Why, for all of us, out of all that we have heard, seen, felt, in a lifetime, do certain images recur, charged with emotion, rather than others? Reference Eliot1

The current dilemma

In 2006 I wrote a brief article in this journal outlining the potential use of narrative as an adjunct to psychiatric training and practice through its use in developing advanced communication skills. Reference Wallang2 One of the main arguments for its employment was the ability of a narrative framework to elucidate meaning. In this current article I would like to expand this argument further.

The emphasis in psychiatry since its inception has been on post-Enlightenment thinking. However, the philosophical underpinnings of the alleged triumph of reason have more recently come under substantial critique, especially for shortcomings in understanding clinical presentations. Reference Porter and Berrios3-Reference Foucault and Howard5 More significantly, continued attempts to discern ‘truth’ through the reduction of mental processes to biological correlates have failed to deliver despite an increasing reductionist approach. This has left contemporary mental health practitioners in a quandary, unsure if reason alone can provide a workable understanding of the complexities the mind presents on a daily basis.

In this article I will argue that the imagination provides an essential and powerful framework for current practice, redirecting us from a reliance on a wholly reason-based philosophy of psychiatry. I will also argue that this new and dynamic framework encompassing the imagination constitutes a more meaningful interpretation of the mind.

I do not intend to make a case for cultural psychiatry taking a central place, as has been argued elsewhere, Reference Bracken and Thomas6,Reference Littlewood7 or the importance of spirituality. Reference Kleinman8 Moreover, nor do I intend to argue for a new therapy, although the use of narrative in this capacity has been well researched and explained. Reference Dein9 Instead, my aim here is to argue for the development of a practical philosophical framework that is more than a mere adjunct to current psychiatric conceptual thinking but more flexible and audacious than the current Enlightenment dogma. Furthermore, I do not advocate an abandonment of reason, rather a redirection from it as a sole approach. I remain committed to a unified neurology and psychiatry that is informed by a solid scientific base, using hypothesis testing and harnessing recent advances in molecular genetics, imaging and the environment. I am therefore in agreement with Professor Kendler, Professor of psychiatry at the Virginia Institute of Psychiatric and Behavioural Genetics, who, when interviewed by Dominic Fannon for this journal in 2006, Reference White and Epston10 was asked whether he thought psychiatry was ‘brainless or mindless’, and gave this enlightened response.

We are currently at some risk of becoming mindless. We have the challenge of integrating the advances that will be coming our way from genetics, imaging and molecular and systems neuroscience without losing our way as an integrative discipline. Although my ‘day job’ is studying genetic risk factors for psychiatric illness, it is clear that the environment is very important for most disorders and some of the critical aetiological factors in disease are tied up in deeply human processes such as meaning. Reference White and Epston10

This line of argument leads to a fundamental question: how do we integrate the myriad advances in science with a meaning-centred philosophy that both benefits patients and leads to a greater understanding and characterisation of their unique psychological processes?

Changing systems of thought: working towards a meaning-centred philosophy of psychiatry

Nobody can know my mind. Nor, for that matter, can they know anyone else's mind. Yet I am no nihilist; I do not argue that everything is unknowable. There are, nonetheless, parts of experience which are beyond complete objectification, and the mind, I believe, is one of these parts. My philosophical position is thus somewhere between G. E. Moore's Reference Fannon and Kendler11 refutation of scepticism and Wittgenstein's doubts surrounding unequivocal certainties, Reference Moore and Muirhead12 with an emphasis on the latter (some would argue that this middle road is an untenable position). Reference Wittgenstein13 I can logically extend this position to the view that all experience is essentially subjective, involving at every step the meaning an individual assigns to experiences. Moreover, because of the importance of this meaning in interpretations of experience, experiences are impossible to objectify fully, because whatever interpretation is reached will remain unrepresentative of every other mind's interpretation.

Current theoretical practice, however, rests on a 300-year-old philosophy, shaped by the writings of René Descartes (1596-1650) through Karl Jaspers (1883-1969, a psychiatrist and exponent of Neo-Kantianism who left psychiatry for philosophy), Reference Butchvarov14 holding that the mind can be known, quantified and objectified. Reference Foucault and Howard5 This explains the use of homogenous criteria-based classification systems such as DSM-IV Reference Jaspers15 and ICD-10. 16 Whether this notion arises from a stubborn reliance on duality 17 is beyond the scope of this article. However, it underpins current research that attempts to categorise facets of thought common to all minds, while excluding any reference to meaning.

My position is that any attempt to submit divergent subjectivity to the crude analysis of this psychophilosophical doctrine fails to encapsulate the diversity of the human mind, thereby losing sight of subjective reality and leading us to a dangerous misrepresentation of it as an objective truth and ultimately to a distorted understanding.

One might argue that I would have some insight into the mindset of a person with schizophrenia if I myself had such a condition. Taken at face value, this seems logical. However, the fallacious nature of this proposition is immediately evident when one begins to peel back the layers of conscious thought and understands that perception is intrinsically linked to assigned meaning and therefore relies on the individual's unique contacts within the world around them. Reference Baker and Morris18 So although this empathic experience would bring me marginally closer, it cannot deliver a valid interpretation of a differing mind.

I do not intend here to critique the validity of mental illness as a concept, or to deconstruct the notion of psychopathology. A certain bedrock must be maintained in order for progress to be made. Reference Fannon and Kendler11 Reason, however, is not sufficient for the formation of a meaningful understanding of the mind; reductionist arguments Reference Foucault and Howard5 have led us further away from an accurate representation of mental phenomena. This problem is not insurmountable; the apparently contradictory concepts of reason and imagination can, when employed judiciously, lead us to a better conceptualisation of human thought. Moreover, this union of reason and imagination can be accomplished by the use of narrative as a guiding philosophical framework. Let me illustrate what I mean with an example from clinical practice.

A worked example: what is ‘meaning’?

A man in a state of extreme anxiety was brought to the ward. He had presented to physicians following a marked deterioration in his physical health, secondary, in the main, to the sequelae of advanced chronic viral hepatitis and consequent liver failure. As we explored his past, it became increasingly clear that his suffering extended beyond the physical to include several episodes of severe mental illness.

He recounted a long history of drug dependence, beginning with alcohol before eventually turning to heroin. He had found some relief in the opiate substitute methadone, but remained tethered to his addiction. He explained that over a period of years there had been several treatment attempts and numerous out-patient appointments, but no real breakthrough. Needless to say, the drug misuse had taken a heavy toll on his health and he appeared physically very unwell. While performing the routine physical examination, I noticed a small book lying on a side table next to the patient's bed. The cover of the book was unremarkable, save for a spattering of stains. Its title, however, provoked a spark of interest in me: Seng Chao Teachings. Reference Mulhall19 Having a passing interest in Taoism myself, I was intrigued. I mentioned this to the patient, who immediately began to speak enthusiastically about the book, which dealt with the Mudhyamika teachings written by the 5th-century Buddho-Taoist monk Seng Chao.

The patient spoke with great clarity and eloquence about the narrative contained in the book, outlining its influences both on his life and in shaping his philosophical outlook. His immersion in the material became obvious during our discussion, as did his dedication to revealing its meaning.

Both the narrative and the meaning contained therein had acted as a kind of mental balm for the patient, assuaging the turbulence of his breakdown and providing his only lasting relief. Our conversation deepened and, gradually, a highly tuned mutual understanding developed. There was now a much greater transparency to his thoughts that allowed a clearer framework of psychological meaning to be established. He mentioned how he found solace in one particular passage of text, which at first glance seemed trivial. It described how motion could be found in inertia. He claimed it had proven the fundamental cornerstone of his own thoughts throughout his crises.

Still puzzled: some help from Wittgenstein and Heidegger?

Encounters like this are rare. We are not naturally inclined to explore meaning in routine practice, where the overriding philosophy promotes diagnosis as paramount. In this case, however, the patient emphasised how much better he felt having had the opportunity to discuss a topic of such importance to him personally.

This worked example stimulates a number of discussion points. It seemed to suggest that each of us has our own personal narrative, absorbed over the course of a lifetime, on which we might draw at times of difficulty to strengthen our will and inform our choices. The patient in this example had made a determined effort to study and understand the teachings of Seng Chao and, as a consequence, had learned their principles so well that they had become interwoven with his own thought processes. He had, it appeared, attained consummate fluidity with the narrative; his mental state although precarious seemed to be held in some degree of therapeutic equipoise, despite his ravaged body and ongoing physical problems.

This ability of certain narrative structures to incorporate themselves into one's psyche and form a philosophical framework is not without precedent. Philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein learned ‘The Three Hermits’, a short story by Leo Tolstoy, word for word. 20 For him, the story demonstrated more about humanity than had been expressed in all extant philosophical teaching.

… We have forgotten your teaching, servant of god. As long as we kept repeating it we remembered, but when we stopped saying it for a time, a word dropped out, and now it has all gone to pieces. We can remember nothing of it. Teach us again… Reference Monk21

Wittgenstein absorbed Tolstoy's narrative over his lifetime, making it an integral part of himself, using its nebulous internal form to offer relief at times of anxiety and later informing his second major work, the Philosophical Investigations. Reference Tolstoy and Maude22–Reference Wittgenstein24 Wittgenstein states ‘Uttering a word is like striking a note on the keyboard of imagination’. Reference Baker and Hacker23 Language is taken to mediate between thought and reality; hence Wittgenstein conceptualises communication as ‘playing on the keyboard of the mind’. Reference Tolstoy and Maude22

Narrative structure can become so familiar with the person that it is eventually appropriated, persistently informing thoughts both subconsciously and at higher levels of reasoning. As with the ‘Three Hermits’ story and Wittgenstein's case, the Seng Chao narrative had formed a dynamic relationship with the patient, a relationship both intense and personal. It functioned as an internal looking glass, through which he could analyse and understand his actions. Had the book not been discussed, thus exploring its meaning for him within the imaginative construct of his mind, then the encounter would have been all the poorer for it. Moreover, the encounter revealed how a story can be learned so well and in such detail as to become part of one's very substance, serving eventually as an interface for social interaction - transparent, subconscious and yet no less potent for it.

‘The imaginative leap’ in practice

All this leads to questions concerning the origins of our actions and thoughts. It is probably impossible to know this in every case, but one can sometimes recollect a vague memory trace in behaviours such as those learned without any conscious awareness: dressing in a particular manner or performing a daily ritual. These are rehearsed and repeated until the original memory has all but vanished. Although there are well-established neural correlates of behaviour and memory, these have been shown to be heavily influenced by perception and ascribed meaning in both their cognitive coding and decoding. Reference Fogelin25,Reference Loftus and Palmer26 This explains why when two individuals see the same stimulus they will have very different interpretations and memories because of their differing perceptions. There is room for narrative exploration in attempting to explain these nuances, something that would be important for patient communication, especially understanding. Moreover, it has been demonstrated that memory is not like a video recording, with a continuous sensory image. The mind acts more like a ‘puzzle’, piecing cognitions together. It is reliant on our true memories and what seems most likely dependent on our knowledge and perception of the world. Reference Fogelin25,Reference Loftus and Palmer26 The accumulated narrative and meaning for a patient would certainly have a bearing on this creative process. Indeed, evidence attests to the remarkable plasticity of the brain and how seemingly similar experiences have the potential to change neuronal circuits in different ways. Reference Loftus, Miller and Burns27

These references, however, are vital in that they enable us to begin to understand our subsequent actions and explain our own and others' idiosyncrasies. They also allow us to connect with people successfully. When any two people meet - as with my meeting with the patient described earlier - there is an interface between their accumulated narratives, particularly evident in their use of linguistic expressions and imagery. Only by taking account of each patient's accumulated narrative can one hope to fully understand the emotional component of that individual and develop a significant degree of meaning.

The meaning the patient attributed to his mental health experiences was linked to his narrative experiences. In his case, these experiences involved reading, but they could equally be garnered from the myriad narratives that surround us each day, from stories told by a taxi driver to the papers we read and the television programmes we watch. We are embedded in narrative; everything we do is catalogued in its bold typeface. Furthermore, becoming acquainted with this phenomenon is vital for the development of advanced communication. Roland Barthes (1915-1980), a philosopher and semiotician who investigated the link between narrative and linguistic expression, Reference Kolb, Gibb and Robinson28,Reference Allen29 elucidates this situation well:

… moreover, in this infinite variety of forms, it is present at all times, in all places, in all societies; indeed narrative starts with the history of mankind; there is not, there has never been anywhere, any people without narrative; all classes, all human groups, have their stories… and are we to infer from such universality that narrative is insignificant? Reference Barthes30

Had I not investigated the meaning the patient ascribed to his existence and experiences, my understanding of him would have been depreciated. It is only through a thorough understanding of the meaning ascribed to these ‘contacts’ in the world that any valid interpretation can be constructed. Reference Barthes31

Without this engagement, my interpretation would have been based on a crude statistical analysis gleaned from a textbook on addiction. My ‘objectivity’ on this basis would have been an illusion and a study in behaviourism. Instead, I took an imaginative leap involving empathy and the creation of a theoretical framework of his mind by listening, observing and, critically, employing the imagination to derive meaning. I here define the imagination as a creative process of restructuring information to form a greater meaning, although there has been an ongoing re-evaluation of this concept throughout history. Reference Elliot32

The narrative triad

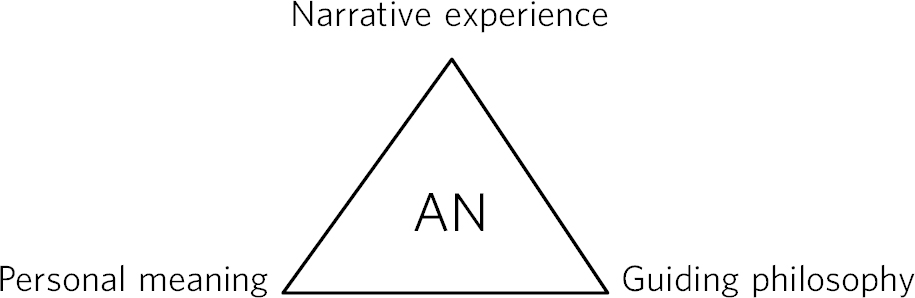

Readers will by now be aware of a number of alternative uses for the term ‘narrative’. There are in my mind three distinct uses of the term ‘narrative’: the first use is the ‘personal narrative’, otherwise known as ‘the patient's story’. This relates to the semiotics of the individual, the signs, symbols and systems they use for communication. It is heavily influenced by culture. Reference Kearney33 An understanding of this is essential in patient communication, allowing the patient's ‘voice’ to be articulated and understood. The second distinct use is the ‘narrative philosophy’; which encompasses the ‘guiding patient philosophy’. This is vital to understanding mental resolve, and inextricably linked to future recovery. The third and final use is ‘narrative meaning’, for example in the elucidation of personal meaning to events. This meaning constitutes the underlying mental constructs of the patient and is intricately linked to their perception of individual circumstance. For example: why do individuals have such differing experiences to similar situations? The explanation comes in part from their perception and the meaning they assign to the experiences. The rest will be a complex interplay of neural processing yet to be elucidated. These three interacting ‘narratives’ can be seen in Fig. 1.

Fig 1 The narrative triad. AN, accumulated narrative.

In Fig. 1 the accumulated narrative constitutes the patient's total life narrative: lived experiences, hopes, dreams, anxieties and memories. Each of the three narrative areas form a dynamic interaction with the accumulated narrative; the patient's recollection of their ‘story’ to the clinician is heavily influenced by the accumulated narrative. This real-time re-enactment will have reciprocal effect on the accumulated narrative by modifying the lived experience. Changes in the accumulated narrative would furthermore influence the individual's guiding philosophy and in doing so the meaning assigned to perceptions. It is hoped that the clinician, in collaborative exploration with the patient, will skilfully tease out these areas to improve understanding and therefore communication and management as a whole. The triad of personal meaning, narrative experience and guiding philosophy are underpinned by the philosophies of Heidegger, Barthes and Wittgenstein. The future of communication within psychiatry lies in an understanding of how these ‘narrative networks’ interact and how each singular narrative interacts and is used with other cultural elements within the network. Such an appreciation and analysis of their use will ultimately reveal multiple layers of depth precipitating the elucidation of personal meanings. For a greater understanding of the general theory of networks see Dorogovtsev & Mendes. Reference Hodge and Kress34

If the reader would allow me some latitude I would like to make use of a metaphor: the encounter I have described is, I think, analogous to early interpretations of the pyramids in Giza by historians during the 1700s. Before the 18th century these colossal structures were seen as grand tombs for long-dead pharaohs, conceptualised by historians as little more than exalted resting places for powerful dynasties and a reflection of their continued divinity. This reductionist approach makes the pyramids a fait accompli: stone boxes surround the remains of powerful people, a fact which, given past experience and ‘common sense’ logic, ‘means’ that the structure was a burial chamber. No attempt is made to seek the true ‘meaning’ of the pyramids that reflects on their cultural and contextual framework. The true meaning of these structures had in fact been lost over millennia. It was only after the French archaeologist Champollion (1790-1832), considered the ‘father’ of Eygptoplogy who famously deciphered the hieroglyphs, took a leap of imagination by embedding these ‘facts’ in an imaginative analysis of meaning, thereby inferring that these ‘tombs’ were known to contemporary Egyptians as ‘resurrection machines’. Reference Dorogovtsev and Mendes35 They were not built with the explicit intention of aggrandising the dead but rather with the aim of resurrecting their occupants' souls and transporting them into the heavens (believed to be located in a star cluster named ‘the Indestructibles’ with the traditional name Kochab, more recently Beta Ursae minoris (βUMi/β Ursae Minoris), thereby ensuring lasting existence in the afterlife. This was the ‘essential leap’ - the amalgamation of culture, reason, and the imagination - a completely new way of conceptualising a narrative account. Against a philosophical background of reason, reductionism - due to its neglect of meaning - can never completely describe subjective experience. It is only through imagination, against a background of reason that we can hope fully to understand meaning.

It is true that good psychiatry has always involved an interest in the patient and a thorough exploration of their past. I would argue, however, that meaning has been sidelined; in the current system of thought, diagnosis is paramount. This has been a weakness that has alienated patients. Reference Champollion36 I am not advocating an abandonment of diagnosis - simply a redirection from it as a sole emphasis. Diagnosis is important but not at the expense of patient meaning. Moreover, the current trends in recovery and the many user groups asking for psychiatry to ‘give a voice’ to their experience forces a conceptual redirection. It advocates a re-establishment of our priority, allowing a greater parity of the patient ‘experience’ and ‘voice’. This also extends to the needs of carers, where narrative interpretation has been shown to facilitate a greater understanding of their overall needs. Reference Shepard, Boardman and Slade37 This means a fundamental shift in systems of thought, placing the filter of diagnostic criteria at a lower level in a bid to address these concerns. In making this argument I would qualify my thoughts by maintaining that the use of refutation remains essential to the development of psychiatry as a truly scientific specialty. Reference Benbow, Ong, Black and Garner38 Having said this, Hume's problem of induction still remains stubbornly defiant, namely that no finite number of specific observations can ever logically entail an unrestricted general or universal conclusion, Reference Popper39 although this has recently been challenged. Reference Norton40 Note, however, there is ongoing debate with regard to the applicability of Popperian falsifiability and refutation as applied to psychoanalysis/psychotherapy. Reference Howson41

Conclusions

Each mind is analogous to the enigma of the pyramids. Without meaning a deeper interpretation is beyond our reach. This use of imagination is possible in everyday practice and is essential to the advancement of patient understanding in psychiatry. As an apparently logical and compelling theory, reductionism instead leads us further from our patient's experiences into a barren field of diagnostic criteria and, ultimately, a cultural dead end.

Adopting this new approach, however, requires a greater understanding of cultural references as well as fundamental change in our systems of thought. If we are to understand our patients more completely, we must ask ourselves to whom or to what, in their despair, they might turn. In the answer to this question is the foundation of a successful interaction between physician and patient that encourages frank disclosure and benefits both parties equally.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.