Kabbalistic Diagrams, Scientific Diagrams

“One who begins the study of this science [חכמה] must know that he must first learn all of the drawings [הציורים], and how all the worlds descend [משתלשלים] one after another. And all of them must be drawn [מצוירים] before him so that he comprehend and understand these matters.”Footnote 1 So begins the final chapter of “Introductions and Keys Appropriate for All Who Would Enter the Science of the Kabbalah to Know” [הקדמות ומפתחות שראוי לכל הנכנס לחכמת הקבלה לדעת אותן], an introduction to the Kabbalah, apparently of early sixteenth-century Italian provenance.Footnote 2 The complete introductory course is extant in one manuscript and hasn’t a single diagram. Instead, as a kind of final project, the student is instructed to draft a large and complex drawing to represent the knowledge acquired in the preceding chapters on the basis of the very precise and technical verbal instructions to which the final chapter is entirely devoted. To be a student of the Kabbalah is to visualize its knowledge as a graphic no less than a mental image.Footnote 3

The importance of the diagrammatic image to kabbalists stands in sharp contrast to their relative invisibility in scholarship. Long neglected by scholars of Kabbalah, diagrams have figured as eye-candy illustrations alongside unrelated discussions and as raw material for book-jacket designers. Even when recognized as intrinsic features of kabbalistic works, they have been dismissed as “concealing much more than they reveal,” in the words of Gershom Scholem.Footnote 4 Scientific diagrams were similarly neglected by generations of historians of science, no doubt as a result of prejudices that strongly favored word over image; this neglect, however, was replaced with steadily growing interest beginning some thirty years ago.Footnote 5 With fashionable tardiness, the visual materials of the Kabbalah are now being interrogated for their potential contribution to a more embedded history that goes beyond theosophical concepts to treat epistemic, hermeneutic, performative, and pedagogical dimensions of kabbalistic culture. Much of this recent work exposes the shared discursive and schematic constructs of early modern science and Kabbalah.Footnote 6 In the present paper, I turn my attention to medieval sources to examine the appropriation of the visual and rhetorical languages of astronomy and natural philosophy by the classical kabbalists and what it reveals about how they conceptualized their endeavor.

The fact that basic research on kabbalistic diagrams—by which I mean systematic collection, classification, and contextualization—began just a few years ago rather than in the first century of modern scholarship belies their significance in the eyes of the kabbalists themselves. As most of what follows will focus on materials produced by Jews, I here invoke the learned Christian Hebraist and scholar of the Kabbalah, Guillaume Postel (1510–1581). Writing in mid-sixteenth-century Venice, Postel listed the main genres of Hebraica for his interested coreligionists.Footnote 7 Alongside Bible, Talmud, and Midrash, we find “’Ilanoth”—Trees. Postel was well aware of the parchment “iconotexts”Footnote 8 of kabbalistic cosmology and regarded them as a genre in their own right. It is probably fair to say that the heyday of ’ilanot occurred in sixteenth-century Italy, including grand luxury parchments crafted in fine Renaissance style. Exquisite copies of one such “magnificent parchment” may be found today in libraries and private collections around the world.Footnote 9

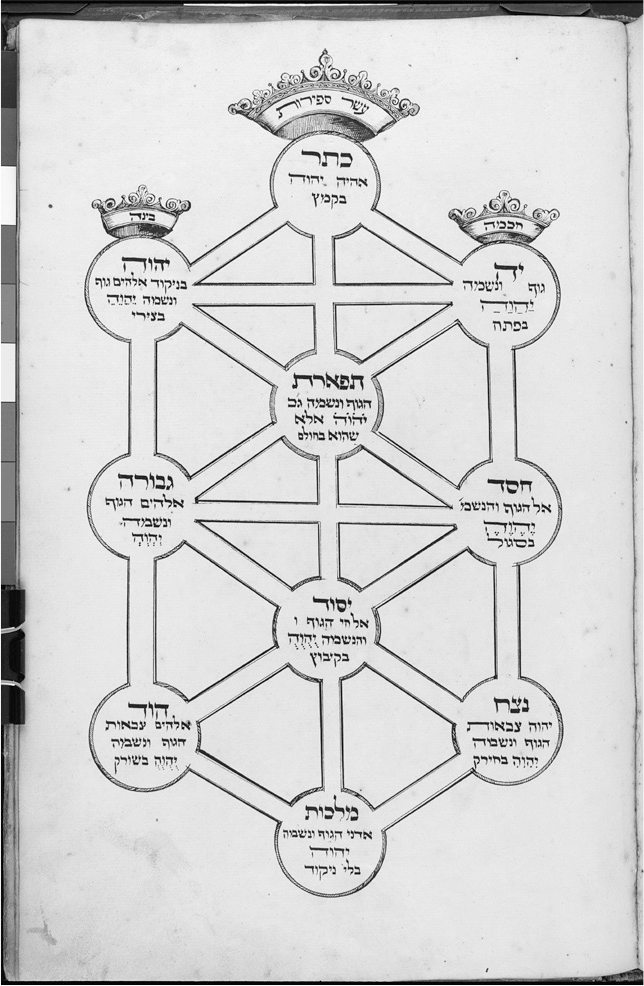

The rich variety of divinity maps reflects the particular epistemological, theological, and cultural orientations of their producers.Footnote 10 Variation notwithstanding, however, most kabbalistic divinity maps diagrammed the sefirot. Kabbalah refers to the diverse expressions of Jewish medieval esotericism that imaged God as ten hypostatic powers (the sefirot) susceptible to the influence—both positive and negative—of human action. These emanated ontologized divine qualities also determined the structure of the cosmos, top to bottom. Whether understood as facets of divine essence or as modes of divine action, the sefirot were presumed to be meaningfully arrayed and dynamically creative: their emergence, order, and interconnections provided the key not only to the Book of Scripture but also to the Book of Nature.Footnote 11

How did this work theologically? Kabbalists distinguished between two facets of the Godhead. The “true” God was conceptualized as infinite and even called “Nothing” (אין), and may be compared to—and was undoubtedly influenced by—Maimonidean apophatism.Footnote 12 Naturally this dimension is concealed and beyond apprehension, and certainly not the biblical character called “God.” The famous opening of the Zohar on Genesis thus reads “God” as the object of the first verse, and the Infinite as its hidden subject (Zohar I 15a). The revealed dimension of the Godhead emerges—or, more precisely, emanates—as the ten sefirot. The meaning of the term sefirot is anything but obvious. Its Hebrew root ס-פ-ר forms the basis for a range of words including book (ספר), story (סיפור), number (סִפרה,מספר), and even sapphire (ספיר). As we shall see, the Greek σφαῖρα is ostensibly a false, if not irrelevant, cognate.

That there were ten sefirot was axiomatic because of the emphatic pronouncement of Sefer yeṣirah (Book of Formation) on the subject: “Ten sefirot without substance (בלימה),Footnote 13 ten and not nine, ten and not eleven.”Footnote 14 A laconic cosmological work of late antique provenance resembling nothing else in Jewish literature, and canonical by the early tenth century, Sefer yeṣirah proclaimed in an apodictic tone that God carved out the cosmos with thirty-two wondrous paths of wisdom, these being the ten sefirot and the twenty-two letters of the Hebrew alphabet.Footnote 15 The latter were in turn divided into three groups of three, seven, and twelve. The early kabbalists took Sefer yeṣirah as a biblical-style base text, writing commentaries and citing it endlessly. Kabbalists found it a congenial matrix upon which to project their own speculative content.

The ascent of Sefer yeṣirah was certainly due to a perception of it as a scientific work in a cultural context that valorized the sciences—the Abbasid Caliphate of the ninth century—that Jews could call their own. The earliest commentary on the work, penned in the first half of the tenth century by Sa‘adiah Gaon, effectively conferred upon it canonical status and treated it as a Jewish work of science. For some two hundred years thereafter, this perception would be shared by all commentators on the work.Footnote 16 Its subsequent appropriation by kabbalists might best be seen as an outgrowth of this perception rather than as a dramatic about-face in its reception.Footnote 17

The ten sefirot of Sefer yeṣirah share little more than name and number with those developed in medieval theosophical Kabbalah, though in both cases they are understood as the fundamental elements of creation.Footnote 18 In the former, we find them identified as the six vectors of three-dimensional space, the two vectors (or endpoints) of time, and the two vectors of value (good and evil).Footnote 19 In the latter, the sefirot are the nodes of a emanatory network, ten qualities (perhaps not uncoincidentally paralleling Aristotle’s ten categories) of endless combinatory creative potential that articulate a denary Godhead. These sefirot, the contemplation of which constitutes the very heart of medieval theosophical Kabbalah, are named with attributes borrowed from 1 Chronicles 29:11: “Thine, O Lord, is the greatness, and the power, and the glory, and the victory, and the majesty.”

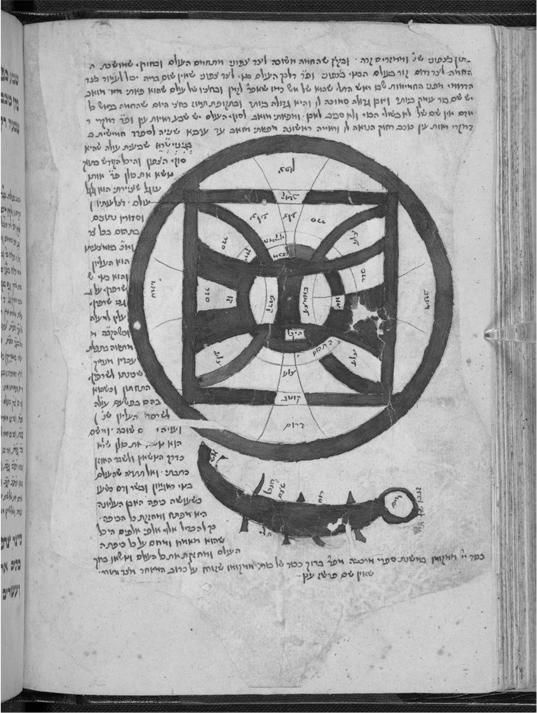

It may be observed that the ten sefirot of Sefer yeṣirah—space, time, and value—could be, and in fact were, diagrammed with relative ease with the common schemata of medieval natural philosophy.Footnote 20 A schema going back to Isidore of Seville’s revolutionary seventh-century treatise on the natural world—De natura rerum, known in the Middle Ages as “The Book of Wheels” (Liber rotarum)—seems closely related to the cosmological world of Sefer yeṣirah and indeed centers around the inscription “Mundus-Annus-Homo,” which quite literally appears in Sefer yeṣirah as “world year person” (עולם שנה נפש).Footnote 21 Isidore’s diagram may be found in the early kabbalistic commentary to Sefer yeṣirah ascribed to R. Sa‘adiah Gaon, and its long afterlife includes an appearance in a fascinating illustrated scientific primer of seventeenth-century Ashkenazic provenance entitled Ṣurat sidrey ‘olam (The Form of the Orders of the World) [Figure 1].Footnote 22

Figure 1: © British Library Board (British Library Add. MS 27089 81v); Polonsky Foundation Catalogue of Digitised Hebrew Manuscripts.

The ten sefirot of the theosophical Kabbalah are, by contrast, abstractions. None of them bears intrinsic markers of location in space, whether in two or three dimensions, nor even self-evident relationality to one another. Nevertheless, the earliest extant kabbalistic manuscripts, copied from Spanish sources in Rome in the 1280s,contain sefirotic diagrams, epistemic images “crafted expressly to accompany or even replace verbally transmitted explanations.”Footnote 23 Such images must be understood in their literary and cultural contexts rather than through any timeless taxonomy. The context of the literary emergence of the Kabbalah was twelfth-century Provence.Footnote 24 Kabbalah, no less than philosophy, was symptomatic of the profound local Jewish engagement in the mediation of Greco-Arabic learning to Christian Europe.Footnote 25 In this context, kabbalists and philosophers shared the estrangement from the mentalité of classical rabbinic thought that generated profound transvaluations of Jewish tradition.Footnote 26 The occasional antagonism and polemic, sometimes fierce, between those who identified with one camp or the other should be understood as bespeaking proximity/similarity rather than distance/difference.Footnote 27 As Hava Tirosh-Samuelson has shown, early Kabbalah may be understood as an expression of Platonic rather than Aristotelian science, the latter being associated with most medieval Jewish philosophers. Kabbalists held the Platonic view that

scientific knowledge pertains not to the natural world known through the senses but to the intelligible forms, the eternal, timeless, changeless realities that are arranged in a hierarchical order…. Properly speaking, only knowledge of the intelligible forms constitutes “science” (Timaeus 27d–28a), but such knowledge is the privilege of the gods and of a small number of their friends (Phaedrus 278d).Footnote 28

Evidently the kabbalists were among these friends of the gods, and their lore was the true science of the divine. In Hebrew, Kabbalah was often referred to as a science (חכמה)—or “scienza,” for example, in the Italian writings of kabbalist R. Eliyyà Menahem Ḥalfan, who himself fashioned a complex ’ilan.Footnote 29 Many learned Christians accepted and even promoted such an understanding, perhaps none more famously than Pico della Mirandola, who insisted in his Conclusiones, “Nulla est sciencia, que nos magis certificet de diuinitate Christi, quam magia et cabala” (There is no science that more greatly certifies the divinity of Christ than magic and Kabbalah).Footnote 30

I emphasize this point to set up my central argument here, namely that in visualizing the sefirot both conceptually and graphically, medieval kabbalists appropriated—not inappropriately!—the dominant schemata of what Barbara Obrist describes as the “two basic disciplines involved in elaborating models of the universe, astronomy and natural philosophy.”Footnote 31 Astronomy provided the nested concentric circle schema of the sefirot in evidence in a Parma manuscript dating to 1286.Footnote 32 Even more prevalent, however, are the arboreal diagrams associated with natural philosophy—so favored, in fact, that they ultimately gave rise to the metonymic appellation “tree” (אילן) for kabbalistic diagrams, regardless of the actual schema deployed.

Establishing the True Constellation of the Godhead

Roughly three hundred years after the literary emergence of Kabbalah, its classical period was crowned by the masterful survey Pardes rimmonim (Pomegranate Orchard), penned by the brilliant young kabbalist, R. Moses Cordovero.Footnote 33 Cordovero’s Pardes, completed in 1548, is an opinionated survey, an inventory with an attitude, but it is no less a valiant work of cultural preservation undertaken by a man whose very name proclaims his Cordovan origins and Iberian refugee status.Footnote 34 Cordovero’s ambitious aspiration to collate the entirety of kabbalistic speculation in the aftermath of historical rupture and displacement bears a striking resemblance to the project of the Beyt Yosef (House of Joseph), the comprehensive and critical survey of Jewish law composed by R. Joseph Karo, Cordovero’s contemporary and neighbor in the Upper Galilean town of Safed in the mid-sixteenth century.Footnote 35 As part of his summa, Cordovero included a critical inventory of sefirotic iconography that will serve to structure and generate much of the following discussion. Cordovero’s work was hardly the first to survey the various opinions regarding the correct visualization of the sefirot, but was of unequaled brilliance, breadth, and influence.Footnote 36

The first five sections or “gates” of the Pardes are devoted to theological and polemical considerations pertaining to the sefirot. With “Gate Six: The Order of Their Array,”Footnote 37 Cordovero turns his attention to the graphical visualization of their structure, opening the first of eight chapters devoted to the subject with the following passage: “Chapter One: treating the forms (צורות) of the sefirot, regarding the order of their array (סדר עמידתן—the title of this “gate” of the Pardes): the opinions are manifold. And the kabbalists have drawn forms for themselves on parchments (יריעות) and called them ‘tree’ (אילן).”Footnote 38 There is no timeless taxonomy for the nonfigural schematic representations of concepts, and indeed a primary task of the historian of these sources is to be attentive to their specific iconographical terminology, while being self-aware with regard to the implicit claims made by the language we use—for example “diagrams” or “drawings”— in our own interrogations.Footnote 39 Thus the passage adduced at the opening of the present essay used the term ṣiyyurim (ציורים), in that context meaning “drawings,” to refer both to mental images (Denkbilder) and to the material images (Abbilder) to be fashioned by the adept. The Hebrew root צ-י-ר was used in classical rabbinic sources almost exclusively in the latter, material—and even specifically diagrammatic—sense, but came in medieval philosophical sources to mean primarily the former, conceptual sense.Footnote 40 Here, Cordovero uses the term ṣurah (צורה), used commonly in medieval Jewish philosophy for “form”—in both Platonic and Aristotelian senses. By Cordovero’s time it was commonly used by kabbalists to refer to cosmological—and specifically sefirotic—drawings.Footnote 41 As in the opening passage, here too we find the identical term deployed for mental and material images.

Cordovero tells us that by the “forms” of the sefirot he means their visualized configuration, their array—literally, “the order of their standing” (סדר עמידתן). In medieval philosophical Hebrew, “standing” (עמידה) was a term for existence or reality, but Cordovero evokes the usage found in astronomical treatises, where forms of the Hebrew root are used in the sense of “position,” specifically the positions of the planets.Footnote 42 The unselfconscious use of astronomical terminology in presentations of kabbalistic theosophy is in evidence in another frequent usage to describe the sefirotic array current from the late thirteenth century: “constellation” (מערכת), as in the foundational work Ma‘areḵet ha’elohut (Constellation of the Godhead), composed in late thirteenth or early fourteenth-century Spain.Footnote 43 Sefirotic constellations (מערכות) are equated with ’ilanot in a telling passage from Cordovero’s commentary on the Zohar that reveals the profoundly cosmological-ontological character of its kabbalistic appropriation:

With regard to the reality of the sequence of levels (השתלשלות המדרגות) from above to below, they are without end, and they are stations (מחנות), constellations opposite constellations (מערכות מול מערכות), and the constellations emerge in sequence one from another, and each and every constellation will now be called “tree” (אילן). And I have already explained that the constellation of ’Aṣilut (Emanation—the highest of the four “worlds”) is the ’ilan of ’Aṣilut, and no (demonic) shell will rule it whatsoever. After it, the constellation of the ’ilan of Briyah (Creation—the second of the four worlds), this constellation being a shell and garment to ’Aṣilut.Footnote 44

’Ilan, the very same term that Cordovero has singled out as denominating the inscription of an arboreal diagram on parchment, is here linguistically—and ontologically— assimilated into his astronomically inflected summary of the emanatory process.Footnote 45 The term ma‘areḵet (מערכת) refers in medieval Hebrew sources specifically to the order and array (recalling the title of the section of the Pardes under consideration) of a group of stars, otherwise known as a mazzal (מזל).Footnote 46 The term maḥaneh (מחנה) refers to a so-called “lunar mansion/station/house,” being one of the twenty-eight segments of the ecliptic used to track the movement of the moon relative to the “fixed stars.”Footnote 47 I stress the unselfconscious usage of this astronomical terminology because from the perspective of discursive analysis, it is, in fact, much more significant than intentional borrowings as an indicator of profound implication; it is how they speak rather than what they speak about.

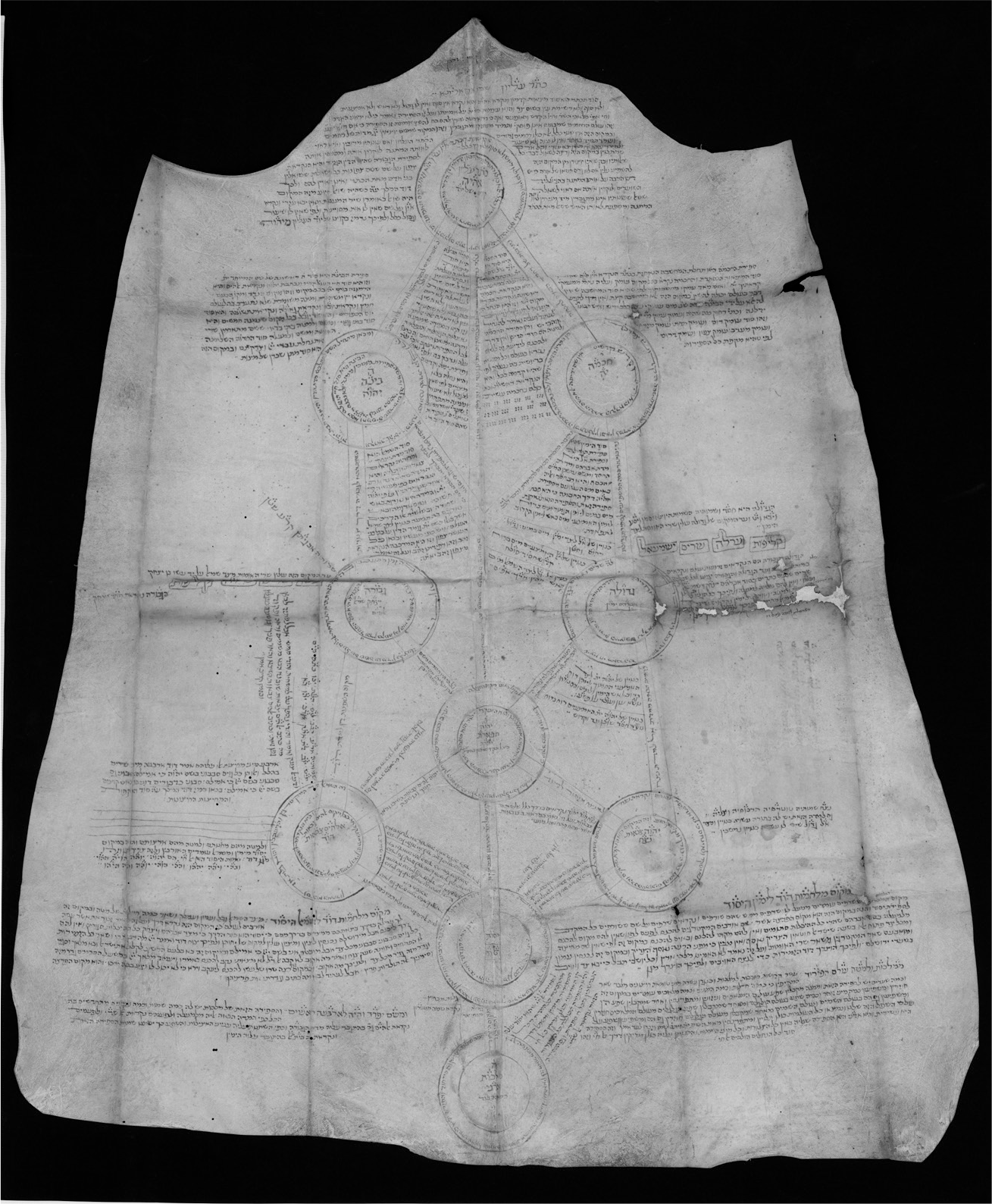

If the arboreal schema is a constellation, parchment is the sky. Cordovero’s opening definition of an ’ilan places equal emphasis upon its medium, a yeri‘ah (יריעה). The term immediately recalls Psalms 104:2, “who stretchest out the heavens like a curtain,” a biblical verse ubiquitous in kabbalistic sources, as well as a famous dictum of R. Yohanan ben Zakkai, “If all the heavens were parchment (יריעות), and all the trees (אילנות) pens, and all the seas ink, it would be insufficient to write the wisdom I learned from my teachers.”Footnote 48 If the term yeri‘ah in the opening passage is primarily an indicator of material, by Cordovero’s time it was the long-standing metonym used to refer to a large-format inscribed sefirotic diagram.Footnote 49 A number of such single-sheet parchments dating to the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, including artifacts that appear to be of Italian, Byzantine, and pre-expulsion Spanish provenance, have reached us [Figure 2].Footnote 50 These were certainly what Cordovero had in mind when he wrote that the kabbalists call the inscription of the forms of the sefirot on a parchment sheet an ’ilan, an arbor.Footnote 51

Figure 2: Vatican City, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, MS Vat. ebr. 530 III. Reproduced with permission from Dr. Delio Proverbio, Curator of Oriental Manuscripts, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana.

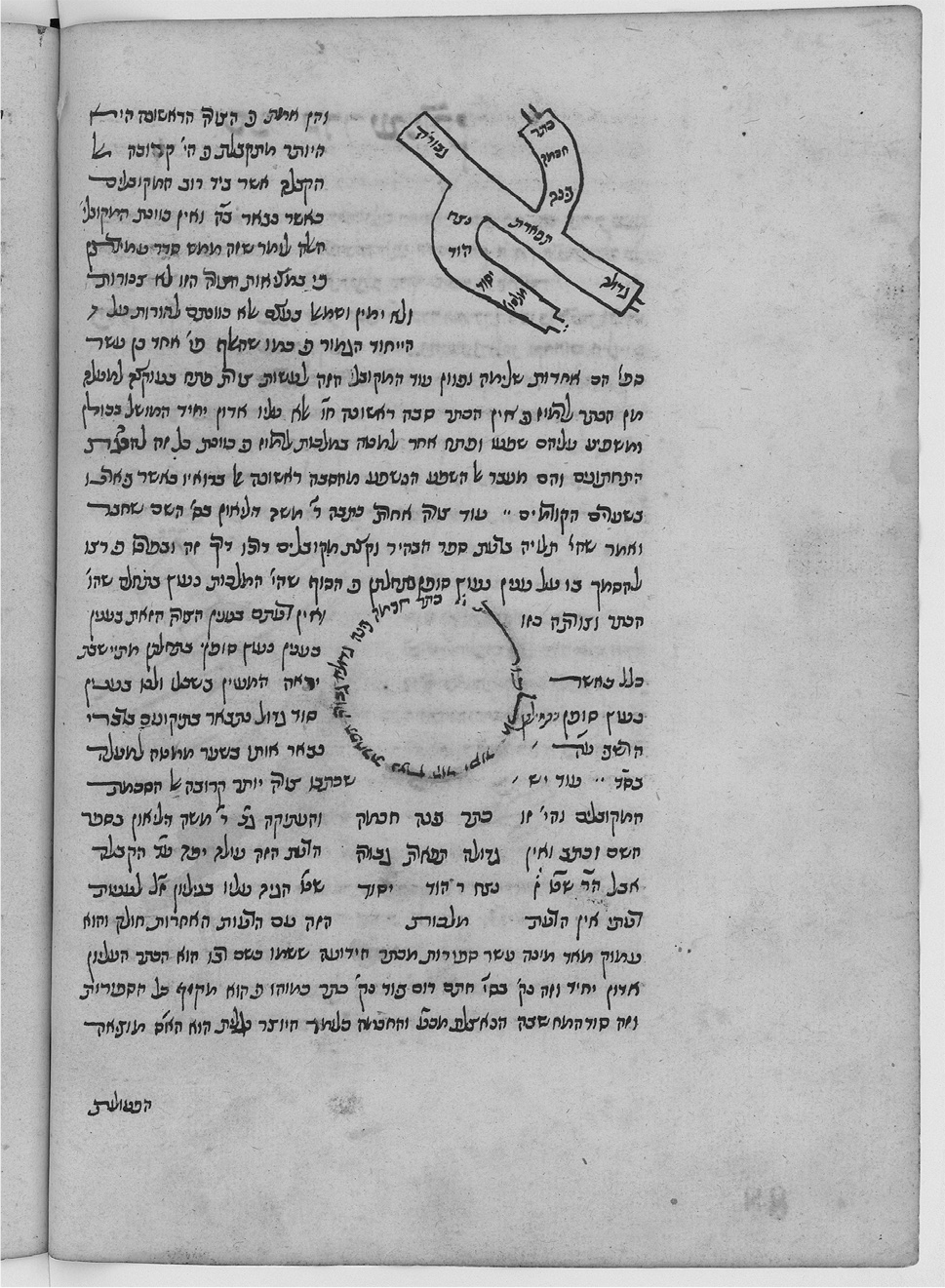

The first diagrammatic treatment of the sefirot considered by Cordovero visualizes their array in the form of an alef (א), the first of the 22 Hebrew letters. “There were those who wanted to draw them in the form of an alef,” he begins [Figure 3].Footnote 52 Cordovero explains this configuration as having the shape of the first Hebrew letter, which consists of three components; three sefirot are embedded in each. The alef diagram in an early Pardes manuscript is in keeping with the verbal description, though not limited by it.Footnote 53 In addition to displaying the names of the sefirot in their locations, the diagram adds fingers and toes of uniform length to the crossbar and foot of the letter. The protrusion extending between the legs of the alef is labelled Malḵut (Kingdom), the last and exclusively receptive sefirah, and hangs beneath Yesod (Foundation), the latter normally the Kabbalah’s great phallic symbol. Thanks to these anthropomorphic elaborations, the diagram better exemplifies the principle that Cordovero regards as implicit in this visualization: “Their intention was to write the forms of the Supernal Adam in the form of alef to suggest that despite its divisions it is entirely one whole unity.”Footnote 54 These same visual elements, to which there is no reference in Cordovero’s text, also evoke the axiomatic dictum of Sefer yeṣirah, according to which the sefirot are arrayed like fulcra and scales in two opposing sets of five, like fingers and toes.Footnote 55

Figure 3: Vatican City, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, MS Neofiti 28, 88r. Reproduced with permission from Dr. Delio Proverbio, Curator of Oriental Manuscripts, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana.

Significantly, Cordovero emphasizes that although the image communicates the important concept of divine unity-despite-plurality, it should not be taken as an accurate representation of the real structure of the divine realm.Footnote 56 Twice Cordovero writes that the drawing should not be taken as “real”—he uses the term mamaš (ממש)—and that the kabbalists did not mean to imply that the structure of the Godhead was captured by the form of this letter: “It is not the intention of these kabbalists to say that this is the real (ממש) secret of their existence, because in reality (במציאות) this form has no channels (צינורות) and no right or left.”Footnote 57 The ’ilan must resemble its referent; in Peircean terms, Cordovero insists that the ’ilan is an iconic rather than symbolic sign; it “physically” resembles and is not merely customarily associated with that which it signifies.Footnote 58 For Cordovero, only the exceptional kabbalistic diagram is “merely” a symbol that does not provide visual representation of the topography of the Godhead.

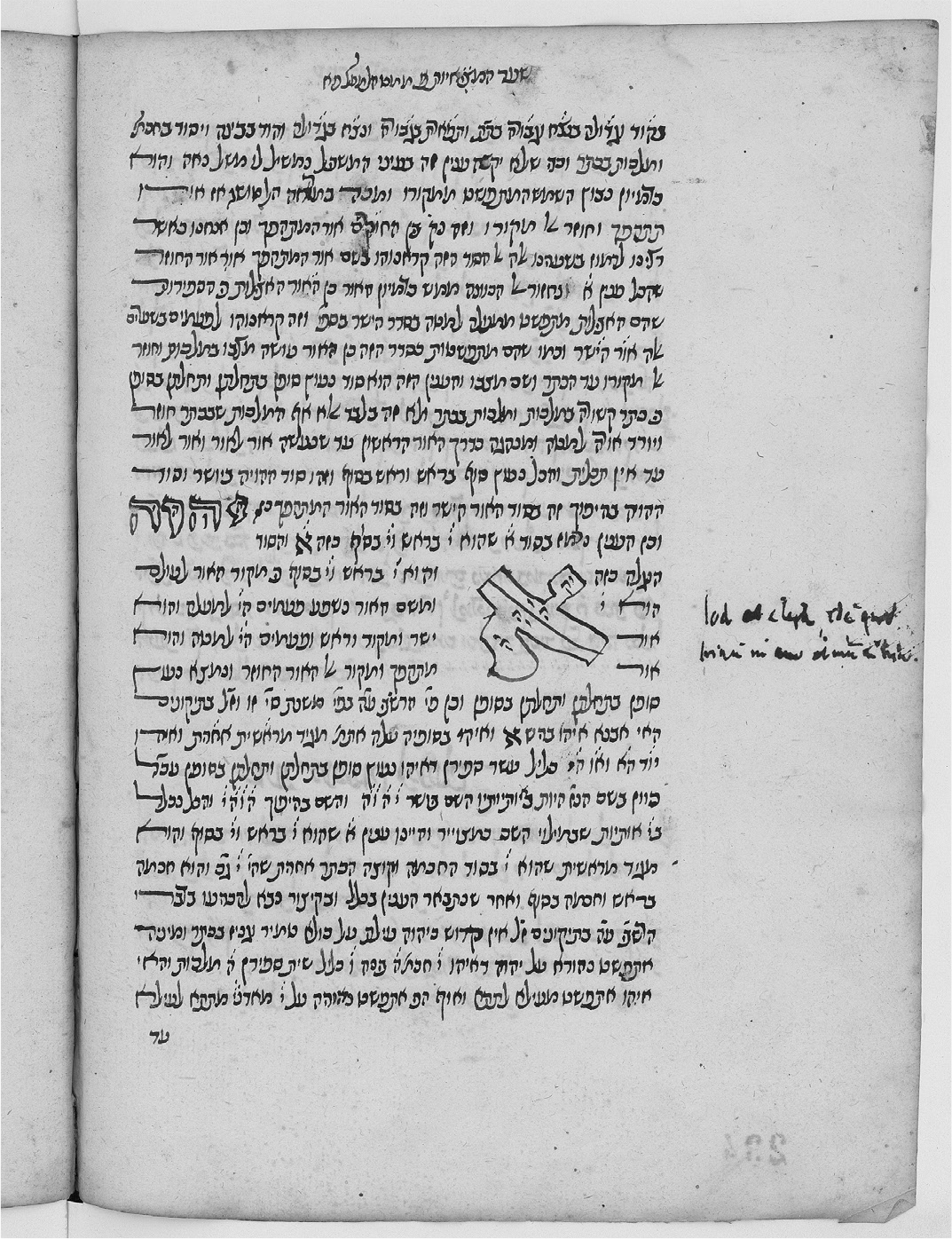

Cordovero follows this with a consideration of a second form, which he hastily and rather disdainfully rejects, despite its impressive pedigree [Figure 4].Footnote 59 This form is meant to convey another characteristic of the sefirot, again based on a passage in Sefer yeṣirah: “Their end is fixed in their beginning.”Footnote 60 Cordovero’s dismissal of the visualization of this principle as a circle, with the names of the sefirot arrayed like the hours on a clock, was absolute, his disdain an expression of his conviction that a profound categorical error had been made. The characteristic of the sefirot expressed in the passage of Sefer yeṣirah, he would explain elsewhere, refers not to structure but to process.Footnote 61 The sefirot are not arrayed in a circle, but emanate in a sequence that ultimately reflects back upon itself, in Cordovero’s metaphor, “like sunlight off a mirror.”Footnote 62 This “is called reflected light (אור המתהפך) by scientists (חוקרים),” he tells his reader—not missing an opportunity to link Kabbalah and science, in this case, optics. Ultimately, this principle is possible to visualize symbolically—which is precisely what he does in “Gate 14” [Figure 5]—but heaven forfend that symbolic and iconic representations of the sefirot be confused! Cordovero’s condemnation of this representation was so strong that the publisher of the first edition, who took the diagrams of the Pardes very seriously, deemed it reasonable to omit, thus saving himself a small typesetting headache. In its place, we find in parenthesis, “Said the typesetter (מגיה), the reader (המעיין) should draw (יצייר) ten sefirot in one circle and find that the beginning of the circle is Keter and the end of the circle Malḵut beside Keter.” It suffices for the reader to picture this (faulty) image in his mind’s eye.

Figure 4: Vatican City, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, MS Neofiti 28 88v. Reproduced with permission from Dr. Delio Proverbio, Curator of Oriental Manuscripts, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana.

Figure 5: Vatican City, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, MS Vat Neofiti 28 234v. Reproduced with permission from Dr. Delio Proverbio, Curator of Oriental Manuscripts, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana.

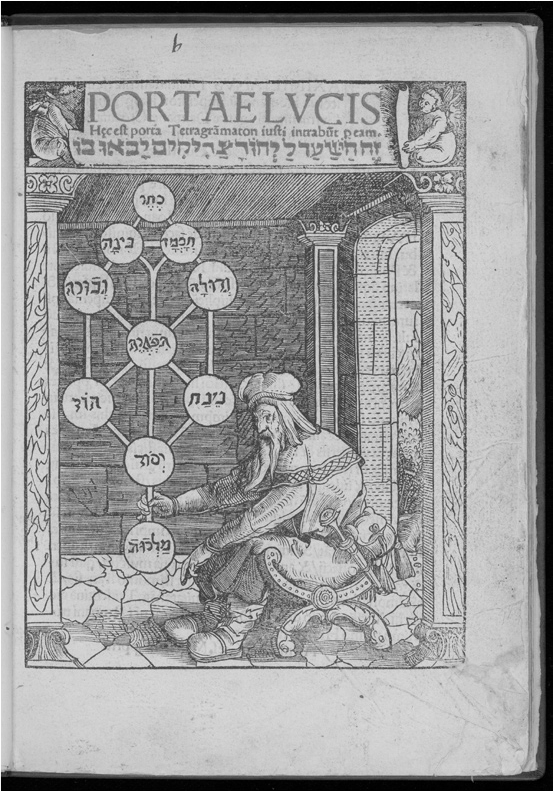

With assurances that he will ultimately provide the true explanation of this principle, Cordovero quickly proceeds to his third “form”—this time one “close to consensus amongst kabbalists.” This boxy array, he notes, was copied by the thirteenth-century Castilian kabbalist R. Moshe de Leon, despite the latter’s critique of its accuracy. The form favored by Cordovero and, he states, all kabbalists is one familiar to many today from the oft-reproduced wood-cut title-page of Paulus Ricius’ Portae Lucis (Augsberg, 1516), the Latin translation of the thirteenth-century Castilian R. Joseph Gikatilla’s Ša‘arey ’Orah [Figure 6].Footnote 63 In addition to de Leon, the great Spanish refugee kabbalist R. Judah Ḥayyat favored it, the latter coining the descriptive “segolta segol segol” to capture its form by referencing the names of particular paratextual symbols used for the cantillation and vocalization of the Torah, something like a three-pointed delta followed by two three-pointed nablas.Footnote 64 The points are as significant here as the triangle and inverted triangle shapes, as each corresponds precisely to one of the sefirot. Moreover, this particular configuration accurately represents the relative positions and relations between the sefirot, above and below as well as right, left, and center.

Figure 6: Portae Lucis frontispiece, Courtesy of the Embassy of the Free Mind, Bibliotheca Philosophica Hermetica Collection.

Cordovero has at this stage established what he deems to be the correct configuration of the sefirot, though his work is far from complete. At the time of his writing, various alternative visualizations—variations really—some with illustrious pedigrees, were in use.Footnote 65 One such variation aligned the first three sefirot centrally rather than triangulating them. The right and left of the triangular configuration, it was argued, could hardly apply to these most sublime nodes of the divine. Endorsed by the late thirteenth-century kabbalist R. Isaac of Acre in his Me’irat ‘eynayim, this schema may be seen in the greatest of all ’ilanot produced in the decades preceding Cordovero’s activity [Figure 7].

Figure 7: Oxford - Bodleian Library MS Hunt. Add. D (Neubauer 1949). Reproduced with permission from The Bodleian Libraries, The University of Oxford.

In this “Magnificent Parchment,” the tree—as a kind of kabbalistic empyrean—rises above the Throne of Glory, which itself hovers above a detailed and richly illuminated cosmograph of the spheres.Footnote 66 This schema, popular in Italy at the time, was not Cordovero’s preferred form, but neither did he find it overly objectionable. He reserves his invective for a configuration that had been endorsed by no few authorities in which the sefirot typically on the right were placed on the left, and vice versa.Footnote 67 This reversed configuration had been endorsed by R. Isaac as well as nothing less than the “true configuration” (העמדתן הנכונה האמיתית).Footnote 68

The discussion of this disturbing variation—disturbing especially given the loaded symbolic connotations of left and right—also highlighted the more general theological difficulties inherent in Cordovero’s critical review. On the one hand, its stated goal was to establish the “true” configuration of the Godhead, with every sefirah in its right place: right, left, center, up, and down. On the other, such a spatial discourse effectively materialized the Godhead. Assertions that this language was metaphorical have an air of apologetic desperation: right and left refer to qualities rather than sides, up and down to causal relationships rather than to relative altitude. The reversal also provoked reflection on the salient question of perspective: whose point of view is implied in the sefirotic tree? Is the “right” column God’s right, or our right, i.e., heraldic left? Are we facing God or adopting God’s view? Cordovero, emphatically rejecting the reversal, argues that the human form is more shadow than mirror of the divine form, and that shadows do not reverse right and left. He also compares the sefirot to the stone Tablets of the Covenant that were engraved straight through, front to back, but which nevertheless read the same way from either side. The Tablets were, in his extraordinary phrase, “one of the supernal branches of materialized spirituality” in which “there is no right and no left but everything is right and everything is left.”Footnote 69 In his kabbalistic prayer book, Cordovero offers something of a compromise: in general, the kabbalist is in a state of identification with the divine, making the right of the kabbalist the right of the divine, and the left, the left. At moments of dissociation, however, the divine becomes other, and the kabbalist’s view shifts accordingly. Now the right of the kabbalist is God’s left, and the left, the right.Footnote 70

Having established the true “form of the standing of the pure and holy emanation” (צורת עמידת האצילות הטהור והקדוש), in his third sub-chapter Cordovero broadly theorizes his discussion so as better to surmount its theological liabilities. “With regard to this form,” he asks, “what is its essence and its function, and what is intended in its drawing (מה מהותה וענינה ומה הכוונה בציורה)?”Footnote 71 Elaborating on the (apologetic) note just sounded, Cordovero reiterates that the schema, which he has insisted must reflect the array of the sefirot “in reality,” is to be understood in causal rather than in spatial terms. The philosophical key that enables this substitution is remarkably simple: every cause encompasses its effect. This medieval philosophical commonplace, found in Proclus, catapults the discussion, albeit ironically, to (outer) space.

The point of the earth is in the middle of the firmament, and the firmament surrounds the earth, and the firmament is the cause of all things under heaven according to the divine will, as is well-known among scientists, (e.g.,) that the movement of the spheres (גלגלים) is the cause of the compounding of the elements.Footnote 72

To understand the sefirot, one must understand the spheres. Perhaps unexpected to some readers, the elision of the sefirot and the spheres in Cordovero’s discussion was all but inevitable in light of the common medieval understanding of the latter. Maimonides, invoked here by Cordovero, like Aristotle before him, understood the heavenly bodies to be sentient: “All the stars and spheres possess a soul, knowledge, and intellect. They are alive and stand in recognition of the One who spoke and [thus brought] the world into being.”Footnote 73 Lest one object that the polarity-driven attraction of the sefirot made them ill-suited for harmonization with the heavenly bodies, we recall that for Aristotle, it was desire (for the Prime Mover) that set the spheres in motion.Footnote 74 Of course Cordovero’s point was not to conflate spheres and sefirot, but to assert that the resemblance of their visualizations was the result of shared forms of relationality.

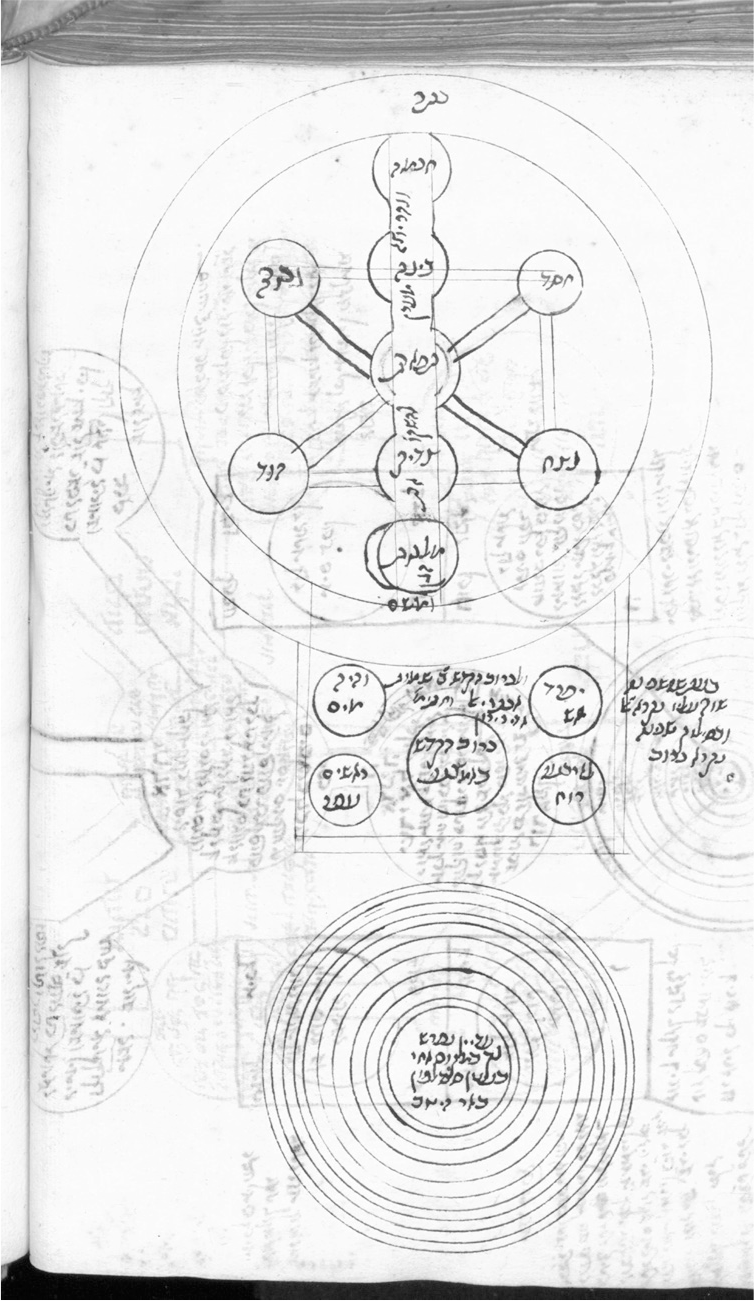

In the tradition of Spanish philosophical kabbalists before him, Cordovero was also interested in the correspondences, equations, and relations between the sefirot and other pre-kabbalistic cosmological models.Footnote 75 A diagram in a Me’irat ‘eynayim manuscript copied in Italy in 1552 provides visual testimony of this approach [Figure 8].Footnote 76

Figure 8: © British Library Board (British Library Add MS 27172, 123v); Polonsky Foundation Catalogue of Digitised Hebrew Manuscripts.

In this diagram, we find ten geocentric spheres inscribed so as to establish correlations between them and the ten sefirot (as well as to the Ten Commandments, the ten creative speech-acts of Genesis 1, and ten key body parts). The fact that the schema deployed was a geocentric rota of the universe is telling. The same correspondences could, after all, have been shown clearly by using a simple table. By inscribing the terms in this specific geometric idiom, however, an implicit argument was being advanced.Footnote 77 It is worth noting that although the inscription “earth” is found at the center of this rota, the central column rising above it is, in fact, devoted to the sefirot. The astronomical spheres, inscribed on the “ten o’clock” diagonal, merely echo them.

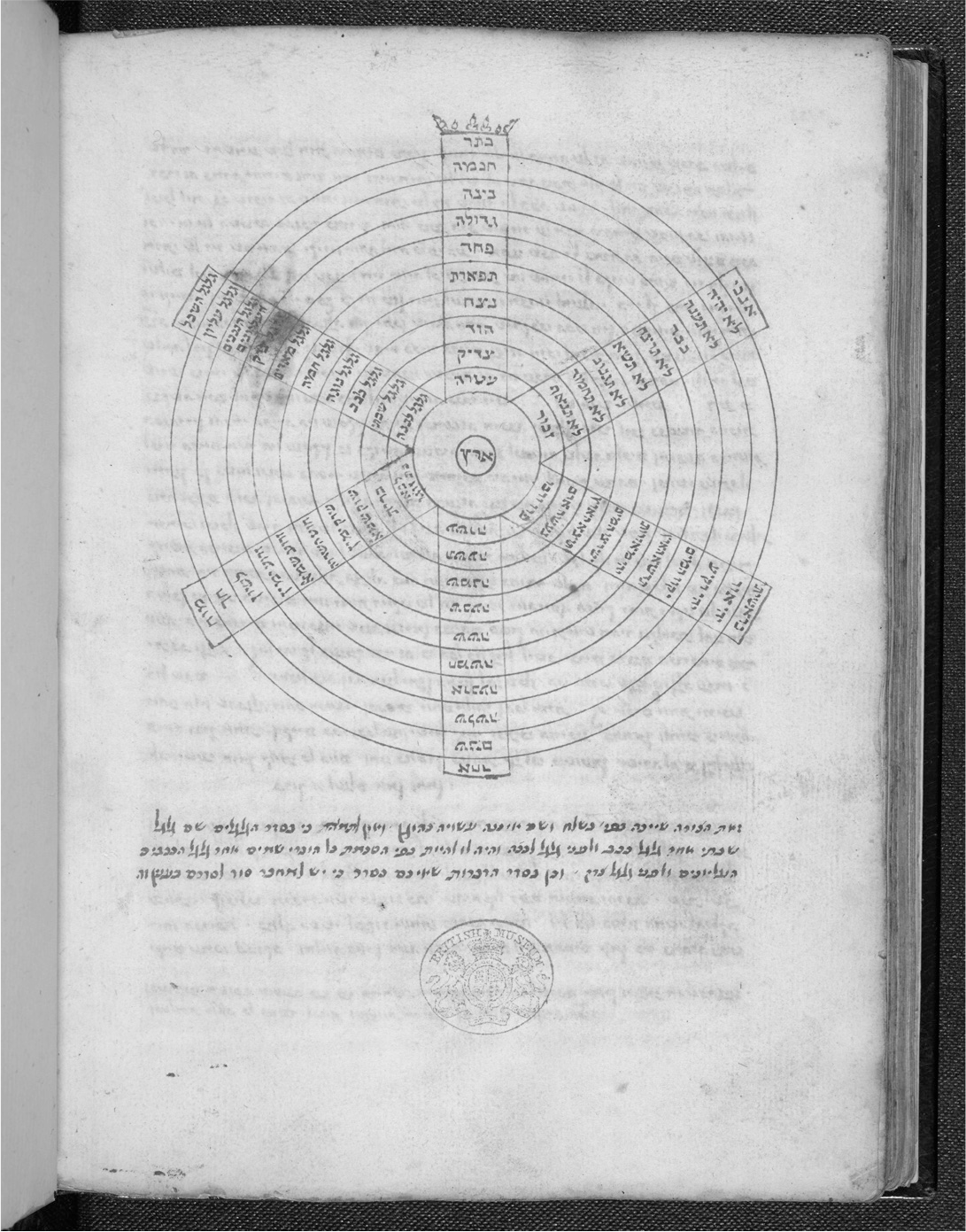

A more direct diagrammatic correlation between the spheres and the sefirot may be found in manuscript copies of the 1370 work Mešoḇeḇ netiḇot, written by R. Samuel ibn Matut in Guadalajara, Spain. In this commentary on Sefer yeṣirah, copied repeatedly in sixteenth-century Italy, the author harmonized Greco-Arabic philosophy and Kabbalah. In a section describing the divine flux and its transmission through the sefirot, ibn Matut includes a striking diagram, introduced with the following passage: “And the archetype (דוגמה)Footnote 78 of these are the prophetic as well as the astronomical (תיכוניות) sefirot, which are the orbs (גלגלים) that we see, namely nine orbs and the lower world and all that is within them” (Cod. Parma MS 3489, 102a). The accompanying diagram on the verso [Figure 9] presents ten concentric circles that demarcate nine bands surrounding the center circle, labelled “land” (ארץ) and “lower world.” The nine bands are not inscribed with planetary names, but with the names of the ten sefirot, the tenth, Keter, placed just beyond the circles. Note the configuration of the first three sefirot as a pillar. What is truly noteworthy for our purposes, however, is the mirroring of the entire superimposed arboreal inscription in the bottom half of the diagram, as often found in astronomical figures. This mirroring emphasizes the sphericity and symmetry of the system.

Figure 9: Biblioteca Palatina, Cod. Parma MS 3489, 102v, under concession by the Ministry for Cultural Heritage and Activities.

Gershom Scholem famously insisted that “the term sefirah is not connected with the Greek ‘sphere,’ but as early as the Sefer ha-bahir it is related to the Hebrew sappir (‘sapphire’), for it is the radiance of God which is like that of the sapphire.”Footnote 79 Even if Scholem’s etymology is correct, the astronomical association is not so easily avoided—as the spheres were understood to be made of the transparent crystalline substance known as sapphire.Footnote 80 This sense is evident in a derivation suggested by Cordovero later in the Pardes: The sefirot are a power (כוח) that contains many opposites, “which is the reason they are called sefirot—from the term sapphire. For just as the sapphire has no distinguishing color but contains all the colors seen in it, so the sefirah contains all the opposites” (Pardes 8:2).Footnote 81 This derivation was hardly Cordovero’s innovation. The great Spanish kabbalist R. Abraham ben Eliezer ha-Levi (c.1460–c.1530), who wandered for over a decade following the expulsion before settling in Jerusalem, wrote regarding the nature of the sefirot and the derivation of their name: “Those sefirot that we have discussed are His attributes (מדותיו ית׳) by which the world operates and are fine, pure, crystalline ((ספיריות spiritual forms (צורות רוחניות)…. And in general all ten sefirot are fine and simple and crystalline, this being the reason they are called sefirot.”Footnote 82 Such a derivation had also been suggested by the foundational Ma‘areḵet, in which “pavement of sapphire stone” (לבנת הספיר, Exodus 24:10) is given as a possible source of the term.Footnote 83 Even the “Magnificent Parchment,” to which I have already made mention more than once, prefaces its incomparable divinity map with the following text:

The intention of our sages of blessed memory was to speak of hidden things by means of the sefirot—whether the term refers to number (מספר), to story (סיפור), or to the sapphire (ספיר) apprehended by the elders of Israel [referring to Exodus 24:10]…. Just as the sapphire that has no color but shines and receives all colors one after another, so are all things emanated from the Creator, may He be blessed. Therefore it is plausible to say that [the term] sefirot is derived from the term (מלשון) sapphire.Footnote 84

Crystalline sapphire, crystalline spheres, crystalline sefirot: Scholem, ever inclined to oppose Kabbalah and philosophy, seems to have been uninterested in unpacking the conviction of the kabbalists that the sefirot and the spheres were analogous, if not continuous.

This indeed is Cordovero’s point: The nested structure of the cosmos, from earth to infinity, is a function of the causal dependence of each onion-like orb on the one surrounding it. As he surveys this great chain, Cordovero weighs in on questions that were of great interest to medieval philosopher-scientists: how did Greek and biblical cosmological terms correspond, “heavens” (שמים) and “firmament” (רקיע) with the planetary spheres and the orb of fixed stars?Footnote 85 Cordovero argues that the seven firmaments in ancient Jewish sources are not to be identified with the planetary spheres, here designated by the commonly used Hebrew term for the celestial orbs (גלגלים).Footnote 86 The firmaments are of an entirely different order. Moreover, the spheres (whatever their precise number, which was also contested) were all located within one firmament, the lowest of the seven. This discussion allows Cordovero to set forth a fully articulated statement of a chain of being extending from the Infinite (אין סוף), through the sefirot, the firmaments, and the spheres, to the very core of the earth. Cordovero approvingly cites a zoharic passage according to which “the firmaments encompass the world and the spheres (גלגלים) and everything … and so too in this manner is the matter of the sefirot, for they are all within the Infinite (אין סוף) King of Kings, and within Keter is Ḥoḵmah, and within Ḥoḵmah is Binah” (36a). All ten sefirot are named, nested one in another, to the tenth, Malḵut. If the discussion so far has implied an analogous relationship between astronomical and sefirot structure, at this point Cordovero continues:

Within Malḵut is [the World of] Beriyah (Creation, the second of the four worlds), within Beriyah Yeṣirah (Formation, the third of the four worlds), within Yeṣirah ‘Asiyah (Action, the last of the four worlds). And within them are included Ma‘aseh Berešit (Work of Creation, i.e., cosmogony) and Ma‘aseh Merkaḇah (Work of the Chariot, i.e., cosmology)…. And within Ma‘aseh Berešit are the spheres (גלגלים), and within the spheres the earth, and within the earth, at its navel, the seven earths.

After adducing a long zoharic passage, Cordovero concludes,

It is therefore demonstrated by this passage that in the navel of the earth there are seven earths, one within another, in the manner of the spheres, and in this way we ascend from the point of the earth to the first cause, the ’Eyn Sof, and all that is within it. With this, we will be able to understand that which they said, “He is the place of the world and the world is not His place.”Footnote 87

It is not only that the chain of being is continuous and uninterrupted, but that the entire chain shares a common structural principle, or “seal” as Cordovero calls it elsewhere.Footnote 88 And lest he be accused of corporealizing the divine, he reminds his reader of the rabbinic dictum that God is the place of the world—which is to say that God created space itself.Footnote 89 Moreover, he writes, scientists agree that beyond the ninth sphere there is no space, the tenth Intellective Sphere being the placeless ground of space.

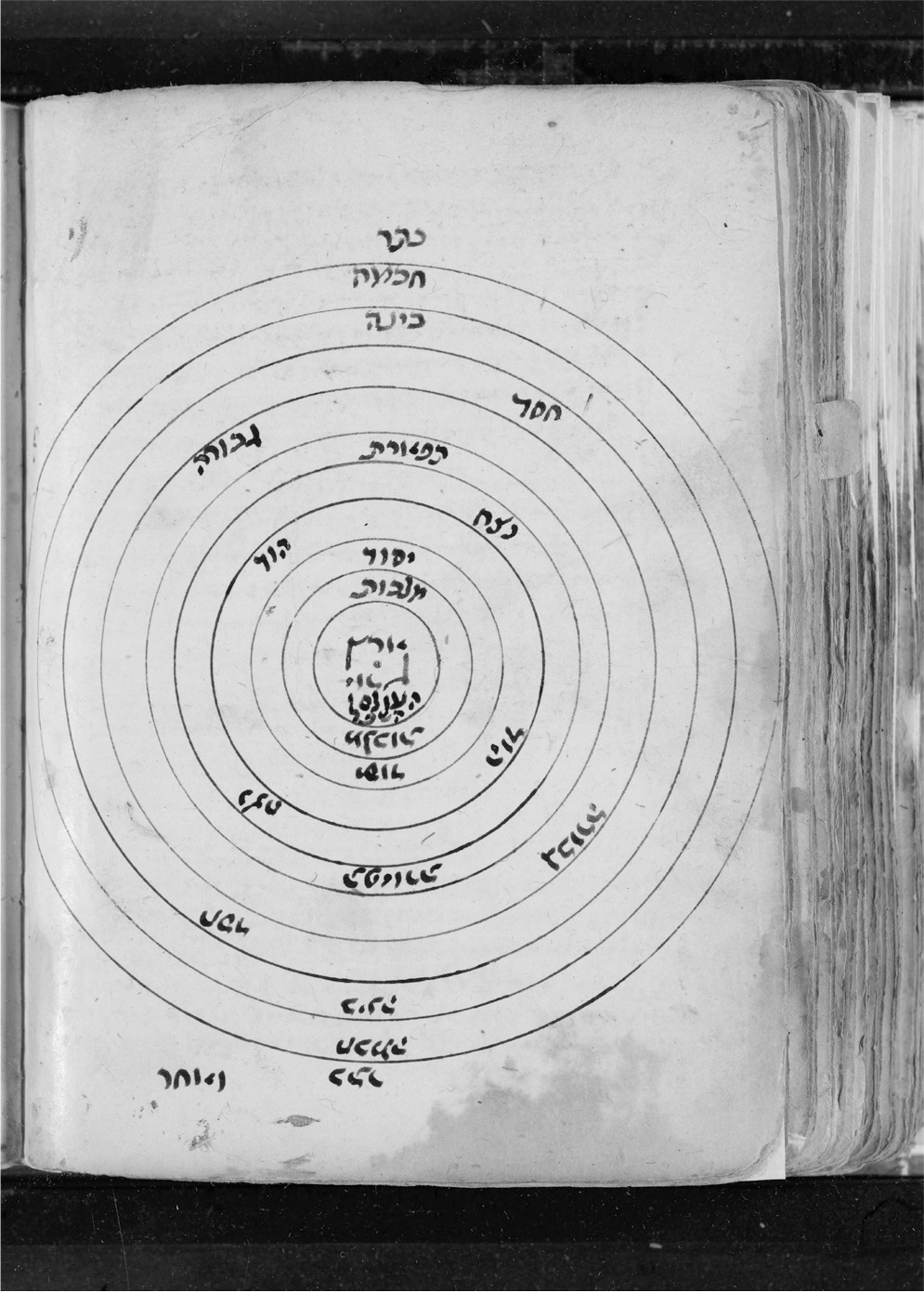

At this point, Cordovero introduces the last sefirotic diagram of the sixth gate, a venerable one found already in the 1284 Parma manuscript [Figure 10]. This diagram represents the structure of the sefirot in the form of an astronomical rota, though with a twist: each is figured by the first letter of its name, with the outmost circle of Keter implied by the letter kaf, and so on, to the innermost mem of Malḵut. This diagram would be reproduced in myriad contexts over the course of nearly nine centuries, with only minor variations such as the substitution of the centered mem with an ‘ayin for ‘Aṭarah, one of the appellations of the same sefirah. The nesting structure is described here as resembling the layers of an onion, a simile with a long astronomical pedigree.Footnote 90 Not long after Cordovero, R. Ḥayyim Vital would make the astronomical association explicit in his own discussions of the sefirot, writing that they were nested within one another “as the skins of onions, one within another, in the manner of the image of the spheres (תמונת הגלגלים) of astronomical books (בספרי תוכניים).”Footnote 91 Cordovero adduces the diagram in the name of R. Isaac of Acre, who had used it in his Me’irat ‘eynayim to articulate the concept of cosmic continuity, from the first emanated sefirah to the lowest rung of earthly creation.Footnote 92 The kaf of the first and outermost sefirah of Keter is “home to them all,” recalling the Hebrew letter bet with which the Torah begins, and which the ancient rabbinic sages regarded as a homograph for home (בית) to creation. Despite his valiant efforts to offer a de-spatialized reading of this diagram, Cordovero was unable to avoid the structural analogy, and reminds his reader that “we have learned that the matter of emanation (אצילות) resembles the spheres surrounding this world, one within another like onion layers, called firmaments, and that their operation (הנהגתם) resembles the operation of the lower firmaments. They are spheres encompassing (והם גלגלים מקיפים) everything within them.”Footnote 93

Figure 10: Biblioteca Palatina, Cod. Parma MS 2784, 43v under concession by the Ministry for Cultural Heritage and Activities.

Cordovero’s seventh gate shifts the focus from the sefirotic hubs and their array to the channels that connect them. Visualization is still central to the presentation, but this time without the need to survey a range of opinions regarding configuration. The theoretical question is now one of process: how do these hubs “communicate” with each other? The theoretical answer rests upon the principle of sympathies, namely that similarity establishes connectivity.Footnote 94 Were the sefirot simple, distinct essences, they would be unable to establish the network through which pulses the divine flux, or šefa‘, en route to its diverse manifestations. Invoking an axiom of early Kabbalah, Cordovero explains that each sefirah contains them all. When similar aspects of different sefirot are aligned, a channel between them becomes operative.Footnote 95 But knowing the theory isn’t enough: “There are so many variations (חלוקות) that it is impossible for one to grasp them (לעמוד בהם) without the material drawing (ציור הגשמי) that we will draw before you: ten circles, and in each and every circle, ten facets (פנים) that are ten aspects (בחינות), the ten sefirot in each of the ten sefirot. And the facet [of one] will revolve opposite the facet [of another].”Footnote 96

Cordovero’s language is worth noting here, using “material drawing” to emphasize that this visualization is not (merely) in the mind’s eye, but a drawn diagram—and one with moving parts [Figure 11]. In such a diagram, each sefirotic hub anchors a revolving disc upon which, like the numbers on a clock, the names of all ten sefirot are inscribed. Beside these lines, in the margins of MS Vat. Neof. 28 (27v), Athanasius Kircher wrote “10 Rotae,” clarifying the meaning of a Hebrew text that lacked a technical term for the mounted rotating instruments known as volvelles.Footnote 97

Figure 11: © British Library Board (British Library Add. MS 27091 26r); Polonsky Foundation Catalogue of Digitised Hebrew Manuscripts.

Volvelles, essentially two-dimensional adaptations of the astrolabe, had been in use as calculation devices with a range of applications, from calendrical to mystical, going back in the West to Matthew Paris and Ramon Llull, the latter using them in his late thirteenth-century Ars Magna.Footnote 98 In the Hebrew manuscripts of Cordovero’s time, they were most commonly found in copies of Sefer yeṣirah, where they usefully suited the work’s combinatory exercises. Here, Cordovero deployed them to bridge theory and practice. Cordovero gives a few examples of complex disc rotations that produce distinct results, but concludes with the simplest: “Now, if we rotate Ḥoḵmah alone ten times to each of the ten facets of Keter—without changing or rotating the facets of the rest of the sefirot—the number of types of flux will reach 100.” Writing out all possible sequences is clearly out of the question, as even the simplest operations produce overwhelming results: they are literally “impossible to put in writing.” That being the case,

If a person wants to accustom himself to them [the varieties of flux], he should engage himself with the form drawn (בצורה המצוירת) before him and contemplate it for many days, until God enlightens the eyes of his intellect. For the power of the pen fails to elaborate upon these things further, if one does not receive the matter “from mouth to mouth,” or as an enlightened one probing them with his intellect by means of this form. And this form is written upon the page that is before you (בדף שלפניך) on the parchment page (בדף הקלף).Footnote 99

Cordovero, a prolific writer throughout his life, was hardly one to discount the power of the written word, but here admits that, for certain types of understanding, words fail.Footnote 100 Nevertheless, when faced with the impossibility of verbally communicating to his readers the true generative nature of the sefirotic tree, Cordovero fashioned an operational instrument built for simultaneous digital (lit. finger) manipulation and contemplation. Moreover, this technology is promoted as an effective replacement for the only possible, albeit unlikely, alternative: initiation into the oral tradition by a master, “mouth to mouth.” This phrase evokes the introduction of Nachmanides to his biblical commentary, in which he declared that the secrets of the Torah were passed down exclusively “from mouth to mouth.”Footnote 101 For Nachmanides, there was no alternative; for Cordovero, the diagram offered a performative exercise that produced the same results as authoritative initiation. And although it was true that Cordovero feared that the encounter with material drawings of the sefirotic tree might lead to a corporeal conceptualization of the divine, he would ultimately validate it as typically Jewish. Like so much of Jewish tradition, he concluded, the material—in this case, a drawn diagram—served to facilitate the manipulation and circulation of divine energy. Whether an ’ilan or a lulaḇ (the palm frond shaken during the Sukkot festival), each, as he phrased it, functioned as “a body to clothe spiritual reality” (גוף להתלבש המציאות הרוחני).Footnote 102

Circles and Trees: Kabbalah, Astronomy, and Natural Philosophy

The discursive analysis of Cordovero’s masterly treatment of the sefirotic array has shown how profoundly their conceptualization and visualization were indebted to the astronomical tradition. The kabbalistic use of schemata with astronomical pedigrees went hand in hand with the assertion of cosmological ontological continuity, the adop-tion of common metaphors, and, of course, the borrowing of technical terms (constellations, houses, etc.). If the onion skins of ancient astronomy now describe the structure of the sefirot, the circle-sphere schema is a natural choice for their diagrammatic representation.

Yet this analysis raises the question of why the tree, a schema with no astronomical application, was so widely embraced as a visual representation of these same sefirot.Footnote 103 Gerhart Ladner’s remarks are salient in this con-text: “The vegetative-organic tree schemata of the Middle Ages—and even the consider-ably modified tree symbolism of the Renaissance—were apt to express and represent something of the graded and continuous, and nevertheless differentiated, structure of the Christian cosmos of those ages.”Footnote 104 Jews in particular would have been receptive to an arboreal visualization of the sefirot given the prominence of Tree of Life mythologomena in Jewish culture from the Bible to the Bahir.Footnote 105 Without discounting these factors, I should nevertheless like to offer an additional hypothesis—one foreshadowed throughout this essay.

The two fundamental disciplines devoted to developing models of the universe going back to the Greeks were astronomy and natural philosophy. The former attended to the heavens, and the latter to the sub-lunar physical or elemental realm. The perfect spherical universe conceived and visualized by the originally mathematical astronomers enjoyed a long cosmographical afterlife, including its appropriation by kabbalists. Although one finds fewer diagrams in works of natural philosophy than in astronomical treatises, the former routinely deploy squares of opposition and arboreal diagrams to express the dialectical transformations of the four elements and four qualities (hot and cold, dry and humid). If the spherical structure of the universe was consistent from heavenly orbs to divine sefirot, its perfection was, by definition, changeless. Diagramming the sefirot as concentric circles asserts their cosmogonic priority and primordial perfection. The kabbalists, though, needed more from their visualization than changeless perfection could offer. Having developed a notion of the sefirot as the elemental categories from which all of creation was constituted, kabbalists occupied themselves with contemplating their dialectical interactions and combinations. These were what accounted for the variety of creation. Enter the kabbalistic tree: it may resemble a Porphyrian Tree, but rather than drilling down from the general to the particular, its categories are hypostases, ontologized elements arrayed in generative “triadicity.” Its nablas and deltas synthesize oppositions and differentiate unities. The tree schema offers a conceptual richness unattainable by astronomical circles, allowing for the sefirot to interrelate dynamically and endlessly. A portion of the kabbalistic tree might also be isolated to form a “square of opposition,” another standard, even ubiquitous schema of medieval natural philosophy [Figure 12].Footnote 106

Figure 12: Obras Cabalísticas, ‘Eser Sefirot Belimah [Escuela de Estudios Árabes (CSIC) Ms64, fol. 282v]. http://simurg.bibliotecas.csic.es/viewer/image/CSIC001353367/576/

Another advantage of the arboreal schema was in its branches—the subject of the discussion in the Pardes that follows Cordovero’s treatment of sefirotic arrays. These branches were correlated to the twenty-two letters of Sefer yeṣirah (3+7+12), and ontologized as the channels through which the divine effluence flowed. A typical three-columned Tree of Porphyry with its ten “nodes” in the 3-4-3 array fits the 3+7+12 of Sefer yeṣirah perfectly. There are three possible horizontal lines, precisely seven lines that “double” within a given trajectory, and twelve diagonal lines connecting the rest [Figure 13].Footnote 107 Despite this neat fit, the consensus that the bottom node representing Malḵut/Šeḵinah had to be lower than the rest of the structure made it necessary to establish rather less elegant correspondences. The symmetrical array is rarely found in kabbalistic manuscripts.

Figure 13: Prague Jewish Museum MS 69 (170.219), 182r. Reproduced with permission from the Jewish Museum in Prague Photo Archive.

I have endeavored to provide something of an introduction to classical kabbalistic sefirotic diagrams that nevertheless advances a particular thesis. This has meant forgoing a more thorough inventory of kabbalistic iconography, as well as a sustained treatment of important questions ranging from their Sitz im Leben and diverse uses, from meditation to memory to magic, as well as a consideration of the very salient question of the effect of their media, or the ’ilanot as material texts.Footnote 108 Classical kabbalists, to be sure, were hardly earnest students of astronomy and natural philosophy, but they did understand their own project in scientific terms. They saw no discontinuity on the spectrum of scientific pursuits. On the contrary, Kabbalah was for them the science of the divine, crowning rather than opposing the enterprise. It was only natural that in conceptualizing and communicating this divine science, kabbalists appropriated the visual and rhetorical languages of astronomy and natural philosophy, the most prestigious scientific disciplines of their day. Astronomy and natural philosophy were not what the kabbalists talked about, but how they talked about it. For kabbalists, if not for philologists, the sefirot-spheres connection was always crystalline-clear.