Introduction

In March 2019, the United Kingdom’s Reviewing Committee on the Export of Works of Art and Objects of Cultural Interest (RCEWA) considered an export application for a gouache miniature painting, titled The Spanish Armada off the Coast of England. Footnote 1 Held in a private collection, the owner had wished to export the item to the United States for sale when it came to the attention of the RCEWA. On assessment, the painting was found to be a “national treasure” on the grounds that it was uniquely connected with the history and national life of the United Kingdom and that it was of outstanding significance for the study of some branch of art, learning, or history, such that its departure would be a misfortune. The painting’s export was deferred (meaning that it was temporarily prohibited from leaving the country), and public cultural institutions were provided with the opportunity to purchase and retain it in the United Kingdom. It was subsequently bought by National Museums Northern Ireland and is now in the permanent collection of the Ulster Museum in Belfast. This is a story typical of the export control process for cultural objects in the United Kingdom, through which objects are declared “national treasures” in a bid to retain them for public accessibility. The impact of such decisions on object - and subject - relations will be explored through a critique of the process by which the determination of items as national treasures is made in the United Kingdom. This, and reframing the understanding of the very space of the determination, will be the focus of this article.

In the United Kingdom, there are innumerable cultural objects, ranging from J. M. W Turner’s Walton Bridges (1806) to the flag from Robert Falcon Scott’s sledge. Some of these items are housed in public collections and accessible in national and regional museums. Many are kept in private collections, allowing for varying degrees of accessibility, and some are locked away and hidden from view completely. Regardless of the status of the owners of these objects, where the items are located, or how easy it is to access them, they all fit a certain definition of “cultural object.” This definition suggests that more than a purely individual interest exists in them. The question of when – and how – some of these objects also qualify for the title “national treasure,” and what implications this designation has for the object, the owner, and the public, remains. Are national treasures a form of cultural object with inherent qualities that are waiting to be discovered, or are they cultural objects that are created as national treasures by virtue of their presence in a certain space? If the latter is the case, how is this space to be understood?

Utilizing Tony Bennett’s The Birth of the Museum and Eilean Hooper-Greenhill’s Museums and the Shaping of Knowledge, within which the museum space is implicitly a Foucauldian disciplinary institution that renders items “museum objects” rather than simply “cultural objects,” this article draws parallels between the institutional space of the disciplinary museumFootnote 2 and the space in which national treasures are presently created.Footnote 3 The disciplinary museum model is somewhat outdated in current museological theory. The museum today is instead considered under what has been termed the “new museology.”Footnote 4 This new form of understanding shifts the role and position played by the museum in society – from dictating public taste, attitude, and behavior to a new way of collecting, curating, and display – as well as driving social justice and change outside of the bounds of the museum building.Footnote 5

This “new museology” is not purely object focused; it also aims to reconsider the role of the public and community, making these spaces more open, diverse, and accessible to a wider range of individuals. The disciplinary museum model – considered by some as “élitist, and of no use whatsoever to the majority of people”Footnote 6 – is therefore no longer widely accepted as the form or composition of many museum institutions today. To quote Kenneth Hudson, “they were obsolete; and they ought to disappear, so that the public money could be spent to better purpose.”Footnote 7 The role of the disciplinary museum, as described by Bennett and Hooper-Greenhill, is the lens through which this article nevertheless examines how the National Treasure Space (NTS) operates at present. It will be posited that both the anachronistic disciplinary museum space and the NTS act as the curator and creator of cultural identity and as an institutional space in which decisions as to the current worth of an object to a nation are taken by those with the mandate to make them.

The first section will detail the process by which objects become national treasures, and how such designations are made, in order to ascertain how we can define the term “national treasure.” This will be followed by the argument that “national treasures” are not naturally occurring phenomena but, rather, constructed concepts that are applied to certain objects. It is this subjective creative element that opens up the possibility for an unregulated and ad hoc system of control, whereby the space in which these determinations are made should be subject to scrutiny. Where such a wide margin of discretion is present in heritage creation, the processes and individuals involved in such creation are key to the very understanding of such heritage objects. It is for this reason that an evaluation of the spaces in which these determinations are made is so significant. Finally, the constitution of the NTS will be explained, relying upon Bennett and Hooper-Greenhill’s genealogies of the disciplinary museum. The article will conclude by reiterating the key aspects of this institutional space, making recommendations for the democratization and diversification of this process, and highlighting areas for further research within this model of understanding. In doing so, it will examine the epistemological frameworks that underpin the workings of these institutions.

This article will take a UK-centric focus and will only discuss the creation of national treasures within the United Kingdom. While the jurisdictions of many other countries control the export of cultural objects – and regulate this export through the process of defining objects as national treasures – this article will consider the unique method through which the United Kingdom undertakes this task. The way in which the body responsible operates is not utilized as a blueprint for any other nation, and it is this distinctive process that this article critically examines.Footnote 8

The Disciplinary Museum

Throughout this article, reference will be made to the concept of the “disciplinary museum.” A term utilized by Hooper-Greenhill in Museums and the Shaping of Knowledge, it will be taken in this article to mean the form of museum institution, which occupies a similar purpose as Michel Foucault claims belongs to the prison or the asylum.Footnote 9 In such institutions, the focus is on the creation of “docile bodies” or the control of the population – either physically through incarceration, such as in prison, or through the prescription of the information and education that one is provided with, such as in a museum. Determining the museum as a disciplinary space is a form of museology that is now outdated. Museum practices shift, and the focus in recent years has been on the inclusivity of representation and knowledge forms that occur within these spaces. The model of the disciplinary museum, however, which is explored by both Bennett and Hooper-Greenhill in their references to the disciplinary spaces set out by Foucault, is a useful tool for the examination of the NTS.

While there are clear distinctions between the two – objects enter the NTS for a short while, and the museum space often for lengthy periods; cultural objects are “assessed” in the NTS whereas they are “preserved” in the museum space – there are striking similarities in the operation and rationale for these two spaces. Both the museum space and the NTS rely on the decision making of “experts” regarding the meaning and significance of objects before them; the interest that is being located in the cultural objects within both spaces is the interest of the public, meaning that private ownership or limiting access to one individual owner is no longer appropriate, and the motivation for both spaces is the retention and preservation of significant heritage.

Hooper-Greenhill drills down on the definition of the disciplinary museum, making it clear that what she means by this term (and what will be deemed to be the definition of the same in this article) is the form of museum space that dictates not only the type of objects that are on display but also how they are displayed, the messages they convey, the amount of access the public has been granted to them as well as the accepted forms of behavior, dress, and demeanor of the visiting public. Such museums create a “hierarchy” between the knowing and the unknowing, between the teacher and the taught, creating a space not simply of knowledge absorption but also of knowledge creation and dissemination: “[T]he ‘disciplinary museum’ gave rise to a complex interaction of both new and old subject positions that positioned the ‘visitor’ as beneficiary (the population enabled to know); the ‘curator’ as knowing subject with specialist expertise (who enables the knowing of others); and the subject-emperor, newly poised as the source of public benefaction and liberation.”Footnote 10

This article will contend that changes to a cultural object once it is made a national treasure take place in a similar disciplinary institutional space to that of the disciplinary museum – one that determines the nature of the object, the contexts in which it is understood (and also the contexts that are entirely disregarded in relation to the object), and whether the public – or a form of the public – will have the opportunity to be possessed of this item for posterity. This ultimately also impacts the future behavior or docility of those bodies that will come to view the item, viewing the object in a museum setting, as a museum object, and not as a private or personal possession. To consider an object in this context is to comprehend the manner in which to act with the object in this setting and to change the way in which the object is understood. By making an object a national treasure, the determiners of this designation also decide the future behavioral setting in which that object will be known hereafter.

The NTS will also be considered a comparative institution to the disciplinary museum, in that it operates in a similar manner, with a similar impact on the objects that come before it. As Charles Smith claims, “[t]he original intention behind the establishment of museums was that they should remove artefacts from their current context of ownership and use, from their circulation in the world of private property, and insert them into a new environment which would provide them with a different meaning.”Footnote 11 I have dubbed the institutional space in which these changes take place the ‘National Treasure Space’ (NTS). It will be explored in detail later in this article; first, I will outline the concept of a national treasure and the history of the export control process for cultural goods in the United Kingdom.

“National Treasures” Defined

“Cultural object” is an ambiguous term, an open or floating signifier whose definition shifts from person to person, institution to institution, and over time. How such items are classified in instruments (legal or otherwise) that inform or determine the regulation, protection, conservation of, and dealing in, such objects is therefore complex and significant. Where a lack of consistency exists between such regulations, particularly as they have evolved over time, this can prove problematic. While few would have difficulty identifying an early sixteenth-century painting such as The Spanish Armada off the Coast of England as a cultural object, drawing a clear line between a cultural object and a “national treasure” is not as simple.Footnote 12 Consider an Internet search for the terms “national treasure” and “national treasure definition.” The varying results would suggest that people (for example, Dame Judi Dench or David Attenborough, who usually feature high up on such lists), places (such as Stonehenge or Windsor Castle), and even a Disney film series featuring Nicolas Cage qualify as “national treasures.” Beyond this, however, grasping at a concrete definition of the term “national treasure” proves difficult.

Despite this lack of consistency, the United Kingdom’s control of the export of cultural objects, which puts in place procedures to try to prevent “national treasures” from leaving the United Kingdom, utilizes the term with consequences for all interested parties, including the owners, the public, and the state. In the early 1900s, heritage protection in the form of the retention of “national treasures” emerged as a concept. A 1915 report investigating the lack of retention of such objects by the Trustees of the National Gallery (headed up by Lord Curzon) warned: “From time to time, reports of the sale and removal of particular masterpieces long associated with this country appear in the Press; and a cry of lamentation is heard at each fresh diminution of the national treasure.”Footnote 13 From this report onwards, the use of the term “national treasure” to describe cultural objects worthy of retention by the state began to take off.

Throughout this period, debates in Parliament showed the increasing urgency with which regulation was desirable to address a perceived “exodus” of great art from the United Kingdom to the United States:

[T]he dispersal of our national art treasures, and their sale to foreign countries, and to the problem which confronts us of how to check the process before the nation suffers further irreparable loss. … I do not think it is sufficiently realised how largely our national galleries and museums in London and in the provinces that are now open to the public exist for the benefit of the poorer sections of the population. …Our national galleries and museums exist for those who have no chance of studying art elsewhere and who have no opportunities of widening their knowledge or experience by personal travel, study or research.Footnote 14

Consequently, the concept of the “national art treasure” was born, along with the argument that such objects should be retained by the nation for study by, and the “gratification” of, all of society but particularly the poorest members. The original definition of “national treasure” can therefore be attributed to cultural objects with the ability to inform, educate, enhance lives, and satiate the mind.

As the debate surrounding the retention of cultural objects grew in Parliament, the definition of a “national treasure” concomitantly expanded, to denote an object that, in essence, forms part of the very “civilization” of the country. Such objects are, arguably, necessary possessions of the nation and of an inalienable importance and innate cultural value:Footnote 15 “[U]nless immediate and adequate steps be taken to prevent it, the very few of these treasures of art which now remain in this country will follow those which have already gone across the sea. I do not think it is really necessary to argue, at this stage, that the possession of art treasures and the power and opportunity of appreciating them, are of real advantage to a nation. Art is part of our civilisation, as civilisation is known today, and as I think it will be known for many centuries to come.”Footnote 16

As such significant and important objects, retention and preservation have been paramount. However, the proposal to introduce formal export control processes to retain national treasures was not unanimously agreed upon. During a debate on 23 February 1926 on the prohibition of exports of cultural goods, opposition was voiced by Frank Rye, member of parliament for Loughborough, who asserted, among other things, that,

[a]lthough I recognise the loss to this country of any works of art, whether in the nature of pictures, furniture, or old buildings which are removed and sent abroad, I venture to suggest that the House should hesitate before taking a step which will interfere with the liberty of the subject and the privileges which we to-day possess. After all, we are supposed to live in a free country, and it seems to me that we shall be going rather far if we pass a Measure which will prevent anyone from dealing in any way which he or she may think fit with his or her own possessions.Footnote 17

However, the outbreak of World War II in 1939 saw the introduction of emergency legislation in the United Kingdom to regulate the export of many resources during the period of conflict. Previous concerns regarding the protection of private property rights were largely overlooked within the emergency legislation, which allowed for the restriction of the movement of cultural objects to be codified in legislation for the first time. Although it was supposed to be in place for one year only, the 1939 legislation remained in force far longer – for the next 63 years.

Given the rush to implement these controls brought about by the war, many felt they were of an ad hoc natureFootnote 18 and that they had not been sufficiently well conceived, drafted, or implemented to protect and retain items of significant national importance. As a result of such criticism, a reassessment of the controls took place in 1952. A report requested by the chancellor of the exchequer and chaired by the Right Honorable the Viscount Waverley (John Anderson), known as the Waverley Report,Footnote 19 set out a system of control to operate within the umbrella 1939 legislation. The recommendations made in this report included that the control on the export of cultural objects should be limited to objects meeting a relevant age and value threshold and that these objects would also need to meet at least one of the “Waverley criteria” – three questions that, if any one was answered positively, would lead to the designation of the item as a national treasure. The Waverley criteria are as follows:

-

1. Is the object so closely connected with our history and national life that its departure would be a misfortune?

-

2. Is the object of outstanding aesthetic importance?

-

3. Is the object of outstanding significance for the study of some particular branch of art, learning or history?

One very important mechanism of the Waverley Report, which is designed to take into account the interests of the individual owners of these objects, was that, in order to retain an object within the United Kingdom, it would be offered for a limited time for purchase from the owner by a national institution. If no such purchase was achievable, the item would be granted authorization to be exported. The recommendations of the Waverley Report still form the basis of the export control system for cultural goods today, under the Export Control Act 2002, which determines the status of objects as national treasures.Footnote 20 While a number of commentators have discussed the difficulty in defining “national treasures” in both national and international legislative materials, there is seemingly a consensus that “national treasure” is an accepted term for those cultural objects deemed significant enough for a nation to impose restrictions on their export.

The Current System for Determining National Treasures

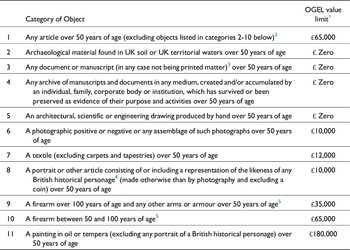

Cultural objects falling under the relevant legislative definitions require an export licence to be legally dispatched from the United Kingdom. Under section 9 of the Export Control Act 2002, the Secretary of State for the Department of Digital, Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS) is required to issue statutory guidance on the general principles of the licensing procedure relating to any controlled export.Footnote 21 The statutory guidance for the export of cultural objects from the United Kingdom reiterates the language set out in Schedule 1 of the Export of Objects of Cultural Interest (Control) Order 2003 and also sets out the guidance relating to the Open General Export License (OGEL). This OGEL allows many cultural items to be exported from the United Kingdom without the requirement of applying for an individual, physical export license. Under the OGEL limits, different categories of objects are listed as subject to the export control for cultural objects, and specific exceptions are also set out where export control does not apply (see Table 1 in Appendix 1).

While the relevant legislation and statutory guidance provide some clarification as to the types of objects that fall under the definition of “cultural object,” this term is interpreted widely and covers a very broad range of objects. In turn, this means that the type of objects that are available for designation as national treasures also varies significantly. With such an abundance of objects falling into these categories, and potentially also qualifying for the status of national treasures, it is the meaning of the object (or the meanings that can be applied to the object) that marks it out as relevant for national heritage and identity rather than the type or form of the object.Footnote 22 The definition of “national treasure” therefore falls to the fulfilment of an intangible value placed upon a certain object, not the materiality or category of cultural object that the item falls into. The value of the object is not inherent but contingent and applied. While The Spanish Armada off the Coast of England is considered a national treasure, so too is a set of flint-lock pistolsFootnote 23 and the death mask of Napoleon Bonaparte.Footnote 24 National treasures are not always paintings or sculptures.

Why, then, is the term “national treasure” limited in this discussion to the process during which items are formally presented for potential export from the United Kingdom? Why are other stages of the life of a cultural object not included? As Richard Turnor states, “[t]he expression ‘national treasure’ is unknown in British cultural property legislation, although UK law seeks to encourage the preservation of important cultural objects and discourage their removal from the United Kingdom. The principal methods have been to control exports of cultural property, to introduce tax reliefs for private owners and to encourage the formation of national collections.”Footnote 25 Of these three, the most important is export controls. For Turnor, the effect of a national treasure is the desire to retain it in the United Kingdom, but it is still not clear what the unique qualities of national treasures are and why these objects are, or should be, different (either in their composition, conservation, display, “value,” or ownership status) from other cultural objects. Despite Turnor identifying three instances in the United Kingdom in which the term “national treasure” may be defined through legislative or legislative-adjacent methods (export control, the taxation of cultural objects, and the national collections of cultural objects), there is only one instance in which a determination of an item as a national treasure is specifically referred to, and that is through the export control process.

There is a lack of clarity, therefore, that accompanies any legal position or definition dealing with these objects. Furthermore, the utilization of the term “national treasure” to denote specific cultural objects that are significant enough to restrict their export from national borders is utilized in international legislative instruments (by which the United Kingdom is bound) such as Article XX(f) of the General Agreement on Trade and Tariffs (GATT): “Subject to the requirement that such measures are not applied in a manner which would constitute a means of arbitrary or unjustifiable discrimination between countries where the same conditions prevail, or a disguised restriction on international trade, nothing in this Agreement shall be construed to prevent the adoption or enforcement by any contracting party of measures: … (f) imposed for the protection of national treasures of artistic, historic or archaeological value.”Footnote 26

This article provides an exception to the free movement of cultural objects between the nations signed up to the GATT, on the basis that a nation has designated the item a “national treasure.” In the United Kingdom, the body responsible for determining whether an object falls under the definition of “national treasure” is the RCEWA. The RCEWA assesses the objects that come before them as objects that are being exported and where such export has been objected to on the recommendation of “expert advisors,”Footnote 27 on the basis of the -Waverley criteria (discussed above). If an object that comes before the RCEWA meets one or more of these criteria, it will be determined a national treasure, and the export of that item will generally be considered undesirable.Footnote 28 The process then involves a temporary export bar being placed on the item, for a specific period, to allow institutions (and, on occasion, private individuals) to purchase the item from the owner and retain it in the United Kingdom.

The system for allowing private purchasers was introduced in 1990 and has been criticized for the perceived over-extension of the power of the state to interfere with the private rights of owners. Contemporary commentary has outlined the opposition to this change:

Mr Ridley’s announcement of a system of private offers on 2nd March 1990, directed at the application to export Canova’s “Three Graces” then at an advanced stage, is an example of the extraordinary way in which executive powers can be used to “move the goalposts” midway through an application if there are inadequate legislative safeguards … [i]t is extraordinary that the legislative basis of the system is to be found in a 52 year old statute designed to prevent trading with the enemy where procedures can be altered without warning by ministerial order.Footnote 29

While the secretary of state may utilize their discretion to accept the RCEWA’s recommendations as to whether to grant an export license or defer the export of the object for fundraising, it is the RCEWA that determines whether the object is a national treasure based upon the fulfilment of the Waverley criteria. It is the RCEWA, therefore, that holds the mandate to determine whether an object is a national treasure.Footnote 30

The monetary value placed on an item – that is, the price at which an institution or private individual can offer to purchase the item – is not always the price at which the owner of the item has either sold or valued the item. While the owner is asked to provide the item’s value on the application form for export, the RCEWA also has the objective “to recommend a valuation which is fair and reasonable to the owner and national heritage interests alike by examining carefully the elements included in the valuation.”Footnote 31 The valuation, therefore, may change once the item is assessed for national treasure status. This may somewhat fuel the secretive nature of private owners in the art world. It is also possible that owners will wait to part with items until that artist or movement falls out of fashion, making the object or objects potentially less valuable on the open market. This will mean that the item either falls below the monetary threshold for consideration by the RCEWA or that the national interest is discovered in an item when the “fever pitch” for that artist or movement is no longer at its highest. The ability for the RCEWA to alter the valuation of the item, therefore, might impact on the heritage of the nation.Footnote 32

The “National Treasure Space” or the “Birth of the National Treasure”

It is proposed that determinations of objects as national treasures are created within a particular space by a particular group of people, utilizing a particular type of discourse. Once created, these national treasures become part of the “institutionalization” of heritage in that the objects become part of the heritage management process.Footnote 33 The interest in the preservation and retention of these objects is initiated at the point at which they are created – or “born” – as national treasures. As such, the heritage management of an object is called into question at the point of designation as a result of the desire to export it. Prior to this, with certain caveats, the private possession of a cultural object does not raise enforceable cultural heritage management concerns (‘[i]n most places, you can throw darts at your Rembrandt’).Footnote 34 The creation of an object as a national treasure thus leads to the creation of new meanings, values, knowledge, understandings, and, importantly, obligations relating to that object.Footnote 35

Placement in front of the RCEWA, during which analyses of the object take place to create new meanings, results in the object emerging as a newly created national treasure. Subjects within this context take an active role in this creation, through determinations and decisions that they have the power to implement and impose. Such power is comparable to that exercised in a number of other heritage management sectors. As David Littlefield claims, in relation to the field of archaeology,

archaeologists are active participants in the ways in which meaning is attached to the past. Not only do they decide where, when and how to dig, they decide what is preserved, what is removed, where it is removed to, how it is presented and what stories the artefact tells. These decisions are all reasonable and natural, but also culturally and socially determined. Shanks argues that … archaeologists do not discover the past, but treat the remains as a resource in their own creative (re)production or representation.Footnote 36

It is not simply the creation of national treasures that takes place in this space. It is also the site of changes to the way in which an object is used or permitted to be used. The institutional space in which national treasures are created is the proposed virtual construct produced through the specific methods with which those objects are assessed and observed and the subjects they are assessed and observed by. With the utilization of these methods, aspects of the objects are changed within this space in order to fit the institutionalized understanding of them.Footnote 37 As Llorenç Prats contends, “heritage is not a naturally occurring phenomenon, nor is it universal or eternal. It is in fact a socio-cultural construction, born at a specific moment in history, and which has clear objectives that it pursues along symbolic lines that can be easily analysed.”Footnote 38 National treasures are, therefore, created like other forms of heritage. However, where other forms of heritage have traditionally been created through a consensus, or cultural institutions, national treasure creation is a formal quasi-legal designation by a government official.Footnote 39 Furthermore, the determination is made at the point of proposed export, not at any significant cultural point in the life of the object.

By drawing parallels between the processes of the disciplinary museum space and the NTS in determining the national heritage, this article proposes that the process can, and should, be scrutinized in the same manner as other cultural institutions. The method by which such determinations are made is reminiscent of Foucault’s Reference Foucault and Miskowiec1986 proposition of heterotopias – in which museums and libraries are considered institutions that “enclose in one place all times, all epochs, all forms, all tastes … the project of organizing in this way a sort of perpetual and indefinite accumulation of time in an immobile place.”Footnote 40 Foucault’s understanding of heterotopias considers them places that are “absolutely different from all the sites that they reflect and speak about.”Footnote 41 Thus, a museum space is a heterotopia due to its ability to create and curate narratives that do not exist outside of it. To access such heterotopias, Foucault contends that either “entry is compulsory, as in the case of entering a barracks or a prison, or else the individual has to submit to rites and purifications.”Footnote 42 The submission to rites and purifications for entry to a museum as a heterotopia is the very understanding that Bennett provides for the historical, disciplinary museum.

These spaces were not freely open to the public but were made available to those who were willing to abide by specific rules and regulations for entry – those able to submit to rites and purifications: “[T]hey sought to tutor their visitors on the modes of deportment required if they were to be admitted.”Footnote 43 In a similar manner, the NTS is not open to the general public; entry is gained through the fulfillment of specific criteria required of the members of the RCEWA. Members of the public are permitted to enter to object to their own objects being declared national treasures, but the decisions of the RCEWA are not taken in the presence of the owner. The public are permitted only when they have a proprietary interest in the item and yet still only for a small part of the proceedings. It is the RCEWA alone that is able to submit to such “rites and passages.” Scrutiny of this space is thus limited to the information presented by the RCEWA in their annual reports and the owners of individual items being assessed. The NTS is, therefore, a private space in which a public interest is stated to be recognized.

While the contemporary understanding of museum practices no longer positions the museum in a disciplinary manner (“[i]t is generally expected that audiences wish to be much more active and physically involved in museums today. …The museum or art gallery has in the past been very much the territory of the professional staff, with the ‘public’ allowed in on sufferance, if their behaviour was appropriate. Now … he or she has an equal position of power’),Footnote 44 the workings of the process for national treasure designation echo many of the features of such an institution as set out by Bennett and Hooper-Greenhill.

The form of disciplinary museum as presented by Bennett in The Birth of the Museum and Hooper-Greenhill in Museums and the Shaping of Knowledge acknowledges the power of the institutional space in not simply representing, but also creating and curating, a national cultural identity. The presentation of one, acceptable form of knowledge emerging from the museum as an institution is reminiscent of the method through which objects are today declared national treasures. As Hooper-Greenhill contends, “[t]he articulations of relations of advantage (acquisition policies, selection grids, display technologies), through which a single selected meaning is offered as the natural, authoritative, and complete meaning-potential of material things, constitute some of the micro-processes of power in the present-day museum, instrumental technologies with the functionality of enshrining the specialist, academic knowledge of the ‘curator’ and ‘truth.’”Footnote 45

Rather than the accepted belief that the museum is a space in which a linear historical narrative is displayed, both Bennett and Hooper-Greenhill question the methods through which the museum exists, and the impact that the museum institution has on the public. They suggest that it should be seen not simply as a benign place in which visitors are informed about the history of mankind but, rather, as a political space in which the power of the institution can be observed through the divide between private and public, between knowing and unknowing, and between informed and uninformed. Both Hooper-Greenhill and Bennett contend that the museum institution, through the accepted role of educator, imposes a dominant narrative that seeks to assert control through the co-option of national identity:

The space of representation constituted in the relations between the disciplinary knowledges deployed within the exhibitionary complex thus permitted the construction of a temporally organized order of things and peoples. … And an order which organized the implied public – the white citizenries of the body politic in constructing a “we” conceived as the realization, and therefore just beneficiaries, of the processes of evolution and identified as a unity in opposition to the primitive otherness of conquered peoples.Footnote 46

That the disciplinary museum space championed the dominance of the white Western world meant that the narrative presented was one of othering – othering of anything non-white, non-Western. How far this narrative is perpetuated in the NTS is certainly a consideration to take into account. At what point – if any – does the RCEWA consider the past of those that do not fall into this category?

The role of the contemporary museum has since shifted from the “disciplinary museum,” which “required specialised subject positions to maintain its momentum as an instrument of the state,”Footnote 47 where there was a “division … between knowing subjects, between … expert and layman,”Footnote 48 and where the aim was to create “docile bodies.” The contemporary museum may be conceived today as a space of greater open dialogue, where the distinction between the private and public spaces of the institution has disappeared. As academic Catarina Pombo Nabais claims, the “experience and involvement of the spectator is now tendentiously personalized. The cultured and demanding visitor also became an emancipated, active visitor.”Footnote 49 This was a result of the need of museums to take a more commercial approach to their structure in order to attract new and varied audiences.

The requirement, therefore, for equal subject positions in the modern museum has seen it evolve from the model of the disciplinary museum. However, this article argues that, in contrast to these trends, an uneven balance of power and the dichotomy between the knowing and unknowing subject remain within the NTS, and the observable power dynamics echo those of the defunct disciplinary museum model. Consequently, the analyses of the museum space as carried out by Bennet and Hooper-Greenhill can be productively applied to the process of determining an object as a national treasure. This is not only because the museum space is the favored location for objects declared national treasures but also due to its function as not just a regulated institution but also a regulating institution, determining the type of cultural output that is necessary to represent a community. This is akin to the work of the NTS as a regulating institution that prescribes the cultural representation of the community through the attribution of national treasure status. Just as it was the “private space” of the museum that historically determined the production of meaning to be consumed by the spectator in the “public space,” it is the RCEWA, as informed by the “expert adviser” in the “private space” of the NTS, that determines the national treasures to be consumed by the public. These “private spaces” are unregulated, and power is unfettered by answerability; the NTS is despotic, not democratic. Indeed, the RCEWA’s failing to take into account certain aspects that are considered to fall outside of its remit – for example, potential problematic provenance of objects – can lead to the creation of national treasures that members of the public do not agree with.Footnote 50

Subject and Object Positions within the NTS

Subject positions within institutionalized spaces are significant for both Hooper-Greenhill’s and Bennett’s analyses. Both make the claim that the changing of the museum space from a private place of collecting to a public space of spectacleFootnote 51 resulted in the changing of the subject positions facilitating the dominant narrative of the museum as the arbiter of national identity: “This was not, however, merely a matter of the state claiming ownership of cultural property on behalf of the public or the museum opening its doors. It was an effect of the new organizational principles governing the arrangement of objects within museum displays and of the subject position these produced for that new public of free and formal equals which museums constituted and addressed.”Footnote 52

The subject positions in the NTS follow a similar path. The owner of the object, entering the space as the object’s controller, has this subject position altered. They are no longer considered any form of authority in relation to that object.Footnote 53 Rather, the jurisdiction – and, therefore, the power – transfers to the RCEWA, which is provided with information relating to the object’s potential fulfilment of the Waverley criteria by an individual referred to in this space as the “expert advisor.” The discourse present in this space reflects the subject positions and the distribution of power relating to the object. Throughout the assessment, the party wishing to export the object is merely the “applicant,” and the RCEWA is “advised” throughout by an “expert” – the party who has objected to the proposed export. Within the proposed NTS, therefore, a great divide forms between those with knowledge (and power) and those considered to be without it. The proprietorial rights that the owner enjoyed are modified within the NTS. The owner loses the power and knowledge with which they entered the NTS. For Laurajane Smith, these “experts” resultantly occupy a position not only as consumers of the past but also as determiners of the significance of that past and what is worthy of retention and representation: “[E]xpert values and knowledge … set the agenda or provide the epistemological frameworks that define debates about the meaning and nature of the past. … This position of privilege ensures that they are treated not as just another stakeholder group, but act as stewards for, and arbitrators of, debates over the past.”Footnote 54

The NTS, it can be posited, is a constructed space in which the dialogue regarding the status of heritage objects is rooted in the model of the disciplinary museum. The divide between the public and private frames the NTS as an institution in which the interaction of those within will depend largely on the perceived “expertise” held by those within. The subject positions, therefore, echo those found within the disciplinary museum model (as articulated by Hooper-Greenhill and Bennett). As Emma Waterton and Laurajane Smith emphasize,

[w]hat is at issue is that some people are included within those groups entitled to make decisions about what is (or is not) heritage, while others are excluded. Not only are many people overlooked as authorities capable of adjudicating their own sense of heritage, so too is their lack of access to necessary resources. They are, in effect, subordinated and impeded because they do not hold the title “heritage expert,” as well as lacking the resources assumed necessary to participate in heritage projects (Western schooling, economic means, etc.), and also potentially “lacking” a particular vision or understanding of heritage and the accepted values that underpin this vision (universality, national and aesthetic values, etc.).Footnote 55

Even cursory research suggests that the membership of the RCEWA, since its inception, has been – and continues to be – lacking in diversity. It would appear that approximately 84.4 percent of the overall membership of the RCEWA has been male, with a person of color yet to sit on the committee. A majority of those admitted to the RCEWA as members seem to have been university educated, and many have attended prestigious and well-known private schools. Such a lack of diversity appears consistent with museums and the wider art sector, with “the proportion of Major Partner Museum (MPM) staff from diverse backgrounds [remaining] largely static,”Footnote 56 and Nicholas Serota, chair of Arts Council England states that “Arts Council and the organisations we invest in are still not representative of this country as a whole. The long-standing issue of under-representation … has to be recognised and addressed.”Footnote 57

Those capable, therefore, of becoming such a “heritage expert” appear to be few. The lack of diverse membership of the RCEWA should necessarily raise concern regarding the story of the nation that is being told through these objects – indeed, concern for the very construction of national identity in the United Kingdom. Furthermore, object positions in this space are capable of shifting. On entry to this space, the item is assessed in terms of it fulfilling the requirements of a “national treasure.” Returning to the example of The Spanish Armada off the Coast of England, it is possible to identify the specific aspects of the object that were considered in changing the item from a cultural object to a national treasure. Upon exiting, therefore, the object may no longer be regarded as just a cultural object. In particular, when in this space, the following determinations were made of the item that related specifically to the object as a national treasure: “The Committee considered the miniature to be a patriotic painting, evoking Elizabeth I as a defender of the Protestant faith through symbols of both the Church and the State. … The recent acquisition of one of the three extant versions of the Armada Portrait by the National Maritime Museum, was an example of the public dialogue that can be sparked by the comparison of such paintings.”Footnote 58

The consideration of this object as patriotic and capable of being compared with other works held in the United Kingdom highlights the national importance of the item, not simply as a cultural object. The committee’s decision ignored the applicant’s submissions that it is the event of the Spanish Armada, not the item itself, that is important nationally and that other examples of similar works dealing with this event exist, rendering the information to be obtained from this work limited in both its novelty and ability to provide further detail relating to the event. Thus, while the object would naturally have been considered for its cultural significance prior to entering the NTS, the emphasis placed on the importance of the item nationally, and the argument that its departure would therefore be a misfortune for the United Kingdom, relate specifically to the determination made within this space. Both object and subject positions are clearly open to change within this process.

Perpetuating Imperialism

This inability to contextualize in any real manner – other than to reinforce imperialistic views of the history of the United Kingdom – means that the RCEWA is not fully considering the contemporary relevance of the cultural objects it is assessing. By failing to consider these objects in a light that takes account of the current political and cultural climate, there is a real danger that objects will be retained on the basis of an understanding of the United Kingdom that is outdated, much like the disciplinary museum model. The imperial version of culture in the United Kingdom is changing. What the public are willing to accept as culturally significant – and worthy of cultural consideration and heritage management – is in flux. A key example of this is the contesting or contextualizing Colston debate. A notable event in the cultural and political landscape, the context(s) in which historical subjects are now understood in the United Kingdom was shifted significantly following this case. On 7 June 2020, a bronze statue of Edward Colston (1636–1721) was toppled by Black Lives Matter protestors in Bristol. Colston was a British merchant whose statue commemorated his philanthropic efforts during his lifetime, he endowed various schools, hospitals, and churches in and around Bristol. However, Colston’s history as a slave trader became more widely understood from the 1990s, and, prior to the toppling of the statue, calls for its removal or recontextualization had been gaining popularity.

Following the death of George Floyd in May 2020, the statue became a significant representation of racism, oppression, and the violence against black people. The Black Lives Matter protest in Bristol in the wake of Floyd’s death therefore became the context in which the statue was ultimately toppled, painted on, and thrown into Bristol harbor. It remained there for four days and is now housed in a museum storage facility in Bristol. The future of the statue is still undecided. Such events, however, do not appear to find their way into the remit of the NTS. While some discussion of certain aspects of current cultural discourse may be present in the annual reports, the individual case analyses during which the RCEWA makes its determinations as to national treasure status do not mention current cultural or political debates, nor do they permit the RCEWA to take these into account in their recommendations.

The work of the RCEWA in its creation of objects as national treasures provides a significant context in which national heritage is determined. The consequences of such a designation can have a real-world impact on the ability to understand and deal with those objects and the proprietary rights of the objects owner(s). Articulating more fully how this process operates is therefore an urgent task, with a view to better incorporating a more culturally relevant context within the NTS.

Conclusions, Recommendations, and Further Research

This article has considered the process by which cultural items in the United Kingdom become “national treasures.” Through an examination of the introduction of restrictions on exporting cultural items due to the perceived “art exodus” in the early twentieth century, it is proposed that what has evolved and developed is a process by which heritage objects are created as national treasures within an institutional space. By examining Bennett’s Birth of the Museum and Hooper-Greenhill’s Museums and the Shaping of Knowledge, the institutional space of the museum has informed a reexamination of the place in which national treasures are made. Drawing parallels between the disciplinary museum space and the NTS, it is submitted that the processes that take place within this space should be open to scrutiny in a similar manner to those in other cultural institutional spaces, which is not the case at present.

The lack of diversity present in the NTS can only serve to reinforce the authorized heritage discourse (AHD), which Laurajane Smith defines as follows:

The AHD defines heritage as aesthetically pleasing material objects, sites, places and/or landscapes that are non-renewable. Their fragility requires that current generations must care for, protect, and venerate these things so that they may be inherited by the future. The AHD assumes that heritage is something that is “found,” that its innate value – its essence – is something that will “speak to” present and future generations and ensure their understanding of their “place” in the world. The inheritance offered by cultural patrimony is the creation of a common and shared sense of human identity.Footnote 59

The future diversification of the RCEWA would serve to provide greater representation of – and alignment with – the current cultural climate of the United Kingdom. This does not necessarily make the concept of a reviewing committee wrong. It does mean, however, that, at the very least, it requires some form of improvement in regard to diversity and representation. There are other cultural committees that demonstrate the provision of effective heritage management in a diverse way. Consider the membership of the Commission for Diversity in the Public Realm. The aim of this commission was to “develop a more joined-up approach and create a shared understanding of the importance of different achievements and stories in the city’s public spaces” by diversifying the statutes, plaques, and street names of London.Footnote 60

The members of this commission represent people from many different vocations, and the membership is diverse in its representation of race, education, and experience. It is concerning, and a clear indication of the advancement of the AHD, when such a lack of diversity is present on the committee that is responsible for determining national treasures. A push to diversify the RCEWA can only benefit the decision-making process and ensure that the “nation” is truly represented by those objects that are ultimately retained. The RCEWA’s decisions and determinations would also be more representative and relevant if cultural contexts were more fully consideredFootnote 61 and utilized in the rationalization of the recommendations made within the NTS. By considering a wider and more inclusive understanding of history and heritage, the objects deemed “national treasures” by the RCEWA could speak much more to the whole nation. To further investigate the proposed NTS, research in the field may consider the wider implications of the determination of an object as national treasure – how this influences the future composition of the object in question and the ramifications of this designation for the relationship between the object and individuals and communities.

When considering the disciplinary museum space, the objects under consideration are already in the public realm; thus, the degree of control that the public have over those objects is established. However, in the NTS, the objects being considered are in a transitional stage – between private and public object – and, therefore, it is important to understand the shifts and changes that take place in this phase. By examining the processes within this space and the implications of them, a rigorous critique of those processes that occur within this space (and their implications) can begin. It is only by fully understanding the institutional power within this space that determinations can be made as to their proportionality and suitability. As Hooper-Greenhill’s analysis of the disciplinary museum suggests, the “act of knowing is shaped through a mix of experience, activity, and pleasure, in an environment where both the ‘learning’ subject and the ‘teaching’ subject have equal powers.”Footnote 62 The gap between the authoritarian decision making within, and the visitors from outside of, museums is, Hooper-Greenhill contends, closing. As a result of this article’s analysis of the existing procedures that determine objects as national treasures, I contend that a similar problematic gap continues to exist within the NTS, which demands future clarification in the DCMS’s statutory guidance for the export of cultural goods in the United Kingdom and the Arts Council England’s notice for exporters.Footnote 63

Appendix 1

Table 1. OGEL value limits for the export of cultural goods

Note: Courtesy Arts Council England UK, Export Licensing for Cultural Goods: Procedures and Guidance for Exporters of Works of Art and Other Cultural Goods, Issue 1, 2021.