Introduction

Auditory verbal hallucinations (AVH) or ‘hearing voices’ are one of the most frequent features of psychosis (e.g. Clark et al., Reference Clark, Waters, Vatskalis and Jablensky2017). For many people they can be highly distressing, disorienting and persistent. Alongside anti-psychotic medication and family interventions, cognitive behavioural therapy for psychosis (CBTp) is a recommended treatment in the UK for AVH (NICE, 2014). However, meta-analyses of CBTp have indicated at best small-to-modest effects on symptoms, and these are considerably diminished with blinding (Jauhar et al., Reference Jauhar, McKenna, Radua, Fung, Salvador and Laws2014). It has been argued that CBT for psychotic symptoms may be more effective when one tailors treatment to specific psychotic experiences (Lincoln and Peters, Reference Lincoln and Peters2019; van der Gaag et al., Reference van der Gaag, Valmaggia and Smit2014). The findings of studies that have examined the effects of targeted brief interventions on sleep, worry and paranoia could be considered consistent with this argument (Foster et al., Reference Foster, Startup, Potts and Freeman2010; Freeman et al., Reference Freeman, Sheaves, Goodwin, Yu, Nickless, Harrison and Espie2017). Similarly, group-based CBT, web-based and self-help tailored interventions for distressing voices have also been found to be successful in decreasing frequency, severity and negative perception of voices (Gottlieb et al., Reference Gottlieb, Romeo, Penn, Mueser and Chiko2013; Penn et al., Reference Penn, Meyer, Evans, Wirth, Cai and Burchinal2009); and reported feelings of being controlled and distressed by voices (Chadwick et al., Reference Chadwick, Strauss, Jones, Kingdon, Ellett, Dannahy and Hayward2016; Dannahy et al., Reference Dannahy, Hayward, Strauss, Turton, Harding and Chadwick2011).

There are a range of reasons why ‘standard’ CBTp may not lead to the most effective outcomes for managing voices (McCarthy-Jones et al., Reference McCarthy-Jones, Thomas, Dodgson, Fernyhough, Brotherhood, Wilson, Dudley, Hayward, Strauss and McCarthy-Jones2014a,b,c; Thomas, Reference Thomas2015). Four possible reasons are: (i) that CBT-based approaches are simply ineffective interventions for psychosis; (ii) that CBT models, in primarily focusing on cognitive appraisals, may not have been sufficiently adapted to treat psychosis specifically; (iii) that the treatments deployed have not been informed by the most recent psychological models of specific symptoms such as AVHs; and (iv) that different subtypes of AVH may exist, requiring a variety of different treatment strategies. In support of this line of argument, voices are a highly heterogeneous phenomenon (Nayani and David, Reference Nayani and David1996; Woods et al., Reference Woods, Jones, Alderson-Day, Callard and Fernyhough2015), suggesting that a ‘one size fits all’ approach is unlikely to be successful. On the other hand, various attempts at subtyping voices in psychosis have been made in the past without enduring success (see, for example, Stephane et al., Reference Stephane, Thuras, Nasrallah and Georgopoulos2003), and many voice-hearers will possess multiple apparent subtypes or clusters of voice characteristics at the same time (McCarthy-Jones et al., Reference McCarthy-Jones, Thomas, Dodgson, Fernyhough, Brotherhood, Wilson, Dudley, Hayward, Strauss and McCarthy-Jones2014a,b,c).

Notwithstanding these concerns, it is an open question as to whether voice-hearers themselves may benefit from a therapeutic approach which is tailored to the specific phenomenology of the voices they experience (Smailes et al., Reference Smailes, Alderson-Day, Fernyhough, McCarthy-Jones and Dodgson2015). A review by the International Consortium on Hallucinations Research (McCarthy-Jones et al., Reference McCarthy-Jones, Thomas, Dodgson, Fernyhough, Brotherhood, Wilson, Dudley, Hayward, Strauss and McCarthy-Jones2014b) outlined five different potential subtypes which may be suited to different kinds of tailored intervention: inner speech voices (postulated to result from the misattribution of ordinary inner speech to an external agent); hypervigilance voices (resulting from a biased attention to environmental stimuli); memory voices (the result of intrusions from traumatic memory); voices reflecting temporal lobe epilepsy, and those reflecting sensory deafferentation (such as hearing loss). While the latter two are often more suited to neurology-based interventions, the first three are grounded in contemporary cognitive models of AVH. This arguably makes them particularly suited to tailored psychoeducation and cognitive therapy (Smailes et al., Reference Smailes, Alderson-Day, Fernyhough, McCarthy-Jones and Dodgson2015).

A treatment approach and manual was developed within Early Intervention in Psychosis (EIP) services and was based on current theoretical models of voice-hearing and the voice subtypes described above. It represents refinements of existing psychoeducation and coping strategies used in CBTp and related mental health problems (e.g. post-traumatic stress disorder). Also, the manual is delivered via a tablet computer (in this case, an iPad), for joint use of therapist and client in the therapy session. This allows clinicians to use prepared videos and other types of media to demonstrate complex psychological ideas and phenomena, and to help service-users to practise coping strategies and carry out behavioural experiments to test the reality of their experiences.

The present study aimed to investigate the acceptability to service-users and staff of the treatment manual as a part of routine care within a mental health trust, across a range of services (including EIP teams, Community Mental Health Teams, and in-patient care). Of particular interest was whether an intervention developed in EIP services would be acceptable to people in other settings, who may have already developed clear ideas about the nature and cause of their experiences. A secondary objective was to use this study as a way of identifying the most appropriate outcomes for a full-scale trial of the therapeutic package, both for primary outcomes (relating to psychosis symptomatology specifically) and secondary outcomes (relating to beliefs about voices, depression, anxiety and general functioning). Voice-hearers using the manual with a clinical psychologist or psychological therapist were invited to complete an assessment session on entrance to the study and after 10 sessions of using the manual. As this was a feasibility study, we did not test hypotheses about the effect of the new treatment in relation to a control arm; rather, our aim was to gather as much relevant data as possible to facilitate a full examination of treatment effectiveness in future.

Method

Participants

Twenty-four participants (16 males, mean age 29.79 years, SD = 7.79) were recruited from NHS trusts in the North of England. Therapists from various service settings – including in-patient wards, Community Mental Health Teams (CMHTs) and EIP services – were asked to consider any referrals they received where they were likely to work on voice-hearing during the first 10 sessions of therapy. All the therapists were either clinical psychologists or psychological therapists, who were either CBT trained or working towards accreditation (with post-qualification experience ranging from being newly qualified to 25 years of experience). Most of the therapists worked in EIP, but two worked on wards (one acute, one rehabilitation) and one in a CMHT. Eligible participants met the following inclusion criteria: (i) considered suitable for psychological therapy by the referring clinical team; (ii) report experiencing AVH at least once per week; (iii) aged over 18 years; and (iv) a good understanding of English. Exclusion criteria were (i) complex problems that would make voice-hearing unlikely to be a target of therapy in six of their first 10 sessions of therapy (e.g. a complex delusional system); (ii) presence of acute illness; and (iii) presence of major substance misuse issues. Participants received a gift voucher for each assessment session they completed.

Design

A single-arm trial design was used to investigate treatment feasibility and acceptability plus relevant symptom changes between baseline and post-treatment.

Treatment manual

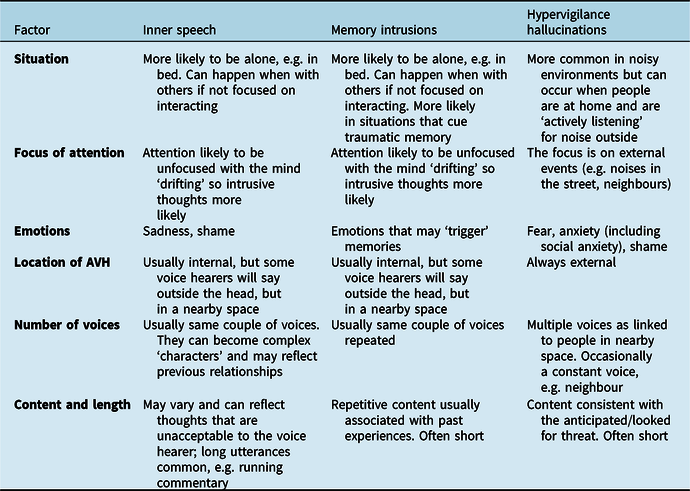

A text copy of the manual is available at https://tinyurl.com/s48v8yu. Therapists were provided with a traditional paper-based manual as well as an iPad, which contained the treatment manual. The manual was divided into four sections, with an assessment section to help identify the subtypes of voices, and treatment sections relating to the specific subtypes, i.e. Inner Speech-AVH (IS-AVH), Memory Based-AVH (MB-AVH) and Hypervigilance-AVH (HV-AVH). Table 1 shows the assessment summary table, which tried to help therapists to identify different subtypes of voices. Focus of attention was a key dimension, with IS-AVH and MB-AVH being viewed as more likely when attention was drifting and intrusions were more likely. In contrast, HV-AVH were more likely when attention was focused externally to detect threat. Each treatment section included guidance on approaches to treatment, psychoeducation and suggested interventions.

Table 1. Assessment summary table for subtypes of voices

Embedded in the iPad software were video clips explaining key concepts related to hallucinations and demonstrations of cognitive processes that play a role in the onset of hallucinations. The IS-AVH section contained psychoeducation materials that helped the therapist and service user explore whether processes related to inner speech could be playing a role in their voice-hearing, and also included suggestions about how to increase control over voices (e.g. engaging in other activities that would recruit inner speech so that a voice may be interrupted; learning how to control the ‘sound’ of a voice using mental imagery, so that it was perceived as being less threatening and less powerful). In contrast, the MB-AVH module contained psychoeducation materials about how trauma memories often lack contextual cues (Ehlers and Clark, Reference Ehlers and Clark2000), making it more likely that later re-experiencing of these memories might result in them feeling as they are happening in the ‘here and now’, and so they are experienced as voices. This module encouraged the use of fewer avoidance strategies (e.g. it encouraged replacing thought suppression with strategies such as distraction) and the reappraisal of traumatic experiences, in an attempt to reduce the frequency of and the distress elicited by these AVH. In the HV-AVH module, psychoeducation focused on how strong predictions and expectations can shape perception (as in recent predictive processing models of hallucinations, e.g. Corlett et al., Reference Corlett, Horga, Fletcher, Alderson-Day, Schmack and Powers2019), using examples such as binocular rivalry, the McGurk effect (McGurk and MacDonald, Reference McGurk and MacDonald1976), and Simons and Chabris’s (Reference Simons and Chabris1999) demonstration of selective attention. The module encouraged the use of strategies to reduce arousal and perceived threat (e.g. discussing concerns about one’s safety with trusted others; improving sleep through better sleep hygiene; testing out maladaptive safety behaviours) in an effort to reduce the frequency of HV-AVH.

Therapists were encouraged to tailor their use of the iPad to the service-user’s needs. This design ensured that participants received adequate exposure to the manual in therapy sessions to determine its acceptability, but also allowed clinicians freedom to address problems that the manual was not intended to address (e.g. relationship difficulties). Therapists were offered a day of training on the novel aspects of the manual (covering the subtyping and theoretical background) and then monthly supervision for 90 minutes in small groups of two to three therapists.

Measures

Acceptability of the manual was assessed at follow-up using the following scales:

-

i. A revised version of the Satisfaction with Therapy and Therapist Scale (STTS; Oei and Green, Reference Oei and Green2008; Oei and Shuttlewood, Reference Oei and Shuttlewood1999). The STTS is an 11-item scale consisting of two factors corresponding to satisfaction with therapy and therapist independently. The scale has shown strong validity and reliability in multiple samples (e.g. mean Cronbach’s alpha = .90; Oei and Shuttlewood, Reference Oei and Shuttlewood1999).

-

ii. A customised schedule examining the acceptability of the use of an iPad in therapy sessions and participant’s views on the therapy as a whole. The schedule involved eight Likert-scale questions completed by the participants, followed by five structured interview questions, delivered by the assessor. The questions used on the scale were developed by the research team following a prior service evaluation and consultation with clinicians and service users using a pilot version of the iPad package. Participants were given the following instructions: These questions are about how you felt about the iPad, which the therapist used in some sessions with you. When the questions ask about the ‘videos etc.’ we mean any videos, sound recordings, or pictures that were shown to you using the iPad. The Likert items covered different aspects of the iPad therapy, such as The videos etc. made me curious about how my mind works and The iPad stopped me from developing a good relationship with the therapist. Participants then rated their agreement on a 5-point scale, ranging from ‘strongly disagree’ (1) to ‘strongly agree’ (5). We also asked participants for any general comments they might have had about the experience of using the manual.

The following measures were included to monitor symptom change and assess their feasibility as primary outcome measures in an eventual full trial:

-

i. The Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale for schizophrenia (PANSS; Kay et al., Reference Kay, Fishbein and Opler1987). The PANSS has been used in multiple studies to assess psychotic experiences. It is delivered as a clinical interview and provides 35 ratings for individual symptoms, covering positive symptoms, negative symptoms and general functioning. Ratings are made on a 7-point basis from absent (1) to extremely severe (7). Of specific interest to the present study were ratings for items P3 (‘Hallucinations’) and P1 (‘Delusions’). While the former would be expected to change for a voice-specific intervention, the latter would not necessarily change; as such, examining change for both allowed us to explore potential symptom-specific effects.

-

ii. The Psychotic Symptom Ratings Scale (PSYRATS; Haddock et al., Reference Haddock, McCarron, Tarrier and Faragher1999). This scale has been used extensively as an outcome measure on research on CBTp in general, and auditory hallucinations in particular (Craig et al., Reference Craig, Rus-Calafell, Ward, Leff, Huckvale, Howarth and Garety2018; Tarrier et al., Reference Tarrier, Lewis, Haddock, Bentall, Drake, Kinderman and Benn2004). In contrast to the PANSS, it provides detailed ratings of hallucination and delusion characteristics according to subscales of 11 and 6 items, respectively (again allowing for assessment of symptom-specific effects). Within the PSYRATS, items specifically relating to distressing voices are often picked out as important outcomes in therapy for voices (see, for example, Hayward et al., Reference Hayward, Jones, Bogen-Johnston, Thomas and Strauss2017). Here we report distress scores (summing items 6, 7, 8, 9 and 11 on the scale) based on a recent 4-factor model of the scale (Woodward et al., Reference Woodward, Jung, Hwang, Yin, Taylor and Menon2014).

The following measures were included to monitor other changes relevant to patient functioning and to assess their feasibility as secondary outcome measures in an eventual full trial:

-

i. The Beliefs About Voices Questionnaire – Revised (BAVQ-R; Chadwick et al., Reference Chadwick, Lees and Birchwood2000). The BAVQ-R is often used in CBT work with voices as means of assessing participants’ secondary appraisals of their voice-hearing experiences. It produces five subscale scores: three relating to perceived properties of the voice itself (malevolence, benevolence and omnipotence) and two relating to the voice-hearer’s response to the voices (emotional resistance and emotional engagement). Only the items relating to properties of voices (benevolence, malevolence and omnipotence) were used in the present analysis (items 1–18 were used).

-

ii. The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS; Zigmond and Snaith, Reference Zigmond and Snaith1983). The HADS is a commonly used measure of anxiety and depression in clinical and non-clinical studies (e.g.,Haj et al., Reference Haj, Gallouj, Dehon, Roche and Larøi2018; Larøi et al., Reference Larøi, Bless, Laloyaux, Kråkvik, Vedul-Kjelsås, Kalhovde, Hirnstein and Hugdahl2019). It consists of 14 items that participants rate on a Likert scale ranging from 0 to 3. Higher scores indicate greater levels of depression and anxiety.

-

iii. The Manchester Short Assessment of Quality of Life (MANSA; Priebe et al., Reference Priebe, Huxley, Knight and Evans1999). The MANSA is a brief tool that assesses overall quality of life for patients in clinical studies. The 25-item assessment consists of three sections relating to personal details consistent over time, personal details varying over time and satisfaction with various domains of life. MANSA scores range from 1 (couldn’t be worse) to 7 (couldn’t be better). The instrument shows satisfactory psychometric qualities (e.g. Björkman and Svensson, Reference Björkman and Svensson2009; Eklund and Sandqvist, Reference Eklund and Sandqvist2006).

Procedure

After providing informed consent, participants completed the first assessment. Both assessments measured various aspects of the service-user’s experiences of voice-hearing (e.g. frequency, distress, location, disruption to life), participants’ beliefs about their voices (e.g. to what extent voices are powerful), as well as mood problems and quality of life. The second assessment was after the participant had completed 10 sessions of therapy (i.e. approximately 10 weeks later) and included the custom schedule (assessing manual acceptability) and therapy satisfaction measures. All assessments were conducted in either participants’ homes, or at their usual NHS clinic. PANSS and PSYRATS were conducted by trained raters (D.S., J.D., C.M. and F.R.). Initially, the study was designed so that participants would complete an additional assessment at 22 weeks (i.e. approximately 12 weeks after completing 10 sessions of therapy). However, for practical reasons, the study was subsequently amended so that this 22-week assessment was removed from the testing protocol.

Analysis plan

Prior to analysis, all quantitative variables were assessed for normality using Shapiro–Wilk tests. As a large number of the outcome variables were significantly non-normal, a non-parametric approach was adopted. Mann–Whitney U-tests were used to compare baseline symptom scores between participants who did and not complete the intervention while Wilcoxon tests were used to analyse baseline and post-treatment symptom scores for participants completing treatment. General comments made by participants about the intervention were also recorded and are included here for descriptive purposes, but were not analysed further. All analyses – including calculation of effect sizes – were conducted in jamovi (The jamovi project, 2020).

Results

Overall, 24 participants consented to take part in the study and were treated by 11 different therapists. Figure 1 shows that four participants received the baseline assessment but after further clinical sessions, the therapist and participant decided to prioritise treatment for different problems (e.g. health anxiety, gambling addictions, etc.). Three participants completed the intervention but did not complete the follow-up assessment. One participant stopped the treatment as they found it unhelpful and the treatment was continued using a cognitive analytical therapy approach. Another three participants did not complete the intervention and did not state their reasons for doing so. On average, clinicians reported using the manual in the second or third session that they saw a client, and they then went on to use it for an average of 7.83 sessions (SD = 3.71, range = 5–15).

Figure 1. Completion flow diagram for participants recruited, receiving treatment, and completing therapy with the iPad manual.

Treatment acceptability

Table 2 displays the mean scores for therapy satisfaction (STTS) and acceptability scores from the custom schedule tailored for the iPad intervention. Mean scores were high for every item of the schedule, indicating good satisfaction and acceptability of the treatment. When reverse-keyed items were recoded, overall mean total scores were 49.60 (SD = 3.82) for satisfaction (out of a possible score of 55) and 35.08 (SD = 3.80) for acceptability (out of a possible score of 40). Qualitative feedback from participants was generally very positive with regard to therapy as a whole and use of the iPad, although at least one participant struggled with the explanation that their voices could be attributed to their own thoughts (see Table 3).

Table 2. Mean satisfaction with treatment (i) and acceptability of iPad use (ii) from participants completing follow-up (n = 12)

STTS, Satisfaction with Therapy and Therapist Scale.

* Reverse-keyed items. Response options for both scales ranged from ‘strongly disagree’ (1) to ‘strongly agree’ (5).

Table 3. Example qualitative feedback from participants completing the therapy intervention

Group differences in completion

To explore potential reasons for participants completing participation (versus those who did not), Mann–Whitney U-tests were run to compare the two groups of participants on the main outcomes from the baseline assessment. The two groups differed for two outcomes only: PANSS Positive Subscale (U = 24.50, p = .011, d = 1.17) and PANSS P1 Delusions score (U = 26.50, p = .012, d = 1.24). Non-significant trends were also observed for PSYRATS Delusions total score (U = 38.50, p = .078, d = .78), PANSS total score (U = 35.50, p = .064, d = .97) and BAVQ Omnipotence Score (U = 31.50, p = .064, d = .92). See Supplementary material (Table S1) for a complete set of data on how the two groups differed. For each of the observed differences, non-completion was associated with more severe symptoms, particularly for delusions. Measures of voice-hearing were very similar between completers and non-completers. Although the relative frequencies were too small to assess statistically, it was also notable that out of the six participants who were recruited from CMHTs settings, four did not complete the intervention. In contrast, 13/17 participants drawn from EIP settings completed the treatment sessions (of whom 10 went on to provide follow-up data).

Within-subject changes in candidate primary and secondary outcome variables

All of the potential primary and secondary variables were feasible to administer in the time allowed for assessment (60–90 min). Table 4 displays the mean scores and percentage change for participants who completed therapy and the follow-up session. In general, symptom scores reduced, and percentage changes were particularly evident for primary outcome variables, i.e. auditory hallucinations scores (PSYRATS-AH and PANSS-P3) and secondary outcome variables, i.e. belief in the omnipotence of voices (BAVQ-O), depression (HADS) and general life satisfaction (MANSA). Significant differences were observed for PSYRATS-AH (W = 70.50, p = .015) and PSYRATS Distress (W = 43.50, p = .015) specifically. This contrasts with generally smaller effects on delusions: the PANSS-P1 score for delusions actually increased by 3%, although in practice this amounts to less than one unit of change on the 7-point scoring for delusions (and still in the absent–minimal range).

Table 4. Mean within-subject changes in symptom outcomes for completing participants (n = 12)

* Denotes n = 11 for BAVQ scores (due to missing data). Denominator for % change = maximum score on scale. AH, auditory hallucination.

Discussion

This study investigated the acceptability and feasibility of a novel treatment approach to voice-hearing that works with three voice subtypes: inner speech, hypervigilance and memory-based voices. The aim of the treatment is to provide meaningful alternative explanations of the experience and coping strategies guidance tailored to experiences of service-users (Smailes et al., Reference Smailes, Alderson-Day, Fernyhough, McCarthy-Jones and Dodgson2015).

In two assessment sessions, measures were taken of symptom change in the severity of auditory hallucinations, beliefs about voices, depression and general life satisfaction, along with general treatment satisfaction and acceptability at the follow-up. Scores for mean satisfaction with treatment and acceptability suggested that, for most service-users, this intervention was acceptable and did not impair the development of a strong therapeutic relationship. The changes in the outcome measures for auditory hallucination scores suggested that some people may have benefited from this approach, while general life satisfaction scores also improved. However, the lack of a control group prohibits any inferences about therapeutic change.

High discontinuity and participant drop-out rates are common in CBTp research (Lincoln et al., Reference Lincoln, Rief, Westermann, Ziegler, Kesting, Heibach and Mehl2014; Tarrier et al., Reference Tarrier, Yusupo, Kinney and Wittkoski1998). From the originally recruited sample, only half of the participants completed the follow-up assessment (n = 12). However, 15 of 19 participants who started the treatment completed it: four participants did not start the treatment, as further assessment indicated that therapy should be focused on problems other than voice-hearing. This suggests that, in future trials, acceptance into the study should only be considered following a clear assessment of therapeutic needs and participant goals. Of the four people who did not complete the intervention, three remained engaged with a psychological therapy and one discontinued psychological therapy while remaining engaged with the care team. An additional three people completed the intervention but were then lost to follow-up.

Scores at baseline assessment suggested that completers (compared with non-completers) had slightly higher scores on voice-hearing measures; however, participants who did not complete the intervention had much higher scores on measures of delusions. It has been previously shown that high delusional thinking in schizophrenia is associated with increased drop-out rates in psychological treatment intervention (Jorgensen et al., Reference Jorgensen, Munk-Jorgensen, Lysaker, Buck, Hansson and Zoffman2014). This might suggest that the intervention was more acceptable to voice-hearers where delusions were not present. It is unclear how much the delusions were specifically linked to the explanation for the voices, but it is possible (or likely) that where there is a strongly held belief about the origin of the voice, the ability to consider alternatives is reduced. This in turn could also limit the extent to which individuals are willing to take on new interpretations, or able to absorb normalising information from psychoeducation (McGowan et al., Reference McGowan, Lavender and Garety2005; Messari and Hallam, Reference Messari and Hallam2003).

Participants from EIP services were more likely to complete the intervention, with 12 of 17 completing follow up assessment (71%), compared with only two of six participants from CMHTs. The intervention was developed in EIP services, and may be more appropriate for this client group, as people may have not developed fixed ideas or delusions about the origin of their voice-hearing experiences. Hallucinations can be very common in first-episode psychosis (with prevalence rates of up to 75% reported; Mbewe et al., Reference Mbewe, Haworth, Welham, Mubanga, Chazulwa, Zulu, Mayeya and McGrath2006; Rajapakse et al., Reference Rajapakse, Garcia-Rosales, Weerawardene, Cotton and Fraser2011) and evidence suggests that hallucination severity is associated with likelihood of disengaging from EIP services (Solmi et al., Reference Solmi, Mohammadi, Perez, Hameed, Jones and Kirkbride2018). Auditory verbal hallucinations are particularly associated with risk of developing psychotic disorders in clinically high risk groups (Niles et al., Reference Niles, Walsh, Woods and Powers2019) and the intensity, frequency and duration of hallucinations are key factors in the screening tools for ARMS (Yung et al., Reference Yung, Yeun, Mcgorry, Phillips, Kelly, Dell’ollio and Buckby2005) and EIP services (Kay et al., Reference Kay, Fishbein and Opler1987). Therefore, an intervention like MUSE, being targeted at voices at an early stage (i.e. ARMS and EIP services), may be key to preventing the transition to psychosis and the development of other psychotic symptoms. In contrast, longer term voice-hearers in CMHT settings may have other, more complex therapeutic needs: interventions that focus on reducing distress and improved coping may be more promising approaches for people who have experienced voice-hearing for longer (e.g. Hayward et al., Reference Hayward, Jones, Bogen-Johnston, Thomas and Strauss2017).

Qualitative feedback from the participants also fits the above pattern. Service-users were generally positive about the intervention and found it helpful. Whilst one participant rejected the idea that the voices could be their thoughts, others found this alternative helpful, even if the content was uncomfortable, for example ‘if angry, these [the voices] are still my thoughts’. Finding a plausible alternative that helps reframe an experience can be a powerful therapeutic intervention, for example of panic symptoms (Clark, Reference Clark1986). When working with people experiencing psychosis, providing alternative explanations can be challenging, but helpful for some people. For example, a voice saying ‘you are worthless’ could be seen as powerful confirmation of poor self-worth if experienced as coming from a powerful and alien source (Birchwood et al., Reference Birchwood, Mohan, Meaden, Tarrier, Lewis, Wykes and Michail2018). If the voice is seen as an intrusive thought linked to a past abusive experience, then it can become a distressing echo of past trauma, without confirming anything about current self-worth.

This study has several limitations. First, the study may have benefited from additional measures of feasibility beyond the number of participants who completed the intervention. Second, given the study’s focus on acceptability and feasibility, no conclusions can be drawn about the efficacy of the intervention. A further study is required with a larger sample size, a control arm and blinding of assessors, to understand if the intervention is more effective than current approaches. The completion rate for the study was 12 of 24 people who consented to participate, whilst 15 of 19 who began the intervention completed it. Four participants who consented to the study did not begin the treatment as further assessment by the clinician suggested other target problems. This suggests that participants may have been invited to participate prematurely, and that they could have benefited from a more thorough assessment and conversation with their therapist prior to participating. Three participants completed the intervention but could not be contacted for the follow-up assessment. These participants were from EIP services and their loss to the study may reflect the challenges in working with young people experiencing their first episode of psychosis, particularly around individuals’ self-organisation and mobility. Finally, non-completion of the intervention appeared to be linked to high scores on delusion measures at entry to the study and being seen within a CMHT setting. The small samples meant we were unable to investigate whether these are independent factors, thus limiting the ability to draw conclusions about who the intervention may be appropriate for. Although certain aspects of this intervention may prove valuable for individuals with longer-term voice-hearing, other approaches may be more promising, such as interventions that focus on changing the relationship between the voice-hearer and the voice (Hayward et al., Reference Hayward, Bogen-Johnston and Deamer2018). Finally, while we intended to measure how therapists/service-users used the manual using an adherence checklist, which would have provided information about how often only specific subsections were accessed for a service-user and how often multiple subsections were accessed for a service-user, clinicians found it difficult to complete these adherence checklists from memory, and so we do not have sufficient data from these checklists to analyse. Thus, we are not able to provide evidence showing that clinicians typically accessed resources related to a subtype of voice-hearing for each service-user, which is an important limitation, as this evidence would have demonstrated the value of adopting a subtyping approach. Anecdotal evidence from supervision sessions suggests that the manual may have been used in this way, with clinicians using the manual in non-linear ways that were tailored to individual service-user’s needs, but in a manner that reflected them targeting a specific subtype of voice-hearing. A key goal of future research with this intervention will be to develop a more effective way of measuring how the manual is used in therapeutic sessions. All this being said, the intervention described here appears to be acceptable and feasible, when used with voice-hearers recruited from EIP settings. It may offer a novel approach to helping voice-hearers, when targeting the cognitive processes underlying their AVH seems to be a priority rather than addressing the relationships people have established with their voices.

Future research should consider firstly whether targeting the intervention at a specific symptom and early stage of voice hearing can increase effectiveness and secondly, whether accessibility can be increased either through equivalent outcomes from a shorter intervention or through the treatment being delivered by less highly trained staff, e.g. newly qualified nurses or psychology graduates. Effectiveness can be addressed through a pilot randomised controlled trial, with PSYRATS-AH as a primary outcome variable, and with BAVQ, HADS and MANSA as secondary variables. The higher non-completion rates in CMHTs participants suggest that this should be run primarily – if not exclusively – within EIP services. Informal feedback from clinicians who participated in the study suggested that the intervention could be particularly useful for people experiencing an At-Risk Mental State for psychosis (Yung et al., Reference Yung, Yeun, Mcgorry, Phillips, Kelly, Dell’ollio and Buckby2005), providing a compelling explanation for their experiences soon after they have begun. The intervention tackles issues such as why inner speech may be experienced as voices and suggests mechanisms that can reduce the frequency of AVH. Earlier access to these ideas could prevent the vicious circle of increasing experience of voices, a search for an explanation of the experience, and likelihood of using unhelpful coping strategies, such as cannabis and avoidance, which is often seen at presentation to EIP services (e.g. Howard et al., Reference Howard, Forsyth, Spencer, Young and Turkington2013; Morrison, Reference Morrison1998). A further feasibility trial is planned with people who have an At-Risk Mental State for psychosis, to determine whether the intervention is acceptable to this group of service users.

The intervention has been developed with a modular structure, including embedded videos of key concepts, which could make it easier for staff who are not qualified psychological therapists to deliver the intervention, thereby increasing accessibility. The growing demand for psychological therapies for people experiencing psychosis (NICE, 2014), without an accompanying increase in workforce, reduces access to the interventions. Increasing the range of staff who could deliver these interventions can potentially widen the access, but it needs to be noted that there are substantial challenges in enabling other staff to deliver interventions, including competing time demands and access to supervision (Garety et al., Reference Garety, Craig, Iredale, Basit, Fornells-Ambrojo, Halkoree and Waller2018). Further research is planned to investigate whether the intervention could be used effectively by newly qualified nurses and care co-ordinators, in order to reduce the bottleneck placed on many services with substantial waiting lists for psychotherapeutic intervention.

Overall, the study suggests that the intervention is acceptable to people in EIP services, particularly for those who have low scores on delusions. Targeting psychological interventions at specific experiences, in the context of relevant and accessible psychoeducation and practical management strategies, may represent a promising avenue for future therapeutic interventions in the early stages of psychotic experiences.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1352465820000661

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Jenna Moffat and Simon McCarthy-Jones for their work on the first version of the treatment manual. They would also like to thank the therapists, Charlotte Aynsworth, Nicola Barclay, Marsha Cochrane, Steph Common, Sue Gordon, Carolyn John, Anna Luce, Tom Reeves, Christina Thompson and Steve Williamson.

Financial support

This research was supported by the Wellcome Trust (grants WT098455, WT108720 and WT209513).

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interests to declare.

Ethical statement

Ethical approval for this study was given by NRES Committee Yorkshire and the Humber – South Yorkshire (REC reference number: 14/YH/1130). The authors have abided by the Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct as set out by the APA.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.