Consistent evidence has been accumulated showing that early interventions facilitate recovery and reduce long-term disability in patients with psychosis. Reference Penn, Waldheter, Perkins, Mueser and Lieberman1,Reference Marshall and Rathbone2 Literature has also shown that early interventions should be provided on an integrated basis (i.e. multi-element) and be grounded in evidence-based psychosocial treatments. Reference Nordentoft, Rasmussen, Melau, Hjorthoj and Thorup3–5 However, there is as yet no consensus on a service model for the provision of early interventions for patients with first-episode psychosis (FEP), nor do we know to what extent early intervention services are generalisable. Reference Singh and Fisher6–Reference Castle8 The GET UP (Genetics, Endophenotypes, Treatment: Understanding early Psychosis) PIANO (Psychosis: early Intervention and Assessment of Needs and Outcome) trial Reference Ruggeri, Bonetto, Lasalvia, De Girolamo, Fioritti and Rucci9 was set up to fill this gap. It was designed to assess early multi-element psychosocial interventions in epidemiologically representative samples of patients treated in routine generic mental health settings. A previous paper reported the feasibility and effectiveness of adding a multi-element psychosocial intervention to the standard treatment of patients with FEP. At 9-month follow-up it was clear, based on the retention rates of patients and families in the experimental arm, that early multi-element interventions could be delivered effectively in routine mental health services. Moreover, compared with patients receiving ‘routine care’, those treated with the early multi-element interventions displayed greater reductions in overall symptom severity, and greater improvements in global functioning, emotional well-being and the subjective burden of delusions. Reference Ruggeri, Bonetto, Lasalvia, Fioritti, de Girolamo and Santonastaso10 Overall, the study findings were consistent with those of a large trial conducted in the Recovery After an Initial Schizophrenia Episode (RAISE) initiative, which compared a comprehensive, multidisciplinary, team-based treatment approach for FEP, designed for implementation in the USA healthcare system, with routine community care (i.e. patients in the experimental arm experienced greater improvement in quality of life, psychopathology and social functioning). Reference Kane, Robinson, Schooler, Mueser, Penn and Rosenheck11

In the present study we sought to identify, among baseline demographic and clinical characteristics, predictors and moderators of treatment outcomes at 9 months. Existing literature provides some information on predictors of treatment outcome in patients with FEP. Reference Crespo-Facorro, de la Foz, Ayesa-Arriola, Pérez-Iglesias, Mata and Suarez-Pinilla12–Reference Schimmelmann, Huber, Lambert, Cotton, McGorry and Conus17 Available data, however, are rarely based on epidemiological samples compared with controls, and this increases the risk of underestimating the complexities of treating FEP in real-world services. Reference Ruggeri, Lasalvia and Bonetto18 The present study attempted to deal with this gap, and, in particular, aimed to understand: (a) which patients' characteristics are associated with a better treatment response, regardless of treatment type (non-specific predictors); and (b) which characteristics are associated with a better response to the specific FEP treatment provided in the GET UP trial (moderators). Predictors of outcome across treatment groups provide prognostic information by clarifying which patients will respond more favourably to treatment in general, whereas treatment moderators provide prescriptive information about optimal treatment selection. Reference Wolitzky-Taylor, Arch, Rosenfield and Craske19 Although there are clinical benefits in establishing baseline predictors of overall treatment success, Reference Kraemer, Wilson, Fairburn and Agras20 identifying treatment moderators (who will do better in which treatment) may have more important clinical and cost-effectiveness implications. Despite the value of identifying the subgroups of patients and the circumstances associated with the effectiveness of early multi-element psychosocial interventions for psychosis, there is as yet little information about moderators of outcome. These findings would be extremely relevant in order to clarify generalisability issues of the experimental intervention effectiveness. The present study aims to fill this knowledge gap. Based on the existing literature, we hypothesised that, regardless of treatment, symptomatic improvement at 9 months would be poorer in men, Reference Crespo-Facorro, de la Foz, Ayesa-Arriola, Pérez-Iglesias, Mata and Suarez-Pinilla12 and in people with an early age at onset, Reference Harrington, Neffgen, Sasalu, Sehgal and Woolley13 lower levels of education, Reference Allott, Alvarez-Jimenez, Killackey, Bendall, McGorry and Jackson16 a longer duration of untreated psychosis (DUP), Reference Kane, Robinson, Schooler, Mueser, Penn and Rosenheck11,Reference Jeppesen, Petersen, Thorup, Abel, Ohlenschlaeger and Christensen21,Reference Marshall, Lewis, Lockwood, Drake, Jones and Croudace22 poor premorbid functioning, Reference Crespo-Facorro, de la Foz, Ayesa-Arriola, Pérez-Iglesias, Mata and Suarez-Pinilla12,Reference Albert, Bertelsen, Thorup, Petersen, Jeppesen and Le Quack15,Reference Allott, Alvarez-Jimenez, Killackey, Bendall, McGorry and Jackson16 poor insight, Reference Bergé, Mané, Salgado, Cortizo, Garnier and Gomez14 lower adherence to medication, Reference Malla, Norman, Schmitz, Manchanda, Béchard-Evans and Takhar23 diagnosis of non-affective psychosis, Reference Ayesa-Arriola, Rodríguez-Sánchez, Pérez-Iglesias, González-Blanch, Pardo-García and Tabares-Seisdedos24 and higher baseline symptom severity. Reference Crespo-Facorro, de la Foz, Ayesa-Arriola, Pérez-Iglesias, Mata and Suarez-Pinilla12,Reference Albert, Bertelsen, Thorup, Petersen, Jeppesen and Le Quack15,Reference Allott, Alvarez-Jimenez, Killackey, Bendall, McGorry and Jackson16 Given the lack of available information (with the exception of the DUP as reported by the RAISE study Reference Kane, Robinson, Schooler, Mueser, Penn and Rosenheck11 ), no specific a priori hypotheses could be made about moderators; thus, moderator analyses will be exploratory and use the same set of variables analysed as predictors.

Method

The GET UP PIANO trial

The GET UP PIANO trial is a large multicentre randomised controlled trial comparing an add-on multi-element psychosocial early intervention with ‘routine care’ for patients with FEP and their relatives provided within Italian public general mental health services. Of the 126 community mental health centres (CMHCs) located in two northern Italian regions (Veneto and Emilia-Romagna) and the urban areas of Florence, Milan and Bolzano, 117 (92.9%) participated, covering an area of 9 304 093 inhabitants. The assignment units (clusters) were the CMHCs, and the units of observation and analysis were patients and their families. The trial received approval by the ethics committees of the coordinating centre (Azienda Ospedaliera Universitaria Integrata di Verona) and each participating unit and was registered with ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT01436331). Full details of the protocol of the GET UP study and the main findings of the GET UP PIANO trial can be found elsewhere. Reference Ruggeri, Bonetto, Lasalvia, De Girolamo, Fioritti and Rucci9,Reference Ruggeri, Bonetto, Lasalvia, Fioritti, de Girolamo and Santonastaso10

Participants

During the index period, all CMHCs participating in the GET UP PIANO trial were asked to refer individuals with potential cases of psychosis at first contact to the study team. The inclusion criteria were: (a) age 18–54 years; (b) residence within the catchment areas of the CMHCs; (c) presence of at least one of the following symptoms: hallucinations, delusions, qualitative speech disorder, qualitative psychomotor disorder, bizarre, or grossly inappropriate behaviour; or two of the following symptoms: loss of interest, initiative and drive; social withdrawal; episodic severe excitement; purposeless destructiveness; overwhelming fear; or marked self-neglect; (d) first lifetime contact with CMHCs, prompted by these symptoms. Exclusion criteria were: (a) prescribed antipsychotic medication in the past 3 months, for an identical or similar mental disorder; (b) mental disorders because of a general medical condition; (c) moderate-severe intellectual disability diagnosis assessed by a clinical functional assessment; and (d) diagnosis other than ICD-10 for psychosis 25 (with the exception of non-psychotic disorders comorbid with a primary diagnosis of psychosis). All eligible patients who achieved clinical stabilisation were invited to provide written informed consent for assessment. They were told of the nature, scope and possible consequences of the trial and that they could withdraw consent at any time. They were also asked to give consent for family member assessments; family members who agreed to participate provided written informed consent.

The specific ICD-10 codes for psychosis (F1x.4; F1x.5; F1x.7; F20–29; F30.2, F31.2, F31.5, F31.6, F32.3, F33.3) were assigned at 9 months; the best-estimate ICD-10 diagnosis was made by consensus of a panel of clinicians taking into account all available information on the time interval from patient's intake by completing the Item Group Checklist (IGC) of the Schedule for Clinical Assessment in Neuropsychiatry (SCAN). 26

Treatments

The experimental treatment consisted of a multi-element psychosocial intervention, adjunctive to routine care. It included the delivery of cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT) for psychosis to patients, Reference Kuipers, Fowler, Garety, Chisholm, Freeman and Dunn27,Reference Garety, Fowler, Freeman, Bebbington, Dunn and Kuipers28 and of psychosis-focused family intervention Reference Kuipers, Leff and Lam29 to families, together with case management Reference Burns and Firn30 involving both patients and their families. It was provided by CMHC staff, trained in the previous 6 months and supervised by experts. The intervention began as soon as patients achieved clinical stabilisation (i.e. a condition in which they could collaborate in a brief clinical examination). Core baseline measures were taken. Control arm CMHCs provided only treatment as usual (TAU), which, in Italy, comprises personalised out-patient psychopharmacological treatment and non-specific supportive clinical management by the CMHC. Reference Ferrannini, Ghio, Gibertoni, Lora, Tibaldi and Neri31 Family interventions in TAU consisted of non-specific informal support sessions.

Measures

A set of core outcome instruments (Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS), Reference Kay, Fiszbein and Opler32 Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF), 33 Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HRSD) Reference Hamilton34 ) was administered by a panel of 17 independent evaluators at baseline (after clinical stabilisation and before treatment was initiated) and at 9-month follow-up. For the PANSS the three traditional subscales were considered – positive symptoms, negative symptoms and general psychopathology.

An extensive set of standardised instruments was also administered at baseline, including the Premorbid Social Adjustment scale (PSA) Reference Foerster, Lewis, Owen and Murray35 for premorbid functioning, the Schedule for Assessment of Insight (SAI-E) Reference David, Buchanan, Reed and Almeida36 for insight into illness and a modified version of the Nottingham Onset Schedule (NOS) Reference Singh, Cooper, Fisher, Tarrant, Lloyd and Banjo37 for the DUP. These clinical measures, together with baseline sociodemographics (gender, age at first contact, citizenship, education) were analysed as putative predictors/moderators.

All the 17 independent evaluators were trained in the administration and rating of the instruments. For the interrater reliability, each evaluator independently rated three videos on the PANSS, which were recorded and rated by an independent clinician. High levels of agreement (mean percentage agreement on the items of each scale) were reached between each evaluator and the clinician. Specifically, 85% for the positive scale, 70% for the negative scale and 82% for the general scale. The intraclass correlation coefficient was 0.81. Patients, clinicians and evaluators could not be masked to the trial arm. Every effort was made to preserve the evaluators' independence; conflicts of interest were monitored.

Statistical analyses

Analyses were conducted using an intention-to-treat (ITT) approach. PANSS, GAF and HRSD scores were analysed separately in mixed-effects random regression models. In order to take into account the trial design in which patients (level 1) were nested within CMHCs (level 2) (CONSORT guidelines for cluster randomised trials 38 ), the individual CMHCs were included in the models as a random effect. In order to identify predictors and moderators of treatment outcome according to MacArthur's approach, Reference Kraemer, Wilson, Fairburn and Agras20 we selected a priori, on clinical or empirical grounds and derived from the literature, a subset of demographic and baseline clinical variables. Specifically, we investigated gender, age at first contact, citizenship (Italian/non-Italian), educational level (high/low), DUP, type of psychosis (affective/non-affective), premorbid functioning (four components: school and social functioning, in both childhood and adolescence) and insight into illness (three components: attribution of symptoms, illness awareness and treatment adherence). Each model included treatment allocation (T coded as +½ for patients in the experimental treatment group and −½ for those in the TAU group), one predictor/moderator (M standardised), their interaction (T×M) and the baseline score of the outcome investigated (B standardised). When the main effect of a variable was significant but the interaction was not, the variable was considered a non-specific predictor of outcome. When the interaction was significant (regardless of the significance of main effects), the variable was considered as a moderator. For each variable, the predictor and moderator effect size was calculated using the formulae provided by Kraemer. Reference Kraemer39

In a secondary analysis, missing data on outcomes were estimated using a multiple imputation approach by chained equations (MICE), which generates several different plausible imputed data-sets and combines results from each of them. MICE was applied because it allows one to handle different variable types; specifically, we used predictive mean matching to deal with possible non-normality when imputing continuous variables and logistic regression to impute binary variables. The alpha level was set to 0.05 for all main effects and interactions. All statistical analyses were carried out using the Stata software package, version 13.

Results

Demographic and clinical variables of the 444 study participants examined as potential predictors or moderators of treatment outcome are presented in online Table DS1.

Predictors

Some attributes of patients predicted outcomes regardless of treatment assignment. Among sociodemographic characteristics (Table 1), higher education predicted lower overall symptoms (b = −0.06, P= 0.034), negative symptoms (b = −0.11, P= 0.009) and general psychopathology (b = −0.06, P= 0.046) at 9 months. Several clinical characteristics predicted outcomes at 9 months (Table 2 and Table 3): specifically, a longer DUP predicted higher depressive symptoms (b = 1.42, P = 0.002); poorer premorbid social functioning in adolescence predicted higher levels of overall psychotic symptoms (b = 0.07, P = 0.043) and depressive symptoms (b = 0.90, P = 0.039); and poorer premorbid scholastic functioning in adolescence predicted higher negative symptoms (b = 0.11, P = 0.035). Moreover, poorer attribution of symptoms predicted higher severity of overall psychotic symptoms (b = −0.07, P = 0.036), higher levels of positive symptoms (b = −0.12, P = 0.003) and worse global functioning (b = 2.75, P = 0.008); and poorer treatment adherence predicted higher level of overall psychotic symptoms (b = −0.08, P= 0.015), positive symptoms (b = −0.08, P= 0.017), negative symptoms (b = −0.11, P = 0.031) and general psychopathology (b = 70.06, P= 0.045).

Table 1 Sociodemographic characteristics as potential predictors/moderators of treatment outcome a

| b (95% CI), P | r(ΔO, DM) b | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome at follow-up (adjusted for baseline) |

Main effect, prediction | Interaction with treatment, moderation |

Predictor effect size |

Moderator effect size |

| Age at first contact | ||||

| PANSS total | 0.04 (−0.02 to 0.09), 0.157 | −0.12 (−0.23 to −0.01), 0.032* | 0.04 | −0.06 |

| PANSS positive | −0.00 (−0.06 to 0.05), 0.889 | −0.07 (−0.8 to 0.05), 0.238 | 0.00 | −0.03 |

| PANSS negative | 0.06 (−0.02 to 0.14), 0.155 | −0.17 (−0.34 to −0.01), 0.042* | 0.04 | −0.06 |

| PANSS general | 0.06 (0.00 to 0.11), 0.039 | −0.14 (−0.25 to −0.03), 0.014* | 0.06 | −0.07 |

| GAF score | −0.44 (−1.95 to 1.07), 0.570 | −0.13 (−3.19 to 2.93), 0.934 | −0.02 | 0.00 |

| HRSD score | 0.34 (−0.51 to 1.18), 0.432 | −0.13 (−1.83 to 1.56), 0.878 | 0.02 | 0.00 |

| Gender (reference men) | ||||

| PANSS total | 0.00 (−0.05 to 0.06), 0.944 | 0.04 (−0.07 to 0.14), 0.511 | 0.00 | 0.02 |

| PANSS positive | 0.04 (−0.02 to 0.10), 0.179 | 0.04 (−0.07 to 0.16), 0.438 | 0.03 | 0.02 |

| PANSS negative | −0.02 (−0.10 to 0.07), 0.711 | −0.04 (−0.21 to 0.12), 0.595 | −0.01 | −0.01 |

| PANSS general | −0.01 (−0.06 to 0.05), 0.725 | 0.07 (−0.04 to 0.18), 0.227 | −0.01 | 0.03 |

| GAF score | −0.94 (−2.42 to 0.54), 0.213 | 0.30 (−2.67 to 3.26), 0.845 | −0.03 | 0.01 |

| HRSD score | 0.50 (−0.32 to 1.33), 0.229 | 0.46 (−1.19 to 2.10), 0.588 | 0.03 | 0.01 |

| Citizenship (reference Italian) | ||||

| PANSS total | 0.01 (−0.04 to 0.06), 0.646 | −0.02 (−0.13 to 0.08), 0.647 | 0.01 | −0.01 |

| PANSS positive | 0.02 (−0.03 to 0.08), 0.460 | −0.04 (−0.16 to 0.07), 0.429 | 0.02 | −0.02 |

| PANSS negative | 0.01 (−0.07 to 0.09), 0.860 | −0.01 (−0.17 to 0.15), 0.899 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| PANSS general | 0.01 (−0.04 to 0.06), 0.691 | −0.05 (−0.15 to 0.06), 0.381 | 0.01 | −0.02 |

| GAF score | 0.19 (−1.23 to 1.62), 0.791 | 0.79 (−2.07 to 3.64), 0.589 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| HRSD score | 0.26 (−0.56 to 1.09), 0.529 | 0.10 (−1.55 to 1.75), 0.906 | 0.02 | 0.00 |

| Education (reference high level) | ||||

| PANSS total | −0.06 (−0.12 to −0.00), 0.034* | −0.00 (−0.11 to 0.11), 0.996 | −0.06 | 0.00 |

| PANSS positive | −0.03 (−0.09 to 0.02), 0.253 | −0.02 (−0.13 to 0.10), 0.751 | −0.03 | −0.01 |

| PANSS negative | −0.11 (−0.20 to −0.03), 0.009* | 0.02 (−0.15 to 0.19), 0.832 | −0.07 | 0.01 |

| PANSS general | −0.06 (−0.11 to −0.00), 0.046 | 0.00 (−0.11 to 0.11), 0.980 | −0.06 | 0.00 |

| GAF score | 1.47 (−0.04 to 2.99), 0.057 | 0.48 (−2.55 to 3.50), 0.758 | 0.05 | 0.01 |

| HRSD score | −0.65 (−1.52 to 0.21), 0.136 | 0.65 (−1.07 to 2.36), 0.461 | −0.04 | 0.02 |

PANSS, Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale; GAF, Global Assessment of Functioning; HRSD, Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression.

a. Mixed-effects random regression models estimated for patients who were assessed at both baseline and follow-up (experimental treatment group, n = 239; treatment-as-usual group, n = 153).

b. See Kraemer for the calculation of predictor and moderator effect size. Reference Kraemer39

* Predictors/moderators that remained significant (P<0.05) after applying multiple imputation procedure by chained equations (MICE).

Table 2 Duration of untreated psychosis (DUP), insight (Schedule for Assessment of Insight (SAI)) and diagnosis as potential predictors/moderators of treatment outcome a

| b (95% CI), P | r(ΔO, DM) b | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome at follow-up (adjusted for baseline) |

Main effect, prediction | Interaction with treatment, moderation |

Predictor effect size |

Moderator effect size |

| DUP (months) | ||||

| PANSS total | 0.04 (−0.02 to 0.09), 0.171 | 0.00 (−0.11 to 0.11), 0.967 | 0.04 | 0.00 |

| PANSS positive | 0.03 (−0.03 to 0.09), 0.266 | 0.01 (−0.11 to 0.13), 0.855 | 0.03 | 0.00 |

| PANSS negative | 0.08 (−0.00 to 0.17), 0.055 | 0.01 (−0.16 to 0.18), 0.927 | 0.05 | 0.00 |

| PANSS general | 0.03 (−0.02 to 0.09), 0.267 | 0.00 (−0.11 to 0.12), 0.978 | 0.03 | 0.00 |

| GAF score | −0.84 (−2.46 to 0.77), 0.308 | 0.15 (−3.04 to 3.34), 0.927 | −0.03 | 0.00 |

| HRSD score | 1.42 (0.53 to 2.31), 0.002* | −0.83 (−2.62 to 0.95), 0.361 | 0.08 | −0.03 |

| SAI attribution of symptoms | ||||

| PANSS total | −0.07 (−0.14 to −0.00), 0.036 | −0.04 (−0.18 to 0.09), 0.538 | −0.08 | −0.02 |

| PANSS positive | −0.12 (−0.20 to −0.04), 0.003* | −0.06 (−0.21 to 0.09), 0.447 | −0.11 | −0.03 |

| PANSS negative | −0.09 (−0.19 to 0.01), 0.084 | −0.16 (−0.36 to 0.04), 0.120 | −0.06 | −0.06 |

| PANSS general | −0.06 (−0.13 to 0.01), 0.108 | −0.01 (−0.14 to 0.13), 0.919 | −0.06 | 0.00 |

| GAF score | 2.75 (0.71 to 4.80), 0.008* | −2.08 (−5.98 to 1.82), 0.297 | 0.10 | −0.04 |

| HRSD score | −0.87 (−1.75 to 0.00), 0.051 | 0.10 (−1.64 to 1.84), 0.910 | −0.07 | 0.00 |

| SAI illness awareness | ||||

| PANSS total | 0.02 (−0.07 to 0.10), 0.711 | 0.10 (−0.06 to 0.26), 0.231 | 0.02 | 0.06 |

| PANSS positive | −0.02 (−0.10 to 0.07), 0.668 | 0.02 (−0.16 to 0.19), 0.852 | −0.02 | 0.01 |

| PANSS negative | 0.04 (−0.08 to 0.17), 0.471 | 0.08 (−0.17 to 0.32), 0.534 | 0.04 | 0.03 |

| PANSS general | 0.01 (−0.07 to 0.09), 0.865 | 0.13 (−0.04 to 0.29), 0.125 | 0.01 | 0.07 |

| GAF score | −0.29 (−2.72 to 2.14), 0.815 | −2.17 (−7.17 to 2.83), 0.394 | −0.01 | −0.04 |

| HRSD score | −0.11 (−1.27 to 1.05), 0.858 | 2.32 (0.02 to 4.62), 0.048 | −0.01 | 0.09 |

| SAI treatment adherence | ||||

| PANSS total | −0.08 (−0.14 to −0.02), 0.015 | −0.07 (−0.20 to 0.05), 0.268 | −0.08 | −0.04 |

| PANSS positive | −0.08 (−0.15 to −0.01), 0.017 | −0.07 (−0.20 to 0.06), 0.312 | −0.08 | −0.03 |

| PANSS negative | −0.11 (−0.21 to −0.01), 0.031* | −0.11 (−0.31 to 0.08), 0.265 | −0.07 | −0.04 |

| PANSS general | −0.06 (−0.13 to −0.00), 0.045 | −0.07 (−0.19 to 0.06), 0.285 | −0.07 | −0.04 |

| GAF score | 1.30 (−0.56 to 3.16), 0.170 | 1.75 (−1.88 to 5.38), 0.344 | 0.05 | 0.03 |

| HRSD score | −0.51 (−1.32 to 0.29), 0.212 | −0.72 (−2.34 to 0.89), 0.381 | −0.04 | −0.03 |

| Type of psychosis (reference affective) | ||||

| PANSS total | 0.02 (−0.04 to 0.07), 0.558 | −0.02 (−0.14 to 0.09), 0.659 | 0.02 | −0.01 |

| PANSS positive | 0.03 (−0.03 to 0.08), 0.310 | −0.02 (−0.13 to 0.10), 0.763 | 0.03 | −0.01 |

| PANSS negative | 0.02 (−0.06 to 0.10), 0.645 | −0.06 (−0.23 to 0.11), 0.471 | 0.01 | −0.02 |

| PANSS general | 0.01 (−0.04 to 0.07), 0.631 | −0.02 (−0.13 to 0.10), 0.779 | 0.01 | −0.01 |

| GAF score | −1.38 (−2.92 to 0.15), 0.077 | −0.15 (−3.18 to 2.88), 0.922 | −0.05 | 0.00 |

| HRSD score | 0.47 (−0.35 to 1.30), 0.261 | −0.88 (−2.54 to 0.77), 0.296 | 0.03 | −0.03 |

PANSS, Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale; GAF, Global Assessment of Functioning; HRSD, Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression.

a. Mixed-effects random regression models estimated for patients who were assessed at both baseline and follow-up (experimental treatment group, n = 239; treatment-as-usual group, n = 153).

b. See Kraemer for the calculation of predictor and moderator effect size. Reference Kraemer39

* Predictors/moderators that remained significant (P<0.05) after applying multiple imputation procedure by chained equations (MICE).

Table 3 Premorbid social adjustment (PSA) scale as potential predictor/moderator of treatment outcome a

| b (95% CI), P | r(ΔO, DM) b | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome at follow-up (adjusted for baseline) |

Main effect, prediction | Interaction with treatment, moderation |

Predictor effect size |

Moderator effect size |

| PSA social childhood | ||||

| PANSS total | −0.01 (−0.08 to 0.06), 0.790 | 0.07 (−0.06 to 0.21), 0.279 | −0.01 | 0.04 |

| PANSS positive | −0.01 (−0.08 to 0.05), 0.694 | 0.07 (−0.06 to 0.20), 0.300 | −0.01 | 0.04 |

| PANSS negative | −0.02 (−0.13 to 0.08), 0.656 | 0.18 (−0.02 to 0.39), 0.083 | −0.02 | 0.06 |

| PANSS general | 0.00 (−0.06 to 0.07), 0.892 | 0.04 (−0.10 to 0.17), 0.599 | 0.00 | 0.02 |

| GAF score | −0.01 (−1.96 to 1.93), 0.990 | −1.75 (−5.63 to 2.13), 0.376 | 0.00 | −0.03 |

| HRSD score | 0.27 (−0.59 to 1.13), 0.534 | 0.68 (−1.03 to 2.39), 0.436 | 0.02 | 0.03 |

| PSA school childhood | ||||

| PANSS total | 0.05 (−0.02 to 0.12), 0.132 | −0.02 (−0.16 to 0.12), 0.759 | 0.06 | −0.01 |

| PANSS positive | 0.05 (−0.02 to 0.11), 0.154 | 0.01 (−0.12 to 0.14), 0.881 | 0.05 | 0.01 |

| PANSS negative | 0.07 (−0.04 to 0.18), 0.196 | −0.09 (−0.30 to 0.12), 0.396 | 0.05 | −0.03 |

| PANSS general | 0.05 (−0.02 to 0.12), 0.149 | −0.01 (−0.15 to 0.13), 0.888 | 0.05 | −0.01 |

| GAF score | −1.85 (−3.83 to 0.14), 0.069 | 1.35 (−2.59 to 5.28), 0.503 | −0.06 | 0.02 |

| HRSD score | 0.79 (−0.08 to 1.66), 0.076 | −0.12 (−1.87 to 1.62), 0.890 | 0.06 | −0.01 |

| PSA social adolescence | ||||

| PANSS total | 0.07 (0.00 to 0.14), 0.043 | 0.01 (−0.12 to 0.15), 0.851 | 0.07 | 0.01 |

| PANSS positive | 0.04 (−0.03 to 0.11), 0.246 | −0.05 (−0.18 to 0.08), 0.463 | 0.04 | −0.03 |

| PANSS negative | 0.10 (−0.00 to 0.21), 0.063 | 0.08 (−0.13 to 0.28), 0.473 | 0.07 | 0.03 |

| PANSS general | 0.06 (−0.00 to 0.13), 0.063 | 0.01 (−0.13 to 0.14), 0.915 | 0.07 | 0.00 |

| GAF score | −1.24 (−3.18 to 0.71), 0.212 | −2.27 (−6.09 to 1.56), 0.246 | −0.04 | −0.04 |

| HRSD score | 0.90 (0.05 to 1.76), 0.039 | −0.74 (−2.44 to 0.96), 0.395 | 0.07 | −0.03 |

| PSA school adolescence | ||||

| PANSS total | 0.05 (−0.02 to 0.12), 0.169 | 0.02 (−0.11 to 0.16), 0.729 | 0.05 | 0.01 |

| PANSS positive | 0.04 (−0.03 to 0.10), 0.276 | 0.06 (−0.07 to 0.19), 0.349 | 0.04 | 0.03 |

| PANSS negative | 0.11 (0.01 to 0.22), 0.035* | −0.10 (−0.31 to 0.11), 0.366 | 0.07 | −0.03 |

| PANSS general | 0.03 (−0.04 to 0.10), 0.407 | 0.06 (−0.07 to 0.20), 0.359 | 0.03 | 0.03 |

| GAF score | −1.67 (−3.63 to 0.29), 0.094 | 1.49 (−2.41 to 5.40), 0.453 | −0.06 | 0.03 |

| HRSD score | 0.77 (−0.08 to 1.63), 0.077 | 0.74 (−0.97 to 2.45), 0.397 | 0.06 | 0.03 |

APNSS, Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale; GAF, Global Assessment of Functioning; HRSD, Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression.

a. Mixed-effects random regression models estimated for patients who were assessed at both baseline and follow-up (experimental treatment group, n = 239; treatment-as-usual group, n = 153).

b. See Kraemer for the calculation of predictor and moderator effect size. Reference Kraemer39

* Predictors/moderators that remained significant (P<0.05) after applying multiple imputation procedure by chained equations (MICE).

Multiple imputation analysis confirmed that lower education predicted a higher severity of symptoms at follow-up (PANSS total score, b = −0.10, P = 0.016) and that a poorer attribution of symptoms predicted a higher severity of positive symptoms (PANSS positive score). Notably, lower educational level (b = −0.10, p = 0.016), poorer school performance in adolescence (b = 0.11, P = 0.022) and poorer treatment adherence (b = −0.10, P = 0.042) predicted a higher severity of negative symptoms (PANSS negative score). A longer DUP predicted a greater severity of depression (b = 1.11, P = 0.005), and a poorer attribution of symptoms predicted worse global functioning at follow-up (b = 2.14, P = 0.020).

Moderators

We found a differential effect of age at first contact on PANSS total score (b = −0.12, P = 0.032), negative symptoms (b = −0.17, P = 0.042) and general psychopathology (b = −0.14, P = 0.014) (Table 2). Specifically, the experimental treatment became more beneficial than TAU as age increased. When analyses were rerun using multiple imputation of missing data, the finding that age at first contact was a moderator of PANSS total score (b = −0.11, P = 0.052), negative symptoms (b = −0.18, P = 0.032) and general psychopathology (b = −0.12, P= 0.030) was confirmed.

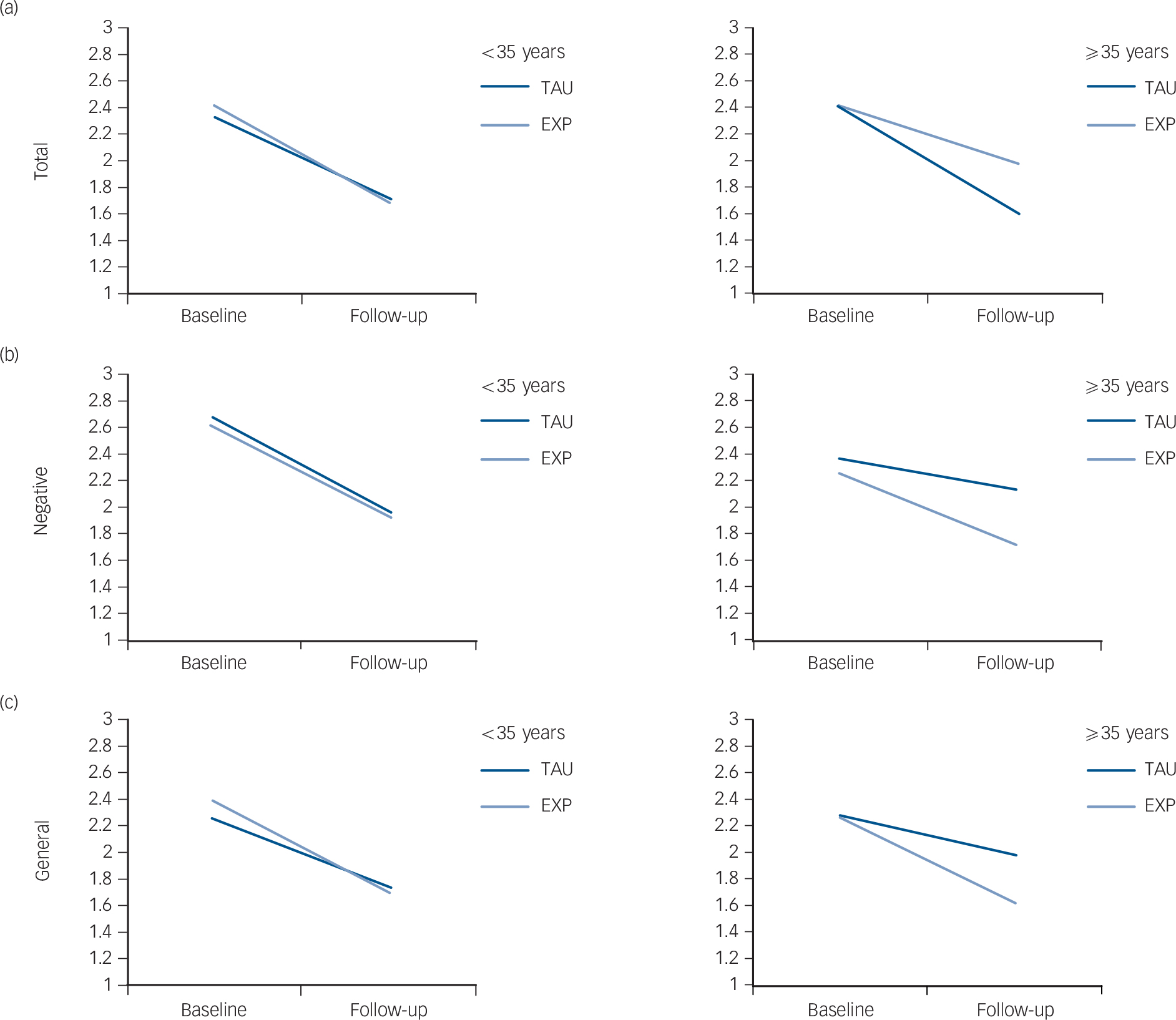

In order to determine the age cut-off at which the experimental treatment started to be significantly superior to TAU, age was categorised using different cut-offs (20, 25, 30, 35 years) in a sensitivity analysis. This analysis showed that starting from 35 years of age there was a significant treatment effect on PANSS (PANSS total: b = −0.12, P = 0.023, moderator effect size = −0.06; PANSS negative: b = −0.18, P = 0.032, moderator effect size = −0.06; PANSS general: b = −0.13, P = 0.015, moderator effect size = −0.07) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1 Strength of moderation by patient's age at first contact on the effect of the intervention (experimental EXP) v. treatment-as-usual (TAU) group) on the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS).

Left-hand graphs <35 years at first contact, right-hand graphs: ⩾35 years at first contact. (a) Total score; (b) negative symptoms; (c) general psychopathology. Mean scores are reported on the y-axis; 1, absent; 2, minimal; 3, mild; 4, moderate; 5, moderate-severe; 6, severe; 7, extremely severe).

Table 4 (lower part) shows that in the TAU arm patients with an age of onset ⩾35 years experienced no reduction of overall psychotic symptoms, negative symptoms and general psychopathology at 9 months (see delta scores), whereas patients with an age of onset less than 35 years (Table 4, upper part) experienced some benefit from both treatments, with a higher beneficial effect of experimental treatment in terms of reduction in PANSS total, negative and general scores.

Table 4 Strength of moderation by patient's age at first contact (<35 years, ⩾35 years) on the effect of intervention (experimental v. treatment as usual) on the various outcome domains

| Delta, mean | ||

|---|---|---|

| Outcome | Treatment-as-usual group | Experimental group |

| <35 years | ||

| GAF | 15.2 (14.9) | 19.4 (16.6) |

| PANSS positive | −0.68 (0.81) | −0.77 (0.81) |

| PANSS negative | −0.68 (1.02) | −0.67 (1.00) |

| PANSS general | −0.56 (0.70) | −0.66 (0.73) |

| PANSS total score | −0.63 (0.68) | −0.69 (0.70) |

| HRSD | −5.8 (13.3) | −8.8 (1.0) |

| ⩾35 years | ||

| GAF | 13.0 (12.8) | 18.3 (16.6) |

| PANSS positive | −0.71 (0.78) | −0.95 (0.72) |

| PANSS negative | −0.21 (0.69) | −0.58 (0.93) |

| PANSS general | −0.33 (0.51) | −0.65 (0.60) |

| PANSS total score | −0.41 (0.48) | −0.70 (0.56) |

| HRSD | −6.7 (13.0) | −7.0 (10.2) |

GAF, Global Assessment of Functioning; PANSS, Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale; HRSD, Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression.

These findings were confirmed after multiple imputation of missing data (results not shown). In order to identify possible reasons for this finding, we carried out secondary analyses comparing patients with an age of onset ⩾35 years with the rest of the sample. Results indicate that patients with age at onset ⩾35 years were more often females (41.0% v. 67.0%, χ2 test, P<0.001), less frequently diagnosed with schizophrenia (19.4% v. 30.7%, χ2 test, P= 0.033), less frequently unmarried (37.9% v. 91.3%, χ2 test, P<0.001) and unemployed or students (46.6% v. 70.4%, χ2 test, P<0.001).

Finally, we found that a greater awareness of illness was associated with a higher severity of depression at follow-up in the experimental group but not in the control group (b = 2.32, P = 0.048) (Table 2); this finding, however, was not confirmed in multiple imputation analysis (b = 0.38, P = 0.736). No moderation was found for GAF and HRSD.

Discussion

This is the first study to investigate in a ‘real-world’ setting which patient characteristics: (a) predict outcome regardless of treatment assignment (non-specific predictors), and (b) moderate differential response (moderators) to an adjunctive multi-element psychosocial intervention supplementing ‘routine care’ for FEP. It used a large sample and a robust methodological approach.

As expected, we found several non-specific predictors of outcome. Patients with lower education, longer DUP, poorer premorbid functioning in adolescence and poorer insight into illness showed poorer clinical outcomes at 9 months irrespective of the type of treatment. These findings are consistent with the literature Reference Kane, Robinson, Schooler, Mueser, Penn and Rosenheck11–Reference Schimmelmann, Huber, Lambert, Cotton, McGorry and Conus17,Reference Kraemer, Wilson, Fairburn and Agras20–Reference Malla, Norman, Schmitz, Manchanda, Béchard-Evans and Takhar23 and suggest that patients with FEP with these characteristics warrant specific attention and may require more intensive and/or longer treatment.

We found only one significant moderator that acted only on one outcome: patients' age at first service contact, which operated on negative symptoms and general psychopathology. Specifically, in the control group, where the effect of the intervention was overall lower than in the experimental group, the moderation effect by age at first service contact resulted in lower benefit in older compared with younger patients. Thus, the experimental intervention was not only overall significantly more effective than TAU, but was also similar in both age groups, showing greater generalisability.

The multi-element psychosocial intervention administered at the first psychotic episode seems to exert a specific additional beneficial effect on patients who develop onset of psychosis at a later stage (⩾35 years); these patients, if treated with usual care alone, would display no or low symptomatic improvement. Moreover, it is important to note that the multi-component intervention showed a specific beneficial effect on negative symptoms, which in general show relatively poorer response to psychopharmacological treatment in patients with FEP. Reference Salimi, Jarskog and Lieberman40,Reference Schennach, Riedel, Musil and Möller41

It is not completely clear what drives the relationship between age at first contact and experimental treatment outcome in our sample. However, data showing that patients with age at onset ⩾35 years were more often women, less frequently diagnosed with schizophrenia, less frequently unmarried and unemployed or a student may in part explain the moderating effect of age at first contact on treatment outcome in our sample. We may also speculate that patients developing psychosis at a later stage may be more receptive to structured cognitive coping strategies provided with both individual CBT and family therapy, since these patients have been found to be less impaired than younger patients on a broad array of cognitive tasks, Reference Howard, Rabins, Seeman and Jeste42–Reference Hanssen, van der Werf, Verkaaik, Arts, Myin-Germeys and van Os45 which are most relevant to adaptive functioning and treatment response. This issue has some interesting implications, since the idea of intervening early should not be conflated with intervening in the young, as psychosis has an impact at all stages of life. A new line of research is specifically focusing on people over 35 years presenting to mental health services with a first psychotic episode. This research found that a large proportion (55%) of patients with FEP present after the age of 25 years Reference Selvendra, Baetens, Trauer, Petrakis and Castle46 and suggested extending early intervention provision to all ages, with treatment tailored to the specific needs of different age groups. Reference Greenfield, Joshi, Christian, Lekkos, Gregorowicz and Fisher47,Reference Lappin, Heslin, Jones, Doody, Reininghaus and Demjaha48 However, future research should further investigate the relationship between age and outcome in FEP samples.

Overall, the lack of significant moderators of treatment outcomes suggests that the effects of the experimental intervention do not vary according to patient baseline characteristics and that its beneficial effect is generalisable to the overall study population. The fact that (apart from patients ⩾35 years) no specific subgroups benefit more from the experimental intervention indicates that early multi-element psychosocial intervention should be recommended to all patients with FEP treated in routine mental health services.

Study limitations

Our moderator analyses should be considered as exploratory, being aimed at providing useful information for designing future clinical studies. The effect size of the moderators identified in the present paper may serve as guidance to researchers for estimating the sample size needed in confirmation studies. In order to test hypotheses on moderating effects, confirmatory studies would be needed, including an adequately sized group of patients with the characteristics of interest (for example, age ⩾35 years), in which the outcomes of patients receiving different treatments (i.e. TAU v. GET UP intervention) are compared.

Another potential limitation is the lack of masking in the trial (patients, clinicians, other care providers and outcome evaluators were aware of treatment allocation). The study design (cluster) and the nature of the treatments under investigation did not permit masking. This limitation is inevitable and common to many cluster randomised trials investigating the effects of psychosocial interventions provided in routine care. Reference Boutron, Tubach, Giraudeau and Ravaud49 However, we tried to reduce the possible bias of unmasked outcome assessment by employing evaluators who were independent from the research team and who were not involved in treatment provision; every effort was also made throughout the trial to preserve the outcome evaluators' independence; conflicts of interest were also monitored.

Further research

Our findings provide evidence that the GET UP multi-element psychosocial intervention is beneficial to a broad array of patients with FEP treated within routine community mental health services, and especially among those over 35 years of age. Further studies in other geographical contexts and with longer-term outcomes are needed to replicate and extend our findings.

Funding

Ministry of Health, Italy – Ricerca Sanitaria Finalizzata, Code .

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the patients and their family members who participated in this study.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.