In 2004, WHO called on the private sector to take action to address the problems associated with food marketing to children(1). This followed from the publication of a systematic review in the UK that established an association between advertising of food through television (TV) and children's knowledge about food, their preferences and behaviour(Reference Hastings, Stead and McDermott2). These findings were used as evidence for the development of a regulation in the UK restricting food advertising to children under the age of 16 years(3).

The UK findings were confirmed by a second systematic review conducted in the USA for the Institute of Medicine (IOM) of the National Academies of Sciences(Reference McGinnis, Gootman and Kraak4). As a result, the IOM recommended that the food and beverage industry shift its marketing practices to children away from products high in added sugar, salt and fat, and stated that if the industry proved unable to achieve such a reform voluntarily then Congress should intervene with legislation. In the European Union (EU) as well, the then Health and Consumer Commissioner stated in 2005 that the food industry needed to take voluntary action to stop ‘advertising directly to children’ or face legislation(Reference Mason and Parker5).

It was into this environment that food industry ‘pledges’ to ‘change’ food marketing to children began to emerge in 2005–2006. Although voluntary in nature, the pledges are quite different from the self-regulatory ‘guidelines’ and ‘codes’ developed by the food and advertising industries in earlier years(Reference Hawkes6). These guidelines and codes were concerned only with guiding the content of advertising; in contrast, the pledges impose restrictions on the foods that can be advertised. Guidelines and codes were also generally issued by an individual company or trade group (e.g. food industry trade associations, self-regulatory organisations for advertising); pledges, in contrast, involve a series of participating companies with a secretariat hosted by some form of trade group.

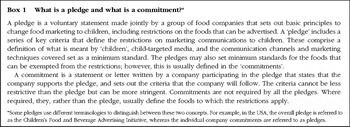

Box 1 What is a pledge and what is a commitment?*

*Some pledges use different terminologies to distinguish between these two concepts. For example, in the USA, the overall pledge is referred to as the Children's Food and Beverage Advertising Initiative, whereas the individual company commitments are referred to as pledges.

The present paper identifies the pledges on food marketing to children around the world, examines their content and discusses their potential to reduce the harmful effects of food marketing to children.

Methods

The study was conducted between April 2009 and December 2009. Pledges were identified initially through a country-wide questionnaire administered for a related project (for details, see Hawkes and Lobstein(Reference Hawkes and Lobstein7)). During the process, the International Food and Beverage Alliance (IFBA) made available an online resource listing the pledges, which was used thereafter(8). Individual companies and two of the drivers behind the expansion of the pledges globally, IFBA and the World Federation of Advertisers (WFA), were contacted when information was not available or unclear. Codes of practice or guidelines issued by single companies were excluded. Pledges on soft drink availability in schools were excluded when they contained no reference to promotional marketing(Reference Hawkes9).

In the analysis, ‘pledges’ were distinguished from ‘commitments’ (Box 1). Each pledge and individual commitment was read in detail and its content compiled into a series of tables. Information collected about each pledge included the secretariat, country(ies) covered, participating companies and the criteria used to define the marketing restricted by the pledges and commitments. These criteria comprised ‘children’ and ‘child-targeted media’, ‘communication channels’ and ‘marketing techniques’, as well as the food exempted by the restrictions, including the minimum acceptable ‘nutrient criteria’ established by some companies (typically by ‘product category’; Appendix 1). Multinational companies were counted as one company, even though they may have different management units in each country. In some cases, the named ‘company’ was owned or otherwise linked with another company, introducing complexity into classifying the companies. This information was recorded (Table 1) and a judgement made when counting the number of companies, depending on the company and the pledge. The sales and geographical reach of the participating companies were also examined and notably absent companies were identified.

Table 1 Food industry pledges on food marketing to children as of December 2009

*Date of ‘implementation’ unless otherwise stated.

†The number of company participants changed in 2010 for some of the pledges. For example, six members of the European Snack Association joined the EU Pledge and Cadbury and Wrigley joined since they were bought out by other companies; one further company joined IFBA (Ferrero) and the Australian Responsible Children's Marketing Initiative (National Foods Ltd).

‡This pledge varies from the other nine pledges in that it sets minimum nutrient criteria in the core pledge.

§In 2009, published commitments were identified for eight of the company members of the Brazil Pledge. A further two statements of general support for the core pledge were identified, as were two translated versions of global pledge/guidelines on the Brazil company websites. In 2010, a further eight company commitments were identified, some of which were dated 2009, but these were not available in 2009 and hence were not included here.

∥No commitments were identified for the pledges in Russia, South Africa and Thailand.

¶Grupo Bimbo is a member of the IFBA Pledge. It had not drafted its commitment to the pledge in 2009, but did so in 2010. The food company Ferrero also joined IFBA in 2010.

**This number would be eighty if the three Brazilian companies are counted as one in the Brazil Pledge, and ninety if the further specific commitments made to the Brazil Pledge are included (see footnote §).

The pledges and commitments are ‘living documents’ that are updated over time. Changes made subsequent to the end of the research period may be viewed at www.yaleruddcenter.org/marketingpledges; this database, which includes all the information about pledges and commitments, is updated regularly. Notable changes since December 2009 are reported in Table footnotes and in the text.

Results

In December 2009, there were thirteen pledges on food marketing to children worldwide (as of April 2011, additional pledges had been made in India, the Gulf States, Mexico, the Philippines, Switzerland and Turkey; the European Soft Drinks Association had published a new pledge on the ‘digisphere’ and the WFA was still planning to develop more pledges in developing countries and in non-EU countries in Europe(8)). Of the thirteen published by December 2009, three were specific to the soft drinks industry, one to the fast-food industry and the rest were food industry wideFootnote *. The first two pledges were initiated in 2005–2006 by soft drinks industry trade associations; one pledge was made in 2007, four in 2008 and six in 2009.

Nine of the pledges were national, two were regional and two were global (Table 1). The national pledges existed in seven countries: in three Western countries, in one ‘transitional’ country and in three developing countries. The two regional pledges were both in Europe. One of these pledges – the EU Pledge – was the model on which pledges in developing or transitional countries were based. The two global pledges were made by the International Council of Beverage Associations (ICBA) and IFBA.

Ten of the thirteen pledges required participants’ commitments. In these pledges, each company is required to publish its own ‘commitment’ to the pledge, which may contain more stringent definitions than specified in the pledges. In three of these pledges, no published commitments were identified, and in a fourth, not all companies had published commitments (all in developing or transitional countries).

The remaining three of the thirteen pledges required no commitments from participants. All three pledges were specific to the soft drinks industry and also covered related issues relevant to obesity and health, such as availability in schools. For these pledges, the criteria set out in the pledge cover all participants.

Pledge participants and coverage

In total, fifty-two companies participated in the thirteen pledges, of which nineteen were members of more than one pledge (Appendix 2). Thirty-three companies had published individual commitments to the pledges. Just over half of these thirty-three companies (n 17) had published separate commitments to more than one pledge (Appendix 2). Eight of the companies had made global commitments to the IFBA Pledge (Table 2). In total, the thirty-three companies had published eighty-two different commitments (Table 1).

Table 2 Global commitments made to the IFBA Pledge as of December 2009Footnote *

IFBA, International Food and Beverage Alliance.

* Grupo Bimbo was a member of IFBA in 2009 but had not published its commitment; its commitment was published in 2010. The company Ferrero also joined IFBA in 2010 and published its specific commitment the same year.

The number of companies that participated in the pledges ranged from two to twenty-four per pledge (Table 1). PepsiCo and Coca-Cola participated in the largest number of pledges (eleven each), followed by Kellogg's, Mars, Nestlé and Unilever (nine each), and Kraft (eight) and General Mills (seven). Six of these eight companies were ranked among the top ten packaged food companies in worldwide sales in 2009, with the remaining two being the two largest breakfast cereal manufacturers worldwide(10). All eight had made global commitments to the IFBA Pledge.

There were also notable cases of companies with relatively little or no participation. Tyson Foods and Heinz are both among the world's fifteen largest food companies but neither participated in any pledges. Danone (France) was the twelfth largest food company worldwide in 2009, but had signed just four pledges and was not a member of IFBA. The world's largest fast-food restaurant chain, YUM! Brands, participated in just two pledges and was not a member of IFBA. The second largest, McDonalds, belonged to five pledges and had developed its own global guidelines for marketing to children; however, these were less restrictive than the commitments they had made to national pledges and did not meet the IFBA criteria.

Like McDonald's, some of the companies that were not members of IFBA had published global guidelines that attained neither the IFBA standard nor, indeed, the standards in the regional or national pledges they had signed. These included the Cadbury Marketing Code of Practice (a company that was bought by Kraft in 2010 so making it a participant of the EU Pledge), the Campbell's Soup Company Global Commitment to Responsible Advertising, Heinz Children and Youth Guidelines, Hershey's Global Marketing Principles and McDonald's Children's Marketing Global Guidelines. The less restrictive nature of these guidelines is illustrated by the lower age limits adopted by Cadbury (under the age of 8 years) and Campbell (under the age of 6 years).

Pledge content

All pledges included definitions of children and child-targeted media, the communication channels and marketing techniques covered and criteria for foods exempted from the restrictions (Appendix 1).

Child definition

All pledges (and commitments) except one defined children as individuals under the age of 12 years: the Australia Quick Service Restaurant (AQSR) pledge applies to children under the age of 14 years. Seven companies also differentiate between children under 6 years of age or ‘pre-school’ and those between 6 and 11 years of age.

Child-targeted media definition

Ten of the pledges defined ‘marketing directed at children’ as media in which children (as defined above) comprise ≥50 % (or >50 %) of the audience. Three had adopted a more general definition (such as ‘majority’ of audience, as shown in Table 3). However, many company commitments set more stringent definitions of child-targeted media (Table 4). For example, Mars included media with a child audience of ‘>25 %’ in all commitments. Fewer than half of the companies with more than one commitment (seven of seventeen) applied consistent definitions of child-targeted media across all pledges to which they belonged. In the case of Unilever, its Canadian and US commitments included a more detailed definition compared with its other pledges.

Table 3 Key criteria defined in the pledgesFootnote * as of 2009

* The table includes definitions in the pledges, not in the commitments, which may vary from the criteria set as the minimum requirement in the core pledge.

† Changes in 2010 indicate that more pledges are now covering more communication channels and marketing techniques. For example, the Canadian Children's Food and Beverage Advertising Initiative updated its pledge in 2010 to include more communication channels and marketing techniques, and the Union of European Beverages Associations published a new ‘digisphere’ pledge that included company-owned Internet.

‡ The IFBA (International Food and Beverage Alliance) Pledge.

§ The Australian Responsible Children's Marketing Initiative and the Australian Quick Service Restaurant Industry Initiative for Responsible Advertising and Marketing to Children.

∥ Includes the two pledges that state ‘all marketing communications’.

Table 4 Company-specific commitments that go beyond the minimum requirement in the core pledge, as of December 2009

*In 2010, Coca-Cola changed its definition of child-targeted media to ‘≥35 %’ from ‘≥50 %’ meaning that its commitments went beyond the pledges that adopt the ‘>50 %’ definition.

Communication channels and marketing techniques

Altogether, the pledges referred to eleven communication channels. TV was included in all thirteen, and third-party Internet (i.e. Internet advertising, excluding company-owned websites), print, radio and schools appeared in most. However, beyond this, there was distinct variation between pledges (Table 3). For example, the Brazil Pledge covered TV, radio, print, third-party Internet and schools, whereas the South African Pledge included only TV and schools (in and in the proximity of). Cell phones, cinema, video or computer games, DVD, company-owned websites and viral marketing were covered in some pledges but usually not included. Point-of sale (in stores or restaurants) was never covered by the pledges (although included in a small number of specific company commitments).

None of the pledges restricted the use of entire communication channels. Rather, they restricted specific marketing techniques on those channels. Advertising dominated the marketing techniques covered. It was included in all thirteen multicompany pledges and was the only technique referred to in six of the pledges, including the IFBA and EU Pledges. Other techniques referred to in some pledges include the use of licensed characters, popular personalities and/or celebrities, as well as premium offers (typically in advertising but not packaging), product placement, interactive games and messaging on cell phones (Table 3).

Company commitments rarely exceeded the minimum criteria for communication channels and marketing techniques covered – with the exception of six IFBA members, notably General Mills, Kellogg's, Mars and Unilever. For example, two of these global commitments included a limited amount of point-of-sale.

Importantly, frequent exceptions and exclusions were included in the definitions of communication channels and marketing techniques (Table 5). Packaging and brand characters were always excluded and point-of-sale promotions were only occasionally included. In schools, anything that was not ‘direct’ advertising was excluded.

Table 5 Exceptions and exclusions to communication channels and marketing techniques covered in the pledges and commitments, as of December 2009Footnote *Footnote †

* Changes in 2010 mean that more pledges are now covering more communication channels and marketing techniques (see footnote to Table 4).

† There is also an example of an exclusion that applies only to franchisees. The interactive games and product placement restriction for Burger King in the US Pledge ‘does not apply to local activity engaged in by independent franchisees of Burger King Corporation’.

‡ Secondary schools are not covered because of the age limit.

Foods exempted and nutrient criteria

Nine pledges allowed companies to exempt some foods from the marketing restrictions, provided they were defined on the basis of scientific principles. This exemption was often based on the minimum acceptable nutrient criteria: fifty-four of the eighty-two commitments made by nineteen companies adopted this option (the AQSR Pledge also adopted a set of nutrient criteria that defined which foods could be advertised to its participants). The criteria always varied between companies, and in some cases also varied between commitments made by the same company to different pledges. As a result, a total of twenty-nine different nutrient criteria were used across all pledges (Table 6). Some criteria were quite typical. For example, 480 mg Na and 12 g added sugar per serving reoccurred frequently. In most cases, companies did use the same nutrient criteria in some of their commitments, but not in all, leading to a very complex picture. For example, Burger King participated in four pledges. In the USA and Canada, the nutrient criteria were the same; however, in the EU Pledge, Burger King had a higher upper limit for Na and restricted artificial additives. In addition, the criteria for Burger King's Australian franchisee, Hungry Jack's, were different. Campbell's Soup was another example, with variations between the three national pledges of which it was a member (Australia, Canada and the USA).

Table 6 Characteristics of food criteria set in the pledges and commitments, as of December 2009

*Commitments have not been published in three of these nine pledges, and only partially in a fourth. As a result, there are very few definitions of the food criteria in the developing/transitional countries, and nineteen of the fifty-one companies have not published any definitions.

†The Australian and European soft drinks pledges.

‡Seven companies also state in all of their published commitments that they will not advertise any food to children under the age of 6 years. In addition, all commitments on schools cover all foods (i.e. for marketing in schools only).

§The Australia Quick Service Pledge (nutrient criteria for children's meals). This pledge does require commitments; hence, companies have the option of setting more stringent criteria, which is the case for one of the participating companies.

∥That is, the definition is vague, available only internal to the company, or list the foods to be covered.

¶The ICBA (International Council of Beverages Associations) Pledge covers practically all drinks, but has some exceptions.

**In two commitments, companies state that they have defined nutrient criteria, but these are published internally and not available to the public; in three, specific products are named but no nutrient criteria are provided; and in two, a very general criterion is provided: ‘following healthy diet guidelines’.

The criteria differ in other ways too. Most of the units used for the criteria were ‘per serving’, but serving size varied. For example, in the EU, a serving of Cereal Partners Worldwide (CPW) breakfast cereals was 30 g, whereas servings for General Mills in the USA ranged between 26 and 50 g. Thus, even though the criteria for energy and sugar appeared to be the same globally, in practice they differed according to serving size. It was also difficult to compare criteria between companies because some used ‘% calories per × nutrient per serve’ rather than ‘g/serving’. Most of the nutrient criteria – with a few exceptions – included maximum acceptable energy, but there was variation with regard to the inclusion of fat (saturated fat, trans fats, cholesterol, etc.), added sugars, Na and ‘positive’ nutrients or foods. Moreover, most had different criteria for different food categories, rather than an ‘across-the-board’ approach, with the number of categories ranging from very few to many. Nearly all nutrient criteria took a ‘threshold’ approach in which the amount of a nutrient cannot exceed a certain level; however, Danone utilized a scoring model.

Some companies did have consistent criteria across commitments, notably Kellogg's (in 2010, Pepsi issued a new global set of nutrient criteria to replace the many different criteria used in their different specific commitments in 2009(11)). Kraft Foods also used consistent criteria for all markets except the USA, where it shifted its criteria to conform to a now defunct point-of-purchase labelling scheme. However, there were exceptions here as well: in four of its commitments, Kellogg's permitted a higher Na limit for a certain brand of waffle. Kraft Foods permitted ‘reduced in’ products to be marketed even if they did not meet the nutrient criteria in other ways. The ICBA Pledge, too, covered all beverages, with the exception of water, fruit juice, dairy-based beverages and ‘products specifically formulated to address critical nutritional deficiencies’.

Although using nutrient criteria to exempt foods from marketing restrictions is the dominant approach, a significant minority – two pledges and twenty-one commitments – did not apply any exemptions based on nutrient criteria. The marketing restrictions thus applied to all their foods and beverages (or with a small number of named exceptions). Mars was notable for including restrictions on marketing ‘all foods’ in all of its commitments (although this changed in 2010 with the publication of a new commitment to its EU Pledge, in which different foods are treated differently). In addition, a small number – one pledge and seven commitments – took an alternative approach, such as specifically naming the foods that can or cannot be advertised. In some cases, nutrient criteria had not been published. Ferrero, for example, stated that nutrient criteria would be set at a ‘later stage’, whereas Sanitarium and Sadia stated that they used internal criteria not available to the public.

Options to opt out

The Canada and US Pledges originally included the option that restrictions on advertising need apply to only 50 % of a company's advertising, provided that the remaining 50 % depict ‘healthy lifestyle’ messages. In December 2009, the US Pledge announced that the 50 % option would be eliminated as most companies either did not select this option or increased the proportion from 50 % to 100 % in the first years of the pledge. Canada also eliminated this option in 2010; all participants had already implemented commitments to 100 % of their advertising.

Analysis

A changing environment

The development of food industry pledges on food marketing to children is impressive: thirteen pledges, fifty-two companies and eighty-two commitments in just 4 years (and several more published in 2010–2011 and continuing); two global pledges applicable to wherever participating companies conduct business; a significantly expanded pledge in the world's largest advertising market (the USA) just 2 years after the first edition; several cases of pledges and commitments becoming more restrictive and/or comprehensive over time (which also continued throughout 2010); and many commitments that extend beyond the minimum standards set in the pledges. There is also a relatively high degree of transparency: all pledges, along with their revisions, are posted online, often with detailed background information.

However, conducting the analysis proved to be a highly complex task and revealed some puzzling aspects of these pledges, including limitations in their coverage and inconsistencies between different pledges, as well as between commitments made by the same companies to different pledges.

Pledge coverage

A major limitation for all pledges is that companies can choose whether or not to participate. Although participating companies tended to be among the largest in their markets and/or for their products, there are many more companies that manufacture foods of interest for children who did not participate in the pledges; a recent analysis in Australia found that only fourteen of the forty-one companies that engaged in advertising food to children through TV participated in the national pledge programme(Reference King, Hebden and Grunseit12).

This limitation is particularly notable at the global level. Forty-four of the fifty-two companies that participated in pledges were transnational companies or engaged in transnational activity; however, only 16 % of these companies had made global commitments to the IFBA Pledge. As discussed, many other highly transnationalised companies had not made global commitments, but produced global guidelines that did not attain the IFBA criteria and/or the pledges to which they were signatories in countries and regions.

As a result, geographical coverage is limited. Burger King, for example, participated in five pledges covering sixteen of the approximately seventy-one countries where it does business (including all the EU countries covered by the EU Pledge); therefore, just 22 % of its national markets are covered by pledges. Cadbury conducted business in at least fifty countries, but participated in five pledges that represent just 10 % of its territory (this changed in 2010 when the company was taken over by Kraft). These are just two examples among many.

A closer look at the definitions in the pledges also suggests that they were not concerned with the full range of marketing to which children are exposed. The pledges covered only marketing that is targeted ‘directly’ at children (i.e. made exclusively for them), meaning that marketing strategies directed at teenagers and/or adults but also viewed by children, and ‘family-oriented’ marketing strategies targeting parents and their children, were excluded. According to analyses conducted in the USA and Australia, a significant amount of food advertising to which children are exposed, on TV at least, occurs within general audience programming in which <50 % of the audience comprises children(Reference Holt, Ippolito and Desrochers13, Reference King, Kelly and Gill14). These child-targeted media definitions were also notably less stringent compared with two jurisdictions with government regulations on marketing to children. In Québec, where advertising of all products to children under the age of 13 years is banned, the restriction includes all advertising in programmes in which children make up >15 % of the audience, even if the product is targeted at all age groups (provided the advertisement has some appeal to children). Where children make up ≤15 % of the audience, the advertisement must not be designed to be appealing to children(15). In the UK, advertising of high-fat, high-sugar and high-salt foods on programmes that attract ≥20 % more viewers younger than 16 years of age relative to the general viewing population is restricted(3). Although this definition has itself been criticised for being insufficiently restrictive, it is more restrictive than the most stringent food company definition of ≥25 % of the audience being under 12 years of age (JC Landon, personal communication).

With regard to communication channels and marketing techniques, the exclusions and exceptions described in Table 5 further limit the extent to which children are covered. The commitments made by fast-food companies are a case in point: the AQSR Pledge in Australia and the McDonald's and Burger King commitments in the USA specifically state that forms of marketing commonly used for fast-food products – point-of-sale and packaging – are exempted from the techniques covered by the commitments. In the USA, a recent study showed that the use of youth-oriented cross-promotions on packaging – a communication channel that is always exempted – increased during the period when the pledge was implemented(Reference Harris, Schwartz and Brownell16).

Another coverage limitation concerns the nutrient criteria. Taking the case of breakfast cereals, the criteria do not distinguish between non-sugared cereals (e.g. Cornflakes, Cheerios, etc.) and sugared versions (e.g. Frosties, Coco Pops); further, the vast majority of sugared cereals – even those containing over 40 % sugar (at the time of writing) – are not restricted according to the nutrient criteria of General Mills, Kellogg's and CPW(Reference Harris, Schwartz and Brownell17). This contrasts with the UK regulation, where the only breakfast cereals permitted to be advertised to children are muesli and ‘wheat biscuits’ with no added sugar.

Differences between pledges and commitments

The analysis conducted in the present study shows that there is a certain degree of uniformity between the pledges and company commitments to different pledges, but that there is also a great deal of difference. For example, McDonald's and Burger King participate in the AQSR Pledge, as well as in others; therefore, their definition of ‘children’ applied to individuals under 14 years of age in Australia but under 12 years elsewhere. The result is that a supposedly uniform, industry-wide effort to ‘change’ food marketing to children is actually a highly complex picture with numerous exceptions and inconsistencies. (These details can now be identified through the searchable database set up at: http://www.yaleruddcenter.org/marketingpledges/.) Several potential explanations for these variations can be offered: differences in political, public and market pressures, target markets, products and internal company practices.

Food marketing to children is on the agenda of some governments around the world: over twenty-five countries have made a statement regarding their intent to act on the issue, and approximately twenty countries have developed, or are developing, actual policies(Reference Hawkes and Lobstein7). In some markets, the issue has become the subject of media scrutiny and/or activism by non-governmental organisations (NGO). In these countries – such as the USA, Canada, Australia and various European countries – the pledges represent a response to these political, public and market pressures. At the EU level, the food industry acted after being placed under pressure (and threatened with regulation) by the European Commission. At the global level, WHO has called on large transnationals to take action on food marketing. Another pressure has been the actual implementation of a statutory restriction on broadcast advertising in the UK to children under the age of 16 years with a stringent set of nutrient criteria, leading to concerns by the advertising industry that similar restrictions would be applied in other countries. These pressures have also translated to differences among pledges. In 2008, the US Federal Trade Commission (FTC) called on the Children's Food and Beverage Advertising Initiative to broaden their definition of ‘marketing’, specifying company-owned Internet, video, computer games, DVD, cell phones and word-of-mouth (i.e. viral), and in 2009 this became the first pledge to cover these techniques (in contrast, the EU Pledge covers only TV, print and third-party Internet)(18).

These pressures do not exist in all countries and for all companies to the same extent. This may explain in part why pledges have not been developed in more countries and why relatively few companies have made commitments to the IFBA Pledge. It is notable that the developing countries where pledges have been initiated – Brazil, Thailand and South Africa – are also countries where there have been proposals for regulation. Even in these countries there exist less political and public pressures, indicating perhaps why most of the participating companies have not published specific commitments to the pledges.

Along with general pressures, there may be official prevailing standards that influence the definitions in the pledges. In Canada, for example, all nutrient criteria must be consistent with certain government-set standards for claims, and some follow the Heart and Stroke Foundation (an NGO) criteria for their Health Check™ point-of-purchase symbol. So whereas Campbell uses the same energy and Na criteria in the USA and Canada, their fat limits in Canada are slightly less restrictive because they follow Health Check™. In Australia, Campbell's nutrient criteria are different since they follow the provincial government standards set for schools. Australia is the only country where the government has some limitations on the advertising of premium offers, and the Australian pledges are also the only pledges that include that restriction.

Differences in the target market may also influence the definitions. For example, the soft drink industry pledges and Coca-Cola (the only exclusively soft drinks company) cover ‘all beverages’ (although with some exceptions) and are thus apparently more comprehensive than pledges and commitments with nutrient criteria. However, an analysis by the FTC in the USA shows that teenagers are the main target of soft drinks marketing (96 % of youth-oriented marketing expenditure by soft drinks companies in 2007 relative to 4 % for young children), suggesting that this more restrictive approach has few implications for existing soft drink marketing practices(18). In contrast, the vast majority of breakfast cereal marketing is targeted at children under the age of 12 years (in the USA, at least), and these companies have all adopted nutrient criteria (which, as already noted, permit all but a small number of their sugared cereals to be marketed to children). Breakfast cereal formulations – as for other products – also vary between different national markets(Reference Lobstein19), and this could explain the variation in nutrient criteria between different markets. CPW, for example, has a lower Na limit than General Mills global, US or Canadian commitments, even though CPW is a partnership between Nestlé and General Mills.

Differences in product portfolios may also explain some of the differences in nutrient criteria. For example, the approximately 200 mg/serving standard for Na adopted by CPW and Kellogg's is lower than the commonly used 480 mg/serving. However, these companies market breakfast products that are lower in Na compared with, say, pre-prepared meal products, salty snacks or cheese. Indeed, the only Kellogg's product advertised to children with a higher Na content – waffles – is excluded from the Na limit. Danone also has a Na limit of approximately 200 mg, but its product portfolio consists almost exclusively of fresh dairy products. Fonterra in Australia has a notably higher than typical per serving criteria for Na for their leading product, cheese, which is a high-Na product.

Different companies have different internal practices, structures and cultures. There may also be differences between operating units of the same company (e.g. different brands and countries). It could be speculated that this is a reason for differences in definitions between companies. For example, different companies may have different ways of classifying or measuring their target audience (perhaps explaining some of the differences in definitions of child-targeted media). Indeed the way the pledges are structured suggests that companies favour having the freedom to mould the criteria to their own practices. Of note, though, this includes extending beyond what other companies are willing to do. For example, along with their commitments, Kellogg's, General Mills and Mars include messaging on cell phones, company-owned websites, a limited amount of point-of-sale and sponsorship of kids clubs, sports events and product-branded toys – none of which appear in the pledges.

WHO recommendations on food marketing to children

In May 2010, WHO released a set of recommendations to guide member states on how to reduce the harmful effects of food marketing to children(20). One of the key recommendations is that ‘governments should be the key stakeholders in the development of policy… to set direction and overall strategy to achieve population-wide public health goals’. Development of the pledges represents a direct challenge to this recommendation – the type of ‘self-regulation’ advanced through the pledges is led by the industry, although sometimes in response to government pressure or encouraged by government entities.

WHO also recommends that the aims and objectives of policies on marketing to children be ‘to reduce the impact on children of the marketing of foods high in saturated fats, trans-fatty acids, free sugars and salt’ by reducing ‘both the exposure of children to, and the power of, marketing’. This is not the policy aim of the children's marketing initiatives reviewed in the present paper, which (at least initially) say that they pledge to ‘change’ food marketing to children.

Another WHO recommendation is that in the light of ‘national circumstances and available resources’ it may be necessary to implement measures to reduce marketing to children step by step. However a comprehensive approach has the highest potential to achieve the desired impact. The pledges certainly represent a stepwise rather than a comprehensive approach, given the limitations in the coverage that have already been discussed.

‘Governments should set clear definitions for the key components of the policy…’ is another key recommendation. The pledges do include clear definitions; however, these criteria have not been set by the government, thus preventing, as also recommended by WHO, ‘a standard implementation process’. It is notable that an attempt by the US government to set a universal standard for nutrient criteria – intended for use by all company participants – reportedly met with significant opposition from the food industry(Reference McKay and Brat21). In the UK as well, government-set definitions of age, audience and nutrient criteria were all opposed by the food industry.

Nevertheless, governments have also tended not to develop comprehensive approaches. Governments are, through statutory regulations and engagement in self-regulatory processes, encouraging more restrictions on specific marketing techniques(Reference Hawkes and Lobstein7). However, the two countries that have in the past proposed relatively comprehensive approaches – Brazil and France – ended up with a regulation requiring warnings or messages instead. Even the most restrictive approach in the world to date, in the UK, covers only broadcast advertising.

Conclusion

The food industry has a long way to go if its pledges are to comprehensively reduce the exposure and power of marketing to children. That the differences between pledges and commitments appear to be a response to external and possibly internal circumstances suggests that they are not primarily driven by public health concerns, making it difficult to judge whether one pledge or company is ‘better’ than another in terms of public health. Although this is speculative, it behoves the companies to be more transparent about why these differences exist and why coverage is not universal. Moreover, limitations in pledge coverage give the impression that, in both letter and spirit, the intention of the companies involved is not to reduce food marketing to children as much as they possibly can, but just to limit some direct marketing of very high-fat, high-salt, high-sugar products to children.

However, government action has also not been comprehensive thus far, and, unlike leading food companies, governments have not as a whole tended to develop a structure on which to build incremental change. The question is thus whether the pledges are making a meaningful contribution to the gap left by governments, or whether the pledges are in fact being used to deflect governments from taking the more comprehensive action that WHO acknowledges would have a far greater impact. That the differences between pledges around the world reflect political (and other) pressures suggests that the government leadership recommended by WHO will be necessary if the industry is to take a more comprehensive approach towards ensuring that children are exposed to as little marketing – especially particularly powerful marketing – as possible.

Acknowledgements

The present study was funded by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. The authors have no conflict of interest to declare. C.H. was Chair of the committee that advised WHO on its recommendations on marketing food to children. C.H. conducted the content analysis of the pledges with the guidance of J.H; C.H. and J.H. prepared the paper for publication. The authors acknowledge the guidance and comments provided by Kelly Brownell, Marlene Schwartz and the marketing research group at the Yale Rudd Center for Food Policy and Obesity. Thank you also to Jane Landon for reading an earlier version of the paper. The authors would also like to acknowledge the assistance of representatives of WFA and IFBA in identifying the pledges.

Appendix 1

Definitions used in the content analysis

Appendix 2

Company participation in the pledges

*Multinational companies were counted as one company even though they may have different management units in each country. The companies that were owned by or otherwise linked with another company were either counted as a single company or as part of the parent company, depending on the circumstances and the pledge.

†This number increased during 2010 as a result of new signatories to existing pledges and new pledges (see http://www.yaleruddcenter.org/marketingpledges/).