On August 18, 2017, the academic community was surprised by an announcement made by Cambridge University Press (CUP), the publisher of The China Quarterly (CQ). At the request of Chinese State Administration of Press, Publication, Radio, Film and Television,Footnote 1 more than 300 research articles and reviews were censored; specifically, they were made inaccessible from the CUP website in China. Although this is not the first case of academic censorship in China, it is surely the most high-profile example to date. Initially, CUP justified the decision by stating that the entire website otherwise would be blocked. Amid the ensuing outcry, CUP quickly reversed its decision a few days later, making all of the articles available again. At the time of this writing, it is still not clear what further actions the Chinese authorities will take.Footnote 2

The incident is controversial not only because of the prestigious standing of CQ in its field but also because of the near-acquiescence of a major Western academic publisher. Regardless of the eventual outcome, this incident has significant implications. Rather than being a standalone occurrence, it was reported that the Journal of Asian Studies and the American Political Science Review, also published by CUP, received similar censorship requests on August 22 and September 20, respectively. According to CUP, all international publishers are facing the long-term challenge of censorship from China. Indeed, in October, Critical Asian Studies, published by Taylor and Francis, stated that two articles were reprinted in China with significant cuts based on political consideration without permission from the authors, journal, and publishers. In November, another publisher, Springer Nature, admitted that more than a thousand China-related articles had been removed from the official websites of the Journal of Chinese Political Science and International Politics. This article attempts to provide a much-needed analysis to make sense of academic censorship through the case of CQ.

It may be still too early to discuss what this incident means for the future of China studies and academic freedom inside China or elsewhere. Regardless, it is important to understand the rationale behind this move. We attempted to establish patterns in the wide range of authorship, publication dates, and topics in the targeted articles. Given the unprecedented nature of the request, one likely aim of the censoring agencies was to first test responses of the publisher and the international community; thus, they may have limited the number of articles on the list. This leads to the crucial question: What determines if an article is targeted for censorship?

The preliminary view of scholars (especially those affected) is that those who created the list probably did not actually assess the content of the articles (Ruwitch Reference Ruwitch2017). (This view is supported by the following analysis.) To provide a satisfactory answer to the question, it may not be sufficient to simply examine what is on the banned list; it is equally important to investigate what is not (at least in this round of censorship). This article compares the two sets of articles—banned and not banned—to tease out the logic behind this censoring action.

To provide a satisfactory answer to the question, it may not be sufficient to simply examine what is on the banned list; it is equally important to investigate what is not (at least in this round of censorship). This article compares the two sets of articles—banned and not banned—to tease out the logic behind this censoring action.

In the context of this research note, several caveats are in order. First, it should be emphasized that we do not intend to offer researchers and publishers the key to “bypassing” future potential censorship (or, worse, to exercise self-censorship) because academic freedom is the foundation of scholarly exchange. The following discussion of the articles, regardless of whether affected by this censorship, also is deliberately vague to avoid putting the authors at risk. Second, given the opaque nature of censorship and the lack of precedent, the discussion inevitably involves a certain degree of subjectivity, speculation, and interpretation. We keep these to a minimum and base our observations on data as much as possible. Third, our analysis is preliminarily based on the assumption that the censor was not overly sophisticated (e.g., reading the publications or performing any computer-assisted content analysis). Although this could be justified by our observations, future studies will determine whether these approaches can yield more insightful results.

ACADEMIC CENSORSHIP IN CHINA: FROM INTERNAL TO EXTERNAL

Censorship in the context of China refers to the governing strategy of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) to exercise control on the content and flow of information in Chinese society (Qiang Reference Qiang2011). Scholars have long recognized that the CCP has firm control over the traditional mass media (Lorentzen Reference Lorentzen2013) from publications to broadcasts, and over online social media (Yang Reference Yang2016) from social-networking services to messaging, ensuring that all media content toes the party line. However, the topic of academic censorship is seldom explored, perhaps due to its relatively recent development. This article provides a first look into China’s academic-censorship strategy.

Academic publishers in China are mostly state-owned/controlled and are the initial screeners of “sensitive” political information and discourses. Virtually all of the top universities in China are subordinate to the Ministry of Education, which controls funding resources and personnel issues. All of these measures facilitate political censorship within Chinese academia. Since 2012, China has further tightened political control over educational institutions with foreign connections and officials have called on universities to stop using imported textbooks with “Western values.” President Xi Jinping has called on all Chinese universities to be “strongholds of the party’s leadership” with “ideological work.” In June 2017, the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection (CCDI) released a report and criticized party committees at each university for performing badly in the implementation of ideological systems. After that, CCDI accused 14 top universities of ideological infractions (Feng Reference Feng2017).

Initially limited to the mainland, this practice appears to be extending to other regions. In March 2017, it was reported that Taiwanese universities had been invited to make an agreement with the Chinese government that they would not discuss sensitive issues (e.g., unification/independence or the idea of “One China, One Taiwan”) in class. Due to huge economic benefits brought by fee-paying mainland students, more than 80 of 157 universities reportedly accepted the demands, thereby compromising their academic independence (Smith Reference Smith2017). Academic censorship also extends to the special administrative region of Hong Kong. During a meeting of Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference in March 2014, the Hong Kong University Public Opinion Programme (HKUPOP)—an opinion research center that conducts regular polls on public views about a range of political and social matters—was criticized by the Chinese authorities and pro-China figures, who argued that its research findings were “preposterous” and that it is “intent on messing up Hong Kong.” Robert Chung, a scholar and the director of the HKUPOP, was criticized for releasing polls at critical moments with findings unfavorable to the Chinese and local administrations and for “being manipulated” by foreign interests (Kwong and Yu Reference Kwong, Yu, Zheng and Yew2013).

Chinese academic censorship also threatens the international community. Similar to the CQ case, in March 2017, the Chinese government shut down the US-based LexisNexis service in mainland China because it refused to pull selected content (Lau and Mai Reference Lau and Mai2017). Currently, users in mainland China must access academic journals on LexisNexis through a virtual private network, which also was recently the subject of a crackdown.

Summarizing the previous discussion, it can be seen that the scope of censorship has been gradually expanding in two dimensions. First, it is extending from the more traditional forms of media to social media and other electronic platforms. Second, the Chinese censorship of academic material has expanded from the higher-education sector in the mainland to the surrounding areas. The ongoing case of CUP and CQ reflects an escalation in both dimensions because it represents censorship of the electronic platform of an international publisher.

Summarizing the previous discussion, it can be seen that the scope of censorship has been gradually expanding in two dimensions. First, it is extending from the more traditional forms of media to social media and other electronic platforms. Second, the Chinese censorship of academic material has expanded from the higher-education sector in the mainland to the surrounding areas.

CENSORED ARTICLES: AUTHORSHIP, COVERAGE, IMPACT, AND THEMES

After duplicate entries were removed from the list provided by CUP, 304 unique articles were affected by the censorship request in 2017. Figure 1 summarizes the types of censored articles. More than half (167) were book reviews (of one or more books), 38% (116) were typical research articles or other research-related work, and 7% (21) were other publications (e.g., reports of recent developments, mainly from earlier years, or short commentaries). Because the reviewed books might be the actual targets of censorship, the book reviews were not analyzed in detail in this article.

Figure 1 Censored Articles by Article Types

Source: Authors’ analysis based on information provided by the journal. The Article category includes all pieces with substantive research elements. The Other category includes reports on “recent developments,” comments, methodological notes, etc.

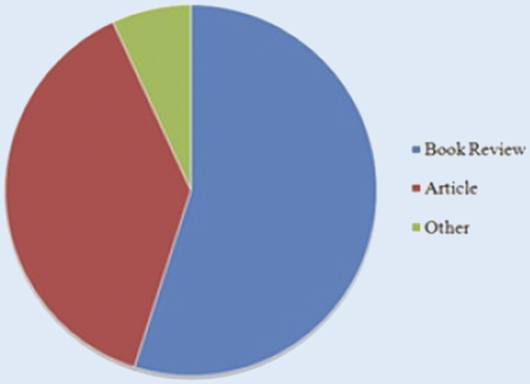

Next, it was interesting to examine profiles of the authors of articles that were deemed “inappropriate.” A breakdown of authorship by institutional affiliation is shown in figure 2 for all articles except the book reviews. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the articles were written mostly by US and UK scholars, with about 90% affiliated with a Western institution. However, several scholars affiliated with Chinese institutions also were affected. Three Chinese scholars (i.e., six research articles after 2010) are on the list and two book reviews are by foreign experts currently working in China (i.e., in a university and a consulate). In addition, China-affiliated scholars are virtually non-existent in the articles on prominent themes. The affiliations of scholars do not seem to have had a part in the censor’s decisions; rather, their affiliations determined the areas in which they work, for obvious reasons.

Figure 2 Censored Articles by Authors’ Affiliation

Source: Authors’ analysis based on the contributors section in the journal and other sources (if not provided in the journal). The affiliations of the authors are included for coauthored pieces. The affiliations of the authors of a small number of earlier articles could not be found. Greater China included Taiwan and Hong Kong.

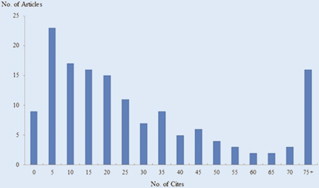

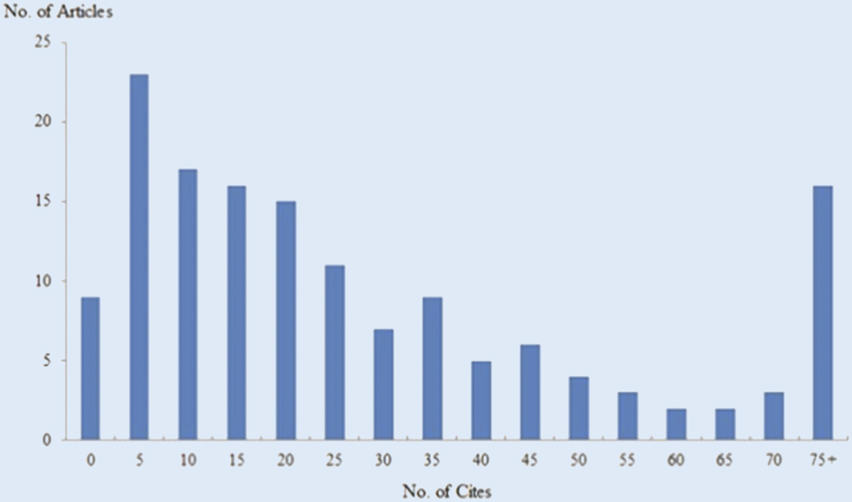

Censors also do not seem to be interested in an article’s impact.Footnote 3 The number of citations is listed in figure 3. As shown, although there are several high-impact publications, many of the articles had not been widely cited (at the time of censorship). The list includes a number of articles published in 2016, which may explain why they have not yet been cited in other publications.

Figure 3 Censored Articles by Number of Citations

Source: Authors’ analysis based on figures from Google Scholar as of August 19, 2017. The sample includes only research articles.

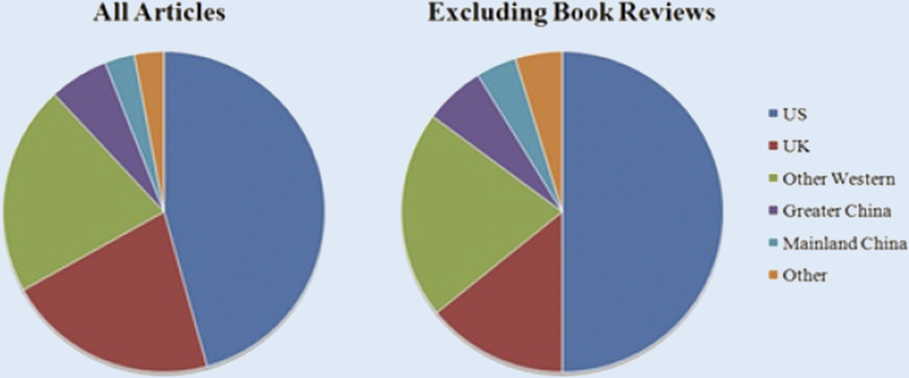

A text analysis of all of the articles reveals several themes, including the Cultural Revolution, Falun Gong, Mao Zedong, Tibet, Tiananmen, and Taiwan. A closer inspection of the list suggests that Xinjiang (Sinkiang) and Hong Kong also are potential targets. Finally, several articles specifically focus on three individuals: namely, astrophysicist and dissident Fang Lizhi; Nobel literature laureate Gao Xingjian; and author and former Minister of Culture Wang Meng. A rough breakdown of the articles by theme is shown in figure 4. More than 40% of the articles relate to the Cultural Revolution and Mao Zedong (which are difficult to separate in many cases). This is followed by Tiananmen (around 15%), and Tibet/Taiwan (depending on whether only research articles were considered).

Figure 4 Censored Articles by Theme

Source: Authors’ analysis. Articles were classified according to the main theme (usually in the title). In some cases, articles had two themes (each theme was then counted as 0.5 article). Other themes include political succession, individual leaders, etc.

CENSORED AND “SPARED” ARTICLES: HOW DO THEY DIFFER?

Based on the previously identified themes, we compiled a list of all research articles published in CQ since its inception in 1960 that broadly relate to these themes. By comparing the banned and “spared” articles under each theme, we can—to a certain extent—reverse-engineer the logic of the censors. We started with more established and clear-cut patterns before moving on to discuss more uncertain—and, therefore, speculative—observations.

First, there are some blanket bans, including Falun Gong. All five of the articles containing this term in the title were included on the list of censored articles. This blanket ban allowed us to see that the censors did not read the actual text. For example, Falun Gong appears in the text of some uncensored articles after 2000. This point was confirmed by the analysis of the term “Tiananmen,” which was found in the text of many uncensored articles (as long as it does not trigger other censorship conditions). The ban also seems to be absolute for articles on Fang Lizhi (i.e., two articles and a memorial note); Gao Xingjian (i.e., a conversational note/article and two reviews); and Wang Meng (i.e., a research article). However, this cannot be confirmed because none of the surviving research is related to these themes.

Discussions of Tiananmen are virtually completely banned, with a few exceptions. The biggest target of this censorship action, at least 43 pieces (i.e., 18 articles) on the censored list relate to the 1989 incident. The appearance of the term anywhere in the title or abstract resulted in censorship. The importance of Tiananmen to the actual theme of the article does not seem to have been considered.Footnote 4 For example, in a series of articles on Deng Xiaoping, one article, “Deng Xiaoping: The Statesman,” is on the list, probably because it mentions Tiananmen in the abstract, whereas all other articles in the series (e.g., “Deng Xiaoping: The Economist,” “The Politician,” and so on) do not. However, closer investigation also showed that the censors did not apply the filter blindly. A 2007 article about political parades that mentions the “celebrations held in Tiananmen Square in the 1950s” was not affected. Conversely, some articles about Tiananmen appear to have escaped the censors’ notice because their abstracts do not contain the term. For example, an article on protest and repression that discusses the “democracy movement of 1989” was not included, as well as another one referring to it as the “June Fourth Incident” (both without using the term “Tiananmen”).

Tibet is another major topic given heavy-handed treatment—that is, almost every mention of Tibet was censored. (This also may have led to the ban of several articles on Buddhism, but this cannot be confirmed.) Even articles with apparently “favorable” information—such as those about the subsidies and investments made by the central government to the region—were included on the banned list, perhaps because of references to Tibetan protests in 2008. We found at least four notable exceptions to the ban on articles about Tibet, which further reinforced our argument that the keyword-filtering system is subject to human adjustments. Two uncensored articles discuss the social-demographical dimensions of Tibet, the third focuses on the state of Tibetan studies, and the fourth analyzes Chinese military maneuvers in Tibet before the formation of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) (i.e., the Kuomintang under Chiang). On a related note, recent border troubles with India might have been the reason for banning a 1960s article on Aksai Chin (i.e., bordering India, Tibet, and Xinjiang). Although that article also referred to Tibet, this alone should not be sufficient to lead to its censorship (as shown by the survival of a 2014 study focusing on an association on the “Sino-Tibetan border”). Similarly, articles on the disputed Diaoyu/Senkaku Islands were not banned. The treatment of Xinjiang (the censors do not miss the term “Sinkiang”) is similar. All “political” articles referring to social unrest, challenge, or Uyghur identity or nationality appeared on the censorship list. However, it should be emphasized that this standard is less clear-cut. Several seemingly neutral articles might be censored because they discuss the potentially sensitive minority status of the Muslim population, yet there are unaffected articles with similar phrases.

The picture for Hong Kong is quite clear as a result of the relatively small number of articles on the list (i.e., six research articles). Two were on the banned list arguably because of references to Taiwan and the Cultural Revolution and another for the use of the term “Tiananmen” in the abstract. Two of the remaining articles were recent publications about the social and political situation of Hong Kong and, notably, made explicit reference to the Umbrella Movement of 2014, which is considered politically sensitive. (A recent article on the politics of China–Hong Kong integration that does not include such a reference was not affected.) The sixth article, published in 2000 about the post-handover political structure of Hong Kong, is a curious inclusion. Although it is potentially problematic due to its discussion of the explicit actions of Chinese leaders to forge the governing alliance of Hong Kong, a more recent publication on the same topic—with updated arguments that attribute an equally strong role to China—was not on the list. With the timing of the publication being the only identifiable difference, we only can speculate that perhaps the Chinese authorities do not want the work about the area to be linked—causally or temporally—to the reunification (in 1997) and thus its success.Footnote 5

Turning to the topic of Taiwan, some articles were clear targets for writing about independence, potential changes to the “One China” policy, creation of a new identity, Chen Shui-bian, and Lee Teng-hui. However, given the sheer number of articles on Taiwan published by CQ over the years, each term—with the exceptions of Chen and Lee—was found in more articles on the uncensored list than on the censored list. It is uncertain whether the censors neglected the term “Formosa,” used mainly in the 1960s, or simply considered that period less important. References such as the formation of “an independent Formosan state, without ties to mainland China” were left unscathed by the censors. More articles on the censored list came from recent decades; however, even if we focus only on more recent publications, the use of the terms “independence” and “independent” did not result in an automatic ban. For example, one uncensored article argued that Taiwan enjoys “de facto…independence”; another noted Taiwan’s “quasi-independent existence.” They may be considered acceptable articles because they point to the strengthening of the status quo and the role played by America in maintaining the balance, respectively. Economic identity and cultural identity are acceptable topics, whereas the creation of a new Taiwanese identity is not—especially when contrasted with the PRC’s efforts in the opposite direction.

The last group of censored articles relate to Mao Zedong and the Cultural Revolution, which are discussed together given their intertwined nature. There are 130 pieces (i.e., 51 research articles) on the censored list loosely classified under these categories. A considerable number of articles on these topics were on the uncensored list. In general, it appears that articles that discuss the Cultural Revolution as part of Mao’s attack on the party, its violence, or its relationship with ethnic minorities were on the censored list.Footnote 6

Another set of comparisons also is interesting. Although articles about the Cultural Revolution and the military, the Chinese political system, and the State Council were on the banned list, two similar articles on the Foreign Ministry and regional institutions during the Cultural Revolution were “spared.” Instead of any difference in study design, we found that abstracts of the surviving articles were more “neutral.” For example, one article phrased its argument as a research question (i.e., “whether…”), whereas the other merely wrote about “unexpected findings.” All of the articles in a recent CQ special issue on various aspects of the Cultural Revolution were included on the list, with the exception of “Cultural Revolution as Method.” In comparison to the Cultural Revolution, the Great Leap Forward was not regarded as a problem in this round of censorship despite its presence in a few articles on the censored list.Footnote 7

Finally, if we accept the argument that it is discussions of the Cultural Revolution that explain censorship, then the case of Mao Zedong can be unambiguously resolved. All of the banned research articles related to Mao were on other potentially sensitive topics (e.g., the Cultural Revolution and ethnic minorities). There also were many book reviews that are beyond the scope of this research. Therefore, although “Mao” is a preliminary candidate for one of the keywords used in the censorship, we can cautiously confirm that Mao was not the target here. This is perhaps a pragmatic course of action, given the omnipresence of Mao in Chinese publications for decades.

CONCLUDING REMARKS

Existing literature has established a good understanding of the situation of censorship in China. However, with the rise and expansion of the Chinese academic field, implications of academic censorship have yet to be fully explored. Currently, the authorities attempt to extend their censorship strategies in breadth (i.e., beyond the mainland) and scope (i.e., to new platforms as well as academia). On the one hand, Chinese authorities threaten universities elsewhere to censor its curriculum by controlling the flow of students, such as in the case of Taiwan. On the other hand, they force international publishers to censor its content by controlling access within China. Theoretically, this article offers an original perspective to the extension of academic censorship beyond an authoritarian state. Empirically, it provides an analysis on what China wants to censor through the case of CQ.

Although this analysis provides important observations on the censoring actions, it also raises questions for the academic community. First, book reviews were not covered in our analysis because it is likely that the books were the target rather than the reviews. An investigation of the censored books may yield additional insights. Second, to reiterate, we do not want to find ways to bypass the censors or to put more articles at risk. Rather, we want to shed light on the censors’ strategies and prepare the academic community for similar actions, which are inevitable. Alternative avenues of knowledge transfer should be made available, regardless of whether access to selected articles or an entire journal is blocked in China. We also should be vigilant for any unannounced censorship to which other publishers might have agreed (thus highlighting the utility of the current exercise). Finally, it is high time that scholars working on China and publishers in the field determine ways to overcome censorship. The initial uproar was caused by the unilateral decision made by CUP to accede to demands of the Chinese authorities. It takes the collective strength of scholars and publishers to uphold academic quality and freedom of knowledge. Clearly, these outstanding questions are beyond the scope of this article.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Chor-hin Chan and Adrian Lam for their research assistance.