The Mental Health Act 1983 for England and Wales established the legal framework for the medical treatment of mental disorder for detained patients. One of the protections for patients required by the Act is that once 3 months have elapsed since the person first received medication for mental disorder as a detained patient, medication may only be given if the treatment is authorised by either the clinician in charge of the patient’s care (if the patient consents) or an independent doctor called a second opinion appointed doctor (SOAD) if the patient lacks capacity or refuses. The date from which this 3-month rule applies is called the consent to treatment (CTT) date. At the time of this study, for patients subject to a community treatment order (CTO) all medication had to be authorised by a SOAD and the time limit was 28 days. For electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) the authorisations were required from the start of the detention.

A SOAD is an independent psychiatrist sent at the request of the clinician in charge by the national body responsible for the SOAD service (the Care Quality Commission, CQC). This doctor will interview the patient, a nurse and another professional before deciding what medication (or ECT) may be given to the patient. The medication that may lawfully be prescribed for the patient must be described on the appropriate form, either T2 or T3 for detained in-patients or CTO11 for patients given a CTO. If ‘urgent treatment’ is required it may be authorised by any registered medical practitioner (Sections 62, 64B and 64G) subject to specific additional criteria. The Mental Health Act Code of Practice states that ‘urgent treatment’ applies only if the treatment in question is immediately necessary to:

-

• save the patient’s life;

-

• prevent a serious deterioration of the patient’s condition, and the treatment does not have unfavourable physical or psychological consequences which cannot be reversed;

-

• alleviate serious suffering by the patient and the treatment does not have unfavourable physical or psychological consequences which cannot be reversed and does not entail significant physical hazard; or

-

• prevent patients behaving violently or being a danger to themselves or others, and the treatment represents the minimum interference necessary for that purpose, does not have unfavourable physical or psychological consequences which cannot be reversed and does not entail significant physical hazard. 1

Although it is necessary to have a mechanism to enable patients to receive treatment that is ‘immediately necessary’, treatment given under these provisions is not subject to the same independent safeguard as that prescribed with the authority of a SOAD. Although previous similar studies by Johnson & Curtice and Haw & Shanmugarutnum highlighted that the most common reasons for the use of urgent treatment provisions were ECT and rapid tranquillisation, Reference Johnson and Curtice2,Reference Haw and Shanmugarutnum3 there was a general feeling among the practising clinicians that these provisions were being more commonly used for the complete treatment plan waiting for authorisation by the SOAD after the CTT date applied, in an attempt to provide lawful treatment. We attempted to find out whether this is actually the case.

The aim of our study was to understand the circumstances in which Sections 62 and 64B/G are used in clinical practice and to confirm, or otherwise, compliance with the Mental Health Act 1983. Also, we aimed to see whether the urgent treatment was required as a result of delay in assessment by a SOAD, and if so, to consider the cause of the delay.

Method

The study was conducted retrospectively covering a 1-year period from January 2009 to December 2009. A list of patients detained under Sections 62 and 64B during the study period was obtained electronically from the information technology department. Complete lists of patients for whom forms T2 or T3 were filled in and patients commencing treatment under a CTO were also obtained electronically. Section 64 and CTO11 forms were obtained from the Mental Health Act office of the trust. Respective case notes were then located and more detailed information was obtained on the circumstances of use of Sections 62 and 64B/G.

Results

There were 58 instances of use of Section 62, in 39 patients, in the study period of 1 year (this was because Section 62 was used on more than one occasion for some patients). For Section 64B/G, a total of 32 instances were identified in 26 patients. Demographic details of the patient population in each group are detailed in Table 1.

Table 1. Basic data on patients subjected to the urgent treatment provisions of the Mental Health Act during the study period

| Section | Section 62 64B/G |

|

|---|---|---|

| Use of section, n | ||

| Total use | 58 | 32 |

| Patients | 39 | 26 |

| Case notes located | 38 | 22 |

| Demographic characteristics | ||

| Age, years: mean | 46.5 | 43.5 |

| Gender, n (%) | ||

| Male | 25 (64) | 20 (77) |

| Female | 14 (36) | 6 (23) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | ||

| White British | 26 (89) | 16 (50) |

| Asian | 9 (20) | 8 (25) |

| Black Caribbean | 2 (5) | 6 (19) |

| Mixed | 2 (5) | 1 (3) |

| Other | 5 (11) | 1 (3) |

Reasons documented

The reasons documented on the urgent treatment form, detailing the need to use the respective provisions, are summarised opposite.

Section 62

On 26 occasions (45%) Section 62 was used because of a delayed SOAD assessment. On 18 occasions (31%) it was used to prevent serious deterioration of the patient’s condition, 9 times (15%) to prevent the patient acting violently, twice (3%) to save the patient’s life and once (2%) to alleviate serious suffering by the patient. On one form the reason for use was not documented. Details were not obtained from another form as the case notes were not located.

Section 64B/G

Section 64B/G was used on 25 occasions (78%) to prevent serious deterioration of the patient’s condition, 6 times (19%) because of delayed SOAD assessment and once (3%) to alleviate serious suffering by the patient.

Need for urgent treatment

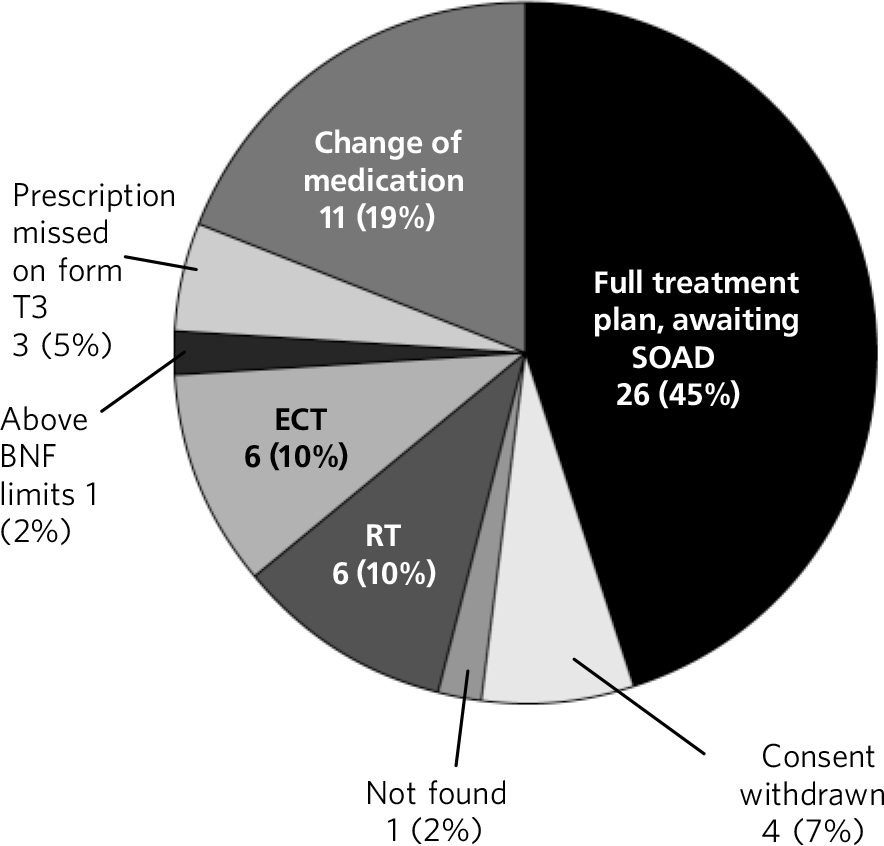

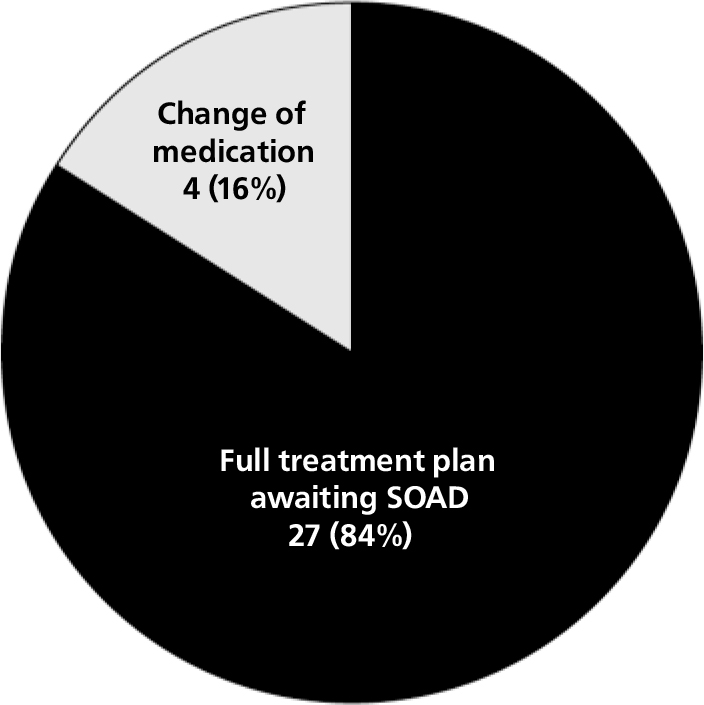

The need for urgent treatment refers to the detailed circumstances as to why the urgent treatment provision was required, as concluded from detailed scrutiny of the case notes. Figures 1 and 2 detail different circumstances of use of emergency treatment provisions of the Mental Health Act.

Fig 1 Need for urgent treatment under Section 62. BNF, British National Formulary; ECT, electroconvulsive therapy; RT, rapid tranquillisation; SOAD, second opinion appointed doctor.

Fig 2 Need for urgent treatment under Sections 64 B and G. SOAD, second opinion appointed doctor.

Section 62

In 26 instances (45%) Section 62 was used for the full treatment plan while waiting for the SOAD. On 11 occasions (19%) it was used to change medications on an already approved treatment plan. Three instances (5%) occurred when Section 62 had to be used to add medications which were erroneously missed on a T3 form by the SOAD. On one occasion (2%) it was used to exceed the authorised maximum dose of a certified medication. In six instances (10%) it was used to administer ECT. On another six occasions (10%) it was required for new, urgent medication (rapid tranquillisation). On four occasions (7%) it had to be used when patients treated in accordance with a T2 form withdrew their consent.

Section 64B/G

The most common reason for use of Section 64B/G was for a full treatment plan while waiting for the SOAD (n = 27, 84%). The other five times (16%) it was used to change medications on an already authorised treatment plan.

Interventions

Section 62 was used on 51 (88%) occasions to administer medication and on 6 (10%) occasions to administer ECT. The medications used were oral antipsychotics (28%), anxiolytics (21%), antimanics (14%), depot antipsychotics (11%), hypnotics (9%), antidepressants (5%), anticholinergics (2%), zuclopenthixol acetate (5%) and others (5%). Section 64B was used in all instances (n = 32, 100%) to administer medication. The medications used were oral antipsychotics (27%), depot antipsychotics (18%), antimanics (14%), anticholinergics (16%), anxiolytics (12%), hypnotics (7%), antidepressants (4%), zuclopenthixol acetate (5%) and others (2%).

Full treatment plan awaiting SOADs

There were 26 instances of the use of Section 62 and 27 instances of the use of Section 64B/G for a full treatment plan while waiting for a SOAD. Waiting times for these are detailed in Table 2.

Table 2. Full treatment plan awaiting second opinion appointed doctor: waiting times

| Time, days | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Median | Minimum | Maximum | |

| Section 62 (n = 26) | ||||

| Time between SOAD request and authorisation | 22 | 21 | 4 | 49 |

| Time between CTT date and SOAD request | –5.33Footnote a | 0 | –22Footnote a | 2 |

| Section 64B/G (n = 27) | ||||

| Time between CTT date and CTO11 formFootnote b | 21.38 | 20 | –10Footnote a | 69 |

CTO, community treatment order; CTT, consent to treatment; SOAD, second opinion appointed doctor.

a Negative numbers indicate number of days before the CTT date.

b Form CTO11 contains details of the authorised treatment plan for a patient on CTO. There were insufficient data with respect to the dates when the request for the SOADs for the CTOs were made.

Use of urgent treatment provisions for ECT

Urgent treatment provisions were used on six occasions for administering ECT. The date of request to SOADs was found in four case notes: the mean elapsed time between sending the SOAD request and receiving authorisation for ECT was 10.5 days (s.d. = 5.80, 95% CI 1.27-19.73; median 10.5, range 5-16).

Discussion

Our study indicates that urgent treatment provisions are increasingly being used for a full treatment plan (medication) while waiting for a SOAD to authorise the plan. This is in contrast to previous studies where ECT or rapid tranquillisation were the most common interventions used under Section 62. Reference Johnson and Curtice2,Reference Haw and Shanmugarutnum3 Although Haw & Shanmugarutnum did not indicate that any of these instances were due to delay in the SOAD authorising the treatment, Reference Haw and Shanmugarutnum3 Johnson & Curtice indicated that in 18% of their cases the urgent treatment provision was used to administer ECT owing to a delay in obtaining SOAD authorisation. Reference Johnson and Curtice2 However, neither study indicated that the urgent treatment provision was used for a full treatment plan while awaiting SOAD approval.

Although it may be argued that one of the reasons for delay in SOAD treatment authorisation could be a delay in sending the request for the same, it does appear from our study that the requests for SOADs were sent on average 5.33 days before the CTT date. Also, although the CQC states that it aims to arrange a visit within 5 working days from receipt of the request made for medications and within 2 working days for ECT, 4 our study shows that this period on average is 22 days for medications and 10.5 days for ECT. The CTO11 forms were received on average 21.4 days after the CTT date.

It is recognised that there is an increased demand for statutory second opinions, particularly since the introduction of CTOs in November 2008 and the requirement that all patients with a CTO should have a SOAD-authorised treatment plan. 1 This applies regardless of whether the patient concerned is capacitous and consenting. Statistics from England and Wales show that 4107 CTOs were made during 2009-2010. 5 Furthermore, between their introduction in November 2008 and the end of March 2010, a total of 6241 CTOs were made - an average of 367 a month. This is in addition to 45 755 hospital detentions during the same period. 5 In 2009-2010 the CQC received 8781 requests for a SOAD to certify medications. 5 This is 6% fewer requests overall compared with 2008-2009. However, services’ use of urgent treatment powers to authorise medication has risen significantly. In 2004-2005 only 6% of patients had been given medication under urgent treatment powers before the SOAD visit; in 2009-2010 this figure had increased to 21% of patients referred for a second opinion. 5 Whether this is due to the increased number of SOAD requests or other difficulties with the CQC - or both - we cannot say.

It is arguable whether administering a full treatment plan while waiting for SOAD authorisation fulfils either the spirit or the letter of the urgent treatment criteria of the Mental Health Act. The evidence suggests that the Act’s safeguards, in relation to medication, and perhaps ECT, are being bypassed by use of the ‘urgent treatment’ provisions because of the non-availability of SOADs. Despite the CQC’s reported decline in requests for SOADs in 2009-2010, 5 practising clinicians and SOADs have undoubtedly felt that the CQC workload with respect to SOAD examination has increased markedly since CTOs were introduced. This raises two separate, but interrelated, issues. First, given the decrease in the total number of SOAD requests, has SOAD availability decreased? If so, why and what can be done about it? This is outside the scope of this paper. Second, can the requirement for SOADs be reduced without significant damage to the safeguards? At the time of this study all patients prescribed medication for mental disorder under a CTO required a SOAD certificate, whereas detained patients only required a SOAD certificate if they refused, or lacked capacity to consent to, the treatment. The CQC stated that consenting patients on a CTO accounted for about 45% of the requests they received for SOAD relating to CTOs. 5 It seems odd to have greater protection for patients on a CTO than for those detained in hospital. This anomaly has now been corrected so that capacitous consenting patients on a CTO do not now require a SOAD certificate.

Study implications

Our study suggests that the urgent treatment provisions of the Mental Health Act 1983 are increasingly being used for a full treatment plan while awaiting SOAD examination. This is perhaps unlawful use of the urgent treatment provisions and is certainly outside the guidance of the Code of Practice. 1 In addition, the availability of SOADs may need to be increased or the circumstances for the legal requirements for a SOAD be reduced. The latter may now have been achieved by permitting responsible clinicians to authorise consent to treatment for capacitous consenting patients subject to a CTO as they do for detained in-patients.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.