Introduction

The study of occupational structure and occupational stratification, defined as the relationship between occupational structure and group belonging, are at the core of numerous studies concerned with social inequality in contemporary and historical societies (Archer Reference Archer1991; Blau and Duncan Reference Blau and Duncan1967; Darroch and Ornstein Reference Darroch and Ornstein1980; Friedlander Reference Friedlander1992; Gudmundson Reference Gudmundson1983; Klein and Ogilvie Reference Klein and Sheilagh2016; Tjarks Reference Tjarks1978). This literature finds that the association between occupation and social status is strong and pervasive in premodern and in modern societies alike (Katz Reference Katz1972).

The historiography suggests that occupational stratification played a major role also in colonial societies. Colonial societies often relied on a social and economic hierarchy heavily shaped by European racial perceptions (Samson Reference Samson2005: 32; Staum Reference Staum2003: 5). In such context, the opportunities for socioeconomic advancements for the groups at the bottom of the hierarchy could be very limited, although not necessarily fully restricted (Staum Reference Staum2003: 5).

By relying on population-wide census data, the present study sheds light on the economic structure and on the occupational stratification that characterized a West African colonial society in the early nineteenth century. The early colony of Sierra Leone Footnote 1 is a valuable case study for analyzing the relationship between socioeconomic status and group belonging.Footnote 2 The colony had been founded in the late eighteenth century on the West Coast of Africa as a refuge for black settlers who faced racial discrimination in predominantly white societies in the Americas and in Europe (Dresser Reference Dresser2016: 170; Pybus Reference Pybus2007: 98–99). Footnote 3 In a few decades, the population of the colony had grown into a highly heterogeneous mix of individuals made up of black settlers, whites, mixed-race, and indigenous Africans. Furthermore, the colony allegedly rested on principles of fairness and equality, which renders this case study all the more valuable in the panorama of colonialism (Fyfe Reference Fyfe1962: 15; Samson Reference Samson2005; Schwarz Reference Schwarz2017: 31; Thorpe and Wilberforce Reference Thorpe and William1815: 15). The present study, therefore, contributes to the literature on social stratification at large, and occupational stratification specifically, with rare and early evidence from colonial sub-Saharan Africa.

After a brief historical note on the colony of Sierra Leone, the study proceeds onto examining the socioeconomic structure that emerges from occupational title data. The latter part of the study is devoted to the study of occupational stratification by unveiling whether an association between socioeconomic structure and group belonging can be identified. If an association is positively identified, the study ultimately intends to examine its characteristics.

The Colony of Sierra Leone

The colony of Sierra Leone by 1831 had already undergone multiple changes. From a sparsely populated, virtually independent colony inhabited by freed slaves from both sides of the Atlantic, Sierra Leone had grown into the largest resettlement center for liberated slaves in the whole of Africa governed by a crown-appointed colonial government, all in less than four decades (Fyfe Reference Fyfe1987).

The target of the interests of numerous European powers attracted by the advantageous characteristics of its natural harbor, since the sixteenth century the area had seen various trade outposts being established along the Sierra Leone’s estuary (Dorjahn and Fyfe Reference Fyfe1962). Nevertheless, the high mortality rates of Europeans gained the area the grim nickname of “White Man’s Grave” and impeded any long-term European occupation until well into the eighteenth century (Curtin Reference Curtin1964, 1: 177–79; Rönnbäck et al. Reference Rönnbäck, Öberg and Galli2019).

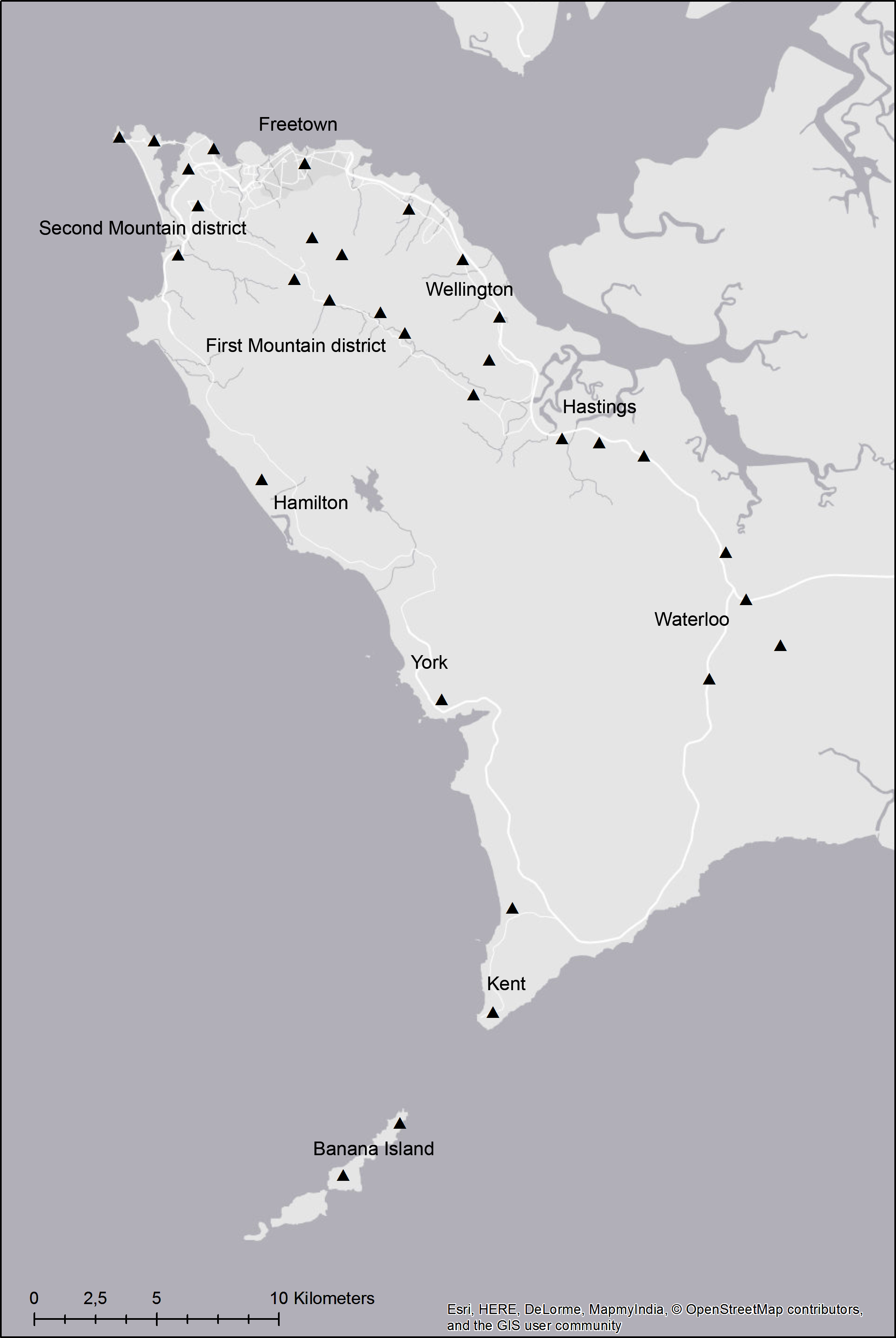

The colony of Sierra Leone was eventually founded only in 1787, the first British colony in the aftermath of the American Revolutionary War. Initially, the colony did not extend beyond the shores of current-day Freetown (Dorjahn and Fyfe Reference Fyfe1962). Gradually, however, the colony expanded into the rest of the Freetown peninsula, after a lengthy process of land dispossession at the expense of the indigenous groups of the area (Schwarz Reference Schwarz2017: 25–27). Figure 1 shows the area of the colony in 1831, along with the settlements that had been founded in the peninsula by that time.

A rapid rise in population, imputable mostly to migration, corresponded with the geographical expansion.

The first settlers to reach Sierra Leone had been a blend of “destitute blacks” Footnote 4 and indigent whites from the United Kingdom, who had landed in 1787 in the area of modern-day Freetown (Asiegbu Reference Asiegbu1969: 5–6; Ingham Reference Ingham1894: 5). Only a handful of these first settlers survived the first couple of years in the colony, decimated by epidemics and conflicts with the indigenous population over land (Fyfe Reference Fyfe1962: 18–21).

In the following years, other groups of blacks from the Americas landed in the colony, rescuing the “utopian project” from disappearance: the Nova Scotians and the Maroons (Colonial Office 1827b: folio 9; Scanlan Reference Scanlan2016: 1093). The two groups, although different in many ways, gradually fused into the original settler macrogroup, whose descendants came to be known as “colonial residents” for their long-lasting connection with the colony (Wyse Reference Wyse1993: 343–49). The Nova Scotians, slaves who fought along the British lines in the American Revolutionary War, had sailed from Canada to Sierra Leone in 1792. Some of them had been born slaves in the United States, others had crossed the Atlantic on slave vessels later to be sold to plantation owners (Colonial Office 1791). In spite of their different origins, the Nova Scotians shared the experience of enslavement, freedom, and the difficult adaptation to the life in Nova Scotia.Footnote 5 Along their journey, they had embraced Christianity and developed into congregations around preachers of different denominations (Fyfe Reference Fyfe1977: 176; Sidbury Reference Sidbury2015: 129–31). A sense of community, strengthened by a common faith and similar challenges, led them to petition the British government for their removal from Nova Scotia to Sierra Leone, what they saw as their “province of freedom” (Byrd Reference Byrd2001, pt. III; Peterson Reference Peterson1969). Differently than the Nova Scotians, the Maroons were members of a community of runaway slaves from Jamaica that came to be deported to Nova Scotia by the Jamaican government, fearful they posed a threat to the slave plantation system. In 1800 they, too, sailed to Sierra Leone (Lockett Reference Lockett1999).

Following the adoption of the Slave Trade Act in 1807, other black settlers began landing in the colony. The British authorities had chosen Freetown as the judicial capital of antislavery, where slave traders and their vessels could be adjudicated (Bethell Reference Bethell1966). As a result, slaves captured from slave vessels, known as recaptives, began landing and settling in the colony, a process of involuntary migration that continued until the 1860s (Scanlan Reference Scanlan2016: 1094; Schwarz Reference Schwarz2012: 177). The recaptives originated from an area that extended from Senegambia to Angola, and further to East Africa (Fyfe Reference Fyfe1987: 412; McDaniel Reference McDaniel1995: 25). Soon, however, the colonial authorities found themselves unable to provide for the recaptives, having failed to foresee the magnitude of the inflow (Thorpe and Wilberforce Reference Thorpe and William1815: 15). Ways of disposing of these recaptives were devised: enlistment in the military, apprenticeship,Footnote 6 and settlement in remote and newly acquired areas of the peninsula (Anderson Reference Anderson2013; Scanlan Reference Scanlan2016). Owing to their experiences of enslavement and liberation, the recaptives who landed and settled in the colony came to be identified by the authorities as “liberated Africans.” The term gave account of the recaptives’ relation to the colony and of their common African, yet heterogeneous, origin. Similarly, those recaptives who had been enlisted for military service after capture became known as “discharged soldiers” upon returning to the colony after discharge from British Army in 1820–21 (Anderson Reference Anderson2013; Fyfe Reference Fyfe1962: ch. VI).

As a result of the growing importance of the colony for the economy of the region, indigenous groups voluntarily migrated to Sierra Leone. Muslim Fula and Mandinka, along Temne and Mende, all settled in the colony more or less permanently (Flory Reference Flory, Paul and Suzanne2015: 258; Fyfe Reference Fyfe1962: 149). Despite a high degree of heterogeneity, these groups came to be known within the colonial framework as “native strangers,” to distinguish them from other settlers while stressing their indigenous origin. Another group of Africans, that of the KruFootnote 7 from modern-day Liberia, also settled in the colony for economic reasons, although mostly temporarily (Frost Reference Frost1999: 26–32). The colonial population counted also a few Europeans and mixed-race, defined as “mulattoes” in the colonial recordsFootnote 8 (Macaulay Reference Macaulay1826:16).

Kenneth Macaulay, governor of Sierra Leone in 1811 and defender of the colony and of its ideals, in his pamphlet The Colony of Sierra Leone Vindicated (1826), described the group hierarchy of Sierra Leone, where individuals were ranked depending on their degree of identification with the colonizers’ culture (Harrell-Bond et al. Reference Harrell-Bond, Howard and Skinner1978: 6–10; Macaulay Reference Macaulay1826: 16). According to this evidence, it would seem that, in the colony of Sierra Leone, one’s place in society was influenced by the colonial hierarchy.

Occupational Titles in Sierra Leone in 1831

This study relies on data from the 1831 Census of the Population of the Colony of Sierra Leone (Colonial Office 1831). Although demographic survey in Sierra Leone had a tradition dating back to 1802, just 15 years into the colony’s existence, it was only in 1831 that the first door-to-door census of the colony was carried out, allegedly enumerating the whole population including recaptives (Kuczynski Reference Kuczynski1948: ch. 2).Footnote 9 Although little is known on the motives for the census, the aim seem to have been to provide the English government with a picture of the colony intended to counteract the growing opposition to the colonial venture and the claims of reenslavement that circulated in England at the time (Colonial Office 1827b, 1842; Macaulay Reference Macaulay1826).Footnote 10

The census relied on standardized forms filled in by specially appointed officers in the capital, or by local government officials in the countryside (Kuczynski Reference Kuczynski1948: 23). The source is generally considered as a reliable picture of the colony as appearing in 1831 (Howard Reference Howard2020: 108). However, it should be interpreted with caution as all colonial sources. Census takers were representative of the colonial authority, and therefore likely to interpret reality according to the colonial outlook. Furthermore, subjective biases in the interpretation and categorization of reality are likely to affect the source, calling for caution when drawing evidence.

The information gathered in the census included name, group belonging, and occupational title of the household head (and, in some cases, of other household members), along with information pertaining to household composition. Group belonging informs on how individuals were categorized and perceived by the colonial authorities, although it is unclear if individuals self-identified or were assigned into these groups by the census takers (ibid.: 105). However, the variable does not inform on individual self-perception. Individual self-perception was more complex than portrayed in the source, especially in the case of groups characterized by numerous subidentities. In the case of liberated Africans, hundreds of ethnic identities underwent a process of reconceptualization and adaptation to the new context (Northrup Reference Northrup2006: 3–4). This resulted in the “creation” of groups that neither reflected purely precapture ethnic divisions nor fully matched the authorities’ grouping system.Footnote 11 Unfortunately, the source does not grant to control for within-groups identities but only consents to determine whether the institutional group division was associated with different socioeconomic outcomes. This is nonetheless worth studying as previous historiography has argued for the impact of colonial hierarchy on occupational stratification (Samson Reference Samson2005). It is therefore important to stress that the present article limits to occupational stratification as perceived by the authorities, and not by the individual settlers of the colony.

Coverage

Although part of one single collective effort, data collection differed between rural and urban areas. Household-level data were collected in the countryside, whereas individual-level data characterized the urban survey. As a result of the differing structure of data collection across the colony, occupational data coverage is higher in the urban area of Freetown and lower in the countryside.

Despite geographical differences, occupational titles are available for 48.8 percent of the entire population, or 14,154 individuals.

The source provides occupational data for 83.9 percent of the male adults residing in the colony, 19.7 percent of the adult females, and 31.5 percent of the children. More than 85 percent of the adult males were associated with an occupational title in the countryside, whereas the share was less than 1 percent for adult females, corresponding only to household heads. Occupational data were more evenly collected in the urban area: 79.5 percent of the adult men and 63.1 percent of the adult women had an occupation recorded. Children’s occupational titles amounted to 26.7 percent in the urban area and to 33.4 percent in the countryside.

Although not a praxis exceptional to Sierra Leone, data collection concentrated on adult males, particularly in the countryside. Women were often labeled simply as wives or daughters of the male household head. Nevertheless, it is established that many of the women that went unrecorded were occupied (Maier Reference Maier2009). Historiographic and anthropological evidence suggests that in precolonial West African societies, women were involved in functions that spanned from reproductive to productive, often being responsible for duties that in Europe would have been carried out by men (Austin Reference Austin2005: 108; Maier Reference Maier2009). Such duties included agriculture, with the exception of land clearing and harvesting, food processing, and manufacturing (Clarke Reference Clarke1863: 330–31; Martin Reference Martin and Robin2002; Rönnbäck Reference Rönnbäck2016: 77–78). From small-scale trade in produce to intermediary positions within long-distance trade, women played also a key role for trade in Sierra Leone (Coquery-Vidrovitch Reference Coquery-Vidrovitch1997: 30–32; Howard Reference Howard2020: 103; Law Reference Law2002: 202). Owing to the opportunities that the busy Freetown harbor offered, some women even succeeded in securing contracts with the navy (White Reference White1981). Although qualitative evidence claims that women categorized as colonial residents, recaptives, and native strangers often working in trading or in other occupations, it remains impossible to estimate the magnitude of the phenomenon.

Table 1 shows that children were also often overlooked by the census takers when it came to recording their occupational titles. Evidence suggests, however, that children were an integral part of the West African labor function, both within and outside the household. Kin relations determined whether children would contribute with their labor to their mother’s or to their father’s activities (Austin Reference Austin2005: 110). Qualitative evidence for the colony of Sierra Leone is limited and does not consent to determine the extent to which children were occupied, if unrecorded, although recaptive children made up a large part of the labor force in Sierra Leone (Melek Delgado Reference Melek Delgado2020: 97). Furthermore, education played an important role since the colony’s early days and households tended to send their children to school if they could afford it (Harris Reference Harris and Harris1993: 52–53). In the present study, I chose not to exclude women and children from the examination despite information being available for a small share of the individuals in these groups. I argue that by completely excluding these groups from the study the picture would not be more reliable, but more likely to represent an occupational structure biased toward predominantly male occupations.

Table 1. Professional titles availability, % of population by area and demographic group

Source: Author’s elaboration based on Colonial Office, 1831.

Table 2 reports occupational title availability by group as appearing in the source. It emerges that not all groups were recorded to the same extent.

Table 2. Occupational title availability by group

Source: See table 1.

* As presented in the source.

Information on occupational title is available for the vast majority of Europeans, 85 percent, followed by the “unspecified” group,Footnote 12 81.4 percent. The coverage for liberated Africans and native strangers amounted to 52.3 and 46.9 percent, respectively. Colonial residents, “mulattoes,” discharged soldiers, and Kru record the lowest shares of occupational information in the whole sample.

A category that requires some clarifications is that of unqualified “natives” (table 2). In the rural part of the census, special columns accounted for “natives” working in-house for settlers’ households. In contrast to the indigenous individuals recorded in Freetown, the natives appearing in the rural census were only qualified by the term “native.” Although much has been written on the indigenous groups who populated Freetown, only scant evidence exists regarding the natives recorded in the countryside. According to the Report of the Commissioners for Sierra Leone for 1827 (Colonial Office 1827b), these unqualified “natives” belonged to indigenous groups from the nearby hinterland, most likely Temne. The limited evidence available suggests that they sought only temporary employment within the colony’s boundaries, although it is neither clear how long they would remain nor what their occupation would be (ibid.: folios 16–17). Due to the very limited information available on this group, I have opted to exclude them from the analysis.

Occupational Titles

In the primary source, 102 unique occupational titles were identified. The titles covered all major occupational groups: from government officials to traders, from blacksmiths to tailors and farmers.

Synonymic titles recorded in the primary source were merged with the aid of the HISCO classification system (Historical International Standard Classification of Occupations) (Leeuwen et al. Reference Leeuwen, Maas and Miles2002; see appendix A2 for the standardization process). The classification of the occupational titles into socioeconomic groups required further refinements. All occupational titles were ranked according to the HISCLASS scheme (Historical International Social Class Scheme), a 12-level ranking of occupations based on the HISCO classification scheme (Leeuwen and Maas Reference Leeuwen and Maas2011). The choice of which classification scheme to employ is a sensitive choice, as it requires balancing different interests: the aim for comparability across space and time with the fact that these tools tend to have been developed to describe Western realities. The issue of conceptual Eurocentrism is not unsurmountable, however. In this regard Gareth Austin argued that “the fact that an idea was inspired by experience outside Africa does not mean that it is necessary unhelpful to Africanist. Whether it is or not is an empirical question.” Much attention was therefore paid to the adaptability of alternative classification schemes to the context of nineteenth-century Sierra Leone. For this purpose, the HISCO/HISCLASS classification schemes were preferred to other schemes for the clear historical perspective and the aim of comparability across space and time.Footnote 13

In light of the need for adaptability, I found it appropriate to adjust the HISCLASS ranking in the case of traders. Footnote 14 Previous research suggests that traders played a key role in the colony of Sierra Leone and enjoyed high socioeconomic status due to the centrality of their role within the colonial economy (Dorjahn and Fyfe Reference Fyfe1962; Mitchell Reference Mitchell1962). It was traders who provided the colony with foodstuff due to the colony’s inability to produce for food self-sufficiency until well into the latter part of the nineteenth century (McGowan Reference McGowan1990: 25; Misevich Reference Misevich2008). Traders also appropriated the highly valuable trade in prizes—the goods found aboard slave vessels condemned at Sierra Leone—with their wealth rivaling that of European merchants (Fyfe Reference Fyfe1962: 203–4). In light of the historiographic evidence specific to Sierra Leone, traders were upgraded from HISCLASS 4 to HISCLASS 2.Footnote 15 For analytical purposes, the 12 socioeconomic groups were further arranged into four major categories: elite, middle, farmer, and lower group.

Socioeconomic Structure

Sierra Leone was characterized by a small, powerful elite group, made up of high government officials, professionals, and well-connected commercial agents. The elite group accounted for 1.9 percent of the total, of which 1.6 percent was made up of merchants and traders alone. Owing to the favorable characteristics of the Freetown harbor and the numerous international and regional trade routes centered on the colony’s capital, Freetown had emerged as a major trading hub for the whole of West Africa (McGowan Reference McGowan1990; Mitchell Reference Mitchell1962). The importance of Freetown for trade had further grown as a consequence of slave trade abolition, which allowed new trades in captured vessels and their content (Scanlan Reference Scanlan2014). In light of the many opportunities for trade, a number of merchants and traders had decided to take residence in the colony, mostly in the capital. Merchants’ activities concentrated on filling the gap left by the disappearance of the Sierra Leone Company, which had aimed at developing a profitable import-export business between the colony and England (Howard Reference Howard2020; Lovejoy and Schwarz 2015). Although the company had ended in failure, its space was quickly filled by a private entrepreneurs recorded as merchants (Scanlan Reference Scanlan2014). They required large amounts of capital and well-developed networks, readily available to individuals who had served for the Sierra Leone Company with connection to English bankers and investors (Fyfe Reference Fyfe1962: 203). Footnote 16 After the company’s collapse, a number of its officials had remained in the colony assuming governmental posts. It was not uncommon that, after their appointment, colonial officials continued their trading activities, a situation that gave often rise to conflicts of interests (Cox-George Reference Cox-George1961: 26, 79). Even after leaving the colonial administration, administrators-turned-merchants enjoyed notable power and remained involved in policy making, although not officially (Cox-George Reference Cox-George1961: 26). Traders, in contrast to merchants, could be also found in the countryside, particularly in the village of York along the western coast of the peninsula, where commercial activities were more developed (Galli and Rönnbäck Reference Galli and Klas2020). Traders were predominantly involved with trade between the colony and its hinterland, often revolving around the colony’s food provision. They would purchase foodstuff inland to be sold later in the colony, or ivory and other luxurious goods to be sold to merchants for export to Europe (Fyfe Reference Fyfe1962: 101). Some traders also operated as local intermediaries for merchants, from whom they differed due to lower availability of capital and networks. Merchants often advanced goods to these traders on credit in a relationship built on trust (Newbury Reference Newbury and Claude1971: 98). Government officials, clergymen, physicians, attorneys, schoolmasters, and teachers constituted the remainder of the elite group.

The middle group accounted for nearly 15 percent of the individuals with a trade.Footnote 17 Among them we find naval officials, clerical personnel at the dependence of the colonial government, skilled workers and manufacturers, petty traders, and construction workers. Small-scale traders and other sales personnel accounted for 5.3 percent of the total. In contrast to merchants and traders, this latter group focused on the local market, setting up small shops or market stalls in the vicinity of the navy headquarters or in populous areas of the capital (Fyfe Reference Fyfe1962: 141). Women made up a substantial share of this group, similarly to what was commonly observed in other pre- and postcolonial West African societies. Petty trading was almost solely a female occupation, likely as a result of the limited skills and capital required to pursue small commercial activities, a pattern observed by contemporary sources in Freetown (Austin Reference Austin2005: 107–9; Clarke Reference Clarke1863: 330; Coquery-Vidrovitch Reference Coquery-Vidrovitch1997: 30–32; Law Reference Law2002: 202). Although in the source no trace of female commercial actors in the countryside is recorded, trade was carried out in the form of marketing of agricultural produce and manufacture, yet it is impossible unfortunately to estimate to which extent.

Carpenters and other skilled construction workers made up an additional 5.1 percent of the middle group. Construction was a relevant activity at a time when the colony was in the midst of a construction boom, with infrastructures and housing being in great demand (Howard Reference Howard2020: 102; Macaulay Reference Macaulay1826). The vast and rapid increase in population required the foundation of new settlements in previously uninhabited areas of the peninsula, boosting the demand for new buildings and infrastructures. Additionally, housing had a status-symbol function in Freetown (Galli and Rönnbäck Reference Galli and Klas2020). Various sources confirm the impression that Sierra Leone, and Freetown in particular, was in a state of a building frenzy, with a qualitative source affirming that land in Freetown had become already contested in the early nineteenth century, with land and housing prices skyrocketing between the 1820s and 1830s (Fyfe Reference Fyfe1962: 143).

Farmers accounted for nearly 28 percent of the total, while fishermen contributed with a further 1.6 percent. Although no intrinsic differentiation between large and small landowners emerges from the source, the socioeconomic status of large landowners may have differed from that of small subsistence farmers. Table 4 reports landholding size for individuals recorded as farmers. The average landholding size was of 3.5 acres, yet 1.5 percent of those with farming as their trade owned no land at all and nearly 20 percent held plots smaller than 1 acre. Of the remainder, 68.5 percent declared that they owned plots in the range of 1 to 35 acres, while only a small minority, 0.4 percent of the total, owned plots above 35 acres, Footnote 18 with the biggest single landholding recorded in the colony being of 90 acres.

Table 3. Occupational categories, Sierra Leone 1831

Source: Author’s elaboration based on Colonial Office, 1831.

Land was, however, not a sole prerogative of farmers. A large number of settlers with other occupations recorded also held small plots. Despite the large number of individuals involved with agriculture either as a primary or secondary occupation, contemporary sources argued that the colony consistently failed to produce enough for self-sufficiency to the extent that Freetown’s survival relied on food supplies from neighboring regions (Colonial Office 1827b, 1842; Fyfe Reference Fyfe1980; McGowan Reference McGowan1990). Trade records show that the colony exported only minor quantities of agricultural produce, mostly ginger, palm oil, and ground nuts (Colonial Office 1842: folio 53). Although since its foundation the colony had been characterized by a strong emphasis on agricultural production, the results were far from what the founders had hoped. The idea in founding the colony had been to show that free labor could produce for self-sufficiency and export, and therefore feed the “legitimate trade” Footnote 19 that ultimately would have outcompeted slave-based production (Everill Reference Everill2013; Schwarz Reference Schwarz2017). A class of small landowners was to emerge, facilitated by free access to land for all. However, the soil of the colony turned out not to be as fertile as initially prospected and agricultural production remained stagnant until the annexation of more fertile areas in the hinterland (Birchall et al. Reference Birchall, Bleeker and Cusani Visconti1980; Caulker 1981; Colonial Office 1827b). It is, thus, likely that the ownership of land, even in large portions, may have not translated into high socioeconomic status, as was the case elsewhere.Footnote 20 Furthermore, the large number of very small landowners suggests that farmers had secondary occupations (so-called by-employment) that were as important for subsistence as farming was. This pattern would not be unique to Sierra Leone because by-employment was, and often remains, endemic to West Africa (Austin Reference Austin2005: 75; Bauer and Yamey Reference Bauer and Yamey1951, Reference Bauer and Yamey1954).

The low socioeconomic group accounted for 56.6 percent of the population employed in the colony. Low-skilled workers contributed only 6.2 percent to the total, whereas servants and other unskilled laborers accounted for 47.7 percent. Sawing was the predominant activity among low-skilled workers contributing to 3 percent of the total, a similar share to the employment in wood-processing industries. In 1839, timber export was by far the major source of revenue for Sierra Leone, accounting for more than 70 percent of the exports in value from the colony (Colonial Office 1842: folio 53). The source of the primary produce came from within the colony and nearby areas. In the colony, forests were cleared with the double aim of meeting the demands of timber and of cleared land for agriculture. Nonetheless, timber demand could not be solely met by colonial production. For this reason, a growing number of settlers engaged in timber trade with neighboring communities and traded timber in Freetown and York as middlemen for indigenous producers (Everill Reference Everill2013: 191). Unsurprisingly, major geographical differences existed due to the nature of the industry, which requires waterways for transportation and forests to be cleared. In this respect, two districts in the countryside took advantage of the prospects offered by the timber industry more than others, Hastings and First Mountain (see figure 1). However, a more modest involvement with timber production characterized the whole colony. Some authors argue that timber production assumed the role that was to be of agriculture, providing an alternative source of export for the colonial economy and for legitimate commerce at large (Fyfe Reference Fyfe1962: 125).

Domestic labor, in the form of servants, housekeepers, and charwomen amounted to 9.4 percent of the occupational titles recorded. Interestingly, men were involved in domestic occupations more than women, 58 and 42 percent, respectively, in contrast to Europe where women had a long-established predominance in domestic labor. If, on the one hand, this result could be partly driven by the general underrepresentation of female and child labor discussed in the preceding text, on the other hand, some scholarship argues that the pattern found in Sierra Leone was not isolated. Males were recorded to be employed as domestics more often than women in most tropical British colonies, Africa included (Lowrie Reference Lowrie2016: ch. 2). Robyn A. Pariser found that male servants, so-called houseboys, were employed by European households in Tanganyika up until the last decades of the twentieth century, making up the largest single occupational category in Dar-es-Salaam (Pariser Reference Pariser2015: 272). The historiography argues that the preference for male servitude may have had its roots in the oversupply of male unskilled labor in urban colonial areas accompanied by a prejudicial preference for men, considered to be more “appropriate” than women (Lowrie Reference Lowrie2016: 51–52). Sierra Leone, from its part, had an extremely unbalanced sex-ratio in 1831, with one women every three men (Colonial Office 1831). It is not unlikely that the large supply of male recaptives seeking jobs may have contributed to the pattern of employment. Regardless of gender, domestic servitude was more widespread in the urban area of Freetown than in the countryside, where the near totality of the elite group resided.

“Apprentices,” however, accounted for a substantial 20.1 percent of the total, and were more likely to reside in the countryside than in the capital. The group has been the subject of numerous studies and inquiries from the part of both contemporaries and scholars interested in the potential connection between apprenticeship and slavery Footnote 21 (Colonial Office 1842: folio 83; Macaulay Reference Macaulay1826: 100; Schwarz Reference Schwarz2020: 55–57). Regulations had been put in place by the Liberated African Department to allow recently emancipated young slaves to be indentured to “respectable” settlers’ households (Colonial Office 1842: folio 42). Young recaptives would be distributed throughout the colony for educational and apprenticeship purposes, ideally easing their process of settlement while reducing the pressure on the colonial finances (Schwarz Reference Schwarz2020: 55–56). By law, individuals 12 years of age or younger could be “apprenticed” upon the payment of a £1 fee to the Liberated African Department for a period from three to seven years depending on the recaptive’s age (Colonial Office 1842: folio 43). However, issues quickly arose as reports of kidnappings of young recaptives became widespread, many of them being apprenticed without the authorities’ consent (ibid.: folio 92). Although illegal, some individuals specialized in providing households with apprentices outside the official channels, the same individuals who happened to sell young recaptives as slaves outside the colony (Fyfe Reference Fyfe1962: 182; Schwarz Reference Schwarz2012: 195). Inquiries into the system of apprenticeship uncovered that, regardless of formality, it was very similar to slavery: poor treatment, no education, and long working hours. The limited information available suggests that apprentices were predominantly employed as domestic servants and unskilled labor, often in households that could not afford to pay for free labor (Colonial Office 1842: folios 91–94). The fact that households in the countryside tended to be less affluent than in the urban area may therefore explain why apprenticeship was more widespread there than in the capital.

Unqualified labor contributed to a further 16.7 percent. Individuals so recorded may have been employed in different sectors depending on demand, but the title could also mask a certain degree of unemployment. Although I found a few individuals recorded as farmworkers, it is not unlikely that unqualified laborers could be hired as farm labor when need arose (i.e., harvesting, land clearance) (ibid.: 93). Public works seem also to have absorbed some of this labor, with Allen M. Howard claiming that hired labor was commonly employed in construction by the colonial administration (Howard Reference Howard2020: 102)

Group Belonging and Occupational Categories

Table 5 displays information on group belonging arranged by occupational category for Sierra Leone, informing on the association between the two variables by relying on a Chi-squared test of association.Footnote 22

The test hints at a statistically significant association between group belonging and occupational categorization, arguing for the presence of occupational stratification. The table also records the instances in which the under- or overrepresentation of certain groups by occupational category is statistically significant, meaning when the rate at which a group is represented under- or overstate their group size.

Table 5 shows that Europeans accounted for a minor share of the occupied population in Sierra Leone, 0.5 percent or 68 persons, the totality of whom were male and residing in the capital. Unsurprisingly, despite the small group size, Europeans were overrepresented among the elite group, while only one individual was recorded in the unskilled group and none as farmers or low-skilled workers. The Europeans residing in Freetown formed the core of the colonial elite, occupied as high government officials, merchants, or doctors. A few Europeans appear in the low professional group, occupied as minor government officials, as well as government clerks (table 6). The 12 Europeans recorded in the skilled manual group were all mariners, although it is unclear whether they served in the navy or on a private vessel. The European in the unskilled group was James Walker, in service as a domestic servant in the house of the Chief Justice of the Vice-Admiralty Court at Sierra Leone Sir J. W. Jeffcott.

“Mulattoes” made up 0.3 percent of individuals occupied in Sierra Leone. Like Europeans, they also resided in Freetown and were overrepresented in high socioeconomic status occupations. Nevertheless, “mulattoes” did not hold high government posts, but were occupied as merchants, attorneys, shopkeepers, and administrative clerks. A few were also occupied in manual occupations as carpenters, shoemakers, and seamstresses. Although no “mulatto” was recorded as farmer, a few were employed as domestics (women for the most part) (table 5).

Colonial residents, the descendants of the original settlers, made up 9.5 percent of the population recorded as occupied in the colony. Similarly to Europeans and “mulattoes,” they too predominantly resided in Freetown, where they were often employed as low government official or clerks (table 6). Although they could be found across the whole socioeconomic structure of the colony, colonial residents were overrepresented in a number of occupational categories: from low professional, to clerks, to skilled manual workers (table 5).

Discharged soldiers and their wives contributed to 5.2 percent of the individuals recorded as occupied in the colony, the majority of whom resided in the countryside. Discharged soldiers were overrepresented as farmers, while underpresented in the lower socioeconomic category (table 5). Carpenters, tailors, sawyers, and traders were only a few of the occupations in which discharged soldiers were involved. The wives of discharged soldiers were consistently underrecorded, with only one-tenth of the total having an occupation associated with them, often as market clerks.

Liberated Africans made up the largest share of the population in Sierra Leone already by 1831. Thus, it is not surprisingly that 78.1 percent of the individuals recorded in the source as occupied were liberated Africans. The vast majority of the liberated Africans resided in the countryside, where numerous new settlements had been founded with the aim of absorbing an ever-increasing population (Scanlan Reference Scanlan2016). Liberated Africans accounted for the majority of the farming population in absolute values, although not in relative terms, likely a consequence of the limited occupational possibilities rural Sierra Leone offered. The group was significantly underrepresented within the elite category, whose activities occurred predominantly Freetown, although a few individuals were occupied as schoolmasters, teachers, and constables in the countryside. Liberated Africans made up the largest group in absolute numbers within skilled workers, the majority of whom were employed as carpenters, and within the low and unskilled group, where liberated Africans worked as sawyers, domestics, and unskilled labor.

The Kru, recorded 0.8 percent of the observations in the census, were occupied as domestic servants, and to a lesser extent as skilled workers, despite being renowned as knowledgeable seamen (Colonial Office 1827b: folios 16–19; Frost Reference Frost1999: 216–32). Only a minority was occupied in high socioeconomic status occupations as traders, constables, and watchmen. Overall, the group recorded the most unbalanced sex-ratio of all groups in the colony, 97 percent men and 3 percent women. This imbalance was a consequence of the motives for migration focused around bride wealth. Single Kru would, thus, move temporarily to Sierra Leone to work to acquire funds intended to pay for bride prices upon return (Frost Reference Frost1999: 32–38).

Native strangers accounted for a further 5.3 percent of the observation in the sample. Similarly to Kru, they too were voluntary migrants from nearby African regions. Native strangers, where the term “native” was intended as a synonym of indigenous and “stranger” to differentiate them from the original settlers, were significantly overrepresented in the elite category as a result of the large share of traders among them, accounting for a third of all traders in the colony. The native strangers’ group was the group most involved in commercial activities at any level, accounting for nearly a fourth of the individuals involved with commerce. Such a large commercial community provides evidence for the existence of a trade diaspora in Sierra Leone, intended as a community of individuals involved in trade “living among aliens in associated networks,” as defined by Philip D. Curtin (Reference Curtin1984: 2–3; see also Cohen Reference Cohen1971). Qualitative sources argue that these communities were formed by Muslim merchants and traders, Mandinka and Fula for the most part, who settled at Freetown to benefit from the active commercial environment (Fyfe Reference Fyfe1962: 149; Harrell-Bond et al. Reference Harrell-Bond, Howard and Skinner1978: 25–31). Nevertheless, not all native strangers belonged to the elite, as 38 percent was employed in unskilled occupations, as servants or unqualified labor.

Figure 2 graphically depicts the relationship between group belonging and socioeconomic status, divided into four major categories: elite, middle, farmer, and low.

European, native strangers, and “mulattoes” recorded the highest shares of individuals belonging to the elite group. Nearly half of the Europeans appear to have had high-status occupations, compared to 30 percent of native strangers and 12 percent of “mulattoes.” By contrast, only 7 percent of Kru were part of the elite, with the shares of discharged soldiers and liberated Africans being even lower, 1.9 and 1.7 percent, respectively. Europeans and “mulattoes” also recorded the largest shares of individuals belonging to the middle group, more than 50 percent of each, followed by colonial residents and native strangers. Kru, discharged soldiers, and liberated Africans all recorded much smaller shares, ranging between 10 and 20 percent. Farming employed nearly solely individuals residing in the countryside where land was readily available and of relatively better quality, mostly discharged soldiers and liberated Africans. Nevertheless, a few colonial residents and native strangers were also recorded as farmers, although they did not reside in the rural area of the colony, a sign that farming may also have been practiced on the outskirt of the capital despite worse soil quality there (Galli and Rönnbäck Reference Galli and Klas2021). The lower socioeconomic stratum was composed of Kru, native strangers, colonial residents, and liberated Africans. The vast majority of both Kru and native strangers were recorded as being occupied in low-status occupations, 73 and 72 percent, respectively. Colonial residents and liberated Africans also showed high shares of low-status occupations, respectively, 57 and 55 percent. “Mulattoes” and discharged soldiers too recorded a sizeable share of low-status workers, amounting to 34 and 31 percent, respectively.

Concluding Discussion

The results of the present study suggest that occupational stratification, intended as the existence of an association between institutional group categorization and socioeconomic status, played a role in the colony of Sierra Leone in 1831. However, the socioeconomic hierarchy that had come to develop in the colony did not depend on the degree of identification with the colonizers’ culture and norms, but rather on other elements associated with the specific context of the colony: geography and timing of settlement.

Unsurprisingly, Europeans and “mulattoes” recorded a high proportion of individuals in the highest socioeconomic strata of society, for example, elite and middle. However, black belonging to the native strangers’ and colonial residents’ groups did also appear in the same categories, owing to the heavy African involvement with trading and commercial ventures at large so central to the colony’s economy. Thus, occupational opportunities stemming from the colony’s favorable position appear to have been available to individuals of both European and African descent, if in possession of capital, networks, and capabilities. In spite of that, colonial residents and native strangers could be found all along the socioeconomic structure of the Sierra Leonean society. Other groups, liberated Africans, and discharged soldiers, were predominant in the lower strata of the socioeconomic distribution, including farming and low and unskilled occupations. It may not be casual that the geographic redistribution of these two groups throughout the peninsula allowed them to access arable land but also hindered their ability to access the most lucrative occupations available in the capital and limited their educational and networking opportunities. Theoretically, there could be negative selection in terms of ability and education if the authorities employed the most capable recaptives in the administration in the capital. However, it is more likely that the result was driven by the time of arrival in the colony. Discharged soldiers and liberated Africans landed later in the colony compared to most other groups, which may have impacted the geography of settlement and occupational opportunities. In a historical perspective, the findings of this study suggest that the Creole elite that would dominate the political panorama of Sierra Leone in later decades was not yet the elite in 1831. Furthermore, a comparatively large number of indigenous, or natives, belonged within high socioeconomic strata, despite their immigrant status and their resistance to assuming Western customs. However, later arrivals, including liberated Africans and discharged soldiers, occupied the lower strata of the society, suggesting that time of arrival may have also influenced socioeconomic opportunities.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/ssh.2021.47