Shevlin et al. (Reference Shevlin, Butter, McBride, Murphy, Gibson-Miller, Hartman and Bentall2021) noted that mean population estimates of mental health during coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19) pandemic may not adequately reflect the heterogeneity across individuals. Actually, heterogeneous patterns in COVID-19 outcomes indicate that the majority of the participants responded with consistently low intensity of anxiety/depressive symptoms during the pandemic (e.g. Kimhi, Eshel, Marciano, Adini, & Bonanno, Reference Kimhi, Eshel, Marciano, Adini and Bonanno2021; Saunders, Buckman, Fonagy, & Fancourt, Reference Saunders, Buckman, Fonagy and Fancourt2021; Shevlin et al., Reference Shevlin, Butter, McBride, Murphy, Gibson-Miller, Hartman and Bentall2021). Shevlin et al. (Reference Shevlin, Butter, McBride, Murphy, Gibson-Miller, Hartman and Bentall2021) claimed to be ‘Refuting the myth of a ‘tsunami’ of mental ill-health’ during COVID-19. However, before we can truly refute such a myth, more longitudinal research is needed in different countries affected by the pandemic. Our aim was to explore trajectories of change in anxiety-depressive symptoms during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic in Poland. We also examined risk/protective factors associated with the trajectories to identify vulnerable individuals and to implicate possible effective therapeutic and preventive interventions.

We collected data in five waves, between May 2020 and April 2021. T1 took place at the end of the first lockdown in Poland. By T2 and T3 almost all restrictions have been lifted. At T4 tighter restrictions were implemented, and by T5 a second lockdown was introduced. The study was approved by the institutional review board of the Faculty of Psychology, University of Warsaw. Participants were recruited online. The T1 sample (N = 1179) was representative of the Polish population with respect to gender, age, and place of residence. After removing 79 outliers, 1100 participants (51% females, 49% males) aged 18–85 (M = 44.70, s.d. = 15.82) were followed-up for approximately 1 year: T2 (N = 944), T3 (N = 792), T4 (N = 666) and T5 (N = 584). Detailed characteristics of the sample, data analytic strategy and results can be found at: https://osf.io/mpfwq/

We used the following questionnaires: Patient Health Questionnaire Anxiety-Depression Scale (PHQ-ADS; Kroenke et al., Reference Kroenke, Wu, Yu, Bair, Kean, Stump and Monahan2016); Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale Short Form (DERS-SF; Kaufman et al., Reference Kaufman, Xia, Fosco, Yaptangco, Skidmore and Crowell2016); Brief Empathic Sensitivity Questionnaire (Brief-ESQ; Gambin et al., Reference Gambin, Woźniak-Prus, Sekowski, Cudo, Pisula, Kiepura and Kmita2020), Scale of Perceived Health and Life Risk of COVID-19 and Social Support Scale (Gambin et al., Reference Gambin, Sękowski, Woźniak-Prus, Wnuk, Oleksy, Cudo and Maison2021).

We used unconditional univariate latent growth curve modeling to test whether outcome variables changed over time; MLR to account for non-normally distributed data; FIML to impute missing data; growth mixture modeling (GMM) to identify trajectories of anxiety-depressive symptoms; to identify the best fitting GMM for depressive-anxiety symptoms, we compared two- to five-class models using AIC, BIC, sample size adjusted BIC, entropy, BLRT and LRT tests; a three-step auxiliary model was used to explore T1 predictors of membership in each latent class v. the other classes.

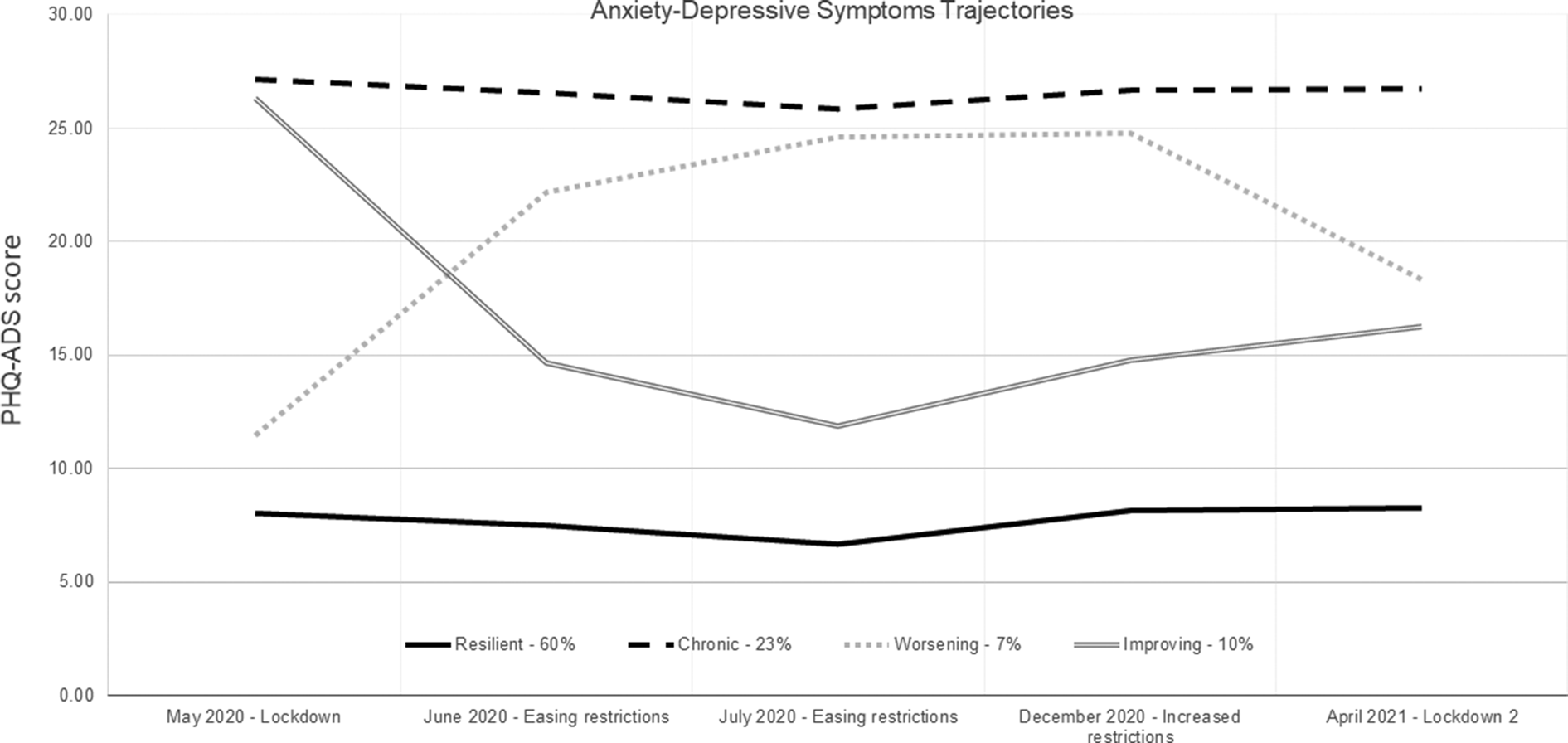

Based on the various fit statistics, as well as taking into account considerations of model coherence and interpretability, the four-class model (Fig. 1) was chosen as the optimal solution.

Fig. 1. Anxiety-depressive symptoms trajectories.

In accordance with prototypical trajectories following potential trauma (Bonanno, Reference Bonanno2004), as well as those observed in studies during COVID-19 (Kimhi et al., Reference Kimhi, Eshel, Marciano, Adini and Bonanno2021; Saunders et al., Reference Saunders, Buckman, Fonagy and Fancourt2021; Shevlin et al., Reference Shevlin, Butter, McBride, Murphy, Gibson-Miller, Hartman and Bentall2021), we identified Resilient, Improving, Chronic, and Worsening groups. The majority of participants (60%) were in the Resilient trajectory with stable, low anxiety-depressive symptoms throughout the period considered. A large percentage (23%) of adults was in the Chronic group. The Improving group (10%) experienced the highest levels of symptoms at the beginning of the pandemic, then decreased during loosening restrictions at summer and slightly increased during the second lockdown in April 2021. The Worsening group (7%) experienced an increase in symptoms during summer and autumn and then a slight decrease during the second lockdown.

Individuals in the Chronic group were younger than Resilient and Improving individuals, had a poorer financial situation than Resilient individuals, greater emotion regulation difficulties than Resilient and Worsening individuals, and greater distress, perceived risk of COVID-19 risk, and more chronic diseases compared to the Resilient group. Taken together, chronic elevations of anxiety-depressive symptoms appear to be coupled with the accumulation of greater pandemic-related stressors and the lack of socio-emotional resources to cope with them. Some of the needs and plans of young adults could be disturbed by the pandemic, as well as they could have less resources and experiences in dealing with crises and changes than older adults (Gambin et al., Reference Gambin, Sękowski, Woźniak-Prus, Wnuk, Oleksy, Cudo and Maison2021).

The Improving symptom trajectory was associated with higher baseline levels of emotion regulation difficulties and personal distress and more family members in the household as compared to Resilient group, as well as older age in comparison to Chronic group but a better financial situation compared to Worsening class. Older age and a better financial situation could be associated with having more resources and experiences in dealing with crises and changes in those individuals who were characterized by greater socio-emotional difficulties (higher emotion regulation difficulties and personal distress).

The Worsening trajectory was associated with a poorer financial situation compared to the Resilient and Improving trajectories and more family members in a household as compared to the Resilient group. It seems that the lower availability of economic resources and higher household density may have exacerbated the various challenges and hardships of the pandemic and contributed to growing levels of distress.

The primary limitations of our study were an exclusive use of online data and a lack of anxiety-depressive symptom data prior to the pandemic. It is difficult to determine the extent, for example, that individuals from the Chronic group may have experienced difficulties prior to the pandemic or elevated symptoms with the onset of the pandemic. Ideally, future research should strive to compare risk and protective factors of various long-term symptom patterns prior to, during, and after the pandemic in various countries and cultures.

Based on our results, we suggest that interventions building emotion regulation abilities and reducing excessive self-focus in interpersonal situations could be effective in reducing depression-anxiety symptoms during the pandemic. It would be crucial to target interventions for at-risk individuals: those in difficult financial and household situations and at a younger age.

Financial support

The research and the publication are financed by the funds from the Faculty of Psychology at the University of Warsaw awarded by the Polish Ministry of Science and Higher Education in the form of a subvention for maintaining and developing research potential in 2020.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical standards

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.