2020, a target that was only met in 2022 – that is, two years later than anticipated. This achievement will be primarily attributed to the augmented financing provided by the MDBs (Songwe et al., Reference 58Songwe, Stern and Bhattacharya2022).

In turn, at the COP27 held in Sharm el-Sheikh in Egypt in 2022, nations reached a consensus to establish a fund for loss and damage, which will offer assistance to countries vulnerable to the impacts of climate change. The specific arrangements for this fund were slated for discussion and consideration at the COP28 meeting in the United Arab Emirates, where it was finally agreed that the mandate focused on addressing loss and damage of developing countries that are more vulnerable to the effects of climate change, responding to their economic and noneconomic consequences.Footnote 12

Finally, there is a final instrument, the global green bonds, which actively involves private agents. In 2022, $487.1 billion of these bonds were issued, slightly lower than the peak of $582.4 reached in 2021, due to the market turmoil. That peak was reached after six years of very fast growth in emissions. The majority came from private sector issuers, accounting for 54 percent in 2022, slightly lower than the previous year’s 58 percent. Financial corporations played a significant role, contributing 29 percent of the resources, while nonfinancial corporations contributed 25 percent. European corporates were responsible for nearly half of the private sector’s green bond issuance (Climate Bonds Initiative, 2022).

In any case, current climate financing is far below existing estimates of the funds needed, which is between $2.2 trillion and $2.8 trillion annually in emerging markets and developing countries by 2030, according to the International Energy Agency.Footnote 13 Furthermore, given the conditions faced by several developing countries in relation to debt (see Section 3), it is unclear whether they can assume further commitments as borrowers, notably given the magnitude of the resources required.

There is also the view in some circles that the fragmentation of the financing mechanisms should be reduced, concentrating the funding in less institutions. The financial architecture for climate is indeed becoming complex and unwieldy. Putting the bulk of resources in less places, with common processes and requirements, would be positive for countries that have to navigate today too many windows. Putting the bulk of this money as capital contribution in MDBs would help multiply financing by the usual leveraging of the balance sheet, as every dollar in capital becomes $4–5 in loans. By contrast, the financing for GCF is one-to-one.

The system of MDBs has been a cornerstone of development finance for decades. Its growing diversity, with new actors like the AIIB and NDB, reflects the evolving development landscape. Looking ahead, MDBs face crucial opportunities. Financing the fight against climate change demands innovative solutions. They can mobilize additional funding and leverage private investment through well-designed policies that incentivize sustainable practices. Similarly, they can bolster economic resilience in developing countries by providing timely support during crises. However, this requires a balance between increased lending and ensuring developing countries’ long-term debt sustainability.

Several proposals aim to address these challenges. Increased capitalization, innovative financial instruments, and collaboration with the private sector can all expand lending capacity. Additionally, stronger partnerships with NDBs can improve project implementation. Finally, streamlining the climate finance architecture can enhance efficiency and impact. By seizing these opportunities, MDBs can remain a powerful force for sustainable development. They can mobilize resources, foster innovation, and promote good governance, paving the way for a more prosperous future.

2 The International Monetary System

The current international monetary system is the result of significant changes triggered by the 1971 crisis, when the United States decided to devalue the exchange rate of the dollar vis-à-vis gold. This decision marked a pivotal moment, as the dollar-to-gold standard had been an essential element of the system agreed in 1944 at Bretton Woods. However, by 1971, pressures from trade imbalances and inflation led to the United States unilaterally severing the dollar’s link to gold, putting an end to the Bretton Woods system (Eichengreen, Reference Eichengreen2008; Ocampo, Reference Ocampo2017).

The decision of the United States initiated a long period of negotiations among major economies to devise a new framework for the international monetary system. These negotiations were characterized by temporary measures as countries navigated the transition from a fixed exchange rate regime to more flexible exchange rates (Eichengreen, Reference Eichengreen2011).

The pivotal moment came in 1976, when the basic agreement was ratified at the IMF meetings in Jamaica, known as the Jamaica Accords. These meetings served to amend the IMF articles to legalize this agreement, as well as existing practices. This agreement officially recognized the reality of floating exchange rates, where currency values are determined by market forces rather than being pegged to gold or any other standard (Ocampo, Reference Ocampo2017).

The basic elements of this system are the following: (i) There may be multiple reserve currencies, but in practice the fiat dollar has been dominant, followed with a significant margin by the euro and in modest magnitudes by other currencies; (ii) countries can choose the exchange system that they consider most appropriate, which in practice has meant a system of floating rates among the main currencies; (iii) there is a commitment not to “manipulate” the exchange rate, but that concept has not been precisely defined; (iv) countries can continue to regulate capital flows, although they have been liberalized in an important part of the world; and (v) the IMF supervises the countries’ macroeconomic policies according to Article IV of the agreement. Added to this, as we will see, is the creation and redesign of credit lines, largely during crises in different parts of the world economy. It is worth adding that, contrary to the visions set in the Bretton Woods agreement, macroeconomic coordination is largely done outside the IMF, through ad hoc groups, initially the OECD-G10, later the G7 and, since the North Atlantic financial crisis, the G20.

An important additional element of the new system was the decision of most European countries to create a regional system, reflecting their preference for stable exchange rates to enhance intra-regional trade. For several developing countries, the transition was not drastic, as they had already been employing other forms of exchange rate flexibility, such as crawling pegs and managed floats (Ocampo, Reference Ocampo2017).

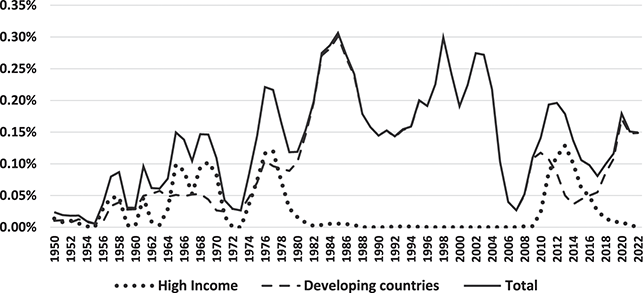

Unlike development financing, international monetary reform has not been central to recent global debates. For a long time, the most interesting proposal in terms of reforms is the possibility of using SDRs more actively. This is the reserve currency issued by the IMF itself, which was created in 1969 but has been an instrument with very limited use. According to existing agreements, SDR allocations must be made based on long-term, global needs and to complement the supply of other reserves. There have been four historical allocations: the initial one, in the early 1970s, and those in 1980, 2009, and 2021 – the last two in response to international crises. The 2021 allocation took place after the failure to agree to the issuance in 2020 due to the objection of the United States, although it was ultimately adopted for a sum greater than that initially proposed – the equivalent of $650 billion. Due to the composition of IMF quotas, which is the criterion for allocation to different countries, the bulk of the issuance favored high-income countries (Table 2).

Various analyses on this matterFootnote 14 have made interesting proposals. First, they indicate that SDR allocations could be much higher: at least $200 billion a year and even up to $400 billion. It would be advisable, in any case, that they should continue to have a countercyclical nature and be proportional in the long term to the demand for international reserves. For more active use, the main reform that could be adopted is to eliminate the IMF’s dual accounting, which currently separates SDRs from the current operations of the Fund. Once this duality is eliminated, the unused SDRs could be considered as deposits of the countries in the IMF, which this entity could therefore use as resources available for its credit operations.

An additional possibility would be that they could be deposited as accounts in IMF Trusts, in MDBs or in multilateral funds to promote certain international objectives. In that regard, two funds have been created by the IMF in recent years: one for balance of payments problems in low-income countries (Poverty Reduction and Growth Trust) and another to support prospective longer-term balance of payments stability for low-income and vulnerable middle-income countries, including the management of risks associated with climate change and pandemics (Resilience and Sustainability Trust). Both have benefited an increasing group of countries. In both cases it has been necessary to adopt mechanisms that guarantee the liquidity of the SDRs, so that they continue to have the character of a reserve currency.

In turn, in May 2024, the IMF’s Executive Board allowed the use of SDRs for the acquisition of hybrid capital instruments issued by prescribed holders (notably MDBs) subject to some constraints to manage liquidity risks. The main objective is to increase the capacity of credit operations of some MDBs for development purposes. The effectiveness of this measure is yet to be assessed, as many IMF members face legal and operational constraints to engage in this type of operations.

There are several other specific proposals aimed at favoring developing countries with the use of SDRs. An important one is to include an additional criterion to the existing quota system used for SDR allocation. This could be based on the countries’ per capita income or their demand for international reserves, ensuring that countries with greater needs receive more substantial support. Although this proposal has been on the table for a long time, reaching an agreement on such a criterion has proven to be challenging. Another possibility is that contributions to regional reserve funds could be considered as a criterion for the allocation of SDRs. This would encourage the establishment and strengthening of regional reserve funds, providing a more localized and tailored approach to financial stability. Such funds could act as buffers against regional economic shocks, thereby enhancing the financial resilience in developing countries. This proposal is discussed more extensively in Section 6.

Crisis prevention and management are clearly complementary topics. Preventive actions include prudent macroeconomic management, which is the focus of Article IV consultations, as well as maintaining an appropriate level of international reserves. The accumulation of reserves is required to manage the stronger cyclical shocks developing countries face, but generates significant costs for them. Despite this, there is no mechanism in place to compensate for these costs. Developing countries, therefore, face a disproportionate burden in their efforts to safeguard economic stability. Addressing this imbalance requires innovative financial instruments and international cooperation to ensure that the global financial architecture supports all countries fairly.

The management of shocks from the capital account is a particularly critical issue for developing countries that have access to international private financing, given the procyclical behavior of private capital markets – in terms of both availability and costs (risk margins). For this reason, the possibility of regulating capital flows is an essential issue for these countries, which, in fact, do so more broadly than developed countries. In turn, commodity-dependent economies face the volatility of international prices, which then require specific instruments to manage those fluctuations, a topic to which I will return in Section 5.

In 1997, there was an initiative to establish the convertibility of the capital account as a requirement for IMF members, in addition to the convertibility of current operations that was agreed at Bretton Woods. However, this proposal, which was presented at the institution’s annual meeting in Hong Kong, was not adopted. In the opposite direction, after the North Atlantic crisis, the IMF approved the “institutional vision” on capital account management, which points out that liberalization is not always positive and, therefore, that the management of capital flows may be convenient under certain circumstances – although temporarily, according to this vision (IMF, 2012). This decision was adopted after multiple studies that pointed out the risk of capital flow volatility for developing countries, including several by the Fund’s technical teams.Footnote 15 This institutional vision remains in place.

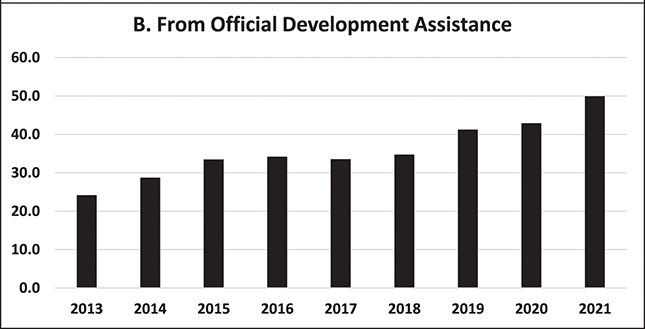

In terms of the use of IMF financing, there have been significant changes through time. The magnitude of loan disbursement from this institution as a proportion of the world’s gross domestic product (GDP) is summarized in Figure 3. Until the 1970s, high-income countries were the most important recipients of the credits of the organization. The situation changed radically in the 1980s, when developing countries became the main claimants. They have continued to be so, except temporarily after the North Atlantic crisis, when some European countries again demanded significant resources from the Fund.

Figure 3 IMF lending relative to world GDP.

The IMF financing has had a clearly countercyclical behavior. The historical peaks occurred during the Latin American debt and the Asian crises, when they reached the equivalent of 0.3 percent of world GDP in both cases. The maximum amounts reached during the two crises of the twenty-first century – the North Atlantic crisis and the COVID-19 pandemic – led to lower demands: a maximum slightly lower than 0.2 percent of world GDP. However, the peak for high-income countries in the years following the North Atlantic crisis was similar to the historical highs for that group of countries. In contrast, the amounts demanded by developing countries during the COVID-19 pandemic and recent years were much lower than the levels reached during the Latin American debt and Asian crises.

The credit lines have been improving over time. The main recent reforms were adopted in 2009–10, again after the North Atlantic crisis. They included (i) the duplication of all existing lines; (ii) the creation of several contingency lines – the flexible credit and short-term liquidity lines – both without conditionality for countries with strong macroeconomic fundamentals, and the precautionary and liquidity lines, to which a broader group of countries have access, but with conditionality; and (iii) more flexible lines for low-income countries.

The amounts approved under the flexible credit line (FCL) represent a high share of recent IMF program commitments – up to half in some years. Latin American countries have been the ones that have used this line the most: Colombia and Mexico first and Chile and Peru more recently; Colombia is the only one that has made partial disbursements of the approved resources. Their most important element is that they authorize resources that are not necessarily disbursed by countriesFootnote 16 and, in a sense, represent a type of overdraft facility that gives a positive signal to markets and reduces the need to accumulate international reserves.

In recent times, changes in credit lines have been less important. For low-income countries, interest payments were eliminated in 2015. To face the COVID-19 pandemic, an emergency credit line was approved without conditionality, but for small amounts – up to a country’s quota. It was widely used by seventy-nine countries. Although the proposal to approve a swap line was unsuccessful, a short-term liquidity line was created but only for 145 percent of the quota, significantly less than the average use of the FCL. Chile was the sole country to use it, but it quickly reverted to using the FCL. In October 2023, the Executive Board implemented improvements in this area, allowing eligible members to concurrently use the flexible and short-term liquidity lines on a prolonged basis for up to 400 percent of their quotas. Additionally, members can access the FCL up to 200 percent of their quotas on a persistent basis, and on a larger scale temporarily but with an ex-ante exit strategy (IMF, 2023b).

In any case, given the financing needs of low- and middle-income countries, significant additional IMF lending is required. According to one estimate, a 127 percent increase in quotas is needed to cover the external crisis finance gap of these countries and 267 percent to cover their short-term gross external financing needs (Mühlich and Zucker-Marques, Reference Mühlich and Zucker-Marques2023). These requirements are much higher than the 50 percent quota increase that has been approved. Improvements in the contingency credit lines must be a priority, as they are essential crisis prevention tools and efficient alternatives to reserve accumulation. Another option would be to develop more automatic and unconditional liquidity provision mechanisms that would be available under global shocks and whose objective would be to mitigate contagion, by revisiting, for instance, the Global Shock Window or the Global Shock Activation Mechanism. An interesting complementary proposal recently made by CLAAF (2023) is to create a new IMF instrument of international liquidity provision for emerging and developing economies: an Emerging Market Fund (EMF). This instrument would serve to mitigate the unwarranted effects of systemic liquidity crises on these countries, which are reflected both in the volumes as well as sharp increases in the costs (risk margins) during these crises. The most important feature of the EMF would be its capacity to intervene in a basket of emerging markets bonds during systemic liquidity crises, with the goal of stabilizing those markets. Although a novel proposal for emerging markets, these types of interventions have been widely used by central banks in advanced economies, such as the Federal Reserve and the European Central Bank during times of financial turmoil. The main reason is that, unlike emerging markets, advanced economies have the ability to issue reserve currencies that are widely traded around the world. The EMF seeks to address this fundamental asymmetry between countries that issue reserve currencies and countries that do not. Therefore, it would also help reduce the costs that emerging and developing countries face by the need to accumulate large amounts of foreign exchange reserves to manage the volatility and procyclical pattern of international private capital flows affecting these countries.

In October 2024, there was a decision to reduce the charges, surcharges, and commitment fees affecting the large lending operations of the IMF through the General Resources Account. However, in this regard, the group of developing countries in the Bretton Woods Institutions, the G24, has proposed the suspension of the surcharges for countries with severe balance of payments problems and even a significant permanent reduction in surcharges or their elimination (G24, 2023). These potential reforms aim to provide relief, given the more protracted balance of payments and fiscal needs generated by the higher interest rates that have characterized the world economy in recent years. Given the Fund’s balance sheet has strengthened considerably in recent years, the expectation is that considerable support to vulnerable members will be agreed.

The historical behavior of financing to developed versus developing countries is reflected in the evolution of conditionality, which is the most controversial issue of IMF programs. When high-income countries were the main debtors, it was strictly macroeconomic. With the predominance of loans to developing countries, conditionality became more structural, including issues such as privatizations of public sector firms and external trade liberalization. The conditions imposed during the Asian crisis generated strong opposition, which was reflected in a 2002 agreement to return to the principle of macroeconomic conditionality. This principle was expanded in 2009, when it was determined that failure to meet structural goals does not prevent the disbursement of credits. In contrast, in 2018 a modification was approved according to which the IMF can establish conditionality based on governance standards and the fight against corruption, if these factors have macroeconomic impacts. This is a complex criterion because it can lend itself to subjective analysis, even with political elements, and the IMF has no expertise in these areas.

The inclusion of governance is part of a broader set of agreements reached since 2012 that have also included standards on social spending, gender equality, climate change, and digital money. The principle is that they should be considered in surveillance and lending programs to the extent that they have macroeconomic effects – that is, on the balance of payments or on economic and financial stability. According to a recent task force on climate, development and the IMF, the mainstreaming of climate change into IMF activities should deepen, including taking into account in surveillance the macroeconomic implications of financing the climate transition, and finding an appropriate way to analyze the short-term fiscal consolidation versus the long-term resource mobilization needed (TCDIMF, 2023). Whether it should finance climate change through its own funds, including the existing Resilience and Sustainability Trust, is more questionable, as it may be better that such financing be in the hands of funds managed by the MDBs.

In June 2024, the Independent Evaluation Office (IEO) released its analysis on whether the new governance and other standards has implied an excessive expansion of the IMF mandate, to what extent their links with macroeconomic stability are sufficiently clear, and whether the Fund has the means to analyze these issues or should collaborate with other organizations (IMF-IEO, 2024). The evaluation found that the expansion of the scope of the Fund’s mandate was in line with its legal framework and the membership’s call. However, the implementation of such expansion has not been consistent with the existing resources and expertise. Furthermore, the discussions to broaden the scope of the mandate have lacked a holistic and strategic approach; instead, it has come in the form of a piecemeal and ad hoc set of reforms. The IEO thus recommended that the IMF should prioritize its work in the context of a world economy that has been facing recurrent macroeconomic shocks and is becoming increasingly multipolar, and that the Executive Board should adopt a Statement of Principles to strengthen the collaboration with relevant partners with expertise and comparative advantage in those areas.

The size of the Fund must, of course, continue to reflect the growth and evolving dynamics of the world economy. In this regard, the IMF Board has recommended that member countries increase total quotas by 50 percent. This recommendation aims to ensure that the Fund has sufficient resources to effectively support its member countries in times of economic distress and to maintain global financial stability. In December 2023, the IMF Board of Governors reached an agreement on this quota, underscoring the commitment of the international community to bolster the Fund’s capacity. Country authorities were expected to provide their consent for this increase by November 2024, paving the way for the implementation of this critical enhancement of the Fund’s resources.

However, the debate on the distribution of quotas to better reflect the relative economic contributions and weights of different economies in the global economy was postponed. The redistribution process is a complex and politically sensitive issue, as it involves adjusting the voting power and financial contributions of member countries based on their current economic standings. This realignment is essential to ensure that emerging economies that have grown significantly over the past few decades have a greater voice and representation in the IMF’s decision-making processes. The negotiations for this quota redistribution have been postponed to 2025, allowing more time for member countries to reach a consensus on the new allocation framework. This delay highlights the challenges inherent in balancing the interests of established and emerging economies within the global financial architecture.

The upcoming negotiations will be crucial in addressing these disparities and fostering a more inclusive and equitable IMF governance structure. Successful redistribution will not only enhance the legitimacy and credibility of the institution but also ensure that it remains responsive to the needs of a diverse and dynamic global economy. As such, these discussions are anticipated to be a focal point of international economic diplomacy in the coming years.

A notable difference with the system of MDBs is the weakness of regional institutions in the international monetary system. The largest in relation to regional GDP is the European Stability Mechanism, created in 2012 as a response to the sequence of the North Atlantic and Eurozone crises. It is followed by the Chiang Mai initiative, agreed between the countries of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), China, Hong Kong, the Republic of Korea, and Japan. It was born in 2000 after the Asian crisis and expanded significantly in 2009, when its currency swap lines were expanded and multilateralized, and were expanded again in 2012. They are followed by the most modest Latin American Reserve Fund, born in 1989 as a successor of the Andean Fund, which had been created in 1978, that now has nine members.

On top of the IMF and regional arrangements, the Bank of International Settlements has been a historical mechanism for short-term financing among its member central banks, and several of these institutions have created swap facilities for their partners. The swap facilities of the US Federal Reserve were particularly important during the North Atlantic and the COVID-19 crises, and to a lesser extent in 2011–12 to support some European countries facing debt crises. The Central Bank of China has also been increasingly active in recent years in the creation of swap facilities.

From this analysis, several recommendations emerge for the reform of the international monetary system. The first is to give the SDRs a much more active role within the system, preferably with a development perspective. The most important reform is, as already indicated, to eliminate the IMF’s double accounting and consider unused SDRs as country deposits in the Fund. This can be complemented with deposit of SDRs in the MDBs, or in specific IMF trust funds, to expand the supply of credit to developing countries. Recently, the IMF has approved a mechanism to channel SDRs to MDBs through hybrid capital instruments.

The second recommendation is that the Fund should continue to review and enhance its credit lines, particularly by expanding its contingency facilities, which serve as a crucial instrument for crisis prevention, and that it should reduce or eliminate the surcharges on its lending operations. In the case of the FCL, it is advisable to allow it to be permanent. Additionally, other contingency lines, such as the short-term liquidity line and precautionary and liquidity lines, must be improved to better serve the needs of member countries. In turn, as already pointed out, the Fund could create liquidity mechanisms that would allow interventions to manage adverse cyclical swings in international private capital markets and mitigate contagion. The primary advantage of all the contingency and liquidity facilities is that they will reduce the need for developing countries to accumulate large amounts of international reserves to manage capital account fluctuations and commodity price shocks. As a complement, the institutional vision on capital account regulations must remain in force and even refined to provide more precise guidance and support to member countries navigating complex financial landscapes. This should include the elimination of the view that these regulations should only be temporary.

Third, conditionality must remain strictly macroeconomic and must continue to be subject to rigorous review, as it is still considered the main stigma associated with the Fund’s financing. This must include the review of conditionality standards based on governance, anti-corruption measures, and other areas that were adopted over the past decade. Ensuring that these conditions are fair, transparent, and appropriately tailored to the unique circumstances of each member country is essential for maintaining the legitimacy and effectiveness of the Fund’s assistance.

Fourth, the increase in Fund quotas that was approved in late 2023 is a significant step forward and must take place as planned; the reforms in the share of member countries’ quotas should be reviewed in 2025, as agreed. These reforms should accurately reflect the economic size of different countries in the world economy and increase the voice and participation of developing countries in international economic decision-making. This is a vital institutional issue that will significantly influence the Fund’s governance and effectiveness. Ensuring that developing countries have a greater say in the IMF’s operations will help address long-standing imbalances and promote a more inclusive and equitable international financial system. This topic will be further elaborated in Section 6.

In addition, and very importantly, expanding the space for regional monetary institutions is essential. The fundamental virtues of these institutions are their members’ greater sense of belonging and, therefore, the greater proximity to their demands. An alternative to make them more attractive is to include contributions to these institutions as an additional criterion in the allocation of SDRs.

Finally, there could be greater competition among international reserve currencies. There are proposals to create new international currencies, such as the one that emerged from the BRICS meeting in August 2023, but their viability depends on whether central banks of the member countries support the use of those currencies and, even more, whether they will be accepted by market participants.

3 Sovereign Debt Restructuring

The restructuring of sovereign debt is a relatively empty package of international financial cooperation. Existing mechanisms are often criticized for their inadequacy in addressing the full spectrum of issues faced by debtor countries. The only traditional instrument, established in the mid-1950s, is the Paris Club’s restructuring, which covers bilateral official debts with OECD countries. This mechanism, while valuable, is limited in scope and does not address debts owed to non-Paris Club countries, leaving significant gaps in comprehensive debt relief efforts.

During some crises, this framework has been supplemented with ad hoc multilateral mechanisms to address developing countries’ pressing sovereign debt issues.Footnote 17 A notable example is the Brady Plan launched in 1989, in response to the Latin American crisis of the 1980s. The Brady Plan enabled developing countries, including a significant number from Latin America and from other parts of the world, to restructure their debts. However, this initiative had a major drawback: it arrived too late, almost at the end of the so-called lost decade of Latin America, a period characterized by very slow economic growth and social challenges in the region. Despite its tardiness, the Brady Plan had key virtues, particularly the reduction of debt balances, which alleviated the debt burden of affected countries, and the effective launch of a sovereign bond market. This bond market mechanism has been widely used by developing countries since the last decade of the twentieth century and has become particularly dynamic after the North Atlantic financial crisis.

For low-income countries, another significant debt relief mechanism was the Heavily Indebted Poor Countries Initiative (HIPC) launched in 1996 by the IMF and the World Bank. This initiative aimed to provide comprehensive debt relief to heavily indebted countries and ensure that they did not face unmanageable debt burdens. To take part in the HIPC initiative, countries had to fulfill specific criteria, pledge to implement policies aimed at reducing poverty, and show track record of such efforts. The HIPC was further complemented in 2005 with the Multilateral Debt Relief Initiative, which went a step further by cancelling the debt of eligible countries to the IMF, the World Bank, and the African Development Fund. Additionally, a similar relief mechanism was adopted by the Interamerican Development Bank, benefiting five low-income countries in Latin America and the Caribbean.

After the 1994 Mexican crisis, there was a discussion on this issue within the framework of OECD’s G10. The most important proposal was to introduce new clauses in the bond contracts issued in the United States – collective action clauses (CACs), although they were not called initially that way – a mechanism similar to that which already existed in the London market, where the coordination of creditors in cases of debt restructuring must be managed through a trustee with the prerogative to negotiate or initiate legal procedures.

The only attempt to create a stable institutional framework for debt restructuring took place in 2001–3 at the IMF, as an initiative of the United States. The objective was to create an institutional mechanism to promote agreements between debtors and creditors that would allow unsustainable debts to be restructured through a rapid, orderly, and predictable process while protecting the rights of creditors (Krueger, Reference Krueger2002). The terms of the proposal varied throughout the process, especially with respect to the role of the Fund, due to the opposition of many private actors and civil society to the idea of it playing too active a role in the negotiations or in the approval of the final agreements. On the other hand, it was agreed that domestic public debts should be excluded from these processes. In the final versions of the proposal, although the mechanism would be implemented through an amendment to the Articles of Agreement of the IMF, the body that would be created to guarantee the functioning of the renegotiations would be independent of the IMF Executive Board and its Board of Governors.Footnote 18

The final proposal was rejected by its initial promoter, the United States, under pressure from its financial sector and internal opposition within the Treasury Secretariat, but also from some developing countries (notably Brazil and Mexico) that feared that this mechanism could restrict and make more costly their access to international capital markets, which at that time was already quite limited. The alternative solution, led by Mexico, was the widespread use of CACs in bonds issued in the United States starting in 2003. This experience showed that the costs associated with introducing this clause were minimal. Added to this was the decision by the Eurozone in 2013 to require the inclusion of aggregation clauses in the bond contracts issued by its members, which facilitates the simultaneous renegotiating of multiple bond issues.

Furthermore, following the North Atlantic financial crisis of 2007–9, there were widespread calls for reforms aimed at addressing issues faced by Credit Rating Agencies (CRAs), including their mechanistic way they estimate ratings and their procyclical pattern, which may in fact enhance the probability of debt crises, as well as their lack of competitive dynamics, and inherent conflicts of interest. While some reforms were introduced to tackle these concerns, significant challenges persist. The market remains dominated by the three largest CRAs – Moody’s, Standard&Poors, and Fitch – collectively controlling over 90 percent of the industry, which limits the competitive pressures necessary to drive change in their practices. Unlike other financial institutions, these agencies operate without formal regulation and oversight. Moreover, their reliance on CRA ratings continues to be driven by structural conflicts of interest and conflicting regulatory and investment mandates. However, the COVID-19 pandemic, ongoing technological advancements, mounting systemic risks, and the increasing complexity of global finance underscore the critical need to fundamentally reassess the entire informational framework supporting sovereign borrowing (United Nations, 2022).

For its part, Argentina’s defeat in its 2013–14 litigation in US courts led to new solutions. The specific problem was the particular interpretation of the “pari passu clause,” which forced that country to make full payment of the debt with the creditors who had not participated in the two renegotiations that the country had carried out in previous years – the so-called dissident creditors or holdouts. The solution was to make bond issues that included both the revision of that clauseFootnote 19 and the aggregation mechanisms that Europeans had developed. Mexico led the way again in November 2014, when it inserted the new clauses in a New York bond issue – Kazakhstan had done the same in a new London issue during the previous month – without affecting the cost of the debt. It also replaced the fiscal agent with a trustee to represent the bondholders in negotiations with the debtors – a system similar to that of London.

In any case, aggregation does not exclude the possibility of blocking majorities in individual issues and does not guarantee coherence between bond contracts and other debt contracts, such as loans from banking consortia. To these considerations, we can add the caveat that, even if the revised CACs could solve future problems, they do not resolve the legacy of existing debt for some time and may even worsen it until aggregation clauses are included in all the debt contracts.

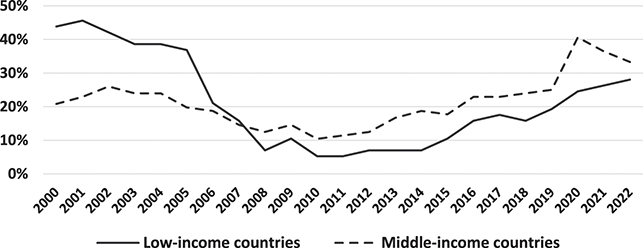

Recent problems in this field are associated with the COVID-19 pandemic and the complexities that the global economy has faced subsequently, including its slow recovery and the high interest rates generated when global inflation accelerated after the Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022. Figure 4 shows the proportion of developing countries with high levels of public debt – defined as debts that exceed 70 percent of GDP – as assessed by the IMF and the World Bank. The share of high-indebted low-income earners, which had fallen significantly with the 2005 multilateral debt relief policy, began to rise again since the mid-2010s and now reaches almost 30 percent. In turn, the proportion of middle-income countries with high debt decreased in the first decade of the twenty-first century, but began to increase in the second decade, reaching a new peak in 2020 and still remains above the levels of the previous two decades.

Figure 4 Proportion of developing countries with high debt levels (over 70 percent of GDP).

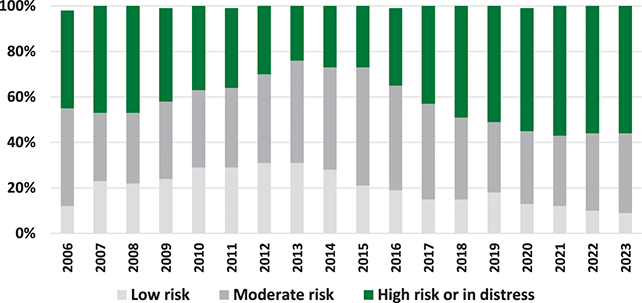

Due to the high levels of interest rates that have recently characterized the global economy and the high-risk spreads in global private financial markets, even countries that do not face high levels of debt may be characterized as facing debt distress. This is also reflected in the high level of interest payments as a proportion of public sector revenues, as well as in the fact that new issues that, in a sense, replace old debt would have higher levels of interest payments. Figure 5 indicates that, on a broader definition, more than half of low-income countries – that is, those with access to IDA – face high debt risks, and another third of them face moderate risk, again according to the analysis of the Bretton Woods institutions.Footnote 20 It should be added that, according to IMF projections, all groups of developing countries have and will continue to have in the coming years higher debt levels than those of 2019 (IMF, 2023a, Graph 3.1).

Figure 5 Risk of debt distress among IDA-eligible countries.

During the pandemic, the G20 and the Paris Club launched the Debt Service Suspension Initiative (DSSI) for low-income countries. With support from the World Bank and the IMF, the ISSD helped withhold payments for $12.9 billion from forty-eight countries, among the seventy-three eligible between May 2020 and December 2021 (World Bank, 2022a). However, it was only a temporary and partial solution, and it did not reduce debt levels and achieved minimal participation from private creditors. Since its expiration, it is estimated that almost half of the eligible countries are at risk of difficulties repaying their debts.

At the end of 2020, the G20 and the Paris Club also launched, for DSSI-eligible countries, the Common Framework for Debt Treatment. It aims to improve the coordination of debt treatments and incorporate the participation of a broad base of creditors, including new official creditors – China, India, and Saudi Arabia, among others – to guarantee comparable burden sharing. For countries where debt is unsustainable, the program can offer a reduction in its net present value to regain sustainability. When debt is sustainable, but the country faces liquidity issues or high debt costs, it can offer rescheduling or reprofiling of debt.

However, this mechanism has not been able to speed up debt restructurings. Only four countries have requested to take part in the Common Framework so far: Chad, Ethiopia, Ghana, and Zambia. The United Nations, among other organizations and analysts, has proposed using an improved version of this mechanism, as noted in this section below. Several middle-income countries need immediate debt relief but do not meet DSSI requirements. Some, such as Lebanon, Sri Lanka, and Suriname, have already defaulted on their payments and others, such as Egypt, Pakistan, and Tunisia, are facing serious debt problems. In Latin America, Argentina and Ecuador restructured their external debts through negotiations with bondholders in recent years.

The IMF has recently argued that the timelines in the restructuring processes have shortened, specifically on the steps in the restructuring that are necessary before the first review of the IMF program can be presented to the IMF Executive Board. While this process took Chad and Zambia, 12.4 and 10.4 months, respectively, it took Sri Lanka 8.8 months in December 2023 and 8 months for Ghana in January 2024 (Global Sovereign Debt Roundtable, 2024).

Outside the Common Framework, Argentina and Suriname made separate debt restructuring deals with the Paris Club and its private creditors in 2022 (World Bank, 2023a), and Sri Lanka with its official creditors in 2024. Argentina’s agreement involved restructuring $2 billion in arrears from a 2014 deal over six years at a reduced interest rate. Suriname’s deal restructured $58 million in arrears and debt service payments due in 2023–4 over an extended seventeen-to-twenty-year period, with a possible further restructuring in 2025 based on the IMF program outcome. Additionally, Suriname renegotiated $600 million of its dollar-denominated bonds in 2022 into a new ten-year amortizing bond. Sri Lanka’s economic crisis led to defaulting on debts to both official and private creditors, prompting talks with China, India, and bondholders. In July 2023, Sri Lanka approved a plan to convert Treasury bills into longer-maturity Treasury bonds as part of its domestic debt restructuring strategy. In July 2024, it reached an agreement with its bilateral creditors, including China and India.

Furthermore, challenges persist regarding debt transparency for both borrowers and creditors. Borrowers often face issues due to governance gaps, weak legal frameworks, limited institutional capacity, and inefficient reporting systems, which can lead to inaccuracies in recording and reporting debt positions, thereby reducing accountability. While creditors generally maintain sound lending practices, there is room for improvement in information sharing and transparency. Making information more accessible can promote a more responsible lending environment. These transparency issues are particularly acute in developing countries, where factors such as resource constraints, weak information systems, and inadequate coordination among government agencies hinder effective debt management, reporting, and accountability. This lack of transparency can encourage authorities to bypass fiscal rules or accept unfavorable borrowing terms, undermining sustainable development (IMF, 2023a). Addressing these challenges through enhanced governance, improved information sharing, and capacity building efforts is crucial to encourage responsible borrowing practices, support robust economic policymaking, and ultimately foster sustainable growth for borrowing nations (Ocampo and González, Reference José Antonio and Daniela González2024).

The absence of consistent, comprehensive, and promptly updated public debt information presents significant obstacles within the international debt framework. Specifically, discrepancies or inaccuracies in debt records from various sources can hinder efficient debt management, compromise the accuracy of debt sustainability assessments, and delay timely and fair debt restructuring initiatives (Rivetti, Reference Rivetti2022). The COVID-19 crisis and its aftermath have emphasized the pressing need to enhance debt transparency, underscoring the urgency for debt settlement and restructuring efforts.

Ambitious reforms are therefore needed. In September 2020, the IMF highlighted the need to improve the contractual approach to debt restructuring (IMF, 2020). At the same time, it emphasized the growing problems associated with collateralized debt that is not in the form of bonds and the lack of transparency in that area. But these contractual agreements are also insufficient, because half of the sovereign bonds of emerging and developing countries lack expanded collective action clauses that allow the simultaneous renegotiation of several debt contracts.

For all these reasons, designing a permanent institutional mechanism to restructure sovereign debts is essential (United Nations, 2023a and 2023b). This statutory approach, as it has been called in the debates, should create an institution that should preferably operate in the United Nations, but could also do so in the IMF, as was attempted at the beginning of the century, if decisions are made by a specialized agency independent of the Fund’s Executive Board and Board of Governors. The corresponding body should serve as a framework for renegotiation in three stages, each with fixed deadlines: voluntary renegotiation, mediation, and arbitration.

Even if these negotiations begin, it will be a long and complex process. For this reason, an essential complement is an ad hoc mechanism, which could be, as already noted, the expansion of the Common Framework for Debt Restructuring, as the United Nations (2023a and 2003b) and other institutions have suggested. To achieve this, it would be essential that this scheme meet the following six essential criteria:

Include a clear and shorter time frame.

Suspend debt payments during negotiations – that is, operate temporarily as a standstill mechanism.

Include the necessary mechanisms to guarantee debt sustainability, including debt reductions – “haircuts,” as they are called in the debate – and not only lower interest rates and extended maturities.

Establish clear processes and precise rules to guarantee that all debts are renegotiated, and all creditor countries and private creditors participate – a topic on which I return below in this section.

Priority rules that favor lenders who have provided financing during the crisis.

Expand eligibility to middle-income countries.