I'll work under the table all my life, even if I know I'll be a millionaire. I'll keep collecting welfare my whole life … I'll do it because of the anger inside of me … due to the injustice, their stupid rules, for making us slaves to their criteria. (Nitza, Israeli female welfare recipient)

Nitza, a single mother, is 33 years old with three young children. She has been living on welfare for several years, since the birth of her first child. Before becoming a mother, she had worked consistently. The father of her children comes and goes. Although he has tried to help with child support, his financial situation has deteriorated over time, and he too is on welfare. Nitza takes any work she can get, but never reports her income to the National Insurance Institute (NII)Footnote 1 even though she knows she is required to do so. She did not also notify the authorities when the father of her children came back to live with her in the apartment she was renting because she knew it would disentitle her to welfare benefits. After failing to pay her rent for a few months, Nitza left the flat and squatted with her children in a public housing apartment, from which she was eventually forcefully evicted by the police.

In this paper, I draw on 49 in-depth interviews with Israeli female welfare recipients, like Nitza, to investigate whether their seemingly unrelated individual acts of noncompliance with welfare laws are connected. I have shown that although the fraudulent behavior of these women encompasses a political claim against the Israeli welfare state—and constitutes acts of individual resistance—it has an extremely weak connection to any coherent ideological perspective or collective practices of social support. The women's system of social support is severely restricted due to the Israeli welfare state's fraud investigation tactics of home visits and obtaining information on recipients through informants, which shape and fragmentize the women's collective practices. As a result, the women are trapped in individual resistance, and the potential of their acts to generate any social change seems quite slim.

Since the late 1950s, historical, sociological, and socio-legal studies have been documenting fraudulent acts and cheating engaged in by the poor during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries in various contexts, including across England (Reference ThompsonThompson 1980) and Italy (Reference HobsbawmHobsbawm 1959), in the slums of Mumbai, India (Reference BooBoo 2013), in rural Malaysia (Reference ScottScott 1985, Reference Scott1990), in urban U.S. cities (Reference DeParleDeParle 2004; Reference Edin and LeinEdin and Lein 1997; Reference Ewick and SilbeyEwick and Silbey 1998; Reference GilliomGilliom 2001; Reference SaratSarat 1990; Reference WhiteWhite 1990), and in the context of black slavery in South America (Reference BuckmasterBuckmaster 1959; Reference GenoveseGenovese 1976). At the same time, rich debate has arisen over the essence of these types of acts, specifically whether they constitute individualistic, opportunistic acts, or a form of protest and resistance. Some scholars, in their descriptions of fraudulent acts by the poor, portray them as opportunistic, individual acts of survival, devoid of any political dimension (Reference BooBoo 2013; Reference DeParleDeParle 2004; Reference Edin and LeinEdin and Lein 1997). In line with this perception, traditional literature on welfare fraud views this behavior as an individual criminal activity (e.g., Reference Evason and WoodsEvason and Woods 1995; Reference LovelandLoveland 1989; Reference MacDonaldMacDonald 1994; Reference McKeeverMcKeever 1999; Reference MartinMartin 1992; Reference RowlingsonRowlingson et al. 1997; Reference Sainsbury and MillarSainsbury 2003; Reference SeccombeSeccombe 2011). In contrast, other scholars treat such acts as political in nature. Initially, these scholars examined the possible consistency and divergences between acts conducted by the poor and social movements and collective struggles (e.g., Reference BuckmasterBuckmaster 1959; Reference GenoveseGenovese 1976; Reference HobsbawmHobsbawm 1959; Reference PivenPiven 1979; Reference ScottScott 1985; Reference ThompsonThompson 1980). The study of the actions of peasants, bandits, slaves, and the urban poor through the prism of social movement struggles was based on the conviction that collective forms of struggles are vital for altering the existing structures of social power. This premise is grounded on the notion that collective action derives its power from a coherent ideological claim and some form of organization that enables coordination of economic and political resources, allows strategic use of these resources, and ensures the continuity of lower class political mobilization over time (Reference PivenPiven 1979).

Scholars differ as to the potential of these resistant practices to initiate structural change. Although most do agree that a coherent ideological claim and system of organization are crucial for effective resistance, they vary as to whether these features are observable in concrete historical instances of resistance. Reference ScottScott (1985), for example, analyzed acts of passive noncompliance, evasion, and deception in a Malaysian village as forms of class struggle with real potential to escalate and transform the power structure, since they represent a conscious claim against the rich and are fairly coordinated and organized. However, studying the rural “social bandit” and the “city mob,” Reference HobsbawmHobsbawm (1959) argued that these phenomena constitute a primitive and archaic form of resistance, as they present a simplistic ideological claim—of the poor against the rich—and a very limited form of organization. Nonetheless—whether historically present or not—both of these scholars seem to agree that for such acts of “protest from below” to be effective, a coherent ideological claim and collective practices supporting coordination and organization of resources are imperative.

Since the mid-1980s, a vast body of scholarly work has continued to develop the conception of resistance (Reference Abu-LughodAbu-Lughod 1990; Reference ComaroffComaroff 1985; Reference Dean and MelroseDean and Melrose 1996, Reference Dean and Melrose1997; Reference Ewick and SilbeyEwick and Silbey 1992, Reference Ewick and Silbey1998, Reference Ewick and Silbey2003; Reference Jordan, Drover and KeransJordan 1993; Reference GilliomGilliom 2001; Reference SaratSarat 1990; Reference WhiteWhite 1990; Reference YngvessonYngvesson 1993; Reference ZivZiv 2004). Similar to the earlier writings on resistance, this later literature emphasizes the power dynamics at play in the struggles of the poor. By highlighting their individual struggles and subversions, it sheds new light on the poor—and, more specifically, welfare recipients—and shatters the image of the helpless, simple, passive, unsophisticated person who surrenders to a hegemonic ideology. This form of individual resistance was celebrated and lauded by scholars (Reference GilliomGilliom 2001; Reference SaratSarat 1990; Reference WhiteWhite 1990; Reference ZivZiv 2004) for exposing “the inherent instability of seemingly hegemonic structures, that power is diffused throughout society, and that there are multiple possibilities for resistance by oppressed people” (Reference HandlerHandler 1992: 697–698). Thus, in contrast to the earlier protest-from-below research, a central focus of the later studies was the power of individuals. Consequently, they abandoned the theoretical approach connecting individual acts of noncompliance with collective struggles. As Reference McCann and MarchMcCann and March noted, “[t]he resistances they [the later scholars] celebrate are not directly or extensively connected to battles over the manifestation of racism, poverty, patriarchal control, or workplace exploitation, but almost exclusively concern direct tactical maneuvering against judges, clerks, mediators, administrators, or other officials associated with the state” (1996: 220). These acts are performed by isolated individuals, and commonalities linking them together exist only in the minds of the narrators (Reference HandlerHandler 1992). These analyses have abandoned the notion that collective action is necessary for generating social change and, instead, underscore the power of individuals.

This shift in focus, however, raises imperative questions regarding the transformative power of these individual acts to effect social and structural change. As Handler noted, overall, the later studies paint a pessimistic picture of the usefulness and effectiveness of these acts in attaining change. The stories of resistance do not end in reform of the law and practices, and the heroes of these stories remain poor and reviled (Reference HandlerHandler 1992).

In fact, both approaches to “protest from below,” in Reference HandlerHandler's (1992) terms, are flawed in their conceptualizations and understandings of these practices and their potential to initiate broad social change. The individualistic conception of resistance ignores the issue of effecting change altogether. The collective understanding, in contrast, seems to rest on the premise that if only the poor would organize, they could mobilize their power and bring about change; what it fails to take into account is the state's ability to dismantle groups of collectivity.

Heeding this theoretical criticism, this paper aims to return the analytical focus to the collective aspects of individual noncompliance acts and to examine the dynamics that support or hinder collectivity as a proxy for the socially transformative potential of individual acts of resistance through welfare fraud. Thus, it supports the contention that struggles must take a collective form in order to generate change (e.g., Reference HandlerHandler 1992; Reference McCann and MarchMcCann and March 1996; Reference PivenPiven 2006; Reference RubinRubin 1996; Reference TarrowTarrow 2011) and stresses the collective aspects of individual fraudulent behavior. At the same time, it illuminates the state's generally ignored role in the formation and fragmentization of these collective elements.

The theoretical analysis in the paper applies “extended case method” (Reference BurawoyBurawoy 1998; Reference MitchellMitchell 1983), seeking to revisit and reformulate, rather than refute or confirm, the preexisting theory of resistance and “protest from below” and constructed on the scholarship that draws a connection between individual noncompliance and protest and resistance. Elaborating on the connection between these individual acts and collective action and exposing the dynamics that shape the collective practices that bind these individual acts, this research deepens and reformulates current resistance theory; moreover, it expands its explanatory power by incorporating an understanding of the role of the state in the formation and fragmentization of collectivity and, accordingly, the state's impact on the potential of this form of resistance to evolve into social change.

The paper proceeds as follows. The next section details my research design and methodological approach. The third section then briefly reviews the phenomenon of welfare fraud in the Israeli context. In the fourth section, I progresses to my study's finding, first briefly revisiting results I described elsewhere (Reference Regev-MessalemRegev-Messalem 2013) that when the women engage in such noncompliant acts, this conduct includes a political claim that they are entitled to state support, and as such, their fraudulent practices constitute an act of resistance against the Israeli welfare state. The fifth section explores the relationship that emerges from the women's accounts between their individual fraudulent acts and a collective ideology and collective system of social support. Lastly, I propose some interesting avenues for further research, suggesting theoretical and practical insights on individual noncompliance in general and on the phenomenon of welfare fraud in Israel in particular.

Methods

The findings and analysis presented in this paper are based on a qualitative study incorporating 49 in-depth individual interviews conducted between February 2008 and August 2009. I am well aware of the constraints of this research design, the most significant of which being the relatively small number of interviews conducted. However, since the research investigated female welfare recipients' perceptions of illegal conduct, in which they are often themselves involved, it would be highly unfeasible to ground such a study on a statistically representative sample, as it is unlikely that participants who are cold-called would agree to long, in-depth interviews on such a sensitive topic with a stranger (Reference SmallSmall 2009). Moreover, the semistructured interviews enabled information to emerge by uncovering a particular dynamic in the context of Israeli welfare recipients' noncompliance.

My research is designed as a multiple-case study (Reference SmallSmall 2009), with each individual interviewee representing a single case (Reference SmallSmall 2009; Reference YinYin 2003). Initially, I engaged in “theoretical sampling” (Reference Glaser and StraussGlaser and Strauss 2007; see also Reference TrostTrost 1986). My basic criteria for selecting a case were that the subject be a JewishFootnote 2 Israeli woman who, at the time of the interview (or in the preceding year), was receiving a state income maintenance allowanceFootnote 3 (which I refer to as “welfare benefits”). Because my initial theoretical assumption was that notions of ethnicity would be central in the women's sense of collectivity, I selected interviewees of both Mizrahi Footnote 4 and Ashkenazi Footnote 5 ethnic origin. I surmised that there might be differences between interviewees living in cities in the center of the country and peripheral cities, as well as differences between those from communities in big cities and those from communities in smaller cities (which might be more similar to close-knit communities).

Participant recruitment was based on my personal connections as a former poverty lawyer with welfare recipients and the snowball method (Reference LoflandLofland et al. 2006; Reference WeissWeiss 1994). Recognizing the limitations of these methods, however, and to avoid documenting a particular subculture within the general population of female welfare recipients in Israel, I reached out to community activists across the country to gain access to other unrelated interviewees. Contacting a new subset of interviewees, I then used the snowball method again to further expand my sample.

In conducting the interviews, I referred to a prepared list of questions for the interviewees relating to the circumstances leading to their going on welfare; their experiences with the NII; their views on concealing information from the NII; their social networks and the extent to and means by which those networks provide support; the degree to which they publicly share any noncompliance with welfare laws; their perceptions of the NII practices; their views of informants; their knowledge of the law and the legal consequences of noncompliance; and their experiences with getting caught by the NII. The interviews were open-ended and formed as casual conversations that allowed the participants to tell their personal narratives. This gave both the interviewees and me leeway to take the discussions down the unexpected paths (Reference PattonPatton 2002). The interview guide evolved over the course of the study as I refined my understanding of the relationship between noncompliance and collectivity (Reference SmallSmall 2009).

After conducting each batch of interviews, I analyzed the data to find recurring themes, which I categorized. I then indexed each interview according to the multiple categories as index keys, creating a database table that enabled a cross-comparison of the interviews and identifying logical relationships among categories. As I conducted additional interviews and my understanding of the issue deepened, some categories of analysis were abandoned, some were further developed into subcategories, and others were transformed and honed. For example, in the first round of data analysis, “resistance” was defined as any instance of direct justification of noncompliance with welfare laws. As the study progressed, however, I clarified and refined “resistance” to relate only to instances in which the women based their justifications on a claim of moral entitlement to aid from the Israeli welfare state. Moreover, I realized that there are important divergences in level of resistance and, thus, created subcategories of high-level, medium-level, and low-level resistance. High-level resistance was defined as instances in which women justified noncompliance regardless of need, framed noncompliance as a political action, and did not exhibit any sense of shame or regret. In contrast, low-level resistance referred to instances in which women justified fraudulent behavior on a claim of entitlement to state aid, but restricted this to circumstances of desperate need, thus framing such conduct more as a means of survival than a political act, with many deeming these acts to be “wrong.” In addition, two subcategories of involvement in acts of noncompliance emerged during the analysis of the data: high-level noncompliance and low-level noncompliance. High-level noncompliance was defined as conduct for which the NII would likely consider pursuing criminal prosecution; low-level noncompliance refers to minor acts of fraud that would likely result only in temporary disentitlement and debt to the NII for the fraudulently acquired benefits. This distinction was the result of my evolving understanding of the NII's typical punitive responses to different types of welfare fraud. The main criteria used in applying this distinction were as follows: the amount of money that had been obtained contra to the welfare laws, the duration of the fraudulent behavior, and whether or not several forms of fraud had been engaged in simultaneously. I also refined the category of “class” as “class awareness” and created subcategories of low-level class awareness and high-level class awareness. Cases in which “poor versus the rich” stories took a prominent place in the women's narratives and the rich were depicted in an extremely negative light were coded as instances of high-level class awareness. Low-level class awareness was deemed as present when the women expressed class-related notions but without using strong terms and emphasized the possibility of class mobility. Finally, in analyzing the data, I looked for the conditions and variables linked to high-level resistance using statistical analysis (for a similar methodological approach, see Reference RaginRagin et al. 2003).

Welfare Fraud in Israel

Welfare fraud, under Section 20(a) of the Israeli Income Maintenance Act 1981, is when a person “knowingly provides incorrect information or conceals information that he/she knows is relevant to his/her eligibility for an allowance.” This provision defines three main modes of fraud: (1) concealing income, (2) concealing the regular use of a car,Footnote 6 and (3) concealing the existence of a domestic partner. Detection of fraudulent behavior leads to the initiation of an administrative process of benefit disentitlement, debt collection, and punitive sanctions, and, in some cases, also criminal charges.

Surveillance and Investigation System

Welfare fraud is detected through an elaborate system of investigation and surveillance, in which the Israeli government invests considerable funds. In 2003, the NII employed a total of 98 investigators in its 74 branches to investigate benefits fraud (Reference SherefSheref 2004). In addition, in 2003, a special fraud unit was established, with 32 additional welfare fraud investigators devoted primarily to investigating welfare fraud (Reference SherefSheref 2004).

It should be stressed that unlike fraud investigations regarding other national insurance benefits, only a very few of the welfare fraud investigations are conducted on NII premises (Reference SherefSheref 2004); rather, the majority of the investigations take place in the recipient's environment. An investigation generally includes unannounced home visits, interrogations, surveillance, and interviews with neighbors (Reference SherefSheref 2004). Interviewees in the study described investigations and surveillance as a regular “part of their everyday life.” One interviewee described a routine of up to three house visits a year throughout all the years she has been on welfare; another interviewee told of two unannounced visits from NII investigators between 6:30 a.m. and 7:00 a.m., looking for evidence of “a man in the house.” In fact, 24 of the interviewees reported similar experiences with unannounced visits to check for a domestic partner. A few interviewees also recounted incidents in which investigators who were surveilling their home followed them to see which car they got into.

All interviewees talked of the NII's practice of questioning neighbors and using informants, who are the most common source of information investigators rely on to supplement direct evidence of fraud. Neighbors are routinely asked questions—usually disguised as simple, innocent inquiries—such as whether they know the couple living next door, whether the car parked downstairs belongs to their neighbor, or whether they know where their neighbor works. Investigators may come a few times to check a suspicion of fraud and will question a number of different neighbors. Welfare recipients tend to view this system as pervasive and difficult to defraud. The vast majority of the interviewees reported personally knowing people who had been caught in their attempts to do so and indicated that they perceive the consequences of committing fraud to be harsh and devastating.

Justifications for Welfare Fraud

Of the 49 interviewees, 47 openly and directly justified acts of welfare fraud by female recipients, including 8 interviewees who did not report fraudulent behavior of their own. Thus, only two of the interviewees, both of whom stated that they themselves do not engage in fraudulent behavior, asserted that welfare fraud cannot be justified.

In analyzing how welfare fraud is justified, I rely, for the most part, on the personal accounts of those interviewees who reported that they themselves engage in welfare fraud. As I have elaborated elsewhere in discussing these women's justifications for their welfare fraud (Reference Regev-MessalemRegev-Messalem 2013), animating their stories is an ideology—a systematic body of concepts—that serves to justify this behavior. This ideology could, of course, be a manifestation of neutralization techniques that reflect mostly what they believe makes them look better in the eyes of others or that shield them from self-blame (Reference Sykes and MatzaSykes and Matza 1957). Nonetheless, even if the ideology presented is used merely to legitimize these acts in retrospect, exploring the specific ways in which the women choose to justify their behavior is valuable in a number of respects. To begin with, even if the ideology is initially motivated—often subconsciously—by their psychological need to feel better about their own illegal activities, once it has been formulated, it acquires its own independent effect on perspectives and behavior (Reference AgnewAgnew 1994). Thus, these justifications can be seen to be an integral part of how the interviewees conceptualize welfare fraud and their relationship with the Israeli state. In addition, what is interesting is not the fact that the women justify welfare fraud but how they justify it. How people justify their criminal activities—speeding, burglary, sex offenses, tax evasion, welfare fraud, and so on—is contingent on their cultural understandings of what is or should be a mitigating or legitimizing consideration in a given situation; as such, these justifications reveal interesting social values, conflicts, and processes.

My study considers the specific conditions in which the women assert welfare fraud to be legitimate and delves into the social meaning and implications of their justifications. It exposes the fact that underlying the justifications the women offer for welfare fraud, as opposed to how other forms of delinquent behavior are commonly justified, is a political claim. Accordingly, their justifications transcend such documented neutralization techniques as “I didn't mean it,” “I didn't really hurt anybody,” “they had it coming,” “everybody's picking on me,” or “I didn't do it for myself” (Reference Matza and SykesMatza and Sykes 1961; Reference Sykes and MatzaSykes and Matza 1957); instead, they assert the moral right of mothers to receive support from the Israeli welfare state grounded on a political claim of their social contribution in caring for their children.

Welfare Fraud as Resistance

Political Claim: Ideology of Motherhood

In line with the individual resistance scholarship, I define acts of resistance as acts that involve a political claim (Reference Ewick and SilbeyEwick and Silbey 1992; Reference GilliomGilliom 2001; Reference SaratSarat 1990; Reference WhiteWhite 1990). I analytically detach the concept of resistance from the notion of collective struggles, arguing that resistant acts can be completely individual acts. However, following the earlier literature on acts of resistance by the poor (e.g., Reference GenoveseGenovese 1976; Reference HobsbawmHobsbawm 1959; Reference PivenPiven 1979; Reference ScottScott 1985; Reference ThompsonThompson 1980), I hold that the usefulness and effectiveness of these acts in generating social change is contingent on the existence of some relationship between the acts and notions of collectivity. Accordingly, I examine this aspect of the welfare fraud reported by my interviewees, as it emerges from their justifications of this behavior, in the fifth section.

As noted, underlying the justifications the interviewees in my study gave for welfare fraud was a political claim that mothers, because of their primary social contribution through childrearing, deserve state support (see also Reference Regev-MessalemRegev-Messalem 2013). Accordingly, the vast majority of the interviewees (39) spoke from an ideological perspective that holds maternal childcare to constitute an important contribution to society and, thus, that mothers—from all sectors and groups in Israeli societyFootnote 7 —should receive state support due to their childcare function. They asserted that because children are the future of the Israeli state, the state has an interest in the childcare provided by mothers and, therefore, a moral obligation to provide them with support. In other words, echoing the dominant perception in Europe (Reference Gornick and MeyersGornick and Meyers 2003), the interviewees in my study consistently indicated that they perceive children to be a public good. As one interviewee, Nurit, explained,

You're always getting looked at, and people saying ‘Oh she's getting money without working.’ But what gain is in it for me? The state gains better citizens. It is not my own personal gain.

Mira, another interviewee, expressed a similar view:

The state has an interest in childcare. If good care is given to children … they get a good education … they will eventually grow and succeed … This is something worth investing in.

Understanding children as a public good is consistent with a familial view of the relationship between the state and its citizens (Reference JonesJones 1990), as opposed to the traditional contractual conception of this relationship. Accordingly, many of the interviewees expressed the alternative perception, often referring to their relationship with—and expectations of—the Israeli welfare state in terms taken from the family context. For example, a few of the women referred to the Israeli welfare state as a “parent” who should provide support and set a good example for its citizens' children. Others referred to the Israeli welfare state metaphorically as the husband they do not have or the partner who has failed to support them, expressing the notion that the Israeli state shares responsibility for caring for their children. These women do not view the nuclear family as necessarily the primary or sole entity responsible for children's welfare, but rather consider this to be the joint responsibility of the metaphorical “extended family”: parents and the Israeli state.

The political claim made by these interviewees challenges the categorization of women who engage in welfare fraud as “undeserving” fraudsters. They claim welfare fraud to be a justified means of attaining what they are morally entitled to but that the Israeli welfare state denies them. This sense of moral entitlement to state support is so strong that they believe acts of fraud are justified to secure this support or, alternatively, that there is nothing fraudulent in such acts, despite a lack of legal entitlement to the support.

I do not claim that their ideology was the driving force behind the interviewees' acts of welfare fraud, for the simple reason that my study was not designed to uncover what motivates the women to engage in fraud. As described, the women almost unanimously noted the need to survive and sustain their families as the primary reason for committing welfare fraud.

Levels of Resistance

The interviewees' levels of resistance toward the Israeli welfare state as manifested in their justifications of welfare fraud can be best described as lying on a continuum, stretching from high-level resistance to no resistance. Four of the interviewees expressed no resistance; 27 expressed low-level resistance; 11 exhibited medium levels of resistance; and 7 presented high-level resistance.

Exemplifying low-level resistance was Nurit's attempt to minimize the moral wrongdoing in welfare fraud:

You are afraid to tell the truth and that they will see it differently. So you fix things. They cause people to lie. You skip [some facts], smooth out some of the edges. Little lies … [so as] not to get into trouble … Because you don't know what it will lead to [if you tell the truth], and the situation is already disastrous.

In contrast, Nitza demonstrated high-level resistance. The context in which she framed her justifications was not harsh, living circumstances, but rather the welfare system's unjust rules and regulations. When I asked her directly what she thinks about women who do not report their income to the NII, she did not hesitate to validate them:

I think a lot of them [hold them in high esteem]. Because I also worked like that for years. […] Every opportunity I had, I worked like that [didn't report] … And I was proud of myself, truly.

Six other interviewees displayed high levels of resistance in their justifications similar to Nitza. Although some mentioned their desperate state of need, when asked about noncompliance with the welfare authorities, their responses were in no way remorseful or indicative of any sense of shame. Instead, they openly justified and supported acts of noncompliance in general. For example, Vered, who indicated that she generally very strictly complies with the welfare laws, expressed high-level resistance, openly supporting the noncompliance of others and completely unapologetic in justifying welfare fraud. She did not merely express indifference to the notion of people defrauding the welfare system or sympathy for their actions given their harsh circumstances; rather, she framed welfare fraud as a response to a corrupt institution and therefore “salutes” those who manage to defraud it. Lila framed fraud as a response to oppression, thus also expressing a high level of resistance:

The Bedouin … I'll tell you the truth, I take my hat off to them … you say, you are crushing me? They are lifting their heads up by [defrauding the system] … They work, they have great cars, and they sign for benefits in the [NII] bureau.

Lastly, Daniella explicitly spoke about welfare fraud as a direct political reaction to the unjust cuts in welfare benefits following the 2003 Israeli welfare reform:Footnote 8

He [then-Finance Minister Bibi Netanyahu] did an awful injustice to people here. So you know what people did? They said this is what Bibi did to us, so we will defraud Bibi. We will defraud the state, and we will work under the table, we will make our money on the side, because he cut our [benefits].

As illustrated by the above passages, the women demonstrated an array of resistance levels through their justifications of welfare fraud. I now proceed to examine whether their political claim of entitlement to support from the Israeli welfare state is anchored in a broader ideological perspective and the collective practices connecting the individual acts of welfare fraud together.

Welfare Fraud and Collectivity

When the interviewees spoke about welfare fraud, their narratives implied that they view themselves as part of a collective of mothers, and accordingly, they make their claims on behalf of that collective and not solely on their own behalf. The women apply a coherent system of values to justify not only their own individual acts but also the similar acts of other members of the collective who are situated in different circumstances. In addition, the women presented a similar gender-based political claim toward the Israeli welfare state regarding their entitlement to benefits. Yet, as I have shown below, this claim constitutes, for the most part, a primitive and pre-political form of protest, for the women's ideological perspective never rises above the concrete demand for state support and is severely limited in its form of organization (Reference HobsbawmHobsbawm 1959).

A Coherent Ideological Perspective

Although in the interviews the women based their claim to entitlement to state support on the contribution they make to society as maternal caregivers, they indicated no broader ideological perspective regarding patriarchal control or gender relations in society. At no point did they explicitly challenge or directly address the patriarchal social order, and the relations and views they expressed accepted, by and large, the existing gender hierarchy. Thus, their political claim did not emerge as transcending the specific demand for benefits, nor did it appear to relate to a broader collective struggle for women's equality.

Nonetheless, some of the interviewees did articulate a certain degree of class ideology. Notions of class manifested in the interviews through simplistic, Manichean stories describing the greedy, selfish, materialistic rich as opposed to the long-suffering, kind-hearted, principled poor. This emerges clearly in Rina's rich-poor narrative:

You don't get it! It's the people who ‘have’ who are hungry for more and more … Those who don't have won't do it. Do you notice where the stingy people are? … If you are like this [closes her hand into a fist], you will get rich. If you are like this [opens her hand up], your money will run out, honey.

The same theme is echoed in Drora's narrative comparing the rich and the poor:

A rich man will always moan and complain. With all that he has, he'll still moan and complain. ‘I have debts. I owe money on the car. I haven't paid my electricity bill.’ … And you'll never hear someone who lives on welfare benefits or someone with nothing to eat complaining. You won't hear that. He'll say, ‘Thank God I have everything I need. I live like a king,’ even if he's living on bread and butter.

Adi presented a similarly simplistic perception of the rich, describing a rich man as someone who “steps on others to get ahead” and who thinks “all means are justified to attain his goal.” In contrast, she described the poor as compassionate and humane because they have experienced tremendous harshness and adversity in life. Daniella characterized the rich in similar terms:

There is the rich man who is disgusting. And there is the rich man who sometimes, even if you want to talk, it is beneath him to answer you. And the third thing is that they want you to work even if you're ‘dying’ … I never met a rich person who was nice.

Another manifestation of the women's notions of class was their identification of Israeli government ministers and Knesset (parliament) members as rich. In this respect, at least, their political claim transcends the primitive claims that Reference HobsbawmHobsbawm's (1959) social bandit or urban mob makes, in that it is an ideological claim against the government. For example, when I asked Daniella if Knesset members are rich, she replied unequivocally, “Of course!”:

[T]he simplest Knesset member, who doesn't do anything, just for being a Knesset member, gets more than NIS 40,000 [$11,500] a month. Why should he make 40,000 when I get 2,000?!

Thus, an additional dimension to the interviewees' notions of class was that the rich do not earn their money honestly and routinely cheat and deceive, particularly government ministers and Knesset members. This was prominent also in Neta's response to whether Knesset members are rich: “Thieves! They steal from the pockets of the common people. This is why they are rich.” Rina was similarly adamant that government ministers—whom she categorically asserted to be rich—acquire their wealth by stealing, as opposed to the poor, who only take benefits illegally due to their state of need:

I think it is outrageous that they steal millions and millions, and nobody says anything … If only our country's problem was the NIS 2,600 [a month] that Shiri takes [in benefits she is not strictly entitled to receive], that I take, that she [Nira] takes. If only … They exploit the system in the millions.

Daniella's comments are illustrative of the association interviewees make between government, corruption, and wealth:

The big government ministers are also frauds. They also steal … Every day you hear about another minister being investigated by the police for fraud in the millions. You teach me to steal!

An interesting finding that emerged from the interviews is a high correlation between the level of interviewees' class awareness and their level of resistance to the Israeli welfare state. Those women who displayed a low level of resistance did not express any notions of class, whereas those who indicated a high level of resistance tended to express strong class awareness (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Correlation between Class Awareness and Level of Resistance.

As the graph illustrates, 100 percent of the women who expressed no class awareness exhibited a low level of resistance. Of the women who articulated a medium level of class awareness, 73 percent exhibited a medium level of resistance, while 27 percent manifested a low level of resistance. Of those with a high level of class awareness, 78 percent expressed a high level of resistance, and 22 percent a medium level of resistance.

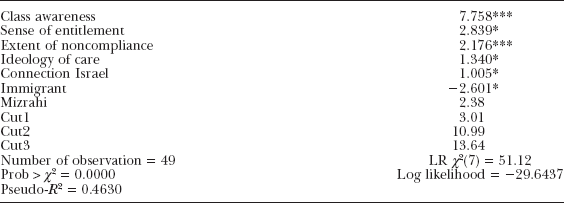

To further explore the relationship between level of resistance and class awareness and to control for the effects of other variables (such as sense of entitlement and ethnicity) on the level of resistance, I conducted a statistical analysis. Table 1 presents the results of an ordinal regression model predicting level of resistance. The analysis showed class awareness to be the most important predictor of resistance level (p < .01):Footnote 9 the greater an interviewee's awareness of class relations, the higher the likelihood that she would manifest a high level of resistance. A greater sense of belonging in Israeli society, stronger sense of entitlement, and higher extent of noncompliance, all had a significant positive effect on level of resistance (p < .01). Being an immigrant, in contrast, had a negative significant effect on level of resistance; Mizrahi ethnic origin, the size of the interviewee's city, and geographic location (periphery or central Israel) had no statistically significant effect on level of resistance.

Table 1. Results of Ordinal Logistic Regression Models Predicting the Level of Resistance

Notes: *p < .1; ***p < .01.

The data from my interviews strongly imply that in the Israeli context, class awareness—as it manifested in the interviews—is a crucial variable in the emergence of high-level resistance. The correlation between class awareness and high levels of resistance in my findings is unusual and intriguing, contradicting a common premise (Reference Shafir and PeledShafir and Peled 2002) that class awareness in Israel is very weak due to the national conflict between the Israeli state and Palestinians and the internal ethnic conflict between Mizrahi and Ashkenazi Jews. The fact that class awareness seems to be essential to the development of high-level resistance in the Israeli context raises the question of why such awareness arises in some cases and not others. The data from the interviews suggest a few possibilities that are worth noting. First, of the 14 interviewees who had emigrated from the Former Soviet Union (FSU) in the previous two decades, only two showed evidence of a strong sense of class awareness, which is significant given their upbringing in a communist regime. One possible explanation for this minimal extent of class awareness might be rooted in the fact that in the USSR, these women had perceived themselves as having a high socioeconomic status. Accordingly, many of them referred to their lives there in the context of their socioeconomic decline after immigrating to Israel. A similar phenomenon, where a sudden downward shift in socioeconomic status hindered the emergence of class awareness, also presented with interviewees who were native-born Israelis: Interviewees who had experienced a decline in socioeconomic status (usually due to divorce or becoming a single mother) also showed a lack of class awareness. In some cases, this seemed to correlate with a strong general belief in social mobility. While most apparent among interviewees who had immigrated from the FSU, it was also true, albeit to a lesser extent, for two native-born Israeli women, with both groups stressing the financial prosperity they foresee for their children.

My sample also included native-born Israelis whose families had been poor for two or three generations, who, precisely because they had lived all their lives in poverty (have never worked outside the home or had any actual contact or acquaintanceship with “the rich”), seemed to lack any class awareness. My findings thus point to a need for deeper inquiry into the possible variables that might account for the development of class awareness among the poor, particularly changes in socioeconomic status, perceptions of social mobility, and forms of class isolation.

In summary, it emerges that those women who exhibited high levels of resistance also tended to indicate a broader class-based perspective. High-level resistance—which is framed as a political act—seems to have the most potential of escalating and generating social change. However, only 7 of the 49 women interviewed exhibited such class awareness and high-level resistance; thus, as a general phenomenon across the entire sample of interviewees, there was only a weak overall connection between their individual acts of resistance and any broader ideological perspective.

Social Support System

In this section, I analyze the social system, in terms of its practices and norms, that supports the individual acts of resistance engaged in by the interviewees in my study. My claim is that their fraudulent behavior is partially organized through the practices of passing-on and retelling stories of noncompliance, as well as through the provision of advice and concrete assistance on how to defraud the welfare authorities. These practices are bolstered by strong social norms against informing on others and that endorse helping others to defraud the system.

(1) Collective Practices

(a) Passing-On Stories of Noncompliance

All of the women interviewed recounted stories about other people's noncompliance with the welfare laws. In some cases, these were people they knew personally; in other cases, they had heard the stories from friends, acquaintances, or even strangers. These stories could not be verified for accuracy, of course, and many might be simply myths that have circulated among welfare recipients. What was evident and relevant, however, was that from the interviewees' perspective, these stories are undeniable fact.

The noncompliance stories were told in different contexts. While they can serve a diversity of functions (Reference Herrnstein SmithHerrnstein Smith 1980), they seem principally to have an internally conflicting ideological function and to operate as a mechanism for circulating information among the collective members.Footnote 10

Ideological Function of Telling Stories of Noncompliance

There is extensive literature on the role of stories and narratives in supporting ideology, forming identities, and enabling collective ties and group action (Reference Ewick and SilbeyEwick and Silbey 1995, Reference Ewick and Silbey2003; Reference FineFine 1992; Reference Ganz, Odugbemi and LeeGanz 2011; Reference Mische, Diani and McAdamMische 2003; Reference Ochs and CappsOchs and Capps 2009; Reference PollettaPolletta 1998). Reference Ganz, Odugbemi and LeeGanz (2011) argues that storytelling is a crucial tool of mobilization, as it is the discursive form through which we translate our values into a motivation to act. By evoking emotions in ourselves, stories cause us to experience the things we value and answer the question of why we must risk taking action. Through the recounting of a challenge, a choice, and an outcome, stories teach us how to act in the “right” way. Narratives enable us to experience the moral of the story and feel hope or despair; “it is that experience, and not the words as such, that can move us to action” (282).

During the interviews, the women who themselves had engaged in welfare fraud most often began with their own stories of noncompliance, what Reference Ganz, Odugbemi and LeeGanz (2011) terms their “self story.” Reference Ewick and SilbeyEwick and Silbey (2003) see this process of transforming the act of resistance into a story of resistance as a means of extending the social consequences of resistance: “a story that by its telling extends temporally and socially what might otherwise be a discrete or ephemeral victory” (1345). However, it is uncertain to what extent these “self-stories” have been told by the women outside the confines of the interview, and therefore, their role in constructing a sense of collectivity for them unknown. However, two types of less-personal noncompliance stories that circulate among welfare recipients emerged from the interviews. These stories are passed around, retold, and interwoven, narrating noncompliance as either a tale of survival or a tale of being disclosed to the authorities. Generally, the protagonist is a simple, hard-working woman who does intermittent cleaning work and, therefore, requires sporadic financial assistance from a man, who generally fails to provide this, and she does her best to follow the law despite her intolerable conditions. The story usually ends with the poor, desperate, but still honest woman being investigated by the welfare authorities, placed under surveillance, caught defrauding the system, and then left destitute once stripped of her paltry benefits.

This narrative plays a dual, conflicting ideological role: on the one hand, it mobilizes and creates a collective group identity, while, on the other hand, it fragmentizes that very same group and creates despair among its members. The power of this narrative lies in its ambiguity, which provokes the telling of more stories (Reference PollettaPolletta 1998): The absence of a clear logical explanation for the described events seems to instigate the continuous dissemination of these tales of inexplicable injustices that generate emotions that motivate people to take action. At the same, the seemingly inevitable disclosure to the authorities and the devastating outcome evoke a sense of despair in the women.

The recounting of noncompliance narratives also serves to establish the women's membership in a collective, which is a particularly important factor in the mobilization that occurs before an organized social movement is consolidated (Reference PollettaPolletta 1998). Repeating such stories and myths—regardless of whether they have any real grounding in reality—fosters for each woman the sense that she is not alone in the circumstances forcing her to engage in fraud. This sense of belonging to a collective enables women to talk relatively openly about their acts of fraud and to both solicit and give advice.

Yet, the noncompliance stories also significantly blur the boundaries of the women's group identity. The interviewees did not directly link these stories to their class-oriented narratives nor give them any class context. Therefore, they did not articulate a clear notion of who is included and who is excluded from the collective. Only rarely did these narratives of noncompliance, in and of themselves, transform into a “story of us” that moves from a particular story about an individual to a shared collective crisis and points of interaction—such as the cuts in benefits during the welfare reform or general housing crisis (Reference Ganz, Odugbemi and LeeGanz 2011). Hence, although, as I have shown, my interviewees articulate a common political claim, the collective practice of passing-on stories of noncompliance fails to disseminate a story that generates the values that move women to act as a collective. The stories emphasize particularity, and by “effacing the connection between the particular and the general, they help sustain hegemony and not subvert power” (Reference Ewick and SilbeyEwick and Silbey 1995: 200).

Passing-on noncompliance stories thus amounts to a weak ideological tool in the context of my study, as it pulls in two opposing directions: it paradoxically connects and mobilizes women toward action while generating a sense of isolation and despair for them.

Disseminating Information

Some of the noncompliance stories are unmistakably used as a mechanism for passing-on information. Through these stories, the women learn and impart information as to what is and is not allowed, how the system works, and how to get around it. Misha, for example, described how she had overheard strangers talking on a bus about investigators who come to welfare recipients' homes checking for domestic partners. Natasha had heard from a cousin who lives in a different part of Israel about a friend who lost her benefits because investigators had found a man's electric shaver in her bathroom. Friends had told Lila that investigators look for men's clothing in closets; and Hava had heard that some women put the title of their car in someone else's name. Numerous stories of this sort were recounted throughout the interviews. The women were well-versed in the welfare rules, although had almost never got their information from the NII itself. From such stories, the women had learned not only about the formal welfare rules and regulations but also about the actual ways in which the authorities enforce the rules in practice, what evidence they look for when investigating fraud, and what a recipient should and should not reveal when being investigated. Thus, some of the stories have informed the women about what to be cautious of and how to more effectively outsmart the system.

(b) Giving Advice and Concrete Assistance in Defrauding the Welfare System

The second major collective practice that emerged as part of the women's system of social support is the provision of advice and assistance in evading detection and in cheating the system. For example, Rina forged a brief bond of resistance with someone she barely knew whom she had bumped into on the street. She recounted how the woman had advised her:

You are a fool. You must go to the doctor and say that you suffer from anxiety, that you don't sleep at night. Go. You'll see that they [the welfare authorities] will give you everything [all the benefits].

Sigalit described how a friend had warned her that NII investigators were making raids on recipients' homes throughout the city, and Einat recounted a similar experience of being warned about home raids. Nina stated that she had advised a friend to conceal the fact that she was living with her partner because otherwise the welfare authorities would stop her benefits. Lila said she was advised by complete strangers to remove any jewelry before she goes to the NII offices. Several interviewees mentioned that acquaintances and friends had advised them to work without reporting the income. Adi recounted how just the previous week, she had given advice to a complete stranger waiting in line with her at the employment bureau, after the woman had complained to her that the bureau administrator keeps sending her out to jobs even though she has four children:

I said to her, ‘Do you have any medical documents that say you have some problem? There is nothing else that can save you! Be sick!’

Adi explained, “I have two kids, and I understand that it is hard. She doesn't even need to explain to me. She has four [kids].” This exemplifies how these women informally cooperate by providing advice on how to get around the system.

In addition, some of the interviewees also described giving concrete help to others in committing fraud. For example, Lara intentionally lied to NII investigators for her neighbor, stating that the latter lives by herself when she knew the woman was residing with the father of her newborn baby. Another interviewee, Sveta, told how she had actively lied to the welfare authorities that her friend lives with her, so as to help conceal the friend's fraud. As a result, Sveta's benefits were reduced due the extra income she is supposedly receiving from rent, but her friend pays her the difference every month. Similarly, Nitza illegally connected a family that she did not know personally to the city water supply. She expressed a deep sense of solidarity in taking this action, willing to engage in illegal activity on a stranger's behalf and risk the consequences:

[I decided] I am going to [illegally] connect that family to [the city] water … I couldn't bear the thought of an entire family without water … The woman was apparently scared of this … I told her not to be scared. She said to me, ‘What if they come?’ I wrote down my phone number for her and told her that she can give them my number, say I did it, and if they want, they can call me.

(2) Social Norms

The women's social support system promotes the described practices through strong social norms that ostracize informants and encourage helping others to conceal fraudulent acts. Informants arose as a major theme in many of the interviews; a number of the women mentioned the prevalence of informants, and any discovery of fraud by the authorities was automatically attributed to informants. As I detail below, the fear of being informed on plays a major role in the women's tendency to keep their distance from their neighbors.

There are strict social norms among the women against tipping off the welfare authorities about fraud, and the idea of informing was almost unanimously denounced by my interviewees. Informants were described as evil and narrow-minded, and the women rejected any justification for collaborating with the authorities. Accordingly, 47 of the 49 interviewees said that they would never inform the NII about fraudulent acts, even if they were certain that the person was engaging in what they consider unjustified fraud. For example, Neta talked about a neighbor who engages in what she deems unacceptable fraud, defining the acts as theft. Nonetheless, when I asked what she would do were an investigator to knock on her door and ask about the neighbor, she articulated and affirmed the strong social norms that vilify informants:

If an investigator comes and asks? I'll say nothing. There is no redemption for informants. […] No way. I won't tell on anyone. I know many like that [who defraud the system]. I wouldn't want anyone to inform on me. That is a fundamental.

This principle held up even when an interviewee indicated clear resentment toward people who defraud the system unjustifiably. For example, Eti talked at length about a woman with a successful business, new car, and designer clothes who still receives welfare benefits. She clearly resents her and believes that because of these kinds of fraudulent acts, all welfare recipients are treated like swindlers. She feels it is extremely unfair that she has endured several investigations and frequent surveillance while the wealthy welfare recipient has remained untouched. But when asked by a welfare investigator for the names of people she knows to be defrauding the system, she refused, with disgust, even though the investigator had intimated that it could be to her advantage. Similarly, even when Esther was told by welfare investigators that members of her own family had reported that she lives with her partner, she refused to retaliate and provide information on them. She explained that she would never do such a thing: “I will not take the bread out of any child's mouth.”

In general, it seems that the social norms against informing are so strong that it is very difficult to discover the identities of informants. Thus, in most cases, the women never find out who informed on them, and there are usually no accompanying social repercussions for informants. Nonetheless, the potency of these social norms suggests that the women believe that informants can face harsh social sanctions. Hanna explicitly expressed such a conception of potential social consequences, stating that she would never inform on a neighbor because

I know it would cost me dearly … Sometimes, you know, there is revenge. […] I'm not looking for any trouble. I have enough problems of my own.

Daniella expressed a similar fear of social sanction, stating that she would never tell a welfare investigator where someone being investigated lives because she is afraid of the consequences: “If I tell him, here, she lives here, afterwards they'll say that I told. What do I need that for? So I don't do it.” One interviewee in fact reported identifying a woman from her support group whom she suspected of informing the welfare authorities that the interviewee's partner was living with her. As a result, the woman was immediately ostracized by the group.Footnote 11

In summary, it seems that the women's involvement in welfare fraud is, to some extent, organized and supported by the practices of passing-on noncompliance stories and providing advice on how to beat the system, as well as guided by clear social norms with respect to informing on others to the authorities. It emerges from their narratives that most of the women's acts of noncompliance or experiences with noncompliance with welfare laws are connected at a collective level through this system of organization. These findings suggest that their acts are not merely individualistic and personal in nature, but rather supported to a significant extent by collective practices and norms. Yet, as I elaborate below, this amounts to only a very limited form of collectivity due to the power dynamics that shape and impact the practice of welfare fraud.

A Constrained System of Social Support

My claim is that the power dynamics within which welfare fraud plays out—manifested in the fear of disclosure—produce a remote and narrow system of social support for the women engaging in fraud. Accordingly, although it emerged in the interviews that the women in my study maintain a system of support and help others to defraud, this takes a constricted and constrained form. My findings showed that the women are supportive of acts of fraud in only two distinct contexts: when they are among close family or close friends and, to a more limited degree, when they are with acquaintances or complete strangers. Within their small circle of friends and family, the women feel safe to completely share and support others in their fraudulent acts; with acquaintances and strangers, the women provide support, even if only to the point of not putting their own benefits at risk. Yet, in contrast, they indicated that they intentionally detach and isolate themselves from their immediate environment, which should be their natural community and system of support.

Setting out on this research, I began with what emerged to be a naive expectation of finding a very close-knit and supportive community of welfare recipients in the poorer neighborhoods. I envisioned a community similar in structure and form to how Carol Stack describes urban American black families in the mid-1960s, based on a “cooperative lifestyle built upon exchange and reciprocity” (Reference StackStack 2013: 125). I was looking for patterns of interdependence, rich, and vibrant exchange networks linking multiple domestic units, and lifelong bonds extending beyond the traditional nuclear family (Reference StackStack 2013). The reality I found, however, was very much otherwise. Only nine of the women interviewed reported good relations with their neighbors and that the latter provide them with support. More often than not, instead of as a source of mutual support, neighbors were viewed by the interviewees with suspicion and fear. Almost all expressed the prevailing view, in the context of informants, that one should not trust one's neighbors. Hence, many of the interviewees (22) described a reality in which they purposely distance themselves from their neighbors to protect themselves from exposure. For example, Natasha, an FSU immigrant, intentionally isolates herself from her neighbors due to an incident with a neighbor, whom she believes informed on her to the authorities following a dispute they had over parking. When I inquired about her relations with her neighbors and whether she is on friendly terms with them, she answered,

I know them. But I try as little as possible. Because from the first day that I came here … I understood that everybody snoops … [They ask,] what does she live on? Who does she live with? What does she do?

The NII's practice of taking fraud investigations into the recipients' homes and its extensive resort to informants play an important role in fostering this suspicion and isolation. The impact of these practices is intensified through the passing-on and retelling of stories of being exposed to the authorities by neighbors and informants. These exposure stories fragmentize the collective of women into isolated individuals. Sarah recounted that when she came to the NII to notify them about her pregnancy, the clerk said to her cryptically, “Good of you to come. They already told us you are pregnant.” Sarah explained, “They have informants.” At a later point in the interview, she told of another such incident, in which she spoke to a neighbor about welfare benefits and the next day investigators showed up at her home. “Naturally I immediately suspected her [of being an informant].” Nili told the story of a woman she knew from work who did housecleaning and did not report the income to the welfare authorities. After the woman got into a fight with a friend, the friend informed the NII about the woman's undeclared income. Nili described the woman informed on as completely downtrodden, saying “people sometimes have no heart.” Zahava had a similar story about a woman disentitled to her welfare benefits when a neighbor, after a quarrel, informed the welfare authorities that the woman lives with her ex-husband. Zahava noted that the woman was disentitled despite her extreme poverty and left with no means to provide for her six children. Thus, Zahava explained, she deliberately stays away from her neighbors, since “neighbors can easily give you away, intentionally or inadvertently.” Tamara, for her part, even though never having heard a concrete story about a woman losing her benefits due to being informed on, described how she deliberately cuts herself off from her neighbors to avoid any possible trouble with the welfare authorities:

I have no contact with neighbors. I don't want to mix with the neighbors. [Because] then they [the welfare authorities] will investigate, ask questions.

Hence, the women's social support system is impacted substantially by the potential of NII inspections at their homes and being informed on and leads them—fearing exposure—to severely restrict their contact and relations with neighbors and to avoid being part of a close local community. The women's acts of resistance and their ability to organize are thus fragmentized by the overwhelming power of the Israeli welfare state.

As described, however, the women do assist and receive support from random acquaintances and total strangers. The role strangers play in the support system attests to the existence of a collective among the women, but it is also evidence of its limitations. This complex role is most remarkably apparent in the NII waiting room. It seems that the women feel especially open to helping others in this setting, as they know that the people waiting in line are in similar circumstances, and they have little fear of their fraudulent behavior being exposed and their benefits placed at risk. The fear of being exposed to the authorities thus forges trust between remote individuals and distrust between close or more intimately involved individuals. Accordingly, several interviewees specifically noted that the NII waiting room is their best source of invaluable information. Some acquired information from simply sitting and overhearing stories being told in the small and often very crowded waiting area. Others reported that some women ask directly for advice and information while waiting. Nili recalled how, while she was waiting in line at the welfare bureau, a total stranger had advised her not to tell the welfare authorities if she had been working. Her narrative sheds light on the power dynamics that shape the development of this remote form of support:

If this had been someone I know personally, maybe she would have been afraid to come and say that. But if I randomly see someone—she doesn't know me and I don't know her—she comes and tells me what she thinks and that's that. What, am I going to go look for her to inform on her?

Yet, such a system of social support is inescapably constricted. The women's detachment from their neighbors cuts them off from a significant pool of people who might be better positioned to provide support than strangers due to their physical proximity and their probably similar socioeconomic circumstances. The support provided by family and friends is inevitably limited because of their limited numbers. The support strangers can provide consists only of stories and advice, as opposed to concrete assistance, such as help in covering up fraud or material or financial help when fraud is disclosed and the women disentitled. The support derived from advice from strangers is necessarily brief and very narrow in scope, as the women must be vague and refrain from disclosing any incriminating details. Finally and significantly, the absence of support from neighbors erodes and weakens the women's sense of belonging to a collective and impedes their solidarity tremendously.

In summary, I have shown that the fraudulent acts that the interviewees engage in are partially maintained through a limited system of social support. My analysis suggests that the women's acts of welfare fraud do not represent mere acts of individual noncompliance but collective resistance. However, the form of assistance provided by their social support system reflects the power constellation that shapes the scope and form of the resistance: the women's feeble, relatively voiceless position versus the powerful state. In other words, the fact of a connection between the individual fraudulent acts and a form of collectivity implies the potential of these individualized, unrelated acts as a force of social change. Yet, at the same time, the women's intentional disconnection from their neighbors and immediate and close environment exposes the collective's structural vulnerability; this leads to the women's social isolation and prevents them from constructing community systems of support and transforming their resistance into political or social reform.

Conclusions

In this paper, I have shown women's noncompliance with the welfare laws and authorities to be a limited form of collective resistance. Although the fraudulent acts that the interviewees in my study engaged in entail a political claim against the Israeli welfare state, the relationship between the fraud and notions of collectivity takes a very constrained form. I have shown that the women's political claim is not grounded on a comprehensive ideological perspective regarding gender relations and the patriarchal social order. Moreover, only a minority of the interviewees expressed a class-based claim that transcends their concrete political claim of entitlement to benefits. In addition, I demonstrated that the individual acts of fraud are somewhat connected through a system of social support that includes collective practices of passing-on and retelling stories of noncompliance and informally disseminating advice about how to beat the system. These practices are promoted and supported by forceful social norms regarding informants. Yet, we saw that this system of support is constrained by the welfare authorities' invasive and pervasive investigation practices and methods. Fearing disclosure to the authorities, the women emerged as deliberately isolating themselves from their immediate environment and potential, like-situated members of their collective. This weakens the connection between the women's acts of resistance and their collectivity. It prevents these acts of resistance, of noncompliance, from driving social change and traps the women in their harsh conditions and existence: isolated in their deep poverty; devoid of resources; and pushed to the margins of society. Perpetually running on a treadmill of individual acts of resistance, they live under the illusion that this movement will lead to something: the very engagement in resistance produces in them the sense that they are fighting the system. Even though these acts seem unlikely to have any potential for promoting broad social change, the women feel that they are engaged in a struggle against the system. It is this illusion that prevents them from truly resisting and fighting the system and allows the system to continue to operate and function without hindrance. Thus, not only do the women's acts of protest fail to challenge and transform the existing hegemonic order, they actually legitimize it, stabilizing rather than challenging it.

The findings in my study raise a number of possible directions for further inquiry into the variables impacting the different levels of resistance that emerge. To begin with, there is a need to explore the conditions contributing to the development of class awareness. Second, this study calls for further investigation of the relationship between female welfare recipients' sense of entitlement to state support and their level of resistance, particularly a refinement of the conceptualization and measurement of this “sense of entitlement” to account for variances. The distinction I made between weaker and stronger senses of entitlement based on notions of gratitude seems too crude and does not encompass the complexities of the women's sense of entitlement. Third, further inquiry should clarify any correlation between the women's resistance and the extent to which they feel connected to the Israeli nation-state. This study suggests a counterintuitive relationship between these two variables: Women with a greater sense of connection and social integration exhibited a higher level of resistance, whereas women who feel disconnected from Israeli society exhibited lower levels of resistance or no resistance at all. Thus, there is a need for deeper exploration of Israeli female welfare recipients' sense of connection to their society and country in order to better assess and measure this variable. This could be achieved through a systematic examination of female welfare recipients' involvement in Israeli society based on the extent to which they watch the news and participate in elections, their conceptions of mandatory military service and volunteer work, their willingness to emigrate from Israel, etc. An interesting theoretical framework that could be applied in exploring these issues is Reference HirschmanHirschman's (1970) notions of the relationship between “exit,” “voice,” and “loyalty” (Reference HirschmanHirschman 1970). Do acts of fraud constitute “voice” or “exit”? If fraud is a means of “exit,” then what is its relationship with different means of “voice” or with forms of “loyalty”?

Moreover, there was some evidence in my findings of a few additional variables in the emergence of resistance, which also warrant further exploration.Footnote 12 First is whether there is any relationship between the extent to which the women express confidence in conventional political processes and institutions and the level of their resistance. For instance, what is the relationship between voting in elections and engaging in acts of resistance or between a woman's perception of collective action and her level of resistance? Anecdotal evidence suggested that a lack of faith in the political processes—in individualistic modes of action (such as voting) in particular—might explain the emergence of higher levels of resistance. In addition, the data suggested that a broader notion of the efficacy of taking action—how the women perceive their ability to instigate change—should also be explored. In particular, it would be interesting to examine the relationship among resistance, formal inefficacy, and informal efficacy. On the one hand, the women tended to be skeptical about the likelihood of effecting change through the formal political institutions and processes; yet, on the other hand, they indicated a belief that almost anything is possible through informal channels and means of action.

This paper sheds important light on the particular phenomenon of welfare fraud in Israel as well as on the general conception of individual acts of noncompliance as a form of collective struggle. Focusing on the link between the individual fraudulent acts of female welfare recipients and collective struggles exposes the potential—and, even more compellingly, limitations—of such individual acts to initiate and drive change. This paper illustrates that the power dynamics that give rise to this form of resistance also prevent this resistance from evolving into a legitimate public movement for change. The analysis here therefore offers an alternative exploration and understanding of welfare fraud: instead of how to eliminate and combat this phenomenon, the paper considers the circumstances and conditions necessary for such a form of resistance to transform into open and legitimate public protest against the social order.