4.1 Setting the Stage

Trade facilitation (TF) – the simplification, modernisation, and harmonisation of cross-border trade processes – is once again moving up the trade policy agenda. When exploratory discussions were first launched in the 1990s, TF was considered little more than the plumbing of the trading system. Its importance has grown steadily as the world economy has become more integrated, supply chains expanded, and technological change reshaped the way goods and services are traded around the planet. Paradoxically, even the major disruptions to the world trading system in the last several years have tended to amplify, not diminish, the need to facilitate trade.

The COVID-19 pandemic served as a massive wake-up call about the importance of TF, underscoring the critical need to deliver essential products, especially medical supplies, to consumers as quickly as possible, highlighting countries’ dependency on complex and far-flung supply networks. It increased pressure on governments to find secure sources of supply and to diversify their trade relations, sometimes involving new trade partners and routes that lay beyond the well-beaten paths of traditional United States (US)–European Union (EU)–China trade corridors. Suddenly, pragmatic measures to speed up cross-border transactions, cut unnecessary red tape, harmonise trade processes, and digitalise them wherever possible became critically important. Supply chain disruptions have only increased since the outbreak of war in Ukraine, cutting off traditional sources for key commodities such as energy and grains and accelerating the push to diversify sources of supply. A subsequent series of sanctions added a whole new layer of complexity to already overstretched and overburdened customs procedures.

Those events have delivered unprecedented shocks to world trade. They also laid bare deeply rooted structural weaknesses in the system that have been hampering the smooth flow of goods long before the pandemic, straining supply chains and causing trade bottlenecks.

The conclusion of the Trade Facilitation Agreement (TFA) in 2013 was a major breakthrough, not just because it marked the first multilateral agreement since the World Trade Organization (WTO) was founded nearly two decades earlier, but because it established baseline global rules for accelerating the movement, release, and clearance of goods across borders, promising to reduce trade transaction costs by an average of over 14 per cent (WTO, 2015).Footnote 1

Even before its conclusion, the TFA was already encouraging regional TF efforts, accumulating policy innovations, widening country engagement, and building momentum in the multilateral arena. The TFA negotiation process helped energise and cross-fertilise parallel regional efforts and spurred a noticeable increase in TF outcomes elsewhere (Neufeld, Reference Neufeld2014). After the successful adoption of the TFA, TF rulemaking in preferential trade agreements (PTAs)Footnote 2 surged even more, with the aim of building on – and going further than – the multilateral foundation provided by the TFA. Slow progress in other aspects of the WTO’s work and growing pessimism about the possibilities of securing consensus for additional reforms among 164 Members reinforced perceptions that TF advances might more likely occur at the regional level in the near future. Over the last few years, most bilateral and regional trade agreements (RTAs) have incorporated TF provisions with varying degrees of ambition, including vast mega-regional agreements such as the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for a Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), the African Continental Free Trade Agreement (AfCFTA), or the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP). Complementing the TFA, these agreements were widely expected to be delivering new TFA-plus rules for facilitating trade and offering signposts for how the global TF regime might advance.

Yet, an examination of the TF provisions in this newest wave of PTAs suggests that there is often less to these agreements than meets the eye. Few of the PTAs were concluded before the TFA went beyond that multilateral benchmark – and many fell well short. Even regional agreements negotiated in the wake of the TFA are often somewhat uneven and underwhelming when it comes to their TF content, especially when viewed against the backdrop of the massive advances in digitalisation and automation that are dramatically changing the way goods and services move across borders and calling into question old approaches that require pen, paper, and, indeed, even people.

This chapter argues that rapid technological change risks rendering many old TF approaches outdated – or even obsolete – and that a renewed effort to advance and modernise the TF rulebook makes sense. It explores the changes in the world economy since the TFA entered into force in 2017 – including the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and the war in Ukraine – and suggests how they have amplified, not diminished, the importance of facilitating trade. It then examines how the post-TFA generation of PTAs has approached the need to facilitate trade, analysing common philosophies, shared characteristics, and recent trends. These include the emphasis on addressing deeper, behind-the-border obstacles, the increased focus on electronic means, and the overall move towards greater regulatory depth. A brief look is taken at how regional measures compare with baseline reforms mandated by the TFA, where useful advances have been made and where efforts have fallen short. Lastly, the chapter argues that several TF reforms can potentially deliver positive impacts and suggests specific areas where PTAs might focus in the future to take TF to a new level.

4.2 Changing Landscapes

The growing salience of TF is directly related to a broader transformation of the global trade landscape. Thanks to falling tariff barriers, declining transport costs, and the spread of new information and communications technologies, companies have unbundled their production processes and located the various stages in the most cost-efficient or technologically proficient regions around the planet, knitting every part together through complex, just-in-time transnational trade networks. The last century’s assembly line has become today’s supply chain; the factory floor is now globalised. As a result, modern economies are increasingly dependent on a vast and complex array of global inputs that cannot be supplied by any single country alone. Agricultural production, for instance, requires multiple imports of fertilisers, seeds, pesticides, energy, and advanced machinery to maintain sufficient output. And as production processes become more technologically complex, the supporting supply chains become more complex, too. One of the key manufacturers of the COVID-19 vaccine, for example, depends on sourcing 280 components from nineteen different countries to produce the final product (JDSUPRA, 2021; Bourla, Reference Bourla2023).

Rather than decreasing the importance of TF, today’s highly interconnected global production systems are increasing it. Even modest delays or disruptions in the cross-border delivery of key parts, equipment, or resources can have a ripple effect across supply chains that shut down production, cause goods to pile up in storage, and disrupt shipping, rail, or airfreight logistics. This ultimately restricts global trade flows, preventing businesses from importing critical components, and keeping consumer products off store shelves. These trade and production disruptions can drive up prices, fuel inflation and result in critical shortages of food, medicine, and other necessities. Meanwhile, the experience of COVID-19 lockdowns – and the mass requirement to shift economic activity online – has fuelled growing interest in how digitalisation and automation can be harnessed to improve and strengthen TF. All these challenges and opportunities are reinforcing calls to advance new ‘TF-plus’ initiatives.

How should they advance? On the one hand, many TF issues are inherently global in nature and underscore the logic of trying to reach multilateral solutions. It was one of the factors that allowed WTO Members to adopt the TFA in 2013. Bilateral and regional approaches often did not provide optimal outcomes, as many facilitation measures were of an inherent most-favoured-nation (MFN) nature. It made little sense, for instance, for countries to agree to a single window on that basis – if such a window were built for one trade partner, it would therefore automatically have been built for others as well. It made even less sense to streamline customs procedures or to standardise paperwork bilaterally or regionally, especially for increasingly ‘multinational’ products. Anything less than a multilateral approach to these issues meant complicating, not facilitating, cross-border transactions, and making them more expensive.

On the other hand, many advanced TF initiatives – especially those involving new technologies – are more readily embraced by more developed economies and often beyond the reach or resources of their less advanced partners. During the WTO’s TFA negotiations, several more ambitious facilitation proposals ended up watered down because less developed countries baulked at making binding commitments they feared to entail sizable technological and financial investments. Then there are the related challenges of trying to get 164 countries to agree to multilateral outcomes that may not reflect everyone’s specific trade needs or stages of development. In these circumstances, there is a clear logic in pursuing the next generation of TF measures regionally, especially if they build upon the WTO foundation, advance TF innovations, and can be easily multilateralised if and when other countries want to join. While it is still early to assess the extent to which this renewed focus on TF will be reflected in meaningful new rules and commitments in PTAs, one can already identify a series of noteworthy developments. The following section will take a closer look at these trends, focusing on PTAs concluded during the past five years.Footnote 3

4.3 Love at Second Sight?

A first glance at the PTA landscape seems to suggest intense TF activity. Of the 353 agreements currentlyFootnote 4 recorded in the WTO’s RTA database (listing all RTAs notified since 1958), almost seventy entered into force during the past five years. A closer look, however, reveals that more than half of those treaties were primarily concluded to compensate for EU agreements no longer extending to the United Kingdom (UK) post-Brexit. The vast majority of these PTAs incorporate the relevant provisions of an earlier EU Agreement through a mutatis mutandis application – with only minimal adjustments (referred to as ‘short form agreements’ by the UK government). Only a handful of recent PTAs concluded by the UK fully set out each provision (‘long form agreements’). This is not to suggest an absence of meaningful activity, but the substantiveness of recent PTAs requires a more in-depth analysis.

The launch of the TFA negotiations in 2004 had sparked a sharp rise in TF content of PTAs, lifting it from virtual absence in earlier agreements to forming considerable parts of later treaties.Footnote 5 The scope and substance of TF chapters continued to increase when WTO rulemaking ended a decade later, and the final content of the resulting agreement had become clear. Few PTAs from that period went beyond the TFA – and some remained well below its scope – but TF had become an inherent part of the PTA landscape. This trend continued after the TFA had entered into force in 2017, with most of the PTAs concluded from this time onward, setting out robust TF reforms. Efforts to elevate facilitation to a new level remained limited, however, with governments often focusing their resources on implementing the TFA. New issues moved into the trade spotlight, such as joined initiatives on investment facilitation, e-commerce, and micro-, small, and medium-sized enterprises launched at the WTO’s Buenos Aires Ministerial in 2017.

It was not until a series of events hit the global economy that TF regained a more prominent place on governments’ radar screens. While the impact of Brexit was mostly regional in character, it left a particular mark on the PTA front as the UK’s efforts to reorient its international trade relations triggered an avalanche of agreements. Before they had even entered into force, a pandemic started to spread around the globe, triggering an unprecedented health crisis and delivering a massive shock to the world economy.

The world was confronted with social and economic challenges unmatched in living memory. And as if a serious health crisis had not been enough, it was quickly followed by war, shortages in energy and other essential products, and a rise in inflation. Initial responses exposed some of the fragilities inherent to global value chains and economic interdependence. Protectionist reflexes put a strain on supply chain patterns and negatively impacted stability and logistics costs. Just-in-time production risked being replaced by ‘just-in-case’ strategies.

The scale of the supply chain disruptions triggered worldwide restoration efforts and led to a change in approach. Many of the early export bans were repealed, and a significant part of pandemic-related trade restrictions implemented by G20 economies were removed after a few months.Footnote 6 Governments introduced measures to facilitate the import of key supplies, including lowered tariffs on urgently needed goods, simplified customs procedures and documentation requirements, the establishment of priority channels, and cooperation on regulatory approval.

There was growing awareness that countries that embraced TF had proven more resilient and better equipped to handle the challenges than those that had been slower to do so and were faring less well. Keeping international markets open to trade was increasingly seen as an essential component of the agenda for economic recovery. Initially often considered a mere oiling of the pipes that enable cross-border trade, TF reforms were appreciated as an essential component of the multilateral commercial machinery and the backbone of global supply chains.

Calls for increased facilitation reforms were made on many fronts. Some took the form of advocating the accelerated implementation of the TFA. Recommendations to this end were not only made in various WTO bodiesFootnote 7 but also within the framework of high-level fora such as G20 summits or Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) Trade Ministers meetings.Footnote 8 They focused on advancing full implementation, which the TFA permits the majority of WTO Members to delay.Footnote 9 Several aspects of the Agreement were highlighted as priority areas for such expedited action, including measures relating to publication requirements, pre-arrival processing, separation of release from payments, expedited shipments, border agency cooperation, reduced formalities and documentation requirements, and single window implementation.Footnote 10 Suggestions were equally made to improve the free transit of goods.Footnote 11

Several proposals went beyond the TFA’s scope. In May 2020, for instance, the G20’s Trade and Investment Working Groups complemented their call for accelerated TFA implementation with an encouragement to use electronic documentation and processes, where possible and practical, including the use of smart applications.Footnote 12 Additional TF measures were equally discussed in various WTO fora. They included strengthening pre-arrival procedures, post-release verification and audits to control for compliance, reducing and/or eliminating procedures requiring the physical presence of operators or the submission of physical documents, and, for countries sharing a common border,Footnote 13 cooperation on additional working hours (WTO, 2020, 6–7). Proposals were also made to reduce or eliminate penalties for bona fide mistakes in connection with importing certain products (WTO, 2020, 6–7).Footnote 14

Common to these suggestions was the aim of keeping markets open and trade transaction costs in check. They further sought to strengthen supply chain resilience and to combat corruption and illicit trade.Footnote 15

Much of the attention focused on domestic measures, either as calls for national action or by advocating multilateral initiatives. Many suggestions involved the TFA, which was increasingly seen as offering a way of mitigating the impact of trade tensions and providing an undisputed baseline for cross-border clearance when globalisation had come under strain. Trade facilitation initiatives in the regional context received less attention, but merit closer examination, even if their full impact will require more time to be seen.

4.4 Stepping Stone or Stagnation?

A comparison with the WTO’s TFA is a natural reference point when assessing the role of TF initiatives under the PTA umbrella. The TFA’s impact on earlier regional agreements is well documented (Duval et al., Reference Duval, Neufeld and Utoktham2016; Neufeld, Reference Neufeld and Acharya2016; Kieck, Reference Kieck, Mattoo, Rocha and Ruta2020). It could already be seen when the WTO negotiations were still underway and continued to increase after their conclusion.Footnote 16 The influence extended to the scope and depth of reforms and ranged from conceptual inspiration to using almost identical formulations. The closer the WTO negotiations got to their finishing line, the stronger the alignment became.

However, few of the PTAs from the pre-TFA period went beyond the TF Agreement coverage. A previous analysis of earlier PTAs (covering all agreements up until 2016) found only a limited amount of TFA-plus provisions (Neufeld, Reference Neufeld and Acharya2016). Even PTAs concluded during the first years after the TFA’s entry into force in 2017 rarely went beyond its scope. TFA implementation seems to have absorbed a fair amount of resources, and with most countries already being part of PTAs, the appetite for additional regional action might have been limited.

As far as recent PTAs are concerned, the TFA clearly left a mark on their TF chapters.Footnote 17 The degree of influence varies, however. Some agreements contain an explicit reference with parties affirming their rights and obligations under the TFA.Footnote 18 There are even cases of the TFA incorporated as a whole and made an integral part of a PTA.Footnote 19 The most frequent form of impact is more subtle and of a de facto nature, with PTAs setting out provisions that resemble TFA-mandated reforms.

Despite those differences, one can make out a few broader trends:

1. The first consists of an even further alignment with the TFA. While there are still some PTAs with no reference, this is usually the result of a treaty not containing any TF provisions at all (possibly due to the parties having considered the TFA to offer a sufficient TF framework or due to a narrowly targeted overall scope). Where TF chapters exist, which is the case for most recent PTAs, they almost always show clear signs of having been inspired by the TFA. In some cases, this influence is quite specific and can even take the form of identical or at least very similar language. In others, there is greater adaptation to local circumstances and particular interests, while at the same time showing noticeable traces of inspiration by the TFA.

2. A second tendency is an increased occurrence of TFA-plus measures. While such added ambition remained the exception in earlier PTAs, one finds a significant part of the recent treaties to go beyond the scope of the TFA. In some cases, this is done by introducing an additional level of strength or specificity, such as by using more stringent terms (like ‘shall’ instead of best endeavour language) or by prescribing specific timelines for the execution of an activity.Footnote 20 The more frequent constellation, however, includes entirely new areas, such as provisions on information technology (IT). Thematic focus areas are digitalisation, international standards, and relations with the business community.

3. A related trend consists of a move towards greater technological sophistication, reflecting the availability of new tools. This is hardly surprising considering that most of the TFA disciplines were first introduced almost twenty years ago, with the window for incorporating technical innovation closing at the end of the negotiations nearly a decade ago. Recent PTAs place increased emphasis on digitalisation and electronic means. Unlike the TFA, which often mentions the use of information technologies merely as an option – while equally allowing for less ambitious alternativesFootnote 21 – PTAs no longer seek to soften related disciplines. Many reforms adopted in the context of recent agreements explicitly mandate governments to execute them via electronic means (see, for instance, provisions on pre-arrival processing, publication, or exchanges with the business community). Obligations are also strengthened by less frequently qualifying them with formulations such as ‘to the extent possible’ or ‘as practicable’.Footnote 22

4. Growing emphasis is placed on removing deeper, behind-the-border obstacles. While early PTAs concentrated on improving customs clearance and removing related barriers, new-generation agreements extend their focus to include larger segments of the movement, release, and clearance of goods. This is already reflected in how relevant chapters are headed, no longer referring to ‘customs’ in their titles but opting for the broader ‘trade facilitation’ instead. Many obligations target a wider range of government authorities, focusing not only on customs but equally including other border agencies. Often, they also explicitly include provisions that seek to enhance their coordination.

5. Several red-flag areas encountered during the TFA negotiations have disappeared. While references to automation, for instance, had been a no-go zone with many least developed countries (LDCs) and some developing countries expressing discomfort with the associated level of ambition, this taboo no longer seems to exist. Many PTAs contain specific disciplines on automation, including agreements involving developing (and even least developed) countries.Footnote 23 There are also open references to specific international standards, which had been unacceptable even to some developed countries when the TFA was being negotiated. And several PTAs now openly target illicit trade and corruption, which had initially been attempted during the TFA negotiations but failed to make it into the Agreement’s final draft.Footnote 24

4.5 Third Time Can Be a Charm

In addition to these broader trends, one finds several cases of parties using the opportunity to pick up unfinished business from the TFA negotiating days. They are pursued by a limited group of stakeholders – in particular, the EU, the European Free Trade Association (EFTA), and the US – but in a consistent manner and with noticeable rates of success.Footnote 25 In all instances, these initiatives follow failed attempts to make the targeted measure part of the TFA. Some envisaged reforms date back to pre-TFA days when WTO Members discussed a possible rulemaking exercise and presented initial ideas.

1. A first example consists of efforts to eliminate the mandatory use of customs brokers. The EU sought to achieve a full ban during the TFA negotiations but had to accept a watered-down outcome due to opposition from a group of (mostly Latin American) countries. The finally adopted provision merely prohibits the introduction of new requirements, combined with an obligation to inform of existing practices.Footnote 26 The abandoned goal of outlawing mandatory broker requirements altogether made a comeback in several recent PTAs.Footnote 27

2. A similar objective was pursued in the area of pre-shipment inspection (PSI), which the EU (and other WTO Members) attempted to ban during the TFA talks. The proposal had not been acceptable to the entire membership, however. And as a result, the finally adopted language merely ruled out the practice in relation to tariff classification and customs valuation and encouraged governments not to use other types of PSI.Footnote 28 The unachieved goal of a total PSI ban was now included in some of the recently negotiated PTAs.Footnote 29

3. The EU also spearheaded the attempt to outlaw the calculation of import/export fees and charges on an ad valorem basis, which remained unsuccessful when adopting the TFA.Footnote 30 It was now included in several recent PTAs, not just by the EU, but also the EFTA.Footnote 31

4. Another example of a revived EU negotiating goal relates to the area of transit of goods. During the TFA negotiations, Brussels sought to introduce a national treatment component when proposing measures to improve free traffic in transit. While this attempt failed to meet the consensus threshold mandated under WTO rules, the EU succeeded in introducing a very similar provision in a PTA recently concluded with Ghana.Footnote 32

5. Efforts to outlaw the requirement of consular transactions for importation processes have a particularly long history, dating back to the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) days. A first recommendation to phase out the practice was already made in 1952.Footnote 33 When the TFA negotiations started, the US sought to elevate its status to a mandatory requirement, teaming up with Uganda to launch a joint initiative to this end. Despite the new alliance, and the small number of countries opposing the idea, it ultimately proved impossible to obtain the required consensus to ban the practice. Faced with the choice between watering down the language or dropping the suggestion altogether, the US opted for the latter. The proposal never completely died, however, and made a comeback at the regional level by being incorporated in several recently concluded PTAs.Footnote 34 It also resurfaced at the multilateral level when Norway and the US called for revisiting the need for global action to eliminate consularisation requirements in the WTO’s Trade Facilitation Committee.Footnote 35

6. The US further continued its pursuit of introducing a firm de minimis threshold for customs duties and taxes on express shipments. An attempt to include a related requirement in the TFA had only been partially successful. WTO Members were called to provide for a de minimis shipment value or dutiable amount for which customs duties and taxes would not be collected, aside from certain prescribed goods.Footnote 36 But the obligation was softened by merely asking them to do so ‘to the extent possible’, and efforts to introduce a fixed exemption limit failed to generate consensus. A fresh attempt to create a stronger commitment succeeded a few years later at the regional level in the context of the re-negotiated North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). Article 7.8 of the relevant United States of America, United Mexican States, and Canada Trade Agreement (USMCA) chapter (carrying the same article number used in the TFA) calls for the exemption to apply ‘under normal circumstances’ and sets out a fixed de minimis amount.Footnote 37

7. A final example relates to the coverage of transit disciplines. The EU had long sought to interpret a key GATT provision (Article V) as including the movement of energy goods via pipelines or electricity grids in transit disciplines. Efforts to make this a shared understanding remained unsuccessful during the TFA talks – but Brussels was at least able to preserve that view vis-à-vis its former union member by explicitly including related language in its recent PTA with the UK.

4.6 Where No PTA Has Gone Before

When negotiating the TFA, proponents of ambitious outcomes faced resistance on multiple fronts. Apart from opposition to a particular measure – usually based on specific domestic interests – reservations were often of a broader, systemic nature and fuelled by concerns from two sides. Wary of the WTO’s dispute settlement system, many developing countries and LDCs preferred to keep the scope of new disciplines within (what they considered to be) digestible limits. Developed Members usually wished to aim high(er), both as far as scope and specificity were concerned, but became increasingly mindful of the concessions they were expected to make on the implementation support side. The large range of contracting parties – well over 160 – and their considerable differences in interests and levels of development posed no small challenge to finding an acceptable middle ground. The task was further complicated by the (initially widely unexpected) long duration of the negotiating exercise, not to mention the procedural and political constraints resulting from its embedding in a packing deal setting where progress in one area was contingent on advances on other files.Footnote 38 Concessions were often pocketed without that leading to the unblocking of other issues when progress was lacking on external fronts. This made the middle ground a moving target and frequently led to reforms being watered down during the additional negotiating years that followed. Some measures even had to be dropped altogether as it became clear that they would fail to meet the necessary consensus threshold.Footnote 39 The surviving disciplines were frequently phrased in soft termsFootnote 40 and coupled with extensive implementation flexibilities. Developing countries and LDCs, which make up the vast majority of the WTO’s membership, were allowed to self-determine implementation times and required capacity-building support.

No PTA ever came close to matching such implementation terms. Most of them have no special and different treatment to speak of, and even where certain provisions exist, they tend to be rudimentary and hardly ever exceed aspirational terrain.Footnote 41 Some agreements leave the development of a support pillar for later – usually without setting a deadline – and many do not set out any assistance obligations at all. There are also no PTAs with a comparably large membership. Most of them have less than a handful of contracting parties (if they are not bilateral in the first place), and only a very limited number has more than a dozen signatories. In addition, PTAs do not come without an enforcement mechanism comparable to the WTO’s dispute settlement – a major limiting factor for several countries when considering their willingness to take on certain reforms. And almost all potential PTA partners are already committed to implementing the TFA reforms, allowing for the consideration of additional measures with the benefit of starting from a higher base level.

This begs the question of what could be achieved in the PTA setting – and whether this potential is currently being reaped – even when recognising different aims and purposes of regional and multilateral treaties. While much of the achievable objectives will depend on the respective parties involved, as well as the circumstances in which they are being pursued, there are a number of factors that play a role in assessing a PTA’s potential impact, which will be analysed in the following sections.

4.7 Size Does (Not) Matter

The assumption of a positive correlation between size and ambition may seem intuitive, but does not necessarily find corroboration when analysing the actual content of regional TF reforms. Preferential trade agreements involving economic heavyweights are not always characterised by extensive depth and broad scope – not even when concluded with partners of similar gravitas. And PTAs among smaller players can have impressive reach. Treaties among developing countries do not necessarily lag behind those concluded by more developed partners.

What seems more relevant are points of departure – in the sense of baseline levels of prior engagement in TF. Countries that have already committed to cutting their red tape – be it through domestic, bilateral, or multilateral initiatives – tend to be more open to adding an additional layer of reforms. At the PTA level, governments with a robust facilitation record often follow up on earlier agreements with ambitious successor treaties.Footnote 42

4.8 Geography Continues to Shape Outcomes

Old-fashioned as it may sound, geography matters even in the digital age. As much as operations have become increasingly digitalised, ground realities still weigh heavily. Cooperation between border agencies, for instance, clearly is very conducive to facilitating international trade. For countries without a common land border, the actual scope is far more limited than those sharing a joint frontier (which is sometimes also reflected in the absence of related provisions in PTAs).Footnote 43 Not having easy access to maritime transport – due to being landlocked or as a result of underdeveloped infrastructure – also continues to have a significant impact on the ability to engage in international trade. Distance between PTA partners is also an important factor, as it tends to impact trade patterns and participation in global supply chains. It can also explain the absence of TF provisions in certain areas – such as transit – which should not rashly be equated with representing a TFA minus. In some cases, the lack of measures in one area can also be the result of there simply not being any sizable obstacles, with geography potentially playing an important role. A PTA between advanced economies with ocean access simply may not require any transit provisions, for instance, due to the absence of relevant barriers.

4.9 Volume Does Not Equal Value

First impressions can be misleading. Some PTAs have long facilitation chapters, without size-matching substance. Provisions are phrased in aspirational terms, qualifying the call for action by framing the related commitments in best endeavour terms.Footnote 44 To-do lists may seem comprehensive at first glance, but turn out to be set as a mere basis for future work in soft legal language. There are also cases of committing parties to ‘cooperate’ on a broad range of issues – which can be spelt out in quite specific and ambitious-looking terms – but without mandating concrete actions towards this end.

At the same time, one should not hastily judge the value of such arrangements. In some instances, a single phrase can add value to pre-existing obligations, especially requirements set out in the TFA, such as the insertion of a call for carrying out a measure via electronic means, or by specifying the international standards to be used.Footnote 45

4.10 Good Things Can Come in Small Packages

Similarly, one should not fall into the trap of rigidly equating brevity with absence of ambition. Some TF chapters might be short, but endowed with a high TFA-plus factor due to their design as an add-on instrument.Footnote 46 A small number of provisions can still imply significant reforms if phrased in strong terms. Implementation flexibilities equally play a role, especially when considering the time horizon of actual changes on the ground. Given the widespread lack of possibilities to delay or request capacity-building support, reforms can be relatively quick when set out through the PTA track. There are further cases of interim outcomes with parties agreeing on certain measures while indicating their intention to add additional measures at a later time. An accurate assessment of ambition levels therefore requires careful analysis and a detailed look at the fine print.

4.11 Fears of Duplication May Be Overrated

When considering measures for adoption in a PTA, their inclusion in the TFA should not serve as a deterrent on the grounds of fear of duplication. Apart from the fact that disciplines are rarely phrased in identical terms, the different implementation modalities already ensure a complementary role. The absence of the TFA’s extensive flexibilities alone would add an additional layer of commitment, even in the case of matching provisions. Not having the ability to self-determine implementation dates, for instance – without an upper limit – clearly influences when a measure’s impact can be expected on the ground.

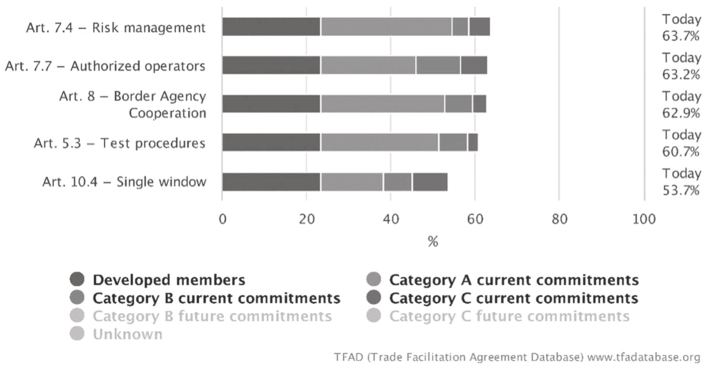

This becomes all the more relevant when considering that current commitment rates for some of the most impactful TFA measures leave room for upward movement. Only slightly more than half of all WTO Members are currently bound to have established a single window, for instance, even though the TFA sets out the related obligation in best endeavour terms. Little more than 60 per cent are already committed to border agency cooperation, despite its important role in enhancing supply chain resilience and reducing illicit trade (see Figure 4.1).

When seeking to enhance facilitation at the regional level, there are a few lessons to be learned from the COVID-19 crisis. The pandemic clearly underlined the importance of global supply chains, but also exposed their vulnerability. With many of the production and distribution networks currently under review, thought should be given to optimising – and in some cases redrawing – existing trade and supply chain maps with a focus on the areas most affected by the crisis, which continues to be a stress test to the current system.

Trade facilitation initiatives in PTAs can be an important component of such endeavours. Countries seeking to improve their integration into global production networks could use the PTA track as a (complementary) tool in their efforts to remove border bottlenecks and transform them into gateways for their imports and exports. Consistently pursuing improved access to regional production networks could further promote the expansion of global value chains and enhance their resilience.

While substantive focus areas will differ, depending on the parties’ circumstances and priorities, certain aspects frequently promise particular gains. Automation is one such area with considerable potential, especially in developing economies. Even in developed countries, there is noticeable room for improvement. The TFA does not once refer to automation when setting out its requirements due to reservations from some WTO Members at the time of its negotiation. And while concerns seem to have eased since then as automated systems have become widely used, it would not be easy to introduce upgraded requirements at the multilateral level – and certainly not a speedy process.

Enhancements are also still to be achieved on the other end of the technology spectrum, such as with respect to access to trade-related information. It may seem surprising, but the publication of that information featured prominently on the list of measures highlighted as meriting particular attention when identifying TFA measures with a special need for fast-track implementation (WTO Committee on Trade Facilitation, 2021a).

The COVID-19 crisis highlighted additional issues with particular relevance for enhancing supply chain resilience and keeping trade flows open, such as measures to facilitate the release and clearance of goods. A look at the TF initiatives taken by many governments at the onset of the pandemic shows that they often included improvements in the areas of electronic payment, separation of release from clearance, and pre-arrival processing. Measures were also taken to improve border agency cooperation and to accelerate the release of perishable goods. The majority of those measures were designed to be temporary in nature – and enacted with little leadup time – but the experience seems to have been positive, and several WTO Members saw merit in continued – and sometimes also accelerated – initiatives in those areas.Footnote 47

4.12 New Progress or Unused Potential?

Some of the recent PTAs appear to already have taken those aspects on board. And while there may not have been seismic shifts when comparing them to their earlier counterparts, one can find a steady evolution towards more modern approaches and the incorporation of recent information technologies. Trade Facilitation Agreement-plus commitments are still largely limited to a few core areas (such as an increased call for the use of electronic means or alignment with specified international standards), but are noticeably more frequent than in PTAs from an earlier period. There are also several cases of added specificity, such as by introducing time limits for the completion of certain actions (like releasing goods or issuing advance rulings).

At the same time, progress remains incremental. Few of the recently concluded PTAs really seek to push facilitation to the next level. There are also still agreements with no or only very limited TF content,Footnote 48 as well as cases where substance is left to be defined in future, yet to be negotiated terms.Footnote 49

Additional progress could especially be achieved in the area of digitalisation, where technological innovation continues to open up new possibilities – and where the TFA no longer reflects the latest state of play. The benefits of improvements in this area are substantial. A recent study for the Asia-Pacific region found that further acceleration of digital TF could cut average trade costs by more than 13 per cent (UNESCAP, 2021). This potential is increasingly recognised at the highest political levels, as reflected in G20 declarations and Ministerial statements. Calls for additional measures in this area are also repeatedly made by industry groups.Footnote 50 Several regional groupings, such as the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) or the Eurasian Economic Union already adopted strategies that include digital initiatives as a priority area.Footnote 51

Introducing such reforms through the PTA channel would come with the benefit of a more flexible framework due to the absence of institutional constraints inherent to the WTO rulemaking machinery. While multilateral rules under the WTO umbrella remain the best option for achieving broad and sustainable advances, they are notoriously hard to agree upon and usually take a long time to become a reality.

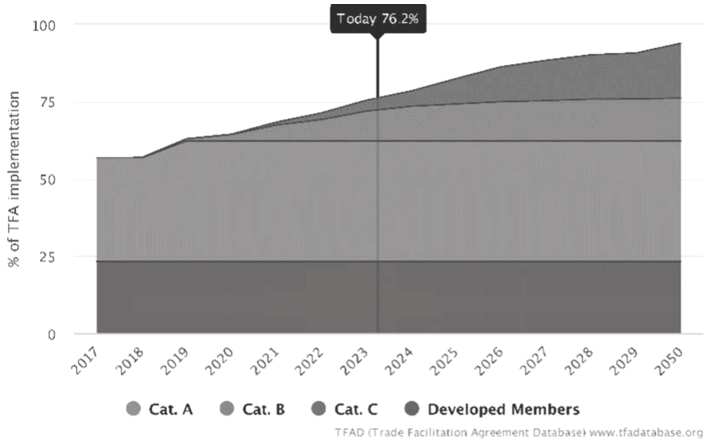

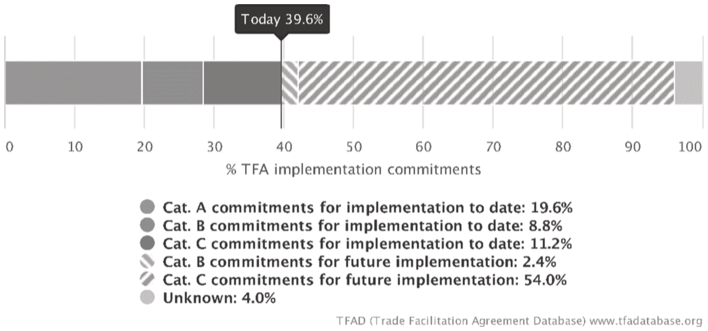

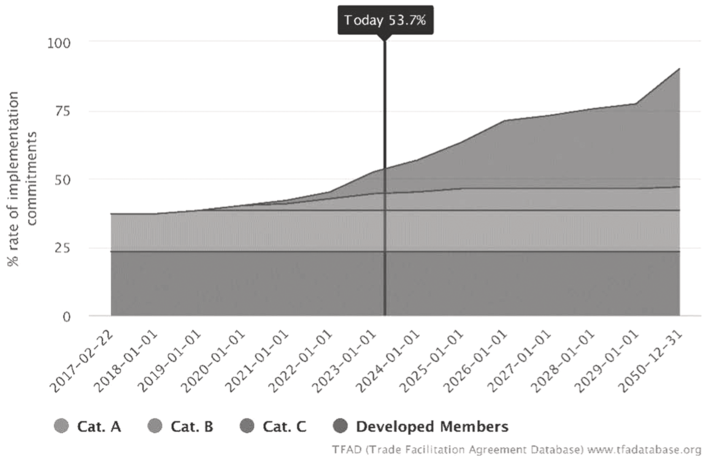

Even for measures already included in the TFA, there is often room for taking reforms to the next level, or for at least accelerating their actual application on the ground. The design of the TFA’s architecture makes implementation a gradual process, and its full impact will only emerge over time. According to the WTO’s Trade Facilitation Agreement Database (WTO, 2023), six years after the TFA’s entry into force, the global rate of implementation commitments stands at 76 per cent (see Figure 4.2).Footnote 52 Broken down by Members’ levels of development, this number is noticeably lower, sometimes barely exceeding 40 per cent.Footnote 53

Figure 4.2 Timeline of TFA implementation commitments.

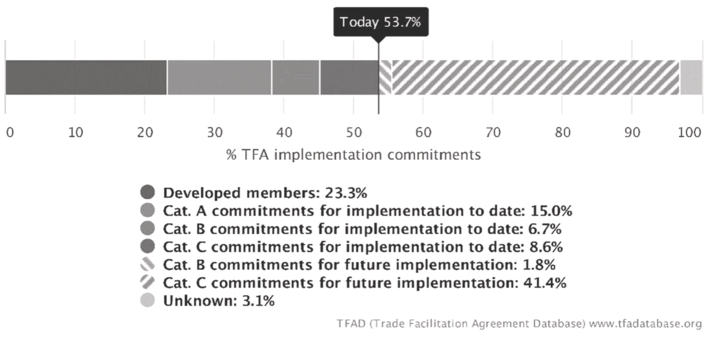

Current implementation rates for measures that are widely considered to be particularly impactful are even lower. Global commitment to establishing a single window, for instance, only stands at slightly above 50 per cent (see Figure 4.3), even though the obligation is phrased in best endeavour terms (WTO, 2023). For developing countries and LDCs, the number does not even reach 40 per cent (see Figure 4.4) (WTO, 2023), despite the possibility of requesting capacity-building support.

Figure 4.3 Implementation commitments for single window implementation – all members.

Figure 4.4 Single window implementation commitments – developing countries and LDCs.

Based on those commitments, it will take at least another twenty-five years until one can expect full single window implementation by all WTO Members. While the numbers continue to go up as transition periods expire, it will take a while for all reforms to be applied by the entire WTO membership and for all related benefits to fully kick in (see Figure 4.5).

Figure 4.5 Global timeline of single window implementation commitments.

Implementation rates of additional measures with particular relevance for facilitating the global exchange of goods also leave room for improvement. According to the WTO’s Trade Facilitation Agreement Database, little more than 60 per centFootnote 54 of WTO Members have current commitments to implement the TFA’s provisions regarding border agency cooperation, and this despite a considerable level of built-in flexibility (such as merely mandating collaboration among countries sharing a common border on mutually agreed terms and ‘to the extent possible and practicable’).Footnote 55 Risk management numbers are roughly the same level (63 per cent). Measures to reduce formalities and documentation requirements have currently been committed to by less than three-quarters of the WTO’s membership, despite a series of built-in flexibilities.Footnote 56

Many of these measures could be especially impactful when pursued in a consistent manner and with coverage of a large segment of global value chains. The recent COVID-19 crisis has already led to a few cases of concerted action in several PTAs, reducing various barriers to trade (such as simplified customs procedures and the introduction of expedited clearance channels).Footnote 57

Engaging in such reforms would further come with the additional benefit of testing the ground for possible follow-up at the multilateral level, similar to the cross-fertilisation witnessed during the TFA negotiations when negotiators took inspiration from measures successfully applied in a regional setting.

4.13 Towards Trade Facilitation 2.0

The increased focus on facilitating trade is happening despite – or perhaps, because of – the major headwinds that trade negotiators face in trying to advance a broader trade liberalisation and integration agenda. Already grappling with the fallout from COVID-19 lockdowns and escalating US–China trade frictions, negotiators are now confronting a host of new challenges arising from the Ukraine war, slowing global growth, and rising inflation. If this were not enough, UK negotiators face the additional task of trying to recast their country’s international trade relations in the wake of the 2016 Brexit vote. This confluence of challenges – or ‘poly-crises’ – risks fuelling new protectionist pressures and undermining political support for further trade opening.

Yet, paradoxically, this unprecedented tsunami of problems has made TF all the more important. Today’s increasingly integrated and interdependent global economy places a growing premium on TF – the ability to move resources, components, and finished goods swiftly and seamlessly across national borders. At the same time, digitalisation, automation and other technological innovations provide valuable new tools for making this happen. Although global initiatives in the WTO remain the first-best option for advancing trade facilitation efforts, the reality is that PTAs might offer the most viable pathway ahead in the near term because they involve like-minded countries, are generally easier to negotiate, and can be more easily tailored to reflect countries’ technological capacities, financial resources, and trade needs. They can be especially impactful when pursued in a consistent, consolidated manner. As long as TF measures in PTAs are consistent with WTO rules, are non-discriminatory in their application, and aim to build upon its foundation, they can spearhead and advance TF innovations that could ultimately help inspire and guide future multilateral efforts. In doing so, they could also contribute to turning the vast web of regional TF reforms into a more streamlined trading regime that covers all key stakeholders in global supply chains and becomes part of a broader transformation of the global trade landscape.

In analysing how a new generation of PTAs might approach the continued need to facilitate trade, this chapter has suggested that the regional TF reforms with the potential to deliver the greatest positive, real-world impacts are those aimed at harnessing digitalisation, automation, and the use of other electronic means to modernise cross-border transactions and to ensure that national systems are interoperable and seamlessly integrated. Progress in these critical areas would not just elevate existing TFA requirements to a new level. More importantly, they would bring TF rules and disciplines up to date with modern trading realities. These changes are already underway in a growing number of practical cases. But there remains a task for negotiators to codify these practices – and the underlying innovation – and to anchor them in trade agreements so that new ‘rules of the road’ are transparent, predictable, and secure.

This chapter also argues these various regional efforts should, whenever possible, share common approaches, similar characteristics, and parallel goals – minimising the risk of conflict or confusion and maximising the potential for complementarity and convergence. This is particularly important when the focus is on addressing deeper, behind-the-border obstacles and when efforts to harness digitalisation and automation, almost by definition, need to be non-discriminatory. But while a renewed regional focus on TF rulemaking makes sense – and is clearly needed in a world of disrupted supply chains, rising inflation, and growing economic uncertainty – much work remains to be done. If more steps were to be taken in that direction, TF could be taken to the next level and, indeed, become a new frontier.