Many low- and middle-income countries in Latin America are experiencing a double burden of malnutrition, characterized by the persistence of undernutrition coupled with dramatic increases in the prevalence of overweight/obesity( Reference Mbowe, Diaz and Wallace 1 – Reference Kain, Cordero and Pineda 3 ). The prevalence of overweight/obesity in Latin American adolescents ranges from 18·9 to 36·9 %( Reference Rivera, de Cossío and Pedraza 4 ) and reflects a notable shift from traditional diets to a greater intake of nutrient-poor, energy-dense foods, such as sugar-sweetened beverages (SSB)( Reference Kain, Cordero and Pineda 3 , Reference Uauy and Monteiro 5 ).

Latin Americans are among the greatest consumers of SSB globally( Reference Singh, Micha and Khatibzadeh 6 ). For instance, Guatemalan females and males consume an average of 2·7 and 2·9 SSB servings/d, respectively( Reference Singh, Micha and Khatibzadeh 6 ). The high frequency of SSB consumption in Latin America, and Guatemala particularly, is concerning, given the associations between SSB intake and increased risk of overweight/obesity( Reference Malik, Schulze and Hu 7 – Reference Harrington 13 ), lower intake of micronutrients( Reference Frary, Johnson and Wang 14 – Reference Vartanian, Schwartz and Brownell 17 ) and the development of dental caries( 18 – Reference Touger-Decker and van Loveren 22 ). These factors underscore the need to examine adolescents’ SSB consumption and identify the factors that promote SSB intake.

Schools represent an important area of influence for adolescents, given their population coverage and the amount of time youth spend in school. School-based interventions may represent a promising strategy to address the ‘double burden’( Reference Letona, Ramirez-Zea and Caballero 23 , Reference Pehlke, Letona and Ramirez-Zea 24 ). However, few studies have examined the school food environment in Guatemala and its potential influence on students’ diets. These data could inform culturally relevant school-based interventions to decrease youths’ SSB intake at the population level.

The present pilot study sought to examine SSB intake in a sample of Guatemalan adolescents, identify individual-level characteristics associated with SSB consumption and describe school characteristics that may influence students’ SSB intake.

Methods

Study overview

The current study used data from a convenience sample of schools in Guatemala City that participated in the COMPASS Guatemala pilot study during the 2014/15 school year( Reference Bredin, Chacon and Barnoya 25 ). Details on COMPASS and the Guatemala pilot study can be found online (www.compass.uwaterloo.ca) and in print( Reference Bredin, Chacon and Barnoya 25 , Reference Leatherdale, Brown and Carson 26 ).

Participants

Four secondary schools participated in COMPASS Guatemala. Schools 1 and 2 were public (i.e. students attend for free), while Schools 3 and 4 were private (i.e. students paid tuition). All students enrolled in these schools (n 1359) were eligible to participate, and the participation rate was high (n 1277, 94·0 %). We removed 235 (18·4 %) participants from analyses due to missing data; however, we included those with missing BMI data. The final sample comprised 1042 participants.

Data collection tools

School- and student-level data were collected through the COMPASS school environment application (Co-SEA) and the COMPASS student questionnaire (Cq), respectively( Reference Leatherdale, Bredin and Blashill 27 , Reference Bredin and Leatherdale 28 ). The process of adapting and evaluating these tools in the Guatemalan context is described elsewhere( Reference Bredin, Chacon and Barnoya 25 ). COMPASS staff used the Co-SEA to assess school infrastructure by recording this information via notes and photographs. The Cq is a paper-based questionnaire that students completed during class, comprising questions on demographic characteristics and several health behaviours.

Outcome, control and potential explanatory variables

Participants’ responses to the following three Cq questions reflect the three outcome measures: ‘On a typical school day (Monday to Friday), on how many days do you do the following: (i) drink soft drinks (e.g. soda, fruit drinks, Gatorade, etc.). Do not include diet or sugar-free drinks; (ii) drink energy drinks (e.g. Red Bull, Monster, Adrenaline, etc.); and (iii) drink coffee or tea with sugar (e.g. cappuccino, frappuccino, iced tea, iced coffees, etc.)?’ These questions are similar to those asked in the Canadian Cq, although we modified the examples to reflect drinks that are commonly available in Guatemala.

We reviewed data collectors’ Co-SEA photographs and notes to examine the presence of water coolers/fountains and SSB industry-sponsored food kiosks within the schools. School administrators confirmed the presence/absence of these facilities within their schools.

We treated gender, grade, weight status (i.e. BMI (kg/m2) category based on reported height and weight and WHO classifications, adjusted for age and sex( 29 )) and school type (private, public) as control variables. The Guatemalan secondary school system comprises three ‘basic grades’ and two ‘professional training’ grades, which we denoted as grades 1–5, representing adolescents aged 13–18 years. We considered school type as a marker of participants’ socio-economic status, consistent with previous research( Reference Bermudez, Toher and Montenegro-Bethancourt 30 , Reference Montenegro-Bethancourt, Doak and Solomons 31 ).

We selected potential explanatory variables based on a priori hypotheses and previous literature. They included tobacco, marijuana and alcohol use, sedentary behaviour, physical activity, bullying victimization and weight goal. We defined these variables in a manner that is consistent with previous COMPASS studies( Reference Herciu, Laxer and Cole 32 – Reference Minaker and Leatherdale 36 ). We also considered four food purchasing behaviours as potential explanatory variables, which reflect participants’ weekday frequency of purchasing lunch and snacks from various food outlets on and off school property.

Data analysis

We used descriptive statistics to examine variation in participants’ mean number of weekdays of consuming each SSB type across school- and individual-level sociodemographic and behavioural variables, and univariate Poisson regression analyses to identify the significance of this variation.

We developed a separate joint Poisson regression model for each SSB type using a two-step process. First, we ran a series of univariate analyses to identify if each potential explanatory variable was independently associated with each outcome. We removed variables that were not statistically significantly (P>0·2) from the analysis. Second, we included all significant variables from this first screening stage in a multivariate model and used backward selection to drop the least significant variable, until all variables were statistically significant (P<0·05). We forced control variables into the models. We performed statistical analyses using the statistical software package SAS version 9.4.

Results

Drinking-water from fountains/coolers was inaccessible for students at Schools 1 and 2, while Schools 3 and 4 contained purified water coolers for students and staff. Schools 1, 2 and 4 contained industry-sponsored food kiosks that students could access during lunch and school breaks. The Co-SEA data demonstrated the presence of the SSB industry in schools through advertisements, products available for sale and donated goods. For example, Schools 2 and 4 displayed athletic trophies featuring Coca-Cola® and Pepsi® logos.

Participants reported consuming soft drinks, sweetened coffees/teas and energy drinks an average of 2·58, 2·40 and 0·58 d in a typical school week. Few participants reported no use of soft drinks (n 210, 20·2 %) and sweetened coffees/teas (n 308, 29·6 %) in a typical school week; however, 74·2 % of participants (n 773) reported no use of energy drinks. Similarly, daily reported use was relatively common with respect to soft drinks (n 293, 28·1 %) and sweetened coffees/teas (n 321, 30·8 %), although rare with energy drinks (n 40, 3·8 %).

Table 1 presents the average weekday frequency of SSB consumption across school- and individual-level characteristics. There was significant (P<0·05) variation in participants’ frequency of SSB consumption according to school, school type, grade, alcohol use, sedentary behaviour, weight goal and the food purchasing variables, across all three SSB outcomes.

Table 1 Frequency of sugar-sweetened beverage consumption, according to school- and individual-level sociodemographic and behavioural characteristics, among secondary-school students participating in COMPASS Guatemala (n 1042), 2014/15 school year

* Number of weekdays (0–5 d) that participants reported consuming beverage.

† P values derived from univariate Poisson regression analyses including each outcome and each explanatory variable.

‡ Participants with missing weight status (n 375) were included in analyses, although not shown here.

§ Number of weekdays (0–5 d) that participants reported the food purchasing behaviour.

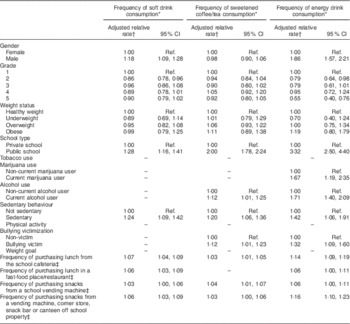

Table 2 shows the adjusted relative rates derived from the Poisson regression analyses for the final models. Common correlates of SSB consumption across all models include school type, sedentary behaviour, frequency of purchasing lunch in the cafeteria, and frequency of purchasing snacks from a vending machine on and off school property. Participants who purchased lunch or snacks from various food outlets at a greater frequency had a significantly higher rate of SSB consumption across all three categories, as did public-school students. For example, the relative rate of 1·28 denotes that public-school students consume soft drinks at a 28 % greater rate than private-school students (i.e. in terms of weekdays reporting soft drink consumption), controlling for all other variables.

Table 2 Individual-level sociodemographic and behavioural correlates of weekly consumption of three varieties of sugar-sweetened beverage among Guatemalan secondary-school students participating in the COMPASS study (n 1042), 2014/15 school year

Ref., reference category; – denotes no significant effect in model(s), variable was excluded from model through backward selection.

* Number of weekdays (0–5 d) that participants reported consuming beverage.

† Rates adjusted for all other variables in the column; values represent the rate of weekday beverage consumption (i) relative to the reference category (in the case of categorical explanatory variables) or (ii) associated with a one-unit increase in the independent variable (in the case of count explanatory variables).

‡ Number of weekdays (0–5 d) that participants reported the food purchasing behaviour.

Discussion

The present study underscores the high rate of SSB consumption among a sample of Guatemalan adolescents, socio-economic differences in consumption, and adolescents’ food purchasing behaviours as important predictors of SSB intake.

Participants reported a high consumption frequency of soft drinks and sweetened coffees/teas. Guatemala is a global leader in coffee-growing, and unlike in Western nations, coffee is commonly served to young children and toddlers in Guatemala( Reference Dewey, Romero-Abal and Quan de Serrano 37 , Reference Engle, VasDias and Howard 38 ). Previous research has identified that sweetened coffee is the most commonly reported consumed beverage among Guatemalan schoolchildren, largely due to cultural tradition( Reference Montenegro‐Bethancourt, Vossenaar and Doak 39 ). Prevention efforts should focus on decreasing youths’ consumption of soft drinks, since they are the most popular SSB among adolescents and have limited cultural significance (i.e. unlike coffees/teas).

Public-school participants reported a significantly higher rate of SSB consumption than private-school participants across all beverage categories. The discrepancy may reflect, in part, the lack of access to water fountains/coolers we observed within public schools. The lack of this healthy alternative may encourage public-school students to purchase other, less healthful beverages in school. Other research from Guatemala has identified low water consumption among marginalized sub-populations due to limited access to clean drinking-water, perceptions that tap water is unsafe to drink and the costliness of bottled water( Reference Nagata, Barg and Valeggia 40 , Reference Makkes, Montenegro‐Bethancourt and Groeneveld 41 ). These findings underscore the importance of considering health equity in population-level interventions designed to reduce adolescents’ SSB intake.

We identified a positive correlation between purchasing meals/snacks from school food outlets and SSB consumption, suggesting that the school food environment may encourage SSB intake. Many Guatemalan youth purchase products from school food kiosks, including those who bring a home-packed lunch to school( Reference Pehlke, Letona and Hurley 42 ). The Guatemalan Ministry of Education has attempted to prohibit the sale of SSB and other processed foods within schools( 43 , 44 ). While the present study did not explicitly examine the types of foods offered through these outlets, there is evidence that these regulations are largely unenforced, as many vendors offer a range of energy-dense snacks and beverages( Reference Pehlke, Letona and Hurley 42 , Reference Chacon, Letona and Villamor 45 ). Stricter enforcement of current regulations for school foods in Guatemala, or perhaps new regulations, may reduce access to and discourage consumption of SSB and other unhealthy products among students.

The present study identified the SSB industry’s presence in Guatemalan secondary schools via sponsored kiosks stocked with SSB, branded donated goods and advertisements. It is feasible that the availability of and exposure to SSB in school food outlets encourages students to consume these beverages, since they increase students’ access to these items and may also influence their food selections and perceptions of appropriate dietary choices( Reference Rideout, Levy-Milne and Martin 46 ). Research from North America has demonstrated the positive association between in-school SSB availability and consumption( Reference Park, Sappenfield and Huang 47 – Reference Mâsse, de Niet-Fitzgerald and Watts 51 ), although these associations have not been well explored in low- and middle-income countries. This research gap underscores the need for greater investment in research platforms like COMPASS in Guatemala and other low- and middle-income countries. Other research has identified that most food advertisements in food outlets within and surrounding Guatemala schools feature SSB, which increase youth’s exposure to these brands( Reference Chacon, Letona and Villamor 45 ). The presence of the SSB industry in Guatemalan schools suggests that the beverage industry is capitalizing on this unregulated environment to access a key subgroup of consumers. Collectively, these features contribute to a food environment that can undermine individual efforts to improve dietary behaviours.

The present study has many strengths, including providing valuable evidence on the extent of SSB consumption among Guatemalan youth. The large student sample size and inclusion of public and private schools enable comparisons across socio-economic groups. The study also contributed to the creation of a new research collaboration between Guatemalan and Canadian health researchers and research capacity building in a low- and middle-income country.

Our findings should be interpreted in light of the study’s limitations. First, the outcomes reflect conservative estimates of SSB intake (i.e. relative to data on volume or number of servings), since the unit of measure is number of ‘days’ and participants can consume numerous SSB daily. Second, the samples of participants included in the analyses v. removed were significantly different across several demographic variables (see online supplementary material, Supplemental Table 1); however, these groups did not vary significantly across outcomes measures. Third, sedentary behaviour and physical activity categories were based on Canadian guidelines, due to the lack of Guatemalan guidelines. While there were several efforts to evaluate the appropriateness and students’ comprehension of the Guatemalan Cq, we did not formally adapt the tool. Finally, the present pilot study included four schools, which may not represent other school environments in Guatemala.

Conclusions

Guatemalan adolescents frequently consume SSB. Adolescents’ purchasing from food outlets on and near school property represent important predictors of SSB intake. School-level interventions may be well poised to address the high rate of SSB intake among Guatemalan youth. Specific strategies include increasing the availability of free drinking-water to students, decreasing access to SSB, restricting SSB marketing and enforcing legislation surrounding the sale of SSB in schools.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: The authors wish to acknowledge Dr Ashok Chaurasia for his support with the statistical analyses. Financial support: The development of the COMPASS system was supported by a bridge grant from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) Institute of Nutrition, Metabolism and Diabetes through the ‘Obesity – Interventions to Prevent or Treat’ priority funding awards (S.T.L., grant number OOP-110788) and an operating grant from the CIHR Institute of Population and Public Health (S.T.L., grant number MOP-114875). The COMPASS Guatemala Study was funded by the Small Grants for Innovative Research and Knowledge-sharing from the International Development Research Centre (S.T.L., grant number 107467-027). S.T.L. is a Chair in Applied Public Health Research funded by the Public Health Agency of Canada in partnership with CIHR. J.B. receives additional support from The Foundation for Barnes-Jewish Hospital. These funders had no role in the design, analysis or writing of this article. Conflicts of interest: None. Authorship: K.M.G. and V.C. formulated the research questions. J.B. and S.T.L. designed the study. K.M.G. analysed the data and led the writing of the manuscript. V.C. drafted sections of the manuscript pertaining to the political environment in Guatemala. J.B. and S.T.L. revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript. Ethics of human subject participation: The study protocol was approved by Francisco Marroquin University Institutional Review Board and the University of Waterloo Office of Research Ethics. This is a non-experimental study.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980017001926