The COVID-19 pandemic has disproportionately affected Hispanic/Latino (H/L) persons in the United States.Reference Macias Gil, Marcelin and Zuniga-Blanco1 In Washington state, both rural and urban H/L persons have experienced disproportionate morbidity and mortality due to COVID-19.Reference Baquero, Gonzalez and Ramirez2 Food production industries including meat processing and the agricultural sector, in which H/L workers are overrepresented, have high-density, close-proximity workplace settings, increasing the risk for transmission of SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19.Reference Waltenburg, Rose and Victoroff3, Reference Selden and Berdahl4 Washington state’s Chelan-Douglas Health District (CDHD) is an agricultural community where 30% of the population is H/L. The area also experiences a large annual influx of H/L seasonal agricultural workers. By September 2020, the COVID-19 incidence rate among the H/L population was eight times that of the non-H/L population.5 A Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) team was invited by CDHD and the Washington State Department of Health to investigate the disparity. As part of their approach, CDC, in collaboration with CDHD and their partners, conducted two concurrent Community Assessments for Public Health Emergency Response (CASPERs), one among H/L and another among non-H/L households, to assess similarities and differences between the two primary demographic groups in the community. CASPER is a two-stage cluster sampling method designed to provide timely, inexpensive, and representative household-based information.6 The CASPERs aimed to identify the following for both H/L and non-H/L populations: 1) essential services employment and ability to telework, 2) beliefs regarding prevention strategies and their adoption, 3) engagement in behaviors that increase COVID-19 exposure risk, 4) COVID-19 vaccine acceptability, and 5) household needs because of the pandemic.

Methods

We conducted the CASPERs during September 25-28, 2020, in Wenatchee and East Wenatchee, adjacent cities and county seats of Chelan and Douglas Counties; we administered the same questionnaire in person in English or Spanish depending on the household language preference. We analyzed data independently to compare the 2 CASPERs. This activity was reviewed by CDC and conducted consistent with applicable federal law and CDC policy.7

We used standard CASPER two-stage sampling methodology based on 2010 US Census Data.6 One CASPER selected from H/L census blocks (CBs), defined as ≥50% of households having ≥1 H/L house member (“H/L-CBHs”), and another from non-H/L CBs (<50% of households having ≥1 H/L house member [“non-H/L-CBHs”]). At the first stage, 30 CBs were selected with probability proportional to the number of households. At the second stage, field interview teams systematically selected 7 households to interview within each selected CB. The sampling frame for the H/L-CBHs CASPER included 1937 occupied households in Wenatchee and East Wenatchee meeting the above criteria; the sampling frame for the non-H/L-CBHs included the 24 267 occupied households in the 2 cities. Each CASPER had a target of 210 interviews. Interview teams attempted to contact an adult resident (≥18 years of age) in each selected household by knocking on the door or ringing the doorbell for 3 separate attempts before substituting another household. They were instructed to prioritize personal safety and use their best judgment when approaching houses, including being cognizant of no trespassing signs and aggressive animals.

The 2-page CASPER questionnaires included identical questions on demographics; health access; COVID-19 knowledge, attitude, practices; and COVID-19 experiences. The questionnaire inquired about COVID-19 risk perception and prevention behaviors, including questions about employment, ability to telework, and household characteristics. We calculated weighted frequencies with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for each CASPER to report the projected number and household percent with a particular response in the sampling frame.6 Weighted analyses were calculated for response categories ≥5 households.6 All stated differences between both populations were statistically significant unless otherwise stated in the text. Analyses were conducted with EpiInfo, version 7.2.3.1.8 This activity was reviewed by CDC, received a non-research determination, and was conducted consistent with applicable federal law and CDC policy.7

Results

Interview teams conducted a combined 395 surveys: 206 of 210 (98% completion rate; 56% contact rate) in H/L-CBHs and 189 of 210 (90% completion rate; 47% contact rate) in non-H/L-CBHs. In H/L-CBHs, 72% of households identified as H/L; in non-H/L-CBHs, 79% of households identified as non-H/L (Table 1). H/L-CBHs predominately spoke Spanish at home—66%, compared to 7% of non-H/L-CBHs. The respondents from each CASPER differed in household income with 60% of H/L-CBHs reporting <$50,000 per year compared to 30% of households from non-H/L-CBHs. Residing in a rental unit was more common for H/L-CBHs; 61% reported renting their residence versus 27% of non-H/L-CBHs. Household size was slightly larger in H/L-CBHs (mean = 3.6 persons) compared to 2.7 persons in non-H/L-CBHs. Homes in H/L-CBHs had slightly fewer bedrooms than those in non-H/L-CBHs (2.6 versus 2.9); this difference was not statistically significant. H/L-CBHs reported having slightly fewer bathrooms in the home (1.5 versus 2.1) than non-H/L-CBHs. H/L-CBHs reported greater employment in essential industries, with 79% working in essential services, including agriculture, food service, health care, education, and others, compared to 57% of non-H/L-CBHs. Specifically, 51% of H/L-CBHs worked in the agricultural sector versus 7% of non-H/L-CBHs. Seventy percent of H/L-CBHs reported inability for any household members to perform job duties from home compared to 46% of non-H/L-CBHs. Seven percent of H/L-CBHs reported no employed persons (unemployed or retired) in the home versus 25% of non-H/L-CBHs.

Table 1. Weighted household COVID-19 demographics from the Community Assessments for Public Health Emergency Response (CASPERs)—Wenatchee and East Wenatchee, Washington State, 2020

Abbreviations: CI = confidence interval; HH = household; (-) = responses with cells <5, number of responses was too few to be weighed. H/L census blocks (CBs), defined as ≥50% of households having ≥1 H/L house member (“H/L-CBHs”) and another from non-H/L CBs (<50% of households having ≥1 H/L house member [“non-H/L-CBHs”]).

When asked open-ended questions about familiarity with COVID-19 prevention messaging, there was no statistically significant difference in having heard that protective face coverings should be worn (89% of H/L-CBHs versus 94% of non-H/L-CBHs) or that physical distancing could prevent COVID-19 (68% of H/L-CBHs versus 73% of non-H/L-CBHs). Seventy percent of H/L-CBHs versus 61% of non-H/L-CBHs stated that they had heard that handwashing is a COVID-19 prevention strategy.

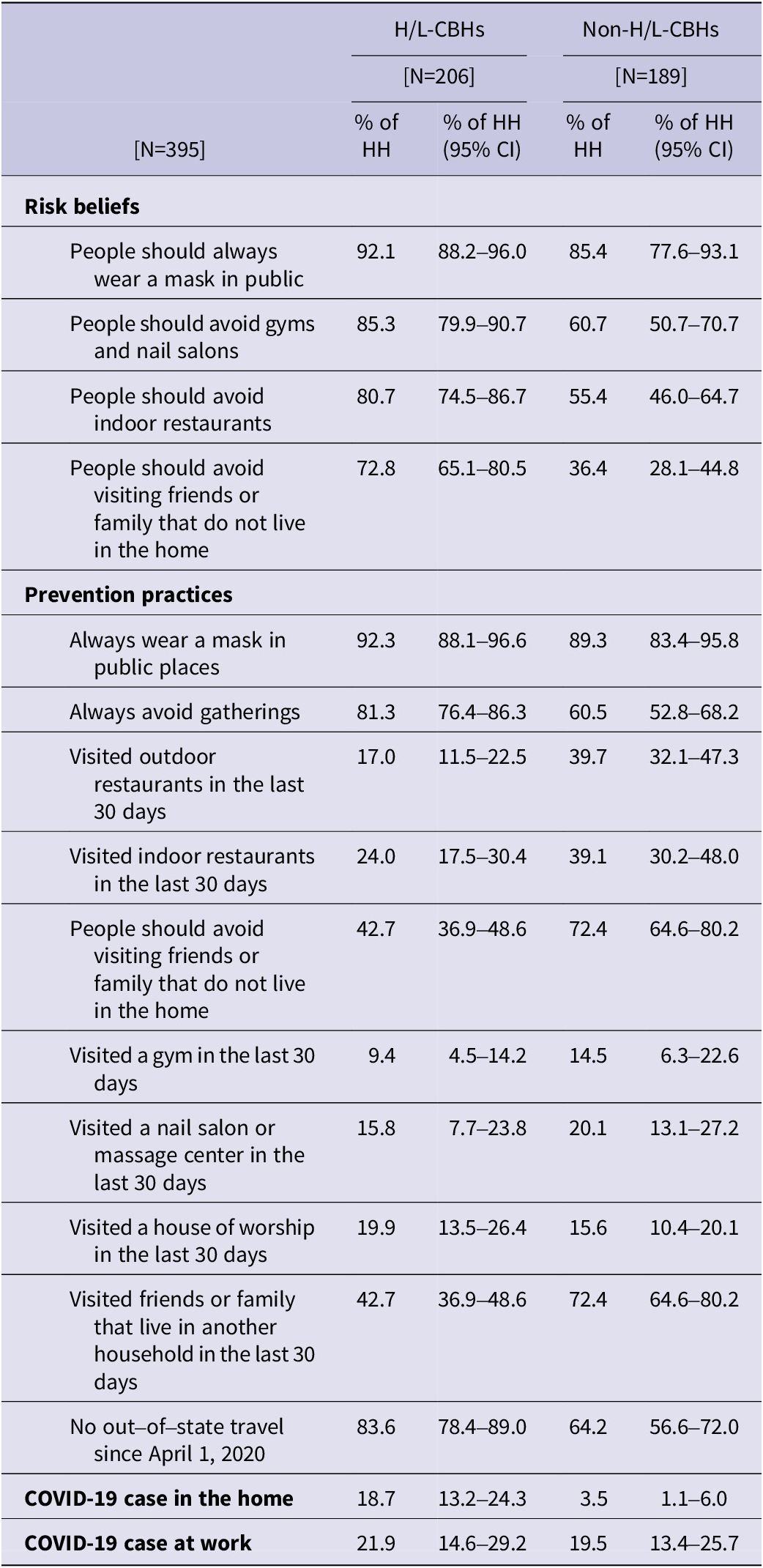

When asked about COVID-19 prevention behaviors, 92% of H/L-CBHs stated that persons should always wear a mask when in public versus 85% of non-H/L-CBHs (Table 2). Among H/L-CBHs, 81% indicated that indoor restaurants should be avoided, compared to 55% of non-H/L-CBHs. Seventy-three percent of H/L-CBHs stated that visiting friends or family that live in another home should be avoided versus 36% of non-H/L-CBHs.

Table 2. Weighted household COVID-19 risk beliefs, prevention practices from the Community Assessments for Public Health Emergency Response (CASPERs)—Wenatchee and East Wenatchee, Washington State, 2020

Abbreviations: CI = confidence interval; HH = household. H/L census blocks (CBs), defined as ≥50% of households having ≥1 H/L house member (“H/L-CBHs”) and another from non-H/L CBs (<50% of households having ≥1 H/L house member [“non-H/L-CBHs”]).

Households from both CASPERs reported similar frequencies of mask usage when in public (92% of H/L-CBHs versus 89% of non-H/L-CBHs; not statistically significant) (Table 2). More H/L-CBHs avoided social gatherings than non-H/L-CBHs (81% versus 61%). In the last 30 days, fewer H/L-CBHs reported visiting friends or family in another household (43% versus 72%) and lower restaurant dining (outdoor 17% versus 40%; indoor 24% versus 39%) compared to non-H/L-CBHs, although differences in indoor dining were not statistically significant. More H/L-CBHs compared to non-H/L-CBHs reported no out-of-state travel since April 1, 2020—84% versus 64%.

Sixty-three percent of H/L-CBHs knew someone who had previously tested positive for COVID-19 compared to 68% of non-H/L-CBHs (not statistically significantly different). More H/L-CBHs reported having ever had a person with COVID-19 at home (19% versus 4%) compared to non-H/L-CBHs. Both populations knew someone at work who tested positive for COVID-19 at similar frequencies (22% H/L-CBHs versus 19% non-H/L-CBHs; not statistically significant).

A greater frequency of H/L-CBHs (38%) did not feel safe sending their children back to school compared to 12% of non-H/L-CBHs. Fewer H/L-CBHs had adequate technology (including computers and internet) at home to carry out work or school duties (82% versus 94% of non-H/L-CBHs).

Fewer than half of both populations said they would get the COVID-19 vaccine if it were available, and the differences were not statistically significant (42% of H/L-CBHs and 46% of non-H/L-CBHs) (Table 3). The remaining households indicated that they might (25% H/L- CBHs versus 30% non-H/L-CBHs), would not (25% H/L-CBHs versus 19% non-H/L-CBHs), or did not know (8% H/L-CBHs versus 5% non-H/L-CBHs) if they would get the vaccine. Among those groups combined, lack of trust of the COVID-19 vaccine was the main reason for not getting the vaccine, with 24% of H/L-CBHs and 29% of non-H/L-CBHs stating they felt this way. The primary source of mistrust was due to concern over side effects and was cited by 17% of H/L-CBHs and 18% non-H/L-CBHs.

When asked about household needs, 61% of H/L-CBHs reported having enough money in the last 30 days to meet their basic needs compared to 81% of non-H/L-CBHs (Table 3). A larger percentage of H/L-CBHs versus non-H/L-CBHs reported difficulty paying for housing (16% versus 4%) and skipping/cutting the size of meals (19% versus 6%). Among H/L-CBHs, 68% had health insurance compared to 93% of non-H/L-CBHs.

Table 3. Weighted household COVID-19 vaccine acceptability and health insurance coverage from the Community Assessments for Public Health Emergency Response (CASPERs) — Wenatchee and East Wenatchee, Washington State, 2020

Abbreviations: CI = confidence interval; HH = household. H/L census blocks (CBs), defined as ≥50% of households having ≥1 H/L house member (“H/L-CBHs”) and another from non-H/L CBs (<50% of households having ≥1 H/L house member [“non-H/L-CBHs”]).

(-) = responses with cells <5, number of responses was too few to be weighed.

Limitations

Analyses and findings of these CASPERs were subject to several limitations. With in-person surveying, social desirability responses are always a potential limitation to findings.Reference Fisher9 It is also possible that some questions were not well understood by all households. Additionally, households that declined to participate may differ from those that did; for example, households who believe in the severity of COVID-19 may be more likely to participate than those that do not.

These assessments aimed to examine differences between H/L and non-H/L populations by selecting census blocks that had ≥50% of households with ≥1 H/L member for the H/L-CBHs CASPER and census blocks with <50% of households with ≥1 H/L member for the non-H/L-CBHs CASPER. While CASPER sampling yielded 2 populations that were statistically significantly different in ethnicity and reflected predominately H/L and non-H/L households, crossover existed, meaning that some households in the H/L-CBHs CASPER identified as non-H/L and some households in the non-H/L-CBHs CASPER identified as H/L. This is unsurprising since census data are from 2010, and new housing development and population shifts were anticipated. Migrant workers were likely largely excluded from the CASPERs, unless they resided in town, as most live in employer-sponsored dormitories outside of Wenatchee and East Wenatchee. Although most migrant workers do not live in town, they have contact with town residents at the workplace and in town when they visit to shop for food, send remittances back home, and carry out other errands.

These analyses were limited to frequency comparisons between households from predominately H/L and non-H/L census blocks without further stratification. Discussions were limited to differences between H/L and non-H/L populations in their beliefs regarding COVID-19 prevention behaviors, their adoption, and household needs because of the pandemic. However, households were sampled exclusively from census blocks in Wenatchee and East Wenatchee, Washington, and findings and estimates were only generalizable to this community.

Discussion

Demographics

We aimed to identify differences between H/L and non-H/L communities in working conditions, COVID-19 risk beliefs, prevention practices, and engaging in behaviors that increase the risk of COVID-19 exposure to understand factors that might explain COVID-19 disparities between the populations in Wenatchee and East Wenatchee, Washington. Demographic characteristics, including ethnicity and primary language spoken at home, between H/L-CBHs and non-H/L-CBHs households were distinct, indicating that sampling methodology was successful and population estimates reported were representative of each community. H/L-CBHs predominately identified as H/L persons and spoke Spanish at home, whereas non-H/L-CBHs overwhelmingly identified as non-Hispanic white persons and predominately spoke English at home. There were also significant economic differences: H/L-CBHs had smaller household incomes and rented at higher frequencies and fewer had health insurance compared to non-H/L-CBHs. Lack of health insurance may have been a barrier to COVID-19 testing because uninsured persons have lower odds of perceived access to testing compared to insured persons,Reference Ali, Tozan and Jones10 which may lead to delays in testing among the uninsured and facilitate further transmission in households, the workplace, and community. H/L-CBHs also had slightly more household residents and fewer bathrooms in the home, suggesting greater household density compared to non-H/L-CBHs. There was an overall gap in household incomes between H/L-CBHs and non-H/L-CBHs, with 60% of H/L-CBHs versus 30% of non-H/L-CBHs reporting household incomes under $50,000 year annually; notably, 0% of non-H/L-CBHs versus 21% of H/L-CBHs reported household incomes >$100,000 per year. As evidenced by concurrent qualitative fieldwork, some of the disproportionate burden of COVID-19 observed in the H/L communities was likely due to a myriad of factors driven by economic conditions because of longstanding social inequities (Group discussion team meeting, October 2020).

H/L-CBHs reported greater representation in essential industries with an inability to telework compared to non-H/L-CBHs. The nature of essential work often places employees near persons who reside in other households and increases employees’ risk of COVID-19. Reporting to in-person work has been associated with a greater odds of testing positive for COVID-19.Reference Fisher, Olson and Tenforde11 The finding that H/L-CBHs engaged in fewer social gathering behaviors compared to non-H/L-CBHs, coupled with the finding that the majority of H/L-CBHs were comprised of essential workers who could not telework, indicates that some of the disproportionate burden of COVID-19 in the H/L community was likely from exposure at the workplace and related activities such as shared commuting. A study of agricultural workers in the Salinas Valley of California, a group disproportionately burdened by COVID-19 and predominately comprised of H/L persons, reported very little social gathering with persons outside their home and found that having a person diagnosed with COVID-19 in the workplace increased the risk of agricultural workers testing positive.12 Our findings demonstrate that H/L-CBHs and non-H/L-CBHs both knew persons at work who had tested positive for COVID-19 at similar frequencies, yet a considerably higher frequency of H/L-CBHs reported a person diagnosed with COVID-19 at home compared to non-H/L-CBHs. Non-H/L-CBHs reported greater ability for employed household members to telework compared to H/L-CBHs; it is possible that due to higher rates of telework, persons from non-H/L-CBHs were never exposed to COVID-19-positive coworkers if they could remain at home. It is also possible that H/L-CBHs had a greater risk of a member contracting COVID-19 because, collectively, there was more exposure due to more of these households’ working adults having to work outside the home. It is also possible that industries with essential in-person workers differed significantly in their adherence and implementation of infection control. H/L-CBHs predominately reported employment in agriculture for essential workers compared to non-H/L-CBHs where most essential workers worked in health care. One study found that symptomatic farmworkers continued to work because they felt well enough.12 They also reported working conditions that did not allow for social distancing at the workplace during work hours or in breakrooms and that many employers were not conducting health screening checks of employees.12 Similar problems could have occurred in the agricultural workplaces in Washington, despite attempts to implement COVID-19 infection prevention and control regulations. A governor’s office regulation went into effect in August 2020 requiring any agricultural facility to shutdown to perform cleaning and test all employees if 9 or more employees test positive in a 2-week period.13 Although intended to promote worker safety, this regulation may have unintentionally driven down testing rates, despite paid leave policies, since employees might have feared losing work if they tested positive and employers might have feared a loss of harvest if too many people tested positive.

Both populations reported knowing someone who tested positive for COVID-19 at similar frequencies, but H/L-CBHs reported having a case in the home over 5 times more than non-H/L-CBHs, where most known cases largely occurred outside the home. This suggests that, in addition to workplace exposures, household transmission may be contributing to the H/L community’s disproportionate COVID-19 burden, a finding similar to other studies with H/L households.Reference Madewell, Yang and Longini14, Reference Podewils, Burket and Mettenbrink15 Intergenerational housing,Reference Stokes and Patterson16 which is more common among H/L households compared to non-Hispanic white households, and increased household density may compound the risk of COVID-19 among the H/L population. H/L-CBHs reported slightly more household members and slightly smaller dwelling sizes than non-H/L-CBHs, consistent with previous COVID-19 studies’ findings that H/L households were larger than those of non-Hispanic households.Reference Selden and Berdahl4, Reference Madewell, Yang and Longini14

COVID-19 isolation guidance recommends that persons with COVID-19 isolate in the home and use a separate bedroom and bathroom from others in the household if feasible.17 Although both groups reported a similar number of bedrooms in the homes, H/L-CBHs reported slightly fewer bathrooms and slightly more people in the dwelling. Denser households that have fewer bathrooms may not allow for proper adherence to isolation and quarantine measures when a household member tests positive for, or is exposed to, COVID-19. Farmworkers in California’s Salinas Valley have cited an inability to isolate within the home,12 and household crowding has been recognized as risk factor for COVID-19, contributing to household transmission.Reference Emeruwa, Ona and Shaman18

COVID-19 Risk Perceptions and Behaviors

Consistent with high COVID-19 prevention knowledge observed among H/L farmworker households in North Carolina,Reference Quandt, LaMonto and Mora19 we observed high levels of awareness of COVID-19 messaging among H/L households (68%-89% of H/L-CBHs) for basic prevention and prevention strategies: wearing face coverings, washing hands, and social distancing; non-H/L groups also reported high levels (61%-94% of non-H/L-CBHs). Despite high awareness of prevention knowledge among both groups, behavioral risk beliefs and reported practices of COVID-19 prevention behaviors differed significantly between H/L-CBHs and non-H/L-CBHs. H/L-CBHs had higher COVID-19 risk perception compared to non-H/L-CBHs, as evidenced by beliefs that visiting persons living in another household and indoor dining at restaurants should be avoided; both behaviors have been associated with COVID-19 test positivity.Reference Fisher, Olson and Tenforde11 Further, H/L-CBHs reported practicing these behaviors less than non-H/L-CBHs. H/L-CBHs’ holding more conservative COVID-19 risk beliefs and engaging less in risky practices than non-H/L-CBHs may indicate a greater concern for contracting COVID-19 among H/L-CBHs and attempts to mitigate risk outside of work.

Similar to other studies that found parents from racial/ethnic minorities have been more concerned about school reopening than non-H/L white parents,Reference Gilbert, Strine and Szucs20 CASPER results demonstrated that H/L-CBHs felt uncomfortable sending children back to schools at much higher frequencies than non-H/L-CBHs, despite also reporting less access to technological hardware and internet connectivity capacity than non-H/L-CBHs. It is possible that more H/L-CBHs may not feel safe sending their children back to school because more households from these census blocks have had COVID-19 cases in the home compared to non-H/L-CBHs.

Vaccine Acceptability

CASPER findings showed COVID-19 vaccine acceptability was similarly low (<50%) without any difference between groups. Among households that did not indicate they would definitely receive the vaccine, most cited mistrust of the vaccine with particular concern about side effects. Some households stated the swiftness of vaccine development as a concern, with too much unknown about the long-term effects. Similarly, in a study of H/L farmworkers in Salinas Valley, California, where only 52% indicated they would receive the COVID-19 vaccine,12 vaccine-related side effects were reported as the main concern for definitely not wanting to receive a COVID-19 vaccine. Of note, this assessment was conducted when COVID-19 vaccines or trial data were not yet available in the United States. Studies of COVID-19 vaccine acceptability in the United States have indicated that some H/L persons, as well as those who live in rural communities, have expressed vaccine hesitancy, which aligns with what we observed.Reference Khubchandani, Sharma and Price21

Household Needs

A disproportionately higher number of H/L-CBHs reported lacking sufficient income to meet their basic needs because of the pandemic. These households reported having trouble paying for housing and utilities and had to cut/skip meals because of economic hardship from COVID-19. Despite findings of a nationally representative US study that found that racial/ethnic minorities did not have more food insecurity than white households during the pandemic,Reference Morales, Morales and Beltran22 we observed stark differences in cutting meal size and skipping meals because of the effects of the pandemic between H/L-CBHs and non-H/L-CBHs. H/L-CBHs also reported having health insurance less than non-H/L-CBHs. Access to support services, including food banks, shelters, and free clinics, is often less common in rural versus urban communities, and it is possible that H/L households in rural areas have been disproportionately affected due to preexisting shortages in services.Reference Douthit, Kiv and Dwolatzky23

Conclusions

H/L populations are overrepresented in essential jobs and occupations, which require in-person work performed in close proximity to others and which often pay low wages and do not offer paid sick leave.24, Reference Dubay, Arons and Brown25 Persons in these occupations have experienced high morbidity and mortality due to COVID-19.Reference Chen, Glymour and Riley26, Reference Hawkins, Davis and Kriebel27 Further, disproportionate COVID-19 mortality has been associated with lower incomes.Reference Seligman, Ferranna and Bloom28 Therefore, there is a need for comprehensive analyses by socioeconomic status as the two populations differed significantly with regard to income and risk.

Despite the limitations, there were some key lessons from these assessments. CASPER survey methodology has traditionally been employed as a rapid needs assessment tool in disaster and emergency response6 but can be adapted in community COVID-19 outbreak response to quickly assess COVID-19 behavioral risk beliefs, adoption of prevention practices, vaccine acceptability, and pandemic household needs. Conducting two CASPERs with an identical questionnaire allowed for quick measurement of responses in 2 representative samples to understand similarities and differences regarding employment conditions, COVID-19 prevention beliefs and practices, vaccine acceptability, and households needs. We found that H/L-CBHs had greater COVID-19 risk perception and practiced more COVID-19 prevention behaviors than non-H/L-CBHs; nonetheless, H/L-CBHs had a higher burden of COVID-19 than non-H/L-CBHs. H/L-CBHs were slightly larger, more were employed in essential industries, and they had a greater inability to telework. This suggests that H/L households may have higher collective risk of introducing COVID-19 into the home due to larger household sizes with possibly more members who must present to in-person work. Findings support important points for those trying to reduce the risk of COVID-19 transmission: 1) it is necessary to improve COVID-19 risk perception and promote effective risk reduction messaging to improve increased adherence to prevention strategies for all community members; 2) it is necessary to address concerns over vaccine side effects in the entire community in order to improve COVID-19 vaccine acceptability; 3) high-density essential worker industries, including agriculture, should ensure proper implementation of prevention strategies at the workplaceReference Waltenburg, Rose and Victoroff3, 29; and 4) data indicate a need for social support programs (housing, health, and food security programs) as a result of the pandemic, particularly for H/L households.

Disclaimer

The findings and conclusions of this report are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Acknowledgments

All survey respondents, surveyor teams, incident management teams, and the community of Chelan and Douglas Counties, Washington.

Author contribution

Nancy Ortiz, Adela Hoffman, Amy Helene Schnall, and Peter Houck conceived and designed the study. Nancy Ortiz, Adela Hoffman, Amy Helene Schnall, and Edgar Monterroso adapted the survey instrument. Nancy Ortiz, Adela Hoffman, Emily A. Lilo, Hannah Lofgren, and Edgar Monterroso piloted the survey instrument. Nancy Ortiz, Adela Hoffman, James S. Miller, Emily A. Lilo, Hannah Lofgren, and Edgar Monterroso collected data. Nancy Ortiz, Adela Hoffman, Alexey Clara, and James S. Miller analyzed the data. Lisa Guerrero supported the logistics of project. Nancy Ortiz, Adela Hoffman, Amy Helene Schnall, Emily A. Lilo, James S.Miller, and Edgar Monterroso prepared the manuscript. Peter Houck, Nathan Weed, and Edgar Monterroso approved the manuscript.

Funding Statement

No sources of financial support to acknowledge

Competing interests

None