INTRODUCTION

In numerous prior studies, scholars have sought to understand how organizations sustain their hybrid forms (Khavul, Chavez, & Bruton, Reference Khavul, Chavez and Bruton2013; Muñoz & Kibler, Reference Muñoz and Kibler2016). Organizational hybridity refers to the combination of multiple institutional logics and identities that, within an organizational setting, do not conventionally complement one another (Battilana & Dorado, Reference Battilana and Dorado2010; Smith & Besharov, Reference Smith and Besharov2019). In particular, prior research has paid attention to hybrid organizations that are subject to social (e.g., poverty reduction) and economic logics (e.g., profit making) and therefore competing dual identities because such logics are rarely complementary (Arena, Azzone, & Mapelli, Reference Arena, Azzone and Mapelli2018; Doherty, Haugh, & Lyon, Reference Doherty, Haugh and Lyon2014; Moss, Short, Payne, & Lumpkin, Reference Moss, Short, Payne and Lumpkin2011; Parekh & Ashta, Reference Parekh and Ashta2018). Therefore, hybrid organizations are typically the site of contestation, potential conflict, and negotiation over direction and strategy (Battilana & Dorado, Reference Battilana and Dorado2010; Besharov & Smith, Reference Besharov and Smith2014).

Consequently, numerous studies have sought to understand the strategies hybrids adopt to deal with multiple, potentially conflicting logics. As an approach to adaptation, ‘structured flexibility’ balances stable organizational features with novel change processes (Smith & Besharov, Reference Smith and Besharov2019); ‘elastic hybridity’ can be utilised to improve organizational resilience (Gümüsay, Smets, & Morris, Reference Gümüsay, Smets and Morris2020); other strategies include workforce socialization (Battilana & Dorado Reference Battilana and Dorado2010), collaborative cultures (Reay & Hinings, Reference Reay and Hinings2009), and/or blending of logics (Liu, Zhang, & Jing, Reference Liu, Zhang and Jing2016). However, the literature to date is problematic because it implies that the ability to be flexible, elastic, and adaptive to novel change is central to sustaining hybridity and improved performance/survival. This suggests that failed organizations under similar conditions are either unlikely to attempt such adaptation and/or that their failure is a consequence of ill-conceived adaptation strategies. The absence of such an account of failure provides scope for theoretical development into the mechanisms associated with hybridity and organizational failure beyond current perspectives of sustaining hybridity.

To understand processes associated with failure, we focus on the legitimation dilemmas of hybrid organizations. Broadly speaking, legitimacy concerns gaining approval from stakeholders has been shown to be of particular importance for hybrid organizations who have to communicate with and gain acceptance from multiple audiences and resource holders who may have competing expectations (Pache & Santos, Reference Pache and Santos2013; Teasdale, Reference Teasdale2010; Überbacher, Jacobs, & Cornelissen, Reference Überbacher, Jacobs and Cornelissen2015). Thus, successful legitimation strategies for a hybrid entails successfully gaining acceptance from multiple audiences whose expectations may not necessarily be complementary to organizational performance, implying that failure is likely to concern ill-conceived legitimation strategies as an adaptive response. In this article, we adopt a legitimacy-as-process perspective, where legitimation efforts are a constant source of discussion, creation, and negotiation rather than an outcome (Suddaby, Bitektine, & Haack, Reference Suddaby, Bitektine and Haack2017: 24). Adopting this process perspective provides a scope for understanding legitimation strategies that do not sustain organizational hybridity. As such, we ask: In hybrid organizations, how do legitimation processes contribute to organizational failure?

Microfinance Organizations (MFOs) are a notable example of a hybrid. By trying to facilitate loans to the entrepreneurial poor as a poverty reduction initiative (Kimmitt & Dimov, Reference Kimmitt and Dimov2020) a clear social logic exists (Yunus, Reference Yunus1999). However, they also operate within competitive market contexts and are subject to business imperatives and thus simultaneously follow a more traditional banking logic (Kent & Dacin, Reference Kent and Dacin2013; Khavul et al., Reference Khavul, Chavez and Bruton2013). The study of MFOs is dominated by success stories and perseverance in challenging institutional contexts (e.g., Mair & Marti, Reference Mair and Marti2009), with extremely limited accounts of failure (Dorfleitner, Leidl, & Priberny, Reference Dorfleitner, Leidl and Priberny2014). Therefore, the microfinance industry represents a fascinating context for understanding the legitimation efforts of hybrid organizations (Greenwood, Raynard, Kodeih, Micelotta, & Lounsbury, Reference Greenwood, Raynard, Kodeih, Micelotta and Lounsbury2011). We focus on the case of Christian Enterprise Trust of Zambia (CETZAM) in an emerging sub-Saharan Africa context, specifically Zambia. We find that process is marked through three distinct phases (1) dependent coupling, (2) misaligning legitimation, and (3) circumnavigating over conformity. These phases are punctuated through legitimation approaches – coupling and decoupling – in response to emerging logics that challenge the core identity of the organization.

The examination of this issue forms two key theoretical contributions on hybrid organizing, legitimacy, and institutional logics in emerging markets (Barnard, Cuervo-Cazurra, & Manning, Reference Barnard, Cuervo-Cazurra and Manning2017). First, we contribute to theory on hybrid organizing by showing the underlying processes of failure within such an organizational form. Through our theoretical model, we observe the presence of similar strategies identified in the literature that present the importance of flexibility, elasticity, and relational competitiveness and coexistence to sustaining hybridity (Gümüsay et al., Reference Gümüsay, Smets and Morris2020; Liu et al., Reference Liu, Zhang and Jing2016; Smith & Besharov, Reference Smith and Besharov2019) but, in the long-term, these may have deleterious unintended consequences by over-conforming with the expectations of key stakeholders (investors), ultimately eroding the identity of the organization and its ability to function effectively (McPherson & Sauder, Reference McPherson and Sauder2013). The process eliciting failure cannot be separated from decisions taken in more stable times, where hybridity is seemingly being sustained, alongside those decisions taken in more challenging crisis moments. In summary, our research implies that a failure to sustain hybridity is not simply the reverse of succeeding to. In doing so, we respond to Smith and Besharov's (Reference Smith and Besharov2019) call for further research to look at how hybridity operates when it is not necessarily a proactive choice but in a context of intensive stakeholder demands (i.e., regulators/investors/donors in this study).

Second, by utilising ideas underpinning legitimacy theory (Lounsbury & Glynn, Reference Lounsbury and Glynn2001), we contribute to the venture development legitimacy perspective (Überbacher, Reference Überbacher2014) which has drawn from the concepts of ‘coupling’ and ‘decoupling’ to understand how organizations align themselves with their environment (i.e., logics) and/or strategically detach through symbolic compliance (Überbacher et al., Reference Überbacher, Jacobs and Cornelissen2015). Although decoupling is considered an appropriate response to institutional complexity, when such strategies become too distant from the hybrid's core identity it may have deleterious consequences, contributing to Greenwood et al.'s (2011) call for greater understanding of the ‘unwitting consequences’ (350) of decoupling. Therefore, by using our legitimacy-as-process perspective, we can highlight an alternative role of coupling and de-coupling strategies. Rather than an approach to dyadically ‘fit’ with an audience to mobilize resources, they are part of a larger emergent set of activities that occur at multiple levels and with potentially deleterious outcomes.

THEORETICAL BACKGROUND

Organizational Hybridity

Organizational hybridity refers to the combination of multiple institutional logics and identities that, within an organizational setting, conventionally do not go together (Battilana & Dorado, Reference Battilana and Dorado2010; Smith & Besharov, Reference Smith and Besharov2019). Whilst some prior research has discussed hybridity at individual (McPherson & Sauder, Reference McPherson and Sauder2013) and field level emergence (Greenwood et al., Reference Greenwood, Raynard, Kodeih, Micelotta and Lounsbury2011; Skelcher & Smith, Reference Skelcher and Smith2015), most research in this space focuses on how organizations combine such logics and identities to function more effectively and succeed (Battilana & Lee, Reference Battilana and Lee2014; Moss et al., Reference Moss, Short, Payne and Lumpkin2011). Such strong identities arise when there is both a salient and a clear organizational mission, followed by alignment within its membership through symbols, images, and narratives (Hatch & Schultz, Reference Hatch and Schultz2002). But these are challenged when organizations combine – either strategically and/or through environmental constraints – multiple logics and identities. In the former, organizations can pursue their own hybridity related strategies because it can provide access to new markets and also be a source of legitimacy, and competitive advantage (Muñoz & Kimmitt, Reference Muñoz and Kimmitt2019). In the latter, organizations can be forced into hybridity through environmental changes such as through new regulatory discourse (Siwale & Kimmitt, Reference Siwale and Kimmitt2019).

When faced with perceived constraints, organizations employ different strategies to respond to emergent logics and their demands (Greenwood et al., Reference Greenwood, Raynard, Kodeih, Micelotta and Lounsbury2011; Gümüsay et al., Reference Gümüsay, Smets and Morris2020; Lawrence, Reference Lawrence1999; Oliver, Reference Oliver1991). Organizations can be subject to the imposition of new logics from actors such as regulators or other dominant field members (DiMaggio & Powell, Reference DiMaggio and Powell1983). This context is what Besharov and Smith (Reference Besharov and Smith2014) describe as ‘contested organizations’ which exist when multiple external demands are placed on an organization, making the prescribed roles and actions for organizational members opaque. Consequently, successful hybrid organizing has been shown to be a crucial response to new logic emergence that challenges organizational identity. For example, Reay and Hinings (Reference Reay and Hinings2009) discuss the importance of collaborative relationships as a strategic imperative for hybrids in a healthcare context.

However, although the literature on organizational hybridity has looked at how the various tensions and contradictions of hybrids become resolved, leading to enhanced performance and/or survival (Battilana & Dorado, Reference Battilana and Dorado2010; Liu et al., Reference Liu, Zhang and Jing2016; Reay & Hinings, Reference Reay and Hinings2009), very little is known about the relationship between hybridity and failure. Smith and Besharov (Reference Smith and Besharov2019) discuss ‘structured flexibility’ as a process involving ongoing adaptation to meanings and practices which also requires stable organizational features; Gümüsay et al. (Reference Gümüsay, Smets and Morris2020) describe a similar hybrid ‘elasticity’ that allows the organization to succeed and thrive. Although these may be important mechanisms to promote the successful functioning of an organization, they also imply that the behaviour of failed organizations may be unstructured, inelastic and that their failure is a consequence of ill-conceived adaptation strategies.

The aforementioned discussion highlights two central issues currently existing within the literature. First, prior research has focused on how hybrid organizations are sustained to be able to perform more effectively and survive. This opens up the question about the process that leads to the break down and failure of hybrid organizations which may be of particular issue when we shift our focus from ‘hypermuscular’ actors in the hybridity literature (Martin, Currie, Weaver, Finn, & McDonald, Reference Martin, Currie, Weaver, Finn and McDonald2017). Second, and thus relatedly, prior research depicts a relatively static story of these ‘contested’ hybrids, assuming that once they adopt hybrid strategies they either perform well or instantaneously fail, which is an oversimplificaton of the process that exists between the development of a hybrid strategy and eventual failure. Prior research is dominant in the former yet very little is know about the sets of strategic decisions made to elicit the latter. This provides an opportunity for theoretical development.

Legitimation Strategies of Hybrid Organizations

One such strategy for hybrid organizations is the desire to legitimize with potentially new stakeholders in the emergent institutional conditions (Überbacher, Reference Überbacher2014). In general terms, achieving legitimacy means gaining approval from stakeholders (Lounsbury & Glynn, Reference Lounsbury and Glynn2001) in terms of ‘desirable, correct or appropriate actions…. within some socially constructed systems of norms, values, beliefs and definitions’ (Suchman, Reference Suchman1995: 574). Like hybridity research, the concept of legitimacy has focused on how organizations comply with stakeholder demands in their environment as well as break away from them; this is argued to occur through interactions between internal and external parties (Drori & Honig, Reference Drori and Honig2013). Subsequently, one of the main premises in legitimacy research is that the growth and survival of organizations depends on effective strategies (Garud, Schildt, & Lant, Reference Garud, Schildt and Lant2014; O'Neil & Ucbasaran, Reference O'Neil and Ucbasaran2016).

Drawing from the legitimacy concept, research has shown different types of practices that organizations use to convince audiences about their venture's ‘worthiness’ and ability to survive and grow effectively in a given institutional context (Tracey, Phillips, & Jarvis, Reference Tracey, Phillips and Jarvis2011). Here, organizations attempt to shape the perceptions of key stakeholders to receive support for the organization to survive and prosper (Tracey, Dalpiaz, & Phillips, Reference Tracey, Dalpiaz and Phillips2018; Wry, Lounsbury, & Glynn, Reference Wry, Lounsbury and Glynn2011). When confronted with competing stakeholder demands, organizations typically conform to institutional demands to maintain their legitimacy and survival (Amankwah-Amoah & Debrah, Reference Amankwah-Amoah and Debrah2017; DiMaggio & Powell, Reference DiMaggio and Powell1983; Hamilton, Reference Hamilton2006; Liu et al., Reference Liu, Zhang and Jing2016). Thus, to be able to legitimize their organizations and survive, a large body of research has highlighted how firms adapt to fit in with their external environments through isomorphic (DiMaggio & Powell, Reference DiMaggio and Powell1983) or coercive pressures (e.g., regulatory discourse) (Siwale & Kimmitt, Reference Siwale and Kimmitt2019). They must also develop internal support for any new strategic initiatives and adapt the organization accordingly (Battilana & Dorado, Reference Battilana and Dorado2010; Drori & Honig, Reference Drori and Honig2013).

Prior research demonstrates the legitimation strategies firms adopt when they need to adapt to more than one environment. Überbacher et al. (Reference Überbacher, Jacobs and Cornelissen2015) discuss ‘symbolic decoupling’ as a strategy firms adopt when they gradually want to loosen their ties to a particular stakeholder audience with distinct logics; this may involve ceremonial symbolism to retain ties but ultimately the organization is striving to be autonomous and break away from the constraints of particular audience demands. The concept of decoupling has been demonstrated elsewhere, emphasising how organizations may engage in actions that show compliance with new logics whilst being non-conforming (Fiss & Zajac, Reference Fiss and Zajac2004). Whilst ‘coupling’ involves alignment with an organization's external environment, with decoupling, hybrids tend to endorse actions prescribed by one logic, yet they implement approaches promoted by another; the latter is typically aligned with the organization's core aims (Pache & Santos, Reference Pache and Santos2013).

This balance between these internal (e.g., the workforce, senior management, board of directors) and external (e.g., investors, regulators, key suppliers, customers) aspects of the organization align with the strategic approaches of ‘structured flexibility’ and hybrid ‘elasticity’ outlined previously in hybridity research (Gümüsay et al., Reference Gümüsay, Smets and Morris2020; Smith & Besharov, Reference Smith and Besharov2019). This attests to the view of ‘legitimacy-as-process’ where legitimacy ‘is the product of an ongoing process of social negotiation involving multiple participants, rather than an outcome’ (Suddaby et al., Reference Suddaby, Bitektine and Haack2017: 24). This is somewhat different to viewing it as ‘property’ or ‘perception’, where legitimacy is either a resource and an asset or an individual level micro-perception (Suddaby et al., Reference Suddaby, Bitektine and Haack2017: 24).

In a process view, legitimacy is the result of a series of interactions and is seen as being in a constant state of ‘flux’. For example, such a temporal view has shown how legitimacy can become socially constructed within a place in the new venture creation process (Kibler, Fink, Lang, & Muñoz, Reference Kibler, Fink, Lang and Muñoz2015) or strategically built through networks that may sustain organizations or lead to their demise (Human & Provan, Reference Human and Provan2000). As Suddaby et al. (Reference Suddaby, Bitektine and Haack2017) highlight though, the process approach is particularly useful for understanding counter views of legitimacy where the study of failure can be a ‘departing point’ from other legitimation mechanisms. For example, prior research has detailed that when ‘deinstitutionalization’ occurs certain practices become illegitimate, it happens through a process of continuing disruptive and defensive institutional work by key actors (Maguire & Hardy, Reference Maguire and Hardy2009); via a ‘spiral’ process effect between the institutional field public opinion and industry insiders (Clemente & Roulet, Reference Clemente and Roulet2015); or when custodian organizations deploy resistance tactics (Cannon & Donnelly-Cox, Reference Cannon and Donnelly-Cox2015).

Thus, legitimacy is seen as legitimation efforts which are a constant source of discussion, creation, and negotiation. By adopting this view of legitimation, we prise open the possibility that the negotiation of multiple participants may not necessarily conclude with the achievement of a positive legitimacy outcome (François & Philippart, Reference François and Philippart2019). Prior research has typically identified a clear link between sustaining the organizational effectiveness of hybrid organizations, the legitimation processes and approval seeking they pursue (Pache & Santos, Reference Pache and Santos2013; Skelcher & Smith, Reference Skelcher and Smith2015). To the extent that hybrids, which are difficult to categorize by key stakeholders, tend to suffer (Brandsen & Karré Reference Brandsen and Karré2011; Doherty et al., Reference Doherty, Haugh and Lyon2014) whilst those that successfully communicate their hybridity tend to be more competitive and functional (Muñoz & Kimmitt, 2019; Pache & Santos, Reference Pache and Santos2013; Smith & Besharov, Reference Smith and Besharov2019). In this respect, through a legitimacy-as-process perspective (Suddaby et al., Reference Suddaby, Bitektine and Haack2017), the legitimation efforts of hybrids are an ongoing adaptive work in progress and are inherently relational in terms of internal and external organizational demands (Girschik, Reference Girschik2020). Our perspective suggests that whilst hybrid organizations may develop legitimation strategies, these may be ill conceived and not necessarily conclude with the success and survival that most literature focuses on.

In summary, given the dominance within the literature regarding strategies and approaches to sustain and maintain (i.e., succeed) hybridity through legitimation, this raises an important question as to whether the failure of hybrid organizations is simply the neglect to adopt such approaches or whether this is the result of such ill-conceived strategies. Thus, in this article, we ask: In hybrid organizations, how do legitimation processes contribute to organizational failure? Here, survival (or failure) may depend on how organizations ‘couple’ or ‘decouple’ their behaviours with audience expectations whilst adapting internal dynamics to suit new strategic aims. By taking a legitimacy-as-process view, our focus on a failing organization allows us to understand the processes associated with gradual de-legitimising (i.e., failing), hitherto unaddressed.

RESEARCH SETTING: MICROFINANCE INDUSTRY IN ZAMBIA

Microfinance Organizations (MFOs) have emerged as an important example of a hybrid organization in a field that is subject to multiple logics (Battilana & Dorado, Reference Battilana and Dorado2010; Khavul et al., Reference Khavul, Chavez and Bruton2013). On the one hand, the purpose of MFOs in this organizational field is for MFOs to faciliate social objectives of integrating entrepreneurs into the financial system and empowering their movement out of poverty (Mair & Marti, Reference Mair and Marti2006; Parekh & Ashta, Reference Parekh and Ashta2018; Zahra, Gedajlovic, Neubaum, & Shulman, Reference Zahra, Gedajlovic, Neubaum and Shulman2009). To enact this ‘development logic’, MFOs facilitate access to small amounts of credit to invidividuals who have traditionally been unable to access the formal banking sector (Yunus, Reference Yunus1999). This has been associated with improved personal finances or other poverty measures, constituting the development logic of MFOs in this field (Copestake, Bhalotra, & Johnson, Reference Copestake, Bhalotra and Johnson2001; Ganle, Afriyie, & Segbefia, Reference Ganle, Afriyie and Segbefia2015; You & Annim, Reference You and Annim2014).

MFOs thus offer micro-credit to borrowers with the expectation that they will repay loans with interest and within an agreed period of time. In doing this, MFOs are also subject to a ‘banking logic’ which conveys a need to meet their economic needs by covering operating expenses, loan losses as well as the expansion of their capital base ultimately funding future growth (Morduch, Reference Morduch1999). This trend of commercialisation is now common in the industry. More recent research has identified the organizational tensions that exist when MFOs look to integrate profit-driven and poverty reduction ideals (Parekh & Ashta, Reference Parekh and Ashta2018). As such, the development logic co-exists with a more utilitaristic, economic banking logic which shapes organizational strategy. For many MFOs, they use business skills and market based approaches of revenue maximization and cost reduction to address their development objectives in a way that is assumed to be more financially sustainable (Battilana & Dorado, Reference Battilana and Dorado2010; Nicholls, Reference Nicholls2010; Zahra et al., Reference Zahra, Gedajlovic, Neubaum and Shulman2009). However, the term ‘mission drift’ is often used in this literature to depict the tension between profit-driven commercial logics and poverty reduction development ideal (Copestake, Reference Copestake2007). Thus, MFOs represent interesting examples of organizations that have embraced their hybridity by dealing with mutliple, often conflicting logics.

In Zambia, the geographical context of this study, microfinance development is not as notable as in East Africa by any measures. According to FinScope (2015), financial exclusion, particularly of rural populations is still very high. Access to suitable finance by the low income and excluded rural population through sustainable microfinance is important to the broader goal of addressing mass poverty. Microfinance in Zambia has provided low-income individuals with access to financial services, thereby addressing and supporting government efforts to ensure financial inclusion and encourage bottom-up local economic development.

Yet twenty years later, the industry can be described as young and still playing a relatively small role in serving micro and medium businesses in Zambia. A rough estimate of client outreach by the Association of Microfinance Institutions of Zambia (AMIZ) puts it at less than 1 million as of 2016 (AMIZ official, July 2016). Zambia has lagged behind countries in East Africa not only in outreach numbers but also in enacting a regulatory framework for microfinance institutions (Brouwers, Chongo, Millinga, & Fraser, Reference Brouwers, Chongo, Millinga and Fraser.2014). Consequently, responsible growth and deepening financial services to Zambians was being impeded by a lack of effective legal and supervisory mechanism for MFOs (Chiumya, Reference Chiumya2006). For instance, although MFOs were committed to serving the poor, this was not performed in an efficient, transparent, and sustainable manner. Monitoring of MFOs by investors to ensure institutional soundness was insufficient and disclosure to clients was either erratic or non-existent. Given that MFOs served one of the most vulnerable segments of the population, it was expected that these provisions would promote sustainable growth, expand outreach, and safeguard clients from the possibility of exploitation and abuse (Bank of Zambia Official, 2015). Broadly speaking, the continued reliance on donor or government funds is seen as both detrimental and unrealistic. Specifically, there has been a move toward sustainable, market-based microfinance by undertaking necessary regulatory reforms and enhancing business environmental conditions.

The trend in developing countries is an increasing number of MFOs changing from charities to profit-seeking business and adopting the status of regulated commercial financial institutions (Brouwers et al., Reference Brouwers, Chongo, Millinga and Fraser.2014; Epstein & Yuthas, Reference Epstein and Yuthas2010). To support this change, in 2006, Bank of Zambia (BOZ) introduced the Banking and Financial services (Microfinance) Regulations 2016 Act that provided a regulatory framework through which credit only MFOs could evolve into limited companies with identifiable shareholders. The Act also paved the way for the formation or transformation of credit only MFOs into Tier I deposit taking MFOs. This institutional transformation process saw some of the large developmental MFOs embark on mobilization of voluntary savings. With the introduction of Microfinance Regulations, BOZ intended to bring MFOs under its regulatory sphere, and more importantly provide a smooth integration of the sector into the mainstream financial sector (Brouwers et al., Reference Brouwers, Chongo, Millinga and Fraser.2014; Siwale & Okoye, Reference Siwale and Okoye2017). Interesting to note, though, is the relatively free entry to the industry that came with the 2006 Act. The sector was soon to include several salary-based lenders, also categorised as MFOs.[Footnote 1] Around 90 percent of the microfinance sector's portfolio is managed by consumption lending MFOs, which are based mainly in the big cities of Lusaka and the Copperbelt (Bank of Zambia, 2014; Brouwers et al., Reference Brouwers, Chongo, Millinga and Fraser.2014). As of 2018, there were 34 MFOs licensed by the Bank of Zambia, of which 10 are deposit taking made up of four enterprise and six consumer-payroll lending MFOs (BOZ Annual Report, 2018).

METHODS

Data Collection

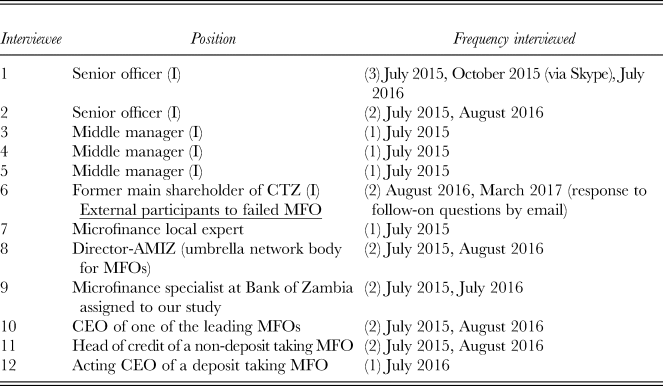

CETZAM Financial Services PLC, originally under the name Christian Enterprise Trust of Zambia was created in 1995. It was one of Zambia's best-known microfinance institutions due to its strong social mission, rural presence and by targeting the poor, especially women. CETZAM makes an interesting case study because of its successful transformation from an NGO MFO into a for-profit MFO (hybrid organization) in 2006, then deposit taking in 2010 before its collapse in May 2016. First and foremost, we focused on collecting interview data. This took place in July 2015 while CETZAM was still operational but in deep crisis. The second stage of fieldwork took place in July/August 2016; two months after the regulator – Bank of Zambia – had taken possession of CETZAM. The intention was to find out how the leading stakeholders then accounted for its failure. Therefore, over the period (July 2015–August 2016), we conducted 20 in-depth semi-structured interviews with 12 individuals. As eliciting an expert perspective of failure was important, 11 of these research participants in Table 1 had been involved with the MFO or the sector for over 10 years, and all could relate to both the field's complex set of logics and dynamics. In addition, all senior managers had been actively involved in managing CETZAM up to the year it collapsed. Out of 12 interviewees, seven were interviewed at least twice (see Table 1). Because it was important to get a bigger picture of the state of the local microfinance sector, interviewees 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, and 12, were external to CETZAM. It was particularly important to elicit the ‘multiplicities’ of the failure situation following Mellahi and Wilkinson's (Reference Mellahi and Wilkinson2004) guidance, to take care not to obscure any emerging differences between how leading stakeholders later accounted for it, although some resisted doing so.

Table 1. Research Participants

Note: (I) denotes an internal participant drawn from CETZAM

Questions with informants from CETZAM normally started with their general impression and observation of the institution's niche in extending financial services to microenterprises and the poor, then proceeded to identify the most important events they believed accounted for its failure. As previously outlined, we adopt a ‘legitimacy-as-process’ perspective (Suddaby et al., Reference Suddaby, Bitektine and Haack2017) which brings a broad view to our attention where legitimation is viewed as an interaction between multiple organizations and individuals. Thus, our data collection did not imply that the organization had achieved legitimacy with various stakeholders but that their strategies and decision-making reflected efforts to do so. Interviews with external informants started with what they thought about the regulatory environment, interest rate caps and how it had affected the sector or performance of their MFOs. In reflecting on capping of interest rates and its effect, the discussion would then naturally lead into CETZAM's fate. Typically, interviews lasted between forty-five minutes and two hours, mainly conducted face-to-face and audio-recorded, unless the interviewer objected to audio recording. All but two interviewees were recorded and subsequently transcribed after the researcher completed the fieldwork.

Second, we focused on the construction of a timeline from the events described by respondents and informant validation. We developed a detailed narrative, and utilised data collected at different points in the organization's life, with a particular focus on ‘critical events’ within the timeline of the process – those instances that are salient, important or essential and require unusual attention from which inferences can be made (Morgeson, Mitchell, & Liu, Reference Morgeson, Mitchell and Liu2015). By focusing on these clearly observable events, we balance the necessary time ordering of such events against the notion that certain events and their outcomes are subjectively attributed as meaningful and relevant to organizational actors in a multitude of ways (Suddaby, Reference Suddaby2010) e.g., a firm attributing performance to external conditions rather than their own managerial issues. At this point in the process, secondary data were particularly critical in reconstructing and discussing historical events thus reducing bias. Secondary sources such as newspapers, Bank of Zambia's annual reports on the sector's performance and CETZAM's 2013 annual report were examined to aid the analysis. This diversity of data from various sources allowed triangulation of our explanation and facilitated a deeper understanding of the organizational setting.

Data Analysis

In terms of analysis, we focused on the identification of emergent themes through abductive data analysis (Gioia, Corley, & Hamilton, Reference Gioia, Corley and Hamilton2013; Tavory & Timmermans, Reference Tavory and Timmermans2014). Abductive analysis involves iterating between data and extant theory in order to theorize about the case organization and explain key patterns and events. The abductive analysis process involves the interplay between grounded inductive (data) insights and deductive theoretical ideas (e.g., Muñoz & Kimmitt, Reference Muñoz and Kimmitt2019). This approach is particularly important when attempting to understand emerging constructs or relationships such as the interplay between hybrid organizations, legitimation and failure in this article (Timmermans & Tavory, Reference Timmermans and Tavory2012).

In the first part of this analytical process, we focused on the transcribed narratives and key events in order to identify the most relevant events for the timeline (Miles & Huberman, Reference Miles and Huberman1994). In order to make sense of this process story, we adopted a temporal bracketing strategy to our analysis (Langley, Reference Langley1999). As such, we were able to identify key periods in the process of failure related to logic emergence and decision-making i.e., notable changes in organizing principles, informal rules of action and interaction that guide this field (Thornton & Ocasio, Reference Thornton and Ocasio1999). This involved identifying critical sources of progression within the timelines where the process seemed to be entering a new phase of development (Langley et al., Reference Langley, Smallman, Tsoukas and Van de Ven2013). This temporal decompisition was identified when obvious changes became apparent in logics that the organization was responding to e.g. the shift to commercialise the MFO sector through new legislation with a clear banking logic embedded within it.

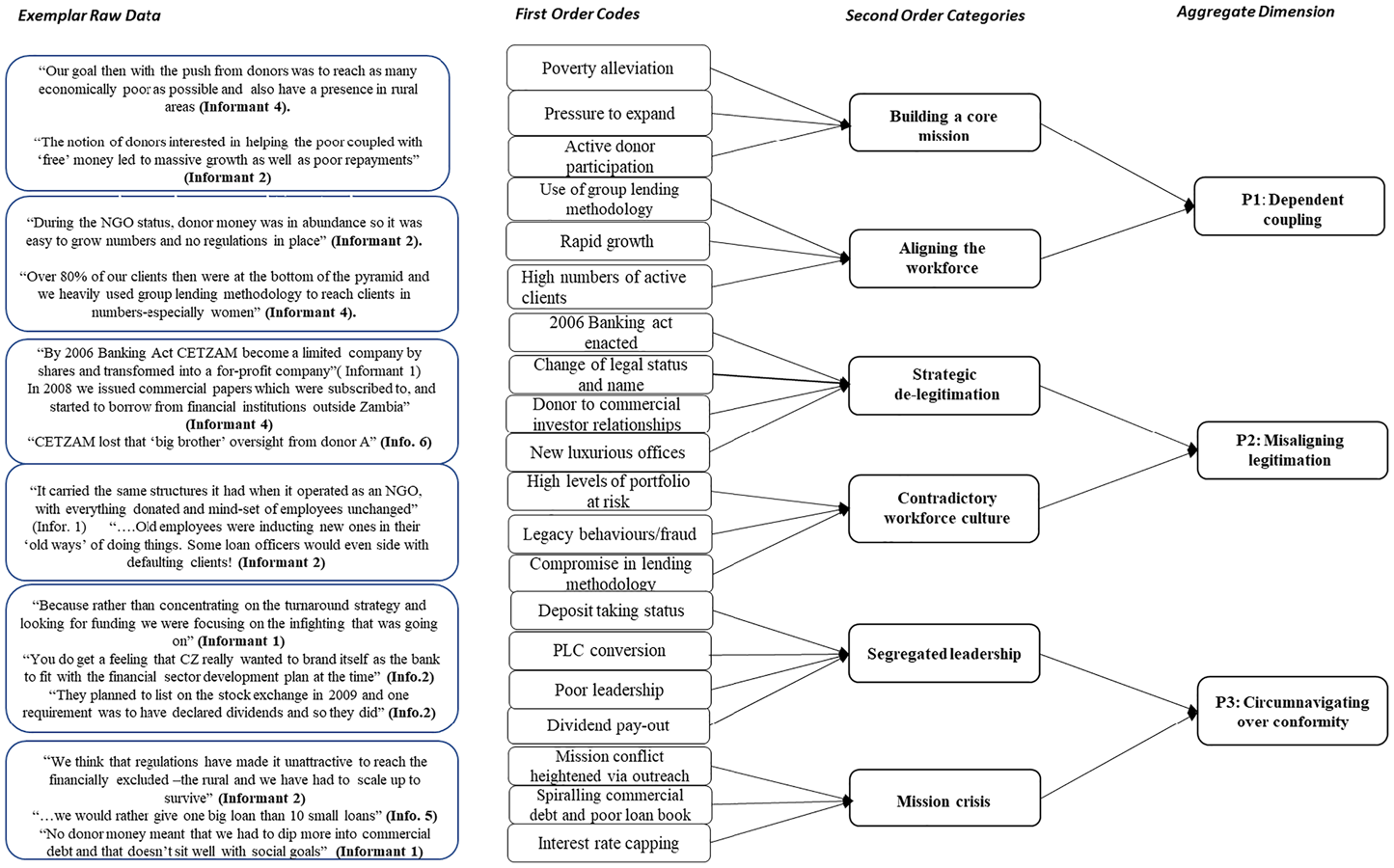

We were then able to focus on understanding the key legitimations strategies that related to the emerging hybridity. Such a temporal decompisition improves the robustness of process theorising by improving the accuracy of interpretation (Langley, Reference Langley1999). Simultaneously, this first part of the analytical process was to identify salient emerging themes within these temporal brackets in an inductive manner. The second part of this type of abductive analysis involved moving between our inductive insights and extant theory. In particular, we utilised Besharov and Smith's (Reference Besharov and Smith2014) notion of logic compatibility and centrality to understand where and when the environment was becoming more institutionally complex, how it was having an impact on the MFO (internally) and the subsequent legitimation strategies (externally-oriented) required in response. Compatibility draws our attention to how the direction of the hybrid is being accepted internally, whilst centrality draws our attention to externally oriented mission and strategy decisions that have resource and reputational implications. This structure is reflected in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Data structure

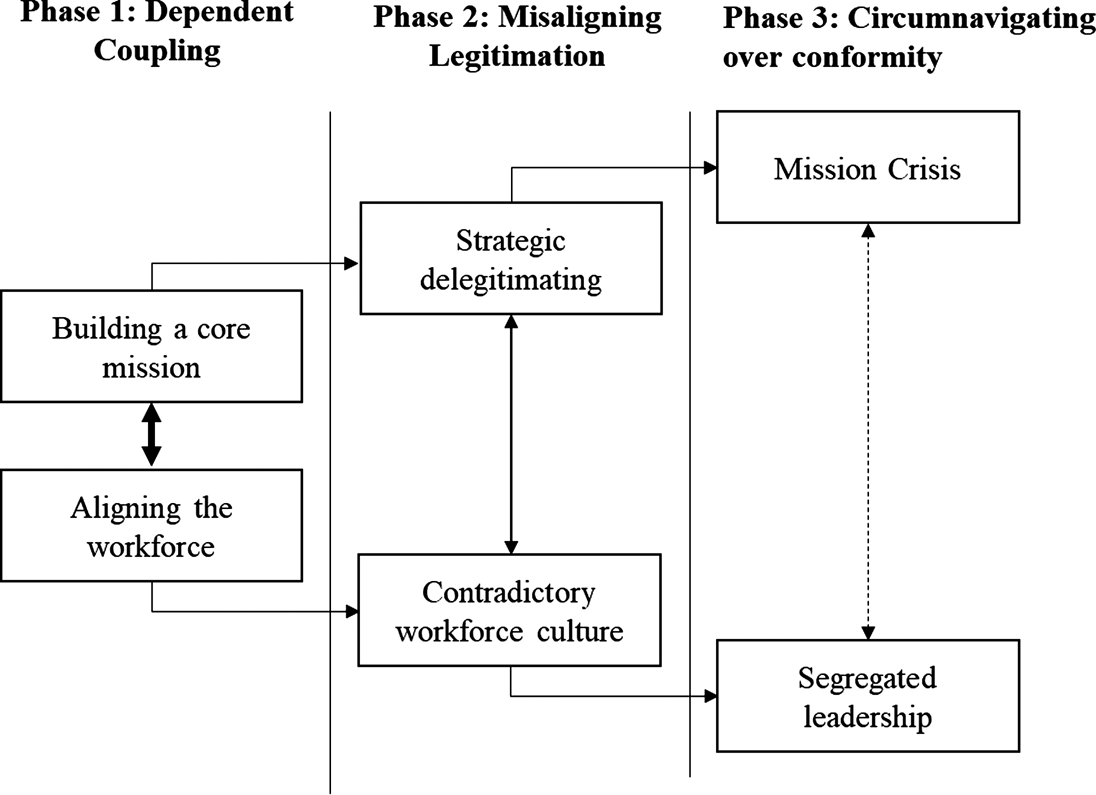

The literature on hybridity, legitimacy and microfinance was used to guide the stepwise abductive analysis that can be found in Table 2, highlighting the inductive and subsequent deductive development across existing theory (Gioia et al., Reference Gioia, Corley and Hamilton2013) i.e., reflecting on and making decisions regarding our coding structure through this existing literature. Given the temporal bracketing strategy in the research, we were then able to represent our data structure through a process model which depicts the three phases identified in hybrid organizing failure. Figure 2 represents the internal and external aspects previously discussed which appear tightly coupled at the beginning and gradually pull further apart through organizational decline.

Table 2. Abductive analysis

Figure 2. Process model of hybrid organization's failure

RESULTS

Based on the analysis, we deduce three unique phases, which capture events, action and processes leading to the failure of the organization. In this findings section, we present the story of MFO failure and present each phase by showcasing codes associated with the strategic legitimation responses to emergent logics. As previously articulated, the results follow the structure of the interplay between internal and external aspects of the organization as they try to sustain and develop their new hybrid form. As depicted in Figure 2, the three phases highlight initial tight ‘coupling’ when the organization is in relatively harmonious times and internally coherent. The model depicts how these internal and external elements get pulled apart through ill-conceived legitimation strategies.

Phase 1: Dependent Coupling

In the first phase, we highlight what we label as dependent coupling which showcases the alignment between the internal values of the organization and how these were ‘coupled’ with the expectations of other key stakeholders, something which ultimately elicited a dependency upon those field-level stakeholders. Whilst the term ‘coupling’ refers to the degree of alignment with a targeted environment (Überbacher et al., Reference Überbacher, Jacobs and Cornelissen2015), we identify how this coupling produced a dependency on stakeholders within that environment. This ‘coupling’ of building a core mission and aligning the workforce aimed to legitimise the MFO in its initial years as they worked towards the stakeholders’ (donors) and organization's core mission of poverty alleviation. In Figure 2, the thick arrow depicts this coupling as producing relative organizational harmony with internal and externally oriented features being synchronized.

Building a core mission. At the founding of the organization, the logic of development and poverty reduction was the focus of the microfinance industry, guiding the legitimation practices of the MFO around its core mission. At this stage, the tensions that come with hybridity were non-existent as the MFO was mainly guided by this social need to reduce poverty through microfinance services. When it was founded it had an expressly strong vision to fulfil a social agenda driven by Christian principles to transform the lives of the poor by providing opportunities to create employment and generate income through credit and training services (Dixon, Ritchie, & Siwale, Reference Dixon, Ritchie and Siwale2007). This reflected the values of its founder members who sought to use the Christian biblical framework to shape a threefold (economic, social, and spiritual) transformational development. Talking to one of the founder members in 2016 and in a follow-up email in February 2017, it was pointed out that:

We really started as a private enterprise with corporate ideals embracing social concerns that would be transformative. I, and some other people invested personal money before donors came on board. Our vision was to serve poor communities by providing access to credit to finance and grow their microenterprise…. [but] CETZAM was not a donor agenda at all, but that its social focus appealed to donors who were ready to partner and give financial support to drive the poverty agenda. (Informant 6)

The original founders had poverty alleviation as their main goal, which conformed to development oriented international organisations like the Department for International Development, UK, and led to CETZAM transforming into a non-government organisation (NGO). This clear social mission was key in the legitimation attempts by CETZAM to these active stakeholders (donors), who at the time defined and shaped the local and international microfinance industry. To stay true to its internal ideals of meeting the needs of micro-entrepreneurs at the base of the pyramid, the traditional group-based lending methodology was deemed appropriate for rapid outreach to low-income entrepreneurs. Thus, building a core mission refers to how the MFO communicated itself to these external stakeholders to gain their acceptance.

In 1998, the UK's Department for International Development, in partnership with international organization ‘A’ (anonymised), released funds through ‘A’ to manage CETZAM and the supporting donor had even earmarked it for massive growth to serve as a model for a registered national bank by 2005 (Dixon, Ritchie, & Siwale, Reference Dixon, Ritchie and Siwale2006). As an MFO with NGO status and backed by abundant donor funds, its legitimacy and authenticity were ‘given’ and became a platform for its rapid growth. For example, Dixon et al. (Reference Dixon, Ritchie and Siwale2007) note that, its branch network had grown to 12 in less than five years and by end of 2002, it could boast over 16,000 active clients, up from 9,390 in 2000. By local standards, CETZAM was regarded a market leader and enjoyed great success as measured by client numbers, branch networks and impressive repayment rates (Copestake, Reference Copestake2002). It is here that the development logic of poverty reduction is at its most apparent and largely uncontested in the institutional field. This is reflected in CETZAM's legitimation practices, through their core mission and growth strategy.

Aligning the workforce. In response, the organisation's funders, the institution together with loan officers focused on massive outreach in terms of the poor accessing loans. Whilst building a core mission refers to how the MFO communicated its core vision to donors, aligning the workforce refers to how that external donor relationship shaped the activities of members of the MFO. For CETZAM to operationalise its core mission, field level employees (loan officers), managers as well as donors’ actions were all aligned to this logic of poverty reduction. This was consistent with the bigger goal of fighting poverty and not so much with institutional financial sustainability. But, within CETZAM, there was pressure to expand their operations to satisfy the expectations of donors and therefore ensure that future access to funds could be secured. Thus, organisational practices developed internally to meet the needs and desires of donor funding as a means to securing CETZAM's financial future. To achieve that, one informant in hindsight noted that:

Group lending then, for CETZAM as an NGO contributed 80% to the loan portfolio size. This lending methodology was intended to target the poorest of the economically active-mainly women as per donor preference then of supporting women rather than men in fighting poverty through microenterprises. So, loan officers mainly followed women marketeers to facilitate microloans and meet agreed client targets. (Informant 4)

Another added:

Internally the organisation set targets for its loan officers that focused on repayment performance, a key variable for donors that were funding us at the time. (Informant 1)

Given the relationship between CETZAM and funders, this demonstrates how it shaped the day-to-day role of organizational members. Donors funding CETZAM pushed loan officers to focus on loan repayment, as opposed to a more tailored personal relationship that involves officers providing additional support to low-income entrepreneurs. This was also entirely focused on female entrepreneurs rather than a broader range of individuals experiencing income poverty.

This influential donor role appears to be because of CETZAM's financial dependence on donor funding, as articulated below:

So CETZAM's performance as an NGO had been fluctuating and each time the company went down, it was because of a poor loan book. When the loan book got bad, we would receive funding from donors and go back up again and even forget about the bad loans we had not collected. Therefore, it became a cycle; go down on account of bad loans, get donor funding and get back up again! This is how it was when it operated as an NGO. (Informant 2)

This ‘cycle’ is encapsulated in our code aligning the workforce which implies that donors had a powerful influence over decision-making within the MFO, shaping the practices of loan officers who were simultaneously focused on massive outreach and reducing the risk of the portfolio by increasing repayment rates. This cycle was then complete when donors continued to fund the organization despite poor financial performance, insisting on a further set of conditions for this finance. Thus, the influence of donors, to whom legitimacy was important for the MFO, was to align their needs with the activities of the workforce (loan officers, branch managers, senior management).

Thus, we label the first phase of the process as dependent coupling. Through building a core mission the MFO communicated the values and intentions of the organizations to key stakeholders (donors). But through aligning the workforce, we see how that particular external relationship shaped some key organizational activities. Whilst ‘coupling’ is a relevant strategy for gaining acceptance from such key stakeholders, the extent to which these stakeholders had an impact on organizational life engendered a dependency. This points to an old ‘world order’ (Fowler, Reference Fowler2000) within international development which had a principal focus on beneficiaries, poverty reduction and the role of donor partners (Venkataraman, Vermeulen, Raaijmakers, & Mair, Reference Venkataraman, Vermeulen, Raaijmakers and Mair2016). This was consistent with the strategic decision-making of the MFO at that time as they responded by rapid scaling that defied natural ‘organic’ growth supported by internal controls. Consequently, the workforce (loan officers and branch managers) were tasked with increasing outreach to as many entrepreneurs as possible under the premise that improving access to financial services was critical to poverty reduction, irrespective of the outcome. Ultimately, the coupling associated with their legitimation engendered a dependency on those donors for whom they financially relied.

Phase 2: Misaligning Legitimation

In the second phase, we highlight what we label as misaligning legitimation which comprises of strategic de-legitimation and a contradictory workforce culture. Where new logics have now emerged within the field, this phase emphasises how the MFO ‘decoupled’ themselves from previously crucial donor relationships to align itself with the behaviour of for-profit entities like commercial banks under the new banking logic (strategic de-legitimation), ultimately undermining their ability to function effectively. The ‘misalignment’ occurs through the de-legitimation of previously vital relationships and focus on a new commercial path under the banking logic to gain legitimacy from commercial investors, this led to the emergence of a workforce culture no longer befitting of its new organizational form. The emerging tension with the hybrid organization is depicted by the thinner arrow in Figure 2 which shows initial internal and external oriented elements beginning to pull apart and become incongruent.

Strategic de-legitimation. The first phase for CETZAM ended with the introduction of the 2006 Banking and Financial Services (Microfinance) Regulation Act. The new act fell under the conventional field of finance introducing a new logic based on profit maximization allowing NGO MFOs to transform into shareholding companies and become licensed with the Central Bank for supervision purposes. Based on this Act, CETZAM moved to a shareholder ownership structure and later became subject to regulations by Bank of Zambia, the national financial regulator. This represented the first major piece of institutional work in the industry – the introduction of a banking logic into a sector previously dominated by the development logic, with donors as its main stakeholders. To adapt to the new environment ‘CETZAM Opportunity’ became ‘CETZAM Financial Services Ltd’, reflecting the redefined logics in the institutional field. This change effectively necessitated that CETZAM turn into a hybrid organisation, meaning that legitimation efforts needed to be tailored to a new audience: commercial investors. Thus, as CETZAM evolved into a for-profit private company (while holding on to its social mission), it was confronted with a new identity and approach to organizing that advanced a view of poverty reduction occurring through growing sustainable ‘for-profit’ organizations. Thus, a core focus on poverty reduction was under threat and in practice, CETZAM started drifting towards the new commercialised banking logic at the expense of its founding ideals.

In responding to the 2006 Act, the trustees of CETZAM as an NGO became shareholders of the ‘new’ private for-profit company and set in motion decisions that aimed at de-legitimising from the donor relationships which were so crucial to accessing resources in Phase 1. However, the actors (management, shareholders and the board) were rather quick in ‘adapting to fit’ (Suddaby et al., Reference Suddaby, Bitektine and Haack2017) with the banking logic. For example, soon after converting to a private company, decisions were taken to move their head office to expensive luxurious office buildings, they applied for a deposit taking license with Bank of Zambia and worked on a complete cut with donors with regards to shareholding and initiated financial relationships with commercial investors. In each of these actions, informants made the following observations:

After converting to a private company, we moved our head office. But all these moves led to increased fixed costs- that were not necessary. For example, CETZAM occupied two and half floors of Mukuba House at a very high cost as this was a high-class building. But you see, head office doesn't generate money, so money from branches was being used to sustain luxury offices! (Informant 3)

In 2008 CETZAM applied to be deposit taking and this created excitement and the thinking was that, we will be a bank and thereafter all will be plain selling. I think it was a mistaken belief that it was going to be rosy and easy. (Informant 2)

Another added:

We were affiliated to donor A and at some point, they even offered to take over CETZAM by buying out the same trustees who had become shareholders, but shareholders didn't allow that to happen. They shot the offer down. (Informant 1)

So, when it came to funding operations and loan book CETZAM decided to contract short term commercial debt until the time it could attempt to raise capital from the stock exchange. For example, in 2008 CETZAM issued commercial papers which were subscribed to, and also initiated borrowing from commercial financial institutions outside Zambia such X and Y. Consequently, we contracted huge debts with several commercial lenders. (Informant 2)

The main requirement of the 2006 Act was that NGO MFOs become share holding companies with most shareholders being local. To apply for a deposit taking license was not required under the new regulations. Indeed, one external informant wondered why CETZAM rushed into it:

I think the regulations have been quite flexible in the sense that it was not compulsory to be deposit taking and was left open as to which tier an MFI could apply for. Each MFI had an option. (Informant 10)

As for complying with shareholding requirements, again CETZAM is said to have missed an opportunity to consider the implications of its hasty decision to decouple itself completely from donors that had been very active in shaping and funding its activities under the development logic. To re-emphasise the implications of de-legitimising with donors, one CETZAM shareholder stated:

the relationship with donor A was broken and CETZAM lost that “big brother” oversight. Somewhere along the line, A was no longer in the picture. The withdrawal of that supervision and financial support had huge consequences on the viability of CETZAM's business. (Informant 6)

Here we see how the environment for the MFO has changed, bringing with it new legitimation dilemmas as they tried to seek new pathways to financial performance beyond their prior reliance on influential donors. But new investor relationships were purely profit driven and the important organizational oversight from donors was lost, detrimental to the organization. Thus, the data highlight the strategic de-legitimation of the MFO – an effort to decouple themselves from previously influential stakeholders (donors) and to mimic the behaviour of commercial banks (e.g., luxurious offices, deposit taking) to legitimise themselves and align with a new audience: commercial investors. We describe this as strategic to demonstrate the deliberate nature of the MFOs direction.

Contradictory workforce culture. The gradual decline of the poverty reduction ethos and decoupling from donors created inevitable internal tensions with respect to how far CETZAM would remain true to its original social mission. Consequently, the social ‘face’ of the hybrid identity began to diminish too, with the workforce experiencing a new form of work culture much of which was inconsistent with the culture in which they had been socialized under the NGO era. We label this here as a contradictory workforce culture. This associated internal tension with the work of employees is exemplified through loan officers who had to balance the previous ethos of nurturing, caring and advising for low-income entrepreneurs against the new ideas of viewing clients as ‘customers’ with a pure focus on outreach, growth and profit of the MFO. Although CETZAM quickly took on a new identity as demanded by the Act, management on the other hand, did not seriously address certain legacy behaviours of staff that were at odds with this new logic. In hindsight, one key informant noted that:

CETZAM carried with it the culture that characterised it as NGO. We moved across with everything donated and the mind-set of employees unchanged. The culture, which you find in an NGO set up, is very different from when you are a profit-making company. So, the NGO mentality was deeply entrenched so that people (workers) believed that we will get money regardless. This culture was so embedded that CETZAM struggled to change. (Informant 1)

This perspective seems to suggest a dissonance between the old imprinted culture and that of the new environment. The new commercialised microfinance world demanded change, but in practice, much of CETZAM's work ethos remained unchanged, indicating a degree of inertia from the MFO. One informant that had been with the MFO since the onset of its transformation and reflecting on the struggle to adapt mindsets, noted thus:

being a limited company by shares means that sustainability of the organisation becomes the focus, whilst as an NGO sustainability is not viewed by most people as priority even though internally you might have that in mind as a key objective. So, while you might have the social mission and sustainability, people's view is that social mission is paramount and even internally the work ethic is more on the social mission than sustainability. (Informant 5)

The legacies of the past continued in less obvious ways to have sway on how CETZAM would organise itself, compete and survive. For example, some loan officers as well as managers and board members continued to act as if they were still under the donor driven era (development logic) where survival was based on access to grants:

You can try to employ newcomers, but as long as you leave even just two old ones, they would start influencing the new arrivals or ‘inducting’ them in their ‘old ways’ of doing things. (Informant 2)

Basically, CETZAM's strategic plan didn't put much emphasis on cultural change-there was no significant investment into it. I would say that efforts to change the old NGO culture were not sustained long enough to permeate worker's mind-sets. Somehow even some senior managers and the board believed that we will still continue to receive some of the donor funding. (Informant 3)

The narratives above suggest challenges hybrid organisations with a strong social mission might face in orientating and aligning their employees’ ethos and that of management and shareholders to market based logics. Whilst this suggests inertia in terms of organizational adaptation, from the point of view of the loan officers, it actually shows resistance to these changes from loan officers who wanted to focus on relationship development with entrepreneurs rather than as a client that needs to meet their contractual obligations.

In summary, the second phase highlights what we label as misaligning legitimation. In new conditions of competing logics, the MFO took on the form of a hybrid organization. Through strategic de-legitimation, the MFO opted to decouple from its key stakeholder relationships, endorsing symbolically (e.g., luxurious office buildings) the new commercialized banking logic. Ultimately, this strategic decision had a knock-on effect on its ability to transition into a stable functioning hybrid organizational form. This inability to transition is exemplified through the second dimension in Phase 2 – contradictory workforce culture. Thus, the symbolic nature of the decoupling seemed to permeate the organization's internal functioning and undermine it.

Phase 3: Circumnavigating over Conformity

By Phase 3, the logic of banking rather than development was now central to the functioning of the industry. We use the label circumnavigating over conformity to emphasise how the MFO over conformed (i.e., legitimated with) to the requirements of the banking logic, to the extent that they no longer bore resemblance to either a functioning MFO or a commercial bank. Thus, they were an organization in mission crisis which was being hamstrung by segregated leadership, whereby senior management and shareholders couple with the new direction of commercialisation despite its obvious deleterious consequences. We refer to this as ‘circumnavigating’ over conformity because of how the leaders avoided the core issues at the centre of the organization. The fractious nature of the organization is depicted by the thin dashed arrow in Figure 2 which shows internal and externally oriented elements being pulled apart.

Segregated leadership. Following Battilana and Dorado's (Reference Battilana and Dorado2010) work on the integration of logics among organizational leaders, we use the term segregated leadership to demonstrate how leaders in CETZAM made a series of decisions in the framing of the banking logic with deleterious consequences. The management and shareholders made decisions, knowingly or unknowingly, that had serious repercussions on the life of the organization and potentially precipitated failure. First, the decision to implement the deposit taking status of CETZAM, then the choice of funding sources, third, the application for a PLC status and be listed on the stock exchange and lastly, the approval of a dividend pay-out. Each of these decisions were undertaken as a legitimation effort with the external audience but came at a great cost and internally conflicted with CETZAM's original social mission.

In 2010, Bank of Zambia approved the application for CETZAM to start receiving public deposits. This was a huge boost to its growth as public savings were expected to be a cheaper alternative source of funding. However, to take on a deposit taking status called for huge investments in physical infrastructure and human resources as required by regulations. In response to being deposit taking, an informant revealed that:

…they [senior management] beefed up management positions like internal audit and marketing section expanded as planned to brand the company like a bank to attract deposits. Other departments were created as a result of the deposit status even though the net benefit was limited. (Informant 3)

Mobilization of public deposits was perceived as status enhancing and legitimacy-building (François, & Philippart, Reference François and Philippart2019), reinforcing the banking logic and regarded internally as an inexpensive source of funding relative to commercial loans (Louis, Seret, & Baesens, Reference Louis, Seret and Baesens2013). However, at issue here to their legitimation approach was the corporate image CETZAM wanted to portray which later became unsustainable as the leaders went an extra mile by opening a premier branch close to their head office in Lusaka. They thought this would be their flagship for the new identity (bank). An informant of the organization noted that:

This branch was refurbished to high standard and to make a statement that we were now a bank! All this euphoria pushed up operational costs and I think we didn't quickly manage this process properly. (Informant 5)

Regrettably, this move did not go as planned as the following quote shows:

I think that setting up a bank like branch was more of a gamble. It didn't work and the branch was empty most of the time. There was an assumption that clients will follow us if we are visible to them. Deposits didn't automatically flow in anticipated amounts as most of the clients we served were not able to keep their savings for long so we could use them to fund our loan book. (Informant 2)

In 2011, one year after their deposit taking license approval, the company converted into a PLC with a view to list on the stock exchange and later that same year a decision was made to pay out dividends. These two decisions would further emphasize the extent to which management and the board went to overconform to the banking logic; with consequent devastating effects on its finances as one interviewee noted:

So, with this, we thought, we could start trading on the stock market, thereby raising more capital. However, 2 years later, our financial figures were no longer attractive and so we couldn't go ahead with our plan because the company was in red. In the end, the plan was shelved but a lot of money had been spent preparing documents required by the Stock Exchange Commission. (Informant 1)

One of the requirements for listing on the stock exchange was for the company to show they were profitable and with a history of having paid out dividends. Therefore, CETZAM made a big dividend pay-out in its quest to list on the stock exchange and obtain resources directly from the market to raise more capital, further exemplifying their over conformity to the banking logic imperative. This move would surprise many, as CETZAM was not yet strong enough financially to declare a dividend.[Footnote 2] Financial performance at the time was noticeably below expectation and huge losses of $2.8 m had been recorded against a profit of $236,363 in 2012 (2013 Annual Report: 6). If the company was running such a thin layer of profits, why did they declare dividends? In conversation, one of the interviewees would reveal the reason:

These shareholders put so much pressure on dividends being made even though the company was in a dire situation. (Informant 2)

However, more importantly, another informant further noted:

This was done so as to have a history and also serve as a good sign to investors as well as help the company register with the stock exchange commission. (Informant 1)

Thus, the payment of dividends was principally to signal investment readiness to the commercial financial and banking sector. Interestingly, discussions with former senior managers revealed the dividends were paid out with the approval of majority of shareholders and the board. Other actors (internal and external), however, viewed this action differently. For example, one shareholder noted, ‘the decision to become a PLC, register on the stock exchange and dividend pay-out compromised bottom-line issues’. An external source also added:

I think the board took their eyes off the threats facing the organization and got on with ensuring the organization met the requirements for listing on the Stock Exchange. (Informant 7)

Through segregated leadership, we see how senior leadership interpreted the banking logic that was now widely accepted within the industry. But rather than pursuing a strategy of integrating both logics together they opted for a segregated approach that focused entirely on aligning with the now dominant banking logic.

Mission crisis. By the final phase of the process, the MFO was an organization experiencing mission crisis – it was no longer meeting either its social or financial objectives. For example, rural branches were closed or scheduled for closure, while loan officers under pressure to generate income, started chasing clients that would borrow large amounts, scaling up and preferring individual loans to group-based loans which tend to be smaller. CETZAM also started tapping into invoice financing and salary-based loans to boost their incomes:

As an institution, we had to respond to these changes and as a result we have over time shifted from relying more on group-lending to individual lending. Currently, CETZAM is focussing more on individual than group lending, and 20% of our portfolio is lent to salaried individuals. (Informant 4)

The aim was to make the income statement attractive, so we changed focus and went for SMEs and invoice financing. This means we went for less risky and bigger volume clients. (Informant 2)

Up to this point in the life of CETZAM as a private company, the deposit-taking venture had disappointed and social funders were hard to come by. So CETZAM intensified its strategy of tapping into external debt, further heightening its social mission conflict. Records from its 2013 annual report show debt spiralling from $1.4 m in 2010 to $1.9 billion in 2014, against a deteriorating loan book-suggesting a downward spiral in the quality of its core business. A well-placed informant indicated that by end of 2013, warning signals were flashing as over 40 per cent of the loan book was non-performing. Thus, for a company whose past growth was funded by donor money, relying on external commercial debt was a fundamental shift and one that would become an enduring challenge:

CETZAM resorted to external borrowing as equity didn't come through existing shareholders. So, we had no choice but to tap into debt financing and this source of financing became a huge burden for the company. (Informant 4)

In desperation, actors responded by borrowing huge amounts of money with a view to growing the organization's loan book but ended up using most of it to plug other financial ‘holes’ in its operations. In addition, CETZAM went on to acquire another rural based MFO, so they could use its rural focus to attract social funders. But this strategy failed too because the MFO was loss making at the point of purchase and only added to CETZAM's deepening financial crisis.

As of 2015, a worrying picture was emerging within the organization having had to deal with an interest rate cap on annual lending interest rates in the previous two years. Revenues had significantly dropped, debt had spiralled, number of employees reduced to 95 from 140, with plans to further reduce to 50 by end of 2015. Its loan portfolio had significantly gone down, with its financial position described as dire. In response, a decision was taken to move offices to a cheaper alternative (residential house), a move that failed to portray the corporate image they had previously embraced. This action, while laudable, came too late to make an impact on finances, leading CETZAM to halt its lending as pressure from creditors over non-loan repayments was mounted. Management were quick to blame their situation on external conditions such as the direct intervention by the regulator through interest rate capping. One of the senior managers made the following remark after asking him to comment on the institution's progress:

CETZAM has not been growing as expected and much as I would like to say we have made progress; the reality is our growth has been negatively impacted by regulations-especially the ones introduced in 2013. To be honest, CETZAM is struggling at the moment and the contributory issue is the regulating of the price (interest rates). (Informant 1)

Later that year the Central Bank also acknowledged that interest rate caps had left a devastating effect on the sector (BOZ, 2015 Annual Report). However, a former senior official who was contacted after CETZAM final collapse in May 2016, noted that the organization struggled to cope with change and went on to summarise the major issues as; poor governance, unmanageable debts, funding problems, mission conflict between commercialization and social goals, and inappropriate regulations. Linking all these themes together is CETZAM's over conformity with the dominant banking logic in the industry and inability and unwillingness to tackle core organizational challenges.

In summary, the final phase of the failure of CETZAM demonstrates an organization experiencing significant conflict; something we label as circumnavigating over conformity. Through segregated leadership, senior management failed to develop structures and practices that could have enabled selective coupling (Pache & Santos, Reference Pache and Santos2013: 973) aspects of their social logic with those of the banking logic. Instead, they over conformed to the now dominant banking logic. This precipitated what we label as mission crisis and the circumnavigation (i.e., avoidance) of the core issues at the centre of the organization. Reflecting on CETZAM's story and its end position, one of its founders made a soul-searching remark regarding its dissolution:

My point is that the whole CETZAM saga lost me money and lost donor money. Most importantly, we lost the capacity to serve poor communities- that was the whole reason why we did CETZAM. (Informant 6)

DISCUSSION

In this article we ask: In hybrid organizations, how do legitimation processes contribute to organizational failure? Through our examination of a failed microfinance organization in Zambia, our study identified a three phased process associated with failure, organizational hybridity and legitimation dilemmas. As a phased representation, Figure 2 is inevitably a simplification of the messy process of interactions we outlined in the results; filled with feedback loops, contestations, moments of hope, potential recovery, and other incidents. We do not mean to imply a natural progression from phase to phase. It emphasises critical moments where the logic emphasis and strategic responses alter as well as the cascade effect of internal and externally oriented decision making over time. This cascade effect also shows how the hybrid moves from tight ‘coupling’ when the organization is in relatively harmonious times and internally coherent. The model depicts how these internal and external elements get pulled apart through ill-conceived legitimation strategies.

The article makes two key theoretical contributions. First, we contribute to theory on hybrid organizing, which seeks to understand the adaptive processes of organizations who experience multiple and often contesting institutional logics. To date, prior research has focused on these strategies and adaptive processes as a way of understanding how hybrids sustain and strive under such pressures (Battilana & Dorado, Reference Battilana and Dorado2010). Yet, very little is known about the processes associated with their failure, with extant literature implying that failure may be the result of an inability to pursue strategies that are flexible to change and promote organizational resilience (Gümüsay et al., Reference Gümüsay, Smets and Morris2020). Figure 2 points to a more complex picture where such adaptive processes are part of the eventual story of failure, sowing the seeds for the organization's eventual demise. Thus, we contribute to theory by highlighting that processes associated with failure are not merely a reverse of strategies that lead to sustaining hybrids.

By adopting our approach to a failed organization, we demonstrate how the path to failure for a hybrid organization may be forged before the organization embraces hybridity. We observe that this occurs through dependent coupling but later becomes exacerbated by strategies of misaligning legitimation and circumnavigating over-conformity. Prior research has identified the relevance of ‘structured flexibility’, hybrid ‘elasticity’ and simultaneous competitive and coexistent relationships (Gümüsay et al., Reference Gümüsay, Smets and Morris2020; Liu et al., Reference Liu, Zhang and Jing2016; Smith & Besharov, Reference Smith and Besharov2019), amongst others, as key strategies to adapt to competing logics. However, we observe similar adaptive and flexible responses to new stakeholder demands (Phase 2) and therefore demonstrate that the strategies failed hybrids adopt are not simply the reverse to those which allow them to succeed. As Figure 2 highlights, we see this flexibility particularly at the juncture between Phase 1 and 2 where the demand for organizational adaptation was at its height. We would propose that a ‘hyper’ flexibility to stakeholder demands (i.e., over conforming) may elicit the deleterious internal organizational strife that CETZAM experienced. In short, such strategies currently discussed within the literature should be considered as the beginning of an open-ended process of contestation and negotiation, and within the context of fields where norms, values and routines may vary.

In contrast to previous hybridity studies, our findings cast light on a context where the demands of external stakeholders (e.g., regulators, investors, donors) are particularly powerful and thus hybridity is not necessarily a proactive pursuit; rather it is predominantly a response to demands of external actors. However, our findings should be further contextualised when considering the underdeveloped nature of the microfinance industry. In mature fields (e.g., healthcare, Reay & Hinings, Reference Reay and Hinings2009), there exists a strong understanding of roles, relationships and routines (Greenwood & Suddaby, Reference Greenwood and Suddaby2006) and therefore organizations converge and conform to a clear set of expectations (DiMaggio & Powell, Reference DiMaggio and Powell1983). In less mature fields such as the microfinance industry or among social purpose cooperatives, (Muñoz, Kimmitt, & Dimov, Reference Muñoz, Kimmitt and Dimov2020), for example, these roles, relationships, routines and organizational templates are less clear and iteratively emerging because of how they challenge incumbent practices. For example, the failure of CETZAM involves multiple iterative developments with regulators regarding what they believe microfinance to constitute (i.e., non-profit activity or work of formal banks). This lack of cross-sector understanding in the field enables heterogenous interpretations for what form such an organization may take. Thus, this article emphasises that the configuration of influential external stakeholders in an emergent industry field context can make strategic choices seem clear in the short term (i.e., legitimise) but that may have deleterious consequences in the long term. As such, this article offers a specific call for research from Besharov and Smith (Reference Smith and Besharov2019) into reactive strategic choices of hybrids.

Second, to understand the relationship between hybrid organizing and failure, we utilised ideas underpinning legitimacy theory (Lounsbury & Glynn, Reference Lounsbury and Glynn2001) and therefore contribute to the venture development legitimacy perspective (Überbacher, Reference Überbacher2014). In this domain, the processes of ‘coupling’ and ‘decoupling’ are viewed as critical to the legitimation processes of firms in institutionally complex conditions (Überbacher et al., Reference Überbacher, Jacobs and Cornelissen2015). In particular, ‘coupling’ concerns how an organization symbolically tightly aligns itself with certain audience frames to gain approval, whilst ‘decoupling’ implies a loosening from such stakeholder expectations so as to gain autonomy. However, our findings point to a more complex picture as hybrid organizations shift their attention between audiences for legitimation purposes.

As we adopt a legitimacy-as-process perspective (Suddaby et al., Reference Suddaby, Bitektine and Haack2017), we can highlight an alternative role of coupling and decoupling strategies. In Phase 1, we observe how tight alignment with stakeholder demands may produce a dependency and a ceding of power to some vital organizational practices whilst Phase 2 highlights how such strategies can misalign the hybrid between its internal characteristics and externally oriented legitimation efforts. In the legitimacy literature, ‘decoupling’ is viewed as a logical strategic response to organizations trying to ‘fit’ with multiple audience expectations. But such a view implies that legitimacy is mainly a commodity utilised by organizations to improve their success/survival by gaining the approval of other – a more deterministic ‘legitimacy as property perspective’ (Suddaby et al., Reference Suddaby, Bitektine and Haack2017). Thus, we contribute to the legitimacy literature by demonstrating how coupling and decoupling strategies are part of a set of emergent activities that occur within a multi-level process and with potentially damaging consequences (Langley, Reference Langley2007).