Introduction

It has been well documented that individuals residing in the United States do not consume adequate amounts of fruits and vegetables (F&Vs).(Reference Ansai and Wambogo1–3) According to the Dietary Guidelines for Americans (DGAs), adults should consume approximately 1⋅5–2 cup-equivalents of fruits (approximately 120–160 g) and 2–3 cup-equivalents of vegetables (approximately 160–240 g) daily.(3) Presently, 10 % of adults meet the vegetable recommendation and 12⋅3 % of adults meet the fruit recommendation.(Reference Lee, Moore, Park, Harris and Blanck2) Adequate intake of F&V may reduce the risk of developing obesity, cardiovascular disease, and diabetes.(Reference Mokdad, Ballestros and Echko4) Schwingshackl et al. found that consuming up to 300 g of vegetables per day decreases the risk of mortality by 11 % and consuming up to 250–300 g of fruit per day decreases the risk of mortality by 10 %.(Reference Schwingshackl, Schwedhelm and Hoffmann5)

Many factors contribute to the inadequate intake of F&V among Americans, however the most prominent barrier cited is cost.(Reference Haynes-Maslow, Parsons, Wheeler and Leone6) It has been shown that a 10 % decrease in price of healthful foods increases consumption by approximately 12 %, and specifically increases consumption of F&V by 14 %.(Reference Afshin, Peñalvo and Del Gobbo7) Multiple programs have been created at the state and municipal levels to increase consumption of F&Vs by reducing costs.(Reference Young, Aquilante and Solomon8–Reference Phipps, Braitman and Stites19) The most widely used program focuses on increasing F&V dollars for Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) recipients by doubling or matching(Reference Young, Aquilante and Solomon8,Reference Savoie-Roskos, Durward, Jeweks and LeBlanc9,Reference Bradford, Quinn and Walkinshaw11–Reference Durward, Savoie-Roskos and Atoloye13) or providing rebates(Reference Olsho, Klerman, Wilde and Bartlett10) on dollars spent on F&Vs. These programs often require participants to purchase F&Vs at farmers’ markets.(Reference Young, Aquilante and Solomon8,Reference Savoie-Roskos, Durward, Jeweks and LeBlanc9,Reference Bradford, Quinn and Walkinshaw11–Reference Durward, Savoie-Roskos and Atoloye13) The findings are encouraging as all have shown an increase in F&V purchases and/or consumption among participants.(Reference Young, Aquilante and Solomon8–Reference Durward, Savoie-Roskos and Atoloye13) Similar results have been seen in programs aimed at increasing consumption of F&Vs among Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) participants.(Reference Herman, Harrison, Afifi and Jenks14,Reference Anderson, Bybee and Brown15) Additionally, programs have been developed to offer direct vouchers of varying amounts(Reference Marcinkevage, Auvinen and Nambuthiri16–Reference Lindsay, Lambert and Penn18) or rebates(Reference Phipps, Braitman and Stites19) to participants. These programs have resulted in an increase of F&V consumption across the United States.(Reference Marcinkevage, Auvinen and Nambuthiri16–Reference Phipps, Braitman and Stites19) These data support that decreasing costs may increase purchases and consumption of F&Vs.

The U.S. government has allocated $25 million to pilot additional produce prescription programs which provide F&Vs as well as education.(Reference Mozaffarian, Griffin and Mande20) At the present time, there are multiple models, but no clear consensus on which produce prescription programs are the most effective. This in part may be due to the different settings in which programs are administered. Engel and Ruder conducted a scoping review to identify F&V incentive programs for SNAP participants, documenting the different program structures.(Reference Engel and Ruder21) Whereas Veldheer et al. conducted a scoping review of the different types of program healthcare organisations implement to improve F&V access.(Reference Veldheer, Scartozzi and Knehans22) These reviews provide great insight into two important populations; however, there are still many other produce prescription programs that are not classified into one of these two groups. Therefore, the objective of this scoping review is to identify and categorise the different models of fruit and vegetable prescription programs offered in a community-based setting, in order to understand how they vary in terms of methodology, population characteristics, and outcomes measured.

Methods

This study utilised the framework for scoping reviews presented by Arksey and O'Malley(Reference Arksey and O'Malley23) along with the recommended enhancements from Levac et al.(Reference Levac, Colquhoun and O'Brien24) The five stages of the framework include: (1) Identifying the research question; (2) Identifying relevant studies; (3) Study selection; (4) Charting the data; and (5) Collating, summarising, and reporting the results.(Reference Arksey and O'Malley23) The research objective was defined prior to data collection; however, following Levac et al. (Reference Levac, Colquhoun and O'Brien24) recommendations, the objective was slightly altered after the relevant studies were identified (stage two), as the original objective was deemed too broad.

Data collection

Data collection was completed between June 2021 and September 2021. To ensure a robust review, the researchers sought the assistance of the university research librarian. The librarian assisted in developing search streams using text terms and Medical Subject Heading (MeSH) terms. The text terms included: fruit, vegetable, produce, veggie, prescription, health promotion/s, health campaign/s, wellness program/s, incentive*, food voucher/s, food assistance, food stamp/s, school meal/s, school lunch/es, food pantry/ies, food bank/s, and the MeSH terms included: fruit, vegetable, crops, agricultural, health promotion, prescriptions, and food assistance. The researchers used these terms in seven electronic databases including PubMed (Medline), Scopus, Google Scholar, CINAHL, USDA website, and Cochrane Database. Additionally, the Gray Literature Database, OAIster, ProQuest, and MedNar were used to ensure a comprehensive search. In order to capture all possible literature, date parameters were not set for the search.

Due to the nature of a scoping review, the inclusion and exclusion criteria were broad. To be included, the article must describe a community-based program that incentivised F&V consumption, must be written in the English language, and the full-text article must be available. Community-based programs were defined as any F&V prescription being distributed or redeemed within the community setting. During the screening process, F&V prescription programs were defined as an intervention delivering a repeated prescription for F&V to address a diet-related health risk including food insecurity. There were four key elements that determined if a ‘program’ qualified: there must be a prescription for F&V, must require redemption or receipt of F&Vs, there must be a repeated dosage, and participants must have a diet-related health risk including food insecurity. Exclusion criteria included duplicate articles, non-intervention studies, and F&V prescription programs administered exclusively by a healthcare organisation as defined by Veldheer et al. (Reference Veldheer, Scartozzi and Knehans22)

All articles from the original search were imported into the Covidence software, which is used to manage systematic reviews.(25) This software removes duplicate articles, maintains accurate count of articles, and allows inclusion and exclusion criteria to be used to categorise articles. Covidence allows for multiple researchers to complete title and abstract screening and full-text review independently of each other by categorising articles as relevant or irrelevant. Additionally, any discordant vote is categorised as a conflict. The initial step of this review consisted of the title and abstract screening, the second step included full-text review, and the final step consisted of data extraction. The two independent researchers met on a weekly basis to discuss all conflicts and reach a consensus on the relevance of the disputed article(s), as well as determine that all necessary data had been extracted.

Data analysis

There were eleven unique variables collected, most of which were categorical. The variables included duration of intervention (weeks), number of participants, model of F&V prescription program (F&V vouchers, cashback rebates, F&V delivery or collection, or combination), education provided during intervention (none offered, cooking skills/classes, with nutrition professional, handouts, or combination), F&V prescription provider (community health centre, school, federal/state program, NGO or charity, or other), F&V produce provider (food bank/pantry, farmers market, grocery store, or combination), targeted age group of intervention (children, adults, or families), target population's health status (overweight/obese, diabetes, hypertension, multiple health conditions, or no health condition), recipient of government assistance (yes or no), diet quality measured (yes or no), health outcomes measured (yes or no), and food security status measured (yes or no). Extracted data was compiled in a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet. Duration of community-based F&V prescription program and number of participants were reported as means (sd), and frequency distribution was used for the remainder of the variables.

Results

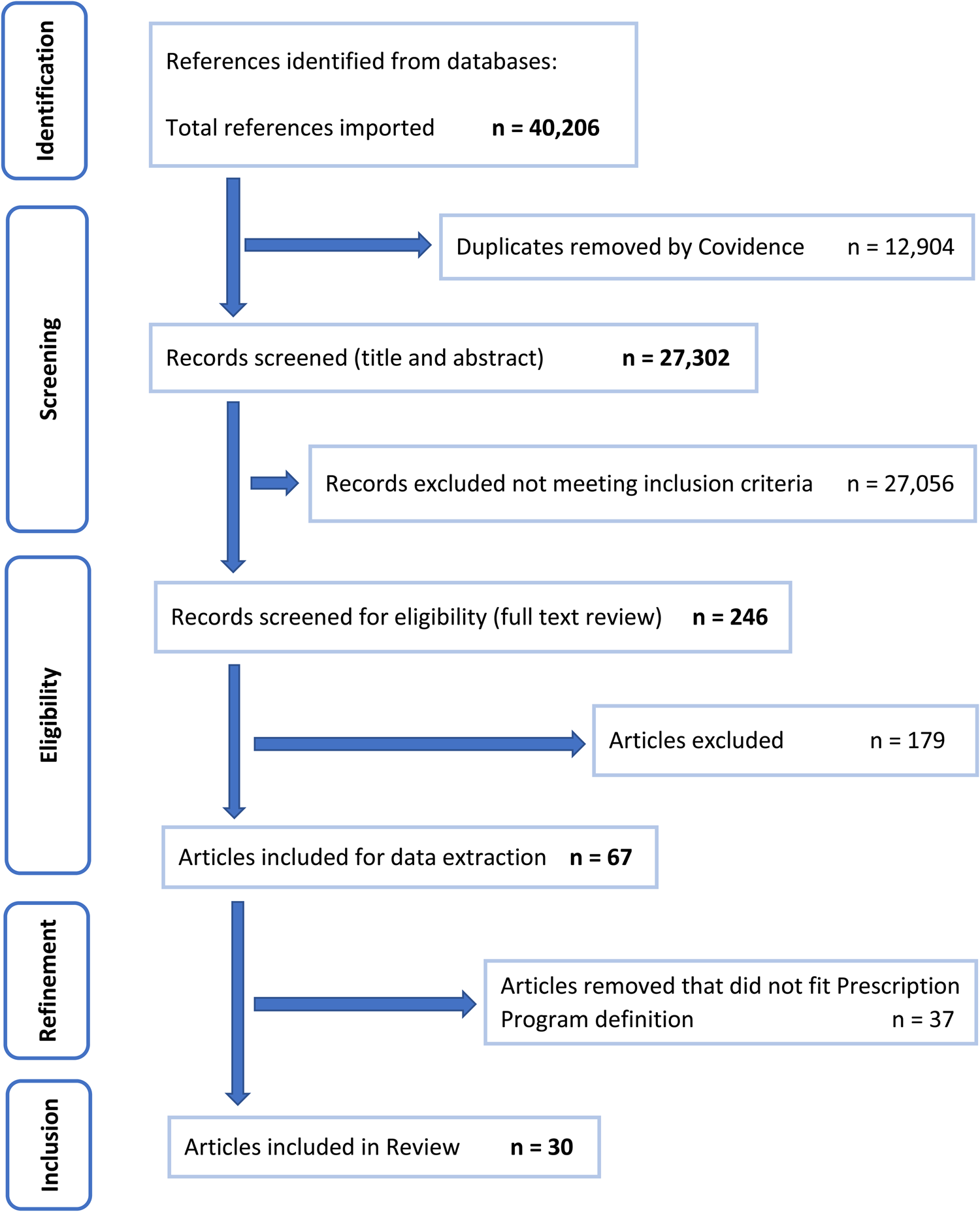

The search identified 27 302 unique records after the removal of duplicates by Covidence software, see flow diagram in Fig. 1 detailing the study selection process for community-based F&V prescription programs. A further 27 056 were removed following title and abstract screening against the inclusion criteria, leaving 246 for full-text review which yielded 67 articles for data extraction. During the review, researchers further refined the search parameters to include the definition of ‘prescription program’ as an intervention delivering a repeated prescription for healthy produce to address a diet-related health risk including food insecurity. Following this refinement, thirty articles were included in the final review. A summary of the study characteristics of the community-based F&V prescription programs is presented in Table 1.

Fig. 1. PRISMA flow diagram detailing the study selection process for community-based fruit and vegetable prescription programs (separate document).

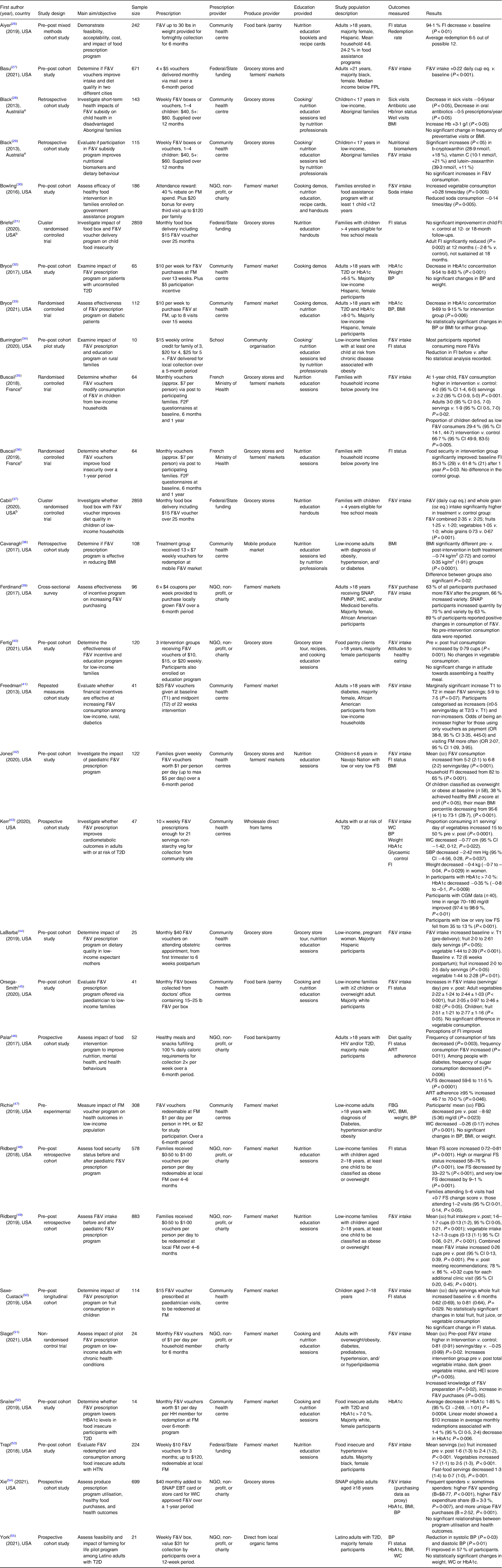

Table 1. Summary of community-based fruit and vegetable prescription programs

F&V, fruit and vegetables; FI, food insecurity; FPL, federal poverty level; Hb, haemoglobin; BMI, body mass index; FM, farmers’ market; NGO, non-governmental organisation; T2D, type 2 diabetes mellitus; HbA1c, glycated haemoglobin; BP, blood pressure; F2F, face to face; SNAP, Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program; FMNP, farmers’ market nutrition program; WIC, women, infants, children special supplemental nutrition program; FS, food security; WC, waist circumference; CGM, continuous glucose monitor; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; VLFS, very low food security; ART, antiretroviral therapy; HH, households; FBG, fasting blood glucose; HTN, hypertension; EBT, electronic benefits transfer.

abcSuperscript letters denote studies carried out on the same intervention.

The thirty studies included in this review comprise twenty-seven unique interventions taking place in the USA (n 25), France (n 1), and Australia (n 1). The mean (sd) F&V program duration was 35⋅2 (25⋅0) weeks, with the most common length being 26 weeks. The number of study participants ranged from 10(Reference Burrington, Hohensee, Tallman and Gadomski34) to 2,859,(Reference Briefel, Chojnacki and Gabor31,Reference Cabili, Briefel, Forrestal, Gabor and Chojnacki37) with a mean (sd) number of participants of 366 (713). Table 2 shows the frequency distribution of categorical variables within program methodology, population characteristics, and outcomes measured in the community-based F&V prescription programs.

Table 2. Distribution of variables within program methodology, population characteristics and outcomes measured in community-based F&V prescription programs

Program methodology

The most common F&V prescription intervention model was F&V vouchers (n 19), which provide vouchers to participants to be redeemed for fresh fruit and vegetables.(Reference Basu, Akers, Berkowitz, Josey, Schillinger and Seligman27,Reference Briefel, Chojnacki and Gabor31–Reference Bryce, Wolfson and Cohen33,Reference Buscail, Margat and Petit35–Reference Jones, VanWassenhove-Paetzold and Thomas42,Reference La Barba and Weber Cullen44,Reference Richie47,Reference Saxe-Custack, LaChance and Hanna-Attisha50–Reference Xie, Price, Curran and Østbye54) The second most frequent model was delivery and/or collection (n 8), with fresh F&V delivered to participants or made available for collection.(Reference Aiyer, Raber and Bello26,Reference Black, Vally and Morris28,Reference Black, Vally and Morris29,Reference Burrington, Hohensee, Tallman and Gadomski34,Reference Kerr, Barua and Glantz43,Reference Orsega-Smith, Slesinger and Cotugna45,Reference Palar, Napoles and Hufstedler46,Reference York, Kujan, Conneely, Glantz and Kerr55) Lastly, two studies used a cashback rebate on F&V purchases, via EBT card and associated with enhancement to SNAP benefits.(Reference Ridberg, Bell, Merritt, Harris, Young and Tancredi48,Reference Ridberg, Bell, Merritt, Harris, Young and Tancredi49) In addition, one study employed a combination of these models.(Reference Bowling, Moretti, Ringelheim, Tran and Davison30)

Another variable within program methodology is provision of education, ranging from simple distribution of information, cooking tips and recipes via handouts(Reference Aiyer, Raber and Bello26,Reference Briefel, Chojnacki and Gabor31,Reference Cabili, Briefel, Forrestal, Gabor and Chojnacki37) (n 3), to cooking classes(Reference Bryce, Guajardo and Ilarraza32) (n 1), to regularly scheduled education sessions led by nutrition professionals(Reference Cavanagh, Jurkowski and Bozlak38,Reference Ridberg, Bell, Merritt, Harris, Young and Tancredi48,Reference Ridberg, Bell, Merritt, Harris, Young and Tancredi49) (n 3). The most common approach (n 14) was to employ a combination of formats.(Reference Black, Vally and Morris28–Reference Bowling, Moretti, Ringelheim, Tran and Davison30,Reference Bryce, Wolfson and Cohen33–Reference Buscail, Gendreau and Daval36,Reference Fertig, Tang and Dahlen40,Reference Jones, VanWassenhove-Paetzold and Thomas42,Reference La Barba and Weber Cullen44,Reference Orsega-Smith, Slesinger and Cotugna45,Reference Slagel, Newman and Sanville51–Reference Trapl, Smith and Joshi53)

Providers of both prescriptions and produce varied depending on the program. The most common provider of F&V prescriptions (n 14) was community health centres,(Reference Aiyer, Raber and Bello26,Reference Black, Vally and Morris28,Reference Black, Vally and Morris29,Reference Bryce, Guajardo and Ilarraza32,Reference Bryce, Wolfson and Cohen33,Reference Cavanagh, Jurkowski and Bozlak38,Reference Freedman, Choi, Hurley, Anadu and Hébert41–Reference Richie47,Reference Saxe-Custack, LaChance and Hanna-Attisha50,Reference Snailer, Painter and Duncan52) followed by non-governmental organisations, other non-profit, and charitable foundations(Reference Bowling, Moretti, Ringelheim, Tran and Davison30,Reference Ferdinand, Torres, Scott, Saeed and Scribner39,Reference Fertig, Tang and Dahlen40,Reference Palar, Napoles and Hufstedler46,Reference Ridberg, Bell, Merritt, Harris, Young and Tancredi48,Reference Ridberg, Bell, Merritt, Harris, Young and Tancredi49,Reference Slagel, Newman and Sanville51,Reference Xie, Price, Curran and Østbye54,Reference York, Kujan, Conneely, Glantz and Kerr55) (n 9). Other providers included federal/state programs(Reference Basu, Akers, Berkowitz, Josey, Schillinger and Seligman27,Reference Briefel, Chojnacki and Gabor31,Reference Cabili, Briefel, Forrestal, Gabor and Chojnacki37,Reference Trapl, Smith and Joshi53) (n 4) and schools(Reference Burrington, Hohensee, Tallman and Gadomski34) (n 1). The produce mainly came from one of three sources: Farmers’ markets(Reference Bowling, Moretti, Ringelheim, Tran and Davison30,Reference Bryce, Guajardo and Ilarraza32,Reference Bryce, Wolfson and Cohen33,Reference Ferdinand, Torres, Scott, Saeed and Scribner39,Reference Freedman, Choi, Hurley, Anadu and Hébert41,Reference Richie47–Reference Trapl, Smith and Joshi53) (n 12), grocery stores(Reference Basu, Akers, Berkowitz, Josey, Schillinger and Seligman27–Reference Black, Vally and Morris29,Reference Briefel, Chojnacki and Gabor31,Reference Cabili, Briefel, Forrestal, Gabor and Chojnacki37,Reference Fertig, Tang and Dahlen40,Reference La Barba and Weber Cullen44,Reference Xie, Price, Curran and Østbye54) (n 8), or food banks and pantries(Reference Aiyer, Raber and Bello26,Reference Orsega-Smith, Slesinger and Cotugna45,Reference Palar, Napoles and Hufstedler46) (n 3), with several (n 7) utilising a combination.(Reference Burrington, Hohensee, Tallman and Gadomski34–Reference Buscail, Gendreau and Daval36,Reference Cavanagh, Jurkowski and Bozlak38,Reference Jones, VanWassenhove-Paetzold and Thomas42,Reference Kerr, Barua and Glantz43,Reference York, Kujan, Conneely, Glantz and Kerr55)

Population characteristics

The majority of F&V prescription interventions exclusively included adults(Reference Aiyer, Raber and Bello26,Reference Basu, Akers, Berkowitz, Josey, Schillinger and Seligman27,Reference Bryce, Guajardo and Ilarraza32,Reference Bryce, Wolfson and Cohen33,Reference Cavanagh, Jurkowski and Bozlak38–Reference Freedman, Choi, Hurley, Anadu and Hébert41,Reference Kerr, Barua and Glantz43,Reference La Barba and Weber Cullen44,Reference Palar, Napoles and Hufstedler46,Reference Richie47,Reference Slagel, Newman and Sanville51–Reference York, Kujan, Conneely, Glantz and Kerr55) (n 17), 30 % targeted families(Reference Bowling, Moretti, Ringelheim, Tran and Davison30,Reference Briefel, Chojnacki and Gabor31,Reference Burrington, Hohensee, Tallman and Gadomski34–Reference Cabili, Briefel, Forrestal, Gabor and Chojnacki37,Reference Orsega-Smith, Slesinger and Cotugna45,Reference Ridberg, Bell, Merritt, Harris, Young and Tancredi48,Reference Ridberg, Bell, Merritt, Harris, Young and Tancredi49) (n 9), and children made up the target population for the smallest proportion of the studies(Reference Black, Vally and Morris28,Reference Black, Vally and Morris29,Reference Jones, VanWassenhove-Paetzold and Thomas42,Reference Saxe-Custack, LaChance and Hanna-Attisha50) (n 4). Exactly half of the studies targeted populations with a specific health status, most commonly type 2 diabetes(Reference Bryce, Guajardo and Ilarraza32,Reference Bryce, Wolfson and Cohen33,Reference Freedman, Choi, Hurley, Anadu and Hébert41,Reference Kerr, Barua and Glantz43,Reference Snailer, Painter and Duncan52,Reference Xie, Price, Curran and Østbye54,Reference York, Kujan, Conneely, Glantz and Kerr55) (n 7), followed by overweight and obesity(Reference Burrington, Hohensee, Tallman and Gadomski34,Reference Ridberg, Bell, Merritt, Harris, Young and Tancredi48,Reference Ridberg, Bell, Merritt, Harris, Young and Tancredi49) (n 3), others included hypertension(Reference Trapl, Smith and Joshi53) and HIV-positive status.(Reference Palar, Napoles and Hufstedler46) Participation in a government assistance program was required in 27 % (n 8) of studies,(Reference Black, Vally and Morris28–Reference Briefel, Chojnacki and Gabor31,Reference Burrington, Hohensee, Tallman and Gadomski34,Reference Cabili, Briefel, Forrestal, Gabor and Chojnacki37,Reference Ferdinand, Torres, Scott, Saeed and Scribner39,Reference Xie, Price, Curran and Østbye54) although all of the studies described one or more indicators of low income or food insecurity measurement.

Other trends were seen within the target populations; however, these could not be collated as frequencies due to the differences in reporting between studies. Target populations were majority female,(Reference Aiyer, Raber and Bello26,Reference Basu, Akers, Berkowitz, Josey, Schillinger and Seligman27,Reference Bowling, Moretti, Ringelheim, Tran and Davison30,Reference Bryce, Guajardo and Ilarraza32,Reference Bryce, Wolfson and Cohen33,Reference Buscail, Margat and Petit35,Reference Buscail, Gendreau and Daval36,Reference Ferdinand, Torres, Scott, Saeed and Scribner39,Reference Fertig, Tang and Dahlen40–Reference La Barba and Weber Cullen44,Reference Richie47–Reference York, Kujan, Conneely, Glantz and Kerr55) and majority non-white,(Reference Aiyer, Raber and Bello26–Reference Bowling, Moretti, Ringelheim, Tran and Davison30,Reference Bryce, Guajardo and Ilarraza32,Reference Bryce, Wolfson and Cohen33,Reference Cavanagh, Jurkowski and Bozlak38,Reference Ferdinand, Torres, Scott, Saeed and Scribner39,Reference Freedman, Choi, Hurley, Anadu and Hébert41–Reference La Barba and Weber Cullen44,Reference Ridberg, Bell, Merritt, Harris, Young and Tancredi48,Reference Ridberg, Bell, Merritt, Harris, Young and Tancredi49,Reference Saxe-Custack, LaChance and Hanna-Attisha50,Reference Trapl, Smith and Joshi53–Reference York, Kujan, Conneely, Glantz and Kerr55) where specified.

Study designs

There was considerable heterogeneity in the design of the different studies, with three main study designs used. The first being non-randomised observational study designs (n 24);(Reference Aiyer, Raber and Bello26–Reference Bowling, Moretti, Ringelheim, Tran and Davison30,Reference Bryce, Guajardo and Ilarraza32,Reference Burrington, Hohensee, Tallman and Gadomski34,Reference Cavanagh, Jurkowski and Bozlak38,Reference Ferdinand, Torres, Scott, Saeed and Scribner39–Reference Saxe-Custack, LaChance and Hanna-Attisha50,Reference Snailer, Painter and Duncan52–Reference York, Kujan, Conneely, Glantz and Kerr55) the second, randomised controlled trials (n 5);(Reference Briefel, Chojnacki and Gabor31,Reference Bryce, Wolfson and Cohen33,Reference Buscail, Margat and Petit35–Reference Cabili, Briefel, Forrestal, Gabor and Chojnacki37) and the third, non-randomised clinical trial (n 1).(Reference Slagel, Newman and Sanville51)

Outcomes measured

Change in dietary quality was measured in the majority of studies(Reference Basu, Akers, Berkowitz, Josey, Schillinger and Seligman27,Reference Black, Vally and Morris29,Reference Bowling, Moretti, Ringelheim, Tran and Davison30,Reference Burrington, Hohensee, Tallman and Gadomski34,Reference Buscail, Margat and Petit35,Reference Cabili, Briefel, Forrestal, Gabor and Chojnacki37,Reference Fertig, Tang and Dahlen40–Reference Palar, Napoles and Hufstedler46,Reference Ridberg, Bell, Merritt, Harris, Young and Tancredi49,Reference Saxe-Custack, LaChance and Hanna-Attisha50,Reference Slagel, Newman and Sanville51,Reference Trapl, Smith and Joshi53) (n 17), only one of which reported no statistically significant improvement in diet quality.(Reference Burrington, Hohensee, Tallman and Gadomski34) The number and type of instruments used to measure diet quality varied widely, as did their levels of reliability, these included food frequency questionnaire (FFQ)(Reference Buscail, Margat and Petit35) (n 1), validated 24-hour recall methods(Reference Basu, Akers, Berkowitz, Josey, Schillinger and Seligman27,Reference Black, Vally and Morris29,Reference Fertig, Tang and Dahlen40,Reference Slagel, Newman and Sanville51) (n 4), HEI scores(Reference Basu, Akers, Berkowitz, Josey, Schillinger and Seligman27,Reference Slagel, Newman and Sanville51) (n 2), and nutritional biomarkers(Reference Black, Vally and Morris29) (n 1). Several of the studies used externally validated screeners to measure F&V intake, including NCI dietary screener(Reference Cabili, Briefel, Forrestal, Gabor and Chojnacki37,Reference Freedman, Choi, Hurley, Anadu and Hébert41,Reference Ridberg, Bell, Merritt, Harris, Young and Tancredi49) (n 3), the Block screener(Reference Saxe-Custack, LaChance and Hanna-Attisha50) (n 1), and the Behavioural Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS)(Reference Jones, VanWassenhove-Paetzold and Thomas42) (n 1), in addition to other instruments not often cited in the literature(Reference La Barba and Weber Cullen44,Reference Palar, Napoles and Hufstedler46,Reference Trapl, Smith and Joshi53) (n 3). Internally designed, non-validated surveys were used to assess F&V intake in the remainder(Reference Bowling, Moretti, Ringelheim, Tran and Davison30,Reference Burrington, Hohensee, Tallman and Gadomski34,Reference Kerr, Barua and Glantz43,Reference Orsega-Smith, Slesinger and Cotugna45) (n 4).

Outcomes related to health status were also measured in eleven of the studies,(Reference Black, Vally and Morris28,Reference Bryce, Guajardo and Ilarraza32,Reference Bryce, Wolfson and Cohen33,Reference Cavanagh, Jurkowski and Bozlak38,Reference Jones, VanWassenhove-Paetzold and Thomas42,Reference Kerr, Barua and Glantz43,Reference Palar, Napoles and Hufstedler46,Reference Richie47,Reference Snailer, Painter and Duncan52,Reference Xie, Price, Curran and Østbye54,Reference York, Kujan, Conneely, Glantz and Kerr55) with all but one(Reference Xie, Price, Curran and Østbye54) reporting a statistically significant improvement in at least one health measure. All outcome measures were conducted by a trained medical or research staff, or retrieved from medical records, none relied on self-report. The different health outcome measures included frequency of sick visits to healthcare provider and/or hospital attendances(Reference Black, Vally and Morris28) (n 1), number of oral antibiotic prescriptions(Reference Black, Vally and Morris28) (n 1), iron status(Reference Black, Vally and Morris28) (n 1), weight(Reference Bryce, Guajardo and Ilarraza32,Reference Kerr, Barua and Glantz43,Reference Richie47,Reference York, Kujan, Conneely, Glantz and Kerr55) (n 4), BMI(Reference Black, Vally and Morris28,Reference Cavanagh, Jurkowski and Bozlak38,Reference Jones, VanWassenhove-Paetzold and Thomas42,Reference Palar, Napoles and Hufstedler46,Reference Richie47,Reference Xie, Price, Curran and Østbye54,Reference York, Kujan, Conneely, Glantz and Kerr55) (n 7), blood pressure(Reference Bryce, Guajardo and Ilarraza32,Reference Bryce, Wolfson and Cohen33,Reference Kerr, Barua and Glantz43,Reference Richie47,Reference Xie, Price, Curran and Østbye54,Reference York, Kujan, Conneely, Glantz and Kerr55) (n 6), glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) level(Reference Bryce, Guajardo and Ilarraza32,Reference Bryce, Wolfson and Cohen33,Reference Kerr, Barua and Glantz43,Reference Palar, Napoles and Hufstedler46,Reference Snailer, Painter and Duncan52,Reference Xie, Price, Curran and Østbye54,Reference York, Kujan, Conneely, Glantz and Kerr55) (n 7), waist circumference(Reference Kerr, Barua and Glantz43,Reference Richie47,Reference York, Kujan, Conneely, Glantz and Kerr55) (n 3), glycaemic control (continuous glucose monitor and fasting blood sugar measurements)(Reference Kerr, Barua and Glantz43,Reference Palar, Napoles and Hufstedler46,Reference Richie47) (n 3), and antiretroviral therapy adherence(Reference Palar, Napoles and Hufstedler46) (n 1).

Food security status was also an outcome of interest in eleven of the studies,(Reference Aiyer, Raber and Bello26,Reference Briefel, Chojnacki and Gabor31,Reference Burrington, Hohensee, Tallman and Gadomski34,Reference Buscail, Gendreau and Daval36,Reference Jones, VanWassenhove-Paetzold and Thomas42,Reference Kerr, Barua and Glantz43,Reference Orsega-Smith, Slesinger and Cotugna45,Reference Palar, Napoles and Hufstedler46,Reference Ridberg, Bell, Merritt, Harris, Young and Tancredi48,Reference Saxe-Custack, LaChance and Hanna-Attisha50,Reference York, Kujan, Conneely, Glantz and Kerr55) with only one study not reporting a statistically significant improvement in food security status.(Reference Saxe-Custack, LaChance and Hanna-Attisha50) There was less variation in the measurement instruments compared to diet quality measurements, with the majority using the widely used USDA 18-item Household Food Security Survey(Reference Briefel, Chojnacki and Gabor31,Reference Buscail, Gendreau and Daval36,Reference Palar, Napoles and Hufstedler46,Reference Ridberg, Bell, Merritt, Harris, Young and Tancredi48,Reference York, Kujan, Conneely, Glantz and Kerr55) (n 5). Others used the 2-item(Reference Aiyer, Raber and Bello26) (n 1) and 6-item(Reference Jones, VanWassenhove-Paetzold and Thomas42,Reference Kerr, Barua and Glantz43,Reference Saxe-Custack, LaChance and Hanna-Attisha50) (n 3) versions which have been shown to have high sensitivity and specificity when compared to the original Household Food Security Survey tool.(Reference Hager, Quigg and Black56,Reference Blumberg, Bialostosky and Hamilton57) Two studies used internally designed, non-validated surveys.(Reference Burrington, Hohensee, Tallman and Gadomski34,Reference Orsega-Smith, Slesinger and Cotugna45)

Discussion

The results of this review show encouraging outcomes for individuals who receive and utilise produce prescriptions from community-based organisations. Similar to previous studies that showed increased consumption of F&Vs when financial incentives are provided,(Reference Afshin, Peñalvo and Del Gobbo7) SNAP benefits are increased,(Reference Young, Aquilante and Solomon8–Reference Durward, Savoie-Roskos and Atoloye13) WIC benefits are increased,(Reference Herman, Harrison, Afifi and Jenks14,Reference Anderson, Bybee and Brown15) or when direct vouchers(Reference Marcinkevage, Auvinen and Nambuthiri16–Reference Lindsay, Lambert and Penn18) or rebates(Reference Phipps, Braitman and Stites19) are provided, the majority of community-based produce prescription programs showed an increase in F&V consumption when a financial incentive was offered.(Reference Basu, Akers, Berkowitz, Josey, Schillinger and Seligman27,Reference Burrington, Hohensee, Tallman and Gadomski34,Reference Buscail, Margat and Petit35,Reference Cabili, Briefel, Forrestal, Gabor and Chojnacki37,Reference Freedman, Choi, Hurley, Anadu and Hébert41,Reference Jones, VanWassenhove-Paetzold and Thomas42,Reference La Barba and Weber Cullen44–Reference Palar, Napoles and Hufstedler46,Reference Ridberg, Bell, Merritt, Harris, Young and Tancredi49,Reference Slagel, Newman and Sanville51,Reference Trapl, Smith and Joshi53) A minority of the studies only showed increases in vegetable(Reference Bowling, Moretti, Ringelheim, Tran and Davison30,Reference Kerr, Barua and Glantz43) or fruit consumption,(Reference Fertig, Tang and Dahlen40,Reference Saxe-Custack, LaChance and Hanna-Attisha50) with even fewer showing no statistically significant increases in overall F&V intake.(Reference Black, Vally and Morris29,Reference Fertig, Tang and Dahlen40) Also, two studies showed an increase in F&Vs purchased but did not report pre–post consumption data.(Reference Ferdinand, Torres, Scott, Saeed and Scribner39,Reference Xie, Price, Curran and Østbye54) These results further support the benefits of providing financial assistance to offset the often-cited barrier of purchasing F&V, which is cost.(Reference Haynes-Maslow, Parsons, Wheeler and Leone6) The community-based produce prescription programs are in fact assisting individuals increase F&V consumption moving them closer to meeting the DGA's recommendations.(3)

Lessening the financial burden associated with purchasing groceries may directly lead households or individuals towards improved food security status. This trend was consistently seen in ten of the articles reviewed,(Reference Aiyer, Raber and Bello26,Reference Burrington, Hohensee, Tallman and Gadomski34,Reference Buscail, Gendreau and Daval36,Reference Cabili, Briefel, Forrestal, Gabor and Chojnacki37,Reference Jones, VanWassenhove-Paetzold and Thomas42,Reference Kerr, Barua and Glantz43,Reference Orsega-Smith, Slesinger and Cotugna45,Reference Palar, Napoles and Hufstedler46,Reference Ridberg, Bell, Merritt, Harris, Young and Tancredi48,Reference York, Kujan, Conneely, Glantz and Kerr55) especially among individuals classified as very low food secure and low food secure.(Reference Kerr, Barua and Glantz43,Reference Palar, Napoles and Hufstedler46,Reference Ridberg, Bell, Merritt, Harris, Young and Tancredi48) Interestingly, the article that did not find statistically significant improvement in food security status also did not see an increase in F&V consumption.(Reference Saxe-Custack, LaChance and Hanna-Attisha50) Whereas, all other studies that measured both food security status and F&V intake showed statistically significant improvements in both indices.(Reference Burrington, Hohensee, Tallman and Gadomski34,Reference Jones, VanWassenhove-Paetzold and Thomas42,Reference Kerr, Barua and Glantz43,Reference Orsega-Smith, Slesinger and Cotugna45,Reference Palar, Napoles and Hufstedler46) These results indicate a possible correlation between the two variables.

As previously discussed, increasing F&V intake may reduce the risk of developing certain chronic diseases and decrease overall mortality risk.(Reference Mokdad, Ballestros and Echko4,Reference Schwingshackl, Schwedhelm and Hoffmann5) Although many of the studies reviewed measured certain health-related indices,(Reference Black, Vally and Morris28,Reference Black, Vally and Morris29,Reference Bryce, Guajardo and Ilarraza32,Reference Bryce, Wolfson and Cohen33,Reference Cavanagh, Jurkowski and Bozlak38,Reference Jones, VanWassenhove-Paetzold and Thomas42,Reference Kerr, Barua and Glantz43,Reference Palar, Napoles and Hufstedler46,Reference Richie47,Reference Snailer, Painter and Duncan52,Reference Xie, Price, Curran and Østbye54,Reference York, Kujan, Conneely, Glantz and Kerr55) only four measured health indicators and actual F&V intake.(Reference Jones, VanWassenhove-Paetzold and Thomas42,Reference Kerr, Barua and Glantz43,Reference Palar, Napoles and Hufstedler46,Reference Xie, Price, Curran and Østbye54) Additionally, only Jones et al. (Reference Jones, VanWassenhove-Paetzold and Thomas42) (BMI z-score) and Kerr et al. (Reference Kerr, Barua and Glantz43) (waist circumference, systolic blood pressure, HbA1c, glucose, and weight in women) showed statistically significant improvements in health outcomes with an increase in F&V consumption. Diabetes management was a focus for many of the studies,(Reference Bryce, Guajardo and Ilarraza32,Reference Bryce, Wolfson and Cohen33,Reference Kerr, Barua and Glantz43,Reference Richie47,Reference Snailer, Painter and Duncan52,Reference York, Kujan, Conneely, Glantz and Kerr55) with five showing improvement in HbA1c(Reference Bryce, Guajardo and Ilarraza32,Reference Bryce, Wolfson and Cohen33,Reference Kerr, Barua and Glantz43,Reference Snailer, Painter and Duncan52) and fasting blood glucose levels(Reference Richie47) during the produce prescription intervention timeframe. Though encouraging, it is difficult to determine what specific factors contributed to improved glycaemic control during these interventions, as dietary data was not reported.

There are clearly opportunities to utilise community-based incentive programs to improve both dietary quality, food security status, and health outcomes, which has been supported by previous scoping reviews exploring the application of F&V prescription programs in other areas.(Reference Engel and Ruder21,Reference Veldheer, Scartozzi and Knehans22) However, they too have made similar comments regarding the variety and heterogeneity in design and quality of programs. Focusing specifically on healthcare organisations, Veldheer et al. (Reference Veldheer, Scartozzi and Knehans22) found most studies assessing dietary quality showed improvements, although health-related outcomes were more mixed. Engel and Ruder found some measure of positive impact in all but one of the studies in their review of F&V incentive programs for SNAP participants.(Reference Engel and Ruder21) The current review adds to the literature that providing produce prescriptions in a variety of community settings, outside of healthcare organisations and SNAP, improves the overall intake of F&V, food security status, and certain health outcomes. The similarities among the programs could provide a standardised produce prescription blueprint to be implemented across different settings.

This scoping review has some definite strengths, it was conducted using the methodological framework from Arksey and O'Malley(Reference Arksey and O'Malley23) with enhancements from Levac et al. (Reference Levac, Colquhoun and O'Brien24), and was conducted following the PRISMA-ScR guidelines and checklist.(Reference Tricco, Lillie and Zarin58) The comprehensive database search was guided by a specialist, and all screening, data extraction, and mapping were conducted by two reviewers independently. There are some limitations, the search revealed several abstracts that met the criteria but were unable to locate the full-text article and therefore not included, this may have meant some relevant data could have been missed. In addition, following the broad format for a scoping review may have meant that search was too wide, a more targeted research question may have helped reduce the heterogeneity found across the interventions. Finally, no meaningful statistical analysis could be completed due to the lack of experimental design of most of the studies, plus the limited comparison groups in the non-experimental study designs.

Conclusion

This scoping review of community-based interventions delivering a repeated prescription for healthy produce to address a diet-related health risk found that most studies showed a significant improvement in one or more of the outcomes measured. However, the diversity of measurement tools made meaningful comparisons of the effectiveness of the different programs impossible. In addition, the heterogeneity of program design, dosage and duration, and the format and frequency of education, also make meaningful comparisons difficult. So, while most outcomes showed statistically significant improvements, these limitations raise questions as to the strength of the evidence.

In summary, further study is warranted to compare the magnitude of effects with the different program methodologies, and the education component requires further investigation to understand its contribution to program effectiveness. Most of the studies included in this review were non-randomised and did not have a control group, more rigorously designed and adequately powered RCTs are required to accurately evaluate these types of intervention. Additionally, there are other barriers to the intake of fresh fruit and vegetables besides cost, including access and acceptability, these also require further research. After completion of this review, recommendations for next steps would be to conduct larger randomised control trials to determine the effectiveness of produce prescription programs.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge Patricia Chavez, Library Research Information Specialist at Rush University for her guidance on building the initial search stream for this review.

E. G. B. and M. M. equally contributed to the development of the research question, literature search, literature review, data analysis, and manuscript creation. E. G. B. and M. M. have reviewed and agreed on the final manuscript submission.

The authors declared none.