Folk magic and folk medicine practices that involved the use of archaeological artefacts have been documented across much of northwest Europe, including Scotland, England, Finland, Sweden, Denmark, Germany and Estonia (Blinkenberg Reference Blinkenberg1911; Bonser Reference Bonser1926; Carelli Reference Carelli, Andersson, Carelli and Ersgård1997; Hall Reference Hall2005; Hukantaival Reference Hukantaival2016; Johanson Reference Johanson2009; Merrifield Reference Merrifield1987; Penney Reference Penney1976). The most common phenomena include the interpretation of Neolithic and Bronze Age flint arrowheads as fairy darts that were both the cause and cure of illnesses, particularly in animals, and a belief that prehistoric polished stone axes were thunderbolts that fell to earth during a lightning strike and could safeguard the family home. In Ireland there is plentiful archaeological and folkloric evidence for the use of prehistoric artefacts in folk magic and medicine. The topic has been highlighted in folklore scholarship since the nineteenth century, most significantly by Penney (Reference Penney1976), but is almost entirely absent from archaeological discourse. This is part of the broader ‘firm and wary distance’ and ‘estranged relationship’ that has traditionally existed between the disciplines of archaeology and folklore, not just in Ireland, but across Europe and North America (Thompson Reference Thompson2004, 335–8). This paper aims to highlight the rich and complex biographies that many prehistoric artefacts assumed in recent centuries in Ireland, which diverged entirely from the scholarly interpretation of these same artefacts as relating to ancient human societies. The sites and objects discussed here are identified by townland (or locality) and county name (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Ireland by county. (Map: James Bonsall.)

The past decade has seen an explosion of publications related to the field of folk magic in medieval, post-medieval and modern times, penned primarily by historians (e.g. Bailey Reference Bailey2007; Boschung & Bremmer Reference Boschung and Bremmer2015; Davies Reference Davies2016; Hutton Reference Hutton2015). Ralph Merrifield is typically acknowledged as the first scholar to explore magic from an archaeological perspective in his seminal book, The Archaeology of Ritual and Magic (Reference Merrifield1987). Since then, notable archaeological studies include Gilchrist's (Reference Gilchrist2008) exploration of the archaeology of magic in late medieval burials in Britain; the role of prehistoric artefacts as magical implements in medieval Sweden (Carelli Reference Carelli, Andersson, Carelli and Ersgård1997); prehistoric artefacts, fossils and bones that relate to folk magic and witchcraft in Scotland (Cheape Reference Cheape, Goodare, Martin and Miller2008); thunderbolt magic in Estonia (Johanson Reference Johanson2009); the materiality of magic (Houlbrook & Armitage Reference Houlbrook and Armitage2015); shoes as spiritual deposits in English houses and buildings (Houlbrook Reference Houlbrook2013; Reference Houlbrook2017); and Finnish building concealment magic (Hukantaival Reference Hukantaival2016). In Ireland, the disciplines of archaeology and folklore (as distinct from archaeology and medieval literary texts) scarcely meet, though with some exceptions (e.g. Champion & Cooney Reference Champion, Cooney, Gazin Schwartz and Holtorf1999; Dowd Reference Dowd2015, chapters 9 & 10). The archaeology of magic in Ireland has received even less attention, apart from some cursory overviews such as O'Sullivan et al. (Reference O'Sullivan, McCormick, Kerr and Harney2014, 98–101), who have explored folk magic as an explanation for the presence of prehistoric artefacts in early medieval settlements. Similarly, Kelly (Reference Kelly2012), Gilligan (Reference Gilligan2017) and Nicholl (Reference Nicholl2017) have interpreted finds built into three specific nineteenth-century houses as reflecting ritual deposits to safeguard the home and/or avert misfortune (see below). Anderson et al. (Reference Anderson, Flynn, O'Byrne, Walsh and Weadick2013) drew attention to two medieval silver caterpillar amulets from Co. Cork that were used in recent centuries for cattle curing. Overall, however, considering the wealth of evidence (archaeological, historical, documentary and oral tradition) for folk magic practices in Ireland—practices that are still remembered by many people living today—it is unfortunate that there has been so little archaeological interest in this field.

The sí

Since the seventeenth century, the discipline of archaeology in Ireland, as in much of Europe, has been concerned with the investigation and documentation of past cultures through the surviving material culture and physical remains (Waddell Reference Waddell2005). Within this scholarly framework, archaeological artefacts and monuments were essentially seen as ‘inactive’ and ‘dead’, relating as they did to the distant past and now vanished societies. By contrast, for the wider non-literate rural farming population of Ireland, much of this same archaeological material was understood as evidence of a supernatural race of beings that co-existed with humans. Artefacts and monuments were ‘active’ and pertained to an existing (albeit supernatural) population. Within folk tradition, archaeological artefacts were not for display and study, but possessed real curative properties that had the potential to safeguard livestock and the home. These artefacts did not belong to long-gone cultures, but to the ever-present sí.

The earliest documentary reference to the sí dates to the seventh century ad, though by that time it was already an archaic term (Koch & Carey Reference Koch and Carey1995, 198; Thompson Reference Thompson2004, 351–2). The term sí can refer to the hills or prehistoric mounds that were inhabited by supernatural beings, but more commonly refers to the actual supernatural beings themselves (MacRitchie Reference MacRitchie1893, 367–70) and to the peaceful and prosperous quality of life in the Otherworld (Ó Cathasaigh Reference Ó Cathasaigh1977/8, 140). The sí were known by a wide variety of names, including na daoine maithe [the good people], na daoine uaisle [the gentry], na daoine beaga [the little people], an sluagh sídhe [the fairy host], bunadh na gcnoc [people of the hills], or simply ‘them’, as it was unlucky to call fairies by their name (Mac Neill Reference Mac Neill, Ó hEochaidh, Mac Neill and Ó Catháin1977, 26–7; Ó Súilleabháin Reference Ó Súilleabháin1970 [1942], 450–51; uí Ógáin & Sherlock Reference uí Ógáin and Sherlock2012, 9). As English became the dominant language of Ireland from the eighteenth century, the Irish nomenclature was replaced by the word ‘fairy’, though this is not an accurate approximation, particularly considering the modern popular meanings of the word. Traditionally, several explanations were provided as to the origin of the sí. They were usually believed to be ‘fallen angels’ who had been cast out of heaven by God and lived amongst humans in the hope that they would some day return to heaven (Curtin Reference Curtin1895, 42; Ó Súilleabháin Reference Ó Súilleabháin1970 [1942], 451). Some stayed in the air, others went to land, and more inhabited the sea (Ó hEochaidh et al. Reference Ó hEochaidh, Neill and Ó Catháin1977, 35). These fallen angels were ‘not good enough to be saved, nor bad enough to be lost’, placing them very much in the liminal zone (Yeats Reference Yeats2004 [1888], 11). The sí also bear a remarkable similarity to the Tuatha Dé Danann of early Irish literature—the last supernatural tribe to inhabit Ireland before being conquered by the mortal Milesians, after which they retreated underground (MacRitchie Reference MacRitchie1893, 367–70; Ó Cathasaigh Reference Ó Cathasaigh1977/8, 140). However, a connection between the two is rarely, if ever, made in oral tradition. Ó Súilleabháin (Reference Ó Súilleabháin1970 [1942], 450–51) also notes that some of the sí were considered to be deceased humans, and that it is ‘very difficult to draw a clear line of demarcation between the kingdom of the dead and the fairy world’. Ó Giolláin (Reference Ó Giolláin and Narváez1991) has argued that fairy belief in Ireland was a central part of popular religion that co-existed with the official religion of Christianity.

The ‘good people’ inhabited an invisible preternatural realm that co-existed alongside the world of mortals (uí Ógáin & Sherlock Reference uí Ógáin and Sherlock2012, 8). They were ‘everywhere around us’ and had ‘the power to go in every place’ (Gregory Reference Gregory1992 [1920], 65). Folklore collector Jeremiah Curtin (Reference Curtin1895, 108) remarked: ‘I find a remarkable freedom of intercourse between the visible and the unseen worlds, between what we call the dead and the living—a certain intimate communion between what has been and what is’. They might appear individually or in their ‘hundreds and thousands’ (Gregory Reference Gregory1992 [1920], 79). The sí were normally invisible, though they lived parallel lives to humans: they kept cows; enjoyed whiskey, hurling, Gaelic football, music, singing and dancing; liked gold, milk and tobacco; and hated iron, fire, salt, urine and Christianity (Bourke Reference Bourke1999, 28; Mac Neill Reference Mac Neill, Ó hEochaidh, Mac Neill and Ó Catháin1977; Ó Súilleabháin Reference Ó Súilleabháin1970 [1942], 450–79). Accounts vary as to their size: they could be larger than humans, smaller, or of equal stature. In one account from Co. Donegal, male fairies were described as wearing blue britches and red caps, while their female counterparts wore green dresses; they were all about 0.75 m in height (Ó hEochaidh et al. Reference Ó hEochaidh, Neill and Ó Catháin1977, 37). The fairies carried out a similar range of domestic and agricultural activities as undertaken by humans. They could assume the appearance of an animal, and hares in particular were often considered fairies in disguise (Danaher Reference Danaher1972, 110). There was plentiful evidence of the existence of the sí in the human world including unexplained maladies, accidents, spoiled food, poor harvests and ‘bad luck’ (Ó Giolláin Reference Ó Giolláin and Narváez1991). Farm produce and farm animals were constantly under threat from fairy activities and various practices and folk magic were necessary to avert interference. Milk and butter, for instance, were often stolen or spoiled by the fairies. Fairies could milk a cow and therefore ‘take’ her, causing her to die or stop producing milk (Ó Súilleabháin Reference Ó Súilleabháin1970 [1942], 457–8). Evidence of malevolent (and occasionally benevolent) sí activities were regularly noted by communities and recounted in oral tradition, particularly if humans interfered with a fairy place, such as a prehistoric burial cairn, or an early medieval ringfort settlement. One of the greatest threats posed by the fairies was their tendency to kidnap (‘take’) a human infant or adult (particularly marriageable young women), leaving an ugly, contrary changeling in its place. The changeling would pine away and die, leaving the human forever in the power of the fairies (Danaher Reference Danaher1972, 122). Childbirth was a particularly vulnerable time for mother and baby, with an increased chance of being taken (Ó hEochaidh et al. Reference Ó hEochaidh, Neill and Ó Catháin1977, 30). Blindness in adults was also often attributed to the sí, usually after the individual had glimpsed the fairy world (e.g. Curtin Reference Curtin1895, 42–5). Many of the themes in sí stories revolve around life events that evoke great anxiety and grief: the loss of livestock with the resultant threat of poverty and/or eviction; the death of a child; any untimely or unusual death; inexplicable illnesses in adults (the symptoms of which would now often suggest mental health issues); and mental or physical disabilities in young children that only became apparent as they grew older. The sí provided an explanation for difficult life events, calamities and experiences and in many ways represented the daily anxieties experienced by the millions of poor tenant farmers and labourers in Ireland, who were never too far removed from the prospect of starvation, poverty and eviction. Other fairy stories, however, reflect ‘wishful thinking’—prolific cows, food mysteriously appearing, purses never without money, magical powers acquired, or erotic love between a fairy woman and mortal man (Mac Neill Reference Mac Neill, Ó hEochaidh, Mac Neill and Ó Catháin1977, 22).

The archaeology of the sí

The sí were not simply a mental concept or construct: physical evidence of this race abounded. Placenames, the physical landscape, topographical features and archaeological monuments supported the belief in the closeness of the fairy realm to the human world (Ó Súilleabháin Reference Ó Súilleabháin1970 [1942], 465–69; uí Ógáin & Sherlock Reference uí Ógáin and Sherlock2012, 9). Certain archaeological monuments, for instance, were strongly associated with the sí—particularly the early medieval ringfort (Fig. 2).

Figure 2. An early medieval ringfort at Abbeytown, Co. Sligo Archaeologically known as ‘Ringfort SL020-159----’, the site is known locally as a fairy fort. A man who fenced off the monument and put his corn inside found the whole crop destroyed the following day. Another farmer put his cow in the fort and that night a local woman saw three fairies digging the cow's grave; the cow died the following day (http://www.duchas.ie/en/cbes/4701716/4695393). A more recent folktale tells of a man who developed a sore arm after digging in the ringfort. There is also a story of a man who could not find his way out of the fort and so turned his jacket inside out, put it on, and immediately found himself outside the fort (Margaret Savage pers. comm., September 2017). (Photograph: James Bonsall.)

Ringforts are the type site of the Irish early medieval period, which is defined by the adoption of Christianity c. ad 400 and ends with the Anglo-Norman invasion of ad 1169. During the early medieval period, Gaelic Ireland was characterized by dispersed rural settlement; a complete absence of urban centres until the arrival of the Vikings; Irish (Gaeilge) was the language spoken; and Christianity was the dominant religion. Politically, the country was divided into approximately 150 petty kingdoms known as túath, each ruled by its own king (O'Sullivan et al. Reference O'Sullivan, McCormick, Kerr and Harney2014). Approximately 45,000 ringfort settlements have been documented across the Irish landscape. These comprise enclosed farmsteads of earthen and/or stone construction that date largely to between the sixth and tenth centuries ad. Excavations have revealed circular houses, industrial areas (iron working, spinning, bone working), hearths, storage spaces (souterrains) and animal pens inside the circular banks (Stout Reference Stout1997). The vast majority of ringforts had fallen out of use by the end of the twelfth century, following the Anglo-Norman invasion. For the farming population of post-medieval and modern Ireland, ringforts were strongly associated with the fairies and were more commonly referred to as ‘fairy forts’. Clearly this attribution cannot be older than, at most, 800 years (i.e. from the twelfth century onwards). These monuments were where the fairies—not humans—resided. Many were individually named for their supernatural associations, such as Lisfearbegnagommaun ringfort, Co. Clare, which is an Anglicization of Lios fear beag na gcomáin, meaning ‘the fort of the little men [playing] hurling’ (Westropp Reference Westropp2000 [1910], 3). Accounts are numerous of individuals who were struck with misfortune after attempting to destroy a ringfort, cut down a lone bush growing therein, remove earth, stones or sticks from the interior, or plant crops there (Ó Súilleabháin Reference Ó Súilleabháin1970 [1942], 436). Venturing into a ringfort was generally discouraged and was particularly ominous for pregnant women (Lenihan Reference Lenihan2003, 136–7). Houses or farm buildings should not be constructed between ringforts, nor on the route of a fairy path (Lenihan Reference Lenihan2003, 146ff).

Throughout the eighteenth, nineteenth and twentieth centuries these beliefs (often disparagingly referred to as ‘superstitions’ by antiquarians)—far more than the archaeological legislation—served to prevent the destruction of thousands of archaeological monuments. Even today, farmers, machine contractors and landowners will sometimes say that they would not destroy a ringfort because of a belief that it would bring bad luck—rather than because this is illegal under the National Monuments Act of 1930! I have personally heard several such cases over the past 20 years. As recently as 2017, an Irish independent politician and Teachta Dála [equivalent of an English MP] for the Kerry constituency, Danny Healy-Rae (b. 1954), claimed that the reason the N22, a relatively new national primary road in the south of Ireland, repeatedly collapsed despite having been repaired numerous times was because ‘. . . There are numerous fairy forts in that area . . . I know that they [the road problems and the ringforts] are linked. Anyone that tampered with them [ringforts] back over the years paid a high price and had bad luck . . . there was something in these places you shouldn't touch’ (Irish Times 2017). Though his comments were widely ridiculed in the national press, he did not retract his statements. In fact, at a Kerry County Council meeting 10 years previously, in 2007, Healy-Rae had questioned the same problem with the N22 road: ‘Is it fairies at work?’ (Irish Times 2017). Similarly, when business tycoon and billionaire Séan Quinn declared bankruptcy as a result of risky bank and business investments, some believed his misfortune was due to the fact that one of his developments involved the removal of a wedge tomb from its original location and its reinstatement on the grounds of one of his properties, the Slieve Russell Hotel, Co. Cavan, in 1992 (Independent.ie 2011). The belief persisted and was reported in a national newspaper in 2011, despite the fact that this Early Bronze Age megalithic tomb was archaeologically excavated, and the dismantling and reconstruction was also carried out by a licensed archaeologist. A local publican was reported as stating: ‘that tomb should never have been moved . . . There would be a lot of people who would think you could never have any luck after moving an ancient tombstone’ (Independent.ie 2011).

A wide range of traditional folk practices existed for engaging appropriately with the early medieval ringfort. It was considered bad luck, for example, to throw dirty water or dust in the direction of a ringfort, as this was an insult to the fairies (Westropp Reference Westropp2000 [1911], 45). One way to appease the sí was to pour cow beestings (the first milk given by a cow after calving) into a ringfort, which also served to prevent the fairies from stealing the cow (Bourke Reference Bourke1999, 79; Evans Reference Evans1957, 304). Folktales abound of cows that wandered into a ringfort and thereafter stopped producing milk, or became ill—a consequence of fairy mischief, or because the fairy was milking the cow (e.g. Curtin Reference Curtin1895, 121–6; Windele Reference Windele1865, 322). May Eve (30 April) and Samhain (31 October) were nights of increased preternatural activity when fairies became involved in human activities and vice versa: ‘almost anything might be expected to happen’ (Danaher Reference Danaher1972, 109; uí Ógáin & Sherlock Reference uí Ógáin and Sherlock2012, 9; Windele Reference Windele1865, 323). On these nights the deceased and the sí were sometimes seen in ringforts (Danaher Reference Danaher1972, 203). One woman linked the death of her children to fairy activity and a nearby ringfort: ‘it's in that forth [sic] my five children are that were swept from me’ (Gregory Reference Gregory1992 [1920], 264). If a ‘taken’ human was brought to a ringfort and spent more than a year and a day there, s/he would be forever condemned to live with the fairies (uí Ógáin & Sherlock Reference uí Ógáin and Sherlock2012, 51). In 1678, a London schoolmaster who had moved to Co. Wicklow reported that he had been abducted by the fairies for having spoken openly about an earlier abduction (Sneddon Reference Sneddon2015, 15). A folktale recorded in 1920 described how a woman who had heard fairy music issuing from a ringfort at Derrygorman, Co. Kerry, died shortly afterwards; another woman died while cutting down bushes in a ringfort in Tullycanna, Co. Wexford (uí Ógáin & Sherlock Reference uí Ógáin and Sherlock2012, 73, 97).

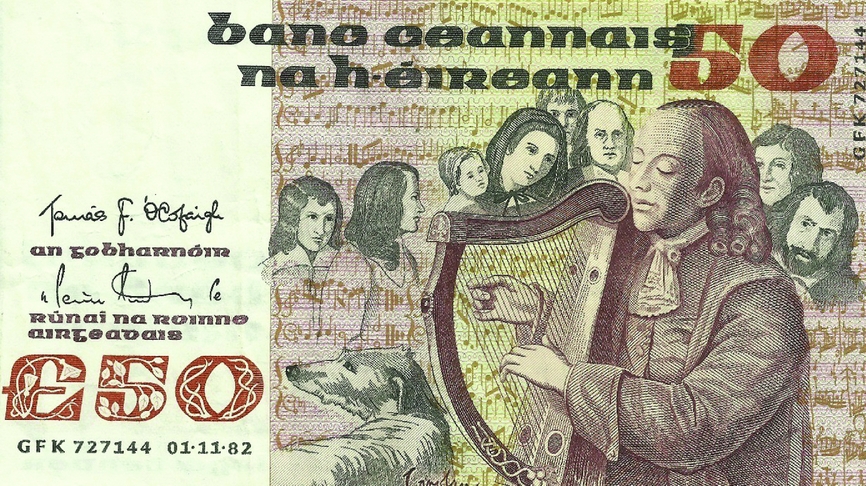

Some sí intervention was positive. Fairies might drive cattle home for a childless couple; help a man with his harvest; help a woman with her spinning; light a fire for a poitín maker; or come to the aid of runaway lovers (Ó Súilleabháin Reference Ó Súilleabháin1970 [1942], 461). They could be charitable, particularly towards orphans, leaving them a cow to provide milk until they had been reared (Ó hEochaidh et al. Reference Ó hEochaidh, Neill and Ó Catháin1977, 30). Highly skilled musicians were often credited with receiving their gift from the fairies. The talent of renowned blind harpist Turlough O'Carolan (1670–1738) was believed to derive from the lengthy periods of time he spent in a ringfort near his home (Fig. 3). His most famous composition, Sí Bheag, Sí Mhór [Small fairy mound, Large fairy mound], is named for two Neolithic passage tombs in Co. Leitrim that were located near the residence of one of his patrons, Squire George Reynolds (uí Ógáin & Sherlock Reference uí Ógáin and Sherlock2012, 11). It was also widely believed that the fairies bestowed fiddle player Michael Coleman (1891–1947) with his exceptional musical talent in a field that contained a ringfort (uí Ógáin & Sherlock Reference uí Ógáin and Sherlock2012, 32).

Figure 3. Blind harpist Turlough O'Carolan (1670–1738), who is believed to have received his exceptional musical talent from the fairies, on an Irish £50 bank note from 1982.

The early medieval ringfort was not the only archaeological monument type to represent physical evidence of the fairies. Less commonly, Neolithic megalithic tombs, Bronze Age burial cairns and medieval castles were occasionally believed to be inhabited by the sí. In early medieval and medieval manuscripts (eighth–seventeenth centuries), passage tombs are known as sí places, including Newgrange and other passage tombs within the Boyne Valley complex, Co. Meath (Carey Reference Carey and Mahon1990; Thompson Reference Thompson2004). In recent centuries, however, megalithic tombs are rarely linked to the fairies. At the other end of the chronological spectrum, medieval castles can sometimes be occupied by the sí. One folktale relates how a mortal woman was taken by the fairies to the fifteenth-century Rahinnane Castle, Co. Kerry (Fig. 4) to feed a fairy child soon after her own baby died; she was later transferred to the nearby Lismore ringfort. The fairies left in her place a sickly woman with a swollen foot, who died a year later (Curtin Reference Curtin1895, 23–8). It may be significant that this castle had been constructed on a large bivallate ringfort.

Figure 4. The fifteenth-century Rahinnane Castle, Co. Kerry, where a kidnapped mortal woman was taken to feed a fairy infant. Remnants of the early medieval ringfort on which the castle was constructed are visible. (Photograph: Marion Dowd.)

Certain natural features in the landscape were also believed to be sí places; thus, the fairies had not only their own archaeology, but also their own geography. Many mountains and hills were named for the fairies, including Knocknashee (Cnoc na sí – the Hill of the Fairies), Co. Sligo, and Knockainey (Cnoc Áine – the Hill of Áine, a fairy queen), Co. Limerick. Caves were sometimes inhabited by the sí, or fairy music could be heard issuing from them (Dowd Reference Dowd2015, 249ff). One of the outer chambers of Dunmore Cave, Co. Kilkenny, is known as the Fairies’ Floor due to a belief that the sí used this area for dancing (Dunnington & Coleman Reference Dunnington and Coleman1950, 19). Erratics and prominent boulders were sometimes considered fairy places: for instance, they danced on a natural boulder at Camas, Co. Galway (uí Ógáin & Sherlock Reference uí Ógáin and Sherlock2012, 112). A solitary bush or tree (‘a fairy bush’), usually hawthorn, was often linked to the fairies and should not be trimmed or cut down; failure to observe this could result in death, amputation or blindness (uí Ógáin & Sherlock Reference uí Ógáin and Sherlock2012, 107). As recently as 1999, the proposed route of a bypass motorway between the towns of Newmarket-on-Fergus and Ennis in Co. Clare had to be modified because of opposition to the destruction of a sceach—a fairy bush; the story received international media attention (Irish Times 1999; Lenihan Reference Lenihan2003, 13–44).

Artefacts of the sí

Archaeological artefacts could also provide physical evidence of the existence of the fairies. Antiquarian and folklore accounts are replete with references to elf-stones, elf-shots, elf darts, fairy darts, saighead [fairy dart] and gae síe [dart or spear of the sí]. These interchangeable terms applied to natural pebbles, unusual stones, as well as prehistoric lithics (in particular, Neolithic and Bronze Age arrowheads) (Evans Reference Evans1957, 304; Logan Reference Logan1981, 165–6). Ó Súilleabháin (Reference Ó Súilleabháin1970 [1942], 459) also notes that ‘elf-shot’ could include thimbles or pieces of bone. No distinction was made between the efficacy of archaeological artefacts versus natural pebbles if they were considered elf-stones/darts: these were all equally powerful supernatural items. Archaeological artefacts may have been a minority component of fairy assemblages, as natural pebbles were far more common. It is usually not possible to discern from folkloric and antiquarian references whether the elf-stones in question comprised archaeological or natural objects, or a combination of both. This is exemplified in the two case studies described below: one collection of elf-stones consists exclusively of colourful natural pebbles, while the second includes natural pebbles, prehistoric lithics and a post-medieval gunflint. Essentially, any distinctive or unusual items that were encountered—whether geological or archaeological—had the potential to be interpreted as pertaining to the sí and therefore possessing supernatural properties.

In a letter dated 1684, a Church of Ireland clergyman, Rev. John Keogh, mentioned a woman in Co. Roscommon who possessed a fairy dart that she used to ensure the safe delivery of babies (Sneddon Reference Sneddon2015, 15). These artefacts were more commonly used with animals, however. Late medieval medical manuscripts contain many references to the bewitching of cattle (mille ba) by elf-shot (urchar millte), including an account taken from a manuscript that had been in the possession of physician Eóin Ó Callannáin in 1692 (Kelly Reference Kelly2000, 175, 218). Andrew MacCurtin, writing around 1730, mentioned ‘the stroke of a fairy’ in one of his poems (Westropp Reference Westropp2000 [1910], 14). Walker (Reference Walker1788, 180) makes another early reference to elf darts. The prevailing belief was that the sí shot arrows, darts or other objects at cattle, and occasionally humans, resulting in illness or death. The animal or person could then be acquired by the fairies and carried into the supernatural realm: s/he was said to be ‘taken’. In humans, the ‘fairy stroke’ (also known as fairy blast, elf-shot, poc sídhe) could manifest as partial paralysis, sore eyes, skin trouble, a sudden fall or injury, unexplained lameness, deafness, loss of speech, fainting or swelling (Ó Súilleabháin Reference Ó Súilleabháin1970 [1942], 478–9; Danaher Reference Danaher1972, 124). Many illnesses in livestock were interpreted as evidence that an animal had been ‘elf-shot’. Lesions provided proof that a fairy dart had pierced the skin of an animal and foretold a worsening condition or death (Evans Reference Evans1957, 304; Ó hÓgáin Reference Ó hÓgáin2002, 56–7, 66).

The ‘fairy stroke’ could be counteracted by certain ritual acts, charms and prayers (Ó Súilleabháin Reference Ó Súilleabháin1970 [1942], 479). Indeed, the same elf-stones that had caused illness also had the potential to provide a cure. In Blacksod Bay, Co. Mayo, if an animal was shot a ‘wise man’ passed a ‘fairy dart’ three times over and under the beast while reciting suitable incantations (Westropp Reference Westropp1918, 318). Elsewhere, an ailing animal could be restored to good health by drinking water into which a prehistoric arrowhead had been placed (Logan Reference Logan1981, 165–6). A Neolithic flint hollow scraper, known by its owner as an ‘elf-stone’ (Fig. 5a), was used at Coragh, Co. Cavan, in the following manner: ‘After a cow had calved, for the first three milkings the farmer put into the pail this elf-stone and a sixpence. He also plucked ten whitethorns, threw the tenth away, and put the nine into the pail. This was to save the milk from being bewitched’ (Herring Reference Herring1936, 99). An Early Bronze Age barbed and tanged arrowhead from Portglenone, Co. Antrim, was similarly used in the nineteenth century to cure various cattle maladies (Penney Reference Penney1976, 73). To restore human health, a saighead was placed in a tumbler which was then filled with water and drunk by the patient. Health was restored if the fairies had been responsible for the illness, but if ill-health continued, this indicated that the malaise was not fairy-related (Mooney Reference Mooney1887, 143). Knowles (Reference Knowles1903, 52) remarked on the discolouration caused to a Neolithic leaf-shaped arrowhead by repeatedly boiling it in ‘cow's drinks’ to cure animals that had been elf-shot (Fig. 5b).

Figure 5. (a) Neolithic flint hollow scraper or elf-stone from Coragh, Co. Cavan, which was used to prevent milk from being bewitched (Herring Reference Herring1936, 98); (b) Neolithic leaf-shaped flint arrowhead used to cure animals that had been elf-shot (Knowles Reference Knowles1903, pl. IX no. 22); (c) Neolithic leaf-shaped flint arrowhead that was used in the late nineteenth century (probably in Co. Antrim) for cattle curing by boiling it in water together with soot, soil, salt and meal (Buick Reference Buick1895, 44, fig. 1).

In southwest Donegal, a variety of cures were recorded by folklore collector Séan Ó hEochaidh to counteract the magic of fairy darts (Ó hEochaidh et al. Reference Ó hEochaidh, Neill and Ó Catháin1977, 79–83). These darts were believed to have been shot at cattle from the air or from the hills by the fairies. The cure was obtained by placing the ‘dart’ in water and giving the ill animal a drink. Another cure involved men passing a holy candle around the body of the ailing animal in a prescribed fashion, while making the sign of the cross. It was believed that if a fairy dart entered a cow's heart she would die, but if it hit any other part of her body she could be cured if two people put their fingers into the hole in her flesh.

In Ireland and Scotland, natural quartz crystals, as well as worked quartz or agate beads and spheres, were also employed to ward off or cure diseases, particularly those afflicting cattle. These were often known as ‘murrain stones’—‘murrain’ meaning an infectious disease that affected cattle (Atkinson Reference Atkinson1875; Frazer Reference Frazer1879/88). Part of the significance of quartz in Irish folk medicine and popular ritual was that it is closely associated with Neolithic passage tombs, regarded in folk tradition as places of the sí (Thompson Reference Thompson2005, 111). In some parts of the country quartz was considered ‘fairy stones’ and quartz pebbles were also used by fairy doctors (Thompson Reference Thompson2005, 115, 116). Using quartz in the construction of a house or outbuilding was generally considered forbidden and unlucky because of its close association with the fairies (Ó hEochaidh et al. Reference Ó hEochaidh, Neill and Ó Catháin1977, 99).

Liminal individuals: the folk healer and keeper of elf darts

The economy and society of Ireland has been, until relatively recently, predominantly agricultural and rural in nature. For instance, in 1841 less than 15 per cent of the population lived in urban centres (Evans Reference Evans1957, 8). The rural population increased dramatically during the nineteenth century. Immediately prior to the Great Famine (1845–1852), an estimated 8.5 million people lived on the island, compared to just 3 million in 1700 and 1.5 million in 1600 (Aalen et al. Reference Aalen, Whelan and Stout1997, 23). The growing demographic, coupled with increased agricultural activities, led to more intensified use of land. Families and communities were forced into areas of marginal ground, which meant that many archaeological sites and landscapes that had remained untouched since prehistoric and early historic times were rediscovered (Champion & Cooney Reference Champion, Cooney, Gazin Schwartz and Holtorf1999, 202). A further consequence is that the incidence of artefact discovery increased. In the absence of any detailed documentation, how people came upon prehistoric artefacts such as those mentioned in this paper is not known. Presumably some or many were encountered in the course of agricultural works such as land reclamation, ploughing, river dredging, turf cutting, gardening, etc. Others may have been revealed in the course of the known or unknown destruction of archaeological sites. These objects would have been distinctively ‘exotic’ or ‘foreign’ in post-medieval and modern Ireland, understandably leading to an interpretation that they pertained to ‘other’ people, places and times. In contrast, the types of artefacts that might be discovered in a fairy fort (early medieval ringfort) would have been recogniszable and familiar—iron knives, shears, sickles, spindle whorls, whetstones, etc. Similar items were still in use in nineteenth- and twentieth-century farmsteads, though some early medieval items were seen as miniature versions of objects used by humans. For instance, at the turn of the nineteenth century, Westropp (Reference Westropp2000 [1911], 39) recorded a belief from Co. Clare that stone spindle whorls were rotary quernstones of the fairies. Unusual prehistoric artefacts and unusual geological formations, however, demanded explanation, thus allowing them to be incorporated in meaningful ways into the everyday lives of farming communities. Enter the folk healer.

The folk healer was also known as a wise woman (mná feasa), herb doctor, fairy doctor, fairy man, handy man, gentle doctor, cow doctor or quack in traditional Irish society (Ó Súilleabháin Reference Ó Súilleabháin1970 [1942], 308, 383, 388). S/he was a powerful man or woman who sometimes had an understanding of, if not direct communication with, the sí (see, for example, Sneddon Reference Sneddon2015, 36–42, 129–30). These individuals were held in great esteem within the community, particularly amongst the poor who could not afford to pay a doctor or vet. Being a folk healer was a valid profession and could also be a source of income, though often a fee was not necessary. Fairy doctors did not learn their healing knowledge, it was ‘given to them’—often when least expected—or it may have been inherited from a parent, or bequeathed by another healer (Curtin Reference Curtin1895, 87; Seymour Reference Seymour1913, 244). Traditional healers often came from a particular family, or had a particular surname, and included individuals born at certain times/days or born with a caul (Ó Súilleabháin Reference Ó Súilleabháin1970 [1942], 379). Healers were sometimes described as being ‘away’, meaning ‘away with the fairies’. According to Bourke (Reference Bourke1999, 59), ‘Eccentric, deviant, or reclusive individuals—or people with mental or physical disabilities—were often said to be “in the fairies”, or to have spent time “away” among them’. Fairy doctors were sometimes people that the fairies had kept for several years—when they were returned to the mortal world, they brought with them the gift of healing. A connection to the fairies gave the healer prestige and, to a certain extent, protection and a place in society. Meehan (Reference Meehan1906, 200) described three fairy doctors he knew: ‘you would pick them out among a thousand as something “uncanny”. They are very old, very “weathered” and wrinkled. One is lame; another is bent and bowed with years.’

Different folk healers used different medical accoutrements and methods. Some possessed a supply of elf-stones (prehistoric lithics, arrowheads and/or natural pebbles) and could produce a fairy dart/prehistoric arrowhead from the flank of the beast to explain an ailment (Evans Reference Evans1957, 304; Mason Reference Mason1928, 224; Penney Reference Penney1976, 73; Wood-Martin Reference Wood-Martin1902, 41–2). A traditional healer in Co. Leitrim had in his elf-bag four small flint arrowheads that had been found by an ancestor ‘near a fort’ (Meehan Reference Meehan1906, 202). An old woman in possession of a saighead was regarded with ‘much veneration’ (Mooney Reference Mooney1887, 143). Wilde (Reference Wilde1887, 96) documented an ‘eminent fairy-woman’ who ‘made the cure of fairy darts her speciality . . . and was generally successful’ in her treatment of human illness. She did not seek payment until the patient was cured and the elf-shot retrieved. Westropp (Reference Westropp1918, 317) recorded that ‘Cattle are shot with stones and can only be cured by a “fairy dart” or ancient stone arrowhead. These objects are kept in numerous wrappings by every properly qualified “fairy doctor”, who rub them on the sick beasts with appropriate charms or prayers, the latter kept as professional secrets’. In counties Mayo and Sligo it was recorded that:

fairy doctors . . . usually possess elf-bags, containing in one recent case three or four ancient flint arrow heads, a piece of silver with a cross on it, and three pieces of copper. Some have seven or eight flints, though only one was used in the disenchanting acts. Cows were also treated with water from three boundary streams, ladies-mantle juice [Alchemilla] and salt; the coins and one arrow head being dipped in it. It was given in three draughts to the cow, the rest poured on her back or into her ears. (Westropp Reference Westropp1918, 319)

As the two case studies below illustrate, elf-stones were not owned just by folk healers. Households sometimes had their own personal collection, while others were collectively owned by a community. Antiquarian collector William Knowles (Reference Knowles1885, 104) encountered individuals who owned ‘a few flint antiquities’ that they refused to sell because they made more money renting them out to neighbours for the purpose of curing cattle. One antiquarian collector acquired a Neolithic flint arrowhead (Fig. 5c) that had been used for cattle curing from an old woman on her deathbed. It had been handed down to her from her mother; to effect the cure, the arrowhead was boiled in water together with soot, soil, salt and meal (Buick Reference Buick1895, 61). An unpublished letter in the National Museum of Ireland (NMI), dated 22 April 1967, attempted to explain the discovery of prehistoric lithics at Kingscourt, Co. Cavan: ‘The flints were found in an old half-rotten bag between the ceiling and roof of a house being demolished in Kingscourt. I suspect the collection belonged to a quack cattle doctor, being in fact his “elf-stones” which he had hidden from the rest of the family.’ One of the artefacts, a small flint blade, was acquired by the NMI.

Two case-studies

In the course of researching this topic, two previously unpublished collections of elf darts were brought to my attention, both from the northwest of Ireland. These contrasting assemblages provide valuable insights into this folk magic practice.

The Tawnywaddyduff saigheads, Co. Mayo (Fig. 6) Informant: Seamus Caulfield (Professor Emeritus of Archaeology, University College Dublin)

This assemblage was given to Prof. Seamus Caulfield's father, Mr Patrick Caulfield, in the 1970s by Mr David Kelly of Tawnywaddyduff, Co. Mayo. Known as the ‘Tawnywaddyduff saigheads’, a late nineteenth-century account explains that the ‘saighead . . . is a fairy dart which has been shot at some man or animal, and thus lost’ (Mooney Reference Mooney1887, 143). The Tawnywaddyduff saigheads comprise 15 flint and chert lithics, almost all of which have been struck and some are retouched (Fig. 6). The assemblage includes a Neolithic flint hollow scraper, two convex scrapers of Neolithic or Bronze Age date, a series of complete and broken blades and flakes of Neolithic and/or Bronze Age date, waste flakes, a chunk of flint that appears to be unworked, and a gunflint dating to the seventeenth–nineteenth centuries. This assemblage was used to cure cattle that had been hit by a fairy saighead (or, cows that became bloated from eating too much fresh grass). The remedy was achieved by wrapping the saigheads in a rag, placing the bundle in a bucket of water, then getting the cow to drink water from the bucket. The Tawnywaddyduff saigheads were owned by the community rather than by a single individual: when a farmer needed the saigheads he sought out the neighbour who had last used them, then took possession of them and looked after them until they were required by another farmer. This assemblage had fallen out of active use by the 1970s, when they were given to Mr P. Caulfield. Interestingly, a complex of prehistoric sites is located in and around Tawnywaddyduff townland and includes two Neolithic court tombs, an unclassified megalithic tomb, a standing stone and a Late Bronze Age stone row. It is likely that the saigheads were originally picked up by farmers working the land in and around these monuments. Flint artefacts are relatively rare in this part of Ireland and thus the saigheads would have been quite distinctive and ‘different’ when encountered by people. It is also significant that the assemblage contains archaeological material of various dates spanning the Neolithic through to post-medieval centuries—artefacts that were all considered of equal value in averting sí interference with livestock.

Figure 6. The Tawnywaddyduff saigheads, Co. Mayo. Top row includes a Neolithic hollow scraper and a post-medieval gunflint. (Photograph: Marion Dowd.)

Figure 7. The Mullaghmore elf-stones could cure cattle by placing the pebbles in water that had been taken from a mearing stream and then giving the water to the ailing animal. Now in the possession of Mr Joe Mc Gowan, they were last used for curing c. 2007. (Photograph: Marion Dowd.)

The Mullaghmore elf-stones, Co. Sligo (Fig. 7) Informant: Joe Mc Gowan (folklore collector)

The Mullaghmore elf-stones consist of 19 natural rounded pebbles including flint, quartz and granite stones. They have not been modified, worked or engraved in any way. This is one of two collections of elf-stones known to Mr Joe Mc Gowan from the village of Mullaghmore, Co. Sligo; as a child, he also discovered a third set hidden in his father's byre. The Mullaghmore elf-stones were last used c. 2007 by a farmer from Rossnowlagh, Co. Donegal (34 km to the northeast) who had a sick bull. The cure was obtained by placing the elf-stones, together with a silver coin, into water that had been taken from a specific three mearing stream in Mullaghmore [that is, water taken from a stream or drain where the boundaries of three townlands or farms meet (Danaher Reference Danaher1972, 110; Meehan Reference Meehan1906, 207)]. The water was given to the ailing animal to drink, and the elf-stones were then passed three times around the stomach of the beast. Afterwards, the animal was measured from head to tail three times using a ‘finger to elbow’ unit of measurement. If the resultant three measurements were the same, the animal would be cured. Any inconsistency in the measurements, however, implied continuing ill health or death. Mr Mc Gowan's general understanding of elf-stones, as passed down to him from the previous generation, was that the fairies played with them in the fields at night, throwing them to one another or firing them from slings. In the process, the fairies sometimes accidentally hit a cow. The elf-shot animal then became ill and/or collapsed and could not get up. A set of elf-stones could be used to affect the cure. Typically, these stones were picked up by farmers in fields during ploughing or cultivation.

Housing the supernatural: thunderstones

Traditionally, a wide range of rituals were observed to protect the vernacular house in Ireland. Rituals existed with regard to choosing the ‘right’ location at which to build a house; the appropriate stones for construction (usually, for instance, white stones should be avoided); and the lucky day/time to start building a house (Ó Súilleabháin Reference Ó Súilleabháin1970 [1942], 15). Luck and prosperity could be achieved by placing a coin, bird or animal under the house foundation stone; hanging objects in the chimney, such as part of a cow's leg; inserting objects into the house roof, including herbs, animal legs, cow dung, eggs or meat; and by displaying certain objects inside or outside the house, including ‘freak’ eggs, iron, a human caul, an otter skin, or ashes from special fires (Ó Súilleabháin Reference Ó Súilleabháin1970 [1942], 8–15).

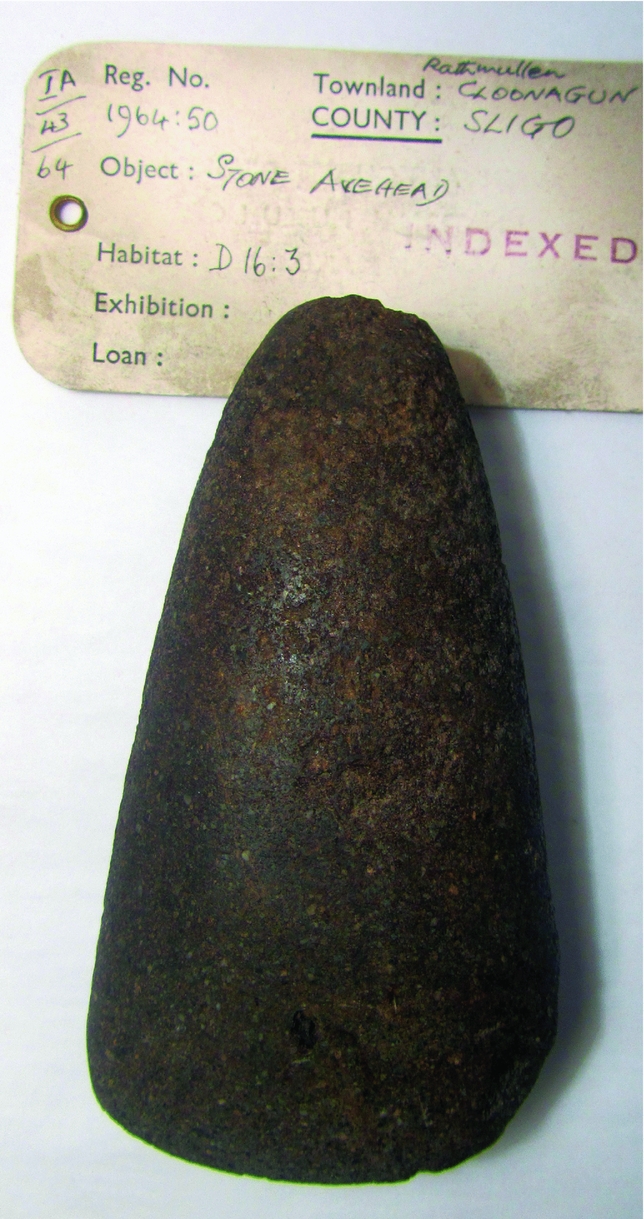

Stone axes were another category of prehistoric artefact that sometimes assumed a supernatural role in post-medieval and modern Ireland centring on a belief that they were cast into the earth by lightning during thunderstorms, thus leading to the names thunderbolts, thunder-axes and thunderstones (Penney Reference Penney1976, 70). This folk belief was not confined to Ireland, but has been noted in many parts of northwest Europe and can be traced to ancient Greece and Rome (Blinkenberg Reference Blinkenberg1911; Johanson Reference Johanson2009; Merrifield Reference Merrifield1987, 10). In Ireland, the thunderbolt could protect the house from lightening and was usually placed in a relatively secret part of the house. Penney (Reference Penney1976, 70–71) has thus interpreted the discovery of prehistoric stone axes in the wall of a dwelling house at Maynooth, Co. Kildare; on top of an internal wall in a house at Tinnakilly Upper, Co. Wicklow; incorporated into a wall surrounding St Flannan's Catholic church, Killaloe, Co. Clare; built into a stable wall at Lough Eyes, Co. Fermanagh; and in the wall of an animal shed at Ballintogher, Co. Meath, as reflecting the curation of these items to protect the home from lightning or to bring good fortune. Further examples include two polished stone axes from Killamoat Upper, Co. Wicklow: one found under the flagstone of the main doorway of a house, and the second from a niche in the wall of a farm outhouse and calf house (Rynne Reference Rynne1964/5, 50, 52). My own research of unpublished files in the NMI has uncovered three further examples: a stone axe from under the cement floor of a horse stable at Newmarket-on-Fergus, Co. Clare; an axe immured in the wall of a cow shed at Cloonagun, Co. Sligo (Fig. 8); and a stone axe found lying in a farmyard at Carrickbanagher, Co. Sligo.

Figure 8. A prehistoric polished stone axe discovered c. 1964 incorporated into a drystone wall of a cow shed at Cloonagun, Co. Sligo. (Photograph: Marion Dowd.)

Penney (Reference Penney1976, 71–2) further argued that late prehistoric metalwork from similar find circumstances in vernacular houses and outhouses reflects a uniquely Irish departure from the thunderbolt tradition in protecting the home from lightning and/or as a general good luck charm. He refers to Early Bronze Age flat copper axes from the wall of a farm outhouse at Deerpark, Co. Donegal, from the thatched roof of a house at Ballyeaston, Co. Antrim, and from a font built into Aghaboe Abbey, Co. Laois; Late Bronze Age socketed spearheads from within a wall of a dwelling house at Derreenargan, Co. Roscommon, and the rafters of a farmhouse at Tullyskeherny, Co. Leitrim; a Late Bronze Age sword from the thatched roof of a house at Cloonkerry, Co. Mayo; and an Iron Age La Tène sword from a thatched roof of a dwelling at Cashel, Co. Sligo. I have discovered further examples from unpublished files in the NMI: an Early Bronze Age flat axe from an abandoned house at Derrynanagh, Co. Offaly (Fig. 9); an Early Bronze Age stone mould for a flat copper axe from a farm outhouse at Kilcronat, Co. Cork; a Middle/Late Bronze Age rapier from the thatched roof of a house at Ballykilduff, Co. Carlow; a Middle/Late Bronze Age dirk and an eighteenth- or nineteenth-century horn spoon found in a stone wall of a dwelling house at Mondooey Middle, Co. Donegal; and a Late Bronze Age socketed axehead found in a hole in the wall of an abandoned dwelling house at Oughtmama, Co. Clare (Fig. 10).

Figure 9. An Early Bronze Age decorated flat axe discovered in 1957 in a deserted house site at Derrynanagh, Co. Offaly. (Photograph: Marion Dowd.)

Figure 10. A Late Bronze Age socketed axehead found in 1955 protruding from a hole in the wall of a derelict dwelling house at Oughtmama, Co. Clare. (Photograph: Marion Dowd.)

The stone axes and prehistoric metalwork outlined above likely served a variety of apotropaic purposes, protecting the house from lightning, but also acting more generally as a charm to attract good fortune, repel ill health and misfortune, or avert fairy mischief and evil. The placement of animal bones, animal skulls and animal body parts was common in Ireland. Horse skulls, for instance, were considered lucky and were often buried beneath the floor, around the hearth, or at the main door of the house—such traditions are known from elsewhere in Europe (Davies Reference Davies, Boschung and Bremmer2015, 393–4; Donaldson Reference Donaldson1923, 77; Hukantaival Reference Hukantaival2016; Ó Súilleabháin Reference Ó Súilleabháin1945). A similar explanation may apply to a bronze ecclesiastical seal matrix of probable fifteenth-century date (which probably originated from the Dominican priory at Mullingar) that had been incorporated into the mud wall of a vernacular dwelling house at Gaulstown, Co. Meath (Ó Floinn Reference Ó Floinn1978/9). In England, the practice of incorporating shoes, animal skulls or bones, chickens or mummified cats into the walls, chimneys and roofs of houses was a common form of protective magic (Merrifield Reference Merrifield1987, 128–36). From England the tradition spread to Australia (Evans Reference Evans2010). These practices are relatively rare, but not unknown, in Ireland. Such an interpretation may similarly apply to the discovery of a ‘spiritual midden’ in a blocked-up oven of the nineteenth-century Coolbeg House, Co. Wicklow. The deposit included a pewter spoon dated to c. 1600, a shoe fragment, glass bottles, pottery sherds, bird bones and butchered animal bones (Kelly Reference Kelly2012). Similarly, in a timber-framed house constructed in Dublin in 1664, a child's leather shoe dated to c. 1800–1810 was found under the floorboards of one room, while a sixteenth-century child's leather shoe was found beneath the floorboards in a second room (Nicholl Reference Nicholl2017). Gilligan (Reference Gilligan2017) has recently brought attention to a Bronze Age socketed spearhead that was recovered from a house at Corglass, Co. Leitrim, in 1944. The artefact had been wrapped in sacking and placed within the fabric of the wall, and was interpreted by Gilligan (Reference Gilligan2017, 207) as a form of protection or counter-magic, or perhaps to balance ‘the disruption caused to the supernatural world’ by the construction of a new (human) house.

It is necessary to be cautious, however, about assuming that the presence of prehistoric artefacts in vernacular houses and outhouses necessarily meant that these always fulfilled an apotropaic or protective purpose. Many archaeological artefacts may have been retained simply as curios or to serve a mundane, practical function (see examples below). In the absence of written records or documented oral narratives, it is simply not possible to accurately interpret the role a specific archaeological artefact played within a particular building.

When the aforementioned prehistoric polished stone axes and Bronze Age weapons were discovered, they were not sold to antiquarian dealers or deposited in museums. Rather, these objects were carefully hidden in cavities in the walls of houses and farm outhouses, in thatch roofs and under rafters, or buried beneath floors and fireplaces—all liminal locations within vernacular houses and farmsteads. One folk tradition claimed that, to harness the counter-magic of a prehistoric arrowhead, it should not be allowed to touch the ground after it was found (Evans Reference Evans1957, 304). In Ireland it appears that it was more frequent to find prehistoric artefacts in outhouses and farm buildings, suggesting a fear or unease about keeping such items in the home. When a ‘queer looking thing’—a Late Bronze Age gold collar—was discovered in a limestone fissure at Gleninsheen, Co. Clare, in 1932, the finder's uncle believed it to be part of ‘an ancient coffin mounting’ and told him ‘not to keep it in the house’ (Gleeson Reference Gleeson1934, 138). It was hidden under a stone wall on the laneway to his house until the NMI was alerted to the find two years later. Feelings of apprehension and a belief that the collar related to the dead/supernatural influenced how it was treated and where it was kept. Similarly, many of those involved in the 1854 discovery of a Late Bronze Age gold hoard (Fig. 11) at Mooghaun, Co. Clare, during railway construction believed it to be ‘fairy gold’ and local people told that the finders did not ‘prosper’ afterwards (Westropp Reference Westropp2000 [1912], 76). This folk belief is likely tied in with wider traditions of buried treasure that was typically protected by the fairies, a leprechaun or a supernatural animal (O'Reilly Reference O'Reilly1994/5).

Figure 11. When discovered in 1854, many people believed that the Late Bronze Age gold hoard from Mooghaun, Co. Clare, was fairy gold. (Photograph: courtesy of the National Museum of Ireland).

Prehistoric artefacts were also more likely to have been kept in farm outbuildings simply because this was where the objects were actively used with animals, and the places where their protective powers were most needed. Polished stone axes were used in folk medicine, particularly for curing animals, and were used in a similar fashion to elf-stones and elf darts—by placing them in water which was then given to the animal to drink (Penney Reference Penney1976, 72). Perforated flint pebbles, known as witch-stones, were sometimes suspended from a string in a cattle byre to guard against ‘milk-stealers’ (Evans Reference Evans1957, 304; Penney Reference Penney1976, 71). Ettlinger (Reference Ettlinger1939, 152) recorded a stone spindle whorl of unknown date from Antrim that had been tied to a cow's horn to prevent the fairies from milking her. It is likely that the stone axes and Bronze Age metalwork described above related to folk medicine and farm outhouses allowed the folk healer privacy while conducting rituals. Possibly the best known Irish folk healer, Biddy Early (1798–1872), worked primarily with herbs; there are no records that she employed archaeological artefacts in her trade. Several accounts state that she worked in an outhouse for privacy: ‘out in the stable she used to go to meet her people’, that is, the fairies (Gregory Reference Gregory1992 [1920], 45).

Writing different biographies

The antiquarians—almost exclusively Anglo-Irish and English—who purchased and collected archaeological artefacts in nineteenth- and early twentieth-century Ireland saw these objects as relating to past human societies and cultures that were no longer in existence. In contrast, the predominately rural Irish population viewed archaeological artefacts as belonging to a supernatural society that co-existed in the present, parallel with their own world, and inhabited the same landscapes: archaeological artefacts represented the present, not the past. This is also mirrored in how archaeological monuments were perceived. To antiquarians, these were vestiges of past societies—redundant places frozen in time since their final abandonment in antiquity. By contrast, for the overwhelming majority of the Irish, archaeological monuments continued to be active places in the landscape, inhabited by supernatural beings and scenes of various paranormal events and misadventures. Megalithic tombs, prehistoric burial mounds and cairns, early medieval ringforts and medieval castles could provide a conduit to the supernatural world and were places that facilitated communication with the sí. Rural communities actively engaged with such sites.

Prehistoric artefacts were not rigidly considered supernatural and many did not enter the world of folk magic. To feed the burgeoning trade in antiquities, labourers and farmers supplied antiquarians with archaeological artefacts. These artefacts, whether found accidentally or deliberately sought out, provided economic opportunity and a means of income to impoverished farming families. This does not necessarily mean that the artefacts sold to dealers were perceived as mundane objects bereft of magical properties. Antiquarian William Knowles documented that people were frequently reluctant to sell prehistoric arrowheads and polished stone axes because they were believed to have curative properties, particularly for cattle. One large polished stone axe that he purchased towards the end of the nineteenth century from a man at Raloo, Co. Antrim, had been ‘treasured up in his house’ for 20 years before he reluctantly sold it (Knowles Reference Knowles1893, 161). The demands of poverty no doubt dictated or influenced whether artefacts were retained as special purpose items or were sold. It is plausible that some archaeological artefacts were in the possession of families for long periods of time, fulfilling a role in folk magic and medicine, but a period of crisis may have forced a sale. For instance, the aforementioned Neolithic hollow scraper from Coragh, Co. Cavan that was purchased by Knowles had been previously used for curing cattle (Knowles Reference Knowles1893, 100).

The nature of the person responsible for the find and his or her own belief system must have been a crucial factor in deciding the fate of an archaeological artefact. For some individuals, all artefacts may have possessed supernatural properties, while for others artefacts may have been viewed simply as saleable commodities. Some archaeological discoveries reveal how economic necessity negotiated with popular folk belief. In 1805 or 1806, men quarrying limestone at Knockane, Co. Cork, broke into a natural cave wherein they discovered a human skeleton covered with numerous gold plates and amber beads (Cahill Reference Cahill2006; Crofton Croker Reference Crofton Croker1824; Fitzgerald Reference Fitzgerald1858). This is arguably the richest Early Bronze Age burial yet discovered in Ireland. The ‘bones of the skeleton were eagerly sought after by the superstitious peasantry, as those of St. Colman, and carried away for charms’ (Crofton Croker Reference Crofton Croker1824, 253). The artefacts met a different fate. Only one piece of gold survives from the burial; the remainder, ‘rather more than the contents of half a coal box’, was sold and melted down by jewellers (Cahill Reference Cahill2006, 329–32; Crofton Croker Reference Crofton Croker1824, 253). The find at Knockane Cave came at a time of abject poverty for the vast majority of the Irish population and almost certainly for those who made the discovery. Selling the gold may have been a cause of unease, but popular belief was appeased by retaining and presumably venerating the bones that were deemed the remains of a saint. In this manner an element of dignity and reverence was maintained in a transaction that involved stripping and selling what was of monetary value from perceived Christian relics.

The changing belief system is evident in the recent life history of a perforated Neolithic stone macehead from Drumeague, Co. Cavan, that had been used in a stable as a weight on a horse's rein (Fig. 12). A letter to the NMI (11 November 1967) stated that in 1901 a boy had ‘heard his father and a neighbour discussing it, and the father said it had been in the stable as long as he could remember’. Almost certainly the artefact held magical properties potentially related to the health of horses and livestock kept in the building, or in the belief that ‘thunderstones’ could protect horses from having nightmares (Penney Reference Penney1976, 71). The boy, presumably unaware that this was a ‘special’ object, removed the macehead from its hole in the stable wall, fitted it with a wooden handle, and thereafter used it as a mason's hammer. Other examples are known of instances where prehistoric artefacts were deployed for practical purposes. Another Neolithic perforated stone macehead, from Drumkeelan, Co. Donegal, was used as a butter weight, though probably also served a role in protecting the butter from the fairies (Penney Reference Penney1976, 71). Polished stone axes were re-used as linen smoothers by linen weavers in Ulster during the nineteenth century (Sheridan et al. Reference Sheridan, Cooney and Grogan1992, 390). A polished stone adze was used as a whetstone at Carrownagarry, Co. Galway (Prendergast & Lucas Reference Prendergast and Lucas1962, 145). A Bronze Age sword from Scregg East, Co. Galway, was repaired in modern times (Prendergast & Lucas Reference Prendergast and Lucas1962, 149), while another Bronze Age sword from Aghadowry, Co. Longford, was mounted with a modern wooden handle (Lucas Reference Lucas1968, 111)—both cases presumably reflect modern reuse of these prehistoric weapons as everyday tools.

Figure 12. A perforated Neolithic stone macehead from Drumeague, Co. Cavan that was kept in the wall of a horse stable until c. 1901, when it was refitted with a modern wooden handle and used as a hammer. (Photograph: Marion Dowd.)

Folk magic in early medieval Ireland?

The practice of actively using prehistoric artefacts in folk magic and folk medicine in Ireland has been documented from at least the seventeenth century. In 1699, for instance, Edward Lhuyd recorded a prehistoric arrowhead that had been mounted in silver and worn around the neck as an amulet against the danger of being elf-shot. He added, ‘through-out Ireland and Scotland they are fully persuaded the elves shoot them at men and beasts’ (Ettlinger Reference Ettlinger1939, 154–5). That this folk tradition is at least three centuries old begs the question as to when such practices and beliefs originated. How did communities in late prehistoric or early medieval times make sense of the ancient objects they discovered? Penney (Reference Penney1976, 72) argues that stone axes may have been regarded as special items by the Middle Bronze Age in England, while Waddell (Reference Waddell2005, 7–8) similarly postulates that when Iron Age communities in Ireland discovered much older artefacts, these may have been perceived as magically charged. The recovery of prehistoric artefacts in later archaeological contexts in Ireland presents a compelling argument that a similar phenomenon existed at least from the early medieval period (ad 400–1169 in Ireland). An unusual case is an amber bead bearing an ogham inscription from Ennis, Co. Clare. In 1856 it was recorded that the bead had been in the same family for generations, who used it as a remedy for eye illnesses and to ensure safe childbirth (Ettlinger Reference Ettlinger1939, 155; O'Callaghan Reference O'Callaghan1856/7, 149–50). The date of the bead is not known. It may be contemporaneous with the ogham inscription (i.e. fourth or fifth century ad), or it may be a late prehistoric bead that was discovered and inscribed in the early medieval period. This is the only known occurrence of an ogham inscription on a bead indicating that it was of great significance in early medieval times. It is not inconceivable that the bead was used in folk magic from the beginning of the early medieval period through to the nineteenth century, over a period of approximately 1500 years. Similarly, the ogham stones discussed below potentially assumed magical status during the early medieval period some centuries after their original usage and from that point onwards may have been continually curated as special items. Perceptions of ‘magical objects’ probably varied enormously and would have been influenced by personal, local and regional attitudes to the supernatural realm and to folk magic.

The discovery of Neolithic and Bronze Age artefacts within domestic early medieval contexts is not uncommon. William Knowles considered that the occurrence of prehistoric polished stone axes in early medieval crannógs (settlements on lakes) reflected objects that were ‘treasured as amulets or champion hand-stones’ by the inhabitants (Knowles Reference Knowles1893, 161). Two polished stone axes and around 50 pieces of flint—including retouched and struck pieces, convex scrapers and an arrowhead of Neolithic or Early Bronze Age date—were recovered primarily from early medieval occupation levels in Lough Faughan crannóg, Co. Down (Collins et al. Reference Collins, Patterson, Proudfoot, Morrison and Jope1955, 61–2, 69–70). A flint convex scraper and a retouched piece of chert (possibly a second scraper, though interpreted by the excavator as an arrowhead) were found in the floor of an early medieval house, near the hearth, on a crannóg at Sroove, Co. Sligo (Fredengren Reference Fredengren2002, 230–31). Two polished stone axes were also recovered from a ringfort at Ballymulderg Beg, Co. Derry (Prendergast & Lucas Reference Prendergast and Lucas1962, 144). The discovery of four polished shale axes found scattered through early medieval domestic strata at Cahercommaun cashel, Co. Clare—a high-status settlement principally occupied during the ninth century—led the excavator to surmise that they may have been retained as charms (Hencken Reference Hencken1938, 55–7), though in a more recent assessment Cotter (Reference Cotter1999, 54) sees the axes as representing disturbed material from an earlier phase of activity. An incident that cannot be so easily explained away is the recovery of a Middle Bronze Age flanged axe from an early medieval souterrain at Carbery West, Co. Cork (Antiquities Register, NMI). Souterrains are artificial drystone or earth-cut underground tunnels used for storage or as hideaways, typically associated with ringfort settlements, and date primarily from the ninth–twelfth centuries (O'Sullivan et al. Reference O'Sullivan, McCormick, Kerr and Harney2014, 107). Was the axe placed in the souterrain when the latter was still in use? Or was the axe discovered in more recent centuries and placed in what was then an abandoned site possibly associated with the sí? Twenty stone axes and axe fragments were recovered from the early medieval settlement at Deerpark Farms, Co. Antrim. The axes were recovered primarily from occupation deposits: five came from identifiable structures, five came from possible structures, one came from a layer that sealed a hearth and one was retrieved from roofing material (O'Sullivan et al. Reference O'Sullivan, McCormick, Kerr and Harney2014, 100).

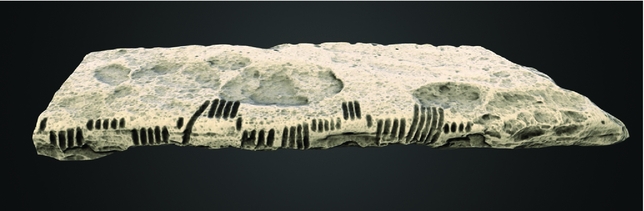

Yet another argument for continuity in folk magic practices between the early medieval period and recent centuries is the secondary use of ogham stones. Ogham represents the earliest form of writing in Ireland, comprising a series of lines and dots carved into large stones and boulders, usually referring to male personal names. They are generally dated from the late fourth–seventh centuries ad and are closely associated with ecclesiastical sites, concentrated principally in the extreme south and southwest of Ireland. Clinton (Reference Clinton2001, 68–76) noted that several centuries after their initial creation and use, many ogham stones were reused and incorporated into the fabric of domestic souterrains. Despite being separated in date by anything from 200 to 800 years, 130 of the 358 ogham stones (i.e. 36 per cent) recorded from Ireland derive from 45 souterrains; an almost equal number, 133 ogham stones, occur on ecclesiastical sites (Moore Reference Moore, Monk and Sheehan1998, 23).

Certainly ogham stones may have been considered attractive construction stones, particularly for use as lintels on the roof of a souterrain (Clinton Reference Clinton2001, 69; Moore Reference Moore, Monk and Sheehan1998, 27). However, even centuries after their initial carving, ogham stones must have been recognized as distinctive and/or ‘holy stones’ of ecclesiastical or funerary origin. Clinton (Reference Clinton2001, 73) suggests ogham stones may have been deliberately sought out and were incorporated into the domestic souterrain as a type of ‘charm’ for their ‘perceived quasi-talismanic properties’. Fast forward about one thousand years and several ogham stones are known to have been re-used as construction stones in farm outhouses. In Co. Kerry, ogham stones were discovered acting as lintels over the doors of outhouses or stables at Ballyandreen, Churchfield and Glanmore, while others acted as lintels in domestic dwellings at Martramane and Ballineanig (Cuppage Reference Cuppage1986, 252, 254–6). Two ogham stones from a ringfort in Rathmalode were re-used as door lintels—one in a domestic cottage and one in a cow dairy (Fig. 13)—at Lougher, Co. Kerry (Cuppage Reference Cuppage1986, 179). This latter case suggests that in early medieval times the ogham stones were removed from their original locations when already several centuries old and placed within the ringfort. Then, perhaps a millennium later again, the ogham stones were removed from the ringfort and placed at the entrance thresholds of a domestic dwelling and farm building. At this time ringforts would have been considered supernatural potent places in the landscape and there can be little doubt that the stones were incorporated into these vernacular buildings to harness some of these perceived powers (whether Christian or otherwise). Similarly, an early medieval cross inscribed stone that must have originated from a monastic site was found built into the wall of a vernacular house at Mullaghmore, Co. Sligo (Mc Gowan Reference Mc Gowan1993, 202).

Figure 13. Fifth-century ogham stone (Rathmalode II) that had been removed from an early medieval ringfort in 1853 and thereafter used as a lintel stone over the door of a dairy outhouse at Lougher, Co. Kerry. Length: 1.25 m. Transcription: ERCAVICCAS MAQI CỌ - a male personal name. (Discovery Programme for Ogham in 3D; https://ogham.celt.dias.ie.)

The recovery of an Early Bronze Age axe in the ruins of the medieval fifteenth-century Kilcrea castle, Co. Cork, and the discovery of a Bronze Age axe and spearhead at the sixteenth-century Aughnanure castle, Co. Galway, tantalisingly hint at the curation of found prehistoric artefacts in medieval times to fulfil apotropaic functions (Gilligan Reference Gilligan2017, 208–9). Significantly, both of these medieval towerhouses were constructed by Gaelic families.

Conclusion

The reinterpretation and reinvention of archaeological monuments in recent centuries has been well documented and there is an appreciation of their complex and changing biographies (e.g. Gosden & Marshall Reference Gosden and Marshall1999). The same level of interest and research has not been devoted to material culture, yet folk traditions reveal the rich and varied biographies that certain archaeological artefacts assumed in recent centuries. Far from being redundant objects, many were reinvented and came to fulfil important roles in the everyday lives of the largely rural agricultural population of eighteenth-, nineteenth- and early twentieth-century Ireland. In many instances prehistoric artefacts were stripped of their antiquity and original function and given new histories and meanings, but were seen as contemporary objects. In terms of distribution maps and recorded findspots, it is worth remembering that prehistoric artefacts may have travelled great distances in recent centuries. The eighteenth and nineteenth centuries witnessed large-scale movement of dispossessed people as a result of political upheaval, colonial plantations, famine and warfare. Some archaeological artefacts were likely taken to new locations and new homes by those who considered them special objects.

One might ask why this aspect of the later life-histories of many prehistoric artefacts has been so neglected in Irish archaeological studies (though this has also been the case in Britain until recently: see Gilchrist Reference Gilchrist2008, 119; Merrifield Reference Merrifield1987, chapter 1). Similarly, archaeologists have rarely engaged with the folkloric significance of specific archaeological monuments (as opposed to references to monuments in early literary texts). For instance, the Archaeological Survey of Ireland, which has completed detailed archaeological field surveys and historical research of all the archaeological sites and monuments in the 26 counties of the Republic of Ireland, rarely if ever document folk traditions pertaining to monuments. Thus, increasingly, it is not possible to connect a particular sí story with a particular monument (e.g. the fairies kidnapping a child and taking her to a ringfort), yet when such folktales were actively in circulation in oral tradition, they typically related to a specific identifiable site. During the 1930s the Irish Folklore Commission (IFC) collected folklore from across Ireland. The School's Folklore Collection can now be searched online (http://www.duchas.ie/en) and includes many stories pertaining to the fairies, fairy forts and elf darts. More significantly, the National Folklore Collection (NFC) at University College Dublin—which was inscribed to the UNESCO Memory of the World Register in 2017—contains much relevant material on the interplay between the fairies and archaeological monuments and artefacts. Unfortunately, as material in the NFC is not yet published and not available online, it was not consulted for this paper, but promises to return rich dividends for future researchers of the topic. Tellingly, the IFC helped in the acquisition of archaeological artefacts, presumably objects encountered in the course of folklore collection (Lucas et al. Reference Lucas, Prendergast, Ó Ríordáin and Rynne1958, 116, 120). Now, however, such folktales are floating in space, divorced from their physical reality and on-the-ground ‘evidence’ of the fairies. In popular literature there can be a tendency to consider the sí as a survival from pre-Christian Irish spirituality. However, in the case of fairy forts, the incredibly strong association between the fairies and the early medieval ringfort is a historic product and can be no more than at most 800 years old, as these settlements were largely (though not entirely) abandoned by the late twelfth century. Thus in some cases we can roughly ‘date’ folk beliefs linked to archaeological sites.

Unconsciously, the discipline of archaeology—concerned as it has been with scientific approaches—may have shied away from folk magic and folk medicine, topics that eighteenth- and nineteenth-century (Anglo-Irish and English) antiquarians and writers regarded as illustrating at best the ‘unusual customs’, and at worst the ‘primitive superstitions’ and ignorance, of the ‘vulgar’ (Gaelic) Irish population (Thompson Reference Thompson2004, 341–3). This divide is, of course, firmly rooted in Ireland's difficult and painful colonial history. Perhaps, in being influenced by the nature of archaeological research and its development in Britain, we have silently overlooked an incredibly rich resource of ethno-historical information on how the distant past was perceived in the recent past. It is still possible to find people throughout Ireland who remember such folk beliefs and folk medicine practices and can explain why, for instance, a horse leg should be found in the roof of a house, or why a Neolithic arrowhead would be known as an elf dart. This surviving knowledge is something that has disappeared from much of Britain (excepting Scotland) and northwest Europe where folk magic has been documented, but the reasoning behind certain practices is long forgotten. Ireland, therefore, has much to offer in terms of exploring the relationship between folk belief, folk magic and archaeology.

Acknowledgements

This paper has had a long gestation and I am grateful to the many individuals who have generously shared information, discussed the topic, and provided suggestions or reading material along the way: James Bonsall, Seamus Caulfield, Owen Davies, Ian Evans, Donna Gilligan, Robert Hensey, Joe Mc Gowan, Pádraig Meehan, Sam Moore, Margaret Savage, Martin Savage and Damian Shiels. My thanks to the two anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments, and to the CAJ editor, John Robb. I owe a particular debt of gratitude to Bairbre Ní Fhloinn for valuable feedback on several aspects of Irish folklore, and for directing me towards relevant sources. Any remaining errors or shortcomings are mine alone. The staff of the National Museum of Ireland, particularly Mary Cahill, Andy Halpin and Ned Kelly, were very helpful during my time spent examining artefacts and paper records at that institution. My thanks to James Bonsall for Figures 1 and 2; Mary Cahill and the National Museum of Ireland for Figure 11; and Nora White and Ogham in 3D for Figure 13.

I dedicate this paper to Prof. Gearóid Ó Crualaoich of the Department of Béaloideas/Folklore and Ethnology at University College Cork. As an undergraduate student of Léann Dúchais from 1992–1995, Gearóid gently encouraged and supported my curiosity and interest in the relationship between archaeology and folklore. This paper is the eventual consequence of that period of study, and I thank Gearóid for seeing the value in a cross-disciplinary approach at a time when such was relatively unheard of in Ireland.