Introduction: What is the Problem?

School connection is an important protective factor for students, associated with reduced addictive- and substance-related issues, violence and gang involvement, as well as increased attendance and academic achievement (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2009). However, researchers have noted the imbalance in the curriculum and the absence of interventions aimed to specifically increase students’ perception of connection and belonging in the Australian context (Allen, Vella-Brodrick, & Waters, Reference Allen, Vella-Brodrick and Waters2016) and internationally (e.g., Centers for Disease Control & Prevention, 2009). Despite the large body of literature available on enhancing classroom connectedness, more focused interventions aimed at promoting and evaluating school connectedness are required (Shochet, Dadds, Ham, & Montague, Reference Shochet, Dadds, Ham and Montague2006). The general aim of the current research is to propose a model of connectedness relevant for the development of programs and interventions by more precisely defining school connectedness. Despite the importance of connectedness, it has been described by an array of terms in the literature, especially within the school context (Barber & Schluterman, Reference Barber and Schluterman2008), ranging from performance-focused through to strictly social elements (Schulze & Naidu, Reference Schulze and Naidu2014). Connectedness has become interchangeable with a range of terms, including attachment (Allen, Hauser, Bell, & O'Connor, Reference Allen, Hauser, Bell and O'Connor1994) and shared support, particularly of family members (Branje, van Aken, & van Lieshout, Reference Branje, van Aken and van Lieshout2002), and belonging (Allen & Bowles, Reference Allen and Bowles2012), while some definitions emphasise the emotional and social aspects of being connected, such as Libbey's (Reference Libbey2007) definition of school connectedness as a combination of feeling close to and a part of school, feeling safe, feeling that teachers care about and treat students fairly, and being happy at school. As noted by Barber and Schluterman (Reference Barber and Schluterman2008), historically, connectedness has been a poorly defined construct suffering an absence of precision in labelling, conceptualisation, and measurement. Little has changed to improve our understanding of connectedness in relation to these issues since that statement was made, whether considering connectedness generally or in the school context.

While there are factors and defining terms associated with the conception of connectedness, there is also considerable crossover with mixing of terms and factors associated with connectedness (Allen & Bowles, Reference Allen and Bowles2012; Libbey, Reference Libbey2007). Aside from the clarity of the definition of connectedness, the multidimensional and sequential nature of connectedness is also of interest. This research explores the multidimensional and sequential aspects of school connectedness, with the aim of reordering and reconceptualising factors (in the literature), themes, and the defining terms of connectedness.

The Definition of Connectedness

Researchers have defined connectedness variously and contextually. Social psychology and communication scientists van Bel, Smolders, Ijsselsteijn, and de Kort, (Reference van Bel, Smolders, Ijsselsteijn and de Kort2009, p. 67) define ‘social connectedness as a short-term experience of belonging and relatedness, based on quantitative and qualitative social appraisals, and relationship salience’. Early definitions of school connectedness suggest that it is ‘the extent to which students feel personally accepted, respected, included, and supported by others in the school social environment’ (Goodenow, Reference Goodenow1993, p. 80). A general definition of connectedness is ‘the degree to which individuals experience the people and places in their lives as personally meaningful and important’ (Schulze & Naidu, Reference Schulze and Naidu2014). Other aspects of connectedness are emphasised when the context is school; for example, the Wingspread Declaration (Reference Wingspread2004, p. 233) defines school connectedness as ‘the belief by students that adults in the school care about their learning as well as about them as individuals’. Researchers of students and adolescents have defined connectedness as having ‘(1) a relational component, that is, the connection or bond that youth experience with socialising agents, and (2) an autonomy component, that is, the degree to which youth feel that their individuality is validated or supported by the socialising agents’ (Barber & Schluterman, Reference Barber and Schluterman2008, p. 211). Importantly, while attempting to provide a general definition of connectedness associated with school settings, it can be argued that the autonomy-enhancing component can be replaced with a performative component. The main reasons for this are: (1) high-quality activities prime and prompt further high-quality activities and achievements that enhance autonomy and identity; (2) teachers and students have considerably more means of accessing and controlling performance and performative acts that may disrupt, enhance, and transform the student and their experience of learning (Enriquez, Reference Enriquez2011); and (3) following the work of Derrida (Reference Derrida1988) and Butler (Reference Butler2010) that common speech acts or the way students talk about ‘their work’ and how they represent and define their selves are performative. Performative acts contribute to the types of relationship, frequency of contact, and the distance between members of groups, as well as the size of the group and level of connectedness (e.g., friendship, class, school). Such acts, whether more specifically social, relational or academic, are markers of group cohesion, inclusion (Enriquez, Reference Enriquez2011), and exclusion. The same complexity of connection is also reflected in extracurricular activities (McNeely, Nonnemaker, & Blum, Reference McNeely, Nonnemaker and Blum2002). From this perspective, the definition of connectedness in this article is the degree that individuals perceive the people and places, experiences and activities in their lives are meaningful and important, in the present and for the future. Correspondingly, connectedness has two foci: a relational component and a performance/performative component.

Connectedness as a Multifactorial Construct

To date, few authors have considered connectedness as a multidimensional construct. An exception to this is the work of Brown and Evans (Reference Brown and Evans2002), who provide a definition that exemplifies a multidimensional representation comprised of the four factors of commitment, power, belonging, and belief in rules. However, Brown and Evans’ four factors are not sequential, and it is proposed that connectedness is both multidimensional and sequential, and can be separated into factors that are relational and performative. The first factor, attending, can be derived from terms highlighted in the Wingspread Declaration (Reference Wingspread2004). These include less absenteeism, higher student completion rates, and an improved school experience. The declaration also noted that connection was associated with positive adult-student relationships, physical and emotional safety, and fewer incidents of fighting, bullying, or vandalism, which are related to the second factor of belonging. Both attendance and belonging are associated with relational aspects of Barber and Schluterman's (Reference Barber and Schluterman2008) definition of connectedness. The factor of engagement, derived from the Wingspread Declaration (Reference Wingspread2004), is related to high expectations and rigour, coupled with support for learning, increased motivation, increased classroom engagement, and increased academic performance. Accepting the more expansive definition provided by the three factors summarised from the Wingspread Declaration (Reference Wingspread2004), a fourth factor that is experienced far less commonly than the previous three but emerges at times after a student attends, feels as though they belong and is fully engaged, is described as transformative or transcendent, and is the experience of flow. Flow can be considered an extension of high levels of engagement. Csikszentmihalyi (Reference Csikszentmihalyi1990) defines flow as ‘the state in which people are so involved in an activity that nothing else seems to matter; the experience is so enjoyable that people will do it even at great cost, for the sheer sake of doing it’ (p. 4). Hence, flow is the fourth factor of the proposed multifactorial model provided to comprehensively describe connectedness experienced by students in school.

School Connectedness as a Sequential Process

What is being proposed here is that the experience of connectedness can occur at various levels, each conditional on the satisfaction of the last, that is, that each of the four factors form a sequence beginning with attending. For some students, connecting to school is best described as being physically at school, being present or attending. Once a child attends physically and psychologically, they bring to the environment of the school the possibility of learning (Morrissey, Hutchison, & Winsler, Reference Morrissey, Hutchison and Winsler2014), which includes learning with and about the self and others. Socialising opens the prospect of experiencing belonging as a student (Cemalcilar, Reference Cemalcilar2010). It is difficult to conceive of a student belonging without attending in some manner, as even in situations of online learning or distance learning some presence has to occur before a person can be acknowledged. Once attending regularly, students can build identification with other students and the school, and start negotiating their space in the group and how they may belong (Strolin-Goltzman, Sisselman, Melekis, & Auerbach, Reference Strolin-Goltzman, Sisselman, Melekis and Auerbach2014). While it is possible to engage without belonging, or more likely with minimal belonging, optimal connectedness occurs when people feel as if they belong on a multitude of levels (St-Amand, Bowen, & Lin Reference St-Amand, Bowen and Lin2017). Once the need to be social and belong is satisfied, and relations are up-building and affirming, the student can relax in the environment and be free to learn and engage (Libbey, Reference Libbey2004, Reference Libbey2007). Being connected with peers, teachers and the school community by engaging in planned activities brings a wider possibility of sense of reward, especially if accompanied with achievements (Appleton, Christenson, & Furlong, Reference Appleton, Christenson and Furlong2008). Many students spend a large portion of their school life negotiating belonging, and this stage of connectedness may be dominant for them throughout their school life. Occasionally, when more engaged, when more affirmed within the community, and when fully present, the student may experience some sense of transformation or transcendance: flow (Shernoff, Csikszentmihalyi, Schneider, & Shernoff, Reference Shernoff, Csikszentmihalyi, Schneider and Shernoff2003). While a flow experience is likely to be infrequent in comparison to engagement, belonging and attending, it is possible that each time a student demonstrably strives or achieves extraordinarily well, or achieves a personal best (Hamari et al., Reference Hamari, Shernoff, Rowe, Coller, Asbell-Clarke and Edwards2016; Murcia, Gimeno, & Coll, Reference Murcia, Gimeno and Coll2008), or expands the upper level of their zone of proximal development, they may experience flow (Basawapatna, Repenning, Koh, & Nickerson, Reference Basawapatna, Repenning, Koh and Nickerson2013).

A problem in the research on connectedness is that some terms defining the hypothetically sequential factors of attending, belonging, engaging, and flow were associated with more than one of the factors. Hence, further investigation of the definition of these factors to identify the core terms most frequently associated with each separate factor is necessary. The questions to be addressed in the remainder of this paper are:

1. Is there diversity in the factors and defining terms of connectedness that conceptually supports the independence of each of the four factors — attending, belonging, engaging, and flow?

2. What is the frequency of factors defining the four factors?

3. Can the four factors be defined and can themes be developed from the content of the defining terms to support the formation of a four-factor sequential model?

Method

The method used to approach the problem of defining the model of school connectedness was a combined deductive and inductive approach, based on the general theoretical principles of content analysis (Breckenridge, Reference Breckenridge2009; Corbin & Strauss, Reference Corbin and Strauss2015), which can be considered a general inductive approach to a narrative review of literature (Green, Johnson, & Adams, Reference Green, Johnson and Adams2001; Nightingale, Reference Nightingale2009; Thomas, Reference Thomas2006). In this instance, the descriptive coding categories were identified a priori from previously published articles linking the four sequential factors of connectedness (a deductive method), and the defining of the terms associated with these four factors was an inductive analysis. According to Thomas (Reference Thomas2006) inductive analysis:

refers to approaches that primarily use detailed readings of raw data to derive concepts, themes, or a model through interpretations made from the raw data by an evaluator or researcher. . . . Deductive analysis refers to data analyses that set out to test whether data are consistent with prior assumptions, theories, or hypotheses identified or constructed by an investigator. In practice, many evaluation projects use both inductive and deductive analysis. (p. 238)

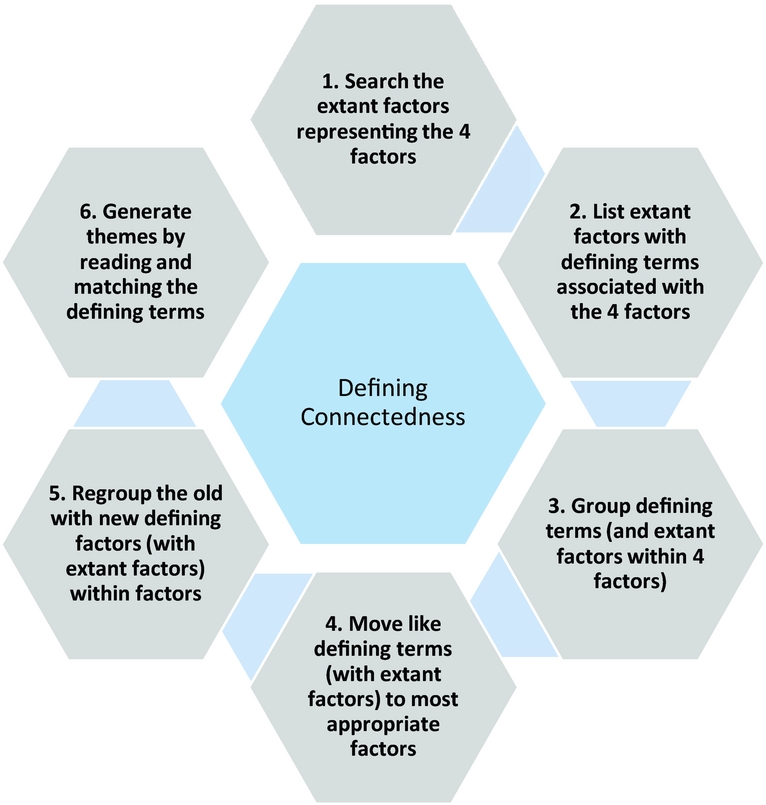

The process was one of searching for the four factors and listing the factors and defining terms associated with each from the research literature. Following the process suggested by Corbin and Strauss (Reference Corbin and Strauss2015), defining terms were resorted to, to reduce crossover in the definition of the four factors. The terms were further categorised in themes, generated by reading and matching the defining terms. Here, the field of objects were published papers and the unit of analysis was the definition (defining terms) derived from the papers associated with the four terms constituting the categorical factors — attending, belonging, engaging, and flowing. The searching process was followed by defining and sorting of the terms associated with the four factors, which was an inductive analysis. This iterative process was completed until the authors and a trained researcher achieved consensus. Any points of ambiguity were discussed until agreement was reached. This meant returning to the papers to check interpretations, and to enable the definitions of each term to be detailed and explicit (Pyett, Reference Pyett2003). This process is consistent with the recommendations of researchers in thematic analysis (Green et al., Reference Green, Johnson and Adams2001; Nightingale, Reference Nightingale2009; Nowell, Norris, White, & Moules, Reference Nowell, Norris, White and Moules2017; Thomas, Reference Thomas2006) to build trustworthiness in the approach to the sorting and management of the data. A detailed outline of the process is provided in Figure 1.

Figure 1. The process for defining connectedness.

To exemplify, searching ‘Attending’ brought up ‘school attendance’, with a defining term of ‘at-risk attendance’ from Hancock, Shepherd, Lawrence, and Zubrick (Reference Hancock, Shepherd, Lawrence and Zubrick2013). It was coded negative (-) as this was a threat to attendance. The term ‘at-risk attendance (-)’ was subsequently regrouped with theme 1, ‘at risk of chronic absenteeism’. Similarly, ‘at-risk behaviour (-)’ (Glanville & Wildhagen, Reference Glanville and Wildhagen2007) was originally a defining term of ‘Engaging’. However, this defining term was judged a better fit with ‘Attending’, as ‘at-risk behaviour’ was considered a greater threat to a ‘student's approach to routine attendance’ (Attending: theme 3) because developing a routine to attend is a precondition for engagement.

A comprehensive search strategy was conducted to identify and retrieve relevant data. The inclusion/exclusion criteria were: papers published in a peer-reviewed journal only; searches completed on the most recent published work from after 1990; papers published in English; preference given to empirical studies, although conceptual studies were considered; positive and negative outcomes included; at least one of the terms connectedness, attending, belonging, engaging and flow (or another form of the term; e.g., attend, attending, attendance) or an associated term present and defined. To ensure that sufficient depth was obtained in generating the papers, a thorough search was conducted of the following databases: ERIC, EBSCO, PsychINFO, PubPsych, Social Sciences Citation Index, ProQuest, and Google Scholar. Keyword searches within each database included combinations of keywords with appropriate wildcards. Data saturation was assumed when no new data were emerging from further data searching (Fusch & Ness, Reference Fusch and Ness2015; Marshall, Cardon, Poddar, & Fontenot, Reference Marshall, Cardon, Poddar and Fontenot2013). What to count in considering saturation varies depending on the unit of analysis. In accordance with Marshall et al. (Reference Marshall, Cardon, Poddar and Fontenot2013), when referring to phenomenological studies, saturation was shown to correspond with approximately 30 studies reviewed, and Charmaz (Reference Charmaz2014, p. 214) has recommended at least 25 interviews to claim saturation. In this research, the unit of analysis was the factor name and associated definition. As is commonly the case, some authors had multiple definitions, and some authors referred to or developed the definition of other authors, generating some overlap in the definitions. The search for independent defining terms associated with a factor found for attending (n = 32), belonging (n = 44), engaging (n = 38), and flow (n = 43), at which point saturation was achieved. Further details of the independent factors and independent defining terms are summarised in Table 1.

Table 1. Frequency Table of Independent Defining Terms of the Data Gathered

Note: 1Each factor and defining term are counted once.

Results

The Appendix shows the defining terms associated with the factors in alphabetical order within sorted themes. After grouping the defining terms and sorting them into the four factors, crossover was diminished and considerable diversity emerged with at least three themes defining each factor. Three major themes emerged for each of the factors associated with connectedness. The themes associated with attending were mainly about being present: student approach to routine attendance, disaffection and poor attendance, and at-risk and chronic absenteeism. The three themes that emerged from the terms associated with belonging were mainly about being among: positive experience of school, school-student aligned values, and positive student relationships. The third factor of engagement was also associated with three themes, mainly about being there to learn: involvement of the whole person, social support to focus on learning, and motivation and goal-direction to learn. Finally, flow is associated with being beyond the familiar, and involves: intense immersion, positive, peak rewarding activity, challenge, and achievement.

A relatively similar number of papers were distributed across the factors in this research (Table 1). Showing relative consistency was the number of independent defining terms that emerged from these papers. Fewer defining terms were apparent for attending, with more terms associated with belonging, and more again associated with engaging and flow. There was also variability in the number of factors. Interestingly, the sequential factor flow had only one factor. Belonging had five and attending had six factors. By comparison, there were 13 factors associated with engaging, possibly showing that this is the sequential factor with the greatest divergence.

Table 2 provides the summary definitions and the structure of multidimensional sequential factors of connection at school. As anticipated, the relational component is associated with attending and belonging. Performance/performative components were associated with engaging and flow. Each of the factors of attending, belonging, engaging, and flow was defined in simple terms and associated with at least three themes. So, each of the themes were independent of each other but contributed to the definition of the sequential factors. The four sequential factors defining connection were shown to be conceptually and definitionally separable and independent.

Table 2. Definition of Connectedness to School by Factor and Theme.

Discussion

In summary, in reference to the research questions, the analysis shows that the terms were quite divergent, and a core set of terms and factors could be related to each of the four sequential factors defining connectedness. The Appendix shows there was considerable variability in the number of factors associated with the four sequential factors, with a range of between 1 and 13. The 142 terms could be allocated into the four sequential factors quite readily. There was some crossover indicated by the variety of factors not being congruent with the sequential factors. This occurred because the terms were realigned with the new, sequential factors. The crossover was to be expected and was exemplified in the Hazel, Vazirabadi, and Gallagher (Reference Hazel, Vazirabadi and Gallagher2013) reference in the table, where the defining term of ‘belonging’ was associated with ‘Student school engagement’ by the authors but was regrouped to the sequential factor of ‘belonging’. While there was considerable crossover in the factors, indicating some porosity in the boundaries and definitions pre-existing in the literature, there remained a consistent core of factors and defining terms relevant to each sequential factor. This core could be categorised into three to four themes for each sequential factor of attending, belonging, engaging, and flow. It is hypothetically proposed that the factors form a sequence and a logical progression in the potential experience of students.

Attending may be characterised as being in the company of others, awareness of oneself and the context, such as school. At the simplest level it is ‘being present’. Students who are among the least connected to school are those who are at risk and experiencing chronic absenteeism, which is the first theme. These students are among the most vulnerable in the community (Sherry, Reference Sherry2010) and may be suffering from multiple problems (Kearney, Reference Kearney2008a), yet once absenteeism is habituated for the student and for the school, they become somewhat invisible and less of an apparent problem. These students are also vulnerable to at-risk behaviour (Glanville & Wildhagen, Reference Glanville and Wildhagen2007) and need specialised attention, which is difficult to provide in a standard educational setting. Uncoupling from the routines of school can open the prospect of other habits that become preclusive of returning to school. Countering truancy is very difficult, showing that factors that reinforce attendance for the majority of students does not operate in the same way for those experiencing chronic school absence (Epstein & Sheldon, Reference Epstein and Sheldon2002). However, there is a range of programs and interventions that have achieved some success in addressing truancy and chronic school absence (Maynard, McCrea, Pigott, & Kelly, Reference Maynard, McCrea, Pigott and Kelly2012). The second theme of ‘Disaffection and poor attendance’ is associated with feeling negative about school and frequent absence from school (Hancock et al., Reference Hancock, Shepherd, Lawrence and Zubrick2013) and therefore absence from routine (Morrissey et al., Reference Morrissey, Hutchison and Winsler2014) and programmatically dependent subjects, such as mathematics. This is a signifier point in connection to school and marks a need to focus attention on the specific child, which simultaneously removes anxiety and brings about discussion of the problem of non-attendance, while increasing the desirability of school as a place to be. Special attention needs to be paid to students who are vulnerable at this level so that they do not slip into school refusal. Interrupting chronic absenteeism has been shown to be related to specific types of rewards, the need to establish a contact person for parents to work with, workshops for parents and family members, and developing positive communication with families (Epstein & Sheldon, Reference Epstein and Sheldon2002).

While building relationships and working towards the next sequential factor of belonging is valuable, it is also very important to focus on the generally welcoming nature of school and how it can be a secure and non-threatening, welcoming place — at the social/relational, emotional, behavioural, cognitive, and physical levels. Once a secure environment is experienced, routine attendance can be established. Hence, the third theme of ‘Student approach to routine attendance’ is characterised by liking school (Strolin-Goltzman et al., Reference Strolin-Goltzman, Sisselman, Melekis and Auerbach2014) and attendance occurring without being overly apparent. This is the stage where attendance is not a conspicuous issue but is habituated as a positive experience, and energy can be given to participative aspects of attendance.

Belonging, like the concept of attending, had relatively similar independent defining terms and was sorted into relatively few (n = 5) factors, indicating that there was some diversity while gathering a core of factors. Belonging is dependent on the resolution of the issues associated with attending. Once a child is free of concerns and anxieties to do with attending, they start to develop a stronger awareness of ‘being with’ and a sense of relaxation and knowing that school is a sharing place of commonality with others. Hence, the first theme associated with belonging is about having a positive experience of school (Libbey, Reference Libbey2004). What draws children and people to belong varies on a number of dimensions, including gender, race, culture, and capabilities; prominent among these would be aligned interests and values, to name a few influential themes (St-Amand et al., Reference St-Amand, Bowen and Lin2017). Thus, the second theme of belonging is related to aligned values. The third theme gives prominence to positive student relations and the benefits such strong relationships might bring within school, as well as connecting the student with other families and communities (Cemalcilar, Reference Cemalcilar2010; Grier-Reed, Appleton, Rodriguez, Ganuza, & Reschly, Reference Grier-Reed, Appleton, Rodriguez, Ganuza and Reschly2012). For educational institutions, the point of belonging is to facilitate learning and the development of the whole student at least as much as emphasising social and community-building aspects of connection.

Engaging is a central issue for students in schools and is the first of the performance or performative components. There were twice as many factors associated with terms describing engaging than belonging or attending, indicating that there are many more ways of (describing) engaging and it is a more diffusely defined factor. It is the factor that forms the foundation for learning, hence it is appropriate that there is a broad array of ways of describing conceptualising and engaging in learning (Bowles & Hattie, Reference Bowles and Hattie2016). Research on engagement has focused on cognitive, behavioural and emotional engagement (Jimerson, Campos, & Greif, Reference Jimerson, Campos and Greif2003), and it is these three foundational dimensions of engagement that teachers are called upon to attend to in their teaching (Australian Institute of Teaching and School Leadership [AITSL], 2013). Maintaining a high level of engagement over a long period, linking the present and future through a task focus while at school is the first theme and is the responsibility of the student. This requires, behavioural, cognitive and emotional alignment, and engagement (Appleton et al., Reference Appleton, Christenson and Furlong2008; Jimerson et al., Reference Jimerson, Campos and Greif2003) with school values, practices and processes. The influence of families, teachers and significant others to provide role models who embody, express, and model and nurture expectations about learning is the second theme (Grier-Reed et al., Reference Grier-Reed, Appleton, Rodriguez, Ganuza and Reschly2012; Hazel, Vazirabadi, & Gallagher, Reference Hazel, Vazirabadi and Gallagher2013). Parents and the school and school staff conjointly are responsible for modelling and promoting these values, behaviours, and expectations. In many contexts, the most potentially influential and positive roles and models are the school staff and those involved in teacher-student relations (Strolin-Goltzman et al., Reference Strolin-Goltzman, Sisselman, Melekis and Auerbach2014; Wingspread Declaration, Reference Wingspread2004). The third theme is planning and motivation (Grier-Reed et al., Reference Grier-Reed, Appleton, Rodriguez, Ganuza and Reschly2012). Engaging requires planning for a student at a level at which they can be motivated to learn and assisted to understand. It is after such careful preparation and negotiation that learning can occur (Glanville & Wildhagen, Reference Glanville and Wildhagen2007) and motivation towards performance and outcomes can be maintained (Fredericks & McColskey, Reference Fredericks, McColskey, Christenson, Reschly and Wylie2012; Hazel et al., Reference Hazel, Vazirabadi and Gallagher2013). This is a conjoint space between learning, organising and creating (knowledge, objects, and performance) and is necessarily within the student and the psychological space between the student and teacher. The fourth factor of positive social engagement is about developing relationships with peers in various settings that resolve in generating greater engagement to and with the school, even though those activities may be extra-curricular or outside of school (Appleton et al., Reference Appleton, Christenson and Furlong2008; Fredericks & McColskey, Reference Fredericks, McColskey, Christenson, Reschly and Wylie2012). In short, no social relationship is frustrating or interfering with a positive level of social engagement with the student and their peers and their school, and these relations are enhancing the student's experience and level of engagement with the school and its culture (St-Amand et al., Reference St-Amand, Bowen and Lin2017). Importantly, while school education and learning is of central importance to the student, some students may be more engaged in extracurricular or out-of-school activities than school activities. Highpoints of these activities lead to levels of identification with others (past and present), the setting or physical context and the school, and provide the foundation for exceeding and transcending one's previous best performance or first experience. The object of schooling is socialisation and acculturation to allow for learning. When these things converge, there is a much higher prospect of achieving a flow experience.

Flow in the current research was typically described by only one factor — flow — and was associated with 40 defining terms, which is comparable to the other concepts. There appeared to be a confusion between the preconditions for flow and the experience of flow, prompting the need to differentiate engaging from the flow experience. Flow was associated with three themes in this research, and the first was intense immersion (Csikszentmihalyi, Reference Csikszentmihalyi1997). Positive, peak, and rewarding activity was the second theme (Clarke & Haworth, Reference Clarke and Haworth1994). The third theme was challenge and transcendent achievement level, where the achievement or performance level and the skill level are approximately equivalent (Ellis, Voelkl, & Morris Reference Ellis, Voelkl and Morris1994; Ghani & Deshpande, Reference Ghani and Deshpande1994). For flow to occur, the individual needs to be able to adapt, transform, and transcend the commonplace and see it anew in a richer and more profound fashion, allowing for both an immediate sense of positive affect and integrated and elated cognitive experience. Sometimes these are highly social events as well. Flow is an experience that is not often achieved and may provide experiences that are sustaining for decades or change the direction of someone's life. This sense of flow may be very transitory or fleeting but may be reinvoked after years, through various memories, symbols, insights, or emotions. Flow experiences are peak experiences, and in the ideal sense, it is less ego enhancing and gratifying than it is identity affirming and constructing.

The sequential aspects of the model express the transition from the individual who is alone and not connected with other students, though attending at school, to belonging, engaging and to the potential of flow experiences. The first stage suggests that students are attending and present (i.e., attending physically and psychologically: cognitively, emotionally, and behaviourally). Following the establishment and maintenance of the possibility to attend, the student may begin to belong. It is hard to belong and maintain relationships without attending. At the belonging stage, the attachment and nurturance needs are satisfied (and possibly corrected) sufficiently for the student to feel safe, secure, welcome, and valued. The security provided can permit contentment and relaxedness and an enjoyment of the security of the environment. It can also allow the student to feel energised, ready to more fully engage, and able to align with the school community, the staff, their values, intentions, and direction. To more agentically engage in most school activities an adolescent needs to focus on their learning and beyond: being present, feeling secure, being comfortable with being challenged to commit, engaging, and actively learning. Engagement is possibly as good as can be expected most of the time, for most students. Beyond this is flow, which is peak self-actualisation. The sequential nature of the relationship between these factors is hypothetical and dependent, as represented in Figure 2.

Figure 2. The sequence of four factors in the hypothesised model.

Implications of the Research for Schools and Future Research

Most specialists in schools dealing with issues associated with connectedness are helping students adjust to a process of accepting that physical (Epstein & Sheldon Reference Epstein and Sheldon2002), psychological (Strolin-Goltzman et al., Reference Strolin-Goltzman, Sisselman, Melekis and Auerbach2014), and cognitive attendance (Appleton, Christenson, Kim, & Reschly, Reference Appleton, Christenson, Kim and Reschly2006) is necessary to fully belong within the school community and to be able to fully engage and experience the possibility of flow. According to McNeely & Falci, Reference McNeely and Falci2004):

conventional connectedness involves connections to individuals who engage in prosocial behaviors and who regulate prosocial behavior in others. Unconventional connectedness, in contrast, involves connection to individuals who engage in behaviors that do not conform to prosocial norms. Thus, an adolescent's school connectedness will be conventional or unconventional depending on to whom an adolescent develops a connection. The type of connectedness will determine the direction of influence of school connectedness on health risk behaviors. (p. 291)

Unconventional, prosocial connection is worthy of further investigation, especially where schools seek to be inclusive by policy and practice, and respect and serve culturally and linguistically diverse groups, students from minority communities and those participating in alternative education systems. These principles are affirmed in inclusive education practices (Forlin, Reference Forlin2010) and multicultural policy (Australian Government, 2011). Finding a goodness-of-fit between adolescents, their school and community(ies) enhances student wellbeing, adjustment and development (Badura, Geckova, Sigmundova, van Dijk, & Reijneveld, Reference Badura, Geckova, Sigmundova, van Dijk and Reijneveld2015; Forneris, Camiré, & Williamson, Reference Forneris, Camiré and Williamson2015) and fits with SCT (Bandura, Reference Bandura2001, Reference Bandura, Van Lange, Kruglanski and Higgins2012). Once shunned by or self-alienating from an institution or group, adolescents will use similar processes to identify with and connect with alternative groups engaging in alternative and possibly antisocial behaviour (Brindle, Reference Brindle2016; Townsend, Fischer, & King, Reference Townsend, Fischer and King2007). Importantly, there is a limit to the degree of the connection an adolescent can make. Therefore, the more attending, belonging, and engaging with benign and benevolent groups and institutions that affirm prosocial and educational values that adolescents can connect with, the less time and resources adolescents have to be involved in and identify with malevolent, antisocial, and criminal groups. The more schools promote positive social support, diminish negative social support, and keep students on task to the various processes of schooling (educational, social, recreational and cultural), the better the academic outcomes (Bowles, Reference Bowles2008), which will enhance the prospect of engagement and promote the possibility of flow.

Just as connecting with school is important, so is disconnecting and leaving. Formally disconnecting from school may mean that a level of competence is reached where people can go to work or embark on another form of study or training, which is an adaptive process. Identifying stages in this process of disconnection and establishing whether it is the reverse of connection is important. It is necessary to explore the link between students who have a sense of violation as a result of association with schools (Brown, Reference Brown2007) and those who attend but want to disengage or distance themselves (Gasper, DeLuca, & Estacion, Reference Gasper, DeLuca and Estacion2012), and whether this is associated with withdrawal and self-alienation (Schulze & Naidu, Reference Schulze and Naidu2014), followed by disorientation of self (De Stasio & Di Chiacchio, Reference De Stasio and Di Chiacchio2015).

Future research investigating the definition and independence of the relationship between the four factors is necessary as the current research is descriptive. The four factors are hypothetically sequential. Future research should seek to establish (1) the level of association between sequential factors — particularly adjacent factors — through further research, and (2) the sequential or the reciprocal nature of the hypothetically sequential factors needs to be explored in future research. While this conceptual framework has been developed with reference to adolescents in schools, the concepts are directly transferable into other relationships, such as those involved in friendships, romantic relationships through to committed couples, work relationships, and social groupings. The subsequent task for researchers is to develop definitions and models of connectedness that can be tested empirically and will inform best practice in the development of interventions relevant for adolescents, particularly in schools.

Appendix Factors and Themes, Based on the Defining Terms and Exemplars, Defining the Concepts of Connectedness, and Corresponding Factors