Introduction

The massive urban project Skopje 2014 has received a lot of scholarly and media attention since its introduction to the public in 2010 by the conservative government, led by the VMRO-DPMNE party.Footnote 1 Initially slated to cost 80 million euro, the final costs of the project reached a stunning 680 million euro. The project is, above all, seen as a nationalist undertaking, and rightly so. Over 150 sculptures and monuments and over 20 new neoclassical and baroque buildings celebrate North Macedonia’s nationhood.Footnote 2 The dominance of ancient figures and an eclectic neo-historical style tend to point to an uninterrupted link between ancient and modern times, glorifying the time of Alexander the Great and the ancient Kingdom family (Vangeli Reference Vangeli2011). Other monuments of various historical figures promote the idea of a Macedonian nation in a city divided along ethnonational lines (Véron Reference Véron2015).

Academic analyses of Skopje 2014 have highlighted the attempt to link the emergence of the project with geopolitical tensions over the name issue with Greece (Kolozova et al. Reference Kolozova, Lecevska, Borovska and Blazeva2013; Dimova Reference Dimova2013). Other works approached the project from different academic angles, such as social movements (Mattioli Reference Mattioli and Petrović2014; Véron Reference Véron2016; Staletović and Pollozhani Reference Staletović and Pollozhani2022), neoliberalism and nation-branding (Graan Reference Graan2013, Reference Graan2016; Véron Reference Véron2021), political mobilization and the role of the socialist heritage (Stefoska and Stojanov Reference Stefoska and Stojanov2017; Janev Reference Janev2017; Koteska Reference Koteska2011), as well as from the urban planning perspective and ethnic nationalism (Grcheva Reference Grcheva2018; Mojanchevska Reference Mojanchevska2020; Čamprag Reference Čamprag2019). The nondemocratic background and its relations to the financial aspect of Skopje 2014 were examined by Mattioli (Reference Mattioli2018; Reference Mattioli2020), while other scholars focused on the arbitrary urban planning processes (Blazhevski Reference Blazhevski2021; Čamprag Reference Čamprag2019). Blazhevski (Reference Blazhevski2021) engages directly with the competitive authoritarian concept by analyzing the decision-making process regarding urban planning of Skopje 2014.

Although the scholars have produced remarkable knowledge, no analysis has systematically explored the link between (competitive) authoritarianism and Skopje 2014. Skopje 2014 was carried out during a rising authoritarian rule in the country, more precisely during its peak between 2010 and 2016. During that time, the government led by VMRO-DPMNE and Prime Minister Nikola Gruevski, who is now in exile in Budapest, managed to gain control over key power domains in the country, as well as to establish control over mainstream media, including the state broadcasting service. Apart from that, the state invested a lot of resources in various cultural projects to advance the idea of North Macedonia’s nationhood, which received criticism due to the exclusion of the large Muslim and Albanian population from the major cultural campaigns set up by the state (Vangeli Reference Vangeli2011). Critics also came from the part of the “Macedonian” political parties, civil activists and cultural institutions that did not share the conservative party’s vision for the capital (Graan Reference Graan2013).

Besides being the most prominent project, Skopje 2014 was also the government’s Achilles’ heel, as it was consistently under attack by the opponents, the main opposition party, and part of the civil society organizations due to the enormous costs and systematic corruption, contentious style, and exclusionary content. To counteract these sociopolitical challenges and formal legal mechanisms regulating urban planning, the conservative government relied on a set of political strategies, as well as on mobilization of state and non-state groups associated with VMRO-DPMNE and the political right in general, to implement and legitimize Skopje 2014 in a competitive political landscape.

This article seeks to answer what set of authoritarian political practices were critical in redesigning the capital. Additionally, this article acknowledges the specificity of the so-called “competitive authoritarianism” and looks at how this form of a “hybrid regime” facilitated the makeover of Skopje. Competitive authoritarianism is a type of political setting in which “formal democratic institutions exist” but are bypassed by informal networks, political coercion, control of media, and abuse of state institutions (Levitsky and Way Reference Levitsky and Way2010, 5; Bieber Reference Bieber2018). Social resistance, competitive opposition, and formal legal mechanisms may often confront the central government’s agenda.

The central argument of this article is that the promoters created a large organization consisting of state and “outside” groups supported by nondemocratic practices to make the project possible. Examining how the urban project was strategized and implemented through these political practices is the key focus of this study. It also showcases that the VMRO-DPMNE party used the urban space and architecture to promote its central ideological principles. I introduce the term party-building to better capture this process, as will be discussed in the last section. Moreover, this article acknowledges the distinctiveness of Skopje 2014 as a type of an “urban megaproject” (Čamprag Reference Čamprag2019) whose implementation required the mobilization of various state institutions and non-governmental groups and many rearrangements of the urban planning procedures.

Methodologically, the study draws on primary sources, namely interviews,Footnote 3 secondary data sources such as the official database of objects in the project (BIRN, Skopje 2014 Uncovered), interviews from the documentary Skopje Prodolzuva, media reports related to different aspects of Skopje 2014, and leaked recordings published in various media houses that revealed the depth of the political entanglement in the project.

Situating the Research: Urban Megaprojects and Authoritarian Practices in Capital Cities

The large-scale-urban interventions, conceptualized as “urban megaprojects,” have been particularly significant for the state and nation-building process, gaining prominence in the postwar period (Orueta and Fainstein Reference Orueta and Fainstein2008). One of the characteristics of these projects was that they bring “together…several scales of power… local, regional, national, and global domains of social action” (del Cerro Santamaria Reference Del Cerro Santamaria2019, 264). They are also characterized by many “rearrangements, corrections and additions” (del Cerro Santamaria Reference Del Cerro Santamaria2019, 272), which are often carried out in a non-transparent manner, not excluding liberal political systems (Novy and Peters Reference Novy and Peters2012).

When it comes to large urban projects in full-scale authoritarian and totalitarian regimes, the urban design of capitals was often not restricted by any legal regulations; planning was strictly centralized, and leaders took the role of planners, as was the case with Stalin, Hitler, and Ceausescu (Cavalcanti Reference Cavalcanti1997). The monumentality of Skopje 2014 resembles the post-socialist developments in central Asian cities (Graan and Takovski Reference Graan and Takovski2017). The (re)making of these capitals relied on centralized state structures, a cult of personality, and ideological content reaching back to the distant past (Šír Reference Šír2008).

In the post-Yugoslav states, large-scale urban projects were somewhat absent in the context of the Yugoslavian dissolution and war, as well as turbulent and strenuous political and economic transformation. Only in the last decade have states invested in massive undertakings, such as Skopje 2014 and Belgrade Waterfront, as an attempt to redevelop and rebrand the capitals (Čamprag Reference Čamprag2019). Likewise, under Erdogan, Istanbul has undergone significant urban changes, characterized by arbitrary processes regarding the redevelopment of public space, discussed by scholars through concepts such as “authoritarian neoliberalism” (Bruff and Tansel Reference Bruff and Tansel2018) or “neoliberal Islamism” (Batuman Reference Batuman2015).

Indeed, some components characterizing totalitarian urban planning operate in hybrid regimes. However, unlike totalitarian planning, the North Macedonian case reveals that the remaking of Skopje relied not so much on repressive mechanisms but instead on weakening institutions and opportunistic practices, as well as on a gradual process of power centralization in the country. Besides this, the developers created a complex network, which was able to deal with legal and political challenges that may have hindered plans for rebuilding the capital.

The literature on hybrid regimes and competitive authoritarianism in the Balkans and beyond has paid much attention to the role of institutions, media, as well as external processes in perpetuating these regimes (Bieber Reference Bieber2018; Kapidžić Reference Kapidžić2020; Kmezić Reference Kmezić2020), whereas the aspect of spatiality in the context of the urban megaprojects has not been systemically researched. We thus know little about how the competitive authoritarian regime coordinates and exercises its power through the urban planning and how the developers use “outside groups” (Gandhi Reference Jennifer2008) to advance their spatial agenda. Similarly, although not related directly to the notion of urban space, Goodfellow and Jackman (Reference Goodfellow and Jackman2020) observe that nondemocratic processes in hybrid regimes received a lot of attention on the national scale. In contrast, capital cities and their role in reproducing authoritarian practices have been researched far less. The authors offer a typology of strategies to approach nondemocratic practices in capital cities that they see as “the crucial sites in the reproduction of authoritarian dominance” (Goodfellow and Jackman Reference Goodfellow and Jackman2020, 3). Drawing on their work, as well as on literature on competitive authoritarianism (Levitsky and Way Reference Levitsky and Way2010; Bieber Reference Bieber2018; Reference Bieber2020), this article analyzes a set of political strategies that proved pivotal in implementing the project Skopje 2014, which in turn helped the VMRO-DPMNE government to expand its political dominance.

Contextualizing the Research: Urban Space and Politics in Skopje and North Macedonia

The urban development of modern Skopje has been shaped by a devastating earthquake that hit the city in 1963, which destroyed and damaged over 70% of the city. The master plan for the central area that followed was developed by the renowned architect Kenzo Tange and was based on a modern approach to architecture and urban planning (Home Reference Home2007). Although the plan was not fully implemented, modernist and brutalist architecture heavily influenced the subsequent architectural development of Skopje (Mijalkovic and Urbanek Reference Mijalkovic and Urbanek2011; Dimova Reference Dimova2019). After the country gained independence in 1991, Skopje and the rest of the state were affected by structural and political changes. Concerning urban space, while new planning laws drew on previous regulations, they were upgraded with regulatory mechanisms, “introducing obligatory standards for urban planning and design” with the intent to establish rules and regulations without ideological direction (Grcheva Reference Grcheva2018, 4). The urban character of Skopje came to be intensively shaped by state-driven ideological interventions in the early 2000s, with the rise of objects representing religious and ethnonational attachments (Vangeli Reference Vangeli2010; Ragaru Reference Ragaru2008).

As for ethnicity, the southern part of the city’s population consists of over 95% ethnic Macedonians, whereas the northern side is populated by “members” of different ethnicities, dominated by ethnic Albanians. The 2002 Skopje census data show that 66% identified as ethnic Macedonians, followed by 20% as Albanians, and 5% as Roma and other nationalities. The newest 2021 census shows the number of Albanians rose to 22.8 % in Skopje. The city’s historical center, the Ottoman Bazaar, is located in the northern part of the city. Over the 1990s, the Bazaar served as a space of informal trade (Shott Reference Shott2001), seen by a part of the citizens, especially in the early 2000s, as an “Albanian bastion” (Dimova Reference Dimova2019, 962). In 1992, violence committed by the North Macedonian police left four people dead in the Bazaar. As Janev (Reference Janev2011, 16) puts it, it took more than ten years for this historical space to “come back to life,” alluding to the lack of trust between ethnic Macedonians and Albanians, also generated by the systematic marginalization of Albanians, which has its roots before the independence (Brunnbauer Reference Brunnbauer2004).

As stated above, the intervention in the built environment driven by ideological motives gained momentum in the early 2000s, especially after the emergence of a new political elite in the country led by the new leader of VMRO-DPMNE,Footnote 4 Nikola Gruevski, who came to power in 2006. Additionally, the ethnic tensions between ethnic Macedonians and Albanians were exacerbated during the 1990s and led to violent conflict in 2001, after which the Ohrid Framework Agreement (OFA) was signed, which provided minorities, focusing primarily on Albanians, with a set of cultural and representative rights. This left a part of the population and political establishment fearing “losing the country” (Dimova Reference Dimova2013, 131) as they perceived the agreement as a triumph of Albanian nationalism.

The frustration from the new agreement spilled over into Skopje’s urban space. In 2002, a 66-meter-tall Millennium Cross, officially celebrating 2000 years of Christianity, was put up on the top of Skopje’s mountain Vodno, visible from every point in the city (Vangeli Reference Vangeli2010). At the time of the construction of the cross, Gruevski was the minister of finance and initiator of the idea of building the cross (Skopje Prodolzuva 2013). The object is perceived as a provocation to the Albanian community and an attempt to assert the dominance of ethnic Macedonians in the capital. The official narrative of “2000 years of Christianity” creates a tradition of historical ownership of the city, stretching back to the Ottomans’ capture of Skopje in the late 14th century and the introduction of Islam as a dominant religion. Against this backdrop, a statue of Skanderbeg, regarded as a central historical figure of Albanian nationalism, was installed in the heart of the city in 2006 (Ragaru Reference Ragaru2008).

Once the VMRO-DPMNE came to power in 2006, a so-called “antiquization campaign” was launched (Vangeli Reference Vangeli2011), attempting to redefine the national narrative structure in the country by elevating the ancient myth of origin as the dominant ethnic narrative of origin. This shift found its place in the historiography, textbooks, national holidays, and the urban environment. Skopje’s airport was renamed after Alexander the Great in 2006, the main football stadium after Philip II arena, and many streets were renamed after ancient figures. In 2010, the mayor of the city, joined by the mayor of the municipality of Centar and the minister of culture, announced the urban project Skopje 2014. Once promoted, the project demonstrated the continuation of the antiquization campaign in the urban environment, where the monuments to Alexander the Great and his family overshadow the central area of the city.

External Context, the Centralization of Power and Authoritarian Shift

As Skopje 2014 was under construction, the EU enlargement process in the Western Balkans (WB) slowed to a crawl. However, the so-called “enlargement fatigue” did not prevent the Balkan leaders from seeking external legitimacy in the EU. As Bieber notes, a lack of support for democratic processes by the EU and its key member states “has facilitated the emergence of regimes that base their external legitimacy on providing stability, rather than democracy” (Bieber Reference Bieber2018, 338). This particular dynamic allowed the leaders in WB to exploit the external circumstances to strengthen their political dominance. Alongside the EU’s reduced interest in the enlargement process in the region, Greece’s veto of North Macedonia’s bid to join NATO in 2008 was seen as an event that the conservative government used to victimize the country’s position and radicalize its nationalist politics (Beyer Reference Beyer2021; Kolozova et al. Reference Kolozova, Lecevska, Borovska and Blazeva2013), culminating in Skopje’s built environment.

While the external processes created a favorable environment for the top-down remake of Skopje, the domestic political dynamic enabled the party to control the processes that made the project possible. At the time of Skopje 2014’s announcement in 2010, VMRO-DPMNE controlled all key institutions in the country.Footnote 5 Between 2006 and 2010, the party won by a landslide in the 2008 national elections and clinched an overwhelming victory in the 2009 local elections in Skopje. Both events proved to have been turning points, enabling the conservative party control over central power structures, including the presidential office secured in 2009. A few months after VMRO-DPMNE won the local elections in Skopje, Skopje 2014 was unexpectedly announced in a short video presentation.

The nexus between local and national power enabled VMRO-DPMNE to fully utilize what Malešević (2013) terms as “coercive organizational capacity” of the modern state, which the government exploited to implement Skopje’s makeover. Moreover, the dominance of the conservative party created favorable conditions for embarking on what the former deputy prime minister in Gruevski’s government Ivica Bocevski (Kostova Reference Kostova2013) called a “VMRO-revolution” – an attempt to establish political hegemony in the political and cultural domains in the country.

During the construction of Skopje 2014, the VMRO-DPMNE controlled the major media outlets, newspapers, and mainstream TV stations – especially since 2011, when the state shut down the major private broadcaster A1. Additionally, the central state institutions were under the control of a small group of individuals from the leadership of the VMRO-DPMNE. Despite petitions to the constitutional court to evaluate the legal aspects of the government’s plan to redesign Skopje, the court dismissed these requests (Blazhevski Reference Blazhevski2021). Furthermore, Gruevski’s powerful cousin Sašo Mijalkov – a head of the Agency for Security and Counterintelligence – wiretapped over 20,000 citizens, including members of his government, journalists, and political opponents (Montague Reference Montague2015). Labels such as hybrid regime, Gruevism, illiberal politics (Gjuzelov and Hadijevska Reference Gjuzelov and Hadjievska2020), competitive authoritarianism (Bieber Reference Bieber2018), authoritarian populism (Petkovski Reference Petkovski2016), and ethnocratic regime (Janev Reference Janev2017) were used to capture the nature of the political dominance and the rise of authoritarianism and ethnic nationalism in the country. Gruevski, who established himself as a strongman (Bieber Reference Bieber2020), played a pivotal role in micromanaging the reconstruction of Skopje’s city center.

Seemingly, this was not a coincidence, as the lack of strong institutions had been a feature of the state before the rise of Gruevski (Willemsen Reference Willemsen2006), also applying to the spatial planning tradition. Namely, besides creating rival varieties of ethnic nationalisms, the implementation of the Millennium Cross (2002) and Skanderbeg statue (2006) was highly centralized and designed exclusively in a top-down manner (Vangeli Reference Vangeli2010; Ragaru Reference Ragaru2008). This trend intensified later on in the entire central area of Skopje, exposing a systematic effort to impose political and ethnonational dominance in the city.

Competitive Authoritarianism, Spatial Politics, and Urban Megaprojects: Expedience, Mobilization, and Informal Networks

The study identifies a few interrelated ways in which the competitive authoritarianism affected spatial politics in Skopje. I conceptualize these as arbitrary expeditious planning, extensive mobilization, and informal networking.

Scholars would emphasize that “most cities change slowly” (Vale Reference Lawrence1992, 276), yet this was hardly the case with the revamp of Skopje, where the decision-making agenda was marked by unprecedentedly rapid pace, chaotic and arbitrary interventions, and numerous changes of the Detailed Urban Plan (DUP) (Blazhevski Reference Blazhevski2021). Similarly, in the analysis on “neoliberal authoritarianism” in redeveloping of Istanbul by the Justice and Development Party (AKP), Giovanni discerns that Istanbul’s development was “branded at a faster rhythm” (Reference Di Giovanni and Tansel2017, 113), emphasizing expedited authorizations of the planning agenda, backed up by nondemocratic decision-making process.

What is it that makes these regimes intervene in the urban space at such a faster pace? To a large extent, it is the competitive nature of the political environment and the possibility for regime change and resistance, per se institutionally, through local and national elections, but also other democratic and civic practices (e.g., social resistance, protests, and civic disobedience). In other words, the risk of a possible regime change, on both national and local scales, generated a sense of urgency to implement Skopje 2014, which occurred parallel with the shrinking of the playing field for the opposition (Levitsky and Way Reference Levitsky and Way2010). Since the elections are the opening for regime change in a competitive political setting, Gruevski’s government acknowledged this probability and embarked on a hasty decision-making process, sidestepping experts’ and citizens’ input (Mojanchevska Reference Mojanchevska2020), and mobilizing its network to implement the project. Since gaining independence in 1991, North Macedonia’s party landscape has been characterized by hostile competition between VMRO-DPMNE and the Social Democratic Union of Macedonia (SDSM). This has also been the case in the capital. Thus, against competitive opposition and elections, the government engaged in an instant-style decision-making process. As the next section reveals, many laws and procedures were pushed through that did not allow for an inclusive and broader debate or the possibility of opposing initiatives.

Further, the organizational and informal aspects of the project proved crucial in implementing the project. As Levitsky and Way emphasize (Reference Levitsky and Way2010, 12), in a competitive authoritarian system, “incumbents are forced to sweat,” indicating that these particular regimes have to work hard to secure political hegemony. Simply put, authoritarianism is not “the only game in town” in this political environment (Guachalla et al., Reference Guachalla, Hummel, Handlin and Smith2021, 65). Unlike full authoritarian regimes, hybrid regimes face social, political, and legal resistance. They are more prone to lose their dominance than strict authoritarian systems, particularly in the capitals, which function as “generative space of mobilizations” (Uitermark, Nicholls, and Loopmans Reference Uitermark, Nicholls and Loopmans2012, 2546) where the resistance can take on a more massive form (Goodfellow and Jackman Reference Goodfellow and Jackman2020). As a result, these governments appear more vulnerable than the full-scale authoritarian states.Footnote 6

Challenged by a competitive opposition and electoral pressure, and also by the gigantic size of the urban revamp, which did not garner major approval in the broader society (Blazhevski Reference Blazhevski2021), the VMRO-DPMNE government embarked on mobilizing its supporters and network to implement, legitimize, and brand the undertaking at home and abroad (Graan Reference Graan2013; 2016). As the following sections will explore more deeply, this situation required a strenuous effort and the establishment of an organizational and informal support network micromanaged by Nikola Gruevski.

In the next sections, drawing partially on Goodfellow and Jackman’s analytical model, I flesh out this argument by discussing the nondemocratic strategies through which these processes have manifested in the capital. I look at the legal procedures and how the government controlled the decision-making processes before and after the announcement of Skopje 2014, the role of the strongman Gruevski, the legitimization strategies and the involvement of non-governmental groups and the business sector, the coercive mechanisms, and the role of ideology.

Political Strategies to Control the Capital and Urban Design Politics

Controlling the Decision-Making Process: 2006–2010

Hybrid governments rely less on repressive and violent measures, as they are too costly for the regime in the long run (Gerschewski Reference Gerschewski2013). They rather employ different mechanisms – among them, relying on control of the legislative process to impose its agenda. These legal means, while on their own not essential for the regime’s longevity, play an important part in controlling and manipulating political processes (Goodfellow and Jackman Reference Goodfellow and Jackman2020, 24). Moreover, these can be particularly relevant in a “vertically-divided authority” (Resnick Reference Resnick2014), whereby opposition is in power in capital cities or has control over certain vital municipalities, as was the case in Skopje’s Centar municipality after 2013.

The emergence of Skopje 2014 and the authoritarian-populist shift are often linked to the Greek veto of North Macedonia’s bid to join NATO in 2008 (Beyer Reference Beyer2021; Kolozova et al. Reference Kolozova, Lecevska, Borovska and Blazeva2013). Indeed, the summit’s outcome allowed the government to draw popular legitimacy for its ideological projects. However, the data presented below reveals that the plans and decision-making process for redesigning the city center already unfolded in 2006, when VMRO-DPMNE took power (Blazhevski Reference Blazhevski2021). The decision to build a monument to Alexander the Great – the main symbol of Skopje 2014, built in 2011 – took place already in 2006, when the mayor of the municipality of Centar, Violeta Alarova, signed off on the decision (Jordanovska Reference Jordanovska2015b).Footnote 7 Furthermore, the announced reconstruction of the parliament building in 2006 reveals the government’s early interest in remodeling the city as well as the arbitrariness of the process (Blazhevski Reference Blazhevski2016). The government’s proposal, which was inspired by the German Bundestag in Berlin (Vojnovska Reference Vojnovska2009; Blazhevski Reference Blazhevski2016), was met with resistance by local architects who argued that the national parliament is protected by law as a cultural monument and, as such, any reconstruction is prohibited (Blazhevski Reference Blazhevski2016). Despite the protest and boycott of part of the architectural commission involved in the process (Interview with Kokan Grchev, Reference Grchev2021), the government pushed the initiative and selected other pro-government members for the architectural commission in 2007. Eventually, the reconstruction of the parliament commenced in 2010.

The determination to swiftly change the urban design of Skopje became apparent after several abrupt changes to the Detailed Urban Plan. As Grcheva (Reference Grcheva2018) states, the adoption of a new DUP is a process that usually takes at least one year and involves the contribution of various institutions and citizens. However, between 2007 and 2012, nine unprecedented changes to the DUP occurred (Blazhevski Reference Blazhevski2021). In the 2007 DUP, the monument to Alexander the Great, the building of the new national theatre, the reconstruction of parliament and the City Hall, and the Macedonian Philharmonic orchestra were enacted (Blazhevski Reference Blazhevski2021, 90) despite the objections by the Skopje’s mayor, Kostovski. The next DUP that was approved nine months later included the VMRO Museum and the state archive, a religious object, and new buildings and momuments on the left bank of river Vardar (Dnevnik 2008). Two years later, all these objects were promoted as a part of Skopje 2014. The discussed events speak of a planned operation ahead of the NATO summit in 2008. Moreover, the expedited adoption of new DUPs indicates the urgency posed by the competitive political environment.

The apparent interest of the state in redesigning Skopje was reinforced by a state project announced in 2009. As a part of it, over 30 bronzed sculptures were installed around the city. According to Chausidis, this project also helped lay the foundation for Skopje 2014, as it enabled the government to judge the public response related to the issues of urban space (Interview with Chausidis, Reference Chausidis2021). While its promoters received critics because of a “tasteless” design, the project faced no resistance. The very next year, Skopje 2014 was announced.

Controlling the Decision-Making Process: 2010–2015

The rapid and arbitrary decision-making process accelerated after the local elections in 2009 and the announcement of Skopje 2014 the following year. In 2009, the VMRO-DPMNE won by a landslide in Skopje, securing the municipality of Centar and the mayor’s office, two institutions that proved essential in administering Skopje 2014. The dominance on the local scale, alongside the national one, enabled the government to avoid lengthy procedures, preventing more inclusive participation of citizens, experts, and political opposition.

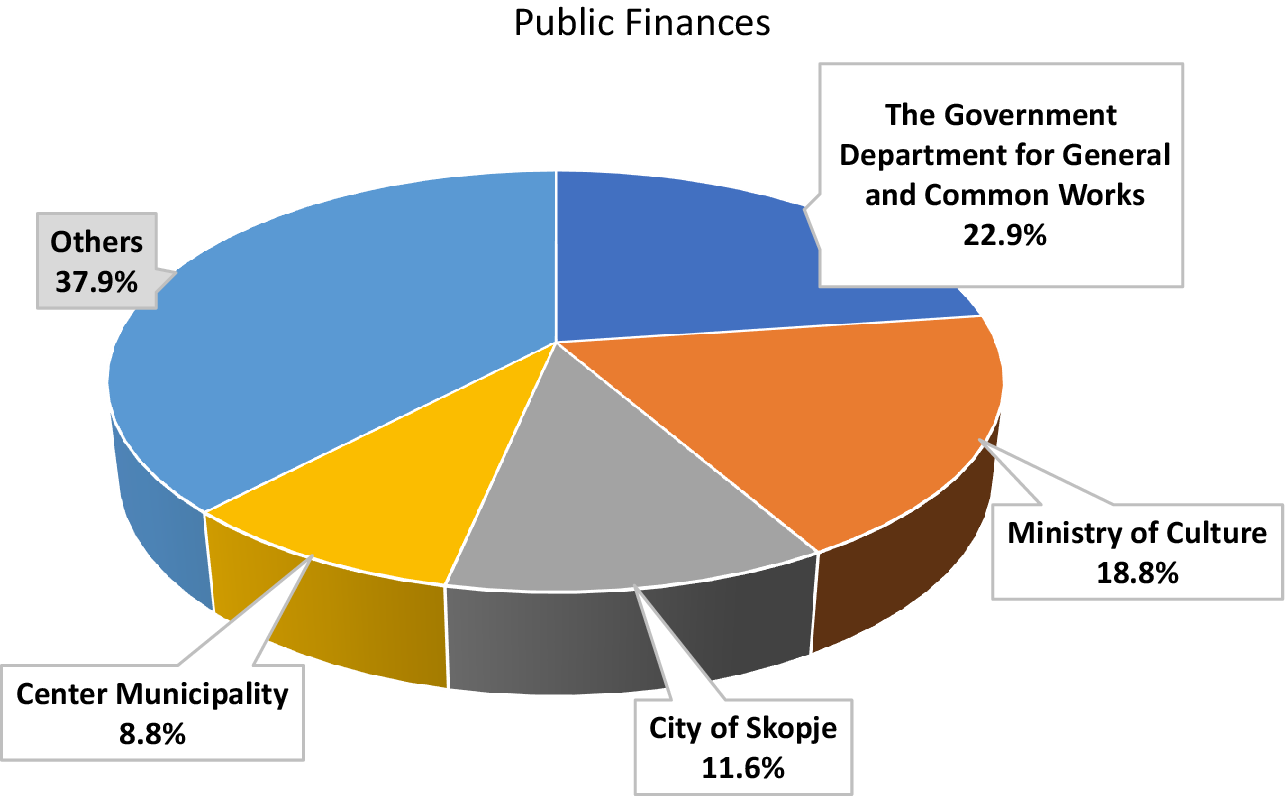

The official database of Skopje 2014 ( BIRN ) shows that the project does not officially exist. According to architect Ognen Marina (Interview 2021), Skopje 2014 did not appear with either an urban plan with defined phases or deadlines characterizing spatial revamps of such a magnitude. Instead, it was promoted and based on the visualization presented to the public in 2010. Despite the lack of a coherent plan, the state executed the project almost entirely according to the plans, involving the entire logistical power of the state, which in some respects is a characteristic of urban megaprojects (del Cerro Santamaria Reference Del Cerro Santamaria2019). Its costs eventually reached the amount of 680 million euro of public money, clearly surpassing the initially declared amount of 80 million euro.Footnote 8 Almost all state departments (figure 1) invested in Skopje’s makeover. They either provided administrative support or transferred financial means to finance the project (Interview with Chausidis, Reference Chausidis2021).

Figure 1. Public Finances of Skopje 2014, source BIRN : http://skopje2014.prizma.birn.eu.com/

From the beginning, the whole process was characterized by ignoring existing laws regulating urban planning and attempts to undermine institutional procedures (Grcheva Reference Grcheva2018). According to Marina,

The urban planning process requires a complex involvement of different institutions, procedures, and revisions. The urban planning system serves the purpose of adequately executing the process and defining the responsibilities for such an undertaking. This was not the case with Skopje 2014 by any means. (Interview with Marina, 2021)

Many objects were included in the official program for memorials only after the contract for their construction had been reached (Blazhevska Reference Blazhevska2015), suggesting a prearranged procedure. In some cases, the decision for monuments was adopted after the monuments was already installed (Interview with Chausidis, Reference Chausidis2021). Much of the process was a result of a chaotic situation in which “there were no experienced and professional architects” (Blazhevska Reference Blazhevska2015).

Furthermore, the promoters quickly passed new laws and regulations while bypassing existing rules and institutions. This particular strategy of subversion of formal institutions aimed to preclude any opposition to the dominant party and its agenda. This was the case with the decision to circumvent the national parliament, an institution through which decisions for the construction of monuments of national or cultural significance must be accepted by a double majority, meaning that minorities – in this case, Albanian deputies – would have to consent to building a monument of this rank. It seems that the government was aware that ethnic Albanians would not support this and instead decided to run the process through the municipality of Centar, where they held a political majority (Stojancevska and Jordanovska Reference Stojancevska and Jordanovska2016).

Strongman in Command: “Skopje 2014 Was My Idea” – The Role of Nikola Gruevski in Skopje’s Makeover

As discussed, authoritarian leaders have commonly built cities to advance their political and ideological agenda (Cavalcanti Reference Cavalcanti1997; Vale Reference Lawrence1992). When it comes to hybrid regimes, we know less about the role of an individual authority – or what Bieber (Reference Bieber2020) labels as strongmen of the new authoritarianism in the Western Balkans – in designing urban spaces, especially the capacity to influence the development of urban megaprojects directly. These rulers rely heavily on an informal web of control, subverting constitutionally established practices (Kapidžić Reference Kapidžić2020).

Gruevski’s interest in urban spaces dates back to when he pushed the initiative to build the Millennium Cross as minister of finance. The key difference is that, after 2004, he established himself as the new leading figure of the VMRO-DPMNE. Thus, once the VMRO-DPMNE gained access to state resources in 2006, Gruevski, now prime minister, wasted no time in redesigning Skopje’s urban character. Moreover, the new political role and the dominance of VMRO-DPMNE endowed him with access to state resources and confidence to take the role of a gatekeeper, appearing as an unofficial architect and planner, as he often gave design notes and suggestions on the placement of specific objects. Leaked recordings reveal how Gruevski and the Minister of Transport Mile JanakieskiFootnote 9 informally managed the process:

Can you stop by to quickly choose something? (Gruevski) – Now? (Janakieski) – No, stop by for 10 minutes tomorrow… and choose some baroque from Vienna, Paris, you can find baroque everywhere. And make sure that it’s defined in the tender documentation how the façade ought to look like. Make sure to put a photo as well. (Spasoski Reference Spasoski2016)

The conversation between these former leading political figures, as well as other conversations of a similar nature regarding spatial planning in Skopje, indicate actions of a highly informal nature conducted by a small circle of individuals representing VMRO-DPMNE and critical state structures. Moreover, it reveals a lack of concern for systematic and inclusive spatial planning. The pace and informality mattered, enabling the government to construct most of the announced objects at a much faster tempo. Moreover, it showcases the crucial role that Gruevski played, emphasized by the then Minister of Culture Elizabeta Kančeska-Milevska, who stated in a leaked recording that “the law protected some facades in the city. The Prime Minister [Gruevski] said that we should deny them this status, so that we can do what we want” (Jordanovska Reference Jordanovska2015a), which effectively meant refurbishing the facades.

The former prime minister did not refrain from publicly defending the project and reiterating that the project was his idea (MINA 2012). According to Gruevski, Skopje waited too long to become the metropolis in the region after being marginalized by the previous systems (Skopje Prodolzuva 2013). Proclaiming himself as the author of Skopje’s makeover, Gruevski attempted to create an image of a strong transitional leader in the city where, in his words, nothing has been built since the independence (Skopje Prodolzuva 2013).

Certainly, the involvement of Nikola Gruevski was of significant importance, as he sensed the political opportunity to rebuild Skopje and actively engaged as a planner. At the same time, the whole operation turned out to be much more complex, involving a network of various non-state groups that participated in rebuilding the city center, be it by directly engaging in commissions designed to carry out the project or by supporting the project through media, cultural, and academic events.

“Skopje 2014 Should Have Happened Earlier”: The Legitimization Strategies and the Contribution of Non-State Groups

Besides relying on state resources, the revamp of Skopje had a lot to do with building a complex network that incorporated various non-governmental groups and individuals, from architects, journalists, and engineers to business establishments, civil society groups, and party sympathizers. According to an interview with activist M from the organization Ploshtad Sloboda, many intellectuals who were close to the political right resorted to smearing campaigns to discredit their organization and demotivate activists from taking a stand against the revamp (Interview 2021).

Many of the project’s supporters took part in institutional commissions tasked to decide on building a respective object. As Chausidis emphasizes, “all of them are VMRO,” implying that members of these commissions were either supporters or members of the conservative party (Interview with Chausidis, Reference Chausidis2021). Some of them presided over civil society organizations linked to the idea of the historical and ethnonational continuance with ancient MacedoniaFootnote 10 and promoted and defended Skopje 2014 in academic workshops, artistic exhibitions, and documentaries (Chausidis Reference Chausidis2017). Although the VMRO-DPMNE held all centers of power, the legitimization strategy was needed to justify arguably the most controversial project in the country’s history, developed in a competitive political environment.

Between 2010 and 2016, North Macedonian state television produced around 70 documentaries on themes dealing with North Macedonia’s nationhood, portraying the historical processes through the victimization narrative of the Macedonian nation (Apostolov and Chausidis Reference Apostolov and Chausidis2017).Footnote 11 Among the newly produced documentaries was the series Skopje Prodolzuva, developed by architects and intellectuals who supported the idea of redeveloping the capital. The documentary consists of 14 episodes dealing with Skopje 2014 and the historical context of the city, advancing the idea of the historical marginalization of the capital.Footnote 12

Furthermore, workshops, cultural events, and media appearances were organized to promote the idea that Skopje 2014 should have happened in the 1990s when the country gained independence (Dnevnik 2010). Among the participants were members of the urban commissions mentioned above (Chausidis Reference Chausidis2017). Many of them publicly supported the VMRO-DPMNE government during the severe political crisis in 2015 and 2016, as they were mobilized in civil society organizations marching daily across the country. They celebrated Skopje 2014, linking its emergence to the arrival of a new political right and Gruevski as a “new political generation.”Footnote 13 According to the artist Aco Stankovski, the Macedonian “martyrs” have obtained the chance to govern and finally build something in the city after 50 years of being in the shadows of other regional capitals and powers (Skopje Prodolzuva 2013). In a similar tone, the architect and supporter of Skopje 2014 Vangel Bozinovski noted that the independence of North Macedonia provided the country with an opportunity to discover its rich architectural legacy, which was subdued during socialist Yugoslavia: “We started to finally understand that there is a rich legacy and that we are not a marginalized architecture in the framework of the Yugoslavian system (Skopje Prodolzuva 2013).” The same narrative was propagated by the state and Gruevski, showcasing a coordinated and united front.

These events and public appearances served as a channel to promote another view: claiming that neoclassicism and baroque have been part of Skopje’s history, so Skopje 2014 builds on this architectural legacy. In this way, a counter-narrative was created to respond to the accusations that the project fabricates history and creates traditions that never existed. According to Danilo Kocevski, many buildings had elements of baroque, classicism, and neoclassicism in old Skopje (19th/20th century), such as the French school, the franco-Serbian bank, or the archdiocese of Skopje, among others (Makfax 2010a). The architect Vangel Bozhinovski, delves deeper in the past, claiming,

Baroque is deeply rooted in the tradition of Macedonian architecture. The square in baroque expression in front of the largest Catholic “cathedral St. Peter“ in Rome is a copy of the square in Jarash built by Macedonian architects during the campaign of Alexander III of Macedon. The domes of St. Ives at the Sapienza in Rome are a copy of the architecture created by Macedonianism, which in European culture is known as Hellenism. (Makfax 2010a)

The view that Macedonian ethnonational roots go deep in the past was supported by non-governmental organizations, which have donated several monuments now standing in the city center.Footnote 14 Thus in 2013, after the VMRO-DPMNE lost power in the Centar municipality to Andrej Zernovski, an opponent of Skopje 2014, the process of donating monuments gained momentum, involving donations from civil society organizations known to be close to VMRO-DPMNE and the idea of historical legacy with ancient Macedonia.Footnote 15 The donated monuments had the purpose of avoiding the procedure regarding the spending of public money (Chausidis Reference Chausidis2017).Footnote 16 The organizations that donated monuments have received material help from the state, thus revealing the tie between the state and respective associations (Jordanovska Reference Jordanovska2015c).Footnote 17

In addition, this network extended to the business sector, which plays a principally important part in the consolidation of competitive authoritarian regimes, where incumbents often use the state’s monopoly of power to access the private sector (Levitsky and Way Reference Levitsky and Way2010, 10). In the case of the reconstruction of Skopje, the largest construction companies and architectural offices took the most significant share of the project and, on some occasions, donated monuments. The monumental new headquarters of VMRO-DPMNE was financed by the largest construction company “Beton,” which built over 30 objects as part of Skopje 2014 and won contracts worth over 200 million euro, which is about a third of the amount allocated to the entire project (Apostolov Reference Apostolov2017). Yet, the state dictated the quality of the relationship between the political and economic subjects. Mattioli notes that the state in North Macedonia had a significant influence over the private sector, the representatives of which found themselves in precarious positions “if they were not directly part of the VMRO-DPMNE regime” (Mattioli, Reference Mattioli2018, 575). For example, in one of the leaked recordings, Gruevski had ordered a minister to demolish a building owned by a political opponent and businessman who previously was close to the party but then turned against the VMRO-DPMNE (Rizaov Reference Rizaov2015). According to Chausidis, this move was a message to the political and business community, aiming to head off any resistance to the project and the party (Interview with Chausidis, Reference Chausidis2021), which brings to mind similar processes in Putin’s Russia (Kinossian and Morgan Reference Kinossian and Morgan2014).

Subversive Strategies, Coercion, and Co-optation

The aspects of coercion and violence, while not as striking as in full authoritarian regimes, were exploited to prevent the rise of resistance against the revamp of the capital. In 2009, a young group of architects protested the planned building of a church in Skopje’s main square (Ignatova Reference Ignatova2009). According to D, one of the founders of the organization Arhi Brigada that contested the object, they were against building any object at that location on the main square, not specifically the church (Interview 2021). The protest ended eventually in violence, as over a hundred counter-protesters, who eventually showed up in much larger numbers and were supported by the state-backed media, resorted to violence against the students, which occurred right in front of the police, who hesitated to intervene. The minister of internal affairs rejected to condemn the violent turn of the events (Petkovski and Nikolovski Reference Petkovski and Nikolovski2016, 174), indicating a systematic effort to crack down on the protest. Although the protests were of a relatively small scale and did not pose any threat to the local and national government, the state decided to act, thus preventing any augmentation of the discontent. Similarly, in 2013, the state used its monopoly on violence as it deployed over one hundred police officers and ten vehicles to disperse a small group of activists protesting against the building of a baroque building in the city center (Okno 2013).

Such actions by the state are not uncommon in hybrid regimes, especially in capital cities where massive resistance can take a more visible, supported, and organized form (Uitermark, Nicholls, and Loopmans Reference Uitermark, Nicholls and Loopmans2012; Goodfellow and Jackman Reference Goodfellow and Jackman2020; Glaeser and Steinberg Reference Glaeser and Steinberg2017). Seemingly, the conservative government was aware of this and made sure to prevent the emergence of any resistance to the project. Facing the state’s power and how the government politicized the resistance, the Arhi Brigada altered the form of activism by organizing public debates rather than taking the streets (Interview with D, 2021).

Alongside the coercive tactics aiming to demobilize activists, the government relied on strategies of subversion, which typically occur in the situation of a “vertically-divided authority” (Resnick Reference Resnick2014). This was the case with the municipality of Centar, which was won by the opposition in the local elections in 2013. Once VMRO-DPMNE lost power in Centar, the procedure for building monuments was quickly assigned to the jurisdiction of the Mayor of Skopje, ruled by the conservative party. This enabled the promoters to subvert the authority of the Centar municipality and keep the project going according to the plan.

It remains puzzling why the Albanian partner in the government, the Democratic Union for Integration (DUI), did not confront the project, especially in light of the initial reactions by the incumbent Mehmeti (DUI) who condemned the revamp as not doing justice to the multicultural character of Skopje (Makfax 2010), as well as the fact that the majority of Albanian citizens disapproved of the undertaking (Kolozova et al. Reference Kolozova, Lecevska, Borovska and Blazeva2013; Blazhevski Reference Blazhevski2021). While a significant reaction against Skopje 2014 as a whole did not occur,Footnote 18 the reasons for the absence of a reaction can be backtracked to the co-optation politics between the coalition partners, VMRO-DPMNE and DUI. In this context, Goodfellow and Jackman’s concept of “co-operative empowerment” is helpful, as it relates to a situation in which those targeted are not simply bought off but they “manage to gain some increased leverage for their own agendas through this interaction” (Goodfellow and Jackman Reference Goodfellow and Jackman2020, 22). The same year Skopje 2014 was presented, the Skanderbeg square project, representing Albanian nationalism, was announced, signaling a possible compromise between the coalition partners (Véron Reference Véron2021). In this way, both parties exercised power not through conflict and resistance but through a co-optive and opportunistic strategy that helped implement their urban plans (Goodfellow and Jackman Reference Goodfellow and Jackman2020).

Urban Design Strategies and Party-Building

Whether architectural projects are seen as debacles or successes, they become associated with the regime “politically and perhaps iconographically” (Vale Reference Lawrence1992, 51). The authoritarian implementation of the Skopje 2014 enabled the conservative party to leave its ideological mark on the urban space. Skopje 2014 has incorporated not only the nationalist elements but also the illiberal aspects of the conservative party.

The monument to one of the most controversial figures from local history, Andon Lazov Janev, who, according to historical sources, was involved in terrorist activities in the early 20th century, was erected with him wearing a military uniform and holding a knife right next to the Supreme Court – an institution and justice system that was under the heavy influence of the conservative government (Gjuzelov and Hadjievska Reference Gjuzelov and Hadjievska2020). The pronounced masculinity in the form of dominant male leadership reveals the exclusionary character of the project (Véron Reference Véron2015, 192). For example, the monument to Philip II rises above the statues of his family, conveying patriarchic views of the dominant male figure, which resemble the conservative-illiberal values embedded in the normative ideology of VMRO-DPMNE’s ideological program called Doctrine. This vision of a closed, predestined, hierarchical society expands to other social categories. There are hardly any monuments to women, except for Olympia, the mother of Alexander the Great, whose social function has been determined by the authorities – she is depicted as a pregnant mother holding three children (Kocevska Reference Kocevska, Jovan and Todorov2020). The monument to Olympia thus symbolizes the predetermined social position of women and the so-called “third child policy,” designed by Gruevski’s government (Stefoska and Stojanov Reference Stefoska and Stojanov2017). In Marina’s view, this “narrative” model of architectural expression is, in essence, authoritarian since it is one-dimensional, and, as such, it excludes the possibility of an alternative interpretation (Interview with Marina, 2021).

The practices of exclusion of the large Albanian and Roma communities in the project further demonstrate the illiberal dimension of the revamp. The developers of Skopje 2014 did not adjust the new architecture to the existing cultural pluralism in the city. Instead, they promoted the political and cultural dominance of ethnic Macedonians. The symbolic display of group dominance undermines the post-conflict processes and the OFA (Vangeli Reference Vangeli2011, 24), which guarantees the political inclusion of Albanians.

Furthermore, the attempt to establish dominance in the capital through urban design is discernible in how the VMRO-DPMNE government dealt with the modernist urban legacy, seen as the most significant architectural hallmark of post-earthquake Skopje. Alternatively, the political right views the same legacy as an aberration and an “undesirable heritage” (Dimova Reference Dimova2019). This perception of the communist legacy can be identified in many post-socialist cities (Forest and Johnson Reference Forest and Johnson2002; Diener and Hagen Reference Diener and Hagen2013). The manner in which the conservative government transformed the meaning of modern architecture in Skopje led me to categorize this development as soft and hard strategies for dealing with the “socialist” architecture and past.

The former relates to the strategy of putting up a new set of neoclassical buildings in front of the existing objects, thus diminishing their architectural value (figure 2). The latter relates to refurbishing the original façade from brutalist to neoclassical style, thus eradicating the original architectural language of the building (figure 3). Besides the fact that they devalue the architecture in their own specific way, both strategies tend to promote new power and ideological hierarchies in the urban space. This process is critically seen by part of the architectural community as an attempt to eradicate all that is socially and politically accepted, as if there was nothing there before (Marina Reference Marina2016), drawing attention again to the authoritarian dimension of Skopje 2014. In particular, the government building (originally the Central Committee of the Communist Alliance), built in the 1970s, was a specific structure accessible to the public, thus symbolizing an idea of openness to the citizens. As part of the project Skopje 2014, it was completely refurbished into a neoclassical object, triggering criticism (Dimova Reference Dimova2019). In addition, the government decided to put up a fence around the building, negating the spatial and symbolic openness the object had represented, and instead promoting the illiberal model of urban planning:

The transformation of this building within the “Skopje 2014” project meant not just the substitution with the new façade in eclectic neo-baroque style but most importantly the addition of the impenetrable fence around the building preventing the citizens to use the public space and emitting a strong message of exclusion as a dominant spatial practice of the political elite rattled with its own existence and identity. (Marina Reference Marina2016, 312)

Figure 2. National Opera and Ballet, a hallmark of post-earthquake Skopje, now concealed behind the new objects. Photo by the author.

Figure 3. Putting on a new neoclassical façade, covering the modern architecture. Photo by the author.

These urban design strategies and the narratives accompanying it are tied to VMRO-DPMNE and the conservative right in the country. The party sought to convey its central ideological messages and make itself more visible through the urban space and the iconography promoted in the capital. The ideological elements of Skopje 2014 are part of VMRO-DPMNE’s agenda, and some were normatively embedded in different ideological programs or simply operating through different channels (Malešević Reference Malešević2006), such as architecture in this case.Footnote 19 The anti-communist narrative, ethno-nationalism, and the aspect of religion and family have been central to the conservative party. The ancient narrative has been part of the national right narrative since the 1990s and became integral to the ideological projects implemented during Gruevski’s era. In this way, the capital became a platform through which VMRO-DPMNE conveyed its ideological principles, symbolizing not just an idea of national identity or a nation-branding attempt but equally the political ideology of the conservative movement in the country – hence, the term party-building, introduced to direct attention to the source of ideological production and be more specific about the agency and ideology behind it. This is especially evident in the case of Skopje 2014 since the conservative party networks were pivotal in micromanaging the project, while the party’s symbolic resources served as an ideological driver, now embodied in the design of contemporary Skopje.

Conclusion

This article examined how various nondemocratic strategies operated in redesigning Skopje. Carrying out the plans required building a complex and comprehensive network consisting of different state institutions, political parties, and the involvement of civil society organizations and local intellectuals to bypass formal procedures and democratic institutions. This had a lot to do with the gigantic size of Skopje 2014 and the competitive nature of the political dynamic in the country. In addition, the new urban plan was micromanaged by the strongman Nikola Gruevski. The centralization of power on all levels enabled the state to prevent any resistance to the project and disseminate its illiberal ideological content. Despite many calls for corruption and non-transparency, the state persecution did not open a single case against the project. The judiciary system was under the control of the VMRO-DPMNE, and, according to democratic indexes (Ristevska Reference Ristevska2015), the judiciary was permanently in decline between 2007 and 2015.

Conceptually, this study seeks to direct attention to competitive authoritarianism and how it shaped the urban megaproject Skopje 2014. The risk of regime change in a traditionally competitive political landscape put pressure on the government to speed up the organizational aspect of the project, characterized by highly non-transparent procedures and partisan involvement. Furthermore, the fact that these regimes can still be confronted by political and civil opposition and regulations protecting arbitrary decisions led to the creation of an extensive network that stood instrumental in implementing and defending the massive undertaking. This organizational effort had a task to bypass existing procedures, legitimize the project in the public eye, and subvert democratic institutions. These processes – the arbitrary expeditious planning, the extensive mobilization, and the informal networking – were closely related, empirically overlapping, and essential in constructing Skopje 2014. Further, this article introduced the concept of party-building to draw attention to the agency, the power organization, and the source of ideology. It suggests that the promoters used the party’s symbolic resources to make the VMRO-DPMNE and the national-conservative narrative more visible in the capital.

From the perspective of authoritarian processes, Skopje 2014 contributed to further autocratization of the state. The project made the regime not only more visible through the promoted iconography but it also played a significant role in authoritarian consolidation and democratic backsliding of the state, as the entire operation involved various institutions, the subversion of established procedures, and the creation of a large informal support web.

Empirically, the study showcased that the former government planned the project well ahead of the NATO summit in 2008, thus calling into question the view that Skopje 2014 and the “populist and nationalist shift” (Beyer Reference Beyer2021) were caused by the veto in Bucharest (Kolozova et al. Reference Kolozova, Lecevska, Borovska and Blazeva2013; Dimova Reference Dimova2013, 125). The research also points to certain limitations of geopolitical nationalism in explaining the emergence of the project. The conflict over the name issue was shaping North Macedonia’s politics well before Skopje 2014, culminating with Greece’s economic embargo in the 1990s. Nevertheless, this development did not cause a shift in cultural politics, as we saw after 2006. Hence, this article draws attention to the different processes to be considered, such as the rise of the new political right and the authoritarian shift that enabled the “VMRO’s revolution” (Kostova Reference Kostova2013). Accordingly, the research brings attention to the importance of state and local institutions as critical assets that allowed the party to undercut established practices, which is somewhat overlooked in the literature on North Macedonia’s populism and nationalism. While nationalism and the nation-building attempt are, without a doubt, among the essential ideological elements, the expression of ethnonational ideology was dependent on centralized and arbitrary processes that made this project possible. Nationalism, like any other phenomenon, does not exist on its own. It is an ideology needing permanent reproduction, which occurs through interaction with other social phenomena, institutions, or power organizations. In the case of Skopje 2014, the authoritarian processes smoothed the way for disseminating the narrative glorifying North Macedonia’s nationhood.

Acknowledgements

I sincerely thank the anonymous reviewers for providing excellent comments. I would also like to thank Florian Bieber and Christoph Breser for giving valuable suggestions on an earlier draft of this article.

Disclosures

None.