On the late autumn day of 2 November 1956, Russian commander-in-chief Marshal Ivan Konev established the Hungarian headquarters of the Soviet army in Szolnok. Two days later he would give orders to attack and put an end to the Hungarian uprising against the communist regime. Ten days had passed since the mass demonstration initiated by university students took a revolutionary turn on 23 October. The Hungarian revolution, this key moment of the Cold War, would be crushed in little over a week.

On the same day, Imre Nagy, the revolutionary prime minister, also gave orders in Budapest. However, the nature of the Hungarian leader’s orders could hardly have been more different from that of his Soviet counterpart: amidst the turbulent events of the revolution, he took the time to establish a polio hospital.Footnote 1 Even though the revolution would come to an end in a matter of weeks, the Heine-Medin Post Treatment Hospital would survive and continue to operate for seven more years treating children with polio, a cause that seemed to override political ideologies and regimes.

The revolution of 1956 was a key event in the history of the Cold War. Millions of people worldwide followed the unfolding of the October events. International efforts were aimed at accommodating – and protecting – hundreds of thousands of refugees who left the conflict-torn country. The Hungarian Revolutionary became man of the year on the cover of TIME magazine. The events of the revolution have been widely discussed in Cold War historiography,Footnote 2 and the uprising overshadows the Hungarian historical narrative of the era.

It is less well known that there was a polio outbreak during the revolution in the eastern part of the country. It was an unexpected, autumn epidemic that could not have come at a worse time. As infrastructure and state services collapsed with the turmoil of the revolution, those affected by the disease had difficulties in getting help. The country was already in a dire situation in terms of basic medical services, especially in the conflict-stricken areas, and was badly in need of aid; an epidemic on top of the battles only exacerbated the public health emergency. Yet the breakdown of transportation systems and the lack of safety on the roads might have contributed to the relatively contained nature of the outbreak: other than fleeing to the West, not many travelled in late October that year.

Cold War relations, with their thaws and frosts, affected polio in Hungary in various ways. Some watershed events of the Cold War, like the 1956 revolution in Hungary, had unexpected effects on the epidemic management of polio. The political and social upheaval of revolution propelled Hungarian polio treatment forward with the establishment of a specialised hospital, plans for which had already started in the early 1950s. Access to technologies and knowledge ebbed and flowed in ways that did not necessarily map onto the usual Cold War narratives. In this sense, the preoccupation with polio presents us with more continuity than is allowed for by Cold War history.

The politics of polio in the 1956 revolution also point to the importance of considering individual actors on the ground when examining international humanitarian and medical interventions. Putting polio at the centre of this well-known event in the history of the Cold War sheds light on the important and life-saving role that international organisations such as the Red Cross played at a time of political and epidemic crisis. However, the actions of these organisations were put into motion and often executed by individuals who had no official connection to international organisations. They were physicians, amateur radio users, virologists, nurses and religious scholars, who utilised their professional and political connections and resources to tackle the tasks of preventing and treating polio in a time of turmoil.

The humanitarian crisis in the wake of the uprising not only facilitated the influx of hospital equipment, but also highlighted international and local responses to scarcity through an emerging network of iron lungs that criss-crossed the Iron Curtain. This scarcity was partly due to the destruction caused by past and current armed conflict in Hungary and the result of national and global Cold War politics. At the same time it was also a universal problem, caused by the insufficient supply of a costly technology that had trouble meeting the huge demand of severe outbreaks not just in Eastern Europe but all over the world.

The 1956 Revolution and International Aid

On 23 October 1956, university students, joined by workers, intellectuals and even the communist youth organisation Union of Worker Youth, flooded the streets of Budapest demanding reforms. Crowds assembled at the Radio and tried to have their demands broadcast, while some assembled in front of the parliament and others joined forces to knock down a great statue of Stalin. By the late evening, shooting had started at the Radio, where the demonstrators, armed with the help of workers from ammunition warehouses and factories, besieged the studios and took over the building by dawn.

The roots of the revolution lay in the changes in Soviet policy towards the Eastern Bloc triggered by Stalin’s death in 1953. This did not necessarily mean that the status of satellite states was up for negotiation: in the same year, the states of the Eastern Bloc and the Soviet Union signed the military alliance Warsaw Treaty Organisation, signalling a tightening of Soviet control over Eastern Europe.Footnote 3 However, after Nikita Khrushchev announced ‘peaceful coexistence’ with Western nations and condemned Stalinism in 1955, debates cropped up across the region on fundamental political issues, most of all in Poland and in Hungary.

By 1953, the Hungarian economy was on the brink of collapse, and the Soviet leadership initiated changes in policy and personnel. Imre Nagy became prime minister and initiated several reforms, but he and his reforms soon became caught up in power struggles and Moscow became increasingly dissatisfied. The Hungarian economy had not improved as they had hoped, and Nagy’s effort to democratise the party resulted in Mátyás Rákosi, a devout Stalinist, making a comeback in 1955 and having Nagy removed from his seat. By the end of the year, Rákosi had expelled him from the party. There was no going back to the pre-1953 era, however. Nagy’s reforms opened a Pandora’s box of dissatisfaction and opposition within Hungarian society, which was experiencing new economic and political pressure; the masses lived in extreme poverty, but now had a sense of an alternative. Through Soviet intervention, Rákosi was removed, but it was too little too late.Footnote 4

In October 1956 it all came to a head. In Poland, Wladyslaw Gomulka’s reformist faction rose to power, prompting university students in Hungary to formulate their own demands for reforms and organise a march of sympathy with Poland for 23 October 1956. It was from this demonstration that the revolution erupted. The next few days saw fierce street battles among protesters, the Soviet army, the Hungarian secret police and occasionally the Hungarian army, which was joining the ranks of the rebels in increasing numbers. The revolutionaries erected street barricades, tore down Stalinist statues, occupied public buildings and even captured tanks. The revolution was occasionally peaceful, and sometimes extremely violent on both sides. A massacre in front of the Parliament took the lives of over 300 civilians, and in the turmoil of the revolution demonstrators lynched several members of the secret police and strung them up on lampposts as gruesome reminders. The country, Budapest first and foremost, suffered great damage as fighting between armed rebels and the military took place on crooked streets, in squares and on bridges.

Imre Nagy took the seat of prime minister once more and in an effort towards consolidation promised significant reforms. On 30 October he announced the end of the one-party system and the formation of a coalition government. A few days later Hungary declared itself neutral and withdrew from the Warsaw Pact. Ultimately, however, Soviet tanks rolled into Hungary and Budapest came under artillery fire on 4 November 1956.Footnote 5 By 11 November, the Soviet military had broken armed resistance, Nagy had sought refuge at the Yugoslavian embassy and János Kádár had taken the oath of office; meanwhile, sporadic demonstrations continued well into mid-December.

The crisis and revolution of 1956 opened up discussions about the failings of the communist healthcare system. It was a rare instance when fundamental critiques and the admission of failure on several fronts were openly verbalised and gained publicity. The double-speak that permeates the archival materials of the time lifts for a brief moment in the professional meetings and newspaper reports of the days preceding the revolution.Footnote 6 In a meeting with leaders of health institutes on 19 October 1956, Health Minister József Román admitted that contrary to the goals of the first five-year plan, no new hospitals had been built. He pointed out that the growing demand for health services had been met by the further overcrowding of extant facilities or the appropriation of buildings that were not originally intended for healthcare use.Footnote 7 The minister also conceded that the areas of public health and epidemiology had been particularly neglected in recent years.Footnote 8 The simultaneous outbreak of a revolution and a polio epidemic further exacerbated these conditions. Some hospitals and clinics were badly damaged during street battles, especially in Budapest.Footnote 9 By December, even basic hygiene supplies such as soap were hard to find.Footnote 10 During and after the revolution, Hungary was decidedly in need of foreign aid.

Humanitarian aid and the intervention of the Red Cross in the Hungarian Revolution became symbolic acts in the Cold War, albeit ones with very important consequences on the ground. Donations of food, clothes and medicine from Western countries became powerful expressions of support for the cause of the revolution,Footnote 11 while the Soviet army and the post-revolutionary Hungarian regime saw the humanitarian intervention as a political and military scheme.Footnote 12

In fact, the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) was the only international organisation that was granted access to Hungary during and immediately after the revolution. The Hungarian Red Cross contacted the ICRC on 27 October to request aid and the first shipment arrived two days later. In the meantime, the ICRC requested that twenty-six national Red Cross societies send blood, medical equipment and medicine to Vienna, where the shipments were assembled. The humanitarian intervention was not uncontested by the Soviet army. In one case, the aircraft carrying medical supplies and food had to turn back due to Russian tanks having blockaded the airport, and convoys were suspended between 4 and 11 November because the border between Hungary and Austria was closed off.Footnote 13 The Soviet occupying forces were very suspicious of the aid workers during and after the revolution. Evidence suggests that several ICRC workers were arrested and held by the KGB for ten days, during which they were questioned about their actions and movements.Footnote 14

Despite these difficulties, the ICRC continued to send convoys and aeroplanes to provide aid throughout the revolution.Footnote 15 Clothing, infant milk, food and medical supplies were in great need, especially in Budapest, a city that had barely had time to recover from the destruction of the Second World War, only to be torn apart by tanks, machine guns and Molotov cocktails once again. Aid continued to flow into the country – with the subsequent approval of the new Hungarian government backed by the Soviet Union – until the summer of 1957.Footnote 16 Industrial production stopped as strikes continued well into the winter, and infrastructure was badly damaged.

Red Cross aid was tolerated and even welcomed by the post-revolutionary government. Moreover, the need for food, clothes and medical supplies created a space for cooperation with the Hungarian branch of Actio Catholica, the Catholic international movement, which had been established in 1932.Footnote 17 On 11 December 1956 the ICRC, the Hungarian Red Cross society and Actio Catholica signed a trilateral agreement stating that all aid received should be distributed by the Hungarian Red Cross. However, the Catholic group did distribute 150 train wagons of aid, for which it was heavily criticised in 1957; it was accused of using resources unfairly, for instance giving out tinned whale to rich Catholics.Footnote 18 Shortly after, the religious organisation was co-opted by the Hungarian post-revolutionary government. The Hungarian Red Cross faced a similar fate.Footnote 19

In the early days of the 1956 revolution, Imre Nagy appointed a commissioner to head the Red Cross, along with a committee of university professors to take over the leadership of the organisation. In the months following the failure of the uprising, the new government had no time or energy to deal with the internal structure of the Red Cross, whose services were needed to distribute the still incoming shipments of aid. In June 1957, the new government commissioner and committee were dismissed and a new leadership appointed: the rector of the Budapest Medical University and Academy member, Dr Pál Gegesi Kiss, became president, while József Kárpáti, a former ambassador, became secretary. The takeover involved an inspection of the organisation’s actions in 1956–57, its stocks and membership. All activists who had been involved in providing aid to revolutionaries were expelled from the society. In 1959 the Hungarian Red Cross was still struggling with its heritage, as the presidential committee strove to communicate a marked difference between ‘pseudo-civil humanism and the current, socialist Red Cross’.Footnote 20

As the Hungarian Red Cross society saw a complete changing of the guard, the relationship with the ICRC slowly began to deteriorate. A report on the takeover of the Hungarian Red Cross and its status in 1957 lambasted the ICRC for ‘not keeping control over the distribution of aid during and following the revolution. Instead, they were caught up in their own and their supporters’ propaganda and took great care not to be inspected by Hungarian governmental authorities, saying it would be political intrusion.’Footnote 21 In his inauguration speech, Győző Kárász, the new vice-secretary of the Hungarian Red Cross, went as far as to accuse the ICRC of abusing the Red Cross emblem and smuggling guns and ammunition into the country during the revolution.Footnote 22 The ties between the international and national organisation were further strained by a struggle over the attempts at the ‘repatriation’ of youths and children after the revolution. The ICRC blocked any attempts by the Hungarian Red Cross and the government to send out the names of underage refugees in order to bring them back to Hungary.

The impact of Red Cross activities in Hungary during and after the revolution had global significance. The actions of the ICRC during and immediately after the revolution became one of the major success stories that served to re-establish the organisation’s battered reputation after 1945. In the 1950s, the ICRC was battling against a damaged reputation from its controversial role in the Second World War, especially with regard to the Holocaust. The ICRC had not acted when the German Red Cross went against the fundamental ideas of the movement, such as the universality of the Red Cross, as Jews were forced out of the society.Footnote 23 Despite their knowledge of the genocide in Nazi Germany from 1942 onwards, the ICRC had decided to remain silent on the issue, and had shied away from issuing even a mild and vague public statement reminding belligerent states of humanitarian principles.Footnote 24 Following the war, the ICRC needed to prove that it was a viable organisation.

Moreover, the humanitarian intervention in the Hungarian revolution became a reference point for the armed conflicts that followed, among them the Algerian liberation movement in 1956. The National Liberation Front (FNL) and the newly established Algerian Red Crescent (not acknowledged by the League of Red Cross societies) both contrasted the indifference of Western powers to the Algerian struggle and the accompanying lack of humanitarian assistance with the aid provided to Hungarian freedom fighters and refugees, in order to highlight the difference in standards applied to European and Third World countries.Footnote 25

Revolutionary Skies: Iron Lungs on and in the Air

Strikingly left out of the story of Red Cross intervention in the Hungarian revolution was the organisation’s role in supporting polio treatment during and immediately after the uprising. While supplying aid for long-term treatment was not among the declared priorities in providing assistance to conflict-torn countries, the geopolitical significance of this particular conflict made possible the inclusion of diverse needs. The revolution thus provided windows of opportunity for physicians invested in polio treatment to obtain medical technology and hospital equipment from abroad to which they otherwise would not have had access. This aspect of humanitarian intervention in the 1956 revolution is entirely missing from the historical narratives of the uprising itself or of the Red Cross. The reason might be that, as we will see, these transactions did not involve governments; in some cases, they hardly involved international organisations at all. As such, most of the international aid and collaboration in preventing and treating polio was initiated – and carried out – on the ground, and its history remains invisible when studied from above.

As the revolution was unfolding in Hungary, a polio epidemic erupted in the north-eastern part of the country, leaving parents and doctors in a desperate situation. The country’s infrastructure came to a full stop, and administrative services and communication ran into severe problems. For many cities, the only means of establishing contact with the outside world was radio. Broadcasts were used not only to inform people of the events and goals of the revolution, but also as channels for family members to look for each other or notify each other of their safety, to reach over borders for aid and to coordinate processes that would have otherwise fallen under the tasks of the state. Occasionally, doctors would send each other messages about incoming aid or transporting blood to the wounded.Footnote 26

On 29 October the radio stations of Miskolc and Nyíregyháza broadcast an appeal for an iron lung for the hospital of Debrecen, since its only iron lung was broken.Footnote 27 Iron lungs were life-saving devices that essentially breathed for polio patients suffering from respiratory paralysis. By the 1950s the machines came to symbolise the horrors of polio epidemics in the imaginations of parents all over the world. Iron lungs and other respiratory machines, such as swing beds (rocking beds), were crucial in the treatment of the acute phase of the disease.

Iron lungs, no longer in use today, were large, tubular metal machines that operated with negative pressure. The patient lay on her back, her whole body inside the machine, with only her head on the outside. The machine created a vacuum inside the tank, which made the patient’s chest rise, resulting in inhalation. The pressure then changed in the tank, letting the chest fall and creating exhalation.Footnote 28 This device could only work for patients without complications, since any infection or mucus would cause significant problems – patients with respiratory paralysis cannot cough. Another important respiratory method, developed in Denmark in the early 1950s, was called intratracheal positive-pressure respiration. A portable machine applied positive pressure into the lung of the patient directly through the trachea. This meant that a tracheotomy was necessary; however, getting rid of mucus also became easier, and the less mucus, the lower the risk of infection. The least invasive respiratory device was the rocking bed. This bed, swinging back and forth like a seesaw, used gravity to help breathing. Internal organs pushed and pulled the diaphragm as the body swayed up and down in a lying position.

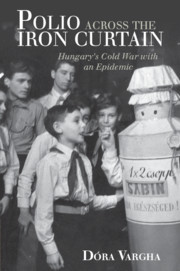

Figure 2.1 Both-type iron lung, London, England, 1950–55. By Science Museum, London. Credit: Science Museum, London. CC BY.

The first iron lung arrived in Hungary in 1948, with the cooperation of the American embassy and Andor Bossányi, director of the László Hospital of Infectious Diseases.Footnote 29 This machine became the basis of the respiratory ward of the infectious disease hospital organised by Dr Domokos Boda under the direction of Pál Ferenc.Footnote 30 Nevertheless, for a long time, access to the treasured respiratory device was difficult.

In the first half of the 1950s, iron lungs began to be produced in Czechoslovakia and the GDR.Footnote 31 By 1959, over 100 Hungarian iron lungs were in use in the country.Footnote 32 Most of the iron lungs arrived in Hungary during the 1957 epidemic, the worst year for polio in the country’s history. However, the arrival of a much-needed iron lung during the 1956 revolution tells perhaps one of the most dramatic stories of international cooperation during the Cold War.

The hospital’s request for help found its way to Munich through Radio Free Europe (RFE), which was monitoring and documenting radio transmissions in Hungary and had its headquarters in the German city.Footnote 33 Requests for help through radio waves were not uncommon during the revolution, especially requests for medical aid. In contrast to requests for political and military intervention, guns and ammunition from the West, which mostly went unanswered,Footnote 34 appeals for public health intervention made through domestic radio broadcasts travelled a long way with the help of RFE. In a telegraph to Geneva, RFE notified the Red Cross about a call ‘to all international helping organisations’ about the polio epidemic in the North-Eastern region, stating that thirty people had already died and asking for ‘a serum against this malady’.Footnote 35

In reply to the appeal for an iron lung, the RFE station sent back a message through its broadcast that same afternoon:

We have important news for the hospital of Debrecen. We have heard your urgent appeal regarding the iron lung. We will immediately help and we have done everything for the desired iron lung to leave today for Debrecen. The only reason for delay is that there is no iron lung for sale in Munich at the moment. Keep listening to our broadcast; we will let you know immediately when the iron lung begins its journey.Footnote 36

Apparently, the shortage of respiratory devices was not unique to Hungary. In their next message, RFE let the Hungarian hospital know that there were no available iron lungs for sale on the whole continent, due to the epidemic outbreak in the Netherlands.Footnote 37

It is uncertain how the RFE managed to secure a device in the end. Only 20 minutes after stating that they were not able to obtain an iron lung, the presenter suddenly interrupted his account of the events in Hungary to announce once again that they would do everything in their power to send the life-saving machine that day. A few hours later, on the evening of 29 October 1956, an iron lung onboard a German aeroplane arrived in the skies above Hungary. The was almost certainly organised by the West German Red Cross, but the origin of the device at this point remains a mystery. What we do know, however, is that landing the aircraft was more than challenging: in the midst of the revolution, airports were not functioning and there was no one to control the aeroplane from the ground.

At 10:10 p.m., the radio station of Miskolc broadcast an urgent message for Hajdúszoboszló, the town neighbouring Debrecen, to illuminate their airport for the arrival of the iron lung. All they needed to do then was to direct the aeroplane there. Four minutes later, the radio broadcast the following message: ‘Attention, attention! We ask all amateur [radio transmitters] to help with landing the plane! Seek connection with [the aeroplane] and direct it to Hajdúszoboszló, where a lit-up airport will receive it.’Footnote 38 A few minutes later, the radio revealed that the plane was flying above Debrecen, close to the target airport. However, something must have gone wrong; the plane had to be redirected to yet another city through public radio: ‘Attention, attention, radio stations of [Budapest], Debrecen and all Hungarian airports, and radio control of the German aircraft! Direct the aeroplane to Miskolc! We are waiting for it. It will be able to land at the airport there. We will transport the iron lung to its destination!’Footnote 39 There is no way of knowing how many amateurs took part in this community effort, using low-tech, amateur devices and knowledge to navigate the plane and ensure the safe arrival of the iron lung. From the initial appeal for help through radio, in a time of upheaval and during the breakdown of infrastructure and services, the life-saving equipment reached its destination with efficiency that would put a communist dictatorship to shame.

This iron lung did not follow the usual route of aid flowing into the country at the time. Other donations from various locations were mostly collected in Vienna and transported from there via aeroplane or convoy to Budapest, where the resources were distributed,Footnote 40 and were not flown individually to specific locations. The arrival of the iron lung in the autumn of 1956 was, it seems, an exceptional event under the exceptional circumstances of the revolution.

What makes this feat particularly interesting is that it was accomplished with the help of a technology that was right in the centre of ideological and political contestation: radio. Since radio waves crossed borders with ease and were a relatively simple and cheap way of reaching a theoretically unlimited number of people on the other side, radios were considered to be crucial weapons in waging the media war of the 1950s.Footnote 41 Hungary was also an active participant on this front: the state vigorously communicated the achievements of peoples’ republics to a potential audience ranging from East Asia to Latin America, while Hungarian language programmes from the West attempted to reach behind the Iron Curtain. ‘The enemy works against us on 110–120 different frequencies, in an accumulated 210–220 hours per day’, stated a report prepared for the Hungarian Workers’ Party’s Political Committee in 1954.Footnote 42 The Hungarian government attempted to curb access to these transmissions by issuing radios that were technically unable to receive anything except the two official stations. Later, in an international project with neighbouring countries, they built transmitters designed to jam the radio signals of Radio Free Europe and Voice of America.Footnote 43 Radio Free Europe was naturally very much under the watch of the Hungarian secret police (ÁVH), who had installed regularly reporting agents in the Munich headquarters from at least 1955 onwards.Footnote 44 Even listening to the programme was punishable by law.

There is little information about radio amateurs of this era. Amateur radio clubs were permitted in limited numbers and the Association of Hungarian Shortwave Radio Amateurs was re-established in 1948 after having been banned in 1944. By 1954 there were fifteen clubs active in the country, three of which were in Budapest, and by December 1955, 101 amateur radio users were registered nationwide.Footnote 45 While we do not know their exact relationship with the communist regime, at least some of them were clearly critical and took part in the 1956 uprising in their own way. One amateur radio user recounts having ‘fixed’ a high number of radio receivers in 1956, enabling them to receive all frequencies instead of only the state-sanctioned ones.Footnote 46

While the dramatic story of the iron lung flying over the country in revolution is an exceptional one, the speedy transport of a respiratory device over political borders during an epidemic crisis was not entirely unusual at the time. In a country strained by the effects of the Second World War, forced industrialisation and collectivisation and a bloody revolution, medical supplies were often scarce and facilities were not readily available to accommodate the long-term care of polio patients. Moreover, polio was a disease that required highly specialised equipment – most importantly life-saving respiratory machines such as iron lungs.

The devices were expensive and hard to come by, especially on the eastern side of the Iron Curtain. This lack of resources triggered innovation, with new ways of using existing devices or developing new machines. However, Hungary was not alone in its difficulties in accessing high-tech machinery. In the midst of the Cold War, in a network spearheaded by the International Committee of the Red Cross, iron lungs criss-crossed Europe (and, in fact, the globe) to assist polio patients wherever an epidemic crisis was unfolding.

The idea of mutual assistance in polio epidemics and the establishment of a global network of respiratory devices first came up in May 1948 at the European Regional Conference on Poliomyelitis in Brussels. Among other recommendations for procedures during epidemics and questions of recuperation and treatment centres, the conference identified access to respiratory devices as a crucial problem in tackling polio. The attendees expressed the wish that various countries undertake the mass production of respiratory devices with the aim of reducing the cost of the expensive machines. Secondly, each country should keep a stock of iron lungs in proportion to its population, and, in case of an epidemic emergency,

if local resources are insufficient, to provide for, to study and to determine the ways and means for a rapid mobilisation of means of assistance. Such mobilisation should include not only iron lungs and necessary equipment, but expert medical advisors and trained helpers belonging to the regional areas or to neighbouring countries.

The Belgian delegation then put forward the conclusions of the conference at the First World Health Assembly of the newly formed World Health Organisation.Footnote 47

The WHO sent out a circular letter to all European countries the following year, to which fifteen countries had replied by 1950. Based on the replies, the WHO took stock of the available respiratory devices across the continent; the advantages and disadvantages of the various models; the way in which access to respiratory devices was organised (i.e. national or regional level, whether there was a central stock etc.); and the availability of specialised staff. The questionnaire also gauged interest in the establishment of an international iron lung loan system. The options on the table were an international loan network, loans based on bilateral agreements or, alternatively, the establishment of a European, central stock of respirators to be utilised in the case of epidemic emergency.Footnote 48

Not all countries were enthusiastic about the proposal. Opinions were divided over whether a network or a centralised stock would be the best solution, and a significant number of countries decided against the whole scheme. Among them was Hungary.Footnote 49 It is important to note here that in 1950 countries like Hungary had yet to experience severe epidemic waves of polio. The acute problem of respiratory paralysis on a mass scale had not been a reality at that time and it is doubtful that anyone would have anticipated the escalation of epidemics in the 1950s across the globe. Finally, due to the varied responses as to how the international loan of respiratory devices should be organised, if indeed they should be organised at all, the Executive Board of the WHO decided to hold off on taking any steps unless the initiative garnered wider support.Footnote 50

However, the lack of available respiratory devices remained a problem for most of the decade. In 1954, Austria identified the insufficient number of iron lungs available as one of its main challenges,Footnote 51 while polio experts from the Netherlands considered the issue of respiratory paralysis to be ‘of extreme importance’ and planned to organise training courses for specialised physicians and nurses.Footnote 52 Scandinavian polio experts formed a special respiratory committee to advise the North European states and give ‘suggestions for acquiring a respirator emergency stock’.Footnote 53 The Scandinavian scheme for cooperation was soon put to the test when the Nordic countries were required to provide aid to Iceland during an epidemic in 1955.Footnote 54

In the end, it was the Red Cross – not the WHO – that became the organising force behind the international network of iron lung loans. With polio epidemic outbreaks on the rise worldwide, the network of loaning respiratory devices reached far beyond the original European area. The League of Red Cross Societies became increasingly invested in providing aid during polio epidemics. In a report from 1957, the Red Cross considered polio epidemics to fit perfectly with their main goals of ‘diffusion among the population of humanitarian principles and, respectively, the application of these principles in the prevention and relief of human suffering’. Accordingly, the League advised all national societies to ‘participate as actively as possible’ in combating the disease.Footnote 55 The national societies took on the new challenge and carried out various tasks, from the sterilisation of syringes and needles for mass vaccination campaigns (in the United States) to supplying orthopaedic appliances (Ecuador) and increasing stocks in medical loan depots (Sweden).Footnote 56

National Red Cross societies were not only involved in epidemic management in their own countries, but were active in transnational interventions as well. In 1957, a severe epidemic in Argentina prompted the West German, Italian and American Red Cross to send iron lungs and respiratory devices, while other countries, such as India and Czechoslovakia, contributed with specialists, hospital linen and vehicles to facilitate care for polio patients. In the same year, about seven months after the revolution was suppressed, Hungary became once again the focus of international aid when the Hungarian Red Cross asked the League to supply twenty respiratory devices as quickly as possible. Now there was peace, there was no need for radio.

The Hungarian case gives us an idea of what the use of the loaning network looked like in practice. In 1957 the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) and the League of the Red Cross Societies coordinated an international effort to identify heavy-respiratory machinery all across Europe and send it to Hungary. The Hungarian delegate of the ICRC, who in early July found the epidemic severe but not catastrophic, deemed the insufficient number of respiratory devices as the most pressing problem.Footnote 57 Meanwhile, the ICRC headquarters was waiting for the reports of two Swedish polio specialists, Dr Lindhal and Dr Werneman, who were sent by the Swiss Red Cross to Hungary to determine the country’s needs.Footnote 58 The international experts were seen by the Health Ministry as ‘being able to provide significant assistance in getting aid from foreign organisations as soon as possible’Footnote 59 and thus were supported by the Hungarian government in their mission.

In the opinion of the Swedish doctors, the Hungarian hospital staff, including physicians, nurses and technicians, were sufficient in number and their treatment methods and expertise were ‘modern’. The most urgent issue was, they concluded in accordance with the ICRC delegate, the lack of respiratory equipment. According to their findings, about 15–20 per cent of paralytic polio cases involved respiratory paralysis. Before the peak of the epidemic wave at the end of July, thirty-five patients needed artificial respiration. However, there were only twenty-four iron lungs in the country. The experts who visited treatment sites were apparently impressed by the innovation of Hungarian physicians and technicians born out of necessity and meagre resources. The report describes iron lungs transformed into devices that could serve three infants at a time instead of one and rocking beds accommodating up to six children.Footnote 60

A detailed description of this latter technology in the Hungarian medical journal Orvosi Hetilap [trans. Medical Weekly] reveals that, in fact, even more children could be treated with a single respirator than in the cases encountered by the Swedish experts. Patients were connected to the tank of the iron lung through the side openings with rubber tubes and breathed through a humidifier receptacle.Footnote 61 This addition was important, keeping the patients’ mucous membrane humid and thereby preventing infection.Footnote 62 With this technology, in an extreme situation in December 1956, Hungarian physicians were able to connect ten infants to one iron lung. Between June 1956 and July 1957, more than 100 patients were treated by the common use of a single iron lung.Footnote 63

In response to the appeal from the League of Red Cross Societies, East Germany lent Hungary seven iron lungs,Footnote 64 which travelled to their destination by train.Footnote 65 The British Red Cross immediately sent two iron lungs by air and prepared three more for transportation.Footnote 66 West Germany dispatched five iron lungs, fifteen poliomats (smaller respiratory devices developed by the Dräger company, developer of the iron lung)Footnote 67 and four pieces of respiratory equipment.Footnote 68 The Swedish Red Cross dispatched six respiratory devices and ten mucus aspirators,Footnote 69 key equipment in preventing infections in polio patients with respiratory paralysis. The iron lungs and devices arrived by air in Vienna and were transported by Malév Hungarian Airlines to Budapest with the coordination of the Austrian and Hungarian Red Cross societies.

Hungarian patients with respiratory paralysis were not exclusively dependent on loans and donations from international agencies and foreign governments. In fact, a locally developed and produced machine called the Electrospirator soon became the most widely used device. The result of a technology transfer from one medical speciality to another, from one side of the Iron Curtain to the other, the Electrospirator became a central element in the life of many patients.

During an especially severe polio epidemic in Copenhagen in 1952, Dr Alexander Lassen, chief physician at the Blegdam hospital, faced an influx of respiratory paralysis cases in unprecedented numbers and sought the help of anaesthesiologists to find a solution to the problem of the meagre number of respiratory machines.Footnote 70 A common procedure in anaesthesiology, applying positive pressure ventilation through the trachea, became an innovative method in polio treatment and went on to have a significant effect on the overall treatment of respiratory paralysis. The most important trait of this type of ventilation was that it was conducted through the trachea, which made getting rid of mucus easier, thereby lowering the risk of infection. However, the initial version was manually operated during the Copenhagen epidemic, mainly by medical students. This worked as an emergency measure, but required many staff to operate in the long run.

Using manpower in extreme ways in cases of emergency was not unusual in the history of polio, especially when it came to respiratory paralysis. An otherwise healthy-looking child or young adult suddenly unable to breathe was a shocking and powerful image that mobilised resources to exhaustion and shaped public health policies and medical practices. In his book Beginnings Count, David J. Rothman argues that the personal choices of doctors and the moral imperative of trying to help each and every case of respiratory paralysis with iron lungs, regardless of the efficiency of the technology or the prognosis of the particular patient, formed ideas about access to medical care.Footnote 71 While Rothman analyses a ‘democratisation’ process of technology use and expectations and concludes that such ideas could be counterproductive from a medical perspective, the Hungarian case raises different issues. In an economy of shortage, the question of whether to use a certain medical technology, in this case the iron lung, never came up. The dilemma was, rather, how to make the best use of given resources and maximise access to the available technology.

Dr Kiss Ákosné, who later became head of the respiratory ward at the Heine-Medin Hospital, considered the dramatic story of a relative who contracted polio to have shaped her medical career. In 1946, two years before the first iron lung was to arrive in Hungary, the young doctor’s distant relative fell ill on her sixteenth birthday and became paralysed first in the legs, then in the arms and finally in her respiratory muscles.

Since in these cases you could never tell if the respiratory paralysis would last five hours, three days, or a month … Three of us, another doctor, a pianist cousin and I tried to help, like relay horses, with the Silvester method, the most efficient method available then.Footnote 72

This way of artificial respiration, so often pictured in films, involved raising the patient’s arm above her head to induce air into the lungs and pressing them down on her chest for exhalation.Footnote 73 It was a huge physical strain on both the givers and the receiver. The efforts of the doctors and friends lasted one and a half days, by which time the girl’s skin on her forearms and chest was so damaged from the continuous friction that she could no longer stand the pain and begged them to stop. The young doctor could do nothing but arrange a morphine injection to ease the girl’s struggle as she died.Footnote 74

With such alternatives at hand, similarly to his Western colleagues, Boda started working on the mechanisation of the new Danish respiratory method in 1953. Iron lungs were scarce in Hungary and the epidemic of 1952, along with epidemic patterns all over Europe and beyond, made many physicians wary that epidemic crises were looming in the near future. Boda’s first attempt was an ‘inspirator’, based on glass technology and completed the same year. He encountered a Swedish version, the Engström respirator, for the first time on his trip to Switzerland in 1954, which gave him new momentum for developing his own device.Footnote 75 In cooperation with Pál Kerekes, an engineer at the Research Equipment Manufacturing Company of the Hungarian National Academy of Sciences, Boda built his final version and named it Electrospirator. The device was later patented and manufactured for export.Footnote 76 In the late 1950s, domestic iron lung production started, along with Electrospirators and rocking beds. By 1963 a wide variety of machines were in use in Hungary,Footnote 77 some of which, mostly Electrospirators and one iron lung, were continuously used until the early 2000s in the respiratory ward.Footnote 78

The challenge that respiratory paralysis posed to public health systems was the same irrespective of ideological stance or political alignment. Both East and West struggled with the prospect of the sudden need for these costly and complicated machines in time of epidemic crises. Scientists and engineers on both sides of the Iron Curtain worked on similar projects at a parallel pace in order to solve the problem of providing breath to paralysed patients. As such, it would be too simplistic to see the arrival of iron lungs in Hungary as a story of technological transfer from West to East. Neither was it a story of Western countries providing aid to make up for Eastern insufficiencies. Instead, in this network of assistance, originally conceived in the West, all countries participated as potential givers and takers. It was easy to see that polio did not distinguish between capitalism and socialism when it came to outbreaks.

The Heine-Medin Hospital and the ICRC

It was the fact that polio outbreaks straddled the Iron Curtain and cut across political systems and regimes that contributed to the continued investment in the disease throughout the 1950s in Hungary. From the perspective of polio, the revolution was less of a watershed event than it is usually considered. This is the reason why the Heine-Medin Hospital, mentioned in the beginning of this chapter, was able to survive its founder and flourish in the years of political retribution following the revolution. At the same time, the revolution opened windows of opportunity in terms of pursuing public health agendas and access to aid; nevertheless this, too, appears different through the lens of polio. The various ways in which the hospital mobilised connections, initiated international donations and engaged with the ICRC sheds light on the agency of the actors involved, and thereby provides an excellent example of the way interventions by international organisations in political and social upheaval play out on the ground.

One of the main sites of international aid in Hungary in 1956 was the Heine-Medin Hospital, established during the revolution. Although Imre Nagy signed off on the foundation of the hospital, the story of the institution that became a key player in polio treatment in Hungary began a few years earlier, in the Stalinist era. Dr László Lukács, an orthopaedic doctor and future director of the hospital, initiated the process in 1954, a year after poliomyelitis research began at the State Hygienic Institute (SHI) in cooperation with the epidemics department of the Health Ministry.Footnote 79

Lukács handed in a petition to the Health Ministry, pointing out the necessity of a national polio hospital and emphasising the urgency of establishing such an institution.Footnote 80 Lukács made his case by pointing out the insufficient resources for treating the increasing number of polio patients.Footnote 81 At the time, polio patients were mainly treated in the László infectious disease hospital in the acute phase, and most polio patients received restorative treatment in the Heine-Medin Rehabilitation Institute, established in 1947 with fifty beds under the direction of Dr Annna Szívós, which became part of the National Institute of Rheumatology and Physiotherapy in the early 1950s.Footnote 82 The Under-Secretary of Health supported Lukács’s proposal in a letter to the Health Minister,Footnote 83 and according to an internal document, the case of the future Heine-Medin Hospital was included in the second five-year plan to hold 150–200 beds.Footnote 84 However, for a while nothing happened: a year later, only twenty beds for polio patients were ordered to be issued to the Bókay János Children’s Hospital, where Lukács worked at the time.Footnote 85

The plans of Dr Lukács became a reality with the signature of Imre Nagy, and the hospital started working during the months of retribution. The institute, its acquired buildings and the appointment of Lukács as head of the hospital were reconfirmed on several occasions after the revolution was suppressed with the aid of the Soviet army.Footnote 86 The institute officially opened on 12 November 1956 with 160 beds, and was organised under the authority of the City of Budapest.Footnote 87

Even though the importance of the fight against polio overrode political changes, this heritage put the hospital in a delicate situation. A brief manuscript, which became the basis of the chapter in a volume celebrating the hospital’s fiftieth anniversary, gives insight into the political manoeuvring of its director, László Lukács, as he states:

The Health Minister proposed that the institution belong directly to the Ministry, but I could also choose to put it under the authority of the City of Budapest instead. I chose the latter… . The chief doctor of the city was Dr János Vikol, who had … firmly supported the cause of the disabled. The other reason was that I didn’t trust the leaders of the Health Ministry, I feared [undoing], a hope of the 200 leading party members with the intention of getting back the distinguished treatment of their children.Footnote 88

Although maintaining the new institution and its buildings after the revolution clearly required political skills, the fact that the doctor-director could choose the authority to which the institution should belong implies the great importance assigned to the cause, granting Lukács a certain political independence. Meanwhile, he also had to deal with the hostility of the political elite, who felt that the establishment of the hospital would curb their privileges in childcare.

The reason for this was that the Heine-Medin Hospital used five buildings that had previously belonged to the Rákosi MátyásFootnote 89 kindergarten, a childcare home for privileged party officials in the prestigious district of the Rózsadomb in the Buda hills. It is no coincidence that an institution founded during the 1956 revolution was established in buildings with such a history: this was a small, but obvious, attack on the hated political elite.

The houses were, for the most part, nationalised residences of the economic and political elite of another era. The villas were scattered in the most sought-after part of the city, among green lawns, small patches of woods and swimming pools. In many ways, they were ideal for the long-term care of disabled children, but they also threw up obstacles that were difficult to overcome.

First of all, the hospital’s location posed problems: reaching the relatively remote location on the hilltop without proper public transportation on poor-quality roadsFootnote 90 was often hard on staff and patients alike, neither of whom lived in the elegant neighbourhood. This was especially true in the early days. Public transportation came to a complete stop during the desperate street battles of the revolution, and it took months to reorganise trams and buses and to rebuild damage to the infrastructure. It could take nurses hours to reach their workplace on foot, even with the director giving them a ride as often as he could.Footnote 91

Getting children to the hospital was equally hard. In the fights of the revolution, the hospital’s only van was hit severely and had a gaping hole on the side and bottom. When transferring children from the infectious disease hospital to the Heine-Medin Hospital, nurses put infants into laundry baskets (along with the fresh laundry), which they tied to the inside of the van, and hoped for the best.Footnote 92 In later years, once in possession of more resources, the hospital organised a minibus to pick up children daily in the city centre for outpatient care – 4,500 on a monthly basis. Severely disabled outpatients were transported by two minivans door to door. Since the same vehicles were used to transport hospital patients between buildings (to X-ray, surgery, physical therapy, etc.), and were often under repair, these journeys often involved long waiting times.Footnote 93

The buildings themselves were never intended to house a hospital, let alone a treatment centre for disabled children. Steep, curving stairways and slippery floors made each day in the hospital challenging for staff, parents and children as they made their way between bedrooms and spaces of treatment.Footnote 94 When the hospital opened, the buildings were partially damaged from the war and the revolution. After the fighting settled down in the winter of 1956–57, the Hungarian army contributed by repairing the buildings and heating them.Footnote 95

The hospital was still in dire need of medical supplies. ‘The bad conditions prevailing in Hungary are affecting and hindering the beginning of our work and are causing us great difficulties’, wrote the director, Dr Lukács, in a letter to the Red Cross. ‘It is quite impossible to obtain supplies of equipment, especially instruments, in Budapest.’Footnote 96 Even basic necessities like bed linens and beds were scarce. Katalin Parádi remembers her first weeks in the hospital, not long after it opened. She was a teenager when she contracted the disease, an exception to the rule in Hungary, where the overwhelming majority of polio patients were under 3 years old.Footnote 97 Since polio was truly an ‘infantile paralysis’ in Hungary, the hospital arranged its meagre resources accordingly – leaving exceptional patients like Katalin without a room of their own, or even a bed. ‘They had only cots that they inherited from the childcare home, no proper beds for patients. I had to sleep in the same room with the little ones on a makeshift bed assembled of a couple of chairs.’Footnote 98

Soon, help came from the International Red Cross. Both official and personal avenues were utilised to procure crucial donations. First, the Acting Minister for Foreign Affairs, István Sebes, sent a letter to the Secretary-General of the United Nations in reply to the UN’s note ‘requesting data on the Hungarian people’s needs in medical supplies, foodstuffs and clothes from abroad’. In this, the minister gave a detailed list of urgent needs, including ambulances, insulin, gamma globulin, vitamins, surgical stitching materials, X-ray machines and iron lungs.Footnote 99 The request was forwarded to the Division of External Relations and Technical Assistance of the UN, which in turn forwarded it to the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC).

However, the general aid received from abroad was shared between all of the hospitals in the city and was mostly used to replenish stocks. It was not sufficient to equip a brand-new institution.Footnote 100 Thus, Lukács chose an unofficial, more targeted route to procure the necessary supplies that he needed for the treatment of the polio patients, now numbering more than 100, housed in the hospital: he mobilised his family.

An extensive exchange of letters between the American Red Cross, the ICRC and Hungarian physicians reveals the route of request for aid. On 28 December 1956, the American Red Cross contacted the ICRC with the following information:

Dr László Lukács, chief surgeon of the Metropolitan Heine-Medin Institute of Budapest … has been in telephone communication with his wife, who is now in the United States on a visitor’s visa, staying with her brother, a student at the Eastern Baptist Seminary in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. In these telephone conversations, he spoke of the urgent need for Salk vaccine and essential operating room equipment for his hospital, equipment that had been lost when the hospital was moved from its previous location … Since then, the brother-in-law has been trying to raise funds for the purchase of operating room equipment.Footnote 101

It is uncertain when and why Lukács’s wife went to the United States, and if the trip took place before or during the revolution. It is certain that she was back in Hungary in 1959, as she was present as a member of the Women’s Council at the annual school exams that were organised for the children staying and studying in the hospital.Footnote 102 This suggests that she was not considered to be an unwanted element of society by the communist government and could return safely to Hungary – perhaps thanks to the political connections of her husband.

The ICRC replied to the letter in mid-January with the promise of investigating it through their general delegate for relief in Hungary.Footnote 103 By the end of February 1957, a detailed report about the hospital and its needs was assembled by ICRC officials and was forwarded to the American Red Cross.Footnote 104 The report, containing an assessment by the head of medical services of the Hungarian Relief Action of the ICRC, highlighted: ‘The poor and makeshift character of the therapeutic equipment stands out in sharp contrast to the modern fittings of the houses … There is also a shortage of qualified staff.’ The reason for urgency was the growing importance of the hospital in polio care in Hungary. Within mere months of its opening, without sufficient equipment or supplies, the patient load was growing fast. ‘There are now 130 beds, all of them occupied. Except for two adults, this is purely a children’s centre … Besides the patients who live in, mostly children from the provinces, a further 200 children from Budapest visit the hospital every day for treatment.’Footnote 105

This report, with detailed lists of requirements from different respiratory devices to surgical equipment, reached the American Red Cross too late. By the time the letter arrived, Lukács’s brother-in-law had managed to secure some of the much-needed equipment and had sent it directly to the hospital.Footnote 106 However, the Red Cross was soon able to take a more active part in organising polio aid; when the 1957 epidemic rolled into Hungary, the ICRC, the League of the Red Cross Societies and national Red Cross societies coordinated their efforts in providing polio aid to the country.

Much of the equipment sent by Red Cross societies found its way to the Heine-Medin Hospital. The Swedish Red Cross and the Swedish Rädda Barnen society for child relief concentrated especial effort on this institution.Footnote 107 The hospital received important donations, such as rocking beds, hospital beds, bed linen, blankets, surgical equipment and medicine. The donations were vital and more than appreciated – hospital workers called the high-quality blankets Swedish blankets for decades to come.Footnote 108 In this sense, Swedish international aid achieved one of its central goals, as historian Ann Nehlin has argued: exporting and promoting Swedish standards, values and expertise on childcare.Footnote 109 The director of the hospital developed a personal relationship with Anna Ma Toll, Rädda Barnen’s representative in Hungary, and remained in contact even after the Swedish delegation had to leave the country following the fall of the revolution. The organisation continued to support the hospital with surgical equipment, bed linen and medicine well into the late 1950s.Footnote 110

Figure 2.2 Aid arriving from the Swedish Rädda Barnen. Hongrie 1956–57. Budapest. V-P-HU-N-00023–01 ICRC Archives (ARR).

The Heine-Medin Hospital was the only institution in the country that exclusively provided specialised medical care for polio patients, and it quickly became the largest national centre for treatment by the end of the 1950s. Its establishment, from the foundational document to its physical location and the medical equipment it contained, was a profound product of the 1956 revolution. The same uprising that created chaos in politics, society and public health also created unique opportunities, of which a wide range of individuals took advantage in order to satisfy long-standing needs in polio treatment.

The capability of hospital directors, physicians and their family members to act quickly in the ensuing turmoil came from the realisation that they were part of a significant Cold War event. The procurement of life-saving devices and medical equipment was made possible by the international limelight thrown on this small Eastern European country in 1956. However, the arrival of iron lungs and the establishment of the Heine-Medin Hospital was not an intended and structural part of international aid to the country at the time. Rather, these Hungarian agents of internationalism tapped into the existing and emerging practices of international organisations dealing with political and humanitarian crises.

They also drew on transnational experiences that overarched Cold War barriers: the scarcity of specialised and high-tech medical equipment and the common understanding of a disease that did not halt at ideological and political dividing lines. It was the local poverty of a post-war Eastern European country that coincided with a global shortage and, in this cross-section, initiated innovation in respiration technology and in procuring essential medical equipment. In this sense, international aid during the revolution, with regard to epidemic management, was highly individualised and far from a one-way affair. Hungarian professionals actively utilised a particular political moment in the Cold War to address both acute and structural needs in public health and healthcare. Moreover, the networks they built proved to be invaluable as polio epidemic outbreaks erupted with renewed force in the following years.