Introduction

The causes of early childhood undernutrition in low-income and middle-income countries are complex and poorly understood, and may not merely be a consequence of nutritional inadequacy (Roth et al., Reference Roth, Krishna, Leung, Shi, Bassani and Barros2017). Macro level social and environmental conditions, maternal characteristics, but also parental investment may be reflected in measures of child nutrition (Costa et al., Reference Costa, Trumble, Kaplan and Gurven2018; Leroy & Frongillo, Reference Leroy and Frongillo2019). Parental investment decisions reflect readiness and ability to invest in a particular child: parents may invest in their children in many ways, but some children may be less invested in than others (Quinlan, Reference Quinlan2007). Investment decisions are usually determined by a number of maternal factors, e.g. age, ethnicity, birth spacing, family size, resource availability, but also child characteristics, such as quality and wantedness (Sparks, Reference Sparks2011; Lynch & Brooks, Reference Lynch and Brooks2013). Childbearing intentions are determined based on wantedness: births resulting from unwanted childbearing are the result of unintended pregnancies, further classified as unwanted pregnancies (occurring when no more children were wanted) or mistimed pregnancies (occurring at a different time than desired) (Santelli et al., Reference Santelli, Rochat, Hatfield-Timajchy, Gilbert, Curtis and Cabral2003). Unwanted childbearing is an important public health problem, associated with adverse maternal behavior during pregnancy and poor perinatal outcomes such as low birth weight (defined as birth weight less than 2500 gr) and infant mortality (Shah et al., Reference Shah, Balkhair, Ohlsson, Beyene, Scott and Frick2011; but see Joyce et al., Reference Joyce, Kaestner and Korenman2000). In low- and middle-income countries, research on the relationships between pregnancy intentions and child outcomes is limited, and the findings have been mixed (Hall et al., Reference Hall, Benton, Copas and Stephenson2017; Hajizadeh & Nghiem, Reference Hajizadeh and Nghiem2020; Marston & Cleland, Reference Marston and Cleland2003). Analyses of unintended pregnancy usually combine unwanted with mistimed pregnancies even though they measure different dimensions of pregnancy intention and usually reflect very different individual and social conditions (D’Angelo et al., Reference D’Angelo, Gilbert, Rochat, Santelli and Herold2004; Klerman, Reference Klerman2000; Luker, Reference Luker1999). Very little is known about unwanted births and the context in which they occur (Kost & Lindberg, Reference Kost and Lindberg2015). Aggregating unwanted births, i.e., unwanted with mistimed children, during analysis, may undermine differential determinants and effects on child nutritional outcomes.

In a high fertility context the relationship between parental investment, unwanted births and child nutritional outcomes is not well understood, as a high-risk, resource poor environment may result in reduced parental effort overall (Hrdy, Reference Hrdy1999). The implications may be especially relevant for children coming from the most disadvantaged backgrounds and at increased risk of nutritional deprivation. To address this aspect, this study aimed to assess the association between maternal investment, unwanted births disaggregated into mistimed and unwanted children, and child nutritional outcomes in a poor population of Serbian Roma.

The Roma, a diverse population of South Asian origin, are the largest ethnic minority in Europe, experiencing severe social exclusion, poverty, welfare dependency, poor health, and higher levels of fertility, child mortality and low offspring birthweight rates than observed in other ethnic groups or majority populations (Balázs et al., Reference Balázs, Rákóczi, Fogarasi-Grenczer and Foley2014). Roma women living in Serbia lack education, the skills for and access to jobs, and have cultural practices that seem to limit women’s choices (Čvorović & Coe, Reference Čvorović and Coe2017). Typically, Roma girls enter traditionally arranged marriage and motherhood as teenagers while high fertility is culturally encouraged (Čvorović, Reference Čvorović2014). The majority of Roma children are growing up in poverty, suffering from relatively high rates of undernutrition indicated/ by stunting (i.e., low height for age), wasting (i.e., low weight for height), underweight (low weight-for-age) and developmental delays (UNICEF 2020). Roma children nutritional status is usually explained by the social determinants of health but there are some health differentials among Roma children themselves suggesting that some children are especially vulnerable (Janević et al., Reference Janević, Osypuk, Stojanovski, Janković, Gundersen and Rogers2017). Previous study found that the relationship between child wantedness and Roma mothers’ parental investment is not straightforward (Čvorović, Reference Čvorović2020). Thus, base level investments such as breastfeeding varied with birthweight and child wantedness, while wanted children had higher odds of being fully vaccinated than unwanted children. At the same time, mothers boosted their investment in children with low birthweight, while surplus investment varied with access to resources. Among mothers living in traditional societies, cultural pressure and gender expectations may frequently result in unwanted births being rationalized as to include “the excess” births, and it may thus appear that even children who were wanted suffer from reduced parental investment (Costa et al., Reference Costa, Trumble, Kaplan and Gurven2018). Despite this variance, to date, no research has directly assessed the association between variability in Roma maternal investment, unwanted births, i.e., mistimed and unwanted children, and child nutritional status.

Data from the Serbian Roma national dataset (Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey rounds 5 and 6/MICS 5 and 6) were used to assess the association between maternal investment and unwanted births disaggregated into mistimed and unwanted children, and child nutritional measures, reflected in height-for-age z-score (HAZ), weight-for-age z score (WAZ) and weight-for- height z-score (WHZ).

Method

The present study was performed as a secondary data analysis of the UNICEF MICS 5 and 6 for Roma communities, a public use data set, conducted in Serbia in 2014 and 2019 (available at http://mics.unicef.org/surveys). Details regarding the surveys methodology can be found elsewhere (UNICEF 2015). MICS capture both anthropometric and early child development data along with basic information on mothers, caregiving practices for young children, and household wealth. The surveys include a specific series of measures that capture several domains of child development and growth, reported by Roma mothers. Mothers with singleton birth in the past two years prior to the surveys, in a marriage/union were included in the study. Data on pregnancy intention was available for children aged 0-24 months and 1173 Roma mothers.

Weight at birth and maternal parity were used as proxies for parental investment. Maternal investment begins in utero and lower birth weight is one of the main indicators of lower maternal investment during pregnancy (Coall & Chisholm, Reference Coall and Chisholm2003). Low birth weight may represent a potential risk factor for growth outcomes but limited studies have examined the differentials of childhood nutrition across the birth weight status (Ntenda, Reference Ntenda2019). Weight at birth was available for 126 Roma children, obtained from health cards, health facilities and mothers’ recall.

Maternal parity reflects a fundamental trade-off between number and size of offspring, influencing the differentials in parental investment across and within species (Walker et al., Reference Walker, Gurven, Burger and Hamilton2008). Parity was available for 130 Roma women.

Whether a pregnancy was wanted with a particular child was determined based on the wantedness status: wanted or not wanted a child at that exact time; mothers who reported unwanted pregnancies were further asked whether they wanted a baby later on (mistimed pregnancy, i.e., mistimed children) or they did not want (any) more children (unwanted children). There were 130 unwanted births/pregnancies, disaggregated into mistimed and unwanted.

Additional variables were used to account for maternal and child conditions, based on the existing literature (Čvorović & Coe, Reference Čvorović and Coe2017). Whether a mother (N = 130) ever had a child who later died was used as a proxy for child mortality. Maternal age (N = 130) at the time of the survey, literacy skills (can read the whole sentence/basic literacy or can read only part of the sentence/functionally illiterate (N = 120), and household access to improved toilet facility (N = 130), were used as proxies for socioeconomic status. Many Roma women are illiterate or functionally illiterate, therefore, literacy skills were divided into two categories: those that can read the whole sentence/basic literacy skills or can read only part of the sentence/functionally illiterate. Poor sanitation/open defecation is closely associated with low SES, influencing early-life health, as environmental contamination may increase disease and reduce nutrient absorption, leading to deficits in height and weight (Hammer & Spears, Reference Hammer and Spears2016).

Child’s variables included age in months (N = 130) and gender (N = 130), to account for variation between younger and older children, and boys and girls in nutritional status, and child’s birth order (N = 130).

Nutritional status in children is usually expressed in terms of z-scores based on WHO’s reference population. Outcome variables were individual-level HAZ (N = 121), WAZ (N = 125) and WHZ (N = 122) children’s scores in standard deviations. Deficit in HAZ, when a child is short for his/her age may lead to chronic malnutrition with long-term developmental risks (de Onis & Branca, Reference De Onis and Branca2016). WAZ or under-weight refers to low weight-for-age, when a child can be either thin or short for his/her age, a combination of chronic and acute malnutrition. WHZ refers to low weight-for-height where a child is thin for his/her height but not necessarily short, known as acute malnutrition, carrying an increased risk of morbidity and mortality.

Descriptive statistics and Chi-square with Yates’ Correction for Continuity, Fisher and t-tests were used to describe and detect differences across variables based on Roma mother’s unintended pregnancies (mistimed and unwanted pregnancy).

Three separate hierarchical multiple regressions were conducted, correcting for the influence of several independent variables. In all models, controlled variables were mother’s age (continuous), literacy (dichotomous: 1-literate, 0-illiterate), type of toilet facility (0 -unimproved and 1-improved toilet facility), child’s gender (0-female and 1- male), birth order (1-10), and child’s age in months (continuous). Predictor variables were child’s weight at birth (dichotomous 1 >2500gr normal birth weight and 0 ≤2500gr low birth weight)), whether the child was unwanted or mistimed (0-unwanted and 1-mistimed), parity (≤3 and >3 children), and child mortality (dichotomous: 1-yes, 0- no). Dependent variables were individual-level HAZ, WAZ and WHZ scores in standard deviations, based on WHO growth standards. Controlled variables were entered into the model in the first step, followed by the predictor variables in the second.

For the sake of comparison, HAZ, WAZ and WHZ measures of wanted children were also presented.

Results

Unwanted pregnancy was reported by 11% of Roma mothers. Almost all unwanted children (98.2%) were born in a hospital. The majority of Roma women (95.7%) said they had used antenatal care, with an average of six visits during a particular pregnancy.

The Roma mothers who reported unwanted pregnancy were young, with an average age of 24 (SD = 5.95; range 13-41) (data not shown); in spite of the young age, the fertility was high, with four (SD = 2.06; range 1-10) children on average. Less than 10% of Roma mothers reported they had a child who later died, and only 8% never breastfed their child. Level of basic literacy for Roma mothers was low, while the majority of mothers (79%) lived in households with access to improved toilet facility. Out of those who used unimproved toilet facility (21%), 12% defecated in the open.

The average weight at birth for Roma unwanted/mistimed children was 3kg (SD = 0.51), while there were 17% of children born with low birth weight. Girls made up 55% of the sample; birth order ranged from first to tenth born (M = 3.52, SD = 2.06). Children were on average, 12 months old. Average HAZ was −1.15 (SD = 1.68; range −5.61-4.74), WAZ was −0.66 (SD = 1.31; range −5.17-2.59) and WHZ was 0.14 (SD = 1.51; range −3.60-4.33). For wanted children, average HAZ was −0.10 (N = 876, SD = 1.73), WHZ was 0.16 (N = 878, SD = 1.54), and WAZ was −0.42 (N = 946, SD = 1.32).

The majority of mothers with unintended pregnancy, or 54.6%, reported that the pregnancy was unwanted while 45.4% of mothers reported mistimed pregnancy. Additional differences in maternal socio-demographic and child’s nutritional measures based on disaggregated unwanted pregnancy/birth (mistimed and unwanted) are shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Maternal and child socio-demographic and nutritional measures distribution based on unintended pregnancy

*p=≤ 0.05; ** Chi-square with Yates’ Correction for Continuity; *** t-test; ****Fisher test.

Roma mothers who reported unwanted pregnancy were on average older (M = 27.37, SD = 5.37) than mothers who reported mistimed pregnancy (M = 19.71, SD = 3.36), and the difference was statistically significant (t (128) = 9.51, p<0.001, the effect size was large, η2 = 0.41). Roma mothers with unwanted pregnancy also had higher parity (M = 4.70.SD = 1.99) than mothers with mistimed pregnancy (M = 2.29, SD = 1.20, p<0.001) (not shown). When parity was divided into ≤3 and >3 children, the majority (69%) of mothers with unwanted pregnancy had more than three children while only one tenth of mothers who reported mistimed pregnancy had such, and this differences was statistically significant (χ2(1, 130) = 45.71, p<0.001) with the large effect size, ϕ = −0.59).

Differences in HAZ, WAZ and WHZ between wanted and unwanted (unwanted and mistimed) children were not significant (p = 0.36, size effect small. η2 = 0,001; p = 0.06. size effect small, η2 = 0,003; and p = 0.85, size effect small, η2 = 0,000, respectively).

Unwanted children, i.e., those born to mothers who reported unwanted pregnancy, were on average, shorter (HAZ M = −1.50, SD = 1.43) than mistimed children (M = −0.73, SD = 1.86) (t(119) = −2.58, p<0.001 but the effect size was small, η2 = 0.05).

Unwanted children had, on average, higher birth order (M = 4.62, SD = 1.99), i.e., they were later borns, on average, fifth, in comparison to mistimed children, on average second borns (M = 2.20, SD = 1.20) (t (128) = 8.54, p<0.001, and the effect size was large η2 = 0.36). Differences in child’s age and gender, weight at birth, WAZ and WHZ, maternal literacy, child mortality, and type of toilet facility were not statistically significant (p>0.05).

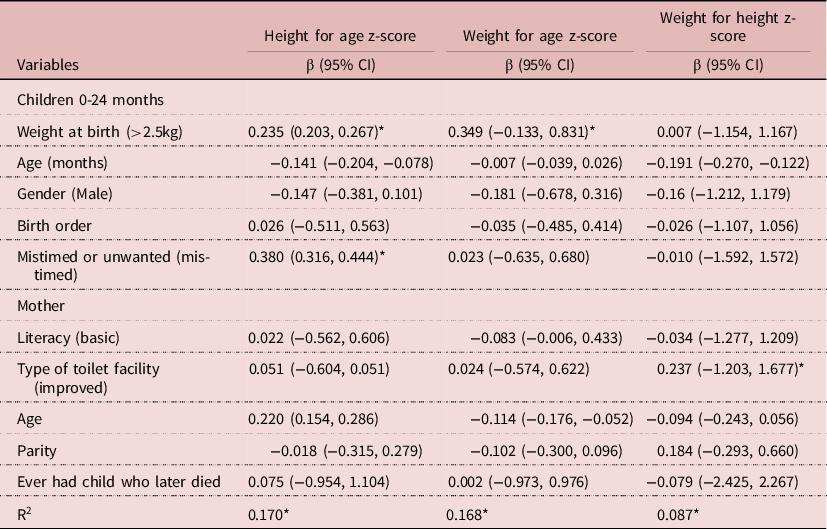

Table 2 shows predictors of Roma children’s individual level HAZ, WAZ, and WHZ scores in standard deviations.

Table 2. Predictors of Roma children individual level HAZ, WAZ and WHZ

*p=≤ 0.05.

Of the two measures of parental investment used in this study, weight at birth represented significant effects on Roma children’s HAZ and WAZ. Roma children born with normal birth weight (>2,5kg) were, on average, taller for 0.24 standard deviation in comparison to children born with low birth weight (≤2,5kg) (β = 0.24; p = 0.01, SD = 0.51), and were, on average, heavier for 0.34 standard deviation than their counterparts with low birth weight (β = 0.34; p<0.001, SD = 0.51). Furthermore, mistimed children were 0.38 standard deviation taller than children who were unwanted (β = 0.38; p<0.001) while children living in households with improved toilet facility were 0.24 standard deviation heavier than children living in homes without access to improved facility ((β = 0.24; p = 0.02).

Child’s age, gender, birth order, maternal age, literacy, parity and child mortality were not statistically significant in predicting Roma children HAZ, WAZ and WHZ scores (p>0.05).

Discussion

In high fertility, poor conditions, there has been a limited number of studies investigating the relationship between parental investment, unwanted births and child nutritional outcomes while direct comparison of unwanted births, i.e., unwanted with mistimed children in regard to child outcomes, has rarely being conducted (Hall et al., Reference Hall, Benton, Copas and Stephenson2017; Kost & Lindberg, Reference Kost and Lindberg2015). Hence, the present study assessed the relationship between two measures of maternal investment: weight at birth and parity, unwanted children disaggregated into mistimed and unwanted children, and children’s nutritional measures among poor population of Serbian Roma.

Overall, weight at birth had a significant effect on children’s nutritional status. After adjusting for potential confounding factors, the results indicate that children born with low weight at birth face a significant deficit in terms of their nutritional outcome, measured by child’s height for age and weight for age. The effect was aggravated for height if the child was unwanted (i.e., the mother reported having an unwanted pregnancy with the particular child). Birth weight reflects maternal size, reproductive strategy, and environmental limitations and it may be the most important determinant of subsequent growth status during infancy (Giudice et al., Reference Giudice, Gangestad, Kaplan and Buss2015). Low birth weight has been shown to be a significant predictor of lower adult stature suggesting that nutrition in utero is an important determinant of adult height (Black et al., Reference Black, Devereux and Salvanes2007). Across populations, the lower the birth weight, the greater the risk of mortality and morbidity (Class et al., Reference Class, Rickert, Lichtenstein and D’Onofrio2014).). Low birthweight may also influence maternal post-natal behaviors like infant feeding and care, contributing further to their children’s health disparities (Čvorović, Reference Čvorović2020). In contrast to other studies where growth penalties for unwanted children were not found, Roma unwanted children had significantly shorter stature (Baschieri et al., Reference Baschieri, Machiyama, Floyd, Dube, Molesworth, Chihana and Cleland2017; Costa et al., Reference Costa, Trumble, Kaplan and Gurven2018; Hajizadeh & Nghiem, Reference Hajizadeh and Nghiem2020). As height serves as an indicator of health and social environment in early life, for Roma children, being unwanted may be associated with worse health outcomes (Rahman et al., Reference Rahman, Howlader, Masud and Rahman2016).

Access to improved sanitation, as a proxy for socioeconomic status, benefited Roma children WHZ. Interestingly, average WHZ value was above zero, while both HAZ and WAZ had values below zero, suggesting that the majority of children may have been exposed to infectious diseases and parasites, with an impact on stature and weight (Scrimshaw, Reference Scrimshaw2007). Sanitation coverage, including access to improved toilet facility, improved in Roma communities in the past decade (UNICEF, 2015). Nevertheless, in this sample, the majority of households without access to improved toilet defecate openly and the differences in Roma children WHZ may arise from this alone (Chakrabarti et al., Reference Chakrabarti, Singh and Bruckner2020).

Differentiating between unwanted births revealed the importance of other maternal and child characteristics that may have influenced differences in Roma children outcomes. Parity, as a proxy for maternal investment, differed significantly between mothers who reported unintended births: it was significantly higher for mothers who reported unwanted pregnancy in comparison to mothers who reported mistimed pregnancy. In addition, Roma mothers who reported unwanted pregnancy were older than their counterparts. Generally, unwanted pregnancies are expected to occur at the end of a woman’s reproductive period and mistimed pregnancies more at the beginning (D’Angelo et al., Reference D’Angelo, Gilbert, Rochat, Santelli and Herold2004). The extent of parental investment may be influenced by maternal age, such that older mothers, with limited opportunities to bear an additional child, have higher odds of investment in a particular child than younger mothers, with a greater number of reproductive years ahead (Uggla & Mace, Reference Uggla and Mace2016)). In this sample, however, Roma mothers were on average, young, and it is likely that the significance of oldness simply reflects the strong effects of parity itself, as generally older mothers have higher parity due to an advantage of having a longer reproductive period (Čvorović & Coe, Reference Čvorović and Coe2017). Several years of age difference resulted in older Roma mothers, with unwanted children, having on average, 2.41 more children than Roma mothers with mistimed children, who were younger.

There were also important differences between Roma children. Height, a key indicator of health, significantly differed between mistimed and unwanted children, implying that unwanted children may face an additional nutritional burden due to their deficit in height. Unwanted children were also of higher birth order (later born) in comparison to mistimed children. Higher parity and birth order may explain the height differences found between the children: a number of related studies suggested an association between family size and child anthropometric status that possibly could predict future survival (Hagen et al., Reference Hagen, Barrett and Price2006). In life history, one of the life’s most fundamental trade-offs is between the number and size of offspring, or trade-off between offspring number and quality, usually measured as body size, resulting from the allocation of limited parental resources, especially under resource scarce conditions (Lawson & Mace, Reference Lawson and Mace2011). Furthermore, high parity itself may be an additional risk factor influencing child’s growth pattern as mothers who have had numerous children are more likely to have additional health concerns, which may negatively affect children’s outcomes (Jasienska, Reference Jasienska2017).

Birth order often shapes sibling differentials, especially in impoverished populations where children of higher birth order are disadvantaged in comparison with earlier borns in nutritional status, and may have higher morbidity and mortality (Lawson & Mace, Reference Lawson and Mace2008). In other studies, too, a fourth or succeeding pregnancy is likely to be unwanted and have an adverse outcome (Flower et al., Reference Flower, Shawe, Stephenson and Doyle2013; Mohllajee et al., Reference Mohllajee, Curtis, Morrow and Marchbanks2007). However, among the Roma, this association may not be straightforward, due to the intentional reduced investment by the mother. Among the poor, as the family increases in size, the shared food remains the same, thus later born children end up growing in more scarce conditions (Draper & Hames, Reference Draper and Hames2000). Food insecurity could be particularly important to Roma families, as they heavily depend on welfare and child help (Čvorović & Vojinović, Reference Čvorović and Vojinović2020). According to Serbian Law on Social Welfare, only the first four children in a family are entitled to social benefits: thus within a family on welfare, the first four born children “support” themselves and their families, while each additional child may be perceived as “surplus”, an additional cost and thus a burden. In this sample, coincidentally, the unwanted children were, on average, the fifth born. In contrast to other studies, “excess births” may have worked out to the disadvantage of Roma later born children (Perkins, Reference Perkins2016).

Studies have shown that nutritional outcome measures were positively correlated with health and development among children throughout the measures’ range, without cut off effect at –2 SD or any other cut-point (Sudfeld et al, Reference Sudfeld, McCoy, Danaei, Fink, Ezzati, Andrews and Fawzi2015). Many children in this sample, including wanted children may be at risk of undernutrition, as reflected in their HAZ and WAZ distributions (a mean HAZ and WAZ of less than 0), likely due to the resource-poor environment. However, Roma children who received lower maternal investment in utero, i.e., those born with low birth weight, unwanted and living in poorest households may face additional risk. Differences in maternal parity and child’s birth order between mistimed and unwanted children, reflected in height deficit of unwanted children, may present as further risk factors, as parental investment is likely to be diminished with each additional birth (Daly & Wilson, Reference Daly, Wilson, Hausfater and Hrdy1984).

The present study provided new evidence from the nationally representative dataset from Serbian Roma on the relationship between maternal investment, unwanted births disaggregated into mistimed and unwanted children, and child nutritional measures. Several limitations might have biased the results. The MICS studies design was cross-sectional, preventing causal inference. Variables were mostly self-reported, thus allowing for potential biases. Retrospective reports by the mother on childbearing intentions may be influenced by the survival of the child (Flatø, Reference Flatø2018). Other confounding variables such as mother’s height and health, gestation and previous preterm or low birth weight births were not collected. Furthermore, in this mixed-age sample, age may be a major confounding factor in assessing the relationship between parity and growth outcomes. HAZ and WAZ were calculated relative to age and gender, while the age range of 0-2 years encompasses vastly different periods of infant growth trajectories. In populations with typically high prevalence of childhood stunting, the prevalence increases over the first two years of life. Infants born low birthweight or small-for-gestational age may also experience catchup or rapid growth, and cross major WAZ centiles. Although birthweight was positively associated with HAZ and WAZ in this sample, that affect may be weakened if there were unaccounted associations between birthweight and WAZ, dependent on age at measurement.

Usage of modern contraceptives is limited among Roma women albeit their wider use could lead to a decrease of unwanted pregnancies and number of children, with presumably less within sibling competition for scarce resources. Unintended births contribute to unwanted population growth, which in turn may compromise provision of social services (Dutta et al., Reference Dutta, Shekhar and Prashad2015). Roma women, however, may be more concerned about having too few rather than too many children (Costa et al., Reference Costa, Trumble, Kaplan and Gurven2018). As in many other traditional societies, Roma patterns of fertility are traditionally institutionalized in cultural practices and rules regulating marriage, with very little input and control over childbearing from the women themselves (Čvorović & Coe, Reference Čvorović and Coe2019).

Children from high-risk groups contribute disproportionately to adverse adult outcomes. Among the Roma, short stature and lower birth weight measurements are so common that they are considered as a norm (Stanković et al., Reference Stanković, Živić, Ignjatović, Stojanović, Bogdanović, Novak and Vorgučin2016). The findings of the present study may serve health and policymakers to engage in the development of childhood nutrition programs among the Roma. Thus, among high-risk children, assessment of linear growth should be made routine practice to determine whether a child has a predisposition towards a growth problem that should be accounted for (de Onis & Branca, Reference De Onis and Branca2016). Future studies should examine the costs and benefits of welfare on childbearing and nutrition in Roma children (Paxson & Schady, Reference Paxson and Schady2010).

Conclusion

This study assessed the association between maternal investment, unwanted births disaggregated into mistimed and unwanted children, and child nutritional outcomes in a poor population of Serbian Roma. Differentiating between unwanted births, i.e., between mistimed and unwanted children, revealed the importance of maternal and child characteristics that have influenced differences in Roma children outcomes. Thus, in this resource-limited, high fertility setting, parental investment was reflected in measures of child nutrition: lower maternal investment in utero was associated with compromised child nutrition, with the aggravated effect for height if the child was unwanted. Unwanted children were later borns, to older, higher parity mothers in comparison to mistimed children. New findings of this study may help to stimulate development of early childhood nutrition programs among the Roma.

Statements and Declarations

Funding

No funding was received for conducting this study.

Conflicts of Interest

none.

Ethical Approval

The author asserts that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.