A. Introduction

The issue of “constitutional identity” is a topic the relevance of which emerges in contemporary constitutional democracies in the context of constitutional changes. It has already attracted multilayered approaches in psychological, social psychological and social science studies, or as a phenomenon that is formed by and interpreted in political processes. Its legal conceptualizationFootnote 1 from a positive law or a European integration perspectiveFootnote 2 is, however, still underexposed. This failing needs to be addressed, especially because “constitutional or national identity” has become a legal phenomenon that is based on positive law—more particularly in Article 4.2 of the Treaty on the European Union (“Article 4.2 TEU”)—and has already been applied.Footnote 3 That is why the aim of this Article is to create an analytical framework to complement the existing doctrinal and normative views on the term “constitutional identity,” which eventually allows us a more compact understanding of “regional constitutional identity” and its interconnectedness with formal and informal constitutional change. For this purpose, this Article uses the “constitutional identity” as interpreted in Hungary, Germany, and Italy, exemplifying how the very same idea of “constitutional identity” can be detrimental to, and used to further unify and consolidate, European integration.

Based on case law studies and analysis of doctrinal works, this Article finds that for legal applicability, the term “identity of the constitution” may be suggested, as it better expresses the European and constitutional law context in which it is applied. This Article also concludes that the “identity of the constitution” is not necessarily a notion that threatens the unity and integrity of EU law, but rather is a firm statement about the current statehood of the Member States in the actual configuration of the EU. When courts engage in an open and collaborative dialogue, uniqueness may be seen as a commonality, given that the EU is based on the shared constitutional values of its Member States.

First, this Article reviews the legal sources of “constitutional identity” in the regional European context. Second this Article examines differences between “constitutional identity” and the “identity of the constitution.” Against this background, the “identity of the constitution” is then conceptualized by overviewing those provisions that may be seen as comprising the identity of the constitution, after which some implications and legal consequences are listed.

B. Legal Sources of “Constitutional Identity” and Its Interpretation in Europe

As stated in the introduction, constitutional identity, on the one hand, has gained a positive legal formulation in Article 4.2 TEU. Constitutions, on the other hand, do not include any provision containing the term “constitutional identity” or the like. The application of constitutional identity by constitutional courts has mainly been the result of defining the limits of EU law within domestic legal systems. There are three states—Germany, Hungary, and Italy—which have already used constitutional identity in their jurisprudence. In providing an overview of the jurisprudence on constitutional identity, first the position of the Court of Justice of the European Union (“CJEU”) is discussed, then a description of the most relevant German, Hungarian, and Italian cases is presented.

I. Position of the CJEU

Article 4.2 TEU has been active since the entry into force of the Lisbon Treaty in 2009. Member States have so far relied on Article 4.2 TEUFootnote 4 in cases referring to the official national languageFootnote 5 and to the abolition of the nobility,Footnote 6 in which the CJEU acknowledged that the national identity of the Member States should be respected. In the interpretation of the CJEU, the abolition of the nobility was considered part of the Austrian republican tradition, and the official national language in Lithuania was conceived of as a part of that state’s national identity. Other Member States, though unsuccessfully, further argued that the organization of the state and the distribution of powers between central, regional, and local levels—SpainFootnote 7—rules regulating access to certain professions—ItalyFootnote 8—and the protection of statehood and sovereignty—SlovakiaFootnote 9—also formed part of their constitutional identity as stated in Article 4.2 TEU.

Based on what little case law there is, the CJEU seems to consider constitutional identity as part of the proportionality test.Footnote 10 As Werner Vandenbruwaene asserts, it seems to be likely that “if a matter is closely related to the core of a member state’s constitutional identity, the margin of appreciation can be larger.”Footnote 11 The essence of this opinion seems to be backed up by the positions of the CJEU expressed in the Aranyosi and Căldăraru case of April 5, 2016Footnote 12 and the Taricco II Footnote 13 case. The attitude and language are, however, more cooperative and consensus-seeking in these rulings than might have been anticipated.

Article 4.2 TEU may be seen as triggering a dual designation, because within the EU, Member States refer to their constitutional identity, while the CJEU prefers to use the term “national identity.” The two terms, however, refer to the same obligation of the EU institutions—respect—and the same core element of the constitutional setting of the particular Member State—to be respected. The approaches of the CJEU and the national courts to the actual content of identity differ, though. The term “national identity” from Article 4.2 TEU applies to determining whether the actions of the EU are legitimate.Footnote 14 The term “constitutional identity,” based on the jurisprudence of the high courts or constitutional courts, has the aim of defending the constitution and constitutionality.Footnote 15 Previously, the debate about the clarification of the content of identity in Article 4.2 TEU focused on who would have the last word and how the dialogue between the CJEU and national courts would ease the tension between the different roles and approaches of these courts.Footnote 16 The practice has already provided answers, quite in line with doctrinal expectations:Footnote 17 An active and cooperative use of the preliminary ruling procedure and the application of integration-friendly arguments, which may result in a better understanding of national constitutional concerns.

II. Approaches of Member States When Applying EU Law

1. German Jurisprudence

The German Federal Constitutional Court (“BVerfG”),Footnote 18 in its Lisbon decision, consistently used the term “identity of the constitution,”Footnote 19 which differs from the phrase “identity of the Federal Republic of Germany.” This latter expression appears only once: “[T]he change of identity of the Federal Republic of Germany … would be effected by its becoming a constituent state of a European federal state, and the concomitant replacement of the Basic Law.”Footnote 20 Identity seems to equate in this respect to state sovereignty. Furthermore, the BVerfG declared that the inviolable core content of the constitutional identity of the German Basic Law (“GG”) appeared in Article 23.1, third sentence—EU clause—and Article 79.3 GG—eternity clauses. Apart from the obvious abolition of sovereign German statehood by creating a federal EU, the BVerfG claimed only certain aspects of competences belonging to the sovereign power of the state and the people not to be open for integration. It mentioned particularly the deployment of the army abroad as a core competence of the national parliament, which, however, does not exclude some technical integration—for example, coordination powers—and approval of the national budget with its link to popular sovereignty and representative democracy. These competences are associated with eternity clauses, in which the identity of the GG is palpable. The Lisbon decision, by its very nature, did not deliver identity review; but another ruling did, and yet another threatened to activate it.

In its Outright Monetary Transactions (“OMT”) preliminary reference decision of 2014, the BVerfG claimed that even if the CJEU were to consider the OMT decision to be in accordance with EU law, the BVerfG could examine whether it infringed upon the identity of the GG as protected by Article 79.3. It argued that, due to the Lisbon decision, democracy—a constituent element of the identity of the GG—would be violated if the Parliament renounced budgetary autonomy. It recalled that the CJEU is required to provide proportionate and relative protection of national identity—Article 4.2 TEU—as opposed to the protection of constitutional identity offered by the GG, which may not be balanced against other legal interests.Footnote 21

The CJEU, in the Gauweiler case, ruled that the OMT decision did not involve an ultra vires act. It also noted that the decision of the CJEU in the preliminary ruling procedure was binding.Footnote 22 Indeed, this decision of the CJEU was not followed by the promised action of the BVerfG. On the contrary, by referring to the Gauweiler decision, it refused a constitutional complaint that was later filed against the OMT decision.Footnote 23

The BVerfG, on December 15, 2015,Footnote 24 applying its identity review, refused to implement a European Arrest Warrant (“EAW”), as it would have meant the violation of the human dignity of the person concerned, stemming from the GG Articles 79.3 and 1.1. A similar issue as to content also worth mentioning, even if it did not use the term “constitutional identity,” arose in the Aranyosi and Căldăraru case, which is a good example of judicial openness and cooperation with a view to upholding the integrity of EU law. A German court was undecided about whether to permit the execution of two EAWs issued by Hungary and Romania due to their poor prison conditions—including overcrowding—which had already been condemned by the European Court of Human Rights (“ECtHR”).Footnote 25 The CJEU apparently offered an alternative interpretative method for constructing legal argument. It applied both Articles 1 and 4 of the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the EU and Article 3 of the ECHR in ruling that the consequence of the execution of such a warrant must not be that that an individual suffers inhumane or degrading treatment.Footnote 26

The BVerfG summarized and clearly separated its ultra vires review and identity review in the Summer of 2016.Footnote 27 When conducting its identity review, it examined whether the principles declared by Article 79.3 GG, along with Articles 1 and 20 GG, to be inviolable are affected by transfers of sovereign power by the German legislature or authorities of the EU. What we can observe here is that the identity review attempts to capture and protect the particularity and uniqueness of the GG as compared to other constitutions.

2. Hungarian Cases

The Hungarian Constitutional Court (“HCC”) established similar reviews in its decision 22/2016 (XII. 5.),Footnote 28 in which it responded to another kind of challenge, one different from that addressed by the Lisbon decisions of Member States. Before setting out the position and arguments of the HCC, some contextualization is needed. After a massive communication campaign,Footnote 29 the Hungarian Government called for a national referendumFootnote 30 against Brussels, politically speaking, and—putting it into more legal language—against its refugee quota decision, Council Decision 2015/1601 of September 22, 2015.Footnote 31 The EU quota referendum of October 4, 2016 was, however, invalid, and as such it imposed no legal obligation on the state. Nevertheless, its result was interpreted politically and was seen as the expression of the will of the vast majority of voters, which the political leadership must address by a constitutional amendment. The draft Seventh Amendment of the Fundamental law of Hungary (“FL”) was submitted to the Parliament by the Prime Minister on October 10, 2016, but it did not get the necessary two-thirds support at the beginning of November 2016. To put it bluntly, the eventually unsupported constitution-amending power was intended to—uniquely, when compared to other Member States of the EU—constitutionalize constitutional identity as a defense mechanism against the Council Decision on refugee quotas. This amendment failed, but on November 30, 2016, the already packed Constitutional CourtFootnote 32 declared in its ruling 22/2016 (XII. 5.) that, by exercising its competences, it could examine whether the joint exercise of competences under Article (E)(2) FL infringed upon human dignity, other fundamental rights, the sovereignty of Hungary, or Hungary’s self-identity based on its historical constitution. This procedure had been initiated almost a year before, in December 2015, by the Commissioner for Fundamental Rights, but, interestingly, the HCC happened to deliver the decision just after the parliamentary rejection of the Seventh Amendment.

In this decision,Footnote 33 the HCC based its fundamental rights-reservation review on Articles (E)(2) and (I)(1) FL. The latter provision declares that the inviolable and inalienable fundamental rights of man shall be respected. It shall be the primary obligation of the state to protect these rights. It argues that as the state is bound by fundamental rights, this binding force is also applicable to cases in which public power, under Article (E), is exercised jointly with the EU institutions or other Member States. The ultra vires review is seen to be ultimately reserved to the HCC. Here, it identified two main limits on the conferred or jointly exercised competences under Article (E)(2): They cannot infringe the sovereignty of Hungary—sovereignty review—and they cannot infringe the constitutional identity—identity review. These limits followed from an interpretation of the National Avowal, which is not elaborated on at all in the decision, and Article (E), which refers to an international treaty, for example, Article 4.2 TEU. The HCC confirmed that the objects of these tests are not specifically EU law or its validity, and, through Article (E)(2), based the identity review on Article 4.2 TEU. It acknowledged that the protection of constitutional identity rests with the CJEU and is based on continuous cooperation, mutual respect, and equality.

In the understanding of the HCC, constitutional identity, which is a fundamental value that had not been created but only recognized by the FL—and therefore could not be renounced by an international treaty—equates to the constitutional identity of Hungary. Its content is to be determined on a case-by-case basis, founded on the FL as a whole and its provision under Article (R)(3), which requires that the interpretation of the FL shall be in harmony with its purpose, the National Avowal contained therein, and the achievements of the historical constitution. Even though the HCC held that the constitutional identity of Hungary did not comprise an exhaustive list of values, it nevertheless referred to some of them, such as, for example: Freedoms, the division of power, the republican form of state, respect for public law autonomies, freedom of religion, legality, parliamentarianism, equality before the law, recognition of judicial power, and protection of other nationalities living within Hungary. These equate to modern and universal constitutional values and to the achievements of the historical constitution on which the Hungarian legal system rests.

3. Italian Case Law Series

Italy apparently adopts a more cooperative approach, which seems to be in line with what we might expect the attitude of the CJEU to be regarding Germany. The most recent example is the Taricco saga, consisting of two preliminary ruling procedures—one from an ordinary court, the other from the Italian Constitutional Court (“Italian CC”)—and two CJEU rulings.

In its Taricco I judgment, the European Court of Justice (“ECJ”) ruled that national courts must disapply the rules regarding periods laid down in statutes of limitation for the duration of criminal proceedings pending before a court if such rules were “liable to have an adverse effect on fulfilment of the Member States’ obligations under Article 325 TFEU.”Footnote 34 Article 325 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (“TFEU”) requires that Member States counter fraud and any other illegal activities affecting the financial interests of the Union through deterrent measures. According to the ECJ, by disapplying the statute of limitation periods, the national court would not breach the principle of legality, nullum crimen, nulla poena sine lege, as enshrined in Article 49 of the EU Charter. This is because the Charter covers only substantive criminal provisions—for example, those determining the types of crimes and sanctions—while the principle of legality is considered to be a purely procedural matter that falls outside the scope of the principle of retroactivity in criminal law. Thus, disapplying these rules would ensure the effective prosecution of crimes that had already been committed, but it would not result in retroactive criminalization. The accused would be held criminally responsible only for those acts that constituted crimes at the time when they were committed.Footnote 35

The Italian CC used the notion of constitutional identity for the first time in its Decision No. 24/2017, when it asked the ECJ to clarify whether its ruling in Taricco actually left national courts with the power to disapply domestic norms, even to the extent that this contrasted with a fundamental principle of the Constitution, namely, the principle of legality in Article 25. In fact, the Italian CC, as early as 2014, had already interpreted the principle of legality as prohibiting a retroactive application in peius of statutes of limitation, that is, the statute of limitations in Italy is deemed to be part of the substantive criminal law.Footnote 36 The Italian CC asserted in the judgment that the rule inferred from Article 325 TFEU is only applicable if it is compatible with the constitutional identity of the Member State, and it falls to the competent authorities of that State to carry out such an assessment.Footnote 37

In its Taricco II judgment, the ECJ did not use the word “identity,” but, following the EU law-friendly language and approach of the Italian CC, it recognized that the nullum crimen and nulla poena principles form part of the constitutional traditions common to the Member States.Footnote 38 It ruled that Article 325 TFEU must be interpreted as requiring the national court to disapply national provisions on limitation, forming part of national substantive law, which prevent an effective response to fraud and any other illegal activities affecting the financial interests of the EU, unless that disapplication entails a breach of the principle of legality.

III. Further Scope of Application of Constitutional Identity: Hungary—Contrary to International Obligations

In his dissenting opinion in HCC Decision 23/2015 (VII. 7)—which is shared by the other four justices—András Varga Zs. specifically referred to “constitutional identity” in connection with the ECtHR ruling in Magyar Keresztény Mennonita Egyház and Others v. Hungary. The ECtHR declared that the applicants’ right to religion was infringed upon by the Hungarian state because it had: (1) Removed the applicants’ church status altogether rather than applying less stringent measures; (2) established a politically tainted reregistration procedure whose justification as such is open to doubt; and (3) treated the applicants differently from the incorporated churches not only with regard to the possibilities for cooperation but also with regard to entitlement to benefits for the purpose of faith-related activities.Footnote 39

The HCC based its decision on the ECtHR ruling and held the Church Law and some other legal acts to be contrary to the ECHR, calling upon the Hungarian Parliament and Government to take the necessary measures to resolve the conflict before October 15, 2015.Footnote 40 András Varga Zs., in his dissenting opinion, considered the regulation of the FL, which differentiates between religious communities and established churches—which are religious communities cooperating with the state in order to achieve goals of the community—to be a peculiarity of Hungary’s constitutional history and an essential component of its constitutional identity. In his view, constitutional identity is derived from otherwise unspecified historical facts that are recognized by the FL.Footnote 41 He listed the conditions, set by the Church Law, by which a religious community may become an established church under the heading of “constitutional identity.”Footnote 42 In his opinion, the HCC had ignored the distinction between “religious community” and “established church” included in Article VII of the FL, because this HCC ruling, based on the ECtHR decision, classified these criteria as conflicting with international treaties. He concluded that although Hungary is obliged to execute “ECtHR decisions, it is not obliged to abandon its constitutional identity based thereupon.”Footnote 43

C. “Constitutional Identity” and the Identity of a Constitution

From the case law, it follows that the legally applicable concept is the “identity of a constitution,” which is not a widespread idea among scholars. It raises the questions of how a constitution could, and why it should, have any identity. The answers lie in the psychological and social-psychological meanings of identity and in the notion and role of a constitution in a constitutional democracy. Therefore, when studying “constitutional identity” or the “identity of a constitution,” it is advisable to start with an overview of the notion’s non-legal concepts, as they—along with their doctrinal analyses and judicial practices—may provide a suitable framework for understanding “constitutional identity” and conceptualizing it as an “identity of a constitution” from a constitutional law perspective.

I. About Identity: A General Approach

Identity is closely related to the self in terms of sameness—I am still myself and nothing else, regardless of any changes I may have experienced—and selfhood—I am myself as against all others. There is no identity without something else against which I can identify myself as me. Nor is there the possibility of being aware of this “difference” or “otherness” without knowing myself and the other in the face of which I have remained myself. Thus, defining ourselves and the other is always necessary.Footnote 44 The definition of identity regarding individuals was made relatively early on in social science studiesFootnote 45 as to mean social or collective identity.Footnote 46 Identity is self-identity at all times and in all circumstances—the individual self. But it also refers to the fact that an individual is himself or herself and no one else—the relational selfFootnote 47—and to identification with a group or community, the collective self.Footnote 48 Identity develops during interaction with others, and it can be derived from the pattern that results from the acknowledgment of, and getting to know, ourselves.Footnote 49

In the case of social identity, the supra-individual sense of identity in social groups is at the forefront of scientific interest. This identity of a collectiveFootnote 50 is composed of, for example, national, racial, sexual, professional, and family identities, among others. According to sociologists, we have various overlapping group identities, and the theoretical or ideological roots of the particular identities appear as key issues when analyzing identity.Footnote 51 From the perspective of a historian, collective identity is the sense of social affiliation based on the sharing of common knowledge and memories. The latter may refer to traditions, history, and the communicated, spontaneously, or artificially created cultural memory. On the one hand, the past held in the memory changes into social and cultural knowledge and practice, which creates an identity. On the other hand, historiography that is adjusted to particular national canons may result in another definition of the past according to certain other collective identities. Accordingly, for psychological reasons, the past is interpreted in a way that suits the interpreters, and only those elements of the past which satisfy their interest are acknowledged—and this is based on historical experiences.Footnote 52 Individuals, however, from the standpoint of social psychology, accept and comply with the norms of a group to which they are more attracted and with which they are affiliated, and they will only leave it if it is no longer able to offer them a positive image of identity.Footnote 53 Therefore, collective identity presupposes identical values and consensus about their existence and importance. The driving force behind their preservation is the protection and maintenance of political power.Footnote 54 Thus, the process of creating an identity is also a political process; different conclusions and consequences will arise from various senses of identity. Communication about identity therefore also covers a particular type of mindset and political or philosophical conception.Footnote 55

There are other models of identity. According to the hierarchic model of identity, in which ethnic identity is dominant, we can see one of the possible models of nation-stateFootnote 56 formation. Identity types—ethnic, religious, regional—affect, influence, and determine one another, and throughout history, depending on the historical era, one element or another becomes dominant.Footnote 57 According to the theory of concentric circles, there is no hierarchic relation between identities;Footnote 58 instead, the identity of an individual is multiple and situational. Nowadays, taking globalization and integration processes into account, collective identities emerge that are connected to regional, ethnic communities and supranational entities.Footnote 59 All these may be best expressed in a European context by borrowing the words of Anna Śledzińska-Simon, referring to Willfried Spohn, who argued that it can be generalized that the interplay between the individual, the relational, and the collective selves takes the form of “a triadic interaction between national identities, European civilizational identities and identifications with the European integration project.”Footnote 60 In the collective constitutional dimension of the self, the question of whether constitutional identity in a nation-state in Europe can dismantle the European identity—or, vice-versa, whether European constitutional identity dismantles the constitutional identity of the nation-state—has no basis, because the two notions are not exclusory but complementary.Footnote 61 This approach remains in a social science context and does not really help to legally conceptualize “constitutional identity.”

II. Analysis of Doctrinal Views on “Constitutional Identity”

If we want to grasp the definition of identity from a constitutional law perspective, it is necessary to define whose constitutional identity we are talking about, why we are talking about that particular identity, what the components of that identity are—as individual self—, by which actor, against whom—a relative self—and how, or in what legal process, we define the constitutional identity. Furthermore, we should not forget to specify the legal consequences attached to the violation of the constitutional identity. This understanding clearly differs from that of applying to the identities of a person or a group, or even of the constitutional subject. It provides another, more legally grounded approach, as compared to, for example, that of Rosenfeld, who is interested in the relation between the identity of a constitution and other relevant identities, such as national, religious, or ideological identities. Therefore, in connection with constitutional identity, Rosenfeld emphasizes “sameness” or “selfhood” but does not significantly examine its flip side, which can be expressed as “difference from others” or “otherness” and which follows on from “selfhood.”Footnote 62 Jacobsohn takes a similar approach, but he considers constitutional disharmony as a driving force for the dynamic in which identity emerges. According to him, identity is not to be discovered but “emerges dialogically and represents a mix of political aspirations and commitments that are expressive of a nation’s past, as well as the determination of those within the society who seek in some ways to transcend the past.”Footnote 63 For those authors, constitutional identity appears to serve as a special “mechanism” or “procedure” that facilitates the understanding of constitutional change. Neither of them, however, use the terms “constitutional identity” and “identity of the constitution” consistently. It is also not entirely clear whose constitutional identity they refer to,Footnote 64 nor what the difference and the relationship is between constitutional identity, the identity of the constitution, and sovereignty, legitimacy, the nation-state and nation building, and constitution making and constitutional change or constitutional amendments.Footnote 65

The difference between these existing doctrinal views and the legal approach suggested in this Article lies right at heart of the questions asked. Rosenfeld, posing questions similar to those set out above, stated that “constitutional identity must be molded to guide answers to three principal questions: To whom shall the constitution be addressed? What should the constitution provide? Moreover, how may the constitution be justified?”Footnote 66 These are obviously and indisputably legitimate questions if we are interested in the identity of the constitutional subject, but from a legal perspective, which emerges on the basis of Article 4.2 TEU, these questions raise general issues that each constitution should be able to answer even without addressing the issue of identity. Modern constitutions have been adopted since the beginning of the nineteenth century, and no one has been particularly interested in constitutional identity from a practice-oriented legal perspective until recently. As Monika Polzin explains, in Germany, the concept of constitutional identity was only used in 1928, in the theories of Carl Schmitt and Carl Bilfinger, to justify the limits of constitutional amendments to the Weimar Constitution. Under the regime of the GG, it reemerged in the legal doctrine regarding the same subject matter, and it was used by the Constitutional Court vis-à-vis European law, as mentioned above.Footnote 67 In Italy, as concluded by Fabbrini and Pollicino, there were no peculiar historical and cultural conditions that could have triggered a strong nationalist feeling; therefore, they have detected the absence of a constitutional identity mentality in Italy when reviewing the practices of the Italian CC and the Presidents of the Republic, though they admittedly did not take a purely judicially focused approach.Footnote 68 András Cieger explains that in Hungary, due to different canons of historical interpretation, concurrent explanations of the past existed following the democratic transition, which may be blamed on the fact that a new constitutional patriotism was unable to emerge during the twenty years after transition when a chaotic mixture of traditions and values could be observed.Footnote 69

Even if Rosenfeld and Jacobsohn consider, elaborate, and theorize actual constitutional development and existing constitutional amendments, the main idea behind their theories is still certainly not driven by a legal viewpoint. Furthermore, they are not continental and EU jurisdiction oriented. Still, their concepts can be used as a source of inspiration in unfolding and understanding the different layers of the notion of constitutional identity. They clearly explain the constitutional identity of the constitutional subject, which must always be considered during the democratic constitution-making and changing processes.

In contrast to these theories, François-Xavier Millet,Footnote 70 when researching the constitutional identity of France, focused on it in the context of European integration. In his view, constitutional identity cannot be drawn only from the principles laid down in the text of a constitution; it also involves elements connected to the cultural and historical background of the state. In his opinion, which, to a certain extent, displays similarities to the non-judicial concepts mentioned above—this is why the subject of constitutional identity is not clear—time is an important factor. Constitutional identity originates in the past but contains commitments concerning the future; furthermore, the elements of constitutional identity are not set in stone but are always evolving. In the case of France, due to the democratic tradition, Millet detects constitutional identity in the principles of secularity and equality and also in social and environmental law. Constitutional identity does not, probably intentionally,Footnote 71 appear in the jurisprudence of the Constitutional Council; instead, it is scholarly literature that tries to detect the exact meaning of the “rule or principle inherent in the constitutional identity of France,” which is linked to the “constituent authority.”Footnote 72 It seems, however, that it refers to some individual components of the French Constitution, (and not the identity of the state or the people) that do not have their counterparts in EU law.Footnote 73

Pietro Faraguna also focuses on the content of identity in the context of European integration and explores how Article 4.2 TEU should be interpreted for the purpose of smoothing the integration project and the experience of national constitutional orders.Footnote 74 Thus, the conceptualization of constitutional identity from a constitutional law perspective has not been accomplished. It is also absent from the work of Gerhard van der Schyff, who conceives that “identity as content and context serves to distinguish constitutional orders according to the choices made by that order.” This claim is promising, but it loses its application as a legal concept when he adds that “constitutional identity can be found wherever constitutional customs and rules are present that sustain a framework for governance, including checks and balances such as the protection of fundamental rights.”Footnote 75

In their contributions published in 2013, some authors—and even the editors—explored the concept of “national constitutional identity.”Footnote 76 Toniatti takes the position that constitutional identity is a “transformation of the use of sovereignty.”Footnote 77 Claes argues that it is “closely related to the concepts of sovereignty, independence and national democracy.”Footnote 78 And Bofill challenges the view that it can be “characterized as a ‘counter-limit’” but is “associated with the primary source of political legitimacy.”Footnote 79 Even though these works adopt a more legal perspective than others, their use, given that they reflect the situation up to 2012, has now become quite limited, but they do still offer a constructive start to the development of the legal notion of the constitutional identity.

Constance Grewe offers a constitutional law-oriented technical approach to identifying the national constitutional identity, as she calls it, which she finds in several indicators, such as in constitutional amendments and the introductory provisions of constitutions.Footnote 80 Biljana KostadinovFootnote 81 sees constitutional identity as a special form of national identity. In her view, national identity is a psychological and sociological phenomenon that embodies a totality of conscious and unconscious elements that develops the bond with a certain community. This perception of national identity shows similarities to the constitutional identity concept of Rosenfeld and Jacobsohn. In the integration context, the core of the constitution that needs to be protected is the part in which the integrity of those who created it appears. It embodies the provisions on the right of the people to decide on and pass the constitution in a free and democratic procedure.Footnote 82

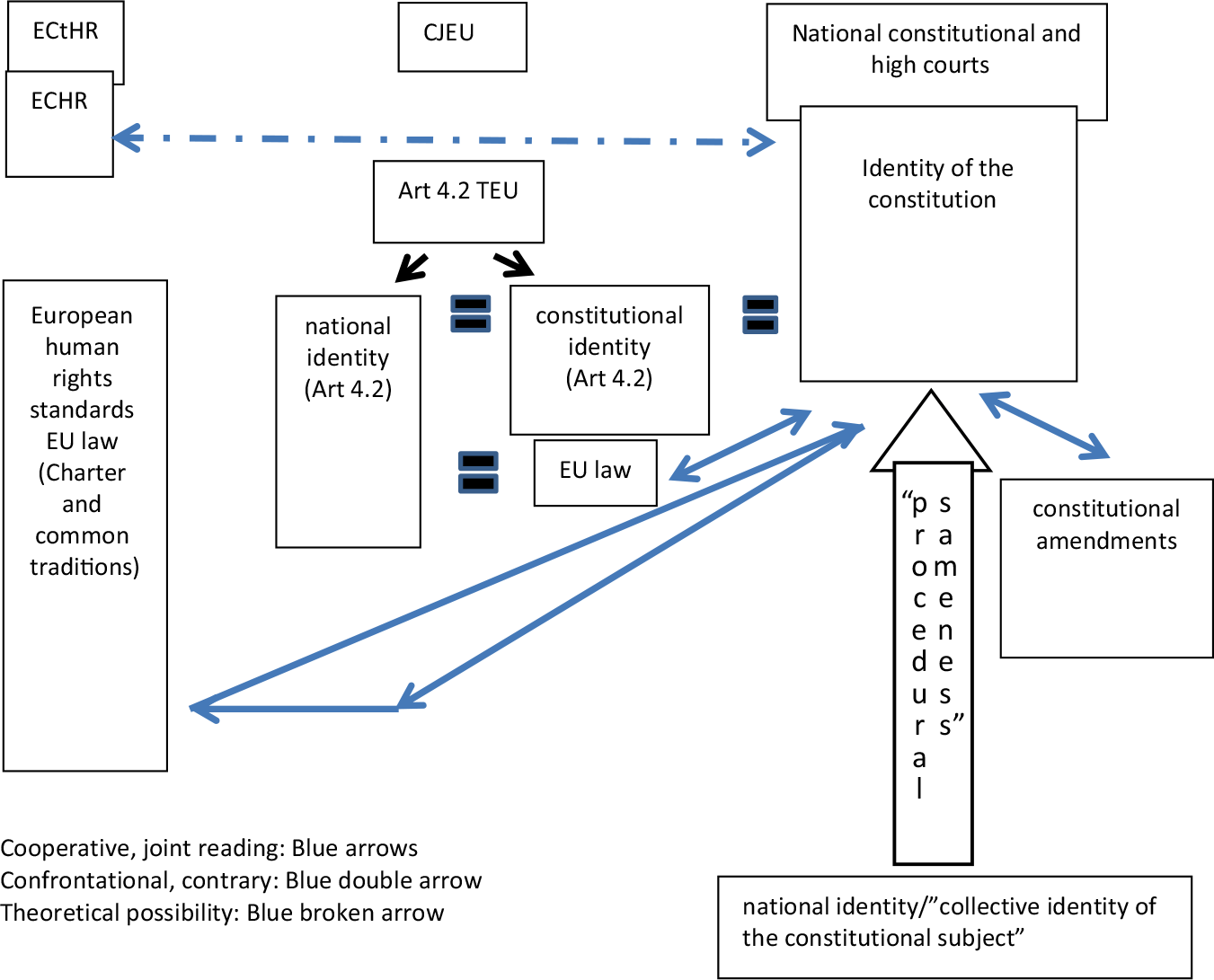

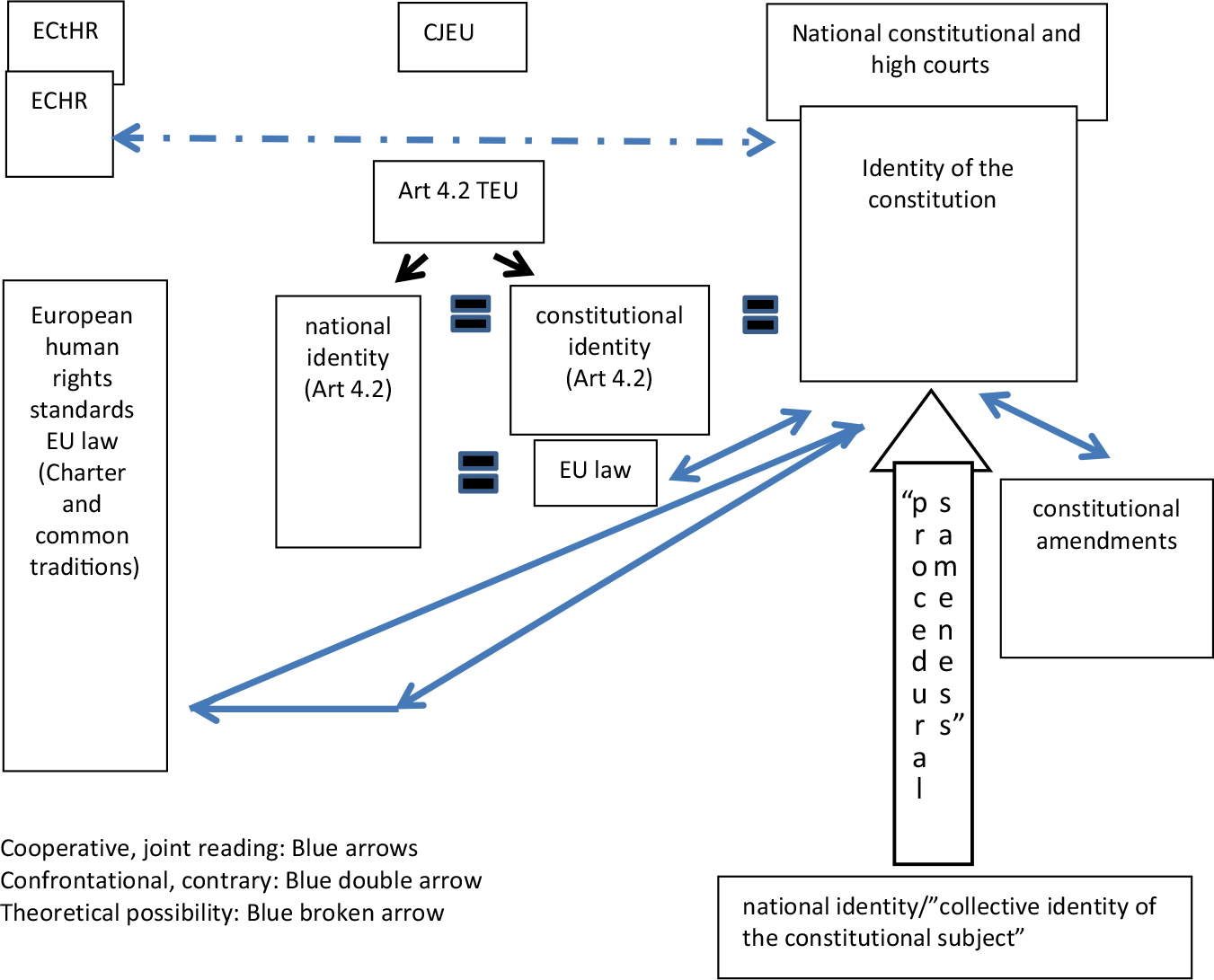

It can be seen that approaches toward constitutional identity differ, and that the conceptualization of this notion from a constitutional law perspective is largely absent. As has already been noted, however, constitutional identity has become a legal notion to be invoked in legal processes. Nevertheless, this identity of the constitution has to be in harmony with the social and cultural developments in which the constitutional identity—as generally viewed by Jacobsohn and Rosenfeld as reflecting disharmonyFootnote 83 or a lack that must be overcome through a discursive process, and the reactions this lack triggers,Footnote 84 or as a national identity, as Kostadinov views it, but comprising a particular “collective identity of the constitutional subject”—emerges and is molded. The understanding of “collective identity of the constitutional subject” advocated by this Article embraces the ideal expressed by Biljana Kostadinov on the importance of the right of the people to get involved in the constitutional legislative making and amending processes. I would suggest that this should be considered as a constituent element of the legal concept of “constitutional identity” and called “procedural sameness/selfhood.”

The legal understanding of constitutional identity and the general notion of the “collective identity of the constitutional subject” are discussed below by answering the questions—who, why, what, which actor, against whom, and how—posed at the beginning of this Section. As a result, a more detailed legal notion of constitutional identity is offered, one that is more distinctive in comparison to other existing notions of constitutional law, such as constitution-making, constitutional amendment, and legitimacy.

D. Conceptualization of the “Constitutional Identity” as the “Identity of the Constitution”

Following on from the recent legal development of the application of constitutional identity in judicial practice, one of the fundamental questions to be asked is: “Who or what can have a constitutional identity, and how can they acquire it?” The Hungarian constitutional order has embraced the term “constitutional identity of Hungary,” which is rooted in its historical constitution. Based on the case law of the German and the Italian Constitutional Courts, it seems to be the constitution which has identity. Therefore, clarification of the holder of constitutional identity is needed:Footnote 85 Whether it is the constitution—as more examples suggest—which is a “lifeless” legal norm; the state, which is a legal—or political or social, depending on the particular perspective—abstraction; or the people, whose identity seems to be studied in the aforementioned doctrinal works, as the subject of constitution-making, original or primary power constituent, and constitution-amending power, derivative or secondary constituent power.Footnote 86 If the term “constitutional identity” has something to do with the “constitutional” basis or “constitutionality,” further demarcations need to be drawn from existing constitutional law concepts, such as legitimacy, state sovereignty, popular sovereignty, and national identity.

I. Whose Identity are We Talking About?

1. Identity of the People or the Nation?

From a positive constitutional law perspective, constitutional identity may be perceived as the self-identity of the nation or the people as a “collective identity of the constitutional subject,” provided that these terms—nation and people—are incorporated in the constitutional text. Otherwise, it would not make much sense to call a phenomenon “constitutional.” During the exercise of political power, both the people and the nation—depending on the particular historical context—can define themselves as a constituent power, or as practicing their powers directly—via plebiscite and referendum and indirectly—electing representatives—within its framework. This, however, already has a name in constitutional law—national sovereignty or popular sovereignty—which presupposes the existence of other identities at the individual or societal level, for example, national, religious, or cultural identities. Thus, by exercising popular power, the people or the nation constitutionalize the most important aspects of their “collective identity,” which in the scope of this Article equates with “national identity,” or they make formal or informal adjustments to it.

The concept of “national identity” as applied here is not the same as the definition stipulated in Article 4.2 TEU or revealed in the interpretation of the CJEU. National identity in this context, viewed as the “collective identity of the constitutional subject,” is a much broader concept. It is seen as an identity that reveals itself as the basis for the constitution-making and constitution-amending processes, and as such, it is rooted in those customs and experiences of the political community, including, for example, nationalities and religious, cultural, and linguistic considerations, that the constituent power or the constitution-amending power, at a given moment in history, deems it important to constitutionalize. This national identity has its origins in different “identities” and is shaped by conscious and subconscious components, which create affiliations, connections, and commitments to a particular community, and as such, it is a psychological and sociological phenomenon.Footnote 87

The concept of national identity can be viewed differently by the constitution-making and constitution-amending power when shaping the constitutional definition and content of the legal nation, the demos-oriented Western European approach, and the cultural nation, the ethnos-oriented rather CEE approach, by moving one or the other to the fore in the text of the constitution. In this scenario, national identity, as a collective identity of the constitutional subject presupposing identical values and consensus, first presents itself in the act of constitution drafting, and the aforementioned different identities are prerequisites. In this context, national identity and constitutional identity are not interchangeable. They are in an antecedent–consequence relation with each other. The national identity appears in the act of constitutional drafting and flows into the text, thus becoming the constitutional identity. This constitutional identity, because of the integrating function of the constitution, not only must be capable of being generally acceptable, but the constituent people and nation must also be able to identify themselves with it, regardless of or due to the diversity of society. Constitutional texts should use different languages and should frame different identities in a multinational, multiethnic, and multilingual society more so than in a less diverse state. Therefore, constitutional identity can highlight and strengthen the national identity, the collective identity of the constitutional subject. A constitution of a constitutional democracy cannot be discriminatory; it should express a minimum consensus, and everyone has to identify themselves with it to at least a small degree. It means that they agree with the values, principles, and procedures it contains, and that they can accept them as the core rules for coexistence in a state. There are different techniques—such as inclusive drafting and adaption processes, referendums, participatory multi-tiered constitutional amendment mechanisms,Footnote 88 and the designation of constituent people—for achieving a substantively and formally inclusive constitution. At the same time, however, at least partly, it is a question of legitimacy, which is another prerequisite of the legal concept of constitutional identity, and in some cases its consequence. The constitutional identity, as the collective identity of the constitutional subject, expressed explicitly or implicitly in the constitution, may react to identities at the level of the individual and society, which in turn may eventually present themselves in constitutional law as constitutional amendments or may lead to the drafting of a new constitution.

If constitutional identity were to mean the identity of the nation or people, it would be difficult to differentiate it from sociological and psychological concepts, constitution-making and amending processes, and legitimacy.

2. Identity of the State?

If we assume that the state has constitutional identity, it certainly cannot legally and legitimately exempt itself from the identities which appear in the constitution due to the supremacy of the constitution—legal sovereignty. Neither can it politically disregard the national identity and all the underlying identities described above that influence the will of voters. Obviously, the state can have self-identity in the sense that it is “self-identical” at a state level; it differentiates itself from other states. In the constitutional law context, this ability and its substance are described in the well-known definition of state sovereignty, the fundamental components of which are embodied explicitly or implicitly in state constitutions. A state can be “self-identical” regarding its politics as well, being different from previous or foreign political decision makers, although this identity, defined by politics, must always respect constitutional limitations.

If constitutional identity were to be applied to a state, it would simply mean state sovereignty as constituted and restricted by the constitution, which would lead to a narrow understanding of self-identification. In the context of pluralistic sovereignty, the people and nation, by their popular sovereignty, in the course of constitution-making, constitute the constitution and the state, the constitution setting out the ways in which the people can exercise their popular sovereignty within the new constitutional setting. The same legal sovereignty—supremacy of the constitution—restricts the actions of the state, in other words, state sovereignty.

3. Conclusion: Identity of a Constitution

The conception of the people or the nation or the state as the holder of constitutional identity persists in the analytical framework of existing doctrines and notions of constitutional law and theory. It brings us no closer to the legal conceptualization of this notion, however, as constitutional identity in this sense already has its equivalent in terms of popular and state sovereignty and legitimacy. Against this background, and the practices experienced in Europe, the most convincing holder of constitutional identity, which can be invoked in legal proceedings, seems to be the constitution itself. If its subject is not the self-conscious individual or representatives of the state but the constitution, an authority has to be found which can, through interpretation, determine exactly what constitutional identity is and what its scope of application is. This interpretive authority undertakes constitutional interpretation, which is binding if delivered by constitutional or ordinary courts. Such interpretation can be carried out by jurisprudence or by a political actor as well, leading to a jurisprudential or political interpretation of constitutional identity.

II. The Identity of the Constitution: Textual Analysis

There is no identity without knowing myself—sameness and selfhood—and the “something else” against which I identify myself as me; there is no identity without the individual, relational, and collective self.Footnote 89 From the European case law it seems that the term “constitutional identity” is used in many ways—confrontationally and cooperatively—to preserve the uniqueness of the constitution and, consequently, the sameness of the state and its people. The collective identity of the constitutional subject, or national identity, which the constitutional subject as constituent deemed to be as important to incorporate in its constitution, is expressed in various provisions in different constitutions. The constitutional identity is thus conceptualized as the identity of the constitution.

1. Designation of the State and Its Constituent People

Provisions expressing the “collective identity of the constitutional subject” may cover many parts of the constitutional text, starting with the name of the constitution, the name of the state and its symbols, national or official languages, and statehood. The subject of the constitution-making and amending power, which in the majority of cases is located in constitutional text, may tend to correlate with the historical sentences of the preamble.Footnote 90 But in fact, in the EU, out of the twenty-seven Member-State-written constitutions, eleven do not have a preamble. The constitutions of most Western European states—France, Italy, Germany—have only a symbolic preamble, and others—mainly post-socialist countries and Portugal and Spain—have a rich and comprehensive preamble to define their own national identities in the face of their previous oppression. Post-socialist states emphasize their national historical traditions, morals, and values as a reaction to the decades-long oppression by the Soviet Union. The preambles of Spain and Portugal also show a clear contrast to the previous authoritarian regimes.Footnote 91

As for the designation of the constituent people or the body that actually adopted the particular constitution, Member States display a great variety, but there are distinct models. Constitutions have been adopted by: A constituent assembly in Bulgaria, Germany, Italy, and Portugal; the parliament in Hungary and Slovenia; citizens together with the freely elected representatives in the Czech Republic and Slovakia; and by the people or the nation. There are also many versions of how the people or the nation came to adopt a constitution: The people may have adopted it acting alone, such as in France and Ireland; together with minorities living in the state, such as in Croatia; following a referendum, such as in Estonia and Spain; or the nation, which consists of the citizens, may have adopted it, like in Poland and Lithuania. Countries that have historically experienced extensive border changes, like Hungary, Croatia, and Slovakia, grant their minorities special constitutional status by elevating them among the constituent people of the state and constitution.

2. “Procedural Sameness”

The “procedural sameness” of the constitutional subject, in order to keep it as the final determinant of the constitutional text, is ensured by a pluralistic and inclusive constitution-making process, a tiered amendment mechanism, and seemingly entrenched decision making in European matters.

As, theoretically, it is the will of the people which is articulated during the constitution-making process and expressed by the constitution-making power, and which is as a result written into the text of the constitution, the identity exposed in the constitution should reflect the national identity. The people can thus accept the manifestation of their national identity in the constitution, which means that the constitution and its identity have legitimacy.Footnote 92 It is just another reason why the democratic and deliberative character of the constitution-making process is of importance, and why the type, model, and method of this process may be determinant.Footnote 93 Therefore, agreeing with the assessment of Biljana Kostadinov,Footnote 94 the right of individuals to choose and accept the constitution in a free and democratic process, in the course of which the free will, self-definition, and human dignity of individuals are manifested, may be viewed as the procedural aspect of the identity of the constitution that needs to be protected. The constitutions of most EU Member States, for example, Austria, Ireland, Italy, Poland, and Slovenia, require a referendum as part of the amendment process; whereas in Hungary, the FL prohibits the adoption and amendment of the constitution by popular referendum and puts this entire process into the hands of the parliament.Footnote 95

In the vast majority of cases, the reference to the people or nation who adopted the constitution is associated with the amendment process as well. The amendment process may require the involvement of the people for example in Austria, where, for the total revision of the constitution it is obligatory, but this involvement is excluded in Germany and Hungary. In some cases, such as in Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia, Moldova, and Serbia, a tiered procedure is used, which, as Rosalind Dixon and David Landau put it, creates “different rules of constitutional amendment for different parts of the constitution,”Footnote 96 in which certain provisions, usually eternity clauses, may be altered only by referendum. Other parts of the constitution are modified by the parliament. The tiered mechanism for constitutional amendment aims to preserve “the core of the constitution against destabilizing and antidemocratic forms of change” and help to build a constitutional identity.Footnote 97 In Poland and Austria, less demanding but still slightly more detailed procedural rules apply.Footnote 98 In Poland, it is questionable whether even a more demanding tiered constitutional amendment could preserve democracy and the identity of the constitution. The Polish Government, since 2015, has systematically dismantled the constitutional system established by the 1997 constitution.Footnote 99 The technique used has been to change the meaning of the constitution by informally amending it. Due to lack of political support, the constitution could not be properly and formally amended. The change, which amounts to the overturning of the constitution, is accomplished informally by the adoption of purely and obviously unconstitutional laws, and by the pursuit of unconstitutional practices. In Croatia and Italy, the tiered mechanism, unlike in other states, is not designed around a particular part of the constitution but entrenches a special referendum procedure.Footnote 100

Most Member States have called referendums on accession to the EU and treaty reforms, and with regard to the latter they usually require super majority voting. In 2003, the states that would later join the EU in 2004, except Cyprus, held referendums. In Hungary, even the accession referendum question was incorporated into the constitution, and each constitution was made “open to the EU” by adopting EU clauses, extending the right to vote to elections to the European Parliament, and adjusting the relationship between national governments and parliaments in integration matters. It seems safe to say that constitutions are including these provisions because the people wanted them there, as they have decided to belong to a European community in its legalized, actual version. When the people do not agree with the actual direction of European development—European constitution project— they have opposed it, even in the face of an already adopted constitutional amendment, as happened in France.Footnote 101

3. Principles Entrenched

The collective identity of the constitutional subject may also be discovered in the principles uniquely featuring the state and the constitutional order, among which eternity clauses emerge. Several constitutions contain eternity, or quasi-eternity, clauses, such as the GG in Germany, the Italian, Czech and Polish constitutions, but not the Hungarian FL. Principles uniquely featuring the state and the constitutional order cover the form of state—monarchy or republic—the form of government, the commitment towards the rule of law and human rights protection, and democracy, which is associated with popular sovereignty. The territorial structure—unitary, regional, federal, or devolved—is also a distinct feature, which usually has a historical background, without which the state will not be the same. That is why, usually, articles on territorial structure are entrenched as eternity clauses, for example, in Germany, Austria, and Spain.

4. Conclusion

The identity of the constitution is found among the provisions of constitutional texts and related jurisprudence that specifically and exclusively feature a status that was drafted during the constitution-making process and shaped by either formal or informal constitutional amendments. The identity of a constitution may differ from jurisdiction to jurisdiction, and the applicability of constitutional provisions may be subject to the jurisdiction of the respective constitutional or high courts. The constitution, by including these provisions, may have its individual and collective and relational selves, which are, as a second tier, sustained by procedural rules on constitutional amendment processes that create the link with the people—the collective identity of the constitutional subject. Democratic constitutions need to reproduce the will of the constituent people and also be able to adjust to any change of the collective identity of the constitutional subject by this subject, the people. Both the state and the people, when considering these constitutional provisions, can experience the individual, the relational, and the collective, and the “procedural” sameness and selfhood.

Figure 1 shows the interconnectedness and graphic imagery of the conceptualization of the identity of the constitution, as explained above.

Figure 1: The Identity of the Constitution

III. The Application of the Identity of the Constitution

Based on the three states that have already developed and applied the legal term of “constitutional identity,” there can be three models, two attitudes, two legal procedures, and one communication channel detected in which the notion of constitutional identity displays legal relevance. The three models are confrontational with EU law, confrontational individualistic detachment, and cooperation with embedded identity; the two attitudes are EU-friendly and antagonistic; the two legal procedures are against EU law and constitutional amendments; and the one communication channel is preliminary ruling procedure. As has been said, when referring to constitutional identity, based on judicial practice and an overview of doctrinal views, the term “identity of the constitution” is offered. The identity of the constitution encompasses provisions which feature the uniqueness of the state and constitutional order and which can be used in legal procedures, such as vis-à-vis EU law and constitutional amendments, and in the face of international human rights obligations.

1. Application Vis-à-Vis EU Law and International Human Rights Obligations

Reading eternity clauses as establishing constitutional identity was triggered by the reform of the EU via, especially, Article 4.2 TEU, and they appeared in the jurisprudence of the BVerfGFootnote 102 in and after the Lisbon decision in 2009. It follows that the identity of the GG covers immutable provisions and the very essence of state and popular sovereignty. German courts hold a confrontational position vis-à-vis EU law, but after a power play and consultation with the CJEU, the identity claim, based on Article 4.2 TEU and the identity review,Footnote 103 seems to have been subsumed within the European human rights protection ensured by the EU Charter and the ECHR as far as human dignity is concerned.Footnote 104 The CJEU, in the Aranyosi and Căldăraru case,Footnote 105 suggested that the German court might read the Charter of the EU and the ECHR jointly in deciding whether or not the state was complying with an EAW in cases that would potentially lead to the infringement of the human dignity of the person whose extradition was required, due to the prison situation in the requesting states. This exercise would make it unnecessary to activate the identity review based on Article 4.2 TEU because, even without jeopardizing the unity and supremacy of EU law, it might achieve the same goal—prohibition of inhumane or degrading treatment or punishment—as aimed at by the eternity clause of the GG, human dignity. The communication tool for settling the issue at hand, unlike in Hungary but similar to Italy in Taricco, is the preliminary ruling procedure.

Fabbrini and Pollicino ascertain that the Italian CC, prior to its Taricco decision, never used the words constitutional identity as a way to define the relationship between domestic and EU law. Previously, the Italian CC preferred the use of the doctrine of counter-limits, and now, in the most recent Taricco judgment in 2017—Taricco II Footnote 106—it focused more on the concept of constitutional traditions of Member States. In the assessment of scholars, for Italy, the process of European integration represents the perfect fulfilment of the constitution; therefore, it is the common constitutional traditions, and not the individual constitutional identity, that form the source of legal inspiration.Footnote 107 Italy, more clearly than Germany, seems to follow a model of cooperation vis-à-vis EU law and expanded its constitutional identity to include EU membership. Being one of the founders of the EU, Italy could be viewed as the first state to enrich its national, Italian identity with a European identity, identifying with the success of the European integration project—a project based on common interest and legal traditions. The Italian constitutional rules, with which the Italian CC has identified the Italian constitutional system to a certain extent, prevailed alongside the maintenance of the unified EU legal order. The CJEU, in Taricco II, was open to the Italian CC approach and arguments, which led to a judgment that respects identity embedded in constitutional legal traditions. It thus seems that even if neither the CJEU nor the Italian CC has used the term “constitutional identity” to mark the distinctiveness of Italy, or even if nationalistic approaches have not been adopted in Italy,Footnote 108 the result of the Taricco saga has been that one of Italy’s constitutional provisions has prevailed: The understanding of criminal legality in Italy is preserved and respected by the authorities of the EU through an interpretation that also works for the CJEU. Reference to the common constitutional traditions of Member States is used to ease the paradox of the emergence of their identity in a community based on similar legal values and aspirations.

The Hungarian identity review appeared in the 22/2016 (XII.5) decision of the HCC, along with the fundamental rights and ultra vires review,Footnote 109 but has not been activated yet. Nevertheless, the Seventh Amendment of the FL constitutionalized the core content of the decision on the identity of Hungary. The HCC, in 2016, by informally amending the FL, assisted the Fidesz Party in achieving its political agenda and created an ambiguous implicit eternity clause, previously unknown in the constitutional system of Hungary and refuted even by the HCC itself. The HCC, unlike the BVerfG, the Italian CC, or the Polish Constitutional Tribunal,Footnote 110 has mentioned neither the application of the preliminary ruling procedure in resolving the identity-related conflict with EU law nor the legal consequences of such a clash. Nevertheless, it opened up the Hungarian constitutional system to the constitutional review of unconstitutional amendments, which—together with the identity of Hungary— may be a double-edged sword. Furthermore, the language of constitutional identity in Hungary rather shows a tendency towards individualistic detachment from the common European project, which was first characterized by abusive constitutionalismFootnote 111 but has quickly evolved into an illiberal constitutionalism.Footnote 112 This attitude is also present in a dissenting opinion in which the constitutional identity was invoked vis-à-vis a decision of the ECtHR.Footnote 113 The ECHR, however, does not contain a provision similar to Article 4.2 TEU, nor does it use the expression “constitutional identity.”Footnote 114 The ECtHR may agree that some constitutional characteristics do not constitute an infringement of the ECHR,Footnote 115 or it may decide otherwise.Footnote 116 The standard in these cases is not the constitutional identity of the state; the ECtHR does not seek to explore this. Hungary, apparently, takes a different position from Germany and Italy. It may be viewed as a confrontational individualistic detachment from EU law and international human rights obligations.

2. Application Vis-à-Vis Constitutional Amendments

Evidently, the debate over unconstitutional constitutional amendments and the practice of reviewing them did not start with the Lisbon Treaty decisions. But reading eternity clauses as reflecting constitutional identity was triggered by Article 4.2 TEU and appeared in the jurisprudence of the Member States’ constitutional courts, especially in the German one, in the following context: If there are some values entrenched by the constitution which cannot be changed even by the constitution-amending power, consequently, it is not possible to transfer competences to the EU that could potentially violate those very same rules.

Thus, the other legal procedure in which identity has proved to be legally relevant is the review of constitutional amendments. When the identity of the constitution is used in connection with an unconstitutional constitutional amendment, the legal basis is never this term, as it lacks constitutional basis, but instead a specific constitutional provision or an implicit rule which is the result of constitutional interpretation. The will expressed in the constitution-making process embodies the values which the constituent power embraces at a given period and which are rooted in the national identity, or collective identity of the constitutional subject. Changes relating to any alterations of certain values, and thus this national identity, which are embraced by the amending power at a given period, are displayed in the constitutional amendments. The identity of the constitution is thus shaped through debates about itself and its source, in other words, the national identity.Footnote 117

Provided that we accept the dualismFootnote 118 of constitution-making power—original or primary constituent power—and constitution-amending power—derivative or secondary constituent power—the former power may limit the latter by the formulation of eternity clauses or by requiring special procedures for constitutional amendment of certain provisions. The reason is that there is a considerable difference between changes in the national identity that are consistent with the identity of the constitution and changes in the national identity that can potentially destroy it.Footnote 119

This leads us to the question of the review of constitutional amendments. There are constitutional and high courts, to which group the HCC belongs, which do not approve of the substantive review of constitutional amendments. Formal and informal unconstitutional constitutional amendments that infringe upon the eternity clauses or the core content of the constitution, and which lead to an irresolvable conflict with supranational and international obligations, generally seem to occur in Hungary and Poland and have thus far been almost undetectable elsewhere in Europe. Unlike in several Member States, the Hungarian FL explicitly does not entrench anything and does not allow the people to decide on constitutional matters. Also, only the HCC, in its constitutional interpretation, has deduced the definition of the constitutional identity of Hungary without any textual basis. It identified certain principles as comprising the identity of Hungary and did not refer to EU-related procedures or the importance of the involvement of the people in amending processes that may affect that identity. If the collective identity of the constitutional subject is truly articulated in the constitution and shaped by amendments and interpretations, and is legally demarcated by certain constitutional rules, as discussed above, it seems that both the constitutional identity of the people of Hungary, who still support the Fidesz Party and the identity of the FL, do indeed display confrontational individualistic detachment. This detachment apparently has the potential to disregard the common constitutional traditions embedded in regional human rights protection and the European project. The HCC has helped to stock up the FL with unconstitutional rules by declaring them constitutional, and it is now is ready to carve in stone the exact same provisions by collecting them under the heading of “constitutional identity of Hungary,” a notion which the Court itself invented and, by an informal constitutional amendmentFootnote 120—ultra vires interpretation—incorporated into the constitutional text. Now, if the HCC takes itself seriously in the future, it has to revisit its dismissive position on the possibility of the substantive review of constitutional amendments, even in breach of the expressive constitutional rule allowing only procedural review. In this way, the Hungarian constitutional setting, which is not in harmony with the EU and international obligations in every respect,Footnote 121 could be carved in stone according to the actual will of the political decision-maker. And the point of reference, quite contrary to the Italian attitude, may be the identity of the constitution.

The constitutional, legal limitation set by the original constituent power does not prevent a democratic political power, which can and is willing to exercise the constitution-making power, from responding to the potentially altered national identity. It is only prevented from reacting to this change in the existing particular constitutional setting. If and when it is able to adopt a new constitution, however, it can create a new constitutional order that is more reflective of, and more in harmony with, the changed national identity. It will not necessarily be a democratic or liberal constitution, though, which leads us to the problem of whether it is the genuine collective identity of the constitutional subject that is reflected in the new constitution, or, rather, a will manipulated by the populist political regime. The same question arises when dismembermentFootnote 122 is attempted and not responded to, or even supported by, the constitutional court. It happened in Hungary during the transition period, the peculiarity of which was that each and every major political decision intended to introduce the rule of law and democracy was agreed on by the multilateral National Round Table, which did not have any legal power but was legitimized by its participants. This process may be described as a series of simultaneous formal and informal constitutional amendments, which allowed Hungary to become a democracy and rule of law state that could join the EU in 2004, even though it did not adopt a new constitution in the nineties.

As has been said, when a new constitutional order is formed via the creation of a new constitution, it may not necessarily be a democratic constitution that embraces the ideal of the rule of law, democracy, and human rights. This raises the issues of why and how it can happen, whether this constitutional or unconstitutional change or deformation or mutation is legitimate, and whether it is in line with the constitutional identity of the people of the country—Hungary—which can be reconstructed and formed by the constitution and its amendments in the long run. If they are aligned, the question arises of whether the antagonism and estrangement we have seen in the case of Hungary are historically and socio-psychologically predetermined and triggered by populist politicians.

On the contrary, in Germany, eternity clauses form part of the political and legal minimal consensus on constitutional statehood, and in Italy, the fundamental provisions of the constitution are ensured by a creative and cooperative interpretation. Both states experienced extremist dictatorships and adopted their constitutions with a view to strongly marking discontinuity with the previous regime. Due to historical circumstances, in Italy, the monarchy was replaced by a constitutionally entrenched republican form of state; in Germany, human dignity became one of the eternity clauses. Each constitution was, in a sense, formed as an original constitution in the context of the state’s respective constitutional history and was able to create and form a collective identity which determines and influences the actions of the voters and the state authorities, including the courts, in the European legal sphere.Footnote 123 In Hungary, the FL was legally linked to the previous constitution adopted in 1949—and wholly revised in 1989 and 1990—and paradoxically was meant to display discontinuity with the very same former constitution. It established a legal bond with the historical constitution of Hungary, which was in effect until the adoption of the communist constitution of 1949. Thus, the Hungarian constituent, unlike the Italian or the German one, adopted a constitution which is capable of projecting the past into the future, and it got support from the HCC, which associated this past historical constitution with the identity of Hungary. Integration is not unequivocally part of this heritage, but destruction of the old and replacement with a radically new old seems to be. If viewed historically, an essential element of constitutional identity of Hungary or the Hungarians is discontinuity, a lack of agreement as to fundamental achievements and values, and the refusal to follow European norms and accept inclusion.Footnote 124 It can also be argued that a Hungarian constitutional identity, which is similarly committed to the minimum European values and aspirations as is Germany or Italy, could not develop over the course of history, due to debates between decision-making bodies, constitutional interpretation, and the lack of sufficient time. It is not surprising that concurrent interpretations of the past exist following the democratic transition; a new constitutional patriotism did not emerge, and a chaotic mixture of traditions and values can be observed. This controversy may also be problematic as the remembered past becomes social and cultural knowledge and practice, creating an identity. Historiography adjusted to national canons has a different result. Over the course of time, it may lead to a reinterpreted collective identity, as well as to the acceptance of those parts of the past that, for psychological reasons, voters chose to believe,Footnote 125 or refuse, or are unable to reconcile.Footnote 126 These circumstances, along with the actual crises in Europe and their intensification by populist politicians, are apt for populist politics,Footnote 127 who tend to play on emotions and create the current controversies about Hungarian politics and law.Footnote 128

3. Conclusion

The people and the state can differentiate themselves from other states due to the constitutionalization of the individual and unique values and principles exclusively featuring that particular state, which emerged and evolved in the course of constitutional development or constitutional interpretation. This unique identity of its constitution makes it possible for the state to find its different and distinct markers in a community based on common constitutional traditions, values, and principles, and which the given state created or joined by accepting and complying with the set minimum requirements. The national identity, as the collective identity of the constitutional subject, constructed and reconstructed during constitutional development, is shown in the constitution—identity of the constitution—in the guise of, for example, eternity clauses, national language, and history-related provisions., resulting in a unique character for both the constitution and the state itself. If any of the provisions relating to the identity of the constitution are inviolable, it challenges the strong judicial review systems—such as in Hungary—in terms of reconsideration of the existence of unconstitutional constitutional amendments. The reason is that legal consequences should be attached to the application of the legal notion of the identity of the constitution.

Case law throughout the EU indicates that the identity of the constitution, which the EU shall respect, embodies constitutional provisions through which the state can identify itself in a community, as a state with all its attributes, and others that show uniqueness but which can be subsumed within a common European human rights regime and the constitutional traditions of Member States. For this latter category, a joint effort, cooperation, and acceptance are needed from both the CJEU and national courts, which seems to be fulfilled where there is a palpable commitment to the European project. And if this is true, then it seems that the legally relevant identity of the constitution, which may be referred to under Article 4.2 TEU to legally invoke the uniqueness and different nature of the state from the rest of the community and the EU, encompasses only the attributes of the state and popular sovereignty.

IV. Legal Implications of the Identity of the Constitution

For the implementation of the legally applicable identity of the constitution, legal procedures are required; and for avoiding lex imperfecta, legal consequences are needed.

It is necessary to enable dialogue between the CJEU and the national courts which generally seems to be realized. The Decision of 22/2016 (XII. 5) of the HCC, however, due to the lack of institutional and procedural mechanisms, does not enable compliance with this requirement. Despite the commonly detected reluctance of the constitutional courts of the Member States in relation to the use of the preliminary ruling procedure, even the BVerfG turned to the CJEU in 2014, for the first time in its history, regarding the OMT program.Footnote 129 As for the others, the Belgian Constitutional Court used the preliminary ruling procedure for the first time, becoming its most regular user. Other constitutional courts which have already shown themselves to be prepared to engage in a formal constitutional dialogue with the CJEU are those of Austria, Lithuania, Spain, Italy, France, and Slovenia.Footnote 130 The Taricco I and Taricco II cases also underline the importance and legally beneficial nature of the use of the preliminary ruling procedure when the issue at hand involves constitutional identity.