Dissociation, described simply, is the lack of connection between things that are normally connected and associated (International Society for the Study of Trauma and Dissociation 2011). The first full description of the concept is credited to Pierre Janet (1859–1947) in his medical thesis L'état mental des hystériques in 1892. Janet was one of the first to propose a connection between events in the individual's past and their present-day difficulties and that dissociation was the most direct psychological defence against overwhelming experience. He identified dissociation as the mechanism underlying hysteria, which at the time included presentations and diagnoses now known as dissociative disorders, somatisation, conversion, borderline personality disorder and post-traumatic stress disorder. He described the concept of somnambulism, in which two or more states of consciousness are dissociated, separated by amnesia and operating independently of each other (van der Hart Reference van der Hart and Horst1989a).

In Janet's and related theories, dissociation is considered instinctive, natural, adaptive and universal, with the potential to affect anyone. It is a combined psychological and physiological coping response that is activated when an experience is perceived to be simply too over-stimulating, too distressing, too painful, traumatising or life-threatening. It enables different aspects that make up an experience (e.g. thoughts, beliefs, sensory perceptions, emotions, bodily experiences such as pain, behavioural response) to be stored in a way that keeps them separate from each other and so makes them more manageable. Dissociation occurs on a spectrum of severity, from brief ‘normal’ immersion/absorption or anxiety-induced distraction to the more severe presentations that are the focus of this article.

After a traumatic event, dissociation can serve to minimise awareness of its effects or indeed of the event itself, so that it is as if it never happened. Dissociation at this level allows focus on the stimuli and tasks necessary to safely manage, negotiate and survive a traumatic situation in a way that minimises immediate harm or allows escape, either physical or psychological. Severe dissociation is considered the brain's alternative when the mind is overwhelmed by a sense of fear or powerlessness and there is no identifiable escape.

Porges & Levine’s (2011) polyvagal theory of physiological response to threat offers a helpful explanation and understanding of the physiological process that underpins the dissociative response. It also provides an explanation for both clinicians and patients of the use of body-based interventions for ‘grounding’ for patients experiencing dissociation (Box 1).

Box 1

Jargon Buster:

Grounding – Supporting the patient to be fully connected and aware of the present time and situation in both body and mind.

Action systems for daily life – The things we do in day-to-day life and the associated behaviours and responses to them.

Action systems for survival – These are the things we do in trauma/threat based situations and the behaviours and responses to them e.g. fight, flight, freeze.

Dissociative system (the system) – Where structural dissociation is present, the “system” is a collective description of the different component parts that are present within it.

Primary patient ANP – “passport holder” ANP – Within structural dissociation this is the part of the system which is the “main” part or patient that we work with who has primary responsibility for the “whole” person. This normally represents the original part from which all others split off.

Understanding the role of dissociation in trauma-related disorders

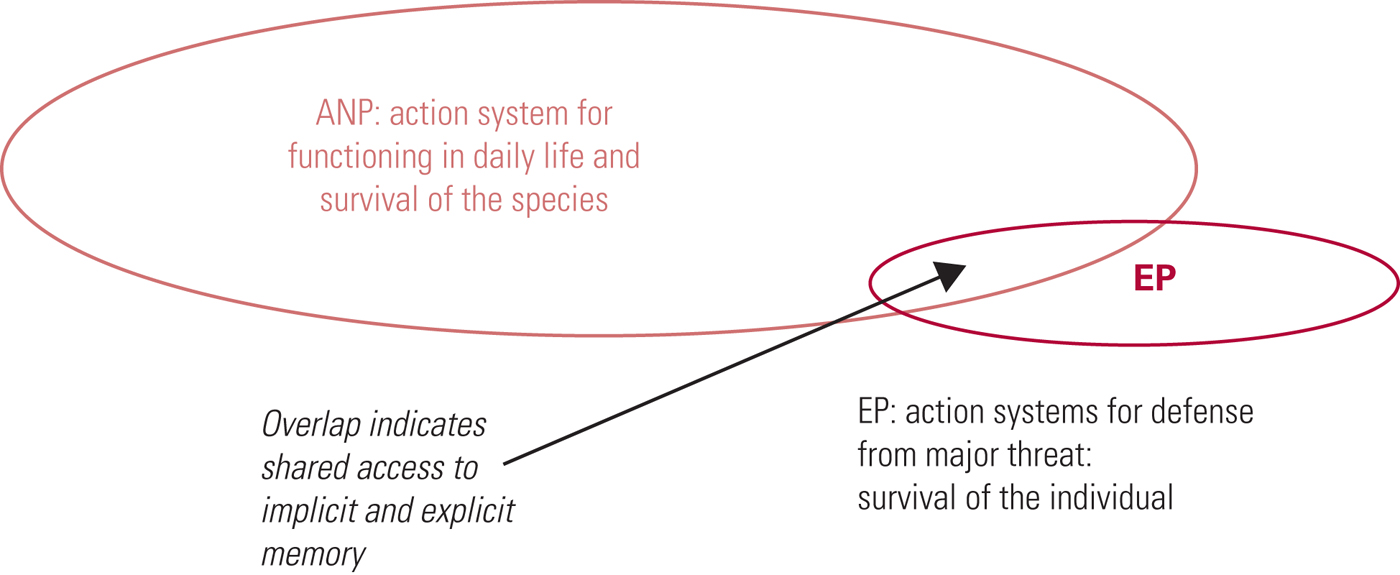

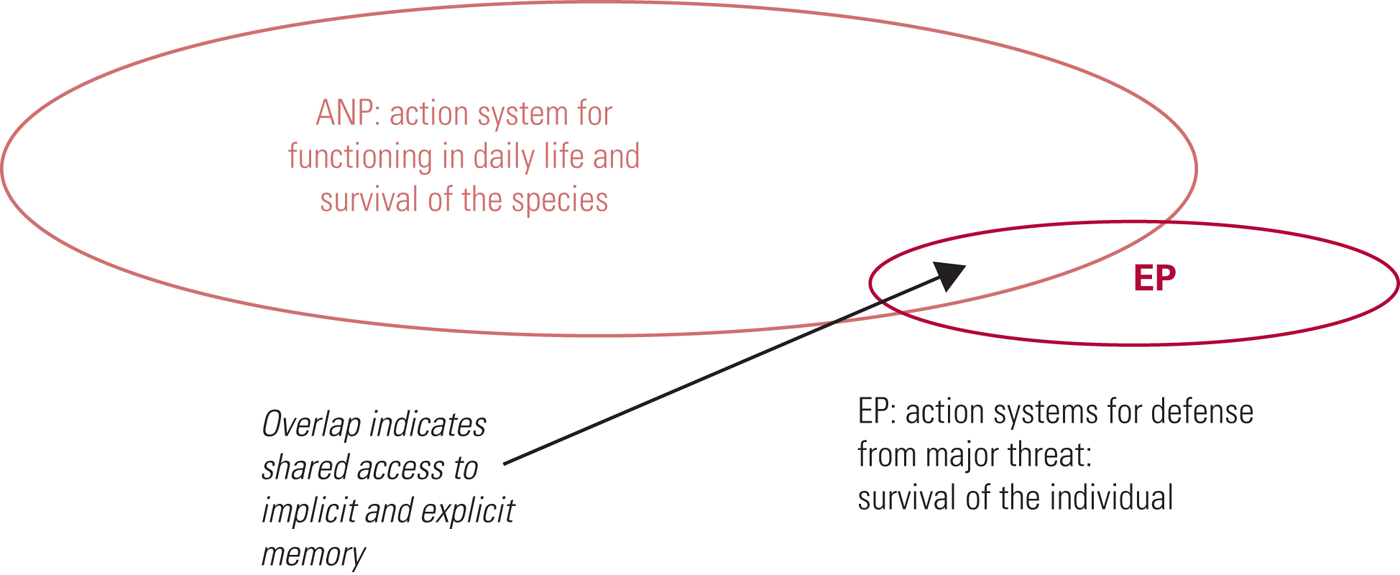

Building on Janet's work, Nijenhuis et al (Reference Nijenhuis, van der Hart and Steele2001) proposed a model based on their theory of structural dissociation of the personality to explain the role of dissociation in the presentation of trauma-related disorders, including simple and complex post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), borderline personality disorder and the severe dissociative disorders – dissociative identity disorder (DID) and dissociative disorder not otherwise specified (DDNOS) (for clarification see ‘DID and DDNOS as diagnostic categories’ below). The concept of trauma within this model also incorporates developmental trauma associated with severely disrupted or disorganised attachments in early childhood. They describe a dissociative response to traumatic experiences (including developmental trauma) that results in the division of the personality into ‘emotional’ and ‘apparently normal’ parts. An ‘emotional’ part of the personality (EP) holds and is fixated on the traumatic memories and associated actions for surviving the threat; an ‘apparently normal’ part of the personality (ANP) is focused on action systems for daily life and survival of the species and will very specifically and actively try to avoid trauma-related cues. An individual may have more than one EP and/or ANP.

In simple PTSD the experience of the trauma results in a primary-level structural split or dissociation (Fig. 1) until the information contained by the EP can be processed accordingly and the split resolved. The overlap shown between the EP and ANP represents shared information that the patient experiences as intrusion (re-experiencing) symptoms of the event, thus triggering the learned survival response held within the EP.

FIG 1 Primary structural dissociation, for example in simple post-traumatic stress disorder. The individual presents with one apparently normal part of the personality (ANP) and one emotional part of the personality (EP) (after Nijenhuis et al, Reference Nijenhuis, van der Hart and Steele2001).

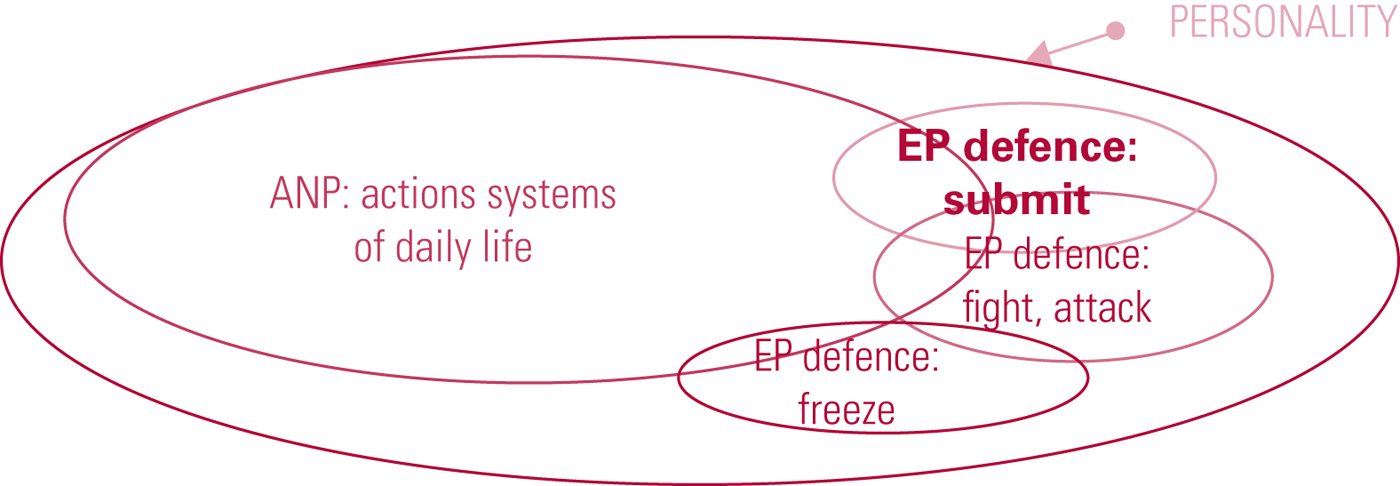

In multiple traumatic experiences, including the developmental trauma seen in borderline personality disorder, a secondary-level structural split occurs (Fig. 2) with the creation of multiple EPs, each of which holds a different traumatic experience and associated behavioural responses. Connection to these EPs is triggered by present-day events that have resonances with past traumatic experiences. They are often associated with particular emotions, interpersonal interactions or attachments, and the patient's behaviour and functioning in the present are driven by the ‘modes’ and ‘ways of being’ that allowed survival in the past. The triggering of the connections is not necessarily a conscious process, but can be brought into conscious awareness by behaviour and symptom monitoring and therapeutic discussion.

FIG 2 Secondary structural dissociation, for example in complex post-traumatic stress disorder, borderline personality disorder, disorder of extreme stress not otherwise specified (DESNOS) and dissociative disorder not otherwise specified (DDNOS). The individual presents with one apparently normal part of the personality (ANP) and several emotional parts of the personality (EPs) (after Nijenhuis et al, Reference Nijenhuis, van der Hart and Steele2001).

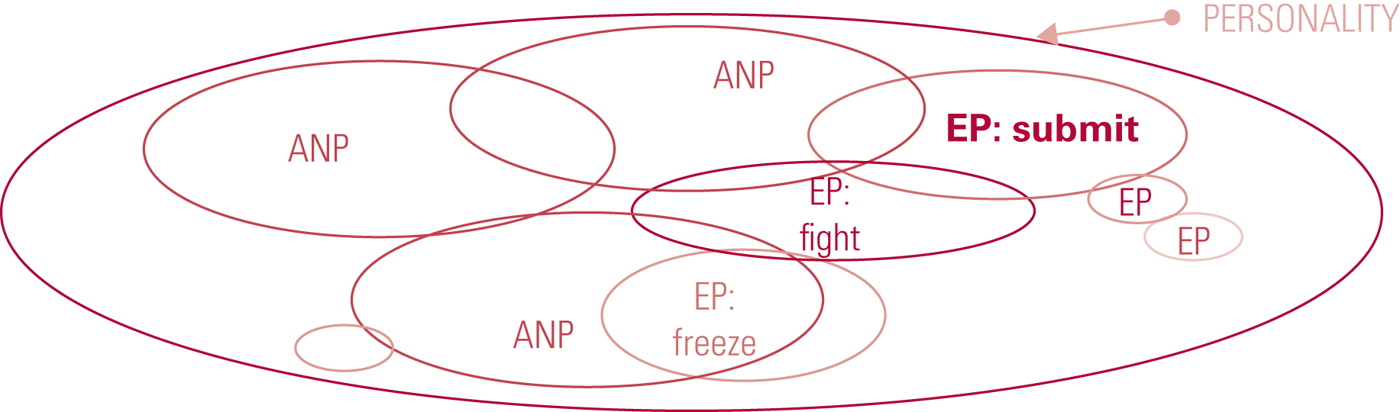

Where the traumatic experience is prolonged, repeated, with high levels of extreme fear, helplessness, loss of control and no means of escape and/or dependence on the abuser for survival, a separate ‘functioning part’ – a separate ANP – becomes necessary for survival. This can be seen, for example, in the child who goes to school and engages in normal life but comes home to be abused on a daily basis by the primary caregiver. A separate functioning part might also develop where the trauma itself requires a particular type of functioning, for example actions to be completed in ritualistic abuse. This results in tertiary-level structural dissociation (Fig. 3) where, in addition to the patient's primary ANP – the passport holder, as it were – further ANPs are present and these take over the individual's functioning in response to a particular situation or intrusion symptoms. As can be seen in Fig. 3, there may be awareness or connection between some ANPs, but unawareness and disconnection (dissociative amnesia) between others. In addition, there are multiple EPs that have varying connection to the different ANPs. Owing to the extreme nature of the experienced trauma, these often contain just elements of experience such as body memories or emotions. EPs also may be completely disconnected from the conscious awareness of passport holder primary ANP, leading to ‘blanks’ in the patient's timeline.

FIG 3 Tertiary structural dissociation, for example in dissociative identity disorder (DID). The individual presents with several apparently normal (ANPs) and several emotional parts of the personality (EPs) (after Nijenhuis et al, Reference Nijenhuis, van der Hart and Steele2001).

Controversy surrounding the theory and concept of dissociative disorders

Janet's work and theories were all but abandoned in the early 1900s, when hypnosis fell into disrepute and the focus shifted to Freud's psychoanalytical theory. Interest was reignited from the 1950s, with various publications and, in 1965, the reprinting of Janet's The Major Symptoms of Hysteria in an effort to try to understand responses to traumatic experiences (van der Hart Reference van der Hart and Friedman1989b). Identification of dissociative components and their role in complex disorders such as PTSD and borderline personality disorder, alongside descriptions and diagnosis of specific dissociative disorders, increased, but this increase unfortunately coincided with concerns about recovered false memories of childhood sexual abuse during hypnosis and other clinical therapeutic work.

Rightly or wrongly, dissociative disorders, in particular DID (or multiple personality disorder, as it was commonly called then), and false memories became inextricably linked in the minds of clinicians. This was not helped by glamorised media portrayals of DID such as the American television series Sybil in 1976. Statements and reports from various bodies, including recommendations of the Royal College of Psychiatrists’ Working Group on Reported Recovered Memories of Child Sexual Abuse (Brandon Reference Brandon, Boakes and Glaser1997), raised concerns as to the concepts of dissociation and dissociative amnesia and highlighted the lack of empirical scientific evidence to support dissociation or the forgetting of repeated experience. The Working Group noted that there was no means of determining the factual truth of recovered memory other than by external evidence which, for many reasons, may not be practicably obtainable. Interestingly, the recommendations could not be published in the form of a consensus statement from the College, as the group did not reach consensus on all aspects of the matter.

The theory and concepts of dissociation, its role in psychiatric disorders and the specific dissociative disorders themselves continue to be debated in UK psychiatry and psychology. Little formal teaching is given on the subject in general training, even during discussions of the dissociative disorders themselves, and the focus is often restricted to depersonalisation and derealisation. The consequence of this for clinicians and patients is a lack of working knowledge to inform understanding, diagnosis and treatment recommendations, and therefore little service development. Recommended further reading on the subject is listed in Box 2.

Box 2 Recommended further reading

Guidelines

International Society for the Study of Trauma and Dissociation (2011) Guidelines for Treating Dissociative Identity Disorder in Adults, Third Revision. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 12: 115–87 (available at www.isst-d.org/default.asp?contentID=49).

Books

Boon S, Steele K, van der Hart O (2011) Coping with Trauma Related Dissociation: Skills Training for Patients and Therapists. WW Norton.

van der Hart O, Nijenhuis ERS, Steele K (2006) The Haunted Self: Structural Dissociation and the Treatment of Chronic Traumatization. WW Norton.

Steele K, Boon S, van der Hart O (2017) Treating Trauma-Related Dissociation: A Practical, Integrative Approach. WW Norton.

Online resources

TraumaDissociation.com: http://traumadissociation.com/dissociativeidentitydisorder

International Society for the Study of Trauma and Dissociation (ISSTD): www.isst-d.org

Positive Outcomes for Dissociative Survivors (PODS): www.pods-online.org.uk

First Person Pleural: www.firstpersonplural.org.uk

A Kelly: ‘I am not one: documentary about dissociative identity disorder’ (duration 7 min 42 s): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mgDTcfky6VU

Severe dissociative disorders

Severe dissociative disorders such as dissociative identity disorder (DID) and dissociative disorders not otherwise specified (DDNOS) result from a complex combination of developmental, interpersonal, environmental and cultural factors. Clinical reports show strong association with repeated experiences of severe childhood trauma against a background of developmental attachment trauma and the associated biological responses to these in the brain (Brand Reference Brand2012a).

To survive multiple and/or complex traumatic experiences over a prolonged period, particularly during early childhood when the brain and personality are developing, the brain may separate and fragment various aspects of the individual's experiences; interaction of these aspects shapes the developing neural pathways and responses. A person's sense of identity, perception of reality and appreciation of the temporal continuity of their experiences and life rely on their thoughts, sensations, feelings, perceptions, sense of body, sense of self, behaviours and memories being mostly connected to each other, making up the ‘jigsaw’ of the self. Dissociative responses and disconnection of experiences are adaptive responses to repeated early interpersonal trauma that allow for survival and continued functioning. As a result of such adaptive responses, the individual's sense of who they are, how they experience their ‘person’, their memories and how they access them (if, indeed, they consciously can), together with the way they see other people, things and the world around them, can become chronically fixed in a disjointed and fragmented, i.e. dissociative, pattern.

These early ‘logical survival’ responses and behavioural patterns become maladaptive if they persist when the traumatic situations and interpersonal threats are no longer present. The perpetuation of these patterns can have a major impact on daily functioning, as the individual habitually and unconsciously disconnects from normal situations and everyday experiences such as emotions and interpersonal interactions, which they instinctively perceive to be ‘dangerous’ without the real-time determination of the actual dangers.

DID and DDNOS as diagnostic categories

DID

DID is coded and outlined in the DSM V (APA 2013; Code 300.14) and in the updated revision of the ICD-11 (WHO 2018).

In earlier editions of the DSM the condition was known as multiple personality disorder, but it was renamed DID in 1994 when it was reconceptualised as identity fragmentation of a single personality (as described in Figs 1–3) rather than a proliferation of separate personalities. ICD-10 continues to refer to multiple personality disorder (in F44.8: Other dissociative [conversion] disorders), although this is expected to change in ICD-11 (WHO 2018).

DDNOS

The diagnosis DDNOS (formally termed ‘other specified dissociative disorder’ in DSM-5 (APA 2013) and ‘partial DID’ in the ICD 11 (WHO 2018)) is generally applied when someone does not quite meet the DID criteria. The most common forms of DDNOS involve amnesia and dissociative parts of the personality that are not quite distinct/separate enough for DID, or dissociative parts that are distinct enough to be ‘alter’ personalities (see below) but without the amnesia between them. Interestingly, the process of therapy for a patient with DID in essence takes them back through DDNOS in the communication and integration work.

Brand and colleagues reported that DID and DDNOS have been validated across a range of markers in different settings and can be clearly and accurately discriminated from other disorders (Brand Reference Brand and Lanius2014a,Reference Brand, Dorahy and Krugeb). Diagnosis has been facilitated by screening tools such as the Dissociative Experiences Scale II (DES-II), which gives reliable cut-offs for further investigation (Bernstein Reference Bernstein and Putnam1986), and diagnostic structured clinical interviews such as the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Dissociative Disorders Revised (SCID-D-R) (Steinberg Reference Steinberg1994).

Terminology – dissociative parts or states?

The terminology used to describe the different presentations in DID and DDNOS includes parts, alters, ego-states and selves. It can be useful to agree on a set approach that distinguishes between ‘functioning’ presentations that affect the patient's daily life and emotional responses arising from the original trauma. In daily practice I prefer to use ‘self-states’ for ANP presentations and ‘parts’ for EP presentations.

Prevalence of DID and DDNOS

The prevalences of dissociative disorders in general and DID and DDNOS in particular have been estimated in community samples and psychiatric out-patient and in-patient settings in the USA and Europe (Table 1). To date there are no published prevalence studies from the UK. The wide range of values and variation across countries for dissociative disorders in general raises concern about the validity of the findings from the studies. The lower end of the range does seem consistent across countries, so may be more representative. Within the discussion of Foote et al's paper in 2006 there is a review of the work across inpatient setting prior to this outpatient clinic research. Contrary to popular opinion in the UK, dissociative disorders, even at the lower end of the estimated range, seem not to be rare conditions and will be presenting in the populations being seen in clinics and in-patient settings. This considered ‘rarity status’ unfortunately means that delays in diagnosis are common: the average time to diagnosis quoted on patients’ websites such as PODS (https://information.pods-online.org.uk/) is 7 years, and for many it is much longer. Foote et al (Reference Foote, Smolin and Kaplan2006) reported that, of the 24 psychiatric out-patients (29%; N = 82) they diagnosed with a dissociative disorder, only 4 (5% of the total) had been previously identified as having such a disorder.

TABLE 1 Collated prevalence data on dissociative disorders in different settings

DDNOS, dissociative disorder not otherwise specified; DID, dissociative identity disorder.

From personal experience when discussing the prevalence of these disorders amongst psychiatric colleagues concerns are often raised regarding the cross-over of symptoms between disorders such as borderline personality disorder, dissociative disorders and complex PTSD presentations, in particular when these can also have dissociative symptoms within them. Questions being asked around how we can be sure these studies are looking at rates of dissociative disorders as opposed to those which might have dissociative symptoms. This would certainly be more of a concern for those studies that only use the DES-II screening tool as opposed to both the DES-II and the SCID-D-R diagnostic interview. This approach would also seem to be supported within ICD-11 coding for dissociative disorders which states “The symptoms of dissociative disorders are not due the direct effects of a medication or substance, including withdrawal effects, are not better explained by another Mental, behavioural, or neurodevelopmental disorder, a Sleep-wake disorder, a Disease of the nervous system or other health condition” indicating the need for a level of detailed understanding of the symptoms to support classification under this stem 6B as opposed to other disorders such as personality disorder or complex PTSD in which these symptoms can also present. A useful review of the similarities and differences between DID and borderline personality disorder can be found in Brand & Lanius (Reference Brand and Lanius2014a), which points out that, although the rates of comorbidity of the two disorders are high, they are not always present together.

Comorbidity in dissociative disorders

Trauma and trauma-based responses are increasingly being understood as underpinning and maintaining many mental illnesses. It is therefore not surprising that the trauma-based disorders of PTSD, complex PTSD (WHO 2018), DDNOS and DID would show high comorbidity with other psychiatric disorders. Rodewald et al (Reference Rodewald, Wilhelm and Enrich2011) investigated rates of comorbid diagnoses (excluding personality disorder) in patients with DID, DDNOS and other psychiatric disorders. On average, individuals with dissociative disorders had five comorbid Axis I diagnoses, whereas individuals with simple PTSD, anxiety or depression had two. Table 2 outlines the results of some studies of comorbidity in dissociative disorders.

TABLE 2 Comorbidity in dissociative disorders

DID, dissociative identity disorder; PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder.

Identifying comorbidity is important because of its impact on treatment outcomes. Many studies have shown higher treatment drop-out rates, poor outcomes and lower response with standard psychological treatments for PTSD, anxiety disorders, addictions, borderline personality disorder, obsessive–compulsive disorder and eating disorders among people with comorbid dissociative disorders (Belli Reference Belli2014; Brand Reference Brand2012a,Reference Brand, Lanius and Vermettedb, Reference Brand, Dorahy and Kruge2014b; Evren Reference Evren and Sar2007; Karadag Reference Karadag, Sar and Tamar-Gurol2005; Kleindienst Reference Kleindienst, Limburger and Ebner-Priemer2011; Spitzer Reference Spitzer, Barnow and Freyberger2007; Tobin Reference Tobin, Molteni and Elin1995). If dissociative disorders are not correctly identified, comorbid psychiatric illness may be incorrectly labelled ‘treatment resistant’. Of particular concern is that, notwithstanding rates of comorbid dissociative disorder as high as 75% in people with borderline personality disorder and the associated predicted poor response to standard dialectical behaviour therapy, few personality disorder services or referring clinicians screen for the presence of dissociative disorders before referral. Consequently, many patients drop out of treatment or are inappropriately considered non-responders, become ‘revolving-door’ patients or are discharged without being offered appropriate specialist treatment.

This is not to say that a comorbid dissociative disorder is more important or should be the only focus of treatment, but understanding its impact allows the appropriate planning and phasing of treatment. Trauma-related disorders such as complex PTSD and dissociative disorders are often the ‘taproot’ maintaining other conditions that have developed to allow the individual to manage or cope with the trauma. Comorbid dissociative disorder and eating disorder is a case in point. Treatment focused only on the eating disorder will not be successful. Equally, trauma therapy will not treat the eating disorder, which will need treatment itself once the specific trauma-focused approach has removed the maintainer. Unfortunately, services are not often set up in a way that allows for such combined management and the separation and fragmentation of service design further hampers treatment for people with these complex illnesses.

Is there any neurobiological evidence supporting these disorders?

In a review paper a few years ago, Brand et al (Reference Brand, Lanius and Vermetted2012b) cited the latest neurobiological research on dissociative disorders, which includes findings from single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) brain regional blood flow imaging, electroencephalogram (EEG) coherence analysis, and hippocampal and amygdalar volume studies. Reinders et al (Reference Reinders, Nijenhus and Quak2006) found different SPECT regional blood flow patterns, indicating specific changes in localised activity across the different selves in people with DID. Sar et al (Reference Sar, Unal and Ozturk2007) showed reduced perfusion in the orbitofrontal region bilaterally and increased perfusion in the median and superior frontal regions bilaterally in DID. Vermetten et al (Reference Vermetten, Schmahl and Lindner2006) demonstrated reduced hippocampal and amygdalar volumes in DID, findings consistent with those of other trauma-related disorders, such as PTSD. Hopper et al (Reference Hopper and Ciorciari2002) studied EEG coherence as an objective measure of cortical connectivity in five people with DID who had 15 ‘alters’ between them and compared them with five control professional actors who were asked to simulate alters. There were significant reductions in EEG coherence between patients and their alters which were not found in the actors when simulating alters.

Risk in DID and DDNOS

DID and DDNOS in adults are repeatedly found to be highly correlated with risk, including self-harm and suicide attempts. Foote et al (2008) investigated suicidality and non-suicidal self-harm in patients consecutively admitted to a psychiatric out-patient clinic; 82 patients were screened for dissociative disorders, borderline personality disorder, substance misuse and trauma history, and were assessed on measures of self-harm and suicidality. Patients with dissociative disorders scored highly on all measures of self-harm and suicidality; the presence of a dissociative disorder was the strongest predictor of a history of multiple suicide attempts. Depersonalisation is commonly reported during self-harm in both dissociative disorders and borderline personality disorder, as is non-suicidal self-harm to stop unbearable hyperarousal or control the re-experiencing of trauma symptoms.

Risk is further complicated by the possibility that self-states (ANPs) will carry out extreme behaviours that would be against the conscious will or wishes of the patient. On ‘coming round’, the patient reconciles (‘grounds’) these behaviours with their consequences, but has no memory or understanding of them. Many patients therefore feel out of control, helpless and a sense of overwhelming shame. Unfortunately, this ‘amnesia’ to events is often not believed or is dismissed by clinicians as attention-seeking. This can lead to additional feelings of shame and alienation and provoke suicidality that the individual did not previously feel (based on patient reports within clinical practice).

These dissociative behaviours are often a self-state's attack on the patient and, given that self-state commonly experiences itself as separate from the patient, these attacks can be extreme. Such behaviours may include high-risk sexual activity such as prostitution or sex with strangers and damage to the genitals or breasts. The context, extent and severity of the behaviour are generally linked to, and make sense in the context of, survival strategies used to cope with past trauma or to protect the patient from ‘worse’ to come. There may also be re-enactment of past trauma or use of learned behaviours that arose from traumatic experiences.

Specialist treatment approaches

As mentioned above, non-specialist psychological treatments, including standard trauma treatments, with no focus on dissociative symptoms are associated with high drop-out rates and poor response. Although the evidence for effective specialist treatments is limited to observational studies and case reports, these do demonstrate after-treatment effects of reduced dissociative and trauma symptoms, decreased hospital admissions and service use, reduced self-harm and depressive symptoms and improved functioning on the Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) scale (Brand Reference Brand2012a,Reference Brand, Lanius and Vermettedb, Reference Brand, Dorahy and Kruge2014b).

To help clinicians working in the field, an international task force of 34 expert clinicians and researchers produced a third revision of guidelines on the treatment of dissociative identity disorder in adults (International Society for the Study of Trauma and Dissociation 2011). The guidelines describe a fluid, three-phase treatment programme focusing on: stabilisation, including risk reduction, functioning and resilience skills; modified trauma-informed approaches; and recovery.

Phase 1 of the programme (establishing safety, stabilisation and symptom reduction) focuses on emotions, interpersonal functioning and relationships, compassion, body connection and arousal management, trauma and dissociative symptoms, self-management strategies, internal system work for internal connection, communication and compassion, and understanding of roles/risk across the dissociative system and crisis planning. Risk assessment and management approaches are considered from both the ‘grounded connected’ and ‘dissociated behaviours’ perspective.

Phase 2 (confronting, working through and integrating traumatic memories) involves trauma processing using adapted trauma-informed approaches that incorporate the dissociative presentations.

Phase 3 (integration and rehabilitation) focuses on the progression and skills the person needs for their desired future beyond the illness and the experience of connection is new to the patient.

The fluidity of the programme means that the therapy can move backwards and forwards across the three different phases as required, depending on the presentation and needs at the time.

Integrative therapy approaches are recommended rather than any single modality, ideally with 90-minute sessions twice weekly (ISSTD 2011). Therapists should have specialist training and supervision for working with dissociative disorders. Treatment typically lasts 7–10 years and community-based interventions are key. Brief in-patient stays in supportive environments in which the staff understand dissociative and trauma-related disorders have also been shown to help with risk management if needed. Repeated admissions to non-specialist acute psychiatric settings and treatment programmes addressing comorbidities with no focus or interventions for dissociative aspects are not felt to be helpful and not recommended.

Presentation and management in the non-specialist setting

‘The people who are the very best at noticing what's happening notice it because they are looking’

Seth Godin, business guru, 2015

As noted above, people with DID and DDNOS can present in all healthcare settings. These disorders are not rare conditions, but may be undiagnosed when they are comorbid with more readily recognised and commonly diagnosed conditions. Patients may be labelled as treatment ‘non-responders’, ‘revolving-door’, ‘chronic complex’ or ‘difficult to engage’ and are often associated with repeated high-risk presentations. The key for clinicians is to have a low threshold of suspicion for the presence of dissociative disorders.

Patients may be experiencing multiple symptoms from different diagnostic categories (e.g. psychotic, affective, personality disorder). These symptoms often include voice hearing, which can be internal, external, derogatory, running commentary or command, and the voice is experienced as separate from the patient. Other first-rank symptoms include passivity phenomena in all modalities and hallucinations in other senses. Affective changes, often rapid, may be evident, with switches between a blunted, stuporous or even ‘freeze’ presentation and an agitated or hypomanic state. Repeated self-harm, often extreme in nature, alongside repeated suicide attempts and other harmful coping strategies and ‘difficult to understand’ behaviours are often evident and result in repeated presentations to services.

When the symptoms and experiences are explored by specific questioning, amnesia in relation to events and aspects of daily functioning may be present, alongside a history of trauma or a ‘vague’ personal history. If the patient is able to discuss their trauma history, it may be evident that symptoms are linked to traumatic experiences. Trauma- and shame-based beliefs of being worthless, unlovable, deserving of harm and responsible for what has happened are common. There will often be a history of extreme responses to situations (particularly interpersonal situations) that might be expected to evoke an emotional reaction, although the patient may subsequently not recall these responses. In such cases, the situation triggers re-experiencing of the original trauma. Patients may also report amnesia in relation to discussions had in clinical interactions or may behave in different ways at different times in different settings or with different staff. This behaviour may be associated with different dissociative self-state presentations at the time.

Box 3 lists factors that might point to the presence of a dissociative disorder. If any of these factors are present, the key is to ask specifically about trauma and dissociative symptoms, in particular amnesia in relation to events and daily life, and to try to take a trauma history.

BOX 3 When to suspect the presence of a dissociative disorder

• Reported full or partial amnesia in relation to personal history of childhood and adolescence

• Multiple different psychiatric diagnoses over time and different symptom profiles, e.g. psychotic, affective, personality disorder

• Reported amnesia in relation to conversations, aspects of life and behaviour such as self-harm

• Apparent ‘resistance’ of any Axis I condition to all standard treatments

• Borderline personality disorder with severe self-harm and no response to dialectical behaviour therapy

• New-onset symptoms in adulthood, in particular risk behaviours and apparent ‘personality disorder’ after previous high levels of functioning

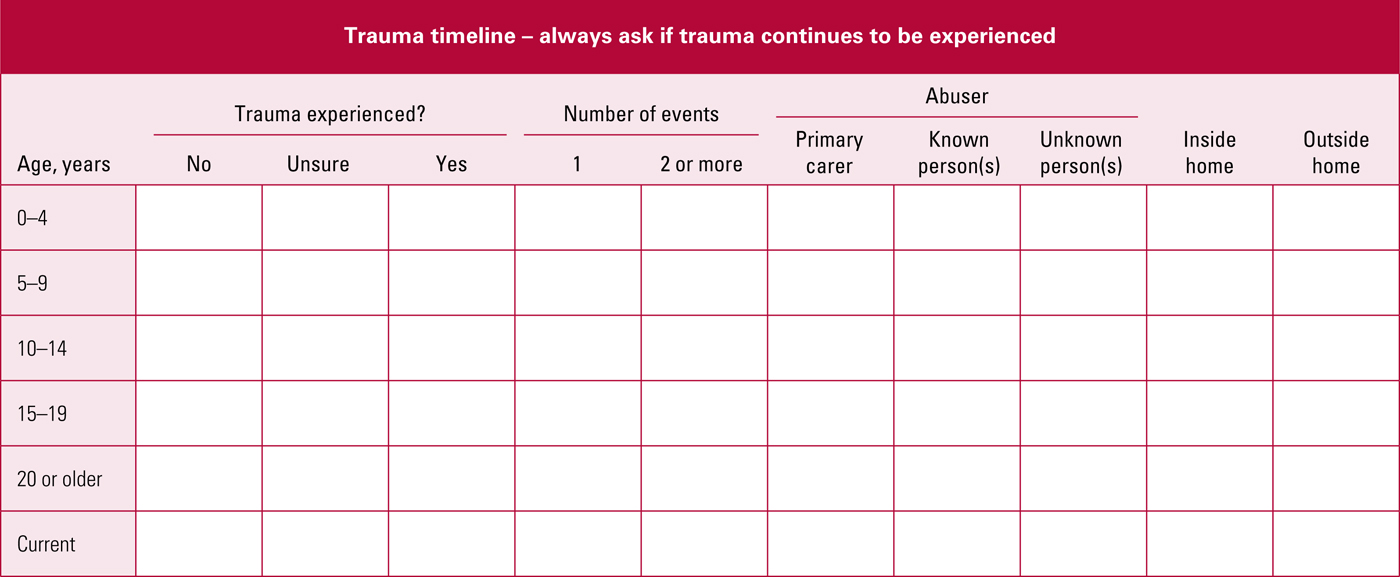

Always ensure that an overview of the patient's trauma history is taken (e.g. using the worksheet shown in Fig. 4) and the Dissociative Experiences Scale is completed (the DES-II is available at http://traumadissociation.com)

Current trauma in an adult should be assumed to be associated with dissociation until proven otherwise

FIG 4 Brief trauma overview and timeline – always ask if trauma continues to be experienced.

Attachment histories are important and often missed or not well addressed in general psychiatry settings, so it is worth examining them again to help identify possible developmental trauma.

Exploration of the following can improve understanding of the developmental base on which the individual's subsequent experiences are built and of their vulnerabilities to harm from others:

• the presence of someone constant to turn to during early life

• the availability of stable, consistent care and nurturing

• learning and language regarding the experience of and responses to emotions

• invisibility – the need to be to be safe and not noticed/seen

• the need to be noticed and behaviours that resulted in being noticed, such as achievements or acting out: for a child who experiences being invisible, receiving any attention may be extremely powerful

• change of roles so that the young person was no longer seen as child, for example when they took on a carer role.

The trauma-overview worksheet shown in Fig. 4 offers a simple and generally ‘safe’ (i.e. less likely to trigger trauma/dissociative responses) way of establishing a trauma history. Ideally, this is completed with the patient, in the context of an established relationship and with the reassurance that the patient need not give any details of past trauma if they do not want to. The patient should also be helped to complete a dissociation screening tool such as the DES-II: a score >30 should trigger further detailed assessment by a trained clinician using the SCID-D in order to establish which dissociative disorders are present so as to guide treatment approaches offered.

If the clinical assessment and SCID-D confirm a diagnosis of DID, a full diagnostic review should be completed with the patient to confirm whether any apparently comorbid psychiatric conditions are in fact explained by the DID. Where a diagnosis of comorbid borderline personality disorder is being considered, the disorder must meet all of the criteria and should be consistently evident in the original passport holder ANP and not just when a self-state ANP is present. The resultant new diagnostic profile should then guide the treatments offered and priorities within the plan of care.

The clinical relationship

‘Helplessness, loss of control and isolation are the core experiences of trauma. Empowerment and reconnection are the core experiences of recovery’

Judith Herman, Professor of Clinical Psychiatry at Harvard University Medical School, 2018

Given that interpersonal trauma is usually the basis of dissociative disorders, the clinical relationship is the key therapeutic tool in both specialist and general settings to support the patient's recovery. Box 4 lists approaches that a survey of patients experiencing DID and DDNOS identified as helpful in developing a good clinical relationship and encouraging engagement in treatment. A curious, non-judgemental and empowering collaborative approach encourages symptom disclosure and engagement of the patient's ‘dissociative system’. Consultant psychiatrists and clinical psychologists should take an active role as the patient's advocate, supporting access to specialist treatment, particularly if it requires commissioner funding, and in the management of comorbid presentations, as this ensures maximising recovery.

BOX 4 Helpful clinical approaches reported by people with dissociative disorders

• Listen, understand and get the context

• Be compassionate, and where dissociative systems exist develop understanding of the parts

• Respect the survival instinct that the parts reveal and any strategies they used when they developed

• Help to develop a joint understanding and support new learning between the patient and the mental health professionals

• Help to develop the individual's sense of connectedness and concept of a ‘whole’

• Help the individual to create a way of being that is a shared mutual collaboration across their dissociative system

Jacqui Dillon (http://www.jacquidillon.org/)

General clinicians should work jointly with specialist therapists and the patient in developing an understanding of different presentations of the self-states, their role and purpose. The dissociative system is always watching and aware in interactions, so this can assist with engagement and with collaborative risk assessment and management.

Risk and crisis management

Risk and crisis management plans should include a basic outline of the patient's dissociative system, different presentations and difficulties, to help staff understand the individual. They should address how risk will be managed and when in-patient care might be needed, for example at specific times of the year, during therapy or in response to life events. It is of paramount importance to ask the patient specifically about their awareness and amnesia in relation to risk events and when safety plans have not been effective. It may be very difficult for the patient to look at this, but is paramount in keeping them safe. Within the National Health Service, early discussions should be had with clinical commissioning groups if services outside of local provision are felt to be needed as part of the plan.

Use of mental health legislation such as the Mental Health Act 1983 in England and Wales can and should be considered where dissociative presentations and associated behaviours place the patient at risk against their expressed wishes or are clearly affecting their decision-making abilities and their capacity to consent. The Mental Capacity Act 2005 and Deprivation of Liberty Safeguards (DoLS) can also be used, for example when a hospital in-patient who has indicated, when ‘grounded’, that they do not want to leave tries to do so while dissociated and lacking capacity. Some patients actively prefer DoLS to be invoked rather than to be detained under the Mental Health Act, as under detention they experience a sense of being ‘controlled’ that mirrors their experience of control by an abuser. I have noticed, however, that in-patient clinicians tend to be less experienced with DoLS. It is therefore useful to discuss use of the mental health legislation openly with the patient and to get their opinions about this; an advance statement indicating the patient's wishes can be useful to guide staff.

In clinic, clinicians should work to negotiate with the patient and their dissociative system so that the original passport holder ANP is ‘present’ and they should actively help the patient to use dissociation management and grounding strategies to make this more likely. Giving the patient written reports of sessions or, if it is feasible and what they wish, digital recordings can allow the patient to remain fully informed and feel in control, regardless of any dissociation and related amnesia that might occur when with the clinician.

Supervision

The management of these complex cases, and the patients’ various presentations, risk and trauma histories result in high levels of vicarious traumatisation in clinicians and teams working with them, and supervision is key to maintain healthy working relationships with, and appropriate support for, the patient.

What do we know about imitative DID presentations?

There a few situations in which an individual might choose to imitate DID. In forensic settings, ‘amnesia’ for events could perceivably be helpful in legal cases. In general settings, mental health services in different regions respond differently to various diagnoses, so a patient might find it preferable to be diagnosed with a dissociative disorder than with a personality disorder (based on patient reports within clinical practice). The lack of a working language in clinical practice for discussing models of dissociation and the role that dissociative experience can play within disorders as opposed to dissociative disorders themselves can lead to some patients, in particular those with severe borderline personality disorder, to feel that standard diagnostic explanations do not ‘fit’ their internal world or fractured sense of self, so they ‘look for’ a diagnosis that does. Brand (Reference Brand, Lanius and Vermetted2012a) comments on this in her review. Work continues in this area to identify specific questions during assessment that might be helpful in identifying the difference between real and imitative presentations. Longitudinal observational assessment remains the gold standard in looking for consistency of presentation and responses over time, settings and interactions. Other key indicators of a possible imitative presentation, even in the presence of an otherwise positive screening and SCID-D, include: a conflict between the ‘need and wish’ for the diagnosis and the shame or fear of receiving it; an extreme response to the thought of not having it, i.e. an investment in having it; and, on the part of the observer/assessor, the absence of a sense that any self-states apparent during assessments are indeed different.

Conclusion

Severe dissociative disorders are ‘real’ and cause considerable morbidity and mortality for those experiencing them. Despite current trends of clinical thinking, patients presenting with symptoms and difficulties consistent with DID and DD-Nos are not rare within general psychiatric practice and are likely over-represented in those considered to be treatment refractory, high risk ‘severe borderline personality disordered’ and with revolving door/high intensity/prolonged inpatient service use. Delays to diagnosis and access to treatment approaches which could be of help are unfortunately therefore common.

As psychiatrists, or doctors in general, we look for what we know and are comfortable with in developing our understanding, diagnosis and treatment planning of patients presenting to us. The clinical practice impact of the limited teaching and training and so working knowledge of these disorders means we are more likely to see/look for any symptoms to ‘fit’ other disorders we know well and associated treatment regimens rather than further question and consider what else the presentations could represent. This delays treatment, worsens morbidity and has the potential to increase risk, including iatrogenic from inappropriate medication use. When this is then followed by a perceived lack of treatment response and continued service use/risk incidents this in turn can lead to burn out in teams treating the patients and the labelling of ‘complex and untreatable’. Disbelief of amnesia to events, non-acknowledgment or ‘minimising’ the impact of trauma and inconsistency of service delivery can lead to the replay of the interpersonal relational issues and patterns that can be seen in abuse cycles and the hopelessness and invisibility experienced within it.

Psychiatric diagnosis and associated recommendations are ‘gate keeping’ in access to treatment including psychological and other specialist approaches and also in supporting access to social support, appropriate housing, aspects such as DVLA and occupational support. It is our diagnosis and coding of such which underpin prevalence data for health economics, identification of the health needs of a population and so service development and delivery. It is of concern that when in discussion with other clinicians working in the field of trauma disorders that in the UK psychiatrists are often seen as the ‘block’ to patients difficulties being understood and so accessing care. It is important for psychiatrists to ensure we continue to develop our understanding and working knowledge of all disorders and are open to new understandings and developments within these, such that in our assessment of patients we remain ‘open’ in our understanding and formulation of their presenting difficulties. In doing so we will hopefully start to more readily identify and help patients with the experience of severe dissociative disorders.

MCQs

Select the single best option for each question stem

1 The estimated prevalence of DID is around:

a 1% in the general population

b 50% of psychiatric in-patients

c 29% among psychiatric out-patients

d 6% among psychiatric in-patients

e 10% in the general population.

2 The average number of comorbid Axis I diagnoses reported in people with dissociative disorders is:

a 2

b 3

c 4

d 5

e 0.

3 The average time to diagnosis for a person with DID is:

a 3 years

b 5 years

c 6 months

d 7 years

e on first assessment.

4 As regards treatments for DID:

a standard psychotherapies such as dialectical behaviour therapy and cognitive–behavioural therapy have been shown to be helpful

b standard trauma therapies have been shown to be helpful

c there are no treatments available

d no modifications to standard approaches are needed

e a stepped approach focusing on dissociative symptoms and modified trauma-informed approaches has been shown to be helpful.

5 In a general psychiatry setting, a clinician working with a patient with a severe dissociative disorder should:

a consider the dissociation as a behaviour within a personality disorder presentation

b take a curious, validating, collaborative and non-judgemental stance

c take a detailed trauma history

d consider the patient to be malingering, as these disorders do not exist

e ignore the presentation in front of them.

MCQ answers

1 a 2 d 3 d 4 e 5 b

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.