1. Introduction

Since the publication of the Stanford Watershed Model by Crawford & Linsley (Reference Crawford and Linsley1966), a wide range of computational models of catchment-scale hydrology have been developed (Singh & Frevert Reference Singh and Frevert2003). Indeed, over two hundred models have been identified in the extensive review by Peel & McMahon (Reference Peel and McMahon2020).

Such computational models are primarily designed in order to predict the evolution of surface and subsurface flow in a particular river basin given the input precipitation via rainfall or snowfall. These so-called rainfall-runoff models are often divided into three classes: empirical, conceptual and physical (Sitterson et al. Reference Sitterson, Knightes, Parmar, Wolfe, Avant and Muche2018); this last category of physical models involves those that are developed from the known physical principles of hydrodynamics. For instance, the Richards equation is commonly used to model the subsurface flow through the saturated or unsaturated soil, while the Saint Venant equation is used to model the overland and the channel flow. For a detailed introduction, see Shaw et al. (Reference Shaw, Beven, Chappell and Lamb2010). Such governing equations form the foundation of many currently used computational integrated catchment models, e.g. MIKE SHE (Abbott et al. Reference Abbott, Bathurst, Cunge, O'Connell and Rasmussen1986a,Reference Abbott, Bathurst, Cunge, O'Connell and Rasmussenb), HydroGeoSphere (Brunner & Simmons Reference Brunner and Simmons2012), ParFlow (Kollet & Maxwell Reference Kollet and Maxwell2006) and OpenGeoSys (Kolditz et al. Reference Kolditz2012).

However, in contrast to computational studies, there seems to have been more limited work on the systematic mathematical analysis of the fundamental principles of coupled surface–subsurface catchment-scale models. A proper mathematical formulation can allow us to better understand the importance of parameters, establish the limits of simplifications used in computational models and develop analytical or semi-analytical solutions in certain scenarios.

1.1. On the development and benchmarking of computational models

The Stanford Watershed Model IV is a conceptual model, which is considered to be amongst the earliest attempts to computationally model the entire hydrological cycle. Its publication resulted in the subsequent development of an enormous number of independent computational models (Donigian & Imhoff Reference Donigian and Imhoff2006). However, further computational power was needed before the first physically based models were implemented. Notable early examples include TOPMODEL (Kirkby & Beven Reference Kirkby and Beven1979), MIKE SHE (Abbott et al. Reference Abbott, Bathurst, Cunge, O'Connell and Rasmussen1986a,Reference Abbott, Bathurst, Cunge, O'Connell and Rasmussenb) and IHDM (Institute of Hydrology Distributed Model, cf. Beven, Calver & Morris Reference Beven, Calver and Morris1987).

The abundance of independent catchment models results in a need to better understand their accuracy and differences. Within the industry, such models are typically assessed by comparing model predictions (usually after earlier calibration) with available data, such as river flow or groundwater depth measurements (see a detailed introduction to rainfall-runoff modelling by Beven Reference Beven2011). However, there is criticism, e.g. by Hutton et al. (Reference Hutton, Wagener, Freer, Han, Duffy and Arheimer2016), that the models in hydrology are often not reproducible. Beven (Reference Beven2018, p. 6) highlighted some fundamental issues that continue to exist in the state-of-the-art of catchment modelling. He noticed that:

Where model intercomparisons have been done, different models give different results, and it is often the case that the rankings of models in terms of performance will vary with the period of data used, site or type of application. This would seem to be a very unsatisfactory situation for the advancement of the science, especially when we expect that when true predictions are made, they will turn out to be at best highly uncertain and at worst quite wrong.

In response to this problem, many numerical methodologies for calibration, cross-validation and uncertainty estimation have been developed (see e.g. Beven & Binley Reference Beven and Binley1992; Gupta, Beven & Wagener Reference Gupta, Beven and Wagener2006). These methods allow us to assess, in a more unbiased way, the accuracy of the models. However, they do not necessarily point out the reason for potential inaccuracies. As Kirchner (Reference Kirchner2006) argued, advancing the science of hydrology requires developing not only models that match the available data, but models that are theoretically justified.

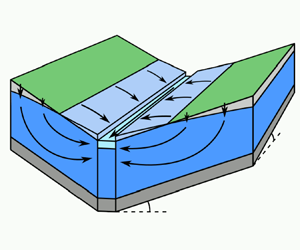

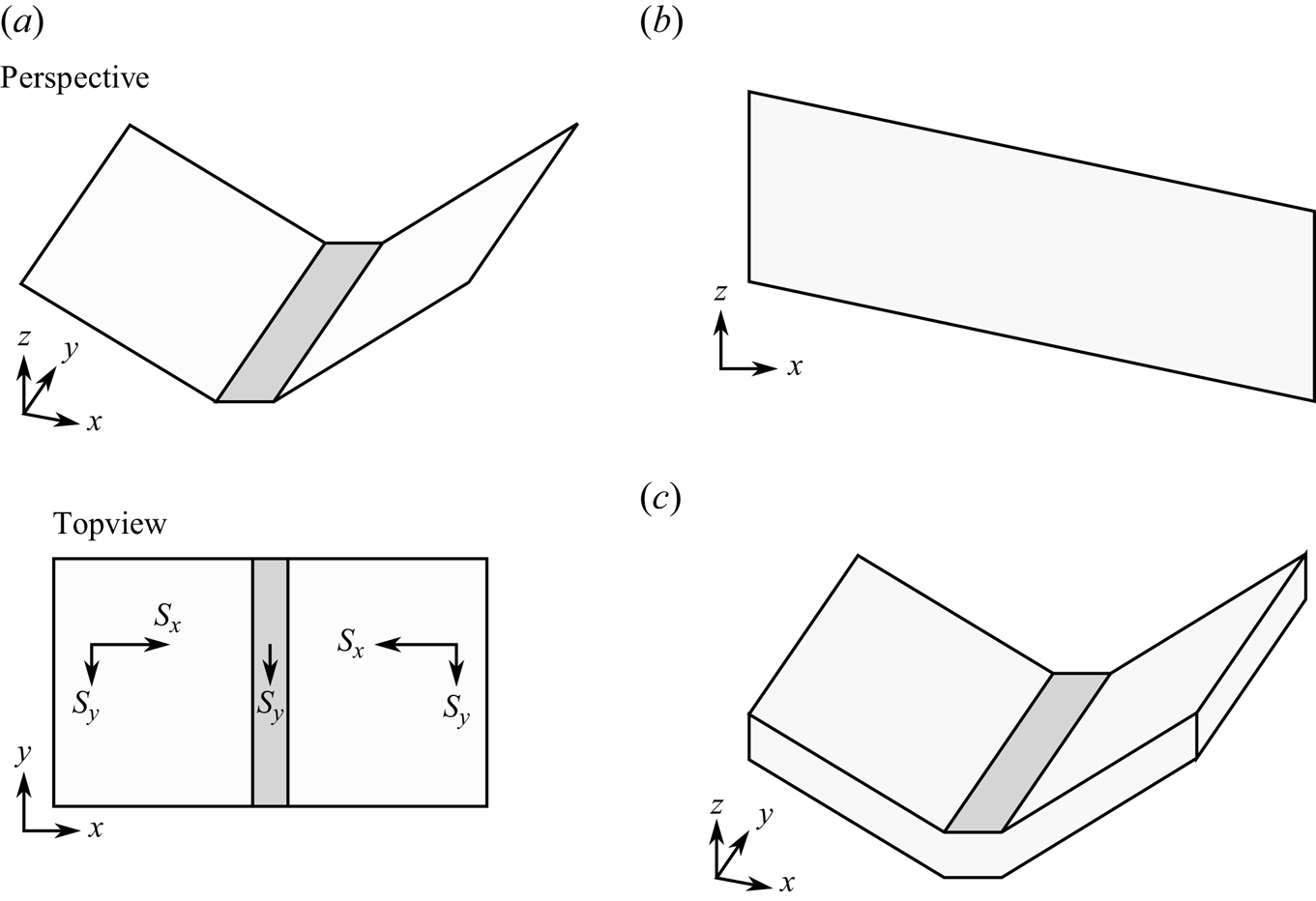

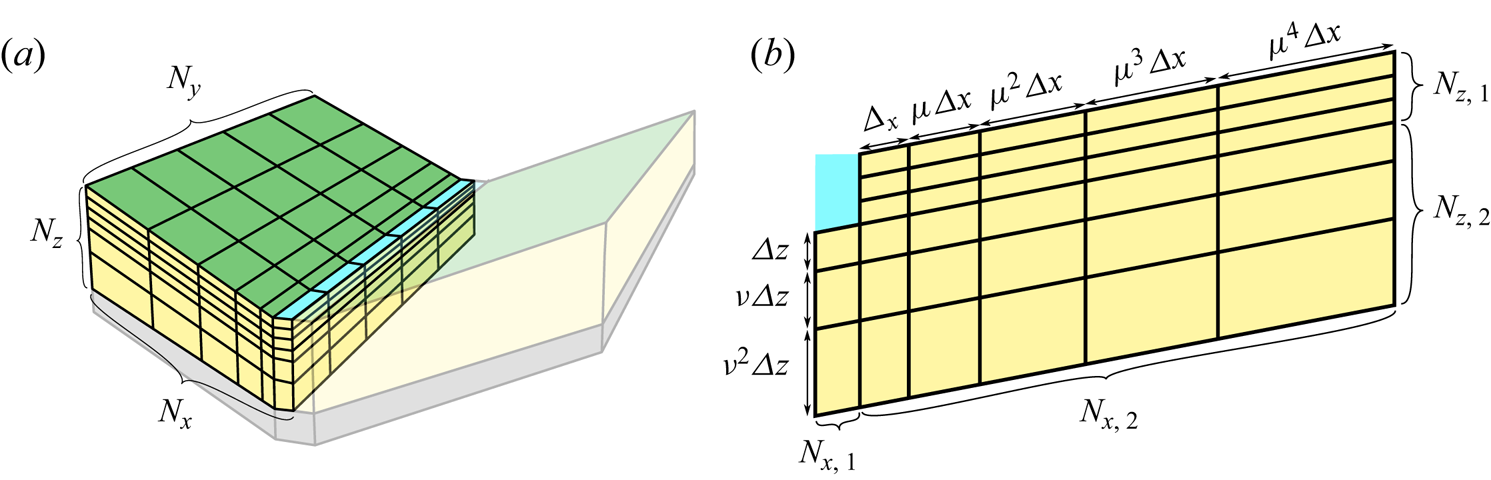

Independently, there has been an effort to develop simple (idealised) catchment geometries that can be used as benchmarks to assess the accuracy of integrated catchment models in fully controlled conditions. Kollet & Maxwell (Reference Kollet and Maxwell2006) used a tilted V-shaped catchment geometry (figure 1a) to compare predictions for overland flow given by four different hydrological catchment models with an analytical one-dimensional solution. Then, they introduced a simple two-dimensional hillslope (figure 1b), which they used to explore the sensitivity of an integrated ParFlow model for geometry settings (e.g. water table depth, hydraulic conductivity and soil heterogeneities). The same benchmark scenarios were used by Sulis et al. (Reference Sulis, Meyerhoff, Paniconi, Maxwell, Putti and Kollet2010) to compare ParFlow and CATHY models (Bixio et al. Reference Bixio, Orlandini, Paniconi and Putti2000). This study was followed by far more extensive intercomparison studies by Maxwell et al. (Reference Maxwell2014) and Kollet et al. (Reference Kollet2017), which used these and other benchmark scenarios to compare the results obtained using a wide range of integrated catchment models.

Figure 1. Illustration of the idealised catchment geometries developed in the works of Kollet & Maxwell (Reference Kollet and Maxwell2006) and Gilbert et al. (Reference Gilbert, Jefferson, Constantine and Maxwell2016). Geometries (a) and (c) represent a tilted V-shaped river valley with two hillslopes and a river in the middle, with the latter geometry introducing subsurface flow in the third dimension. Geometry (b) represents a single two-dimensional hillslope with a river channel located at the right boundary. (a) Two-dimensional tilted V-shaped catchment, (b) hillslope cross-section and (c) three-dimensional tilted V-shaped catchment.

In the meanwhile, simple catchment/hillslope scenarios have also been used to assess coupled surface and subsurface flow with other models – this includes examination of evapotranspiration (Kollet et al. Reference Kollet, Cvijanovic, Schüttemeyer, Maxwell, Moene and Bayer2009), atmosphere (Sulis et al. Reference Sulis, Williams, Shrestha, Diederich, Simmer, Kollet and Maxwell2017), biochemistry (Cui, Welty & Maxwell Reference Cui, Welty and Maxwell2014), the impact of climate change (Markovich, Maxwell & Fogg Reference Markovich, Maxwell and Fogg2016) and the effects of different types of heterogeneities, e.g. the heterogeneity of the land surface (Rihani, Chow & Maxwell Reference Rihani, Chow and Maxwell2015), soil properties (Meyerhoff & Maxwell Reference Meyerhoff and Maxwell2011) and even flow through fractures (Sweetenham, Maxwell & Santi Reference Sweetenham, Maxwell and Santi2017). The two studies by Jefferson et al. (Reference Jefferson, Gilbert, Constantine and Maxwell2015) and Gilbert et al. (Reference Gilbert, Jefferson, Constantine and Maxwell2016) introduced a three-dimensional tilted V-shaped catchment with a constant soil depth (figure 1c). The authors used this geometry to perform a sensitivity analysis of integrated catchment models – the first study by Jefferson et al. (Reference Jefferson, Gilbert, Constantine and Maxwell2015) focused on the energy flux terms, while the second by Gilbert et al. (Reference Gilbert, Jefferson, Constantine and Maxwell2016) studied the heterogeneity of soil permeability. In both studies, the sensitivity analysis results were used to obtain a certain level of dimensionality reduction by applying the active subspace method (Constantine Reference Constantine2015).

An open question remains, however, whether one can simplify the model and its parameter space based on the analysis of the governing equations (even in a simplified catchment scenario), rather than based on the numerical results; this could provide more rigorous insight into the limits of applicability of the above computational reductions.

Another aspect we shall investigate in this work concerns the study of key non-dimensional parameters characterising surface–subsurface hydrological processes. We highlight some prior works that have used non-dimensionalisation in order to analyse governing equations describing individual flow components: for example, this has been applied by Akan (Reference Akan1985) in the Saint Venant equations to study the water infiltration into the ground. It has also been used by e.g. Warrick, Lomen & Islas (Reference Warrick, Lomen and Islas1990), Warrick & Hussen (Reference Warrick and Hussen1993) and Haverkamp et al. (Reference Haverkamp, Parlange, Cuenca, Ross and Steenhuis1998) for the study of the one-dimensional Richards equation, describing water vertical infiltration through the unsaturated soil.

A notable work, in which non-dimensionalisation plays a prominent role for the case of coupled surface–subsurface models, was performed by Sivapalan, Beven & Wood (Reference Sivapalan, Beven and Wood1987), and focuses on the TOPMODEL scheme of Kirkby & Beven (Reference Kirkby and Beven1979). A similar study was performed by Calver & Wood (Reference Calver and Wood1991) for the IHDM model (Beven et al. Reference Beven, Calver and Morris1987). In particular, Calver & Wood (Reference Calver and Wood1991) define a list of ten dimensionless parameters, study the dependencies between selected parameters and discuss the properties of the hydrographs. However, the relevant scale of dimensionless parameters is not assessed in this latter work.

1.2. On the development of a simple benchmark model

The modern-day catchment hydrology is studied based on the simulation of complex integrated catchment models. So far, however, the authors have not found many comprehensive studies on the design and analysis of simple benchmark scenarios for coupled surface–subsurface catchment models. Our work in Part 1 (Morawiecki & Trinh Reference Morawiecki and Trinh2024) has initiated this task via a thorough examination of the typical parameter sizes. In this part, we focus on the design of a three-dimensional benchmark, study its typical dynamics and discuss its reduction to lower-dimensional models.

Compared with the existing literature, there are three novel elements in our study:

(i) Our benchmark scenario is posed on a simple geometry, but the surface/subsurface governing equations are posed in a general three-dimensional dimensionless form.

(ii) We use the dimensionless model to provide a rigorous argument behind the simplifications commonly used in computational hydrology. We discuss the reduction of a problem geometry to two dimensions in detail, and comment on the kinematic/dynamic wave approximation. We achieve this by setting clear conditions on the size of dimensionless parameters, and justify them based on the typical values of model parameters obtained in the previous part of our work (see table 1 from Part 1).

(iii) We use the benchmark model to numerically explore the impact of the remaining parameters on the system in response to intensive rainfall. Because we attempt to do this in a systematic and analytical way, this work also serves to set a more rigorous benchmark standard for future studies. For example, scaling laws are derived that may serve as a benchmark for other model schemes.

Note that our study is restricted to modelling the formation of storm flow during an intensive rainfall (Guérin et al. Reference Guérin, Devauchelle, Robert, Kitou, Dessert, Quiquerez, Allemand and Lajeunesse2019); however, similar benchmark scenarios can be considered in order to study other flow regimes. This may include, for instance, drought flow observed during a period without any rainfall (Brutsaert & Nieber Reference Brutsaert and Nieber1977), or a sudden drawdown drainage when a rapid change of water level occurs at the outlet (Sanford, Parlange & Steenhuis Reference Sanford, Parlange and Steenhuis1993).

We start by formulating a three-dimensional benchmark scenario in § 2, which is non-dimensionalised in § 3. In § 5 we show that this model can be reduced to a two-dimensional form by neglecting the subsurface and overland flow component in the ![]() $y$-direction. Following the numerical methodology from § 6, this model simplification is numerically assessed in § 7. The impact of each parameter in the resulting two-dimensional model is summarised in § 8, which is followed by the discussion in § 9.

$y$-direction. Following the numerical methodology from § 6, this model simplification is numerically assessed in § 7. The impact of each parameter in the resulting two-dimensional model is summarised in § 8, which is followed by the discussion in § 9.

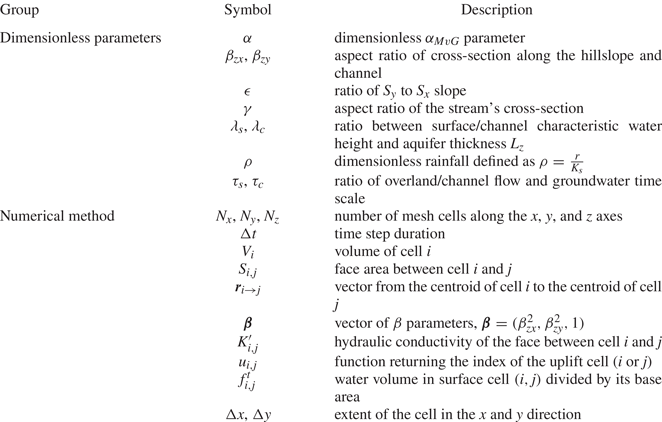

Symbols. There are many symbols in this work. For ease of reference, we provide a list of symbols in tables 2 and 3 in Appendix A.

2. Formulation of a simplified three-dimensional catchment model

In this section, we formulate a simplified catchment model, inspired by the infiltration-excess, saturation-excess and tilted V-shaped catchment scenarios from the benchmark study by Maxwell et al. (Reference Maxwell2014).

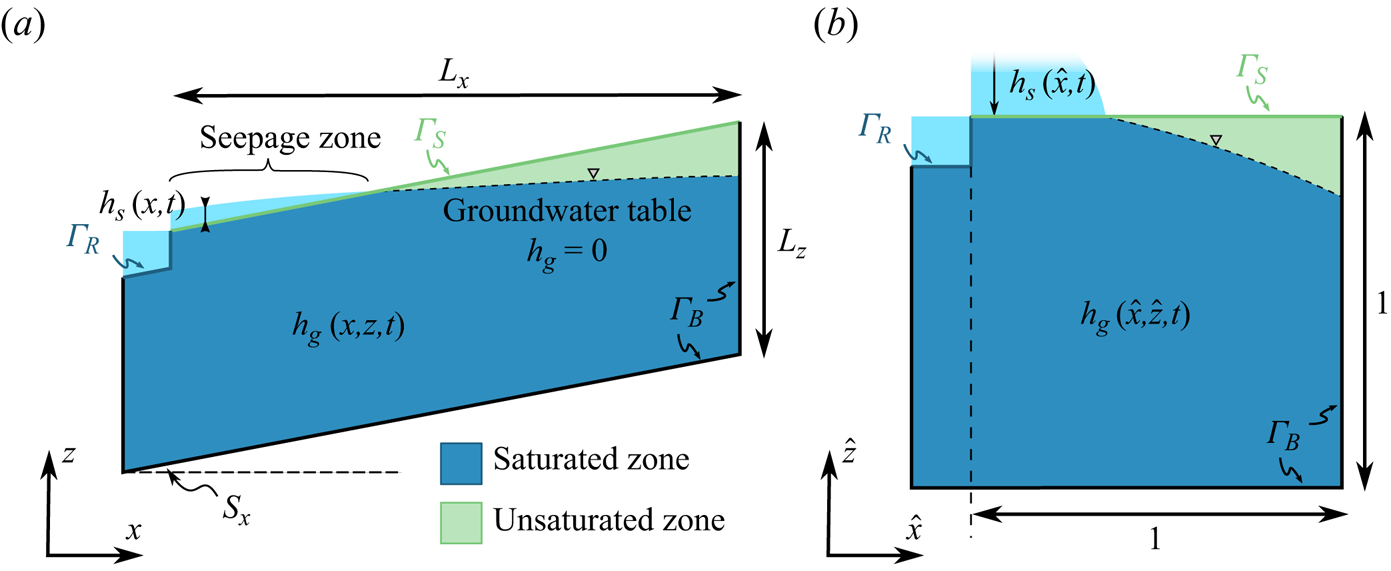

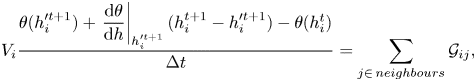

We introduce the following three scenarios, as depicted in figure 2.

(a) The V-shaped catchment. This scenario, shown in figure 2(a), represents a V-shaped catchment with a thick aquifer, where subsurface water is transferred both through the soil and through the underlying bedrock. The aquifer dimensions are

$L_x\times L_y\times L_z$, where

$L_x\times L_y\times L_z$, where  $L_z$ is the thickness of the permeable layer of the aquifer. The elevation gradient along the hillslope is denoted as

$L_z$ is the thickness of the permeable layer of the aquifer. The elevation gradient along the hillslope is denoted as  $S_x$, and along the direction of the river as

$S_x$, and along the direction of the river as  $S_y$. Similar to the V-shaped scenario studied by Maxwell et al. (Reference Maxwell2014), we shall assume that the channel has a constant width,

$S_y$. Similar to the V-shaped scenario studied by Maxwell et al. (Reference Maxwell2014), we shall assume that the channel has a constant width,  $w$, and zero depth,

$w$, and zero depth,  $d=0$. Later in § 5, we demonstrate that under certain conditions, the scenario reduces to largely two-dimensional dynamics along the hillslope.

$d=0$. Later in § 5, we demonstrate that under certain conditions, the scenario reduces to largely two-dimensional dynamics along the hillslope.(b) The deep aquifer. This scenario, shown in figure 2(b), represents a two-dimensional hillslope with a thick aquifer, where the subsurface water is transferred through both the soil and the underlying bedrock. Following the infiltration- and saturation-excess scenarios discussed in Maxwell et al. (Reference Maxwell2014), the channel is assumed to have a rectangular

$xz$ cross-section with width,

$xz$ cross-section with width,  $w$, and depth,

$w$, and depth,  $d$.

$d$.(c) The shallow aquifer. This scenario, shown in figure 2(c), represents a catchment with a low-productive aquifer, in which the subsurface water is transferred only through a thin soil layer. Mathematically, the geometry of the problem is equivalent to the deep aquifer scenario with

$L_z\ll L_x$. We analyse this scenario in Part 3.

$L_z\ll L_x$. We analyse this scenario in Part 3.

Figure 2. Simplified catchment geometry in the considered scenarios (not to scale). (a) V-shaped catchment scenario, (b) deep aquifer scenario and (c) shallow aquifer scenario.

The focus of work in this Part 2 is the study of the V-shaped catchment scenario and its reduction to a two-dimensional deep aquifer scenario. In Part 3, we shall demonstrate that under the additional restrictions of the shallow aquifer scenario, further analysis can be performed through a long wavelength reduction. In the V-shaped catchment scenario, an orthogonal coordinate system ![]() $(x, y, z)$ is chosen such that

$(x, y, z)$ is chosen such that ![]() $z$ is vertical and

$z$ is vertical and ![]() $y$ is directed along the channel. Using the reflection symmetry of the catchment, we can describe the catchment behaviour by only considering a hillslopes only on one side of the river.

$y$ is directed along the channel. Using the reflection symmetry of the catchment, we can describe the catchment behaviour by only considering a hillslopes only on one side of the river.

When formulating the governing equations for overland and subsurface flow, we are going to use a more convenient non-orthogonal coordinate system, where the axes ![]() $(\hat {x}, \hat {y}, \hat {z})$ are directed along the hillslope edges. Hence,

$(\hat {x}, \hat {y}, \hat {z})$ are directed along the hillslope edges. Hence, ![]() $\hat {x}$ is directed along the hillslope (

$\hat {x}$ is directed along the hillslope (![]() $\hat {x}=0$ representing the location of the channel),

$\hat {x}=0$ representing the location of the channel), ![]() $\hat {y}$ along the channel (

$\hat {y}$ along the channel (![]() $\hat {y}=0$ representing the location of the outlet) and

$\hat {y}=0$ representing the location of the outlet) and ![]() $\hat {z}$ vertically (

$\hat {z}$ vertically (![]() $\hat {z}=0$ representing the bottom of the aquifer). After the coordinate transformation, the entire catchment can be represented as a cuboid of dimensions

$\hat {z}=0$ representing the bottom of the aquifer). After the coordinate transformation, the entire catchment can be represented as a cuboid of dimensions ![]() $L_{\hat x} \times L_y \times L_z$. The following coordinate transformation is used:

$L_{\hat x} \times L_y \times L_z$. The following coordinate transformation is used:

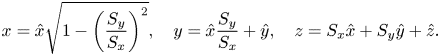

\begin{equation} x = \hat{x} \sqrt{1-\left(\frac{S_y}{S_x}\right)^2}, \quad y = \hat{x} \frac{S_y}{S_x} + \hat{y}, \quad z = S_x \hat{x} + S_y \hat{y} + \hat{z}. \end{equation}

\begin{equation} x = \hat{x} \sqrt{1-\left(\frac{S_y}{S_x}\right)^2}, \quad y = \hat{x} \frac{S_y}{S_x} + \hat{y}, \quad z = S_x \hat{x} + S_y \hat{y} + \hat{z}. \end{equation}

We introduced ![]() $L_{\hat x}$ to represent the catchment width along the

$L_{\hat x}$ to represent the catchment width along the ![]() $\hat x$ direction given as

$\hat x$ direction given as

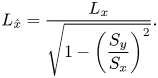

\begin{equation} L_{\hat x}=\frac{L_x}{\sqrt{1-\left(\dfrac{S_y}{S_x}\right)^2}}. \end{equation}

\begin{equation} L_{\hat x}=\frac{L_x}{\sqrt{1-\left(\dfrac{S_y}{S_x}\right)^2}}. \end{equation}The land surface in this geometry corresponds to

Note that real-world systems are characterised by different levels of heterogeneity of the surface, soil, and parent material properties. Here, in order to construct a minimal model, we consider properties to be homogeneous; this is similar to the assumptions made by Maxwell et al. (Reference Maxwell2014). Thus, the surface is assumed to have uniform roughness, and the properties of soil and rock layer are assumed to be homogeneous, i.e. have a uniform hydraulic conductivity and water-retention curve. Also, we assume that the soil and bedrock do not include the presence of macropores and fractures, which would lead to the formation of preferential flow – see more in the reviews by Bouma (Reference Bouma1981) and Neuzil & Tracy (Reference Neuzil and Tracy1981). Because of the last assumption, the model may not properly represent the infiltration through the unsaturated zone in many of the real-world systems. As noted e.g. by Beven & Germann (Reference Beven and Germann2013), including these effects in the model may significantly affect the time scale of infiltration.

2.1. Asymptotic limits of geometrical parameters

It is convenient to discuss the asymptotic limits of the key non-dimensional parameters that characterise the geometry. First, we have the slope ratios between the channel and hillslope directions

which for a typical UK catchment is ![]() $\epsilon \in [0.13,0.25]$ (the estimates represent the interquartile range based on parameters characterising over

$\epsilon \in [0.13,0.25]$ (the estimates represent the interquartile range based on parameters characterising over ![]() $1200$ UK catchments, values of which were estimated in Part 1 (here the first quartile is

$1200$ UK catchments, values of which were estimated in Part 1 (here the first quartile is ![]() $0.13$, and the third quartile is

$0.13$, and the third quartile is ![]() $0.25$)). We also have the aspect ratio between the catchment height and the catchment dimension along the river

$0.25$)). We also have the aspect ratio between the catchment height and the catchment dimension along the river

which for a typical UK catchment is ![]() $\beta _{zy}\in [0.0007, 0.025]$. Finally, we have the aspect ratio between the catchment height and the catchment length along the hillslope

$\beta _{zy}\in [0.0007, 0.025]$. Finally, we have the aspect ratio between the catchment height and the catchment length along the hillslope

which for a typical UK catchment is ![]() $\beta _{zx}\in [0.1,2.1]$. Note that as

$\beta _{zx}\in [0.1,2.1]$. Note that as ![]() $\beta _{zy}/\beta _{zx} \to 0$, we get long catchments with a width much shorter than their length, while for

$\beta _{zy}/\beta _{zx} \to 0$, we get long catchments with a width much shorter than their length, while for ![]() $\beta _{zy}/\beta _{zx} \to \infty$, we get short catchments with a width much longer than their length.

$\beta _{zy}/\beta _{zx} \to \infty$, we get short catchments with a width much longer than their length.

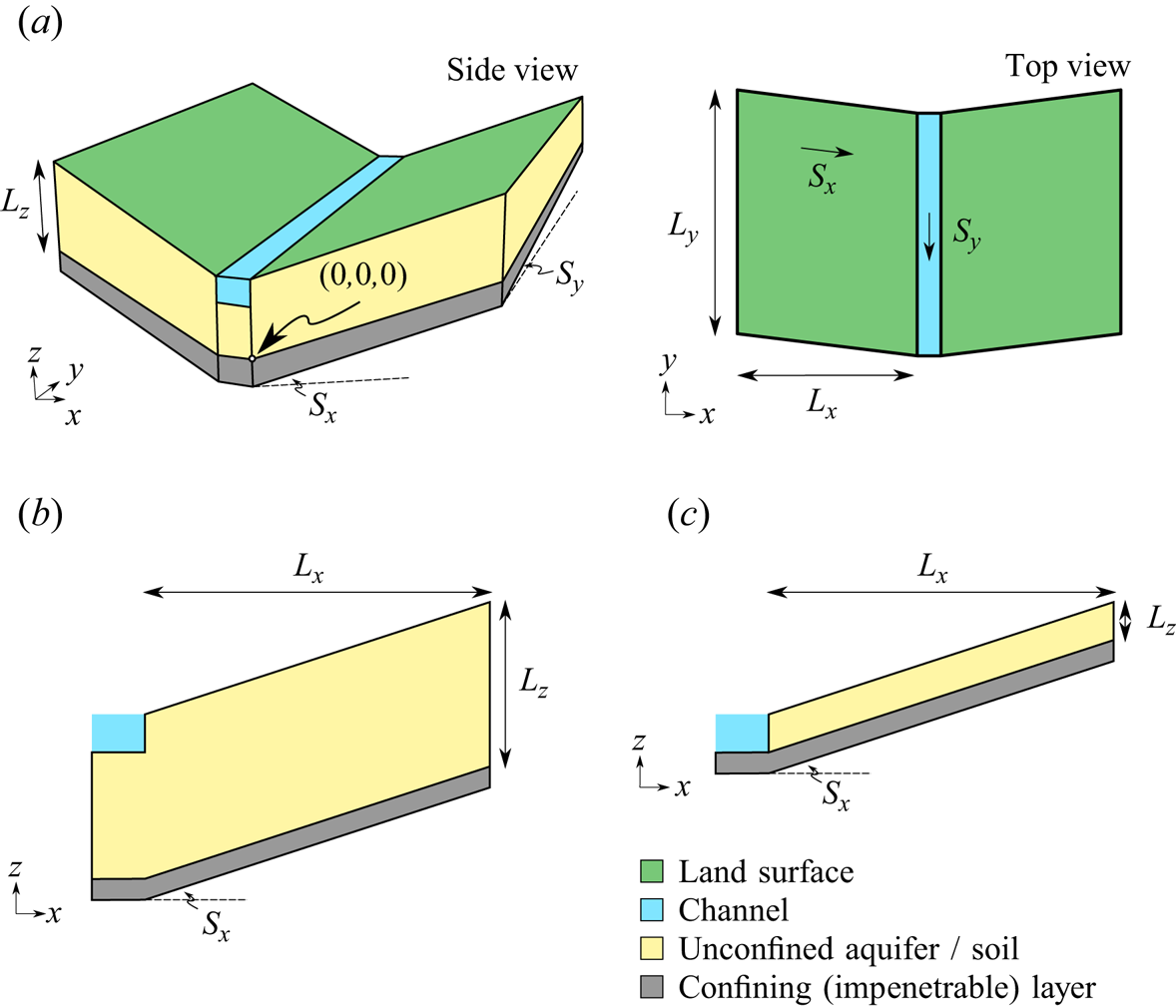

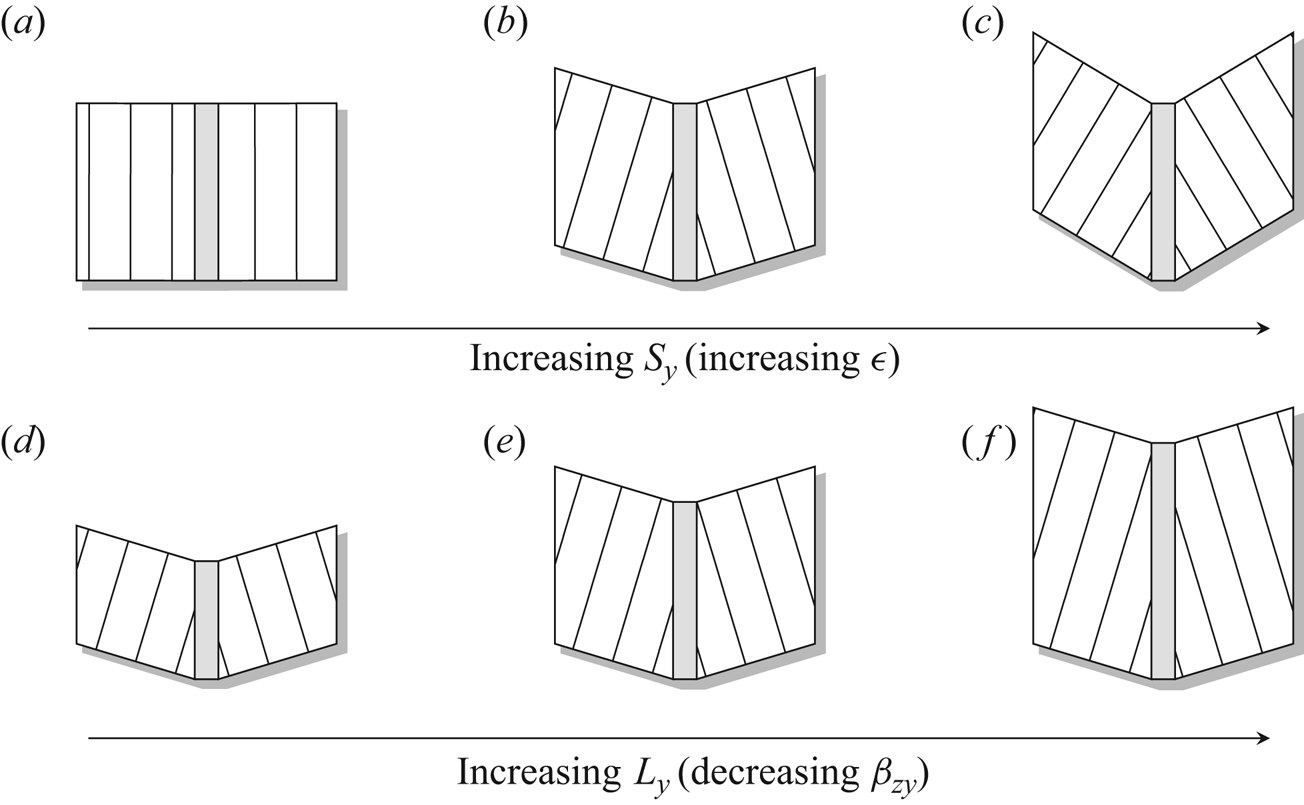

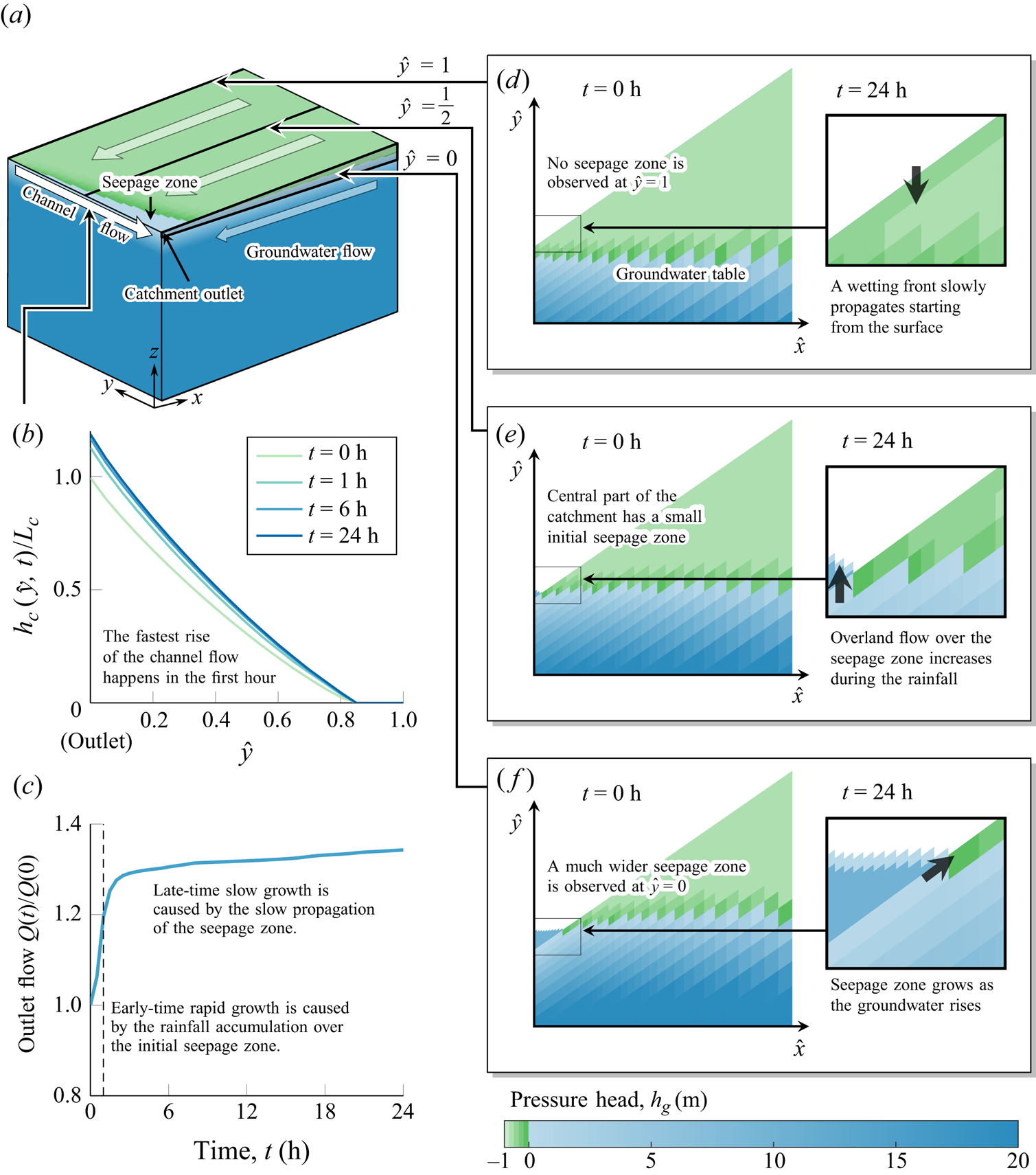

The impact of these two parameters on the catchment geometry is schematically presented in figure 3. Here, we draw lines of constant topographic elevation on a projection of the catchment onto ![]() $z = 0$. Note that, for example in figure 3(a) for

$z = 0$. Note that, for example in figure 3(a) for ![]() $S_y = 0$, surface and subsurface flow will typically occur in the

$S_y = 0$, surface and subsurface flow will typically occur in the ![]() $x$ direction, perpendicular to the river direction. In contrast, for figure 3(c), we may expect to observe a significant flow component parallel to the river direction.

$x$ direction, perpendicular to the river direction. In contrast, for figure 3(c), we may expect to observe a significant flow component parallel to the river direction.

Figure 3. These illustrations provide a guide to understand the impact of changing values of the slope, ![]() $S_y$ (a–c), and length,

$S_y$ (a–c), and length, ![]() $L_y$ (d–f) on our V-shaped catchment geometry (the channel is shaded). Lines of constant elevation of the topography are represented with dashed lines, drawn on top of a projection of the catchment onto

$L_y$ (d–f) on our V-shaped catchment geometry (the channel is shaded). Lines of constant elevation of the topography are represented with dashed lines, drawn on top of a projection of the catchment onto ![]() $z = 0$. By the definition of a catchment, the top and bottom boundaries are perpendicular to lines of constant elevation (since an unperturbed flow will follow lines of the steepest descent). These dashed lines help to visualise the geometry of the later contour plots.

$z = 0$. By the definition of a catchment, the top and bottom boundaries are perpendicular to lines of constant elevation (since an unperturbed flow will follow lines of the steepest descent). These dashed lines help to visualise the geometry of the later contour plots.

It is important to remember that, since our interest is in the study of the benchmark model, we are not necessarily limited to studying only physical regimes. That is, it is still interesting to study the asymptotic limits so that we can establish the qualitative trends.

2.2. Relationship to Maxwell et al. (Reference Maxwell2014)

Here, we briefly outline how the scenarios introduced above relate to the scenarios presented in the benchmark analysis of Maxwell et al. (Reference Maxwell2014).

In §§ 4.1 and 4.2, Maxwell et al. (Reference Maxwell2014) introduce two scenarios called the infiltration excess and saturation excess, respectively. In the infiltration scenario, precipitation exceeds the saturated soil conductivity (![]() $r>K_s$). Only part of the precipitation infiltrates through the soil, while the remaining part accumulates at the surface to form an overland flow (the so-called Horton overland flow). In the saturation-excess scenario (

$r>K_s$). Only part of the precipitation infiltrates through the soil, while the remaining part accumulates at the surface to form an overland flow (the so-called Horton overland flow). In the saturation-excess scenario (![]() $r< K_s$), overland flow is not generated unless the entire soil becomes fully saturated.

$r< K_s$), overland flow is not generated unless the entire soil becomes fully saturated.

Both scenarios are posed on a single hillslope, which represents a thin layer of soil (![]() $L_z=5$ m) with a slope following the

$L_z=5$ m) with a slope following the ![]() $x$ direction, while the river is assumed to have a fixed surface water height. Thus, this geometry represents the shallow aquifer scenario shown in figure 2, where the flow takes place only in a thin layer of the soil. Note that this geometry does not include water infiltration to the deeper permeable layers of the parent material (as in the deep aquifer scenario in figure 2), which is an effect that characterises the majority of the real-world aquifers (note a small area of aquifers without the groundwater on the UK map in figure 4 from Part 1).

$x$ direction, while the river is assumed to have a fixed surface water height. Thus, this geometry represents the shallow aquifer scenario shown in figure 2, where the flow takes place only in a thin layer of the soil. Note that this geometry does not include water infiltration to the deeper permeable layers of the parent material (as in the deep aquifer scenario in figure 2), which is an effect that characterises the majority of the real-world aquifers (note a small area of aquifers without the groundwater on the UK map in figure 4 from Part 1).

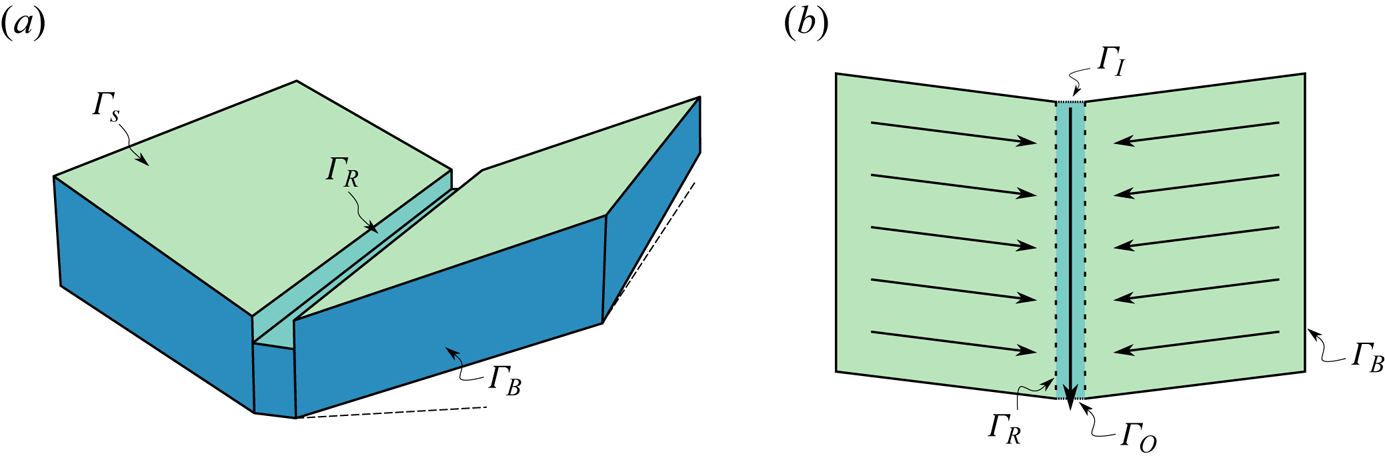

Figure 4. Boundaries defined for the V-shaped tilted catchment. (a) Boundaries for the subsurface flow and (b) boundaries for the surface flow.

A second limitation of the geometries considered by Maxwell is that there is no slope along the river, which drives the flow down the river valley. Although the authors included the slope perpendicular to the hillslope in a separate scenario introduced in their § 4.3 (V-shaped catchment), this benchmark scenario does not include subsurface modelling; therefore, the water infiltration into the soil was not studied.

Our scenarios in this work combine the above two elements, i.e. groundwater flow through deep aquifers and slope both perpendicular and along the river. Therefore, we consider a V-shaped catchment with an additional ![]() $z$-dimension allowing the saturation to vary with depth, as in the hillslope scenario. The need to introduce a tilted coordinate system comes from the fact that the elevation gradient (determining the direction of surface flow) is not perpendicular to the river, since it must have a small component along the

$z$-dimension allowing the saturation to vary with depth, as in the hillslope scenario. The need to introduce a tilted coordinate system comes from the fact that the elevation gradient (determining the direction of surface flow) is not perpendicular to the river, since it must have a small component along the ![]() $y$-axis. In order to satisfy the no-surface flow boundary condition at the catchment boundary, the bottom and top boundaries of the hillslope are thus inclined by a small angle,

$y$-axis. In order to satisfy the no-surface flow boundary condition at the catchment boundary, the bottom and top boundaries of the hillslope are thus inclined by a small angle, ![]() $\phi =\mathrm {asin}(S_y/S_x)$, relative to the rectangular domain in the infiltration- and saturation-excess scenarios.

$\phi =\mathrm {asin}(S_y/S_x)$, relative to the rectangular domain in the infiltration- and saturation-excess scenarios.

Last but not least, we use the typical catchment parameters as estimated in Part 1; note that these values can be significantly different from those numerical values used in the work of Maxwell et al. (Reference Maxwell2014). Based on our simulations, we observed that if one were to use the parameter values given by Maxwell et al. (Reference Maxwell2014), this would lead to unrealistic steady states, where the seepage covers almost the entire catchment (even for relatively low levels of mean precipitation).

3. Governing equations (dimensional)

We begin with the dimensional model. As introduced in § 2 of Part 1, we consider three types of flow: the subsurface flow (the three-dimensional (3-D) Richards equation), the overland flow (the 2-D Saint Venant equations) and the channel flow (1-D Saint Venant equation). In this section, we present governing equations for each of the flow components in our benchmark scenario, together with the corresponding boundary conditions. General reviews of these governing equations can be found in the works of Farthing & Ogden (Reference Farthing and Ogden2017), Schaake (Reference Schaake1975) and references therein.

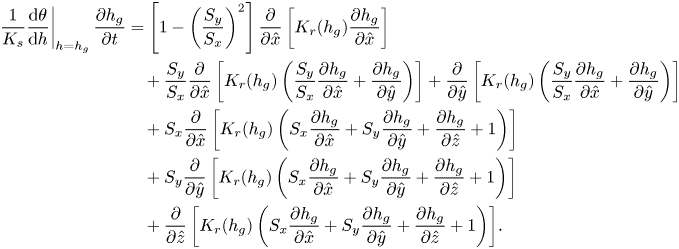

3.1. Three-dimensional Richards equation for the subsurface flow

The subsurface flow ![]() $\boldsymbol {q_g}(x,y,z,t)$ depends on the pressure head

$\boldsymbol {q_g}(x,y,z,t)$ depends on the pressure head ![]() $h_g(x,y,z,t)$. Its evolution in time

$h_g(x,y,z,t)$. Its evolution in time ![]() $t$ is commonly modelled using a 3-D Richards equation (see e.g. Dogan & Motz Reference Dogan and Motz2005; Weill, Mouche & Patin Reference Weill, Mouche and Patin2009), which is given by

$t$ is commonly modelled using a 3-D Richards equation (see e.g. Dogan & Motz Reference Dogan and Motz2005; Weill, Mouche & Patin Reference Weill, Mouche and Patin2009), which is given by

Here, ![]() $\boldsymbol {\nabla }=({\partial }/{\partial x},{\partial }/{\partial y}, {\partial }/{\partial z})$ is a standard nabla operator,

$\boldsymbol {\nabla }=({\partial }/{\partial x},{\partial }/{\partial y}, {\partial }/{\partial z})$ is a standard nabla operator, ![]() $K_s > 0$ is the saturated soil conductivity and

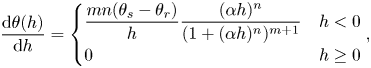

$K_s > 0$ is the saturated soil conductivity and ![]() ${\mathrm {d}\theta (h_g)}/{\mathrm {d} h_g}$ is the so-called specific moisture capacity. We assume that the volumetric water content

${\mathrm {d}\theta (h_g)}/{\mathrm {d} h_g}$ is the so-called specific moisture capacity. We assume that the volumetric water content ![]() $\theta (h_g)$, and relative hydraulic conductivity

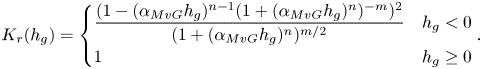

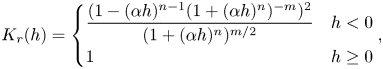

$\theta (h_g)$, and relative hydraulic conductivity ![]() $K_r(h_g)$ are functions of the pressure head given by the Mualem–van Genuchten (MvG) model (Van Genuchten Reference Van Genuchten1980)

$K_r(h_g)$ are functions of the pressure head given by the Mualem–van Genuchten (MvG) model (Van Genuchten Reference Van Genuchten1980)

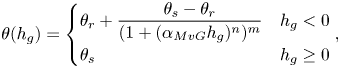

$$\begin{gather} \theta(h_g) = \begin{cases} \theta_r+\dfrac{\theta_s-\theta_r}{(1+(\alpha_{MvG}h_g)^n)^m} & h_g<0 \\ \theta_s & h_g\ge0 \end{cases}, \end{gather}$$

$$\begin{gather} \theta(h_g) = \begin{cases} \theta_r+\dfrac{\theta_s-\theta_r}{(1+(\alpha_{MvG}h_g)^n)^m} & h_g<0 \\ \theta_s & h_g\ge0 \end{cases}, \end{gather}$$ $$\begin{gather}K_r(h_g) = \begin{cases} \dfrac{(1-(\alpha_{MvG}h_g)^{n-1}(1 +(\alpha_{MvG}h_g)^n)^{-m})^2}{(1+ (\alpha_{MvG}h_g)^n)^{m/2}} & h_g<0 \\ 1 & h_g\ge0 \end{cases}. \end{gather}$$

$$\begin{gather}K_r(h_g) = \begin{cases} \dfrac{(1-(\alpha_{MvG}h_g)^{n-1}(1 +(\alpha_{MvG}h_g)^n)^{-m})^2}{(1+ (\alpha_{MvG}h_g)^n)^{m/2}} & h_g<0 \\ 1 & h_g\ge0 \end{cases}. \end{gather}$$

Here, the value of ![]() $h_g=0$ corresponds to the pressure head at the groundwater table surface, which separates the fully saturated zone (

$h_g=0$ corresponds to the pressure head at the groundwater table surface, which separates the fully saturated zone (![]() $h_g>0$) from the partially saturated zone (

$h_g>0$) from the partially saturated zone (![]() $h_g<0$) (see the later figure 6(a) for a reference image). In essence, the MvG model describes the key hydraulic properties of the soil, hydraulic conductivity and saturation as nonlinear functions of the pressure head

$h_g<0$) (see the later figure 6(a) for a reference image). In essence, the MvG model describes the key hydraulic properties of the soil, hydraulic conductivity and saturation as nonlinear functions of the pressure head ![]() $h_g$. The model introduces further parameters

$h_g$. The model introduces further parameters ![]() $\alpha _{MvG}$,

$\alpha _{MvG}$, ![]() $\theta _r$,

$\theta _r$, ![]() $\theta _s$,

$\theta _s$, ![]() $n$ and

$n$ and ![]() $m=1-{1}/{n}$, which depend on the soil properties. The residual water content

$m=1-{1}/{n}$, which depend on the soil properties. The residual water content ![]() $\theta _r$ and saturated water content

$\theta _r$ and saturated water content ![]() $\theta _s$ represent the lowest and the highest water content, respectively. The

$\theta _s$ represent the lowest and the highest water content, respectively. The ![]() $\alpha _{MvG}$ parameter in

$\alpha _{MvG}$ parameter in ![]() $\mathrm {m}^{-1}$ represents the scaling factor for the pressure head

$\mathrm {m}^{-1}$ represents the scaling factor for the pressure head ![]() $h_g$ (m). The

$h_g$ (m). The ![]() $n$ coefficient describes the pore sizes distribution.

$n$ coefficient describes the pore sizes distribution.

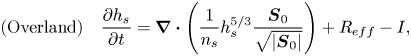

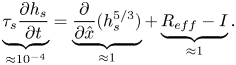

3.2. Two-dimensional Saint Venant equations for the overland flow

If the precipitation exceeds the inflow into the soil, water can accumulate on the surface and form overland flow. Typically, and following e.g. Tayfur & Kavvas (Reference Tayfur and Kavvas1994) and Liu et al. (Reference Liu, Chen, Li and Singh2004) this flow is described using the 2-D Saint Venant equations that govern the overland water height, ![]() $h_s(x, y, t)$. Following the discussion in § 2.2 of Part 1, we consider mass and momentum conservation. Firstly, the continuity equation is given by

$h_s(x, y, t)$. Following the discussion in § 2.2 of Part 1, we consider mass and momentum conservation. Firstly, the continuity equation is given by

where ![]() $I = I(x,y,t)$ is the infiltration rate, and

$I = I(x,y,t)$ is the infiltration rate, and ![]() $R_{eff} = R(x,y,t) - ET(x,y,t)$ is the effective precipitation rate, which we define as the difference between the precipitation rate,

$R_{eff} = R(x,y,t) - ET(x,y,t)$ is the effective precipitation rate, which we define as the difference between the precipitation rate, ![]() $R$, and the evapotranspiration rate,

$R$, and the evapotranspiration rate, ![]() $ET$.

$ET$.

The flux, ![]() $\boldsymbol {q_s}$, that appears in the Saint Venant equation (3.3), is commonly obtained in hydrology using an empirical relationship known as Manning's law. Written in vector form, it is given by

$\boldsymbol {q_s}$, that appears in the Saint Venant equation (3.3), is commonly obtained in hydrology using an empirical relationship known as Manning's law. Written in vector form, it is given by

where ![]() $n_s$ is an empirically determined value known as Manning's coefficient, and describes the overland surface roughness;

$n_s$ is an empirically determined value known as Manning's coefficient, and describes the overland surface roughness; ![]() $\boldsymbol {S_f}$ is a dimensionless friction slope defined as gradient of energy of water per unit weight.

$\boldsymbol {S_f}$ is a dimensionless friction slope defined as gradient of energy of water per unit weight.

When Manning's law in (3.4) is substituted into the continuity equation (3.3), this yields a single equation for the two unknowns, ![]() $h_s$ and

$h_s$ and ![]() $\boldsymbol {S}_f$. In general, the friction slope,

$\boldsymbol {S}_f$. In general, the friction slope, ![]() $\boldsymbol {S_f}$, is given by momentum conservation (cf. (2.7) in Part 1). However, in computational integrated catchment models, a kinematic approximation is often used which neglects all effects on

$\boldsymbol {S_f}$, is given by momentum conservation (cf. (2.7) in Part 1). However, in computational integrated catchment models, a kinematic approximation is often used which neglects all effects on ![]() $\boldsymbol {S}_f$ other than gravity. This approximation is used in e.g. Parflow (Maxwell et al. Reference Maxwell, Kollet, Smith, Woodward, Falgout, Ferguson, Baldwin, Bosl, Hornung and Ashby2009), although there are others such as e.g. MIKE SHE that implement a more complete, diffusive approximation (MIKE SHE 2017). In the case of the kinematic approximation

$\boldsymbol {S}_f$ other than gravity. This approximation is used in e.g. Parflow (Maxwell et al. Reference Maxwell, Kollet, Smith, Woodward, Falgout, Ferguson, Baldwin, Bosl, Hornung and Ashby2009), although there are others such as e.g. MIKE SHE that implement a more complete, diffusive approximation (MIKE SHE 2017). In the case of the kinematic approximation

where ![]() $\boldsymbol {S}_0=-\nabla H_{surf}$ is the elevation gradient. In this paper, we shall adopt the above kinematic approximation. This reduction significantly simplifies the problem since, under this approximation, the overland flows only down the hillslope (the

$\boldsymbol {S}_0=-\nabla H_{surf}$ is the elevation gradient. In this paper, we shall adopt the above kinematic approximation. This reduction significantly simplifies the problem since, under this approximation, the overland flows only down the hillslope (the ![]() $\hat {x}$-direction). As Daluz Vieira (Reference Daluz Vieira1983) argues, this approximation may give inaccurate predictions when the system is close to reaching a steady state.

$\hat {x}$-direction). As Daluz Vieira (Reference Daluz Vieira1983) argues, this approximation may give inaccurate predictions when the system is close to reaching a steady state.

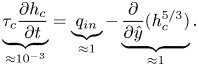

3.3. One-dimensional Saint Venant equation for the channel flow

Finally, we need to formulate the governing equation for the surface flow in a rectangular channel of width ![]() $w$. The channel is directed along the

$w$. The channel is directed along the ![]() $\hat {y}$-axis. Following Daluz Vieira (Reference Daluz Vieira1983) and Chaudhry (Reference Chaudhry2007), the channel flow is modelled as a 1-D Saint Venant equation that governs the channel water height,

$\hat {y}$-axis. Following Daluz Vieira (Reference Daluz Vieira1983) and Chaudhry (Reference Chaudhry2007), the channel flow is modelled as a 1-D Saint Venant equation that governs the channel water height, ![]() $z = h_c(\hat {y}, t)$, and is given by

$z = h_c(\hat {y}, t)$, and is given by

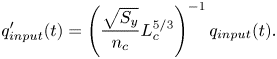

where ![]() $w(h_c, \hat {x})$ is the channel width (constant in the case of a rectangular channel), and

$w(h_c, \hat {x})$ is the channel width (constant in the case of a rectangular channel), and ![]() $q_{in}$ is a source term governing the total surface and subsurface inflow into the river. As for the overland equations, the flux,

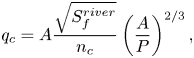

$q_{in}$ is a source term governing the total surface and subsurface inflow into the river. As for the overland equations, the flux, ![]() $q_c$, is assumed to be given by the empirical Manning's law, which takes the form

$q_c$, is assumed to be given by the empirical Manning's law, which takes the form

\begin{equation} q_c = A\frac{\sqrt{S_f^{river}}}{n_c}\left(\frac{A}{P}\right)^{2/3}, \end{equation}

\begin{equation} q_c = A\frac{\sqrt{S_f^{river}}}{n_c}\left(\frac{A}{P}\right)^{2/3}, \end{equation}

where ![]() $A$ is the channel cross-section,

$A$ is the channel cross-section, ![]() $P$ is the channel wetted perimeter,

$P$ is the channel wetted perimeter, ![]() $n_c$ is Manning's coefficient dependent on banks and channel bed roughness and

$n_c$ is Manning's coefficient dependent on banks and channel bed roughness and ![]() $S_f^{river}$ is the friction slope, which under kinematic approximation is equal to the elevation gradient along the river

$S_f^{river}$ is the friction slope, which under kinematic approximation is equal to the elevation gradient along the river

In summary, the solution of the channel flow involves the substitution of Manning's equation (3.7) and the friction slope (3.8) into the Saint Venant equation (3.6). For the case of the V-shaped catchment illustrated in figure 2, where there is a rectangular channel, this involves setting the area ![]() $A = wh_c$ and

$A = wh_c$ and ![]() $P = w + 2 h_c$.

$P = w + 2 h_c$.

The above channel flow model, when coupled to the hillslope forms a challenging numerical computation due to the nonlinearity. Instead, for the purpose of numerical computation, we apply a model simplification of the channel flow similar to what is considered by Maxwell et al. (Reference Maxwell2014). In this simplification, we set ![]() $A=wh_c$ and approximate

$A=wh_c$ and approximate ![]() $P \approx w$, and hence ignore the friction effects of the channel sidewalls. In this case, Manning's equation (3.7) becomes

$P \approx w$, and hence ignore the friction effects of the channel sidewalls. In this case, Manning's equation (3.7) becomes

The later simulations will thus involve the solution of the Saint Venant equation (3.6) with the shallow Manning equation (3.9) and (3.8). The advantage of the above approximation is that the channel flow problem satisfies a similar partial differential equation to the surface flow, but with adjusted coefficient values.

3.4. Boundary conditions

The domain consists of four types of boundaries: (i) the catchment boundary, ![]() $\varGamma _B$, both for the surface and subsurface part of the domain, including the bedrock constraining the aquifer from the bottom; (ii) the land surface

$\varGamma _B$, both for the surface and subsurface part of the domain, including the bedrock constraining the aquifer from the bottom; (ii) the land surface ![]() $\varGamma _s$; (iii) the river bank,

$\varGamma _s$; (iii) the river bank, ![]() $\varGamma _R$; (iv) the river outlet,

$\varGamma _R$; (iv) the river outlet, ![]() $\varGamma _O$; and (v) the river inlet

$\varGamma _O$; and (v) the river inlet ![]() $\varGamma _I$ (see figure 4).

$\varGamma _I$ (see figure 4).

(i) Firstly, there is no surface flow through the catchment boundary. Also, for simplicity, we will assume that there is no groundwater flow through this boundary – the rainwater can only leave the catchment via the channel flow. Hence, on

$\varGamma _B$, we set no-flow conditions for both subsurface and surface flow

(3.10a)Alternatively, one could introduce a free-flow condition for the groundwater flow,

$\varGamma _B$, we set no-flow conditions for both subsurface and surface flow

(3.10a)Alternatively, one could introduce a free-flow condition for the groundwater flow, \begin{equation} \boldsymbol{q_g}\boldsymbol{\cdot}\boldsymbol{n} = 0, \quad \boldsymbol{q_s}\boldsymbol{\cdot}\boldsymbol{n} = 0\quad \text{on $\varGamma_B$}. \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \boldsymbol{q_g}\boldsymbol{\cdot}\boldsymbol{n} = 0, \quad \boldsymbol{q_s}\boldsymbol{\cdot}\boldsymbol{n} = 0\quad \text{on $\varGamma_B$}. \end{equation} $\boldsymbol {q_g}\boldsymbol{\cdot}\boldsymbol {n} = 0$, to allow for the outflow of the groundwater flow through the catchment boundary. In this work, we have chosen no-flow conditions to guarantee that the entirety of the rainfall eventually reaches the channel, which simplifies the resultant water balance.

$\boldsymbol {q_g}\boldsymbol{\cdot}\boldsymbol {n} = 0$, to allow for the outflow of the groundwater flow through the catchment boundary. In this work, we have chosen no-flow conditions to guarantee that the entirety of the rainfall eventually reaches the channel, which simplifies the resultant water balance.(ii) Next, on the land surface,

$\varGamma _s$, continuity of pressure and flow between the groundwater and surface water yields

(3.10b)This first condition imposes continuity of pressure only if the groundwater reaches

$\varGamma _s$, continuity of pressure and flow between the groundwater and surface water yields

(3.10b)This first condition imposes continuity of pressure only if the groundwater reaches \begin{equation} h_s = \begin{cases} 0 & \text{if } h_g<0\\ h_g & \text{if } h_g>0 \end{cases} \quad \text{and} \quad \boldsymbol{q_g}\boldsymbol{\cdot}\boldsymbol{n} = I \quad \text{on $\varGamma_s$}. \end{equation}

\begin{equation} h_s = \begin{cases} 0 & \text{if } h_g<0\\ h_g & \text{if } h_g>0 \end{cases} \quad \text{and} \quad \boldsymbol{q_g}\boldsymbol{\cdot}\boldsymbol{n} = I \quad \text{on $\varGamma_s$}. \end{equation} $\varGamma _s$, while the second imposes the condition of rain infiltration,

$\varGamma _s$, while the second imposes the condition of rain infiltration,  $I$.

$I$.(iii) On the river bank,

$\varGamma _R$, we also impose continuity of pressure between the channel water, which is characterised by a hydrostatic profile,

$\varGamma _R$, we also impose continuity of pressure between the channel water, which is characterised by a hydrostatic profile,  $h(z)=h_c-z$, and the subsurface pressure head,

$h(z)=h_c-z$, and the subsurface pressure head,  $h_g$

(3.10c)

$h_g$

(3.10c) \begin{equation} h_g = h_c - z \quad \text{on $\varGamma_R$}. \end{equation}

\begin{equation} h_g = h_c - z \quad \text{on $\varGamma_R$}. \end{equation}(iv) At the inlet, located at the upstream end of the river,

$\varGamma _I$, we can impose an inflow from the upstream part of the catchment, which is located outside of the modelled domain. In general, it can change over time, and so

(3.10d)In our benchmark scenario, we assume for simplicity that

$\varGamma _I$, we can impose an inflow from the upstream part of the catchment, which is located outside of the modelled domain. In general, it can change over time, and so

(3.10d)In our benchmark scenario, we assume for simplicity that \begin{equation} q_c = q_{input}(t), \quad \text{on $\varGamma_I$}. \end{equation}

\begin{equation} q_c = q_{input}(t), \quad \text{on $\varGamma_I$}. \end{equation} $q_{input}=0$, as if the top boundary represents the start of the stream. Such a stream is referred to as a first-order stream (see Strahler Reference Strahler1957), however, in real-world situations the first-order stream does not reach the catchment divide. The presented model can be also generalised to represent higher-order streams by including a non-zero upstream inflow

$q_{input}=0$, as if the top boundary represents the start of the stream. Such a stream is referred to as a first-order stream (see Strahler Reference Strahler1957), however, in real-world situations the first-order stream does not reach the catchment divide. The presented model can be also generalised to represent higher-order streams by including a non-zero upstream inflow  $q_{input}(t)$.

$q_{input}(t)$.

Note that the kinematic approximation (3.5) that we follow in our work reduces the overland and channel equations to advective equations, rather than advective–diffusion equations. Thus, in this approximation, the downstream boundary conditions – at the river bank ![]() $\varGamma _R$ (for overland flow) and at the catchment outlet

$\varGamma _R$ (for overland flow) and at the catchment outlet ![]() $\varGamma _O$ (for channel flow) – do not have to be imposed.

$\varGamma _O$ (for channel flow) – do not have to be imposed.

This means that, effectively, the channel flow does not impact the overland flow. However, overland flow impacts the channel flow thought the inflow term ![]() $q_{in}$ in (3.6). According to flow continuity, the input to the channel flow is the sum of the overland flow and the total groundwater flow, integrated over the entire channel perimeter at the given cross-section. Thus

$q_{in}$ in (3.6). According to flow continuity, the input to the channel flow is the sum of the overland flow and the total groundwater flow, integrated over the entire channel perimeter at the given cross-section. Thus

Two-way coupling between channel flow and subsurface flow is maintained via boundary condition (3.10c), and two-way coupling between the overland flow and subsurface flow is maintained via (3.10b).

3.5. Initial conditions of the benchmark

The choice of the initial condition is more arbitrary. In contrast to the benchmark scenarios by Maxwell et al. (Reference Maxwell2014), which assumed a constant groundwater depth, we select a more realistic setting, where the groundwater profile is given by its typical shape for a given catchment. Thus, we find a steady state of ![]() $h_g(x,y,z)$,

$h_g(x,y,z)$, ![]() $h_s(x,y)$ and

$h_s(x,y)$ and ![]() $h_c(x,y)$ given by the time-independent versions of the governing equations (3.1), (3.3) and (3.6), solved for a given mean precipitation rate

$h_c(x,y)$ given by the time-independent versions of the governing equations (3.1), (3.3) and (3.6), solved for a given mean precipitation rate ![]() $R_{eff}=R_0$

$R_{eff}=R_0$

Once this initial state is found by solving the above system of equations, we then explore the evolution of ![]() $h_g(x,y,z,t)$ and

$h_g(x,y,z,t)$ and ![]() $h_s(x,y,t)$ caused by intensive rainfall,

$h_s(x,y,t)$ caused by intensive rainfall, ![]() $R_{eff}>R_0$, which moves the system away from the initial state.

$R_{eff}>R_0$, which moves the system away from the initial state.

4. Governing equations (non-dimensional)

4.1. Non-dimensionalisation

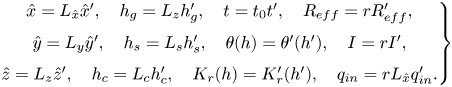

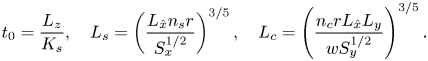

The governing equations for subsurface, surface and channel flow presented in § 2 are now written in tilted coordinates ![]() $(\hat x, \hat y, \hat z)$ (cf. (2.1a–c)) and given in dimensional form in Appendix B.1. In order to understand the relative size of the terms appearing in the governing equations, we non-dimensionalise these equations. The following scalings are used:

$(\hat x, \hat y, \hat z)$ (cf. (2.1a–c)) and given in dimensional form in Appendix B.1. In order to understand the relative size of the terms appearing in the governing equations, we non-dimensionalise these equations. The following scalings are used:

\begin{equation} \left.\begin{array}{c@{}} \hat{x} = L_{\hat x} \hat{x}', \quad h_g = L_z h_g', \quad t = t_0 t', \quad R_{eff} = r R_{eff}', \\ \hat{y} = L_y \hat{y}', \quad h_s = L_s h_s', \quad \theta(h) = \theta'(h'),\quad I = r I',\\ \hat{z} = L_z \hat{z}',\quad h_c = L_c h_c',\quad K_r(h) = K_r'(h'),\quad q_{in} = r L_{\hat x} q_{in}'. \end{array}\right\} \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \left.\begin{array}{c@{}} \hat{x} = L_{\hat x} \hat{x}', \quad h_g = L_z h_g', \quad t = t_0 t', \quad R_{eff} = r R_{eff}', \\ \hat{y} = L_y \hat{y}', \quad h_s = L_s h_s', \quad \theta(h) = \theta'(h'),\quad I = r I',\\ \hat{z} = L_z \hat{z}',\quad h_c = L_c h_c',\quad K_r(h) = K_r'(h'),\quad q_{in} = r L_{\hat x} q_{in}'. \end{array}\right\} \end{equation}

Here, ![]() $r$ is an average value of

$r$ is an average value of ![]() $R_{eff}$. We shall choose the characteristic time,

$R_{eff}$. We shall choose the characteristic time, ![]() $t_0$, overland water height,

$t_0$, overland water height, ![]() $L_s$, and channel water height,

$L_s$, and channel water height, ![]() $L_c$, according to

$L_c$, according to

\begin{equation} t_0 = \frac{L_z}{K_s}, \quad L_s = \left(\frac{L_{\hat x} n_s r}{S_x^{1/2}}\right)^{3/5}, \quad L_c = \left(\frac{n_c r L_{\hat x} L_y}{w S_y^{1/2}}\right)^{3/5}. \end{equation}

\begin{equation} t_0 = \frac{L_z}{K_s}, \quad L_s = \left(\frac{L_{\hat x} n_s r}{S_x^{1/2}}\right)^{3/5}, \quad L_c = \left(\frac{n_c r L_{\hat x} L_y}{w S_y^{1/2}}\right)^{3/5}. \end{equation}The choice of the above quantities comes from balancing the leading terms in the governing equations for subsurface, overland and channel flow, respectively. Their formulation, in terms of tilted coordinates, is presented in (B1), (B2) and (B3) in Appendix B.1.

Additionally, the non-dimensional terms in (4.2a–c) have straightforward physical interpretations. The time scale, ![]() $t_0$, describes a characteristic time that rainwater needs to penetrate the aquifer of thickness

$t_0$, describes a characteristic time that rainwater needs to penetrate the aquifer of thickness ![]() $L_z$, infiltrating with a characteristic speed

$L_z$, infiltrating with a characteristic speed ![]() $K_s$ (such flow occurs due to gravity if there is no hydraulic gradient, e.g. during uniform rainfall). The quantity

$K_s$ (such flow occurs due to gravity if there is no hydraulic gradient, e.g. during uniform rainfall). The quantity ![]() $L_s$ represents the height of the overland flow at the river bank in a steady state with rainfall

$L_s$ represents the height of the overland flow at the river bank in a steady state with rainfall ![]() $r$ (assuming that the entire rainfall forms an overland flow, i.e. no infiltration appears). Similarly,

$r$ (assuming that the entire rainfall forms an overland flow, i.e. no infiltration appears). Similarly, ![]() $L_c$ is an approximate height of the flow in a wide channel at the river outlet in a steady state. Crucially, we note that the choice of the above scaling seems to be correct for our chosen benchmark, with all relevant dimensionless quantities of typical order unity in the numerical simulations of § 6.2.

$L_c$ is an approximate height of the flow in a wide channel at the river outlet in a steady state. Crucially, we note that the choice of the above scaling seems to be correct for our chosen benchmark, with all relevant dimensionless quantities of typical order unity in the numerical simulations of § 6.2.

It should be noted that, even though ![]() $t_0$ is a characteristic time of the vertical flow through the soil, other time scales are present. For example, we shall observe typically shorter time scales for the overland flow, and much longer time scales for the horizontal flow through the soil. Further discussion of the separation of time scales appears in Part 3 of our work.

$t_0$ is a characteristic time of the vertical flow through the soil, other time scales are present. For example, we shall observe typically shorter time scales for the overland flow, and much longer time scales for the horizontal flow through the soil. Further discussion of the separation of time scales appears in Part 3 of our work.

4.2. Summary of governing equations and parameters

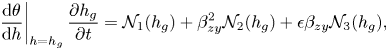

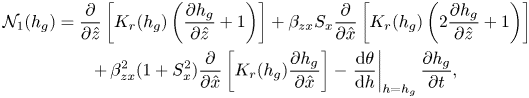

We collect the non-dimensional governing equations from Appendix B.2. To review, our hydrological problems in the 3-D geometry consist of solving three time-dependent partial differential equations for three unknowns: (i) a 3-D Richards equation for the subsurface flow (4.3a); (ii) a 2-D Saint Venant equation for the overland flow (4.3b); and (iii) a 1-D Saint Venant equation for the channel flow (4.3c). In the tilted frame, these are, respectively,

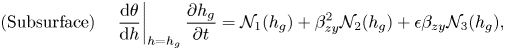

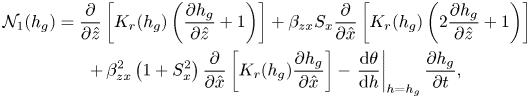

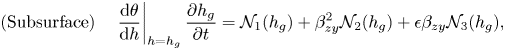

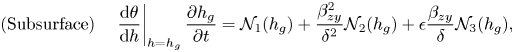

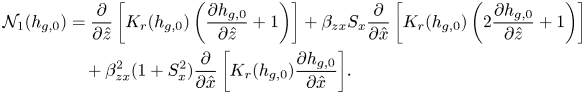

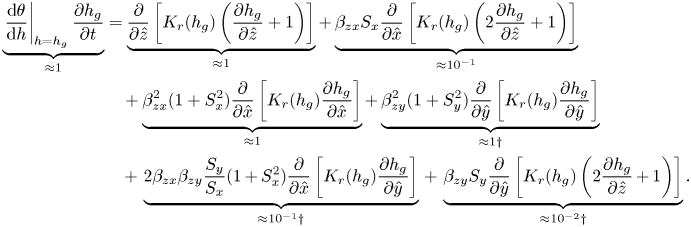

$$\begin{gather} \text{(Subsurface)} \quad \left.\frac{\mathrm{d}\theta}{\mathrm{d} h}\right\vert_{h=h_g}\frac{\partial h_g}{\partial t} = \mathcal{N}_1(h_g) + \beta_{zy}^2 \mathcal{N}_2(h_g) + \epsilon \beta_{zy} \mathcal{N}_3(h_g), \end{gather}$$

$$\begin{gather} \text{(Subsurface)} \quad \left.\frac{\mathrm{d}\theta}{\mathrm{d} h}\right\vert_{h=h_g}\frac{\partial h_g}{\partial t} = \mathcal{N}_1(h_g) + \beta_{zy}^2 \mathcal{N}_2(h_g) + \epsilon \beta_{zy} \mathcal{N}_3(h_g), \end{gather}$$where the subsurface equations involve operator definitions

\begin{gather} \mathcal{N}_1(h_g) = \frac{\partial }{\partial \hat{z}} \left[K_r(h_g) \left(\frac{\partial h_g}{\partial \hat{z}}+1\right)\right] + \beta_{zx} S_x\frac{\partial }{\partial \hat{x}} \left[K_r(h_g) \left(2\frac{\partial h_g}{\partial \hat{z}}+1\right)\right] \nonumber\\ \quad + \,\beta_{zx}^2 \left(1 + S_x^2\right)\frac{\partial }{\partial \hat{x}} \left[K_r(h_g) \frac{\partial h_g}{\partial \hat{x}}\right] - \left.\frac{\mathrm{d}\theta}{\mathrm{d} h}\right\vert_{h=h_g}\frac{\partial h_g}{\partial t}, \end{gather}

\begin{gather} \mathcal{N}_1(h_g) = \frac{\partial }{\partial \hat{z}} \left[K_r(h_g) \left(\frac{\partial h_g}{\partial \hat{z}}+1\right)\right] + \beta_{zx} S_x\frac{\partial }{\partial \hat{x}} \left[K_r(h_g) \left(2\frac{\partial h_g}{\partial \hat{z}}+1\right)\right] \nonumber\\ \quad + \,\beta_{zx}^2 \left(1 + S_x^2\right)\frac{\partial }{\partial \hat{x}} \left[K_r(h_g) \frac{\partial h_g}{\partial \hat{x}}\right] - \left.\frac{\mathrm{d}\theta}{\mathrm{d} h}\right\vert_{h=h_g}\frac{\partial h_g}{\partial t}, \end{gather}

Expressions for ![]() $\theta (h_g)$ and

$\theta (h_g)$ and ![]() $K_r(h_g)$ are provided in Appendix B.2. Each partial differential equation in (4.3) is solved subject to boundary conditions posed on the domain boundaries given by (B8a)–(B8d).

$K_r(h_g)$ are provided in Appendix B.2. Each partial differential equation in (4.3) is solved subject to boundary conditions posed on the domain boundaries given by (B8a)–(B8d).

Finally, these equations are characterised by nine independent dimensionless parameters, {![]() $\beta _{zx}$,

$\beta _{zx}$, ![]() $\beta _{zy}$,

$\beta _{zy}$, ![]() $\sigma _x$,

$\sigma _x$, ![]() $\sigma _y$,

$\sigma _y$, ![]() $\tau _s$,

$\tau _s$, ![]() $\tau _c$,

$\tau _c$, ![]() $\gamma$,

$\gamma$, ![]() $\alpha$,

$\alpha$, ![]() $\rho$}, with definitions provided in Appendix C.

$\rho$}, with definitions provided in Appendix C.

5. Model reduction to a two-dimensional model

In § 2, we formulated a general 3-D catchment model. The purpose of this section is to discuss the non-dimensionalisation of the model, which subsequently allows for the determination of the key dimensionless parameters governing the system. Once these are known, we may use the typical dimensional values established in Part 1 in order to compare the relative strengths of the various physical effects of the system.

We highlight two approximations:

(i) Considering either small river slope (

$S_y\ll S_x$), short (

$S_y\ll S_x$), short ( $L_y\ll L_z$), or long catchment (

$L_y\ll L_z$), or long catchment ( $L_y\gg L_z$) approximations together with the necessary low channel limit (

$L_y\gg L_z$) approximations together with the necessary low channel limit ( $L_c\ll L_z$), we may reduce the general 3-D governing equations for

$L_c\ll L_z$), we may reduce the general 3-D governing equations for  $h_g$ and

$h_g$ and  $h_s$ to a 2-D form neglecting the flow along the

$h_s$ to a 2-D form neglecting the flow along the  $y$-axis.

$y$-axis.(ii) In addition, in the case of the shallow aquifer scenario (

$L_z\ll L_x$), we may apply a shallow-water approximation to further reduce the 2-D hillslope model to a 1-D model.

$L_z\ll L_x$), we may apply a shallow-water approximation to further reduce the 2-D hillslope model to a 1-D model.

In this section, the approximations given in (i) are discussed. The regime of (ii) and its consequences are explored in Part 3 of our work.

5.1. Discussion of the low channel height limit,  $L_c\ll L_z$

$L_c\ll L_z$

The 3-D model in ![]() $(x,y,z)$ can be formally approximated by a 2-D model in

$(x,y,z)$ can be formally approximated by a 2-D model in ![]() $(x,z)$ if the subsurface profile,

$(x,z)$ if the subsurface profile, ![]() $h_g(x,y,z,t) \sim h_{g,0}(x,z,t)$, and the surface profile,

$h_g(x,y,z,t) \sim h_{g,0}(x,z,t)$, and the surface profile, ![]() $h_s(x,y,t) \sim h_{s,0}(x,t)$, and both asymptotic approximations are consistent with the initial and boundary conditions (at the leading order).

$h_s(x,y,t) \sim h_{s,0}(x,t)$, and both asymptotic approximations are consistent with the initial and boundary conditions (at the leading order).

We observe that the boundary condition (3.10c), along the channel, ![]() $\varGamma _R$, depends in general on the channel water height,

$\varGamma _R$, depends in general on the channel water height, ![]() $h_c(y,t)$, which can vary along the catchment. For example, the dimensional height can vary from

$h_c(y,t)$, which can vary along the catchment. For example, the dimensional height can vary from ![]() $h_c=0$ at

$h_c=0$ at ![]() $y=L_y$ (if there is no inflow to the river from the upstream point) to a dimensional height

$y=L_y$ (if there is no inflow to the river from the upstream point) to a dimensional height ![]() $h_c=L_c$ at

$h_c=L_c$ at ![]() $y = 0$ (in the case of the steady-state outflow). Returning to non-dimensional values for

$y = 0$ (in the case of the steady-state outflow). Returning to non-dimensional values for ![]() $h_g$,

$h_g$, ![]() $h_c$ and

$h_c$ and ![]() $z$, (3.10c) yields

$z$, (3.10c) yields

Typically, the values of ![]() $L_c/L_z$ are very small: based on the UK catchment data from Part 1, we can extract the interquartile range for

$L_c/L_z$ are very small: based on the UK catchment data from Part 1, we can extract the interquartile range for ![]() $L_c/L_z$, namely

$L_c/L_z$, namely ![]() $[0.0011, 0.0147]$ (i.e. the middle half of UK catchments have

$[0.0011, 0.0147]$ (i.e. the middle half of UK catchments have ![]() $L_c/L_z$ within this interval). Thus, even though the channel water height may vary along the channel, it is negligibly small comparing with the typical variation of the pressure head. In the limit of

$L_c/L_z$ within this interval). Thus, even though the channel water height may vary along the channel, it is negligibly small comparing with the typical variation of the pressure head. In the limit of ![]() $L_c/L_z \to 0$, we see that the subsurface boundary condition is

$L_c/L_z \to 0$, we see that the subsurface boundary condition is

which is no longer ![]() $y$-dependent.

$y$-dependent.

5.2. An asymptotic expansion for small river slopes, in  $\epsilon = S_y/S_x$

$\epsilon = S_y/S_x$

Although the remaining boundary conditions ((3.10a)–(3.10d) without (3.10c)) are not explicitly ![]() $y$-dependent, the solution

$y$-dependent, the solution ![]() $h(x,z,t)$ may still exhibit leading

$h(x,z,t)$ may still exhibit leading ![]() $y$-dependent effects due to e.g. the topography. However, there are certain approximations in which these effects are very small – for example, when the slope along the channel

$y$-dependent effects due to e.g. the topography. However, there are certain approximations in which these effects are very small – for example, when the slope along the channel ![]() $S_y$ is much lower than the slope along the hillslope

$S_y$ is much lower than the slope along the hillslope ![]() $S_x$. Note that the aspect ratio introduced in § 2.1,

$S_x$. Note that the aspect ratio introduced in § 2.1, ![]() $\epsilon = S_y/S_x$, typically has small values (half of UK catchments have

$\epsilon = S_y/S_x$, typically has small values (half of UK catchments have ![]() $\epsilon$ between

$\epsilon$ between ![]() $0.13$ and

$0.13$ and ![]() $0.25$). Here, we shall demonstrate that when

$0.25$). Here, we shall demonstrate that when ![]() $\epsilon \ll 1$ (equivalent to

$\epsilon \ll 1$ (equivalent to ![]() $S_y\ll S_x$), the solution is expected to be predominantly two-dimensional.

$S_y\ll S_x$), the solution is expected to be predominantly two-dimensional.

Firstly, we rewrite the set of dimensionless governing equations for the subsurface and overland flows, (B4) and (B5), in a simpler form highlighting its structure

$$\begin{gather} \text{(Subsurface)} \quad \left.\frac{\mathrm{d}\theta}{\mathrm{d} h}\right\vert_{h=h_g}\frac{\partial h_g}{\partial t} = \mathcal{N}_1(h_g) + \beta_{zy}^2 \mathcal{N}_2(h_g) + \epsilon \beta_{zy} \mathcal{N}_3(h_g), \end{gather}$$

$$\begin{gather} \text{(Subsurface)} \quad \left.\frac{\mathrm{d}\theta}{\mathrm{d} h}\right\vert_{h=h_g}\frac{\partial h_g}{\partial t} = \mathcal{N}_1(h_g) + \beta_{zy}^2 \mathcal{N}_2(h_g) + \epsilon \beta_{zy} \mathcal{N}_3(h_g), \end{gather}$$

where the nonlinear operators, ![]() $\mathcal {N}_i$, for

$\mathcal {N}_i$, for ![]() $i = 1, 2, 3$ are defined in (B13) in Appendix B.2. Note that these operators are dependent on

$i = 1, 2, 3$ are defined in (B13) in Appendix B.2. Note that these operators are dependent on ![]() $h_g$ and

$h_g$ and ![]() $h_s$, and independent of

$h_s$, and independent of ![]() $\epsilon$ and

$\epsilon$ and ![]() $\beta _{zy}$, which are the only dimensionless parameters involving

$\beta _{zy}$, which are the only dimensionless parameters involving ![]() $S_y$ and

$S_y$ and ![]() $L_y$.

$L_y$.

When ![]() $\epsilon = 0$, we can verify that the solutions are independent of

$\epsilon = 0$, we can verify that the solutions are independent of ![]() $\hat {y}$, i.e. they can be written as

$\hat {y}$, i.e. they can be written as ![]() $h_g(\hat x,\hat y,\hat z)=h_{g,0}(\hat x,\hat z)$ and

$h_g(\hat x,\hat y,\hat z)=h_{g,0}(\hat x,\hat z)$ and ![]() $h_s(\hat x,\hat y)=h_{s,0}(\hat x)$. This is caused by the combination of three facts:

$h_s(\hat x,\hat y)=h_{s,0}(\hat x)$. This is caused by the combination of three facts:

(i) term

$\mathcal {N}_1(h_g)$ is independent of

$\mathcal {N}_1(h_g)$ is independent of  $\hat {y}$;

$\hat {y}$;(ii) operators

$\mathcal {N}_2$ and

$\mathcal {N}_2$ and  $\mathcal {N}_3$ applied to a function independent of

$\mathcal {N}_3$ applied to a function independent of  $\hat {y}$ become

$\hat {y}$ become  $0$; and

$0$; and(iii) the no-flux boundary condition at

$\hat {y}=0, \, 1$ in (B8a) is then

(5.4)Hence, for

$\hat {y}=0, \, 1$ in (B8a) is then

(5.4)Hence, for \begin{equation} \frac{\partial h_g}{\partial \hat{y}}-\frac{\epsilon}{1-\epsilon^2} \left(\frac{\beta_{zx}}{\beta_{zy}}\frac{\partial h_g}{\partial \hat{x}}-\epsilon\frac{\partial h_g}{\partial \hat{y}} -\frac{2S_x}{\beta_{zy}}\frac{\partial h_g}{\partial \hat{z}}\right)= 0. \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \frac{\partial h_g}{\partial \hat{y}}-\frac{\epsilon}{1-\epsilon^2} \left(\frac{\beta_{zx}}{\beta_{zy}}\frac{\partial h_g}{\partial \hat{x}}-\epsilon\frac{\partial h_g}{\partial \hat{y}} -\frac{2S_x}{\beta_{zy}}\frac{\partial h_g}{\partial \hat{z}}\right)= 0. \end{equation} $\epsilon =0$, the above boundary condition is satisfied by

$\epsilon =0$, the above boundary condition is satisfied by  $h_g=h_{g,0}(\hat x,\hat z)$.

$h_g=h_{g,0}(\hat x,\hat z)$.(iv) From (5.3b) only

$R_{eff}$ and

$R_{eff}$ and  $I$ can be

$I$ can be  $\hat {y}$-dependent terms, but in the considered scenario

$\hat {y}$-dependent terms, but in the considered scenario  $R_{eff}$ is constant, and

$R_{eff}$ is constant, and  $I(\hat {x},\hat {y})$ is

$I(\hat {x},\hat {y})$ is  $\hat {y}$ independent as long as

$\hat {y}$ independent as long as  $h_g$ is.

$h_g$ is.

Essentially, ![]() $\epsilon =0$ is associated with a zero gradient along the river, i.e. there is no forcing flow in the

$\epsilon =0$ is associated with a zero gradient along the river, i.e. there is no forcing flow in the ![]() $\hat {y}$-direction, and the domain becomes transitionally symmetric in that direction.

$\hat {y}$-direction, and the domain becomes transitionally symmetric in that direction.

There is an important consideration in the formal limit as ![]() $S_y\propto \epsilon \to 0$. In this limit, holding other parameters fixed, the

$S_y\propto \epsilon \to 0$. In this limit, holding other parameters fixed, the ![]() $L_c$ defined in (4.2a–c) tends to

$L_c$ defined in (4.2a–c) tends to ![]() $\infty$, and so the

$\infty$, and so the ![]() $L_c\ll L_z$ condition from (5.1) is no longer satisfied. This is due to the fact that when reducing the gradient along the channel,

$L_c\ll L_z$ condition from (5.1) is no longer satisfied. This is due to the fact that when reducing the gradient along the channel, ![]() $S_y$, the channel water height must increase in order to maintain a significant channel flow (cf. Manning's law (3.9)). Therefore, we would expect for a 2-D dynamics to dominate when

$S_y$, the channel water height must increase in order to maintain a significant channel flow (cf. Manning's law (3.9)). Therefore, we would expect for a 2-D dynamics to dominate when

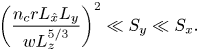

\begin{equation} \left(\frac{n_c r L_{\hat x} L_y}{w L_z^{5/3}}\right)^2\ll S_y\ll S_x. \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \left(\frac{n_c r L_{\hat x} L_y}{w L_z^{5/3}}\right)^2\ll S_y\ll S_x. \end{equation}

Above, the expression on the left-hand side is obtained from the definition of ![]() $L_y$ from (4.2a–c), and represents the value of

$L_y$ from (4.2a–c), and represents the value of ![]() $S_y$, for which

$S_y$, for which ![]() $L_c=L_z$. In real-world situations,

$L_c=L_z$. In real-world situations, ![]() $S_y$ (with a median value of

$S_y$ (with a median value of ![]() $0.014$ based on the data collected in Part 1) is higher by a few orders of magnitude over this threshold (with a median value of

$0.014$ based on the data collected in Part 1) is higher by a few orders of magnitude over this threshold (with a median value of ![]() $6.1\times 10^{-11}$), and so only the second approximation in (5.5) needs to be considered.

$6.1\times 10^{-11}$), and so only the second approximation in (5.5) needs to be considered.

5.3. Asymptotic expansions for short ( $\beta _{zy} \gg 1$) and long (

$\beta _{zy} \gg 1$) and long ( $\beta _{zy} \ll 1$) catchments

$\beta _{zy} \ll 1$) catchments

There are additional limits that allow us to reduce the 3-D problem into simpler 2-D formulations at the leading order, and these involve the non-dimensional geometrical parameter

For instance, in the limit as ![]() $\beta _{zy} \to \infty$, the 3-D catchment reduces to an infinitely thin hillslope profile with a negligible flow in the perpendicular direction to the hillslope (since we imposed no-flow conditions at

$\beta _{zy} \to \infty$, the 3-D catchment reduces to an infinitely thin hillslope profile with a negligible flow in the perpendicular direction to the hillslope (since we imposed no-flow conditions at ![]() $\hat {y}=0$ and

$\hat {y}=0$ and ![]() $\hat {y}=1$). Equivalently, this corresponds to an asymptotically short section of a river. From (5.4), we see that the leading-order profile should satisfy the

$\hat {y}=1$). Equivalently, this corresponds to an asymptotically short section of a river. From (5.4), we see that the leading-order profile should satisfy the ![]() $\operatorname {d\!}{}{h_{g,0}}/\operatorname {d\!}{}{\hat {y}}=0$ condition at

$\operatorname {d\!}{}{h_{g,0}}/\operatorname {d\!}{}{\hat {y}}=0$ condition at ![]() $\hat {y} = 0, 1$, which is automatically satisfied for a

$\hat {y} = 0, 1$, which is automatically satisfied for a ![]() $\hat {y}$-independent solution. As argued in the previous section, we also conclude that such a

$\hat {y}$-independent solution. As argued in the previous section, we also conclude that such a ![]() $\hat {y}$-independent solution will also satisfy the governing equations (5.3).

$\hat {y}$-independent solution will also satisfy the governing equations (5.3).

Using a similar analysis to the one presented in the previous section, by balancing leading terms in the boundary conditions (5.4), we can show that the full three-dimensional solution can be expanded in terms of ![]() $\beta _{zy}^{-1}$

$\beta _{zy}^{-1}$

The last interesting limit we discuss is ![]() $\beta _{zy}\rightarrow 0$, which corresponds to the situation of an asymptotically long river. Similarly, the 2-D solution satisfies the governing equations (5.3). However, this time, it does not satisfy the no-flow boundary condition (5.4). Therefore, we expect to observe a boundary layer around

$\beta _{zy}\rightarrow 0$, which corresponds to the situation of an asymptotically long river. Similarly, the 2-D solution satisfies the governing equations (5.3). However, this time, it does not satisfy the no-flow boundary condition (5.4). Therefore, we expect to observe a boundary layer around ![]() $\hat {y}=0$ and

$\hat {y}=0$ and ![]() $\hat {y}=1$ (see figure 5). Consequently,

$\hat {y}=1$ (see figure 5). Consequently, ![]() $h_{g,0}$ and

$h_{g,0}$ and ![]() $h_{s,0}$ are understood to represent the ‘outer’ asymptotic solutions, valid for

$h_{s,0}$ are understood to represent the ‘outer’ asymptotic solutions, valid for ![]() $0 < \hat {y} < 1$.

$0 < \hat {y} < 1$.

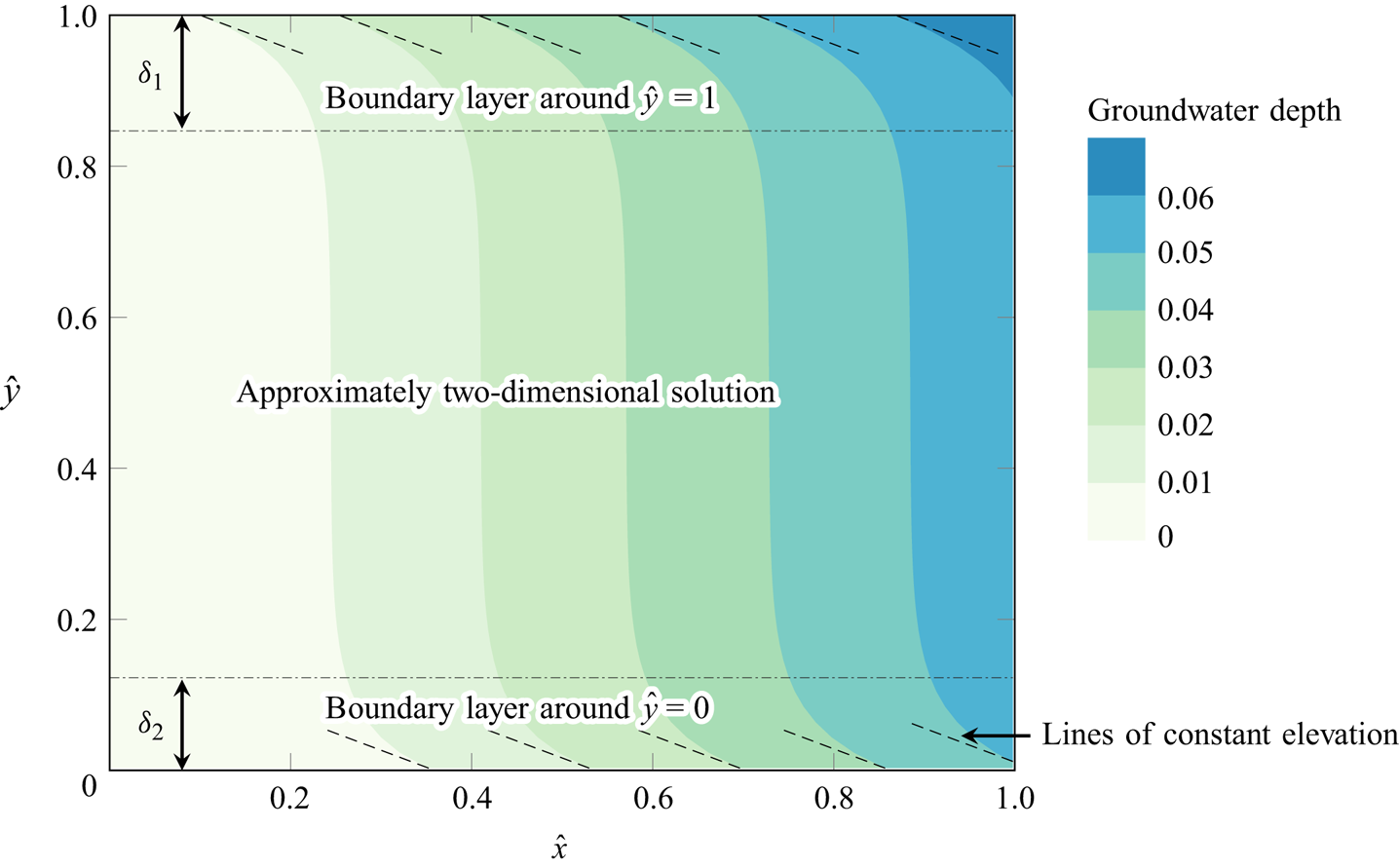

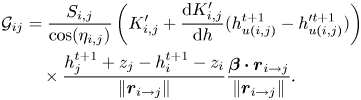

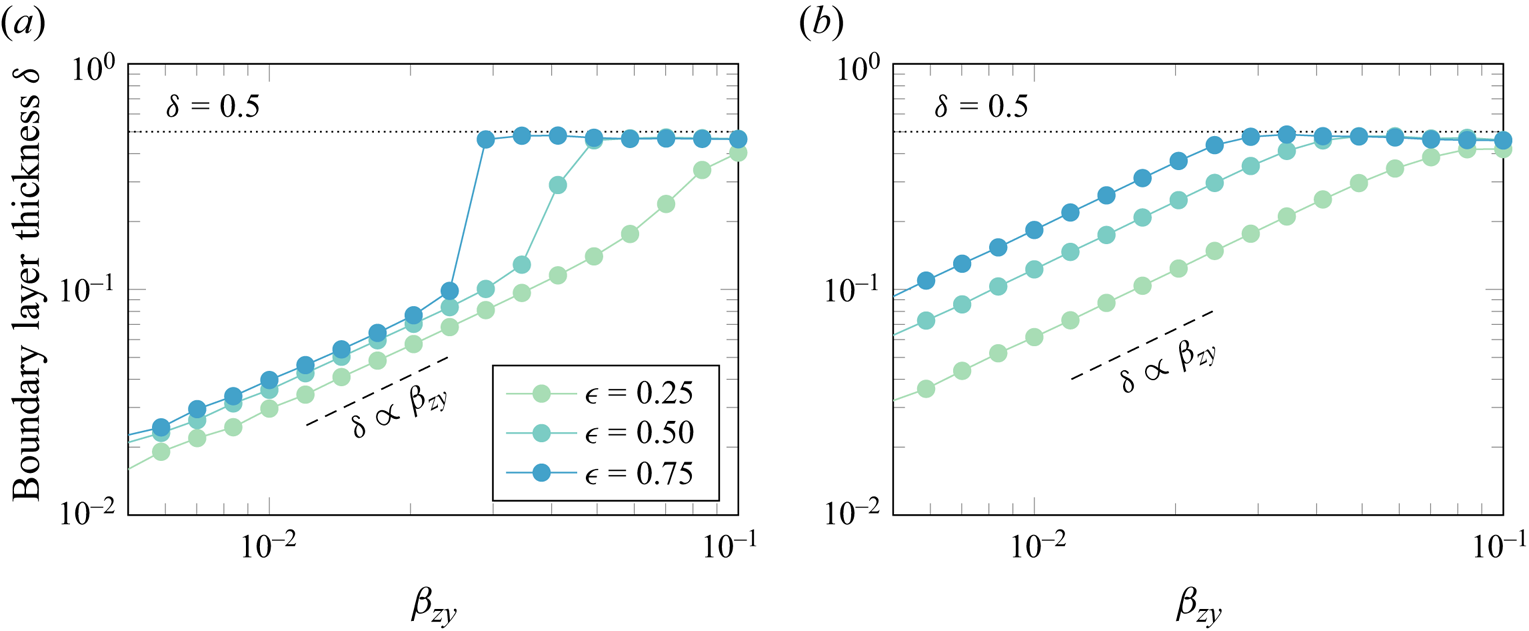

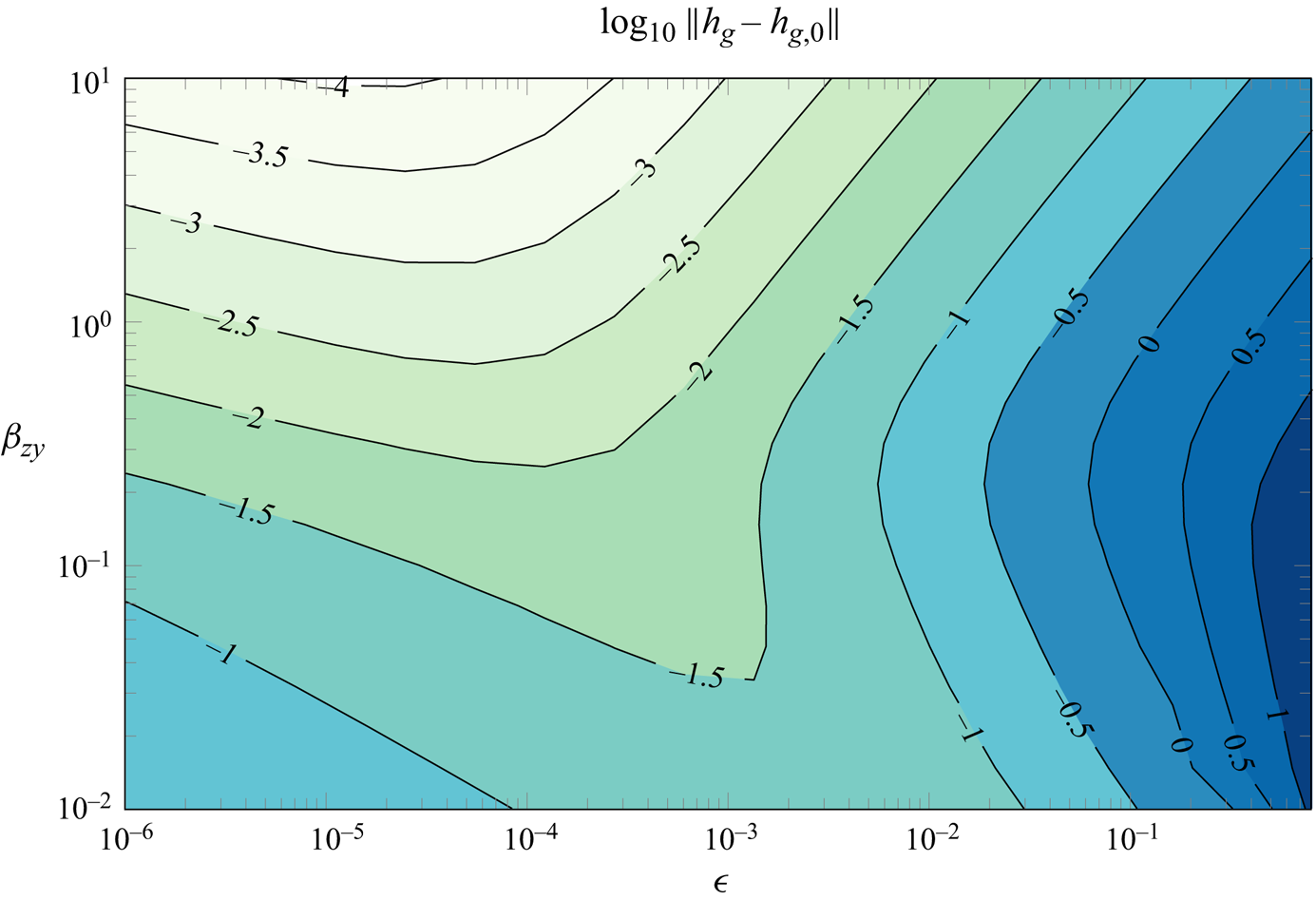

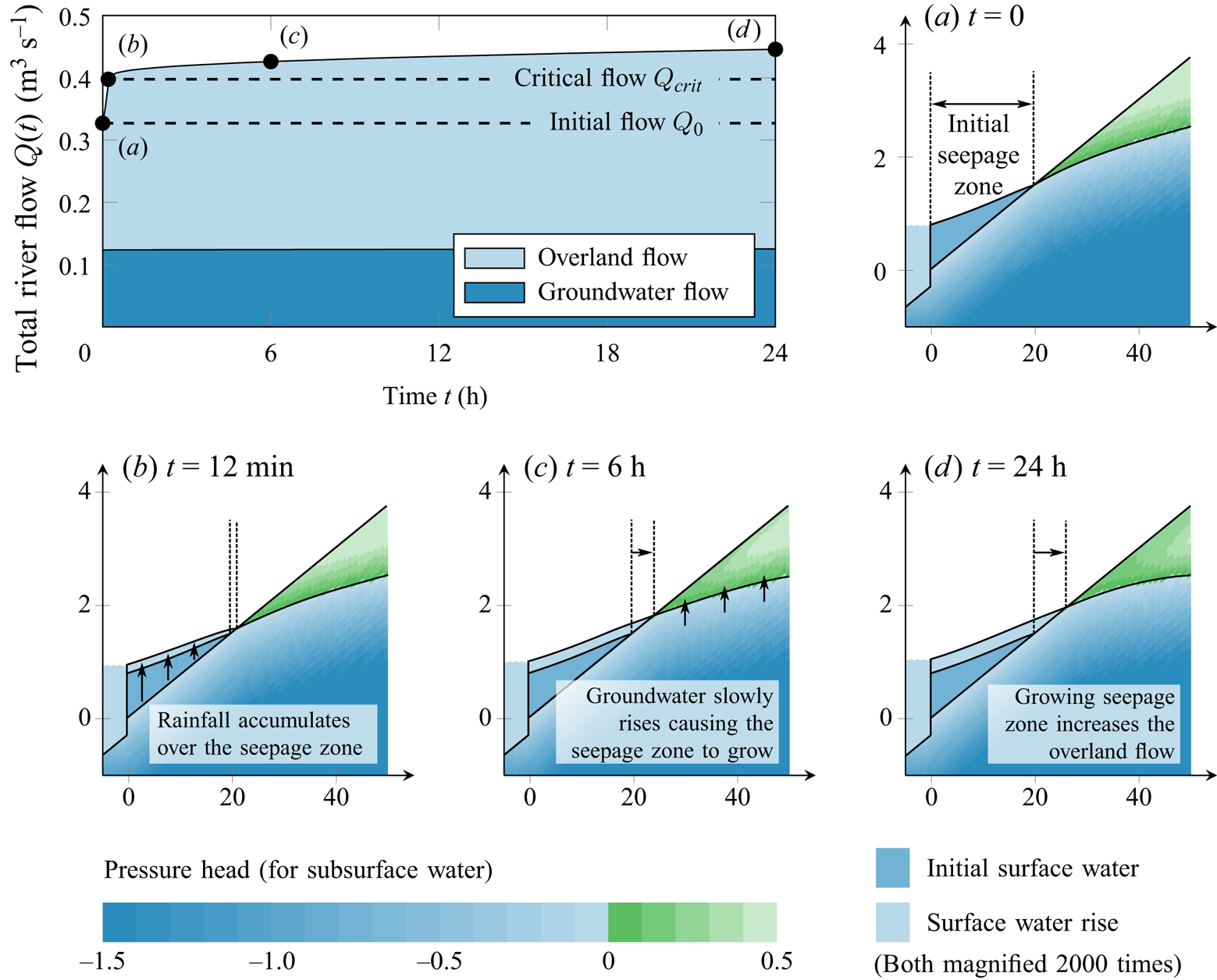

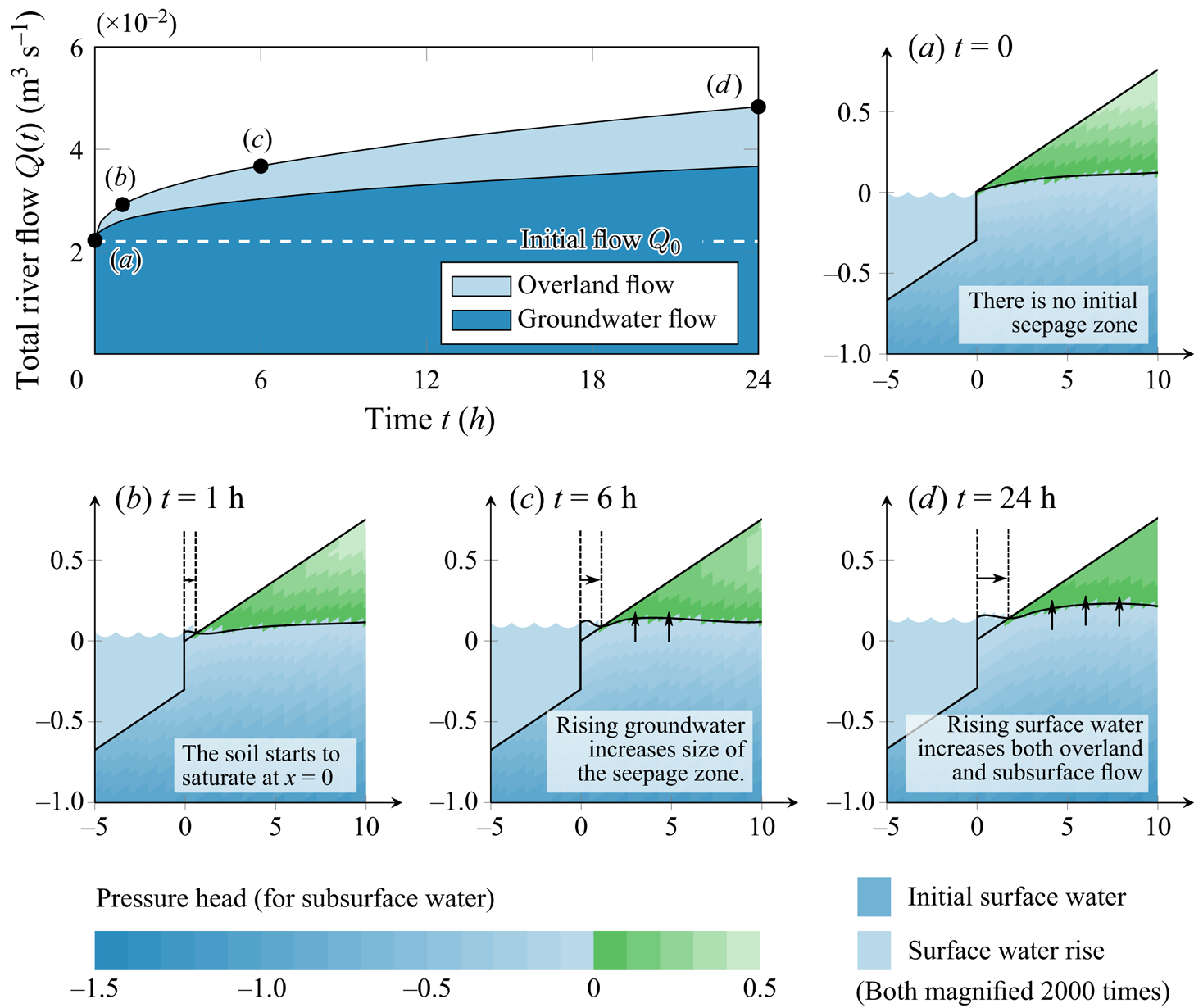

Figure 5. This graphic shows the steady-state depth of the groundwater table, according to the 3-D model. We note that the solution is mostly ![]() $\hat {y}$-independent, except for two apparent boundary layers around

$\hat {y}$-independent, except for two apparent boundary layers around ![]() $\hat {y}=0$ and

$\hat {y}=0$ and ![]() $\hat {y}=1$; near these points, the groundwater table aligns with the lines of constant elevation. The figure is generated using the solver described in § 6 using the parameter values given in table 1, except for two values: we use

$\hat {y}=1$; near these points, the groundwater table aligns with the lines of constant elevation. The figure is generated using the solver described in § 6 using the parameter values given in table 1, except for two values: we use ![]() $L_y=13680$ m (

$L_y=13680$ m (![]() $\beta _{zy}=0.05$) and

$\beta _{zy}=0.05$) and ![]() $S_y=0.0075$ (

$S_y=0.0075$ (![]() $\epsilon =0.1$); as a result, this graphic matches an inset in figure 9. The boundary layer thicknesses,

$\epsilon =0.1$); as a result, this graphic matches an inset in figure 9. The boundary layer thicknesses, ![]() $\delta _1$ and

$\delta _1$ and ![]() $\delta _2$, tend to zero as

$\delta _2$, tend to zero as ![]() $\beta _{zy} \to \infty$.

$\beta _{zy} \to \infty$.

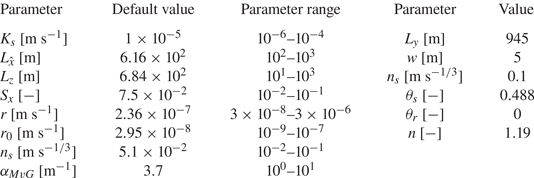

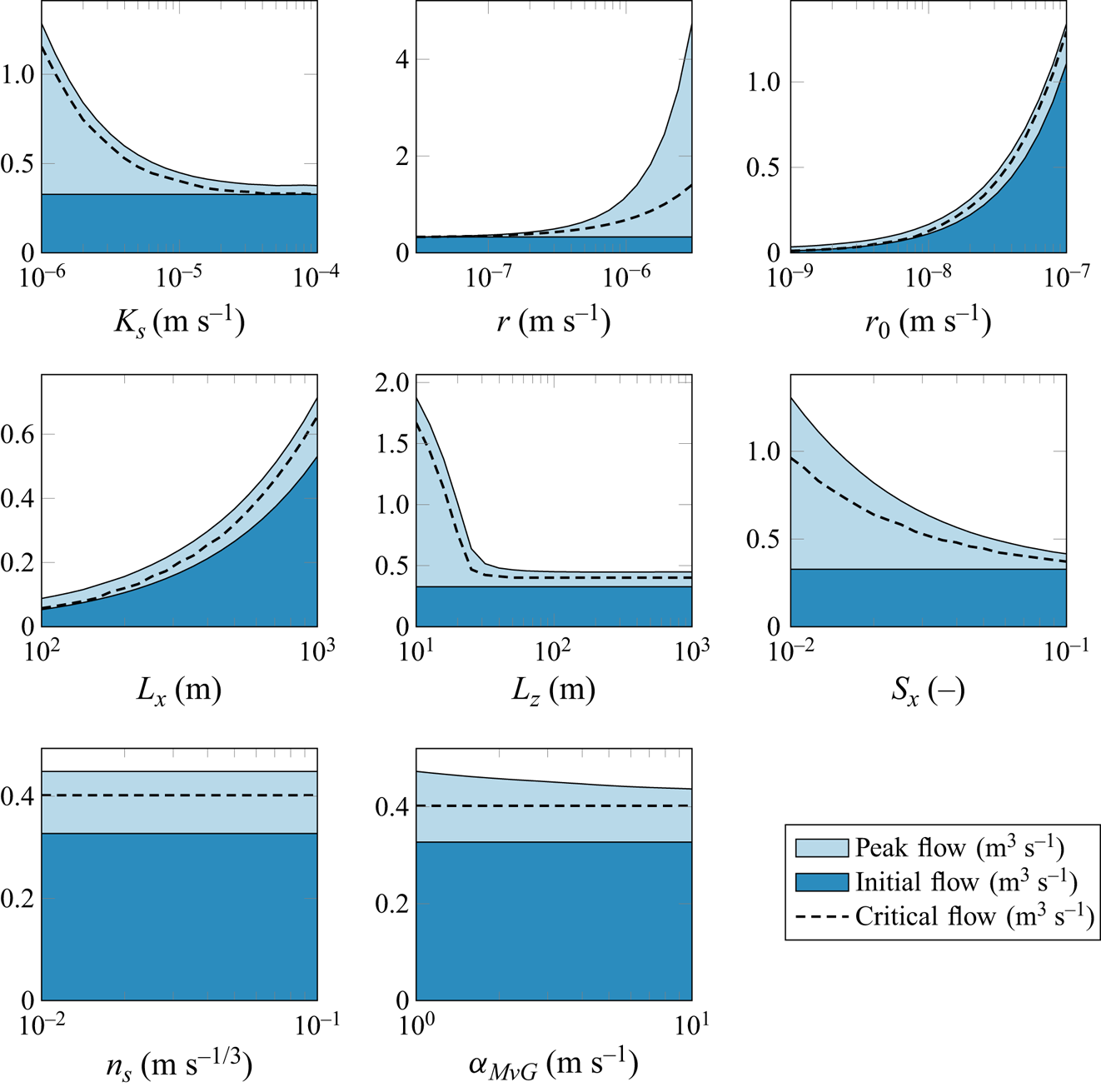

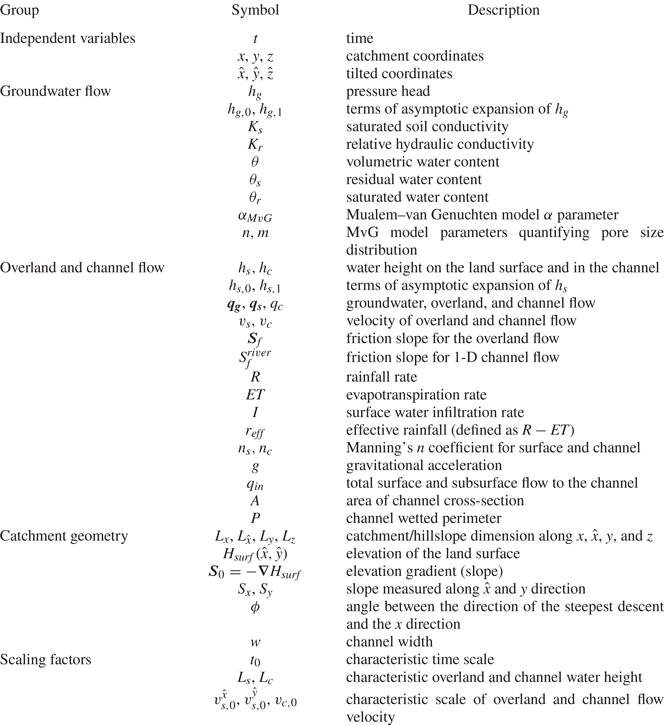

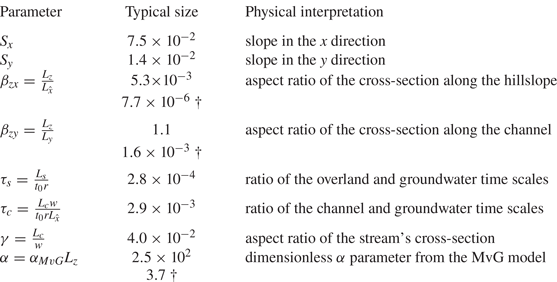

Table 1. Columns on right present the default values and ranges of the parameters used to perform a sensitivity analysis. Columns on the left present parameters which were not varied during the sensitivity analysis. The length of the catchment was selected to be ![]() $L_y^{trib}$ estimated from Part 1, which represents the typical distance between the main tributaries of the river.

$L_y^{trib}$ estimated from Part 1, which represents the typical distance between the main tributaries of the river.

Without loss of generality, let us consider the boundary layer near ![]() $\hat {y} = 0$. We rescale

$\hat {y} = 0$. We rescale ![]() $\hat {y}=\delta \hat {y}'$ where

$\hat {y}=\delta \hat {y}'$ where ![]() $\delta (\beta _{zy})$ is a characteristic size of the boundary layer. After applying this transformation, the governing equations (5.3) become

$\delta (\beta _{zy})$ is a characteristic size of the boundary layer. After applying this transformation, the governing equations (5.3) become

$$\begin{gather} \text{(Subsurface)} \quad \left.\frac{\mathrm{d}\theta}{\mathrm{d} h}\right\vert_{h=h_g}\frac{\partial h_g}{\partial t} = \mathcal{N}_1(h_g) + \frac{\beta_{zy}^2}{\delta^2} \mathcal{N}_2(h_g) + \epsilon \frac{\beta_{zy}}{\delta} \mathcal{N}_3(h_g), \end{gather}$$

$$\begin{gather} \text{(Subsurface)} \quad \left.\frac{\mathrm{d}\theta}{\mathrm{d} h}\right\vert_{h=h_g}\frac{\partial h_g}{\partial t} = \mathcal{N}_1(h_g) + \frac{\beta_{zy}^2}{\delta^2} \mathcal{N}_2(h_g) + \epsilon \frac{\beta_{zy}}{\delta} \mathcal{N}_3(h_g), \end{gather}$$ The 3-D effects given by ![]() $\mathcal {N}_2$ and

$\mathcal {N}_2$ and ![]() $\mathcal {N}_3$ become significant when the characteristic size of the boundary layer is of the order

$\mathcal {N}_3$ become significant when the characteristic size of the boundary layer is of the order ![]() $O(\beta _{zy})$. Hence, we conclude that the thickness of the boundary layer is

$O(\beta _{zy})$. Hence, we conclude that the thickness of the boundary layer is ![]() $O(1/\beta _{zy})$. Therefore, if we consider the

$O(1/\beta _{zy})$. Therefore, if we consider the ![]() ${\beta _{zy}\rightarrow 0}$ limit, the solution for the problem becomes two-dimensional except for an infinitely thin boundary layer around the boundaries.

${\beta _{zy}\rightarrow 0}$ limit, the solution for the problem becomes two-dimensional except for an infinitely thin boundary layer around the boundaries.

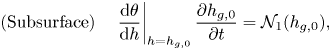

5.4. Summary of the two-dimensional model

To summarise, we considered three approximations for small river slope (![]() $\epsilon \ll 1$), short catchments (

$\epsilon \ll 1$), short catchments (![]() $\beta _{zy}\gg 1$), and long catchments (

$\beta _{zy}\gg 1$), and long catchments (![]() $\beta _{zy}\ll 1$). We showed that, under any of these approximations, the model can be approximately represented in the following 2-D form:

$\beta _{zy}\ll 1$). We showed that, under any of these approximations, the model can be approximately represented in the following 2-D form:

$$\begin{gather} \text{(Subsurface)} \quad \left.\frac{\mathrm{d}\theta}{\mathrm{d} h}\right\vert_{h=h_{g,0}}\frac{\partial h_{g,0}}{\partial t} = \mathcal{N}_1(h_{g,0}), \end{gather}$$

$$\begin{gather} \text{(Subsurface)} \quad \left.\frac{\mathrm{d}\theta}{\mathrm{d} h}\right\vert_{h=h_{g,0}}\frac{\partial h_{g,0}}{\partial t} = \mathcal{N}_1(h_{g,0}), \end{gather}$$with