Mexico may form part of the ‘New World,’ in the European understanding of the term, but in reality, much of the territory included within the present-day Republic formed part of a very old world. Until the end of the fifteenth century and the first decades of the sixteenth century, this old world remained unknown to the inhabitants of other continents. Accordingly, we need to appreciate the diversity and long duration of this pre-Columbian past if we are to explain colonial and contemporary Mexico. This book's structure and the approach reflect that chronological and thematic sweep. The principal objective is to identify the overriding themes and issues, as the in-depth detail may be found in the wide-ranging and growing bibliography of Mexican history. I strongly recommend the reader to plunge into this rewarding subject matter.

Modern territorial boundaries, however, distort the cultural and political dimensions of the pre-Columbian world in Mesoamerica. The geographical dimension of Maya civilization, for example, included areas such as the Yucatán peninsula, which would become in Spanish-colonial times the south-eastern territories of the Viceroyalty of New Spain, established in 1535, and formed much of the northern sector of the Kingdom of Guatemala. Although Maya sites such as Palenque, Bonampak, and Yaxchilán are today located in the Mexican State of Chiapas, this territory formed part of Guatemala until 1823. Classic Period Maya sites, such as Tikal and Copán, are located respectively in the present-day republics of Guatemala and Honduras. Knowledge of Maya civilization is disseminated today from the capital-city museums of these respective republics, particularly Mexico City, which at the time played no role whatever in its original flourishing. In that sense, the Maya and other pre-Columbian inheritances have been appropriated by the national states to reinforce their national identities, distinctiveness, and legitimacy. In short, the pre-Columbian world has been brought back to life, in order to serve a political purpose in the present day.

Two chronologically distinct processes have been at work since the collapse of the pre-Columbian world. First, the creation of a Spanish colonial political and economic system founded on different cultural principles was imposed upon the existing political and territorial units. Second, a Mexican national state has been constructed out of the former Viceroyalty of New Spain. In these two processes, discontinuities and continuities existed, sometimes incongruously, side by side. The radical difference but underlying persistence between contemporary Mexico and its pre-Columbian and colonial past make it imperative that we do not write history backward from the exclusive perspective of the present, but try to understand the past from within its own terms of reference.

Map 1.1 Contemporary Mexico

Geography and environment help to explain the economic and political developments throughout this historical experience. Ethnic and linguistic diversities have combined with regional and local disparities to shape Mexican culture and define its distinctive culture. A number of obvious contrasts spring to mind: the openness and dynamism of the north, the cultural and ethnic mixtures of the core zone from Zacatecas and San Luis Potosí to Oaxaca with its colonial cities and Baroque architecture, the Maya world of Yucatán and Chiapas, and, above all, the ceaseless pace of Mexico City, a cosmopolitan megalopolis bursting at the seams. Federalism, first adopted in 1824, and again in 1857 and 1917, was a reflection of this diversity and an attempt to give institutional life to the changing relationships between province and centre, locality and province, between the provinces themselves, and between presidential power, the legislature, the judiciary, the state governments, and the municipalities. Much of Mexican history from the nineteenth century onward has seen the playing-out of these respective tensions in search of a workable balance.

Despite deep political divisions, economic difficulties, foreign interventions, revolutionary upheaval, and, in the contemporary period, the struggle against organised crime, the Mexican Republic has held together as a sovereign state. Even the spoliation of territory in 1846–8 or revolutionary civil war between 1910 and 1920 did not lead to its break-up. The strength and richness of the Spanish language and the survival of indigenous languages help to account for the country's resilience and distinctiveness.

Sovereignty, Territory, and National Sentiment

The Spanish colonial era took Mexican territory much further northward than the limits of the Aztec Empire, which it had superseded in 1521. In contrast to Peru, where the newly founded Spanish capital, Lima, lay near the coast but the Inca capital, Cuzco, had stood high in the southern Andes, the Spanish capital of New Spain had been placed right on top of the Aztec principal city of Tenochtitlán. Mexico City, before and after Independence, became the unchallenged dominant city, avoiding the polarities in Peru. Mexico City became the seat of the Audiencia of New Spain, the supreme judicial body, modelled on the Castilian prototype, although with major administrative faculties and political powers.

Effectively, the northern limits of the Aztec state reached the River Lerma, in the vicinity of San Juan del Río, just under a two-hour drive north of Mexico City. That line, however, did not signify the limits of settled culture. The Tarascan territory of Michoacán and the princedoms of present-day Jalisco existed beyond Aztec control. Furthermore, the sites of La Quemada and Altavista in the present-day State of Zacatecas testify to sedentary culture deep in these northward areas before their recovery by un-subdued, nomad tribes. Although the Aztec capital had fallen in 1521 and its dominant hierarchies removed, the rest of what would become the viceroyalty had to be conquered stage by stage over a long period after tenacious resistance through hitherto un-subdued territory. The Spanish reached northward into Pueblo Indian territory in present-day New Mexico and south-eastward into the tropical forests of Yucatán, Chiapas, and Guatemala. A prime motive for northward expansion was the discovery of rich silver deposits in the centre-north and north.

New Spain remained for three centuries an imperial subordinate to metropolitan Spain and a part of the broader Hispanic Monarchy. As such it was subject to the general requirements of the Spanish Empire, an essential part of the regular supply of precious metals. The Mexican silver peso or dollar remained a prized item of international trade until well into the nineteenth century, despite the lamentable condition of the Mexican economy for three-quarters of that century.

The Spanish founded a chain of Hispanic cities in the aftermath of their conquests. Sometimes they were located, as new cities, in the heartlands of settled Indian areas, such as Puebla de los Angeles in 1531 and Guadalajara in 1542. Such cities became the centres of expansion for Hispanic culture among the surviving indigenous population. Cities like Guadalajara, Durango, and Zacatecas became the focal points for military expansion northward and for accompanying evagelization. Northward expansion ensured that the Viceroyalty of New Spain would consist of much more than the agglomeration of pre-Columbian polities. The Viceroyalty was subdivided into a number of ‘kingdoms,’ which were not distinct political entities but simply large administrative subdivisions: the principal of these was the Kingdom of New Galicia, with its capital in Guadalajara, seat of a Captain General, an Episcopal see, and the location of another Audiencia.

The Enlightenment, in particular, stressed the importance of rediscovering and conserving evidence of these pre-Columbian cultures. After Independence, this process continued but as part of the search for a distinct Mexican historical experience, that differentiated it from Europe and from the experience of other American countries. The foundation of the Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia (INAH) in 1939 represents a major advancement in the preservation and dissemination of that knowledge under the auspices of the modern state.

The makers of Mexican Independence, fought for in the years from 1810 to 1821, saw their country as the heir of both the Spanish viceroyalty and the pre-Columbian polities that had preceded it. The Mexican far north already extended into Upper California, New Mexico and Texas, territories which would be conquered by United States’ armies in the War of 1846–8. Like much of the north, they were only loosely connected to Mexico City. The formation of the Commandancy-General of the Interior Provinces in 1776 had been an attempt to resolve the problem of defence from the raiding parties of un-subdued Indians, described as ‘indios bárbaros,’ who occupied much of the territory that was also claimed by Spain. The colonial government's reluctance or inability to finance a military solution ensured that the Mexican Republic would inherit this problem after 1824. When the crisis over Texas secession broke in 1835–6, the Mexican government, burdened by large-scale colonial and post-colonial debt, was in no position to successfully respond to the pressure from the growing number of Anglo-Saxon settlers pushing in from Louisiana and elsewhere.

For Mexican nationalists of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, the Aztec inheritance became fundamental to any understanding of nationhood. Independence, in their view, reversed and avenged the Conquest. The argument that Mexico existed as a nation before the Spanish Conquest was designed to undermine the legitimacy of Spanish rule. As such, Mexico had a cultural and political identity distinct from Europe and a moral right to defend its sovereignty. This idea provided a platform for resistance to the French Intervention of 1862–7, which sought to re-establish European dominance, although in a different form. Liberal President Benito Juárez (1806–72), who championed resistance, had been born a Zapotec in the southern State of Oaxaca. Nevertheless, he identified with Cuauhtémoc, the last Aztec ruler, whom the Conqueror, Hernán Cortés, had put to death. The victorious Liberals of the Reform era (1855–72) portrayed the execution of the Austrian Habsburg Archduke Maximilian, who had presided over the Second Mexican Empire of 1863–7, as both the second War of Independence and the vindication of the Aztec resistance to Maximilian's ancestor, the Habsburg Emperor Charles V, in whose name Cortés had annexed pre-Columbian Mexico to the Spanish Monarchy.

The Revolution of 1910–40 reaffirmed the symbolism of republican nationalism inherited from the nineteenth-century. It became an essential part of the ideology of the monopoly ruling party, which had taken its initial form as the Partido Nacional Revolucionario (PNR) in 1929. The Aztec myth reinforced the ideological position of the revolutionary state. In fact, Octavio Paz (1914–98), awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1990, argued that the Aztec pyramid was the paradigm of the monopoly party state, which predominated in Mexico from the 1930s to the 1990s.

The Federal Constitution of 1917 continued, in part, the Liberal tradition of the 1857 Federal Constitution, but also responded to social pressures from peasants and urban workers concerning the questions of landownership and the rights and conditions of labor. It also sought to assuage nationalist concerns that subsoil deposits, namely minerals, oil, and gas, should not be controlled by private companies based in foreign countries. This Constitution is still in force and its centenary was commemorated in 2017. Current needs to increase investment in the energy sector, in order to stimulate productivity and expand the sphere of exploitation, may lead to a modification of the Constitution's provision and to the state monopoly of petroleum established by nationalization in 1938.

Plate 1.1 Sunday Afternoon Dream in the Alameda (1947). This segment of the mural painted by Diego Rivera (1886–1957) in the Hotel Del Prado, Mexico City, focuses on the first revolutionary leader, Francisco Madero. The mural satirically portrays Mexican history over the previous hundred or so years. It was an extraordinary balance of design and colouring. In the mural are the artist as a young man with Frida Kahlo, his painter wife, José Martí, the Cuban nationalist, Porfirio Díaz, and the overdressed skeleton ‘Caterina,’ one of the satirist, José Guadalupe Posada's notorious calaveras. Rivera and other muralists of his generation such as José Clemente Orozco (1883–1949) and David Alfaro Siqueiros (1896–1974), aligned with the revolutionary left and rejected the colonial era and capitalism. They projected a radical, Mexican nationalism, and reshaped history accordingly. Rivera, in particular, asserted a continuity between Aztec culture and postrevolutionary Mexico. Although the 1985 earthquake damaged the hotel, the mural was saved and relocated in the Diego Rivera Museum at the western end of the Alameda in Mexico City

Living with the United States

The loss of Texas in 1836 was followed by defeat in the War with the United States and the loss of nearly half of the Mexican Republic's claimed territory. The large numbers of indigenous Americans faced thereafter the US Army rather than the much weaker Mexican Army. Mexicans living north of the redrawn border henceforth became second-class citizens of a foreign power. Pushed off their land or confined to ‘barrios,’ they faced discrimination in a variety of ways. A Chicano movement would spring out of that experience during the 1960s, which would reaffirm the dignity inside the United States in both cultural and political terms. At the same time, substantial Mexican, other Latin American, and Caribbean migrations to the United States would alter the character of many cities, several of which, unlike Los Angeles or San Antonio, had never been Spanish-colonial or Mexican in the past.

By 1853, a new common border of 3,926 km cut across territory to the immediate south of San Diego down the Rio Grande Valley to the Gulf of Mexico at Matamoros, a vast area which had formerly been part of the same political entity. Ways of life often remained common, despite the linguistic difference on either side of the border. Loss of the Mexican Far North confirmed the shift in the balance of power on the North American subcontinent in favour of the United States. As this latter country grew in strength and influence in the decades following the Civil War of 1861–5, its perspective on the world differed widely from that of the Latin-American societies with which it shared the same continent. For the United States, the rest of the continent seemed a sideshow at best or at worst a nuisance factor, as its focus turned to Europe and Asia. As a twentieth-century world power, particularly after 1945, the North Atlantic and the Pacific became the key areas of policy attention. Despite periodic and often controversial interventions in Latin-American states, general lack of attention to the subcontinent explained frequent failures of comprehension. In particular, it explained why United States–Mexican relations remained so tetchy for most of the twentieth century. During the first two decades of the twenty-first century, they have continued to be so, further exacerbated by the issues of cross-border migration and drug trafficking.

Fundamentally, the Mexican–United States relationship involves disparities of power and wealth. These disparities lie behind many of the difficulties between the two countries. Despite parallels and similarities, Mexico and the United States operate in different worlds. Their international context and terms of reference are wide apart. It often seems to be the case that the two countries are not seriously thinking about one another. It can even be argued that Mexico spends more time thinking about itself – what it is, where has it come from, where it is going? Few Mexican newspapers have wide coverage of international affairs or even analyses of ongoing issues in the United States. Enrique Krause's comment that Mexico is symbolically an island is very much to the point. There are remarkably few Institutes of US Studies in Mexico and few historians specialise in US history – or European or Asiatic history for that matter. The Centro de Investigaciones sobre América del Norte, based at Mexico City's National University (UNAM), that also deals with Canada, as its name implies, is a notable exception. Lack of resources explains this in part but it is also the result of an absence of a tradition of doing so.

The War of 1846–8 is remembered in Mexico, although largely forgotten in the United States, due to the overriding importance of the Civil War in the years following it. In Mexico, a series of conferences in 1997–8 examined conditions in the country before 1846 and explored the reasons for the defeat. US pressures for further territorial concessions and for transit rights across Mexican territory, in the aftermath of loss of the Far North under the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo of 1848, provoked indignation and resistance in Mexico. Any discussion of the projected McLane–Ocampo Treaty of 1859, apparently conceding transit rights, still arouses rival nationalisms dating from the Conservative and Liberal struggles in the Civil War of the Reform (1858–61). The invasion of Mexican territory in 1847 and the later US occupation of Veracruz in 1914 continue to be excoriated by nationalists. At the harbour of Veracruz stands a monument dedicated to the cadets who fell resisting the invaders, and not far away, is a statue of Venustiano Carranza (1859–1920), leader of the Constitutionalist Revolution, who condemned President Woodrow Wilson's intervention as a violation of Mexican sovereignty. Defence of sovereignty has always been an earmark of Mexican foreign relations, whether in response to the United States or to the European powers.

Although Mexico and the United States have experienced two centuries of difficult relations, all is not a story of failure. Nineteenth-century Mexican Liberals regarded the US federal republic as their natural ally and model. Not even the shock of military defeat altered that perception. It characterised Juárez's dealings with Washington before, during, and after the US Civil War and during the French Intervention in Mexico. At that time, Mexico's diplomatic representative in Washington, Matías Romero (1837–98), established a tradition of friendship and cooperation over many years, beginning in 1859. The modern-day Presidents of both Republics usually meet frequently, and State Governors, particularly of the border states, are also in regular contact. A major difficulty continues to be the disproportionate position of the two countries, even though Mexico, the territorial size of France and Spain combined, is still a large country and the other third of the three North American countries. When President Ernesto Zedillo (1994–2000) visited the US White House in November 1997, for instance, his arrival had been overshadowed by the immediately preceding visit of the Chinese President, Jiang Zemin (who would subsequently visit Mexico). These two visits highlighted the dimensional difference between China and Mexico in terms of their ranking in US foreign-policy considerations. Repeated failure within US Government circles to understand Mexican problems and their historical roots in depth has repeatedly led to serious misunderstanding. President Felipe Calderón (2006–12) found himself obliged to protest repeatedly against disparaging remarks about Mexico coming from senior military and political figures in the United States.

President Carlos Salinas de Gortari (1988–94), highly controversial figure at the time, successfully attached Mexico to the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) in 1993, which originally consisted only of Canada and the United States. Although welcomed by business interests, this treaty, which came into effect in 1994, was criticised by nationalists and by the Left, for exposing Mexican agriculture, in particular, to US competition. Discussion still continues in both Mexico and the United States concerning the beneficial or deleterious results of this association. Mexican motives at the time of adhesion were both economic and political, connected as they were to Salinas de Gortari's policies of opening the economy and departing from the revolutionary inheritance of the decades from the 1910s to the 1940s.

The border question remains to bedevil Mexican–United States relations. Washington considers its southern border to be a security issue; the Mexican Government has a different perspective, because its prime concern is with the status and condition of border migrants. In 2015–16, nearly 60,000 men and women patrolled the borders of the United States, the majority of them located at the Mexican border. A Border Patrol was first established in 1924 and a special Customs and Border Patrol was set up in 2001. The latter's Mexican section was managed from El Paso (Texas). A marine unit patrols the Rio Grande. ‘Operation Gateway’ in 1994 started the process of building a fence to keep out illegal cross-border immigration across the Western California strip, which was relatively easy to cross. This fence started out at sea and ran for 19 km, terminating at the edge of the mountains, thereby forcing potential migrants to cross exposed mountains or deserts at great personal risk. Under President George W. Bush (2001–9), the Intelligence Reform and Terrorism Prevention Act of December 2004 provided for the increase of border agents to 20,000 staff by 2010. Early in 2013, 22,000 Agents were operating in cooperation with the National Guard, the Army, Homeland Security, and local agents.

The Secure Fence Act of October 2006 was designed to extend fencing by 1,100 km, equipping it with bright lights and survey cameras. Infra-red night readers, electronic sensors, and drones would follow. Border Patrol would use light aircraft, motorcycles, bicycles, and horse-riding to apprehend illegal migrants. Seen from the air, as a correspondent of the London Financial Times reported in January 2013, the border apparatus resembled more the divide between two hostile countries than one between two states at peace with one another. Private security firms and local vigilante groups also scanned the border zone for migrants. On the other hand, from Tucson, for instance, volunteers from church-based groups searched the desert trails to rescue dehydrated migrants overcome by heat.

Early cross-border migration resulted from the late-nineteenth-century land policies of the regime of Porfirio Díaz (1884–1911) and conditions in northern Mexico during the Revolutionary era after 1910. Much mid-century border crossing resulted from the US bracero program of 1942–64, which allowed Mexican ‘wet-backs’ in, at first during wartime to substitute for absent agricultural workers, particularly in California and Texas. Incomplete or failed agricultural-reform programs led to the virtual reproduction of Mexican villages north of the border and within US cities. Although scarcely regarded as such in US perspectives, this resettlement of home communities, chiefly from Jalisco, Michoacán, or Oaxaca, resembled the earlier migrations from English counties such as Essex and Suffolk, which reproduced themselves in New England. In January 1998, for example, Jalisco was reputed to be the Mexican State with the largest number of migrants: 1.5 million people originating from there lived mainly in California, Chicago, and Washington, DC. Such migrants were sending US$800 million back into the Jalisco economy. In the following two decades, Michoacán and Guanajuato reached and even surpassed Jalisco's total number of migrants. Leaving aside Oaxaca, we should note that none of these other three states were among the most impoverished or backward in Mexico.

The United States began to put a check on this transit in 1986 with the Immigration Reform and Control Act, which was widely regarded in Mexico as a form of punishment for the independent stance it was adopting on the Central-American crisis of the time. In 1994, the first administration of President Bill Clinton (1993–2001) attempted to stem migration by increasing patrols and constructing more barriers, and instituting ‘Operation Hard-Line’ in the following year. The incongruity of an immigrant nation such as the United States constructing a wall or barriers to keep out other immigrants, especially after the fall of the Berlin War in Europe in 1989 and the freeing of barriers across the former Soviet bloc to the outside world, was lost on no one inside Mexico.

The issue of a fence or wall between the two (otherwise friendly) republics had been a contentious from the 1990s. Illegal border crossings into the United States explained why. Several US presidential election campaigns, notably in 2016, made this a focus. Already in 1998, the United States had fixed a metal barrier across the Tijuana side of the Pacific Ocean beach, stretching 50 m into sea, to prevent migrants swimming into the United States. After inauguration, President Donald Trump declared his intention on 28 February 2017, to construct a wall along the entire 1,989 mile-border, for which Mexico would be required to pay. The Mexican government and opinion indignantly rejected such a notion.

Plate 1.2 The Border Wall between Mexico and the United States, 2017. As President-elect, Donald Trump stated on 11 January 2017: ‘we don't even have a border. It's like an open sieve.’ After inauguration, he declared in an address to both Houses of Congress, on 28 February: ‘We shall build a great – great – wall along our southern border.’ This border is, in many respects, artificial, because many families span the border and much transit and trade is conducted across it. The way of life in the borderlands is remarkably similar, despite differences of official language and government. Cross-border migration, in any case, has decreased since the US recession in 2008

Drug Trafficking and Money Laundering

A US Government Report in 2008 stated that three-quarters of the world's cocaine production was destined for the US market. Early in the following year, the Director of the FBI argued before the Senate Intelligence Committee that the activities of Mexican drug cartels represented the main criminal threat to the United States. The Director of the Central Intelligence Agency agreed, pointing out that divisions inside the Mafia had opened the way for Mexican cartels to gain control of the international drug trade. The FBI identified seven cartels which controlled distribution and described the Tijuana gang as the most dangerous, its alleged leader on the ‘most-wanted’ list in the United States.

A joint Mexican–US anti-narcotics strategy usually proved difficult to implement. Even so, the US Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) operated in Mexico in cooperation with reliable security officers.

The penetration of the gangs into political and security systems was the most serious revelation of the late 1980s and 1990s. This could reach the highest levels. General Jesús Gutiérrez Rebollo, head of anti-drug operations, was arrested in February 1997 for allegedly protecting one of the principal cartels. He was convicted of hoarding high-calibre weaponry and had apparently been involved in inter-gang warfare. He was sentenced in March 1998 to thirteen years’ imprisonment. Newspapers regularly reported the suspected drug involvements of political figures, such as state governors. In January 1998, the Procuraduría General de la República (PGR), the Attorney General's Office, ordered the arrest of the former Governor of Jalisco, Flavio Romero de Velasco (1977–83), on the grounds that while in office and afterward he had maintained contacts with narcotraficantes. He was sent to the federal maximum-security prison of Almoloya in the State of Mexico. One of his contacts allegedly transferred money from the Cayman Islands to Mexico and used front accounts for money-laundering. At that time, the PGR was also investigating the relationship of Mario Villanueva Madrid, Governor of the State of Quintana Roo, with the Ciudad Juárez Cartel, allegedly operating in the state and receiving cocaine from Colombia.

The murder rate in several states, notably Chihuahua and Sinaloa, escalated alarmingly through the 2000s. It had risen to 97 per 100,000 in the former state, which in 2010 had a total population of 3.2 million. Equally alarming has been the murder of journalists, of whom eighty-eight were killed between 2000 and 2015 and a further seventeen have disappeared. It is not known which group or agency has been responsible. The Mexico City newspaper, El Universal, on 1 January 2009, put the total number of gang-related murders during the previous year at 5,630, double the total for 2007; the PGR preferred the slightly lower figure of 5,376. Much of the violence in Sinaloa stemmed from the feuding between El Chapo gang and the Beltrán Leyva brothers. According to the PGR, gangs controlled around eighty municipalities, particularly in Michoacán and Tamaulipas. The number of kidnappings and extortions across the country was unknown. Drug cartels were often involved in such abductions, and allegations abounded that senior police officers had contacts with organised crime. In September 2014, forty-three trainee teachers were abducted and murdered in the district of Iguala in the turbulent State of Guerrero. It appeared that local authorities were involved in this. It has been suggested that the abduction may have been related to a struggle between two rival gangs for the control of opium and heroin production and the distribution routes, with Iguala strategically placed in that respect. The scandal put a blight on the administration of Enrique Peña Nieto, who had taken office in December 2012. Mexico City, which for a time gained a dubious reputation as ‘kidnap capital’ of Latin America, was later reputed to be the safest place in Mexico, when compared to drug-gang warfare in the high murder-rate states.

The Higher Profile of the Catholic Church

Salinas, in February 1993, re-established relations between the Mexican Republic and the Holy See. They had remained broken from the time of Juárez, in 1867, because the papacy had condemned the Reform Laws of 1855–60, which confiscated ecclesiastical properties, instituted civil marriage, and separated Church and State, and then had recognised Maximilian as Emperor of Mexico. Serious conflicts between Church and State in Mexico in 1873–6 and again in 1926–9 ensured that relations would remain interrupted. The Constitution of 1917, moreover, forbade the formation of clerical political parties and confined the Church to only a limited role in education.

Restoration of relations introduced a new dimension to national political life. It also allowed free expression of religious practice in public places, which had hitherto been frowned upon by the authorities and prohibited under the Reform Laws. Anti-clericals feared a recrudescence of ecclesiastical intervention in politics and civil affairs.

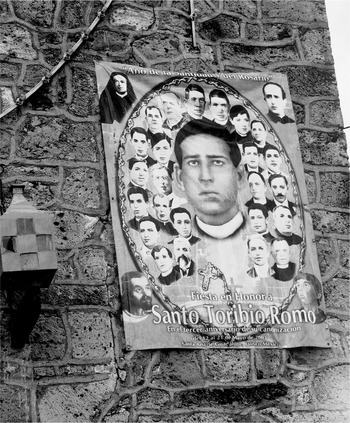

Inevitably, the Catholic hierarchy gained a higher profile after the restoration of diplomatic relations. Pope John Paul II (1978–2005) attributed great importance to the role of Latin America in the Catholic Church and to Mexico, given its history of anti-clericalism. John Paul's attention to Mexican issues and attempts to bolster the Mexican Church never wavered since his first visit shortly after his elevation. In 1992, he beatified the Martyrs of the Cristiada in a Solemn Mass of Christ the King in Rome. These were some twenty priests and lay people who had been murdered by sections of the Federal Army during its repression of the Jalisco countryside at the time of the Cristero Rebellion of 1926–9. None of the martyrs had actually taken part in the armed rebellion. The Polish pope canonised them in 2000. He regarded them as victims of the modern revolutionary state. The Mexican hierarchy sponsored the creation of a new shrine in the village of Santa Ana Guadalupe, not far from the great pilgrimage centre of San Juan de los Lagos in the Altos de Jalisco. Santa Ana had been the home of Padre (now Santo) Toribio Romo. The priest had been dragged out of hiding and shot dead at the age of twenty-seven in front of his sister by a Federal cavalry patrol on the lookout for priests and those working closely with them in defiance of government prohibition of the Catholic rites in 1927.

When the ruling Partido Revolucionario Institucional (PRI) lost power in the presidential elections of 2000, it was unclear at first which wing of the incoming Partido de Acción Nacional (PAN), which had a strong clerical element, would prevail. In the government of President Vicente Fox (2000–6), however, it quickly became evident that the business wing would take precedence over any attempted religious vindication, desired as it might have been by the Catholic Right.

Plate 1.3 The Shrine to the Martyrs of the Cristero Rebellion (1926–9) at Santa Ana de Guadalupe in the Altos de Jalisco. This is situated in the family home of the young priest, Toribio Romo, born in the district of Jalostotitlán in 1900 and murdered by federal forces in February 1928 during the repression of the Cristero Rebellion. Pope John Paul II canonised him as a Martyr of the Cristero War in 2000. His cult has spread across the US border, as he is unofficially venerated by migrants crossing into the United States, undiscovered by border patrols or lost in the desert, and by soldiers of Mexican origin surviving in the US interventions in Afghanistan and Iraq

The new administration made no attempt to undo the Reform Laws, despite attempts to denigrate the character and legacy of Juárez among the wilder elements of the PAN. The Mexican Church, for its part, continued to press for religious education in state primary schools, criticise secular education, denounce liberal sexual practices, and inveigh against controversial films – such as El crimen de Padre Amaro (2002) – or TV programs. At the same time, it pressed strongly for the canonisation of Juan Diego, the Indian declared to have had visions of the Virgin of Guadalupe in 1531. An outgoing prior of the Guadalupe religious community, however, had incurred Vatican criticism for expressing doubt late in 1999 at even the existence of Juan Diego, let alone the visions attributed to him.

In August 2002, Pope John Paul paid his fifth visit to Mexico. Upon arrival, President Fox made the unprecedented and controversial gesture of kissing the Pope's ring, an action which went against the entire juarista tradition. During the course of this visit, John Paul canonised Juan Diego and beatified two Zapotec Indians, who had been killed by other villagers for denouncing the celebration of clandestine rites to the Spanish colonial authorities. Even though large crowds welcomed the canonisation, both of these actions by the Pope received considerable criticism.

In a statement on 1 February 2004, the then Mexican Primate, Cardinal Norberto Rivera, who favoured a confrontational approach, declared that abortion and emergency contraception (the ‘morning-after pill’) constituted worse crimes than drug-trafficking. Rivera then attributed the ensuing outcry to the surviving current of anti-clericalism in Mexican society. He stated that packets of condoms should carry a health warning like cigarette packets. From there, he condemned Mexicans ‘who let themselves be seduced by liberal education,’ pitting himself, thereby, against the tradition of secular education derived from the Reform era. The emphasis continued to be on the lack of observance in Mexico of the moral precepts taught by the clergy. He blamed the ills of contemporary Mexico on homosexuals, feminists, and other ‘minorities.’ At the same time, individual bishops criticised the neo-liberal economic model promoted by the Salinas administration and continued thereafter. This gave the impression that Church leaders were attacking all forms of liberalism from both the Left and the Right at the same time, a tone consistent with that of the Holy See under John Paul.

Between 1950 and 2000, the proportion of self-declared Catholics in Mexico fell in relation to the overall growth of population. Similarly, the number of vocations also declined in relative terms, although it remained higher in Mexico than in Europe and the rest of Latin America. Out of an estimated 15,000 priests in a country of around 115 million inhabitants, some 2,500 were at the retiring age of seventy-five years in September 2003.

Despite the overriding problems of drug-trafficking, gun battles in major towns and cities, kidnapping, unexplained disappearances, the high murder rate in some parts of the country, the infiltration of town councils and state-governments by the Cartels, and the evidence of widespread poverty, the ecclesiastical hierarchy chose to single out same-sex relationships as their prime target. The Partido Revolucionario Democrático (PRD) Governor of the Federal District, Marcelo Ebrard (2006–12), secured from the Supreme Court acceptance of the principle that same-sex couples should enjoy the same civil rights as heterosexuals under the Constitution. Cardinal-Archbishop Sandoval denounced this decision in mid-August 2010, arguing that Ebrard and unnamed international organisations had bribed the Court. On 18 August, Ebrard sued the Archbishop for libel, but he refused to retract the statement.

During the 2010s, the issue of civil legitimisation of same-sex relationships rose to the surface in Mexico, where the national government after the return of the PRI to power in 2012 adopted a sympathetic position. In June 2015, the Supreme Court decided that same-sex unions were a basic human right under the terms of article 4 of the 1917 Constitution. President Peña Nieto and his Interior Minister, M. A. Osorio Chong, adopted this position at the federal level. Cardinal Rivera took this to be an attack on Christian doctrine. He authorised the organisation of a campaign, described as a Crusade, against same-sex unions on the grounds that they detracted from the sanctity of marriage, which could only be between a man and a woman. He encouraged protest marches in major cities. Pope Francis lent his support to this movement. Gay-Rights leaders regarded this campaign as tantamount to an incitement of hatred, if not violence, against their supporters. Rivera (who retired in 2017), at the same time, was declaring that God had already forgiven priests who had abused young people. A ‘Defenders of the Family’ protest march to the centre of Mexico City late in September 2016, which was supposed to mobilise a million people, turned out in reality to consist of much fewer than that.

A Perspective on the Present

There has always been a tendency both in Mexico and among Mexicanists to view the country in isolation from anywhere else. This amounts to an unnecessary distortion. While we certainly need to know more about the external contacts of pre-Columbian societies, which may well prove to be greater than has been supposed, post-Conquest Mexico has always been integrated into the wider world, although in varying degrees. Political, commercial, and cultural exchanges expanded considerably from colonial times. Despite some retrocession in the decades immediately following Independence, later nineteenth-century Mexico, especially after the construction of a railroad system, increasingly became integrated into the North Atlantic capitalist world of investment and infrastructure improvement. The Díaz régime intended that European investors should complement and compete with their US counterparts. The Revolution of the 1910s reacted against foreign penetration of the economy. On the other hand, President Calles (1924–8) faced the need to stabilise the economy and the financial system through re-establishing working relationships with foreign investors and their governments. In Chapters 8 and 10, we shall examine the very broad contacts contemporary Mexico has with the outside world – and on many levels – to mutual benefit.

During the 2000s, it became increasingly clear that the United States had lost the hegemony in Latin America, which had lasted from the end of the nineteenth century. We might regard the Spanish–American War of 1899–1901 over the independence of Cuba as the symbolic point of origin. By 2010, the loss of dominance had become irreversible, as Latin-American states, whether acting individually or through supra-national organisations took their own initiatives and made their own arrangements outside the area. Until the deep recession of 2015–16 and ensuing political crisis, Brazil appeared to be assuming the role of principal Latin-American state, outpacing Mexico for that role. The success or failure of Mexico's attempts after 2012 to recover influence both in Latin America and beyond may depend on several salient factors: the recovery of the energy sector and the diversification of investment, an ability to increase productivity, the broadening of the range of taxation, the adaption of technology across the manufacturing sector, the improvement of educational levels, the eradication of extreme poverty, and, last but not least, success in the struggle against the narcotics cartels.

The London-based LatAm Investor referred in its May 2017 issue to Latin America's ‘Golden Decade’, from 2003 to 2013, during which most countries increased their Gross Domestic Product and were able to reduce the scale of severe poverty. This was also the decade in which China substantially expanded its role in the subcontinent, at a time of declining US interest in the area. China replaced the United States as the main trading partner of Brazil, Argentina, Chile, and Peru. Such Foreign Direct Investment in Latin America, principally concentrating on infrastructure and energy, considerably reversed prior US economic hegemony, which had superseded British predominance during the 1930s and 1940s. Chinese investments were linked to commodities and loans. Mexico, during this ‘Golden Decade’ remained largely an exception to the trends set in South America, wary of Chinese competition in the US market. After 2013, however, the main Latin American economies, that had generated so much optimism among foreign investors, passed through difficult periods. Mexico was seriously disadvantaged by the decline of world oil prices, which did not begin to rise again until 2016. This, combined with deepening uncertainty with regard to relations with the United States from that year onward, led to currency instability and investor reticence. Chinese interest in Latin America, however, did not recede, and by 2017 was clearly intending to include Mexico.