1. INTRODUCTION

Andorra is an independent microstate in the Pyrenees and is the only country in the world where one of two joint heads of state is directly elected by the citizens of a foreign country – France. The French President always concurrently holds the office of Co-Prince of Andorra alongside the Catholic Bishop of Urgell. A quirk of history has thus resulted in the leaders of one of the most famous bastions of European democratic secularism, France, sharing an unelected role with a religious official. This article will examine the influence of France, and specifically the French language, in this tiny country, nestled high in the Pyrenees on the border of France and Spain.

Andorra today is multilingual. Although Catalan is the sole official language enshrined in law, French is widely used in education, and Spanish fulfils the role of lingua franca between different migrant groups in the country. Andorra has seen extensive migration since the middle of the twentieth century. Its current population of 77,543 (Govern d’Andorra Reference d’Andorra2020: 5) has grown steadily from 6,186 in 1950 (Lluelles Reference Lluelles and Lluelles2004: 145) due to labour migration, chiefly from Spain and Portugal. In his role as Co-Prince, Emmanuel Macron delivered a 2019 address to the Formal Session of the General Council of Andorra in which he revealed an awareness of the potentially diminishing economic, cultural and linguistic importance of France in the face of the shifting demographics of the country:

Je crois qu’il existe actuellement un risque à ce que l’esprit d’équilibre qui a toujours prévalu dans la société andorrane, en particulier dans ses relations avec l’Espagne et la France, s’affaiblisse. Les relations économiques avec la France sont en effet en reflux depuis quelques années […] et même si l’usage de la langue française décline, là où pourtant elle était si vivante, si foisonnante, je pense qu’il n’y a aucune fatalité.

So, how is the role of French in Andorra changing, and what predictions can be made for its future? This article will focus on the links between language attitudes, ideologies and policies in Andorra, taking a holistic mixed-methods approach in order to offer the most comprehensive view of the sociolinguistic situation. In section 2, I will provide the overarching research aim of the study, as well as addressing related theoretical and conceptual issues. In section 3, I will provide an overview of the research context, by outlining the history of French in Andorra, as well as the circumstances and domains in which the language is used there today. In section 4, I will detail the methods employed in the study. In section 5, I then offer a quantitative analysis and discussion of data from a language attitudes questionnaire conducted in Andorra. These results comprise the basis for the critical discursive analysis of language ideologies and policy in section 6, in order to better understand the present and future of French in Andorra.

2. RESEARCH AIM AND THEORETICAL CONTEXT

The overarching research aim of this study is as follows: How can a holistic approach to language attitudes, ideologies and policy allow for a better understanding of the present and future status of French in Andorra? The adoption of such a broad approach to the sociolinguistic study of French in Andorra raises several contingent theoretical and conceptual questions, to be addressed in this section.

Firstly, what is meant by a holistic approach to the study of language attitudes and ideologies? Beliefs about language can be addressed from multiple theoretical and methodological perspectives. The field of social psychology offers quantitative paradigms for the examination of language attitudes – these studies frequently use direct attitude elicitation methods (such as surveys) or indirect methods (such as matched-guise or implicit association tests) in order to obtain large datasets and thereby elucidate the links between attitudes and behaviour patterns (Garrett, Coupland and Williams Reference Garrett, Coupland and Williams2003: 13). Language attitudes are typically evaluated along two distinct dimensions, status and solidarity (see Carranza and Ryan Reference Carranza and Ryan1975; Ryan, Carranza and Moffie Reference Ryan, Carranza and Moffie1977 for early studies; see Kircher and Fox Reference Kircher and Fox2019; Hawkey Reference Hawkey2020 for more recent work), these being associated broadly with instrumental and integrative value respectively. Meanwhile, the study of language ideologies has emerged from extensive work in linguistic anthropology and places central importance on the nature of belief systems as ‘derived from, rooted in, reflective of, or responsive to the experience or interests of a particular social position, even though ideology so often […] represents itself as universally true’ (Woolard Reference Woolard, Schieffelin, Woolard and Kroskrity1998: 6). The study of ideologies thus relies on the analysis of qualitative, discursive data and emphasises that belief systems are inextricably linked to social, political and economic power structures. A holistic approach to speaker beliefs about language therefore draws on both of these fields of inquiry, using both quantitative attitudinal data and qualitative analysis of ideologies.

Secondly, and following on from this, what are the benefits of mixed-methods work in the search for answers to the questions posed here? Mixed-methods work is not new in the study of language attitudes and ideologies, since the combination of approaches allows for the understanding of multiple ‘layers of meaning’ (Holmes Reference Holmes2007: 5), resulting in a holistic analysis of the sociolinguistic situation under investigation (see Kircher and Hawkey in press). However, care should be taken when devising and implementing mixed-methods protocols, to ensure not only that potential ontological and epistemological differences do not hinder analysis of the data yielded (Dewaele Reference Dewaele, Cook and Wei2009), but also that results from each method are ‘mutually illuminating’ and that ‘the end product is more than the sum of the individual […] parts’ (Bryman Reference Bryman2007: 8). The quantitative and qualitative components of this study provide depart from different epistemological standpoints and contribute complementary insights. While the qualitative attitudinal survey data aims to provide a representative overview of the situation, the qualitative ideological findings offer complementary, fine-grained insight from specific cases. While representativeness and broader generalization is not the aim of qualitative analysis of discursive data, it is nonetheless necessary to set testimonies in a broader context to allow for the most rigorous interpretation of the data. In order to understand the value and status of French against the global backdrop of late capitalism, Heller and Duchêne’s (Reference Heller, Duchêne, Duchêne and Heller2012) twin tropes of pride and profit will be used to structure the discussion, since this approach highlights the complex consequences of language management activities (as a subset of language policy, discussed below) as ‘[producing] resistances and conformities, disengagements and investments, and uneven material and symbolic profit’ (Heller and Duchêne Reference Heller, Duchêne, Duchêne and Heller2012: 19).

Finally, and continuing this discussion of language policy, how do recent advances in language policy theory contribute to such a mixed-methods analysis of speaker beliefs? The study of language policy has diversified and evolved in the last decades to encompass far more than the analysis of de jure policy texts. Spolsky (Reference Spolsky2004, Reference Spolsky and Spolsky2012) proposes a tripartite definition of language policy, made up of ‘language management’ (the efforts of a dominant sector of society to influence language use), speaker practices, and finally ‘the values assigned by members of a speech community to each variety and variant and their beliefs about the importance of these values’ (Spolsky Reference Spolsky and Spolsky2012: 5). Speaker belief systems, in the form of language ideologies, are of central importance to recent studies of language policy – Barakos and Unger (Reference Barakos and Unger2016) advocate for critically-led discursive approaches to language policy (DALP) scholarship, since ‘language policy is not least an ideological phenomenon that constructs, transports, and recontextualises ideologies about the value of languages and their speakers’ (Barakos and Unger Reference Barakos and Unger2016: 2). Following Fairclough and Wodak (Reference Fairclough, Wodak and van Dijk1997), DALP studies critically analyse texts as instances of social action. These individual examples of discourse are taken as indicative of language ideologies and can thus be interpreted as wider instantiations of language policy, following Spolsky’s (Reference Spolsky2004: 14) claim that ‘ideology is language policy with the manager left out.’ This in turn draws heavily on Foucault’s (Reference Foucault1982) notion of governmentality, in which macro-level government is dependent on micro-level practices and discourses to successfully achieve hegemony. In this study, I will discuss a public speech by given Emmanuel Macron in 2019, in his capacity as Co-Prince, in which he presents his vision for the future of French in Andorra, as well as his plans to strengthen cultural and economic ties between the two countries. In the absence of extensive de jure language policy in Andorra concerning the role and status of French,Footnote 1 this speech is a highly fruitful site for analysis, given its clear and comprehensive discussion of current top-down language policy strategies regarding French in Andorra (albeit from the perspective of France, rather than Andorra itself).

3. RESEARCH CONTEXT: THE FRENCH LANGUAGE IN ANDORRA

Andorra is one of the final vestiges of the Carolingian Marche d’Espagne, a series of fortified mountain counties used as a buffer zone to prevent Umayyad incursions north of the Pyrenees in the eighth century. In 1133, the Count of Urgell (who had hitherto controlled the territory) sold Andorra to the Bishopric of Urgell, who ruled the land with the help of the local nobility, the Caboets (Villaró Reference Villaró2011: 121–122). The system of Co-Princes was instituted with the signing of the 1278 Paréage of Andorra, and the Bishops of Urgell have passed down the title of Co-Prince since then without interruption. The successor of the Caboet nobility, the Count of Foix assumed the role of the other Co-Prince in 1278, which was passed to the Kings of Navarre in 1472, then to Louis XIII of France in 1620, as these territories were absorbed into their successor states. From the Kings of France, the title of Co-Prince passed to today’s heads of state. Given this historical association between Andorra and France, it is unsurprising that the French language retains a role in Andorran life today. However, the long-standing presence of France (and the counties and kingdoms that were eventually subsumed by France) does not imply centuries of French use in Andorra. Abbé Grégoire’s 1793 report sur la nécessité et les moyens d’anéantir les patois et d’universaliser la langue française made clear the Revolutionary stance towards regional languages (including Catalan) as antithetical to Jacobinism, although this is unlikely to have led to an increase in the use of French in Andorra for two key reasons. Firstly, the Revolutionaries rejected the status quo around co-governorship of Andorra, leaving the country vulnerable to annexation by Spain (Klieger Reference Klieger2013: 33), and so the homogenizing language ideologies in favour of French that circulated amongst the ruling classes in the wake of the Revolution did not take a firm hold in Andorra in this early period. Secondly, Catalan speakers in the Eastern Pyrenees (Northern Catalonia and Andorra) were arguably seen as valuable conduits between the French and Spanish during the Napoleonic invasion of Spain. Of course, this did not entail protection of Catalan in these areas, but nevertheless, surveys conducted by Prefects of the Empire provide evidence that Catalan enjoyed a high level of status across all social classes and that this was tolerated by the French government at the time (Merle Reference Merle2010: 151–153; Hawkey Reference Hawkey2018: 21).

The use of French among the general Andorran population increased in the twentieth century, with the introduction of the first French-medium schools in 1900 (Margarit and Monné Reference Margarit and Monné2010: 75, Jiménez-Salcedo Reference Jiménez-Salcedo, Jiménez-Salcedo, Hélot and Camilleri Grima2020: 149). French still occupies a central position as a medium of instruction in Andorra. There are currently three coexisting education systems – the French system (since 1900), the Spanish system (secular schools since 1930, confessional schools since 1882) and the Andorran system (established in 1982), with parents exercising free choice between them. French and Spanish are used as a sole medium of instruction in the French and Spanish systems respectively, while the Andorran system is fundamentally multilingual, with Catalan and French being jointly used until the age of 12 (Bastida Reference Bastida2003: 82). The Andorran system is the most popular (41.06% of all students in the school year 2018/19, Govern d’Andorra Reference d’Andorra2020: 15) followed by the French system (32.52% in 2018/19) – these figures thus reveal that 73.58% of all students in Andorra have been taught either exclusively or partly through the medium of French. As such, there is a relatively high level of French language competence in Andorra, with the general population on average self-reporting competence in French at 5.4/10 (behind Spanish at 9.3/10 and Catalan at 8/10, but ahead of English at 4.3/10 and Portuguese at 3.1/10), even though only 8.9% of the population claim French is their mother tongue (government statistics from 2018, Govern d’Andorra Reference d’Andorra2019: 10, 14).Footnote 2 It should be noted that, even though 5.4/10 may seem a low score given the amount of French-medium education in Andorra, 51% of Andorran residents are migrants who were not born and raised in the country, but instead came chiefly from Spain or Portugal (Govern d’Andorra Reference d’Andorra2020: 24). These self-reported language competence statistics are drawn from a randomized sample of residents of the country, and as such, around half of respondents are likely to be migrants (Govern d’Andorra Reference d’Andorra2019: 7) who may not have been greatly exposed to French through education. We can therefore presume that the self-reported levels of French competence will be far higher than 5.4/10 among Andorrans who have been educated in either the French or Andorran school systems. The same data reveal self-reported use of French to be low, with Andorran residents reporting to use French in just 6.5% of interactions, compared to 39.1% for Spanish and 45.9% for Catalan (Govern d’Andorra Reference d’Andorra2019: 15).

Andorran governmental language policies acknowledge the multilingualism of the country’s citizens, but only accord official status to Catalan. Other languages are not mentioned by name in Andorra’s two chief pieces of language legislation (see Govern d’Andorra Reference d’Andorra2000, Govern d’Andorra Reference d’Andorra2005), with French and Spanish only implicitly referred to in the discussion of the country’s ‘geographical proximity to two widely spoken languages [and] the Andorran tradition of teaching in these two languages’ (Govern d’Andorra Reference d’Andorra2000: 66, my translation from Catalan) in the context of how these languages pose a potential threat to the vitality of Catalan. This is reinforced in government statistics, where the official language of the country is listed as Catalan, and three ‘other languages’ are given as Spanish, French and Portuguese, in that order (Govern d’Andorra Reference d’Andorra2020: 6).

The government documents above make reference to a small community of Andorrans with French as their first language (8.9% of the total population or around 6900 people, Govern d’Andorra Reference d’Andorra2019: 10). French migration to Andorra saw its first major increase during the 1970s but has always been considerably lower than that from Spain or Portugal (Sáez Reference Sáez and Lluelles2004: 253). These populations are largely concentrated in the sparsely populated north of the country, notably in the villages of Pas de la Casa and Canillo (Margarit and Monné Reference Margarit and Monné2010: 58). All locations mentioned in this article are given in Figure 1, below.

Figure 1. Map of Andorra.

Existing studies that focus on multilingualism in Andorra have found that French is a language of greater prestige than Spanish (Margarit and Monné Reference Margarit and Monné2010: 58, 67, 71, 257), as evidenced by the continued popularity of the French education system (Ballarín Garoña Reference Ballarín Garoña2006: 218) despite the language’s limited presence in many aspects of daily life. The small community of French first-language speakers are generally upper-middle class in terms of occupation (Margarit and Monné Reference Margarit and Monné2010: 58). Most choose French as the home language, and the language used for communication with their children (Sorolla Vidal Reference Sorolla Vidal2009: 335), and Ballarín Garoña (Reference Ballarín Garoña2006: 209) reports that 36% claim to use French when interacting with members of the service industry – compared with 0% of members of analogous Andorran, Catalan and Spanish participant groups.

In short, French is a language with a long-standing historical presence in Andorra, but its role in the country today is ambiguous. One of the country’s Co-Princes is the French President and makes official addresses exclusively in French. The language is the medium of instruction (at least in part) for around three quarters of Andorran schoolchildren. Yet it holds no official status and is infrequently used, other than by a small migrant community concentrated outside of the major centres of population. This article will examine how prevailing attitudes and ideologies regarding French contribute to this complex situation, and what this can tell us about the future of French in Andorra.

4. METHODS

The first component of this study will be a quantitative analysis of attitudinal data, obtained through the distribution of a questionnaire in 2017–18. The questionnaire was completed by 173 participants (this equates to approximately 1 in every 445 residents of the country at the time of data collection). Most responses were gathered in the major urban centres of Andorra la Vella and Escaldes-Engordany, by means of the friend-of-a-friend technique, as well as through the researcher entering shops and public offices and asking service professionals to complete the survey and to distribute it to their contacts. Participants came from a representative sample of informants from a range of migrant backgrounds. This decision was taken in order to examine the presence of French in the wider Andorran population, rather than paying special attention to the aforementioned French migrant communities found in Canillo and Pas de la Casa. The questionnaire consisted of four parts:

-

- The first section gathered non-identifying personal information (age, sex, nationality, birthplace, profession). Age was treated as a continuous variable, with all other variables being categorical. Profession was classified according to the ‘major groups’ identified in the International Standard Classification of Occupations produced by the International Labour Office (2012).

-

- The second section enquired as to self-reported competence in and use of the various languages of Andorra. Participants rated their oral competence in each language from 1 (none at all) to 5 (fluent), as well as their frequency of use from 1 (never) to 4 (daily).

-

- The main section of the questionnaire consisted of a list of statements about the various languages of Andorra, their domains of use and the feelings they elicit. Respondents were asked to rate their agreement from 1 (completely disagree) to 5 (completely agree). These statements were repeated several times, each time referring to a different language, and then the order was randomized. Some stimulus sentences were adapted to elicit attitudes regarding the three ‘national’ languages (French, Catalan and Spanish), while others were also modified to refer to Portuguese (as the language of the largest non-Spanish speaking migrant group) and English (as an international lingua franca). For consistency across the analyses of different stimuli, this study only includes statements referring to French, Catalan and Spanish. The different stimulus statements will be presented in the analysis section.

-

- The survey concluded with an open-ended question, allowing participants to recount any linguistic experiences they considered relevant.

The demographic make-up of questionnaire respondents was as follows:

-

- Total N = 173.

-

- Age: Average = 39; Youngest = 15; Oldest = 73; Standard Deviation = 14.1.

-

- Sex: Male = 62; Female = 111.

-

- Nationality: Andorran = 88; Spanish = 48; Portuguese = 19; French = 10; Other = 7; Non-stated = 1.

-

- Birthplace: Andorra = 69; Catalonia = 41; Spain (other) = 18; Portugal = 18; France = 8; Other = 12; Non-stated = 7.

-

- Profession: Professionals = 56; Sales and service = 44; Students = 17; Clerical support = 16; Technicians = 14; Other = 22; Non-stated = 2.

The questionnaire data was quantitatively analysed in two ways. Firstly, mean scores for stimulus items regarding French were compared against the analogous stimulus statements for Catalan and Spanish, using t-tests and ANOVAs, as appropriate. Then, linear regression models were run on stimulus statements concerning French, using the Rbrul interface (Johnson Reference Johnson2009; Johnson Reference Johnson2019) in the R environment. The fixed effects were the same in all analyses – one model was run with demographic factors as fixed effects (sex, nationality, birthplace and profession as categorical variables; age as a continuous variable) with outliers removed as appropriate; another model was run with self-reported language competence and usage factors as continuous fixed effects. There were no random effects, since each questionnaire item was analysed separately (and as such, each respondent only contributed one token in any given model).

This quantitative attitudinal study will raise a number of key issues, which will provide the point of departure for an analysis of discourses and policies concerning French in Andorra. Following Spolsky (Reference Spolsky2004, Reference Spolsky and Spolsky2012) and Barakos and Unger (Reference Barakos and Unger2016) among others, this study takes a broad definition of language policy and will critically examine a range of texts in order to pinpoint relevant policies and ideologies, and to determine how these shape the current sociolinguistic situation of Andorra in France. Two types of texts are analysed. Firstly, a total of 27 Andorran residents were interviewed during fieldwork in Andorra in 2017–18, with contacts made through the friend-of-a-friend technique. Interviews were semi-structured, and as such there were very few predetermined questions – the intention was to elicit linguistic biographies from participants, with frequent themes including migration, multilingualism and education in Andorra. Secondly, I will examine extracts from a public address made by Emmanuel Macron during an official visit to Andorra in September 2019.

5. LANGUAGE ATTITUDES TOWARDS FRENCH IN ANDORRA

As discussed above, language attitudes are frequently evaluated along the dimensions of status and solidarity. In the questionnaire, pairs of stimulus statements were designed to elicit attitudes on these two dimensions for each language concerned. This analysis also examines responses to three further statements on the themes of integration and culture, which do not neatly fit onto the two key evaluative dimensions.

French as a language of status in Andorra

The following stimulus sentences were used to elicit attitudes on the status dimension:

-

- Knowing [French/Catalan/Spanish] will increase my chances of employment in Andorra.

-

- [French/Catalan/Spanish] is a useful language day-to-day.

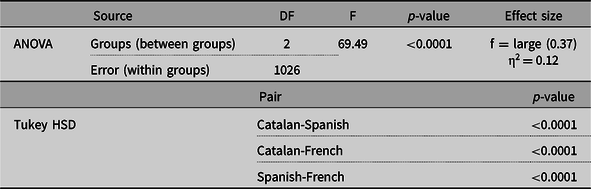

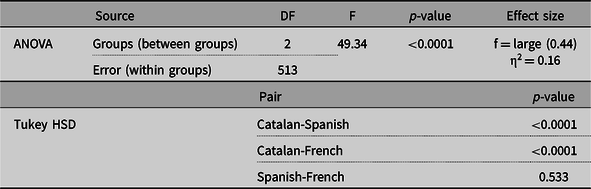

The average score given to the stimulus statements regarding French is 3.77Footnote 3 (N = 344, SD = 1.11), indicating moderate status value.Footnote 4 This is however much lower than the mean scores for Catalan (4.62, N = 343, SD = 0.7) and Spanish (4.14, N = 342, SD = 0.95), with a one-way ANOVA and post-hoc Tukey HSD tests confirming the difference between all group means as highly significant (p<0.0001), as shown in Table 1.

Table 1. ANOVA (and post-hoc tests) for French, Spanish and Catalan as languages of status in Andorra

It should also be noted that the score of 3.77 for French in fact represents the average of very different values for each stimulus item. The average score in response to ‘knowing French will increase my chances of employment in Andorra’ is 4.15 (N = 173, SD = 0.84), whereas the mean is only 3.39 (N = 171, SD = 1.22) for ‘French is a useful language day-to-day’. A one-tailed t-test reveals this difference between responses to be significant (p<0.0001, t = 6.76, Cohen’s d = 0.73). The high status of French as a language of potential employment is thus tempered by speaker attitudes that the language is not actually that useful in Andorran day-to-day life. In this respect, French yields different results to the other two languages – for Catalan, the difference between the mean results of each stimulus item is not significant (p = 0.08); for Spanish, the mean difference is significant, but the results are inverted, with ‘knowing Spanish will increase my chances of employment’ (3.82, N = 171, SD = 1) lower than ‘Spanish is a useful language day-to-day’ (4.46, N = 171, SD = 0.78) (p<0.0001, t = 6.49, Cohen’s d = 0.71). Spanish, contrary to French, is thus seen as useful on a daily basis, but its status as a helpful tool in the labour market is less highly valued, while Catalan is evaluated as highly useful both in daily life and the wider job market.

Given the significant difference between the mean results of the two questionnaire items regarding the status of French in Andorra, LRMs were run on each item separately, rather than conflating the two items into one scale. For the statement ‘knowledge of French will increase my chances of employment in Andorra’, only age functions as a statistically significant predictor (p = 0.03) – the negative correlationFootnote 5 means that older people show a tendency towards rating French less favourably as a language of employability. This may be linked to the importance of French in the Catalan and French education systems, which dominate in Andorra – older respondents are more likely to have attended the Spanish system in Andorra, or are otherwise migrants schooled elsewhere; see Table 2 below.

Table 2. Regression output for French as a language of employability in Andorra

For the item ‘French is a useful language day-to-day’, no demographic factors are significant. However, the factor groups French use (p<0.0001), Catalan use (p<0.01), French competence (p = 0.03) and Catalan competence (p = 0.04) were shown to be significant predictors. It should be noted that there are very strong positive coefficients for French use and Catalan use, implying that higher self-reported frequency of use of French and Catalan corresponds to a tendency to rate French as a more useful language on a daily basis; see Table 3 below.Footnote 6

Table 3. Regression output for French as a useful language in Andorra

French as a language of solidarity in Andorra

The following stimulus items were used to elicit attitudes on the solidarity dimension:

-

- [French/Catalan/Spanish] is a language that lends itself to the expression of feelings and emotions.

-

- [French/Catalan/Spanish] is a language I use with my friends.

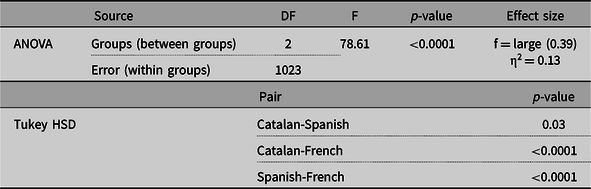

The mean score given to the stimulus statements regarding French is 3.09 (N = 339, SD = 1.37), indicating neutral solidarity value. As with status, this is much lower than the solidarity values accorded to Catalan (4.17, N = 344, SD = 1.05) and Spanish (3.94, N = 343, SD = 1.11), with a one-way ANOVA and post-hoc Tukey HSD tests again confirming the difference between all group means as highly significant (p<0.0001), as shown in Table 4.

Table 4. ANOVA (and post-hoc tests) for French, Spanish and Catalan as languages of solidarity in Andorra

As with status, the French average solidarity score of 3.09 is the result of two divergent means – ‘French is a language that lends itself to the expression of feelings and emotions’ scores 3.61 (N = 170, SD = 1.19), while the mean for ‘French is a language I use with my friends’ is only 2.57 (N = 169, SD = 1.34), indicating general disagreement with the stimulus sentence. A one-tailed t-test confirms this difference to be statistically significant (p<0.0001, t = 7.56, Cohen’s d = 0.82). Once again, this is unlike the results seen for Catalan and Spanish, where t-tests reveal no significant differences between the two stimulus items (p = 0.35 for Catalan, p = 0.08 for Spanish). As such, Catalan and Spanish show consistent solidarity ratings, with Catalan scoring slightly higher than Spanish, whereas French not only scores much lower, but there is also a significant discrepancy between the two stimulus items. While there appears to be a moderate feeling that French has emotionally expressive potential, people in Andorra largely disagree that it fulfils the role of in-group language, capable of generating solidarity.

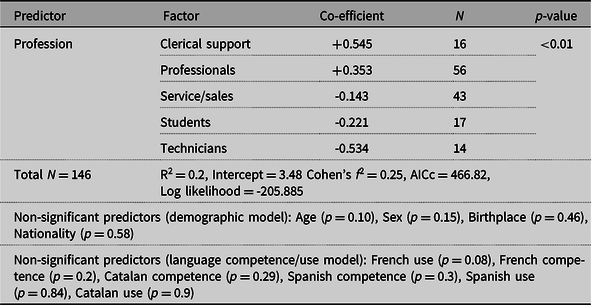

Considering the significant difference between French solidarity questionnaire items, the decision was taken (as with status) to run LRMs on each item separately. For the statement ‘French is a language that lends itself to the expression of feelings and emotions’, only profession (p<0.01) was statistically significant, though the most sizeable factors within the group displayed weak correlations, meaning that more data would be necessary to draw satisfactory conclusions; see Table 5.

Table 5. Regression output for French as a language of emotional expression in Andorra

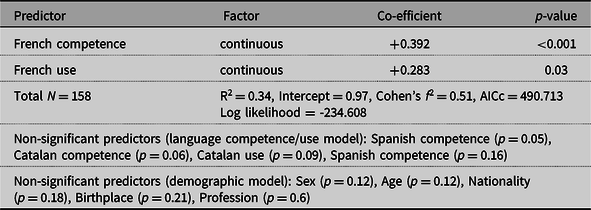

For the item ‘French is a language I use with my friends’, two linguistic factor groups serve as highly significant predictors of behaviour – French competence (p<0.001) and French use (p = 0.03). These are positive correlations with relatively high magnitudes of coefficients, so as self-reported competence or frequency of use go up, so does the likelihood of a higher rating for French for this item. Nevertheless, we need to remember that the mean solidarity values remain low. Therefore, French is not necessarily perceived as a language of solidarity, even among community members with high self-reported French competence or use, as shown in Table 6.

Table 6. Regression output for French as a language used with friends in Andorra

French as a language of integration in Andorra

The following stimulus statement was also included in the questionnaire:

-

- Knowledge of [French/Catalan/Spanish] is vital if one wants to integrate into Andorran society.

While this statement explicitly addresses integrative value, and therefore could feasibly be included with the solidarity stimulus items, this is complicated by the fact that Andorra is a country with a high proportion of migrant residents, many of whom are transitory and work in defined sectors of employment (chiefly hospitality and construction). In this context, ‘integration into society’ is arguably associated with access to certain rights (for example, Andorran citizenship) and accompanying job opportunities in more highly paid fields, and as such, does not sit comfortably within the categories of status or solidarity, and is addressed separately.

The average score given to this stimulus statement regarding French is 3.35 (N = 173, SD = 1.08), indicating neither agreement nor disagreement with the notion that French is a key means of integration into Andorran society. Spanish receives a similar score of 3.46 (N = 171, SD = 1), despite its very different role in Andorra when compared to French. Spanish is the widely used lingua franca and the language in which the wider population reports the highest competence (Govern d’Andorra Reference d’Andorra2019: 14), and yet this does not result in the language being considered as a vehicle of societal integration. A one-tailed t-test confirms that the difference between the scores for French and Spanish is not significant (p = 0.15). Catalan, however, scores highly with an average of 4.33 (N = 172, SD = 0.91), indicating general agreement that knowledge of Catalan is vital if one wishes to integrate into Andorran society (see also Jiménez-Salcedo Reference Jiménez-Salcedo, Jiménez-Salcedo, Hélot and Camilleri Grima2020: 148). A one-way ANOVA confirms that between group differences are significant, (p<0.0001), with post-hoc tests revealing that Catalan is rated significantly higher than French and Spanish, as in Table 7.

Table 7. ANOVA (and post-hoc tests) for French, Spanish and Catalan as languages of integration in Andorra

This offers insight into how ‘integration’ is perceived in the Andorran context. Rather than being associated with Spanish, a language that allows communication with almost all members of society, irrespective of migrant background or length of residence, true integration comes with knowledge of the country’s official language, Catalan. This then permits access to specific high-level domains (for example, interactions with local and national government, which legislature dictates should take place in Catalan) and hitherto unattainable sectors of the labour market.

The LRMs revealed no significant predictors for responses to the French stimulus item. French competence approaches significance (p = 0.07), and a larger participant sample would be helpful in determining the predictive power of this factor group.

French as a language of culture in Andorra

Two stimulus items address the role of French as a vehicle of culture in Andorra and beyond. These are addressed separately, and no composite tests were run, given the clear differences in content between the items (one asks about culture within Andorra, the other more generally). The first stimulus statement regarding culture was:

-

- The [French/Catalan/Spanish] language is an important component of Andorran culture.

The average score given for French is 3.68 (N = 172, SD = 1.02), indicating very slight agreement with the stimulus item. The score awarded to Spanish is even lower, at 3.28 (N = 172, SD = 1.14), representing a near-neutral attitude towards the stimulus. Catalan scored very highly, 4.76 (N = 172, SD = 0.53), indicating near total agreement with the stimulus item. A one-way ANOVA confirms that the differences between language groups is significant (p<0.0001), as in Table 8.

Table 8. ANOVA (and post-hoc tests) for French, Spanish and Catalan as important components of Andorran culture

It can be concluded that, in general terms, the Catalan language is seen as central to Andorran culture, supported by official state monolingualism in favour of Catalan. French is perceived as a more important component of Andorran culture than Spanish, arguably since the historic role and presence of French sets Andorra apart from most other Catalan-speaking areas (with the obvious exception of Northern Catalonia in France). By extension, Spanish is not regarded as especially ‘Andorran’ in cultural terms, despite it being the language with the highest rates of self-reported competence among Andorrans (Govern d’Andorra Reference d’Andorra2019: 14). The LRMs did not reveal any statistically significant factor groups for the French stimulus items, meaning that we cannot postulate any predictors of attitudes towards French based on demographics or language competence. The second stimulus item was:

-

- [French/Catalan/Spanish] is a language with a rich cultural heritage.

The mean score given to French is 4.06 (N = 171, SD = 1.12), indicating agreement with the stimulus item. Similar scores were awarded to Spanish (4.25, N = 172, SD = 0.88) and Catalan (4.33, N = 172, SD = 0.88), and while a one-way ANOVA reveals the presence of statistically significant difference in the sample (p<0.04), post-hoc tests show this only pertains between Catalan and French, shown in Table 9.

Table 9. ANOVA (and post-hoc tests) for French, Spanish and Catalan as languages with a rich cultural heritage

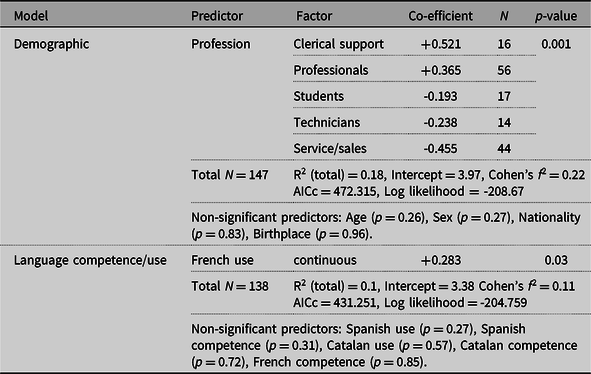

Therefore, while all languages are perceived to have a rich cultural heritage, this is slightly less the case for French than it is for Spanish and Catalan. The LRMs for the French stimulus item (see Table 10) reveal the factor group profession to be significant (p = 0.001). The categories of ‘trained professionals’ (e.g. teachers, doctors, accountants, nurses) and ‘clerical support workers’ show a tendency towards rating French more highly than the categories of ‘students’, ‘technicians’ (e.g. pharmacy workers, IT technicians) and ‘services and sales workers’. A potential difference between these two groups is linked to schooling – people in the categories who award lower scores to French have either not finished their education, or they are in jobs that require a lower level of education than the trained professionals who rate French more highly (though this is admittedly less clear for the category of ‘technicians’). The view of French as possessing broader cultural capital outside of Andorra may therefore be linked to level of education, although a larger data sample would help corroborate these findings. The LRMs also show French use to be significant (p = 0.03), indicating that French competence alone may not be sufficient to foster positive attitudes towards the language, but rather that frequency of use may also be required, as seen in Table 10 below.

Table 10. Regression output for the stimulus item ‘French is a language with a rich cultural heritage’

Summary of attitudes towards French in Andorra

The findings of this attitudinal study raise several points of interest. French scores lower than Catalan and Spanish across most metrics of status and solidarity, with solidarity ratings considerably lower than those on the status dimension. There is broad consensus that French is not a language of in-group solidarity in Andorra. Only when people report more frequent use of French is there a tendency towards higher solidarity evaluations, but use is generally low when compared to Catalan and Spanish. Nevertheless, there are some positive status associations with the French language – its role as a helpful tool in the labour market is seen as greater than that of Spanish (despite the low daily use of French compared to Spanish) and there is some awareness of its potential as a language with broader cultural capital outside Andorra. I now turn to a critical discursive analysis to learn more about how the French government approaches language issues in Andorra, about how language attitudes are enacted on a micro level, as well as to identify potential ideological currents regarding French in Andorra.

6. FRENCH IN ANDORRA: PROFIT WITHOUT PRIDE?

The results thus far have highlighted the status of French as a potentially valuable resource in the labour market. Heller and Duchêne (Reference Heller, Duchêne, Duchêne and Heller2012: 16) propose pride and profit as two co-constitutive discursive tropes that characterize the complex trajectories and processes constraining the globalized markets in which languages exist in late capitalism. Pride refers to the discursive means by which the modern nation-state sustains and legitimizes itself, calling on people as ‘citizens’ above other membership categories (Heller and Duchêne Reference Heller, Duchêne, Duchêne and Heller2012: 5). On the other hand, discourses of profit move away from ideas of language and identity and view language as a marketable skill (Heller and Duchêne Reference Heller, Duchêne, Duchêne and Heller2012: 8). Tensions between these two tropes will become clear when examining the complex language regimes that operate in Andorra, in light of the multilingualism and mobility of the population of this tiny country.

One such multilingual individual whose life has been shaped by mobility is Madalena,Footnote 7 who is originally from Portugal and is in her early fifties. She has been living in Andorra for around 25 years with her husband and son. Here, she describes the roles played by French and Spanish when it came to making decisions about her son’s education, both upon the family’s arrival in Andorra and later in life:

When I asked people from here, they recommended the French [school] to me [for my child]. The school is really good, you’ll get help with things, then to go to France it’s really close, going to Barcelona is different. Other doors are opened to you, French is a more important language […] [My son] went to the French school and then to university in Toulouse. Then, a year later, he wanted to do a masters, and he did that through Spanish. I said to him, ‘you need to do this in Spain, it’ll be better for you. You’ve already got French, but you need to ‘professionalise’ your Spanish, so if one day you have to work in Spain, it’ll be better’ (my translation from Portuguese).

The above fragment details a linguistic trajectory of two parts and is replete with discourses of profit. When Madalena arrived in Andorra, the French education system was presented as a clear choice over the other two options not only due to its reputation, but also because of the perceived greater opportunities available to French speakers. It should be noted that these advantages are not tied to integration within the new host society, but rather to prospective onward mobility to France for study or work. Andorra is a small country and therefore its linguistic marketplace (Bourdieu Reference Bourdieu1993) is fundamentally transnational, and the value accorded to different languages therein is derived from the relationship between Andorra and its larger neighbours and their languages (Hawkey and Horner Reference Hawkey and Horner2021). The usefulness of French is pointed out to Madalena as a language able to ‘open other doors’ for her son, with this statement immediately explained as meaning he could ‘go to France’, rather than stay in Andorra or return to Portugal. Chaparro (Reference Chaparro2021: 4–5) states that the competitiveness engendered by neoliberal thinking contributes to the detachment of language from culture and the construction of language as an ‘attractive “added value” for parent-consumers from the dominant majority.’ Madalena, as a recent arrival in Andorra making decisions about her child’s education, did not form part of the ‘dominant majority’ of Andorran society, but the same principles still apply. The transnational linguistic marketplace ascribes a high value to French language competence (despite its limited presence as a language of social interaction in Andorra), and this is of paramount importance to migrants when seeking opportunities for their children. Moreover, given Andorra’s small size, and the fact that much work in Andorra is seasonal (focused on ski-related tourism and hospitality), migrant interviewees frequently reported not expecting to stay long (even Madalena and her husband!), which also contributes to the choice of French as a language of education. Migrant populations understandably will not attach value to Catalan as the language of integration in the host country if there is little intention to stay, and so choose the French system over the Andorran one.

Years later, with a clear perception of the nuances of her son’s multilingualism, Madalena seeks to guard against his repertoire being in any way ‘truncated’ (Blommaert Reference Blommaert2010: 103) by recommending that he ‘professionalize’ his Spanish, in case he should wish to go to Spain to find work. Again, profit is clearly tied to mobility, and to the transnational marketplace that includes Andorra’s larger neighbours. Del Percio (Reference Del Percio2018: 256) states that for many with a mobility background, languages are more than just skills in and of themselves, and serve as ‘powerful tools that potentially enable individuals to package the “bundle of skills” that [they] should sell on the labour market.’ A ‘professional’ competence in Spanish is thus seen as a means of allowing Madalena’s son to work more effectively – as she says, ‘it’ll be better’. For our purposes, it is perhaps most interesting that discourses of profit focus primarily on French, and then only later on Spanish, reflecting our attitudinal findings regarding the status of these two languages in Andorra.

Despite the potential usefulness of French in the labour market, the attitudinal findings revealed that French is not perceived as a language of in-group solidarity. The following quote comes from Lluís, who was born and raised in Andorra to Portuguese parents and is now in his late teens:

It’s weird, you never really see the French community in Andorra. With the Portuguese, you quickly realise they’re Portuguese, because they speak it openly. It’s true that where I live in Encamp – well not just Encamp, but the whole central area – you don’t hear French that much. You notice French a lot if you go to Pas de la Casa. There, everyone speaks French […] [Here], you don’t notice that many people [speaking French], unless you’re hanging around the Lycée Français, and even there, you’ll hear a lot of Spanish. But maybe if you’re near [the Lycée] as the kids head home, you’ll hear a bit more French spoken, but it’s not a language you hear much in the street, you hear far more Spanish (my translation from Spanish).

Lluís immediately associates French language use with the French migrant community in Andorra, as opposed to seeing French as a potential language of identification for all residents of the country. The practices of French migrants are then compared to another group, Portuguese speakers, who are considered more visible due to frequent use of their language in public settings. The relative lack of visibility of French speakers is explained by reference to language practices (i.e. they seem to use French less in public) and geographical space. Andorra may be a tiny country – the border posts with France and Spain that serve as entrance and exit points for all transport are only 43km apart – but this does not render internal distances unimportant. Humanistic approaches to geography (see Entrikin Reference Entrikin1976, Tuan Reference Tuan1977) remind us that the perception of physical space is filtered through the prism of individual lived experience. For Lluís, French language use is largely geographically restricted to the village of Pas de la Casa. Physical space is created between Lluís, who lives in Encamp and spends most of his time in the urban centre of Andorra la Vella, and the ‘distant’, French-speaking village of Pas de la Casa (in fact only 17km from his hometown of Encamp, see Figure 1, above). Topography also contributes to this creation of distance – Pas de la Casa is situated at 2,080 metres altitude, compared to 1,023 metres in Andorra la Vella and 1,238 metres in Encamp. Aside from the small enclave of the Lycée Français in Andorra la Vella (and even this is heavily caveated with ‘you’ll hear a lot of Spanish’), French is constructed as a geographically distant language within Andorra, restricted in usage and not heard much outside a few private homes. Any attempt to include French in discourses of pride in Andorra would thus suffer from a crisis of inauthenticity. French is not a language Andorrans can assemble round in the interests of ‘the modern nation-state’s signature structure of feeling’ (Heller and Duchêne Reference Heller, Duchêne, Duchêne and Heller2012: 5) since firstly, that role would be accorded to Catalan as the sole official language of the country, and secondly, French is not heard frequently in much of the country, and is only associated with specific geographical and social spaces.

We are thus faced with a situation in which French is a language clearly associated with discursive tropes of profit in Andorra, but less so with discourses of pride, and this entails further consequences, since these two tropes are co-constitutive. Indeed, pride allows for the production (and unequal distribution) of profit to be legitimized (Heller and Duchêne Reference Heller, Duchêne, Duchêne and Heller2012: 5). Discourses of profit attached to French in Andorra may suffer from low legitimacy, given the lack of presence of the language. In other words, if French is used so little on a daily basis in Andorra, how useful can it really be in terms of social and economic advancement? Conscious of the shifting fortunes of French in Andorra, Emmanuel Macron broached the issue in his address to the Andorran people in September 2019:

Ce à quoi j’aspire, comme coprince, c’est que […] la langue, la culture française retrouvent une place de choix dans l’imaginaire des jeunes Andorrans. Que de nouvelles légendes s’écrivent. Que de nouveaux héros partagés contribuent aux légendes à venir, celles qui ont aussi tressé nos histoires. Et c’est à vous tous, femmes et hommes d’Andorre, élus, responsables économiques, éducatifs et culturels, qu’il appartient d’agir en fidélité à l’histoire du pays et à l’esprit de la Constitution que s’est choisie le peuple andorran.

Macron explicitly addresses the lack of Andorran national sentiment invoked by the French language through the use of intertwining tropes of historicity and civic responsibility. The writing of ‘future legends’ with ‘new shared heroes’ understands and acknowledges the mythical nature of the most powerful existing ties which bond France and Andorra. The figure at the centre of the foundation myth of Andorra is the Frankish Emperor Charlemagne, who is alleged to have granted a statute of independence to Andorra as a reward for the inhabitants’ bravery and support, and to this day enjoys the status of honorary father of the nation (Hawkey Reference Hawkey2019). Macron redeploys this mythical historical past to foster a spirit of connection between France and Andorra, while also laying the responsibility for the building of such a bond squarely with Andorrans as part of their civic duty. The French language is thus placed at the heart of Andorranness, and if citizens wish to uphold their constitution, they need to not only embrace the French language, but also promote it. Macron’s aim to boost pride and national sentiment attached to the French language shows a degree of understanding of the nature of the issues – it is precisely this lack of pride that threatens to undermine any instrumental value associated with French in Andorra. However, any strategy for the successful promotion of French in Andorra needs to fully take into account the complex demographic characteristics of the country. Mendes (Reference Mendes2021) provides other examples of language policy texts in France with pride-related and profit-related teloi, reminding us that ‘the coexistence of the ideologies represented by [these policies with different teloi] is a prime of example of the complicated interplay between […] centers and peripheries (Pietikäinen et al. Reference Pietikäinen, Kelly-Holmes, Jaffe and Coupland2017)’ (Mendes Reference Mendes2021: 190). This centre-periphery relationship is also important in the present data, since Andorra is an example of a multiply peripheral space. Geographically, it is found high in the Pyrenees, far from the power centres of Paris, Madrid and Barcelona. Strategically, it is a microstate of little prominence on a global level and thus constitutes a periphery between two powerful neighbours acting as centres. Demographically, over half of Andorran residents are migrants with limited political rights, thus representing a visible social ‘periphery’ in the nation. It is this final interplay between centre and periphery that may cause pride-motivated language policies in favour of French to falter. Calling for a development of national pride and collective sentiment, while clearly helpful, may be of limited effectiveness in a country with such a large migrant population. If France wishes to ensure the future vitality of French in Andorra, such policies with pride-related teloi would need to be complemented with other initiatives that underscore the attractiveness and instrumental utility of French to migrant populations – tropes of pride and profit are, after all, co-constitutive.

7. CONCLUSIONS

We now return to our main research question – how can a holistic approach to language attitudes, ideologies and policy allow for a better understanding of the present and future status of French in Andorra? The range of methods adopted in this study has offered different complementary insights into the current and future vitality of the French language in Andorra. In short, French occupies a complex position. On the one hand, it is a language of historical and current significance, highly present in education and a key component of the transnational linguistic marketplace in which Andorra exists. On the other hand, its use is geographically and socially restricted. This contradiction is reflected in the broad range of results. The language attitudes survey reveals that participants believe French to possess value as a potential vehicle of social advancement in terms of employability, but that it does not fulfil the role of in-group language of solidarity. Critical examination of semi-structured interviews confirms that discourses about French in Andorra are characterized by tropes of profit, but that this is undermined by limited usage of the language in Andorran daily life. Language policy, in the form of political speeches, tries to tackle this imbalance by encouraging links between the French language and Andorran national identity. Although this approach directly addresses a clear shortcoming (i.e. the lack of collective sentiment associated with French), I believe that future successful promotion of French is contingent on the inclusion of non-French-speaking migrant communities, who may only settle in Andorra for a limited period of time. In addition to discourses of historicity and national pride, these efforts should underscore the opportunities and skills associated with French language competence. Perhaps then, to paraphrase Emmanuel Macron’s speech given at the start of the article, balance will be restored and the relationship between France and Andorra will be strengthened.