Introduction

Cross-cultural interaction remains one of the core themes in studies of introduced subject matter in rock-art assemblages. In Indigenous rock-art contexts, introduced subject matter is characterized as distinctive motifs depicting objects, animals and anthropomorphs with specific accoutrements (e.g. top hats, smoking a pipe) that were introduced into Indigenous society upon contact with the ‘other’. Studies of these distinctive motifs have generated significant findings into topics such as change and continuity, performance and memory, antiquity of cross-cultural interaction, involvement in specific events, motifs as symbols of power and resistance, and reflections of Indigenous involvement with new technologies and industries (e.g. Clarke & Frederick Reference Clarke, Frederick and Lilley2006; Frederick Reference Frederick1999; May et al. Reference May, Taçon, Wesley and Pearson2013; McNiven & Russell Reference McNiven, Russell, David and Wilson2002; Taçon et al. Reference Taçon, May, Fallon, Travers, Wesley and Lamilami2010). Yet within this research, the role of economic frameworks guiding or shaping the production of an introduced subject matter assemblage has oftentimes been overlooked. As such, this paper aims to go beyond simply identifying motifs thought to represent introduced subject matter and the cross-cultural framework(s) guiding their interpretation to direct attention instead to the complex network of relations that potentially underpin the production of such motifs. To do this, we focus on one of the key economies that was critical to European expansion across the Australian continent during the early phases of colonialism—the pastoral economy.

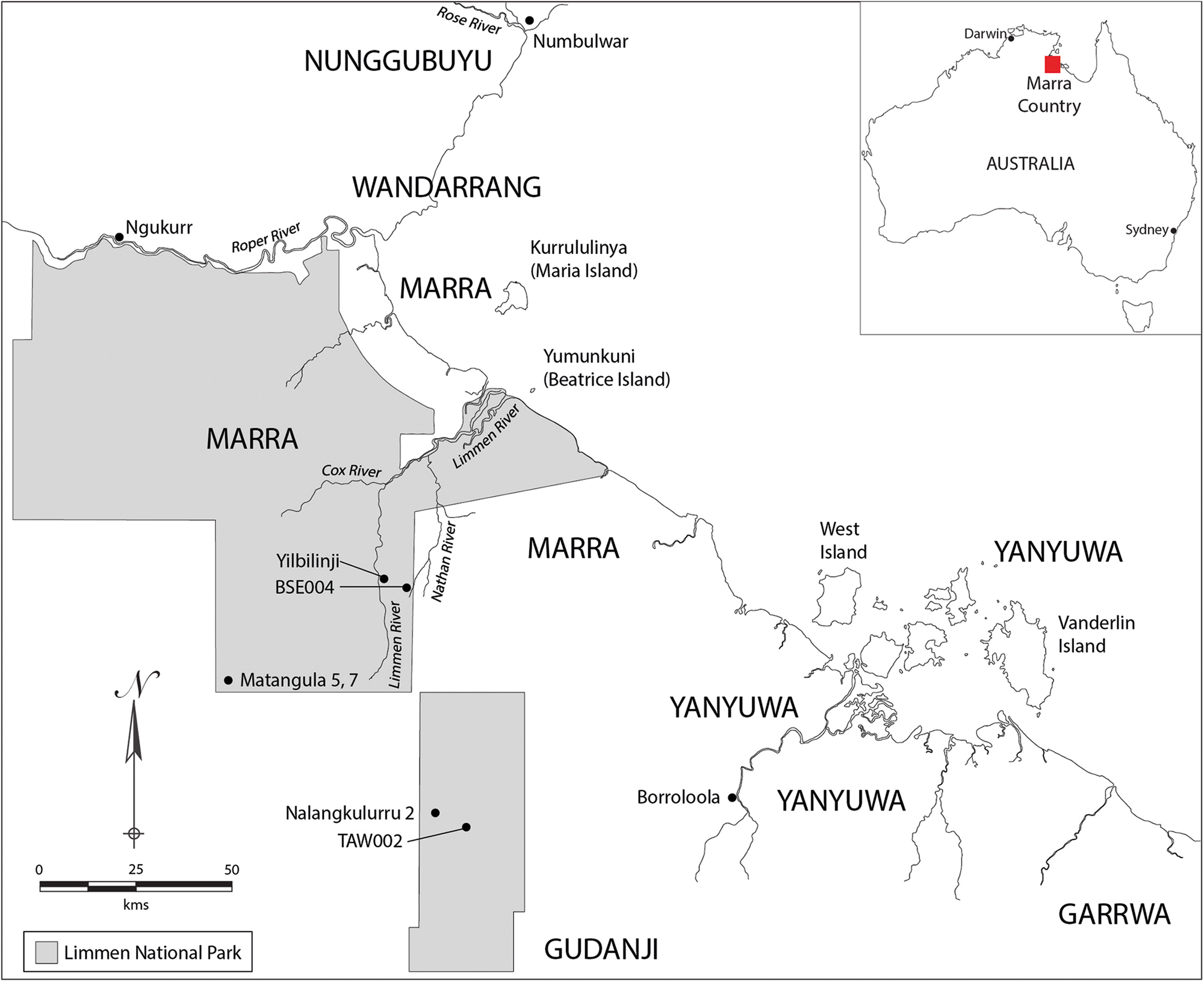

To explore this idea, we use a case study involving an assemblage of introduced subject matter recently recorded from Marra Country in northern Australia's southwest Gulf of Carpentaria region (Fig. 1). The introduced subject matter assemblage recorded between 2015 and 2018 is dominated by horses, cattle, firearms and other objects that appear consistent with a pastoral economy. Our approach to investigating how this assemblage is made meaningful is based on Altman's (Reference Altman2006, 36) hybrid economy framework, an approach that attempts to get to the nature of the forces that shape people's engagement with country as a result of European colonization and subsequently how it is being marked (e.g. Wesley Reference Wesley2013; Wesley et al. Reference Wesley, McKinnon and Raupp2012; see also May et al. Reference May, Wesley, Goldhahn, Litster and Manera2017). Thus, this paper argues that by embedding these motifs into a hybrid economy context, namely pastoralism, a more nuanced approach to cross-cultural interaction studies can emerge, adding another layer to the story of Aboriginal place-marking in colonial contexts.

Figure 1. Marra Country and Limmen National Park.

The southwest Gulf Country and the ‘outsiders’

Prior to the arrival of ‘outsiders’, the southwest Gulf country was home to six language groups—Marra, Yanyuwa, Garrwa, Gudanji, Binbingka and Wilangarra. However, frontier violence led to the decline/erasure of the Binbingka and Wilangarra by the early 1800s (Roberts Reference Roberts2005). The Marra, along with the neighbouring Yanyuwa, identify themselves as Saltwater People, that is, people whose lifeworld is embedded in sea country (e.g. Bradley with Yanyuwa Families Reference Bradley2010; Sharp Reference Sharp2002). Marra Country stretches from the southern bank of the Roper River in a southeasterly direction to the northern regions of Rosie Creek, and includes the sea, islands and coastal areas of the Limmen Bight. Marra Country also extends inland up to 60 km from the coast where there are broad plains interspersed with low, rocky sandstone ranges. Today, much of Marra Country, including the locations of the rock art discussed in this paper, forms part of Limmen National Park.

Early phase: 1640s–1870

The first outsiders to visit the region were Dutch navigators in 1644. They sailed through Marra sea country, naming it the Limmen Bight (after one of their vessels, the Limmen); however, they did not mention seeing or interacting with any Marra. From the late 1600s/early 1700s, Macassan fishermen from the port of Makassar on the island of Sulawesi in Indonesia began sailing seasonally into the southwest Gulf country to harvest trepang (Holothuria scabra) (e.g. Clark & May Reference Clark and May2013; Macknight Reference Macknight1976). Bradley (Reference Bradley1997; 2018) notes there was considerable interaction between Macassans and the Yanyuwa and Marra who worked for Macassans in the trepang-rich waters of Yanyuwa Country (the Sir Edward Pellew islands). In return for their work, Yanyuwa and Marra received from Macassans dugout canoes, cloth, steel, tobacco and iron knives, while Yanyuwa and Marra composed songs about Macassans that are still remembered today (e.g. Bradley Reference Bradley1988; Reference Bradley2018). While linguistic evidence only shows 11–12 words of Macassan origin in Marra language (Evans Reference Evans1992; see also Dickson Reference Dickson2015), Marra exposure to Macassan material culture was a regular occurrence from the late 1600s/early 1700s.

In 1802, Matthew Flinders (Reference Flinders1814, II, 179) sailed through Marra Country, observing evidence of people on Maria Island (fires, footprints) in the Limmen Bight but not landing on the mainland or interacting with any people. In 1845, the explorer Ludwig Leichhardt stopped at several inland locations on Marra Country on his travels to Port Essington near Darwin. On several occasions he made reference to ‘natives’ and evidence for their occupation of the landscape (Leichhardt, October 6, 1845: https://adb.anu.edu.au/entity/8843). In 1865, HMS Beatrice's commander Frederick Howard visited the Limmen Bight area, climbed Wunubarryi (Mount Young) and recorded seeing Aboriginal people burning the landscape and ‘native tracks’. At Maria Island he documented canoes and more walking tracks and, although not seeing many people during his visits to the mainland and island, he felt that ‘we were generally watched’ (1865: cited in Olney Reference Olney2002, 64). Another man in Howard's group named Webling also noted seeing canoes, remains of a camp and ‘native fires burning inland’ (Webling, 1 July 1865). Upon sailing up the Limmen River they saw more fires, a canoe paddle, shell midden, skeletal remains that they subsequently stole and an Aboriginal man in a canoe who paddled by them, but ‘he took no notice’ of their cooees (calls) (Webling, 4–6 July 1865; Webling Reference Webling1995, 48). Other examples of interaction or observations of Marra come from members of Cadell's 1867 expedition in the Limmen Bight, commenting on people in canoes with turtles, and a freshwater well; personnel building the Overland Telegraph Line (1870–72) noting camps and oyster-shell middens at Maria Island; and Alfred Giles (Reference Giles1926) seeing canoes and shell middens, also at Maria Island (for further details, see Bradley Reference Bradley2018).

Middle phase: 1870–1900

Pastoral expansion and violence characterized interactions between Marra and outsiders from the early 1870s to 1900. Pastoralists overlanding cattle from Queensland into the Top End and Kimberley created the ‘Gulf Coast Track’ that crossed the traditional lands of all the region's language groups. Gold prospectors on their way to goldfields in Pine Creek and the Kimberley and pastoralist investors keen to secure pastoral leases across the southwest Gulf country meant a further influx of Europeans (Fig. 2). It was during this time that Marra and neighbouring language groups became exposed to Europeans in much greater numbers along with extraordinary amounts of cattle and horses.

Figure 2. The approximate route of the ‘Gulf Coast Track’. (Map adapted from Roberts Reference Roberts2005.)

Roberts (Reference Roberts2005; Reference Roberts2009) provides the most detailed record of the atrocities pastoralists committed during this time, namely the brutal massacres of Marra and other language groups which ultimately led to the demise of the Binbingka and Wilangarra. This era is referred to by Aboriginal people in the area as ‘Wild Times’. Reports of Aboriginal people killing cattle and horses and carrying out stealth attacks on Europeans reveal their heavy presence in the landscape, intense resistance to the newcomers and their increasing exposure to, and familiarity with, introduced animals (cattle, horses, sheep) and European objects such as guns, pottery, glass, wagons and smoking pipes. With around 150,000–200,000 head of cattle and 10,000 horses travelling on the Gulf Coast Track in the 1870s and ’80s (Roberts Reference Roberts2005, 67; Webber Reference Webber, Leather and Webber2015, 27), the Marra landscape and environment was dramatically transformed, with waterholes fouled and fences constructed.

By the late 1880s/early 1890s, pastoral stations were established across the southwest Gulf country. In 1884, John Costello established his Valley of Springs station near the Limmen River, occupying the majority of Marra Country, stretching from the McArthur River near Borroloola westwards to the Roper River. Dickson (Reference Dickson2015, 56) uses data from Costello's son's (Reference Costello1930) memoir to suggest that ‘at least a hundred—perhaps several hundred—people were living on Marra Country when Valley of Springs was established’. Archival narratives reveal details about the Marra's mobility and economic strategies during the life of the station: in the wet season, Marra hunters would lead cattle to wet, boggy, muddy grounds where the animals became stuck and Europeans were unable to free them, thus leading to easy hunting; and in the dry season, hunters would be stealthy and spear animals close to the rugged ranges where they could butcher and collect the meat before disappearing back into the ranges (Costello Reference Costello1930, 131; Roberts Reference Roberts2005, 166). By 1892–3, Valley of Springs was abandoned due to the Marra's widespread cattle-spearing, along with other factors (bushfire, crocodiles, tick fever) (Roberts Reference Roberts2005, 167). ‘Dick’ was the only Marra man recorded to have been working for Costello. Costello described Dick as living on the station, learning some English, how to ride a horse, and becoming ‘serviceable in stock mustering’ (Costello Reference Costello1930, 135). During a survey of the property, Dick eventually abandoned Costello after going to find water among his ‘own people’, presumably Marra (Costello Reference Costello1930, 148).

Late phase: 1900 onwards

With pastoral stations in the Top End stocked with cattle, use of the Gulf Coast Track declined rapidly from the 1890s and with it, much of the violence directed towards Marra and other language groups along the track. In 1901–02, anthropologists Spencer and Gillen visited Borroloola, where they observed Marra people living in one of the town's two Aboriginal camps (Reference Spencer and Gillen1914, 9); in 1908, the Roper River Mission was established at the mouth of the Roper River with many Marra also residing there; and from as early as the 1920s/30s, living and working on pastoral stations (e.g. Bern et al. Reference Bern, McLaughlin and Larbalestier1980, 16; Bradley Reference Bradley2018; Dickson Reference Dickson2015). Despite appearing to be increasingly sedentary by basing themselves at Roper River Mission, Borroloola, and pastoral stations, many Marra continued living on country until the late 1960s (see below) (Dickson Reference Dickson2015). Those with a ‘home base’ at Borroloola, Roper River Mission and pastoral stations also regularly left to return to their country for varying lengths of time (including seasonally for pastoral workers) and to take part in traditional activities including ceremonies and initiations (Bern et al. Reference Bern, McLaughlin and Larbalestier1980, 17–18; Dickson Reference Dickson2015, 67–9). Further details of Marra mobility and involvement with the pastoral industry are discussed below.

From the 1870s onwards, interaction dramatically intensified between the Marra and Europeans, leading to a familiarity with introduced animals, objects and structures (homesteads). However, it is the Marra's extensive involvement with the pastoral industry and economy (e.g. seasonal stockmen, domestic workers) that plays a critical role in evaluating the nature of the detailed depictions of introduced subject matter in Marra Country. So great was the Aboriginal involvement in the pastoral industry in northern Australia that Bleakley (Reference Bleakley1929, 5, 7) wrote: ‘[o]ne fact … is universally admitted, that the pastoral industry in the Territories is absolutely dependent upon the blacks for the labour, domestic and field necessary to successfully carry on’.

Hybrid economies and culture contact

Altman's (Reference Altman, Taylor, Ward, Henderson, Davis and Wallis2005; Reference Altman2006) hybrid economy framework was designed to increase attention to the often overlooked contributions that Indigenous people make to developing sustainable economies. To do this, he developed his framework as an ‘analytical construct for the assessment of the particularities of any one situation and the linkages between the market, the state and the customary components of the economy’ (Altman Reference Altman, Taylor, Ward, Henderson, Davis and Wallis2005, 36). This is essentially the interaction of contemporary Aboriginal communities with state and market economies (see also Keen Reference Keen2010). Three interrelated sectors are identified as integral to a hybrid economy:

• Market (e.g. retail, arts industry, wildlife harvesting, mining, tourism, pastoralism)

• State (service provider, law enforcement)

• Customary Indigenous based on cultural continuity (e.g. hunting, gathering, fishing, habitat management, burning)

It is the linkages and interdependencies between these three sectors that he argues are essential to understanding challenges for developing sustainable hybrid economies in rural and remote Indigenous communities (for a recent critique, see e.g. Curchin Reference Curchin2013).

While Altman's framework was designed to deal with contemporary economic development problems, archaeologists have used it to explore linkages between market, state and Indigenous customary economies in historical or cultural contact settings. Market economies included interaction with Macassan trepangers and European economies such as pastoralism, mining (e.g. gold, opals), buffalo hunting, and pearling. State forces included the state (South Australia) and Commonwealth government that resulted in control and ownership of Indigenous lands, government settlements and the building of the Overland Telegraph Line, while Indigenous customary forces, such as subsistence and other non-monetary, non-market, subsistence and other informal economies, continued during this time.

In using Altman's model, we acknowledge the issues surrounding use of the term ‘hybrid’ in characterizing the complexity of transformations that occur as a result of Indigenous–colonial encounters. ‘Hybrid’ and ‘hybridity’ have often been associated with issues around race and ethnicity and imply a degree of stasis in these relationships (e.g. Kapchan & Strong Reference Kapchan and Strong1999; see also Robinson Reference Robinson2013). However, our use of ‘hybrid’ reflects the nomenclature used by Altman and refers to the intertwined economic systems that were operating in the southwest Gulf of Carpentaria at the time, rather than suggesting Indigenous traditions became hybridized as a result of this interaction.

Key examples of a hybrid economy approach come from western Arnhem Land. For example, Wesley and Litster (Reference Wesley and Litster2015) describe how glass beads recovered in excavations were introduced by Macassans sometime after 1800 ad. Aboriginal people bestowed them with traditional significance—they became highly sought-after exchange items, used to negotiate access for Macassans to trepang beds and in exchange for labour in different forms of colonial economies (Wesley & Litster Reference Wesley and Litster2015, 12). A spinoff from this exchange network was that they were also introduced into existing rock-art traditions as a distinctive design element on anthropomorphs (Wesley & Litster Reference Wesley and Litster2015, 12). Wesley (Reference Wesley2013) also describes how firearm (rifle) motifs reflected changes in Aboriginal society, especially Aboriginal engagement with the buffalo-hunting industry in western Arnhem Land (1870s–1920). During this time, Aboriginal people became involved in a ‘well-developed hybrid economy between white Australian shooters and Indigenous families’ (Wesley Reference Wesley2013, 245) whereby Aboriginal people were in possession of different forms of rifles and built an intimate and detailed knowledge of them that resulted in a significant number of firearms used in this economy being depicted in rock art. However, changes by the state from the 1920s onwards that prohibited Aboriginal people from owning firearms meant their involvement in the buffalo-hunting economy declined altogether, thus explaining the lack of post-1920s firearm motifs in Australia.

Using these studies as a platform, we explore how the hybrid economy model can be used to understand how the Marra interacted with the outside market and state forces while continuing to negotiate their own customary cultural economies and traditions, namely the production of introduced subject matter into extant graphic (rock art) systems.

Introduced subject matter in Marra Country rock art

Prior to 2017, there have been very few recordings of motifs depicting introduced subject matter in the southwest Gulf country. In Yanyuwa Country, senior Yanyuwa woman Dinah Norman recalled seeing a painting of a yirrikirri [donkey] at a rock-shelter on South West Island in the 1940s, but this has since disappeared (see Brady et al. Reference Brady, Bradley and Kearney2016). In 1999–2001, Robin Sim (Reference Sim2002) identified four motifs from Yanyuwa Country she thought depicted introduced subject matter (European and Macassan): three motifs (‘metal shears’, a ‘red ochre boat’, a possible ‘prau’) have not been verified by us, and a fourth motif (another possible ‘prau’) was interpreted by senior Yanyuwa men to John Bradley in 1984 as bark canoes. In Garrwa Country, an elaborate painting of a paddle-steamer, the Young Australia that sank in the Roper River in 1872, is located at Jininyina (Spring Creek), while in Marra Country, introduced subject matter was first encountered and recorded in 2015–16 as part of the first cultural heritage surveys at Limmen National Park, with key motifs photographed including all but one introduced subject matter motif.

Rock-art research in Marra Country began in 2017 as part of a collaborative project involving the authors, Marra Families and the Parks & Wildlife Commission of the Northern Territory (PWCNT). Although still in its infancy, research thus far has revealed, among other things, the world's largest-known assemblage of miniature and small-scale stencil motifs, an increase in the geographic distribution of beeswax motifs and insights into Indigenous self-determined conceptions of rock art in relation to kinship, ontology and epistemology (e.g., Brady et al. Reference Brady, Bradley and Wesley2019; Reference Brady, Bradley, Kearney and Wesley2020; Kearney et al. Reference Kearney, Bradley and Brady2021). To date, 56 sites and over 3000 motifs from across Marra Country have been recorded.

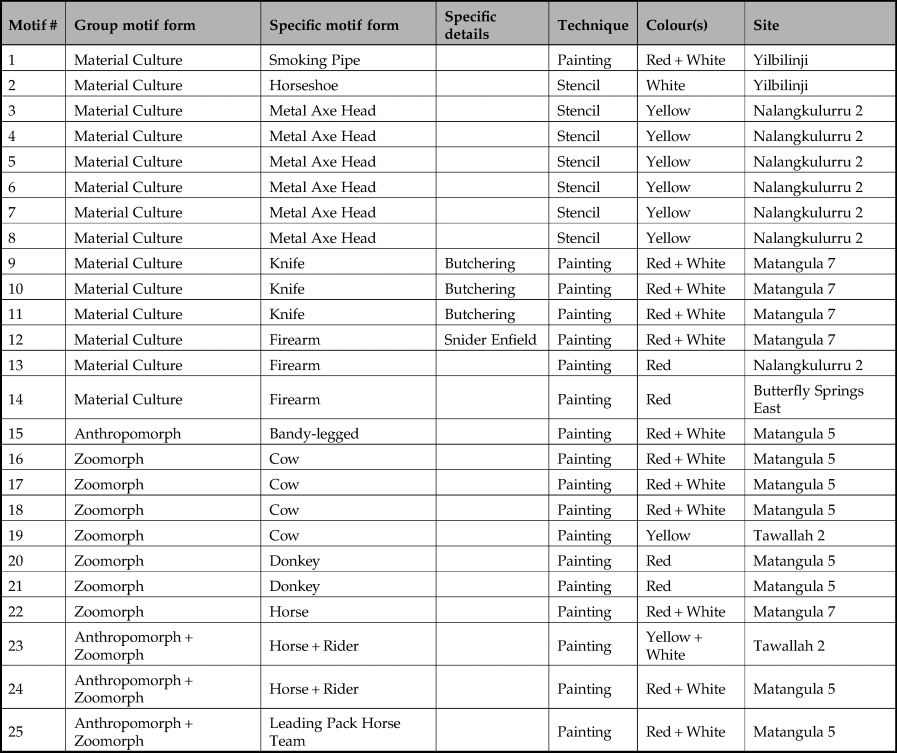

A total of 25 motifs thought to depict European introduced subject matter have been recorded from seven sites inside Limmen National Park (Table 1). An additional motif, a dugout canoe, can also be characterized as introduced, given they were obtained from Macassans at the end of each trepanging season. Prior to this, bark canoes were used for sea- and river-going travel (Kearney & Bradley Reference Kearney and Bradley2015). However, as the dugout canoe cannot be attributed to a European origin it is excluded from further analysis. The majority of motifs are located at Matangula (n = 13), followed by Nalangkulurru 2 (n = 7). Motifs are located in rock-shelters of varying dimensions and placement in the landscape (flat plains, mid- or upper-slope). All motifs are pigment-based (paintings n = 18 and stencils n = 7), have been produced on the rear walls or roof of the rock-shelter and are monochrome (n = 12) or bichrome (n = 13), with three colours documented: red, white, yellow (see Table 1). Motifs are depicted in varying degrees of detail: simple or plain and lacking decoration; hybrid motifs where there is a transitioning of features such as traditional and introduced subject matter; and highly detailed motifs reflecting an intimate knowledge of the object, animal, or person depicted.

Table 1. Classification of introduced subject matter from Marra Country, Limmen National Park.

Motifs were classified in a two-level hierarchical format to explore variation in the assemblage (Table 1). Four Group Motif Forms were identified—Material Culture, Anthropomorph, Zoomorph, Anthropomorph + Zoomorph. Material Culture dominated the assemblage (n = 14), followed by Zoomorphs (n = 7), Anthropomorph + Zoomorph (n = 3) and one Anthropomorph. Classification was further refined according to a Specific Motif Form (e.g. Firearm, Horse) with Metal Axe Heads the most frequently depicted introduced subject matter. In three instances (Smoking Pipe, Bandy-legged Anthropomorph and Horse + Rider at Matangula 5), traditional imagery has been depicted overlying the introduced subject matter, indicating painting activity was continuing after the European-themed motifs were created.

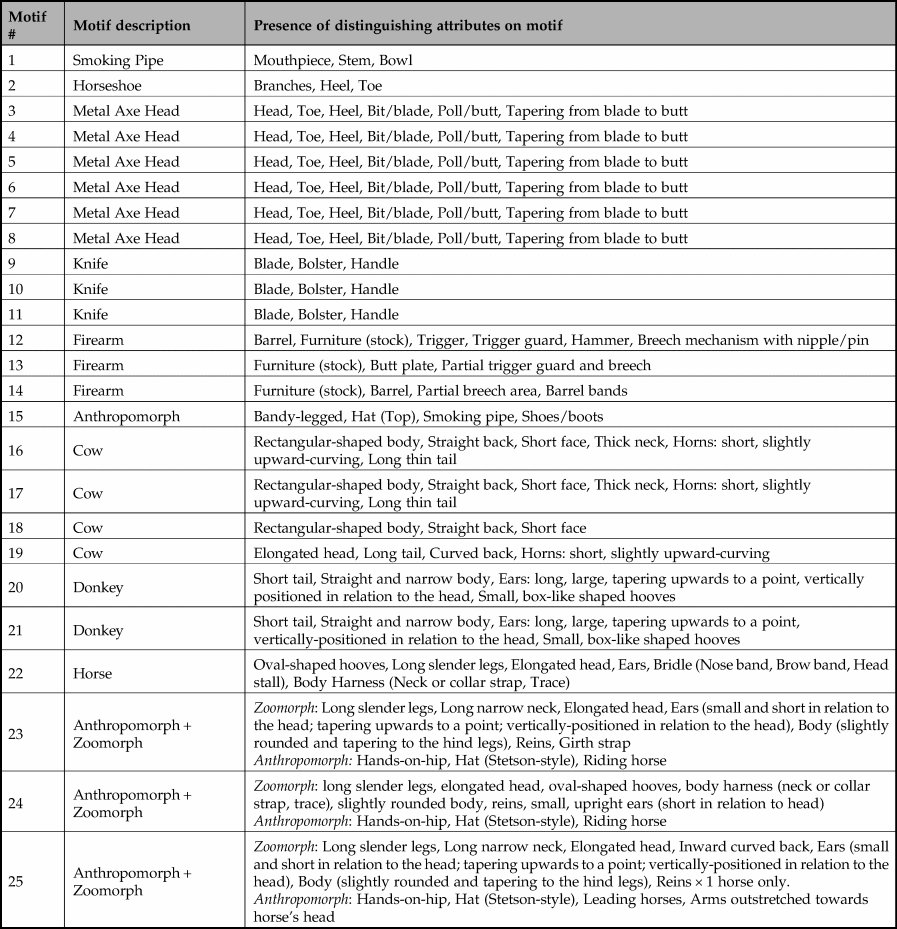

Since these are the first recordings of introduced subject matter in the region, a systematic framework for identifying and categorizing motifs was developed, based on the absence/presence of specific characteristics or attributes reflective of European influence (Table 2). Often the differences between introduced subject matter can be subtle, such as the morphological difference between a horse and donkey—a distinction that can have implications for examining the possible context(s) in which a motif is produced (e.g. Frederick Reference Frederick1999; Taçon et al. Reference Taçon, May, Fallon, Travers, Wesley and Lamilami2010). In our project, attributes are derived from various resources and provide descriptions and illustrations of key features such as the names of horse accoutrements (e.g., bridle, throat latch), all of which can be used to create a highly accurate motif identification. Whereas other presence/absence attribute frameworks have targeted only specific motif types such as watercraft and firearms (e.g. Wesley Reference Wesley2013; Wesley et al. Reference Wesley, McKinnon and Raupp2012), our analysis covers a much wider range of motif types, thus adding additional attributes to studies targeting accurate identification of introduced subject matter.

Table 2. List of specific characteristics or attributes for introduced subject matter from Marra Country, Limmen National Park.

The majority of motifs correspond with the key attributes identified for each object, zoomorph, or anthropomorph + zoomorph, and in several instances allow for a more specific identification. Upon closer examination, knife motifs have been specifically identified as butchering knives, and firearms as common rifles (carbines) found in the pastoral industry.

Some notable features not included in the attributes-based description of the assemblage are:

• Dot outlines: a characteristic feature of non-introduced subject matter motifs from the southwest Gulf country consists of both white dot outlines (typically found around infill motifs) and motifs created entirely using dots (Brady & Bradley Reference Brady and Bradley2014). However, the former has been recorded on the Bandy-legged anthropomoroph at Matangula 5 (Fig. 3), hybrid Horse (Matangula 7) (Fig. 4) and the Leading Pack Horse Team motif (Fig. 5), indicating continuity in the use of a region-specific design convention into introduced subject matter

• Writing: at Matangula 5, the Horse + Rider motif features a rare instance of writing on a horse (Fig. 6). The letters ‘JOE’ are vertically written twice—immediately in front of and behind the rider. Two other letters, ‘OE’, are written on the horse's neck. The only reference we have been able to find relating to ‘JOE’ in a horse-and-rider context is from Costello's son's memoir. Costello describes how, upon abandoning Valley of Springs Station in the 1890s, his father travelled to his other property, Lake Nash on the Barkly Tablelands. At Lake Nash, he notes the role of his father's horse: ‘[m]ounted on his wonderful blood horse, “Joe,” the pair were a unit of enthusiasm for their work’ (Costello Reference Costello1930, 197). Whether this reference refers to the painting is difficult to ascertain. Whatever the case, the highly detailed depiction of the horse-and-rider motif indicates the artist was very familiar with horses, probably through riding or other close-up encounters with horses.

• Hybrids: at Matangula 7, a possible hybrid motif features characteristics of a dingo and a horse (see Figure 4). We have chosen to identify it as a horse because 1) the animal has hooves, not paws like a dingo would; 2) pointed ears rather than rounded; and 3) white dots on its head are in the correct place for a bridle and on the body for a saddle, and the hump on the back could be a saddle or saddle bags. The upward-curved, dingo-like tail is somewhat problematic. It is possible the artist might have painted a dingo first (with a curved tail), and then they (or someone else) returned later and decided to change it to a horse, or the artist drew the horse tail flicking upwards (see e.g. Taçon et al. Reference Taçon, Ross, Paterson, May, McDonald and Veth2012, 424).

Figure 3. Matangula 5: motif depicting a man smoking a pipe and outlined in white dots; two cows are located on the left and right sides of the panel.

Figure 4. Matangula 7: horse motif outlined with white dots.

Figure 5. Matangula 5: panel showing an anthropomorph leading a team of pack horses with the horses outlined with white dots, and a cow in the bottom left of the panel.

Figure 6. Matangula 5: detailed depiction of a man riding a horse; note the words ‘JOE’ painted on the horse's body, and ‘OE’ on the horse's neck.

What is of interest with this assemblage is the quantity and types of motifs that can potentially be linked to the pastoral industry. Based on our analysis, at least half of the assemblage has direct links to the industry. While others could tangentially be linked to pastoralism (axes and pipes), it is difficult to link them because of a lack of a direct relationship with pastoralism (Fig. 7). Therefore, of principal interest are zoomorphs, anthropomorphs, firearms and knives.

Figure 7. Introduced subject matter from Marra Country not directly related to the pastoral industry (clockwise from upper left): horseshoe-shape, firearm, firearm, metal axes, smoking pipe.

Zoomorphs: Three classes of zoomorphs are directly related to the pastoral industry: 1) donkeys were involved in droving activities of pastoralists and were used primarily as pack animals if horses were unavailable. Their depictions are characterized by straight, narrow bodies, short tails, ears (long, large, tapering upwards to a point, vertically positioned in relation to the head) and small box-like shaped hooves (Fig. 8); 2) cows were the core of the pastoral industry and Aboriginal stockworkers would have had extensive involvement with them. Their depictions are characterized by rectangular-shaped bodies, straight backs, short faces, thick necks, long thin tails and short, slightly upward-curving horns (see Figs 3 & 5); and 3) horses, also at the centre of pastoral activities through droving. Stockworkers would either have been riding them or caring for them and thus intimately familiar with their physical appearance. They are characterized by key features such as long slender legs, elongated head, oval-shaped hooves, bridle (nose band, brow band, head stall), body harness (neck or collar strap, trace), slightly rounded body, reins, girth strap and small ears (short in relation to head) and tapering upwards to a point (see Figs 5 & 6).

Figure 8. Two donkey motifs at Matangula 5.

Anthropomorphs: the only anthropomorphs directly related to the pastoral industry are those either seated on horses, or leading cattle or pack-horses. The latter are characterized by Stetson-style hats (see Figs 5, 6 & 9).

Figure 9. Man on horse positioned above a cow motif (Tawallah 2).

Three motifs can be identified as firearms; however, only one can be reliably identified to a specific type. The Matangula 7 firearm motif has the characteristics of the large-calibre Snider Enfield carbine with key identifying characteristics including the hammer and the unique firing pin situated in a nipple on the breech block cylinder (Figs 10, 11). The Snider Enfield carbine and rifle were popular among early settlers, miners, buffalo shooters and pastoralists in the Northern Territory during the late nineteenth century (Wesley Reference Wesley2013). This rifle was known to be distributed to Aboriginal men working in the buffalo shooting industry (May et al. Reference May, Wesley, Goldhahn, Litster and Manera2017; Wesley Reference Wesley2013). The two other firearm motifs only have generic features present (firearm furniture [stock], barrel bands), and not enough specific attributes to identify these reliably to a particular make and model.

Figure 10. Butchering knives and Snider Enfield rifle at Matangula 7. (Left) original; (right) digitally enhanced.

Figure 11. (Above) Advertisement for butchering and skinning knives. (Montgomery Ward & Co. Catalogue and Buyers Guide No. 93, 1920. https://archive.org/details/MontgomeryWardCat1920tools); (below) Snider Enfield rifle. (Australian War Memorial REL/10253.)

The same panel at Matangula 7 with the Snider Enfield carbine motif includes three motifs classified as knives owing to their distinctive shape with a blade and handle (Figs 10, 11). These motifs are interpreted as butchering knives typically used in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries (Horowitz Reference Horowitz2006, 35). Two of the motifs are similar to butcher/boning knives while the third has the characteristic shape of a skinning knife (Horowitz Reference Horowitz2006, 35). Specialized roles that Aboriginal stockmen carried out on pastoral stations included butchering livestock (McGrath Reference McGrath and Dodson1997, 12). Metal knives have been found at Aboriginal campsites associated with early twentieth-century pastoral stations (Smith Reference Smith2001, 28).

Discussion

In Marra Country, opportunities for economic relationships with outsiders were significantly less than in western Arnhem Land where the trepang, buffalo-hunting and pastoral industries were well established by the late 1800s. It is highly likely some Marra people would have worked alongside the Macassans in some capacity and while early economic relationships may have occurred during the Gulf Coast Track travels of pastoralists/drovers, the frequent conflict occurring during this period was not conducive for building of exchange-based relationships. Third, and most significant, would be pastoralism where permanent settlement was established in the region. Cattle spearing by the Marra during the 1870-1900 phase (see above) can be characterized as part of the Indigenous customary economy. Cattle spearing was structured around Indigenous knowledge systems, particularly advantages of the dry and wet season (Costello Reference Costello1930, 130–31; Roberts Reference Roberts2005, 166). With the introduction of European market and state economies, there was a reorganization of Indigenous mobility to engage with the new hybrid economies as groups synchronized to new economic ‘seasons’ of the introduced terrestrial (pastoralism) economies as well as sustaining social and customary practices. In this sense, Aboriginal people were not passive bystanders to the changes occurring, but rather active agents in reinforcing relationships to country through graphic symbols of their role in the hybrid economy.

Marra involvement in the pastoral industry

While Aboriginal involvement in the northern Australian pastoral industry has been the focus of much historical research (e.g. Baker Reference Baker1989; Jebb Reference Jebb2002; McGrath Reference McGrath1987), the Marra story has been largely overlooked. Apart from ‘Dick’, who worked briefly on Costello's Valley of Springs Station, there are very few specific references to how or where Marra people became involved in this industry.

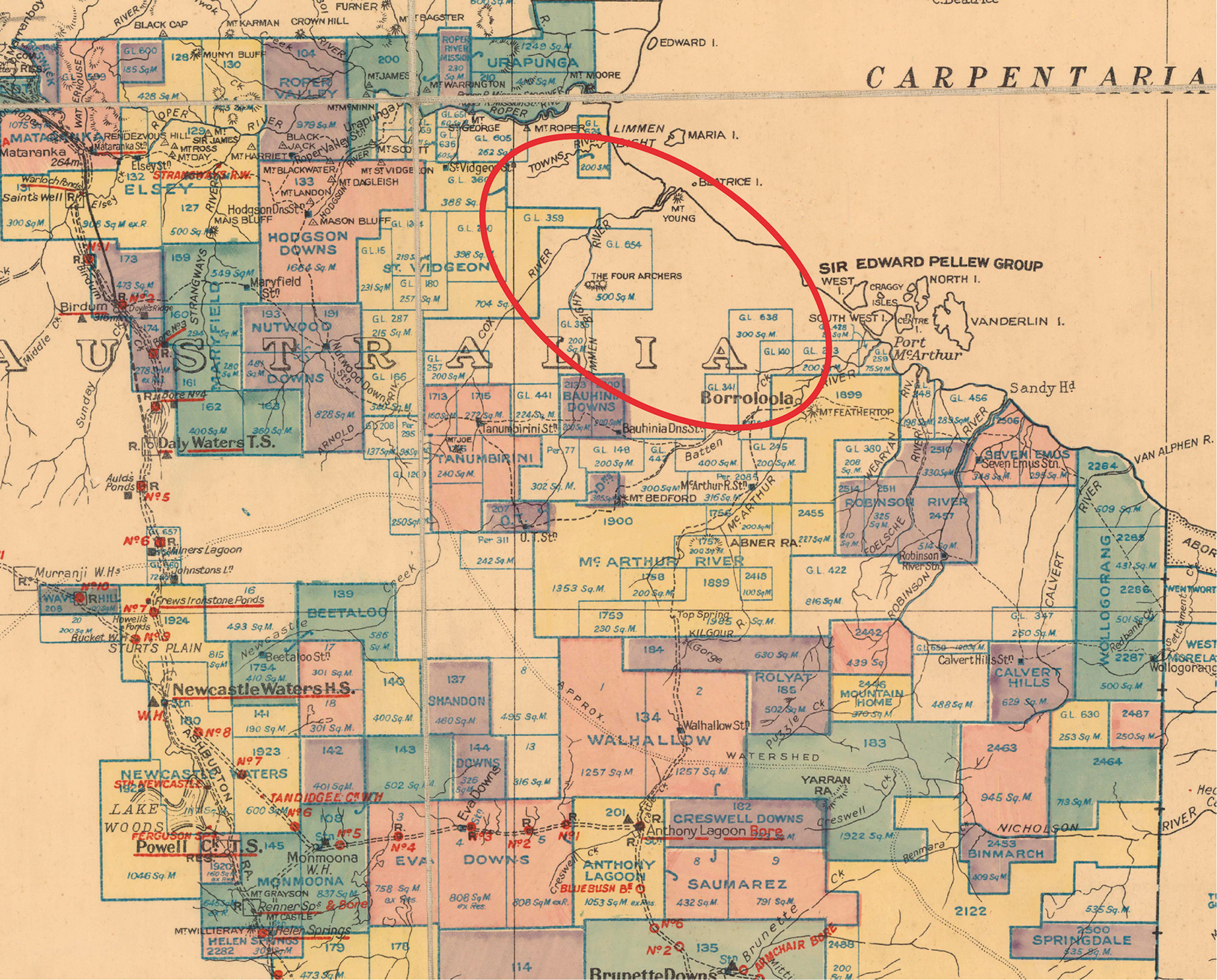

Dickson (Reference Dickson2015) noted that the establishment of the Roper River Mission (near present-day Ngukurr) in 1908 coincided with the revival of the pastoral industry in the region. During this time, Marra people living on the Roper River Missions had ‘increased sedentariness’ while others were involved in the pastoral industry, often travelling long distances from Marra Country. Dickson notes that during this time ‘[a] number of stations south of the Roper River were fully operational and employed considerable numbers of people. This included stations such as St. Vidgeon [inside Marra Country], Urapunga, Moroak, Roper Valley, Elsey, Hodgson Down, Hodgson River, Nutwood Downs, Bauhinia Downs, Tanumbirini and O.T. Downs’ (Dickson Reference Dickson2015, 79; Fig. 12). By 1940, the Marra had a strong presence at the Roper River Mission, although many were still living and working on pastoral stations, other missions, and in Borroloola.

Figure 12. Map showing location of pastoral stations in the southwestern Gulf of Carpentaria region in 1933. Red oval shows Marra Country; note the absence of pastoral stations from Marra Country. (From ‘Map of Northern Territory Showing Pastoral Stations’. Canberra: H.E.C. Robinson, 1933.)

In the Limmen Bight Land Claim report, Bern et al. (1980, 16) state that ‘by 1911 all the traditional Mara [Marra]/Wandarang country had been invaded. Many of their countrymen and women had been killed and many had been kidnapped and pressed into European enterprises [likely pastoral work], sometimes at great distances from their traditional range’. Furthermore, ‘[b]y the 1950's the Mara [Marra]/Wandarang people had been dispersed over the various European centres of settlement, including cattle stations as well as the township of Borroloola and the Church Missionary Society settlement on the Roper River (now Ngukurr)’ (Bern et al. Reference Bern, McLaughlin and Larbalestier1980, 15).

Bradley (Reference Bradley2018) noted that at the end of the Second World War, some Marra Families remained on the coastal and lower reaches of the Limmen River in dugout canoes, intent on maintaining connection with their country using Wunubarryi and Wamungku lagoon as bases and travelling between Bing Bong to the southeast of the Limmen Bight and the mouth of the Roper River to the northwest. However, inland, other groups of Marra Families began working on pastoral stations such as Bauhinia Downs and newly established Nathan River Station, and Lorella Station. In so doing, they were also maintaining connections and knowledge about these inland areas. At times, these Families would meet at various places in Marra Country such as Wunubarryi in the 1950s, where major ceremonies such as Kunabibi were held for the last time in Marra Country.

However, as the coastal and inland Marra Families grew older, they eventually left the coast and pastoral stations and moved to Ngukurr, Numbulwar and Borroloola. In their place, younger men began working on the pastoral stations as seasonal workers until major changes occurred in the industry in the late 1960s, such as the establishment of equal wages for Aboriginal stockworkers (meaning pastoral stations could no longer rely on cheap labour) and replacement of horses for mustering. From this time onwards, Marra involvement in the pastoral industry rapidly declined.

Three oral histories collected by Dickson provide insight into Marra relationships with the pastoral industry. Senior Marra woman Topsy Mindirriju Numamurdirdi (estimated to have been born around 1930) remained living on country for at least two decades, at a time when ‘the majority of Marra people were living or interacting to a great degree with Munanga [non-Indigenous people] and the culture, via missions, stations or the town of Borroloola’ (Dickson Reference Dickson2015, 77). Another senior Marra speaker, probably of a similar age, Fanny Gathawuy Numamurdirdi spoke of her time working on pastoral stations and living at stock camps at Tanumbirini Station, O.T. Downs and Bauhinia Downs. She described how ‘[w]e lived there (for a long time), alright’, and how they would ride on horseback to muster cattle (Dickson Reference Dickson2015, 402–6) before moving to Borroloola, then Numbulwar, and finally back to coastal Marra Country. Holly Ngarlilwarra Daniels spoke of her experiences at Tanumbirini Station in the 1950s. She described her role to ‘collect eggs, milk the goats or sometimes we'd muster the horses for the stockmen’ (Dickson Reference Dickson2015, 409).

Material from the adjacent Yanyuwa people adds further details that are applicable to understanding Marra involvement in the pastoral industry. Bradley (Reference Bradley1997, 409; see also Baker Reference Baker1989) noted that from the late 1920s onwards, some Yanyuwa and Marra people were involved in some form of stockwork on local or more distant pastoral stations. During the Second World War, the Yanyuwa were forcibly relocated from the Sir Edward Pellew Islands to Borroloola. Borroloola at that time was a gathering place for many Aboriginal groups in the southwest Gulf country including the Marra, and many were ‘recruited’ or sent away by the government's Welfare Branch for pastoral station work on the Barkly Tablelands several hundred kilometres south (e.g. Brunette Downs, Anthony Lagoon) and also into central-western Queensland. In 1944, Bill Harney (Patrol Officer from the Department of Native Affairs) wrote, ‘[d]uring the last four years, a systematic cleaning out of these people has been going on and on my recent patrol of the Barkly Tablelands I was amazed at the number of coastal people who were sent out of Borroloola by the local protectors there’ (Harney Reference Harney1944, 1–20).

The pattern of residence that operated during this time for the Yanyuwa and Marra involved spending the dry season on the station undertaking all types of stockwork, and when the wet season commenced, Yanyuwa and Marra people were ‘trucked back to Borroloola’ by pastoral station owners. Yanyuwa and Marra then travelled back to their country to live, hunt and carry out important ceremonies before returning to the stations at the beginning of the dry season. This pattern of removal and return to pastoral stations lasted until the early 1970s.

Hybrid economies and rock art

Based on the historical, anthropological and archaeological evidence, we suggest that a hybrid economy was operating in Marra Country. Within this model, we also suggest that an additional intercultural field existed at the intersection of the Indigenous customary sector with the state and/or the market sectors. This intercultural field reflects the dynamic dimensions of the model to accommodate transformations in each sector based on the agency of Indigenous decision-making according to customary law, practice and knowledge. Wesley (Reference Wesley2015, 50) identified at least five different market economies operating in western Arnhem Land in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, whereas only two market economies, pastoralism and mission-based subsistence production, were effectively operating on, or near, Marra Country. The state economy is largely absent in the southwest Gulf country until later in the twentieth century and enforced indirectly via missions. Altman (Reference Altman2007, 7) suggests the operation of a hybrid economy is indicative of Indigenous communities being ‘empowered to pursue a livelihood approach that suits their particular circumstances’. The production of introduced subject matter demonstrates that, despite the challenges of Marra negotiating changes within colonial contexts, they continued to make decisions that privileged their traditions, namely the production of rock art. Thus, the introduced subject matter is an example of both Marra mobility in land use and occupation, along with participation in the western colonial economy and engagement in a single market economy sector. Labour was key for the settler production system and generally the experiences for Indigenous people were characterized by a process of coercion, transport, manipulation and force (Lloyd Reference Lloyd and Keen2010, 35). It was largely after the frontiers were subdued that Indigenous labour began to be exploited in significant numbers in the Northern Territory. This labour history is particularly complex for Marra people (see above) and involved a high level of mobility and travel in their involvement in the pastoral industry rather than occurring only on their country.

The introduction of pastoralism in the region meant an adjustment occurred to the way the Marra engaged with their country that was influenced by the seasonality model of economic production, with mustering activities carried out in the dry season. A significant aspect of the hybrid economy model is the recognition that ‘Indigenous people regularly move between … occupational niches with the mobility evident in pre-colonial times’ (Altman Reference Altman2007, 4). Altman (Reference Altman, Taylor, Ward, Henderson, Davis and Wallis2005, 39) also proposes that engagement with hybrid economies provides Indigenous communities the opportunity to ‘make decisions about the trade-off between engagement and isolation’. Therefore, Marra Families involved in the pastoral industry could return to country during the wet season and carry out traditional obligations such as ceremonies, and the production of rock art that in some instances referenced pastoral engagement (see also Frederick Reference Frederick, McDonald and Veth2012, 411; Paterson Reference Paterson, Oland, Hart and Frink2012; Smith Reference Smith2001). However, it is interesting to note that, unlike the Yolngu people of northeast Arnhem Land, exotic or introduced items do not appear to have been absorbed into Marra ontological and epistemological foundations (Buku-Larrngay Mulka Centre 1999). Why this is the case is difficult to pinpoint: it could be an innate conservatism; however, such a question requires a deeper ontological reasoning that is beyond this paper to answer. It is these patterns of mobility—travels to distant stations—that are useful when considering how knowledge of the pastoral industry and economy was brought back onto Marra Country. In addition, government maps of Northern Territory Pastoral Stations from 1933 and 1945 do not show any operational pastoral stations in our study area, although others are located nearby, such as Bauhinia Downs (est. 1883) and Hodgson Downs (est. 1884–5), and Nathan River Station from the early 1960s (Fig. 12). This relative absence of pastoral stations, and patterns of mobility, suggest Marra artists returning to country during the wet season, or upon leaving the pastoral industry entirely, would arrive with intimate knowledge of the objects, animals and people associated with the pastoral industry. Their depictions at various places throughout the Marra landscape thus become key markers of their understanding and relationships with the pastoral economy.

The presence of the firearm and knife motifs are particularly significant as they speak to the complex nature and inter-linkages of the hybrid economy as well as customary practices, rather than simply illustrating items of introduced material culture. The knife and firearm motifs demonstrate the complex interlinkages between the customary and market economies. The importance of cattle as a resource for Indigenous Australians living and working on pastoral stations has been well documented (see Pickering Reference Pickering1995; Redmond Reference Redmond2015). McGrath (Reference McGrath1987) argues that Aboriginal people incorporated pastoralism and cattle into their world through conscious integration. Butchering livestock was a common practice and critical to the economic survival of pastoral stations in the Northern Territory, with some pastoralists referred to as ‘butcher-pastoralists’ in the Darwin hinterland in the early twentieth century (Chapman Reference Chapman1958, 116). The practice of slaughtering cattle for consumption by the pastoral station staff and Indigenous workforce was common, and the butchered cattle were known as a ‘killer’ (Jorgensen Reference Jorgensen2017, 109). The killer was immensely important for Indigenous people living and working on pastoral stations. The butchering knives found in the rock-art assemblage are more than just functional objects; they are part of complex networks involving cattle as a social resource. In his research on cattle stations in the Kimberley, Davis (Reference Davis2004, 28) noted that ‘the act of killing it [cattle] is also a display, on the part of the butchers, of affiliation to the land it roamed across’. Pickering (Reference Pickering1995) noted that, although Aboriginal butchering of cattle used steel knives and axes, the butchering strategy employed was still uniquely Indigenous. Thus, there is a significant customary context to the identity of the butcher and the butchering process, a context that is embedded in social relationships, ownership and land affiliation.

Chronology

Despite tensions, systematic violence and significant impacts on Marra society, the detailed and careful depiction of livestock and European material culture at first appears at odds with the Marra experiences with Europeans. Bern et al. (1980, 12) note that by 1907, only Hodgson Downs and Nutwood Downs remained occupied in the region. Bleakley (Reference Bleakley1929, 22) noted that during his visit to the Roper River Mission in 1928 there were around 300 cattle, 48 horses and approximately 300 goats. Even though there were fewer pastoral stations located on Marra Country, the introduced subject matter could represent the activities of Marra people engaged to work at the Roper River Mission, on pastoral stations adjacent to, and at significant distances from, Marra Country. The firearms depicted in Marra rock art are consistent with the types of rifles in use in the Northern Territory from the 1870s to the early twentieth century. The motif depicting a Snider Enfield carbine at Matangula 7 is typical of the type of rifle that was given to Aboriginal stockmen and buffalo shooters elsewhere in the Top End (May et al. 2017; Wesley Reference Wesley2013). It was a preference for Europeans to provide obsolete firearms to Indigenous stockmen as they were inexpensive unlike later models.

Thus, while the motifs could reference Europeans droving cattle through Matangula on their way westwards, the majority of the rock-art contact imagery is more likely to be representative of the third historical phase identified for the southwest Gulf region (post-1900). Marra people were known to still be on country through the 1950s to the late 1960s (Bradley Reference Bradley2018; Dickson Reference Dickson2015, 87). Therefore, it is very likely that rock-art production continued on Marra Country through to the mid-twentieth century.

Conclusion

Rock-art motifs depicting introduced subject matter are valuable symbols of cross-cultural interaction with the other. How this interaction is characterized or interpreted according to rock-art motifs varies across the globe. In this article we have used an assemblage of introduced subject matter from northern Australia's southwestern Gulf of Carpentaria region to argue that they can best be interpreted in the context of a hybrid-economy model. Their visual association with the pastoral industry as seen through motifs such as butchering knives, Snider Enfield rifle, cattle and horses + riders are indicative not only of new experiences involving unfamiliar objects and animals, but when placed in a hybrid economic framework are shown to be part of a complex network intertwining the market, state and customary components of the pastoral economy. While we have applied Altman's hybrid economy model to an Australian case study, we suggest such a framework could also potentially be used outside Australia, in places where introduced subject matter is intertwined with colonialist economies to provide a more nuanced approach to understanding the nature of the forces that shape people's changing engagement with their surrounding landscape.

Acknowledgements

Special thanks to Marra Families for their help with this research and sharing their knowledge about the sites and motifs discussed. Thanks also to Peter Cooke and Eddie Webber for insightful discussions about the archaeology and history of Limmen National Park. Fieldwork was supported by the Marra Rangers and the Parks & Wildlife Commission of the Northern Territory, in particular Glenn Durie (Manager, Capacity Building and Aboriginal Engagement) and the PWCNT Rangers. Thanks to Peter Cooke for supplying Figure 7 (outlined rifle) and Figure 9. This research is funded by the Australian Research Council (DP170101083, DE170101447, FT180100038).