Book contents

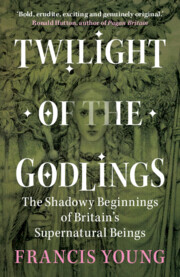

- Twilight of the Godlings

- Reviews

- Frontispiece

- Twilight of the Godlings

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Plates

- Preface

- Abbreviations

- Introduction

- 1 A World Full of Small Gods

- 2 Menagerie of the Divine

- 3 The Nymph and the Cross

- 4 Furies, Elves and Giants

- 5 The Fairy Synthesis

- Epilogue

- Bibliography

- Index

Introduction

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 09 March 2023

- Twilight of the Godlings

- Reviews

- Frontispiece

- Twilight of the Godlings

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Plates

- Preface

- Abbreviations

- Introduction

- 1 A World Full of Small Gods

- 2 Menagerie of the Divine

- 3 The Nymph and the Cross

- 4 Furies, Elves and Giants

- 5 The Fairy Synthesis

- Epilogue

- Bibliography

- Index

Summary

The introduction articulates the problem of the origins of Britain’s folkloric beings and traces the various ways in which scholars have tackled (or sidestepped) the problem, from John Aubrey to the present day. The introduction seeks to explain why scholars became wary of engaging with folkloric origins as a historical question, critiques previous approaches to the history of folkloric beings, and presents the book’s new approach in the context of current methodologies in the study of the history of popular religion. The introduction then outlines the structure of the book

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Twilight of the GodlingsThe Shadowy Beginnings of Britain's Supernatural Beings, pp. 1 - 36Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2023