1. INTRODUCTION

In Quebec, the use of English-origin lexical items (so-called anglicisms) is perceived by many to be a threat to the maintenance of the French language, a sign of assimilation, or even an enemy, and this has been the case since the middle of the nineteenth century (St-Yves, Reference St-Yves2006). L’anglicisme, voilà l’ennemi! is the title of a conference paper presented by the journalist Jean-Paul Tartivel (Reference Tartivel1880: 6) in which he sounded the alarm: “voilà l’anglicisme proprement dit qui nous envahit et qu’il faut combattre à tout prix si nous voulons que notre langue reste véritablement française.” The use of English-origin words has been viewed by many as a sign of contamination and deterioration of the French language. This belief is associated with language purism, an ideology that has been central in the French-speaking world (cf. Bourhis, Reference Bourhis and Coupland1997; Hornsby, Reference Hornsby1998; Vigouroux, Reference Vigouroux2013; Walsh, Reference Walsh2014; Weinstein, Reference Weinstein, Jernudd and Shapiro2011). Language quality has been written about extensively (by linguists and non-linguists alike) and because of the province’s historical background, this question is per se more political than linguistic (Heller, Reference Heller1982). In Quebec, “language equals identity” (Planchon and Stockemer, Reference Planchon and Stockemer2016: 29) and the choice to speak French embodies the Quebecers’ struggle to exist in a majority English-speaking North America. Language policies have been implemented in the province of Quebec to enhance the use and status of French over English. Notably, in 1977, Quebec adopted the Charter of the French Language, making French the only official language of the province and reinforcing its position as the public language of education, work, commerce, and community life. But this, of course, does not stop English from influencing French, since both languages are in everyday contact. Regardless of a dominating ideology in the public discourse that anglicisms are “bad”, anglicisms are not systematically rejected by the Office québécois de la langue française and they are part of most French-speaking Quebecers’ speech (Baillargeon, Reference Baillargeon2017).

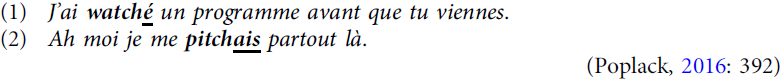

Studies on the use of English-origin lexical items in Quebec French have shown these items borrowed from English are integrated into the French grammar (Poplack, Reference Poplack2018). How do speakers do this? When a lexical item is borrowed from a donor language, the speaker proceeds to making it conform to the morphology and syntax of the receiving language (Poplack, Reference Poplack2016).Footnote 1 For instance, in the case of a verb borrowed from English, the borrowed verb is assigned inflection from French (person, tense, mood). This integration into the French language can be audible (and readable), as in (1-2) for instance, with the ending -é that marks the past participle in “watch” and the ending -ais that indicates the first person of the imperfect in “pitch”:

In some cases, however, the integration is not as obvious because there is no audible morphology (in both English in French), as in (3):

Generally speaking, we can say that all lexical borrowings from English, including the verbs, are integrated into the French language; this has been the common practice in Quebec French. As noted by Poplack (Reference Poplack2016: 391), a linguist invariably referenced for all borrowing-related questions in Canadian French, “nous constatons que tous les verbes d’origine anglaise […] sont intégrés au français, et de la même façon (Poplack, Sankoff and Miller, Reference Poplack, Sankoff and Miller1988; Poplack and Dion, Reference Poplack and Dion2012).”

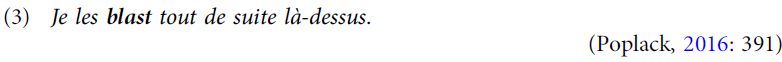

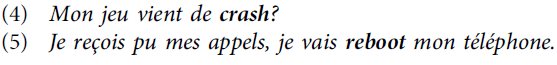

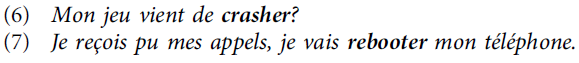

But in recent years, verbs borrowed from English have been used differently by French-speaking Quebecers, especially among the youth in the Montreal area: the borrowed verbs are not integrated into the French language. Instead, speakers use the bare form of the verb; the verb is inserted into the syntax but it remains morphologically unintegrated. The following two sentences (4-5), which were overheard in the speech of young Quebecers, illustrate what I refer to in this article as the use of the bare verbal form:

A traditional use of these English-origin lexical items would show the morphological integration of the verbs “crash” and “reboot”, as in (6-7):

The use of the bare verbal form is more common in the vernacular, which is the style used when speakers are not monitoring their speech, but is also noticeable in the written form on social media, for instance, and in more formal written contexts such as novels. For example, the novelist Jean-Philippe Baril Guérard used the bare form of borrowed verbs for dialogue in his book Manuel de la vie sauvage (2018):

Ève a toujours eu un bon détecteur à connerie; à l’époque ça servait bien Laurent, qui est pas super allumé, généralement. Je dis :

- Busted. Tu dois ben être la seule qui a call bullshit aujourd’hui. (p.104)

C’est impossible d’avoir une table, mais j’ai shoot un DM sur Instagram au proprio pis ils nous a arrangé ça, elle m’explique en s’installant au bas avec moi. (p.109)

The present article examines the use of the morphologically unintegrated English-origin verbs in Quebec French from a sociolinguistic perspective. The objectives of this study are twofold. First, it aims to identify a possible correlation between the evaluation of different uses of English-origin verbs and speakers’ characteristics. The second objective is to determine who the users of the morphologically unintegrated English-origin verbs are and what social factors constrain this use. The research questions are:

RQ1: How do French-speaking Quebecers evaluate the use of morphologically unintegrated English-origin verbs?

RQ2: What social factors (if any) constrain the use of morphologically unintegrated English-origin verbs?

I hypothesize (based on observations) that age and location are the social factors that constrain the use of morphologically unintegrated English-origin verbs, with young Quebecers from the Montreal area using this feature the most and evaluating it more positively. This study represents the first sociolinguistic research on the use of morphologically unintegrated English-origin verbs among French-speaking Quebecers. For the purpose of contextualization, I begin by providing a brief account of the relevant literature on lexical borrowing.

2. BACKGROUND ON LEXICAL BORROWING

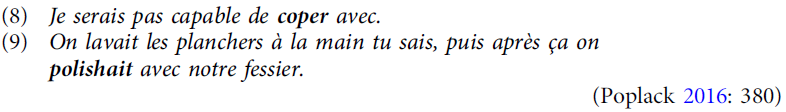

The literature on lexical borrowing is vast and I cannot do it justice in this article. Much of the theoretical literature builds theories of contact-induced language change based on the examination of lexical borrowings in numerous case studies from different languages (cf. Haspelmath, Reference Haspelmath, Haspelmath and Tadmor2009; Lehiste, Reference Lehiste1987; Thomason, Reference Thomason2001; Weinreich, Reference Weinreich1953; Winford, Reference Winford2003). Change is a result of language contact, and the borrowing of words is the most common outcome (Thomason, Reference Thomason2001). Thomason and Kaufmann (Reference Thomason and Kauffman1988: 21) define borrowing as “the incorporation of foreign elements into the speakers’ native language.” There are two types of borrowings: the attested borrowings and the nonce borrowings. Attested borrowings are those that are fully integrated into the receiving language and are used in monolingual speech. Examples of attested English-origin borrowings in Quebec French are business, cool, hot-dog, and burnout. On the other hand, nonce borrowings are those that are not attested in the receiving language (meaning they do not appear in the receiving language dictionaries, for instance), but are adapted to the morphological and syntactic patterns of the receiving language even if uttered only once by a single speaker (Poplack, Reference Poplack2018: 125). Knowledge of the donor language is usually necessary for a speaker of the receiving language to understand and use these words. Examples are nonce borrowings are presented in (8-9).

This study focuses on nonce borrowings (according to Poplack’s (Reference Poplack2018) definition), and more specifically, on nonce borrowings from the English language into the varieties of French spoken in Quebec (grouped under the name Quebec French in this article). It has been shown that the borrowing of lexical items from English differs from the borrowing of lexical items from other languages (e.g., Chelsey (Reference Chelsey2010) for Quebec French), which highlights the importance of investigating English-origin borrowings separately from those of other origins. There is a large body of published work on English-origin borrowings in Canadian French; however, most of it is based on written data. Among the research conducted on English-origin lexical borrowings in everyday oral conversations, the focus has been on morphosyntactic borrowing (e.g., the use of the conjunctions but and so (Roy, Reference Roy1979; Falkert, Reference Falkert, Papen and Chevalier2006; Mougeon, Nadasdi and Rerner, Reference Mougeon, Nadasdi, Rehner, Martineau, Mougeon, Nadasdi and Tremblay2009); verb particles, phrase final prepositions, and wh-words (King, Reference King2000); the discourse markers well and like (Chevalier, Reference Chevalier2007), English-origin verbs and particles (Chevalier and Long, Reference Chevalier, Long, Brasseur and Falkert2005)) and less on the sociolinguistic aspects of borrowing. The first known empirical study of lexical borrowing in Quebec French is Lavallée’s (Reference Lavallée1979) study in the Eastern Townships region of Quebec, a region that has had significant contact with English speakers in the past. The most impactful empirically-based study on language contact and borrowings in Canadian French is that by Poplack and colleagues (cf. Poplack, Sankoff and Miller, Reference Poplack, Sankoff and Miller1988; Poplack and St-Amand, Reference Poplack and St-Amand2007; Poplack and Dion, Reference Poplack and Dion2012; Poplack, Reference Poplack2018) on the Quebec-Ontario border.

From a sociolinguistic perspective, it is of utmost interest to examine the social factors that constrain the use of English-origin borrowings. In their studies, Poplack and her colleagues have found that the extra-linguistic factors associated with more frequent borrowing are proficiency in English (the most bilingual speakers use more English-origin borrowings), intensity of contact with English (speakers on the Ontario side use more English-origin borrowings than those on the Quebec side), socioeconomic status (unskilled workers and the unemployed borrow more than workers in the highest occupational classes), and age (young people use more English-origin borrowings than their elders). Gender and level of education seem to have no effect on the use of borrowings.

Grammatical adaptation of lexical borrowings varies from one language to another, but may also vary within a single language (Grant, Reference Grant2015). This is the case for the borrowing of verbs in French. For instance, studies from Dubois and Sankoff (Reference Dubois, Sankoff, Auger and Rose1997), Picone (Reference Picone1994, Reference Picone, Bernstein, Nunnally and Sabino1997), Root (Reference Root2018), and Rottet (Reference Rottet2016, Reference Rottet2019) have shown that verbal borrowings in Louisiana French can lack overt morphological integration, similar to the use of English-origin borrowings in Quebec French discussed in this article. These unintegrated lexical borrowings have been called bare forms. Root (Reference Root2018: 33) describes the bare form as “a ‘foreign’ or ‘donor’ lexical item (e.g. a lexical verb) that is stripped of its native morphology and then inserted into the syntax of the recipient language, where it then remains morphologically unintegrated.” Examples of these borrowings in Louisiana French are:

Dubois and Sankoff (Reference Dubois, Sankoff, Auger and Rose1997) and Root (Reference Root2018), as other scholars interested in Louisiana French, have demonstrated that a variety of lexical insertion strategies exist in the speech of French speakers in Louisiana but that the use of the bare form is the preferred strategy for English-origin lexical verb insertion. The case of the bare verb forms in Louisiana French is particularly relevant when investigating the use of English-origin verbs in Quebec French because the two varieties show similarities in their absence of overt morphological integration. This sets them apart from other varieties of French in North America (see Papen (Reference Papen2022) for a review on the topic). Both Louisiana French and Quebec French also challenge Poplack’s (Reference Poplack2018) binary view of borrowing and code-switching. Authors have taken different positions regarding whether to classify the bare forms in Louisiana French as instances of borrowing or code switching. These include Rottet (Reference Rottet2019: 199), for example, who rejects Poplack’s theory based on data from Louisiana French and Acadian French and argues that “la binarité traditionnelle emprunt-alternance codique est simpliste et ne reflète pas la complexité réelle des communautés profondément bilingues.” To him, code switching and borrowing should be viewed as a sliding scale rather than two separate phenomena, as the two lexical strategies serve the same role for the speakers, namely: to access their lexical resources (in French and English) without having to switch the language they are using. As mentioned above, according to Poplack and her colleagues, borrowings are integrated into the morphological and syntactic patterns of the receiving language. However, Rottet argues that some of the bare verb forms in Louisiana French are well-attested, and even if they are neither morphologically nor phonologically integrated into French, they should be considered as borrowings due to their wide distribution and predictability.

Before Rottet, Picone and his colleagues (e.g., Klingler, Picone, and Valdman, Reference Klingler, Picone, Valdman and Valdman1997; Picone and Lafleur, Reference Picone, Lafleur, Latin and Poirier2000) also took an interest in the bare verb forms in Louisiana French. For them, bilingualism largely explains why the integration of the English-origin words is superfluous, as all Louisiana speakers understand the English terms in their bare forms. Klingler, Picone, and Valdman (Reference Klingler, Picone, Valdman and Valdman1997: 174) view the bare forms as a “buffer code”:

Although [Cajun French]-speakers do not prove to have sufficient language loyalty to ward off English, they may have arrived at a compromise strategy that involves some special morphological processing of lexical switches in order to arrive at a partial intercode acting as a buffer (hence, “buffer code”).

This code buffering serves as a strategy to allow access to English lexical resources while limiting the assimilation to English. The social, linguistic, and political context of Louisiana is clearly different from that of Quebec, but this similarity is worth mentioning before we examine the preferred patterns in Quebec French.

The current variationist study on the borrowing practices in Quebec French was not developed with the intention of contributing to the debate on the distinction between borrowing and code-switching (cf. Bentahila and Davies, Reference Bentahila and Davies1983; Gardner-Chloros, Reference Gardner-Chloros and Hickey2010; Myers-Scotton, Reference Myers-Scotton1993; Sankoff, Poplack, and Vanniarajan, Reference Sankoff, Poplack and Vanniarajan1990, Meechan and Poplack, Reference Meechan and Poplack1995, Poplack and Meechan, Reference Poplack and Meechan1998). However, since the results do represent a problem for Poplack’s (Reference Poplack2018) binary view of code-switching and borrowing, this central question cannot be ignored. Weinreich (Reference Weinreich1953) was the first linguist to draw a distinction between code-switching and borrowing. Code-switching is “the use of material from two (or more) languages by a single speaker in the same conversation” (Thomason, Reference Thomason2001: 132). Code-switches and nonce borrowings are difficult to tease apart and linguists do not agree on the differentiation of the two. Poplack and Meechan (Reference Poplack and Meechan1998: 127) have addressed this “fundamental disagreement among researchers about data”, but the disagreement persists to this day. There are two main approaches to whether and how to differentiate code-switching and borrowing. One approach is proposed by Poplack and colleagues: they argue that both are fundamentally different. For them, as mentioned earlier, nonce borrowings are single lexical items that are morphologically and syntactically integrated into the receiving language. These may or may not show phonological integration (Poplack et al., Reference Poplack, Robillard, Dion and Paolillo2020). Code-switching, in contrast, “refers to alternation (cf. also Muysken, Reference Muysken2000) of stretches of one language with stretches of another” (Poplack, Reference Poplack2018: 7). The other approach rather considers that the two processes cannot be distinguished at a synchronic level (Gardner-Chloros, Reference Gardner-Chloros and Hickey2010) and that there is no need to do so to analyse bilingual speech (Bentahila and Davies, Reference Bentahila and Davies1983; Myers-Scotton, Reference Myers-Scotton1993). The use of morphologically unintegrated English-origin verbs in Quebec French thus represents an interesting case for researchers interested in this debate.

3. METHODS

3.1. Participants

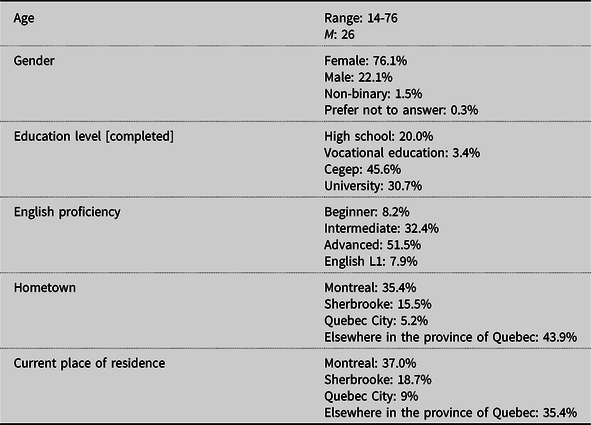

The participants were 675 French speakers who grew up and who currently live in the province of Quebec (514 females, mean age = 26, range = 14-76). All of the participants have completed a high school degree, with the exception of one participant. A high number of participants attended a general and professional teaching college (called cegepFootnote 2 ) (n = 308) or a university (including undergraduate and graduate studies) (n = 207). Regarding the degree of proficiency in English, more than half the participants reported having an advanced level of English (n = 345) or speaking English as one of their first languages (L1) (n = 53). The only participant who does not speak English was excluded from the analyses related to English-language proficiency. Out of the 670 participants who reported the place where they grew up, more than half are from the three most populous cities in the province of Quebec, i.e., Montreal (n = 237), Sherbrooke (n = 104), and Quebec City (n = 35),Footnote 3 while the others (n = 294) grew up in different villages, towns, and cities around the province. The same goes for the current location, with participants living in Montreal (n = 248), Sherbrooke (n = 125), Quebec City (n = 60), and elsewhere in the province (n = 237).Footnote 4 Table 1 summarizes the profile of the participants.

Table 1. Profile of the participants (n = 675)

The three main cities where the participants are from are quite different from a historical, demographic, and sociolinguistic perspective. First, Montreal is the largest city of the province of Quebec and nearly half of the province’s population live in the metropolitan area. Montreal is culturally diverse and it is the most trilingual city of Canada (CBC, 2017). This diversity is certainly related to immigration; in 2021, 33.4% of the population of Montreal reported having immigrant status (Statistics Canada, 2021a). Although the province favours Francophone immigration, the number of multilingual immigrants in Montreal is high; more than one third of immigrants who arrived in Montreal between 2011 and 2016 were trilingual. According to the most recent Census, the residents of Montreal who speak French as a first language make up the majority of the city’s population, at 62.7%. Also, 58.5% of the population in Montreal reported being bilingual in English and French, the two official languages of the country (Statistics Canada, 2021a). Second, Sherbrooke and its surroundings are part of the Eastern Townships region of Quebec and is located 147 kilometers east of Montreal. Sherbrooke was a manufacturing center in the 1800s and for many years was a commercial, industrial, and railway centre. Until the 1970s, English speakers were in the majority in the Eastern Townships (which includes Sherbrooke, Granby, Magog, Cowansville, and other smaller towns). But then an exodus to other parts of Canada began and as a result, Sherbrooke and its surroundings are now predominantly French-speaking (OCOL, 2013). In comparison with Montreal, the percentage of immigrants is much lower (10.6%) and the percentage of bilingual residents is also lower (46.6%). French is the first language of 92.6% of the Sherbrooke residents (Statistics Canada, 2021b). Third, Quebec City is the capital of the province and it is the second largest city after Montreal. It is located on the north shore of the Saint Lawrence River, 250 kilometers east of Montreal. Compared to Montreal and Sherbrooke, there is a lower number of immigrants in Quebec City (8.5%) and a lower number of official language bilingual residents (42.7%). French is the first language of 96.3% of the Quebec City residents (Statistics Canada, 2021c).

3.2. Data collection

In order to investigate the use of English-origin verbs in Quebec French and attitudes toward it, a questionnaire was created as a research tool for the collection of data. The social media site Facebook was used as a tool to recruit potential participants. Social media recruitment techniques, which have been used with increasing frequency in the past few years, have shown effectiveness in recruiting different populations (Gelinas et al., Reference Gelinas, Pierce, Winkler, Cohen, Fernandez Lynch and Bierer2017). The interconnected nature of Facebook, the networking of users with “friends”, and the possibility of reaching segments of the population that may not otherwise be accessible are key features that make Facebook (and other social media) attractive to researchers. For this research project, I posted a link to the study questionnaire on my own Facebook page and I asked my “friends” to share it on their own Facebook page with their “friends”. I also posted the study on the Facebook page of most French-speaking cegeps in the province of Quebec. The questionnaire was conducted online and was divided into three main parts: an evaluation of different sentences containing an English-origin lexical verb, a report of the participants’ own practices related to the use of different forms of English-origin lexical verbs, and a background questionnaire. All the sentences used in the questionnaire had been previously overheard by myself or by friends who reported these sentences to me. Three judges (from Montreal, Gatineau, and Quebec) were asked to validate the sentences as being grammatical and representative of the (integrated and unintegrated) use of English-origin verbs in the province of Quebec (or at least, in some parts of the province).

It is important to mention that while the questionnaire is a method of choice for studies on language attitudes, it is not the most robust method for documenting the variable usage of a linguistic feature. This is partly because speakers usually have to report choosing one form over another, whereas community usage shows more variability than reported usage. Another limitation of the questionnaire is that it provides data in written rather than oral form; this might influence the participants’ responses to some extent. Such limitations were taken into consideration by inviting participants to add the form they would use when it differed from the options given, and by encouraging them to say the sentences out loud when evaluating the use of different sentences. Nonetheless, it is important to keep in mind that this article presents reported use of variation and not actual variation. In this sense, it is not a traditional variationist study that relies on examination of attested used in its social context. In the following subsections, I describe the three main parts of the questionnaire.

3.2.1 Evaluation of the use of English-origin verbs

In the first part of the study, participants were invited to evaluate the use of English-origin verbs in different sentences that were presented to them. All these sentences contained the bare form of an English-origin verb. They were informed that some sentences may appear to be ungrammatical or incorrect in the written form, but that they should not worry about the grammar rules of written French. They were invited to say the sentences out loud, as this could be helpful in evaluating the oral use of these sentences. For each sentence, the participants were asked the following question: If you heard someone say this sentence, would it sound acceptable to you? They were asked to answer this question using a Likert scale with five points: totally acceptable (5 points), rather acceptable (4 points), rather unacceptable (3 points), totally unacceptable (2 points), I don’t understand the meaning of this sentence (1 point). Here are the 14 sentences they evaluated:

-

1. Je vais aller me get une bière au dép.

-

2. Mon jeu vient de crash.

-

3. Y’a reach pour l’prendre.

-

4. On n’a pas give up.

-

5. J’vais share mon écran.

-

6. Ça m’a dead.

-

7. Ça work juste pas.

-

8. J’avais juste swap sa DM.

-

9. J’espère que tu vas pas fail avec ton projet.

-

10. C’est la seule façon que j’arrive à cope avec la situation.

-

11. Il a été cancel.

-

12. Peux-tu bring mon cell quand tu vas venir?

-

13. Je reçois pu mes appels, je vais reboot mon téléphone.

-

14. As-tu get la fille?

3.2.2 Report of own practices regarding English-origin verbs

In the second part of the study, the participants were presented with ten pairs of sentences; the sets of two sentences have similar meanings but use a different insertion strategy for the English-origin verbs. In one sentence, the lexical borrowing is morphologically integrated into the French language, and in the other one, it is not. The order of the sentences was randomized (meaning that the integrated and unintegrated forms would not always be presented in the same order). Participants were asked to check the sentence that they would use and they were informed that they could check both. If none of these two sentences corresponded to their own use of a borrowing to express a similar idea, they could check a third answer: neither one nor the other. Here are the ten pairs of sentences used in the questionnaire:

-

(a) J’ai domp ma blonde.

-

(b) J’ai dompé ma blonde.

-

(c) Ni l’une ni l’autre! Je dirais plutôt ceci: ________________.

-

(a) T’as juste à scroll en bas.

-

(b) T’as juste à scroller en bas.

-

(c) Ni l’une ni l’autre! Je dirais plutôt ceci: ________________.

-

(a) As-tu enjoyé ton voyage?

-

(b) As-tu enjoy ton voyage?

-

(c) Ni l’une ni l’autre! Je dirais plutôt ceci: ________________.

-

(a) Je l’ai texté hier.

-

(b) Je l’ai text hier.

-

(c) Ni l’une ni l’autre! Je dirais plutôt ceci: ________________.

-

(a) Il m’a ghost.

-

(b) Il m’a ghosté.

-

(c) Ni l’une ni l’autre! Je dirais plutôt ceci: ________________.

-

(a) Tu m’as skipé.

-

(b) Tu m’as skip.

-

(c) Ni l’une ni l’autre! Je dirais plutôt ceci: ________________.

-

(a) J’ai bu du vin et j’ai pass out dans mon lit.

-

(b) J’ai bu du vin et j’ai passé out dans mon lit.

-

(c) Ni l’une ni l’autre! Je dirais plutôt ceci: ________________.

-

(a) Est-ce que Paul va être kické out du cours?

-

(b) Est-ce que Paul va être kick out du cours?

-

(c) Ni l’une ni l’autre! Je dirais plutôt ceci: ________________.

-

(a) On doit upgrade notre forfait d’internet.

-

(b) On doit upgrader notre forfait d’internet.

-

(c) Ni l’une ni l’autre! Je dirais plutôt ceci: ________________.

-

(a) Tu m’as spottée dans mon auto.

-

(b) Tu m’as spot dans mon auto.

-

(c) Ni l’une ni l’autre! Je dirais plutôt ceci: ________________.

3.2.3 Background questionnaire

Finally, the questionnaire elicited information about participants’ age, gender, education level, English proficiency, where they grew up, and where they currently live. This information is used to investigate the correlation between these social factors, the use of morphologically unintegrated English-origin verbs, and the attitudes toward it.

3.3. Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using R version 4.0. In the first part of the study, I explore whether the participants’ evaluation of the different uses of English-origin borrowings correlates with any of the social factors from the background questionnaire. The analyses of these evaluations were conducted factor by factor. To test if participants of different ages evaluated the use of borrowings differently, a Kendall Rank Correlation test was carried out using cor() function from the stats R package. For gender, a two-sample t-test was performed with the t.test() function; this was also performed for English proficiency. For education level and the place where the participants grew up, I performed one-way ANOVAs using the anova_test function from the rstatix R package, followed by a Tukey test for post-hoc pairwise comparisons, also with rstatix. To determine whether there is significance between current location and evaluation of borrowings, I used a Kruskal Wallis test and Dunn’s tests (post-hoc) from the rstatix package.

In the second part of the study, I investigate the relation between the use of unintegrated forms of English-origin lexical verbs and different social factors. A two-sample t-test was performed with the t.test() function as well as the Pearson correlation coefficient with the cor.test function to examine any correlation between gender and use of borrowings. The Pearson correlation test was also used for age. For the four other factors, one-way ANOVAs were performed, again using the anova_test function from the rstatix R package.

4. RESULTS

The results of the statistical analyses regarding the use of English-origin verbs are divided into two main sections: evaluation of the use of morphologically unintegrated English-origin verbs and report of participants’ own use of English-origin verbs.

4.1. Evaluation of the use of morphologically unintegrated English-origin verbs

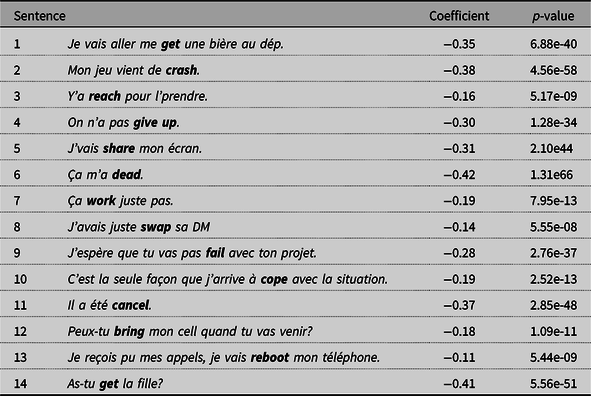

Participants were asked to evaluate the use of morphologically unintegrated English-origin lexical verbs in 14 different sentences, as presented in section 3.2.1. The objective is to determine whether the participants’ evaluation correlates with their gender, age, education level, English proficiency, hometown, and the city they live in. The analysis of these evaluations is conducted factor by factor.

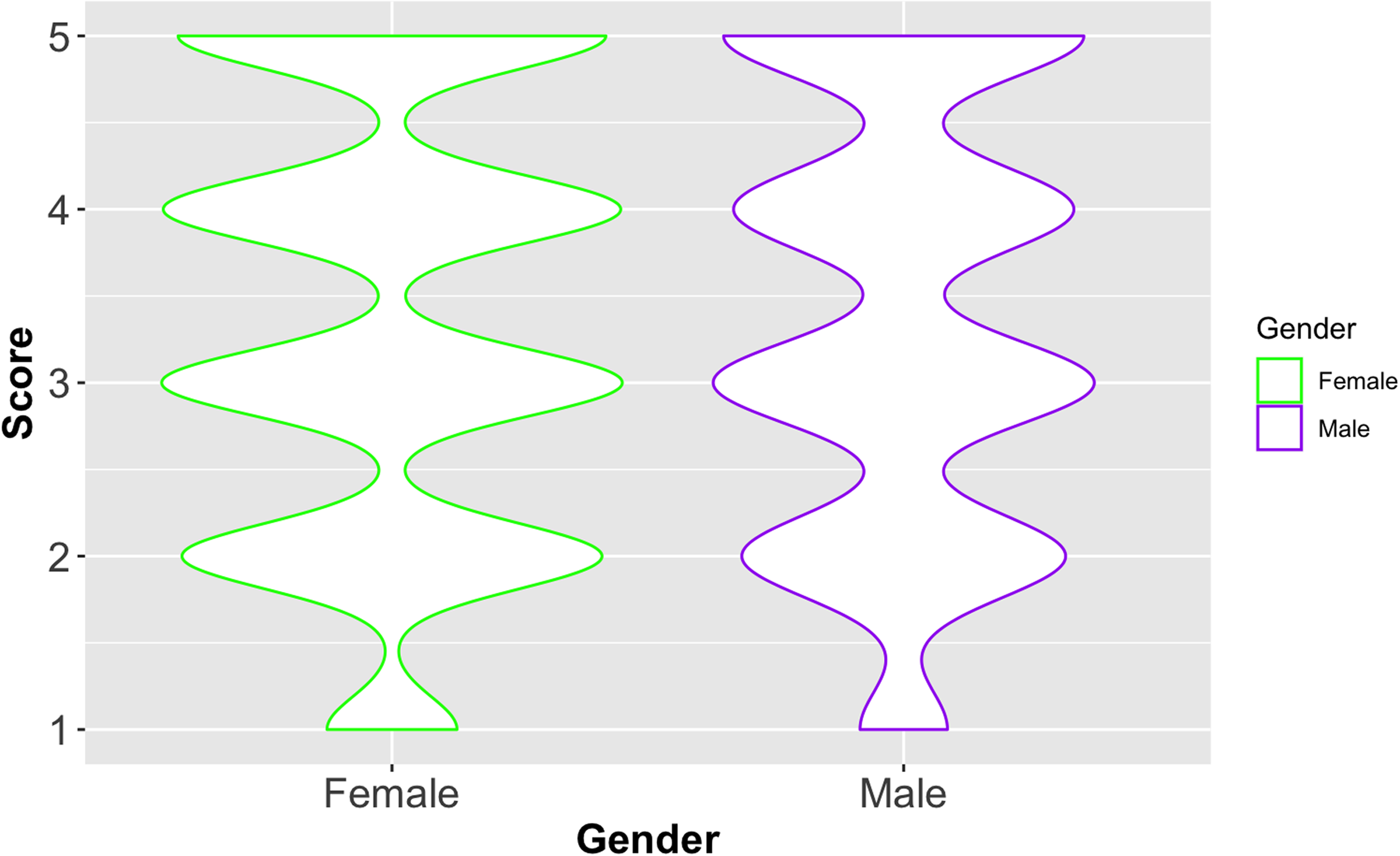

Gender

The results indicate that participants who identify as female and male evaluated the use of English-origin verbs similarly.Footnote 5 Figure 1 is a violin plot that depicts the distribution of the participants’ acceptance of the use of borrowings. To understand the violin plot, on each side of the line is a kernel density estimation that shows the distribution shape of the data. The width of each curve corresponds with the approximate frequency of data points for each score (from 1 to 5). Wider sections of the violin plot represent a higher probability. The violin plot is useful when observing the distribution of numeric data and when comparing distributions between groups. The shapes can be compared to see where groups are similar or different. And in this case, we see that the density curves are similar for both genders. A two-sample t-test (p = 0.70) confirmed that there is no statistical significance between the two genders in their evaluation of the different sentences. Further correlation analysis conducted for each sentence also confirmed that no significant correlation was found.

Figure 1. Evaluation of the use of morphologically unintegrated English-origin verbs by gender.

Age

After taking the average of the evaluation scores, the association between age and the overall evaluation results was tested with the Kendall Rank Correlation.Footnote 6 The results indicate that there is a significant negative correlation between the participants’ age and their evaluation (r = -0.56, p = 2.2e-16). In other words, older participants evaluated the use of morphologically unintegrated English-origin verbs more negatively than younger participants. When examining the correlation sentence by sentence, we can see that the strength of negative correlation varies across sentences. Table 2 shows the sentences with moderate (6, 14) and weak correlation (1, 2, 4, 5, 11); the other sentences did not show statistical significance.

Table 2. Correlation analysis of evaluation of the sentences and age by sentence

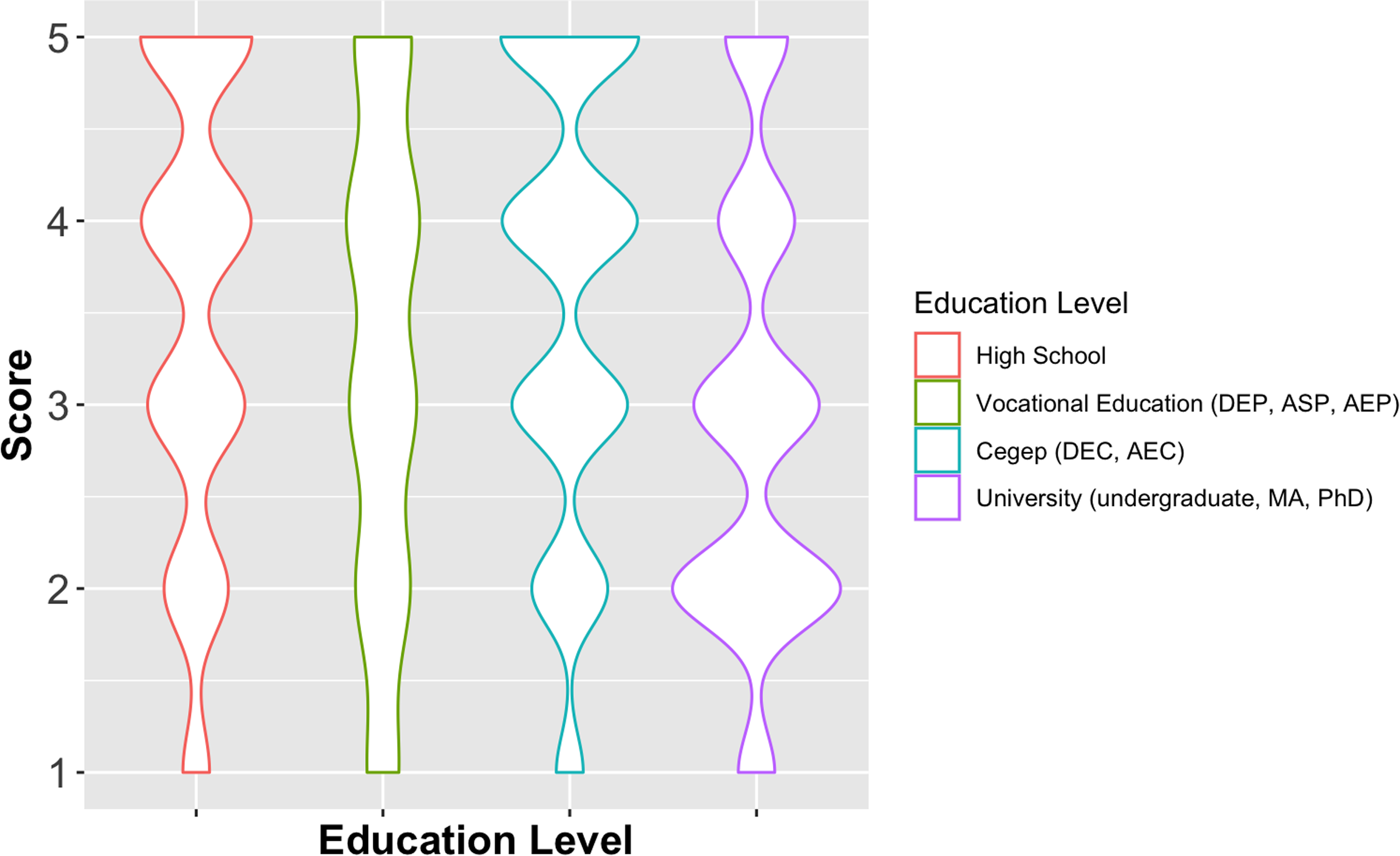

Education level

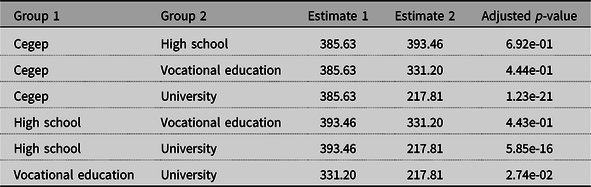

Participants with a university degree present far more negative attitudes toward the use of unintegrated English-origin lexical verbs compared to participants with a lower level of schooling, as shown in Figure 2. The rating patterns of participants with a high school degree are similar to those of participants with a cegep degree. The rating behaviour of participants with vocational training is less obvious due to its small sample size.

Figure 2. Evaluation of the use of morphologically unintegrated English-origin verbs by education level.

To verify whether the observed difference is statistically significant, I implemented an analysis of variance (ANOVA) over the grouped evaluation scores, which assesses the differences among group means by testing whether the means of at least two groups are different. After obtaining a significant result with the ANOVA (p = 5.83e-20), I ran Tukey’s tests to find out which specific group means (compared with each other) are different. The outcomes of the Tukey’s tests reported in Table 3 indicate that the use of morphologically unintegrated English-origin lexical verbs is evaluated significantly more negatively by participants who completed university studies than those who have a high school or cegep degree.

Table 3. Results of Tukey’s Test on evaluation score and education level

That being said, there is moderate positive correlation between age and education level with statistical significance (r = 0.52, p = 2.19e-38), tested with the Kendall Rank Correlation. In addition, when encoding age into five age groups (< 19, 20-29, 30-39, 40-49, > 50) and calculating the Kendall’s correlation between age group and education, there is moderate positive correlation between age group and education level with statistical significance (r = 0.56, p = 7.83e-49).

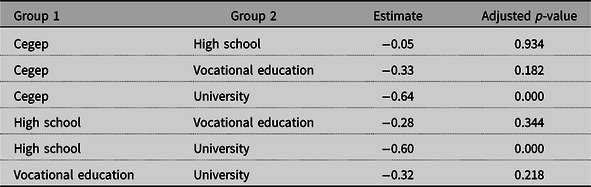

English proficiency

The violin plot in Figure 3 shows that participants who reported having a beginning level of English and those speaking English L1 rated the sentences with the use of morphologically unintegrated English-origin lexical verbs as unacceptable (score 2) less frequently compared to the two other groups. In addition, participants in the group of intermediate and advanced English speakers share a more or less similar pattern, except that advanced English speakers selected the option “totally acceptable” (score 5) more frequently. Since the English proficiency variable is ordinal, four levels are assigned as follows: 1 - beginner, 2 - intermediate, 3 - advanced, and 4 - English L1. Performing correlation analysis on encoded English proficiency and evaluation scores shows that English proficiency is significantly correlated (p = 7.56e-05) with the evaluation of the use of English-origin lexical verbs, despite the fact that the correlation is very weak (r = 0.127).

Figure 3. Evaluation of the use of morphologically unintegrated English-origin verbs by English proficiency.

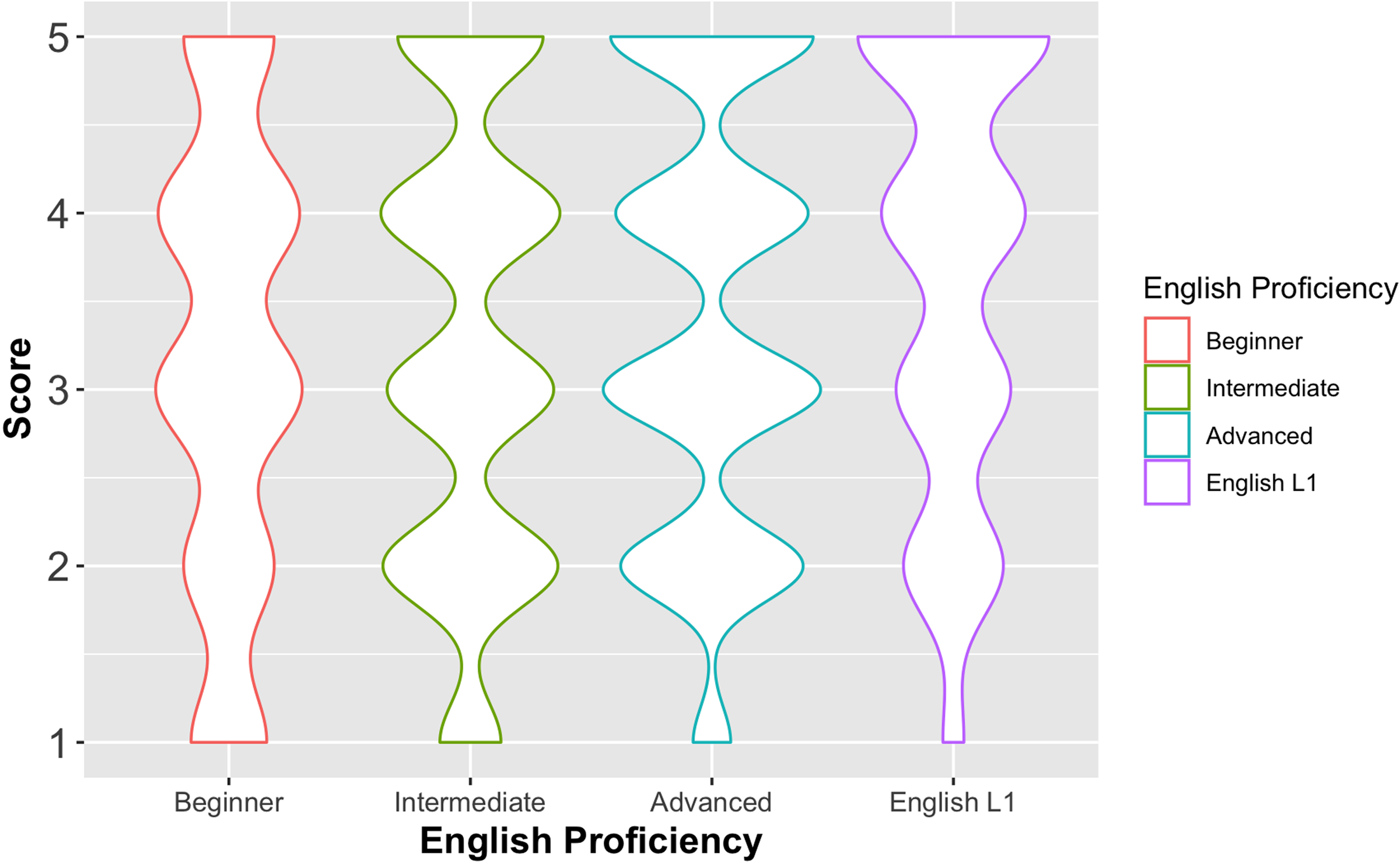

Hometown

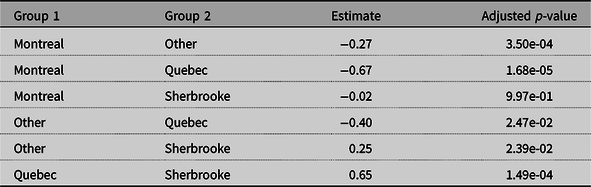

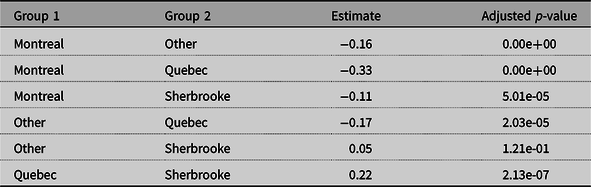

In Figure 4, the kernel density of the violin plot for the groups who grew up in Montreal, Sherbrooke, and elsewhere in the province of Quebec is very similar in shape. Participants who grew up in Quebec City evaluated the sentences as “totally unacceptable” (encoded as 2) much more frequently compared to the other groups. The ANOVA result is significant (p = 2.36e-07) and the Tukey’s tests (post-hoc analysis) show that participants who grew up in Montreal hold significantly more positive attitudes toward the use of morphologically unintegrated English-origin lexical verbs compared to those who grew up in Quebec and in other locations in the province categorized as “Other” in Figure 4. Participants who grew up in Quebec evaluated the use of morphologically unintegrated English-origin lexical verbs more negatively than people who grew up in all other locations. The difference between the participants who grew up in Montreal and those who grew up in Sherbrooke is not significant. The results of the Tukey’s tests are presented in Table 4.

Figure 4. Evaluation of the use of morphologically unintegrated English-origin verbs by place growing up.

Table 4. Evaluation of the use of morphologically unintegrated English-origin verbs: Results from Tukey’s test on place growing up

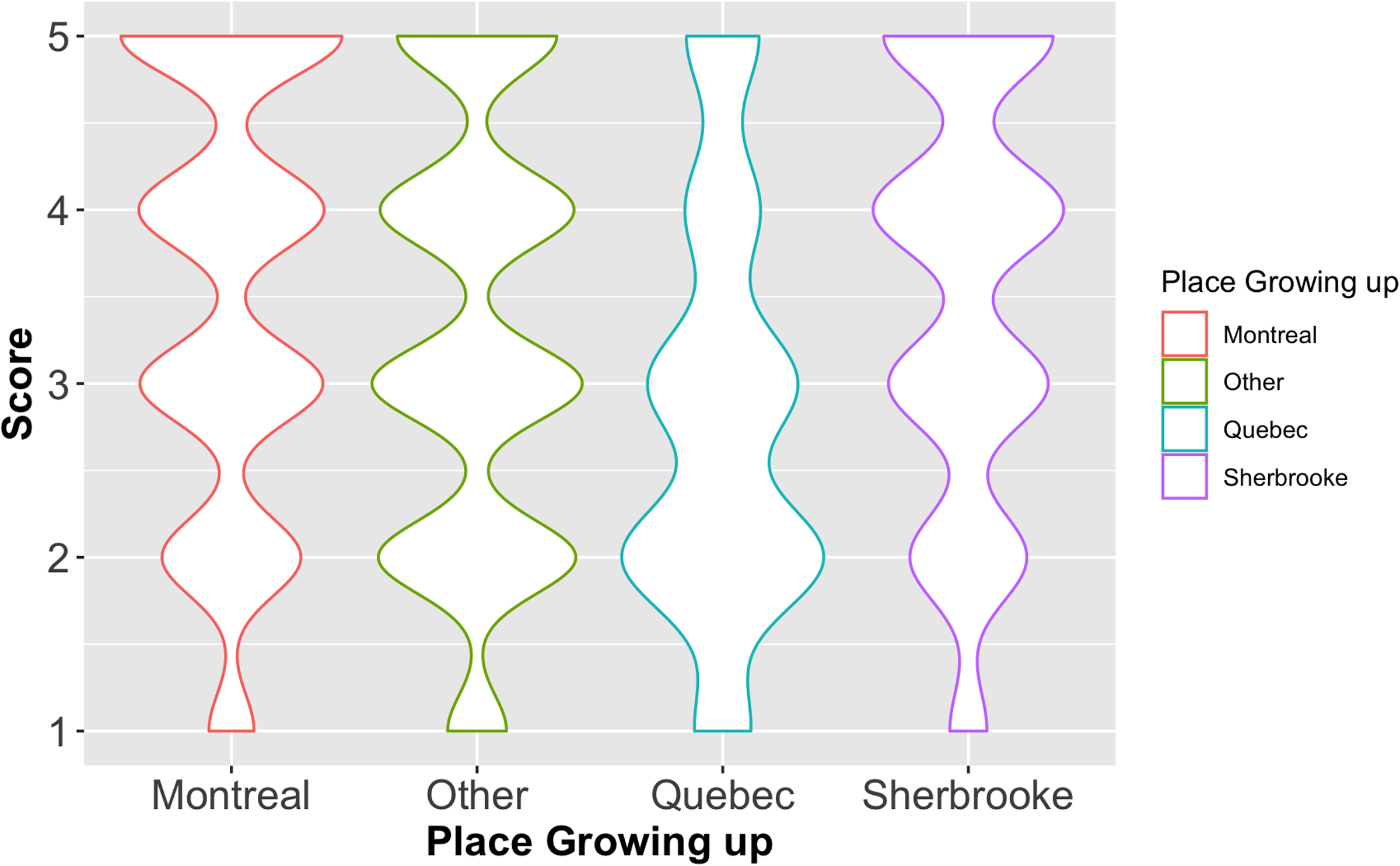

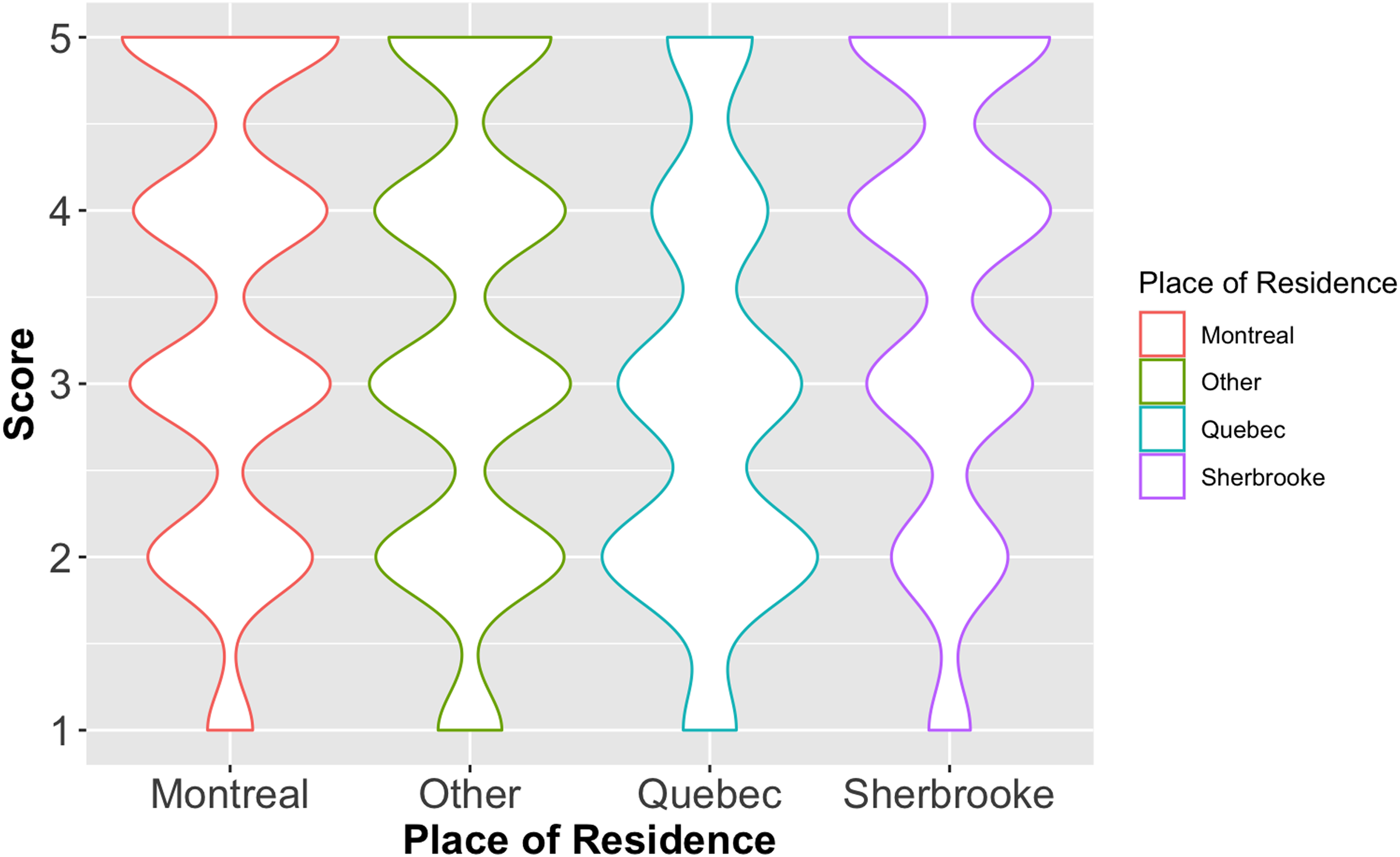

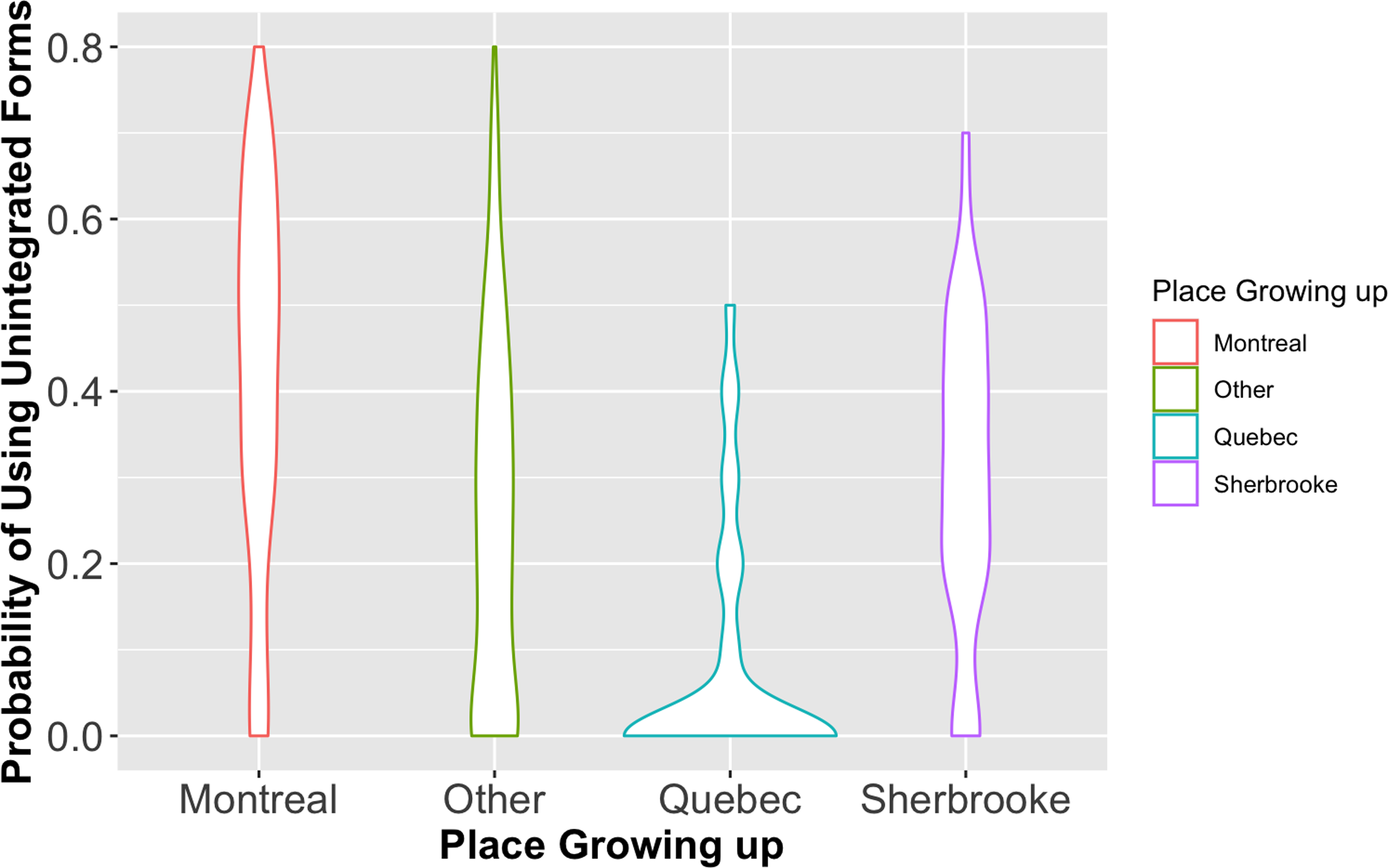

Current place of residence

Figure 5 shows that participants living in Quebec City evaluated more sentences as unacceptable compared to the other groups. By contrast, participants from Sherbrooke gave the fewest unacceptable ratings. Since the data for current location does not satisfy the assumptions of ANOVA, the statistical test used for verifying the empirical findings is a Kruskal Wallis test and Dunn’s tests (post-hoc). With the significant result from the Kruskal Wallis test (p = 1.86e-06), Dunn’s tests find that the use of morphologically unintegrated English-origin lexical verbs is significantly less acceptable to people living in Quebec than those living in Montreal, Sherbrooke, and other locations. Again, there is no significant difference between the residents of Montreal and Sherbrooke. More details about the post-hoc analysis are presented in Table 5.

Figure 5. Evaluation of the use of morphologically unintegrated English-origin verbs by place of residence.

Table 5. Evaluation of the use of morphologically unintegrated English-origin verbs: Results of Dunn’s Test on place of residence

4.2. Report of own use of English-origin lexical verbs

In the second part of the questionnaire, the participants were given ten pairs of sentences and were asked to choose the sentence(s) that they would use in a conversation. Within each pair, the two sentences have a similar meaning but present a different use of the English-origin lexical verbs: in one sentence, the lexical item is morphologically integrated into the French language and in the other one, it is not integrated. This part of the questionnaire examines possible answers to RQ2: What social factors (if any) constrain the use of morphologically unintegrated English-origin lexical verbs? The responses for each pair of sentences are sorted as follows:

Both: use both of the provided sentences

MUEV (morphologically unintegrated English-origin verb): use the morphologically unintegrated form

MIEV (morphologically integrated English-origin verb): use the morphologically integrated form

Neither: use neither of the provided sentences

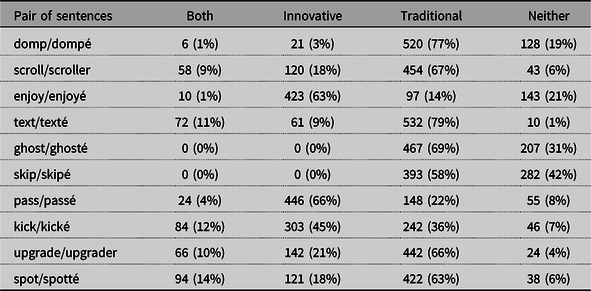

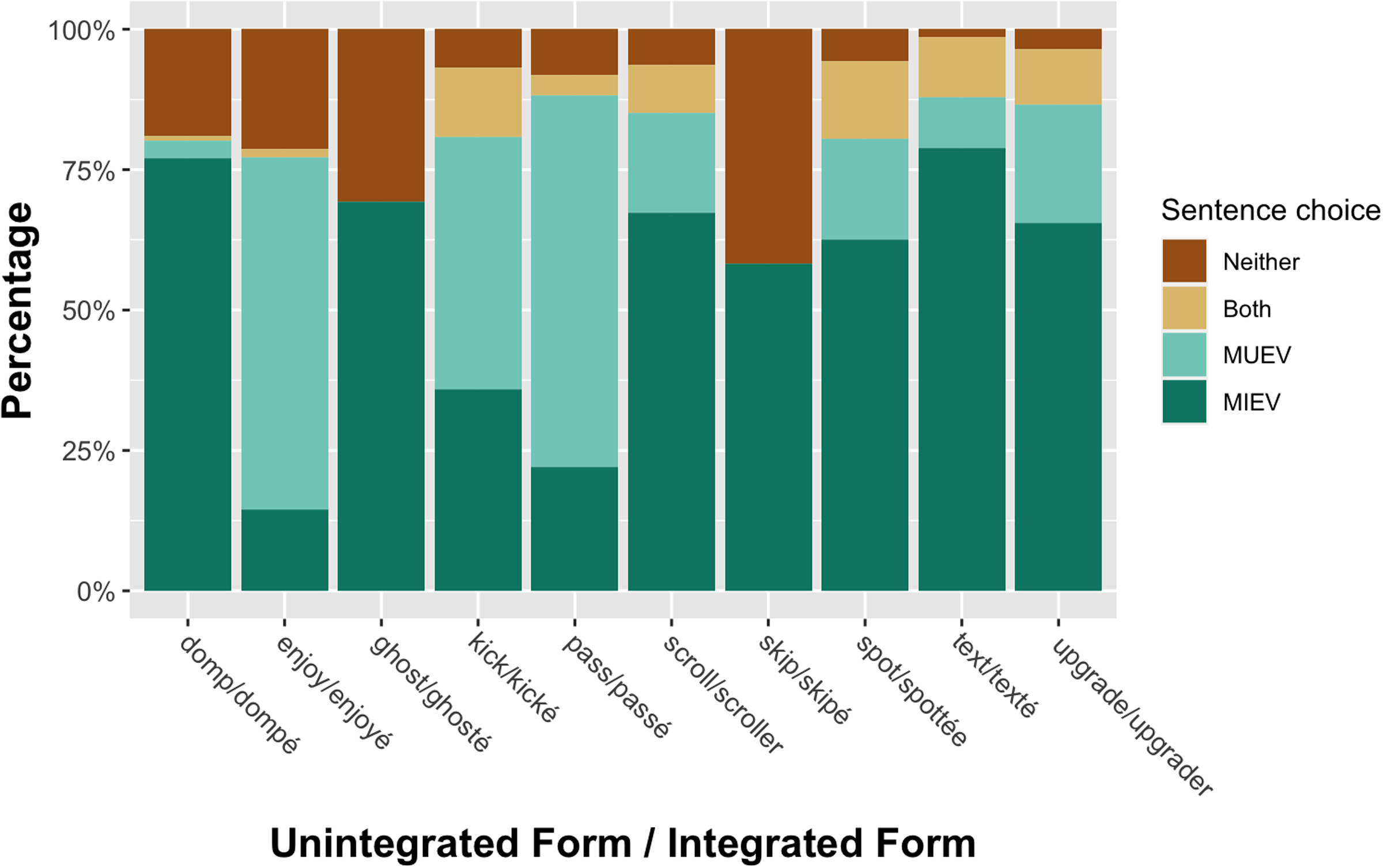

To see how many people used each of the sentences presented in section 3.2.2, the number and percentage of the different choices are summarized in Table 6, and for a clearer demonstration, the proportions are visualized in Figure 6. In Figure 6, we can see that the morphologically unintegrated forms are used particularly frequently for the pairs enjoy/enjoyé, kick/kické, and pass/passé. In the other pairs of sentences, the morphologically integrated forms appear to be more dominant. This is especially the case for the pairs ghost/ghosté and skip/skipé, where no respondent selected the morphologically unintegrated forms provided.

Table 6. Summary of the use of different English-origin lexical verbs in each sentence

Figure 6. Percentage of use of different English-origin verbs in each pair of sentences.

Since RQ2 mainly focuses on the use of morphologically unintegrated forms, the four levels of response data will be merged into two levels: using unintegrated forms (MUEV and both) and not using unintegrated forms (MIEV and neither). I will explore the same set of social factors as in Section 3 with the frequency with which each respondent uses morphologically unintegrated forms among ten sentences.

Gender

For gender, no significant difference is found between females and males from a two-sample t-test (p = 0.966) and no significant association exists between gender and the use of morphologically unintegrated English-origin verbs (r = −0.0017; p = 0.964).

Age

For participant age, a strong negative association with statistical significance is found to exist between age and the use of morphologically unintegrated English-origin lexical verbs (r = -0.60, p = 2.2e-16, with a Pearson correlation test). In other words, younger people are more likely to use sentences with the unintegrated forms of borrowings. This is consistent with previous studies that indicate that language varies across different age categories and that young people tend to use forms perceived as non-standard more frequently (Chambers, Reference Chambers1995; Eckert, Reference Eckert and Coulmas1997; Labov, Reference Labov1966, Reference Labov1972; Peccei, Reference Peccei, Thomas and Wareing1999).

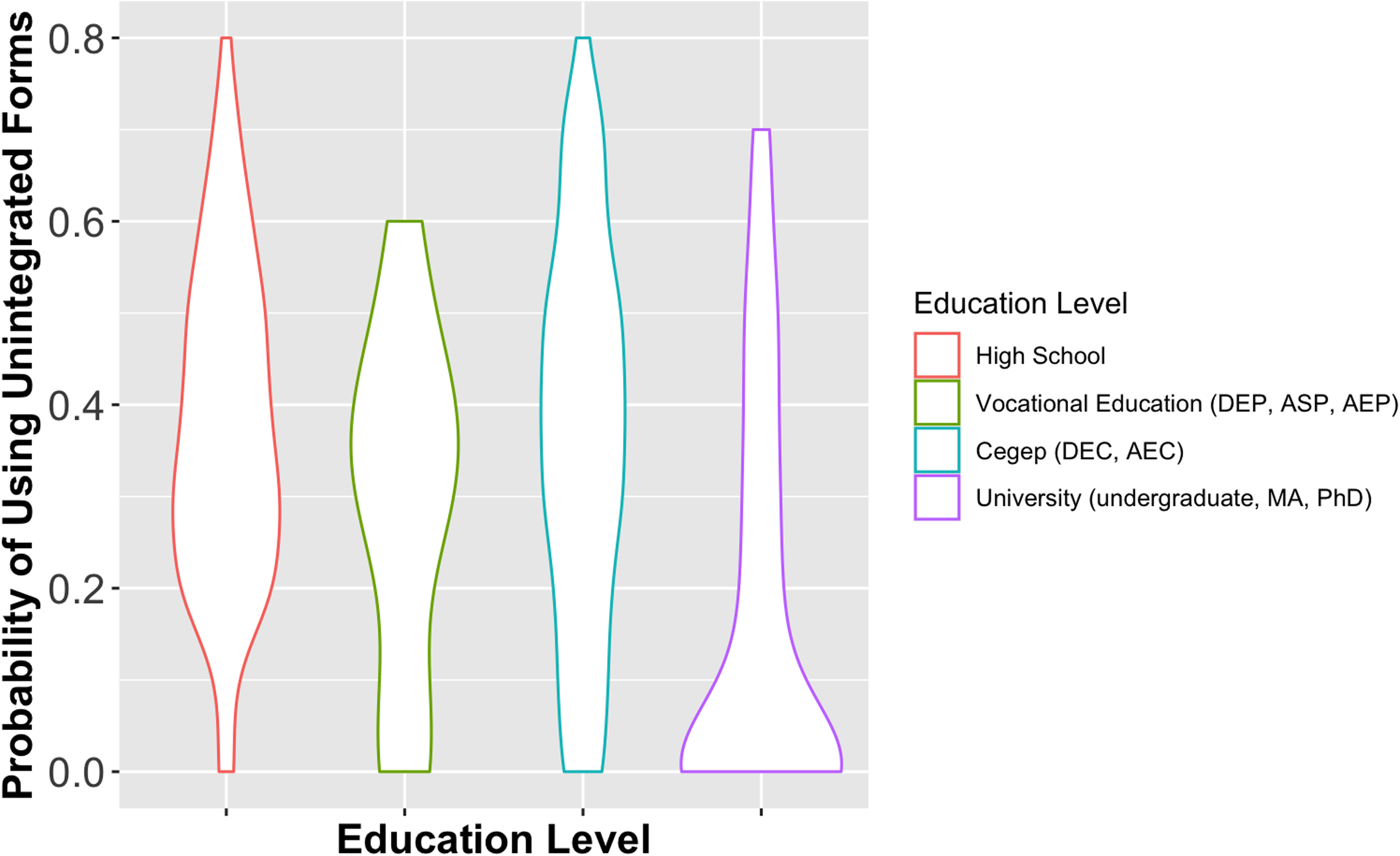

Education level

For education level, Figure 7 shows that participants with a university degree appear to use the morphologically unintegrated forms far less frequently than people with other education backgrounds, and these differences are confirmed by the Kruskal Wallis test (p = 5.87e-24) and post-hoc Dunn’s tests in Table 7. Otherwise, no other significant difference can be found between groups.

Figure 7. Frequency of use of morphologically unintegrated English-origin verbs by education level.

Table 7. Use of morphologically unintegrated English-origin verbs: Results of Tukey’s test on education level

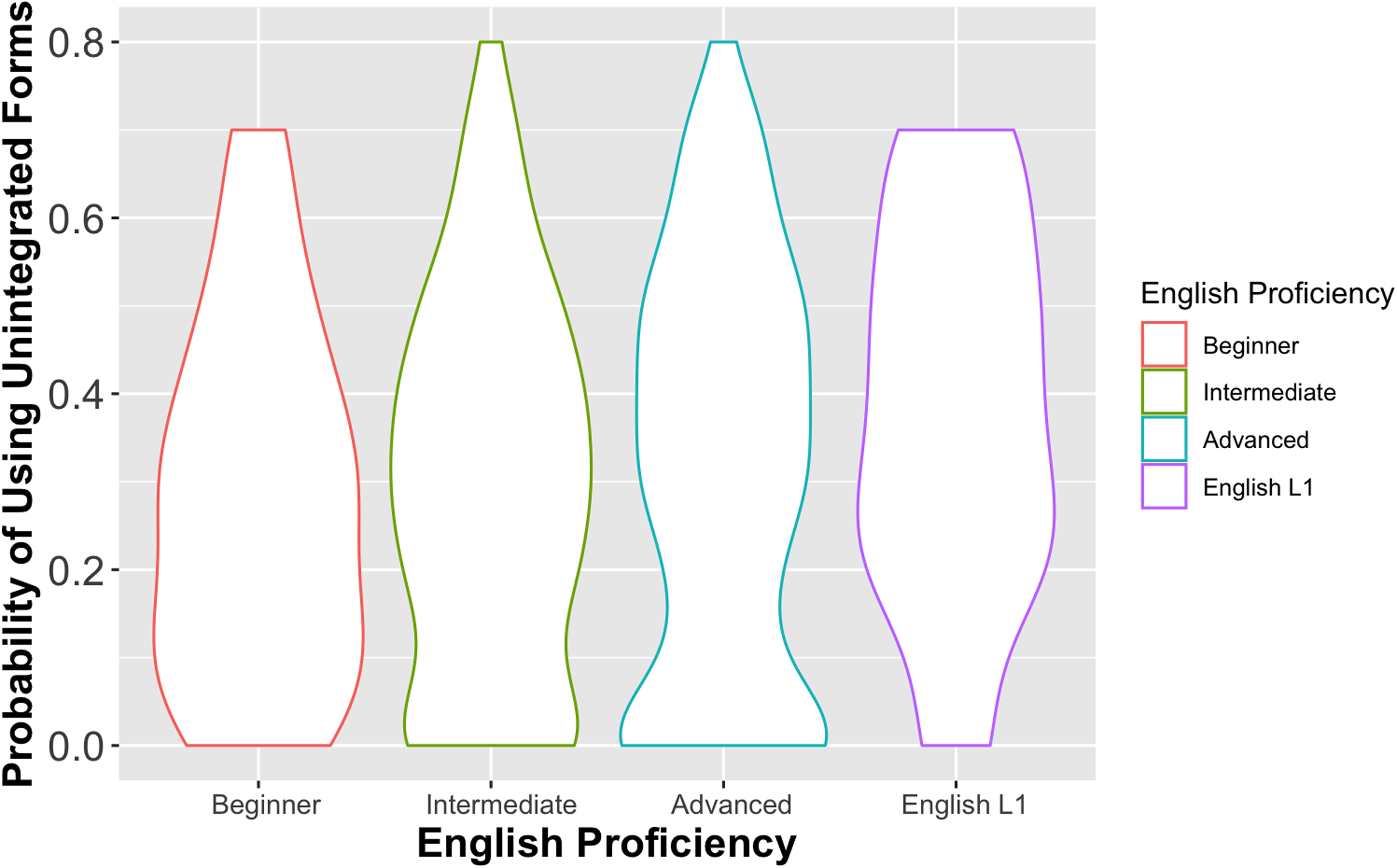

English proficiency

The correlation analysis for use of morphologically unintegrated English-origin verbs and English proficiency indicates that there is no association between English proficiency and the use of unintegrated forms (r = 0.06, p = 0.04), and ANOVA finds no significant difference existing among the four groups (p = 0.08). Despite the lack of statistical evidence, the results in Figure 8 show that only participants with an intermediate and advanced level of English use the morphologically unintegrated form in more than seven sentences.

Figure 8. Frequency of use of morphologically unintegrated English-origin verbs by English proficiency.

Hometown

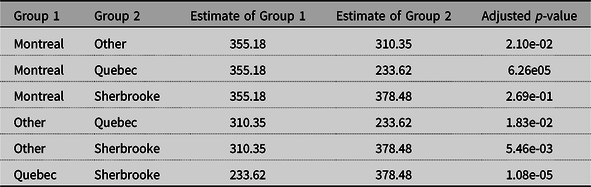

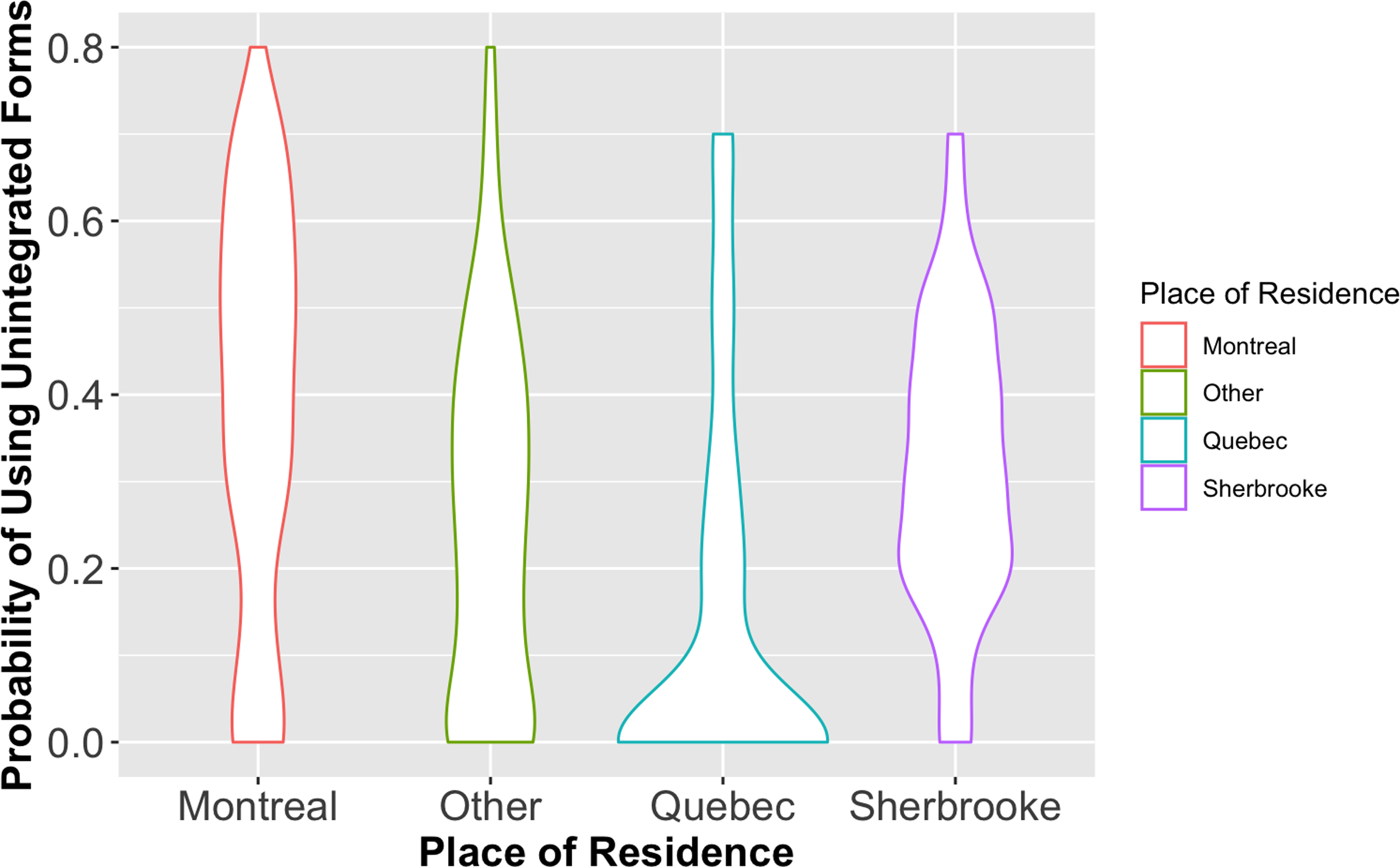

Statistical tests were implemented to seek significant differences in the use of morphologically unintegrated English-origin lexical verbs among the four location-related groups: Montreal, Sherbrooke, Quebec, Other (meaning elsewhere in Quebec). Grouping by the hometown where participants grew up, ANOVA shows the existence of significant differences (p = 2.86e-16). Examining the results of post-hoc analysis using Tukey’s method in Table 8, we see that the participants who grew up in Quebec City use the unintegrated forms significantly less than the participants who did not grow up in Quebec City. Taking a closer look at the response data in Figure 9, we can see that most people who grew up in Quebec City rarely use unintegrated forms: no individual uses more than five unintegrated forms and the probability of using none of the unintegrated forms is particularly high. By contrast, people growing up in Montreal use the unintegrated forms with significantly greater frequency than the other groups, which can be observed in Figure 9 as well.

Table 8. Use of morphologically unintegrated English-origin verbs: Results of Tukey’s test on place growing up

Figure 9. Frequency of use of morphologically unintegrated English-origin verbs by place growing up.

Current place of residence

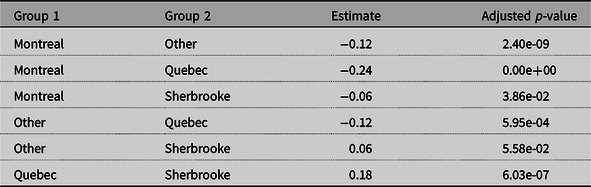

When it comes to the place the participants currently live in, the observations and test findings are aligned with those of the analysis for place growing up. Figure 10 and Table 9 together demonstrate that participants living in Montreal use the unintegrated forms significantly more than the other groups, and the unintegrated forms are used significantly less by people living in Quebec City.

Figure 10. Frequency of use of morphologically unintegrated English-origin verbs by place of residence.

Table 9. Use of morphologically unintegrated English-origin verbs: results of Tukey’s test on place of residence

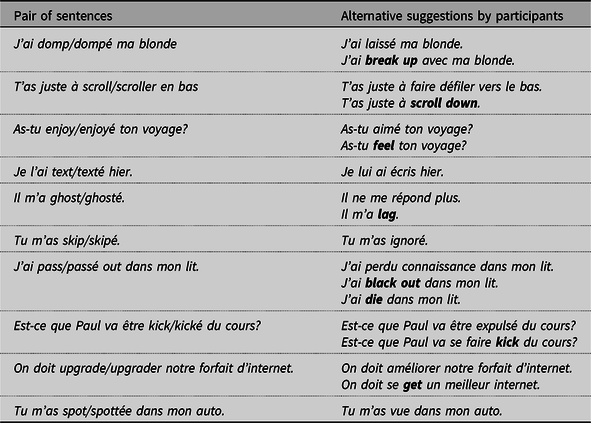

In this section, participants were asked to choose between two different uses of English-origin lexical verbs (unintegrated and integrated), but they could also choose the option “neither one nor the other” and specify what they would have said instead. Fewer participants chose this third option, and when they did, it was generally to offer an alternative sentence without an English-origin word. Table 10 presents the alternative sentences suggested by the participants. In the first line (on the right side) is the most commonly suggested alternative with no use of borrowing, and in the second line, an alternative with another borrowing (if any). It is interesting to note that the most commonly suggested alternatives that use a borrowing are forms that are morphologically unintegrated.

Table 10. Most common alternative sentences suggested by participants

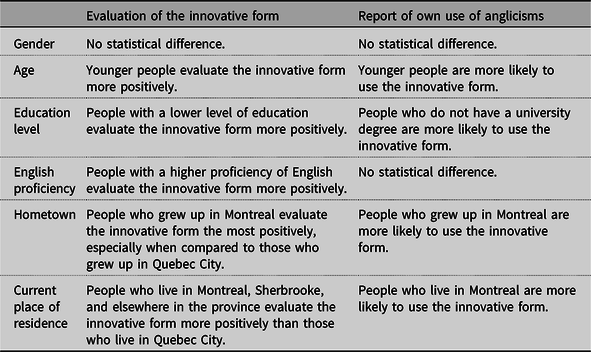

These findings are summarised in Table 11.

Table 11. Social factors that constrain the use of morphologically unintegrated English-origin verbs in Quebec French

Let us now discuss these main findings in greater detail.

5. DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

This study is the first to identify and analyse social factors associated with the morphologically unintegrated English-origin verbs as used in Quebec French. The objectives were to determine how French-speaking Quebecers evaluate the unintegrated forms of English-origin lexical verbs and what social factors constrain this use. Results indicate that young Quebecers from Montreal with a high level of proficiency in English are the ones who use it the most and evaluate it more positively.

The results show no difference between genders in the evaluation of the unintegrated verb forms and their use of them. This aligns with the work of Poplack and her colleagues who also found that gender has no effect on the use of borrowings. A number of studies on language and gender point out that women are more sensitive to normative usage (see Romaine, Reference Romaine, Holmes and Meyerhoff2003 for a review). For instance, Labov (Reference Labov2001) argues that women are more conservative than men in situations of stable sociolinguistic stratification and that they tend to favor the use of more prestigious forms. However, in situations of ongoing change, women tend to use the new forms more frequently. In this sense, a more frequent use of the integrated form by women could have indicated a preference for a form that is more socially accepted (as this form is known and attested in Quebec French), or a more frequent use of the unintegrated form could have indicated a change in progress (as this use is more recent). But the examination of gender and use of borrowings (whether integrated or not) does not point in either of these two directions.

Variationist sociolinguists acknowledge that we speak differently depending on the age group to which we belong. Young people particularly tend to favour forms that can be perceived as non-standard and less prestigious by older speakers. The results of this study clearly indicate that younger speakers evaluate the unintegrated forms more positively and they report being more likely to use them. This result corroborates observations (i.e., personal observations and comments shared when collecting sentences for this research project) and qualitative analyses regarding the use of unintegrated forms (Bouchard, forthcoming). In these analyses, the gap between the users and non-users of the unintegrated forms is age-related, with non-users harshly criticizing the use of the unintegrated forms.

In the work of Poplack and her colleagues, education level is not a factor that constrains the use of English-origin borrowings. This contrasts with the results of this study, which show that speakers of Quebec French with a university degree evaluated the unintegrated forms more negatively and are less likely to use these forms. This difference might be due to the method of choice as the questionnaire captures reported usage and perception rather than the actual usage analysed by Poplack. But people with a higher level of education generally have more exposure to the influence of the standard language. This certainly indicates that the unintegrated forms are perceived as divergent from the linguistic practices of individuals with a university degree, who then most likely perceive them as non-standard forms.

One could expect that the most bilingual speakers use more English-origin borrowings (see Poplack, Reference Poplack2018). However, the results for reported usage of unintegrated forms do not indicate any statistical difference between the four levels of proficiency in English. Nonetheless, it is still important to note that participants who have a beginner or L1 knowledge of English reported using the unintegrated forms less frequently than those who have an intermediate or advanced level of English. Speaking English as an L1 does not entail a more frequent use of the unintegrated forms (although they may look and sound more like the English forms).

Regarding hometown and current place of residence, participants from and living in Quebec City evaluated the unintegrated forms quite negatively compared to the other participants and they also reported being less likely to use them. Interestingly, the population of Quebec City has a higher percentage of residents who speak French as an L1, a lower percentage of bilingual speakers (English-French) and a lower number of immigrants compared to Montreal and Sherbrooke (see Section 3.1). In fact, Quebec City is not as multilingual and multicultural as Montreal (or Sherbrooke to a certain extent) and it did not have contact with local English speakers in the past the same way Montreal and Sherbrooke did (or still do, in the case of Montreal).

Because hometown and place of residence were maintained as two separate factors in this study, we can see that although participants who currently live in Montreal, Sherbrooke, and elsewhere in the province evaluated the unintegrated forms more positively than participants who live in Quebec City, it is those who grew up in Montreal who evaluated them the most positively. This might indicate that the use of the unintegrated form is a linguistic innovation that is emerging from Montreal.

All these findings are interesting from a sociolinguistic perspective, but they are also of relevance to researchers seeking to distinguish code-switches from nonce borrowings. According to Poplack and her colleagues, as mentioned earlier, when English-origin items are morphologically integrated into French, they are nonce borrowings; and when they remain morphologically integrated into English, they are instances of code-switching. However, this theory cannot explain the use of morphologically unintegrated English-origin verbs in Quebec French, since the bare forms possess neither French nor English inflection. For instance, in the sentence Il m’a ghost, with the unintegrated form, no participant suggested the use of “ghosted”, Il m’a ghosted, which would have been an instance of code-switching according to Poplack’s theory. Same for J’ai pass out dans mon lit, which would be J’ai passé out dans mon lit if integrated into French (and therefore, a nonce borrowing) or J’ai passed out dans mon lit if integrated into English (and therefore, a code-switch). These English-origin verb forms in Quebec French are not morphologically integrated into either French or English, which poses a theoretical problem according to Poplack’s (Reference Poplack2018) theory.

Poplack’s exhaustive work on borrowings does not address data from Louisiana French nor recent data from Quebec French in which unintegrated English-origin verbs would appear.

In his review of Poplack (Reference Poplack2018), Papen (Reference Papen2021) considers that a possible explanation for the bare forms in Louisiana French is the variable deletion of infinitival or participial suffixes. Picone (Reference Picone1994: 273) has some evidence of this deletion in Louisiana French (e.g., Ils ont apprend les chansons). But as Papen (Reference Papen2021: 273) mentions, there are no quantitative studies on the subject that can support this hypothesis. Could this hypothesis be applied to the unintegrated forms of English-origin verbs in Quebec French? Clearly, further investigations on the topic are necessary to answer such a question and to address other issues that this research project raised; for instance, how do these bare forms fit into the typology of contact phenomena? What are the motivations for this linguistic innovation? What are its implications?

To provide a theoretical contribution to language contact theory, it is necessary to collect spontaneous speech data from Quebec French. This data would be of utmost interest for scholars seeking to distinguish borrowings from code switches. But as Gardner-Chloros (Reference Gardner-Chloros and Hickey2010: 186) has written, “[a]t a synchronic level, there is no failsafe method of distinguishing between loans and codeswitches, as only time can tell if a loanword is more generally adopted over time.” It would also allow us to examine how the instances of interference (whether integrated or not) co-exist within the same community, and even within the same individual. This article indicates that there is still a lot to learn about the language-mixing strategies in Quebec French.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their insightful and constructive comments. I would also like to thank Yanic Viau for helpful discussions and support.