1 Introduction

The ultimatum game is commonly used to examine economic decision making (Reference Güth and KocherGüth & Kocher, 2013). In the ultimatum game, a proposer is given a sum of money to divide between him- or herself and a responder. The responder then has the option to accept or reject the allocation. If the responder accepts, both players receive the amount that has been allocated to them; if the responder rejects, both players get nothing. Most proposers split the money relatively evenly and most responders accept these fair offers (e.g., Camerer, 2003). The goal of the present study was to examine predictors of responders’ decisions when they have received an unfair offer.

Unfair offers occur when proposers have divided the money so that they receive more than responders. For example, if a proposer is given $10 to allocate, the proposer may divide it so that he or she receives $8 and the responder receives $2. Game theory suggests that responders, acting in their own self-interest, will accept this offer (or any offer greater than $0) in a single round of the ultimatum game. Studies have consistently demonstrated, however, that unfair offers are often rejected (e.g., Reference Cooper and DutcherCooper & Dutcher, 2011). The rejection of unfair offers may be viewed as irrational because the responder is choosing $0 rather than some value greater than $0.Footnote 1 This behavior is an example of negative reciprocity because the responder is punishing the proposer for being unfair (e.g., Halali, Bereby-Meyer & Meiran, 2014). Negative reciprocity has been studied in a variety of economic situations (e.g., Brandts & Solà, 2001).

Dual process theories of cognition have been employed to explain ultimatum decisions (e.g., Reference Sanfey and ChangSanfey & Chang, 2008). These theories claim that humans have two separate modes of information processing. Although the specifics of the two systems vary among theories (see Evans, 2008, for review), one system (System 1) is regarded as processing information in fast, automatic, heuristic-based ways, whereas the other system (System 2) is slower, more deliberate, and analytic. Furthermore, System 1 processes are believed to operate independently of general intelligence and working memory capacity, whereas System 2 processes are linked to individual differences in general intelligence and working memory capacity (Reference EvansEvans, 2008). One System 1 process, individuals’ affective responses to alternatives, has been shown to influence decisions in a variety of situations (e.g., Slovic, Finucane, Peters & MacGregor, 2002). When applied to unfair ultimatum offers, responders’ negative affective responses to an unfair offer leads them to want to reject the offer, whereas their understanding that accepting any offer greater than zero is beneficial leads them to want to accept the offer (Reference Sanfey and ChangSanfey & Chang, 2008). The explanation that System 1 processes lead to the rejection of unfair offers, whereas analytical System 2 processes lead to the acceptance of these offers has been termed the automatic negative reciprocity hypothesis (Reference Halali, Bereby-Meyer and MeiranHalali et al., 2014). In support of this hypothesis, emotions such as anger have been found to be crucial in rejecting unfair offers (Reference Pillutla and MurnighanPillutla & Murnighan, 1996; Reference Srivastava, Espinoza and FedorikhinSrivastava, Espinoza & Fedorikhin, 2009).Footnote 2, Footnote 3

To establish that accepting an unfair offer is related to System 2 processes, several experimental studies have demonstrated that reducing System 2 processing increases the rejection of unfair ultimatum offers. When responders must make their decisions under time pressure they are more likely to reject unfair offers than when there is no deadline (Reference Cappelletti, Güth and PlonerCappelletti, Güth & Ploner, 2011). Similarly, unfair offers are more likely to be accepted after a 10-minute delay than when a decision is made immediately (Reference Grimm and MengelGrimm & Mengel, 2011). Also consistent with the automatic negative reciprocity hypothesis, when individuals are deprived of sleep (Reference Anderson and DickinsonAnderson & Dickinson, 2010), when their executive resources are diminished with an ego depletion manipulation (Reference Halali, Bereby-Meyer and MeiranHalali et al., 2014), and when they are alcohol intoxicated (Reference Morewedge, Krishnamurti and ArielyMorewedge, Krishnamurti & Ariely, 2014), they show increased rejection rates compared to control conditions. Furthermore, individuals who accept the most unfair offers show greater cognitive control than those who accept the fewest unfair offers (Reference DeDe Neys, Novitskiy, Geeraerts, Ramautar & Wagemans, 2011).

Despite the abundance of support for the automatic negative reciprocity hypothesis, some findings are more equivocal. Cognitive abilities (intelligence, attention, working memory, and executive functioning), which are linked to System 2 processes, do not significantly differ among participants who accept and those who reject unfair offers (Reference Nguyen, Koenigs, Yamada, Teo and CavanaughNguyen et al., 2011). Others have claimed that System 2 processes, rather than System 1 processes, lead to rejecting unfair offers, an approach termed the deliberate negative reciprocity hypothesis by Halali et al. (2014). Correlational studies have shown that individuals with greater heart-rate variability, a marker for inhibitory control and emotion regulation, are more likely to reject unfair offers (Reference Sütterlin, Herbert, Schmitt, Kübler and VögeleSütterlin, Herbert, Schmitt, Kübler & Vögele, 2011; but see Reference Dunn, Evans, Makarova, White and ClarkDunn, Evans, Makarova, White & Clark, 2012). Furthermore, individuals’ rejection of unfair offers is correlated with performance on a motor response inhibition task: those with greater System 2 abilities rejected more offers (Reference Sütterlin, Herbert, Schmitt, Kübler and VögeleSütterlin et al., 2011). Rejection of unfair offers is positively related to reaction time to make a decision and to participants’ self-rated need for cognition (Reference Mussel, Göritz and HewigMussel, Göritz & Hewig, 2013a). Finally, using transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS), Knoch, Pascual-Leone, Meyer, Treyer, and Fehr (2006) found that disrupting the right dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, an area believed to be involved in executive processes necessary for inhibiting selfish impulses to accept unfair offers, increases the acceptance of unfair offers. Thus, there is some correlational and TMS evidence that System 2 processes lead to the rejection of unfair offers.Footnote 4

Examining differences in the ability to engage in System 2 processing among those who accept and those who reject unfair offers tests contradictory predictions derived from the automatic negative reciprocity hypothesis and from the deliberate negative reciprocity hypothesis. There are several ways to assess System 2 processes, including measures of working memory capacity and general intelligence, and performance on these measures has been associated with performance on a variety of reasoning and judgment and decision tasks that require System 2 processes (see Evans, 2003, for review). The Cognitive Reflection Test (CRT; Reference FrederickFrederick, 2005) was created to assess the ability to overcome intuitive but incorrect responses arising from System 1 processes in favor of more effortful correct responses arising from System 2 processes. Indeed, performance on the Frederick’s (2005) three-item CRT is predictive of resisting several cognitive biases (Reference Campitelli and LabollitaCampitelli & Labollita, 2010; Reference Cokely and KelleyCokely & Kelley, 2009; Reference FrederickFrederick, 2005; Reference Oechssler, Roider and SchmitzOechssler, Roider & Schmitz, 2009; Reference Toplak, West and StanovichToplak, West & Stanovich, 2011), and an expanded seven-item CRT has been developed that is a better predictor than the original three-item version for several rational thinking tasks (Reference Toplak, West and StanovichToplak, West & Stanovich, 2014). Regarding ultimatum decisions, if participants who accept unfair offers outperform those who reject them on the CRT, this finding would support the automatic negative reciprocity hypothesis. Alternatively, finding that participants who reject unfair offers outperform those who accept them would support the deliberate negative reciprocity hypothesis.

Only one study, to our knowledge, has examined the relationship between performance on the CRT and ultimatum decisions. De Neys et al. (2011) found that performance on the three-item CRT was positively correlated with acceptance of unfair ultimatum offers. Given the mixed support for the automatic- and the deliberate negative reciprocity hypotheses, the present study sought to replicate this relationship between cognitive reflection and acceptance of unfair ultimatum offers.

2 Study 1

In Study 1, participants responded to an unfair ultimatum game offer, completed the seven-item Cognitive Reflection Test (CRT7; Reference Toplak, West and StanovichToplak et al., 2014), and completed a self-reported measure of rational and experiential thinking styles: the 40-item Rational-Experiential Inventory (REI-40; Reference Pacini and EpsteinPacini & Epstein, 1999). The REI-40 assesses individuals’ self-reported tendencies to engage in automatic, intuitive thinking (experiential thought, which is analogous to System 1 processing) and effortful, analytic thinking (rational thought, which is analogous to System 2 processing). The automatic negative reciprocity hypothesis leads to the predictions that accepting the unfair ultimatum offer would be positively correlated with performance on the CRT7 and the rational thought scales of the REI-40 and negatively correlated with the experiential scales of the REI-40. The deliberate negative reciprocity hypothesis, conversely, leads to the predictions that accepting the unfair offer would be negatively correlated with performance on the CRT7 and the rational thought scales of the REI-40 and positively correlated with the experiential scales of the REI-40.

2.1 Method

2.1.1 Participants

Undergraduate students ( N = 184) enrolled in lower division psychology courses at California State University San Marcos participated in exchange for credit toward the completion of a research requirement. The sample contained 165 (89.7%) women and 19 (10.3%) men, and participants ranged in age from 18 to 27 ( M = 19.93, SD = 1.69) years (21 participants did not provide their age). The racial/ethnic composition of the sample was 77 (41.8%) Hispanic individuals, 57 (31.0%) Caucasian individuals, 24 (13.0%) Asian/Pacific Islander individuals, 5 (2.7%) Black/African American individuals, 1 (0.5%) Native American individual, 14 (7.6%) other/multi-ethnic individuals, and 6 (3.3%) participants declined to provide their ethnicity. An a priori power analyses based on a small to medium point-biserial correlation between ultimatum decisions and continuous predictors ( r = .20), with α = .05 (two-tailed), determined that this sample would be sufficient to detect these relationships with power greater than .75.

2.1.2 Materials and procedure

Participants completed a one-shot ultimatum game decision, a measure of cognitive reflection, and a self-reported measure of rational and experiential abilities and engagement.

Participants first received instructions on the ultimatum game. After reading a description of the game, they were told that they would be randomly assigned to either the role of proposer or responder to play with another participant from the same subject pool who was randomly assigned to the other role. All participants were then informed that they had been assigned to the role of responder, and that another participant assigned to the role of proposer, labeled only as “Participant #1057,” had made an $8/$2 offer. Because proposers’ characteristics such as gender and attractiveness (e.g., Reference Solnick and SchweitzerSolnick & Schweitzer, 1999), ethnicity (Reference Kubota, Li, Bar-David, Banaji and PhelpsKubota, Li, Bar-David, Banaji & Phelps, 2013), and facial expression (Reference Mussel, Göritz and HewigMussel, Göritz & Hewig, 2013b) can influence responders’ behavior, participants were not presented with photos of the proposer. After participants saw the offer, they selected one of two options: “I accept this offer (Participant #1057 gets $8 and I get $2)” or “I reject this offer (Participant #1057 and I get $0).” To ensure that participants took the decision seriously, they were informed that a subset of participants, chosen at random, would be paid according to the decisions they made.

After completing the ultimatum decision, participants provided answers to the 7-item Cognitive Reflection Test (CRT7; Toplak et al., 2014—the first 7 “problems” in the supplement at http://journal.sjdm.org/14/14715/stimuli.pdf). The CRT7 contains the original three items from Frederick’s (2005) test and four additional items. All items have an intuitive response that is incorrect and a rational, correct response. For example, the first item is, “A bat and a ball cost $1.10 in total. The bat costs a dollar more than the ball. How much does the ball cost? ____ cents.” The intuitive, incorrect response is 10 cents and the more effortful, correct response is 5 cents.

Table 1: Descriptive statistics and correlations of CRT7 scores and REI-40 scales with ultimatum decision (0 = reject, 1 = accept).

* p < .05,

** p < .01,

*** p < .001.

Participants then completed a 40-item Rational-Experiential Inventory (REI-40; Reference Pacini and EpsteinPacini & Epstein, 1999).Footnote 5 The REI-40 contains four scales: rational ability, rational engagement, experiential ability, and experiential engagement. The rationality scales contain items that assess analytic processing styles, similar to what is assessed in need for cognition measures, whereas the experiential scales contain items that assess intuitive processing styles. Participants rated their agreement with 40 statements on a scale of 1 ( definitely not true) to 5 ( definitely true). An example of a rational ability item is, “I have a logical mind,” an example of a rational engagement item is, “I prefer complex problems to simple problems,” an example of an experiential ability item is, “I believe in trusting my hunches,” and an example of an experiential engagement item is, “I like to rely on my intuitive impressions.”

All of the tasks were completed online. The first screen contained the elements of informed consent and the last screen contained debriefing information. Most participants took about 15 min to complete the study.

2.2 Results and discussion

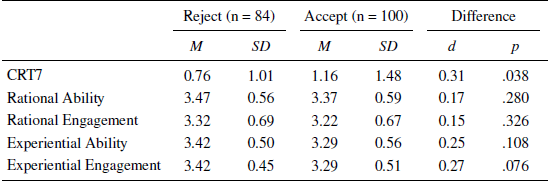

Of the 184 participants, 100 (54.3%) of them accepted the unfair offer and 84 (45.7%) rejected it. The CRT7 had questionable internal consistency (α = .60); the internal consistencies of the REI scales were generally acceptable (rational ability: α = .75, rational engagement: α = .83, experiential ability: α = .75, experiential engagement: α = .67). We compared CRT7 performance and the four scales of the REI-40 between those who accepted and those who rejected the unfair ultimatum offer. Means and standard deviations of the CRT7 and REI-40 scales for the overall sample, and their Pearson product moment correlations with each other and point-biserial correlations with ultimatum decisions are presented in Table 1. Means and standard deviations of the CRT7 and REI-40 scales separated by ultimatum game decisions are presented in Table 2. Participants who accepted the unfair offer performed significantly better on the CRT7 than those who rejected the offer, t(182) = 2.09, p = .038, d = 0.31, and those who accepted had non-significantly lower experiential engagement scores than those who rejected, t(182) = 1.79, p = .076, d = 0.27. No other comparisons approached significance.

Table 2: CRT7 scores and REI-40 scales based on whether participants accepted or rejected the unfair ultimatum offer.

The results of Study 1 with the CRT7 suggest that rejecting an unfair offer is related to intuitive (System 1) thinking, whereas accepting it is related to rational (System 2) thought. These findings are consistent with the automatic negative reciprocity hypothesis, which suggests that the negative emotions associated with an unfair ultimatum offer occur automatically and the acceptance of an unfair offer requires controlled executive processes to inhibit the automatic desire to reject the offer (Reference Halali, Bereby-Meyer and MeiranHalali et al., 2014). Participants’ scores on the four scales of the REI-40 were not significant predictors of their ultimatum game decisions. All four scales (rational ability, rational engagement, experiential ability, and experiential engagement) showed small, nonsignificant, negative correlations with accepting unfair ultimatum offers. Taken together, the results of Study 1 suggest that performance measures of cognitive abilities may be better predictors of ultimatum decisions than self-report measures of thinking dispositions.

3 Study 2

Study 2 contained several improvements based on limitations of Study 1. One limitation of Study 1 was the insensitivity of the ultimatum measure: participants responded to a single unfair offer. In Study 2, participants responded to 20 offers that varied in their level of fairness. Another limitation in Study 1 was that the internal consistency of the CRT7 was low. A recent paper has demonstrated that an expanded version of the CRT shows greater internal consistency than the original three-item version (Reference Baron, Scott, Fincher and MetzBaron, Scott, Fincher & Metz, 2015). Study 2 included items from this expanded measure, along with the original three items from Frederick (2005) and the four items added by Toplak et al. (2014) in hopes of creating a more reliable measure of cognitive reflection. Based on the findings from Study 1, we hypothesized that the cognitive reflection scores would be positively correlated with the acceptance rates of unfair ultimatum offers, but unrelated to the acceptance of fair offers.

3.1 Method

3.1.1 Participants

Undergraduate students ( N = 306) from the same participant pool as Study 1 (none of whom participated in Study 1) participated in Study 2 in exchange for credit toward the completion of a research requirement. The sample contained 251 (82.0%) women and 55 (18.0%) men, and participants ranged in age from 18 to 43 ( M = 20.19, SD = 3.24) years (98 participants did not provide their age). The racial/ethnic composition of the sample was 124 (40.5%) Hispanic individuals, 108 (35.3%) Caucasian individuals, 31 (10.1%) Asian/Pacific Islander individuals, 11 (3.6%) Black/African American individuals, 2 (0.7%) Native American individuals, 28 (9.1%) other/multi-ethnic individuals, and 2 (0.7%) participants declined to provide their ethnicity. An a priori power analyses based on the effect reported in Study 1 ( r = .15), with α = .05 (two-tailed), determined that this sample would be sufficient to detect this relationships with power of .75.

3.1.2 Materials and procedure

Participants completed 20 ultimatum game decisions and an expanded measure of cognitive reflection (all shown in http://journal.sjdm.org/14/14715/stimuli.pdf. After reading instructions of the ultimatum game, all participants were informed that they were randomly assigned to the role of responder and that they would see 20 offers made from 20 previous participants who had been assigned to the role of proposer. Participants saw four offers of five different values: $5, $4, $3, $2, and $1 of a $10 pot. The same random order of these 20 offers was used for all participants. Each offer was presented with a unique participant number for the proposer; no images or names were provided. After the presentation of each offer, participants indicated whether they accepted or rejected that offer. To increase participants’ willingness to consider each decision, they were informed that a randomly selected subset of participant would be paid according to their decisions.

After completing the ultimatum decisions, participants provided answers to a 17-item Cognitive Reflection Test (henceforth, CRT17). The CRT17 contained the original three items from Frederick’s (2005), four items from Toplak et al. (2014) and 10 additional items from Baron et al. (2015).Footnote 6

All of the tasks were completed online with most participants taking about 20 min to complete the study.

3.2 Results and discussion

Consistent with prior ultimatum game studies, acceptance rates were dependent on the offer size, F(4, 1220) = 460.60, p < .001, η 2 p = .60. All pairwise comparisons (with Bonferroni corrections) were significant. The $5 offers had the highest acceptance rate ( M = .96, SD = .13), followed by $4 offers ( M = .79, SD = .36), $3 offers ( M = .45, SD = .42), $2 offers ( M = .27, SD = .40), and $1 offers ( M = .20, SD = .38). The internal consistency for the set of ultimatum decisions was high (α = .92). The internal consistency for the CRT17 was acceptable (α = .81) and showed an improvement over that of the three-item version (α = .63) and the seven-item version (α = .71) in the present study. Participants averaged 4.19 ( SD = 3.52) correct answers on the CRT17.

Figure 1: The acceptance rates of offers across offer values based on CRT17 performance.

As predicted, performance on the CRT17 was significantly positively correlated with the overall acceptance rates of offers, r(304) = .14, p = .013. To examine whether the relationship between CRT17 and the acceptance rates of offers was dependent on the offer value, we calculated the sensitivity to offer fairness for each participant, the slope of the relation between offer size and acceptance: sensitivity = 2 x acceptance-rate-for-$5-offers + acceptance-rate-of-$4-offers − acceptance-rate-of-$2-offers − 2 x acceptance-rate-of-$1-offers. The correlation between sensitivity and CRT17 performance was not significant ( r(304) = .08, p = .164), suggesting that the relationship between CRT17 and acceptance rates was not dependent on the offer value. We illustrate this relationship in Figure 1 by creating three groups of participants based on CRT17 performance. Those classified as low ( n = 117) correctly answered 2 or fewer CRT17 questions, those classified in the middle group ( n = 93) correctly answered 3 or 4 CRT17 items, and those in the high group ( n = 96) correctly answered at least 5 CRT17 questions. Figure 1 shows the similarity in the slope of offer acceptance across offer values for these three groups. Participants who performed well on the CRT17 tended to accept all offer types more frequently than participants who performed poorly on the CRT17.

Study 2 employed a more sensitive ultimatum game measure and an extended, more reliable, cognitive reflection measure, and demonstrated that cognitive reflection was again positively related to accepting ultimatum offers. We discuss these results further in the General Discussion.

4 General discussion

In two studies, cognitive reflection predicted the acceptance of unfair ultimatum offers: those who performed well on the CRT measures were more likely to accept unfair offers. The CRT measures were designed to assess participants’ ability to override intuitive responses in favor of more rational thought (Reference Baron, Scott, Fincher and MetzBaron et al., 2015; Reference FrederickFrederick, 2005; Reference Toplak, West and StanovichToplak et al., 2014). These findings replicate and extend those of De Neys et al. (2011) and are consistent with the automatic negative reciprocity hypothesis, which claims the intuitive response to an unfair ultimatum offer is to want to reject it, whereas the more rational, deliberate response is to accept these offers. Participants’ ability to inhibit incorrect intuitive responses in the CRT measures predicted the acceptance of offers. Thus, the findings of the present study add to other studies that can be interpreted as supporting the automatic negative reciprocity hypothesis (Reference Anderson and DickinsonAnderson & Dickinson, 2010; Reference Cappelletti, Güth and PlonerCappelletti et al., 2011; Crockett et al. 2010; Reference Grimm and MengelGrimm & Mengel, 2011; Reference Halali, Bereby-Meyer and MeiranHalali et al., 2014; Reference Morewedge, Krishnamurti and ArielyMorewedge et al., 2014).

The results of Study 2, however, suggest that the relationship between CRT performance and accepting offers was not dependent on offer size. If unfair offers elicit an automatic desire to punish the proposer, then the relationship between CRT and accepting offers should be greater for unfair offers than fair offers, and this relationship might become increasingly large as the fairness of the offer decreases. This was not the case in Study 2. Those who performed well on the CRT tended to accept all offer values more than those who performed poorly. Perhaps individuals high in cognitive reflection better understand the ultimatum game and accept all offers more frequently than individuals low in cognitive reflection. Similarly, those who reject unfair offers may not do it because they are unable to inhibit an affective response to the offers. They may simply lack understanding of the task.

The observed relationship between cognitive performance and ultimatum decisions appear to contradict the findings of a previous study. Nguyen et al. (2011) found no differences in cognitive abilities (intelligence, working memory, psychomotor speed, language, visuospatial ability, and executive functioning) between participants who accepted and those who rejected unfair offers. We speculate that these seemingly discrepant results occur because cognitive reflection is different from other cognitive performance measures. Studies have demonstrated that performance on the CRT explains variance in decision making tasks beyond that which is explained by cognitive abilities and thinking dispositions (Toplak et al., 2011, 2014), and the CRT is a stronger predictor of decisions than other cognitive abilities or thinking disposition measures (Reference FrederickFrederick, 2005). This may explain why the CRT7 was a significant predictor of ultimatum decisions in the present study, but other cognitive performance measures were not in a previous study (Reference Nguyen, Koenigs, Yamada, Teo and CavanaughNguyen et al., 2011).

Despite the consistent relationship between cognitive reflection and acceptance of unfair ultimatum offers in the present study, cognitive reflection explained only a small portion of variance in ultimatum decisions (around 2% in Study 1 and Study 2). Thus, there is a large amount of variance in ultimatum decisions that result from something other than cognitive reflection. Future research could examine other sources of variance. Studies have shown that positive and negative affect (Reference Dunn, Makaraova, Evans and ClarkDunn, Makaraova, Evans & Clark, 2010; Reference Nguyen, Koenigs, Yamada, Teo and CavanaughNguyen et al., 2011), personality factors (Reference Brandstätter and KonigsteinBrandstätter & Konigstein, 2001; Reference Nguyen, Koenigs, Yamada, Teo and CavanaughNguyen et al., 2011), and justice sensitivity (Reference Fetchenhauer and HuangFetchenhauer & Huang, 2004; Reference Hoffman and BaumertHoffman & Baumert, 2010) are related to ultimatum responses. A study that includes all of these predictors would allow for a more complete understanding of the sources of different responses to unfair ultimatum offers.

One limitation of the present study was the sample. The sample was fairly ethnically/racially diverse, but the gender and age composition were not: over 80% of the participants were women in both studies and all participants were 43 years of age or younger. Because gender (Reference Hack and LammersHack & Lammers, 2009) and age (Reference Bailey, Ruffman and RendellBailey, Ruffman & Rendell, 2012) can affect ultimatum decisions, the findings of the present study should be examined in more gender-equal and age-diverse samples. Additionally, only a subset of the participants in the present study were paid based on their decisions. Thus, participants may have viewed the offers as hypothetical or of small stakes because the expected value of their decisions was reduced based on the small probability of being selected for payment. Hypothetical offers are rejected more frequently than real money offers, and small stakes offers are rejected more frequently than larger stakes offers (Reference CameronCameron, 1999). Furthermore, holding cash in their hands reduces participants’ rejections of unfair offers (Reference Shen and TakahashiShen & Takahashi, 2013). The findings of the present study should be extended to real money offers, particularly when responders handle cash.

The results of the present study are seemingly at odds with findings using other tasks. For example, some studies have shown that cooperation is automatic and self-interested defection requires deliberation. Reference Cone and RandCone and Rand (2014), for example, found that time pressure increases cooperation in competitive games. Similarly, Kieslich and Hilbig (2014) found that defecting in a social dilemma led to more cognitive conflict than cooperating. They measured cognitive conflict by analyzing the computer mouse’s trajectory; this trajectory was more curved when defecting than cooperating. Whereas the present study’s results suggest that negative reciprocity (i.e., punishing unfair partners) is automatic and responding in self-interested ways is deliberate, these studies using other tasks showed that cooperation may be automatic. Responding to unfair ultimatum offers, however, may be considerably different than the behavior examined in other tasks. Yamagishi et al. (2012) found that rejecting unfair ultimatum game offers was not related to behavior in the prisoner’s dilemma, trust, and dictator games.

In conclusion, the present study showed that cognitive reflection predicted decisions to unfair ultimatum offers: participants who scored higher on measures of cognitive reflection were more likely to accept unfair offers. These findings are consistent with the automatic negative reciprocity hypothesis and suggest that affective responses to unfair offers occur automatically and participants with the ability to inhibit the automatic desire to punish unfair proposers and cognitively reflect on their options are more likely to accept unfair offers. Alternatively, participants high in cognitive reflection may better understand that accepting any ultimatum offer is in their best interest.