INTRODUCTION

A cartel is an association of independent businesses for the purpose of regulating trade in an industry. This paper focuses on international cartels (ICs). It examines the relation between international cartels and multinational enterprises (MNEs).

There are three important reasons for studying ICs. Firstly, they will become important in the future (Buckley, Reference Buckley2020). MNEs have dominated post-war trade and investment because US hegemony has promoted foreign direct investment (FDI) and free trade. However, mass immigration and growing income inequality have created popular discontent with globalization. The rise of Asia and the end of US hegemony may signal a more unstable international political environment. This may lead to greater protectionism in trade and technology, and increased regulation of FDI. Whatever happens, political risks are likely to increase. The coordination of international production and R&D may rely less on the conventional MNE and more on inter-firm contractual arrangements, such as cartels. It is therefore important to understand the strengths and weaknesses of cartels. They have a reputation for sustaining economic inefficiency and inequality, so it is important to know whether such allegations are well-founded. It is also important to know if they afford distinct advantages, such as improving the management of political risks (Barjot, Reference Barjot1994).

Secondly, cartels are of immense historical significance (Fear, Reference Fear, Jones and Zeitlin2008). Their origins can be traced back to fourteenth-century guilds, and perhaps even earlier (Dollinger, Reference Dollinger1970). In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, they played a prominent role in large-scale industry (e.g., steel and chemicals) and the development of new technologies (e.g., electric lighting) (Reich, Reference Reich1992; Stocking & Watkins, Reference Stocking and Watkins1946). In the post-war era, however, cartels became illegal in most leading market economies. They were deemed the enemy of free competition. They were accused of subsidising inefficient and declining industries. It was said that they concentrated economic power in a few hands. In the 1920s, some German writers had wrongly claimed that cartels were a German invention, and so after the defeat of the Nazi state they were tainted in both economic and political terms (Piotrowski, Reference Piotrowski1933).

Thirdly, cartels are poorly understood. The classic literature on cartels pre-dates the modern economic theory of monopoly and, with one or two exceptions, the modern theory of monopoly ignores cartels. There is a large literature on monopolistic and oligopolistic firms, but cartels are normally discussed as an after-thought (Caves, Reference Caves1982). In contemporary competition policy, cartels are simply deemed bad.

Three key issues are addressed in this paper. Firstly, to what extent will increased international political risks encourage the substitution of ICs for MNEs? Secondly, will MNEs that belong to ICs be ‘less multinational’ (e.g., have fewer foreign subsidiaries)? Finally, are ICs more likely to emerge in certain types of industry than in others, and if so, what are the characteristics of these industries? Evidence on cartels is limited. Because of their secretive nature, much of what is known about cartels is sourced from historical business records, the testimony of ‘whistle-blowers’, and official investigations initiated in response to specific complaints (Spar, Reference Spar and Rugman2009).

The paper begins by defining ICs (section 2), and then examines their main activities (section 3). These two sections provide an overview of the topic. The next four sections set out the main theories of cartel behavior and consider their implications for IB. Section 4 examines the motives for establishing a cartel, while section 5 considers the different ways in which a cartel can be organized. Section 6 compares cartels with more informal alternatives, namely tacit collusion and price leadership, while section 7 examines four main types of cartel which are particularly relevant to IB. The next three sections examine important policy debates. In particular, sections 8 investigates cartel instability, section 9 examines the impact of national culture on cartel solidarity, while section 10 considers the role of interlocking directorships in reinforcing the power of a cartel. Section 11 summarizes the conclusions, with special reference to the role of cartels in a de-globalizing world.

DEFINITIONS

Cartels need to be defined with care. Because ‘cartel’ can be a pejorative term, it is often used loosely, and this has caused confusion in the literature (Mirow, Reference Mirow1982). For the purposes of this paper, an IC may be defined as a cartel whose member firms, considered as a group, operate in more than one country. This definition focuses on the location of production plants rather than the ownership of the firms. It does not require that every member of the cartel produces in more than one country, or that members are headquartered in different countries. The advantage of the definition is that if it is satisfied then a merger between the members would generate an MNE, and otherwise it would not. An international cartel may be contrasted with a domestic cartel, whose members, of whatever nationality, all produce in a single country.

Note that the members of a cartel have been defined as businesses. In the post-war period the most important cartels have been inter-governmental cartels, e.g., OPEC. Important lessons can be learned from the experiences of inter-governmental cartels, as indicated below, but they are not the main focus of this paper.

Cartels are also often discussed as if they were similar to syndicates, concerns, combines, or trusts. This is not the case. A syndicate is usually short-lived and is organized for specific speculative purposes. The aim is often to manipulate prices so that the members can buy cheap and sell dear, e.g., cornering a commodity market, or buying and re-selling shares in a company that is in the news. The members each contribute a certain amount of capital at the beginning and withdraw a proportionate amount of capital at the end.

A concern, or combine, is normally a holding company whose constituent firms are autonomous in day-to-day management and operate under independent names; their long-term strategy, however, is dictated by the concern. A trust is managed by a corporate trustee, who holds shares in various firms on behalf of others and operates these firms to maximize their combined profits. In practice, merchant banks and investment banks have often acted as trustees (Jones, Reference Jones1926; Levy, Reference Levy1911, Reference Levy1927; Liefmann, Reference Liefmann1932; Plummer, Reference Plummer1934). By comparison, a cartel is coordinated by an agreement or informal understanding between its member firms. If a cartel provides central services, such as an administrative secretariat, then members will have to pay a fee to join.

Cartels may be established on the initiative of a third party who is not formally a member of the cartel. The most common example is a government-led cartel. The motivation of the government may be to promote an infant industry, to save jobs in a declining industry, to smooth out fluctuations in trade, or to eliminate foreign competition. In times of political conflict, government-led cartels may also be established to gather and share strategic information obtained from, or relating to, hostile countries. Government-led cartels are normally confined to local producers, but these can include the subsidiaries of foreign-owned firms and also locally-headquartered MNEs; they therefore fall within the scope of this paper. Cartels can also be established on an inter-governmental basis, e.g., to stabilize commodity export markets in developing countries (LeClair, Reference LeClair2000; Schmitz, Reference Schmitz1981).

A cartel may or may not be legal. Legal activities will normally be open and illegal activities secret. Legal activities may nevertheless be kept low-profile to discourage public criticism. A cartel that carries out legal activities may be used as a ‘front’ for carrying out illegal activities too (Connor, Reference Connor2001).

Finally, certain types of cartels are excluded from this analysis; these include purchasing cartels, e.g., the UK National Health Service, which buys in bulk for state hospitals in the UK and negotiates special prices for many medical products. It also excludes trade unions and professional bodies that negotiate wages and salaries on behalf of their members.

MAIN ACTIVITIES OF CARTELS

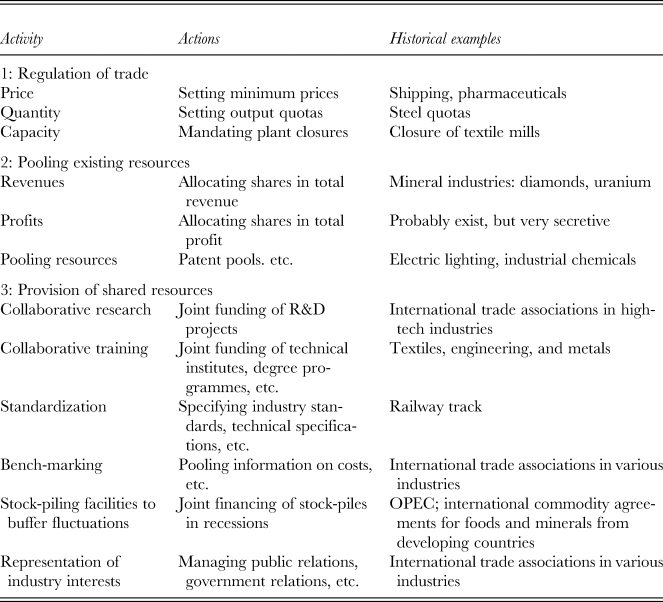

Cartels are very versatile (Mariti & Smiley, Reference Mariti and Smiley1982). Table 1 identifies three main types of activity that cartels can perform: the regulation of trade, the pooling of existing resources, and the provision of shared resources.

Table 1. Summary of cartel-related activities

Regulation includes price-fixing, quantity-fixing, and capacity-fixing. Price-fixing is the pre-eminent cartel activity (Connor, Reference Connor2005). Quantity-fixing involves setting production quotas; while price-fixing sets minimum prices, quantity-fixing sets maximum outputs. Capacity-fixing is used to reduce spare capacity and reinforce limits on production.

Pooling includes revenue pools, profit pools, and patent pools. A revenue pool aggregates the sales revenues of all member firms and then divides the revenues between the firms in agreed proportions. These proportions will generally reflect historical market shares. A profit pool divides the total profits of member firms in agreed proportions. A profit pool may appear unduly generous to high-cost firms, but this is not necessarily the case if the profit shares are based on historical levels of profit. A patent pool is rather different. It allows each member to produce a full range of products using the patented technologies of other member firms; it is most attractive when protectionism constrains competition, so that each member dominates their own local market. A patent pool may be regarded as a collection of cross-licensing agreements (see below).

The provision of shared resources includes drawing up and enforcing industry standards, and is particularly important in the chemical, pharmaceutical, engineering, and information technology industries. It also includes joint funding of industry research facilities, technical education for employees, and the financing of stock-piles to even out fluctuations in demand and ensure against disruptions to supply. It may also include political lobbying on behalf of the industry. Some of these roles are also performed by international trade associations.

MOTIVATION TO ESTABLISH A CARTEL

According to the economic theory of cartels, the objective of cartel members is to maximize profits (Casson, Reference Casson, Buckley and Casson1985; Marshall & Marx, Reference Marshall and Marx2012). Profit-maximizing firms have no incentive to join a cartel unless they can make higher profits inside the cartel than outside it. A necessary condition for this is that the cartel increases the total profits made by the membership as a whole.

The specific form that profit motivation takes depends on the context in which the cartel operates. Cartels emerge at certain times and places and not others. What triggers a belief that an opportunity to form a cartel exists in an industry? Three main sets of motives have been identified: predatory, precautionary, and progressive.

The predatory view predominates in discussions of US trusts. This literature often equates a trust with a cartel. Trusts and cartels were particularly common in the US railroad and steel industries (Hexner, Reference Hexner1943, Reference Hexner1945). Economic analysis of cartels tends to adopt this predatory view (Epstein, Reference Epstein2008; Whittlesey, Reference Whittlesey1946). Members of a cartel use their monopoly power to maximize collective profit, and then distribute this collective profit amongst themselves. It is usually assumed that the pursuit of profit is purely selfish, although this not necessarily the case. Medieval merchant guilds, for example, operated as cartels; but they also funded charities, and their leading members often invested in urban infrastructure that was free to all, e.g., building and repairing city walls (Casson & Casson, Reference Casson and Casson2019).

The precautionary view predominates in discussions of European cartels. The rise of Germany 1870–1914, and the aftermath of World War I, destabilized European political boundaries. Industrial heartlands bordering the River Rhine changed hands several times, and the Austro-Hungarian Empire disintegrated. Trade and technology transfer needed to be coordinated in a climate where FDI was insecure and trade could be disrupted. Cartels helped to sustain elite business networks, and provided the flexibility required to adjust the international business system to changes in the political order (Barbezat, Reference Barbezat1989; David & Westerhuis, Reference David, Westerhuis, da Silva Lopes, Lubinski and Tworek2020; Matis, Reference Matis, Teichova and Cottrell1983; Nussbaum, Reference Nussbaum, Teichova, Levy-Leboyer and Nussbaum1986; Teichova, Reference Teichova, Teichova and Cottrell1983; Wurm, Reference Wurm1989)

The progressive view is reflected in the literature on patent pools, R&D collaboration, and trade association activities (Casson, Pearce, & Singh, Reference Casson, Pearce, Singh and Casson1992; Jones, Reference Jones1922; Luz, Reference Luz2006). According to this view, cartels resemble clubs that provide ‘public goods’ that are shared amongst their members and financed from membership fees. These activities can stimulate innovation, promote best-practice, improve labor skills, and thereby raise productivity within an industry.

Advocates of the predatory view generally focus on the marketing activities of cartel members, arguing that their prices are too high, while advocates of the precautionary view focus on production, arguing that excess capacity is the major problem. These two issues are closely connected, because prices affect quantities sold, which in turn affect capacity utilization. Advocates of the progressive view take a longer-term perspective; they focus on the greater efficiency of industry-wide R&D due to the reduction of competitive replication of funded research.

In practice many cartels have had multiple motivations, which have evolved over time (Levenstein, Reference Levenstein2006). The typical industry life cycle begins with a small number of pioneering firms that establish early leadership in a new industry. They are typically based in advanced economies. Their success encourages new entry. The number of firms increases, but as the rate of growth of the market diminishes, so competition begins to weed out smaller and less-efficient firms. The few remaining firms dominate a large and profitable oligopolistic industry. They can exploit economies of scale and use their ‘deep pockets’ to discourage further entry (see below). But then conditions change for the worse. There may be a threat of war, a recession, popular hostility, or oppressive regulation. Precautions must be taken: production is scaled back, and possibly re-located. There may also be a threat of technological obsolescence and exhaustion of natural resources. Research and exploration are required to revitalize the industry, but profits are low, so the costs must be shared. The leading firms realize that a cartel would be more profitable than competition. They form a cartel and become predators, buying up smaller, older, and inefficient plants cheaply and closing them down. If the cartel can mobilize political support, then its members can continue to earn monopoly profits and share them amongst themselves. Eventually obsolescence may take its toll, demand may shrink, the cartel may lose its power, and the firms may close.

In catch-up countries the sequence may be different. Research comes first, followed by imitation of leading producers. Once catch-up is achieved, the older producers may invite the newer producers to join their cartel in order to neutralize potential competition. But the new producers may prefer to maintain their momentum and overtake the old producers. In this case, the newer producers may form their own cartel. They take over the predatory role from the older producers and the industry cycle begins again.

INTERNAL STRUCTURE OF CARTELS

While most scholars explain the successes and failures of cartels in terms of the rise and decline of the markets they attempt to control, others believe that the institutional efficiency of the cartel itself is key; this depends, amongst other things, on its internal management structure (Spar, Reference Spar1994).

Communication within a cartel may be centralized or decentralized, or both. In a centralized cartel there is a single communication hub; each member is connected to other members only through this hub. In a decentralized cartel, members can communicate directly with each other and initiate debates within special-interest groups. Centralized communication suggests centralized authority (Levenstein, Reference Levenstein1995). In practice, however, centralization can be democratic as well as autocratic. Members can hold regular meetings where they debate in plenary sessions; they do not have to concentrate authority on the secretariat.

Each member of the cartel may own their own business outright. Alternatively, they may be involved in partnerships with other members of the cartel. These partnerships could involve joint ventures (e.g., research projects) or partnerships (e.g., in private banking and professional services). In practice it is often difficult to determine the boundaries between a conventional cartel, a network of inter-locking joint ventures, and a professional services firm coordinating the activities of a number of local professional practices (Casson & Cox, Reference Casson and Cox1993; Etemad, Reference Etemad and Boyd1995; Friedman & Kalmanoff, Reference Friedman and Kalmanoff1961).

Theory suggests that cartels in each of the three categories discussed above will tend to adopt specific organizational forms. Regulation of sales and output will tend to be centralized and to employ a large secretariat. The same applies to revenue pools and profit pools. Patent pools, however, will tend to be more decentralized; members are normally fewer, and there may be technical issues that need to be resolved through one-on-one discussion with other patentees. The provision of shared resources involves a wide range of issues, some of which can be settled centrally, while others require small-group meetings; centralized and decentralized networks may therefore co-exist within the same cartel.

Because of the secrecy that surrounds many cartels, it is difficult to find reliable evidence on these issues. The limited evidence that is available suggests that these conjectures are sound, although much of the available evidence relates to domestic rather than international cartels.

TACIT COLLUSION AND PRICE LEADERSHIP

Tacit collusion can replicate the outcome of a cartel without direct communication between firms. The firms need to be able to observe each other's actions, and to possess sufficient background information on the industry to interpret each other's actions very easily (Cubbin, Reference Cubbin1973).

The main mode of collusion involves a form of ‘tit-for-tat’ behavior. Each firm demonstrates to the others that its behavior follows a simple rule: typically to match the lowest price set by any member firm. The threat of this action is normally sufficient to deter price cutting in the first place. Someone needs to initiate the pricing process, however. This will normally be the largest firm, or the firm with the ‘deepest pockets’. They act as leader and set their price at a level they believe approximates to the monopoly price, i.e., the price that maximizes industry profit. As a large firm with deep pockets, they are in a strong position to punish anyone who does not follow the rules.

This price leadership mechanism suggests that a cartel may not need an absolute monopoly of an industry in order to exercise market power. The rational response of a non-member firm may not be to undercut the cartel, but to shelter under its ‘price umbrella’. It cannot afford to undercut the cartel because the cartel has deeper pockets and can force it into bankruptcy with a punitive price-cut of its own. In some industries there is a ‘fringe’ of such firms, e.g., small firms catering for minority niches or local customers.

It is possible for there to be two cartels in the same industry. There would be a strong incentive for them to merge, but cultural differences could create a problem. There is some evidence that Asian cartels and European cartels in the same industry have preferred to maintain their independence, whilst coordinating their actions by tacit collusion or secret agreement between them.

PROMINENT TYPES OF CARTELS

Four main types of IC have been of particular historical importance and have been documented more than others. Each type is prominent in particular industries.

Price-Fixing Cartel

Economic theory indicates that a price-fixing cartel has an important role in an industry where one or more of the following five characteristics occur (Asch & Seneca, Reference Asch and Seneca1975). Firstly, the price elasticity of demand is low, so that the scope for achieving monopoly profits by raising price is high. Secondly, individual products are very close substitutes for each other (so that price competition between suppliers is potentially intense). Thirdly, demand is atomistic, i.e., there is no major buyer that can directly influence the price, and so there is no counter-vailing power. Fourthly, there are substantial economies of scale. Finally, fixed costs are sunk, e.g., producers use highly-specific durable buildings or equipment which have no alternative use. The more of these characteristics that apply, the greater the potential for profitable cartelization of the industry.

Economies of scale play two roles in cartel theory. With economies of scale the marginal cost of production is lower than the average cost. Short-term competition such as a price-war will drive down price to marginal cost, and because it is less than average cost firms cannot break even; price maintenance is therefore essential for a sustainable industry equilibrium. Secondly, economies of scale mean that the optimal size of a plant is very large compared to industry demand, so there will be few plants in the industry. This implies few firms, which makes a cartel easier to organize; negotiation is easier, and so is the enforcement of an agreement.

Sunk costs make established firms reluctant to withdraw from an industry when new firms enter, because they cannot recover their fixed costs (Connor, Reference Connor, Everett and Jenny2012). Furthermore, sunk costs increase the risks faced by an entrant, because they cannot ‘get their money back’ if entry fails. Both these factors favor the established firms in an industry.

The situation is well illustrated by the shipping industry (Deakin & Seward, Reference Deakin and Seward1973). Consider two shipping lines, headquartered in different countries, operating a service between these two countries. A ship is a floating container and therefore exhibits significant economies of scale. Suppose that ships of both companies are in the same port at the same time, and that each ship is big enough to carry all the trade. Independent shippers turn up at the port and ask for the best terms from each line. Each believes that if it undercuts the other by just a small amount then it will get all the trade. It repeatedly fails to anticipate that their price cut will be immediately matched by their rival.

In the absence of a cartel, the price-cutting process will stop only when price becomes so low that one of the lines withdraws from the trade. This happens when the price falls to the opportunity cost of the space required on the ship. If there is plenty of capacity, then this will be close to zero. At this price neither line can cover its full costs and both will go bankrupt unless the price is quickly raised. If they are to survive, they need to make an agreement. In the absence of a merger the main option is a cartel. This could take three main forms.

Firstly, they could share the traffic between them. They would behave as a pure monopolist and set their rates where marginal revenue equals marginal cost. If their marginal cost were zero then their rates would be set where marginal revenue is zero, which is the point at the elasticity of industry demand is equal to one.

Secondly, they could agree to pool their revenues or their profits. Sharing revenues will benefit the line with the lower average cost, while sharing profits will benefit the line with higher average cost.

Finally, they could dispose of one of the ships; this would reduce their combined operating costs and generate additional revenue if the ship disposed of has salvage value. In this case they will share the revenues or profits from the remaining ship.

This example fits the facts very well. Cartels known as ‘shipping conferences’ have existed from the nineteenth century onwards, and probably before. They were a feature of the international shipping industry around the turn of the twentieth century and even more so during the inter-war trade depression. The conference system brought stability to the shipping industry. But where regulation was weak, rates could be excessive, increasing transport costs and inhibiting international trade (Wilkins, Reference Wilkins1970, Reference Wilkins1974).

Quantity-Fixing and Capacity-Fixing in a Declining Industry

A cartel can ‘manage’ the rationalization of a declining industry by eliminating excess capacity in an orderly way. Competition can also rationalize an industry by driving down prices and forcing high-cost plants to close. But plant closures can have serious social and political impacts. Mass unemployment may generate unrest, and some countries may cease to be self-sufficient in strategic products. This is characteristic, for example, of the steel and heavy chemical industries, where large plants are concentrated in coastal conurbations.

Cartels can therefore respond to political mandates to decelerate decline in key industries (LeClair, Reference LeClair2000). However, simply maintaining prices will encourage more production rather than less, and so output quotas must be applied. Prices are maintained high, but companies are prevented from producing more than is allowed. Negotiating quotas is, of course, a difficult task, but the basic principle is clear; everyone who needs a quota should have one, however small their quota may be.

There may be provisions for quotas to be traded between members of the cartel. For example, a state-owned firm could sell off its production quota and use the proceeds to create new jobs for redundant workers. A suitable buyer would be a low-cost firm that could profit from the sale of additional output.

Licensing a Patent to a Network of Licensees

This example is taken straight from IB theory (Buckley & Casson, Reference Buckley and Casson1976). Consider a manufacturing firm that has developed a new branded product incorporating an advance in design or technology. The market for the product is potentially global. The firm needs to establish a global network of regional production and distribution facilities. The firm lacks knowledge of local markets and believes that foreign ownership of production is risky. It therefore licenses its technology to a group of independent local firms, who produce and sell the product on its behalf. Each licensee is offered a local monopoly, and in return they pay a lump sum for access to the technology and a small charge for each unit produced. The actions of the licensees are coordinated through a licensing ‘cartel’ operated by the firm.

Each licensee will typically have an incentive to export to nearby markets. Reciprocal market invasions by licensees will depress local prices; however, if this is foreseen by potential licensees then it will reduce the prices that they are willing to pay for their licences. To maintain the value of the licences, therefore, the cartel leader must enforce rigorous export restrictions. In addition, the licenses may attempt to sell unbranded varieties of the product, for which they pay no fees, or even to sell under their own brand names instead. The cartel agreement must rule this out as well. The licensor must then enforce these restrictions with the utmost rigor.

Patent Pooling

Suppose that a new product is produced using a combination of technologies owned by different firms headquartered in different countries (Reich, Reference Reich1992). These technologies may relate to sequential stages in the production of a conventional product (e.g., chemical refining) or modular elements incorporated into a multi-component product (e.g., automobiles). When each technology is governed by a separate patent, the patents must be pooled in order to produce the product. In principle, one firm could buy up patents from the others. But political pressure may demand that an international licensing agreement is negotiated, in which each firm licenses the others to use its technology. This is, in effect, a world-wide patent pool sponsored by a group of governments in developed countries. Pooling of this kind was common in high-technology industries in the period 1890–1939.

CARTEL INSTABILITY

This section examines the factors which influence the stability, or longevity, of cartels. There are three main schools of thought. The first regards cheating as an endemic problem in a cartel and argues that in the long run cartel failure is the norm. The second emphasizes industry characteristics – especially barriers to entry – and suggests that cartels in certain types of industries are inherently more stable than others. The third highlights the internal organization of the cartel as a major determinant of its stability.

Cartel Cheating and Its Control

Some economists argue that cartels are fundamentally unstable. By inflating profits through restrictive agreements, cartels attract entry. Entry increases capacity in the industry, putting downward pressure on prices. Furthermore, by inflating prices cartels increase the incentive for members to cheat by under-cutting each other.

If members cannot trust each other then there is little point in them belonging to a cartel. Firms that join a cartel will eventually discover this problem, it is argued, and will then leave. Secrecy may be difficult to sustain once firms begin to leave. Firms that quit, for whatever reason, may ‘expose’ the cartel to politicians and the public because they no longer have any incentive to protect its secrecy.

The key assumption behind this argument is that cheating is difficult to detect. The evidence does not support this view, however. Some cartels have survived for many years (Dick, Reference Dick1996; Grossman, Reference Grossman2004). Cheating is not a simple matter. The symptoms are relatively easy for other members to discern (e.g., an unexplained fall in prices). Once the cartel has initiated a search for the culprit, detection may be straightforward, and so the long-run risk of cheating for a member may be high.

Furthermore, expulsion from a cartel can be very costly if it means expulsion from the industry too. In some industries, such as diamonds and other precious metals, the cartel price is far above the competitive price. Under these conditions the cartel offers its members a secure profit and a quiet life, while cheating, though it offers bigger short-term profits, does so only with a long-term risk of losing profit altogether.

Cartels have been proactive in discouraging cheating. Price cutting has been deterred by channelling sales transactions through a marketing board, or sales syndicate, which invoices customers on a member's behalf. The cartel may establish a central secretariat which is staffed by people who are employed directly by the cartel rather than by people seconded from member firms. Members may be required to deposit funds in accounts from which fines can be taken; members will consent to this so long as they trust the cartel administration more than they trust their fellow members. The ultimate punishment for price cutting is expulsion, but this may be counter-productive if it creates an external competitor for the cartel.

It is also possible for cartel members to cheat on quality. Unlike a normal competitive market, this does not involve offering an inferior good for a regular price but offering superior quality for a regular price. This effectively undercuts the agreed ‘quality-adjusted’ price. Cartels have addressed this issue by specifying different standards of quality and setting a separate price for each. In early steel cartels, for example, numerous grades of steel were identified, each of which had its own price.

Barriers to Entry as a Stabilizing Factor

There are three main barriers to entry that can affect cartel stability: economies of scale, excess capacity, and specific privileges.

Economies of scale at the plant level require entry on a large scale. This creates an ‘indivisibility’ problem: an entrant runs a risk of pushing the industry from shortage of capacity to excess capacity in a single step. Large scale may also create a financing problem; an entrant with limited reputation may find it difficult to raise capital in order to fight their way into a cartelized industry. High sunk costs also create additional risks, as noted above.

Excess capacity discourages entry because entry would aggravate an existing problem. This factor is particularly relevant during economic depressions.

Specific privileges may accrue to cartel members. Firstly, they may have privileged access to a patent pool which has been created through a comprehensive cross-licensing agreement. As a result, an entrant would have to ‘steal’ the patents or gain access to some alternative technology. Secondly, one of the cartel members may have exclusive access to the only known sources of some input, such as a rare mineral, and they may agree to restrict supply to members of the cartel. Finally, inter-governmental patronage may restrict membership of a cartel to established ‘national champion’ firms; this is particularly likely in ‘strategic’ industries such as defence equipment, chemicals, and explosives.

Credible Leadership and Competent Administration

Finally, it has been suggested that there are no clear inter-industry patterns in cartel stability and that the answer to the question of stability lies in the internal organization of the individual cartel. Cartels endure, it is said, when they have competent leadership and effective succession. Cartels need a leader to establish an organization that firms are keen to join. The leader may be a person or an institution, e.g., a dominant firm, a merchant bank, or the government of some powerful country. The leader must be trusted. They must possess sufficient credibility to persuade the major producers to join, so that others will join as well. The cartel must include all the significant producers, though not necessarily the competitive fringe (see above).

The evidence supports the importance of leadership (Spar, Reference Spar1994, Reference Spar and Rugman2009). Many successful cartels were established by individual entrepreneurs who promoted their ideas to the managers of other firms. These entrepreneurs were typically members of a cosmopolitan social elite and were often connected with the bank that financed the cartel (Maclean & Harvey, Reference Maclean and Harvey2006).

A large successful cartel may become so influential that it becomes difficult to keep its existence secret and to defend it against public criticism. A cartel leader must have the appropriate social contacts to lobby politicians to persuade them not to intervene. In practice their message may be well received because politicians may have more pressing problems on their hands, e.g., a global recession.

Remarks

None of the theories above can explain cartel stability on its own, but together they offer a reasonable explanation of variations in cartel stability between firms and industries. Where industries produce standardized homogeneous products it is relatively easy to monitor price and quality, and so cartel agreements are easy to enforce. In industries with economies of scale, established firms have a strategic advantage over potential entrants which makes their position relatively secure. Cartels with effective leaders can develop sophisticated management structures and can anticipate and counter systemic threats to survival. The evidence is piecemeal but is broadly consistent with the view.

NATIONAL CULTURE AND CARTELS

It has often been noted that the proliferation of domestic cartels is significantly higher in some countries than in others. Germany is often regarded as the home of modern industrial cartels, while Japan's sogo sosha trading companies, Italian ‘business groups’, and the Sicilian Mafia have also been likened to cartels (Graham, Reference Graham and Boyd Gavin1995; Tilton, Reference Tilton1996; Yonekawa & Yoshihara, Reference Yonekawa and Yoshihara1987).

The US, on the other hand, is usually perceived as ideologically committed to competition, transparency, and respect for law, all of which encourage opposition to cartels (Freyer, Reference Freyer1992). Nevertheless, in the ‘gilded age’ at the end of the nineteenth century, Wall Street financiers and railroad barons presided over large trusts. The populist response, however, was to condemn these trusts, and since the 1920s US anti-trust policy has consistently opposed cartels and championed the right of the ‘small businessman’ to enter any industry. UK policy has been more ambivalent. In the late nineteenth century, London became the financial centre for a number of international cartels exploiting the resources of the British Empire, but after the end of World War II support for trusts waned as the Empire declined, and more attention was focused on consumer protection.

In Germany and Japan, cartels have been strongly represented in innovative industries. Cartels can help avoid wasteful duplication of R&D, as noted above. They allow each firm to work continuously on the improvement of its product range, without undue concern for its rivals (Schroter, Reference Schroter, Teichova, Levy-Leboyer and Nussbaum1986). In the US and UK, however, innovation has tended to be regarded as a highly disruptive process, in which a radical innovator enters an industry and renders existing technologies obsolete. Under this scenario, cartels deter innovation by keeping innovators out.

Some of these differences can be explained in purely economic terms. For example, the UK was a leading country and Germany a catch-up country before World War I, while the US was a leading country and Japan a catch-up country after World War II. But not all differences can be explained in this way; e.g., the US was also a catch-up country in the late nineteenth century but it followed a very different approach to Germany. Residual differences can be explained in cultural terms (Connor, Reference Connor2001). In Germany and Japan, it has been suggested, senior management believes that the value of a product is intrinsic; it resides in the technology and skill embodied in its production. Managerial ambition is to win the respect and the trust of other firms. In the US and UK, on the other hand, managers believe that the value of a product resides in customer perception, and not in the integrity of the product itself. They strive to win the respect of customers by giving the customers what the customers think they want, and to out-wit competing firms in doing so. Competition for customer satisfaction is therefore key, and the attitude to other firms can be disrespectful.

The consequence, it is suggested, is that in Germany and Japan firms cooperate in pursuit of technical excellence, and the consumer is rewarded with a product that is intrinsically high-quality. Its price reflects this intrinsic value. It is set by the producers because they are the experts. In the US and UK, however, the customer is the expert, because only they know what they want, whatever the ‘intrinsic quality’ may be. Other producers are ‘the enemy’, because they steal market share by flattering the customer. The conclusion, therefore, is that it is more natural to cooperate with fellow-producers in Germany and Japan than it is in the US and UK (Wurm, Reference Wurm1993).

CARTELS AND CONSPIRACY

Conspiracy theories of cartels have always been popular and deserve to be taken seriously. The principal accusation is that many cartels have, in practice, been controlled by a small and secretive ‘financial elite’, e.g., major industrialists or merchant bankers and their family dynasties. The specific allegation is that at various times individuals from such elites possessed major shareholdings in several leading firms in the same industry, and held inter-locking directorships, through which they promoted solidarity within the cartel. Evidence for this is strong for the US ‘gilded age’ at the end of the nineteenth century, and for Germany and Austria in the early twentieth century (Grou, Reference Grou1985; Kotz, Reference Kotz1978; Mackay, Reference McKay, Teichova, Levy-Leboyer and Nussbaum1986; Maclean & Harvey, Reference Maclean and Harvey2006; Scott, Reference Scott, Mizruchi and Schwartz1987).

The same may be true today, but the evidence is incomplete. Holding companies controlled by elite groups certainly have substantial shareholdings in leading companies in some industries. Elite groups do not need majority ownership to exercise control; they simply need to be dominant shareholders. The more highly leveraged the firms in which they invest, the easier it is to gain control of them with a relatively modest equity stake.

This concentration of power applies today in the ownership of brands. Public information from company websites and private information from market research consultancies shows that in fast-moving consumer goods industries multiple bands are often owned by the same company, giving dominant firms national market shares of over 50 percent in many large countries. The globalization of brands in recent years has extended this concentration of market power to international markets too.

Mineral industries have always been prone to concentration of market power because rare minerals are found in only a few locations (British Columbia, 1980). Furthermore, certain precious minerals, such as gold, silver, and diamonds, derive their value almost entirely from their scarcity, which is maintained through the control of global mining output using cartel-like agreements. The De Beers cartel, for example, is infamous for having restricted the supply of diamonds for over a century in order to maintain their value, despite the discovery of new deposits, most recently in Russia (Bergenstock, Deily, & Taylor, Reference Bergenstock, Deily and Taylor2006). However, the extensive use of off-shore holding companies and other financial intermediaries makes it difficult to determine how far such arrangements persist today.

DISCUSSION

Why Cartels Have Received Little Attention in IB Theory

Although they are an ‘alternative contractual arrangement’ to the conventional MNE, cartels have not, until recently, been considered seriously as a strategic option in IB. There are three main reasons why ICs have been studied so little in IB theory. Firstly, the concept of a cartel was tainted by their behavior in the inter-war period and was not acceptable to post-war politicians and regulators. However badly MNEs may have been regarded in the early post-war period, they were deemed preferable to cartels. Cartels are, however, usually good for their members, if not for their customers, and they therefore need to be taken seriously. Furthermore, not every type of cartel is bad; because they rely on monopoly power, they need to be regulated in the public interest, but they do not necessarily need to be banned.

Secondly, cartels are complex and difficult to study. Because they are very versatile, they can take a variety of forms. There are several possible motivations and many different activities that can be performed. The motivations for cartels have varied over time. In peace-time the emphasis has been on predation, and in war-time on precaution. Technological differences mean that industries vary significantly in the suitability of cartels. There are also differences between countries, which reflect national culture and stages of development. Mature industrialized countries with a culture of individualism tend to develop predatory cartels while catch-up countries with a more cooperative culture tend to develop progressive cartels. As a result, a negative view of cartels tends to prevail in mature individualistic countries, and this has influenced modern economic analysis of cartels.

Thirdly, cartels tend to be secretive, and the greater the threat of regulation the more secretive they become. It is widely believed that post-war competition laws effectively ended cartels (see above). In practice some have obtained government endorsement (e.g., international commodity agreements) and others have ‘gone underground’. The most successful post-war cartels are almost certainly the ones that customers are unaware of and that regulators do not know about.

What Is the Future for International Cartels?

As the global economy and its governance changes over the next decade, cartels may well become influential once again. Three key questions were raised in the introduction. Firstly, will increased political risks encourage the substitution of ICs for MNEs? Secondly, will MNEs that belong to ICs be ‘less multinational’ than before (e.g., have fewer foreign subsidiaries)? Finally, are ICs more likely to emerge in certain types of industry than in others and, if so, what are the characteristics of these industries?

The preceding analysis provides answers to these questions. The answer to each of the three questions is a qualified ‘Yes’. The key difference between a cartel and an MNE lies in the ownership rather than the location of production. A cartel can coordinate two plants in different locations that are owned by different firms. An MNE coordinates two such plants by bringing them under common ownership and control. FDI is the crucial difference: an MNE requires it, but a cartel does not.

When there is political stability, FDI may be superior to licensing, but instability can raise the costs of FDI and make licensing profitable. Political instability therefore encourages the substitution of cartels for MNEs. Political instability may increase tariffs, and war may be even more disruptive. This creates existential uncertainty, e.g., about where the political boundaries of the future will lie. The disintegration of the international political system encourages firms to ‘dis-intermediate’ the politicians and implement their own independent system of inter-corporate governance. Although firms may distrust their competitors, they may distrust the political system even more. Under such conditions an IC can provide a network of communications that allows firms to manage international supply chains and retain access to markets through partners within their cartel. Some ICs may operate within the boundaries of existing political alliances, but some may transcend them because they are unsure where future boundaries will lie.

Political instability may affect some industries more than others. In high-technology defence industries, for example, governments may organise domestic cartels of local firms to manage capacity and supervise intermediate product flow within the industry. In other cases, such as shipping, cartels may be replaced by direct government control. ICs may be harnessed by governments to carry out industrial espionage and steal technology from other foreign-owned firms within the cartel (Casson, Reference Casson2020).

Overall, therefore, the incentive for a firm to de-globalize depends mainly on the increasing strength of the precautionary motive described above. In a modern context this involves a change of emphasis in the progressive motive from consumer product innovation to innovation in defense equipment, cyber-security, and energy security. This suggests a reversion to the types of cartels that emerged in the inter-war period. Other people have arrived at the same conclusion, but by a different route.

The analogy with the inter-war period needs to be qualified, however. The initial conditions are not the same: the state of the international economy in 1914 was different from today. The obvious difference is that the MNE was barely recognized as a form of business organization in 1914, whereas it is almost ubiquitous today. The leading economic powers in 1914 – the UK and US – shared a common cultural heritage, unlike the US and China today.

Although de-globalization will be driven by political risks, just as it was in the inter-war period, the risks will be different from before. War in Europe and the Atlantic was the driver of change in the inter-war period. War seems less likely today, because physical conflict will probably be replaced by economic and cyber ‘warfare’, but no one can be sure.

Wider Implications for the Future of IB Research

If IB researchers are to retain their reputation for policy-relevance, they must engage with the issue of institutional responses to globalization, and this must include the analysis of cartels.

Cartels are an industry-wide phenomenon rather than a firm-specific phenomenon. The concentration of production on a few leading firms makes industrial cooperation easier. Much IB theory remains focused on the individual firm. It analyzes monopoly and competition but pays limited attention to the oligopolistic industry structures that often generate cartels.

Cartels cannot be studied without reference to wider literature on economics, politics, and sociology. Economic principles explain why cartels tend to be more common in some industries than others. Political theory analyzes the stability of inter-governmental relations, which is crucial for cartels. It also explains the attitudes of politicians towards cartels. Sociology explains how differences in national culture generate international differences in cartel policy. It also explains the social processes that reinforce shared economic interests in maintaining cartel solidarity. IB must engage more strongly with other social sciences if it is to provide a fully satisfactory analysis of cartels.

Target article

Multinational Enterprises and International Cartels: The Strategic Implications of De-globalization

Related commentaries (2)

Comments on ‘Multinational Enterprises and International Cartels: The Strategic Implications of De-gobalization’ by Peter J. Buckley and Mark Casson

The Not So Brilliant Future of International Cartels